Common-Property Resource Exploitation: A Real Options Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- in areas where land productivity was subject to rapid improvements whose benefits could be easily taken possession of, a gradual privatization of common property occurred, as, for example, in the common-property lands of the northern plain of Italy;

- in areas where productivity was low (e.g., in forest land, marginal grazing land, etc.) and socio-economic development was good, common property was maintained and gave rise to institutions with primarily social and environmental objectives, such as the Communities of the Eastern Alps;

- in areas where productivity was low and socio-economic development lagged, commons were preserved for economic purposes, but did not promote institutions strong enough to face the challenges of an evolving role they would be called upon to play, as in the case of common lands in marginal areas.

2. Common Goods, Common-Property and Common-Pool Resources

3. Relevant Literature

4. The Model

- (a)

- by paying a permit fee, the user can acquire the right to use the resource at any time for a specific time;

- (b)

- the exercise of the right to use the resource involves a sunk cost;

- (c)

- the renunciation of the right to use the resource generates a sunk cost;

- (d)

- the decision to exercise the right to exploit, interrupt, or re-start exploiting the resource can be taken at any point in time.

4.1. The Value of the Right to Use a Common-Property Resource

4.2. The Right Holders’ Optimal Use Strategy

4.3. Analysis of Entry and Exit Thresholds

- (1)

- the sunk entry and exit costs, i.e., k and l;

- (2)

- the operating cost c;

- (3)

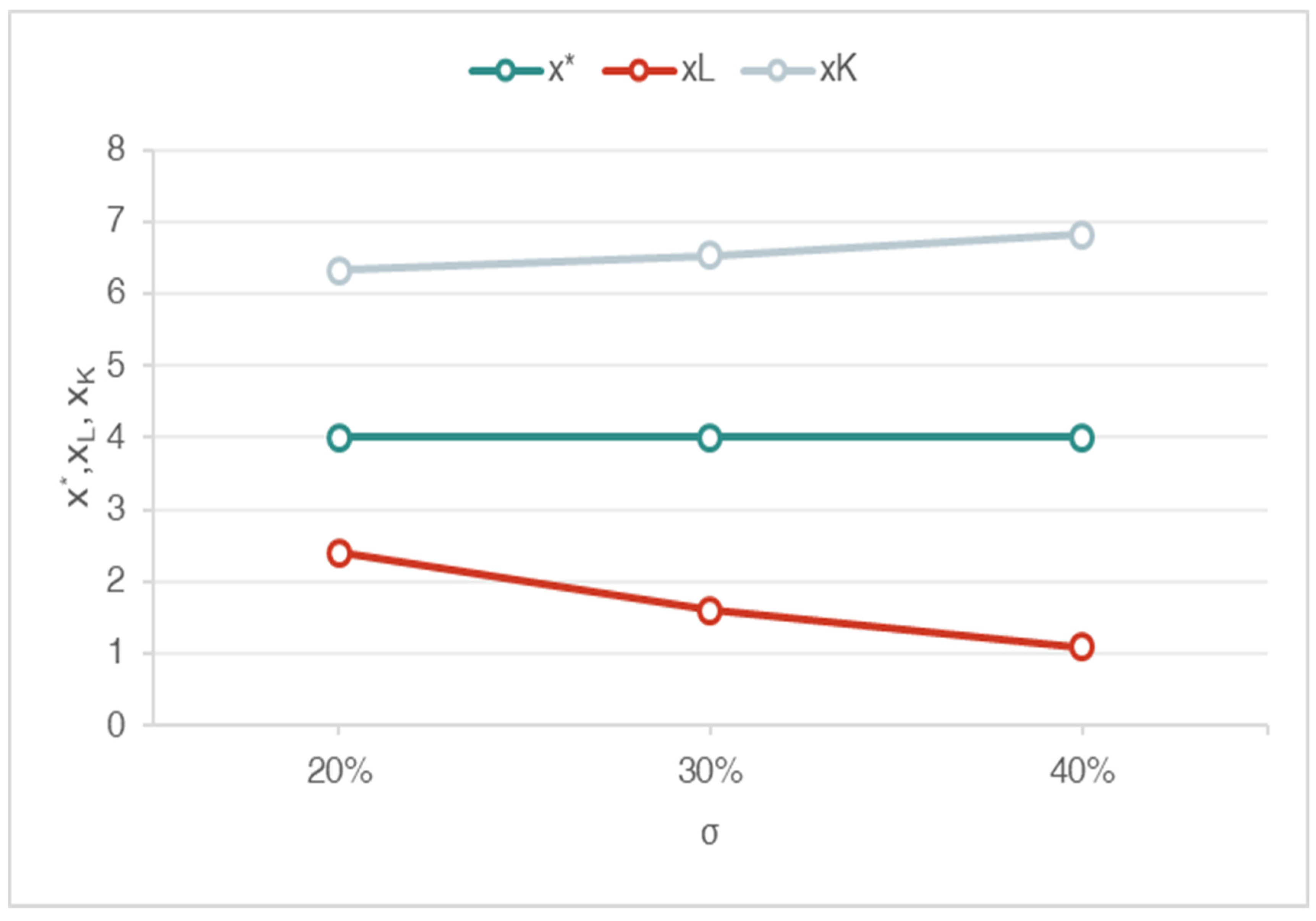

- the uncertainty σ;

- (4)

- the number of rivals n.

