Understanding Urban Green Spaces Typology’s Contribution to Comprehensive Green Infrastructure Planning: A Study of Canberra, the National Capital of Australia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What are the common green space typologies in the global literature?

- What are the significant types of UGS in Canberra?

- How can the UGS typology inform UGI planning and guide urban development in Canberra?

2. Methods

3. Results

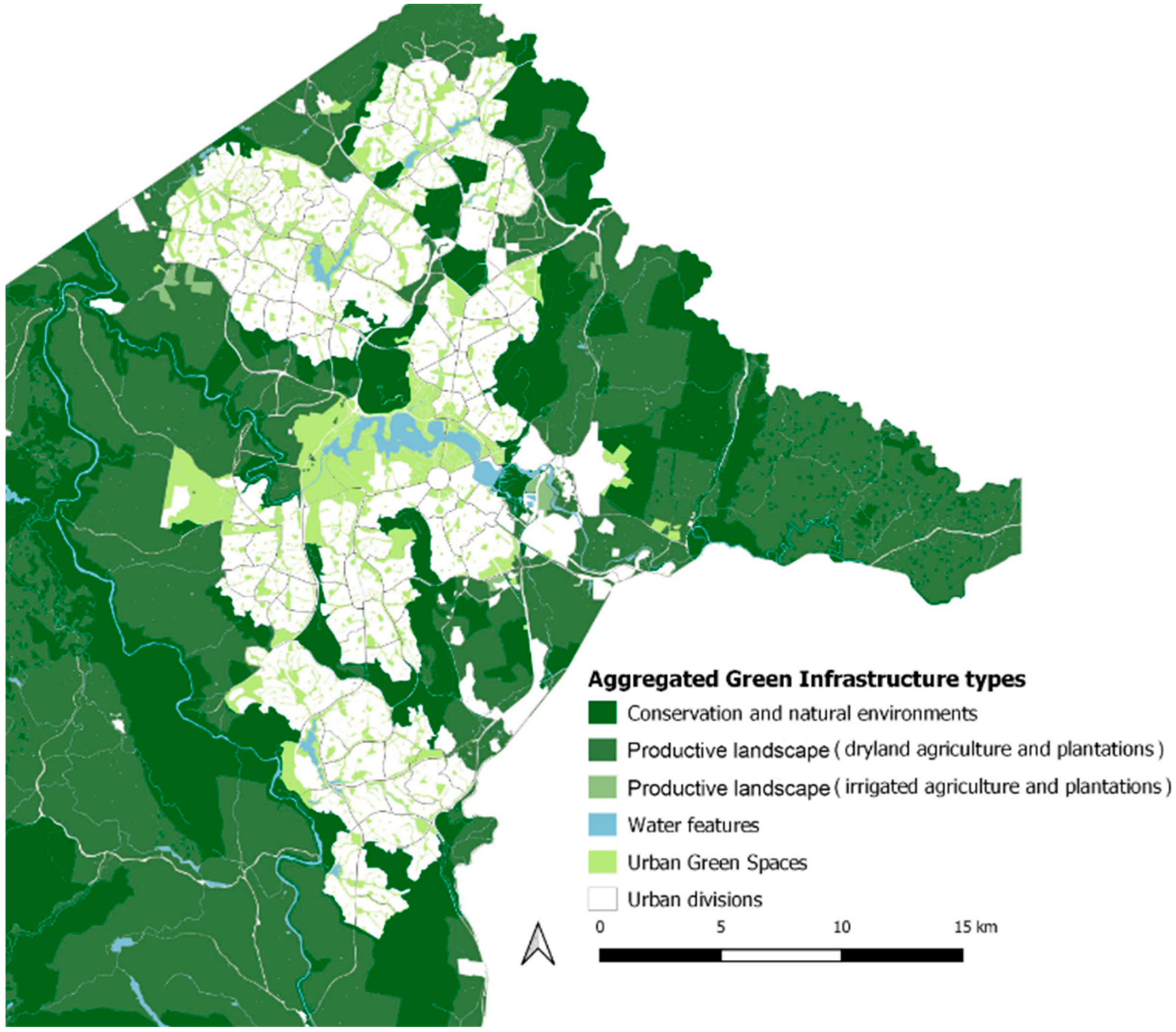

3.1. Diversity of Green Infrastructure Characters

3.2. Common Green Space Typologies

3.3. Green Space Typology in Canberra’s Policy Documents

| Typology | Criteria | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Tree canopy, biodiverse gardens, urban forest, local parks, watered grass and trees street trees, ovals, wetlands, creeks, nature reserves, parks, private yards, a system of trees, gardens, green walls and roofs balconies, reserves and open spaces, parkland trees, open space, and engineered wetlands. | A mix of land use and land cover | Canberra’s living infrastructure plan: Cooling the city [48] |

