Abstract

This study focuses on the land transfer intentions of migrants and surrounding villagers in the SZ resettlement area of BS City, Guangxi. It systematically analyzes the coupling coordination relationship between migrants’ land transfer-in intentions and the land transfer-out intentions of surrounding villagers, verifying the practical value of the “Shared Land Resource Model” in the resettlement area and its surroundings. The study yields the following key conclusions: (1) there is a strong coupling between the land demand intentions of migrants and the land supply intentions of surrounding villagers, yet the actual coordination in the transfer process is limited, which constrains resource allocation efficiency and prevents land transfer from fully utilizing shared resources; (2) in the evaluation of migrants’ land transfer-in intentions, external environmental factors have the greatest influence (with a weight coefficient of 0.7877), while individual characteristics (0.0486) and psychological characteristics (0.0593) have relatively low weight coefficients, indicating that migrants primarily rely on government policy support and lack internal motivation; (3) the land transfer-out intentions of surrounding villagers are most affected by farmland resource endowment (weight coefficient of 0.3284), indicating that the quality and quantity of land resources are key factors affecting villagers’ transfer-out willingness, while individual endowment factors have the smallest impact (weight coefficient of 0.1220). Three recommendations are proposed: stimulating migrants’ intrinsic motivation to enhance livelihood autonomy, protecting villagers’ land rights to increase transfer participation, and building a systematic land resource sharing model to promote sustainable resource allocation. This study provides theoretical support for optimizing the land transfer mechanism in resettlement areas, aiming to improve land use efficiency, support the livelihood transition of migrants, and offer practical insights for land management planning in poverty alleviation and resettlement projects in other countries.

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the 21st century, China has been in a mid-stage acceleration phase of urbanization, with the urbanization rate of its permanent population reaching 66.16% in 2023 [1]. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences predicts that by 2030, China will have an additional 310 million urban residents [2]. Rapid urbanization has led to a severe abandonment of arable land, significantly reducing land use efficiency [3]. According to data from the China Household Finance Survey (CHFS), China’s idle arable land rate had already reached 15% in 2013 [4]. Land transfer, whereby farmers transfer land use rights to others or institutions, has become an effective approach to addressing the issues of fragmented and idle land use in rural China. “Measures for the Administration of Rural Land Management Rights Transfer”, issued by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs in 2021, and China’s “No. 1 Central Document of 2023” explicitly encourage the voluntary transfer of rural land management rights to support the rational allocation and efficient use of rural land resources [5,6]. However, there is a serious imbalance in land transfer rates across different regions of China. According to the 2022 Statistical Report of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, the nationwide transfer rate of rural contracted land management rights was 36.73%. In developed regions such as Jiangsu and Guangdong, the rate reached around 60%, while in less developed areas such as Guangxi and Yunnan, it was only about 15%. It is evident that less developed areas represent a shortfall in the sustainable development of the land transfer market [7]. Therefore, effectively promoting land transfer growth in underdeveloped areas is a critical and challenging issue in achieving the efficient allocation of agricultural land resources, which holds significant practical importance in advancing sustainable agricultural development in China and other countries.

In 2001, the National Development and Reform Commission of China formally introduced the concept of “relocation for poverty alleviation” as an effective measure to address the issue of “one region’s resources being unable to sustain its population”, thereby breaking the cycle of intergenerational poverty and enabling the rapid development of impoverished communities [8]. However, as a government-led social initiative, relocation for poverty alleviation, while achieving policy goals and meeting rigid resettlement targets, has encountered practical challenges due to its inherent limitations, resulting in a fragile social foundation for migrants’ sustainable livelihoods [9]. In particular, the limited availability of distributable land in certain areas has led to the widespread adoption of a “landless resettlement” model (whereby relocated populations are moved to centralized resettlement areas without arable land allocation, thus requiring migrants to rely primarily on non-agricultural employment for livelihood transformation and diversified income sources) [10]. The rapid transition in living environments has led to fluctuations in multiple forms of livelihood capital and, especially, a significant reduction in natural capital, which has hindered the reconstruction of migrants’ livelihood capacities [11].

Under the influence of China’s urbanization process, the significant shift in rural labor around resettlement areas towards non-agricultural sectors has led to the problem of abandoned arable land. In response, the land transfer mechanism is considered a viable solution [12]. Surrounding villagers can increase their income and promote rural economic development through land transfer-out, thereby enhancing land use efficiency. Meanwhile, migrants can gain land use rights through land transfer-in, helping them to address the livelihood transition challenges resulting from the sharp reduction in natural capital post-relocation and to support sustainable development. The surrounding villagers with land management rights and the migrants with farming skills are the primary participants and stakeholders in a resettlement area’s land transfer market. Land transfer not only requires government promotion but also heavily depends on the willingness of both farmers and migrants [13].

To explore the feasibility of this mechanism, this study focuses on the migrants in the SZ resettlement area of BS City, Guangxi, China, and the surrounding villagers, proposing a shared arable land resource model around the resettlement area. Based on rational choice theory and resource dependence theory, a land transfer intention index system was constructed to calculate the coupling coordination degree of migrants’ land transfer-in intentions and surrounding villagers’ land transfer-out intentions, analyzing the coupling relationship between land transfer supply and demand intentions. This study provides theoretical support for improving the land transfer (leasing) mechanism to enhance land use efficiency, support migrants’ livelihood transitions, and achieve sustainable development in the resettlement area. It may also serve as a valuable reference for poverty alleviation and migration planning in other countries.

2. Literature Review

A review of existing research reveals that since the implementation of the “separation of three rights” reform in rural land in 2014, the ownership, contracting rights, and management rights of rural land in China have been effectively separated, leading to improvements in land use efficiency [14]. This institutional reform has provided a significant policy foundation for rural land transfer [15]. Land transfer primarily refers to the transfer of land use rights, whereby farmers who hold contracted management rights transfer their land management rights to other farmers or economic organizations, thus retaining contracting rights while transferring usage rights [16].

Current research on land transfer in China mainly focuses on the status and models of land transfer, factors influencing transfer intentions, and the impact on farmers’ income and production efficiency. However, the subjects of these studies are mostly ordinary farmers, with limited research examining migrants relocated for poverty alleviation as the primary focus. From the perspective of land transfer models, the main types include direct transfer, cooperative-scale transfer, capital transfer, and land trusteeship [17]. In terms of transfer intentions, current research on ordinary farmers indicates that factors such as age, gender [18], family structure [19], and land returns [17] significantly influence transfer intentions [20]. Additionally, factors such as land ownership, trust in the government [21], farming purposes [22], household income [23], and risk perception further enrich the research framework for land transfer intentions [24]. Generally, ordinary farmers show a low willingness to acquire land but a higher willingness to transfer it out [25]. Furthermore, studies have shown that land transfer in China not only optimizes land resource allocation but also plays a critical role in increasing farmers’ income, promoting large-scale operations, and improving production efficiency [26]. Moreover, land transfer helps reduce poverty vulnerability [27], providing dual support for economic and social sustainability in rural areas.

