Abstract

A significant segment of the inhabitants in Mexico have a high rate of malnutrition and obesity, especially in impoverished and segregated areas. This study analyzes the paradox of food swamps, food availability, and food’s ecological footprint to promote the creation of community gardens in Querétaro. This paper is segmented into four sections. It starts by recording the omnipresence of the Mexican chain “OXXO” convenience stores, which offer mainly processed foods. The second segment of the research depicts the miles traveled by Mexican crops to visualize their carbon footprint. The third portion explores the impact of urban agriculture in the 20th century on cities. The final section proposes designing and implementing community gardens in two marginalized neighborhoods (Tlacote and San Antonio–Bolaños) in Querétaro, Mexico, to foster healthier, more sustainable neighborhoods. The findings corroborate a soaring number of unhealthy food stores, elevated carbon footprints related to food production, and a community request for urban agriculture, including the regeneration of community public areas. The research emphasizes the impact of landscape urbanism, especially community gardens, to foster social, urban, and environmental regeneration. The study provides a scheme for advocating healthier lifestyles and more sustainable urban environments by focusing on food distribution, ecological services, and community engagement.

1. Introduction

The global food paradox, characterized by the overproduction of food alongside high rates of malnutrition and environmental problems, is a pressing concern. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) report, around 600 million people will be chronically undernourished by 2030. In 2022, an estimated 2.4 billion people were moderately or severely food insecure, lacking access to adequate nutrition [1]. The coexistence of food insecurity and obesity is expected given that both are consequences of economic and social disadvantage [2]. Access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food not only affects the health of people who experience food insecurity but also their ability to manage health conditions, such as diabetes [3]. Diabetes is rapidly emerging as a global healthcare problem that threatens to reach pandemic levels by 2030; the number of people with diabetes worldwide is projected to increase from 171 million in 2000 to 366 million by 2030 [4]. This increase will be most noticeable in developing countries, where the number of people with diabetes is expected to increase from 84 million to 228 million [5]. The serious cardiovascular complications of obesity and diabetes could overwhelm developing countries, which are already straining under the burden of communicable diseases [6]. This condition in Mexico is becoming increasingly critical. With 75% of the population affected, Mexico has one of the highest rates of obesity in the world. This high prevalence is associated with a shift in diet toward foods and beverages that are high in calories and processed [7].

The prevalence of obesity in the poorest regions of Mexico mirrors that of wealthier areas, despite a significant increase in non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and ongoing problems with malnutrition and poor sanitation [8]. Additionally, the proliferation of convenience stores, such as OXXO, is exacerbating this problem by offering food that is predominantly low in nutritional value, contributing to an obesogenic environment in which excessive food intake is encouraged [9]. Obesogenic environments, characterized by low-quality food availability, contribute to health risks, such as diabetes and heart disease. Urban agriculture provides a potential solution by supplying fresh, nutritious fruits, vegetables, and herbs closer to the urban environment, alleviating dependency on processed and unhealthy foods. There is also evidence that areas with increased access to fast food outlets and convenience stores offering processed food with high sugar and fat content have a higher prevalence of obesity [10].

Although the impact of the food environment on obesity is well-documented, the specific role of convenience stores, with their focus on processed foods, in perpetuating unhealthy diets and the increasing public health challenges in Mexico requires further investigation. Facing Mexico’s obesity and food security crises entails a wide-ranging methodology that evaluates food environments and examines alternative resolutions like urban agriculture. Recognizing the multidimensional connection between food accessibility, nutritional value, and environmental benefit is crucial to fostering efficient approaches to easing these challenges.

While Queretaro’s GDP per capita is higher than that of similar regions, almost half of the inhabitants still need to be more capable of affording a basic food basket. This economic disparity is associated with high rates of obesity and malnutrition in impoverished neighborhoods. Additionally, the concept of “food miles” and its implications for environmental sustainability and food security in urban areas like Querétaro has not received much research attention.

The primary purpose of this research is to study the role of urban agriculture, particularly community gardens, focusing on the interrelated concerns of food security and obesity in Querétaro, Mexico. Community gardens offer a beneficial alternative for mending food security and lowering environmental effects in cities. By incorporating economic, social, and spatial analysis, this study attempts to recognize neighborhoods where community gardens could be introduced to increase food security and diminish the environmental impact of food miles.

This research aims to encourage local food production, improve nutritional value, and promote sustainable urban environments to highlight community gardens’ benefits, such as food security, social interaction, and environmental protection. Furthermore, it seeks to create healthier, more resilient communities by providing possible replicable solutions for neighborhoods with similar concerns.

2. Literature Review

Although the impact of the food environment on obesity is already documented by different authors, Morland (USA), Popkin (Latin America), and Pineda (México), there is limited research focused on how food miles and food environments could be transformed by urban agriculture, reducing their food miles and promoting sustainability in the long term. Therefore, as part of this research, we look at four main concepts: urban food landscapes, urban miles, urban agriculture, and community gardens.

2.1. Urban Food Landscapes and Food Miles

The Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture at Iowa State University researched the average distance food travels from crop fields to the dinner table, revealing that it generally spans over 2000 miles [11]. Although these figures may vary by city or country, the impact of food miles on the environment is profound. The Friends of the Earth Organization also authored a study on the movement of food and its environmental harm titled “How many kilometers does food travel before it reaches your plate?” [12]. This research gained notice within academic, economic, and political circles, sparking widespread attention on “food miles”. The study introduced the idea of “food miles”, which was first created to measure the distance between the producer and the food consumer. “To reduce food miles implies the need for food systems grounded in local ecologies and responsive to consumer demands for quality food” [13].

Food environments are composed of opportunities, environments, and physical, economic, political, and socio-cultural conditions that determine the interaction of people and the food system [11] and influence food behavior (consumption and acquisition) [12]. In an urban context, food environments are recognized according to their food accessibility and are divided into three categories: (1) food deserts, (2) food swamps, and (3) food oases. Food deserts are deprived areas with limited access to nutritious and affordable food. In contrast, food oases are privileged by their access to healthy food. Finally, food swamps are where food is available but is characterized by high-calorie content dominating healthy food environments [14].

Moreover, an obesogenic environment, characterized by low-quality food availability, contributes to health risks, such as diabetes and heart disease. There is also evidence that areas with increased access to fast food outlets and convenience stores offering processed food with high sugar and fat content have a higher prevalence of obesity [10]. Finally, the characterization of urban food landscapes becomes relevant for understanding the relationship between food systems and communities.

