Quantitative Evaluation of China’s Central-Level Land Consolidation Policies in the Past Forty Years Based on the Text Analysis and PMC-Index Model

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Definition and Data Sources

2.2. Text Analysis

2.3. PMC-Index Model

3. Results of Policy Text Analysis

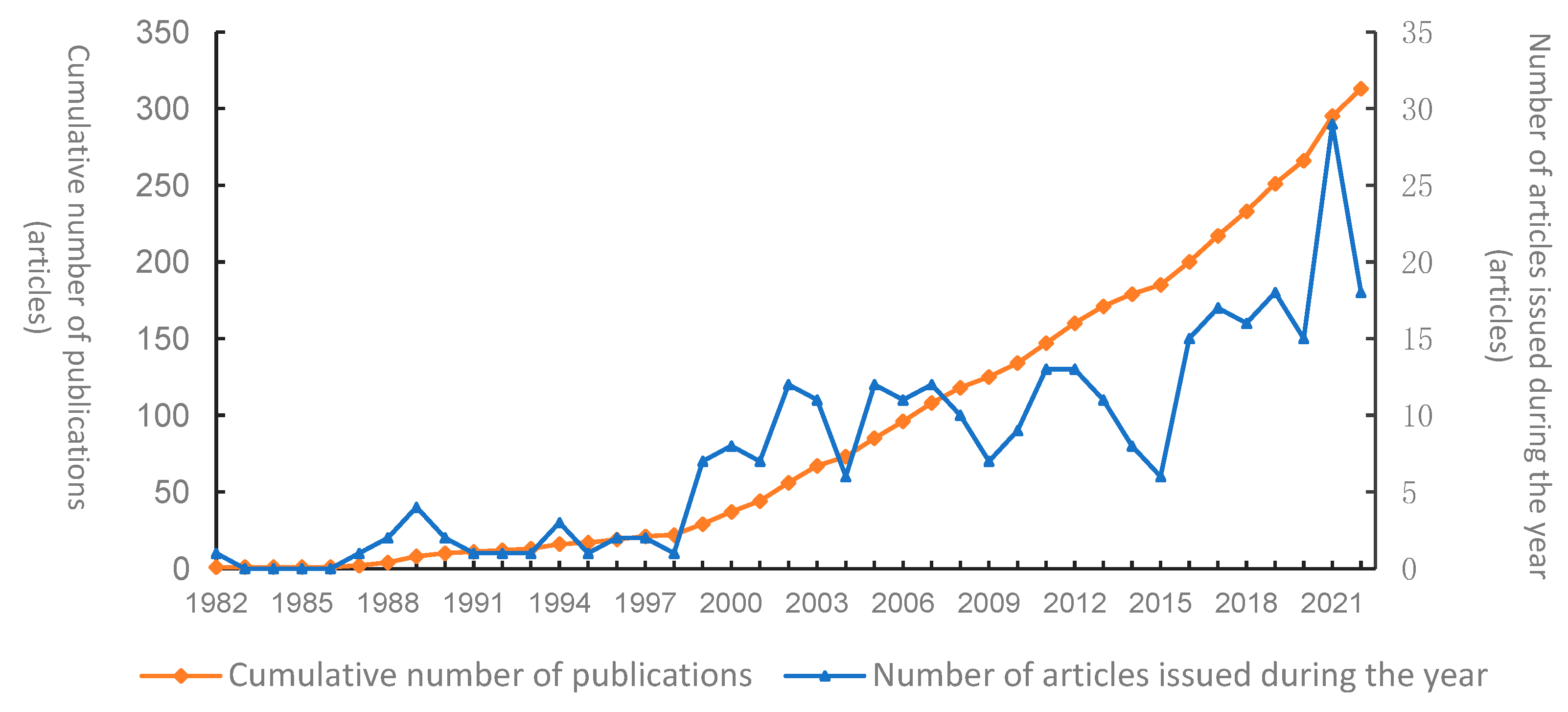

3.1. Statistics on Time of Issuance

3.2. Statistics on Types of Policies

3.3. Analysis of Issuing Departments and Cooperation Networks

3.4. Word Segmentation Extraction and High-Frequency Word Statistics

4. Empirical Analysis of the PMC-Index Model

4.1. Selection of Policies to Be Evaluated

4.2. Variable Selection and Parameter Setting

4.3. Establishment of Multi-Input–Output Table

4.4. Measurement of PMC-Index

4.5. Construction of the PMC-Surface

4.6. Analysis of PMC-Index Evaluation Results

4.6.1. Analysis of Overall Policy Evaluation Results

4.6.2. Analysis of PMC-Index Results for Individual Policies

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Y.; Zang, Y.; Yang, Y. China’s rural revitalization and development: Theory, technology and management. J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 1923–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niroula, G.S.; Thapa, G.B. Impacts and causes of land fragmentation, and lessons learned from land consolidation in South Asia. Land Use Policy 2005, 22, 358–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, D.; Crecente, R.; Alvarez, M.F. Land consolidation in inland rural Galicia, N.W. Spain, since 1950: An example of the formulation and use of questions, criteria and indicators for evaluation of rural development policies. Land Use Policy 2006, 23, 511–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Li, Y.; Xu, C. Land consolidation and rural revitalization in China: Mechanisms and paths. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntihinyurwa, P.D.; De Vries, W.T. Farmland Fragmentation, Farmland Consolidation and Food Security: Relationships, Research Lapses and Future Perspectives. Land 2021, 10, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pašakarnis, G.; Maliene, V. Towards sustainable rural development in Central and Eastern Europe: Applying land consolidation. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldrup, N.O. Agreement based land consolidation—In perspective of new modes of governance. Land Use Policy 2015, 46, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tang, Y.T.; Long, H.; Deng, W. Land consolidation: A comparative research between Europe and China. Land Use Policy 2022, 112, 105790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ye, Y.; Lin, Y. Experience and Enlightenment of Multifunctional Land Consolidation in Germany, Japan and Taiwan in China. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 3, 65–66,140–148. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Wu, W.; Liu, Y. Land consolidation for rural sustainability in China: Practical reflections and policy implications. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H. Land consolidation: An indispensable way of spatial restructuring in rural China. J. Geogr. Sci. 2014, 24, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, H.; Qu, Y. Land use transitions and land management: A mutual feedback perspective. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, Y. Strategic adjustment of land use policy under the economic transformation. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, J. Land Consolidation in Rural China: Historical Stages, Typical Modes, and Improvement Paths. Land 2023, 12, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fang, F.; Li, Y. Key issues of land use in China and implications for policy making. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Resler, L.M.; Campbell, J.B.; Chen, G.; Zhou, Y. The evaluation of land consolidation policy in improving agricultural productivity in China. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, G.; Wang, X.; Yun, W.; Zhang, R. A new system will lead to an optimal path of land consolidation spatial management in China. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 27–37. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Fan, P.; Jian, S.; Liu, Y. Land use and landscape change driven by gully land consolidation project: A case study of a typical watershed in the Loess Plateau. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y. Promotion of degraded land consolidation to rural poverty alleviation in the agro-pastoral transition zone of northern China. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhao, W.; Gu, X. Changes resulting from a land consolidation project (LCP) and its resource–environment effects: A case study in Tianmen City of Hubei Province, China. Land Use Policy 2014, 40, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Shao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Y. Land-use changes and policy dimension driving forces in China: Present, trend and future. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafael, C.; Carlos, A.; Urbano, F. Economic, social and environmental impact of land consolidation in Galicia. Land Use Policy 2002, 19, 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, M.; Davis, J. Land consolidation and productivity in Chinese household crop production. China Econ. Rev. 2005, 16, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Timo De Vries, W.; Li, G.; Ye, Y.; Zheng, H.; Wang, M. A behavioral analysis of farmers during land reallocation processes of land consolidation in China: Insights from Guangxi and Shandong provinces. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikor, T.; Müller, D.; Stahl, J. Land Fragmentation and Cropland Abandonment in Albania: Implications for the Roles of State and Community in Post-Socialist Land Consolidation. World Dev. 2009, 37, 1411–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ye, Y.; Wang, M.; Yu, Z.; Luo, J. The micro administrative mechanism of land reallocation in land consolidation: A perspective from collective action. Land Use Policy Int. J. Cover. All Asp. Land Use 2018, 70, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; De Vries, W.; Li, G.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, L.; Huang, H.; Wu, J. The suitability and sustainability of governance structures in land consolidation under institutional change: A comparative case study. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 87, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cay, T.; Ayten, T.; Iscan, F. Effects of different land reallocation models on the success of land consolidation projects: Social and economic approaches. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, M.A.R. Policy modeling: Definition, classification and evaluation. J. Policy Model. 2011, 33, 523–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, B.; Han, J.; Lu, X.; Zhang, X.; Fan, X. Quantitative evaluation of China’s cultivated land protection policies based on the PMC-Index model. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 105062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Zhang, W.; Lan, L. Quantitative Evaluation of China’s Ecological Protection Compensation Policy Based on PMC Index Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; Wang, B.; Chen, T.; Yang, J. A Document Analysis of Peak Carbon Emissions and Carbon Neutrality Policies Based on a PMC Index Model in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, Y. Quantitative Evaluation of High-Tech Industry Policies Based on the PMC-Index Model: A Case Study of China’s Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9338. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, S. Land consolidation and rural vitalization. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2018, 73, 1837–1849. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Coelho, J.; Portela, J.; Pinto, P.A. A social approach to land consolidation schemes: A Portuguese case study: The Valena Project. Land Use Policy 1996, 13, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Yang, Y.; Yan, J. The Connotation Research Review on Integrated Territory Consolidation of China in Recent Four Decades:Staged Evolution and Developmental Transformation. China Land Sci. 2018, 32, 78–85. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Han, B.; Jin, X.; Gu, Z.; Yin, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. Research progress and key issues of territory consolidation under the target of rural revitalization. J. Nat. Resour. 2021, 36, 3007–3030. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhong, L. Literature Analysis on Land Consolidation Research in China. China Land Sci. 2016, 30, 88–97. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Cao, X. What is the policy improvement of China’s land consolidation? Evidence from completed land consolidation projects in Shaanxi Province. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W. Harmonization of the concept of land consolidation for its development. China Land 2012, 8, 46–47. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Fang, Q.; Elliott, M.; Ikhumhen, H.O.; Liu, Z.; Meilana, L. The Transformation of 40-Year Coastal Wetland Policies in China: Network Analysis and Text Analysis. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 15251–15260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Luo, M.; Zhai, G. Review of land rehabilization research. Areal Res. Dev. 2003, 2, 8–11. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yun, W.; Zhu, D.; Tang, H. Reshaping and innovation of China land consolidation strategy. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2016, 32, 1–8. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H. Research on the Mechanism and Implementation Path of Comprehensive Land Consolidation to Promote Rural Revitalization. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2021, 5, 144–152. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wen, H.; Du, F. The Evolution Logic of Attention, Policy Motivation and Policy Behavior—Based on the Inspection of Process of Central Government’s Environmental Protection Policy from 2008 to 2015. Adm. Trib. 2018, 25, 80–87. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Estrada, M.A.; Yap, S.F.; Nagaraj, S. Beyond the Ceteris Paribus Assumption: Modeling Demand and Supply Assuming Omnia Mobilis; Social Science Electronic Publishing: Rochester, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Jia, M.; Xia, D. Dynamic evaluation of new energy vehicle policy based on text mining of PMC knowledge framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 392, 136237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Zhang, W.; Zong, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, G. How Effective Is the Green Development Policy of China’s Yangtze River Economic Belt? A Quantitative Evaluation Based on the PMC-Index Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xi, H. Quantitative Evaluation Innovation Policies of the State Council—Based on the PMC-Index Model. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2017, 34, 127–136. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Guo, X. Quantitative evaluation of China’s disaster relief policies: A PMC index model approach. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 74, 102911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qi, H. How effective is the fire safety education policy in China? A quantitative evaluation based on the PMC-index model. Saf. Sci. 2023, 161, 106070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Liu, J. Analysis of the State Council’s pension service policies: Exploration and quantitative evaluation based on the PMC-Index model. J. Yunnan Adm. Coll. 2020, 22, 167–176. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Yin, S.; Cui, D.; Mao, Z.; Sun, Y.; Jia, C.; An, S.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Du, Y.; et al. Quantitative evaluation of traditional Chinese medicine development policy: A PMC index model approach. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1041528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Qie, H. Quantitative Evaluation of the Impact of Financial Policy Combination to Enterprise Technology Innovation. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2017, 34, 113–121. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; He, R.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Xiong, J. Quantitative Evaluation of China’s Pork Industry Policy: A PMC Index Model Approach. Agriculture 2021, 11, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, L.; Pei, T. Quantitative evaluation of waste sorting management policies in China’s major cities based on the PMC index model. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1065900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Xing, C.; Li, X. Evaluation and analysis of new-energy vehicle industry policies in the context of technical innovation in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 281, 125126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Jiao, F.; Fan, S. Quantitative Evaluation of China’s Open and Sharing Policies of Scientific Data: Based on PMC Index Model. J. Intell. 2021, 40, 119–126. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tu, S. Rural vitalization in China: A perspective of land consolidation. J. Geogr. Sci. 2019, 29, 517–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Hu, Y. The new conception and review of territory consolidation based on the past years of reform and opening-up. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 53–67. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fu, L. Social work for common prosperity: What is possible and what can be done? Shandong Soc. Sci. 2022, 7, 15–20. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Rural Development and Its Planning Management in France: An Experience in Line with the Principle of Urban-rural Development. Urban Plan. Int. 2010, 25, 4–10. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Dong, J.; Yuan, Q.; Yin, L.; Li, X. Research on Quantitative Evaluation of Single Real Estate Policy Based on PMC Index Model—Taking China’s Housing Rental Policy Since the 13th Five-Year Plan as an Example. Manag. Rev. 2020, 32, 3–13, 75. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell, R.; Zegveld, W. Reindustrialization and Technology; Cartermill International: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y. Policy instrument mining and quantitative evaluation of new energy vehicles subsidies. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2017, 27, 188–197. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tong, W.; Lo, K.; Zhang, P. Land Consolidation in Rural China: Life Satisfaction among Resettlers and Its Determinants. Land 2020, 9, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisec, A.; Primožič, T.; Ferlan, M.; Šumrada, R.; Drobne, S. Land owners’ perception of land consolidation and their satisfaction with the results—Slovenian experiences. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 550–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonadonna, A.; Rostagno, A.; Beltramo, R. Improving the Landscape and Tourism in Marginal Areas: The Case of Land Consolidation Associations in the North-West of Italy. Land 2020, 9, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Circular | Measures | Opinions | Regulations | Outline | Decision | Law | Plan | Rules | Program | Announcement | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage I | 34 | 18 | 9 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Percentage (%) | 46.58% | 24.66% | 12.33% | 8.22% | 2.74% | 1.37% | 1.37% | 1.37% | 1.37% | 0% | 0% |