5. A Numerical Example: Mushroom Picking

5.1. Scenarios

5.2. Calibration

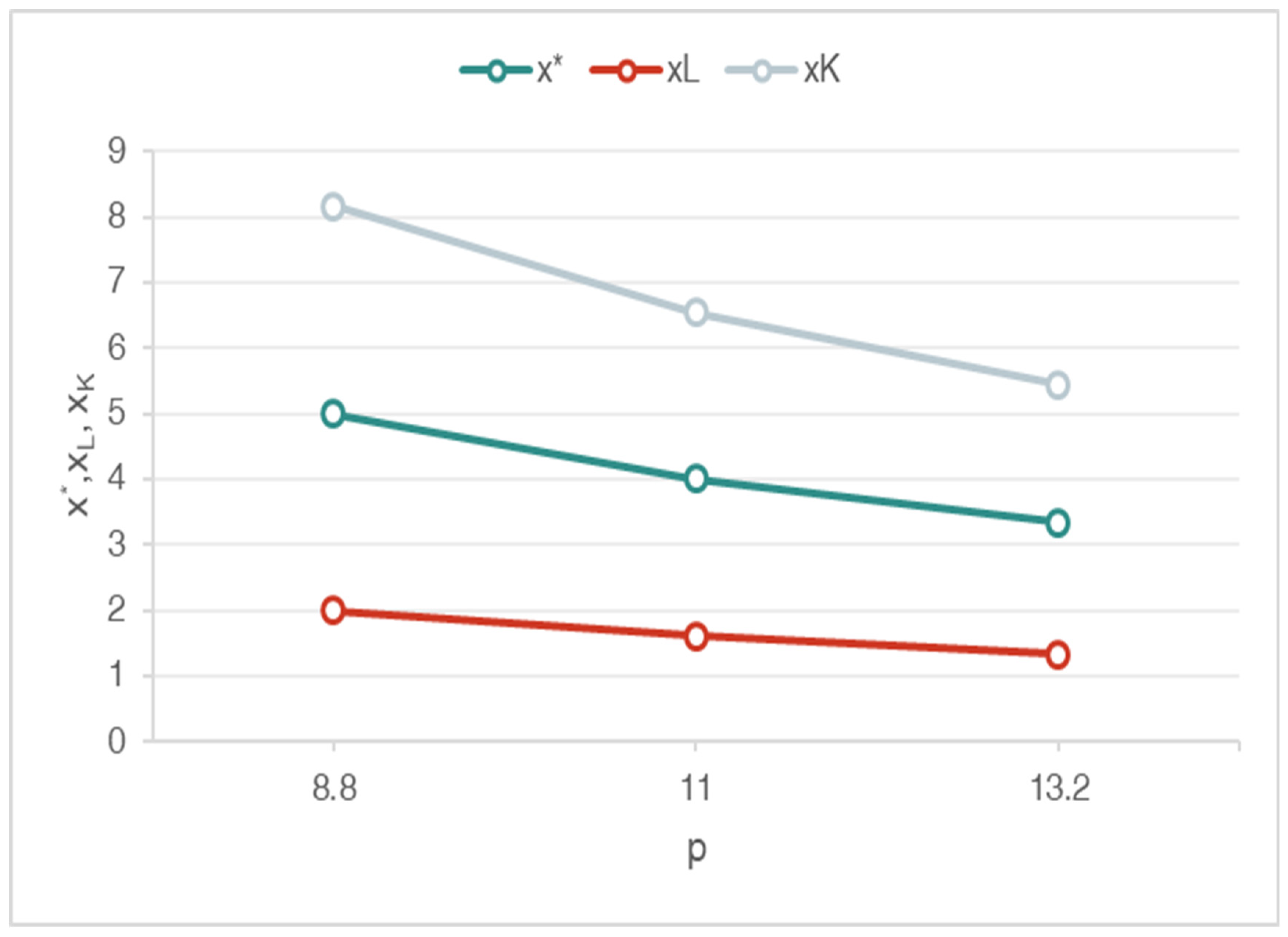

- The unit market price of honey mushrooms p is equal to p = 11 EUR/kg.

- We assume that B increases linearly with the stock xt (i.e., ξ = 1). Consequently, Bxt = p xt.