2.2. Urban Agriculture

Urban agriculture is an alternative to poor nutrition and food shortages in urban environments, providing a potential solution by supplying fresh, nutritious fruits, vegetables, and herbs closer to the urban environment, alleviating dependency on processed and unhealthy foods. “Urban gardens seek to increase nutritional food security for vulnerable populations, producing food for self-consumption in small spaces” [15].

The benefits of urban agriculture are multidimensional, addressing economic, environmental, and social advantages. They can provide an additional source of income, especially in vulnerable neighborhoods, promote sustainable practices, and foster community engagement. Historically, there has been a close relationship between architecture, urban planning, and landscape design, as demonstrated by the cultivation of medicinal and edible plants in public parks. Likewise, during World War II, European cities such as London established Victory Gardens due to food shortages.

Numerous architects throughout history have proposed concepts for integrating agriculture [16]. In his 1898 book Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, Ebenezer Howard [17] envisioned a “Garden City” that included agricultural land as part of the urban setting. This proposal featured a city designed for 32,000 residents, with 2400 hectares dedicated to agriculture and 404 hectares allocated for housing and recreation. Similarly, in his book The City of the Future [18], Le Corbusier advocated for each modern resident to have a 400 square meter garden, with 150 square meters reserved for self-sufficiency cultivation. Frank Lloyd Wright also proposed the project Broadacre City, where each family would use a hectare of land for food production, integrating agricultural activities directly into the built environment [19].

In recent years, urban gardens have proliferated across Latin America, the United States, and Europe, driven by social, economic, and environmental factors. Financial and political crises have further accelerated the incorporation of agriculture into urban settings. “Urban agriculture (UA) is spreading across vacant and marginal land worldwide, embraced by government and civil society as a source of food, ecosystems services, and jobs, particularly in times of economic crisis” [20]. For instance, in Cuba, Havana has become a model for urban food production in response to the economic blockade it has experienced [20].

Environmental awareness also drives the development of community gardens. Urban agriculture can enhance ecological quality through efficient water recycling, which contributes to greening cities, repairing urban remnants, reactivating public spaces, and integrating agriculture into local collective activities. [21]. Community gardens promote social cohesion, create employment opportunities, and generate family income. Studies have found that community gardens can directly improve food access to a certain degree and indirectly increase access to healthy foods in terms of food security [22].

Implementing community gardens requires a clear definition of a financial, legal, and management strategy considering the short-, medium-, and long-term maintenance mechanisms that promote community sustainability and resilience. While we recognize the importance of this strategy, this article does not focus on developing such a strategy but rather on detecting a series of opportunities in vulnerable neighborhoods in the city of Querétaro. Additionally, community gardens provide places where people can grow their food, alleviating economic barriers to fresh produce [22]. When food production occurs within urban settings, the proximity of storage, transportation, and consumption to consumers enhances the affordability, availability, and nutritional value of these foods for families.

3. Materials and Methods

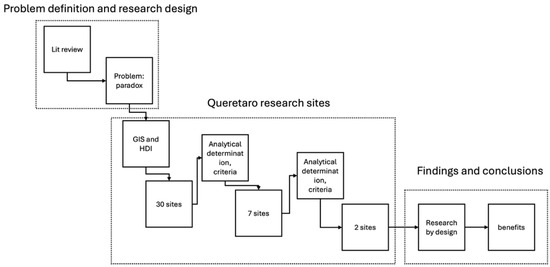

The methodology used in this study is founded on three phases: problem definition and research design, site research, and findings and conclusions, as explained in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The methodology used in this study is founded on three phases: problem definition and research design, site research, and findings and conclusions.

Once the challenges had been defined and based on the literature review (Step 01), a methodological procedure for a systemic analysis was outlined. This facilitated the analysis and site selection with the most significant potential for executing community gardens. Official data from the Municipal Planning Institute (IMPLAN), INEGI, and Geographic Information Systems was utilized to identify vulnerable neighborhoods and transform deteriorated areas into vibrant green spaces.

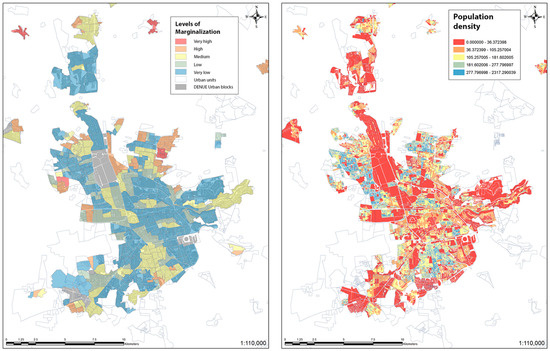

The initial step is to generate a socio-demographic outline of the geostatistical areas of Querétaro, as specified below in 2.2. (Figure 2). This analysis recognized 30 possible neighborhoods with a certain level of vulnerability, including lack of infrastructure and public services, urban connectivity, green space accessibility, and public areas.

Figure 2.

GIS maps of Queretaro that consider levels of marginalization and population density.

Figure 2 shows the socio-demographic outline of the geostatistical areas of Querétaro. The first map (on the right) shows the margination levels. In red, there are very highly vulnerable areas. In orange, there is a high level; and in yellow, there is a medium level of marginalization. Furthermore, these areas represent the areas that could have the most significant opportunities to impact vulnerable areas. On the other hand, the second map (on the left) shows green and blue as the most dense areas and, therefore, the most significant opportunities due to density conditions. This analysis recognized 30 possible neighborhoods with a certain level of vulnerability, including lack of infrastructure and public services, urban connectivity, green space accessibility, and public areas.

Seven of the 30 selected sites demonstrated positive urban connectivity, density, and existing green areas. The rest had legal challenges related to land tenure and informal settlements. Tlacote and San Antonio–Bolaños were chosen because of their urban accessibility, existing green spaces, potential for community involvement, and minimal legal constraints. Their reasonable population density supports the revitalization efforts, while their lack of key infrastructure emphasizes the need for a design proposal. Therefore, only two sites were designated to revitalize the deteriorated recreational infrastructure, upgrade the existing public spaces, and increase food accessibility.

3.1. Selecting Sites for Urban Gardens

Even though the margination degree is low in comparison with other municipalities within the state of Querétaro [5], 20,789 of the total residents in the Municipality of Queretaro are living in poverty [23]. The Municipal Planning Institute identified that 10.3% of the urban area corresponds to irregular settlements [24]. Socioeconomic vulnerability increases the population’s predisposition to obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease. Nonetheless, a further GIS analysis was conducted to identify the neighborhoods with the most potential for urban gardens.

