Foraging Practices and Sustainable Management of Wild Food Resources in Europe: A Systematic Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

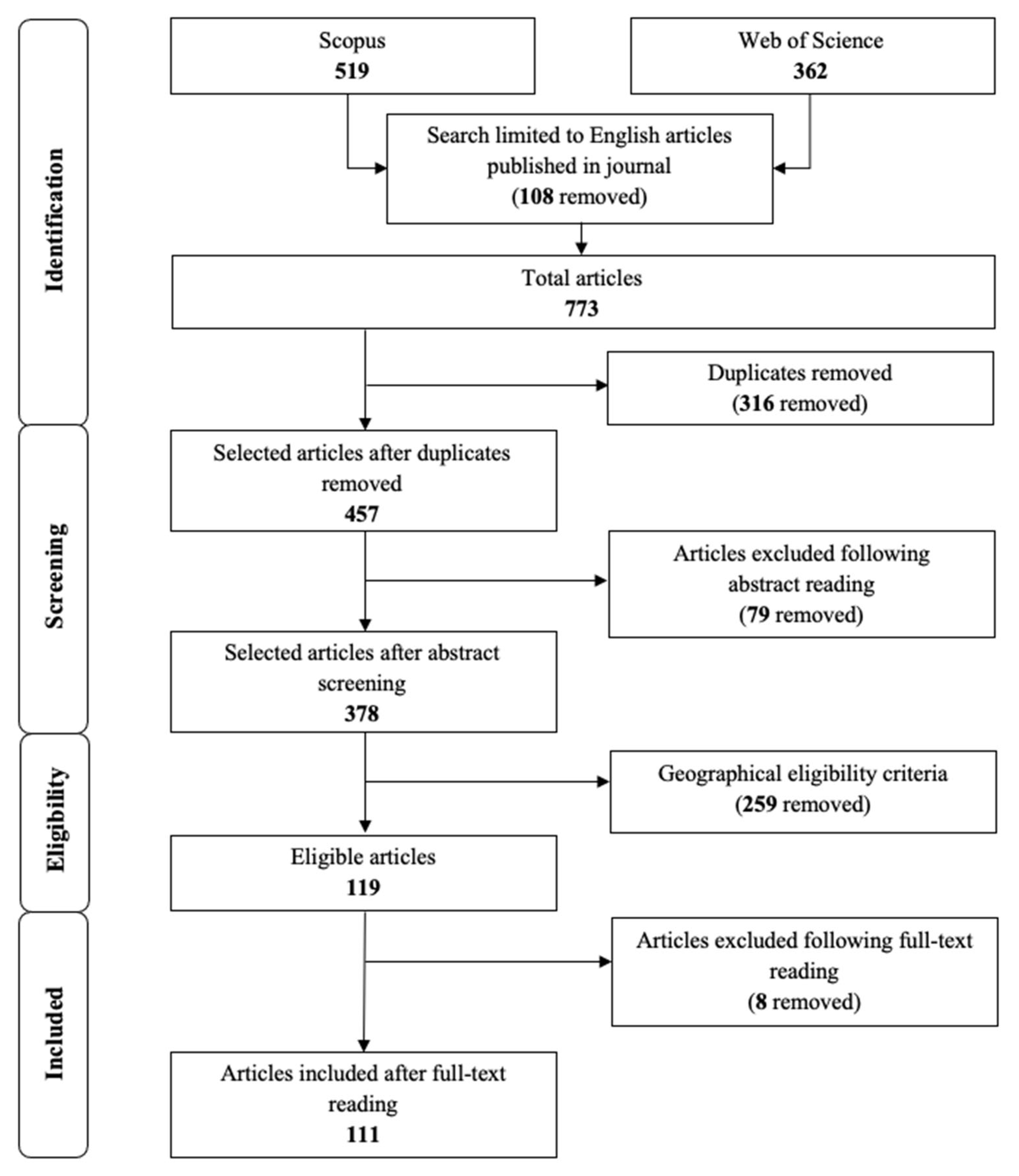

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Choosing a Review Methodology

2.2. Research Questions Definition

- Research Question 1 (RQ1): Which drivers of the abandonment of foraging practices in Europe emerge from the literature?

- Research Question 2 (RQ2): What motivations explain the preservation and enhancement of foraging practices in Europe?

- Research Question 3 (RQ3): What are the economic, social, and environmental benefits and risks associated with the management of foraging practices?