| Stage II | 63 | 13 | 15 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 7 |

| Percentage (%) | 56.25% | 11.61% | 13.39% | 1.79% | 0.89% | 1.79% | 0.00% | 2.68% | 0.89% | 4.46% | 6.25% |

| Stage III | 52 | 29 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 10 |

| Percentage (%) | 40.63% | 22.66% | 12.50% | 1.56% | 0.78% | 0.00% | 3.91% | 6.25% | 0.78% | 3.13% | 7.81% |

| Total | 149 | 60 | 40 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 17 |

| Percentage of total (%) | 47.60% | 19.17% | 12.78% | 3.19% | 1.28% | 0.96% | 1.92% | 3.83% | 0.96% | 2.88% | 5.43% |

| After Merging | Before Merging | 1982~2004 | 2005~2015 | 2016~2023 | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ① | ② | ① | ② | ① | ② | |||

| Central Committee of the Communist Party of China | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| State Council of the PRC | 15 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 33 | |

| Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 6 | |

| Ministry of Finance | 5 | 5 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 46 | |

| Natural resources authorities | State Land Administration | 3 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 140 |

| Ministry of Land and Resources | 32 | 1 | 54 | 12 | 11 | 4 | ||

| Ministry of Natural Resources | - | - | - | - | 16 | 6 | ||

| National Development and Reform Sector | State Planning Commission | 2 | 0 | - | - | - | - | 10 |

| National Development and Reform Commission | - | - | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 | ||

| National Forestry and Grassland Authorities | State Forestry Administration | 2 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 18 |

| National Forestry and Grassland Administration | - | - | - | - | 3 | 5 | ||

| Ministry of Water Resources | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | |

| National Leading Group for Comprehensive Agricultural Development | 1 | 0 | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| State Agriculture Comprehensive Development Office | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 5 | |

| National Standards Commission | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Ecological and environmental authorities | Ministry of Environmental Protection | - | - | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 18 |

| Ministry of Ecology and Environment | - | - | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Housing and urban and rural construction authorities | Ministry of Construction | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | - | 6 |

| Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development | - | - | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | ||

| Agricultural and rural authorities | Ministry of Agriculture | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 22 |

| Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs | - | - | - | - | 18 | 1 | ||

| Agricultural Bank of China | 0 | 1 | - | - | - | - | 1 | |

| Number | Vocabulary | Frequency | Number | Vocabulary | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Project | 3865 | 31 | Monitor | 671 |

| 2 | Plan | 1581 | 32 | Institution | 662 |

| 3 | Capital | 1478 | 33 | Land development and consolidation | 656 |

| 4 | Engineering | 1379 | 34 | Check up | 591 |

| 5 | Protect | 1353 | 35 | Investigate | 582 |

| 6 | Ecology | 1273 | 36 | Responsibility | 574 |

| 7 | Cultivated land | 1256 | 37 | Ecological environment | 558 |

| 8 | High-standard farmland | 1048 | 38 | Ecological protection | 535 |

| 9 | Quality | 1047 | 39 | Coordinate | 524 |

| 10 | Restore | 1039 | 40 | Comprehensive administration | 521 |

| 11 | Village | 975 | 41 | Farmland | 518 |

| 12 | Land rehabilitation | 877 | 42 | Natural resources | 515 |

| 13 | Cultivated land compensate | 861 | 43 | Reclaim | 512 |

| 14 | Returning farmland to forests and grasslands | 850 | 44 | Farmland protection | 501 |

| 15 | Agriculture | 828 | 45 | Target | 491 |

| 16 | Make experiments | 828 | 46 | Grassland | 490 |

| 17 | Produce | 822 | 47 | Farmer | 489 |

| 18 | Standard | 803 | 48 | Investment | 486 |

| 19 | Soil pollution | 800 | 49 | Pothook of city construction land increase and rural residential land decrease | 474 |

| 20 | Technology | 789 | 50 | Ecosystem | 471 |

| 21 | Administer | 775 | 51 | Cannot | 469 |

| 22 | Check and accept | 772 | 52 | Target | 465 |

| 23 | Land consolidation | 768 | 53 | Input | 454 |

| 24 | Construction land | 746 | 54 | Report to the ministry | 446 |

| 25 | Capital–farmland | 710 | 55 | Environment | 444 |

| 26 | Supervising | 687 | 56 | Management and protection | 427 |

| 27 | Development | 683 | 57 | Requisition–compensation balance | 421 |

| 28 | Area | 683 | 58 | Prevention and cure | 417 |

| 29 | Establish | 681 | 59 | Conservation of soil and water | 414 |

| 30 | Examine | 674 | 60 | Comprehensive agricultural development | 389 |

| Stage of Tapping the Quantitative Potential | Stage of Emphasizing on Both Quantity and Quality | Stage of Stressing Ecological Functions and Maximizing Urban–Rural Values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comprehensive policies | 70 | 109 | 126 |