| Single trees, large habitat patches, and regional connectivity | Spatial scale | ACT Nature Conservation Strategy 2013–23 [49] |

| Linking, living, symbolic, and conservation areas. | Dominant character and function | National Capital Plan [46] |

| Human-made: recreation green spaces, town and district parks, neighbourhood and local parks, and National Capital Authority parks and forest reserves | Location, land use, plant community, and management responsibility | Explore: your free guide to Canberra’s urban parks, nature reserves, national parks, and recreational areas [47] |

| Natural green space: National Parks and nature reserves | ||

| Parks, playing grounds, landscape buffers, and community paths | UGS with unrestricted access | The Territory Plan 2008 Version R231 [50] |

| Parks, playing fields, pedestrian/cycle pathways, equestrian trails, and landscape buffers. Town parks, district parks, neighbourhood parks (central, local, and pocket), micro parks, community recreation parks (CRP), sports grounds, pedestrian parklands, laneways, informal use ovals, natural open space (grasslands or woodland sites), semi-natural open space, heritage parks, verges and medians (nature strips), special-purpose areas, and broadacre open space. | A mix of land cover (plant communities), function, size, and location | Urban Open Space, Municipal infrastructure standards 16 [51] |

3.4. The Green Space Typology from the Experts’ Perspective

“People, particularly value access to the natural green infrastructure. So that’s the nature reserves that are immediately adjacent to the suburbs.”(P7)

“Natural green spaces are actually part of our backyard and so they are intimately woven into our everyday life.”(P10)

“…especially being called the bush capital people have a strong connection to natural infrastructure.”(P8)

“Bush gives the identity to the city and people want it to be preserved in future.”(P3)

“Natural areas of vegetation are on some of the hills around the city like Black Mountain and Mount Ainslie, so from that point of view it was comfortable and attractive, that was familiar, without having any particular botanical interest.”(P5)

“NCOSS is a very high-value landscape because it has high environmental value, biodiversity value, it’s really important for water catchment… So that’s a very successful landscape. Canberra is unusual because it has this very high-quality green space, this open space, very close to the city.”(P1)

“I think you need to draw a distinction there between the national capital open space system and Parliamentary Triangle. So, there are two very distinct things.”(P12)

“Symbolic spaces have always been well protected and well managed, when tourists come, these are the places that they go, they can’t avoid going to the Anzac parade. A lot of attention is being paid towards protecting and maintaining the trees, and when some of the trees were dying, along Anzac parade they have specific plans to replace those trees.”(P8)

“Although people used their local park, local sporting oval is another sort of green infrastructure. Every suburb has a sporting oval. That’s fine for walking the dog, or that sort of thing, but wasn’t valued as highly as access to the more natural green spaces.”(P7)

“Ovals and sports fields have probably been some of the most contentious spaces in the debate about green space provision.”(P9)

“Sometimes we do have recreation spaces with lots of remnant vegetation in some areas but because it is a recreation space no value is given to that remnant vegetation.”(P2)

“…the parks that were say, for instance, going up through Sullivan’s Creek, and around down away they’ve created like the micro parks and the community really acting in managing and maintaining those parks.”(P11)

“…the network of corridors through the city. Besides the roadways arterials and highways. They form a green space network…”

“…increasingly people who ride bicycles or cycle network or another set of linear corridors, often following the creek lines.”(P12)

“The street trees are the most widespread form of urban green infrastructure.”

“…One of the things that I like about the gardens and street plantings and so on in Canberra is that people are able to grow a lot of those [exotic plants] for flowering, cherries for example, which are lovely trees very attractive, but you rarely see them in other states because summers are too hot for them.”(P5)

“major parkways to plant exotic conifers and some exotic broadleaf trees. The streets which were originally intended to be big enough to have a fully grown oak tree.”(P6)

“… one of the really nice things is the beautiful oak trees in the older suburbs and the verges are designed to be able to accommodate like those really big trees as well.”(P11)

“…another sort of green infrastructure is that every suburb has a sporting oval. That’s fine for walking the dog, or that sort of activities, but wasn’t valued as highly as access to the more natural spaces.”(P7)

“I think there’s a lot of potentials there considering the cemetery’s ability to provide habitat for biodiversity, I think is potentially huge, because they’re massive land holdings.”(P9)

“…those light industrial areas Fyshwick and Mitchell showed up the high temperature, because of the way they’ve been designed, they don’t have a lot of canopy cover.”(P7)