3.2. GIS Analysis for Selecting Sites

First, we analyzed the Geostatistical Areas (AGEBs) of Querétaro to conclude where the community gardens could be projected. The key analyzed elements for each area were:

- ∗

- the total population of the town;

- ∗

- the number of homes;

- ∗

- the number of economically active people in the locality;

- ∗

- the number of people without schooling;

- ∗

- the number of inhabitants without drainage in the town;

- ∗

- the number of inhabitants without electricity;

- ∗

- number of inhabitants with washing machines or refrigerators;

- ∗

- inhabitants without radio or television;

- ∗

- quantity of housing with a dirt floor.

These data were the basis for examining vulnerable areas to propose urban community gardens. Thanks to GIS mapping, 30 sites were initially identified. Seven neighborhoods were further studied based on deficient infrastructure, availability of green regions, urban connectivity, and public space. It was vital to broaden the analysis of neighborhoods to avoid being overly dense yet have an adequate number of inhabitants to ensure the project’s feasibility and community participation. Finally, the two sites that met the described criteria were irrevocably selected: Tlacote and San Antonio–Bolaños.

3.3. Description of Sites

First, GIS and HDI analyses recognized 30 probable sites for urban agriculture. Additionally, the legal circumstances of 23 sites prevented their selection for community gardens. Most of the 23 areas identified confirmed proof of informal settlements without land tenure and legal viability, leaving them out of the selection process. Therefore, only seven sites were further researched, considering their urban density, potential stakeholder interest, and convenient urban connectivity. These seven neighborhoods were examined because of the possible reuse of their existing green areas and public spaces, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

The table briefly describes the characteristics of several neighborhoods considered for a possible community garden proposal. Only two were finally selected.

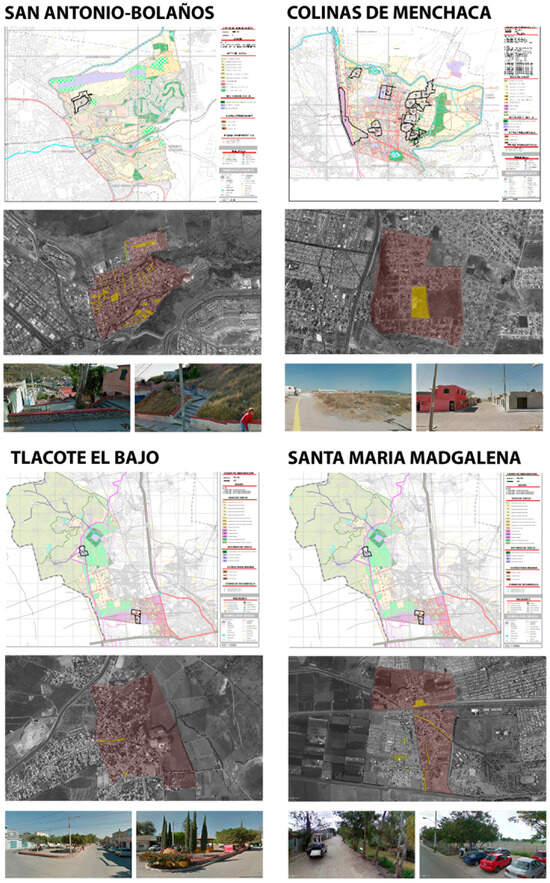

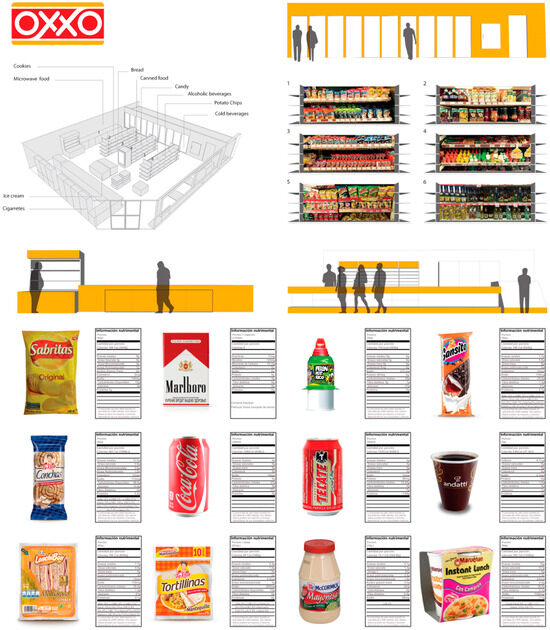

A more comprehensive analysis of the two final sites was completed. Tlacote and San Antonio Bolaños were chosen to regenerate their existing and deteriorated recreational and sports facilities to improve public space and food availability. Considering the surveys answered by local inhabitants, the neighbors were interested in transforming their public spaces into a community-based food production project. Kevin Lynch’s methodology helped us understand the spatial, economic, and social dynamics of Tlacote and San Antonio Bolaños. This concluded with a conceptual project for community gardens at both sites. Figure 3 demonstrates the GIS, census tracts, and site visit photos used to appraise and select the most relevant neighborhoods for community gardens.

Figure 3.

Different neighborhoods and site selections are analyzed using census tracks, geographic information systems, and site visits.

3.4. Selection of 2 Final Sites

After evaluating 30 potential sites for community gardens, two locations were selected: San Antonio–Bolaños and the community of Tlacote. These two locations were selected based on a detailed site analysis, surveys, community participation, and urban connectivity previously described to ensure the community garden would be placed in adequate locations. Both sites consisted of existing public spaces with deteriorated recreational and sports infrastructure. Similarly, surveys were conducted to gather the local population’s perspective on the public space, food availability, and willingness to transform their spaces into a community-based food production project. Additionally, a site analysis was developed based on Kevin Lynch’s urban experience methodology (Table 2) in order to identify the key elements of the city’s image and aim to create user-friendly environments.

Table 2.

briefly describes the site analysis and Kevin Lynch’s urban experience methodology to identify five key elements that shape the city’s image (paths, edges, districts, nodes, and landmarks) and propose user-friendly environments.

