Research on Changsha Gardens in Ming Dynasty, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

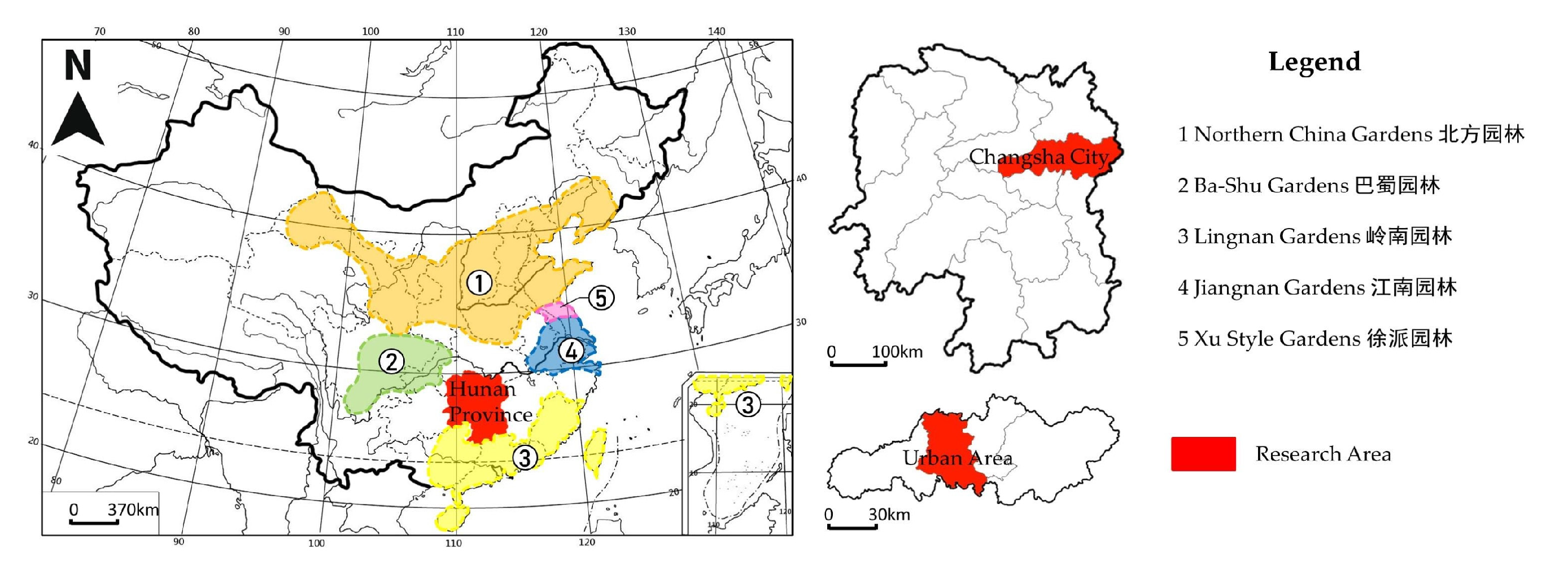

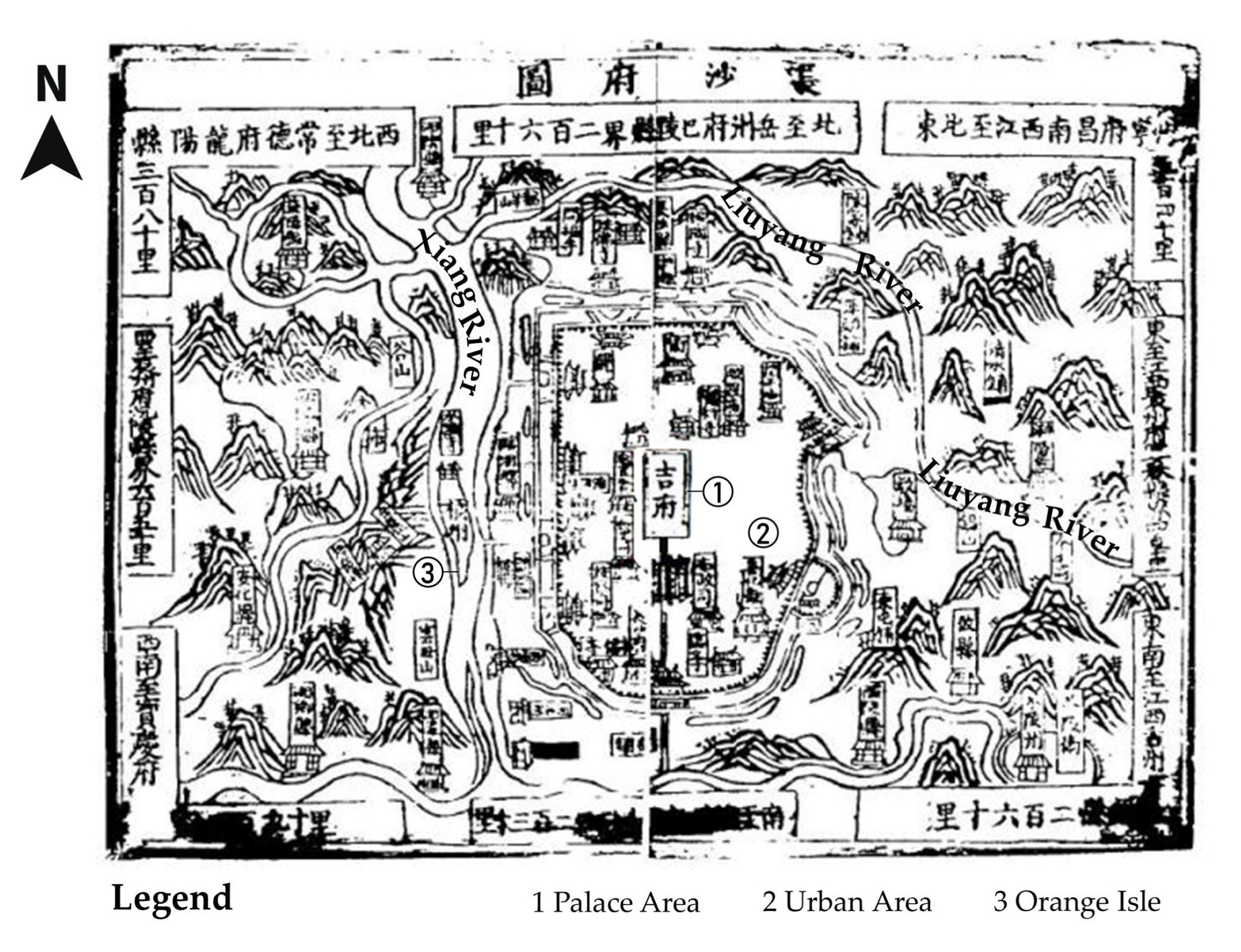

3.1. Overview of Changsha Gardens in the Ming Dynasty

3.1.1. The Social Background of the Rise of Changsha Gardens in the Ming Dynasty

3.1.2. The Overall Distribution and Number of Types of Gardens in Changsha in the Ming Dynasty

3.2. Description

3.2.1. Royal Gardens

- (1)

- Prince’s Palace Garden

- (2)

- Phoenix Terrace

- (3)

- Pine and Osmanthus Garden

3.2.2. Private Gardens

- (1)

- Banyan Tree Garden

- (2)

- North Manor

- (3)

- Cixian Lake

- (4)

- Wu Daoheng’s Garden

3.2.3. Academy Gardens

- (1)

- Time-Cherished Academy

- (2)

- Yanggu Academy

3.2.4. Religious Gardens

3.2.5. Gardens of Ancestral Hall

3.2.6. Gardens of Government Office

3.3. Analysis of Landscaping Techniques

3.3.1. The Method of Borrowing Scenery—Borrowing the Scenery of “Mountain, Water, isle and City” and the Hills Surrounding the City

- (1)

- Building Terraces

- (2)

- Mountaineering

3.3.2. Landscaping Techniques

- (1)

- Springs and Wells

- (2)

- Rectangular Ponds

- (3)