3.5. Towards a Green Space Typology for Canberra’s GI Planning

4. Discussion

4.1. Enabling the Potential of Functional Green Spaces and Private Land Use in UGI

4.2. The Potential of Neglected Space in GI Planning for a More Densified City

4.3. Preservation of Natural Green Spaces and Cultural Heritage

4.4. Reinforcing Productive Landscapes

4.5. Reinforcing the Role of Local UGS and Pocket Parks

4.6. Linear Green Spaces Need to Be Preserved and Strengthened

4.7. Investing in Trees for Ecological and Socioecological Values

4.8. Canberra’s UGI Future Direction

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Benedict, M.A.; McMahon, E.T. Green Infrastructure: Smart Conservation for the 21 Century. Renew. Resour. J. 2002, 20, 12–17. [Google Scholar]

- Lennon, M.; Scott, M.; Collier, M.; Foley, K. The emergence of green infrastructure as promoting the centralisation of a landscape perspective in spatial planning—The case of Ireland. Landsc. Res. 2017, 42, 146–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, R.; Zanders, J.; Lieberknecht, K.; Fassman-Beck, E. A comprehensive typology for mainstreaming urban green infrastructure. J. Hydrol. 2014, 519, 2571–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, R.S.; Alkemade, R.; Braat, L.; Hein, L.; Willemen, L. Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol. Complex. 2010, 7, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Millenium Ecosystem Assessment Synthesis Report; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sarabi, S.E.; Han, Q.; Romme, A.G.L.; de Vries, B.; Wendling, L. Key enablers of and barriers to the uptake and implementation of nature-based solutions in urban settings: A review. Resources 2019, 8, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; Ossola, A.; Bush, J. Nature-based solutions for changing urban landscapes: Lessons from Australia. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 73, 127611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellmann, T.; Andersson, E.; Knapp, S.; Lausch, A.; Palliwoda, J.; Priess, J.; Scheuer, S.; Haase, D. Reinforcing nature-based solutions through tools providing social-ecological-technological integration. Ambio 2022, 52, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, C.; MacFarlane, R.; McGloin, C.; Roe, M. Green Infrastructure Planning Guide. Project: Final Report. 2006. Available online: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1191.3688 (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- Ignatieva, M. Evolution of the Approaches to Planting Design of Parks and Gardens as Main Greenspaces of Green Infrastructure. In Urban Services to Ecosystems. Future City; Catalano, C., Andreucci, M.B., Guarino, R., Bretzel, F., Leone, M., Pasta, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 17, pp. 435–452. [Google Scholar]

- Braquinho, R.C.; Cvejić, R.; Eler, K.; Gonzales, P.; Haase, D.; Hansen, R.; Kabisch, N.; Rall, E.L.; Niemela, J.; Pauleit, S.; et al. A Typology of Urban Green Spaces, Eco-System Services Provisioning Services and Demands. 2015. Available online: https://assets.centralparknyc.org/pdfs/institute/p2p-upelp/1.004_Greensurge_A+Typology+of+Urban+Green+Spaces.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2021).

- Ives, C.D.; Oke, C.; Hehir, A.; Gordon, A.; Wang, Y.; Bekessy, S.A. Capturing residents’ values for urban green space: Mapping, analysis and guidance for practice. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 161, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, C.B.; Osmond, P.; Peters, A.; Irger, M. Mapping Local Climate Zones for urban morphology classification based on airborne remote sensing data. In Proceedings of the 2017 Joint Urban Remote Sensing Event (JURSE), Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 6–8 March 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Salmón, C.; Leyva-Camacho, O.; Rojas-Caldelas, R.; Alonso-Navarrete, A.; Iñiguez-Ayón, P. The identification and classification of green areas for urban planning using multispectral images at Baja California, Mexico. In The Sustainable City IX: Urban Regeneration and Sustainability; Marchettini, S.B.N., Brebbia, C.A., Pulselli, R., Eds.; WIT Press: Siena, Italy, 2014; Volume 191, pp. 611–621. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, X.; Du, J.; Han, Y.; Newman, G.; Retchless, D.; Zou, L.; Ham, Y.; Cai, Z. Developing Human-Centered Urban Digital Twins for Community Infrastructure Resilience: A Research Agenda. J. Plan. Lit. 2022, 38, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusie, J. Landscape Typology as the Basis for Landscape Protection and Development. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 1999, 64, 269–274. [Google Scholar]

- Simensen, T.; Halvorsen, R.; Erikstad, L. Methods for landscape characterisation and mapping: A systematic review. Land Use Policy 2018, 75, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanares, J.A.; Álvarez, J.M.M. Landscape classification of Huelva (Spain): An objective method of identification and characterization. Estud. Geogr. 2015, 76, 447–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koc, C.B.; Osmond, P.; Peters, A. Towards a comprehensive green infrastructure typology: A systematic review of approaches, methods and typologies. Urban Ecosyst. 2017, 20, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerome, G.; Sinnett, D.; Burgess, S.; Calvert, T.; Mortlock, R. A framework for assessing the quality of green infrastructure in the built environment in the UK. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 40, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandra, J. The city as nature and the nature of the city—Climate adaptation using living infrastructure: Governance and integration challenges. Aust. J. Water Resour. 2017, 21, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. Report on the Investigation into the Government’s Tree Management Practices and the Renewal of Canberra’s Urban Forest; Office of the Commissioner for Sustainability and the Environment: Canberra, Australia, 2011.