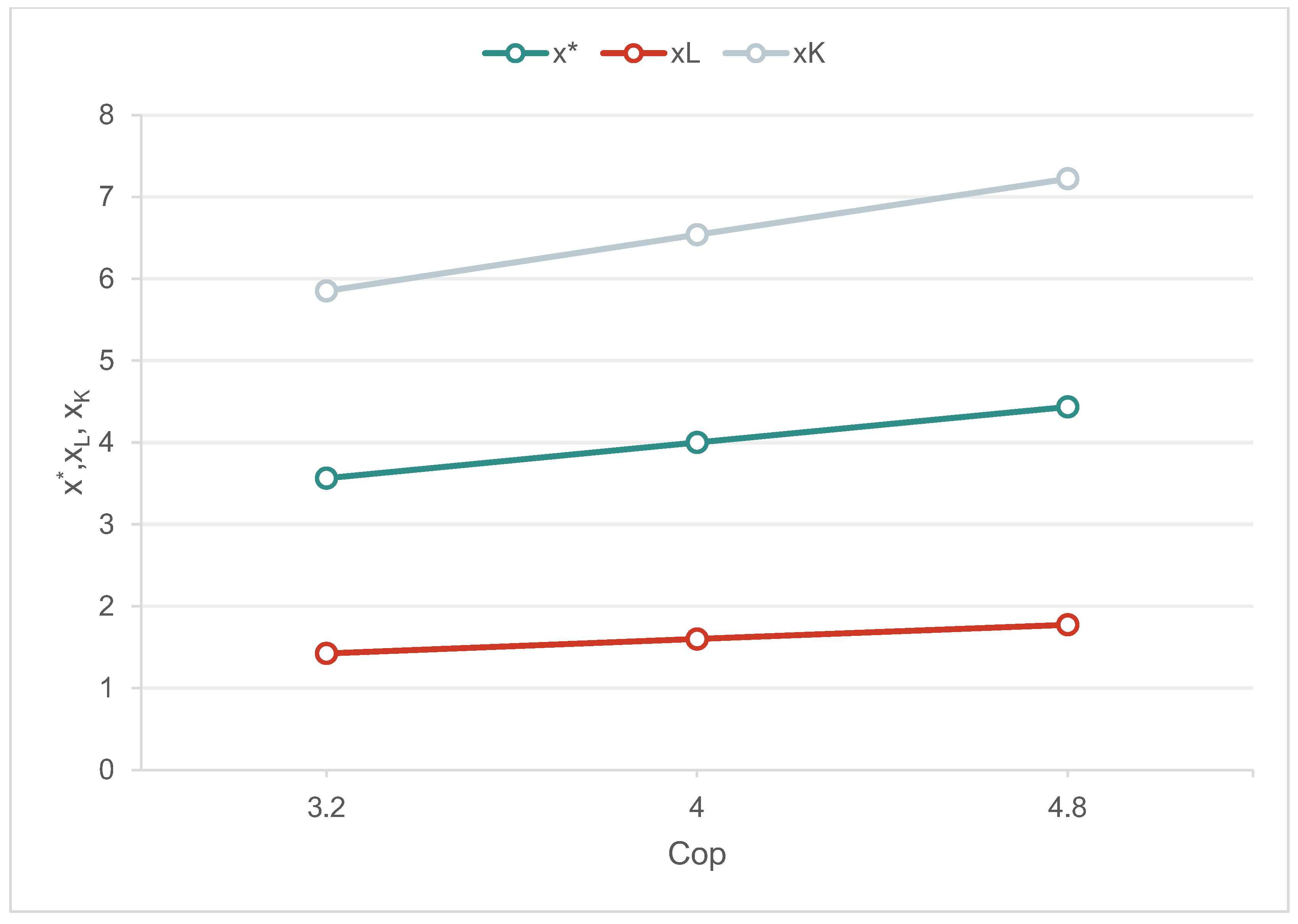

- Operating costs c account for the permit fee cp (that represents a fix cost, independent of the area extension) and the opportunity cost of time of the user co. The cost paid by each user for the annual permit fee is cp = 20 EUR/year, whereas we assume that the opportunity cost of the time spent in picking is about 30% [80] of the average hourly income per province, namely co = 4 EUR/h25. Consequently, operating costs paid by each user are equal to c = cp + tp·co, where tp = 6 h/year.

- To go picking mushrooms, the right holder must prove detailed knowledge of wild mushrooms and the ability to distinguish edible from non-edible mushrooms. Therefore, the right holder is requested to attend a specific one-off course. In other words, once the right holder has attended this course, they are not requested to take the course again if the picking takes place continuously for subsequent years. Nonetheless, if the right holder stops picking for one year, they must retake the course to start picking again26. Consequently, entry costs are equal to k = 60 EUR.

