Abstract

A cultural landscape is a complex and integrating concept with both material–physical and immaterial substance. Nevertheless, even today, the strategies for the protection and promotion of cultural landscapes are concentrated only at their material cultural elements, separated from their immaterial existence, or even from the natural environment in which they are placed. This study investigates the correlation of the tangible historical and natural heritage of a cultural landscape with its intangible content, as a spatial planning tool for its sustainable development. The proposed methodology was applied in the region of the Mani Peninsula, located in the southern Peloponnese, in Greece. During the documentation stage, literature research and fieldwork provided descriptive information, which was classified through standardization processes. GIS management and analysis procedures were used among the different layers of data of the current preservation state and the existing development frameworks for the study area. New thematic cultural routes are proposed to connect tangible cultural heritage and environmental values of the region under study, with the landscape’s geomorphological characteristics and intangible content. Protected areas are also proposed for the protection of monuments and sites of historical or natural importance. The results of this study demonstrate that, through integrated strategic planning for the development of cultural activities and networks, which incorporates the principles of spatial and urban planning, not only is the protection of the natural and cultural wealth of the region achieved, but also a balanced economic development and social cohesion, which ultimately leads to sustainable development.

1. Introduction

Throughout the 20th century, the context of cultural heritage (CH) has expanded, from the individual monument to the recognition of heritage’s intangible dimension, and from archaeological or historical sites to the recognition of the cultural value of a territory [1]. These arguments emerged from the awareness of the strong connection between cultural and natural heritage, and concluded in the following definition of cultural landscape (CL) by UNESCO: “Cultural Landscapes are cultural properties that combine works of nature and man. They are illustrative of the evolution of human society and settlement over time, under the influence of the physical constrains and/or opportunities presented by their natural environment and successive social, economic and cultural, forces, both external and internal.” [2].

Within this concept, Europe’s CL is a complex and integrating concept with both material–physical and immaterial substance [3]: it originates from the continuous and dynamic interaction between human activities and natural processes [4] over very long periods of time, whereas it patronizes intangible values and symbols [3]. The formation and organization of European landscapes is based on the needs of the local communities and the prevailing ethical and aesthetic values [5]. Testimonies of these fermentations through time are not only the remaining individual elements that constitute the CL, such as the pattern and character of land cover and settlements, architecture, and auxiliary structures, but also the traditions, myths, folklore, gastronomy, and handicrafts that were developed within this specific environment, thus forming an integrated system of resources.

The preservation and management of CL fits in the framework of cultural and natural heritage protection [3], as it is evident in the recent policies of many European countries [6,7] and has become the subject of numerous conventions, charters, and operational guidelines by international organizations, such as the Council of Europe, ICOMOS, UNESCO, etc. [8]. To this scope, one of the mechanisms adopted by the European Landscape Convention for the promotion of landscape protection is the integration of landscape into spatial planning, environmental, and agricultural policies [9]. Such policies and strategies mainly focus on safeguarding rural landscapes with their local communities and economies, considering the negative changes and risks that have arisen from the socioeconomic fermentation of the past decades: industrialization and urbanization trends [10], mass tourism development, land abandonment, agricultural intensification, etc. [11].

Following the acknowledge of cultural expressions and traditions as intangible heritage by UNESCO (2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage), the scientific community turned to the connection between the rural landscape and its cultural territorial identity, emphasizing the intangible dimension in a rural landscape context, rather than built or tangible cultural heritage (TCH) [12]. In recent years, the interconnection of a CL with its intangible cultural heritage (ICH) is gaining ground with regard to the strategies for the sustainable development of a rural area: the concept of cultural routes (CRs) and itineraries as a mechanism of integrating tangible and intangible heritage into a touristic experience [13,14] have led to the formation of alternative tourism activities, under the term of slow tourism [2], which stimulate and promote local products [14]. In this direction, Terzić and Bjeljac [15] highlight the importance of the collaboration between CRs and the tourism sector, and proposes a tourist evaluation method for the heritage properties within CRs, in order to define the actions needed to improve the current state of a rural region in terms of sustainable tourism [16]. The immaterial consistence of CRs, as dynamic testimonies of historical processes, distinguish them from other contemporary trails or routes that are formed only to connect individual material assets of CH, mainly for touristic purposes [17].

In recent years, several studies presenting the utilization of the CR concept towards the sustainable exploitation of a CL and CH, in general, stressed the necessity for a multidimensional approach on CR management. Such a necessity is more urgent in European territories, where culture is recognized as a strong link among European nations: Europe’s CRs are organized in networks, aiming at the promotion of cultural diversity within a common cultural framework. A key objective of Europe’s CR networks is the promotion of an intercultural and interreligious dialogue through a better understanding of European history, in order to raise awareness of a European cultural identity [18]. To this aim, the common theme under which the European CR networks are formed is of great importance, and it is identified and established by the corresponding Resolutions of the Council of Europe [19].

Within this concept, a number of studies focus on the development of strategies and policies for the conservation and enhancement of lesser-known European CL [20], through the highlighting of tangible and intangible cultural heritage, and the achieving of competitive tourism attractions, arising from CR networks. To this scope, G. Cassalia et al. [21] proposed the formation of a CR network model, following an economic, historical-anthropological, operational, and policies approach: the areas included in the CR network were selected based on geographic, size, and infrastructure criteria, whereas the CR theme was selected based on common religious culture and the criteria defined by the Council of Europe. The proposed operational model of T. Meduri et al. [22] for the valorization planning of undeveloped rural areas in connection to a metropolitan center was based on a three-sectional system: a built-environment system, including the TCH of the region; a socio-cultural system, including the ICH of the region; and a production system, including local products. In their study, the CR theme was a specific tangible tool that identified the territory under study and promoted the involvement of the local population.

The critical role of the local population in CR management is also highlighted by Severo [23]. In her study, CRs are being study through the concept of CL: in such a sense, the value of a CR is defined by its tangible and intangible cultural assets, whereas CR planning is considered to be a subject of the participation of all involved actors (local community and tourists). Bogacz-Wojtanowska et al. [24] also investigate the role of the local community in CR organization: CRs should not be perceived only as a touristic product based on the tangible resources of its region, but as a dual means of influence between the landscape and local community. Zhou et al. [25] promote the participation of the local community in CR planning through the conducting of interviews with the locals in order to frame the intangible essence of the CL in relation to its tangible and ecological context.

However, the available scientific research in the field of CL safeguarding shows some deficiencies regarding CL and ICH interrelation, since:

- (a)

- the proposed sustainable development plans do not take into consideration the intangible essence of a CL, as the context of its CH that needs to be protected: the sustainable development of a rural area is currently identified with its tourism development through the use of CR which only serve touristic purposes, whereas the participation of local communities is limited to the promotion of local products; or

- (b)

- when the ICH importance under the notion of gastronomy, traditions, or cultural events has been integrated in rural development strategies, as recreation experiences through tourism activities, the environmental value of the CL is being ignored.

Within this framework, the need for the preservation of CL as a whole, with their individual cultural and natural context, is more urgent than ever. This need, followed by the complexity and integration of various concepts in a landscape, generates the importance of an integrated multidisciplinary approach on CL protection [26,27]: a requirement that seems urgent in the aspect of managing, protecting, and promoting the cultural and natural resources of an area, characterized by diversity in terms of urban and regional planning, soil physiognomy, and natural, residential, and building stock, with a view to achieving its sustainable development, through achieving balanced economic growth, social cohesion, competitiveness, and the protection of the environment and natural resources.

To this aim, in this work, an integrated approach for the protection and promotion of historical and traditional CL is examined, in which all the substances and essences of the landscape, both as a united whole and as isolated cultural elements, are concluded and highlighted: in a landscape with cultural and natural resources, we propose CR planning based on ICH, aiming at the preservation of the ICH and the sustainable development of the wider rural environment. Since tangible with intangible heritage are strongly connected, we also propose buffer zones for the protection and preservation of CH and CL on the site.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. General Description of the Area under Investigation

Specific traditional landscapes in rural Europe present unique historical, natural, and aesthetical values, which make them worth preserving as part of Europe’s CH [28]. One of these landscapes is in Mani Peninsula in southern Greece, where distinctive historical conditions prevailing in the area for a long time, such as the constant struggle for independence and dominance, and the particular geographical substance, were strongly imprinted in the built environment and formed a unique social cohesion, with the formation of powerful clans, and tradition, mainly with reference to armed conflicts and defense, thus creating a rare, large-scale, and high-value historical, monumental, and aesthetic whole.