- Haaland, C.; van den Bosch, C.K. Challenges and strategies for urban green-space planning in cities undergoing densification: A review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2015, 14, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, M.; Barlow, D.; Cavan, G.; Cook, P.; Gilchrist, A.; Handley, J.; James, P.; Thompson, J.; Tzoulas, K.; Wheater, P.; et al. Mapping Urban Green Infrastructure: A Novel Landscape-Based Approach to Incorporating Land Use and Land Cover in the Mapping of Human-Dominated Systems. Land 2018, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful Sampling for Qualitative Data Collection and Analysis in Mixed Method Implementation Research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowarik, I. Urban wilderness: Supply, demand, and access. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 29, 336–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, P.G.; Ignatieva, M.; Granvik, M.; Hedfors, P. Green-blue infrastructure in urban-rural landscapes-Introducing resilient city-lands. Nord. J. Archit. Res. 2013, 11–37. Available online: http://arkitekturforskning.net/na/article/view/475 (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Tzoulas, K.; Korpela, K.; Venn, S.; Yli-Pelkonen, V.J.; Kazmierczak, A.; Niemela, J.; James, P. Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using Green Infrastructure: A literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2007, 81, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hough, M. Cities and Natural Process: A Basis for Sustainability; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rupprecht, C.D.; Byrne, J.A. Informal urban greenspace: A typology and trilingual systematic review of its role for urban residents and trends in the literature. Urban For. Urban Green. 2014, 13, 597–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, P. A systematic approach to incorporating multiple ecosystem services in landscape planning and design. Landsc. J. 2014, 33, 141–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombes, E.; Jones, A.P.; Hillsdon, M. The relationship of physical activity and overweight to objectively measured green space accessibility and use. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 816–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignatieva, M.; Haase, D.; Dushkova, D.; Haase, A. Lawns in Cities: From a Globalised Urban Green Space Phenomenon to Sustainable Nature-Based Solutions. Land 2020, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, C.D.D.; Byrne, J.A. Informal urban green-space: Comparison of quantity and characteristics in Brisbane, Australia and Sapporo, Japan. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzyk-Kaszy’nskaa, A.; Czepkiewicz, M.; Kronenberg, J. Eliciting non-monetary values of formal and informal urban green spaces using public participation GIS. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 160, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatieva, M.; Dushkova, D.; Martin, D.J.; Mofrad, F.; Stewart, K.; Hughes, M. From One to Many Natures: Integrating Divergent Urban Nature Visions to Support Nature-Based Solutions in Australia and Europe. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, S.; Hough, M. Rethinking city landscapes. Leis. Loisir. 2000, 25, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.; Montarzino, A. Green and Public Space Research: Mapping and Priorities; Department for Communities and Local Government: London, UK, 2006. Available online: https://www.openspace.eca.ed.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Green-and-Public-Space-Research-Mapping-and-Priorities-full-report.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Biernacka, M.; Kronenberg, J. Classification of institutional barriers affecting the availability, accessibility and attractiveness of urban green spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2018, 36, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, J.; Sipe, N. Green and Open Space Planning for Urban Consolidation—A Review of the Literature and Best Practice, Brisbane. 2010. Available online: https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au/bitstream/handle/10072/34502/62968_1.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2021).

- Hunter, A.J.; Luck, G.W. Defining and measuring the social-ecological quality of urban greenspace: A semi-systematic review. Urban Ecosyst. 2015, 18, 1139–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorska, D.; Edyta, Ł.; Krauze, K.; Sikorski, P. The role of informal green spaces in reducing inequalities in urban green space availability to children and seniors. Environ. Sci. Policy 2020, 108, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanwick, C.; Dunnett, N.; Woolley, H. Nature, Role and Value of Green Space in Towns and Cities: An Overview. Built Environ. 2003, 29, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.; Anderson, S.; Læssøe, J.; Banzhaf, E.; Jensen, A.; Bird, D.N.; Miller, J.; Hutchins, M.G.; Yang, J.; Garrett, J. A typology for urban Green Infrastructure to guide multifunctional planning of nature-based solutions. Nat.-Based Solut. 2022, 2, 100041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddon, G. An Open Space System for Canberra: A Policy Review Prepared for the National Capital Development Commission; Technical Paper 23; National Capital Development Commission: Canberra, Australia, 1977.

