Abstract

This paper explores the issues connected between rural sustainable development in formerly state-socialist countries and the local cultural heritage of rural areas. It pays specific attention to the potential of cultural tourism which can enhance local rural development. This paper is a case study of the Hărman commune, and this area is investigated in depth. It is one of the most important rural and cultural areas located in Brașov County of Romania, a country with an impressive cultural heritage concentrated in its rural areas. The study uses a mixed-method analysis combining quantitative and qualitative research (focus groups, interviews, oral histories, and personal conversions), participatory ethnographic observation, and logical framework analysis (LFA). The main findings of the study illustrate that the Hărman commune has an important cultural heritage which could be more capitalized on in the future through the lens of cultural tourism to ensure local sustainability and to open up new perspectives in terms of local development, connecting rural and cultural tourism with other economic activities. Furthermore, the main findings of this study represent, beyond an informative platform for the local actors in rural development, an inspiring instrument that could frame new policies in local rural sustainable development and fertile backgrounds for new debates in local rural sustainability, enriching local agendas on rural sustainable development through cultural heritage capitalization and cultural tourism.

1. Introduction

This paper focuses on the close connections between sustainable local development in rural areas through the lens of cultural heritage capitalization and cultural tourism. The specific attention drawn in this study is based on the certain reality that rural areas still remain overlooked in the present scientific debates, especially when it comes to certain case studies, and, on the other hand, considering the local cultural heritage of rural habitats as important resources which could capture more attention from the side of various scholars. Against such a background, according to the Romanian Institute of Statistics (2019), Romania remains a country with an impressive number of rural settlements, with more than 40% of the Romanian population concentrated in rural areas [1], and a significant cultural capital, which is largely under used. Moreover, these aspects have to be wisely explored because they have the strength to ensure and to maintain local rural sustainable development. The core argument for such approaches is pointed out by a large variety of studies focused on the Romanian rural background when it comes to local tourism and rural development [2,3,4,5]. The sustainable development of rural areas through tourism represents a key factor in local, regional, and national development [6], and the cultural heritage of rural communities as well as cultural tourism remain the main resources and instruments for significant opportunities for rural local development. This is because their capitalization has the power to sustain local economic development, turning rural spaces into attractive places for both tourists and investors. Against such a background, rural tourism could enhance socio-economic development and the local regeneration and renewal of rural settlements [7], generating the stimulation of agricultural development, the appearance of new local enterprises and even small industries, the stability of the local inhabitants, and an increase in quality of life at the local scale, all ensuring sustainable rural development [8,9,10,11,12,13,14].

Considering these, since local cultural heritage remains an important resource in local rural development through tourism and, particularly, through cultural tourism, it has to be included in the local agendas of rural development because cultural heritage “might help future generations to solve important challenges” [15] (p. 12). Cultural heritage and cultural tourism, as an economic activity which leads to local sustainable development, have the strength to provide multiple opportunities for local rural sustainable development because rural habitats are places with particular cultures and cultural heritages which could attract a large number of visitors interested in discovering the local cultures of certain places. Cultural resources are important attributes of different rural places, contributing both to local economic development and cultural tourism as a specific activity with multiple opportunities to ensure local rural sustainability [16,17]. In this regard, tourists’ choice of heritage sites in rural areas represents a key aspect for local development which must be considered and capitalized on by the local authorities [18,19], as well as the local perception of tourism development through particular conceptual frameworks for the local sustainability of places [20]. This is especially true for rural areas which are significant cultural hearths for different types of cultural traits, traditions, customs, and other forms of present cultural heritages. Since tourists and visitors are continuously interested in new experiences and destinations [21], the cultural resources and heritage of rural places provide interesting cultural sites for all those interested in authentic local cultures. Taking into account this relevant aspect but without going so far, we consider that cultural heritage could also inspire contemporary local actors to solve some issues in local development, especially when it comes to rural areas and their related sustainable visions in terms of their social, economic, and cultural progress. Cultural heritage could be approached from different perspectives, from visions to real practices and sustainable interventions [22,23,24,25] for local communities’ development. In this regard, cultural heritage has an important economic impact for places making a close connection with tourism, especially cultural tourism [26,27]. This is because local culture has an important economic value since all cultural traits, artifacts, buildings, and old architecture, the popular customs and practices, and the local ways of life of rural populations are important resources which can be successfully used and capitalized on in order to provide local rural communities with new perspectives in ensuring both a sustainable future and local development based on the local material and immaterial cultures. In this regard, local cultures through tourism and its related economic activities become an agent in local sustainable development [28,29].

Consequently, cultural tourism, as an economic activity, could represent the main process of ensuring local rural development through the lens of sustainable visions and practices in rural regeneration. Moreover, cultural tourism might be a sustainable activity itself for the local development of places, enhancing quality of life with multiple benefits and having positive impacts for local communities. It establishes close connections between places, tourists, tourism, and the stakeholders as well as various local actors, thus turning into a specific framework for both spatial planning and the communities’ management, providing multiple local attributes for the sustainable development of places [29]. Whether urban areas benefit from this mentioned framework or not, rural habitats are still overlooked by this perspective in their local sustainable development.

This is the main argument which legitimizes the present study that is focused on the close connections between rural sustainable development, the cultural heritage of rural areas, and cultural tourism, considering, as a case study, one of the most important villages from Brașov region of Romania, the Hărman commune. In terms of its cultural tourism potential and local cultural heritage, it is a place where important cultural material and immaterial resources exist. It has to be critically explored for designing an appropriate framework for the further local sustainable development of this rural habitat. This paper is structured as follows: first, a theoretical background is designed to understand the main concepts, processes, and characteristics which rural areas deal with in line with both rural sustainable development and cultural heritage; second, the materials and methods are presented, generating the general methodological flow of the study; third, the study area is presented, contextualizing the chosen case study; and then, in the fourth section, we unveil the main findings and discussions of this study. We aim to portray a general model for applying this type of investigation to other similar rural areas, providing all those interested, especially local and key actors in rural development, with some major perspectives in enhancing visions and practices for local rural development through the lens of local cultural heritage and cultural tourism. This study opens up new avenues for further fertile academic dialogues to emerge which are focused on rural sustainable development and cultural heritage, which defines each place with specific cultural identities.

2. Theoretical Framework: Sustainable Rural Development in the Contexts of Local Cultural Heritage and the Cultural Tourism Potential

Sustainable development is more than a complex concept of our contemporary times. It represents a functional instrument and a political background which must be approached in its integrity and be used in the critical analysis of local development. Sustainable development has to be foreseen as an integrative vision for the social, economic, and cultural progress of all communities in order to ensure proper welfare of communities’ futures, whether they are urban or rural, as well as for the next generations. Sustainable development in its broadness is involved in all fields and scales from economic to social, cultural, and political backgrounds and from local to regional, national, and global, advocating for real justice and equity between development and environment [30] including all its features and potential (from natural to cultural and anthropic). It also involves an appropriate management of communities’ development and environmental features, including, among others, the population and their quality of life, environmental resources, agriculture, and policies, the latter referring to participatory development, social, and economic contexts, and natural resources [31].

Sustainable development in all its conceptual complexity belongs to the ecological paradigm with multiple cultural and contested understandings. It connects social and environmental justice and sustainability processes with politics and governance [32] to ensure a balanced development between communities, societies, and environment; in summary, an ecological equilibrium which fosters economic development in the long run [33]. This economic progress, as well as sustainability itself, are foreseen for both urban and rural communities in their attempts to evolve in line with all the sustainable demands. Against such a background, since urban areas or regions, as significant consumers of energy, are largely investigated through the lens of sustainable development, due to their complex issues which have to be solved to ensure their inclusivity, safety, resilience, and sustainability [34], the discourses of sustainability in rural areas are in a secondary background. This status requires a re-position of these aspects because rural habitats remain important communities, spaces, and places with relevant resources from natural to demographic and cultural whose identities provide new opportunities to ensure sustainable progress on the whole. All the more, in these debates, culture and cultural backgrounds must be critically approached as real tools for ensuring places’ sustainability because cultures themselves contribute to local sustainable development [35,36]. Consequently, culture becomes the fourth pillar for sustainable development [37], and rural communities remain important cultural reservoirs. They could be capitalized on through cultural heritage valorization and through cultural tourism since these activities are straight integrated both in economic activities and in the political management and governance of the settlements’ development. Cultural policies for sustainable development generate important new paths [38] for local development, including, certainly, cultural backgrounds as new avenues to ensure local welfare. The sustainable development of rural areas has led to the local progress of rural settlements, maintaining environmental justice and real equilibrium between anthropic features and nature and its components. In rural areas, economic sustainable development provides stability for local inhabitants and fertile backgrounds for further investments, ensuring the protection of the local environment. Considering local pillars of economic, environmental, and social governance, rural areas could be faced with important progress based on different economic activities, of which rural tourism, sustainable tourism, and agritourism are important economic activities [39]. They enhance local rural development and rural communities’ welfare. There are many rural areas which rely on various non-agricultural activities and rural economies, capitalizing on nature and culture as specific features of local management based on knowledge and resources, on natural conservation and biodiversity, as well as on resource-based management and strategies [40]. In the context of different forms of the sustainable management of rural areas, local cultural heritage and cultural tourism are the main pillars for local rural progress in social and economic sectors and in the cultural one, reinforcing and sustaining the local cultural identities of rural habitats. In terms of sustainable tourism, as an activity leading and promoting sociocultural progress and economic development based on local resources capitalization [41,42,43], cultural heritage has an important role to play alongside the natural resources of a place, which could be together used to maintain both the economic progress of a rural area and sustainable development which relies on the various facets of tourism, particularly cultural tourism. The cultural heritage of a place includes both material and immaterial resources which, in modern society, attract a large number of tourists and visitors whose interests mean that they are able to engage in related processes of local investments, services-led activities development, and infrastructure development; in sum, the local welfare of a place. Cultural heritage is the main legacy of places which frames the specific cultural identities of rural areas. The rural way of life of a community, cultural traditions, customs and popular art, rural manufacturing, produces and food, rural architecture, folk art, and rural architecture and landscapes are the significant attributes of a place which sustain rural tourism and the emergence of cultural tourism in terms of local rural sustainability.

