Venezuelan Migration, COVID-19 and Food (in)Security in Urban Areas of Ecuador

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The Context of the Venezuelan Migratory Crisis and Food Security in Latin America and Ecuador

1.2. The Multidimensional Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Ecuador

2. Methods

3. Results

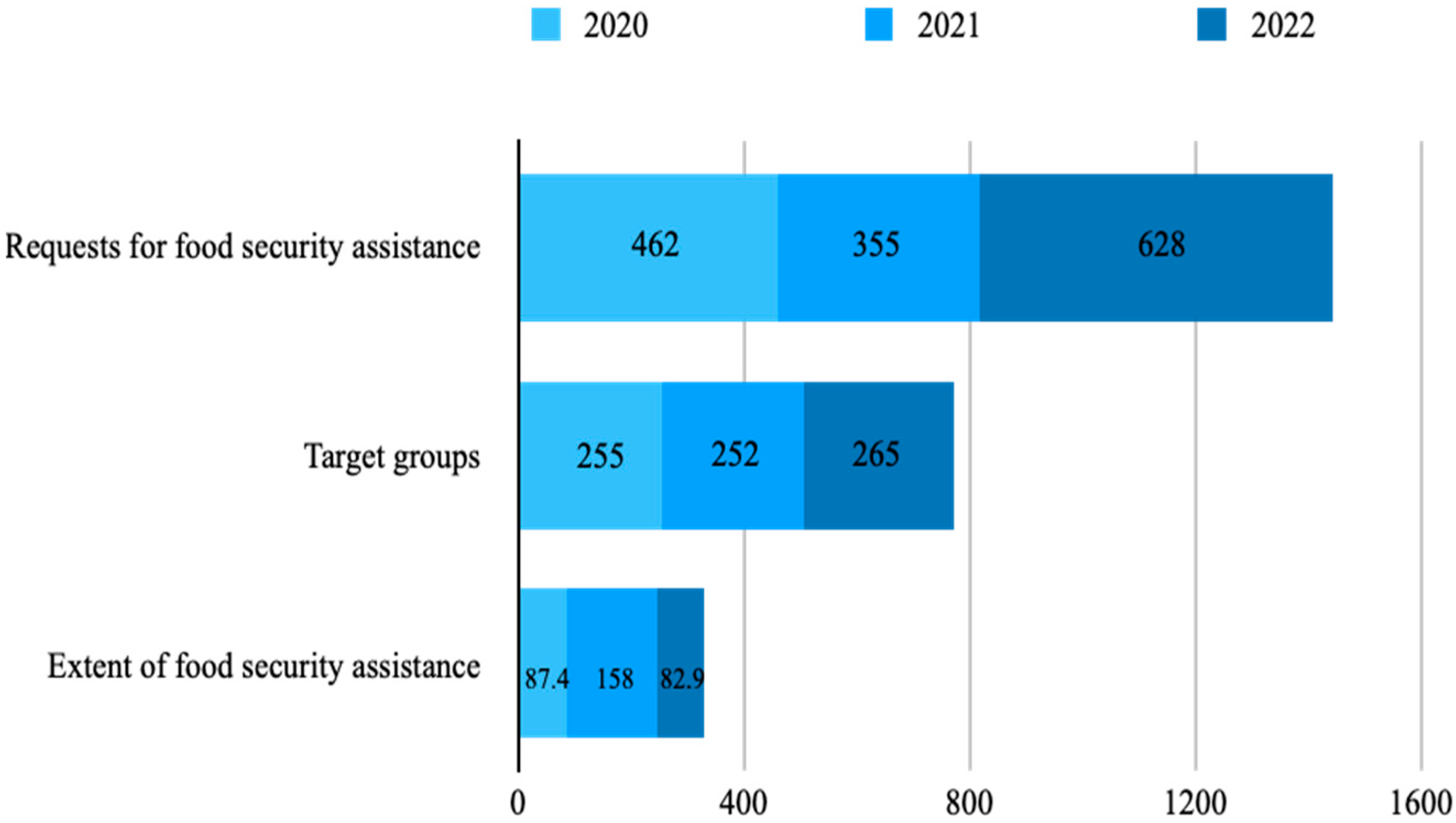

3.1. Systematic Review Results: Organizational and State Responses to Food Insecurity in Ecuador

3.2. Focus Group Results: Food Insecurity, Protection, and Well-Being

“I was working in the street selling my stuff, when they sent people to lock me up I was more afraid of starving to death than of COVID (...) we really had a very bad time with no money and no help, I did not know what to give my children, I suffered a lot because there were days with only a little bread and panela water”[42].

