Abstract

As a key element of spatial governance, marine protected areas (MPAs) have been increasingly established in various countries, with lessons learned from terrestrial environmental protection. Nevertheless, the development of MPAs in China continues to trail behind that of their land-based counterparts. Here, following the leverage points perspective of sustainability interventions, this article presents a systematic analysis of the governance and evolution of China’s MPAs, identifying key areas for improvement. The analysis encompasses the number, effectiveness, legal framework, governance structure, value, and paradigm of MPAs, and highlights the associated governance challenges facing China. Drawing on relevant experiences from the United States, Australia, and the European Union, the article offers valuable insights for informing China’s future MPA strategies. The study concludes that while China has made significant progress in the development of MPAs, further efforts are needed, including paradigm shifts, refinement of the legal system, optimization of governance structures, and enhancement of MPA effectiveness.

1. Introduction

The oceans, encompassing nearly three-quarters of the Earth’s surface, harbor rich biodiversity and furnish essential ecosystems that yield food and other vital resources for human sustenance. Furthermore, they function as the planet’s largest carbon sink, underscoring their critical role in mitigating climate change. In recognition of their importance, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 14 champions the conservation and sustainable utilization of the world’s oceans, seas, and marine resources to foster sustainable development. Marine spaces are the maritime regions across the world under national jurisdiction, which are vast in area, abundant in resources, and hold considerable ecological importance. However, past studies on spatial governance have predominantly focused on terrestrial spaces, leaving marine spaces largely underrecognized for the whole spatial sustainability.

In fact, the idea and movement of sustainable development kind of originated from the marine sector, interestingly. Back in the 1950s, with the decline in catch or effort ratios in various fisheries around the world, the need to devise methods to manage international fishery conflicts and protect marine environments at the global level became imperative [1], prompting the development of the concept of protecting specific areas and habitats, and eventually leading to the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) as a zoning management tool to foster marine ecological conservation and sustainable resource utilization. In 2003, the Ad Hoc Technical Expert Group on Marine and Coastal Protected Areas of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) defined a marine and coastal protected area as “any defined area within or adjacent to the marine environment, together with its overlying waters and associated flora, fauna, and historical and cultural features, which has been reserved by legislation or other effective means, including custom, with the effect that its marine and/or coastal biodiversity enjoys a higher level of protection than its surroundings” [2]. In the face of mounting threats from marine pollution and climate change, establishing a robust and well-managed network of MPAs has emerged as a vital strategy for bolstering the conservation of marine ecosystems.

The establishment of MPAs draws on the experience of terrestrial conservation, leveraging management practices and lessons learned from land-based protected areas to inform the governance of MPAs. The concept of protected areas originated in the 19th century in countries such as Australia, Canada, South Africa, and the United States, and by the 20th century, it had gained global traction [3]. For decades, protecting rare and endangered species, as well as preserving their habitats or areas of exceptional natural beauty, has proven to be an effective conservation measure on land. According to Article 2 of the CBD, a protected area is defined as a geographically defined area which is designated or regulated and managed to achieve specific conservation objectives. However, protected areas should not be isolated from their surroundings; instead, they should form part of a network of protected areas that integrate into the broader environment, promoting conservation and sustainable use of land and water resources [4]. The interconnectedness and interdependence of terrestrial and marine ecosystems are underscored by the complex exchanges of matter and energy between them. Notably, a significant portion of marine pollution originates from land-based sources, with an estimated 70% to 80% of plastic pollution in the ocean, by weight, being transported from land to sea through rivers or coastal areas [5]. The effective conservation of coastal protected areas hinges on the integration of MPAs into a broader network of land–sea ecosystems, as the strong land–sea interactions and fluidity of seawater dynamics render isolated conservation efforts inadequate [6].

In particular, the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (KM-GBF) underscores the importance of establishing MPAs, reflecting the international community’s commitment to protecting marine biodiversity. The KM-GBF emphasizes the need to enhance the management effectiveness of MPAs, improve their representativeness and connectivity, and integrate them into broader marine spatial planning. It urges countries to strengthen marine conservation efforts, designating at least 30% of the ocean as protected areas, as well as using Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures to address the pressing challenges of marine biodiversity loss. The establishment of MPAs has emerged as a widely accepted consensus among nations in the context of global biodiversity governance and ocean governance. However, despite this broad agreement, the development of MPAs significantly lags behind that of terrestrial protected areas. Statistics reveal that only 8.3% of the world’s oceans are designated as MPAs, and most are either protected in name only or so loosely regulated that substantial harmful activities are allowed to continue within them [7], highlighting a pressing need to accelerate progress in marine conservation efforts.

China is home to one of the world’s most diverse marine ecosystems, with its waters supporting over 28,000 documented species—representing approximately 11% of global marine biodiversity [8]. However, as marine resources continue to be intensively exploited and utilized, a range of pressing environmental issues has emerged, including accelerating marine environmental degradation, expanding areas of ecosystem decline, and widespread loss of coastal wetlands [9]. Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, the country has prioritized the development of a marine ecological civilization and the protection of the marine environment. MPAs have emerged as a crucial tool in managing the marine ecosystem, playing a vital role in safeguarding the health of the marine environment, maintaining ecosystem balance, and promoting the sustainable use of marine resources [10].

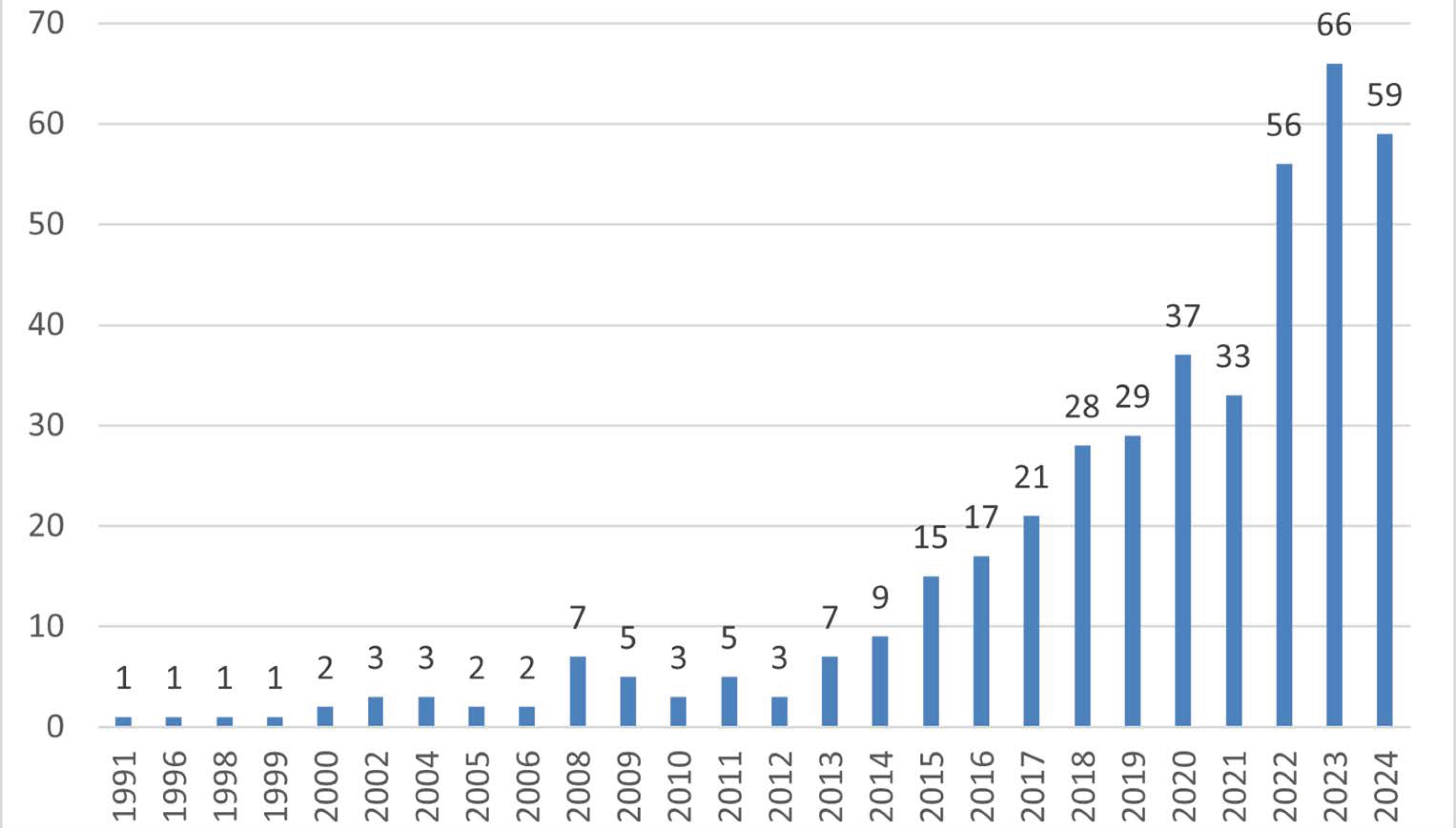

Regarding the literature search, by using the terms “Marine Protected Areas” in conjunction with “China” to form the query [“Marine Protected Areas” AND “China”], a total of 416 articles were retrieved from the Web of Science Core Collection. It shows that studies on China’s MPAs have gradually developed since the 1990s, with the number of relevant articles increasing annually (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of articles on research of China’s MPAs.