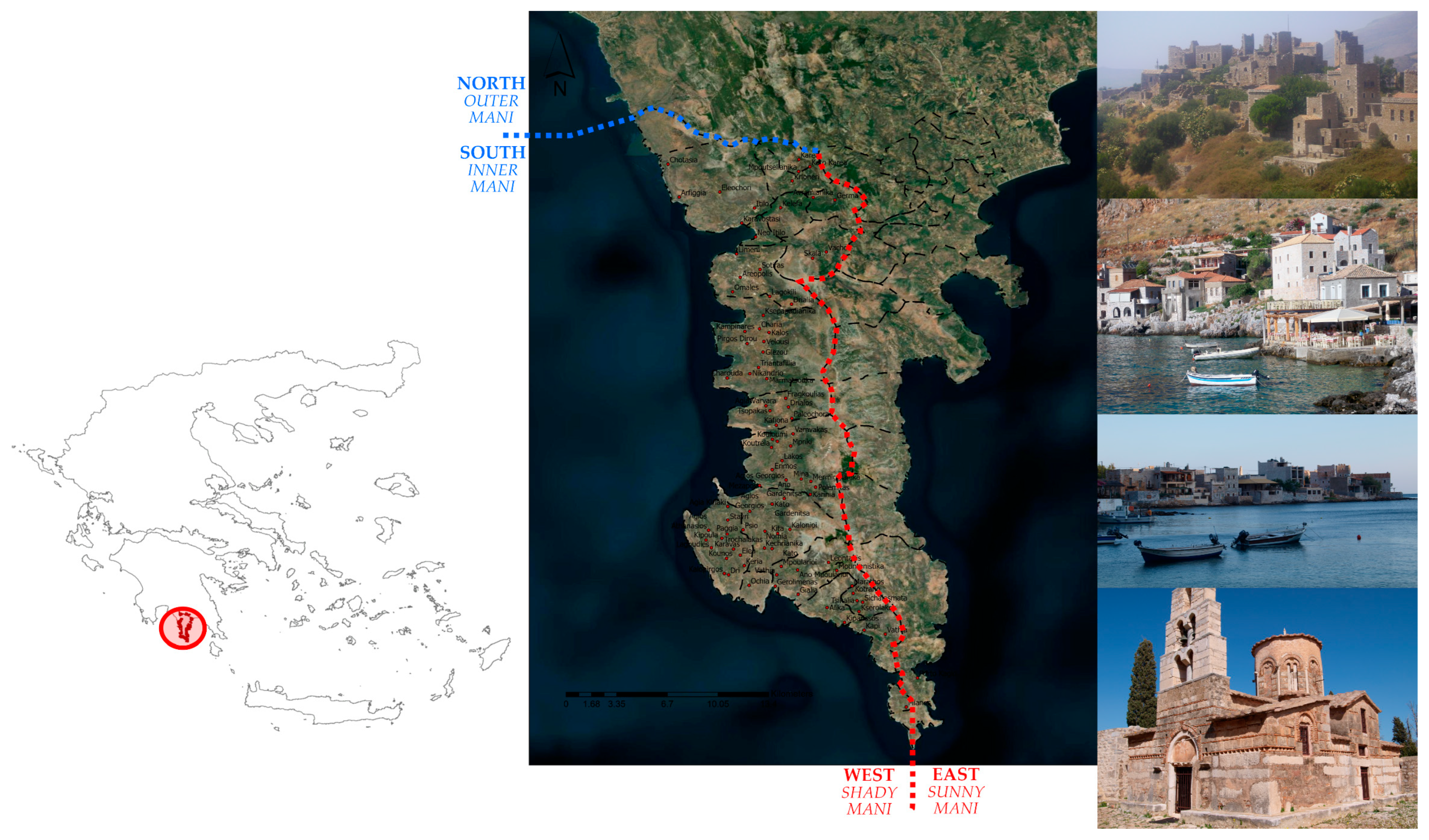

The region of Mani extends in an area of a total of 995.1 km2 on both sides of Taygetos Mountain and it is located in the southernmost and middle peninsula of the Peloponnese, including parts of the regional unities of Lakonia and Messinia. An imaginary line running almost east–west divides the region into the North or Outer Mani and the South or Inner Mani. Inner Mani is distinguished by the longitudinal ridge of Taygetos in the East or Sunny and the West or Shady Mani [29] (Figure 1). Historically, the area presents an unbroken sequence stretching from prehistoric times to the present day, which generated not only numerous monuments, traditional settlements, and interesting land formations, but also unique examples of traditional and intangible heritage. The area was an important core of political developments during the Greek Revolution of 1821 and in the creation of the newly established Greek state. Eastern Mani’s landscape is characterized by its pre-eminently fierce aspect, the paucity of low vegetation, and the dominating presence of stone. The preservation of Mani’s peninsula is subjected to Greek legislation on the protection of cultural and natural heritage, under EU directives. In addition, the promotion and protection of the area’s unique features is included in Greek national spatial policy with the elaboration of national and regional spatial development planning.

Figure 1.

Mani Peninsula divided into North or Outer Mani and South or Inner Mani (blue line), and East or Sunny and West or Shady Mani (red line).

2.2. Methodology and Documentation

Any protection management and planning in all fields of decision making in the framework of sustainable development requires a preceding detailed and analytical reading of the landscape’s historic, social, economic, cultural, and archaeological dimension [30]. Consequently, accuracy and graphic representation are essential for the planning process in CL protection [31] as it decisively contributes to the recognition of the past, the identification of the present, and provision of guidelines for the future [13].

The proposed methodology approach involves three levels of documentation:

- (a)

- an investigation of the study area to frame the scope of the study and to identify and recognize the broader social, economic, political, and cultural context in which the landscape under investigation was generated and transformed;

- (b)

- a detailed inventory of the current state of the landscape based on site observations and measurements to develop an accurate image of the natural and cultural features of the landscape; and

- (c)

- the development of a manual for the operation and recording of data, based on standardized procedures.

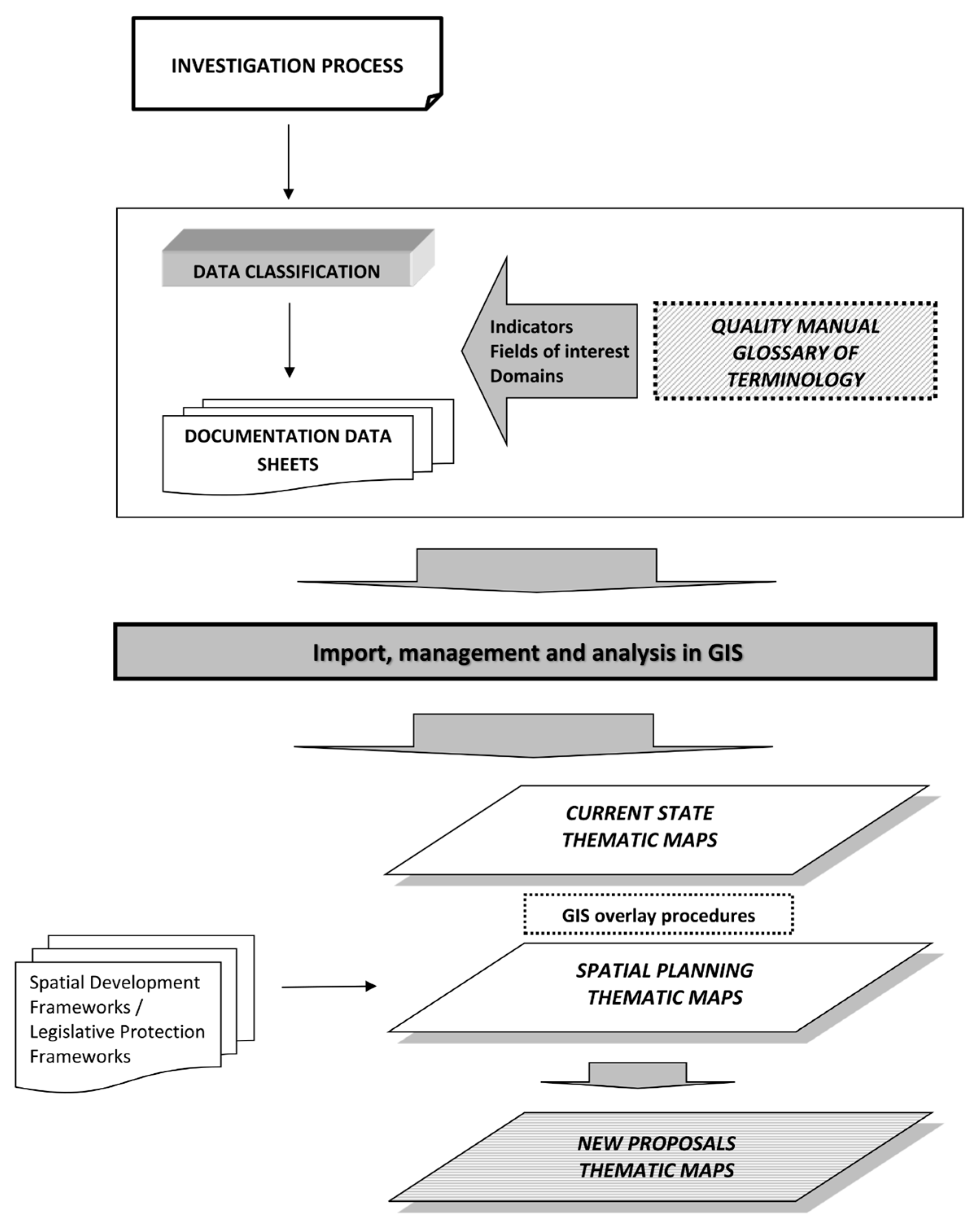

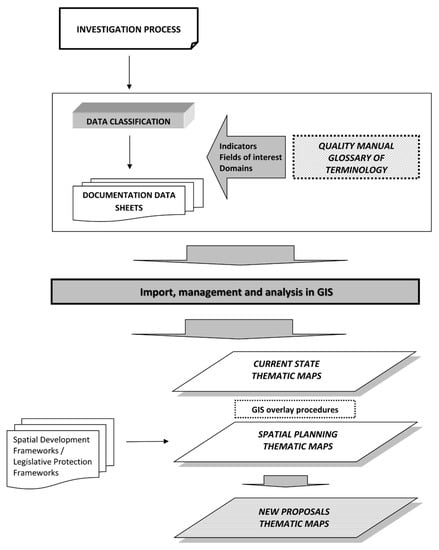

This methodology is based on methods previously proposed by the authors [32] for the preservation and sustainable development of areas of historic importance and natural beauty with reference to CRs, but in a smaller-scaled area. In this study, the previous methodology is extended to a region level, taking into account ICH and CL as development tools. Figure 2 shows the methodology flowchart for the current study.

Figure 2.

The methodology flowchart for the current study.

The basis for the design of the maps were the maps of the Geographical Service of the Army of the areas of Mani Peninsula, on a scale of 1/5000. A Geographic Information System (GIS) was used as a tool for the management and analysis of data recorded and classified in attribute data sheets.

Furthermore, research and analysis process has been performed on two levels: a superior landscape analysis concerning the whole area under investigation, and a more detailed level on the settlement scale with reference to the individual cultural structures, as shown in several other studies [33].

2.2.1. Investigation of the Study Area

As C. Sauer has noted, the study of written documents on a place is the essential starting place in background research [34] to develop a broad understanding of the place and provide the necessary basis of information to inform and direct the process of the current state inventory and analysis. In the case of Mani, the investigation was not limited to written reports, but also followed the rich tradition of the area, aspects of which continue to be present in the daily lives of the inhabitants to this day.

The objective of the investigation of the study area procedure followed the two levels of analysis. On the general level, bibliographic research aimed at understanding and identifying the historical, social, political, economic, and cultural framework on the formation and development of Mani’s landscape. The particular socio-political circumstances that led to the formation of the unique anthropogenic and natural environment were recorded, whilst, in parallel, the transformations of the landscape over time were studied, in relation to sociopolitical changes. Particular emphasis was placed on the spatial development of the region: the graduated organization and development of the settlements, directly related to social cohesion and residence unit evolution.

During this procedure, an initial inventory of the important monuments, settlements, and natural resources took place. This cataloging regarded the listed monuments and archaeological and historic sites by the Greek Ministry of Culture, traditional settlements and buildings instituted by the Greek Ministry of Environment Energy and Climate Change, as well as important public buildings, museums, existing hiking trails, and possible nature areas recognized by international, national, or local bodies and organizations. Additionally, the survey was directed to the research on data and characteristics concerning individual cultural and natural elements within the landscape, in all the related fields, such as history, anthropology, folklore, geography, and architecture. The data obtained at this point were not only descriptive, but also spatial and graphical, such as historic maps and pictures. Resources were based on authentic historical documents, documents and studies of modern historians, sociologists, and architects, as well as works of researchers and students with reference to Inner Mani, or any cultural and natural element on the site.

A particular category of sources for the investigation of the study area was the national planning policies and the approved or proposed spatial development frameworks for the area under investigation, at national, regional, and local level. These policies: (a) record the role of the region and development factors, (b) set the directions for its spatial organization, and (c) define the basic priorities and strategic options for an integrated and sustainable development of the area. In this case, more emphasis was given to the interpretation and understanding of maps accompanying planning frameworks.