| Specialized policies | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Item | Policy Name | Release Agency | Policy Classification | Release Time | Substage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POL1 | Circular of the Ministry of Land and Resources on further strengthening the management of land development and consolidation efforts | Ministry of Land and Resources, PRC | Comprehensive policy | 28 October 1998 | Stage of tapping the quantitative potential |

| POL2 | Circular of the Ministry of Land and Resources on effectively implementing the work of the cultivated land requisition-compensation balance | Ministry of Land and Resources, PRC | Specialized policy | 4 February 1999 | |

| POL3 | National Land Development and Consolidation Planning | Ministry of Land and Resources, PRC | Comprehensive policy | 7 March 2003 | |

| POL4 | Measures for the management of the use of land transfer fees for agricultural land development | Ministry of Finance, PRC; Ministry of Land and Resources, PRC | Specialized policy | 24 June 2004 | |

| POL5 | Circular of the Ministry of Land and Resources on adapting to the new situation to effectively improve the work related to land development and consolidation. | Ministry of Land and Resources, PRC | Comprehensive policy | 20 September 2006 | Stage of emphasizing on both quantity and quality |

| POL6 | Circular of the State Forestry Administration on conscientiously implementing the spirit of the State Council to perfect the policy of returning farmland to forests to carry out self-examination and rectification work of returning farmland to forests. | State Forestry Administration, PRC | Specialized policy | 9 November 2007 | |

| POL7 | Circular of the Ministry of Land and Resources on the Issuance of Specifications for the Construction of High-standard Basic Farmland (for Trial Implementation) | Ministry of Land and Resources, PRC | Specialized policy | 24 September 2011 | |

| POL8 | National Land Consolidation Planning (2011–2015) | Ministry of Land and Resources, PRC | Comprehensive policy | 27 March 2012 | |

| POL9 | National Land Planning Program (2016–2030) (excerpt) | the state Council of PRC | Comprehensive policy | 3 January 2017 | Stage of stressing ecological functions and maximizing urban–rural values |

| POL10 | National Land Consolidation Planning (2016–2020) | Ministry of Land and Resources, PRC; National Development and Reform Commission, PRC | Comprehensive policy | 10 January 2017 | |

| POL11 | Circular of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs on actively and steadily carrying out the work of revitalizing and utilizing idle residential land and idle dwellings in rural areas | Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, PRC | Specialized policy | 30 September 2019 | |

| POL12 | Construction plan for major projects for ecological protection and restoration of the southern hilly and mountainous belt (2021–2035) | National Forestry and Grassland Administration, PRC; National Development and Reform Commission, PRC; Ministry of Natural Resources, PRC; Ministry of Water Resources, PRC | Specialized policy | 30 December 2021 |

| First-Level Variables | Second-Level Variables | Foundation |

|---|---|---|

| X1 policy nature | X1:1 description, X2:2 prediction, X1:3 diagnosis, X1:4 supervise, X1:5 recommendation, X1:6 guide | [29] |

| X2 policy function | X2:1 increase the quantity of cultivated land, X2:2 improve the quality of cultivated land, X2:3 increase farmers’ income, X2:4 ecological environment protection and restoration, X2:5 coordinated urban–rural development, X2:6 restoration of landscape ecological functions, X2:7 continuation of cultural carriers | Induction of high-frequency words |

| X3 policy ideas | X3:1 economical and intensive utilization, X3:2 urban rural coordination, X3:3 adapting to local conditions, and X3:4 people-oriented | Induction of high-frequency words |

| X4 policy instrument | X4:1 supply-based, X4:2 demand-based, X4:3 environment-based | [52,58] |

| X5 incentives and constraints | X5:1 fiscal and taxation, X5:2 financial support, X5:3 performance evaluation, X5:4 planning constraints, X5:5 image storage, X5:6 prohibition and punishment | Induction of high-frequency words |

| X6 content evaluation | X6:1 clear goals, X6:2 sufficient basis, X6:3 detailed planning | [48,51,53] |