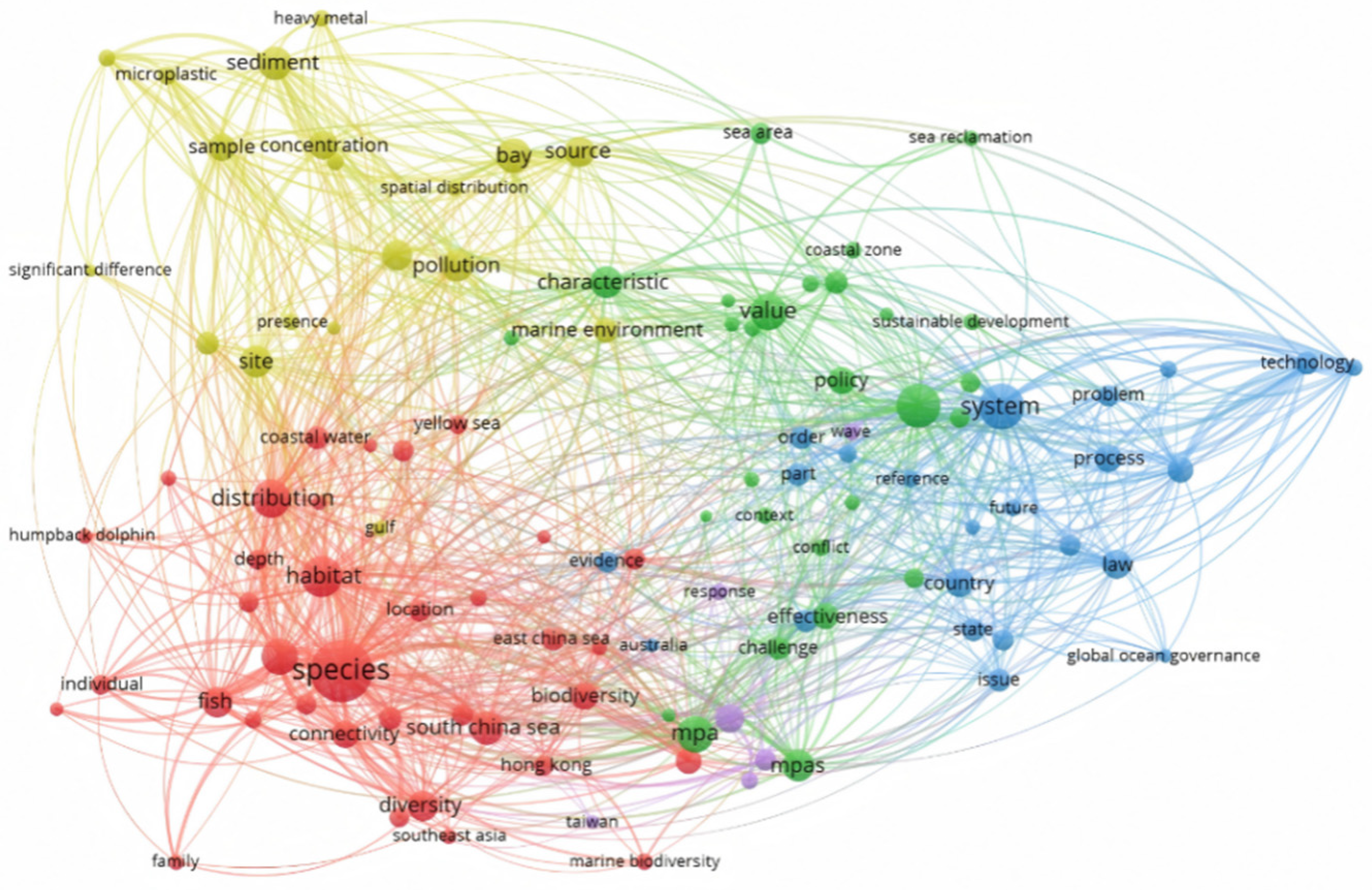

Additionally, VOSviewer was utilized to construct and visualize keyword co-occurrence networks for both Marine Protected Areas and China, allowing for the deduction of primary research themes from the interlinking patterns of keywords [11]. A comprehensive analysis of 407 articles from 2004 to 2024 reveals that the research focuses on exploring the value and role of MPAs in conserving fish and other biological resources, protecting coral reefs, addressing climate change, and providing ecosystem services. Additionally, the studies also examine the management models and development of MPAs (Figure 2). For example, Qiu et al. analyzed the characteristics of China’s system of MPAs, suggesting that it is characterized by decentralized designation and management [12]. Hu et al. analyzed the development process of China’s MPAs, arguing that China implemented unified management of MPAs after its institutional reforms in 2018, which made new top-level design possible [13]. Zhao et al. [14] and Zeng et al. [15] indicated that the major issues hampering management effectiveness include multiple management agencies, lack of systematic planning for classification and zoning, and limited survey data. Some studies emphasize the involvement of stakeholders in MPA design, implementation, and management [16,17,18,19]. However, in the context of China’s efforts to promote integrated land and sea development and build a natural protected area system, research on systematically optimizing the governance of MPAs remains insufficient. This is particularly true regarding the connections and priorities between different elements and leverage points within the governance framework. To address this gap, a deeper understanding of how to intervene effectively in complex systems is essential.

Figure 2.

Network analysis of keyword co-occurrence on MPAs and China.

In this regard, Meadows’ framework of 12 types of leverage points provides valuable governance insights for understanding where and how to intervene in complex systems to bring about transformative changes [20]. Building on this, Abson et al. propose four realms of leverage—Parameters, Feedback, Design, and Intent—ranging from shallow to deep leverage points. They argue that Design and Intent, as deep leverage points, have great potential but are under-researched [21]. Followingly, Fisher and Riechers expanded this framework into four realms of leverage for sustainability interventions: Material, Processes, Design, and Intent [22]. Tools in the realm of shallow leverage points focus more on past and present system states, while tools in the realm of deep leverage points often use participatory and transdisciplinary approaches across different academic disciplines and sources of knowledge [23]. Guided by this leverage points perspective, this research conducts a comprehensive examination of China’s MPA governance, including a case study of the Dalian Spotted Seal National Nature Reserve, an analysis of the Ministry of Ecology and Environment’s ecological assessments of 10 national marine nature reserves, and an evaluation of the current status of sea-related national parks, either established or under development. Furthermore, the research undertakes a comparative analysis of China’s MPA governance model with those of the United States, Australia, and the European Union, and provides recommendations for the integrated optimization and governance of China’s MPAs.

2. Analytical Framework Based on the Leverage Points Perspective

The leverage points perspective offers a valuable framework for understanding and addressing environmental governance challenges by emphasizing systemic and sustainable interventions. By shifting the focus from short-term fixes to transformative changes, this approach provides a powerful tool for tackling complex environmental issues. It enables the examination of interactions between shallow and deep system changes, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the dynamics at play. Scholars have successfully applied the leverage points perspective to study various issues related to environmental governance [22]. For instance, Bartkowski and Bartke regarded the determinants of farmers’ behavior and decision-making regarding soil management as leverage points for soil governance [24]. Building on this foundation, this article explores the development, challenges, and improvement of China’s governance of MPAs through the leverage points perspective.