In most countries globally, rural land is privately owned, allowing rural land transactions to occur through either sales or leasing. Consequently, rural land transaction markets are composed of rural land sales and rural land rental markets [26]. Internationally, concepts similar to land transfer include Japan’s farmland consolidation [28] and land leasing in countries such as Poland [29] and Ireland [30]. Due to high transaction costs, credit risks, and legal and familial constraints, land transfer through sales is often quite limited [31]. As an alternative to purchasing agricultural land, land leasing has increasingly been accepted as a mechanism to secure land use rights [32,33]. Researchers have found that land leasing performs a social function by enabling individuals without land or with limited capital and income to access land, thereby facilitating entrepreneurship in agriculture [34]. Both lessors and lessees can obtain additional income through land leasing [35]. Moreover, land leasing offers lower risk [36] and greater managerial flexibility [37]. Therefore, whether in terms of China’s land transfer or land leasing in other countries, the core objective is to facilitate the transfer of land use rights from less productive to more productive users in a more accessible way, promoting the productive use of land as a resource and increasing income for both parties involved in the lease [38].

Existing research on land transfer (leasing) has primarily focused on ordinary farmers, demonstrating the advantages of land transfer (leasing) in improving land use efficiency and increasing farmer income. Studies have also highlighted different land transfer models and factors influencing land transfer decisions. However, there is limited research that considers migrants as the main subjects in land transfer (leasing) behavior. The differences between ordinary farmers and migrants are significant and cannot be overlooked. Relocation for a poverty alleviation program has a distinct poverty alleviation focus, and the livelihood recovery of such migrants, a unique group in China, directly reflects the program’s success. Given that most migrants have engaged in agricultural activities prior to relocation, the provision of arable land post-relocation is crucial to support their transition in terms of livelihood and to facilitate sustainable development.

3. Land Transfer Models and Analytical Framework

3.1. Current Land Transfer Models

Relocation for poverty alleviation mostly occurs in the central and western regions of China. Due to constraints on arable land resources and the requirements of new urbanization, landless resettlement is commonly implemented during relocation. In particular, concentrated resettlement in urban areas and surrounding counties is carried out without the allocation of farmland resources. The policy preferences, industrial support, and employment assistance associated with relocation generate a clustering effect that effectively helps most migrants transform their livelihood strategies and adjust their means of subsistence [39]. However, it is undeniable that landless resettlement represents a significant external shock to migrants who previously relied on agricultural production as their primary livelihood. If these migrants are unable to adapt to the new means of resource acquisition and transformation, then they may fall back into hardship. Therefore, tailoring support to the specific characteristics of the migrants and maximizing the use of existing resources is critical in the post-relocation support phase to enhance their livelihood capital [40].

Through field research in July 2024, two types of land transfer models were identified in the SZ relocation settlement area of BS City. The first model is government-led land transfer: the local government coordinates the process and pays rent for the transfer of 5400 mu of land from three surrounding villages. This land is used in partnership with enterprises for the cultivation of oil tea (a high-economic-value cash crop whose seeds can be pressed to produce edible oil that is beneficial to human health) and the development of premium orchid nurseries, which serve as collective industries for the resettlement area. The profits from these industries are shared between the enterprises and the resettlement area, while land rent is paid to the surrounding village collectives.

“These two pieces of land for collective economic use are actually part of the government’s support policy. The government paid for the land transfer from the surrounding villages, and we can use the land directly. Now, we earn over one million yuan a year from this, and we are planning to transfer more land to further increase this income.”—Interview with the First Secretary of the Resettlement Area.

Due to the development stage of the migrant population and the limitations of local industry types, most of the industrial support for relocation-based poverty alleviation requires the use of land resources, primarily in agricultural sectors. A significant proportion of this land consists of idle state-owned land or farmland transferred or requisitioned by the local government from surrounding villages. This land is then provided to the resettlement area free of charge or at a very low cost for industrial support purposes. The resettlement area reuses the land through collective cooperatives or by subleasing it to enterprises, with the profits going to the resettlement area’s collective to support its sustainable development. Currently, the SZ resettlement area operates two agricultural industries: the “Orchid Nursery” and the “Ten Thousand Mu Oil Tea Plantation”. The “Orchid Nursery” covers 20 mu of land, which was directly requisitioned by the government as collective land. The land for the “Ten Thousand Mu Oil Tea Plantation” consists of idle state-owned land provided by the government and transferred collective land from surrounding villages. After nearly five years of development, these two industries have generated stable annual revenues in the millions. The resettlement area plans to expand these industries to further increase revenue. However, the SZ resettlement area is located in Guangxi, which features a karst landscape with small and fragmented plots of sloped land. To ensure planting efficiency, this type of land transfer prioritizes larger contiguous plots or mountainous forest land, while fragmented or sloped land is generally not accepted.

The second model involves individual negotiations between migrants and surrounding villagers for land transfer. Since farming was the primary source of income for most migrant families before relocation, younger migrant laborers have had more job opportunities after relocation and successfully transitioned their livelihoods. However, some older migrants struggled to adapt to the landless resettlement model, finding it difficult to shift their livelihoods. As a result, they have independently transferred around 200 mu of fragmented sloped land from surrounding villages to grow crops such as sugarcane, corn, and vegetables, which not only provide food for their families but also generate a small amount of income [41].

“I’m in my sixties, and no one wants to hire me here. I’ve been farming all my life, so I just wanted to find some land to keep farming and help support my family. By chance, I met a friend from NDS Village while playing cards. His family has more than five mu of land, and since he works in the city most of the time, most of his land has been transferred to the resettlement area for growing oil tea. He still had about one mu of sloped land left, which he didn’t want to farm anymore. So, I talked to him, and since the land was just sitting idle, he agreed to transfer it to me. I use it to grow vegetables to support my family, and I only pay him 200 yuan a year. It’s a win-win, and I made a friend in the process.”—Interview with a resettlement area villager.

Due to the influence of urbanization, an increasing number of villagers around the resettlement area have changed their livelihoods, opting to migrate to cities for work. This shift has led to a shortage of agricultural labor in rural areas and an increasing amount of idle land. On one hand, the vacant land allows the resettlement area to continue transferring land and expanding its industrial development [42]. On the other hand, the availability of more idle, fragmented sloped land provides opportunities for migrants to transfer and farm the land on their own.