2.3. Papers’ Selection Procedure

3. Results

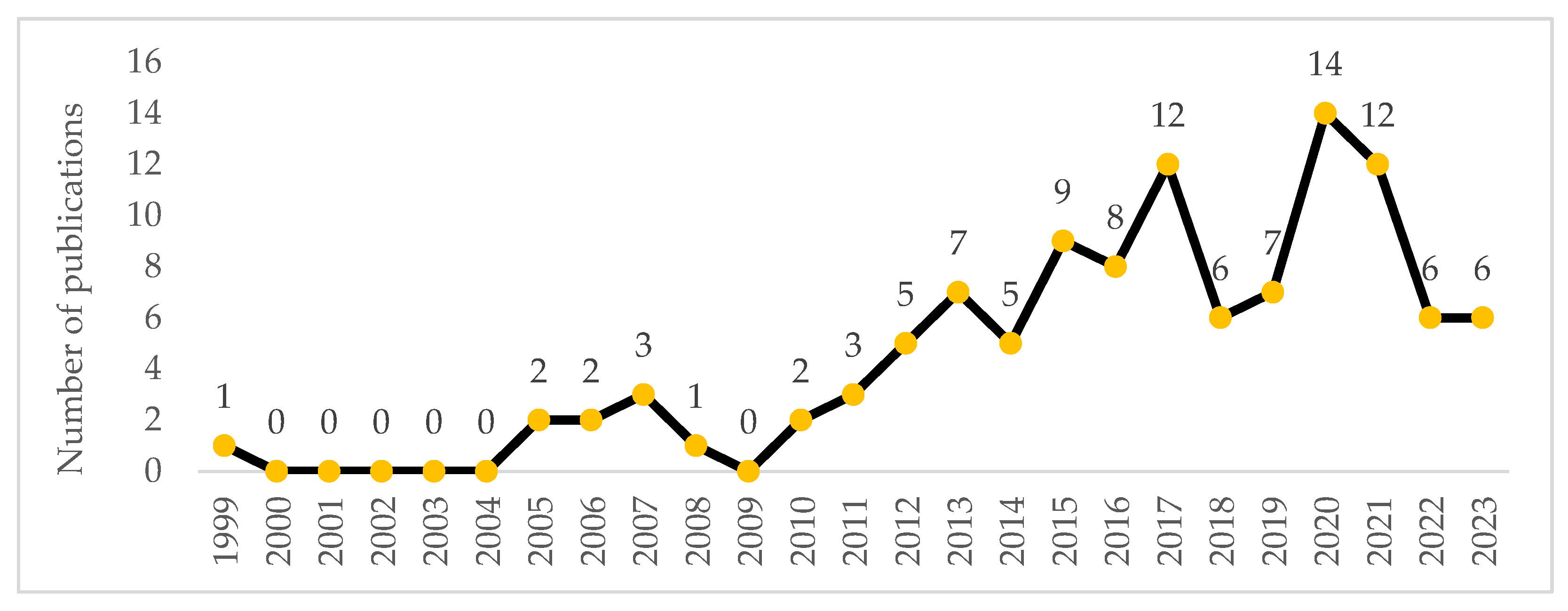

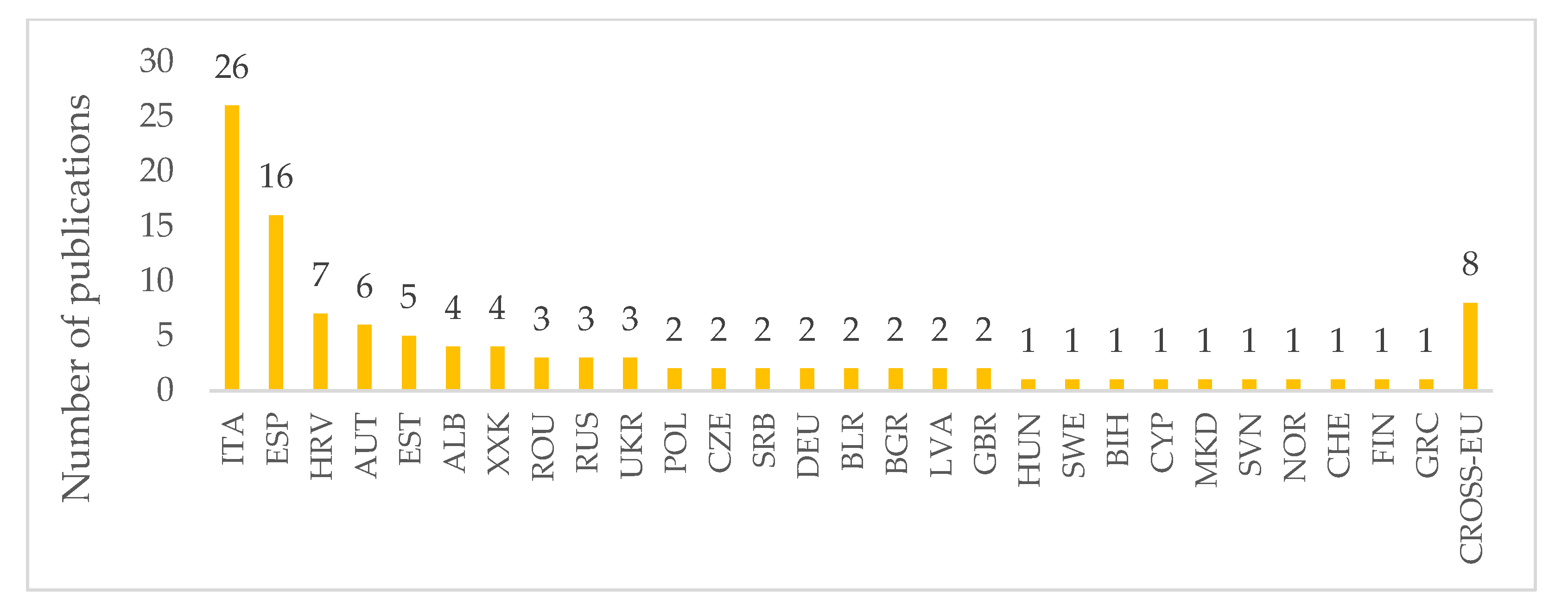

3.1. Descriptive Statistics on Selected Papers

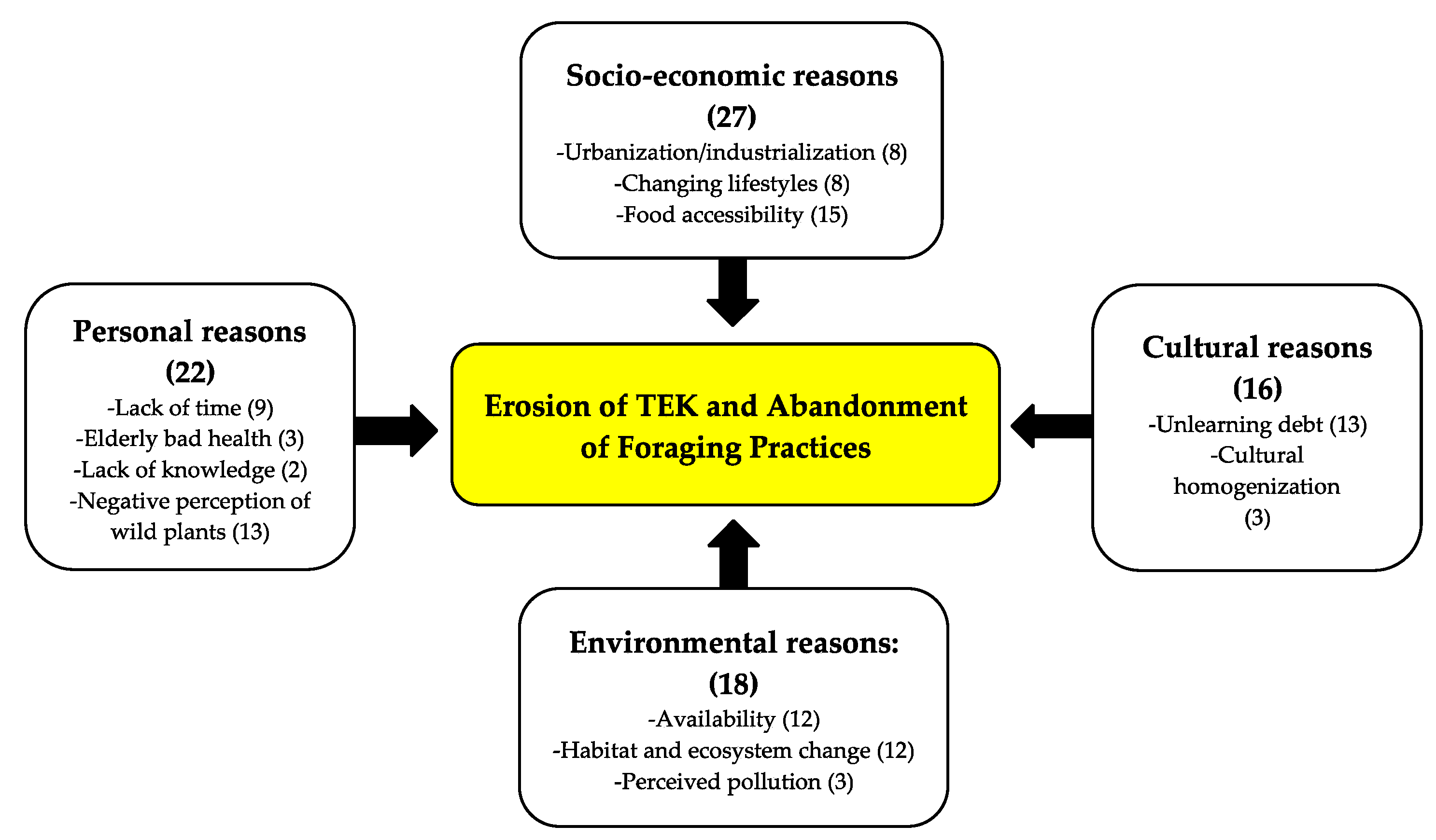

3.2. Erosion of TEK and Abandonment of Foraging Practices

3.2.1. Socio-Economic Reasons

3.2.2. Cultural Reasons

3.2.3. Personal Reasons

3.2.4. Environmental Reasons

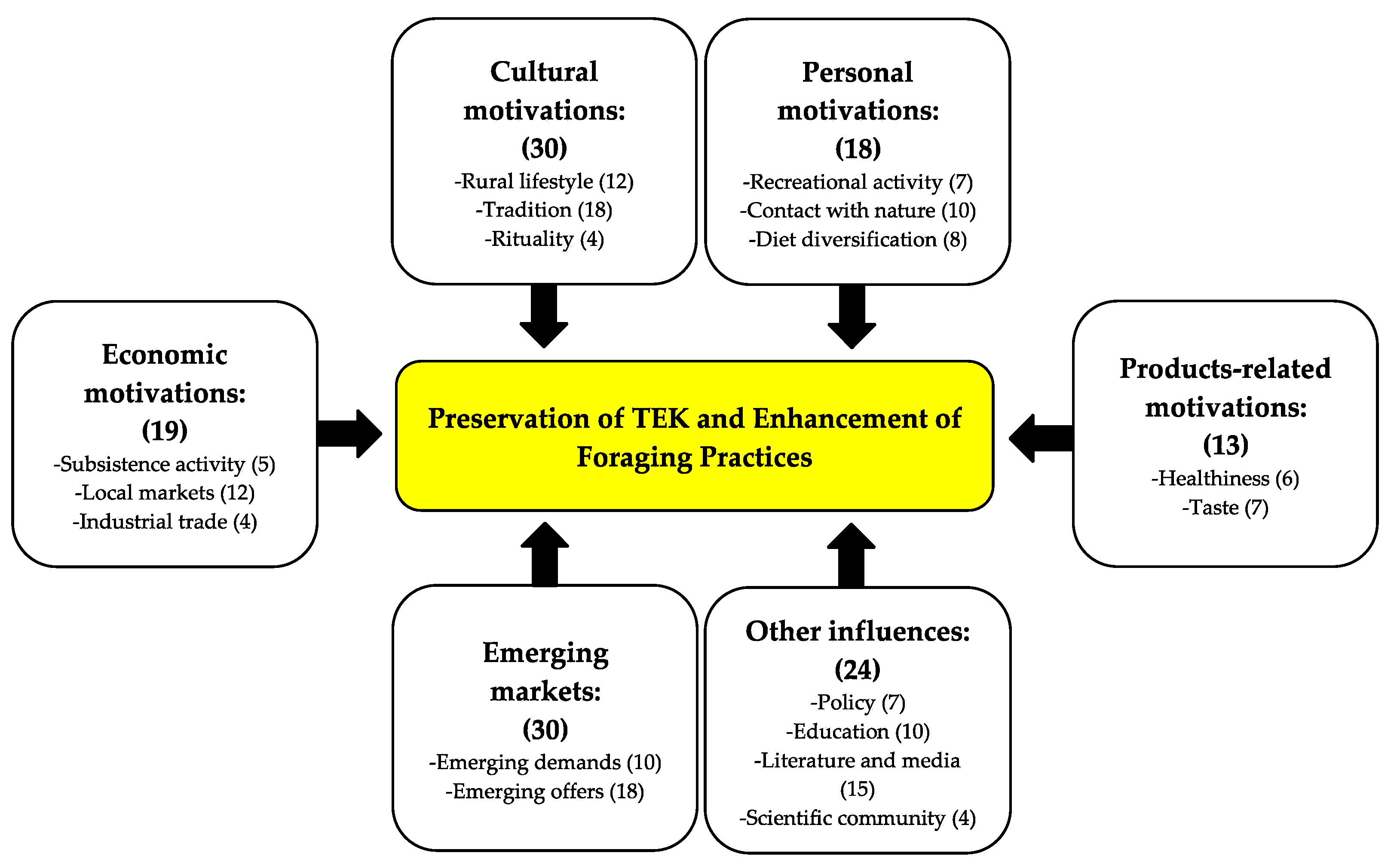

3.3. Preservation of TEK and Enhancement of Foraging Practices

3.3.1. Cultural Motivations

3.3.2. Personal Motivations

3.3.3. Product-Related Motivations

3.3.4. Economic Motivations

3.3.5. Emerging Markets

3.3.6. Other Influences

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Reference | Country | Area of Study | Territory | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbet et al. (2014) [93] | CHE | Valais Valley | Rural | Local residents |

| Aceituno-Mata (2021) [107] | ESP | Sierra Norte de Madrid | Rural | Local residents |

| Acosta-Naranjo et al. (2021) [78] | ESP | Madrid/Extremadura/Andalusia | Rural | Local residents |

| Aziz et al. (2022) [144] | EST/UKR | Estonia/SW Ukraine | Rural | Local residents |

| Babai et al. (2020) [114] | SVN | Goričko region | Rural | Local residents |

| Bardone (2013) [59] | EST | Whole country | Rural/urban | Literature |

| Belichenko et al. (2021) [132] | RUS | Pechorsky District (Pskov Oblast) | Rural | Local residents |

| Bellia and Pieroni (2015) [117] | ITA | Piedmont region | Rural | Local residents |

| Benítez et al. (2017) [109] | ESP | Granada Province | Rural | Local residents |

| Bexultanova et al. (2022) [68] | RUS | Whole country | Rural | Literature |

| Biscotti et al. (2015) [11] | ITA | Gargano National Park (Apulia) | Rural/Food Markets | Local residents |

| Biscotti et al. (2018) [96] | ITA | Apulia region | Rural/urban | Local residents |

| Brandner and Schunko (2022) [62] | AUT | Vienna | Urban | Urban population |

| Cucinotta and Pieroni (2018) [105] | ITA | Aeolian Islands (Sicily) | Rural | Local residents |

| Della et al. (2006) [72] | CYP | Paphos/Larnaca | Rural | Local residents |

| Dénes (2017) [35] | HUN | Pecs | Food Markets | Local salesmen |

| Di Tizio et al. (2012) [97] | ITA | Montemitrio (Molise) | Rural | Local residents |

| Dolina and Łuczaj (2014) [84] | HRV | Dubrovnik coast | Rural | Local residents |

| Federman (2011) [83] | ITA | Salento (Apulia) | Rural | Local residents |

| Fischer et al. (2019) [53] | DEU | Berlin | Urban | Field study |

| Fontefrancesco and Pieroni (2020) [137] | ITA | Sangone Valley (Piedmont) | Rural | Local residents |

| Ghirardini et al. (2007) [65] | ITA | Whole country | Rural | Local residents |

| González et al. (2011) [89] | ESP | Arribes del Duero National Park | Rural | Local residents |

| Gras (2021) [127] | ESP | Catalan area | Rural | Local residents |