As a crucial tool for managing the marine ecological environment, MPAs play a vital role in conserving marine ecosystems and promoting the sustainable utilization of marine resources. China’s marine conservation efforts commenced in 1963 with the establishment of its first MPA on Snake Island in Dalian, followed by the designation of Snake Island and the adjacent Old Iron Mountain as a national-level nature reserve by the State Council in 1980. Over the years, China has made significant strides in developing its MPA network, which now forms a comprehensive system centered on marine ecological environment protection [25]. Drawing on the research experience of existing literature on environmental governance from the leverage points perspective, this article identifies leverage points in MPA governance, ranging from shallow to deep (See Table 1). By examining specific leverage points related to China’s MPA governance, the article prioritizes actions that address deeper, systemic issues rather than superficial fixes. The identified leverage points include surface-level factors, such as the number and area of MPAs, as well as their role and effectiveness. Middle-level leverage points comprise the legal system and policies for MPA governance, as well as the protected area governance structure, including government departments and community participation. Deep leverage points primarily involve the value and paradigm of MPA governance, which underpin the overall approach to marine conservation.

Table 1.

A leverage points perspective on MPA governance.

3. The Number and Effectiveness of MPAs in China

3.1. Development Progress and Increased Quantity of MPAs in China

China’s Marine Environmental Protection Law has established the legal framework for marine nature reserves and marine special protected areas, defining their respective legal status and establishment conditions. Marine nature reserves prioritize the conservation of rare, natural, and pristine ecosystems, focusing on three main categories: marine biological species, marine and coastal ecosystems, marine natural relics and non-biological resources. In contrast, marine special protected areas strive for a balance between conservation and development, promoting the sustainable use of marine resources while protecting the environment. These areas are categorized into four types: marine parks, marine ecological protection areas, marine resource protection areas, and marine special geographical condition protection areas (See Table 2), with designations at both national and local levels [26,27]. Currently, China has established a comprehensive network of MPAs, effectively covering all coastal provincial administrative units across the mainland [28].

Table 2.

Categories of China’s MPAs under the Marine Industry Standard of China (HY/T 117-2008) [29].

MPAs should be established and managed through a zoning system that reflects the unique characteristics of the marine environment and socio-economic conditions. This will help to create a spatial development framework that achieves a balance between human activity, economic growth, and environmental sustainability [30]. Unfortunately, some MPAs have been established without adequate data, resulting in mismatches between actual sea use and the intended functional zones. This has hindered the enforcement of strict regulations and compromised the effective protection of the primary conservation targets within these areas [31]. Notably, some important marine ecosystems and ecological function areas remain outside of designated protection zones [28].

According to the White Paper on China’s Marine Ecological Environment Protection, published in July 2024, China has made significant progress in marine conservation, with the establishment of 352 marine nature reserves covering an impressive 93,300 km2 of ocean area. Furthermore, five national marine park candidate areas are currently under development, laying the foundation for a robust, well-structured, and functional MPA governance system [32]. However, despite these efforts, China’s MPA construction still lags behind its international commitments. The Overall Plan for Ecological Civilization System Reform, issued by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council in 2015, explicitly stated China’s intention to “actively participate in global governance”, marking a shift towards China taking a proactive role in assuming governance responsibilities and driving global development [33]. As the host of the 15th Conference of the Parties to the CBD [34], China played a key role in promoting the adoption of the KM-GBF. Nevertheless, China’s MPAs account for only 4.1% of its total jurisdictional sea area by the end of 2019 [35], falling short of the target set by the KM-GBF, which emphasizes the importance of MPAs and Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures in meeting Target 3 criteria [36]. This disparity highlights the need for China to strengthen its planning and implementation of MPAs.

3.2. Case-Based Analysis of the Effectiveness of MPAs in China

MPAs vary in their level of protection, ranging from comprehensive to minimal, with some existing only on paper, and lacking effective implementation [37]. Enhancing the effectiveness of MPAs is a global imperative [38]. Following years of development, China’s MPA planning and implementation efforts have yielded significant outcomes, with the construction of marine nature reserves playing a crucial role in promoting the sustainable development of the oceans and conserving biodiversity. This article selects the largest national-level marine nature reserve in China, the Dalian Spotted Seal National Nature Reserve, as a typical case to analyze the effectiveness of the marine reserve and its protection of marine biological species, as well as the challenges it faces. The Dalian Spotted Seal National Nature Reserve is located near Changxing Island in Fuzhou Bay, 20 km northwest of Dalian City in Liaodong Bay, Bohai Sea [39]. It was established in 1992 with the approval of the Dalian Municipal Government and was upgraded to a national-level nature reserve in 1997. The reserve covers an area of 560,000 hectares, with a coastline of approximately 370 km, almost encompassing all the coastal waters of Dalian City within Liaodong Bay. Its primary conservation target is the spotted seal and its associated ecological habitat. Notably, the reserve was designated as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention in January 2002 [40].

Historically, the population of spotted seals in Liaodong Bay was estimated to be approximately 7000–8000 individuals in the 1930s. However, excessive hunting between 1940 and 1970 led to a precipitous decline, with only 2269 seals remaining by 1979 [41]. In response to this alarming trend, Liaoning Province enacted legislation in 1983 that strictly prohibited the hunting of spotted seals. Despite this conservation effort, the population continued to decline, and by 1992, there were fewer than 1000 spotted seals remaining [40]. The establishment of the Dalian Spotted Seal Nature Reserve in 1992 marked a pivotal moment in conservation efforts, and when combined with successful artificial breeding programs, the reserve contributed to the revival of the population. By 2006, the population of spotted seals had increased to an estimated 2000 individuals in the waters under China’s jurisdiction [42]. Subsequently, the population stabilized and exhibited signs of growth. A 2021 survey conducted by the National Forestry and Grassland Administration revealed a notable sighting of over 200 spotted seals at Ant Island’s reef and adjacent waters, representing the largest single observation of its kind in recent years for a concentrated haul-out site in Dalian waters [40].

Institutional design-level measures played a crucial role in the recovery of the spotted seal population, driven by two key factors. Firstly, the development of a comprehensive legal and regulatory framework has provided a solid foundation for conservation efforts. The State Council’s issuance of the “Outline of China Aquatic Biological Resources Conservation Action” (2006–2020) and the “China Biodiversity Conservation Strategy and Action Plan” (2011–2030) has been instrumental in this regard. Furthermore, the Liaoning Provincial People’s Government has introduced a series of local regulations, including the “Regulation of Liaoning Province on the Protection of Spotted Seals” (2007), the “Implementation Measures of Liaoning Province on the Protection of Key Protected Terrestrial Wild Animal Spotted Seals” (2018), and the “Plan of Liaoning Province on the Protection of Spotted Seals’ Population and Habitat” (2019). These regulations have effectively promoted the conservation work of the Dalian Spotted Seal National Nature Reserve, providing a robust legal framework for protection. Secondly, the Dalian Spotted Seal National Nature Reserve’s effective conservation measures have played a crucial role in the recovery of the spotted seal population. The reserve’s management agency has enforced stringent protection of the spotted seals’ habitats, including beaches and reefs, and implemented coastal zone and island vegetation restoration projects. Additionally, a comprehensive monitoring system has been established to track the spotted seal population’s size, distribution, and breeding patterns on a regular basis, providing valuable insights for conservation efforts [43].

The overarching objective of China’s MPA governance is to integrate land and sea management mechanisms through the enhancement and implementation of protected area systems, thereby continually improving the efficacy of marine ecological environment governance [32]. Nevertheless, the current governance effectiveness of China’s MPAs remains in need of improvement. A comprehensive assessment of the ecological environment of 10 national marine nature reserves, conducted by China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment in 2023, underscores this imperative. The results revealed that five reserves—Dalian Spotted Seal National Nature Reserve in Liaoning, Yellow River Delta National Nature Reserve in Shandong, Huidong Sea Turtle National Nature Reserve in Guangdong, Zhanjiang Mangrove National Nature Reserve in Guangdong, and Hepu National Nature Reserve in Guangxi—achieved a Grade I rating, signifying excellent ecological conditions. The remaining five reserves, including Yancheng Wetland Rare Bird National Nature Reserve in Jiangsu, Jiuduansha Wetland National Nature Reserve in Shanghai, Xuwen Coral Reef National Nature Reserve in Guangdong, Shankou Mangrove Ecological National Nature Reserve in Guangxi, and Beilunhe Estuary National Nature Reserve in Guangxi, received a Grade II rating, indicating satisfactory but not outstanding conditions (See Table 3) [44].

Table 3.

National marine nature reserves with Grade II rating in China’s ecological environment quality assessment in 2023 [44].