Supplementary, legislative provisions governing the protection of CH were studied, both at individual monument and landscape scale, in Greece and Europe, as well as instructions, guidance, and directions of international organizations and bodies.

A first visit to the area under investigation was carried out during investigation procedures, where a primary recognition of the region was conducted. A series of onsite observations and measurements followed throughout the course of the study. Visits were defined based on a management plan that included the subjects under investigation per settlement.

In addition to the above, the research followed a second level of analysis for the study area: it focused on the rich tradition, the folklore, and the ethics of Eastern Mani through bibliographic research and interviews with local stakeholders and residents. These rich traditions were formed by the physiognomy of the landscape and the geographical characteristics of Mani Peninsula and expressed Maniots’ constant struggle for survival, autonomy, and domination through ages.

Additionally, prior to proposed intervention planning, the team organized several open meetings with the local authorities and stakeholders, tourist actors, and local communities, to set the priority axes, the key objectives, and the domains/limitations of the study, as well as thematic units of interest.

2.2.2. Data Classification

The large volume of information emerging from the bibliographic research and fieldwork highlighted the need for an effective data management system. To this aim, the necessary tools were searched to support the classification of the obtained information, to define study limitations and assumptions, and to provide the appropriate indicators for the structure of a unified and systematic method of recording.

Based on the bibliographic sources, internationally recognized databases, and on-site observations, a quality manual and glossary of terminology (QMGT) was created for each field of interest, in order to define and describe the required indicators/fields of reference for the evaluation and classification of data, as well as the constraints and domains by area of interest. The attribute data of GIS were based on the proposed QMGT. These indicators determined the assumptions, the criteria, and the range of values for information structure. The research for the applied data classification and evaluation indicators included: (a) international frameworks for the standardization of procedures, (b) internationally recognized standards of definitions and concepts, (c) elements of architectural interest, and historically recorded morphological and typological patterns as characteristics of specific architectural style and periods of time, as well as (d) the very characteristics that give each place its distinctiveness.

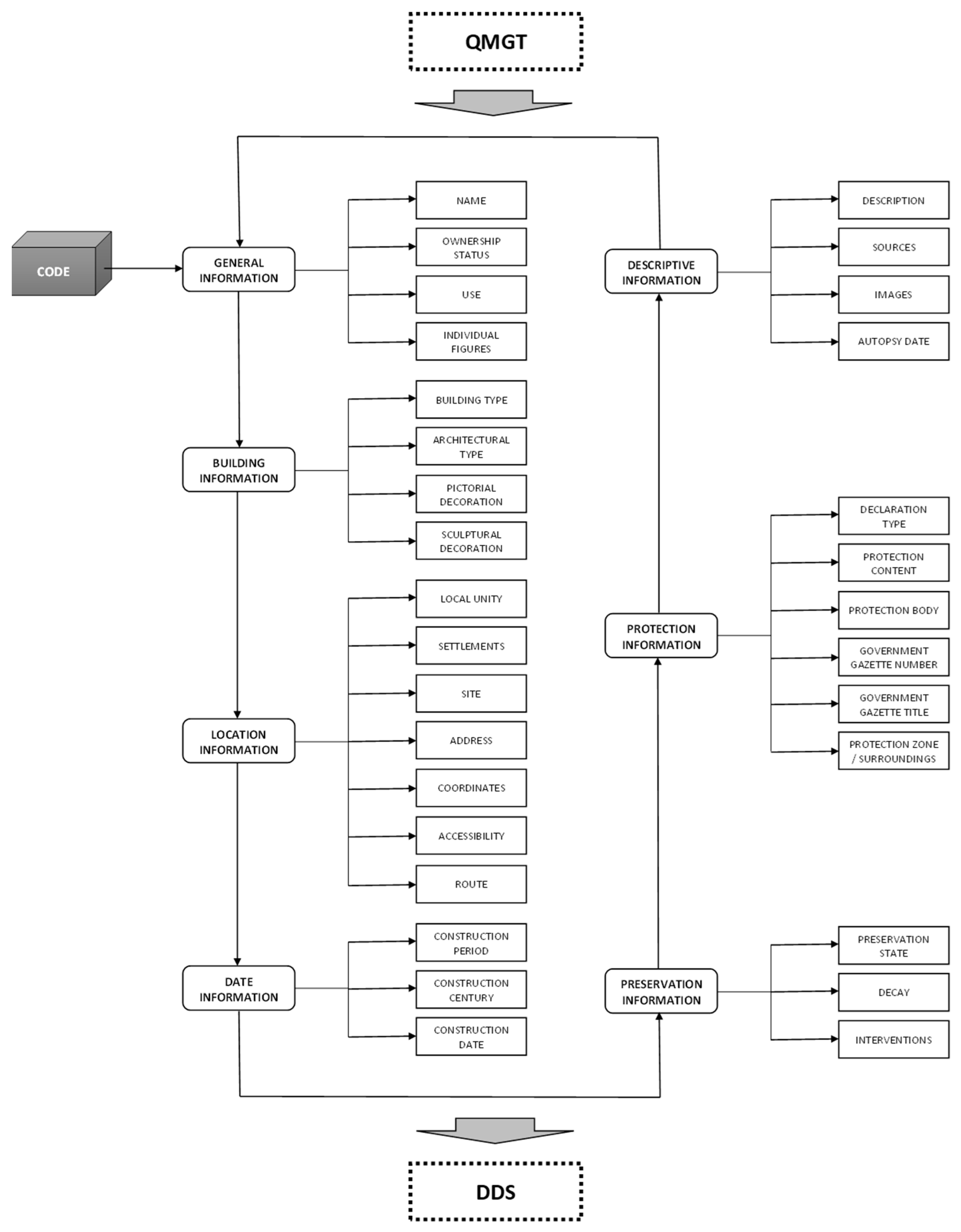

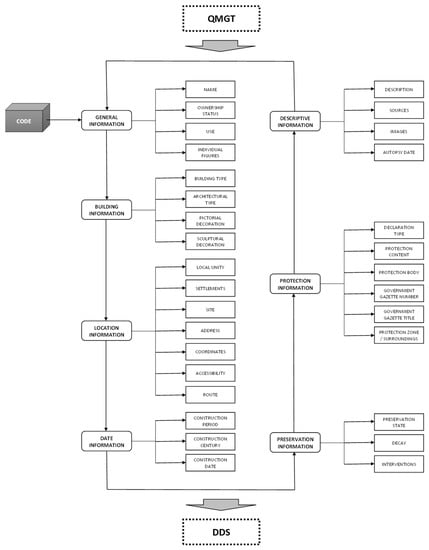

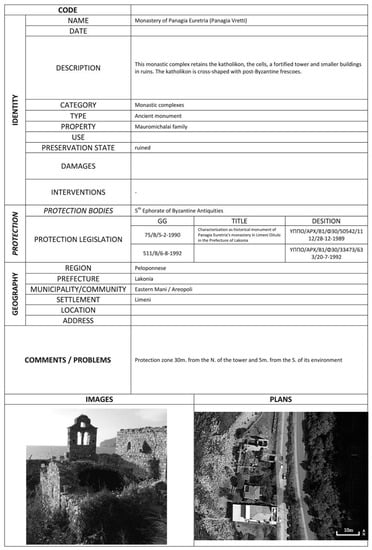

The classification for the buildings was based on architectural indicators, generated by the unique social organization dominating in Eastern Mani along with the particular geomorphology of the landscape. The architectural indicators included in QMGT used structural methods, chronological periods, and the architectural typology found in both the fortified facilities and religious temples located in the region. More specifically, the corresponding indicators for the classification of information with reference to monuments are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The flowchart presenting the indicators for the classification of information with reference to monuments.