| Hadjichambis et al. (2008) [66] | CYP/GRC/ITA/ ESP/ALB | Mediterranean area | Rural | Local residents |

| Ivanova (2023) [67] | BGR | Whole country | Rural | Local residents |

| Jug-Dujakovic and Łuczaj (2016) [51] | HRV | Adriatic islands | Rural | Literature/Expert interview |

| Kalle and Sõukand (2013) [52] | EST | Whole country | Rural | Local experts |

| Kalle and Sõukand (2016) [102] | EST | Saaremaa | Rural | Local residents |

| Kalle et al. (2020a) [85] | EST | Võrumaa/Setomaa | Rural | General |

| Kalle et al. (2020b) [147] | FIN/RUS/EST/LTU LVA/BLR/UKR | Karelia/Pskov/Voromaa/Dagda/Salcininkai/hrodna/cherenivsti | Rural | Local residents |

| Kolosova et al. (2020) [88] | RUS | Karelia | Rural | Local residents |

| Landor-Yamagata et al. (2018) [63] | DEU | Berlin | Urban | Urban population |

| Lee and Garikipati (2011) [143] | GBR | Whole country | Rural | Literature |

| Lentini and Venza (2007) [149] | ITA | Sicily region | Rural | Local residents |

| Łuczaj (2010) [58] | POL | Whole country | Rural | Literature |

| Łuczaj and Dolina (2015) [123] | BIH | Herzegovina-Neretva Canton | Rural | Local residents |

| Łuczaj and Kujawaska (2012) [50] | POL | Whole country | Rural/urban | Botanist |

| Łuczaj et al. (2013a) [47] | HRV | Dalmatia | Food Markets | Local salesmen |

| Łuczaj et al. (2013b) [91] | HRV | Lake Vrana Nature Park | Rural | Local residents |

| Łuczaj et al. (2013c) [61] | BLR | Whole country | Rural | Literature/local residents |

| Łuczaj et al. (2015) [122] | ROU | Maramureş region | Rural | Local residents |

| Łuczaj et al. (2019) [136] | HRV | Adriatic islands | Rural | Local residents |

| Łuczaj et al. (2021) [48] | GBR | Whole country | Rural | Foragers |

| Lukovic et al. (2021) [121] | SRB | Golija-Studenica Biosphere Reserv | Rural | Local residents/sellers |

| Luković et al. (2023) [45] | SRB | Whole country | Rural | Tourist |

| Maruca et al. (2019) [94] | ITA | Reventino Massif (Calabria) | Rural | Local residents |

| Mattalia et al. (2013) [128] | ITA | Western Alps (Piedmont) | Rural | Local residents |

| Mattalia et al. (2020a) [104] | ITA | Cosenza Province (Calabria) | Rural | Local residents |

| Mattalia et al. (2020b) [112] | ITA | Natisone Valley (Friuli-Venezia-Giulia) | Rural | Local residents |

| Mattalia et al. (2020c) [145] | UKR/ROU | Bukovina | Rural | Local residents |

| Mattalia et al. (2020d) [125] | ITA | Calabria region | Rural | Local residents |

| Mattalia et al. (2020e) [129] | ITA | Barbagia (Sardinia) | Rural | Local residents |

| Mattalia et al. (2021) [69] | ITA | Abruzzo and Molise region | Rural | Local residents |

| Mattalia et al. (2023) [74] | FIN | Karelia | Rural | Local residents |

| Menendez-Baceta et al. (2012) [80] | ESP | Basque Country | Rural | Local residents |