As revealed in the “Report on the Ecological Environment of China’s Oceans in 2023”, released by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, the primary challenges confronting the ecological environment of marine nature reserves include the incursion of the non-native species Spartina alterniflora, in addition to the diminution of live coral and mangrove populations. Originally native to the eastern seaboard of North America, Spartina alterniflora, a perennial grass species, was intentionally introduced to China in 1979 with the goals of enhancing sedimentation, conserving coastlines, and reducing wave-induced erosion [45]. However, Spartina alterniflora possesses high adaptability, strong interspecific competitiveness, and rapid reproduction characteristics [46], which have led to a high overlap with mangrove habitats in muddy tidal flats and wetlands. Not only does Spartina alterniflora compete with mangroves for survival space, but it also reduces the quality of microhabitats and the biodiversity of large benthic animals in mangrove forests [47].

The unique characteristics of MPAs, particularly their remoteness from land, exacerbate the challenges associated with monitoring and enforcement. Consequently, the level of marine environmental and resource surveying, monitoring, and research in these areas is inadequate, hindering the provision of stable, long-term technical support for marine ecological restoration and conservation management [48]. Furthermore, the coverage of protected areas in fragile ecosystems, such as coasts, coastal wetlands, and river estuaries, is insufficient due to competing economic development interests, resulting in inadequate protection efforts in these regions. Moreover, some national-level MPAs lack comprehensive management plans, and unresolved conflicts over sea use and resources among stakeholders persist. The effectiveness of law enforcement agencies is also compromised by the absence of specific legal authority to enforce laws and regulations [25].

4. Systems and Structure of China’s MPA Governance

4.1. Regulatory Framework for China’s Governance of MPAs

The legal framework and administrative measures governing national parks, nature reserves, marine special protected areas, geoparks, marine parks, and forest parks in China are multifaceted (See Table 4). To promote the development and governance of MPAs, China has established a comprehensive suite of laws and regulations, building on the foundation of the “Regulations of the People’s Republic of China on Nature Reserves”. Key legislation and administrative measures includes the “Marine Environment Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China”, “Measures for the Management of Marine Nature Reserves”, “Measures for the Management of Nature Reserves for Aquatic Animals and Plants”, “Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Management of Sea Area Use”, “Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Islands”, and “Measures for the Management of Marine Special Protected Areas”, which collectively provide a regulatory framework for the establishment and management of marine nature reserves, nature reserves for aquatic plants and animals, and marine special protected areas, as well as the use and management of sea areas and islands [12]. Furthermore, laws and regulations such as the “Fisheries Law of the People’s Republic of China”, “Regulations on the Protection of Aquatic Wild Animals”, “Regulations on the Propagation and Protection of Aquatic Resources”, “Cultural Relics Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China”, and “Regulations on the Prevention of Pollution Damage to the Marine Environment by Land-based Pollutants” have contributed to the development of MPAs from diverse perspectives.

Table 4.

Basic management system and institutions for various types of natural protected areas in China.

4.2. The Structure of China’s Governance of MPAs

In 2013, the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China marked a milestone in ecological conservation by introducing the concept of deepening ecological civilization reform and accelerating the establishment of an ecological civilization system [49]. Prior to these reforms, China’s MPAs were governed under a complex management framework that encompassed both departmental and hierarchical structures [50]. Specifically, marine special protected areas fell under the unified management of the former State Oceanic Administration, whereas marine nature reserves were overseen by the former Ministry of Environmental Protection. Meanwhile, the forestry, ocean, environment, agriculture, and land management departments each assumed sector-specific supervisory responsibilities. Following the release of the “Integrated Reform Plan for Promoting Ecological Progress” in 2015, the Communist Party of China Central Committee and the State Council jointly issued the “Plan for Deepening the Reform of Party and State Institutions” in 2018, thus initiating a comprehensive overhaul of China’s protected area management system and effectively promoting the development of MPAs. The unification of MPA management under the National Forestry and Grassland Administration represents a significant step toward overcoming the challenges posed by fragmented management structures [13]. Nonetheless, China continues to draw on a hierarchical management approach for MPAs, categorizing protected areas into national and local designations based on their significance, representativeness, and distinctiveness. The local designation is further stratified into three levels: provincial, municipal, and county, to foster a nuanced approach to marine conservation [28].

Prior to the 2018 State Council institutional reform, the government departments responsible for managing MPAs in China included the following: the Ministry of Environmental Protection, the Ministry of Land and Resources, the State Oceanic Administration, the Ministry of Agriculture, the State Forestry Administration, and various levels of local governments. Marine nature reserves were established with the approval of the State Council and different levels of local governments, while marine special protected areas were mainly established with the approval of the State Oceanic Administration. The establishment of nature reserves in China has proceeded without unified, coordinated top-level planning. Instead, various government departments have created their own reserves under their respective mandates, resulting in a national nature reserve classification system lacking both scientific rigor and systematic coherence. This fragmented approach has produced ambiguous and uncoordinated functional designations. Moreover, the piecemeal establishment of reserves by different departments has led to significant spatial overlap and redundancy, with approximately 49.8% of the country’s nature reserves exhibiting overlapping boundaries [51].

The 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China highlighted the need of reforming the ecological and environmental regulatory framework, developing a spatial planning system for land use and conservation, strengthening policies aligned with functional zoning, establishing a natural protection area system centered on national parks, and strictly preventing and penalizing activities that harm the ecological environment [52]. In March 2018, the State Council implemented institutional reforms by creating the Ministry of Natural Resources and assigning oversight of all marine and terrestrial protected areas to the new ministry and its subordinate agency, the National Forestry and Grassland Administration, also known as the National Park Administration. Concurrently, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment was formed, assuming the marine environmental protection responsibilities previously held by the State Oceanic Administration [53]. In June 2019, the General Office of the Communist Party of China Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council issued the “Guiding Opinions on Establishing a System of Natural Protected Areas with National Parks as the Mainstay” [49]. This policy formally integrated MPAs into the overarching national system of natural protected areas, designating the National Forestry and Grassland Administration as the supervisory and management authority for all types of natural protected areas, including MPAs. The document underscores the importance of “establishing a system of natural protected areas with national parks as the main body, categorized scientifically, laid out reasonably, protected effectively, and managed efficiently”. It further requires “conducting a comprehensive evaluation of existing natural protected areas, such as nature reserves, scenic spots, geological parks, forest parks, marine parks, wetland parks, glacier parks, grassland parks, desert parks, grassland scenic areas, and adjusting and classifying them according to their natural attributes, ecological values, and management goals, to gradually form a classification system of natural protected areas with national parks as the main body, nature reserves as the foundation, and various natural parks as supplements”. In 2022, China released its first national five-year plan for marine ecological environment protection, proposing comparable objectives and reflecting how the principles of ecological priority and green development now permeate the entire marine sector [35].

In addition to the government-led “top-down” governance approach, public participation in protected areas is also crucial. As a part of integrated coastal management, the promotion of MPAs should consider not only the protection of marine biodiversity and ecosystem functions, but also the sustainable use of marine resources and public interests [54]. Many of China’s MPAs have resident populations or are centers of intensive human activity. For instance, the Changdao National Marine Park includes fishing villages and communities within its boundaries; in 2024 alone, 5520 vessels were involved in fishing, aquaculture, tourism, and shipping within the park’s waters [55]. At present, community participation in MPA governance largely takes the form of public hearings and official announcements during the establishment of MPAs. However, mechanisms to ensure public involvement in the early stages, such as site application and selection, remain inadequate. The 2024 draft edition of China’s National Park Law similarly highlights the need for a community governance system in national parks, encouraging the inclusion of local residents, experts, scholars, and social organizations in the establishment, planning, management, and operation of these areas.

5. The Value and Paradigms of China’s MPA Governance

5.1. The Value of China’s MPA Governance

By prioritizing eco-environmental conservation, China has integrated ecological progress into its overall plan for marine development, adopting a well-conceived and sustainable approach to utilizing marine resources. Marine ecological civilization plays a crucial role in achieving China’s broader ecological civilization objectives, and the values underlying China’s MPA governance reflect the nation’s overarching environmental and developmental goals. China’s MPAs aim to protect critical marine habitats, endangered species, and unique ecosystems, which serve as sanctuaries that promote biodiversity and ecological balance. By safeguarding habitats such as coral reefs, mangroves, and seagrass beds, these MPAs enhance marine ecosystem resilience against both climate change and human activities. Despite China’s rapid economic growth and substantial government investments in biodiversity conservation, the country’s extensive territory, rich biodiversity, and sizeable conservation workload have led to insufficient protected area development and management, as well as funding shortages. Critical areas such as biodiversity surveys and monitoring, in-situ conservation, and ecosystem restoration urgently require more attention and support [56]. Furthermore, although the importance of biodiversity is increasingly acknowledged in China, evaluating the effectiveness of conservation efforts remains challenging due to the extended timeframe needed to observe tangible outcomes and the absence of standardized metrics. Beyond monitoring species populations statistically, there is a notable lack of consistent methods and criteria to assess other pivotal aspects of biodiversity conservation [57].