3.2. Analytical Framework

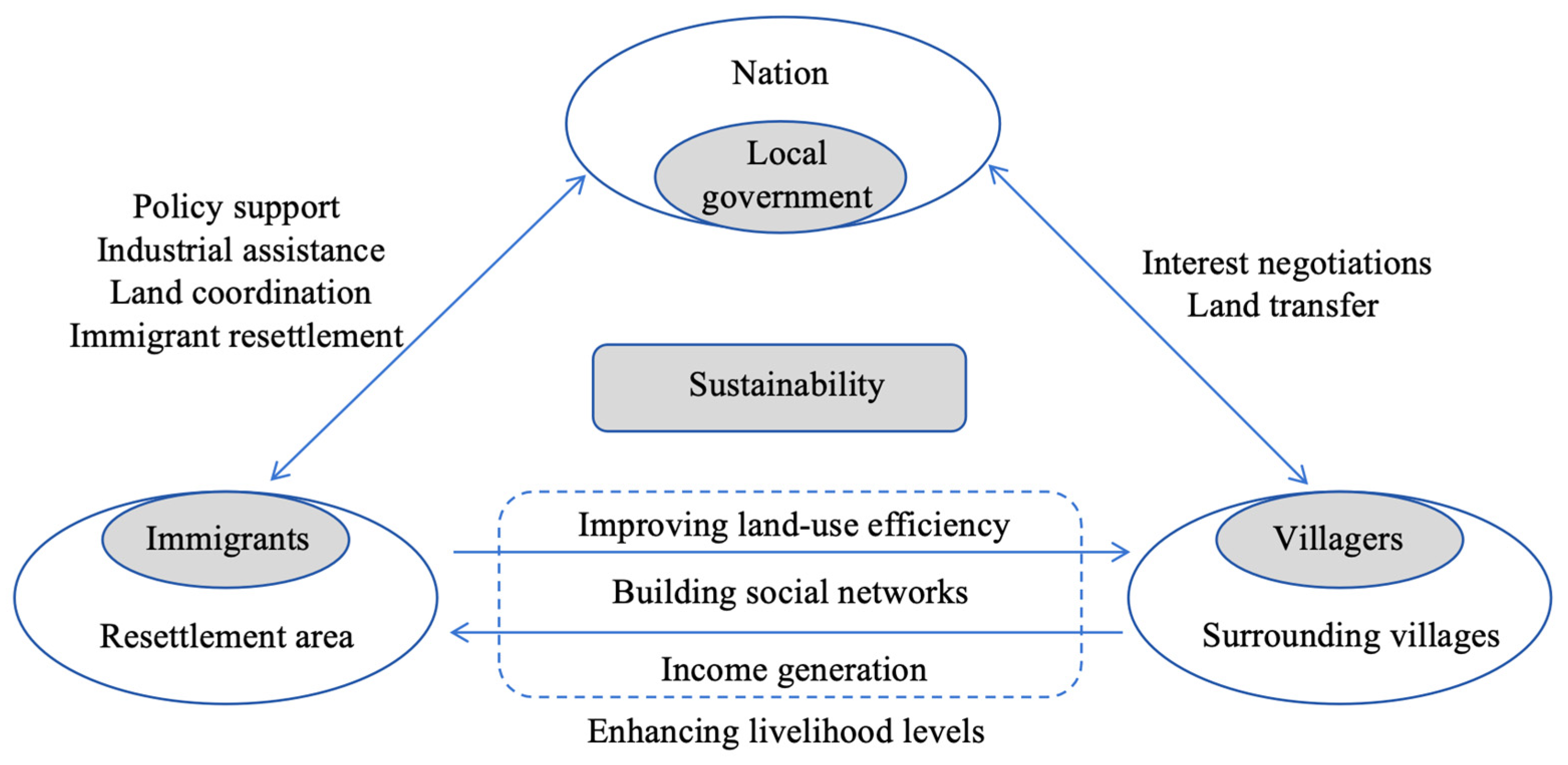

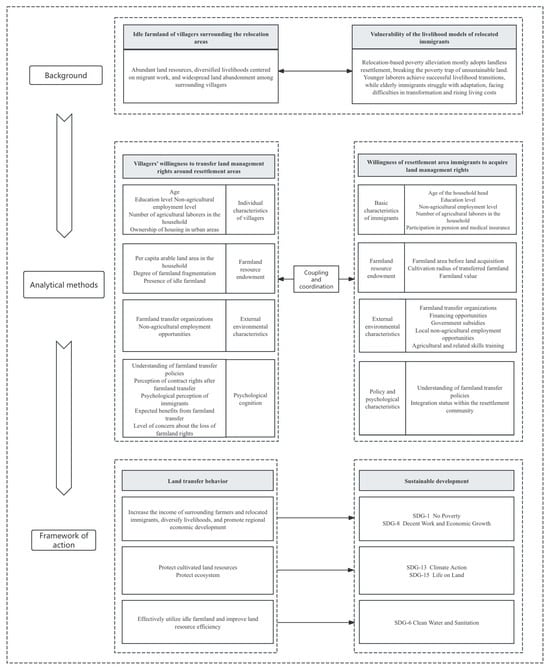

Based on policy support and industrial assistance, the idle farmland around the resettlement area holds significant economic potential. This study proposes a shared farmland resource model for the areas surrounding the resettlement zone. On one hand, the government coordinates the transfer of large tracts of idle farmland around the resettlement area to the settlement through land transfer mechanisms. The resettlement area utilizes this land to develop agricultural industries and provides industrial training, attracting migrants with farming skills to participate. Surrounding villagers can either lease their land for transfer and receive dividends or receive annual rental income from the land transfer. On the other hand, migrants can enter into land contracting agreements with surrounding villagers, independently transferring fragmented sloped land for subsistence farming, which provides additional income for their families. Villagers, in turn, can successfully lease out idle farmland that is unsuitable for large-scale transfer, increasing their income. This model not only helps migrants enhance their livelihood capital but also offers an opportunity for surrounding villagers to increase their income. It also greatly promotes interactions between migrants and surrounding villagers, strengthens their social networks, and contributes to the sustainable development of the resettlement area and its surrounding regions [43]. The model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Shared farmland resource model for the areas surrounding the resettlement zone.

Rational choice theory suggests that surrounding villagers in resettlement areas consider various factors in making farmland transfer-out decisions to maximize utility [44]. In this theory, individual characteristics (such as age and education level) and psychological cognition (such as attitudes toward migrants and understanding of policies) influence villagers’ assessments of expected returns and risks from land transfer-out. Farmland resources (such as the availability of idle land and land area) affect potential benefits, while external environmental factors (such as non-agricultural employment opportunities and the presence of land transfer organizations) provide external support for the transfer process. Resource dependence theory emphasizes the impact of reliance on external resources on individual or organizational behavior. In migrants’ intentions to transfer-in farmland, basic characteristics (such as non-agricultural employment level and age of the household head) determine their demand and dependence on farmland resources. Farmland resources (such as land value) and external environmental factors (such as government subsidies and non-agricultural employment opportunities) affect resource availability, while psychological characteristics (such as the level of integration into the resettlement area) influence migrants’ dependence on and confidence in these resources. This theory helps explain why migrants are more inclined to increase farmland transfer-in under certain resource conditions to meet livelihood needs. Based on this, it is essential to explore the land transfer intentions of both migrants and surrounding villagers from a micro-level perspective by investigating the feasibility of constructing a shared farmland resource model around resettlement areas.