In the end, the goal was to promote a healthier food environment by providing locally nutritious food, reducing carbon emissions, revitalizing public spaces, and fostering social cohesion among the residents by proposing community gardens in these neighborhoods. In this sense, San Antonio–Bolaños and Tlacote were selected for their public spaces, community engagement, and urban connectivity. Surveys showed local interest in community gardens to improve food access and regenerate public spaces. Tlacote’s agricultural heritage and strong community ties made it ideal, while San Antonio–Bolaños offered infrastructure potential despite marginalization, ensuring the project’s feasibility and impact.

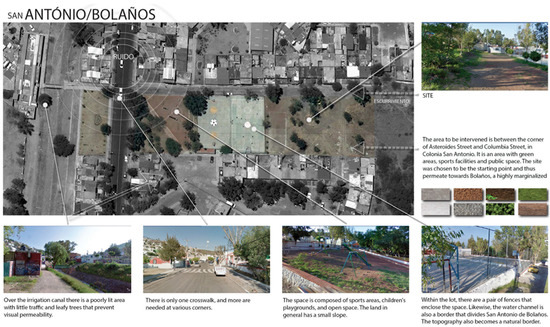

3.5. San Antonio–Bolaños Community Garden

The intervention area is between Asteroides and Columbia Streets, in Colonia San Antonio, beside Bolaños. It is an area with green, sports, and public spaces. The site was chosen as a point of departure and, therefore, to generate accessibility to Bolaños, a highly marginalized area (Figure 4). San Antonio–Bolaños, though suitable for an urban garden, lacks public life, safety, and vibrancy. Placemaking strategies, like community gardens, could revitalize the area, fostering social cohesion, environmental benefits, and urban quality. “Access to natural areas and green space, such as parks and gardens, has been shown to offer a myriad of health promotion outcomes that include restorative effects, such as improved mental health and enhanced wellbeing” [26].

Figure 4.

San Antonio–Bolaños Site overview.

Above the irrigation canal is a poorly lit area with little traffic and leafy trees that prevent visibility. There is limited pedestrian accessibility. There is only one pedestrian crossing, and more is needed at the corners. The area comprises sports fields, a children’s playground, and open public spaces. The terrain is generally gently sloping.

Furthermore, two fences enclose the space within the land. The fences protect the sports facility but also restrict accessibility. The redesign aims to improve access, visibility, site integration, and food security. Likewise, the water channel forms a boundary that divides San Antonio de Bolaños. The topography also becomes a natural border.

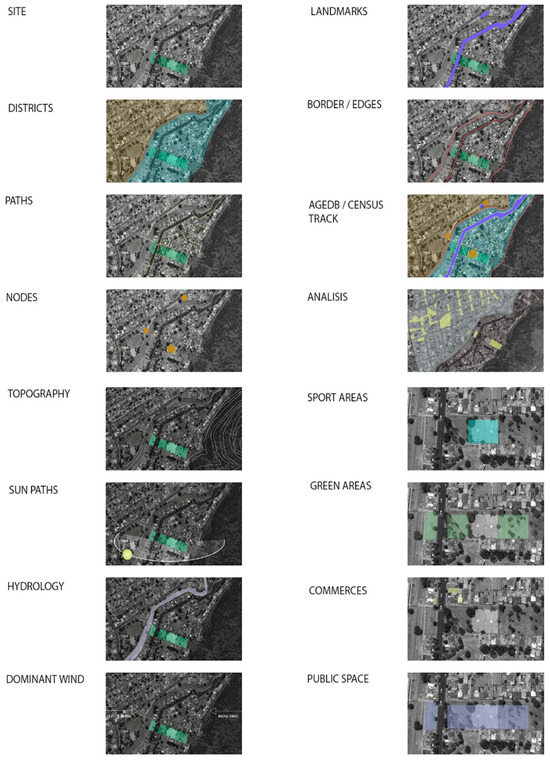

This proposal uses Kevin Lynch’s approach to city imageability as a framework for understanding and improving people’s perception and navigation in urban environments. Lynch’s five elements of city imageability (paths, nodes, edges, districts, and landmarks) provide the underlying structure for organizing visual representations of the community [27] (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Site Analysis of San Antonio–Bolaños, including districts, paths, nods, topography, sundial, hydrology, dominant winds, landmarks, edges, sports areas, green areas, commerce, and public space.

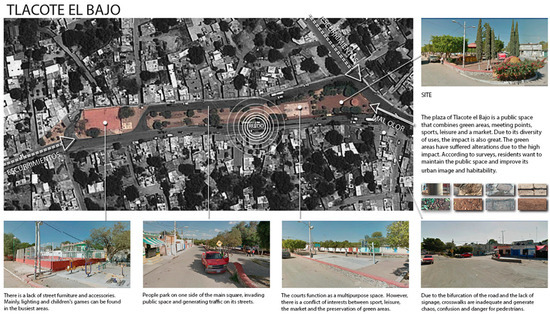

3.6. Tlacote El Bajo Community Garden

The public plaza in Tlacote El Bajo combines green areas, gathering spaces, sports and leisure facilities, and an itinerary market. According to surveys, the local inhabitants desire to maintain the public plaza and improve their urban image and quality of life (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Tlacote site overview.

In this public plaza, urban furniture is scarce. Lighting and children’s games are mainly found in the busiest areas. People park their cars in the main square, invading the public space and generating street traffic. The sports fields help the square to host multipurpose activities. However, there is a conflict of interest between sports, leisure, the flea market, and the preservation of green spaces. Crosswalks must be better designed, and signposts are scarce, causing confusion and danger to pedestrians.

The site selected for the community gardens in Tlacote is in the central plaza. Once again, Kevin Lynch’s approach uses city imageability as a framework, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Tlacote site analysis, including districts, paths, nodes, topography, sundial, hydrology, dominant winds, landmarks, edges, sports areas, green areas, commerce, and public space.

3.7. Community Gardens for Healthier, Sustainable Neighborhoods

Urban gardens in Tlacote and San Antonio–Bolaños seek to enhance community health by expanding access to fresh food, reactivating public spaces, and encouraging better lifestyles. This landscape project promotes sustainable urban living and environmental responsibility.

The urban and community gardens proposal in Tlacote and San Antonio–Bolaños will help improve access to nutritious and locally grown food. This project aims to reduce dependency on processed foods while benefiting community health by making fresh vegetables more accessible. “Community gardens have been identified as a model for promoting sustainable urban living. They can also contribute to individual and community reconnection to the socio-cultural importance of food, thus helping facilitate broader engagement with the food system. Such processes may offer pathways to developing a deep engagement and long-term commitment to sustainable living practices predicated on developing new forms of environmental or ecological citizenship” [28].

