Background Conditions for Revitalisation Processes in the Case of Unused Public Buildings in Italy: An Ostromian Perspective

Abstract

:1. Unused Publicly Owned Buildings and Civic Actors: A Fertile Combination for Social Innovation?

2. Institutional Performances and Methodology

3. Civic Actors and Revitalisation Processes: The Result of an Italian Investigation

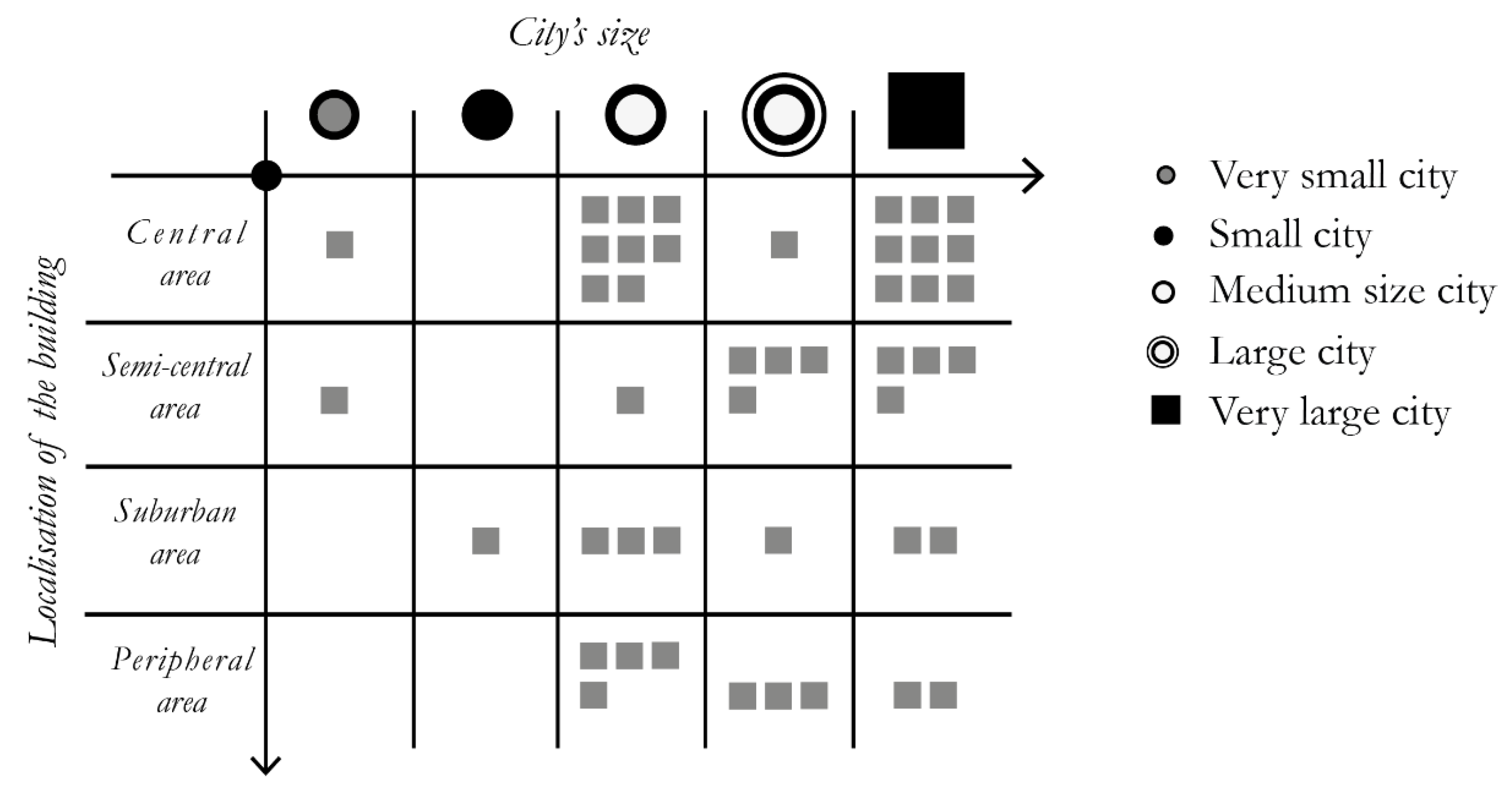

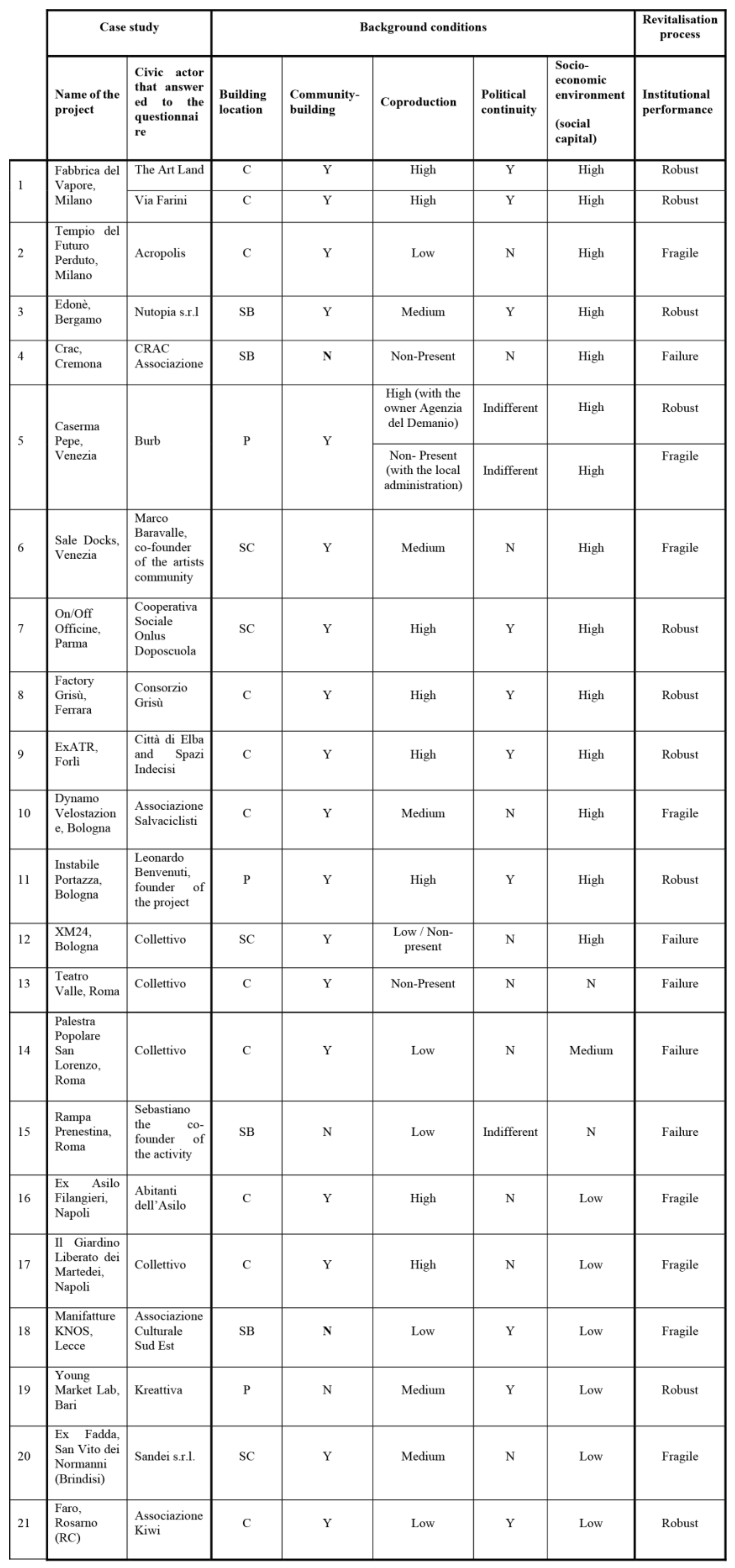

3.1. Location of the Building