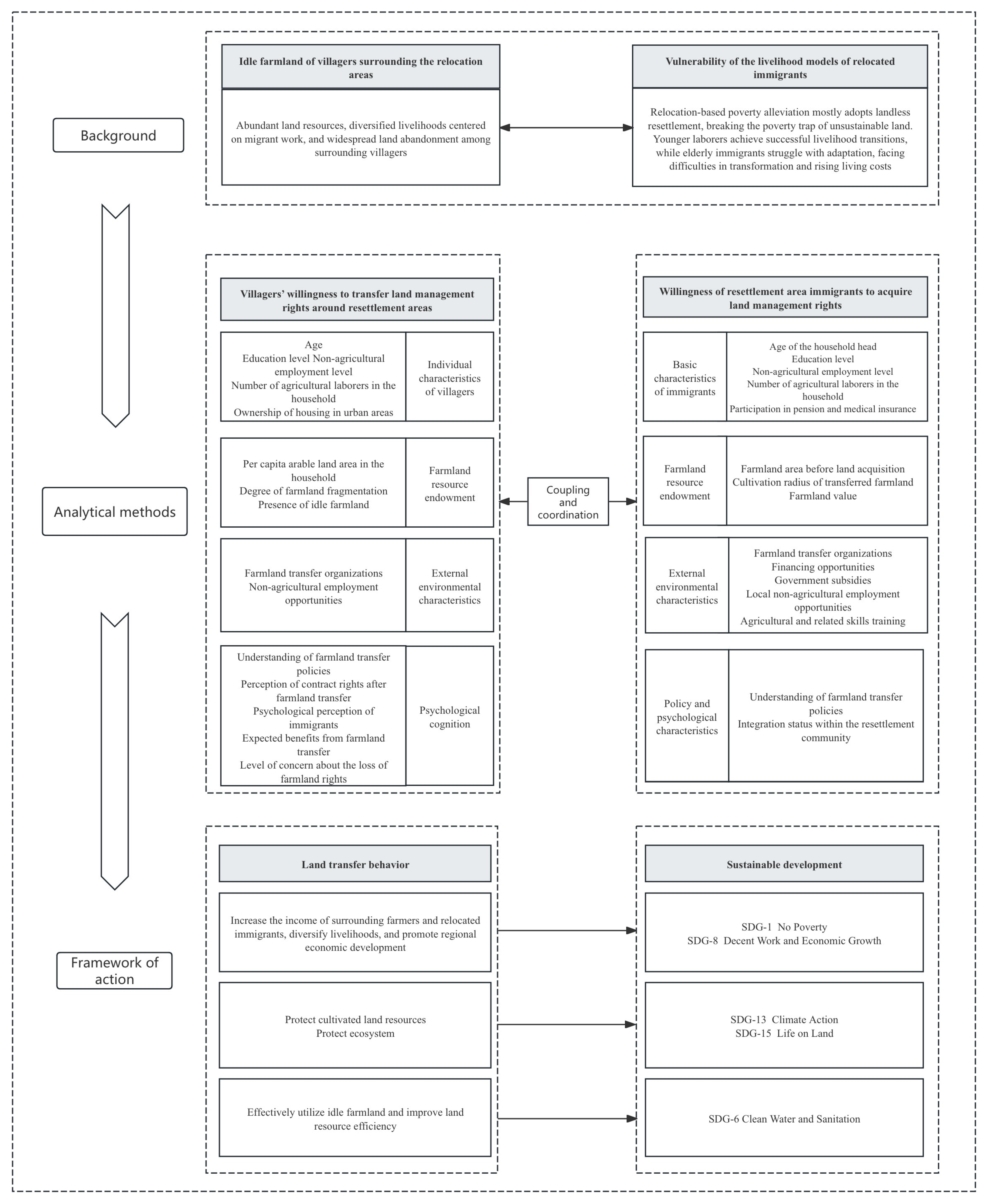

In China’s process of relocation for poverty alleviation, the rational development and utilization of idle farmland in urbanized resettlement areas and surrounding villages can achieve multiple goals related to sustainable development [45]. These goals are closely aligned with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly in terms of the coordinated development of the economy, society, and environment. First, reintroducing idle farmland into modern, specialized, and ecological agricultural production can increase the income of both the surrounding villagers and migrants, promote livelihood diversification, and help impoverished groups escape poverty, directly contributing to the achievement of SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) [46,47]. Second, the development of idle farmland is not limited to agricultural production. As some of the land is located in ecologically fragile areas, attention should be paid to ecological conservation and restoration during the development process. Through ecological restoration, carbon sink capacity can be enhanced, helping achieve SDG 13 (Climate Action) and SDG 15 (Life on Land). Finally, the rational use of idle farmland can contribute to improving the sustainable management of water and land resources, thereby promoting the achievement of SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation). Based on this analysis, this study constructs an analytical framework for studying the coupling between the demand for farmland transfer-in by resettled migrants and the supply potential for farmland transfer-out by surrounding villagers (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Analytical framework.

4. Data Sources and Research Methods

4.1. Overview of the Study Area

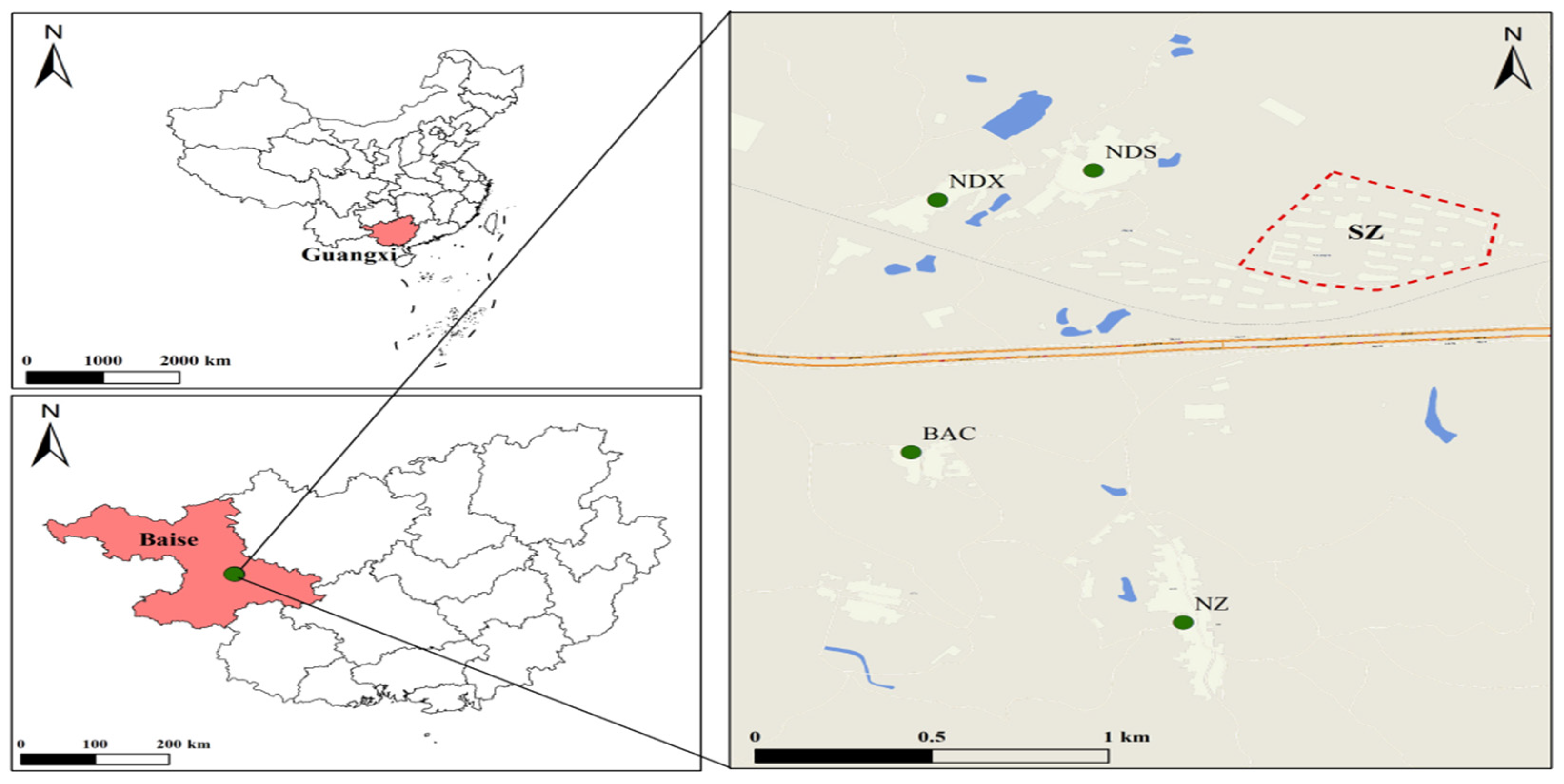

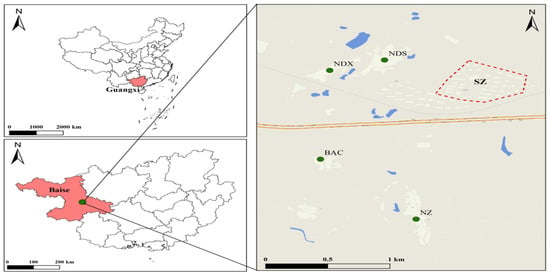

This study is based on the SZ relocation settlement area in BS City, Guangxi, China. SZ is the largest cross-county relocation settlement for poverty alleviation in Guangxi, covering an area of 565 mu with a total building area of 623,700 square meters. The landless resettlement program has relocated 4285 households, totaling 18,419 people, from 304 villages in 57 surrounding townships. The location of the SZ resettlement area is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Map of the SZ resettlement area.