“The neighbor would give me a carton of eggs and I would make my desserts and my things for dinner and from there I would give him his portion; he was alone, but he had his chicken farm. So, we made do and sometimes I would cook for him, and he would give me the raw material he brought from the farm, and sometimes the neighbor at the store would give us some money and we got by”[42].

“Here the port never stopped. It is true that there were more restrictions to go out to the street and everything became a little more difficult, but there was no lack of food because everyone started to sell something”[43]

“We received a food basket from the IOM, but you know that this aid is given only once. I am a mother of two girls and the support ran out in a week. I went to the government, and they told me that they put me on a list, but I had to wait for them to distribute it to Ecuadorian families first, so I never received anything”[43].

“The closing of the border here affected the economy in Huaquillas a lot. Luckily, we did receive a lot of help from foundations 7 and I think that thanks to that there were many people who did not die of hunger”[43]

“They [NGOs] gave us tickets to go to the shelter’s dining room for lunch and sometimes there was not enough food for everyone but we shared”[42]

“The priority is my grandchildren, if they have dinner, I feel good, there were days when I was dying of hunger, I was almost on the verge of fainting but I would have an aromatic tea or a glass of red wine and I would go on. I always say that it doesn’t matter if I eat or not, because for me the most important thing is that the children can have something for breakfast and dinner”[44].

when you have children, you go to bed thinking about what you are going to give them for breakfast the next day (...) without working and having nothing, there were days when my husband and I did not eat to feed the kids[44].

The worst thing that can happen to you is to have hungry children because they do not understand what is happening (...) I was lucky that the lady who owned the house took pity on us and did not evict us because we could not even pay the rent”[42].

“Imagine, we had to decide between breakfast or lunch because the way things were, we didn’t have enough for everything. As such, we didn’t go too hungry, but we did have to adjust a lot”[42].

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Indigenous populations in Ecuador, according to Tuaza Castro (2020), were marginal-ized and impacted by COVID-19, yet demonstrated a great degree of resilience in their response to COVID-19, by tapping into local, regional, and national networks, and re-vitalizing the use of ancestral medicine. |

| 2 | Land borders remained closed from 16 March 2020, for a period 20 months in the case of the Ecuador-Colombian land border and 23 months in the case of Ecuador’s land border. |

| 3 | According to the last census data (2010), Quito had a population of 1.6 million people, Manta 217,553, Machala 231,260, and Puerto Lopez 206,682 Huaquillas, 47,700. |

| 4 | The disproportionate representation of women is related to the criteria set by interna-tional organizations, which prioritize programs for migrant women and other vulnera-ble groups within Ecuador and Latin America. |

| 5 | For example, see Patronato San José, of the Metropolitan Council of Quito, which from January to June 2022 provided 13,871 services to nationals and foreigners in street situ-ations. Available at: https://www.patronato.quito.gob.ec/patronato-en-datos/ (accessed on 21 October 2022). |

| 6 | The population of Huaquillas according to the last available census data in 2010: 47,706. |

| 7 | The term foundation was generally used by participants to refer to local non-governmental organizations. |

References

- Zambrano-Barragán, P.; Ramírez Hernández, S.; Feline Freier, L.; Luzes, M.; Sobczyk, R.; Rodríguez, A.; Beach, C. The impact of COVID-19 on Venezuelan migrants ’access to health: A qualitative study in Colombian and Peruvian cities. J. Migr. Health 2021, 3, 100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vivas, L.; Páez, T. La diáspora venezolana, ¿otra crisis inminente? Freedom House 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Landaeta–Jiménez, M.; Sifontes, Y.; Herrera Cuenca, M. Entre la inseguridad alimentaria y la malnutrición. An. Venez. De Nutr. 2018, 31, 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/ (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/refugiadosymigrantes (accessed on 3 February 2022).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/document/acnur-ecuador-monitoreo-de-proteccion-q2-2021-15-julio-2021 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- World Food Program. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/documents/details/85361 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Martens, C.; Milán, T.; Flores Torres, J.; Tria, J.; Gámez, I.; Marinelli, M.; Santos, D. The Current State of the Situation of Migrants and Refugees in Temporary Housing and Shelters in Ecuador March–April 2021; Care International: Quito, Ecuador, 2021; Available online: https://www.care.org.ec/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/CARE-The-current-state-Mig-Ref-shelters-in-ECU-2021-ENG.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2022).