- National Capital Authority. National Capital Plan, Canberra. 2016. Available online: https://www.nca.gov.au/planning/plans-policies-and-guidelines/national-capital-plan (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- ACT Government. Explore: Your Free Guide to Canberra’s Urban Parks, Nature Reserves, National Parks and Recreational Areas, Canberra. 2013. Available online: https://www.environment.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/906472/Explore-Canberra-Parks-and-Recreation-Guide.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2020).

- ACT Government. Canberra’s Living Infrastructure Plan: Cooling the City; Environment Planning and Sustainable Development Directorate: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- ACT Government. ACT Nature Conservation Strategy 2013–23; ACT Government Environment and Sustainable Development Directorate: Canberra, Australia, 2013.

- ACT Parliamentary Counsel. The Territory Plan 2008 Version R231, Canberra, Australia. 2019. Available online: https://www.legislation.act.gov.au/ni/2008-27/Current (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- ACT Government. Urban Open Space, Municipal Infrastructure Standards 16; Transport Canberra and City Services Directorate: Canberra, Australia, 2019.

- Klingemann, H. Cemeteries in transformation—A Swiss community conflict study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 76, 127729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordh, H.; Stahl, A.; Kajosaari, A.; Liu, Y.; Rossi, S.; Gentin, S. Similar spaces, different usage: A comparative study on how residents in the capitals of Finland and Denmark use cemeteries as recreational landscapes. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 73, 127598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinton, J.M.; Duinker, P.N. Beyond burial: Researching and managing cemeteries as urban green spaces, with examples from Canada. Environ. Rev. 2019, 27, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallay, Á.; Mikh, Z.; Gecs, I.; Tak, K. Cemeteries as a Part of Green Infrastructure and Tourism. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tryjanowski, P.; Morelli, F.; Mikula, P.; Kri, A.; Indykiewicz, P. Bird diversity in urban green space: A large-scale analysis of di ff erences between parks and cemeteries in Central Europe. Urban For. Urban Green. 2017, 27, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, J.; Devereux, D.; Van Niel, T.; Barnett, G. Mapping Surface Urban Heat in Canberra, CSIRO, Australia. 2017. Available online: https://www.environment.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/1170968/CSIRO-Mapping-Surface-Urban-Heat-In-Canberra.pdf (accessed on 17 September 2020).

- Aitken, R.; Looker, M.; Australian Garden History Society. The Oxford Companion to Australian Gardens; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ignatieva, M. Spontaneous Urban Nature: Opportunities for Planting Design in Europe and Australia, 29; Uro Publications: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Instone, L. Unruly grasses: Affective attunements in the ecological restoration of urban native grasslands in Australia. Emot. Sp. Soc. 2014, 10, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACT Government. ACT Native Grassland Conservation Strategy and Action Plans, Environment, Planning and Sustainable Development, Canberra. 2017. Available online: https://www.environment.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/1156951/Grassland-Strategy-Final-WebAccess.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Nassauer, J.I.; Raskin, J. Urban vacancy and land use legacies: A frontier for urban ecological research, design, and planning. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiner, V. Build and They Will Come. Green Sustain. Archit. Landsc. Des. 2012, 25, 74–79. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/INFORMIT.543321364932730 (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Committe for Sydney. Nature Positive Sydney: Valuing Sydney’s Living Infrastructure. 2023. Available online: https://sydney.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Committee-for-Sydney-Nature-Positive-Sydney-February-2023.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Mofrad, F.; Ignatieva, M. What Is the Future of the Bush Capital? A Socio-Ecological Approach to Enhancing Canberra’s Green Infrastructure. Land 2023, 12, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GANSW. Better Placed—Connecting with Countary Draft Framework; GANSW: Parramatta, Australia, 2020.