In addition, particular forms of rural tourism, such as ecotourism, agritourism, and cultural tourism, in terms of their sustainability, are responsible for ensuring appropriate local development and welfare whether they are properly foreseen as ways of action in local development strategies and objectively capitalized on in local economic backgrounds. It is widely acknowledged that ecotourism represents a touristic niche promoting the care of natural environment and society, thus generating a specific culture with respect for nature and for physical or cultural landscapes with multiple opportunities for ensuring local sustainable development [44,45]. In the same vein, agritourism, as a touristic activity, is a means through which local cultures, in terms of traditional practices and cultural traits of local ways of life, are also relevant in local sustainable development [46], especially in rural areas. Both touristic niches are framed by local cultures and local cultural resources involving cultural heritage as a mean for local economic development through cultural tourism, the latter being seen as an integrative form of all the cultural resources of a place [47,48,49,50]. It captures tourists’ and visitors’ attention and interest. Consequently, between cultural tourism and local cultural heritage, a strong connection is established [51] because cultural heritage “consists of manifestation of human life which represent a particular view of life and witness the history and validity of that view. The expression of culture or evidence of a way of life may be embodied in material things such as monuments or sites”. It also includes archeological sites, human-built structures, and spatial evidence of the past which must be preserved [52] (p. 307). Cultural heritage includes important features of material and immaterial culture belonging to different periods of time which have to be preserved. Cultural artifacts, cultural objectives, and monuments of the past are a few examples of things which enrich cultural landscapes and must be protected and wisely consumed to maintain both their sustainability and that of the places where they exist. In this regard, cultural heritage calls for protection, preservation, and conservation [53] as well as for sustainable and rational usage in touristic activities and through tourism. Accordingly, the creations of human beings are features of the cultural heritage of a place and they must be protected and preserved [54]. At the same time, they have to be properly and carefully included in local strategies and policies on local development. This is because it represents the culture itself of a place, providing unique cultural identities. Nevertheless, cultural heritage remains an important resource for both local sustainable development in rural areas as well as for the emergence of cultural tourism in order to generate the socioeconomic and cultural progress of a rural place through appropriate management [55] and through the application of adequate strategies to local practices in rural development.

Consequently, between rural places and their sustainable economic development, the cultural heritage of rural habitats, and cultural tourism as an economic and cultural activity, a strong connection is established, them having to be addressed together because in the context of cultural tourism, a partnership between tourism and cultural heritage management is appointed [56]. Cultural tourism as “one of the oldest forms of special interest tourism” [57] (p. 8) is currently one of the most important economic activities which leads to the economic development of a place in terms of present sustainability. Historical sites, cultural landmarks and events, art and architecture, the local ways of life of residents, and the cultural identity of places in close relation with the cultural landscape are all local features which could be capitalized on in order to ensure sustainable rural development. Cultural tourism has the strength to enhance quality of life, optimizing multiple benefits for local communities. For this, cultural heritage management is required as well as local strategies which aim to develop the cultural background of a place in terms of economic sustainability. Beyond local governments and various responsible institutions, stakeholders play a key role in managing cultural heritage (both tangible and intangible) as well as in the local and regional tourism markets where the cultural assets of a place could be successfully turned into tourism products, transforming places into cultural spaces. Applying cultural tourism in local sustainable development requires a specific framework for understanding all the things which are necessary to understand to design a successful attraction [2,5,22,32]. In this regard, an objective assessment of the cultural resources/cultural heritage of a place is mandatory in line with the main related processes, activities, initiatives, and actions which have to be completed for designing a certain attraction. The mission and visions for such a specific approach involve particular activities in terms of the planning and usage of realistic management frameworks in order to envision positive feedback even though various challenges remain [57] when opening new opportunities for local development through the lens of cultural heritage capitalization and cultural tourism. Nevertheless, as Du Cros and McKercher argues [57], cultural tourism represents one of the most important economic activities which directly contributes to local development through cultural heritage capitalization and the application of adequate policies and management in local communities’ strategies for local social, economic, and cultural progress. This aspect is also sustained by Ivanovic [58] (p. 15), who stated that “culture has been an integral part of human evolvement, inseparable from our existence and development.” Consequently, the cultural resources and heritage of a place are important for the present and future sustainable development of a place. In the same vein, Richards points out that “culture and tourism have always been inextricably linked. Cultural sights, attractions and events provide an important motivation for travel, and travel in itself generates culture. But it is only in recent decades that the link between culture and tourism has been more explicitly identified as a specific form of consumption: cultural tourism” [59] (p. 12). It has an important role to play in the tourism industry [60] and economic development, thus directly contributing to the local progress of different communities regardless of their type, size, or form. Therefore, cultural tourism as a specific economic activity is acknowledged in the recent scientific literature as a means which successfully contributes to local economic development following the main trends of contemporary sustainability, enhancing the local welfare of communities as well as their life quality. Considering the main discussed theories, we must highlight that between cultural heritage and local sustainable development, a close connection establishes, with cultural tourism being the main process in ensuring the social and economic progress of communities on a local scale. Against such a background, the next section of this paper unveils these aspects considering a particular case study of an important Romanian commune with an interesting cultural heritage which is often overlooked in scientific discourses and academic dialogues.

3. Study Area and Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area

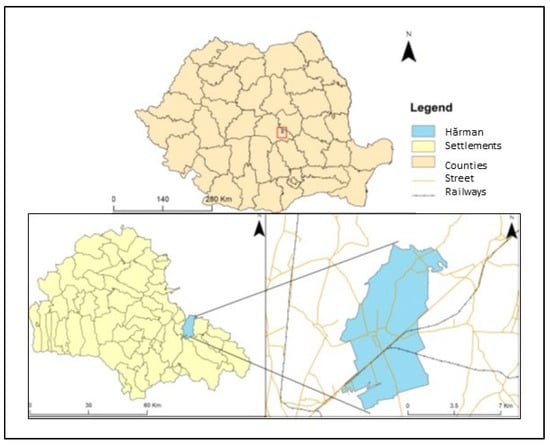

The Hărman commune is located in the proximity of Brașov city (10–11 km away) in Brașov region/County. It is placed in the central part of Romania (Figure 1) in the cultural and historical area called Bârsei Land, a place with an impressive cultural heritage and historical values which belong to the various periods of time of the past [61,62]. Important cultural resources are also present in the commune of Hărman, of which the most significant are the local citadel, the fortress, and the fortified church [63], all being placed in a unique natural and cultural landscape framed by inter- and multi-culturalism (Figure 2). Located in one of the most important touristic regions of Romania and with an impressive cultural heritage mostly under-utilized in local economic development, this commune provides an interesting cultural background efficient for both local and regional sustainable development based on new strategies connecting local cultural heritage, cultural tourism, and local development in terms of contemporary sustainable demands.