2.2.3. Documentation Data Sheets

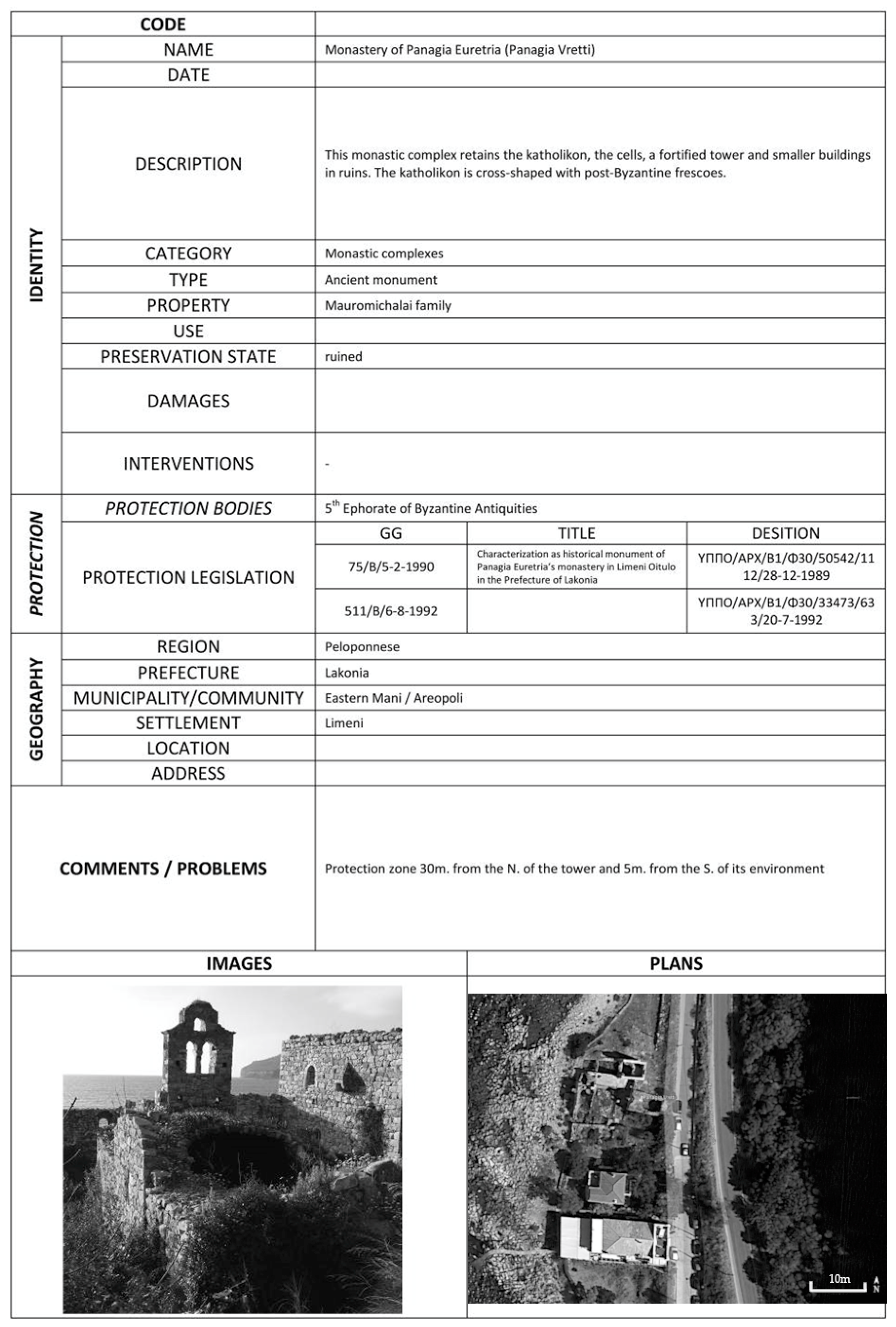

The data obtained during investigation process was recorded and classified in documentation data sheets (DDSs). DDSs were completed for each cultural and natural component of the landscape: monuments, archaeological and historical sites, settlements, existing hiking trails, museums, interesting buildings, and natural resources—that is, tangible heritage assets. The DDS structure was based on the indicators and domains defined in the QMGT and the category of interest. In general, information was classified into fields for the identification of the element, its typology/category based on the QMGT terminology, and protection framework and location, accompanied by a field for additional observations and/or problems. In the first field, a unique code was noted for the identification of each recorded subject. Taking a monument as an example, the fields of interest in the corresponding data sheet referred to (a) the name, date of origin, description, declaration type, property, use, preservation state, decay, and interventions for its identification; (b) the protection bodies, decision code, and title and description for the description of its protection framework; (c) the region, municipality, settlement, position, and address to define the monument’s location; and (d) spatial or historical data to determine relationships among the different elements of the CL. Other than descriptive data, spatial and raster data were also recorded in the DDSs: the exact location of each element and detailed photographic documentation were recorded in special fields at the end of each DDS (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Figure 4.

The representative DDS for the monument of Panagia Vretti’s church in Limeni.

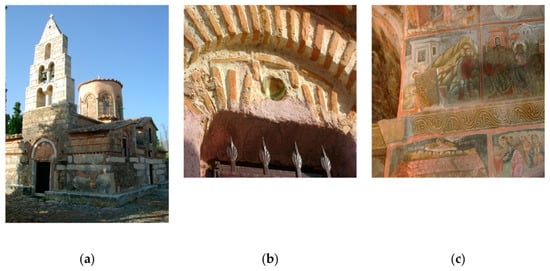

Figure 5.

Detailed photographic documentation of the church of Taxiarches in Charouda: (a) perspective view of the monument, (b) exterior decoration, and (c) interior decoration.

With reference to the spatial data recorded in the DDSs, initially, a draft geolocation of each element using Google Earth background emerged from the investigation process that preceded the first visit to the region. Such a procedure involved a small amount of and only the most recognizable monuments. In most cases, the spatial data were inaccurate, either due to doubtful co-ordinates, or because they were only descriptive and in relation to another monument. During field work, the exact location of each subject was recorded in the appropriate category in DDSs.

Within the process of data classification in DDSs and field work, additional monuments and buildings that are not listed by the Greek Ministry of Culture as independent buildings were identified, recorded, documented, and geo-referenced. These were mostly small-scaled churches that, due to their antiquity, are considered monuments and historical evidence, based on the national archaeological law. A proportion of these monuments were in ruins, preserving only part of their masonry, such as Panagia in Diporo (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The church of Panagia in Diporo; the roof of the church has collapsed.

3. Results

3.1. Current State Presentation

The recording of TCH and the rich traditions in the study area during the investigation process set the conditions and provided the corresponding data for tangible and intangible cultural heritage classification, assessment, and correlation, in order to develop a strategic plan for the sustainable development of the region under study. As mentioned in the Methodology section, a geographic information system (GIS) was used as a tool for the management and analysis of data recorded and classified in DDSs. The system’s attribute data consisted of the relational databases. The database structure followed the fields of the DDSs and the terms, directions, and instructions of the QMGT. Spatial data consisted of the base maps created from digitizing historic and spatial information: the digitized points of interest (monuments, etc.) were added to the base map and they were subsequently linked to the corresponding descriptive data on the databases, based on the unique code on the DDS. As a result, thematic maps of the current state were elaborated per element of interest and per different type, field, and subfield of the unified database, or in combination. The management and analysis procedures in GIS followed the two working planes of the proposed methodology: at the regional level, thematic maps presented the points of interest in relation to the wider area under investigation, whereas, at the more detailed level, the points of interest were presented in relation to the settlement in which they are located.

An initial unified thematic map for the preservation of the current state of the study area is elaborated, merging all the monuments (points), museums (points), settlements (points), protection areas (polygonal), and hiking routes (linear), the wider road network (linear), as well as the administrative local units (polygonal), which are included in the wider administrative and coastal national boundaries. This map serves as the base map for the specific current state maps, with reference to a specific reference field.

3.1.1. Tangible Cultural Heritage (TCH)

3.1.1.1. Presentation of Monuments

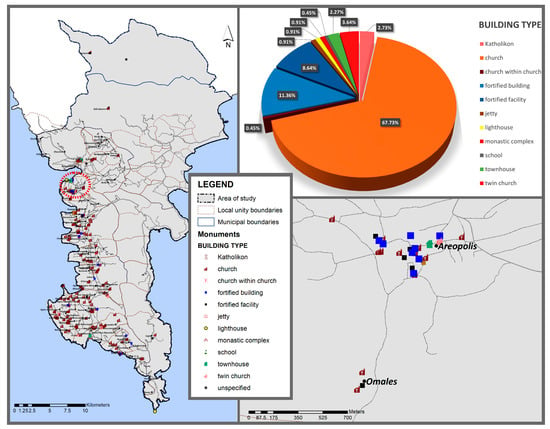

The elaborated thematic maps of the current state for the monuments present the data recorded in the DDSs, in relation to the selected reference field, for a total of 220 monuments. In addition, GIS analysis procedures between the different levels of current state information resulted in the classification and assessment of the monuments according to the parameters set in DDS recording fields: building type/initial use, architectural type, construction period, and preservation state/accessibility.

With reference to the main monument categories (Figure 7), the elaborated thematic map shows that religious structures clearly outweigh fortified facilities: indeed, Eastern Mani’s landscape is scattered with (mainly) small churches, both as individual structures, or as part of the fortified complexes of powerful clans. More specifically, 166 monuments out of 220, which is a percentage of 75.46%, are buildings that are dedicated to religious uses (such as churches or monastic complexes), whereas only 44 monuments, a percentage of 20%, belongs to the type of fortified building/facility. Other types to be found, but in a very limited number, are jetties, schools, and townhouses. This predominance of religious buildings is also evident in the corresponding thematic map of the original use of the monuments and describes the expression of the Maniots’ social life through religion, as well as the strong religious identity of the landscape.

Figure 7.

Thematic map of the current state showing the main monument categories; zoom of the red dotted area: distribution of the monument categories in the traditional settlements of Limeni, Areopolis, and Omales.

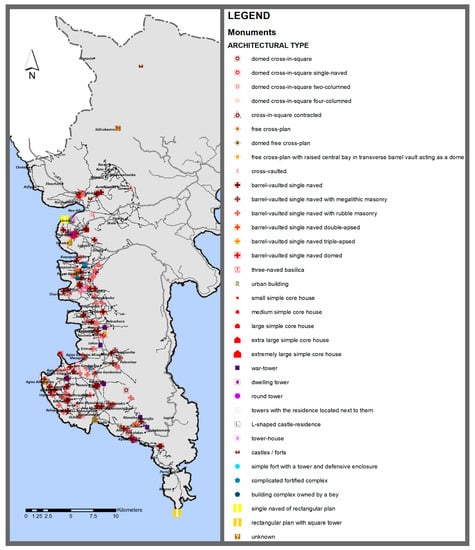

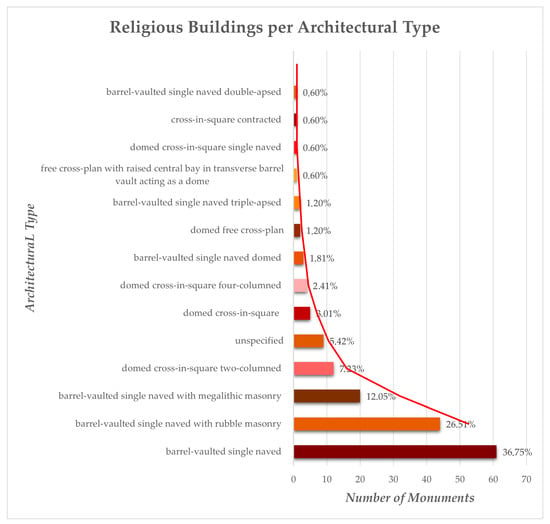

Following a further analysis of the prevailing architecture in Mani’s landscape, the monuments of the two main monument categories (ecclesiastical buildings and fortified buildings/facilities) are classified on the basis of their architectural type (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Thematic map of the current state showing the architectural type of the monuments.

The majority of the buildings in the first category (religious buildings) are simple structured, small-scaled churches scattered in Eastern Mani’s landscape (Figure 9). A total of 131 churches, that is, 78.92% of the ecclesiastical buildings, belong to the type of barrel-vaulted single-naved church with several variations: double-apsed, triple-apsed, domed, with megalithic masonry, or with rubble masonry. The prevailing construction of the barrel-vaulted single-naved type is rubble masonry churches, followed by megalithic masonry churches (Figure 10). These single-naved churches built with large stones without mortar constitute, according to Bouras [35], the indigenous type of Mani’s ecclesiastical architecture, and date from the Early Byzantine period. Another type of church that is often found is the domed cross-in-square type. In total, 22 churches of this type are presented in the thematic map of the current state showing the architectural type of the monuments, of which 12 were two-columned, 4 four-columned, and 1 single-naved. The remaining records of monuments of religious character include 1 cross-in-square contracted type church, 2 cross-vaulted type churches, 3 three-naved basilica type churches, and a total of 3 churches of free cross-plan, of which 2 are domed and 1 with a raised central bay in a transverse barrel vault acting as a dome. The total number of entries in the category of ecclesiastical buildings also include the number of churches whose architectural type could not be identified due to their state of preservation.

Figure 9.

The elaborated chart presenting the frequency of religious buildings based on their archi-tectural type.

Figure 10.

(a) The church of Agioi Asomatoi in Keria settlement as a typical example of a barrel-vaulted single-naved type church with megalithic masonry, and (b) the church of Agios Georgios (Stefanopoulianon) in Itilo as a typical example of a barrel-vaulted single-naved type church with rubble masonry.