- Celleri, D. Situación Laboral y Aporte Económico de Inmigrantes en el Centro/Sur de Quito-Ecuador; Fundación Rosa Luxemburg Oficina Región Andina: Quito, Ecuador, 2020; Available online: http://www.rosalux.org.ec/pdfs/SituacionLaboralYAporteEconomicoDeInmigrantes.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Rivero, P. El machismo siempre presente en el Informe de percepciones de xenofobia y discriminación hacia migrantes de Venezuela en Colombia, Ecuador y Perú. Oxfam Int. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diálogo Diverso. Diagnóstico de las Necesidades de las Personas LGBTI en Situación de Movilidad Humana, en las Ciudades de Quito, Guayaquil y Manta; Incluyendo la Variable Coyuntural de Impacto de la Crisis Sanitaria Ocasionada por el COVID-19. Available online: https://dialogodiverso.org/pdf/Diagnostico_COVID_19.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Bourdieu, P.; Wacquant, L.J. An Invitation to Reflexive Sociology; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Ecuador, el País que Venció la Pesadilla de la Pandemia en 100 Días. Available online: https://www.bancomundial.org/es/news/feature/2021/10/18/ecuador-the-country-that-vanquished-the-nightmare-pandemic-in-100-days (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- UNICEF. UNICEF Ecuador Emergency Response to COVID-19. March–June, 2020. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/ecuador/media/5581/file/Ecuador_UNICEF_INFORME_PAIS%202020_EN.pdf.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Tuaza Castro, L.A. El COVID-19 en las comunidades indígenas de Chimborazo, Ecuador, Latin American and Caribbean Ethnic Studies. Lat. Am. Caribb. Ethn. Stud. 2020, 15, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/dev/Impacto-macroeconomico-COVID-19-Ecuador.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2023).

- Gavilanes, M.J.; Llerena, G.A.; Lucero, E.M.; Céspedes, J.C. COVID-19 en Ecuador: Potenciales impactos en la seguridad alimentaria y la nutrición. INSPILIP 2021, 5, 1–9. Available online: https://www.inspilip.gob.ec/index.php/inspi/article/view/34/24&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1675109849933685&usg=AOvVaw1bsM7kvtOCIA7F6GtOf8-Q (accessed on 28 January 2023). [CrossRef]

- OCHA. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/ecuador/el-choque-covid-19-en-la-pobreza-desigualdad-y-clases-sociales-en-el-ecuador-una (accessed on 23 January 2023).

- Ministerio de Salud Pública and International Organization for Migration. Diagnóstico Situacional Sobre Violencia Basada en Género y Salud Sexual y Salud Reproductiva y su Vinculación con las Personas en Situación de Movilidad Humana. Quito: MSP-IOM. Available online: https://ecuador.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl776/files/documents/Diagnostico_situacional_COMPLETO.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Comité Permanente por la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos. No Tengo Dónde ir: Migrantes y Refugiados en Asentamientos Irregulares. Quito. Ecuador. October, 2021. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/sites/default/files/2021-08/Dossier.%20Asentamientos%20irregulares%20CDH%202021%20versi%C3%B3n%20digital%20%20%285%29.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2023).

- Brumat, L.; Finn, V. Mobility and citizenship during pandemics: The multilevel political responses in South America. Partecip. E Confl. 2022, 14, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, G. Migraciones en pandemia: Nuevas y viejas formas de desigualdad. Nueva Soc. 2021, 293, 106–116. [Google Scholar]