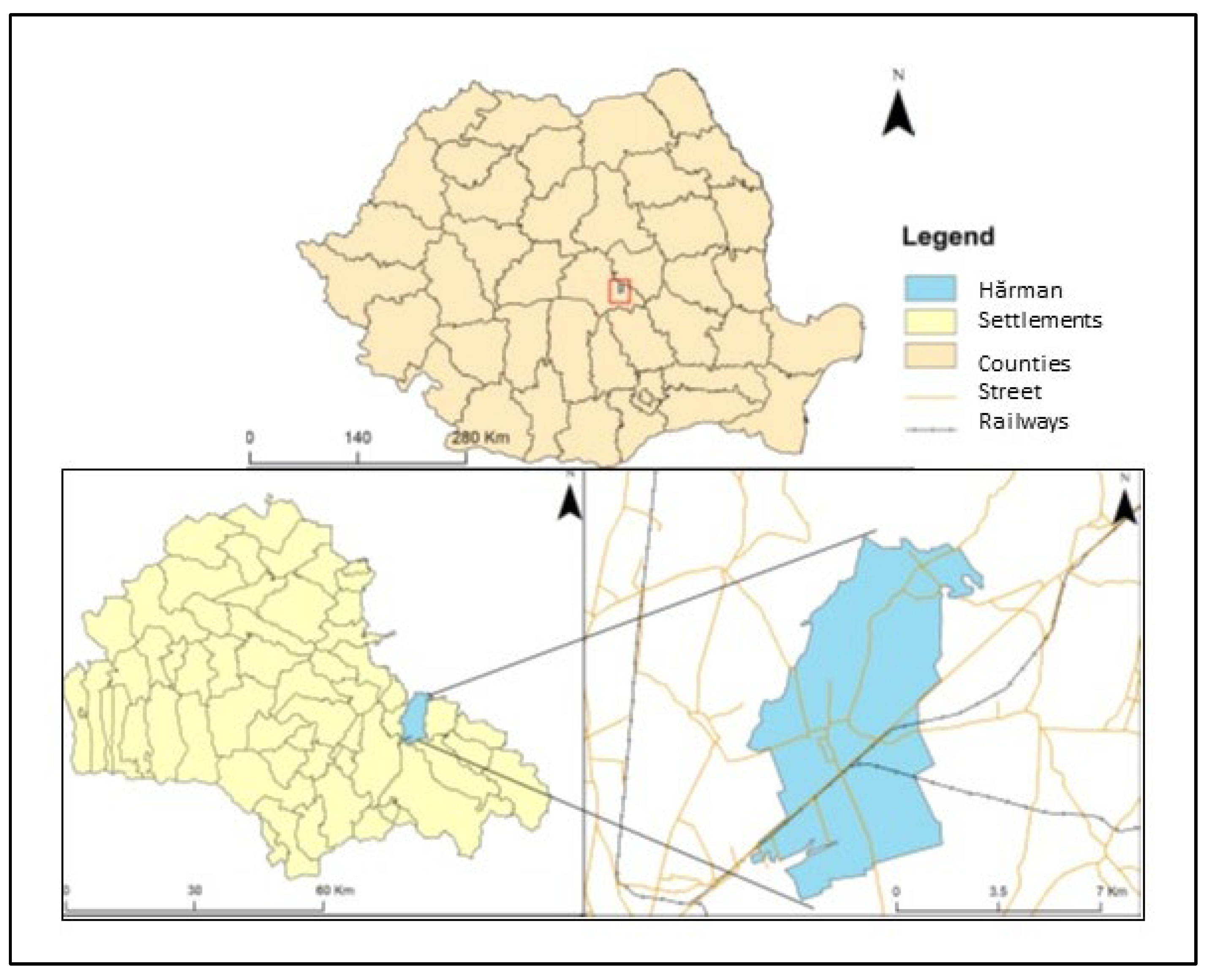

Figure 1.

The geographical position of Hărman commune in Romania and Brașov County (source: authors, 2023).

Figure 2.

The geographical position in the natural environment of Hărman commune with the historic fortress placed in the middle part of the village and Lempeș Hill situated in the backward part of this place (source: authors, 2022).

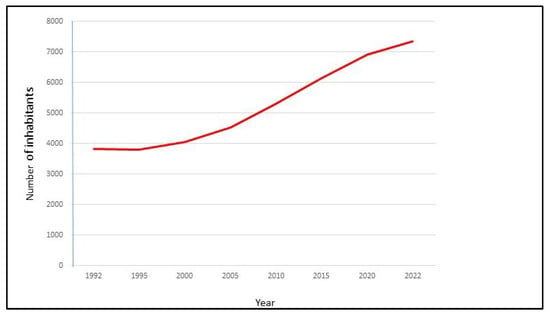

Furthermore, this rural settlement registers positive economic development argued by its continuous growth in terms of the total population increasing from 3830 to 7341 inhabitants in the present day [64], which is an increase of about 50 percent; this number has practically doubled in the last three decades (Figure 3). This demographic background illustrates, on the one hand, the stability of the rural population (in a national context where the rural population is in a continuous decline), but also the attractiveness of the commune for people. Against such a background, the commune remains attractive for various investments, of which cultural tourism, through internal cultural heritage, could be one of the most important key economic processes which could permit sustainable development in this rural community.

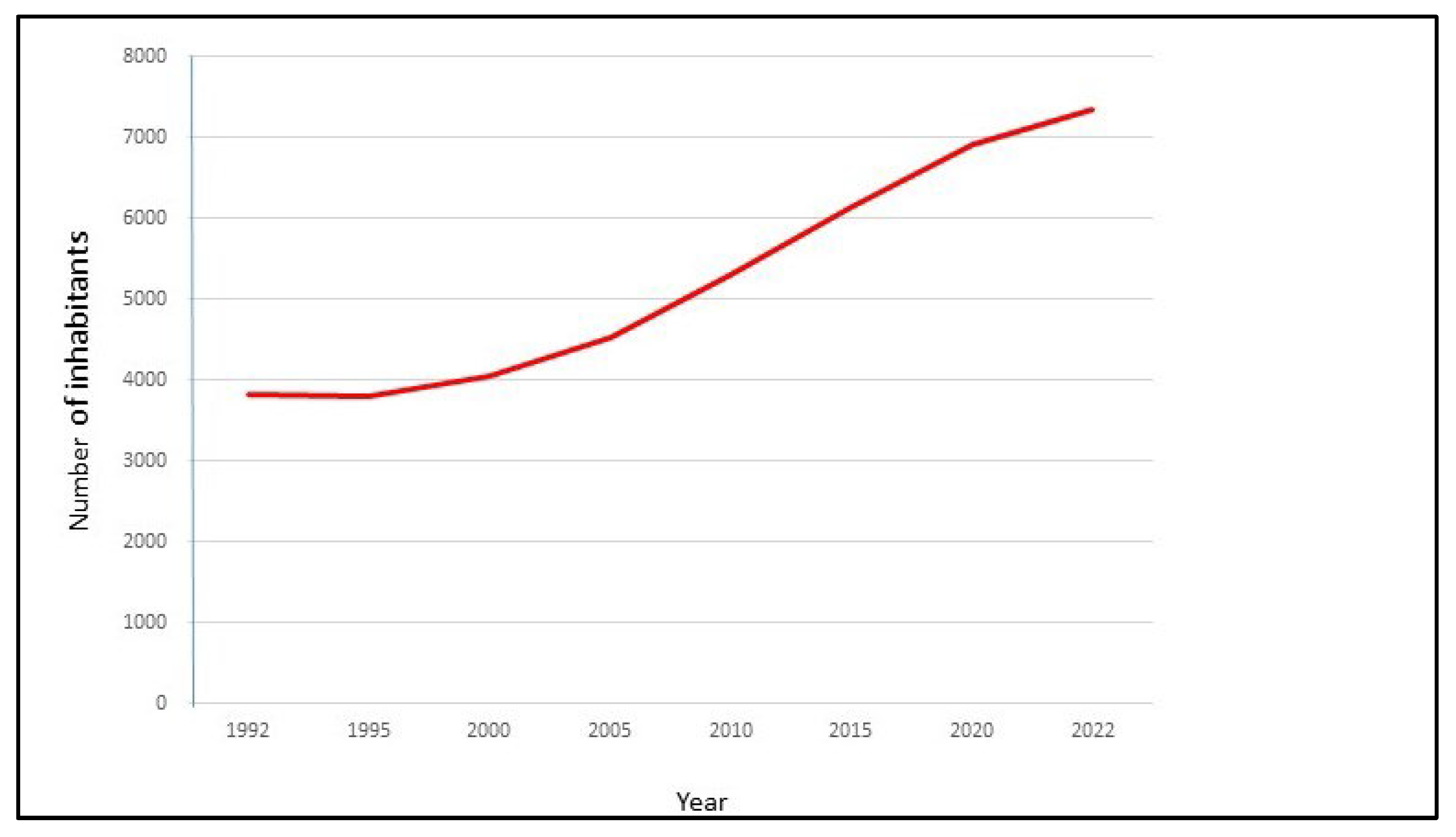

Figure 3.

The increasing number of the population in Hărman commune in recent decades (according to INSEE, Romania, tempo online databases, 2022) [64].

3.2. Methodological Flow of the Research to: Materials and Methods

This research uses both quantitative and qualitative methods. The first step of the investigation was the careful and critical analysis of the available literature which previously focused on this location. This method is legitimized because reading cultural texts and literature reviews regarding different places and spaces is mandatory in the current scientific research regardless of the approached topics. Furthermore, it grants the fundamental contents and main findings of a specific topic [65,66]. Then, an infield participatory and ethnographic observation with repeated visits and observations was made in 2021 and 2022, and this was useful for understanding the local cultural background of the commune as well as to perceive onsite the cultural features of this area. A participant observation is an important scientific infield tool used in order to objectively capture the main features of a place [67,68]. Multiple visits were efficient both in gaining an understanding of how cultural heritage is perceived and how it could be further explored and capitalized on to sustain local economic success and to maintain local sustainability. The visits provided a general background to objectively perceive the cultural landscape and multiple opportunities to discuss with local residents and tourists in this village. Considering a qualitative approach, semi-structured interviews and focus groups are relevant methods used to identify significant findings and results based on direct approaches of various subjects [69]. Three focus groups were conducted in 2021 with local residents, domestic tourists, and foreign visitors in order to capture the main issues regarding capitalization on local cultural heritage as well as these individuals’ perceptions and opinions towards cultural tourism as an efficient economic process for local sustainable development. In order to respect the academic ethics of this method and to anonymize the respondents’ names, the main aspects provided by the focus groups members are referred to as R1 to … Rn. A semi-structured interview was conducted with a representative stakeholder regarding the present and future perspectives of local economic development trends based on local resources and the main economic activities developed in Hărman during the last decade.