| Menendez-Baceta et al. (2017) [77] | ESP | Arratia Valley (Basque country) | Rural | Local residents |

| Molina et al. (2012) [55] | ESP | Madrid Province | Rural | Field study |

| Molina et al. (2014) [54] | ESP | Madrid Province | Rural | Field study |

| Motti et al. (2020) [106] | ITA | Campania region | Rural | Local residents |

| Mullalija et al. (2021) [70] | XXK | Anadrini region | Rural/Urban | Local residents |

| Mustafa et al. (2012) [75] | XXK | Gollak region | Rural | Local residents |

| Mustafa et al. (2015) [138] | XXK | Sharr Mountains | Rural | Local residents |

| Nebel et al. (2006) [95] | ITA | Graecanic area (Calabria) | Rural | Local residents |

| Nedelcheva (2013) [60] | BGR | Whole country | Rural | Literature |

| Nedelcheva et al. (2017) [116] | MKD | Plačkovica Mountain | Rural | Local residents |

| Pardo-De-Santayana et al. (2005) [135] | ESP | Campoo (Cantabria) | Rural | Local residents |

| Pardo-De-Santayana et al. (2007) [141] | ESP | Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula | Rural | Local residents |

| Pascual and Herrero (2017) [154] | ESP | Nord Palencia | Rural | Local residents |

| Pasta et al. (2020) [56] | ITA | Sicily region | Rural | Literature |

| Paura et al. (2021) [150] | ITA | Whole country | Rural | Literature |

| Pawera et al. (2019) [119] | CZE | White Carpathians | Rural | Local residents |

| Pieroni (1999) [73] | ITA | Garfagnana (Tuscany) | Rural | Local residents |

| Pieroni (2017) [99] | ALB | South-Eastern Albania | Rural | Local residents |

| Pieroni and Sõukand (2017a) [86] | UKR | Transcarpathia | Rural | Local residents |

| Pieroni and Sõukand (2017b) [115] | ALB | North-East Albania | Rural | Local residents |

| Pieroni and Sõukand (2018) [108] | UKR | Polesia | Rural | Local residents |

| Pieroni et al. (2014) [124] | ALB | Peshkopia | Rural | Local residents |

| Pieroni et al. (2015a) [98] | ALB | Rrajcë and Mokra | Rural | Local residents |

| Pieroni et al. (2015b) [139] | ROU | Dobruja | Rural | Local residents |

| Pieroni et al. (2017) [82] | XXK | Kosovar Gora | Rural | Local residents |

| Pieroni et al. (2022) [130] | GRC | Central Crete | Urban/Rural | Local residents |

| Prakofjewa (2023) [111] | POL/BLR/LTU | Podlaise/Vilnius/Hrodna | Rural | Local residents |

| Prūse et al. (2021a) [110] | LVA | Dagda | Rural | Local residents |

| Prūse et al. (2021b) [152] | LVA | Latgale | Rural | Local residents |

| Quave and Saitta (2016) [140] | ITA | Pantelleria Island | Rural | Local residents |

| Reyes-García et al. (2015) [87] | ESP | Whole country | Rural | Local residents |

| Rigat et al. (2016) [133] | ESP | Ripollès district | Rural | Local residents |

| Sansanelli et al. (2017) [101] | ITA | Middle Agry Valley (Basilicata) | Rural | Local residents |

| Sansanelli and Tassoni (2014) [100] | ITA | Emilia-Romagna region | Rural | Local residents |

| Savo et al. (2019) [120] | ITA | Monti Picentini Regional Park | Rural | Local residents |

| Schunko and Brandner (2022) [64] | AUT | Vienna | Urban | Urban population |

| Schunko and Vogl (2010) [42] | AUT | Styria | Rural | Local farmers |

| Schunko and Vogl (2018) [43] | AUT | Whole country | Rural | Local farmers |

| Schunko and Vogl (2020) [44] | AUT | Whole country | Food Markets | Organic consumers |

| Schunko et al. (2019) [34] | ITA | South Tyrol | Rural | Local farmers |

| Schunko et al. (2021) [142] | AUT | Vienna | Rural | Stakeholders |

| Serrasolses et al. (2016) [79] | ESP | Catalan Pyrenees/Balearic Islands | Rural | Local residents |

| Sisak et al. (2016) [134] | CZE | Whole country | Whole country | General |

| Sõukand (2016) [90] | EST | Saaremaa | Rural | Local residents |

| Sõukand and Pieroni (2016) [146] | UKR/ROU | Bukovina | Rural | Local residents |

| Sõukand et al. (2017) [81] | BLR | Liubań | Rural | Local residents |

| Stryamets et al. (2015) [92] | UKR/RUS/SWE | Rozrochya/Kortkeros/Småland | Rural | Local residents |

| Sulaiman et al. (2023) [131] | UKR | Western Oblasts | Rural | Local residents |

| Svanberg and Berggren (2018) [57] | DNK/FIN/EST SWE/ISL/NOR | Whole country | Rural | Literature |

| Svanberg and Lindh (2019) [126] | SWE | Uppsala | Rural/urban | General |

| Tardío et al. (2005) [71] | ESP | Madrid Province | Rural | Local residents |

| Teixidor-Tineu et al. (2023) [49] | NOR | Whole country | Whole country | Foragers |

| Varga et al. (2019) [76] | HRV | Dalmatia | Rural | Local residents |

| Vári et al. (2020) [118] | ROU | Transylvania | Rural | Local residents |

| Vitasović-Kosić et al. (2022) [71] | HRV | Central Lika | Rural | Local residents |

References

- Nakashima, D.J.; Galloway McLean, K.; Thulstrup, H.D.; Ramos Castillo, A.; Rubis, J.T. Weathering Uncertainty: Traditional Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation; UNESCO and Darwin, UNU: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mekonen, S. Roles of Traditional Ecological Knowledge for Biodiversity Conservation. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2017, 7, 21–27. [Google Scholar]

- Khoury, C.K.; Bjorkman, A.D.; Dempewolf, H.; Ramirez-Villegas, J.; Guarino, L.; Jarvis, A.; Rieseberg, L.H.; Struik, P.C. Increasing Homogeneity in Global Food Supplies and the Implications for Food Security. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 4001–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- FAO. The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture. 2019. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/CA3129EN/CA3129EN.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Zocchi, D.M.; Cevasco, R.; Dossche, R.; Abidullah, S.; Pieroni, A. Crumbotti and Rose Petals in a Ghost Mountain Valley: Foraging, Landscape, and Their Transformations in the Upper Borbera Valley, NW Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2022, 18, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowak-Olejnik, A.; Mocior, E. Provisioning Ecosystem Services of Wild Plants Collected from Seminatural Habitats: A Basis for Sustainable Livelihood and Multifunctional Landscape Conservation. Mt. Res. Dev. 2022, 42, R11–R19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, P.H. Saving Plants, Saving Ourselves. Plants People Planet 2019, 1, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharrock, S.; Jackson, P.W. Plant Conservation and the Sustainable Development Goals: A Policy Paper Prepared for the Global Partnership for Plant Conservation. Ann. Mo. Bot. Gard. 2017, 102, 290–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EFI. Non-Wood Forest Products for People, Nature and the Green Economy. Recommendations for Policy Priorities in Europe. A White Paper Based on Lessons Learned from around the Mediterranean. 2021. Available online: https://efi.int/sites/default/files/files/publication-bank/2021/EFI_K2A_05_2021.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- UNESCO. Mediterranean Diet. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/mediterranean-diet-00884 (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Biscotti, N.; Pieroni, A.; Luczaj, L. The Hidden Mediterranean Diet: Wild Vegetables Traditionally Gathered and Consumed in the Gargano Area, Apulia, SE Italy. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2015, 84, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlpFoodWay. Available online: https://www.alpfoodway.eu/paper/english (accessed on 8 May 2023).