- Vera Espinoza, M.; Prieto Rosas, V.; Zapata, G.P.; Gandini, L.; Fernández de la Reguera, A.; Herrera, G.; López Villamil, S.; Zamora Gómez, C.M.; Blouin, C.; Montiel, C.; et al. Towards a typology of social protection for migrants and refugees in Latin America during the COVID-19 pandemic. Comp. Migr. Stud. 2021, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Álvarez Velasco, S.; Bayón Jiménez, M.; Hurtado Caicedo, F.; Pérez Martínez, L.; Baroja, C.; Tapia, J.; Yumbla, M.R. Viviendo al Límite: Migrantes Irregularizados en Ecuador; Colectivo de Geografía Crítica de Ecuador, Red Clamor y GIZ: Quito, Ecuador, 2021; ISBN 978-9942-38-993-0. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, H. Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis, 5th ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 2010; ISBN 9781506327792. [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Plan de Respuesta para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela (Enero-Diciembre 2020). Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/74747 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Refugee and Migrant Response Plan—Revisión (COVID-19). Available online: https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/76210 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. (Mid-Year Report) Response Plan for Refugees and Migrants. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/sites/default/files/2021-06/Mid%20Year%20Report%20RMRP%202020%20ENG%20FINAL.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Refugee and Migrant Response Plan 2021. Summary. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/document/ecuador-two-pager (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Refugee and Migrant Response Plan 2021. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/document/rmrp-2021-es (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Ecuador: Progress Report-May 2021. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/en/node/88045 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- WPF. Análisis de Vulnerabilidades Socioeconómicas de la Población Venezolana en Ecuador. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/sites/default/files/2021-07/AN%C3%81LISIS%20DE%20VULNERABILIDADES%20SOCIALES_POBLACI%C3%93N%20VENEZOLANA%20EN%20ECUADOR%20EFSA-S.pdf (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Reporte Mitad de Año—Julio 2021. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/sites/default/files/2021-07/%5BCLEAN%5D%20SitRep%20GTRM%20%28Junio%202021%29%20ESP.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Food Security Update. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/documents/details/85361 (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. RMRP 2020 Reporte de Fin de Año. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/document/rmrp-2020-reporte-de-fin-del-ano (accessed on 23 November 2022).

- Refugee and Migrant Response Plan Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Evaluación Conjunta de Necesidades—Mayo 2021. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/document/gtrm-ecuador-evaluacion-conjunta-necesidades-mayo-2021 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Reporte de Fin de Año—2021. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/document/gtrm-ecuador-reporte-de-fin-de-ano-2021 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- Grupo de Trabajo para Refugiados y Migrantes. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. Reporte de Situación—Julio 2022. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/document/gtrm-ecuador-reporte-de-situacion-julio-2022 (accessed on 8 August 2022).

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. R4V Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela. 2022. Available online: https://www.r4v.info/es/document/acnur-ecuador-monitoreo-de-proteccion-situacion-de-las-personas-refugiadas-y-otras-en (accessed on 10 December 2022).

- Venezuelan migrant, Focus Group, Quito, Ecuador.

- Venezuelan migrant, Focus Group, Portoviejo and Manta, Ecuador.

- Venezuelan migrant, Focus Group, Huaquillas and Machala, Ecuador.

| Resource Title | Year | Type of Document |

|---|---|---|

| Refugee and Migrant Response Plan [28] | 2020 | Response plan |

| Refugee and Migrant Response Plan, Revision (COVID-19) [29] | 2020 | Response plan |

| (Mid-Year Report) Response Plan for Refugees and Migrants [30] | 2020 | Report |

| Refugee and Migrant Response Plan [31] | 2021 | Summary |

| Refugee and Migrant Response Plan [32] | 2021 | Response plan |

| GTRM Ecuador: Progress Report, May 2021 [33] | 2021 | Report |

| WFP: Analysis of socioeconomic vulnerabilities of the Venezuelan population in Ecuador, March 2021 [34] | 2021 | Report |

| Refugee and Migrant Response Plan, 2021 (Mid-Year Report) [35] | 2021 | Report |

| Food Security Update [36] | 2021 | Factsheet |

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Requests for financial support * | 47.12 | 30.5 | 40.0 |

| Funding allocated * | 0.02 | 10.3 | 1.74 |

| Requests not financed * | 99.8% | 75% | 96% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Milán, T.; Martens, C. Venezuelan Migration, COVID-19 and Food (in)Security in Urban Areas of Ecuador. Land 2023, 12, 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12020517

Milán T, Martens C. Venezuelan Migration, COVID-19 and Food (in)Security in Urban Areas of Ecuador. Land. 2023; 12(2):517. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12020517

Chicago/Turabian StyleMilán, Taymi, and Cheryl Martens. 2023. "Venezuelan Migration, COVID-19 and Food (in)Security in Urban Areas of Ecuador" Land 12, no. 2: 517. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12020517