China prioritizes the integrated governance of the mountain–water–forest–farmland–lake–grassland–sand ecosystem, recognizing the interconnected and systematic nature of ecological systems. This holistic ecological perspective underscores the universal connections within ecosystems, highlighting the intrinsic relationships among their various components. At its core, this approach emphasizes the principle of universal connection rather than a whole-centered perspective [58]. Similarly, the ocean ecosystem constitutes a complex web of interactions between marine life and the marine environment, which mutually influence one another to maintain a dynamic equilibrium over time [59]. Consequently, the development of MPAs should be grounded in ecosystems or biogeographic regions [60], adopting an ecosystem-based approach that fosters cross-sectoral and interdisciplinary integrated marine management [61]. In 2000, the 5th Conference of the Parties to the CBD adopted Decision V/6, outlining 12 key principles for applying an ecosystem-based approach to conservation and management [62]. Subsequently, the 2006 annual report on Oceans and the Law of the Sea, submitted by the UN Secretary-General, provided a comprehensive overview of the ecosystem approach [63]. While noting the lack of an internationally agreed-upon definition, it describes the ecosystem approach as managing ecosystems based on the best available understanding of ecological interactions and processes, aiming to preserve their structure and function. Adopting this approach is essential for the effective management of MPAs and the development of MPA networks. Under its guidance, China’s MPAs must be further integrated and optimized to ensure sustainable and holistic conservation outcomes.

5.2. The Paradigms of China’s MPA Governance

A pressing challenge facing China’s governance paradigms for natural protected areas is the need for systematic integration of multiple, often fragmented areas. For example, Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park integrates Diaoluoshan National Forest Park, Jianfengling National Nature Reserve, and Limushan Provincial Nature Reserve, among others [64], covering a total area of 4269 km2. Of this total, 2331 km2 comprise the core protected area, while 1938 km2 fall under the general control area [65]. A similar need for integration exists in MPAs. China is currently planning five national park candidates related to coastal and marine environments, including Tropical Ocean, Yellow River Estuary, Liao River Estuary, Chang Island, and Nanji Islands [66]. For instance, the Yellow River Estuary National Park spans 352,291 hectares. Its main body incorporates eight natural protected areas, including the Shandong Yellow River Delta National Nature Reserve, Shandong Yellow River Delta National Geopark, and Shandong Yellow River Estuary National Forest Park; it also encompasses areas of ecological significance, such as spawning and nursery grounds for marine species. This park is divided into a core protected area of 184,103 hectares—all state-owned—and a general control area of 168,188 hectares containing agricultural land, scattered residential locations, educational and research facilities, and recreation sites [67]. Similarly, the Liao River Estuary National Park was formed by merging and optimizing the original Liao River Estuary National Nature Reserve with seven other protected areas, creating a more manageable and effective conservation region [68]. In another example, the Changdao National Park candidate area centers on the Changdao Marine Ecological Civilization Comprehensive Experimental Zone, encompassing 151 islands and their surrounding waters. This area includes nine existing protected sites—such as the Shandong Changdao National Nature Reserve, Changdao National Marine Park, Changdao National Geopark, and Changdao National Forest Park—along with the Changshanwei Marine Geological Relics Provincial Marine Special Protected Area. Moreover, it covers critical migration routes and habitats of species such as the spotted seal and the East Asian finless porpoise [69].

The development of national marine parks faces the dual challenge of coordinating both spatial planning and administrative authority. This process requires integrating management frameworks and institutional arrangements for various types of natural protected areas within park boundaries, such as marine parks, forest parks, and geological parks. Previously, these areas were managed by different departments according to specific functional requirements. Once incorporated into the natural protected area system, they must continue fulfilling their original functions [70]. In 2022, the Chinese National Forestry and Grassland Administration, National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Natural Resources, and Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs jointly issued the “Plan for Major Projects on the Construction of National Parks and Other Natural Protected Areas and the Protection of Wild Animals and Plants (2021–2035)”. The plan proposes completing the integration, consolidation, and optimization of natural protected areas and implementing a unified registration system for natural resources by 2025. By 2035, the spatial layout of natural protected areas is expected to be further optimized.

China has also introduced an ecological conservation red line system, which identifies areas with critically important ecological functions requiring strict, mandatory protection [71]. All marine natural protected areas and marine natural parks fall under this framework [72]. According to the management guidelines of the marine ecological conservation red line, core areas of marine nature reserves are strictly off-limits to human activities, mirroring the requirements for core areas under the marine nature reserve system. The general control areas of marine nature reserves and the entirety of marine nature parks permit only limited human activities that do not harm ecological functions, while prohibiting developmental and constructive uses. This further refines the management requirements for general control areas under the marine nature reserve system and the management requirements for marine nature parks [73]. Consequently, in terms of institutional alignment, the core areas of marine nature reserves are subject to both the marine nature reserve system and the marine ecological conservation red line system, ensuring stringent and mandatory protection. The general control areas of marine nature reserves and the entirety of marine nature parks, while adhering to their respective management requirements, must also ensure that human activities are kept within the limits that the ecosystem can sustainably withstand. Specifically, limited human activities are only permitted if they do not encroach upon the marine ecological conservation red line or cause harm to the marine ecosystem [74].

6. Ways Forward for Advancing China’s Governance of MPAs

6.1. Improving the Paradigms of China’s MPA Governance

Deep leverage points are the key to solving complex, entrenched problems and transforming systems over time, as they address the root causes of issues and can shift the dynamics of the entire system. Improving the paradigms of China’s MPA governance could focus on adopting a more comprehensive and holistic approach. Marine management in China is characterized by fragmentation, with multiple administrative bodies developing their own plans and standards for marine industry development and environmental protection. This lack of effective coordination hampers efforts to address the complex issues facing the marine environment. A case in point is the management of land-based pollutants, which are a major source of marine pollution. Despite the fact that these pollutants often originate from river basins that span multiple provinces, governance efforts tend to focus on enforcement by marine authorities at the estuaries, rather than adopting a more holistic approach. Furthermore, in coastal areas with high population and industry density, the relentless pursuit of large-scale industrial expansion has led to the proliferation of heavy and chemical industries near ports and coastlines, posing a significant threat to the ecological integrity of MPAs [75].

To address these challenges, a shift toward land–sea integration seems necessary and promising. Land–sea integration is a holistic approach that recognizes the land and sea as two interconnected systems. Effective planning under this framework should transcend the narrow confines of the coastal zone and encompass a wider range of resources [76]. By adopting this more comprehensive approach, land–sea integration can unlock new opportunities for sustainable economic development and environmental stewardship. The Ministry of Natural Resources is promoting a unified planning system for national territorial space, including marine functional zoning. In addition, to strike a balance between conservation and development, it is essential to adopt diverse protection strategies tailored to different types of MPAs. Areas of high ecological significance should be strictly protected, while others may combine conservation with sustainable resource use or focus on tourism development. By assessing ecosystem resources and environmental capacity based on natural growth, biodiversity, and conservation targets, a more flexible MPA system can be established.

6.2. Developing and Refining the Legal System for MPAs

A sound legal system is of utmost significance to the effective governance of MPAs. For example, the National Marine Sanctuaries Act of the United States provides a solid legal foundation for MPA-related work in the United States [77]. In 2000, Executive Order 13158 was issued [78], which further details the organizational structure of the management system of MPAs, the responsibilities of each participating party, the operational mechanism, and the evaluation criteria, laying the institutional foundation for establishing a comprehensive and coordinated national network of MPAs. The legal basis for the establishment of MPAs in the European Union includes the Natura 2000 network of protected areas established under the Birds Directive and the Habitats Directive, MPAs designated under regional marine conventions, and MPAs designated under national legislation [79].