- Bonadonna, A.; Peira, G.; Varese, E. The European optional quality term “Mountain Product”: Hypothetical application in the production chain of a traditional dairy product. Qual. Access Success 2015, 16, 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- Giachino, C.; Truant, E.; Bonadonna, A. Mountain tourism and motivation: Millennial students’ seasonal preferences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2461–2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duglio, S.; Bonadonna, A.; Letey, M. The Contribution of Local Food Products in Fostering Tourism for Marginal Mountain Areas: An Exploratory Study on Northwestern Italian Alps. Mt. Res. Dev. 2022, 42, R1–R10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadonna, A.; Duglio, S.; Bollani, L.; Peira, G. Mountain Food Products: A Cluster Analysis Based on Young Consumers’ Perceptions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramo, R.; Bonadonna, A.; Duglio, S.; Peira, G.; Vesce, E. Local food heritage in a mountain tourism destination: Evidence from the Alagna Walser Green Paradise project. Br. Food J. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Mattalia, G.; Prakofjewa, J.; Kalle, R.; Prūse, B.; Marozzi, M.; Stryamets, N.; Kuznetsova, N.; Belichenko, O.; Aziz, M.A.; Pieroni, A.; et al. Centralization can jeopardize local wild plant-based food security. NJAS Impact Agric. Life Sci. 2023, 95, 2191798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sõukand, R.; Stryamets, N.; Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Pieroni, A. The Importance of Tolerating Interstices: Babushka Markets in Ukraine and Eastern Europe and Their Role in Maintaining Local Food Knowledge and Diversity. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tardío, J.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M.; Morales, R. Ethnobotanical Review of Wild Edible Plants in Spain. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2006, 152, 27–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benítez, G.; Molero-Mesa, J.; González-Tejero, M.R. Wild Edible Plants of Andalusia: Traditional Uses and Potential of Eating Wild in a Highly Diverse Region. Plants 2023, 12, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldi, A.; Bruschi, P.; Campeggi, S.; Egea, T.; Rivera, D.; Obón, C.; Lenzi, A. The Renaissance of Wild Food Plants: Insights from Tuscany (Italy). Foods 2022, 11, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M.; Savo, V. Wild Food Plants Used in Traditional Vegetable Mixtures in Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 185, 202–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Szymański, W.M. Wild Vascular Plants Gathered for Consumption in the Polish Countryside: A Review. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Svanberg, I. The Use of Wild Plants as Food in Pre-Industrial Sweden. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Svanberg, I.; Egisson, S. Edible Wild Plant Use in the Faroe Islands and Iceland. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rivera, D.; Obón, C.; Heinrich, M.; Inocencio, C.; Verde, A.; Fajardo, J. Gathered Mediterranean Food Plants-Ethnobotanical Investigations and Historical Development. Forum Nutr. 2006, 59, 18–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonti, M.; Nebel, S.; Rivera, D.; Heinrich, M. Wild Gathered Food Plants in the European Mediterranean: A Comparative Analysis. Econ. Bot. 2006, 60, 130–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Pieroni, A.; Tardío, J.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M.; Sõukand, R.; Svanberg, I.; Kalle, R. Wild Food Plant Use in 21st Century Europe: The Disappearance of Old Traditions and the Search for New Cuisines Involving Wild Edibles. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunko, C.; Li, X.; Klappoth, B.; Lesi, F.; Porcher, V.; Porcuna-Ferrer, A.; Reyes-García, V. Local Communities’ Perceptions of Wild Edible Plant and Mushroom Change: A Systematic Review. Glob. Food Secur. 2022, 32, 100601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zocchi, D.M.; Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. Recognising, Safeguarding and Promoting Food Heritage: Challenges and Prospects for the Future of Sustainable Food Systems. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grivins, M. Are All Foragers the Same? Towards a Classification of Foragers. Sociol. Rural. 2021, 61, 518–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunko, C.; Grasser, S.; Vogl, C.R. Explaining the Resurgent Popularity of the Wild: Motivations for Wild Plant Gathering in the Biosphere Reserve Grosses Walsertal, Austria. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schunko, C.; Lechthaler, S.; Vogl, C.R. Conceptualising the Factors That Influence the Commercialisation of Non-Timber Forest Products: The Case of Wild Plant Gathering by Organic Herb Farmers in South Tyrol (Italy). Sustainability 2019, 11, 2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pieroni, A.; Giusti, M.E. Alpine Ethnobotany in Italy: Traditional Knowledge of Gastronomic and Medicinal Plants among the Occitans of the Upper Varaita Valley, Piedmont. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; Shekelle, P.; Stewart, L.A.; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Syst. Rev. 2015, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cleyle, S.; Booth, A. Clear and Present Questions: Formulating Questions for Evidence Based Practice. Libr. Hi Tech 2006, 24, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cantillo, J.; Martín, J.C.; Román, C. Discrete Choice Experiments in the Analysis of Consumers’ Preferences for Finfish Products: A Systematic Literature Review. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 84, 103952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiletto, A.; Trestini, S. Factors behind Consumers’ Choices for Healthy Fruits: A Review of Pomegranate and Its Food Derivatives. Agric. Food Econ. 2021, 9, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnham, J. Scopus Database: A Review. Biomed. Digit. Libr. 2006, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- UN. Standard Country or Area Codes for Statistical Use (M49). Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/ (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Schunko, C.; Vogl, C.R. Organic Farmers Use of Wild Food Plants and Fungi in a Hilly Area in Styria (Austria). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010, 6, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schunko, C.; Vogl, C.R. Is the Commercialization of Wild Plants by Organic Producers in Austria Neglected or Irrelevant? Sustainability 2018, 10, 3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schunko, C.; Vogl, C.R. Factors Determining Organic Consumers’ Knowledge and Practices with Respect to Wild Plant Foods: A Countrywide Study in Austria. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 82, 103868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luković, M.; Kostić, M.; Dajić Stevanović, Z. Food Tourism Challenges in the Pandemic Period: Getting Back to Traditional and Natural-Based Products. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dénes, A. Wild Plants for Sale in the Markets of Pécs Then and Now (Baranya, Hungary). Acta Ethnogr. Hung. 2017, 62, 339–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; ZovkoKončić, M.; Miličević, T.; Dolina, K.; Pandža, M. Wild Vegetable Mixes Sold in the Markets of Dalmatia (Southern Croatia). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Wilde, M.; Townsend, L. The Ethnobiology of Contemporary British Foragers: Foods They Teach, Their Sources of Inspiration and Impact. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixidor-Toneu, I.; Giraud, N.J.; Karlsen, P.; Annes, A.; Kool, A. A Transdisciplinary Approach to Define and Assess Wild Food Plant Sustainable Foraging in Norway. Plants People Planet 2023, 5, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, L.J.; Kujawska, M. Botanists and Their Childhood Memories: An Underutilized Expert Source in Ethnobotanical Research. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2012, 168, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jug-Dujakovic, M.; Luczaj, L. The contribution of Josip Bakic’s research to the study of wild edible plants of the Adriatic coast: A military project with ethnobiological and anthopological implications. Slov. Nardopis-Slovak Ethnol. 2016, 64, 158–168. [Google Scholar]