3.2. Patterns of Behaviour, Civic Actors’ Institutions and Public Sphere’s Attitudes

3.3. Uncertainty

4. The Role of Background Conditions in Revitalisation Processes

4.1. Case-Based Conditions

4.2. Framework Conditions

5. Discussion and Policy Implications

6. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

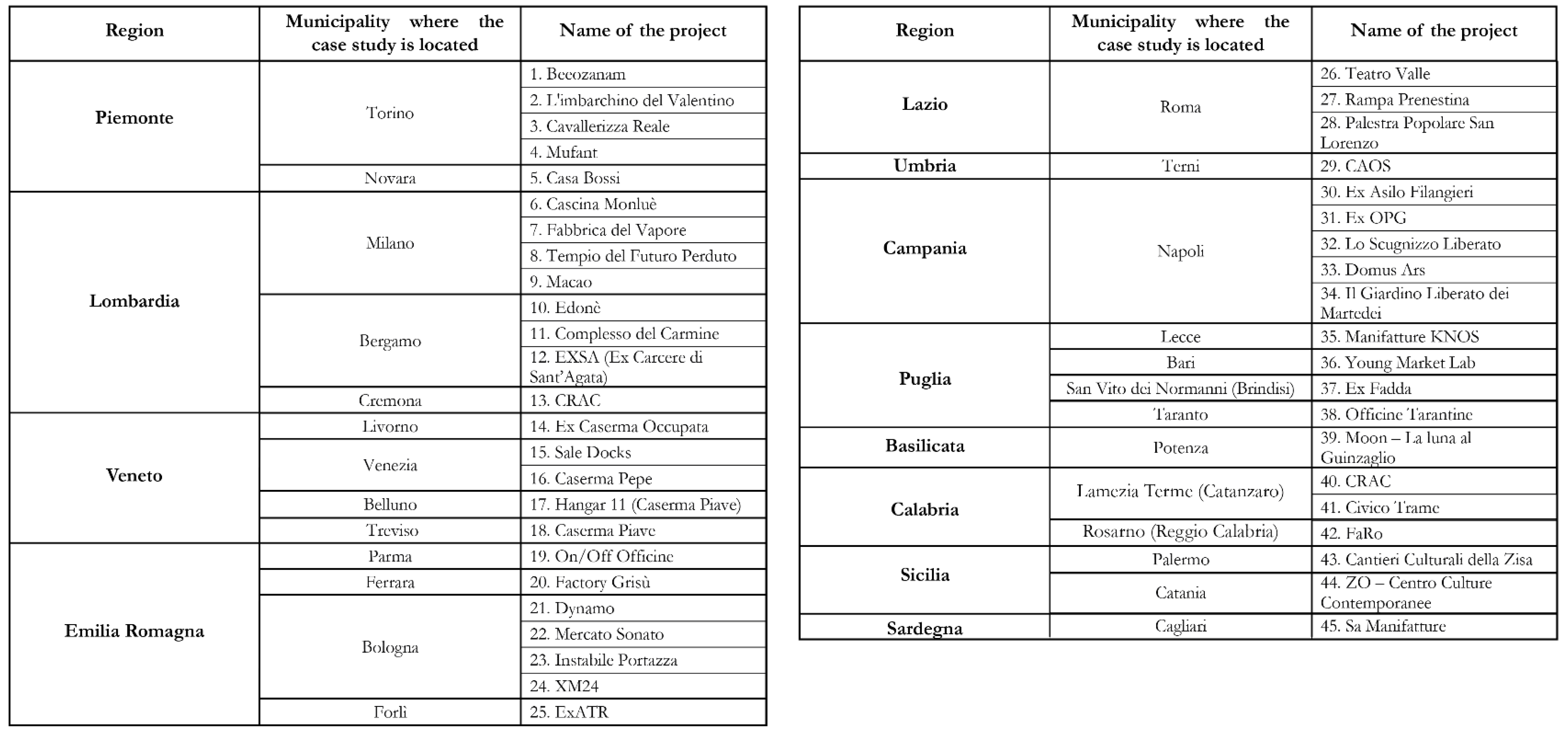

| 1 | The selected cases respond to a twofold analysis: the presence of a civic actor (in line with the features discussed by XXX [11]) and its activities in a former unused public building. The selected cases are based on different dynamics that are significant and valuable to report. The selected cases are located in different Italian regions (namely, Piemonte, Lombardia, Veneto, Emilia Romagna, Toscana, Lazio, Umbria, Campania, Puglia, Basilicata, Calabria, Sicilia and Sardegna). They provide an overview of examples, dynamics and kinds of activities. Although the list is not exhaustive, it encompasses a variety of cases that contributes to a general understanding of the phenomenon. |