- Knowles, B. The history of a Canberra house. Block 1 Section 1 (15 Mugga Way) Red Hill. Canberra Hist. J. 1996, 37, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Tsegaye, S.; Singleton, T.L.; Koeser, A.K.; Lamb, D.S.; Landry, S.M.; Lu, S.; Barber, J.B.; Hilbert, D.R.; Hamilton, K.O.; Northrop, R.J.; et al. Transitioning from gray to green (G2G)—A green infrastructure planning tool for the urban forest. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 40, 204–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikin, K.; Beaty, R.M.; Lindenmayer, D.B.; Knight, E.; Fischer, J.; Manning, A.D. Pocket parks in a compact city: How do birds respond to increasing residential density? Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kleyn, L.; Mumaw, L.; Corney, H. From green spaces to vital places: Connection and expression in urban greening. Aust. Geogr. 2020, 51, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Lindquist, M. Enhancing landscape connectivity through multifunctional green infrastructure corridor modeling and design. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 38, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauli, N.; Mouat, C.M.; Prendergast, K.; Chalmer, L.; Ramalho, C.E.; Ligtermoet, E. The Social and Ecological Values of Native Gardens Along Streets: A Socio-Ecological Study in the Suburbs of Perth; Report; Clean Air and Urban Landscapes Hub (CAUL): Melbourne, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingsley, J.; Egerer, M.; Nuttman, S.; Keniger, L.; Pettitt, P.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Gray, T.; Ossola, A.; Lin, B. Aisling Bailey Urban agriculture as a nature-based solution to address socio-ecological challenges in Australian cities. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 60, 127059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ligtermoet, E.; Ramalho, C.E.; Foellmer, J.; Pauli, N. Greening urban road verges highlights diverse views of multiple stakeholders on ecosystem service provision, challenges and preferred form. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICOMOS. Resolutions of the General Assembly Resolution 19GA 2017/15—Conservation of the Lake Burley Griffin and Lakeshore Landscape, Australia. In Proceedings of the 19th General Assembly of ICOMOS, New Dehli, India, 12–15 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, C.P.; Fernandes, C.O.; Ahern, J. Adaptive planting design and management framework for urban climate change adaptation and mitigation. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 70, 127548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, R.; Olafsson, A.S.; van der Jagt, A.P.N.; Rall, E.; Pauleit, S. Planning multifunctional green infrastructure for compact cities: What is the state of practice? Ecol. Indic. 2019, 96, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participants (P) | Expertise |

|---|---|

| P1 | Landscape Architecture |

| P2 | Urban Ecology |

| P3 | Urban Design |

| P4 | Town and Regional Planning and Urban Governance |

| P5 | Urban ecology and Botany |

| P6 | Urban Planning |

| P7 | Urban Forestry |

| P8 | Urban Forestry and Environmental science |

| P9 | Urban Design |

| P10 | Urban Planning |

| P11 | Landscape Architecture and Urban design |

| P12 | Landscape Architecture |

| Total | 12 |

| 1 | What types of urban green spaces are significant in Canberra? Why? |

| 2 | What types of urban green spaces are unique in Canberra? Why? |

| 3 | Which category of green spaces in your opinion is more vulnerable to climate-related challenges and urban development pressure in Canberra? (Why? Which factors do they contain that make them more vulnerable?) |

| 4 | Which type of green spaces do you think would be more resilient? (Why? Which factors do they contain that make them ecologically and socially resilient?) |

| Source | Origin of Study | Green Space Types |

|---|---|---|

| [19] | Australia | Green open spaces, water bodies, tree canopies, green roofs, and vertical greenery systems. |

| [41] | Australia | City parks, city gardens, sports ovals, nature strips, green roofs, domestic gardens, institutional grounds, cemeteries, urban agriculture, and conservation reserves. |

| [40] | Australia | Urban parks, nature parks, pocket parks, district parks, community parks, neighbourhood parks, sporting fields, and urban forests. |

| [37] | Canada | Corner park, plaza, local park, community park, regional park, and national park. |

| [14] | USA | Public services, recreation, sport, functional green spaces, roads landscape, natural green spaces, agriculture, livestock, industrial landscape, commercial, touristic, housing, and private green spaces. |

| [11] | Europe | Green balcony, green wall, green roof, atrium, bioswale, tree alley, street tree, hedge, house garden, railroad bank, green playground, school ground, river bank, urban park, historical park, historical garden, pocket park, botanical garden, zoological garden, neighbourhood green space, institutional green space, cemetery, churchyard, sports grounds, camping area, allotment, community garden, arable land, grassland, tree meadow, meadow orchard, agroforestry, horticulture, remnant forest, managed woodlands, shrubland, abandoned land, ruderal landscape, derelict lands, vegetated rocky areas, sand dunes, sandpit, quarry, open cast mine; wetland, bog, fen, marsh, lake, pond, river, stream, dry riverbed, rambla, canal, estuary, delta, and seacoast. |

| [42] | Europe | Formal: parks, squares, cemeteries, urban forests, and allotment gardens. Informal: (1) Managed green space types: Road landscape, railway landscape, airport, social services areas, recreational green space, grasslands and agriculture, water, and residential green space. (2) Unmanaged: Protected green space, non-forested vacant lots, forested vacant lots, and industrial and post-industrial areas. |

| [39] | Europe | Street greenery, private garden, neighbourhood green space, educational garden, botanical garden and zoological garden, green spaces along railway tracks, green square, allotment garden, cemetery, park, urban forest (public and private), arable land, grassland, orchard, brownfield, and greenfield. |