By developing and refining legislation, China’s comprehensive natural protected area system in the marine sector can be developed, characterized by scientific classification, rational layout, effective protection, and efficient management, with national parks as the core. Targeted supporting and implementing regulations tailored to the distinct types, features, and functions of natural protected areas should be developed while prioritizing the development of technical standards. This will create a cohesive natural protected area legal framework consisting of basic law, specialized protection laws, and technical standards [80]. China should expedite the enactment of its National Park Law and revise relevant regulations governing nature reserves, marine special protected areas, and world geoparks. Furthermore, it is essential to closely integrate the development of MPA legislation with the construction of the national ecological compensation system. When formulating laws and regulations on ecological compensation, specialized research and surveys of MPAs should be carried out, and specific marine ecological compensation standards and guidelines should be established. Fines should be imposed on behaviors that damage the marine environment and resources, raising the cost of unlawful actions, reducing negative externalities, and ultimately safeguarding marine ecological resources [81].

6.3. Optimizing Structure of China’s Governance of MPAs

Optimizing MPA governance structures is vital for effective management and conservation, and the experiences of the United States and Australia can offer valuable insights for China. The United States has a total of 1031 MPAs, covering 12,205,915 km2 of ocean area [82]. The structure of MPA governance in the United States is characterized by diversity and collaboration, forming a national management system that involves the federal government, state governments, and the public. Within this framework, the National MPA Center, which is a partnership between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Department of the Interior that supports federal, state, territorial, and tribal programs responsible for the nation’s ocean health, plays a crucial role in coordinating various parties and strengthening the governance system. The National MPA Center gathers broad input from federal departments, state-level management agencies, regional fisheries management councils, the public, and the MPA Federal Advisory Committee, while maintaining two-way communication and cooperation with management entities at all levels. Federal departments provide assistance, management, and support for MPA governance; management agencies at state levels are directly responsible for the establishment and daily management of MPAs; the public and stakeholders promote the transparency and improvement of the management of MPAs by providing opinions, suggestions, and supervision; and the MPA Federal Advisory Committee provides independent and professional advice for management decisions while being subject to public supervision.

Australia’s MPA governance structure also serves as a valuable reference, especially through its emphasis on safeguarding marine habitats and species. Australia has 2597 MPAs, covering 8,994,340 km2 of ocean area [83]. Among them, the Royal National Park near Sydney was formally proclaimed in 1879, and in 1975, Australia enacted the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act, establishing the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park (GBRMP) to protect a large part of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef from damaging activities [84]. The GBRMP in Australia employs a management system in which government control is the primary approach. The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (GBRMPA) is largely responsible for managing the GBRMP and receives funding from both the federal government and Queensland’s state government. Since the park’s establishment, numerous plans have been enacted, most notably a 25-year conservation plan developed by the GBRMPA in 1994. Together, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act, along with relevant policies and plans, form the legal basis and guidelines for managing the GBRMP. The GBRMPA has established various committees, and its Board must include one member nominated by the Queensland Government, one member be Indigenous with knowledge of Indigenous issues in the Marine Park, and a member with tourism industry expertise. The GBRMP has been divided into several zones, and corresponding policies and legal guarantees have been put in place for each zone [85]. Public participation and economic impact assessments are also well-integrated into MPA planning in Australia, further enhancing the effectiveness of its governance framework [86].

China can glean valuable insights from countries such as Australia and the United States to enhance its MPA governance structure. Both demonstrate how unified management bodies, clear regulatory mechanisms, and active stakeholder engagement can help streamline MPA supervision, enforcement, and conservation efforts. Since the release of the “Guiding Opinions on Establishing a System of Natural Protected Areas with National Parks as the Mainstay”, the Ministry of Natural Resources has assumed responsibility for the unified management of MPAs nationwide, while local governments oversee MPAs within their respective administrative regions. In particular, the National Forestry and Grassland Administration is now in charge of unified supervision and management of national parks, nature reserves, scenic areas, marine special protected areas, natural heritage sites, and geological parks. This change represents a marked shift from the previous system, where various departments managed MPAs under their own distinct mandates. By centralizing oversight within the National Forestry and Grassland Administration of the Ministry of Natural Resources, MPA management can operate in a more coordinated and streamlined manner.

To support this new governance framework, China has introduced several regulatory and legislative measures. The 2022 “Regulations on Nature Reserves (Draft Revision)” stipulate that the State Council’s forestry and grassland administrative department shall oversee national nature reserves, including supervision and management responsibilities, while other relevant State Council departments assume related duties in accordance with their areas of responsibility [87]. Likewise, the draft National Park Law mandates the establishment of an interdepartmental coordination mechanism for national parks, led by the State Council’s forestry and grassland department and involving other departments such as development and reform, finance, natural resources, and ecological environment, to facilitate and advance national park development [88]. This exemplifies the new management framework for natural protected areas, wherein the forestry and grassland administrative department serves as the central authority, with other competent departments contributing in line with their respective mandates.

6.4. Enhancing the Effectiveness of MPAs in China

Certain gaps remain in need of further measures to ensure the effectiveness of China’s MPAs, and the EU’s experience can serve as a valuable reference in this endeavor. Within the EU’s Natura 2000 network, 3075 MPAs span approximately 451,538 km2 by 2022 [89]. Although Natura 2000 functions as a unified biodiversity conservation network, its large number, broad area, and extensive distribution make centralized management by the European Commission challenging. Consequently, the EU delegates the selection and management of areas to its member states, each of which proposes potential areas and submits them to the European Commission for review and approval [90]. In 2020, the European Commission adopted the 2030 Biodiversity Strategy as part of the European Green Deal, setting legally binding targets for the EU and its member states. These include establishing at least 30% of land and sea as protected areas, and restoring at least 30% of degraded ecosystems by 2030 [91].

Nevertheless, despite these ambitious goals, MPA management within the EU faces ongoing challenges. According to a 2019 assessment report by the World Wildlife Fund, while 12.4% of the EU’s marine waters are designated as MPAs, only 1.8% of these areas have a management plan in place. In practice, even less than 1.8% of the marine waters receive effective management and monitoring. As a result, it is currently impossible to determine which areas genuinely benefit from effective MPA management and successfully conserve biodiversity [92]. The European Parliament resolution of 16 January 2020 on the 15th meeting of the Conference of Parties to the CBD stresses that in the light of the recent IPCC report on the ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate, a comprehensive assessment and significant increase in EU coastal and marine protected areas and their governance is needed. The resolution recommends extending EU MPAs to include more offshore waters, while underscoring that besides the quantity, the quality of protected areas is essential to preventing biodiversity loss. Consequently, it calls for more emphasis on good and sustainable management [93]. Juliette Aminian-Biquet et al.’s research on EU MPAs in 2022 found that 86% of the 11.4% of EU waters covered by MPAs showed light, minimal, or no protection from the most harmful human activities, such as dredging, mining, or the most damaging fishing gears [94]. To address this challenge, the 2030 EU Biodiversity Strategy states that the EU will ensure better implementation of relevant environmental legislation affecting biodiversity, and review and revise it where necessary [95]. The European Commission will pay particular attention to areas with high biodiversity value or potential, and at least one-third of protected areas will be strictly protected [96].

In China, while MPAs are now under the unified management of the Forestry and Grassland Administration, the original administrative departments that previously managed these areas have established preliminary mechanisms that have shown some success. These departments, despite varying management measures, offer valuable lessons that can be built upon. As an example, in the area of ecological environment supervision and law enforcement in natural protected areas, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment promulgated the “Interim Measures for the Supervision and Management of Ecological and Environmental Protection in Natural Protected Areas” in 2020 [97]. These measures explicitly state that the ecological environment department retains responsibility for overseeing and managing the ecological environment of natural protected areas at all levels and categories. They also mandate that the Ministry of Ecology and Environment shall establish an ecological environment monitoring system for natural protected areas, formulate relevant standards and technical guidelines, construct a national ecological environment monitoring network system that integrates air, land, and space-based monitoring for natural protected areas, and conduct evaluations of the effectiveness of ecological environment protection in national-level natural protected areas. This suggests that the forestry and grassland administrative department, natural protected area management agencies, and ecological environment departments will need to maintain a collaborative approach to supervision and law enforcement in MPAs going forward.

To further enhance MPA governance, China should explore the establishment of a comprehensive maritime law enforcement mechanism, including setting up joint maritime law enforcement cooperation platforms and mechanisms. Coastal provinces and regions should collaborate to strengthen law enforcement and supervision in adjacent waters, establish a unified information-sharing mechanism, and streamline the case-transfer process. Such measures would effectively mitigate maritime environmental risks, while also constantly improving the emergency management framework for marine environmental incidents. Finally, China should implement scientifically grounded zoning and develop specific management regulations to guide community residents and businesses in lawful, orderly fishing, aquaculture, and eco-tourism practices, thus ensuring the community’s basic livelihoods, protecting enterprises’ legitimate interests, and promoting effective MPA governance.