| 2 | The questionnaire was distributed to half of the civic actors involved in revitalisation processes within the selected case studies in the sample. The questionnaire is organised in two sections. The first section consists of general questions pertaining process and the revitalisation programme they are engaged in (with both open-ended and close-ended questions). The second section includes ‘orientative questions’ that inquire about their expectations and vision for the revitalisation process. |

| 3 | They are extensively analysed in the PhD thesis, discussed in July 2021. |

| 4 | Last updated February 2023. The first research was conducted within 2019–2020, and the average was a bit different, with 64% of cases ongoing, 18% of cases ‘pending’ and 18% concluded. |

| 5 | The cases are investigated based on the deductive method, introducing key features of generalisation: public building (property, location, typology and condition of maintenance); civic actors (name of the group, nature of the group, nature of the action, nature of the trigger, social entrepreneur and composition of the group); kind of agreement (if present, cooperation with the public administration); economic sustainability (public intervention on the building, kind of funds); and duration of the case. In this way, the cases are grouped in the same scheme, and the categories can be comparable |

| 6 | In general, rationalisation of publicly owned buildings started in the early 1990s to facilitate the free-market sale of those assets. This process was pursued for two main reasons: On the one hand, there was a decrease in the need for military garrisons after the abolishment of the military services obligation; on the other hand, there was a need by the State to sell buildings on the market due to growing public debt. |