- Kalle, R.; Sõukand, R. Wild Plants Eaten in Childhood: A Retrospective of Estonia in the 1970s-1990s. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 2013, 172, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, L.K.; Brinkmeyer, D.; Karle, S.J.; Cremer, K.; Huttner, E.; Seebauer, M.; Nowikow, U.; Schütze, B.; Voigt, P.; Völker, S.; et al. Biodiverse Edible Schools: Linking Healthy Food, School Gardens and Local Urban Biodiversity. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 40, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.; Tardío, J.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Morales, R.; Reyes-García, V.; Pardo-De-Santayana, M. Weeds and Food Diversity: Natural Yield Assessment and Future Alternatives for Traditionally Consumed Wild Vegetables. J. Ethnobiol. 2014, 34, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, M.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; García, E.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Morales, R.; Tardío, J. Exploring the Potential of Wild Food Resources in the Mediterranean Region: Natural Yield and Gathering Pressure of the Wild Asparagus (Asparagus acutifolius L.) [Potencial de Las Plantas Silvestres Comestibles En La Región Mediterránea: Producción y Presión Recolectora Del Espárrago Triguero (Asparagus acutifolius L.)]. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2012, 10, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pasta, S.; La Rosa, A.; Garfì, G.; Marcenò, C.; Gristina, A.S.; Carimi, F.; Guarino, R. An Updated Checklist of the Sicilian Native Edible Plants: Preserving the Traditional Ecological Knowledge of Century-Old Agro-Pastoral Landscapes. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanberg, I.; Berggren, Å. Bumblebee Honey in the Nordic Countries. Ethnobiol. Lett. 2018, 9, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Łuczaj, Ł. Changes in the Utilization of Wild Green Vegetables in Poland since the 19th Century: A Comparison of Four Ethnobotanical Surveys. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 128, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardone, E. Strawberry Fields Forever? Foraging for the Changing Meaning of Wild Berries in Estonian Food Culture. Ethnol. Eur. 2013, 43, 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Nedelcheva, A. An Ethnobotanical Study of Wild Edible Plants in Bulgaria. EurAsian J. BioSciences 2013, 7, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, L.; Köhler, P.; Piroznikow, E.; Graniszewska, M.; Pieroni, A.; Gervasi, T. Wild Edible Plants of Belarus: From Rostafiński’s Questionnaire of 1883 to the Present. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brandner, A.; Schunko, C. Urban Wild Food Foraging Locations: Understanding Selection Criteria to Inform Green Space Planning and Management. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 73, 127596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landor-Yamagata, J.L.; Kowarik, I.; Fischer, L.K. Urban Foraging in Berlin: People, Plants and Practices within the Metropolitan Green Infrastructure. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schunko, C.; Brandner, A. Urban Nature at the Fingertips: Investigating Wild Food Foraging to Enable Nature Interactions of Urban Dwellers. Ambio 2022, 51, 1168–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghirardini, M.P.; Carli, M.; del Vecchio, N.; Rovati, A.; Cova, O.; Valigi, F.; Agnetti, G.; Macconi, M.; Adamo, D.; Traina, M.; et al. The Importance of a Taste. A Comparative Study on Wild Food Plant Consumption in Twenty-One Local Communities in Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hadjichambis, A.C.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D.; Della, A.; Elena Giusti, M.; De Pasquale, C.; Lenzarini, C.; Censorii, E.; Reyes Gonzales-Tejero, M.; Patricia Sanchez-Rojas, C.; Ramiro-Gutierrez, J.; et al. Wild and Semi-Domesticated Food Plant Consumption in Seven Circum-Mediterranean Areas. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2008, 59, 383–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, T.; Marchev, A.; Chervenkov, M.; Bosseva, Y.; Georgiev, M.; Kozuharova, E.; Dimitrova, D. Catching the Green—Diversity of Ruderal Spring Plants Traditionally Consumed in Bulgaria and Their Potential Benefit for Human Health. Diversity 2023, 15, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bexultanova, G.; Prakofjewa, J.; Sartori, M.; Kalle, R.; Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R. Promotion of Wild Food Plant Use Diversity in the Soviet Union, 1922–1991. Plants 2022, 11, 2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattalia, G.; Sõukand, R.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. “We Became Rich and We Lost Everything”: Ethnobotany of Remote Mountain Villages of Abruzzo and Molise, Central Italy. Hum. Ecol. 2021, 49, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullalija, B.; Mustafa, B.; Hajdari, A.; Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. Ethnobotany of Rural and Urban Albanians and Serbs in the Anadrini Region, Kosovo. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2021, 68, 1825–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasović-Kosić, I.; Hodak, A.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Marić, M.; Juračak, J. Traditional Ethnobotanical Knowledge of the Central Lika Region (Continental Croatia)—First Record of Edible Use of Fungus Taphrina Pruni. Plants 2022, 11, 3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Della, A.; Paraskeva-Hadjichambi, D.; Hadjichambis, A.C. An Ethnobotanical Survey of Wild Edible Plants of Paphos and Larnaca Countryside of Cyprus. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006, 2, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pieroni, A. Gathered Wild Food Plants in the Upper Valley of the Serchio River (Garfagnana), Central Italy. Econ. Bot. 1999, 53, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattalia, G.; Svanberg, I.; Ståhlberg, S.; Kuznetsova, N.; Prūse, B.; Kolosova, V.; Aziz, M.A.; Kalle, R.; Sõukand, R. Outdoor Activities Foster Local Plant Knowledge in Karelia, NE Europe. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, B.; Hajdari, A.; Pajazita, Q.; Syla, B.; Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. An Ethnobotanical Survey of the Gollak Region, Kosovo. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2012, 59, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, F.; Šolić, I.; Dujaković, M.J.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Grdiša, M. The First Contribution to the Ethnobotany of Inland Dalmatia: Medicinal and Wild Food Plants of the Knin Area, Croatia. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2019, 88, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez-Baceta, G.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Tardío, J.; Reyes-García, V. Trends in Wild Food Plants Uses in Gorbeialdea (Basque Country). Appetite 2017, 112, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-Naranjo, R.; Rodríguez-Franco, R.; Guzmán-Troncoso, A.J.; Pardo-De-santayana, M.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Gómez-Melara, J.; Domínguez-Gregorio, P.; Díaz-Reviriego, I.; González- Nateras, J.; Reyes-García, V. Gender Differences in Knowledge, Use, and Collection of Wild Edible Plants in Three Spanish Areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrasolses, G.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Carrió, E.; D’Ambrosio, U.; Garnatje, T.; Parada, M.; Vallès, J.; Reyes-García, V. A Matter of Taste: Local Explanations for the Consumption of Wild Food Plants in the Catalan Pyrenees and the Balearic Islands. Econ. Bot. 2016, 70, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Menendez-Baceta, G.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Tardío, J.; Reyes-García, V.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Wild Edible Plants Traditionally Gathered in Gorbeialdea (Biscay, Basque Country). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2012, 59, 1329–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sõukand, R.; Hrynevich, Y.; Vasilyeva, I.; Prakofjewa, J.; Vnukovich, Y.; Paciupa, J.; Hlushko, A.; Knureva, Y.; Litvinava, Y.; Vyskvarka, S.; et al. Multi-Functionality of the Few: Current and Past Uses of Wild Plants for Food and Healing in Liubań Region, Belarus. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R.; Quave, C.L.; Hajdari, A.; Mustafa, B. Traditional Food Uses of Wild Plants among the Gorani of South Kosovo. Appetite 2017, 108, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federman, A. Between Plenty and Poverty Foraging in the Salento with Patience Gray. Gastron. J. Food Cult. 2011, 11, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolina, K.; Łuczaj, Ł. Wild Food Plants Used on the Dubrovnik Coast (South-Eastern Croatia). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2014, 83, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kalle, R.; Sõukand, R.; Pieroni, A. Devil Is in the Details: Use of Wild Food Plants in Historical Võromaa and Setomaa, Present-Day Estonia. Foods 2020, 9, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R. Are Borders More Important than Geographical Distance? The Wild Food Ethnobotany of the Boykos and Its Overlap with That of the Bukovinian Hutsuls in Western Ukraine. J. Ethnobiol. 2017, 37, 326–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-García, V.; Menendez-Baceta, G.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Acosta-Naranjo, R.; Calvet-Mir, L.; Domínguez, P.; Garnatje, T.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Molina-Bustamante, M.; Molina, M.; et al. From Famine Foods to Delicatessen: Interpreting Trends in the Use of Wild Edible Plants through Cultural Ecosystem Services. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 120, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kolosova, V.; Belichenko, O.; Rodionova, A.; Melnikov, D.; Sõukand, R. Foraging in Boreal Forest: Wild Food Plants of the Republic of Karelia, NW Russia. Foods 2020, 9, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, J.A.; García-Barriuso, M.; Amich, F. The Consumption of Wild and Semi-Domesticated Edible Plants in the Arribes Del Duero (Salamanca-Zamora, Spain): An Analysis of Traditional Knowledge. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2011, 58, 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sõukand, R. Perceived Reasons for Changes in the Use of Wild Food Plants in Saaremaa, Estonia. Appetite 2016, 107, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Fressel, N.; Perković, S. Wild Food Plants Used in the Villages of the Lake Vrana Nature Park (Northern Dalmatia, Croatia). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2013, 82, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stryamets, N.; Elbakidze, M.; Ceuterick, M.; Angelstam, P.; Axelsson, R. From Economic Survival to Recreation: Contemporary Uses of Wild Food and Medicine in Rural Sweden, Ukraine and NW Russia. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abbet, C.; Mayor, R.; Roguet, D.; Spichiger, R.; Hamburger, M.; Potterat, O. Ethnobotanical Survey on Wild Alpine Food Plants in Lower and Central Valais (Switzerland). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 151, 624–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruca, G.; Spampinato, G.; Turiano, D.; Laghetti, G.; Musarella, C.M. Ethnobotanical Notes about Medicinal and Useful Plants of the Reventino Massif Tradition (Calabria Region, Southern Italy). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2019, 66, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nebel, S.; Pieroni, A.; Heinrich, M. Ta Chòrta: Wild Edible Greens Used in the Graecanic Area in Calabria, Southern Italy. Appetite 2006, 47, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscotti, N.; Bonsanto, D.; Del Viscio, G. The Traditional Food Use of Wild Vegetables in Apulia (Italy) in the Light of Italian Ethnobotanical Literature. Ital. Bot. 2018, 5, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Tizio, A.; Łuczaj, T.J.; Quave, C.L.; Redžić, S.; Pieroni, A. Traditional Food and Herbal Uses of Wild Plants in the Ancient South-Slavic Diaspora of Mundimitar/Montemitro (Southern Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pieroni, A.; Ibraliu, A.; Abbasi, A.M.; Papajani-Toska, V. An Ethnobotanical Study among Albanians and Aromanians Living in the Rraicë and Mokra Areas of Eastern Albania. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2015, 62, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A. Traditional Uses of Wild Food Plants, Medicinal Plants, and Domestic Remedies in Albanian, Aromanian and Macedonian Villages in South-Eastern Albania. J. Herb. Med. 2017, 9, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sansanelli, S.; Tassoni, A. Wild Food Plants Traditionally Consumed in the Area of Bologna (Emilia Romagna Region, Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sansanelli, S.; Ferri, M.; Salinitro, M.; Tassoni, A. Ethnobotanical Survey of Wild Food Plants Traditionally Collected and Consumed in the Middle Agri Valley (Basilicata Region, Southern Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalle, R.; Sõukand, R. Current and Remembered Past Uses of Wild Food Plants in Saaremaa, Estonia: Changes in the Context of Unlearning Debt. Econ. Bot. 2016, 70, 235–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D.; May, R.M.; Lehman, C.L.; Nowak, M.A. Habitat Destruction and the Extinction Debt. Nature 1994, 371, 65–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattalia, G.; Sõukand, R.