4.2. Data Sources

The data for this study were collected through field surveys. The author conducted surveys in the SZ resettlement area and four surrounding villages in BS City, Guangxi, in February 2023, July 2023, and July 2024. To ensure the objectivity and accuracy of the survey data, questionnaires were randomly distributed. In the SZ resettlement area, 300 questionnaires were distributed; 273 were returned, of which 254 were valid, yielding an effective response rate of 93.04%. In the four surrounding villages, 300 questionnaires were distributed; 284 were returned, of which 252 were valid, yielding an effective response rate of 88.73%.The sample distribution is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample distribution.

According to the research data, the land transfer-in intention of migrants in the resettlement area is as high as 69.60%, while the land transfer-out intention of surrounding villagers is 74.18%. This indicates a strong supply and demand foundation for land resource transfer in the relocation resettlement areas for poverty alleviation. Such high willingness reflects both parties’ need for optimized land resource allocation. Migrants seek to restore or expand their livelihood through land acquisition, while surrounding villagers are willing to transfer land for economic gain.

4.3. Construction of Indicators

Considering the dimensions of individual and household characteristics, farmland resource endowments, external environmental characteristics, and psychological characteristics, this study selected 15 questions to construct an evaluation index system for the land transfer-in intentions of migrants in the resettlement area [13], as shown in Table 2. At the same time, the migrants’ land transfer-in intention was set as the dependent variable and divided into two categories: “willing” and “unwilling”. A value of 1 was assigned to “willing”, and 0 was assigned to “unwilling”.

Table 2.

Evaluation indicators for the land management transfer-in intentions of migrants in the resettlement area.

Using the same approach, 16 indicators were selected from the four dimensions mentioned above to construct an evaluation index system for the land transfer-out intentions of surrounding villagers. As shown in Table 3.The villagers’ land transfer-out intention was also set as the dependent variable and divided into two categories: “willing” and “unwilling”. A value of 1 was assigned to “willing”, and 0 was assigned to “unwilling”.

Table 3.

Evaluation indicators for land management transfer-out intentions of surrounding villagers in the resettlement area.

4.4. Research Methods

To accurately evaluate the coupling and coordination relationship between the land transfer-in demand of migrants and the land transfer-out supply of surrounding villagers in resettlement areas, the data were first standardized using range standardization. Then, the Probit regression model was applied for indicator screening, and indicator systems for migrants’ willingness to transfer in farmland and surrounding villagers’ willingness to transfer out farmland were constructed. Subsequently, the comprehensive index method was used to calculate the comprehensive indices of migrants’ willingness to transfer in farmland and surrounding villagers’ willingness to transfer out farmland. Finally, the coupling coordination model was employed to measure the coupling coordination development level between these two aspects.

4.4.1. Probit Regression Model

Since the dependent variable in this study is land transfer willingness (willing = 1, unwilling = 0), which is a binary discrete variable, directly using a traditional linear regression model to estimate the influencing factors of migrants’ farmland transfer-in willingness and surrounding villagers’ farmland transfer-out willingness may lead to biased parameter estimation results [48,49]. Therefore, a binary Probit model was adopted to screen the indicators from the sample data. The model is specified as follows:

where represents the transfer willingness; represents the -th variable; represents the coefficient of the -th indicator; and represents the random disturbance term.

4.4.2. Comprehensive Index Method

We calculated weights using the entropy method, as follows:

Let be the proportion of the -th sample data for the -th indicator; represents the entropy value of the -th indicator, ; , where is the number of samples (rows); when , let ; is the entropy redundancy; and is the weight result.

We calculated the comprehensive evaluation coefficient of indicators using the comprehensive index method:

Here, is the comprehensive index, is the weight of each indicator, and is the standardized value of the indicator.

4.4.3. Coupling Coordination

Coupling effects and the degree of coupling coordination are commonly used as tools in social evaluation research, with coupling coordination models being more frequently employed. These models use coupling degrees to explain the relationships between multiple systems, while the degree of coordinated development is used to comprehensively evaluate and study the entire system [50]. The coupling degree represents the interaction between two related systems, whereas the coordinated development degree represents the coordination level between the elements of the two systems [51]. Based on the model used by scholars such as Wang S. [52], the coupling degree model adopted in this study reveals the strength of interaction between the demand for farmland transfer-in by migrants in the resettlement area and the supply of farmland transfer-out by surrounding villagers. The model is as follows:

Here, represents the system coupling degree, is the comprehensive evaluation coefficient of the migrants’ land transfer-in demand system, and is the comprehensive evaluation coefficient of the surrounding villagers’ land transfer-out supply system. Both values are in the range of , meaning that the coupling degree also has a range of . The larger the value of , the higher the coupling degree; conversely, the smaller the value of , the lower the coupling degree. The classification of coupling degree types is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Classification of coupling types between migrants’ farmland transfer-in intentions and surrounding villagers’ farmland transfer-out intentions.

To further reflect the coordinated development level of migrants’ farmland transfer-in intentions and surrounding villagers’ farmland transfer-out intentions in the resettlement area, a coupling coordination degree model was constructed, as shown below:

Here, represents the comprehensive coordination index between migrants’ land transfer-in intentions and surrounding villagers’ land transfer-out intentions, is the standardized value of the -th subsystem, and is an undetermined coefficient for the land transfer-in intention and land transfer-out intention systems. This study assumes that both systems are equally important, so ; represents the coordination degree between the two systems of migrants’ land transfer-in intentions and surrounding villagers’ land transfer-out intentions.

Referring to relevant studies [53], this study uses a numerical grading method to construct a classification method for the coupling coordination degree levels, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Classification table for coupling coordination levels.

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Indicator Selection

This study used SPSS to conduct a Probit regression model for indicator selection, removing insignificant variables. This process helped construct the evaluation index system for the farmland management rights and transfer-in intentions of migrants in the resettlement area and the transfer-out intentions of surrounding villagers. The specific calculation results are shown in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 6.

Probit regression model results for migrants’ willingness to transfer in farmland operational rights in resettlement areas.

Table 7.

Probit regression model results for surrounding villagers’ willingness to transfer out farmland operational rights in resettlement areas.

This study, through the Probit regression model, concludes that the influencing factors in migrants’ willingness to transfer in farmland in resettlement areas come from four dimensions. However, indicators X1 (Age of the household head), X2 (Education level), X3 (Non-farm employment level), X5 (Whether someone has a pension, medical insurance, or other insurance), X6 (Quantity of land resources before land acquisition), X11 (Government subsidies), and X14 (Understanding of the land transfer policy) did not pass the significance test. Consequently, the indicator system for migrants’ willingness to transfer in the operational rights of farmland in resettlement areas is constructed, consisting of eight indicators. The specific details are shown in Table 6.