| [43] | Europe | Recreation green space (parks and gardens, informal recreation areas, outdoor sports areas, and; play areas), incidental green space (housing green space), private green space (domestic gardens), productive green space (remnant farmland, city farms, and allotments), burial grounds (cemeteries and churchyards), institutional grounds (school grounds and other institutional grounds), wetlands (open/running water, marsh, and fen), woodlands (deciduous woodland, coniferous woodland, and mixed woodland), other habitats (moor/health, grassland, and disturbed ground), and linear green space (river and canal banks, transport corridors, and other linear features) |

| [38] | Europe | Parks and gardens (urban parks and gardens, private gardens, and country parks), natural and semi-natural spaces (water and wetlands, woodlands, remnant, vacant land, green belt, and post-industrial land), green corridors (tree belts and woodland, linear green spaces, canal and riverbanks, and disused railways), outdoor sports facilities (school playing fields, other playing fields and pitches, and other sports), amenity green spaces (including housing green space), children’s playground, allotments, community gardens and urban farms, urban agriculture, cemeteries, and public space (streets, residential roads, civic squares, seafronts and promenades, market places, shopping precincts, settings for the public, and heritage buildings landscape). |

| [44] | Europe | Gardens, parks, amenity areas, other public spaces, linear features, constructed GI on infrastructure, hybrid GI for water, waterbodies, and other non-sealed urban areas. |

| UGI | UGS | Associated Value and Benefits (ESS) * | Additional Information And Considerations | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | SH | C | |||

| Natural landscape | Nature reserve | Contains native grassland, woodland, and grassy woodland. | ||||

| National parks | A piece of land that is safeguarded against development for its significance regarding native natural attributes, such as its natural history, physical features, flora, and fauna. | |||||

| NCOSS | It contains significant areas of the native natural landscape (excluding Lake Burley Griffin (a human-made lake)). NCOSS has attained symbolic values and is critical in conserving the national capital’s significance. | |||||

| Productive landscape | Urban agriculture | Includes orchards, community gardens, and city farms. Promotes environmental involvement and provides fresh produce, managed by the users. | ||||

| Agricultural and horticultural lands | Dryland/irrigated agriculture and plantations. Linked to the idea of a garden city and important for serving provisioning ESS. | |||||

| Forest reserves | Include massive tree plantations for industrial usage. These sites can be used for recreation. | |||||

| Linear landscape | Water corridors | River corridors, creek corridors. | ||||

| Road landscape | Parkways, main roads’ boulevards and verges with trees and plants. It could have high cultural values in case being integrated with pedestrian and cycling pathway. | |||||

| Railway landscape | Depending on the management level, it can be covered by spontaneous vegetation or can be designed adopting WSUD approach to provide native green corridors that serve multiple ESS. | |||||

| Recreational landscape | Public parks and gardens | They dominate by exotic vegetation character in central Canberra (historical part) and native vegetation in the newly established suburbs. Some parks were assigned to heritage values. | ||||

| Civic plaza | Mainly includes trees to provide shade and vegetation (native and exotic) for aesthetic values. | |||||

| Playing fields | Includes sports ovals and golf courses. | |||||

| National Arboretum | Designed green space. Serves as a tourist destination. | |||||

| Ceremonial landscape | War Memorial landscape | Anzac parade. Symbolic space. Unique to Canberra. Serves as a tourist destination. | ||||

| National Triangle landscape | Symbolic landscape, associated with design heritage values. Serves as a tourist destination. | |||||

| Cultural landscape | National Gallery and museums landscapes | Tourist destination, high sociocultural value green spaces located around Lake Burley Griffin. | ||||

| Heritage trees/landscapes | High value from an ecological and sociocultural perspective. It includes two categories of European and Aboriginal history. | |||||

| Pastoral landscape | Linked to the heritage of the first European settlers and the landscape setting before the city’s establishment. | |||||

| Lake Burley Griffin | Includes the cultural landscape, and recreational green spaces. Provides a setting for ecological connectivity. Offers social and recreational services. | |||||

| Suburban landscape | Suburban parklands | Public parks offer recreational and conservation opportunities. With potential amenities and practical uses such as stormwater management. | ||||

| Streetscape | Verge gardening. Nature strip: (native verges gardens, mowed lawn verges), street trees, exotic street trees. | |||||

| Pocket parks | Can include community gardens. | |||||

| Neighbourhood parks | Important for the neighbourhood residents to have quick access to green space during a pandemic and for physical activities. Can include community gardens. | |||||

| Private yards | Their ESS varies as it is dependent on the green space coverage and plants planted by the owner. Can be used for food production such as planting herbs and citrus trees. | |||||