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. Blended Divergences: Local Food and Medicinal Plant Uses among Arbëreshë, Occitans, and Autochthonous Calabrians Living in Calabria, Southern Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2020, 154, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucinotta, F.; Pieroni, A. “If You Want to Get Married, You Have to Collect Virdura”: The Vanishing Custom of Gathering and Cooking Wild Food Plants on Vulcano, Aeolian Islands, Sicily. Food Cult. Soc. 2018, 21, 539–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Bonanomi, G.; Lanzotti, V.; Sacchi, R. The Contribution of Wild Edible Plants to the Mediterranean Diet: An Ethnobotanical Case Study Along the Coast of Campania (Southern Italy). Econ. Bot. 2020, 74, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aceituno-Mata, L.; Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. The Persistence of Flavor: Past and Present Use of Wild Food Plants in Sierra Norte de Madrid, Spain. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 4, 610238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R. Forest as Stronghold of Local Ecological Practice: Currently Used Wild Food Plants in Polesia, Northern Ukraine. Econ. Bot. 2018, 72, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benítez, G.; Molero-Mesa, J.; González-Tejero, M.R. Gathering an Edible Wild Plant: Food or Medicine? A Case Study on Wild Edibles and Functional Foods in Granada, Spain. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2017, 86, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prūse, B.; Buffa, G.; Kalle, R.; Simanova, A.; Mežaka, I.; Sõukand, R. We Need to Appreciate Common Synanthropic Plants before They Become Rare: Case Study in Latgale (Latvia). Ethnobiol. Conserv. 2021, 10, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakofjewa, J.; Sartori, M.; Šarka, P.; Kalle, R.; Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R. Boundaries Are Blurred: Wild Food Plant Knowledge Circulation across the Polish-Lithuanian-Belarusian Borderland. Biology 2023, 12, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattalia, G.; Sõukand, R.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. Dissymmetry at the Border: Wild Food and Medicinal Ethnobotany of Slovenes and Friulians in NE Italy. Econ. Bot. 2020, 74, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardío, J.; Pascual, H.; Morales, R. Wild Food Plants Traditionally Used in the Province of Madrid, Central Spain. Econ. Bot. 2005, 59, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babai, D.; Szépligeti, M.; Tóth, A.; Ulicsni, V. Traditional Ecological Knowledge and the Cultural Significance of Plants in Hungarian Communities in Slovenia. Acta Ethnogr. Hung. 2020, 65, 481–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R. The Disappearing Wild Food and Medicinal Plant Knowledge in a Few Mountain Villages of North-Eastern Albania. J. Appl. Bot. Food Qual. 2017, 90, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelcheva, A.; Pieroni, A.; Dogan, Y. Folk Food and Medicinal Botanical Knowledge among the Last Remaining Yörüks of the Balkans. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2017, 86, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bellia, G.; Pieroni, A. Isolated, but Transnational: The Glocal Nature of Waldensian Ethnobotany, Western Alps, NW Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vári, á.; Arany, I.; Kalóczkai, á.; Kelemen, K.; Papp, J.; Czúcz, B. Berries, Greens, and Medicinal Herbs-Mapping and Assessing Wild Plants as an Ecosystem Service in Transylvania (Romania). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pawera, L.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Pieroni, A.; Polesny, Z. Traditional Plant Knowledge in the White Carpathians: Ethnobotany of Wild Food Plants and Crop Wild Relatives in the Czech Republic. Hum. Ecol. 2017, 45, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savo, V.; Salomone, F.; Bartoli, F.; Caneva, G. When the Local Cuisine Still Incorporates Wild Food Plants: The Unknown Traditions of the Monti Picentini Regional Park (Southern Italy). Econ. Bot. 2019, 73, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukovic, M.; Pantovic, D.; Curcic, M. Wild edible plants in gourmet offer of ecotourism destinations: Case from biosphere “Golija-Studenica”. Ekon. Poljopr. Econ. Agric. 2021, 68, 1061–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luczaj, L.; Stawarczyk, K.; Kosiek, T.; Pietras, M.; Kujawa, A. Wild Food Plants and Fungi Used by Ukrainians in the Western Part of the Maramureş Region in Romania. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2015, 84, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Dolina, K. A Hundred Years of Change in Wild Vegetable Use in Southern Herzegovina. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 166, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Nedelcheva, A.; Hajdari, A.; Mustafa, B.; Scaltriti, B.; Cianfaglione, K.; Quave, C.L. Local Knowledge on Plants and Domestic Remedies in the Mountain Villages of Peshkopia (Eastern Albania). J. Mt. Sci. 2014, 11, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattalia, G.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. The Virtues of Being Peripheral, Recreational, and Transnational: Local Wild Food and Medicinal Plant Knowledge in Selected Remote Municipalities of Calabria, Southern Italy. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2020, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanberg, I.; Lindh, H. Mushroom Hunting and Consumption in Twenty-First Century Post- Industrial Sweden. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gras, A.; Garnatje, T.; Marín, J.; Parada, M.; Sala, E.; Talavera, M.; Vallès, J. The Power of Wild Plants in Feeding Humanity: A Meta-Analytic Ethnobotanical Approach in the Catalan Linguistic Area. Foods 2021, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattalia, G.; Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. Traditional Uses of Wild Food and Medicinal Plants among Brigasc, Kyé, and Provençal Communities on the Western Italian Alps. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2013, 60, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattalia, G.; Sõukand, R.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. Wild Food Thistle Gathering and Pastoralism: An Inextricable Link in the Biocultural Landscape of Barbagia, Central Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 5105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A.; Sulaiman, N.; Sõukand, R. Chorta (Wild Greens) in Central Crete: The Bio- Cultural Heritage of a Hidden and Resilient Ingredient of the Mediterranean Diet. Biology 2022, 11, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulaiman, N.; Aziz, M.A.; Stryamets, N.; Mattalia, G.; Zocchi, D.M.; Ahmed, H.M.; Manduzai, A.K.; Shah, A.A.; Faiz, A.; Sõukand, R.; et al. The Importance of Becoming Tamed: Wild Food Plants as Possible Novel Crops in Selected Food-Insecure Regions. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belichenko, O.; Kolosova, V.; Melnikov, D.; Kalle, R.; Sõukand, R. Language of Administration as a Border: Wild Food Plants Used by Setos and Russians in Pechorsky District of Pskov Oblast, NW Russia. Foods 2021, 10, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigat, M.; Gras, A.; D’Ambrosio, U.; Garnatje, T.; Parada, M.; Vallès, J. Wild Food Plants and Minor Crops in the Ripollès District (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula): Potentialities for Developing a Local Production, Consumption and Exchange Program. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sisak, L.; Riedl, M.; Dudik, R. Non-Market Non-Timber Forest Products in the Czech Republic-Their Socio-Economic Effects and Trends in Forest Land Use. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 390–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-De-Santayana, M.; Tardío, J.; Morales, R. The Gathering and Consumption of Wild Edible Plants in the Campoo (Cantabria, Spain). Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 56, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Jug-Dujaković, M.; Dolina, K.; Jeričević, M.; Vitasović-Kosić, I. The Ethnobotany and Biogeography of Wild Vegetables in the Adriatic Islands. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontefrancesco, M.F.; Pieroni, A. Renegotiating Situativity: Transformations of Local Herbal Knowledge in a Western Alpine Valley during the Past 40 Years. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, B.; Hajdari, A.; Pieroni, A.; Pulaj, B.; Koro, X.; Quave, C.L. A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Folk Plant Uses among Albanians, Bosniaks, Gorani and Turks Living in South Kosovo. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pieroni, A.; Nedelcheva, A.; Dogan, Y. Local Knowledge of Medicinal Plants and Wild Food Plants among Tatars and Romanians in Dobruja (South-East Romania). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2015, 62, 605–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quave, C.L.; Saitta, A. Forty-Five Years Later: The Shifting Dynamic of Traditional Ecological Knowledge on Pantelleria Island, Italy. Econ. Bot. 2016, 70, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Tardío, J.; Blanco, E.; Carvalho, A.M.; Lastra, J.J.; San Miguel, E.; Morales, R. Traditional Knowledge of Wild Edible Plants Used in the Northwest of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal): A Comparative Study. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schunko, C.; Wild, A.-S.; Brandner, A. Exploring and Limiting the Ecological Impacts of Urban Wild Food Foraging in Vienna, Austria. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 62, 127164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Garikipati, S. Negotiating the Non-Negotiable: British Foraging Law in Theory and Practice. J. Environ. Law 2011, 23, 415–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, M.A.; Mattalia, G.; Sulaiman, N.; Ali Shah, A.; Polesny, Z.; Kalle, R.; Sõukand, R.; Pieroni, A. The nexus between traditional foraging and its sustainability: A qualitative assessment among a few selected Eurasian case studies. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattalia, G.; Stryamets, N.; Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R. Knowledge transmission patterns at the border: Ethnobotany of Hutsuls living in the Carpathian Mountains of Bukovina (SW Ukraine and NE Romania). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sõukand, R.; Pieroni, A. The Importance of a Border: Medical, Veterinary, and Wild Food Ethnobotany of the Hutsuls Living on the Romanian and Ukrainian Sides of Bukovina. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 185, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalle, R.; Belichenko, O.; Kuznetsova, N.; Kolosova, V.; Prakofjewa, J.; Stryamets, N.; Mattalia, G.; Šarka, P.; Simanova, A.; Prūse, B.; et al. Gaining Momentum: Popularization of Epilobium Angustifolium as Food and Recreational Tea on the Eastern Edge of Europe. Appetite 2020, 150, 104638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakofjewa, J.; Kalle, R.; Belichenko, O.; Kolosova, V.; Sõukand, R. Re-Written Narrative: Transformation of the Image of Ivan-Chaj in Eastern Europe. Heliyon 2020, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentini, F.; Venza, F. Wild Food Plants of Popular Use in Sicily. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Paura, B.; Di Marzio, P.; Salerno, G.; Brugiapaglia, E.; Bufano, A. Design a Database of Italian Vascular Alimurgic Flora (Alimurgita): Preliminary Results. Plants 2021, 10, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dee, L.E.; De Lara, M.; Costello, C.; Gaines, S.D. To What Extent Can Ecosystem Services Motivate Protecting Biodiversity? Ecol. Lett. 2017, 20, 935–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prūse, B.; Simanova, A.; Mežaka, I.; Kalle, R.; Prakofjewa, J.; Holsta, I.; Laizāne, S.; Sõukand, R. Active Wild Food Practices among Culturally Diverse Groups in the 21st Century across Latgale, Latvia. Biology 2021, 10, 551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comaroff, J.L.; Comaroff, J. Ethnicity, Inc.; Chicago University Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pascual, J.C.; Herrero, B. Wild Food Plants Gathered in the Upper Pisuerga River Basin, Palencia, Spain. Bot. Lett. 2017, 164, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, I.; Montes, C.; Martín-López, B.; González, J.A.; García-Llorente, M.; Alcorlo, P.; Mora, M.R.G. Incorporating the Social-Ecological Approach in Protected Areas in the Anthropocene. BioScience 2014, 64, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, R.S.; Alkemade, R.; Braat, L.; Hein, L.; Willemen, L. Challenges in Integrating the Concept of Ecosystem Services and Values in Landscape Planning, Management and Decision Making. Ecol. Complex. 2010, 7, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SPICE Element | Search Terms Assigned | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Setting—where? | No term assigned | The geographical context was retrieved during abstract reading |