- Rockeries

4. Discussion

4.1. Eight Views Culture

4.2. Literati Tastes

4.3. Confucianism

- (1)

- Carry forward the Farming and Reading Culture

- (2)

- Commemorating Famous Sages and Educated People

- (3)

- Allegory of Confucianism

4.4. The Needs and Political Purposes of the Royal and the Literati

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilson, E. China: Mother of Gardens; The Stratford Company: Rockingham, VA, USA, 1929. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Zhao, W.; Shen, Z. Research on the Construction and Operation Mechanism of Overseas Chinese Gardens in the Past 40 Years. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2021, 37, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Wu, J. Sustainable Landscape Architecture: Enlightenment and Transcendence of Chinese Philosophy of ‘Heaven and Man’. Landsc. Ecol. 2009, 24, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Heritage List: Chinese Garden. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/?search=chinese+garden&order=country (accessed on 5 October 2022).

- Zhou, W. History of Chinese Classical Gardens; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 1999; pp. 351–764. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, C. Comparison of Ba-Shu Gardens and Jiangnan Gardens. Master’s Thesis, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, China, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T. Enriching the system of Chinese garden culture and art with in-depth research on local gardens. Garden 2021, 38, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bullington, J. East-West relational imaginaries: Classical Chinese gardens & self cultivation. Educ. Philos. Theory 2021, 53, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.; Yu, W.; Wang, H. Exploring the Distribution of Gardens in Suzhou City in the Qianlong Period through a Space Syntax Approach. Land 2021, 10, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Lian, Z. Research on the Distribution and Scale Evolution of Suzhou Gardens under the Urbanization Process from the Tang to the Qing Dynasty. Land 2021, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard, J. Uncovering the garden of the richest man on earth in nineteenth-century Canton: Howqua’s garden in Honam, China. Gard. Hist. 2015, 43, 168–181. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, W. Analysis of Gardening Characteristics and Style Formation of Lingnan Gardens. J. Landsc. Res. 2019, 11, 130–134. [Google Scholar]

- Siu, V. Gardens of a Chinese Emperor: Imperial Creations of the Qianlong Era, 1736–1796; Lehigh University Press: Bethlehem, PA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Lee, S.-H.; Choi, K.-R. Analysis of the Space and Design of Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Academy Gardens. Land 2022, 11, 1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L. Research on the History of Changsha Garden. Master’s Thesis, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, X. Research on the Inheritance and Innovation of Changsha Classical Gardens. Master’s Thesis, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F. Research on the Development of Hunan Gardens. Master’s Thesis, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y. Research on Changsha Garden. Master’s Thesis, Central South Forestry College, Changsha, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D. Research on the Development History and Environmental Characteristics of Traditional Religious Gardens in Changsha. Master’s Thesis, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W. Discussion about Why Changsha Became a Princedom Four Times during the Ming Dynasty. Hunan Prov. Mus. 2017, 1, 571–578. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. Records of Exploring Ancient Relics in Changsha; Yuelu Publishing House: Changsha, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X. Celebrities and Changsha Landscape; Hunan People’s Publishing House: Changsha, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, Q. Chronicles of Changsha Prefecture; Yuelu Publishing House: Changsha, China, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, K. Poetry of Southern Chu; Chinese Classics and Ancient Books Library; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Analects of Tianyue Mountain Mansion; Chinese Classics and Ancient Books Library; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. Chronicles and Atlas of Rebuilding Yuelu Academy; Chinese Classics and Ancient Books Library; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, N. Chronicles of Newly Revised Yuelu Academy; Chinese Classics and Ancient Books Library; Zhonghua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, J. Brief Chronicles of Yuelu; Hunan News Agency: Changsha, China, 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Li, Y.; Yi, B. From Tradition to Modern: The Change to the Urban Ancient Wells’ Folklore. J. Hunan Univ. Soc. Sci. 2007, 1, 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T. A preliminary research on the landscape form analysis of Changsha’s historical features. In Transformation and Reconstruction: In Proceedings of the 2011 China Urban Planning Annual Conference, Chongqing, China, 20 September 2011; pp. 7575–7584. [Google Scholar]

- Stones Commonly Used in Rockery Engineering (Stones Commonly Used in Rockery Engineering). Available online: http://chla.com.cn/html/c116/2010-03/52396.html (accessed on 3 November 2022).