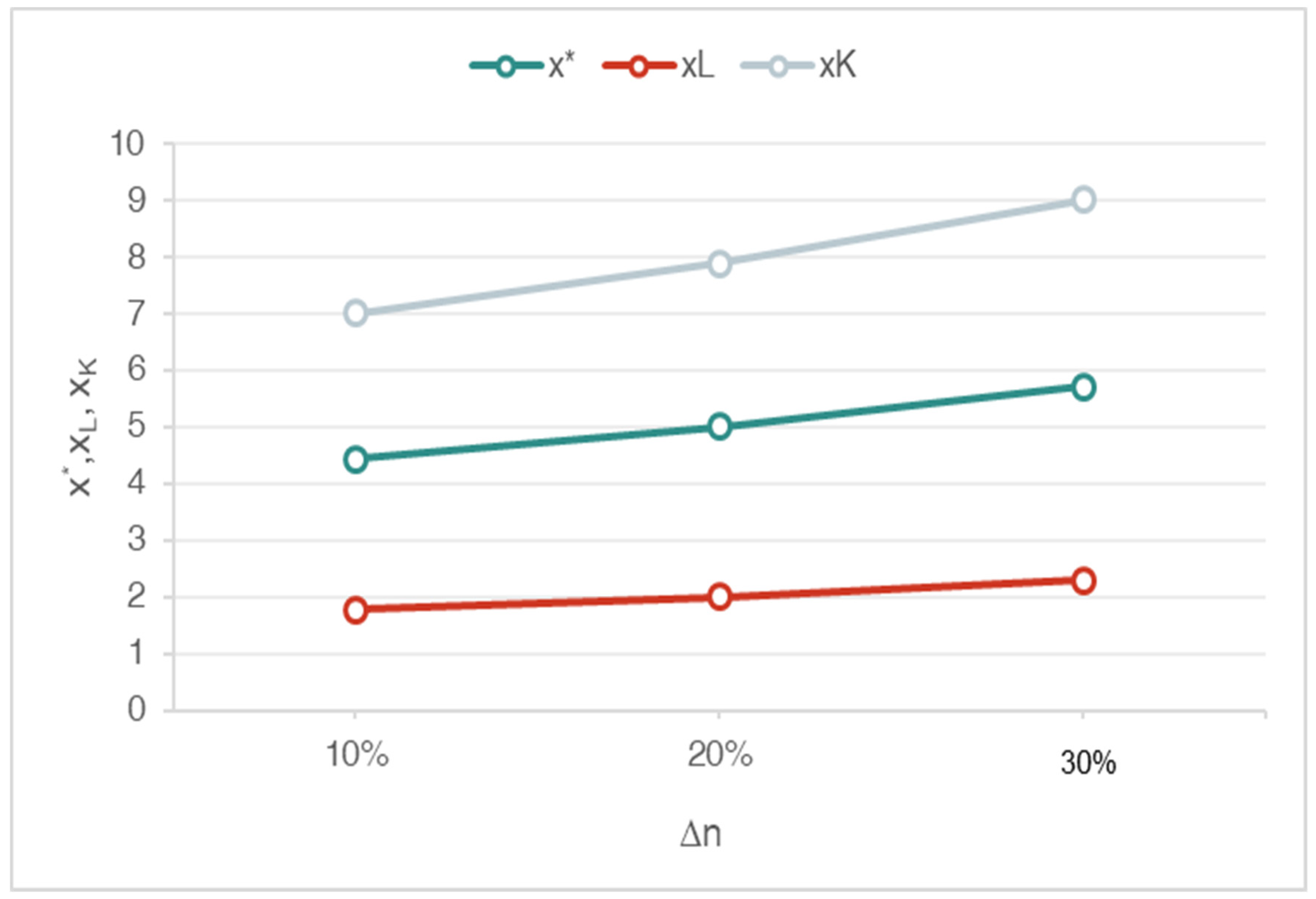

- The number of users per hectare is on average n = 7.2.