7. Concluding Notes

Our research adopts the leverage points perspective of sustainability interventions to investigate the evolution of MPA governance in China, examining the number, effectiveness, legal framework, governance structure, value, and paradigm of MPAs, as well as highlighting the challenges facing their governance. Over time, China has established a network of MPAs focused on marine ecological protection, combining marine nature reserves and special protection areas. Case studies, including conservation efforts for marine species at the Dalian Spotted Seal National Nature Reserve, ecological status evaluations of ten national marine nature reserves by China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment, and the development of sea-related national parks, demonstrate the significant contributions of China’s MPA system to biodiversity conservation. Nevertheless, several challenges persist, and to establish a scientifically classified, rationally distributed, and effectively managed natural protected areas system with national parks at its core, China’s MPA governance requires further strengthening, including paradigm improvements, legal system refinement, governance structure optimization, and effectiveness enhancement.

Beyond the empirical scope of this study, we argue that achieving the Sustainable Development Goals and enabling sustainability transitions are fundamentally governance challenges. These challenges extend beyond sustainability envisioning—such as land use and landscape planning—to producing actionable knowledge that transforms envisioned sustainable futures into reality, such as land management. In this vein, a promising research avenue is to empirically investigate how real-world governance regimes manifest across the realms of leverage in domains like MPA governance and spatial governance at large. While theories provide elegant frameworks, practical success requires nuanced considerations tailored to specific contexts. Equally important, we contend that the conventional understanding of “land” as strictly terrestrial must be expanded to a more holistic and inclusive conceptualization that encompasses both terrestrial and marine environments. Recognizing this interconnectedness is crucial for advancing integrated spatial governance and sustainability efforts. In this regard, systematic and comparative studies across diverse national and regional contexts are particularly needed to inform integrated spatial governance of land and sea. By embracing this broader framing, land-related users, professionals, scholars, policymakers, and other stakeholders can better recognize that there is so much we can do to advance sustainability through land-related approaches. Let us, therefore, redefine “land” to include the vast, interconnected realms of terrestrial and marine environments and foster interdisciplinary, cross-sectoral, and transboundary collaborations to build a more sustainable future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W., Z.M. and Z.Z.; methodology, J.W. and Z.M.; formal analysis, J.W. and Z.Z.; investigation, J.W. and Z.M.; data curation, J.W., Z.M. and Z.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W., Z.M. and Z.Z.; writing—review and editing, J.W. and Z.Z.; visualization, Z.M.; supervision, J.W., Z.M. and Z.Z.; project administration, Z.M. and Z.Z.; funding acquisition, J.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a major project of the Key Research Base of Humanities and Social Sciences of the Ministry of Education, grant number 23JJD820014.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ocean Studies Board, National Research Council; Committee on the Evaluation, Design, and Monitoring of Marine Reserves and Protected Areas in the United States. Marine Protected Areas: Tools for Sustaining Ocean Ecosystems; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 146–147. [Google Scholar]

- Ad Hoc Technical Expert Group on Marine and Coastal Protected Areas. Marine and Coastal Biodiversity: Review, Further Elaboration and Refinement of the Programme of Work. In Proceedings of the Report of the 8th Meeting of the Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice, UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/8/9/Add.1, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–14 March 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eagles, P.F.J.; McCool, S.F.; Haynes, C.D.A. Sustainable Tourism in Protected Areas: Guidelines for Planning and Management; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK, 2002; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Dudley, N. Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2008; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, H. Where Does the Plastic in Our Oceans Come From? OurWorldInData.org. 2021. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/ocean-plastics (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Rees, S.E.; Foster, N.L.; Langmead, O.; Pittman, S.; Johnson, D.E. Defining the qualitative elements of Aichi Biodiversity Target 11 with regard to the marine and coastal environment in order to strengthen global efforts for marine biodiversity conservation outlined in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 14. Mar. Policy 2018, 93, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg Philanthropies. Just 2.8% of the World’s Ocean is Protected “Effectively”; Bloomberg Philanthropies Press: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Available online: https://www.bloomberg.org/press/just-2-8-of-the-worlds-ocean-is-protected-effectively/ (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Zheng, M. How to protect Marine biodiversity after. China Natural Resources News, 23 April 2020; p. A5. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, S.; Wang, H.; Shi, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, X. Research and prospects for China’s deep participation in global marine biodiversity conservation. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2024, 12, 1598–1612. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, B. The Protection and Management Strategies for Marine Biodiversity in China. Biodiv. Sci. 1999, 4, 347–350. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Dong, Z.; Zhou, B.-B.; Liu, Y. Smart Growth and Smart Shrinkage: A Comparative Review for Advancing Urban Sustainability. Land 2024, 13, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Wang, B.; Jones, P.J.; Axmacher, J.C. Challenges in developing China’s marine protected area system. Mar. Policy 2009, 33, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Liu, J.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Yu, W.; Chen, B. China’s marine protected area system: Evolution, challenges, and new prospects. Mar. Policy 2020, 115, 103780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Pikitch, E.K.; Xu, X.; Frankstone, T.; Bohorquez, J.; Fang, X.; Zheng, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Lin, W.; et al. An evaluation of management effectiveness of China’s marine protected areas and implications of the 2018 Reform. Mar. Policy 2022, 139, 105040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Chen, M.; Zeng, C.; Cheng, S.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Zou, C.; Ye, S.; Zhu, Z.; Cao, L. Assessing the management effectiveness of China’s marine protected areas: Challenges and recommendations. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 224, 106172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Cintio, A.; Niccolini, F.; Scipioni, S.; Bulleri, F. Avoiding “Paper Parks”: A Global Literature Review on Socioeconomic Factors Underpinning the Effectiveness of Marine Protected Areas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, P.J.S.; Long, S.D. Analysis and discussion of 28 recent marine protected area governance (MPAG) case studies: Challenges of decentralisation in the shadow of hierarchy. Mar. Policy 2021, 127, 104362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidler, R.Y.; Ahmadia, G.N.; Amkieltiela; Awaludinnoer; Cox, C.; Estradivari; Glew, L.; Handayani, C.; Mahajan, S.L.; Mascia, M.B.; et al. Participation, not penalties: Community involvement and equitable governance contribute to more effective multiuse protected areas. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl8929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giglio, V.J.; Moura, R.L.; Gibran, F.Z.; Rossi, L.C.; Banzato, B.M.; Corsso, J.T.; Pereira-Filho, G.H.; Motta, F.S. Do managers and stakeholders have congruent perceptions on marine protected area management effectiveness? Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 179, 104865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D. Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System; The Sustainability Institute: Hartland, WI, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Abson, D.J.; Fischer, J.; Leventon, J.; Newig, J.; Schomerus, T.; Vilsmaier, U.; Von Wehrden, H.; Abernethy, P.; Ives, C.D.; Jager, N.W.; et al. Leverage points for sustainability transformation. Ambio 2017, 46, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J.; Riechers, M. A leverage points perspective on sustainability. People Nat. 2019, 1, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riechers, M.; Fischer, J.; Manlosa, A.O.; Ortiz-Przychodzka, S.; Sala, J.E. Operationalising the leverage points perspective for empirical research. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 57, 101206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartkowski, B.; Bartke, S. Leverage Points for Governing Agricultural Soils: A Review of Empirical Studies of European Farmers’ Decision-Making. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Su, Y. A Research on the Legal System of Marine Protected Areas under Land-Sea Coordination. J. Ocean Univ. China (Soc. Sci.) 2021, 1, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, H.; Zhang, H.; Xiang, Y. Discussion on the Issues of Construction and Management of Marine Special Protection Areas. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2005, 3, 55–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, K.; Teng, F.; Zhong, S.; Ding, Y.; Tan, J. Research on the Problems and Countermeasures in the Development of National Marine Protected Areas in the Beihai Region. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2015, 11, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L.; Cheng, M.; Ying, P.; Qu, F.; Zhang, Z. Current Status, Issues, and Development Countermeasures of Marine Protected Areas in China. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2019, 5, 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- HY/T 117-2010; Classification and Grading Standards for Marine Special Protected Areas. People’s Republic of China Marine Industry Standard: Beijing, China, 2010.