To portray the spatial distribution of local cultural features, local cultural resources were carefully mapped and placed on professional maps using GIS tools; this methodological flow allows spatial realities on the investigated sites to be mapped [70]. The main perspectives of the local authorities towards economic sustainable development were considered using official documents, analyzing, in a critical manner, local development strategies and rural development plans. This methodological approach, which considers the usage of government records for research, and policy document analysis are appropriate when it comes to the study of local development in line with the political background of certain places, aiming to elucidate specific perspectives in the local progress of different communities [71,72]. These documents were useful for determining the rural management applied to the local strategies of rural development as well as to the local initiatives, actions, and projects developed in this regard. As we can see in Figure 4, the Local strategy of rural sustainable development was designed in line with the durability requirements of places for the period of 2021–2027, which is largely connected to both the European demands of local development as well as to the international policies applied for sustainable rural development [73]. It particularly focuses on, from macro scales to local ones, the main interventions in order to sustain rural sustainable development. This official document represents the main background for local economic development on which local management is based. Special attention was paid to the national context in rural development and to regional and local spatial and economic specificities which together aim to accomplish the main objectives of sustainable rural development, of course including here local economy, tourism, and cultural tourism as means for ensuring the local progress of the investigated community. The local government emphasizes the importance of sustainable development through practicing significant initiatives in this regard. Finally, to validate the main findings, the logical framework analysis (LFA) method was used as a synthesis, which is largely recommended in territorial systems studies, in order to sketch the main issues of the investigated case study [74,75]. The LFA method is based on the main results provided by the previous steps of the methodological flow used in the study. It illustrates relevant key aspects in the local planning of sustainable development. It is also frequently used in local strategies on the social and economic development of a place, either rural or urban, and it is meant to achieve and accomplish higher objectives in local initiatives in communities’ sustainable development. Furthermore, the LFA is an instrument which has the power to improve all initiatives in local development [76,77,78,79] through the lens of the sustainability of all the involved systems (planning, economy, resources, initiatives, practices and outcomes, etc.). Finally, the method also represents an instrument of validation and verification, highlighting how the main findings could be successfully used in local planning initiatives to sustain communities’ development.

Figure 4.

The local strategy of sustainable development of Hărman commune. In order to argue sustainability in local development, the image illustrates that this official document is focused on the sustainable local development of this rural settlement. Source: http://www.primariaharman.ro/portal/brasov/harman/portal.nsf/F7D2413216E0D4ACC2258791003E5A5F/$FILE/Strategia%20de%20dezvoltare%20durabila.pdf, accessed on 20 February 2022.

This methodological design was used for the selected case study without ignoring the national and regional contexts, for which the next section of the present study portrays the main aspects of the general cultural background in the national and regional contexts of Romania, where an in-depth analysis of Hărman village is unveiled.

4. Results, Findings, and Discussion

4.1. Contextualizing the Cultural Heritage of Romania

Romanian rural settlements have an impressive cultural heritage which, in the face of the urban dynamics analysis, is frequently overlooked and under-studied. Rural habitats are settlements hosting important cultural backgrounds, unique cultural landscapes, and specific cultural features and resources which must be considered in the contemporary sustainable development of rural areas through cultural tourism and cultural heritage capitalization. As it is largely argued, “Romania is a European Country with a remarkable potential for tourism, a potential that has sustained and will continue to sustain the development of tourism industry, as a basis for the economic development of a number of areas in the Carpathians” [80] (p. 7). National cultural background is based on cultural periods of time and on history itself, which has largely marked this part of Europe since ancient times. In this regard, relevant cultural features date back to antiquity and to the Middle Ages, these making interesting resources to belong to pre-modern and modern stages. Moving forward to the present day, even the state-socialist period has the chance to change the cultural landscape of villages. With new features in the local architecture, the rural landscape of villages show, to a larger extent, its resiliency with multiple cultural resources remaining up to now as witnesses of different periods of time belonging to various overlapped cultures. There are multiple cases where countless cultural objects, buildings, or parts of them still remain present from the ancient times of antiquity. The same applies for numberless vestiges dating back to the Middle Ages, which fully illustrate the cultural system of this historical stage mirrored in the cultural landscape [80]. Alongside these cultural vestiges, other resources join. The housing stock, with beautiful and unique houses and dwellings in a German style, is present, turning local architecture into attractive assets which could be better capitalized on for local development through cultural heritage valorization and cultural tourism. Then, there are multiple artifacts and material cultures belonging to ancient times as well as interesting and fascinating popular customs, traditions, and various activities belonging to the local rural ways of the life of inhabitants. Cultural events, religious manifestation, local celebrations, and different specific popular festivals enrich rural cultural patrimony as well as land and agricultural cultures. They are very attractive for people, visitors, and tourists with these resources being less represented and eventually absent in occidental European cultures. Romania in its rural settlement still embraces multiple rural cultural resources with an impressive interest for foreign tourists. In addition, rural cultural landscapes are enriched with relevant and impressive natural resources whose juxtaposition with anthropic cultural features generates unique cultural landscapes which are frequently unique and similar only with themselves. In this regard, unicity remains one of the most important characteristics of the local rural and cultural tourism potential [81]. The natural potential could be approached in cultural terms [82] since the cultural geomorphology of a place as well as geodiversity are closely connected with the people and communities’ ways of life at local and regional scales. The same applies to the local cultures of water which determine certain ways of life, practices, landscapes [83], and unique traditions in local practices or rural habitats. The natural features are harmoniously combined with anthropic cultural resources, determining unique cultural landscapes which can be successfully capitalized on through cultural tourism; Figure 5 legitimizes this argument. Within these aspects, rural activities, in terms of local agricultural practices and the land of the farms of a particular culture, successfully join in enriching local cultural resources in rural settlements.

Figure 5.

The natural and cultural landscapes of Romania and Brașov region (photos taken by the authors, 2022).

Consequently, various forms and types of tourism could be considered for further initiatives and practices in local sustainable rural development through cultural heritage and cultural tourism, such as recreation and entertainment tourism through cultural resources and features, ecotourism and agritourism, sports, music, and ethnographic tourism, tourism for cultural events and cultural practices, indigenous tourism, tourism for art and architecture, visits to cultural sites, religious tourism and pilgrim tourism, and traditional, folk, and popular art consumption [84]. These are only some of the samples which could be successfully used as local cultural resources, contributing to the local sustainable development of rural areas as well as to cultural tourism development based on cultural heritage.

This argument is valid according to which local cultures are inextricably linked to nature, the environment, and the natural tourism potential and vice versa, producing specific and unique cultural landscapes which straightly mirror the cultural heritage of rural places. Nevertheless, they claim that cultural tourism development will be able to sustain the local durability of rural habitats.

4.2. The Cultural Heritage of Brașov Region and Bârsei Land

Brașov region and Bârsei Land are spaces with an old history and countless cultural resources belonging to different periods of time. Some examples of the cultural heritage of this area include monumental architecture, cultural and historic objectives, old traditional fortified churches and fortresses, an old impressive German housing stock as a reminder of the colonization of the past, old schools, and inter- and multi-culturalism evident in tangible and intangible local cultures mirrored in the cultural landscapes. In addition, different cultural events, traditions, popular folk art, religious landscapes closely connected to a wider set of cultural manifestations, popular fairs, and specific ways of life (according to a large variety of natural resources) frame a unique cultural identity to this region with its rural habitats waiting to be being discovered. Rural villages such as Bran, Bod, Simon, Hărman, Prejmer, Predeluț, Cristian, and Feldioara, to selectively name a few, or small towns such as Rupea, Codlea, Ghimbav, Zărnești, etc., all unveil an impressive cultural tourism potential which also has to be considered, discovered, promoted, capitalized, and used as an important cultural resource for sustainable rural development. Of these mentioned samples, the next section pays particular attention to our selected case study location—Hărman commune.

4.3. The Cultural Capital and the Cultural Heritage of Hărman Commune

To learn about the cultural capital and local cultural heritage of the Hărman commune, a visit through the past periods of time is mandatory. This rural settlement, located in the Brașov Depression, the so called Bârsei Land, within immediately proximity of the city of Brașov, one of the most important tourist cities of Romania and Eastern Europe, is documented as being attested in 1240. Consequently, it has an impressive historical heritage largely inserted in the local cultural landscape. The fortress church, built in a Romanic style in 1280–1290 and restored to a Gothic style in 1500–1520, the chapel with Gothic paintings dating back to 1460–1470, the old German-style housing-stock of the village from XVIII century, and Neolithic vestiges of Bronze and Iron Cultures are only some introductory examples. In the northern part of the village, the Hărman swamps natural sanctuary enriches the cultural landscape of the commune alongside eutrophic and glacial swamps in the southern part. The peasant fortress from this rural settlement is also a cultural resource enriching the cultural background of the village [85,86,87]. Throughout the cultural landscape of Hărman village, old buildings and historical monuments, picturesque streets and alleys, as well as a unique atmosphere continuously capture visitors’ attention. Of these, iconic places remain: Hărman Fortress and the Evangelic Old Church located in the middle of the village. The citadel is placed in the inner core of this rural settlement (Figure 6). Furthermore, a rural and cultural background also has the village Podu Oltului as a belonging settlement to Hărman from an administrative perspective. The Hărman commune has an important touristic potential as well as a dynamic touristic infrastructure with certain perspectives in terms of local economic development. All these are mapped and illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 6.