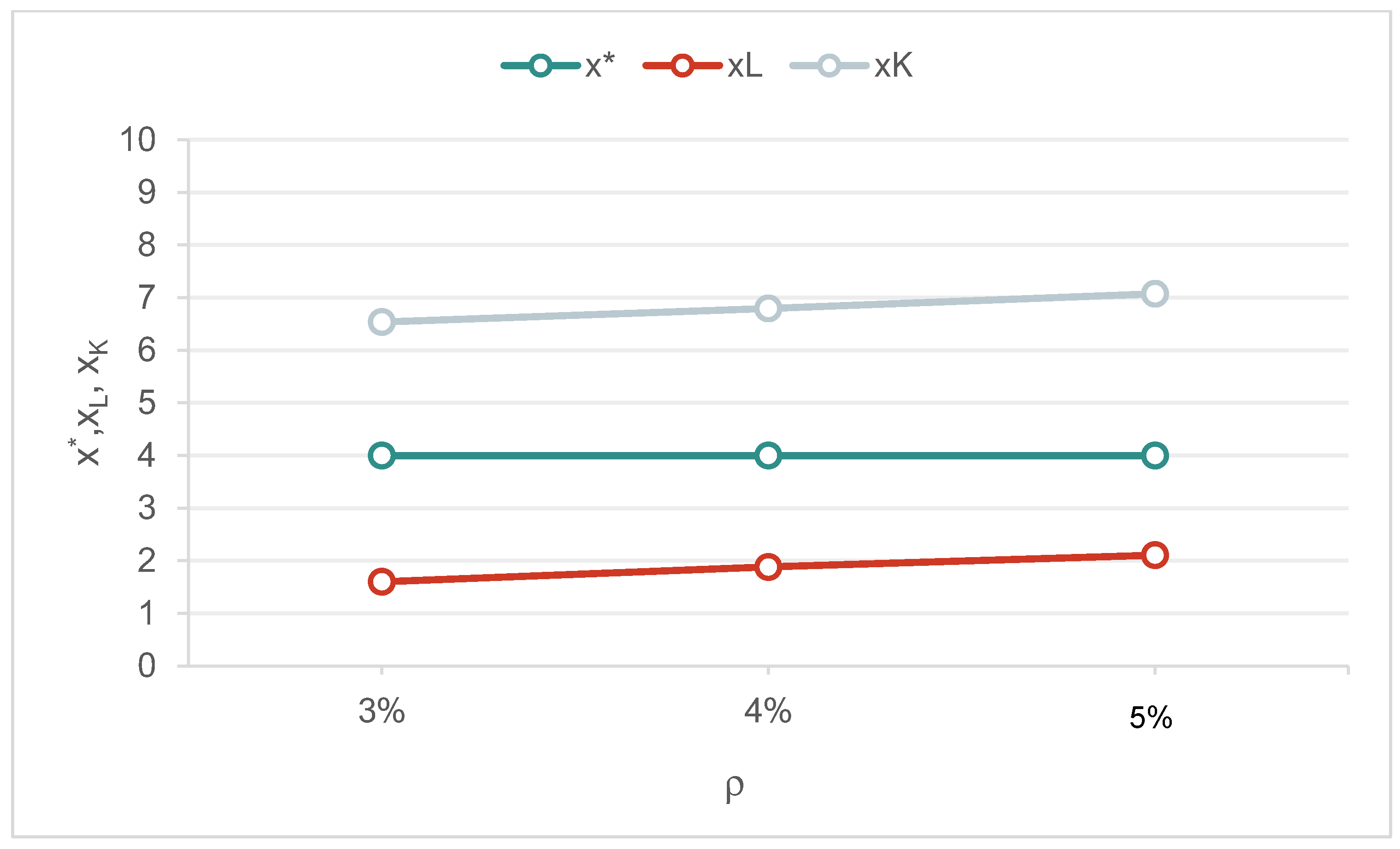

5.3. Results and Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | For example, aversion to risk can encourage collective use of resources whose future availability is uncertain. Thanks to this collective use, risk is shared by the entire community, thus reducing the possibility of one of the members being in an untenable situation. |

| 2 | This has occurred predominantly at the expense of publicly owned land. For example, in the 1600s, in the countryside of the Veneto Region, the rights to use common land for grazing and collecting dry grass and leaves for animal bedding and wood in the forests were alienated by the Venetian Republic under the pressure, on the one hand, of supply needs in the war against the Turks and, on the other hand, of the emerging aristocracy of landowners [6]. |

| 3 | See for example Law no. 1766 of 16th June 1927 on the reorganization of common property and subsequent amendments and supplements. |

| 4 | The definition of sustainability in resource use is controversial [13]. Nonetheless, if we adopt the definition provided by the Brundtland Commission, according to which “sustainable development is development that satisfies the needs of the present without compromising the needs of the future” [14] and we agree with the assumption of non-decreasing utility over time [15], the use of natural resources by these local communities can certainly be defined as sustainable. On the role of collective properties in the governance of natural resources, see also [16]. |

| 5 | The definition of externality is fairly elusive. In this context, an enlightening definition is the one proposed by Baumol and Oates [17], pp. 17–18, who subordinate the presence of externalities to two conditions: “(1) […] whenever some individual’s (say A’s) utility or production relationship include real (that is non-monetary) variables, whose values are chosen by others (persons, corporations, governments) without particular attention to the effects on A’s welfare; (2) the decision maker, whose activity affects others’ utility levels or enters their production functions, does not receive (pay) in compensation for this activity an amount equal in value to the resulting benefits (or costs) to others”. |

| 6 | |

| 7 | Hardin [8] predicted that a group of herders, who grazed their animals in an open-access pasture, would have destroyed the pasture by pursuing their immediate, private interests (i.e., adding an increasing number of animals) and ignoring any detriment they imposed on others or themselves over time [8,12,23,24,25,26]. |

| 8 | For example, it is difficult to know the exact amount of mushrooms, fish, or game animals available for the user in a specific area due to the uncertainty that affects environmental and meteo-climatic conditions. |

| 9 | |

| 10 | In this regard, it is helpful to recall the regional law no. 26 dated 19.8.96 “Reorganization of rules” in which the Veneto Region Authorities explicitly recognized the role of common property in safeguarding the environment and local development and laid down the rules for promoting their reconstitution. |

| 11 | Interactions between users are beyond the scope of the paper as well as the type of equilibrium that users may reach at aggregate level. |

| 12 | The utility flow is affected by the uncertainty over the stock’s future availability, due to both natural and anthropogenic causes. |

| 13 | The number of users remains constant over time, because it is indeed related to established habits and practice, which barely changes over time. |

| 14 | It should be noted that the problem faced by a single user who shares the resource with others differs from the problem addressed by the policymaker who needs to consider the aggregate benefit of all the users. In this context, the user, if rational, will consider in their benefit function the evolution over time of the stock available, include an assessment of the stock amount in their benefit function, and this assessment will vary inversely with the number of rival users [66]. |

| 15 | |

| 16 | |

| 17 | If the right holder decides to re-start using the resource, they will incur a new outlay k [74]. |

| 18 | For example, the exit cost may relate to the cost paid to restore the resource to its pristine state. |

| 19 | Some representative examples of weak regulation in Italy can be found at https://www.valdizoldo.net/en/things-to-do/outdoor-experiences/mushroom-picking-dolomites and https://www.parcoforestecasentinesi.it/en/living-the-park/activity/mushroom-picking (accessed on 8 April 2023). |

| 20 | Input data have been collected from ISTAT database and reports, technical reports on agriculture production, specific market analysis and direct interviews administered to representatives of local associations and mushroom pickers in the area under investigation in 2022. |

| 21 | These data were driven from interviews administered to representatives of local associations and mushroom pickers in the area under investigation in 2022. |