- HY/T118-2010; State Oceanic Administration of China. Technical Guidelines for Functional Zoning and the Overall Plan Compiling of Special Marine Protection Area. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Li, Y.; Sun, M.; Ren, Y.; Chen, Y. The Implication of Systematic Conservation Planning on China’s Marine Protected Area Planning System. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2020, 2, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- The State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China. China’s Marine Ecological Environment Protection; The State Council Information Office: Beijing, China, 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/202407/content_6962503.htm (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China. The Overall Plan for Ecological Civilization System Reform. China Government Network. 21 September 2015. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/guowuyuan/2015-09/21/content_2936327.htm (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- China Awarded the Hosting Rights for the 15th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-12/10/content_5146242.htm (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- China Marine Conservation Industry Report: China Has Established 271 Marine Protected Areas. Available online: http://env.people.com.cn/n1/2020/1014/c1010-31892097.html (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Li, Y.; Ma, J.; Costigan, A.; Yang, X.; Pikitch, E.; Chen, Y. Reconciling China’s domestic marine conservation agenda with the global 30×30 initiative. Mar. Policy 2023, 156, 105790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grorud-Colvert, K.; Sullivan-Stack, J.; Roberts, C.; Constant, V.; Horta e Costa, B.; Pike, E.P.; Kingston, N.; Laffoley, D.; Sala, E.; Claudet, J.; et al. The MPA Guide: A framework to achieve global goals for the ocean. Science 2021, 373, eabf0861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, X.; Liang, J.; Zeng, J.; Chen, M.; Zeng, C.; Mazur, M.; Li, S.; Zhou, Z.; Ding, W.; Ding, P.; et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of three national marine protected areas in the Yangtze River Delta, China. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 911880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lv, C.; Hu, D.; Li, Q.; Wang, X. Effectiveness Analysis and Countermeasure Suggestions of Planning Environmental Assessment in Marine Nature Reserves: A Case Study of the Dalian Spot-Seal National Nature Reserve. In Proceedings of the Chinese Society for Environmental Sciences, 2019 Annual Conference of the Chinese Society for Environmental Sciences, Xi’an, China, 23–25 August 2019; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- National Forestry and Grassland Administration. Internationally Important Wetlands|Liaoning Dalian Spotted Seal Internationally Important Wetland: Guardian of the “Spirits” of the Liaodong Bay. Available online: https://www.forestry.gov.cn/main/6228/20220926/164135923958390.html (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Dong, J.; Shen, F. Estimation of Historical Population Size of Harbour Seal (Phoca Largha) in the Liaodong Bay. Mar. Sci. 1991, 3, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhuanet. This Adorable ’Chubby Baby’ Must Be Protected! Available online: https://app.xinhuanet.com/news/article.html?articleId=70736b3fce6ee2107cd1c9b7ec898048 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Action Plan for the Protection of the Spotted Seal (2017–2026). Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/nybgb/2017/djq/201802/P020180202505868637696.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- 2023 Bulletin of Marine Ecology and Environment Status of China. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/hjzl/sthjzk/jagb/202405/P020240522601361012621.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Bernik, B.M.; Li, H.; Blum, M.J. Genetic variation of Spartina alterniflora intentionally introduced to China. Biol. Invasions 2016, 18, 1485–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.; Hu, Y.; Li, B.; Song, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, T.; Li, X. Effects of Spartina alterniflora eradication project on macrobenthos community structure: A case study of Nanhui tidal flat in Shanghai. Chin. J. Ecol. 2024, 43, 2892–2900. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, A.; Yang, J.; Liu, B.; Zou, Y. Prediction on the Changes in Potential Suitable Areas for Mangroves Along the Coast of Guangxi and the Threat from Spartina Alterniflora Invasion. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2024, 3, 669–677. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, M.; Cai, H.; Qian, W. Challenges and Countermeasures of Marine Protected Areas in China under the New Nature Reserve System. J. Anhui Agric. Sci. 2023, 20, 78–81. [Google Scholar]

- CPC Central Committee. The Communique of the Third Plenary Session of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. Available online: http://www.ce.cn/xwzx/gnsz/szyw/201311/18/t20131118_1767104.shtml (accessed on 31 October 2024).

- Liu, H.; Liu, Z. Current Status, Issues, and Countermeasures of Marine Protected Areas in China. J. Mar. Inform. Technol. Appl. 2015, 1, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- National Park and Other Nature Reserves Construction and Wildlife Protection Major Engineering Planning (2021–2035). Available online: https://www.bypc.gov.cn/upfiles/file/20220317/1647507018897358.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- Achieving a Comprehensive Well-off Society and Securing Great Victories in the New Era of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics. Available online: http://www.xinhuanet.com/politics/19cpcnc/2017-10/27/c_1121867529.htm (accessed on 15 August 2024).

- The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. The State Council Institutional Reform Plan. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/guowuyuan/2018-03/17/content_5275116.htm (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Nathan, J.B.; Philip, D. Why local people do not support conservation: Community perceptions of marine protected area livelihood impacts, governance and management in Thailand. Mar. Policy 2014, 44, 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Changdao National Marine Park Management Center. 2024 Annual Work Summary. Available online: https://www.changdao.gov.cn/art/2024/12/10/art_30545_2950311.html?xxgkhide=1 (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Qin, T. The Process and Challenges of China’s Implementation of the Convention on Biological Diversity. J. Wuhan Univ. (Philosoph. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 74, 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, D.; Zhang, Y. Biodiversity Conservation Achievements and Prospects in China. Environ. Prot. 2019, 47, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y.; Yang, X. On the Ecological Holism Implications of Environmental Law and Its Implementation Pathways. J. Shandong Univ. Technol. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 1, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Encyclopedia of China Editorial Board, Environmental Science Committee. Encyclopedia of China, Environmental Science; Encyclopedia of China Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/VII/28, para.8. Available online: https://undocs.org/Home/Mobile?FinalSymbol=UNEP%2FCBD%2FCOP%2FDEC%2FVII%2F28&Language=E&DeviceType=Desktop&LangRequested=False (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/VII/5, Operational Objective 1.1. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-07/cop-07-dec-05-en.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- COP 5 Decision V/6. Available online: https://www.cbd.int/decisions/cop/5/6 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Report of the Secretary General. UN General Assembly Doc. A/61/63. Available online: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/gen/n06/473/29/pdf/n0647329.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Pilot Scheme for the System of Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park. Available online: https://www.hainan.gov.cn/hainan/zchbbwwj/202008/f0a42020ac1547098d502acd161119cf.shtml (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park Overview. Available online: https://www.hntrnp.com/news/list-276.html (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- The Second National Parks Forum Focuses on Biodiversity Conservation. Available online: https://www.forestry.gov.cn/c/www/lcdt/518703.jhtml (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- The Yellow River Estuary Selected as a Key Area for ’National Park’ Creation: Overall Planning Map Released. Available online: https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20211021A0ARPW00 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Liaoning Province Actively Establishes Liaohe Estuary National Park. Available online: https://www.ln.gov.cn/web/ywdt/ggaq/hjbh/406F98361C56454B891548E918E8BF66/index.shtml (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Changdao Included in National Park Spatial Planning Scheme. Available online: https://www.changdao.gov.cn/art/2022/11/11/art_64836_2935441.html (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Peng, X.; Jin, Y. Planning Compilation Techniques and Integrated Optimization Methods of Natural Protected Area System, National Park and Scenic Spot: Based on Landscaping Governance under Policy Guidelines. Urban Rural Plan. 2023, 6, 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- Several Opinions on Delimiting and Strictly Observing the Ecological Protection Red Line. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2017-02/07/content_5166291.htm?trs=1 (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Shi, X.; Shen, W.; Ma, W.; Jiang, J. Suggestions for Biodiversity Conservation Based on Ecological Environment Zoning Management. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 6, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mei, H.; Xu, X. Research on the Institutional Evolution of China’s Marine Special Protection Zones. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2023, 12, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Xie, Y.; Li, Y.; Cong, L. How to delineate and zone protected areas under the scope of ecological conservation redline strategy. Biodiv. Sci. 2022, 4, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Gao, G. The Connotation of and Policy Recommendation for Overall Planning Development of Land and Sea in China. China Soft Sci. 2015, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Di, Q.; Zhou, L. Discussion on the Connotation and Target of Sea-Land Coordination. Mar. Econ. 2012, 1, 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- National Marine Protected Areas Center. National system of Marine Protected Areas. Available online: https://marineprotectedareas.noaa.gov/ (accessed on 1 October 2024).