This study, through a Probit regression model, concludes that the influencing factors in surrounding villagers’ willingness to transfer out farmland in resettlement areas come from four dimensions. However, indicators Y1 (The age of the household head), Y4 (The proportion of household non-agricultural income), Y7 (The per capita arable land area of the family), Y10 (Agricultural land transfer organization), and Y13 (Recognition of the contract right after land transfer) did not pass the significance test. Consequently, the indicator system for surrounding villagers’ willingness to transfer out the operational rights of farmland in resettlement areas is constructed, consisting of 11 indicators. The specific details are shown in Table 7.

5.2. Coupling Coordination Analysis of Land Supply and Demand Intentions

Based on the indicator screening results in Table 6, a land transfer-in demand evaluation index system for migrants was constructed from four criterion levels: individual and household characteristics, farmland resource endowments, external environmental characteristics, and psychological characteristics, with a total of eight indicators. The indicators were then weighted, and the comprehensive evaluation coefficients were calculated. The results are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Weighted and comprehensive evaluation table for migrants’ land transfer-in demand indicators.

Based on the indicator screening results in Table 7, a land transfer-out supply evaluation index system for surrounding villagers was constructed from four criterion levels, individual and household characteristics, farmland resource endowments, external environmental characteristics, and psychological characteristics, with a total of 11 indicators. The indicators were then weighted, and the comprehensive evaluation coefficients were calculated. The results are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Weighted and comprehensive evaluation table for farmland transfer-out supply by surrounding villagers in the resettlement area.

In the overall analysis, the land transfer-in demand evaluation index for the total system is 0.3711, and the land transfer-out supply evaluation index is 0.1586. Both systems’ evaluation indices are relatively low. Comparing the two, > , meaning that the land transfer-in demand index is higher than the land transfer-out supply index. According to Table 4, this suggests that the land transfer-out supply is lagging, indicating that the demand for land transfer by migrants in the SZ resettlement area of BS City exceeds the local supply of land for transfer. The system’s coupling degree is 0.9160, indicating a high level of coupling. Although the two systems can theoretically form a good match, the coupling coordination degree is 0.4925, which falls into the “low-level coordination” category. This indicates that while there is a strong coupling relationship between the two systems, their coordinated development is not ideal in practice due to various influencing factors, leaving significant room for improvement. It is necessary to analyze and adjust the factors affecting both transfer-in willingness and transfer-out willingness to enhance the overall coordination and transfer efficiency.

5.3. Discussion

The transfer-in intentions and supply of land in the resettlement area exhibit a high degree of coupling, with both parties demonstrating clear intentions and strong mutual influence. Migrants, after entering the resettlement area through “landless resettlement”, obtain farmland management rights from surrounding villagers via land transfer, which not only expands their livelihood options but also effectively reduces idle farmland resources in the vicinity, achieving optimized resource allocation [54]. Meanwhile, the income generated from land transfer incentivizes villagers to further participate in land transfers, with the increased supply, in turn, stimulating the demand from migrants, forming a dynamic supply–demand balance. However, despite the high coupling of transfer-in and transfer-out intentions, the actual coordination level remains low, indicating barriers to matching the intentions of both parties. The following sections will discuss the reasons for these coordination barriers from the perspectives of migrants’ farmland transfer-in intentions and surrounding villagers’ farmland transfer-out intentions.

The comprehensive evaluation of migrants’ farmland transfer-in intentions shows that external environmental factors have the highest weight coefficient (0.7787), while individual characteristics (0.0486) and psychological factors (0.0593) have relatively lower weight coefficients, indicating that migrants have a strong reliance on government policy support and lack intrinsic motivation [55]. Resource dependence theory suggests that individuals or organizations tend to rely on external support to meet their needs when facing a shortage of critical resources [56]. For landless resettled migrants, access to land resources is essential for sustaining their livelihoods. However, due to limited economic resources and restricted means of resource acquisition, migrants are unable to effectively obtain land through their own means and thus are more reliant on government policy support [57]. Survey data indicate that only 33.46% of migrants in the resettlement area have a high level of community integration (X15), showing limited social interaction with surrounding villagers, low levels of integration, and a lack of trust and effective communication channels [58]. This exacerbates information asymmetry in land transfer, as migrants have limited knowledge about surrounding villagers’ land availability, while villagers lack a clear understanding of migrants’ needs, making it difficult to achieve effective coordination in land transfers.

The comprehensive evaluation of farmland transfer-out intentions among surrounding villagers in the resettlement area shows that farmland resource endowment has the highest weight coefficient (0.3284), indicating that the quality and quantity of land resources are key factors influencing villagers’ transfer-out intentions. External environmental characteristics rank second (0.2837), demonstrating that government policy support and collective economic development play a significant role in shaping villagers’ land transfer decisions. Psychological characteristics follow (0.2660), highlighting the continued importance of villagers’ psychological cognition and trust in policies, while individual endowment has the lowest weight coefficient (0.1220), suggesting that personal attributes have a weaker influence on transfer-out intentions. In the context of the resettlement area, the government has concentrated large tracts of land for collective transfer to support projects such as orchid nurseries and oil tea plantations. Villagers prefer to transfer high-quality land to collective economic projects to secure more stable returns, while lower-quality, fragmented sloped land is more likely to be transferred to migrants. This preference reflects the villagers’ emphasis on land resource endowment and their uncertainty regarding the land management capabilities of individual migrants [59]. In contrast, psychological characteristics remain important, as villagers’ trust in policy support and land rights protection influences their risk assessment and confidence. Although this trust in land rights protection reduces concerns about migrants, it still leads villagers to prioritize collective transfers, limiting migrants’ access to land management rights. From the perspective of the theory of planned behavior, surrounding villagers’ land transfer-out decisions are still significantly driven by subjective intentions [60]. According to this theory, behavioral intentions are shaped by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. Farmland resource endowment and external environmental characteristics directly influence villagers’ attitudes toward transfer benefits and policy assurances, while psychological characteristics reflect villagers’ understanding of land transfer policies and rights protection. This understanding affects their sense of behavioral control and confidence in participating in land transfer, ultimately determining their transfer-out choices [61].