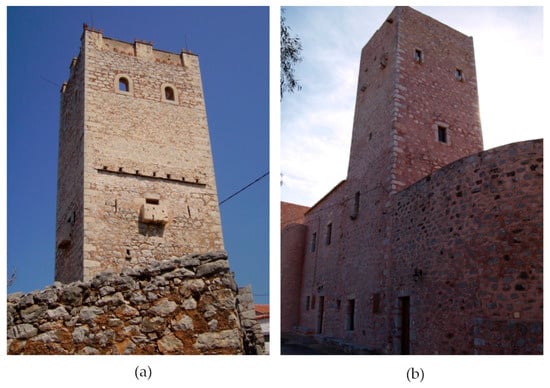

In the category of fortified buildings (Figure 11), there are two large simple core house, seven post-revolutionary war towers, five dwelling towers, four towers with the residence located next to them, one L-shaped castle residence, and six tower houses. Similarly, in the category of fortified facilities, two castles/forts, eleven complicated fortified complexes, and two building complexes of a clan are presented.

Figure 11.

Two representative fortified facilities in Eastern Mani: (a) Mparelakos Tower in Areopolis, and (b) Arapakis Tower in Charia. The typology and morphology of the towers follow the dictates of their use and fortified character: the floor plan is of limited area, almost square, with a height that gradually increases, whereas the elevations are simple with small openings (especially on the highest floors). The construction resulted in a single-pitched or two-pitched roof, while the lowest level was roofed with a stone-built arch. The communication between the floors was through a trapdoor. The house building followed tower construction within common axis.

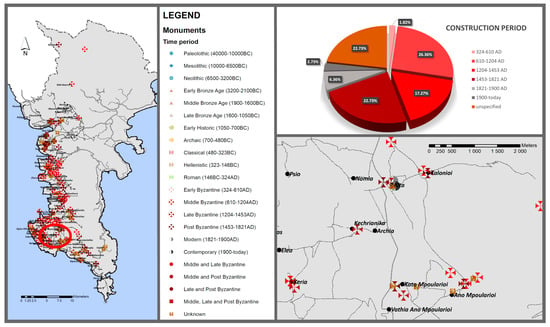

With reference to the chronological period of the monument’s construction (Figure 12), the majority belong to the Middle Byzantine period (58 monuments in total), followed by the monuments of the Post-Byzantine period (50 in number). A total of 38 monuments are dated during the Late Byzantine period, 14 in the period of 1821–1900, and 6 in the period after 1900, while 4 monuments correspond to the Early Byzantine period. A large number of monuments (50 in total) are not included in the above results as there is no available information on the period of their construction.

Figure 12.

Thematic map of the current state showing the chronological period of the monuments’ construction (left); and the distribution of the south-eastern settlements of the red dotted area in detail (right).

Comparing the thematic maps of the building type and the chronological period of construction, it is clear that the largest percentage of church buildings, 34.36%, was constructed during the Middle Byzantine period. This is followed by the Late Byzantine ecclesiastical monuments, at 22.70% and the Post-Byzantine monuments, at 17.18%. In the Post-Byzantine period, 56% of the fortified buildings were built, followed by 24% in the period of 1821–1900, and only 4% in the period after 1900, which was similar for the fortified complexes, where 46.67% was built in the Post-Byzantine period, with a following 20% in the period of 1821–1900. We have one monument of each category in both the Early Byzantine and the Late Byzantine period. Thus, it is evident that the construction activity in relation to ecclesiastical architecture was intense from the 6th to the 15th century, and continued, to a lesser extent, until the 19th century. On the contrary, fortified architecture followed the prevailing political and social conditions in the region. The reconstitution of the Greek state and the restoration of a central government led to the decline of social organization into clans and, consequently, to the prevalence of less solid–defensive and more urban architectural typologies.

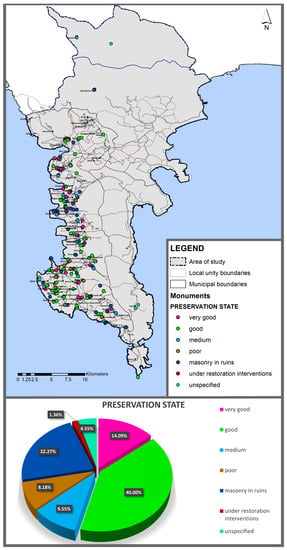

The monuments are also evaluated based on their preservation state and the decay on their masonry and environment (Figure 13). In terms of masonry decay, the majority of the monuments are in a good preservation state in a percentage of 40%. These monuments present simple surface decay. However, a large number of monuments, a percentage of 22.27%, are considered to be in ruins, as the largest part of the monument’s masonry has collapsed. This number is also linked to the corresponding number in the field of the current use of the monuments. In addition, 18 monuments are in a poor preservation state, with a part of their masonry damaged, and 21 in a medium preservation state, with extended surface decay. However, a significant number of monuments, 31 in total, are in a very good preservation state, due to recent restoration and maintenance works. Moreover, during the visits to the study area, 3 monuments were under restoration interventions.

Figure 13.

Thematic map of the preservation state of the monuments.

Overlapping procedures between the thematic maps of the main categories and the preservation state of the monuments, it emerged that the majority of the churches are maintained in good (67 monuments) and very good (18 monuments) condition, which is a total of 54.84% of the churches, compared to 22.58% where their masonry is in ruins and 7.74% where they are in a poor preservation state. The results for the preservation state of the fortified buildings seem to be more evenly distributed, as, of the total of the 25 records, 5 are in very good condition after restoration interventions, 7 in good condition, 3 in moderate condition, 4 in bad condition, and 5 were considered to be in ruins, while 1 was under restoration interventions. The fortified complexes present similar results: of the 15 in total, 6 were considered to be in very good condition, 2 in good condition, 6 in ruins, while one was under restoration interventions. These results are mainly affected by the ownership status of the monuments: most of the ecclesiastical buildings are public, whereas, on the contrary, the restoration of the fortified buildings is subject to private initiative.

The analysis of the status of each monument’s surrounding area provides the accessibility criteria: with regard to access to the majority of monuments, approximately 59.55% is recorded as easy. This means that most of the monuments are accessible via an asphalt road. A rural dirt road of moderate roughness leads to a total of 9.09% of monuments with moderate accessibility, while a percentage of 17.27% of the monuments is approached via a dirt road of intense roughness, increasing the degree of difficulty in their access. Finally, access is extremely difficult for 20 monuments.

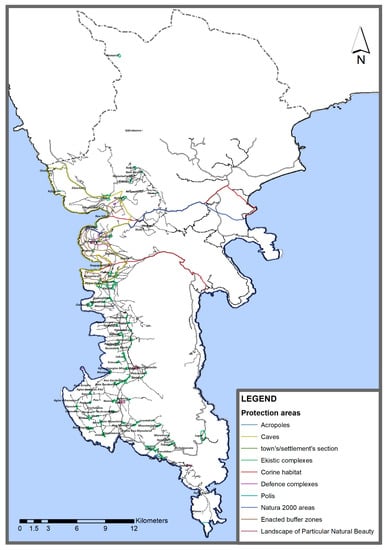

3.1.1.2. Presentation of Protected Areas (PAs)

Similar to monuments, thematic maps of the current state are elaborated for the protected areas, with reference to the different fields of the database. GIS management and analysis tools are used in order to draw useful results about the formation of the protected areas in their current state. These results are also investigated in terms of area measurements, so as to have a complete spatial understanding and representation of the data.

Based on the information obtained by the investigation procedure and the DDSs, the protected areas are classified into main categories which include both areas of cultural and environmental value (Figure 14). The prevailing category, as presented in the corresponding thematic map of the current state, is the ekistics complexes, at a rate of 75.64% and with a total surface of 3,273,881.06 m2. This result is also justified by the numerous traditional settlements that are listed in the region. Eastern Mani is characterized by a dense residential network. Indeed, the landscape is fragmented by many small settlements under a dominant military/defensive organization. The residential planning and building organization follow the distinct social organization of the Maniots into clans: the core of a settlement consisted of typical residential units of a powerful clan. This core was expanded with additional buildings and facilities of less powerful clans, thus organizing neighborhoods of related branches. Within this context, smaller or larger and unified settlements were formed through the years. Although, numerically, the ekistics complexes are outnumbered, their total surface area is rather low, due to the small extent of the settlements: as presented in the thematic map of the protected area categories, the surface of the ekistics complexes varies from 3406.25 to 490,816.28 m2.

Figure 14.

Thematic map of the current state showing the main categories of the protected areas.

On the contrary, regarding areas of environmental value, it is shown that caves numerically reach a percentage of 5.13% of the protected areas, but with a total surface area of 33,209,814.49 m2. In addition, the buffer zones enacted by the Greek government are recorded at a rate of 3.85% and a total area of 5,616,679.04 m2, and Natura 2000 areas with the Landscapes of Particular Natural Beauty at a rate of 5.13%, with a total coverage of 1,453,358.63 m2.

Regarding the dating of the protected areas with cultural value, a percentage of 39.74% date back to the Middle Byzantine period, covering a total area of 4,202,437.09 m2, followed by the areas of the Post-Byzantine period, at a percentage of 30.77% and an area of 818,259.94 m2, and the Late Byzantine period, at a percentage of 12.82% and an area of 259,265.51 m2. Additionally, 10.26% of the protected areas date back to the Palaeolithic period, covering 878,365,001.62 m2. Finally, a percentage of 1.28% is dated to the Early Byzantine period (covering 80,653.21 m2), the Late Bronze Age (covering 218,545.15 m2), the Neolithic period (covering 724,372.06 m2), and the Roman period (covering 53,250.32 m2), with a total surface area of 1,002,731.09 m2 for which the exact date cannot be specified.

3.1.2. Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH)

During the investigation process, the main social aspects of the daily life of Maniots were studied and defined, resulting in the recording, classification, analysis, and assessment of the ICH of the CL. The ICH assets were evaluated based on their interrelation with TCH elements, resulting from investigation procedures and data analysis procedures among the different levels of information in the DDSs and the current state thematic maps for the monuments/protected areas. The main ICH features that emerged from these procedures are presented below:

- Social/family structure/organization system—clans into fortified complexes:

The resistance to any form of central government, especially during the Ottoman occupation, forced Maniots to set their own rules of law at a local level, guided by tradition and the respective socio-economic conditions. The social structure in Eastern Mani was essentially a set of independent and free clans, based on blood relations. At the core of the peculiar social structure was the armed clan: the power of each clan was determined by the number of its male members (those who could carry weapons). The clans of Eastern Mani were characterized by cohesion, solidarity, equality among their members, and democratic processes regarding their internal organization. At a political level, a clan’s cohesion is expressed through the yerontiki: the council of married men of the clan, which exercised political and judicial power. This unique social cohesion was imprinted in the spatial organization of the settlements and in architecture: the whole structure of the settlements and the constructions supported the branching of a family tree, as well as the spread of members around a central nucleus, that of the most powerful clan. The main expression of the power of a clan would be its war tower: a very powerful clan with many branches might have had numerous war towers, one for each strong branch. The houses of the members were built around the tower, along with the family churches and the cemeteries, formatting a fortified complex as an expression of a settlement for each clan, the xemoni.