| 22 | Average annual production per hectare in the area under investigation is about 80 kg/ha (see, e.g., www.ismeamercati.it; funghimagazine.it) (accessed on 8 April 2023). |

| 23 | A variation in the number of pickers per hectare by +/−1 individual (i.e., Δn = ±1), generate a variation in the stock annual growth rate equal to +/−0.22%. Therefore, as this variation is negligible, we assume that μ(n) = 0. |

| 24 | These data were driven from analysis conducted in technical reports on agriculture. |

| 25 | Data driven from www.istitutotagliacarne.it and [81]. |

| 26 | See, e.g., http://www.agrariacampagnano.it/index.php/eventi/19-corsi/41-corso-per-il-riconoscimento-dei-funghi-epigei-spontanei (accessed on 8 April 2023). |

References

- Forni, G. Società e agricoltura preistoriche nelle regioni montane della padania. Riv. Stor. Dell’agricoltura 1972, 12, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Sereni, E. Comunità Rurali Nell’italia Antica; Rinascita Edizioni: Roma, Italy, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Pouta, E.; Sievänen, T.; Neuvonen, M. Recreational wild berry picking in Finland—Reflection of a rural lifestyle. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2006, 19, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Mitsumata, G.; Bergius, N.; Shimada, D. People’s outdoor behavior and norm based on the Right of Public Access: A questionnaire survey in Sweden. J. For. Res. 2023, 28, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlo, M. Common Property Forest Management in Northern Italy: An Historical and Socio-economic Profile. Unasylva 1995, 180, 58–63. [Google Scholar]

- Pitteri, M. Segar le Acque; Comune di Quinto di Treviso: Treviso, Italy, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Acerbo, G. Il Riordinamento Degli Usi Civici del Regno; Edizioni Calderini: Bologna, Italy, 1924. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blomquist, W.; Ostrom, E. Institutional Capacity and The Resolution of A Commons Dilemma. Rev. Policy Res. 1985, 5, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Coping with the tragedies of the commons. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 1999, 2, 493–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Reformulating the commons. Swiss Political Sci. Rev. 2000, 6, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Nagendra, H. Insights on linking forests, trees, and people from the air, on the ground, and in the laboratory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 19224–19231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howarth, B.H. Defining Sustainability: An Overwiev. Land Econ. 1997, 73, 445–447. [Google Scholar]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2023).

- Pearce, D.W.; Turner, R.K. Economics of Natural Resources an the Environment; John Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschetti, G. Verso l’integrazione tra politica agricola e politica ambientale in aree montane: Alcuni strumenti operativi. Riv. Politica Agrar. 1999, 5, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Baumol, W.J.; Oates, W.E. The Theory of Environmental Policy; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Moretto, M.; Rosato, P. The Use of Common Property Resources: A Dynamic Model; FEEM Nota di Lavoro: Milano, Italy, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, A.M. The Signe and Size of Option Value. Land Econ. 1984, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, J.M. Resource Economics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, A.; Pindyck, R.S. Investment under Uncertainty; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Trigeorgis, L. Real Options: Managerial Flexibility and Strategy in Resource Allocation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E.; Walker, J.; Gardner, R. Covenants with and without a Sword: Self-Governance Is Possible. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1992, 86, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlager, E.; Ostrom, E. Property-rights regimes and natural resources: A conceptual analysis. Land Econ. 1992, 68, 249–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Lam, W.F.; Lee, M. The Performance of Self-Governing Irrigation Systems in Nepal. Hum. Syst. Manag. 1994, 13, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E.; Burger, J.; Field, C.B.; Norgaard, R.B.; Policansky, D. Revisiting the commons: Local lessons, global challenges. Science 1999, 284, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. An alternative perspective on democratic dilemmas. Rev. Policy Res. 1985, 4, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriacy-Wantrup, S.V.; Bishop, R.C. “Common property” as a concept in natural resource policy. Nat. Resour. J. 1975, 15, 713–727. [Google Scholar]

- Bromley, D.W. Environment and Economy: Property Rights and PublicPolicy; Basil Blackwell: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Collective action and the evolution of social norms. J. Econ. Perspect. 2000, 14, 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S. Istitutional Structures and Regulation on Community Owned Forests in the Province of Trento, Italy; Jobst, H., Merlo, M., Venzi, L., Eds.; Institutional Aspects of Managerial Economics and Accounting in Forestry; IUFRO: Vienna, Austria, 1998; pp. 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Kissling-Naf, I.; Volken, T.; Bisang, K. Common property and natural resources in the Alps: The decay of management structures? For. Policy Econ. 2002, 4, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievänen, T.; Neuvonen, M.; Pouta, E. Recreational Home Users—Potential Clients for Countryside Tourism? Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2007, 7, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svanberg, I.; Lindh, H. Mushroom hunting and consumption in twenty-first century post-industrial Sweden. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomedicine 2019, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquina, T.; Emery, M.; Patrick Hurley, P.; Gould, R.K. The ‘quiet hunt’: The significance of mushroom foraging among Russian-speaking immigrants in New York City. Ecosyst. People 2022, 18, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházka, P.; Soukupová, J.; Tomšík, K.; Mullen, K.J.; Čábelková, I. Climatic Factors Affecting Wild Mushroom Foraging in Central Europe. Forests 2023, 14, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, T.; Hobby, T. The chanterelle mushroom harvest on northern Vancouver Island, British Columbia: Factors relating to successful commercial development. BC J. Ecosyst. Manag. 2010, 11, 72–83. [Google Scholar]

- Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Domínguez-Torres, G.; Prokofieva, I. Understanding forest owners’ preferences for policy interventions addressing mushroom picking in Catalonia (north-east Spain). Eur. J. For. Res. 2015, 134, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowski, M. Differences between European regulations on wild mushroom commerce and actual trends in wild mushroom picking. Slowak Ethnol. 2016, 64, 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Qwarse, M.; Moshi, M.; Mihale, M.J.; Marealle, A.I.; Sempombe, J.; Mugoyela, V. Knowledge on utilization of wild mushrooms by the local communities in the Selous-Niassa Corridor in Ruvuma Region, Tanzania. J. Yeast Fungal Res. 2021, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Gorriz-Mifsund, E.; Secco, E.; Da Re, R.; Pisani, E.; Bonet, A.P. Cognitive social capital and local forest governance: Community ethnomycology grounding a mushroom picking permit design. For. Syst. 2023, 32, e001. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, M.; Arnold, G.; Villamayor, T.S. A review of design principles for community-based natural resource management. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, J.S. Key principles of community-based natural resource management: A synthesis and interpretation of identified effective approaches for managing the commons. Environ. Manag. 2010, 45, 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Pettenella, D.; Vidale, E. Income generation from wild mushrooms in marginal rural areas. For. Policy Econ. 2010, 13, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Procházka, P.; Soukupová, J.; Mullen, K.J.; Tomšík, K.; Čábelková, I. Wild Mushrooms as a Source of Protein: A Case Study from Central Europe, Especially the Czech Republic. Foods 2023, 12, 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cori, V.; Franceschinis, C.; Robert, N.; Pettenella, D.M.; Thiene, M. Moral foundations and willingness to pay for non-wood forest products: A study in three european countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, L.; Li, C. The non-timber value of northern Swedish forests: An economic analysis. Scand. J. For. Res. 1993, 8, 426–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, L.; Nordlund, A.M.; Olsson, O.; Westin, K. Recreation in different forest settings: A scene preference study. Forests 2012, 3, 923–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochmalová, M.; Purwestri, R.C.; Yongfeng, J.; Jarský, V.; Riedl, M.; Yuanyong, D.; Hájek, M. Demand for forest ecosystem services: A comparison study in selected areas in the Czech Republic and China. Eur. J. For. Res. 2022, 141, 867–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusté-Forné, F. Seasonality in food tourism: Wild foods in peripheral areas. Tour. Geogr. 2022, 24, 578–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, T.; Jones, E.; Liegel, L. Valuing the temperate rainforest: Wild mushrooming on the Olympic Peninsula Biosphere Reserve. Ambio 1998, 27, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Starbuck, C.M.; Alexander, S.J.; Berrens, R.P.; Bohara, A.K. Valuing special forest products harvesting: A two-step travel cost recreation demand analysis. J. For. Econ. 2004, 10, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez de Aragón, J.; Riera, P.; Giergiczny, M.; Colinas, C. Value of wild mushroom picking as an environmental service. For. Policy Econ. 2011, 13, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini Govigli, V.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Varela, E. Zonal travel cost approaches to assess recreational wild mushroom picking value: Trade-offs between online and onsite data collection strategies. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 102, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vail, D.; Hultkrantz, L. Property rights and sustainable nature tourism: Adaptation and mal-adaptation in Dalarna (Sweden) and Maine (USA). Ecol. Econ. 2000, 35, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osés-Eraso, N.; Viladrich-Grau, M. On the sustainability of common property resources. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2007, 53, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J. A legal approach to induce the traditional knowledge of forest resources. For. Policy Econ. 2014, 38, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Marini Govigli, V.; Bonet, J.A. What to do with mushroom pickers in my forest? Policy tools from the landowners’ perspective. Land Use Policy 2017, 63, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokofieva, I.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Bonet, J.A.; Martínez de Aragón, J. Viability of Introducing Payments for the Collection of Wild Forest Mushrooms in Catalonia (North-East Spain). Small-Scale For. 2017, 16, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez, C.A.; Murphy, J.J.; Stranlund, J.K. Managing and defending the commons: Experimental evidence from TURFs in Chile. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2018, 91, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safarzynska, K. The Impact of Resource Uncertainty and Intergroup Conflict on Harvesting in the Common-Pool Resource Experiment. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2018, 71, 1001–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Frutos, P.; Rodríguez-Prado, B.; Latorre, J.; Martínez-Peña, F. Environmental valuation and management of wild edible mushroom picking in Spain. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 100, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abatayo, A.L.; Lynham, J. Resource booms and group punishment in a coupled social-ecological system. Ecol. Econ. 2023, 206, 107730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaglio, M.; Lanzoni, M.; Goggi, F.; Fano, E.A.; Castaldelli, G. Integrating payment for ecosystem services in protected areas governance: The case of the Po Delta Park. Ecosyst. Serv. 2023, 60, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, A. Common Property Institutions and Sustainable Governance of Resources. World Dev. 2001, 29, 1649–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnason, R. Minimum Information Management in Fisheries. Can. J. Econ. 1990, 23, 630–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.R.; Miller, H.D. The Theory of Stochastic Process; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J.M. Brownian Motions and Stochastic Flow Systems; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, M.B. Some aspects of the dynamics of populations important to the management of the commercial marine fisheries. Bull. Math. Biol. 1991, 53, 253–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alpaos, C.; Dosi, C.; Moretto, M. Concession length and investment timing flexibility. Water Resour. Res. 2006, 42, W02404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Corato, L.; Moretto, M.; Vergalli, S. The effects of uncertain forest conservation benefits on long-run deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2018, 23, 413–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buso, M.; Dosi, C.; Moretto, M. Do exit options increase the value for money of public–private partnerships? J. Econ. Manag. Strategy 2021, 30, 721–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreolli, F.; D’Alpaos, C.; Moretto, M. Valuing investments in domestic PV-Battery Systems under uncertainty. Energy Econ. 2022, 106, 105721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, A. Entry and Exit Decisions under Uncertainty. J. Political Econ. 1989, 97, 620–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirole, J. The Theory of Industrial Organization; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Moretto, M. A Note on Entry-Exit Timing with Firm-Specific Shocks. G. Degli Econ. E Ann. Di Econ. 1996, 55, 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- AA.VV. Il Quadro Conoscitivo Dell’agroambiente del Comune di Trebaseleghe (PD). 2006. Unpublished Report. Available online: https://cloudsit.provincia.padova.it/s/xPc7C04HQhyfBEF (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- ISTAT. Agricoltura—Dati 2020. 2022. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/agricoltura?dati (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- ISTAT. Popolazione e Famiglie. 2023. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/popolazione-e-famiglie (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- Garrod, G.; Willis, K.G. Economic Valuation of the Environment: Methods and Case Studies; Edward Elgar: Celthenham, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT. Condizioni di Vita e Reddito Delle Famiglie. 2023. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files//2022/10/Condizioni-di-vita-e-reddito-delle-famiglie-2020-2021.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- HM Treasury. The Green Book—Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation; HM Treasury: London, UK, 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-green-book-appraisal-and-evaluation-in-central-governent (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- Pacheco-Cobos, L.; Winterhalder, B.; Cuatianquiz-Lima, C.; Hudson, R.; Ross, C.T. Nahua mushroom gatherers use area-restricted search strategies that conform to marginal value theorem predictions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10339–10347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaaronen, R.O. Mycological rationality: Heuristics, perception and decision-making in mushroom foraging. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2020, 15, 630–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egli, S.; Peter, M.; Buser, C.; Stahel, W.; Ayer, F. Mushroom picking does not impair future harvests—results of a long-term study in Switzerland. Biol. Conserv. 2006, 129, 271–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breheny, E. Foraging Has Absolutely Skyrocketed’: Mushroom Pickers Revel in Bumper Season’, The Age. 2023. Available online: https://www.theage.com.au/goodfood/melbourne-eating-out/foraging-has-absolutely-skyrocketed-mushroom-pickers-revel-in-bumper-season-20230518-p5d9jo.html (accessed on 8 June 2023).