The proposal for urban agriculture in Tlacote and San Antonio–Bolaños transforms deteriorated parks into vibrant public areas. These urban gardens also strengthen community ties by allowing local areas to coexist, collaborate, and socialize. “As convivial spaces, urban gardens build and nurture agency of individuals as well as social ties in a community. As inclusive cultural spaces, urban gardens can function as a place for cross-cultural learning and understanding and building connections across social and cultural divides. As a vital space, urban gardens contribute to individual and community health and well-being. As democratic spaces, urban gardens engage individuals and communities in efforts toward other social and environmental initiatives” [29].

Another strategy is to promote healthier lifestyles by introducing locally produced food and active participation through gardening to fight chronic health conditions, including diabetes, hypertension, and obesity. “Improving access to quality food is important because it contributes to a healthy diet, which, in addition to increased physical activity, aids in the prevention of obesogenic environments” [30]

4. Results

4.1. The Dual Crisis of Obesity and Food Insecurity in Mexico

The global food paradox demonstrates excessive food production, high malnutrition rates, and environmental challenges. However, 600 million people will be chronically underfed in 2030, and “in 2022, an estimated 29.6 percent of the global population—2.4 billion people—were moderately or severely food insecure, meaning they did not have access to adequate food” [1].

In Mexico, this paradox is apparent with high levels of malnourishment and obesity, particularly in the most deprived neighborhoods. Mexico’s inequality is evident. Although the GDP per capita is now above the regional average, 48·8% of the population is poor and cannot afford the basic food basket [3]. Mexico has one of the highest rates of obesity and overweight worldwide, affecting 75% of the population. The country has experienced a dietary and food retail transition involving an increased availability of high-calorie-dense foods and beverages [2]. The rise of convenience stores offering processed foods is displacing Mexican diets based on fresh vegetables, fueling obesity and chronic disease. The combination of aggressive marketing and accessibility creates food swamps and obesogenic environments that reinforce unhealthy eating habits. The Latin America and Caribbean (LAC) region faces a major diet-related health problem that is accompanied by enormous economic and social costs. The shifts in diet are profound, including major shifts in intake of less-healthful low-nutrient-density foods and sugary beverages, changes in away-from-home eating and snacking, and rapid shifts towards very high levels of overweight and obesity among all ages along with, in some countries, high burdens of stunting. [31]

Furthermore, the obesity prevalence in adults in the poorest regions of Mexico is like that of high-income areas. These regions have had the highest relative increase in mortality due to non-communicable diseases (NCDs) during past decades and continue to struggle with undernutrition and poor sanitation [2].

4.2. Convenience Stores and Obesity

Over time, food systems and diets change. “As large companies increasingly dominate markets, highly processed foods become more readily available, and traditional foods and eating habits are displaced” [1]. Processed foods have become part of people’s daily diets, increasing chronic and degenerative diseases due to high levels of sugar and fat. As Francesco Branca, Director of the World Health Organization’s Department of Nutrition for Health and Development, described: “We have solid evidence that keeping intake of free sugars to less than 10% of total energy intake reduces the risk of overweight, obesity and tooth decay” [28].

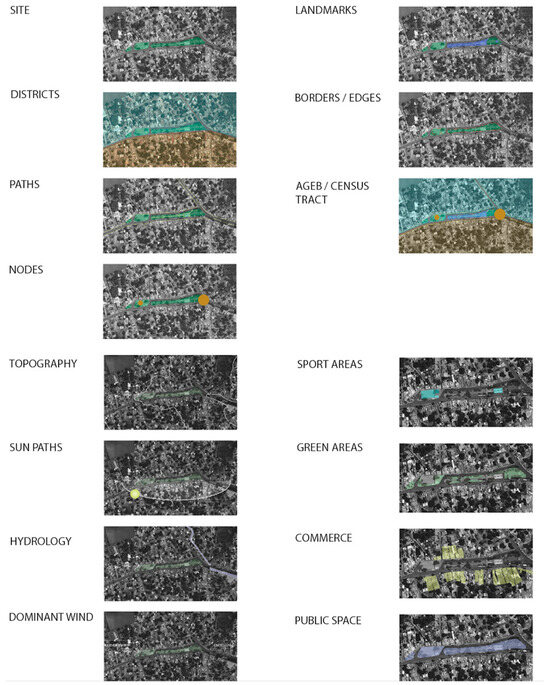

With over 12,000 OXXO convenience stores, Grupo FEMSA has a monumental presence selling mainly processed foods in Mexico. Each OXXO has more than 3000 items, many of them processed foods (Figure 8), and according to El Economista, 20% of their sales are from soft drinks, 20% from tobacco, and 10% from food [4]. Because of the significant presence of convenience stores having products with few nutrients, many areas of Mexico have become food swamps and obesogenic environments. The current epidemic of obesity is mainly caused by an environment that promotes excessive food intake and discourages physical activity [32].

Figure 8.

This image demonstrates the spatial distribution of fast-food chain OXXO convenience stores and the best-selling products along with their Nutrition Facts labels. In this sense, Figure 8 shows a sampling of the most available products, where foods with higher caloric and sugar content predominate. This could suggest that the most consumed foods are physically accessible in stores.