- The concept of social justice and the defensive organization in fortified complexes:

In the context of the fierce struggles for survival and for the establishment of power and dominance among the different clans, a kind of self-judgment under the custom of gdikiomos (synonym to feud or vendetta, in the folk speech of Mani) was developed: the imposition of punishment in response to any insult to the honor of one of the family members. This institution concerned not only the entire affected clan, but also the perpetrator’s family, as the punishment could be imposed on any of its members. The method of the punishment was decided by the family’s council, with the participation of all male members. In the case of gdikiomos, the construction of fortified facilities and war towers enhanced the defense and the armed organization of the clan: as the war was declared by the lead member of the clan, the two rival sides took their places in the defensive towers of each clan and the civilian population hid or moved away.

- Deep religious conscience:

The clan’s cohesion and spatial organization were also expressed through religious structures: each clan had only one church, devoted to the patron saint of the clan, and one cemetery, which were built next to the residences of the family members, representing the unbroken continuity among the living members of the clan and their dead ancestors. Only after the first quarter of the 19th century were parish churches built, larger in size than family churches. All Maniots participated in religious festivals, which were of great importance for the unity of the inhabitants of a village.

- Death ritual:

The most important religious event in Mani were death rituals. The dead was honored by improvised original mournful eight-syllable funeral poem-songs (miroloi) sung by the women of the clan: tender words were used for those who died of natural causes and harsh words for those whose death requires revenge. This was the main form of song and folk poetry, which was passed down from generation to generation. Death rituals were imprinted mainly in the clan’s cemetery and the poem-songs can find their expression through the cemetery churches.

- Gastronomy:

Mani is a barren land, arid, with minimal production. The traditional cooking was simple, dependent on the few products that the place produced: lupines (bitter legumes), broad beans and lentils, fish (local fishing), meat (mainly pork), honey, and, above all, olive oil. The traditional recipes of Mani cuisine are still used today and are a special feature of the region. This traditional gastronomy is mainly imprinted in the scarce arable land of traditional products such as oranges and olive trees, as well as in the remaining small industrial buildings, for example, for oil production.

In summary, the continuous and inextricable relation between the TCH and the ICH of the area under study is presented in the following table (Table 1).

Table 1.

The interrelation of TCH and ICH in Eastern Mani.

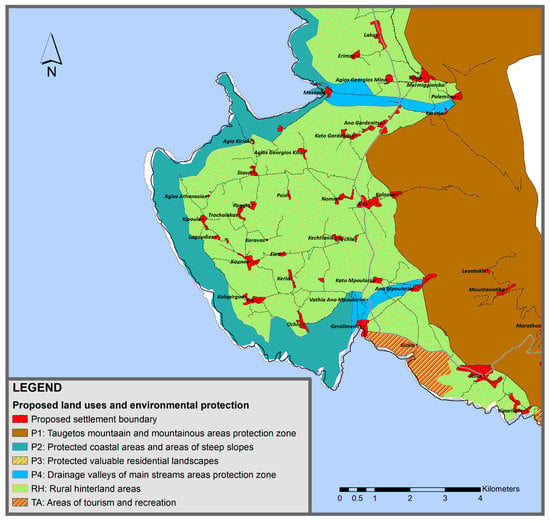

3.1.3. Assessment Analysis of the Current State

Referring to the development plans drawn up for the study area, a thematic map is elaborated considering the proposals of the existing spatial plan. These proposals consist of the delineation of settlements, and protected areas and areas of special interest.

Prior to any decision making for the protection and highlighting of the area under study, a number of queries emerging from documentation processes need to be taken into consideration: what are the problems in the study area which should be approached locally and regionally, and what parameters should be taken into account and be satisfied in order to achieve the goal of sustainable development? What are the special features of the area that will be the tools and will offer the right conditions to achieve this goal? Which of these components are considered urgent/immediate and which indirectly treatable?

In 2013, the former Municipality of Itilo elaborated an open city spatial and residential organization plan aiming at the configuration of alternative perspectives for the spatial development of the region, within the general directions of the national spatial plans. In this spatial framework, the existing state of the areas under study and the particular socio-cultural conditions of the wider landscape were analyzed and evaluated, resulting in the development of a structural plan for the spatial organization of the region. With reference to spatial analysis, the areas of Mani were categorized into the coastal, rural hinterland, and mountainous areas. Subsequently, the development planning requirements were defined separately for each category. Figure 15 shows the elaborated open city spatial and residential organization plan in GIS by the authors.

Figure 15.

The elaborated open city spatial and residential organization plan in GIS by the authors.

The directions and analysis of the open city spatial and residential organization plan and the current state analysis presented above resulted in the following classification of the negative effects and prospects, and the resources/positive features of the region that can be utilized in the context of a comprehensive strategic planning for development. To this aim, GIS overlay analysis procedures have been used between the thematic maps of the current state and the thematic maps of the development plans (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15) [21].

More specifically, the negative growth indicators recorded in the study area are:

- The degradation of the built environment (abandonment of residential complexes, historic buildings, incompatible constructions, etc.);

- The degradation of cultural resources (unorganized and unguarded areas of protection, monuments without protection status, traditional settlements without defined boundaries, etc.);

- The degradation of the natural environment (extensive fires, outbreaks of tourist exploitation, etc.);

- The neglection of tourist resources (unorganized cultural sites, unorganized hiking routes, etc.);

- The deterioration of social cohesion (migration/unemployment, population decrease, basic deficiencies in social infrastructure, such as health and education, etc.);

- The unbalanced spatial development (north–south of Eastern Mani)

In contrast, the resources/development factors to be exploited for sustainable development at the local and regional level, that are recorded during the stages of the current state analysis and the conclusions from the development frameworks, are:

- The rich stock of TCH elements (historical and traditional building shells, integrated traditional housing units, etc.);

- The rich stock of ICH elements (customs, traditions, folklore, etc.);

- The rich fauna and flora;

- The existing hiking routes and trails;

- The special geomorphological characteristics (combination of coastal areas, areas with steep slopes and mountains, etc.);

- Agricultural lands with traditional specialized crops (olive trees);

- Local gastronomy and famous products (olives, honey, etc.).

3.2. New Proposals Presentation

The information resulting from the current state (Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14) and spatial planning thematic maps (Figure 15) led to the elaboration of the thematic maps of the new proposals with the use of GIS analysis and geoprocessing processes: the descriptive data from the current status information levels and spatial plans are integrated into new thematic levels, thus contributing to strategic planning for the protection and highlighting of the area of Mani’s peninsula.

However, apart from the different scale, the proposed interventions are also classified into medium- and long-term actions, according to their direct or indirect implementation. The process of monuments’/protected areas’ current state evaluation set the criteria for the implementation stages of the proposals for the protection and promotion of the area under study.

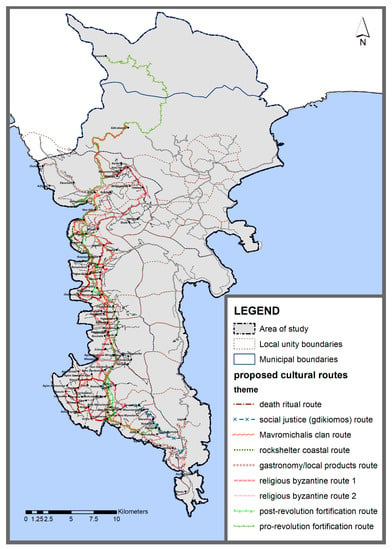

3.2.1. Proposed Cultural Routes

The proposed development of a CR network in Eastern Mani aims at promoting the cultural and natural resources and, consequently, at the establishment of alternative tourism activities in the region. The main categories of the ICH set the corresponding themes for the proposed CRs. The monuments/protected areas to form the routes have emerged from the analysis/evaluation procedures based on the following criteria: (a) the interrelation of the monument/protected area with the main ICH categories, and (b) the preservation state and accessibility of the monument/protected area. The monuments with a poor preservation state or with masonry in ruins, and/or with difficult access, can only be part of the provisioned extended sections of the routes, which are included in the long-term proposals, i.e., after the necessary restoration work of the monuments and their surrounding areas.

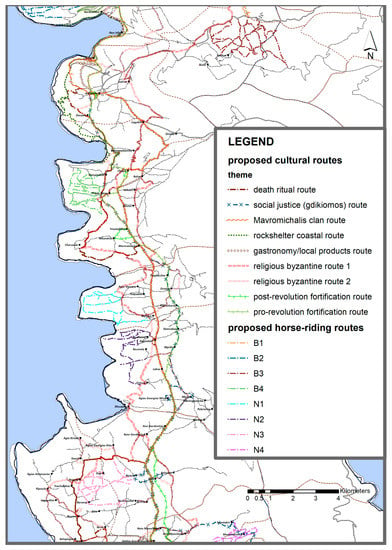

The proposed thematic CRs are presented in Figure 16, and they are described below:

Figure 16.

Thematic map of the proposed cultural route network.

- Death ritual—funeral song CR:

For the design of the thematic CR presenting death rituals in Eastern Mani, the churches located in the cemetery of the settlements were selected (Figure 17). Each settlement has its cemetery linked to the clan that created the ekistics core of the settlement. The main proposed route was designed including all churches in a good preservation state, and with easy access. A provision for the extension of the route in the future is also planned, so as to include the cemetery churches of poor preservation state and difficult access, after all the necessary restoration interventions. The resulting proposed route is linear with a circular section, in order to unify the temples in the southern part of Eastern Mani.

Figure 17.

The cemetery churches of (a) Metamorfosi Sotiros in Dri, and (b) Agios Nikolaos in Mpriki.

- Gdikiomos CR:

For the design of the thematic CR presenting the military character of the social and architectural structure of Eastern Mani, with reference to the ritual of gdikiomos, the selected monuments/protected areas should meet the following conditions: the original use being defense and the architectural type being either a war tower or fortified complex. Through the analysis procedures of the thematic maps of the existing state, a total of 10 monuments and 6 settlements that are famous for their war towers, such as Koita, are selected. The resulting proposed route is linear, crossing almost the entire study area: from Areopolis to Vathia (Figure 18).

Figure 18.

The fortified character of Eastern Mani is captured both in settlement organization and in architecture: (a) Vathia settlement, and (b) Sklavounakos Tower in Pirgos Dirou.

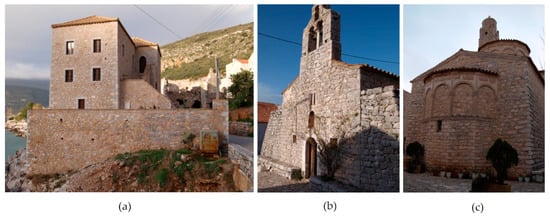

- Social organization—clans CR:

Aiming at the presentation/highlighting of Mani’s social organization into clans, CRs of local interest and on a settlement scale are also proposed: their themes present famous and dominant clans of Eastern Mani. As an example, a CR for the Mavromichalis family is proposed, not only due to the numerous and important monuments (from imposed temples, such as Taxiarches cathedral in Areopolis, to fortified buildings and complexes), but also due to the key role of this family on the wider socioeconomic and historical agitators in the area during the Greek Independence War, as well as during the first decades of the newly established Greek state (Figure 19). The purpose of the route is the narration of the Mavromichalis family story, which has its origins in the settlement of Alika, and is connected to numerous and important historic complexes and buildings in Areopoli and Limeni. Similar routes could be designed in a later phase of the study, in other main settlements of strong clans, with their smaller ekistic organizations (epineia and xemonia), such as Itilo of Stefanopouliani, or in Koita (Niklianiko).