References

- Rauws, W.S. Embracing uncertainty without abandoning planning: Exploring an adaptive planning approach for guiding urban transformations. Disp Plan. Rev. 2017, 53, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, S.; Moroni, S. Multiple agents and self-organisation in complex cities: The crucial role of several properties. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cozzolino, S.; Moroni, S. Structural preconditions for adaptive urban areas: Framework rules, several property and the range of possible actions. Cities 2022, 130, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abastante, F.; Lami, I.M.; Mecca, B. Performance indicators framework to analyse factors influencing the success of six urban cultural regeneration cases. In New Metropolitan Perspective; Bevilacqua, C., Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 886–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingaramo, R.; Lami, I.M.; Robiglio, M. How to Activate the Value in Existing Stocks through Adaptive Reuse: An Incremental Architecture Strategy. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanzi, V.; Prakash, T. The Cost of Governments and the Misuse of Public Assets; Working Paper; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kaganova, O.; Amoils, J.M. Central government property asset management: A review of international changes. J. Corp. Real Estate 2020, 22, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaganova, O.; Telgarsky, J. Management of capital assets by local governments: An assessment and 850 benchmarking survey. Int. J. Strateg. Prop. Manag. 2018, 22, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermiglio, C. Public property management in Italian municipalities: Framework, current issues and viable solutions. Prop. Manag. 2011, 29, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.W. Economics, Real Estate and the Supply of Land; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bellè, B.M. Unused public buildings and civic actors. A new way to rethink urban regeneration processes. In New Metropolitan Perspectives. NMP 2020. Smart Innovation, Systems and Technologies; Bevilacqua, C., Calabrò, F., Della Spina, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 178, pp. 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, S.; De Franco, A.; Bellè, B.M. Vacant buildings. Distinguishing heterogeneous cases: Public items versus private items; empty properties versus abandoned properties. In Abandoned Buildings in Contemporary Cities: Smart Conditions for Actions; Lami, I., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, S.; De Franco, A.; Bellè, B.M. Unused private and public buildings: Re-discussing merely empty and truly abandoned situations, with particular reference to the case of Italy and the city of Milan. J. Urban Aff. 2020; online ahead of print. 1299–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANCE. Osservatorio Congiunturale Sull’industria Delle Costruzioni; ANCE: Roma, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tajani, F.; Morano, P. Evaluation of vacant and redundant public properties and risk control: A model for the definition of the optimal mix of eligible functions. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2017, 35, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangialardo, A.; Micelli, E. From sources of financial value to commons: Emerging policies for enhancing public real-estate assets in Italy. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2018, 97, 1397–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini Baraldi, S.; Salone, C. Building on decay: Urban regeneration and social entrepreneurship in Italy through culture and the arts. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2022, 30, 2102–2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, F.; Bertolini, L. Urban experimentation as a politics of niches. Econ. Space 2019, 51, 831–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesch, U.; Spekkink, W.; Quist, J. Local sustainability initiatives: Innovation and civic engagement in societal experiments. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 300–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacchi, C. Iniziative Dal Basso E Trasformazioni Urbane. L’attivismo Civico Di Fronte Alle Dinamiche Di Governo Locale; Mondadori: Milano, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Moulaert, F.; Hillier, J.; McCallum, D.; Vicari Haddock, S. Social Innovation and Territorial Development; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Barbera, F.; Parisi, T. Innovatori Social. La Sindrome Di Prometeo Nell’Italia Che Cambia; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Savini, F.; Dembski, S. Manufacturing the creative city: Symbols and politics of Amsterdam North. Cities 2016, 55, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, F. Responsibility, polity, value: The (un)changing norms of planning practices. Plan. Theory 2018, 18, 58–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauws, W.S.; de Jong, M. Dealing with tensions: The expertise of boundary spanners in facilitating community initiatives. In Planning and Knowledge. How New Forms of Technocracy Are Shaping Contemporary Cities; Raco, M., Savini, F., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2019; pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricarico, L.; Jones, M.Z.; Daldanise, G. Platform spaces: When culture and the arts intersect territorial development and social innovation, a view from the Italian context. J. Urban Aff. 2020, 44, 545–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnoli, G.; Tognetti, R. L’Italia Da Riusare. La Nuova Ecologia. 2016. Available online: https://www.osservatorioriuso.it (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Gastaldi, F.; Camerin, F. The decommissioning of military real estate. Sci. Reg. 2017, 16, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerin, F.; Gastaldi, F. Il ruolo dei fondi di investimento immobiliare nella riconversione del patrimonio immobiliare pubblico in Italia. Work. Papers. Riv. Online Di Urban@It 2018, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Arena, G. Cosa Sono E Come Funzionano I Patti per la Cura Dei Beni Comuni. Labsus. 2016. Available online: https://www.labsus.org/2016/02/cosa-sono-e-come-funzionano-i-patti-per-la-cura-dei-beni-comuni/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Labsus. Rapporto 2021. Sull’amministrazione Condivisa Dei Beni Comuni. 2022. Available online: https://www.labsus.org/ (accessed on 1 April 2023).