4.3. Food Mapping and Urban Garden Proposal in Queretaro

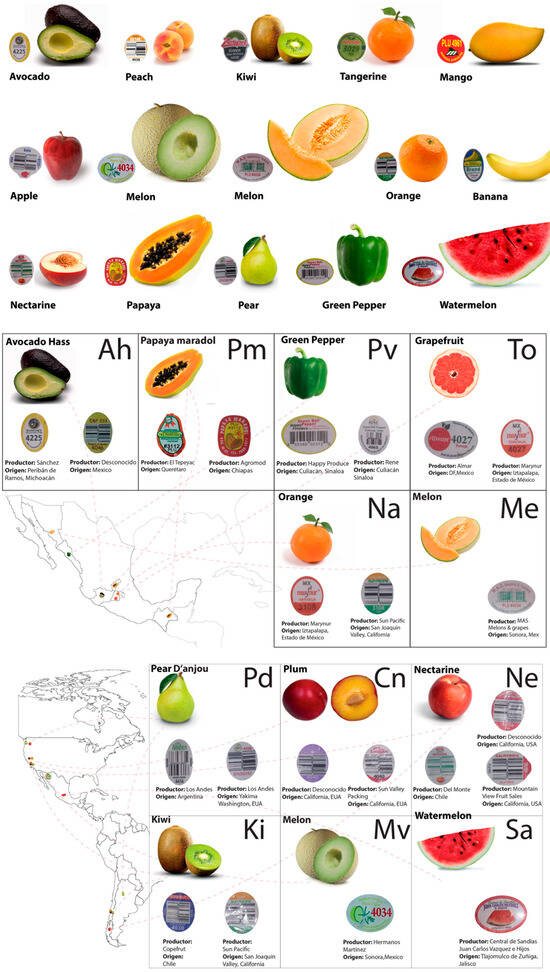

Considering the approaches on food miles by the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture [16], this study helped us map the geographical origins of fruits and vegetables that are available in supermarkets in Queretaro, Mexico. Our findings reveal that these nutritious and natural foods often travel substantial distances before reaching the consumer, highlighting that they are not absolved of complexities, such as environmental pressure and carbon footprint, despite their advantage over processed food (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Mapping of food origins in Mexico and the Americas.

Figure 9 shows the food origin of the most common fruits and vegetables identified in the local stores. This mapping process shows that most of these products are produced abroad, evidence of the increasing distance between producers and consumers.

In response to the challenges faced by specific neighborhoods in Queretaro, characterized by limited access to affordable and nutritious food, low-income levels, and inadequate health services, this study utilized Geographical Information Systems and Human Development Index criteria to identify areas where the establishment of community gardens could serve a landscape urbanism strategy. The analysis emphasizes the opportunity to integrate urban agriculture into urban design to foster more nutritious, sustainable, and equitable communal environments. Graciela Arosemena, author of Urban Agriculture: Growing Spaces for a Sustainable City, mentioned: “Urban gardens seek to increase nutritional food security for vulnerable populations, producing food for self-consumption in small spaces” [33].

4.4. Community Gardens: A Solution to Queretaro’s Food and Health Challenges

This research examines the food crisis from a perspective that ensures the current system’s nutritional challenges and ecological and economic impacts. Its significance lies in recognizing the causes of malnutrition and obesity in Queretaro, Mexico, and planning sustainable solutions such as community gardens. Among the leading hypotheses are the excessive processed foods and the abandonment of local agriculture as critical factors in the environmental health crisis.

The objective is to emphasize the need to produce local food through community gardens to promote communal self-sufficiency, improve nutritional quality, and reduce the ecological footprint. The conclusions denote that, while food production has been augmented, the quality and accessibility of food have been diminished, aggravating malnutrition and chronic diseases. While promoting self-production, community gardens are presented as a landscape-based urbanism approach to improving health and reducing environmental impacts.

4.5. Poverty in Queretaro

Cities with higher percentages in the Human Development Index (HDI) statistics often become migration centers, as in Querétaro. Despite its booming economic development compared to other parts of Mexico, Querétaro faces significant challenges due to poverty and marginalization that endangers the health and nutrition of its inhabitants. According to the National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policies, the municipalities with the highest concentrations of people living in urban poverty were identified as follows [23]:

- Querétaro, with 229,433 people (24.7% of its population);

- San Juan del Río, with 91,968 people (33.3% of its population);

- El Marqués, with 70,811 people (34% of its population).

4.6. Queretaro’s Site Findings

This study and design proposal reveal significant development disparities in Querétaro, where high poverty rates coexist with limited access to nutritious and affordable food, despite the region’s high Human Development Index and economic growth. The study considered population density, marginalization rates, and community needs. They identified San Antonio–Bolaños and Tlacote El Bajo as optimal locations for community gardens. San Antonio–Bolaños offers existing recreational infrastructure and connectivity but requires improvements in safety and accessibility. In contrast, Tlacote El Bajo offers diverse social interaction spaces that are suitable for local food production and community engagement.