| X7a policy content | X7a:1 reclamation, X7a:2 land consolidation and development, X7a:3 high standard farmland construction, X7a:4 balance of occupation and compensation, X7a:5 permanent basic farmland construction, X7a:6 urban–rural construction land increase and decrease linkage, X7a:7 returning farmland to forests and grasslands, X7a:8 desertification prevention and control, X7a:9 soil pollution prevention and control, X7a:10 village remediation, X7a:11 other ecological protection and restoration projects, X7a:12 construction land remediation | Induction of high-frequency words |

| X7b functioning hierarchy | X7b:1 national level, X7b:2 provincial level, X7b:3 others | [54] |

| X8 participant subjects | X8:1 relevant administrative departments, X8:2 provincial governments, X8:3 county-level governments, X8:4 rural collectives, X8:5 farmers, X8:6 relevant rights and obligations holders, X8:7 enterprises | Induction of high-frequency words |

| X9 implementation guarantee | X9:1 investigation and monitoring, X9:2 fund guarantee, X9:3 laws and regulations, X9:4 supervision and management, X9:5 risk prevention and control, X9:6 science and technology, X9:7 information promotion, X9:8 improvement of planning system, X9:9 ownership adjustment and management, X9:10 public participation, X9:11 typical demonstration | [31,48] and high-frequency words |

| First-Level Variable | Second-Level Variable | POL1 | POL2 | POL3 | POL4 | POL5 | POL6 | POL7 | POL8 | POL9 | POL10 | POL11 | POL12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X1:1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| X1:2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X1:3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| X1:4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X1:5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| X1:6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| X2 | X2:1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| X2:2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| X2:3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| X2:4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X2:5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| X2:6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X2:7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| X3 | X3:1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| X3:2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| X3:3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| X3:4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| X4 | X4:1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| X4:2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| X4:3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| X5 | X5:1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| X5:2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| X5:3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X5:4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| X5:5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X5:6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| X6 | X6:1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| X6:2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| X6:3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X7a | X7a:1 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - |

| X7a:2 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| X7a:3 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| X7a:4 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - | |

| X7a:5 | 0 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 0 | 1 | - | - | |

| X7a:6 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| X7a:7 | 0 | - | 1 | - | 0 | - | - | 0 | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| X7a:8 | 0 | - | 1 | - | 0 | - | - | 0 | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| X7a:9 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | - | 0 | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| X7a:10 | 0 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| X7a:11 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | |

| X7a:12 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - | - | 0 | 1 | 1 | |||

| X7b | X7b:1 | - | 0 | - | 1 | - | 0 | 1 | - | - | - | 0 | 0 |

| X7b:2 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 0 | 1 | - | - | - | 0 | 1 | |

| X7b:3 | - | 1 | - | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | |

| X8 | X8:1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| X8:2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X8:3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X8:4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| X8:5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| X8:6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| X8:7 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| X9 | X9:1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| X9:2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X9:3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| X9:4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X9:5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| X9:6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X9:7 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| X9:8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| X9:9 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| X9:10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| X9:11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Comprehensive Policy | Specialized Policy | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-Level Variables | POL1 | POL3 | POL5 | POL8 | POL9 | POL10 | POL2 | POL4 | POL6 | POL7 | POL11 | POL12 |

| X1 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 1 |

| X2 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 1 | 0.86 | 1 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.71 | 0.57 | 0.43 |

| X3 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.75 | 1 | 0.75 |

| X4 | 0.67 | 1 | 0.33 | 1 | 1 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 1 | 0.67 |

| X5 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.5 | 0.33 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| X6 | 0.67 | 1 | 0.67 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.67 | 1 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 1 |

| X7a | 0.17 | 0.5 | 0.33 | 0.58 | 0.83 | 0.92 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| X7b | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.67 | 1 | 0.33 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.67 |

| X8 | 0.57 | 0.43 | 0.71 | 1 | 0.57 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.71 | 0.57 | 0.43 |

| X9 | 0.55 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.91 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.45 | 0.27 | 0.55 | 0.27 | 0.45 | 0.73 |

| PMC-Index | 4.55 | 5.75 | 4.53 | 8.33 | 7.32 | 8.23 | 4.93 | 5.38 | 4.09 | 5.62 | 5.43 | 6.17 |