| Population—for whom? | No term assigned | No term assigned |

| Intervention—what? Comparison—compared with what? | “Wild edible plants” “Wild food” No term assigned | To limit the information on wild plants used for human consumption No term assigned |

| Evaluation—with what result? | “Foraging” “Ethnobotan*” | The outcomes of interest are the foraging activity and ethnobotanical studies |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Before abstract screening: -English language -Peer-reviewed journal articles | Before abstract screening: -Other languages -Reviews, book chapters, proceeding articles |

| During abstract screening: -Focus on local knowledge and foraging practices of wild edible plants -European context | During abstract screening: -Focus on other aspects of wild edible plants -Different geographical context |

| Journals | N | Authors | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine | 20 | Pieroni A. | 37 |

| Economic Botany | 9 | Sõukand R. | 26 |

| Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution | 8 | Łuczaj L. | 16 |

| Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae | 7 | Kalle R. | 11 |

| Sustainability | 6 | Mattalia G. | 11 |

| Appetite | 5 | Pardo-De-santayana M. | 8 |

| Journal of Ethnopharmacology | 4 | Tardío J. | 8 |

| Foods | 4 | Quave C.L. | 8 |

| Biology | 3 | Aceituno-Mata L. | 7 |

| Plants | 3 | Schunko C. | 7 |

| Potential Benefits of Foraging Practices | Potential Risks of Foraging Practices |

|---|---|

| Environmental: Sustainable land management and conservation of biodiversity | Environmental: Unsustainable land management practices and overexploitation or underexploitation of local resources |

| Social: Social cohesion and cultural enhancement of local communities | Social: Commodification of local knowledge and wild plants |

| Economic: Widespread economic development of local communities | Economic: Economic development not distributed to the local communities |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mina, G.; Scariot, V.; Peira, G.; Lombardi, G. Foraging Practices and Sustainable Management of Wild Food Resources in Europe: A Systematic Review. Land 2023, 12, 1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071299

Mina G, Scariot V, Peira G, Lombardi G. Foraging Practices and Sustainable Management of Wild Food Resources in Europe: A Systematic Review. Land. 2023; 12(7):1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071299

Chicago/Turabian StyleMina, Giorgio, Valentina Scariot, Giovanni Peira, and Giampiero Lombardi. 2023. "Foraging Practices and Sustainable Management of Wild Food Resources in Europe: A Systematic Review" Land 12, no. 7: 1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071299

APA StyleMina, G., Scariot, V., Peira, G., & Lombardi, G. (2023). Foraging Practices and Sustainable Management of Wild Food Resources in Europe: A Systematic Review. Land, 12(7), 1299. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071299