- Zhang, J. On the Population Change of Huguang in Ming Dynasty. Econ. Rev. 1994, 2, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Feng, H. The Migration of Commercial Population and the Development of Local Culture in the Ming Dynasty. Acad. J. Zhongzhou 2019, 11, 132–137. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q. Landscape collective culture in China. Huazhong Archit. 1994, 2, 23–25. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, X.; Li, X.; Zhang, J. On the Cultural Consciousness of Chinese Garden in the View of Chinese “Eight Sceneries”. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2009, 25, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Woudstra, J.; Feng, W. ‘Eight Views’ versus ‘Eight Scenes’: The History of the Beijing Tradition in China. Landsc. Res. 2010, 35, 83–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D. “Farming and Reading Culture” in China. Agric. Hist. China 1996, 4, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S. The contemporary significance of Jia Yi’s former residence cultural heritage. Hunan Prov. Mus. Society. Collect. Work. Museol. 2014, 10, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- The Formation and Development of Huxiang School. Available online: https://www.xtol.cn/culture/2019/0722/5271732.shtml (accessed on 12 December 2022).

- Bao, Q. Study on Square Pools in Song Dynasty Gardens. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2012, 28, 73–76. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, G. The Ming Prince and Daoism: Institutional Patronage of an Elite; Shanghai Classics Publishing House: Shanghai, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y. The Manifestations and Causes of “Cultural and Educational Turn” in the Urban Landscape of Changsha Prefecture in Ming and Qing Dynasties. Master’s Thesis, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Zhu, X. The concept of Chinese Academy Education and Its Modern Enlightenment. Mod. Educ. Sci. 2009, 3, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Maderuelo, J. Paisaje e Historia; Abada Editores: Madrid, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Corredera, S.R. Methodological proposal for the study of cultural representations of landscape: The case of the western Costa del Sol (Málaga, Spain)”. Ería Rev. Cuatrimest. Geogr. 2022, 42, 213–241. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, W. Prequel to Changsha West Chang Street: Built in imitation of Beijing West Chang’an Street. Available online: https://moment.rednet.cn/pc/content/2019/11/02/6179783.html (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Tuan, Y.; Blake, B.F. Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes and Values; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1974; p. 323. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, J.; Ryan, J. Picturing Place: Photography and the Geographical Imagination; I. B. Tauris: London, UK, 2003; pp. 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, H. Geography’s creative (re) turn: Toward a critical framework. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2019, 43, 963–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Literati Works | Local Chronicles |

|---|---|

| Poetry of Southern Chu, 南楚诗纪, 1827 | Chronicles and Atlas of Rebuilding Yuelu Academy, 重修岳麓书院图志, 1594 |

| Analects of Tianyue Mountain Mansion, 天岳山馆文钞, 1880 Records of Exploring Ancient Relics in Changsha, 湘城访古录, 1893 Celebrities and Changsha Landscape, 名人与长沙风景, 2012 Memories of a City—Changsha in Old Maps, 一个城市的记忆—老地图中的长沙, 2018 | Chronicles of Changsha Prefecture, 长沙府志, 1639 Chronicles of Newly Revised Yuelu Academy, 新修岳麓书院志, 1687 Brief Chronicles of Yuelu, 岳麓小志, 1932 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, W.; Gao, C. Research on Changsha Gardens in Ming Dynasty, China. Land 2023, 12, 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12030707

Li W, Gao C. Research on Changsha Gardens in Ming Dynasty, China. Land. 2023; 12(3):707. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12030707

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Weiwen, and Chi Gao. 2023. "Research on Changsha Gardens in Ming Dynasty, China" Land 12, no. 3: 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12030707

APA StyleLi, W., & Gao, C. (2023). Research on Changsha Gardens in Ming Dynasty, China. Land, 12(3), 707. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12030707