- Sloss, L. Mushroom Boom: How to Plan a Foraging Adventure on the West Coast. The New York Times. 23 February 2023. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/02/23/travel/mushroom-foraging-west.html. (accessed on 8 June 2023).

| Excludability | Harvest Control | Rivalry | Resource Topology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Difficult | Difficult | High | Common-pool |

| Difficult | Difficult | Low | Pure public |

| Easy | Difficult | Low | Club |

| Easy | Difficult | High | Common-property |

| Easy | Easy | High | Pure private |

| Initial Situation | Options | State of the Resource |

|---|---|---|

| The user currently uses | continues to use | xt ≥ xL |

| stops using | ||

| The user currently does not use | continues not to use | |

| begins using |

| Hysteresis (ΔKL) | Hysteresis (ΔKL) | |

|---|---|---|

| Resource Situation | Low | High |

| Unstable abandonment | Stable abandonment | |

| Unstable stagnation | Stable stagnation | |

| Unstable use | Stable use |

| Benchmark Case | Comparative Statics | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ | 30% | 20% | 40% | |

| p (EUR/kg) | 11 | 8.8 | 13.2 | |

| cop (EUR/h) | 4 | 3.2 | 4.8 | |

| n (ind/ha) | 7.2 | +10% | +20% | +30% |

| ρ | 3% | 4% | 5% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Alpaos, C.; Moretto, M.; Rosato, P. Common-Property Resource Exploitation: A Real Options Approach. Land 2023, 12, 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071304

D’Alpaos C, Moretto M, Rosato P. Common-Property Resource Exploitation: A Real Options Approach. Land. 2023; 12(7):1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071304

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Alpaos, Chiara, Michele Moretto, and Paolo Rosato. 2023. "Common-Property Resource Exploitation: A Real Options Approach" Land 12, no. 7: 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071304

APA StyleD’Alpaos, C., Moretto, M., & Rosato, P. (2023). Common-Property Resource Exploitation: A Real Options Approach. Land, 12(7), 1304. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12071304