The fortress of Hărman commune placed in the middle of the village (source: authors, 2022).

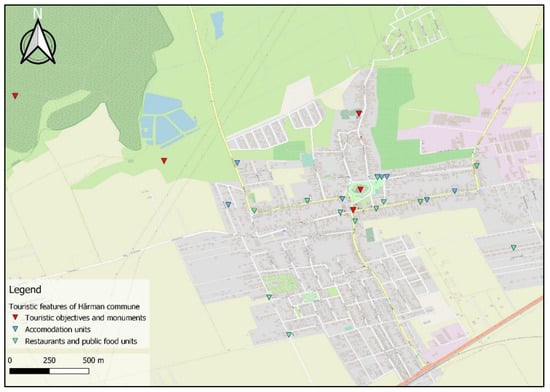

Figure 7.

Mapping touristic potential features of Hărman commune: the distribution of the main touristic attractions and of the main important touristic facilities (source: authors, 2022).

Aged more than 800 years, Hărman stronghold, the home of Teutonic Chevaliers, is now one of the most important in the Brașov region, including one of the most well-preserved churches from Bârsei Land. Historically attested in 1240, the architectural complex includes two main components: the fortress church and the fortification (Figure 7). The church is considered the cultural hearth of the place which, through restauration processes, changed its style from 15th century style to Gothic style. It has seven defense turrets and a spire. The fortification includes 4.5 m high walls to provide defense against enemies. The inner wall is twelve meters high with an alley on which the past guardians oversaw the area. As was the case with many Romanian settlements during state-socialist times, many cultural assets were altered.

Consequently, this place was implicitly affected, but the ensemble maintained to a larger extent its cultural and historical values and authenticity, evidence being the bell from the main entrance dating back to 1608. Nowadays, the fortress is well preserved, awaiting all those interested in visiting it to find out about this unique place from Bârsei Land [88]. But the general architecture is not just attractive; a glance at the inner site of the fortress unveils picturesque landscapes belonging to other times (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Images defining the cultural landscape of Hărman Fortress (inner and outer pictures illustrating the fortress architecture; photos taken by the authors, 2022).

These cultural and historical features are attributes of the Evangelic Church. Built in the 18th century, this makes the place part of an old Roman basilica. This is now attested as a historical monument in Romania (Figure 9). The church includes multiple historical vestiges and artifacts with impressive architecture both in terms of its general background and inside with old furniture and religious objects, interesting paintings, and attractive columns. It still hosts an impressive horologe and significant historical documents. The church is also an important venue for multiple celebrations and religious festivals which capture visitors’ attention through their authenticity. A significant part of the picturesque nature of this church is represented by the supply pantries [89,90,91]. The general plan of this architectural fortified aggregate is illustrated in Figure 10; it unveils through its structure and design historical authenticity as well as the cultural legacy of ancient times. This architectural complex, as a significant cultural objective and monument, is considered one of the outstanding elements of heritage of Transylvania and Bârsei Land. When visitors pass the fortress gate, it seems as if they have stepped into a timeless space going back through the centuries, into an emblematic and unique space with old elements and artifacts reminiscent of the old ways of time; old barracks, spindles, traditional clothes, music, and instruments are only a few of the objects which demonstrate to visitors the old local history and ancient legends of this place [92]. In summary, it portrays the local cultures and cultural heritage that the entire region of Brasov encompasses [93,94,95].

Figure 9.

Inner images of the cultural and religious background of the Evangelic Fortified Church of Harman; photos taken by the authors, 2022.

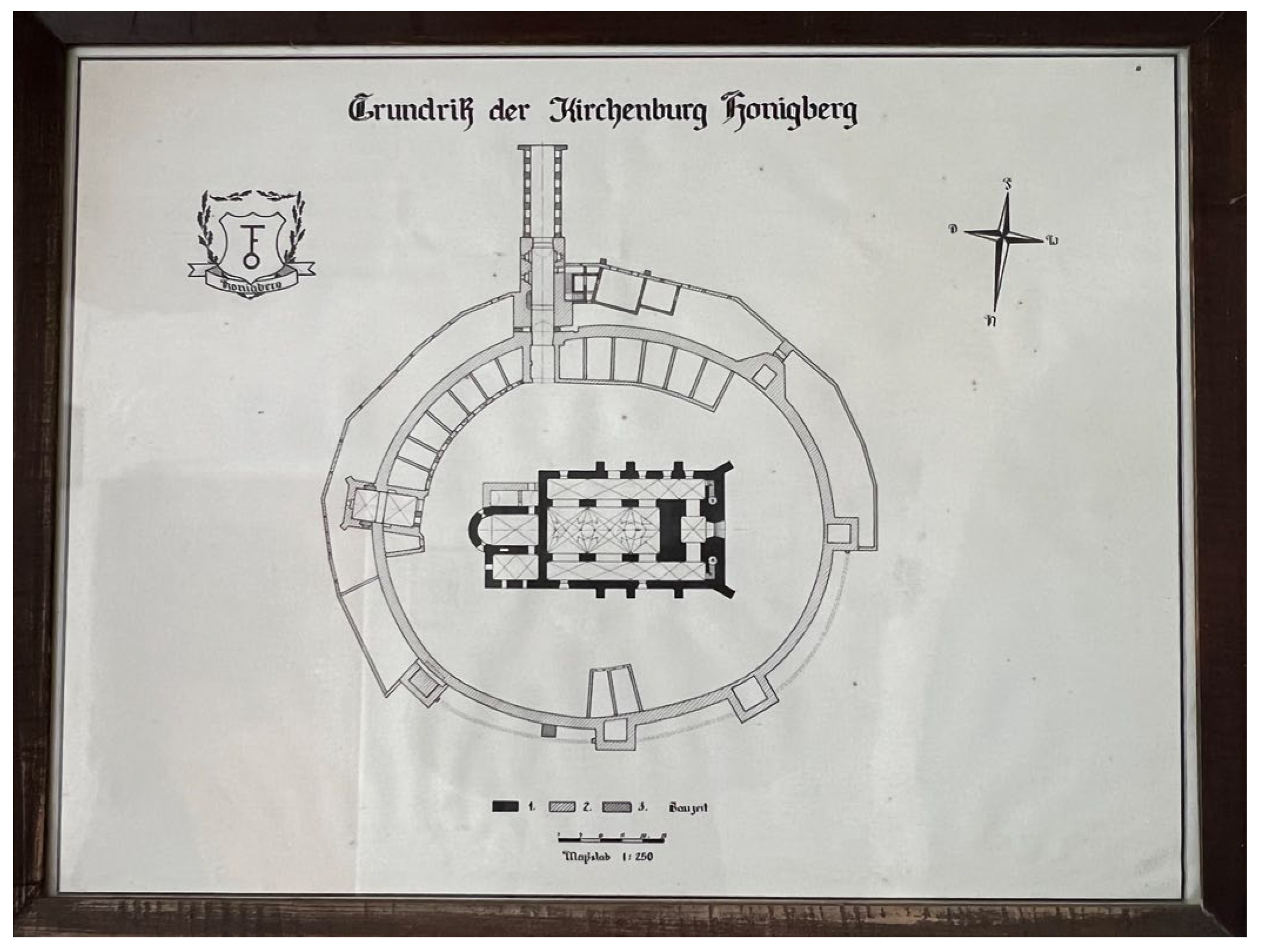

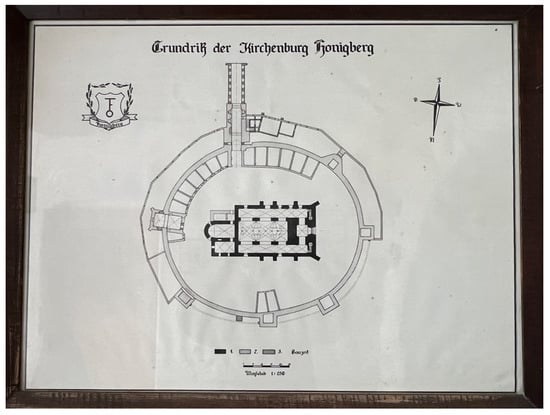

Figure 10.

The plan design of Hărman Fortress (photo taken by the authors after an exposed plan advertised in the inner area of Hărman Fortress, 2022).

The rural landscape specificity of the Hărman commune in terms of cultural tradition and architecture is also mirrored in the housing stock with beautiful traditional houses and dwellings built in a German style, with many of them being built in the 19th century, thus conferring to the villages’ streets both a unique aspect and a beautiful cultural and architectural design. The old houses are generally small- and medium-sized and well preserved. The atmosphere of the 19th century generates a particular and attractive landscape, providing a unique design across the streets. The houses presented in Figure 11 are just a few examples of this style, and they were constructed in the 19th century. Modest constructions with small windows and discreet ornaments are the main features of the housing of the old capital of the village. As in the previous case of architectural monuments, these constructions, to a limited extent, were altered during the state-socialist period, or, on the other hand, new standardized buildings were built, thus profoundly altering the local landscape. The block of flats in Figure 12 is evidence of this concern; however, to a larger extent, the old housing style remains present, attesting old cultures in the local ways of life of the inhabitants.

Figure 11.