Figure 19.

The imprint of Mavromichalis family in Eastern Mani’s landscape: (a) Mavromichalis settlement in Limeni, (b) Agios Ioannis (St. John) of Mavromichalis family church in Areopolis, and (c) Taxiarches church in Areopolis.

- Special geomorphological formations CR:

Another important element that determines the landscape of the study area is the special geomorphological configuration of the soil, with steep slopes that end in a narrow strip of coastal area. In the southern part of the area, the visitor can tour this wild landscape through the existing hiking routes and, at the same time, visit the man-made creations at the most extreme points of the coastline (such as the church of Panagia Agitria near the settlement of Agia Kiriaki). In the northern part, it is this peculiar geomorphology of the coastline that creates the well-known cavernous formations, among which the caves of Diros belong. It is, therefore, proposed that we draw a CR on the subject of rocky terrain: the route is linear and connects the entire coastal area from the Kalamakia cave near Karavostasi, to the caves in Diros, ending at the archaeological museum presenting the archaeological findings of the area.

- Gastronomy CR:

Within the thematic unit of the CR based on the customs/traditions and the special features of the landscape, a thematic route on the local products and gastronomy is proposed. Maniots’ local diet was identified during the investigation process based on the suggestions of the local population and the local stakeholders in the field of food services. The building of the old primary school in Germa was selected as the starting point of the route, where it is proposed to be used as an exhibition center of local products and a seminar room for the preparation of local dishes, in order to develop gastronomic tourism in the area. Along the way, the visitor will have substantial contact with local production and gastronomy by crossing olive groves, beekeeping areas, buildings for the processing and commercialization of raw materials, and also places where he can taste the delicacies of the area. For this purpose, coastal settlements were selected (such as Karavostasi and Limeni) known for their fish taverns, as well as the surviving traditional olive mills in Areopoli (such as Kalapotharakou, which also functions as a museum) and Lagia, along with the various restaurants for traditional food, and, also, the traditional olive mill in the settlement of Vathia (which is abandoned, but its equipment is preserved in good condition), as well as the building complex of Kyrimi in Gerolimenas, from where local products were traded to other regions and countries. At a later stage, this route could be connected to the olive museum in Sparta, and to other points of gastronomic and primary production interest in the wider area.

- Deep religious conscience CR:

Religious CRs are designed, with an emphasis on the depiction of the Byzantine presence and its respective influences on the architectural expression in Eastern Mani. Thus, routes were created for the integration of Byzantine churches, according to their chronology: (a) Early Byzantine and Middle Byzantine, and (b) Late Byzantine and Post-Byzantine period (Figure 20).

Figure 20.

(a) The Early Byzantine barrel-vaulted single-naved Sotiras church with megalithic masonry in Charouda, and (b) the Post-Byzantine barrel-vaulted single-naved Taxiarhes church in Drialos.

In the first thematic section (CR of the Early and Middle Byzantine period), a total of 18 monuments have been highlighted. These monuments are unified through a linear route with two circular sections, extending from Germa in the north up to Gerolimenas in the south. The remaining monuments (of poor preservation state/difficult access) can be added in order to form the perspective of extending the route: to the south up to Kiparissos, but also to the west, up to Ano Poula and Tigani.

For the second thematic unit (CR of the Late Byzantine and Post-Byzantine period), the evaluation procedures of the religious monuments led to the integration of 42 monuments in the first phase, while another 22 monuments will be integrated at a later stage, when their preservation state/accessibility will be improved. The main route is linear with circular sections: it extends from Kelefa in the north to Vathia in the south, including a significant number of monuments in its circular section within the municipalities of Ano Boularioi, Kounos, Gerolimenas, and Koita.

- Μilitary and defense character of the social and architectural structure CR:

Besides the proposed CR for the gdikiomos ritual, routes are also designed, regarding the fortified buildings/complexes, based on their construction period and their categorization into pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary, that is, before and after the Greek Independence War in 1821 (Figure 21). The proposed route of pre-revolutionary fortified architecture is linear and it initially extends from Limeni to Sichalasmata, connecting a total of 11 monuments. Many more will be added in a later phase, with the extension of the proposed route to the north (Itilo), west (Stavri), and south (Kiparissos). In essence, the post-revolutionary fortified route is part of the first (pre-revolutionary), starting from Areopolis and extending mostly to the south (Gerolimenas). In its original design, it integrates seven monuments, to which two more will be added at a later stage.

Figure 21.

(a) The pre-revolutionary tower of Nikolinakos family in Vamvakas, and (b) the post-revolutionary tower house of Kapetanakis in Areopoli. Pre-revolutionary towers were tall, stone-built structures with rectangular floor plan of limited surface area and limited wall openings. After the revolution of 1821 and the constitution of the Greek state, in order to avoid war conflicts among Mani’s clans, the construction of war towers was forbidden. The type of tower house prevailed, as a combined type of the earlier war tower with the use of residence.

In addition to the network of CRs resulting from the interconnection of intangible and tangible cultural heritage, and landscape physiognomy, a network of horse-riding routes is also proposed, aiming at strengthening the tourist development of the region, through mild forms of tourism, integrated into the uniqueness of the landscape (Figure 22). The proposed horse-riding routes emerged from the traditions discussed during the interview process with the local population and stakeholders, considering Maniots’ everyday life and common activities. The organization of horse-riding routes is selected based on the following parameters: (a) horses have been historically and traditionally used for transportation in Eastern Mani, throughout its history, (b) the use of horses in Mani was a point of reference for the daily life of the inhabitants both in agricultural production and military/defense activities, (c) horses are widely used even today in the area, whilst the horse-riding club located in Areopoli participates in all the important commemorative events organized by the Municipality, and (d) the organization of such routes does not require any intervention that would alter the character of the area; on the contrary, the rugged landscape and the existing path network reinforce such activities.

Figure 22.

Thematic map of the proposed horse-riding routes network in relation to the proposed CR network.

For the location of the horse-riding network, areas that meet the following criteria were searched: (a) areas with settlements which, during the analysis of the existing state, are characterized as being sparsely populated or abandoned, (b) areas with dense existing paths and a cobbled street network, (c) areas showing terrain and vegetation diversity, and (d) areas that are not included in the proposed thematic network of CRs, but can be linked to it. In total, eight areas emerged for the development of horse-riding routes:

- The first network of horse-riding routes (B1) is designed in the local units of Karea and Germa, at the northern end of the study area, and extends to the north of the settlement of Avramianika, including the settlements of Krioneri, Mpoutselianika, Karea, and Kato Karea, ending at the foothills of the Taigetos mountain. To the south, it reaches as far as Germa, where it connects with the proposed gastronomy route, and the national road of Githio–Areopolis. It occupies not only agricultural areas of local importance, but also areas with sclerophyllous vegetation and natural grasslands. The route is quite long, with many branches and being of moderate difficulty, as it is mainly mountainous. It is designed mostly on the existing road network (secondary asphalt road), but also on existing dirt roads to serve agricultural operations;

- The second network (B2) occupies the north-west end of the Mani Peninsula and extends from Itilo to the Arfigia settlement in the west, passing through natural grasslands and olive groves. This horse-riding network is developed in existing rural dirt roads and local land openings. The area is characterized as semi-mountainous without steep slopes, offering a unique view of the Messinian Gulf. It is also an extended route, with several branches;

- The third network (B3) extends from the village of Vachos and towards the north, up to the Githiou–Areopolis asphalt road, with which it intersects at several points. At one of these points, it is also connected to the B1 network, and also to the proposed Byzantine ecclesiastical CR. This relatively large area occupied by the B3 network of horse-riding routes includes lowland and mountainous areas, thus increasing its level of difficulty. It is mainly designed on the existing asphalt roads, with local openings of dirt roads in the branches, while it extends mainly on land with significant agricultural land, and, to a lesser extent, on land with fruit trees and sclerophyllous vegetation;

- The last network of the northern section (B4) extends to the western end of the peninsula, occupying the entire plateau west of Pirgos Dirou, in mainly olive groves, with small sections of natural grasslands. The routes are easy and existing terrain maps were used for their design. In its western parts, it also offers a unique view towards the Messinian Gulf. It is connected to the proposed CR for the ritual of gdikiomos, to the early Byzantine ecclesiastical architecture route, and to the death rituals CR;

- Towards the south, the first network (N1) extends to the western end of the peninsula, west of the settlements of Agia Varvara and Tsopaka. It occupies a medium-sized flat area without many branches, while it is mainly designed on existing paths. It extends mainly in natural grasslands, with smaller sections of olive groves and land with sclerophyllous vegetation. At the eastern end, it connects to the proposed CR for early Byzantine ecclesiastical architecture;

- The proposed N2 network extends west of the settlements of Kouloumi, Koutrela, and Erimos. The terrain is mainly flat, with the exception of a slope in the north, while the network does not show many branches, mainly designed in existing paths. It extends in natural grasslands, but also in significant agricultural area. It is also linked to the proposed CR for early Byzantine ecclesiastical architecture;

- The N3 network extends south of the Tigani peninsula, and is surrounded by the settlements of Psio, Pagia, Karava, and Nomia. It extends in the largest area, which is basically lowland, with olive groves and non-irrigated arable land. It follows the existing asphalt roads, rural dirt roads, and paths, forming several branches. It is connected to the proposed CR of ecclesiastical Byzantine architecture and death ritual, and the gdikiomos route;

- Finally, the N4 network occupies the mountainous area south of the Leontaki settlement and west of the Mountanistika settlement, a land characterized as burnt. It is the smallest network in terms of area, and it is connected to the proposed CR of the gdikiomos.

3.2.2. Proposed Protection/Buffer Zones

The proposed Protection Zones concerned the preservation and promotion of the two aspects of the CL under study: its cultural and natural context. The design process of the proposed Protection Zones took into consideration the negative aspects that emerged from investigation phase and current state analysis results.

With reference to CH protection:

- There is no spatial background for the implementation of the legislative framework for the protection of CH. Therefore, the need for the spatial identification and demarcation of listed monuments, protected areas, and folklore/traditional elements emerged as a priority;

- The context of the current legislative framework for the protection of CH does not include all the monuments and sites of historical and archaeological value, as well as the elements of ICH in the study area. Therefore, a secondary axis of priority is the incorporation of the total region of Eastern Mani in the legislative framework as a single protected entity in terms of strategic planning for its preservation and protection. Within this context, the characterization as traditional of the unlisted settlements is included, such as Gerolimenas, which is under intense pressure due to tourism development and exploitation.