From a sustainable development perspective, this study further underscores that establishing an effective land transfer mechanism not only optimizes resource allocation and promotes sustainable development within resettlement areas and their surrounding regions but also provides valuable insights for poverty alleviation migration projects in other countries. Through land transfer, villagers gain additional economic benefits and improved living conditions [62], thereby supporting the goals of poverty reduction (SDG 1) and economic growth (SDG 8). Internationally, the land transfer mechanism highlighted in this study offers important guidance for addressing land resource access issues in poverty alleviation migration projects. Moreover, the rational development of idle land aligns with ecological protection goals (SDG 15), which are especially relevant for sustainable land use in ecologically fragile regions [63], such as karst areas. This sustainable land-sharing model aids in balancing economic and environmental benefits within China’s poverty alleviation resettlement areas [64]. It also serves as a practical reference for countries or regions facing similar resource constraints, illustrating how land leasing can optimize land resource allocation, lower barriers to land access for impoverished populations, and improve income and livelihoods in poverty alleviation migration projects.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study examines the land transfer intentions of migrants and surrounding villagers in the SZ resettlement area of Guangxi by systematically analyzing the coupling coordination relationship between migrants’ land transfer-in intentions and surrounding villagers’ land transfer-out intentions and verifying the practical value of the “Shared Land Resource Model” around the resettlement area. The following three main conclusions were drawn: First, there is a strong coupling between migrants’ land demand intentions and the land supply intentions of surrounding villagers, indicating a high level of consistency in supply–demand relations. However, the actual coordination in the transfer process is limited, constraining resource allocation efficiency and preventing land transfer from fully leveraging shared resources. Second, the evaluation of migrants’ land transfer-in intentions shows that external environmental factors have the greatest influence (weight coefficient of 0.7877), while individual characteristics (0.0486) and psychological factors (0.0593) have relatively lower weight coefficients, suggesting that migrants mainly rely on government policy support and lack intrinsic motivation to independently acquire land resources. Finally, the farmland transfer-out willingness of surrounding villagers in the resettlement area is most influenced by farmland resource endowment (weight coefficient of 0.3284), while the impact of individual endowment factors is the smallest (weight coefficient of 0.1220). These conclusions hold significant implications for land management in China’s poverty alleviation resettlement areas and offer valuable insights for other countries in planning poverty alleviation migration projects. By optimizing land transfer mechanisms, countries can more effectively promote resource sharing and allocation in poverty alleviation efforts, supporting migrants’ economic integration and enhancing livelihood stability and, thereby, providing practical and theoretical guidance for similar international projects. Based on these findings, this study proposes the following three recommendations.

Firstly, fostering intrinsic motivation among migrants is essential to enhancing the sustainability of poverty alleviation migration projects. Countries should implement policy measures that provide agricultural skills training, entrepreneurial support, and microcredit to migrants, thereby strengthening their productive capacity and economic self-sufficiency and helping them achieve long-term livelihood improvement in new environments. This approach not only reduces migrants’ dependency on government assistance but also offers innovative pathways for livelihood development within migrant communities in poverty alleviation projects worldwide.

Secondly, to safeguard the land rights of surrounding residents during land transfer processes, countries should emphasize fairness and the protection of rights in land-sharing projects. Establishing standardized land lease contracts that clearly define the rights and obligations within land transfer arrangements can ensure that villagers’ economic interests are fully protected throughout the transfer period. Additionally, enhancing communication between migrants and local residents will foster security and the long-term assurance of rights for villagers in land-sharing projects. This protection framework provides a valuable reference for other nations seeking to increase land transfer participation and improve relationships between migrants and local communities within poverty alleviation initiatives.

Finally, developing a robust land resource-sharing model is crucial in sustainable development. Countries should promote the establishment of systematic land transfer management and visualized support platforms within poverty alleviation migration projects. Encouraging eco-friendly agricultural practices will support balanced economic growth and environmental protection, ensuring both efficiency and sustainability in resource allocation.

7. Limitations and Prospects

Despite this study’s systematic analysis of the coupling coordination relationship between the land transfer-in intentions of migrants and the land transfer-out intentions of surrounding villagers in the SZ resettlement area through field surveys, there are still some limitations. First, the survey data used in this study came from the SZ resettlement area, with a relatively limited sampling area, which cannot fully reflect the land transfer models and characteristics of different types of resettlement areas nationwide. Therefore, the generalizability of the research results is limited. Future studies can expand the survey scope to include more resettlement areas and conduct comparative analyses of land transfer mechanisms in different regions to further verify the applicability and generalizability of the research conclusions.

Secondly, this study focused on exploring the land transfer intentions on both the supply and demand sides, analyzing in depth the key factors affecting the land transfer intentions of migrants and surrounding villagers. However, this study did not address specific land transfer behaviors and practical issues during the transfer process, such as the signing of land transfer contracts, changes in land use, and the achievement of economic and social benefits. Therefore, future research can further examine the relationship between transfer intentions and actual behaviors, track the long-term effects of land transfers, and evaluate the contribution of land transfers to the sustainable development of resettlement areas.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.C.; methodology, K.Z.; software, M.L.; validation, L.Y.; formal analysis, Z.C. and K.Z.; investigation, L.Y. and M.L.; resources, Z.C.; data curation, K.Z. and M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, L.Y. and K.Z.; writing—review and editing, Z.C.; visualization, L.Y.; supervision, Z.C.; project administration, Z.C.; funding acquisition, Z.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Project No. B240207112) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Project No. B240207032).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that this research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. Statistical Communiqué of the People’s Republic of China on National Economic and Social Development in 2023. China Stat. 2024, 3, 4–21. [Google Scholar]

- China Council for International Cooperation on Environment and Development. “2013 China Human Development Report” released in Beijing. Soc. Sci. Manag. Rev. 2013, 3, 89. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.; Luo, X.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J. Measuring the impact of the multiple cropping index of cultivated land during continuous and rapid rise of urbanization in China: A study from 2000 to 2015. Land 2021, 10, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zeng, W.; Liu, Z. Farmer heterogeneity and land transfer decisions based on the dual perspectives of economic endowment and land endowment. Land 2022, 11, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Measures for the Administration of Transfer of Rural Land Management Rights. Gaz. State Counc. People’s Repub. China 2021, 11, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, W.; Luo, K. Comprehensively promote rural revitalization and accelerate the construction of an agricultural power: A theoretical interpretation of the 2023 “Central Document No. 1”. Teach. Exam. 2023, 25, 46–50. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Zhang, W. The Impact of Land Transfer on Sustainable Agricultural Development from the Perspective of Green Total Factor Productivity. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, K.; Zuo, T. Spatial reconstruction under collaborative governance. China Rural Watch 2019, 2, 134–144. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, T.; Zhao, S.; Yi, J. Livelihood capitals and livelihood resilience: Understanding the linkages in China’s government-led poverty alleviation resettlement. Habitat Int. 2024, 147, 103057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. Research on risk assessment of landless resettlement areas for ecological immigrants in Ningxia. Reg. Res. Dev. 2016, 35, 175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Li, J.; Ren, L.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Li, S. Exploring livelihood resilience and its impact on livelihood strategy in rural China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 150, 977–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y. Research on the sustainable livelihoods of relocated people for poverty alleviation: A case study of Bama Yao Autonomous County, Guangxi. J. Southwest Univ. Natl. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2019, 40, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, W. Analysis of the willingness of residents in reservoir resettlement areas to transfer land based on the logistic model: A survey of resettlement areas in Sichuan, Hunan and Hubei. Resour. Sci. 2011, 33, 1178–1185. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.L.; Wang, J.; Lin, R.R. Outlook for China’s rural collective land system reform: Reviews from “Roundtable Forum for Land Policy and Law 2014”. China Land Sci. 2014, 28, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Rodríguez, S.E. Research on the Interaction Mechanism between Land System Reform and Rural Population Flow: Europe (Taking Spain as an Example) and China. Land 2024, 13, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wang, P. Rural land transfer: Current situation, problems and countermeasures. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2008, 2, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Q.; Lin, H. Research on land transfer model to promote poverty reduction. Yunnan Soc. Sci. 2018, 4, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, M. The influence of household structure on farmers’ willingness to farmland transfer: An empirical analysis based on SEM model. China Land Sci. 2019, 33, 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Nie, J. Elderly care dependence, life cycle and farmland transfer: An empirical analysis of factors affecting the willingness of rural elderly to transfer farmland. J. Jinan Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 29, 124–133+159–160. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yi, Y. The impact of welfare compensation for industrial and commercial capital going to the countryside on farmers’ willingness to transfer land. J. Southwest Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2022, 48, 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, F. Land development right and collective ownership in China. Post-Communist Econ. 2013, 25, 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, S.; Yuan, W. Study on the influence of government trust on the will of farmland transfer and its mechanism on the background of rural revitalization. J. Beijing Adm. Coll 2018, 4, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, W.; Chen, F.; Tan, Y. The effect of grain production purpose on the disparity of farmers’ land transferring willingness price. Resour. Sci. 2017, 39, 1844–1857. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Jayne, T.S. Land rental markets in Kenya: Implications for efficiency, equity, household income, and poverty. Land Econ. 2013, 89, 246–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Hu, M. On perception of farmland ownership and its influence on peasants’ willingness in farmland circulation—An empirical study of 483 peasant households in two counties of hubei. J. South-Cent. Minzu Univ. Soc. Sci. 2018, 38, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Adenuga, A.H.; Jack, C.; McCarry, R. The case for long-term land leasing: A review of the empirical literature. Land 2021, 10, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Investigation on the impact of land transfer on farmers’ income in Shandong Province. Res. World 2015, 9, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, A.; Okamoto, M. Adjustment of tenanted farmland to consolidate large-sized paddy plots. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Irrig. Drain. Reclam. Eng. 2002, 2002, 375–381. [Google Scholar]