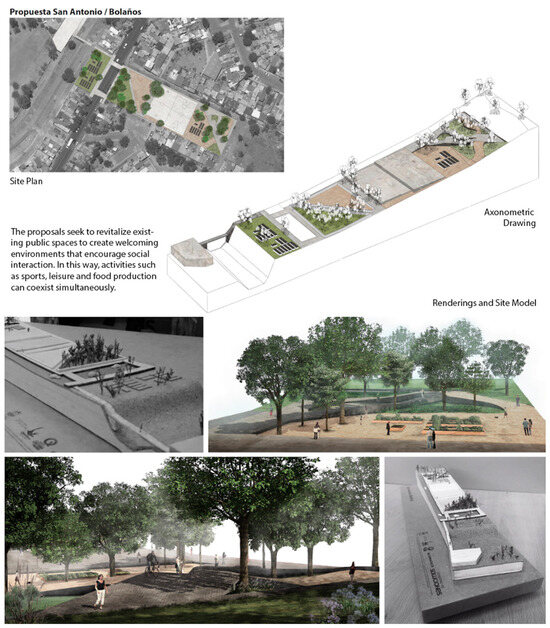

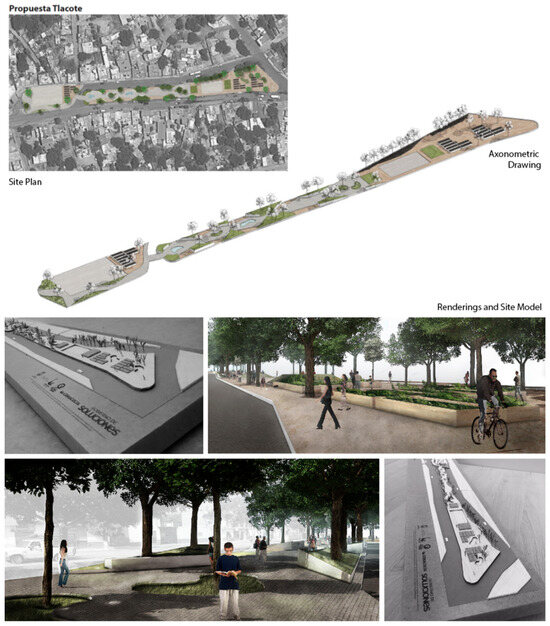

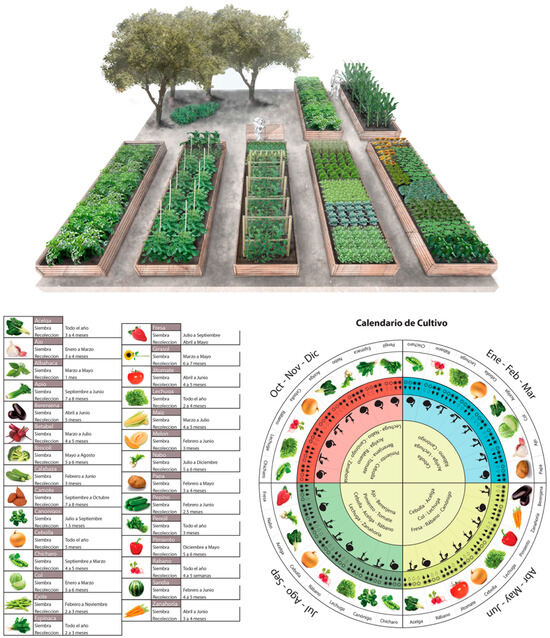

For both sites, a speculative project was developed to define the spatial and programmatic relationships that are complementary to the community garden. Through vision boards (Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12), we explored the possibilities of these programs in terms of spatial quality, integration, and landscape strategies. The speculative project is the experimental means to communicate the possible effects or impacts on the site.

Figure 10.

Landscape design proposal of community garden in San Antonio–Bolaños.

Figure 11.

Landscape design proposal for a community garden in Tlacote.

Figure 12.

Landscape design proposal of community garden and crop calendar.

Establishing community gardens in these locations aims to improve food security, revitalize public spaces, and encourage community participation, addressing the interrelated issues of poverty, health, and urban development.

Figure 10 shows the landscape design proposal for a community garden in San Antonio–Bolaños. This proposal transforms a public space, adding complementary sports and leisure programs to the community gardens. The advantage of this site is the existence of social interaction and community interest in revitalizing this area.

In the same way as Figure 10, Figure 11 shows the design proposal for a community garden in Tlacote. This project is located in an unutilized site that is highly connected and visible to the neighborhood. Furthermore, it includes complementary programs that generate new opportunities for interaction and regeneration of the site.

Figure 12 displays a possible crop calendar that could be applied to the different sites. Furthermore, the crop palette indicates periodic planting to introduce the first steps for increased seasonal eating.

5. Discussion

5.1. Development Disparities: Poverty and Malnutrition in Querétaro

Querétaro faces significant poverty challenges despite its high Human Development Index (HDI) and economic growth. CONEVAL (2012) data show high poverty concentrations in Querétaro, San Juan del Río, and El Marqués. [23] The analysis highlights the socioeconomic vulnerability and health risks in these areas, with a high percentage of the population living in poverty and having low access to nutritious and affordable food.

This research was conducted to identify potential sites for community urban gardens to address poverty-related health issues. The study was based on several criteria: population density, marginalization rates, social security access, infrastructure deficiencies, and community needs. More than 30 sites were considered. After a thorough evaluation, San Antonio–Bolaños and Tlacote El Bajo were selected. These sites were selected based on their potential impact and the possibility of improving food security and engaging the community.

5.2. Site Selection: Highly Connected Nodes and Existing Social Interaction (Activities)

For San Antonio–Bolaños, this area, located between San Antonio and Bolaños, has suitable public and green spaces but suffers from poor lighting and limited pedestrian access. It offers a good starting point for urban gardens due to its existing recreational infrastructure and community interest. The site benefits from urban connectivity and social interaction nodes, although the challenges include the need for improved safety and accessibility.

Tlacote El Bajo was selected for its centrality and potential for community engagement. The central plaza in Tlacote El Bajo features a mix of green space, sports facilities, and markets. Despite some problems, such as inadequate pedestrian crossings and conflicting uses of the space, the plaza’s existing infrastructure supports various activities, making it suitable for community gardens to promote local food production and social cohesion.

The need to address nutritional and socioeconomic challenges in marginalized areas of Querétaro led to the selection of San Antonio–Bolaños and Tlacote El Bajo for community gardens. Despite that, the project scope is not focused on evaluating methodologies to assess the garden’s influence on food security; this is perhaps one of the most interesting points to include in further research. Given the project’s scope and time limitations, there are significant opportunities for further research, including (1) developing an implementation strategy for community gardens according to the local legal, financial, and social conditions to face its potential implementation challenges, (2) a comparative analysis of Mexico or Latin America garden initiatives, and (3) to investigate the management models that could increase the resilience of the gardens within the communities.

These gardens are expected to improve local food security, revitalize public spaces, and foster community participation. In doing so, they will address the intertwined issues of poverty, health, and urban development.

5.3. Limitation of Analysis

This study and design proposal were initially developed in 2015–2016. Therefore, much of the data and statistics have changed, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, none of the projects were built and tested on-site. Likewise, in this study, food miles are mapped and tracked using price look-up codes (PLU) and the producer’s location. Therefore, tracking the food miles may differ if the food industry relies on third-party producers in different places.

5.4. Future Research

Research has suggested that community gardens provide both individual- and community-level benefits, directly and indirectly, across many domains, including physical, mental, economic, social, and civic [16]. However, further research should examine the long-term impact of community gardens on food security, health outcomes, and social cohesion in marginalized areas by using participatory approaches and assessing their scalability to other regions. Several studies have explored the effect of community gardens on nutrition and food security and could directly improve food security for low-income groups [32]. Further research is needed to identify the community’s barriers to implementing successful community gardens, especially in food swamp communities. If the implementation barriers are overcome, adding community gardens can significantly impact vulnerable neighborhoods by supporting sustainability and overcoming food swamps. Moreover, they can become public policies that, together with other strategies, improve the quality of life in communities.

6. Conclusions

Humanity has never produced so much food to solve malnutrition, nor has the world seen such obesity rates. Food insecurity has increased significantly during the last years, a trend exacerbated by a combination of factors, including the pandemic, conflict, climate change, and deepening inequalities [34]. It has been observed that the most vulnerable and marginalized populations have been most affected due to economic reasons and an obesogenic environment. Given that Mexico lives in conditions of scarcity, the percentages of overweight, malnourishment, and cardiovascular and degenerative diseases are increasing every year.