Old houses in German architectural style build in the 19th century (1873); photos taken by the authors, 2022.

Figure 12.

A state-socialist standardized block of flats chaotically built between the old houses (photo taken by the authors, 2022).

Both the cultural resources and natural features of touristic potential are considered by local authorities to be unveiled for visitors and tourists. This is only at the incipient stage since local tourism potential represents, according to the local strategy of development, an important avenue for the further sustainable development of the commune. In this regard, advertisements are being placed in the village center unveiling the commune’s natural tourism and cultural potential (Figure 13 and Figure 14).

Figure 13.

Touristic routes for tourists (photos taken by the authors, 2022).

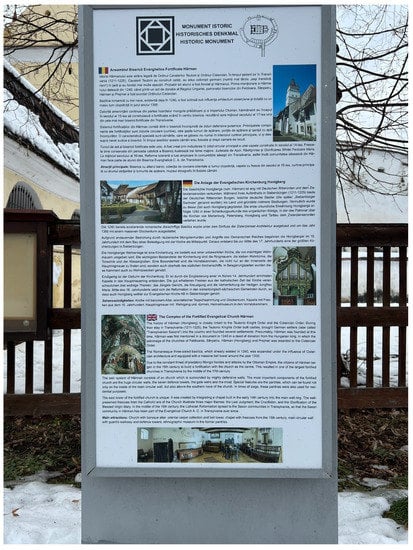

Figure 14.

Touristic advertisement about Hărman Fortress and Evangelic Church (photo taken by the authors, 2022).

To sum up, the touristic potential of the commune as well as the cultural tourism potential is fully sustained by local cultural heritage and cultural resources. The museum, hosted in a householder’s house, provides visitors and tourists with an important cultural collection of various objects which belonged to the local material culture and traditional popular art as popular or traditional clothes and objects of old furniture; all these original artifacts have been carefully collected throughout time. It is an important local venue for all those interested in cultural tourism. The City Hall of the commune is also an institution where business tourism with openness to cultural tourism could be considered as well as the local traditional houses and dwellings of local residents where traditional activities and practices are preserved in terms of cultural traditions, popular customs, and local folklore. All these are closely linked to particular ways of life. Against such a background, cultural tourism is sustained and capitalized on through the local ways of life of the people as a specific cultural resource.

The Evangelic church and fortress remain important attractions where cultural events, festivals, and various other activities could be successfully developed in close connection with various celebrations, from local celebrations to religious anniversaries specific to the Romanian traditional calendar. Last but not least, the local existing touristic routes in addition to new thematic touristic routes complete the general picture of the local cultural touristic potential which is largely acknowledged by the local people who live in this commune.

4.4. Perception on the Local Cultural Heritage, Cultural Tourism, and Local Sustainable Development

The cultural perception of a place represents a key aspect in determining the cultural value of a specific site or space. It is a defining instrument in a qualitative assessment of the landscape, nature, and environment. In this regard, perception on the local cultural heritage of the Hărman commune is a key tool for analyzing the value of the local cultural background of the village. In doing so, three types of individuals were selected in order to capture an objective perspective which triangulates the main findings discovered in the previous sections: local residents, domestic tourists, and foreign tourists. These were the main groups targeted, and their opinions will be unveiled in the next sections, completing the general picture framed by the in-field geographic observations, the main features which were geographically mapped, and the relevant results provided from a critical analysis of official documents. The main model for the present perceptual analysis was based on the individual perception towards local cultural resources and the cultural landscape of the Hărman commune from the perspective of local residents and tourists with subjective opinions of this rural place.

4.4.1. Local Residents Perception

A simple and ordinary walk on the silent and picturesque streets of Hărman village represents a great opportunity to meet simple people whose kindness and openness generate a fruitful background to find out interesting things about their native rural area in which they live day by day. An individual staying right in the front of his house stated that “This settlement is not an ordinary rural area because its proximity to Brasov, one of the most important Romanian city. Actually it is minutes away from the city for which it could be approached rather than a district and not a village. If you go straight ahead and turn left you can see one of the most important fortress from the region and beautiful buildings and houses in a specific German style. The general landscape of this village is more than rural, take a look…” (R1) and invited us to see Hărman Fortress surrounded by old beautiful and picturesque houses. The landscape is framed by a specific atmosphere in which visitors feel like they are going back in time, especially when they step inside the fortress. Another citizen stated: “this is an old commune with an old and authentic cultural heritage and full of history, annually attracting many visitors and tourists even for few hours” (R2). Such a statement portrays again the historical and cultural background of the commune. Beyond this material culture reflected in the local architecture, a woman resident pointed out that: “Not only what you see is important as a tourist. Please take a look at our ordinary traditional ways of life. We preserved many customs and traditions, part of these being available at the local museum of ethnography but please be advised that these objects are still present in our households. The visiting people are not familiar with these, but they are so excited to see them” (R3). This aspect is interesting since it completes the cultural landscape based on the old architecture of the village. Regarding the local landscape, another resident stated: “We live a picturesque settlement with a specific aura which is so simple to perceive but so hard to describe and to put it in words” (R4). This assertion, however, explains why the cultural landscape of a place is such a complicated attribute which can be so easily perceived but so hard to be explained or depicted in simple words. This applies when we consider the German spirit of the local culture being so easily reflected in the landscape but too complicated to unpack. This is because of “the long history of this place with multiple layers of time overlapping with each of this setting new cultural values” (R5) which were not altered in time. “Even communist period with its nationalization processes and the new brutal structures was not able to alter our local culture and particular tradition” (R6), stated another local respondent. This cultural background, as it was possible, has been fully used in recent decades. “Both in summer and winter many visitors come in this commune to face with the main cultural resources which define our culture and frame our rural identity and our place attachment which is based just on our beliefs and traditions” (R7). This unveiled aspect illustrates the reality of the local rural and cultural touristic potential which can be successfully used in local rural development since “in the latest decades many investments were made here thus influencing the local economic development of the commune including here the tourism: we have not cultural values and monuments but the commune disposes by pensions and restaurants which are largely enjoyed by the visitors” (R8), said another local, inviting us to taste the food of the local restaurants. In all, these aspects unveiled the real truth of the locals towards the cultural background of the commune, concluding with a specific trait of the village: “if you are here in evening you can see all the cattle coming to their homes which frame a totally picturesque image, now in a word of globalization and internationalization. Be advised that tourists from the cities and towns are fascinated by this cultural specific landscape—even so old it is very attractive in our modern world” (R9). In this regard, we can critically conclude that in a postmodern world, frequently articulated in the contemporary geographies of rural spaces, old local traditions, customs, and cultural values remain important in our times. They create the cultural identity of a place which could be capitalized on through cultural heritage and tourism for a place’s local economic development, thus enhancing the local sustainability of places and communities. Against such a background, tourists’ voices, however, resonate with the perception of the local residents. This aspect is unveiled in the next sections which are focused on tourists’ perceptions of local heritage.

4.4.2. The Perception of Domestic Tourists

The voice of the Romanian tourists and visitors has interesting and worthy echoes when it comes to the cultural resources of the Hărman commune and certainly could inspire local initiatives and decisions in the further economic development of this place through tourism. “The Lempeș Hill area, the fortress and the fortified Evangelic church are so attractive objectives and it is regrettably to not be visited once you are here. Such a picturesque area surrounded by a relaxing environment, simply a very nice place” (R1). This idea illustrates again the beautiful landscape of this place with different cultural objectives that have great potential and invite the interest of tourists and visitors. On the other hand, the local art is emphasized by other respondents, arguing that “the popular art of this settlement is interesting unveiling the local cultural traditions, folklore and popular customs” (R2), while another participant within the focus group stated that “the popular art and the local culture is also reflected by the houses and the local dwellings with the German influence being obvious in the local rural landscape” (R3). These assertions unveil the cultural tourism potential which enrichs the local landscape which could be capitalized on through various forms of tourism, alongside cultural or rural tourism. Considering this, it is argued that “this area is so appropriate for agri-tourism and ecotourism whether the popular customs and rural traditions are taking into account as well as the natural potential of this are” (R4). The fact that natural features of the environment overlap with local cultural heritage represents a certain opportunity to develop this settlement in terms of present sustainable progress in the local economic background. “It is a place where multiple forms of tourism could be developed from rural truism to cultural tourism, historical tourism, heritage tourism, tourism for recreation and so on…, the local potential of the commune seems to be fitted to different expectations of all those who cherished the rural habitats and their related specific cultures” (R5), stated another participant, encouraging further interventions into the promotion of this area at different levels, from regional to international. In this regard, another individual stated that “this place is as beautiful as others rural places from Transylvania or Moldavia but I think it has something unique, something special in terms of its landscape. The presence of this attractive fortress in the inner-core of the village generates a unique landscape from my side” (R6). It is, however, interesting how this place is perceived as a unique area with impressive cultural potential, but besides local culture, in the same vein, the local activities are acknowledged as possible touristic resources. “In my opinion, I think everybody agree it: the local activities of the local people is very attractive, I mean here the local agriculture in close connection with the local traditions, popular culture, the local customs and the folk art” (R7). This final statement, however, concludes that the village of Hărman disposes an interesting and attractive cultural capital which can be successfully capitalized into local sustainable economic development. It provides this place with a certain cultural identity, whose uniqueness remains a strong attribute, frequently considered in political strategies to invite tourism through the lens of local development initiatives.