- Marks-Bielska, R. Factors shaping the agricultural land market in Poland. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradfield, T.; Butler, R.; Dillon, E.J.; Hennessy, T. The factors influencing the profitability of leased land on dairy farms in Ireland. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dramstad, W.E.; Sang, N. Tenancy in Norwegian agriculture. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 946–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavorotin, E.; Gordopolova, A.; Tiurina, N.; Pototskaya, L. Differentiation of rent for agricultural-purpose land. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2019, 19, 691–698. [Google Scholar]

- Fedchyshyn, D.; Ignatenko, I.; Shvydka, V. Economic and legal differences in patterns of land use in Ukraine. Amazon. Investig. 2019, 8, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, T.W. The economics of leasing. J. Leg. Anal. 2020, 12, 221–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoyneva, D. Land market and e-services in Bulgaria. Agric. Econ.-Zemed. Ekon. 2007, 53, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wästfelt, A.; Zhang, Q. Keeping agriculture alive next to the city–The functions of the land tenure regime nearby Gothenburg, Sweden. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbord, M.; Bjørkhaug, H.; Burton, R.J.F. Drivers of change in Norwegian agricultural land control and the emergence of rental farming. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 33, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.W.; Akram, N.; Hongshu, W.; Andleeb, S.; ur Rehman, K.; Kashif, U.; Mehmood, A. Impact of land use rights on the investment and efficiency of organic farming. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Li, C.; Li, S. Subsequent support policies, resource endowment and livelihood risks of relocated farmers: Empirical evidence from Shaanxi Province. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, S. Policy orientation and strategic focus of follow-up support for poverty alleviation relocation. Reform 2020, 9, 118–127. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, C.; Chen, Q.; Feng, Q.; Zhu, M.; Tang, F.; Wu, X.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, F.; et al. Analysis of the evolvement of livelihood patterns of farm households relocated for poverty alleviation programs in ethnic minority areas of China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, C.; Chen, L. The impact of land transfer policy on sustainable agricultural development in China. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Xu, J.; Li, J. The influence of poverty alleviation resettlement on rural household livelihood vulnerability in the western mountainous areas, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Li, J.; Cui, Y. Does Non-Farm Employment Promote Farmland Abandonment of Resettled Households? Evidence from Shaanxi, China. Land 2024, 13, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, F.; Huang, C.; Song, X.; Wang, B.; Ma, H.; Wang, P. The United Nations 2030 Sustainable Development Goals framework and China’s response strategy. Adv. Earth Sci. 2018, 33, 1084–1093. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Jin, X.; Wu, K.; Han, B.; Sun, R.; Jiang, G.D.; Zhou, Y.K. Evaluation of the support capacity of land use system for regional sustainable development: Methods and empirical evidence. J. Nat. Resour. 2022, 37, 166–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Guo, Y.; Dang, H.; Zhu, J.; Abula, K. The Second-Round Effects of the Agriculture Value Chain on Farmers’ Land Transfer-In: Evidence from the 2019 Land Economy Survey Data of Eleven Provinces in China. Land 2024, 13, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z. Study on Factors Influencing Non-agricultural Employment of Relocated Farmers under the Livelihood Resilience Framework: Based on a Survey in Kizilsu Kirghiz Autonomous Prefecture, Xinjiang. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2020, 34, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Du, W. Study on Rural Homestead Exit Willingness Based on the Probit Binary Choice Model. J. Sichuan Norm. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2017, 44, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Liu, J. The Coupling and Coordination of Urban Modernization and Low-Carbon Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, G. Analysis of the spatiotemporal coupling coordination of the “new three transformations” of megacities: A case study of China’s top ten cities. Geogr. Sci. 2013, 33, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Kong, W.; Ren, L.; Zhi, D.; Dai, B. Misunderstandings and corrections of domestic coupling coordination model. J. Nat. Resour. 2021, 36, 793–810. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, G.; Liang, B.; Ye, T.; Zhou, K.; Sun, Z. Exploring the Coordinated Development of Smart-City Clusters in China: A Case Study of Jiangsu Province. Land 2024, 13, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Sun, B.; Liu, C.; Yi, H. Evaluation of the effectiveness of poverty alleviation relocation policy: Based on micro-tracking data of poverty-stricken households in three counties of S Province. Econ. Sci. 2023, 3, 185–204. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Xie, L.; Zheng, X. Across a few prohibitive miles: The impact of the Anti-Poverty Relocation Program in China. J. Dev. Econ. 2023, 160, 102945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. External control of organizations—Resource dependence perspective. In Organizational Behavior, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 355–370. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, F. Residential relocation under market-oriented redevelopment: The process and outcomes in urban China. Geoforum 2004, 35, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Guerrero, J.E.; Rueda López, R.; Luque González, A.; Ceular-Villamandos, N. Indigenous peoples, exclusion and precarious work: Design of strategies to address poverty in indigenous and peasant populations in Ecuador through the SWOT-AHP methodology. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Wei, C.; Xie, D.; Liu, J. Farmers’ responses to land transfer under the household responsibility system in Chongqing (China): A case study. J. Land Use Sci. 2007, 2, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Zhou, W.; Guo, S.; Deng, X.; Song, J.; Xu, D. Effect of land transfer on farmers’ willingness to pay for straw return in Southwest China. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 369, 133397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, F.; Spoor, M.; Ma, X.; Shi, X. Perceived land tenure security in rural Xinjiang, China: The role of official land documents and trust. China Econ. Rev. 2020, 60, 101038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, J. Comprehensive land consolidation as a development policy for rural vitalisation: Rural In Situ Urbanisation through semi socio-economic restructuring in Huai Town. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 93, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, M.; Lu, J.; Zhou, Q.; Ma, W. Evaluation of ecological city and analysis of obstacle factors under the background of high-quality development: Taking cities in the Yellow River Basin as examples. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 118, 106771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, X.; Zuo, J. The effect on poverty alleviation and income increase of rural land consolidation in different models: A China study. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).