- Ostanel, E. Spazi Fuori Dal Comune. Rigenerare, Includere, Innovare; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoletti, R.; Faccioli, F. Public engagement, local policies, and citizens’ participation: An Italian case study of civic collaboration. Soc. Media + Soc. 2016, 2, 2056305116662187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricarico, L.; Pacchi, C. Community entrepreneurship and co-production in urban development. Territorio 2018, 87, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragaglia, F. Social innovation as a ‘magic concept’ for policy-makers and its implications for urban governance. Plan. Theory 2021, 20, 102–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricarico, L.; De Vidovich, L. Imprenditorialità, Inclusione o Co-produzione? Innovazione sociale e possibili approcci territoriali. Crios 2021, 21, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weck, S.; Madanipour, A.; Schmitt, P. Place-based development and spatial justice. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2021, 30, 791–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Salet, W. Evolving Institutions. An International Exploration into Planning and Law. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2002, 22, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A. New institutionalism and planning theory. In Handbook of Planning Theory; Madanipour, M.G., Watson, A.V., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 250–263. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, P. The New Institutionalism and the Transformative Goals of Planning. In Institutions and Planning; Varna, N., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Alston, E.; Alston, L.J.; Mueller, B.; Nonnenmacher, T. Institutional and Organizational Analysis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S.; Healey, P. A sociological institutionalist Approach to the study of innovation in governance capacity. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 2055–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schönfeld, K.C.; Tan, W.; Wiekens, C.; Salet, W.; Janssen-Jansen, L. Social learning as an analytical lens for co-creative planning. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1291–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, A. Institutions and urban space. Land, infrastructure, and governance in the production of urban property. Plan. Theory Pract. 2017, 19, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Beyond markets and states: Polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 2010, 100, 641–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerrin, J. Case Study Research. Principles and Practices; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rihoux, B.; Lobe, B. The case for Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): Adding Leverage for thick cross-case comparison. In The SAGE Handbook of Case-Based Methods; Byrne, D.S., Ragin, C.C., Eds.; Sage Publishing: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihoux, B. Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA): Reframing the comparative method’s seminal statements. SPSR Swiss Political Sci. Rev. 2013, 19, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellamare, C. Città Fai-Da-Te. Tra Antagonismo E Cittadinanza. Storie Di Autorganizzazione Urbana; Donzelli: Roma, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mile, S.; Paddison, R. Introduction: The Rise and Rise of Culture-led Urban Regeneration. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; McGreal, S.; Berry, J. An evaluative model for city competitiveness: Application to UK cities. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Crossing the great divide: Coproduction, synergy, and development. World Dev. 1996, 24, 1073–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutional and economic growth: An historical introduction. World Dev. 1989, 17, 1319–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualini, E. Planning and the Intelligence of Institutions; Ashgate: Aldershot, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, P.A.; Taylor, R.C.R. Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Stud. 1996, 44, 936–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, S.; Chiffi, D. Complexity and Uncertainty: Implications for Urban Planning. In Handbook on Cities and Complexity; Portugali, J., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Northampton, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions and economic theory. Am. Econ. 1992, 36, 3–6. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25603904 (accessed on 1 April 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ferilli, G.; Sacco, P.L.; Tavano Blessi, G.; Forbici, S. Power to the people: When culture works as a social catalyst in urban regeneration processes (and when it does not). Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 25, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glackina, S.; Dionisio, M.R. ‘Deep engagement’ and urban regeneration: Tea, trust, and the quest for co-design at precinct scale. Land Use Policy 2016, 52, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, S.R.; Iaione, C. Ostrom in the city: Design principles and practices for the urban commons. In Handbook of the Study of the Commons; Cole, D., Hudson, B., Rosenbloom, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 235–255. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3130087 (accessed on 1 April 2023).

| Background Conditions Combinations | Outcome | Suggestions |

|---|---|---|

| Three or more background conditions with high qualitative value | Robust (successful) | Building location: work on the communication of the process and maintain close contact with the neighbourhood to address its needs. |

| Medium qualitative value within three conditions | Fragile | Community-building: civic actors have to be recognised, and each step is dedicated to building trust with local authorities and citizens. |

| Less than three conditions with high qualitative value | Fragile | Co-production: The role of civic actors is strengthened through ‘community building’, and their commitment needs to be recognised by the public administration. It is necessary to work on communication and establish arenas and discussions for creating a ‘win-win’ scenario. |

| Low qualitative value conditions | Failure | Political continuity: the revitalisation process needs to be attentive to potential risks continuously, and civic actors have to anticipate them through co-production and other communicative activities. |

| Socio-economic environment: Revitalisation processes have to be considered in the long run, recognising that some contexts are more prone to these activities than others. The development and feasibility of the process should be carefully assessed before activating, taking into account potential failure. All the other background conditions should be taken into account. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bellè, B.M. Background Conditions for Revitalisation Processes in the Case of Unused Public Buildings in Italy: An Ostromian Perspective. Land 2023, 12, 1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12061166

Bellè BM. Background Conditions for Revitalisation Processes in the Case of Unused Public Buildings in Italy: An Ostromian Perspective. Land. 2023; 12(6):1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12061166

Chicago/Turabian StyleBellè, Beatrice Maria. 2023. "Background Conditions for Revitalisation Processes in the Case of Unused Public Buildings in Italy: An Ostromian Perspective" Land 12, no. 6: 1166. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12061166