| Evaluation rating | Acceptable consistency | Acceptable consistency | Acceptable consistency | Perfect consistency | Good consistency | Perfect consistency | Acceptable consistency | Acceptable consistency | Acceptable consistency | Acceptable consistency | Acceptable consistency | Good consistency |

| First-Level Variables | Second-Level Variables | Average Score of Comprehensive Policies | Average Score of Specialized Policies | Overall Average Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | X1:1 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.83 |

| X1:2 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.33 | |

| X1:3 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 0.75 | |

| X1:4 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | |

| X1:5 | 0.67 | 0.67 | 0.67 | |

| X1:6 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| X2 | X2:1 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.75 |

| X2:2 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.67 | |

| X2:3 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.92 | |

| X2:4 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| X2:5 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.42 | |

| X2:6 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.42 | |

| X2:7 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.42 | |

| X3 | X3:1 | 0.83 | 1.00 | 0.92 |

| X3:2 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.42 | |

| X3:3 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.75 | |

| X3:4 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.75 | |

| X4 | X4:1 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.75 |

| X4:2 | 0.50 | 0.17 | 0.33 | |

| X4:3 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| X5 | X5:1 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.42 |

| X5:2 | 0.17 | 0.33 | 0.25 | |

| X5:3 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.50 | |

| X5:4 | 0.83 | 0.50 | 0.67 | |

| X5:5 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| X5:6 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | |

| X6 | X6:1 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 |

| X6:2 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| X6:3 | 0.83 | 0.33 | 0.58 | |

| X7a | X7a:1 | 1.00 | - | 1.00 |

| X7a:2 | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | |

| X7a:3 | 0.50 | - | 0.50 | |

| X7a:4 | 0.00 | - | 0.00 | |

| X7a:5 | 0.67 | - | 0.67 | |

| X7a:6 | 0.50 | - | 0.50 | |

| X7a:7 | 0.50 | - | 0.50 | |

| X7a:8 | 0.50 | - | 0.50 | |

| X7a:9 | 0.33 | - | 0.33 | |

| X7a:10 | 0.83 | - | 0.83 | |

| X7a:11 | 0.50 | - | 0.50 | |

| X7a:12 | 0.33 | - | 0.33 | |

| X7b | X7b:1 | - | 0.33 | 0.33 |

| X7b:2 | - | 0.67 | 0.67 | |

| X7b:3 | - | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| X8 | X8:1 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| X8:2 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.75 | |

| X8:3 | 0.83 | 0.83 | 0.83 | |

| X8:4 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| X8:5 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| X8:6 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.42 | |

| X8:7 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.42 | |

| X9 | X9:1 | 0.83 | 0.67 | 0.75 |

| X9:2 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.50 | |

| X9:3 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.58 | |

| X9:4 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.92 | |

| X9:5 | 0.50 | 0.33 | 0.42 | |

| X9:6 | 0.67 | 0.17 | 0.42 | |

| X9:7 | 0.50 | 0.67 | 0.58 | |

| X9:8 | 0.83 | 0.33 | 0.58 | |

| X9:9 | 1.00 | 0.33 | 0.67 | |

| X9:10 | 0.67 | 0.33 | 0.50 | |

| X9:11 | 0.67 | 0.50 | 0.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Huang, G.; Shen, X.; Zhang, X.; Gu, W. Quantitative Evaluation of China’s Central-Level Land Consolidation Policies in the Past Forty Years Based on the Text Analysis and PMC-Index Model. Land 2023, 12, 1814. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091814

Huang G, Shen X, Zhang X, Gu W. Quantitative Evaluation of China’s Central-Level Land Consolidation Policies in the Past Forty Years Based on the Text Analysis and PMC-Index Model. Land. 2023; 12(9):1814. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091814

Chicago/Turabian StyleHuang, Guodong, Xiaoqiang Shen, Xiaobin Zhang, and Wei Gu. 2023. "Quantitative Evaluation of China’s Central-Level Land Consolidation Policies in the Past Forty Years Based on the Text Analysis and PMC-Index Model" Land 12, no. 9: 1814. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12091814