4.4.3. The Perception of Foreign Tourists

The assertions assumed by foreign tourists are interesting, valuable, and triangulate our findings. “We knew that Transylvania is a wonderful European place, we heard a lot about it but did not imagine that it is such wonderful as it is, when you are physically in this place. All rural areas captured our hearts and it seems we are somewhere back in time. When we stepped into the fortress it was like moving back through time” (R1). This viewpoint argues for the local cultural authenticity of a place full of culture, popular landscape, and attractive cultural resources. Furthermore, the idea expands upon other rural traditional places in the Brașov region. “I found here a unique cultural landscape with a specific picturesque and it is quite interesting how this place was not altered in time. If I speak about the local nature and environmental features that cross the anthropic background, I have to say that this place is magic in all its rurality” (R2). This leads us to think that local potential on the whole represents a real strength and an opportunity to attract tourists and visitors and for future perspectives in local development through tourism and cultural heritage.

Considering the local architecture, a visitor pointed out: “not only the citadel and the inner ward of it unveils an interesting and attractive ancient architecture but also the houses built in the old German style, they are so beautiful; furthermore the households are so pleasant good-looking too see” (R3). Regarding popular culture, an interviewee stated: “I discovered here so good and tasted products. The bread made in people houses on the hearth is so tasted, so good as the dairy products are. I have my lunch in the fortress proximity and the food was great, however curiously in a modest traditional restaurant. Certainly I will get back to this place” (R4). The statement of this respondent goes beyond the landscape, architecture, and local monuments to local touristic, referring to the local facilities provided to visitors whose practices, goods, and food are also based on local cultural traditions and popular customs.

Taking into account the general cultural background, another interviewee considered that “absolutely I faced here with a place with a unique cultural identity: the sense of place, the place attachment, the unique atmosphere and the people’s representations of this place and its culture truly define a very beautiful village. I hope that it’s cultural capital, its material and immaterial culture to be preserved and to be fully capitalized further. It is a place so far and away by the present noisy places and yet so close connected to the urban life and culture” (R5). Consequently, the presented aspect portrays the close connection between rural and urban areas which could be considered for further preservation of and capitalization on the cultural rural resources in the face of contemporary avid urbanization. In this respect, rural cultural capital represents the main cultural trait of rural habitats which opens up multiple economic development perspectives through tourism and cultural tourism since this commune “has an important cultural heritage which have to be discovered by all those who cherished the local cultural authenticity of a place and the layers of history all overlapped in a single small rural settlement” (R6). Through all of the abovementioned asserted ideas, the cultural perception of foreign tourists, nevertheless, argues for the presence of an important cultural background and the cultural tourism potential in this area. The main cultural attributes unveiled by local residents, visitors, and tourists are summarized in Table 1, and these key aspects provide multiple opportunities and fertile practices and initiatives in local rural economic development through tourism and the use of the cultural resources of this place. These approaches have already captured the attention of various investors, stakeholders, and local actors for the sustainable development of the commune.

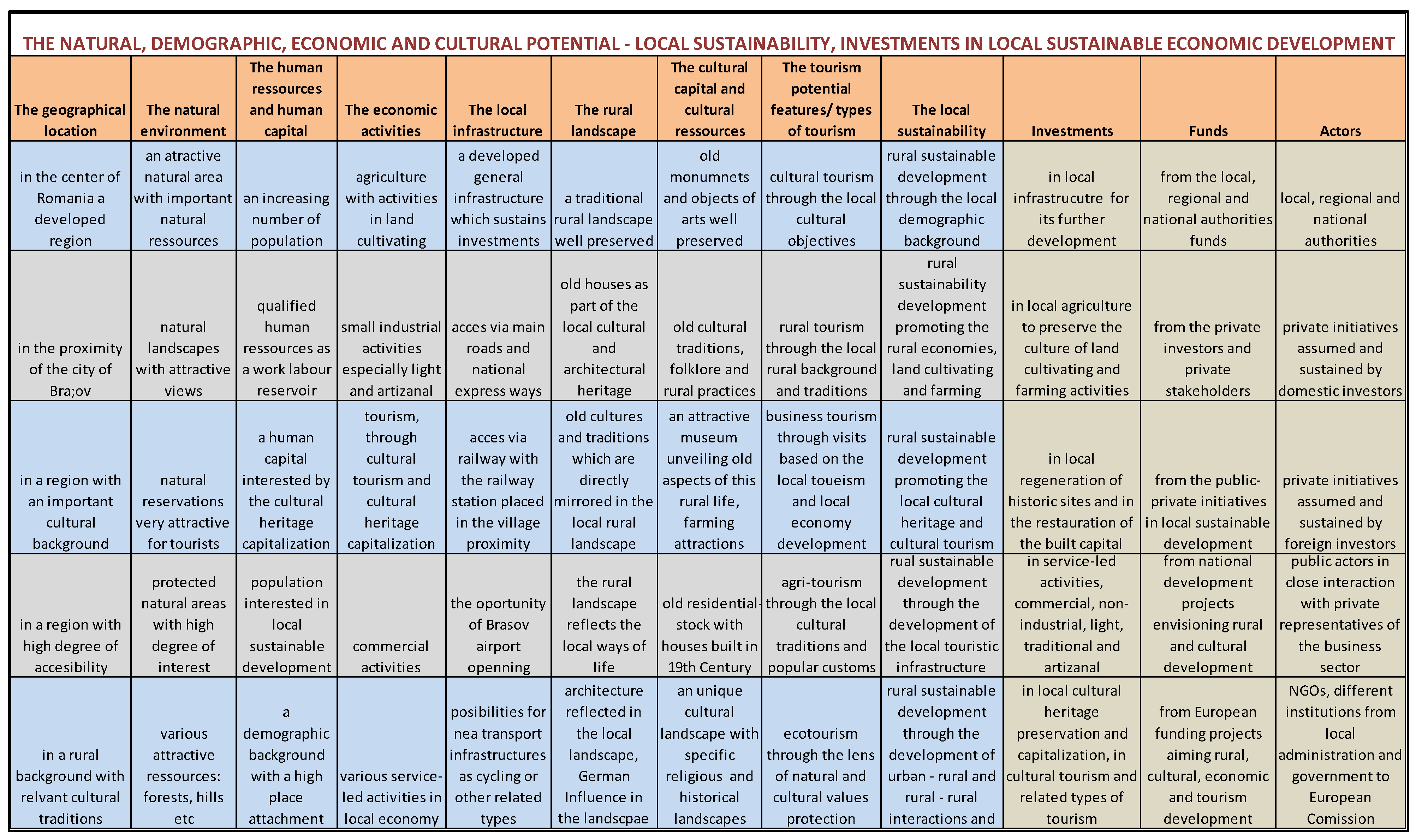

Table 1.

Synthesis of the main cultural attributes of Hărman commune and its local cultural heritage based on the local residents’ and tourists’ perceptions.

4.4.4. The Local Authorities Involvement and the Voice of Local Actors and Stakeholders

The Analysis of Policy Documents of Local Government: A Critical Review on the Strategy for Local Sustainable Rural Development

As has been mentioned, the local authorities developed a complex strategy to ensure local sustainable development in which multiple variables are considered as well as all the local potential, including tourism and the cultural resources of the village. This policy document, as a local sustainable development agenda, is closely connected to all the principles of sustainability as well as to the European background of local sustainable development. Based on its location, Hărman has multiple opportunities and advantages which could successfully maintain local economic development.

In this regard, tourism potential and cultural heritage are highlighted as major factors in the local economic development background. According to this policy document, tourism represents a vital aspect in local economic and sustainable development. The main advantage is based on the village’s geographical position in the immediate nearness to Brașov city, one of the most developed cities of Romania, based on tourism and tourism potential. The natural touristic objectives, cultural features, and cultural heritage lead to an increase in the tourism potential and in the cultural identity affirmation of the Hărman commune in regional and national contexts. At the same time, touristic infrastructure is represented by a hotel and five agri-touristic pensions, and these data argue that local touristic infrastructure is an emerging trend since these accommodation units appeared in 2015. The rise in the number of tourists has maintained a constant trend, except for the years within the COVID-19 pandemic period, with 2842 tourists in 2015 and 2063 in 2021. This is interesting and an argument for tourism development since the number of tourists represents about 30–40 per cent of the total number of residents in the village. As it was mentioned, between the local attractions, there are many cultural and touristic objectives: the fortified Evangelic Church, Ethnographic Museum, Romanian Heroes Monument, Lempeș Hill as Natura 2000 Sit component, and eutrophic marshes Hărman–Prejmer. To these, a cultural house and local library could be added, alongside with many cultural events, of which we mention the Harman Days Festival, Penașilor festival, and other traditional events organized in line with the main festivals during the year occasioning Easter, Christmas, and other religious festivals. Consequently, the main strengtheners of touristic and cultural background are, among others, the presence of many touristic and cultural attractions and objectives, the Hărman Fortress and the Evangelic Church being two of the most important historical monuments which contribute to local touristic attractiveness. Due to the important number of tourists annually visiting the commune and its touristic objectives, the existence of local touristic infrastructure (accommodation units, easy access to the commune, restaurants, pensions, a camping in the inner site of fortress, etc.) is necessary for local sustainable rural development [73].