| Water landscape | Suburban lakes and ponds. | |||||

| Ecologically designed landscape | Bioswales, rain gardens | Designed for ecological services but also adds to the amenity and aesthetic values. Critical for water-sensitive urban design and sustainable water management. | ||||

| Biodiverse gardens | Designed green spaces using native vegetation. Associated with the aesthetic and symbolic values of native vegetation, and highly contributes to biodiversity. | |||||

| Wetlands | Designed for ecological services but also adds to the amenity and aesthetic values. | |||||

| Functional landscapes | Industrial sites | In the case of being planned and designed ecologically, they can offer regulating ESS, provide habitat, and enhance human environment. Area in and around Fyshwick and Mitchell. | ||||

| Cemetery | Significant land holding, mostly exotic vegetation (lawns, scattered trees). Included in land use planning but its potential for being included in UGI planning needs to be researched. | |||||

| Landscape setting of public and private buildings | Biodiversity, climate, aesthetic, and social values. Green roof, green wall, site landscaping. Can be used as a common area and for urban agriculture purposes (for example on apartments rooftops). Could be accessible by public (e.g., a mall rooftop). Plants—no need for irrigation (intensive), plant—needs to be maintained (extensive). | |||||

| Informal landscape | Brownfields | Abandoned industrial site, landfill covered with by weeds. Serve as habitats for fauna. Provide regulating ESS when they are green. | ||||

| Vacant lands | Non-managed private lands covered with non-native spontaneous weeds. Serve as habitats for fauna. Provide regulating ESS when they are green. | |||||

| UGI Type | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Natural landscape | Restoring and celebrating the unique native ecology. Ensuring ongoing engagement with the local community and Aboriginal people. Educating people to look after the natural green space. |

| Productive landscape | Valuing the productive green spaces located on the green belt and their connection with early settlers on the site. Encouraging the owner to better invest in the area through education, cultural practice, and incentives. |

| Linear landscape | Promoting the design legacy of vistas and linear green corridors. Developing the concept and idea in design interventions. Strengthening the linear green spaces by connecting various green spaces and integrating them with grey infrastructure for social and ecological benefits. Land acquisition for developing green corridors. Significant potential for adopting a WSUD approach. |

| Recreational landscape | Considering different active and passive recreation in the green space design. Designing multifunctional green spaces. Considering biodiversity values in the design and planning of green spaces such as oval. Working with the communities, adopting a bottom-up approach. |

| Ceremonial landscape | Conserving and promoting these green spaces for symbolic values and tourist attraction. Designing multifunctional green spaces to better link the community with the formal landscape. Considering biodiversity values in the design of formal spaces. |

| Cultural landscape | Conserving green spaces within and as a setting for green spaces with cultural values. Designing green spaces with an ecological approach to strengthening the connection with the native environment. Designing multifunctional green spaces. |

| Suburban landscape | Designing green spaces that encourage social interactions. Considering community gardens which are designed in attractive ways. Designing multifunctional green spaces, adopting a bottom-up approach. Ecologically designed approach for verges and suburban green spaces and private land uses in the suburb. Incentives for implementing green roofs and green walls for apartments. |

| Ecologically designed landscape | Incentives to promote ecologically designed landscapes in different land uses such as residential gardens and neighbourhood verges. Encouraging the landscape and urban design firms to adapt this approach. Educating people about the benefits and the methods to implement and maintain these green spaces. |

| Functional landscape | Their potential for greenery and offering multiple ESS should be studied further. Should be considered in GI planning. Encouraging adapting of the NBS approach to enhance microclimate and social health. |

| Informal landscape | Conducting more research on the vegetation types, services, and disservices. Replacing these landscapes with nature-positive green spaces if it is possible. Exploring the possible ways to use these types of landscapes in a controlled way in urban areas when there is not an opportunity to take a nature-positive ecological approach to design. Changing land use or temporary use of the space for human activity purposes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ignatieva, M.; Mofrad, F. Understanding Urban Green Spaces Typology’s Contribution to Comprehensive Green Infrastructure Planning: A Study of Canberra, the National Capital of Australia. Land 2023, 12, 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12050950

Ignatieva M, Mofrad F. Understanding Urban Green Spaces Typology’s Contribution to Comprehensive Green Infrastructure Planning: A Study of Canberra, the National Capital of Australia. Land. 2023; 12(5):950. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12050950

Chicago/Turabian StyleIgnatieva, Maria, and Fahimeh Mofrad. 2023. "Understanding Urban Green Spaces Typology’s Contribution to Comprehensive Green Infrastructure Planning: A Study of Canberra, the National Capital of Australia" Land 12, no. 5: 950. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12050950