With reference to natural heritage protection, the proposed actions of the existing development plans for the organization of protected areas under special regulations of land use and construction in Eastern Mani have not been implemented. In addition, the existing development framework does not include actions for the protection of the rural inland, nor takes into consideration the possible danger of extreme changes and alterations of the landscape, such as catastrophic fires.

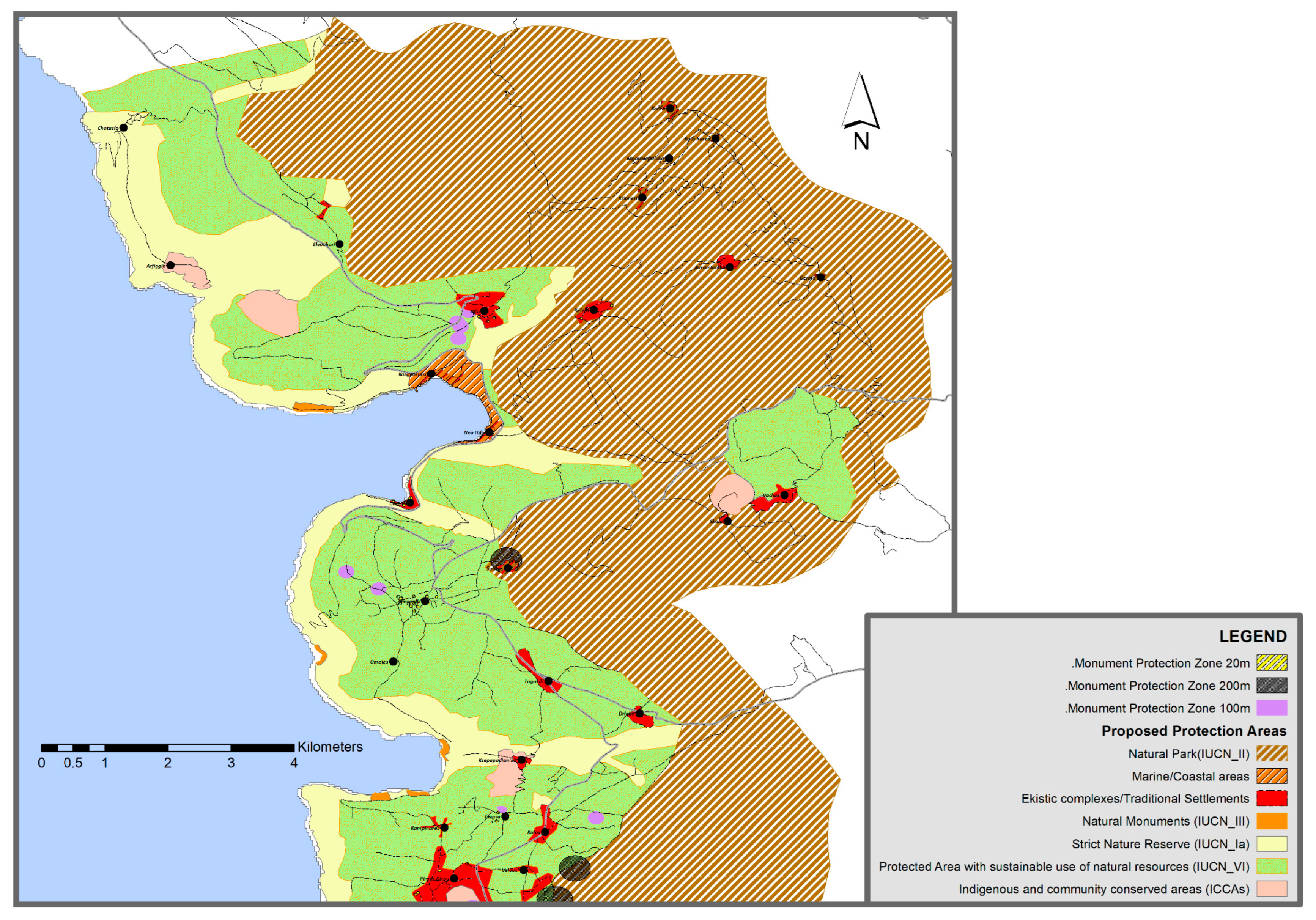

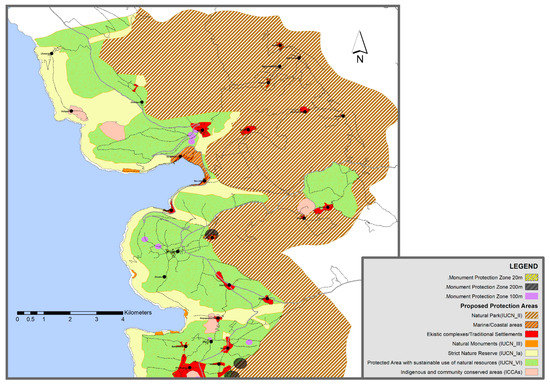

In order to address the significant lack of a regulatory framework for the environmental protection of the unique landscape in Eastern Mani, Protection Zones are proposed based on global guideless for the definition and registration of protection areas combined with the corresponding Greek regulations: protection zones and areas are defined, based on the IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) guidelines [36] and the regulations for zones that any structure is forbidden, or zones with restrictive building conditions, as defined within the Greek Archaeological Law (Figure 23):

Figure 23.

The presentation of the proposed protection zones/protected areas in the study area.

- Strict nature reserve (IUCN Category I):

According to the IUCN guidelines, these are strictly protected areas set aside to protect biodiversity and, also, possibly geological/geomorphologic features, where human visitation, use, and impacts are strictly controlled and limited to ensure the protection of the conservation values. The areas of Eastern Mani that are proposed to be included in this category are the coastal areas, which are characterized by cave formations, with the exception of coves that can be used for tourist development, as well as stream areas. With reference to the protection degree of this category, these areas are of Absolute Protection. They are used as Protection Zone A (any structure is forbidden);

- National park (IUCN Category II):

According to the IUCN guidelines, these are large natural or near-natural areas set aside to protect large-scale ecological processes, along with the complement of species and ecosystems characteristic of the area, which also provide a foundation for environmentally and culturally compatible, spiritual, scientific, educational, recreational, and visitor opportunities. The areas of Eastern Mani that are proposed to be included in this category are the mountainous areas, and are considered as Zones of Higher Protection with special regulations and building restrictions (building is allowed for the organization of mild tourist activities, compatible with the special characteristics of the area);

- Natural monument or feature (IUCN Category III):

According to the IUCN guidelines, these are protected areas set aside to protect a specific natural monument, which can be a landform, sea mount, submarine cavern, geological feature such as a cave, or even a living feature such as an ancient grove. They are generally quite small protected areas and often have high visitor value. The areas of Eastern Mani that are proposed to be included in this category are the individual areas of the caves in the bay of Oitylo and Pyrgo Dirou, and are considered as Zones of Maximum Protection. They are used as Protection Zone A (areas where construction is totally forbidden);

- Protected landscape (IUCN Category V):

According to the IUCN guidelines, these are protected areas where the interaction of people and nature over time has produced areas of distinct character with significant, ecological, biological, cultural, and scenic value, and where safeguarding the integrity of this interaction is vital to protecting and sustaining the area and its associated nature conservation and other values. The entire area of the peninsula of Laconian Mani, as a single united whole, is proposed to be included in this category;

- Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources (IUCN Category VI):

According to the IUCN guidelines, these are protected areas that conserve ecosystems and habitats together with associated cultural values and traditional natural resource management systems. They are generally large, with most of the area in a natural condition, where a proportion is under sustainable natural resource management and where low-level non-industrial use of natural resources compatible with nature conservation is seen as one of the main aims of the area. The areas of Eastern Mani that are proposed to be included in this category are rural areas and areas of cultivation of goods of local importance (such as olive groves). These areas are considered as High Protection Zones with special regulations and restrictions on building and land use;

- Indigenous and community conserved areas (ICCAs):

According to the IUCN guidelines, these are natural and/or transformed ecosystems, which contain significant biodiversity values and ecological services, and are voluntarily maintained by indigenous people and local communities, through customary law or other effective methods. The areas of Eastern Mani that are proposed to be included in this category are areas with abandoned settlements for tourism exploitation and development on sustainable terms, by the local authorities/communities. These areas are considered as High Protection Zones with special regulations and restrictions on building and land use. They are used as Protection Zone B with special regulations and building restrictions;

- Marine/Coastal zones:

The areas of Eastern Mani that are proposed to be included in this category are the areas of natural coves and coastlines, which are suitable for the development of mild tourism activities. They are considered as Zones of Moderate Protection with special regulations and restrictions on building and land uses;

- Traditional settlements:

All the residential complexes of the area under study are included in this category. They are considered as High Protection Zones with special regulations and restrictions on building and land use.

Further to the above, a major risk that was recorded in the area with an almost annual frequency is the risk of fire. To this scope, the management and analysis procedures of the existing state, and, more specifically, the recording of land uses, resulted in the selection of the areas of increased and immediate risk based on their location (mountainous areas or areas with steep slopes). For the fire protection of the most sensitive and vulnerable areas, the following zones were proposed: (a) an extended zone of mountainous areas, and (b) a secondary zone for the areas with a steep slope.

In addition, deforestation/vegetation clearing zones in a radius of (minimum) 3 m are proposed, so that the routes are clearly visible, in order to facilitate the passage of emergency vehicles, without altering the character of the area.

4. Discussion

Recently, the importance and the need to protect the CL as part of CH is being highlighted as a major issue by international bodies and organizations. As defined in the European Landscape Convention, the landscape’s character is the result of actions and interactions between natural processes and human activities: (a) it embraces a wide and complex assemblage of interrelated natural and cultural elements that remain as important evidence of the past and that establish the essential fabric for many monuments, archaeological and historic sites, or even entire regions, as well as (b) it provides the terms and continuity on people, events, locations, and artifacts that have played an important role in the changing scene of human experience so as to represent an important historic connection [11]. With this diverse content of CL, along with its holistic, dynamic, and relativistic perception [37], emerges the need for a multidisciplinary and integrated approach on its preservation and protection, incorporating its historic, socioeconomic, cultural, and spatial dimension.

The CL of Eastern Mani has been developed through the interaction of specific historical, social, political, economic, and geomorphological characteristics: the common course and evolution of these characteristics have been imprinted in the typology and morphology of the built environment and architecture. In this sense, a sterile scenic representation and reproduction of the important historical and folklore activities of the daily life of the Maniots is not enough. On the contrary, the recognition of the special ritual or custom elements through the environment and the landscape itself is essential: after all, the social customs and traditions, as well as the history of the area, are all embedded in the stones that build each church and each war tower.