As weaknesses which must be improved, in line with tourism development and local economic progress we also mention the reduced number of touristic routes, the weak promotion and capitalization of the local cultural background, touristic resources, and a low number of cultural events. All these must be considered for further improvement so that local development through tourism, cultural tourism, and the cultural heritage of this place can be improved. As opportunities, the protection of natural areas and of cultural monuments, the design of new touristic routes, support for various actors interested in investing and opening new business in this area, the creation of a local touristic information center, public–private partnerships in local tourism development, the promotion of cycle tourism, ecotourism, and agritourism, and the creation of belvedere points with attractive views on the village surroundings are all aspects which must be considered as things which have to be taken into account for further sustainable development. The threats to development noted in this analysis, regarding the degradation of some local attractions and the decreasing visibility of the commune in the absence of new cultural events, are identified at the local scale; they have to be foreseen and, of course, improved [73]. In the context of local economic development, agriculture, as a traditional cultural activity from previous times, through animal husbandry, livestock farming, and the local farming culture, has a great potential to contribute to touristic development through cultural tourism (based on food, agricultural events and traditions, farming customs), ecotourism, agritourism, and even business tourism. To sum up, these aspects have the power to inspire further initiatives and practices in line with the development of the local economy through tourism, local cultural heritage, and local touristic resources.

Initiatives in Local Economic Development

Based on the general background of the village, on the cultural heritage and the cultural touristic resources, and due to the local economy as well as to the location of Hărman being in immediate proximity of the city of Brașov and to the geographical position on the main national roads, the economic perspectives of this rural settlement are more than optimistic in ensuring sustainable rural development based on cultural tourism in close connection with other economic activities. In recent years, many stakeholders have been interested in developing various business, and the opening of Brașov airport will surely ensure this commune remains attractive. On the one hand, tourists and visitors, as vectors for local development, are present here once they are interested in visiting the city of Brașov and its neighborhoods, and, on the other, the local culture could be consumed from a touristic point of view by all tourists and visitors in transit. Finally, there are many and various contexts when visitors come here, especially to be in contact with the local rural culture and with economic and cultural practices. The last decades witnessed the appearance of many touristic pensions, restaurants, and the small light industry (especially for food or for processing different agricultural goods). All these are important factors in sustaining local tourism, particularly cultural tourism, or related forms connected to local culture, traditions, and customs. For instance, Hărman village hosts the headquarters of the Romanian Breeding Association Bălțata Românească Simmental Type (Figure 15 and Figure 16). It promotes the local and national agriculture and farming activities “the purpose of the association being to develop the general interest of local people in raising bulls for dairy and meat production, to carry out activities in the general interest of farmers, especially cows and dairy farmers, in the non-patrimonial interests of its members” [96]. It illustrates local involvement in traditional economic activities, with agriculture being represented by animal growth. This feature is a main cultural resource in the region. It is widely acknowledged that the Brașov area is an important traditional place for animal growth, reminiscent of old Romanian pastoral traditions. In this regard, “the Romanian Bălțata or Romanian Spotted Cattle is the most common breed of cattle in Romania. Red and white in color, it is resistant to poor nutrition and is used for milk and beef; it is particularly productive as a source of meat (…). As its name implies, the Romanian Bălțata was bred in Romania. It is descended from two breeds, Romanian Steppe Grey from Romania and Simmental imported from Switzerland, Austria, Germany, Czech Republic and Slovakia” [97,98]. These aspects are important backgrounds for the further development of rural tourism, agritourism, ecotourism, cultural tourism, and, of course, business tourism closely connected with the local traditional cultures of Romanian national agriculture. The latter could be used as a cultural resource for tourism and local economic development. If we consider Romanian food products [99], they could be also used as both cultural and touristic resources, providing a certain economic background for local and regional development. Figure 17 and Figure 18 are representative in this regard, showing a Romanian food brand which can be approached as a cultural feature in order to develop local tourism and a sustainable rural economy.

Figure 15.

The logo of the Romanian Breeding Association from Hărman Brașov—Romanian version Source: https://baltataromaneasca.ro/en/online, accessed on 10 February 2023.

Figure 16.

The logo of the Romanian Breeding Association from Hărman Brașov English version. Source: https://baltataromaneasca.ro/en/online, accessed on 10 February 2023.

Figure 17.

Advertising Romanian rural food products made and promoted by Romanian Breeding Association Bălțata Românească from Hărman Source: https://baltataromaneasca.ro/en/ online, accessed on 10 February 2023.

Figure 18.

Dairy products of Romanian Breeding Association Bălțata Românească from Hărman, Romania Source: https://baltataromaneasca.ro/en/online, accessed on 10 February 2023.

Accordingly, this brand of local economic culture and agriculture, through the contemporary trends of internationalization, could sustain local economic development, including tourism, from various rural perspectives (traditions, agriculture, rural ways of life, rural food and cultural products, the production of goods, and so on). Bălțata Românească is a Romanian brand with international recognition, and this feature represents an important base for further economic development in terms of rural sustainability and economic development in Hărman and, of course, in other Romanian regions. Considering that, this village represents an appropriate location for hosting further investments, this background successfully sustains local economic development in which tourism and cultural tourism capitalize all cultural heritage from these spaces from local cultures and historical heritage to local economic activities with an old tradition in this region as well as in Romania. The Brașov airport opening is an important and sustainable step in the local development of the commune, both for local economic development and for local tourism, creating a significant future opportunity for investors and tourists. Furthermore, as was acknowledged through conducting interviews which were unveiled above and the local development of Hărman in close connection with its spatial and functional relations with the city of Brașov, it is possible that this rural habitat will, in the future, turn into a distinct district of Brașov city, arguing therefore that sustainable development at a local scale is ensured by local spatial interactions between the territorial system of settlements from a certain geographical area.

4.4.5. Urban–Rural and Rural–Rural Interactions

The proximity of the Hărman commune to Brașov and the nearness of many other important rural settlements with impressive cultural backgrounds ensure a solid background for tourism development based on urban–rural and rural–rural interactions through an objective synergy between these localities. It is an important territorial system which must be approached in its entirety in the context of contemporary sustainable economic development [74]. The city of Brașov, as one of the most important Romanian touristic cities [74,100,101,102,103,104], represents a significant attraction for various tourists from Romania and abroad and, beyond its touristic potential, provides multiple opportunities for various visitors to its neighborhoods. They are rural habitats and certain places of attraction for the tourists consuming the local cultural heritage. In this regard, designing new rural touristic routes between all important rural settlements from this area starting from the city of Brașov could be a sustainable initiative for local touristic development and the local economy. In addition, rural–rural touristic interaction is another aspect which must be considered in the same way as the previous one. For instance, new and attractive touristic routes based on cultural heritage and the local cultural tourism of various rural settlements related to other initiatives and investments are important actions. A part of these is developed in the next section, envisioning an interchangeable approach bringing together different actions and initiatives from the side of local authorities, stakeholders, and investors through the lens of logical framework analysis.

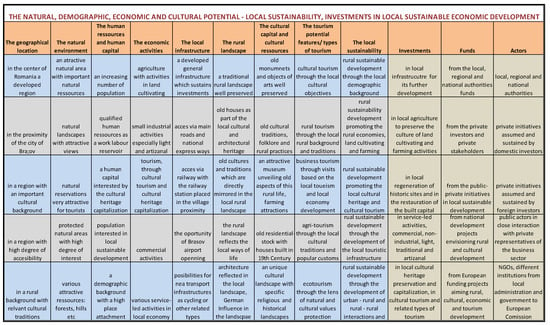

4.4.6. Logical Framework Analysis on the Local Sustainable Development through Cultural Heritage and Cultural Tourism of Hărman and Its Surrounding Area

As was mentioned, logical framework analysis (LFA) represents an important methodological design to improve further designed actions and initiatives for the local development of places, regions, and, frequently, areas connecting different localities which a frame complex and specific territorial systems. Considering that our case cannot be separated from its surroundings in terms of economic sustainable development and local cultural heritage capitalized on through the lens of cultural tourism, the LFA method is an appropriate tool for foreseen future activities and it is based on three important steps: the identification of problems, the solution derivation, and the formation of a planning strategy for implementation [77,105,106]. The main results of the analysis and their related actions are briefly summarized in Figure 19, sketching the most important problems, objectives, activities, and work strategies in order to provide a fertile and objective frame for further actions in local development through cultural heritage and cultural tourism in Hărman community. Logical framework analysis (LFA) represents a relevant tool based on SWOT analysis, and in the present approach, the LFA method is based on the SWOT analysis made by the local authorities and is included in the local development strategy [73] as a part of policy document investigation. In this respect, the LFA approach was used to triangulate the main findings and to design an appropriate instrument which could inspire the next initiatives and practices in local economic sustainable development.

Figure 19.

The main results of LFA analysis from the local potential of development to specific actions and initiatives.

The main findings identified and summarized through the lens of the LFA approach provide a critical and objective vision for the next approaches, initiatives, and practices which could be considered for further interventions in order to ensure the local sustainable economic development of this commune, including tourism and, especially, cultural tourism through cultural heritage capitalization. As the above general graphical synthesis unveils, the selected case study encourages all social, economic, and cultural data and backgrounds for ensuring local sustainable development.

4.4.7. A Summary Discussion