At present, increased urbanization, environmental degradation, population growth, and changes in food systems require a novel concept that considers the trade-offs between ecosystem services and disservices [35]. In addition, the transportation of food from distant places harms the planet. More than ever, it is necessary to consider growing food locally. Therefore, an alternative for today’s society is the self-production and self-consumption of food. Several civic initiatives promote urban agriculture or community gardens. They encourage the restoration of soil and climate on degraded lands worldwide. In the short term, it allows for the production of vegetables and medicinal, culinary, and aromatic plants. However, it also has environmental benefits and self-supplies products for participating families [36]. Urban community gardens could alleviate malnutrition, be a prevention and health improvement tool, and facilitate community cooperation. The challenge (and opportunity) is to design multifunctional urban agriculture spaces, matching residents’ specific needs and preferences while also protecting the environment [37].

The conclusions highlight the role of landscape urbanism, community gardens, and urban agriculture as strategies for social cohesion, sustainable food practices, and healthier urban environments. Many community garden projects are in vulnerable areas, but no studies have related them to obesogenic contexts and food deserts. In this sense, the specific contribution is given in reading and understanding the territory that reads, in addition to the socio-economic and spatial profile, which distinguishes spaces that already have an existing community structure and deteriorated or abandoned public spaces. This, then, supposes the significant impact and possible success in the medium- to long-term of the community gardens in transforming a food desert or an obesogenic environment. The research also contributes to the global conversation on urban agriculture by integrating concepts from landscape urbanism and community gardens. While European and American studies often emphasize sustainability and urban resilience, this initiative highlights the dual problem of obesity and malnutrition in the Mexican context. It links urban agriculture to public health and social cohesion and provides a conceptual framework for tackling food insecurity through community design and local food production.

Although land use policies determine the provision of infrastructure and facilities, this research shows that, although the provision of facilities such as public spaces or services is insufficient, the main challenge is their maintenance, as it still depends on the resources of the municipal government. In this sense, we identified an excellent opportunity to promote self-sufficiency programs and community participation in the recovery and maintenance of spaces with great potential to sustain community gardens. Regulations and public policies do not directly include providing spaces for urban agriculture. Instead, they leave the doors open for private supermarkets to locate in these contexts, regardless of the quality of their food. In the medium and long term, this would imply the conversion of these spaces from food oases into obsessive environments. On the other hand, this condition does not address the reduction of food miles and, therefore, does not promote a resilient food environment.

The specific role of convenience stores, focusing on processed foods, in perpetuating unhealthy diets and the increasing public health challenges in Mexico requires further investigation. Additionally, the concept of “food miles” and its implications for environmental sustainability and food security in urban areas like Querétaro has not received much research attention.

To solve the food contradiction of Queretaro’s abundance of food and malnutrition, this research proposes community gardens to lessen the dependency on processed foods while increasing access to healthier alternatives. The goal of the community garden projects in Tlacote and San Antonio–Bolaños is to improve people’s access to nutritious food, revitalize public areas, and encourage healthier urban settings. These efforts aim to improve people’s health and community engagement, upgrade public spaces, and regenerate the urban environment.

Author Contributions

Authors contribution: Introduction, R.P.-C. and D.G.-C.; Literature Review, R.P.-C. and D.G.-C., Materials and Methods, R.P.-C.; Results, R.P.-C. and D.G.-C.; Formal analysis, R.P.-C.; Investigation, R.P.-C.; Resources, R.P.-C. and D.G.-C.; Original draft preparation, R.P.-C.; Review and editing, R.P.-C., D.G.-C. and R.R.; visualization, R.P.-C.; funding acquisition, R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in INEGI at https://www.inegi.org.mx/ (accessed on 7 February 2025). These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: https://www.inegi.org.mx/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

Acknowledgments

Rodrigo Pantoja would like to thank Erik Sanchez for his valuable assistance in visualizing some of the computer graphics while working at EVO-A-LAB Arquitectura and Axel Solares, a former intern at Urban Lab Queretaro for GIS Maps.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frongillo, E.A.; Bernal, J. Understanding the Coexistence of Food Insecurity and Obesity. Curr. Pediatr. Rep. 2014, 2, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gucciardi, E.; Vahabi, M.; Norris, N.; Del Monte, J.P.; Farnum, C. The Intersection between Food Insecurity and Diabetes: A Review. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2014, 3, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wild, S.; Roglic, G.; Green, A.; Sicree, R.; King, H. Global Prevalence of Diabetes: Estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 2004, 27, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haslam, D.W.; James, W.P. Obesity. Lancet 2005, 366, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, P.; Kawar, B.; El Nahas, M. Obesity and diabetes in the developing world--a growing challenge. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 213–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, E.; Brunner, E.J.; Llewellyn, C.H.; Mindell, J.S. The retail food environment and its association with body mass index in Mexico. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barquera, S.; Rivera, J.A. Obesity in Mexico: Rapid Epidemiological Transition and Food Industry Interference in Health Policies. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 746–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, E.; OXXO se Pone Al Tú Por Tú con los Grandes. Economista 2011. Available online: https://www.eleconomista.com.mx/empresas/OXXO-se-pone-al-tu-por-tu-con-los-grandes-20110924-0042.html (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Morland, K.; Roux AV, D.; Wing, S. Supermarkets, Other Food Stores, and Obesity. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2006, 30, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirog, R.; Van Pelt, T.; Enshayan, K.; Cook, E. Food, Fuel, and Freeways: An Iowa Perspective on How Far Food Travels, Fuel Usage, and Greenhouse Gas Emissions; Iowa State University: Ames, IA, USA, 2001; Available online: http://large.stanford.edu/courses/2014/ph240/pope1/docs/pirog.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Pérez Neira, D.; Copena Rodríguez, D.; Delgado Cabeza, M.; Soler Montiel, M.; Simon Ferández, X. Cuántos Kilómetros Recorren los Alimentos Antes de Llegar a tu Plato. Análisis de la Presión Ambiental del Transporte de la Importación de Alimentos (Consumo Humano, Industria o Consumo Animal) en el Periodo 1995–2011. 2016. Available online: https://www.tierra.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/alimentos_kilometricos_2.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Murdoch, J.; Marsden, T.; Banks, J. Quality, Nature, and Embeddedness: Some Theoretical Considerations in the Context of the Food Sector. Econ. Geogr. 2000, 76, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Puente, A.L.; Peña-Portilla, D.G.; Alcalá-Reyes, S.; Rodríguez-Bustos, L.; Núñez, J.M. Changes in Food Environment Patterns in the Metropolitan Area of the Valley of Mexico, 2010–2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glanz, K.; Sallis, J.F.; Saelens, B.E.; Frank, L.D. Healthy Nutrition Environments: Concepts and Measures. Am. J. Health Promot. 2005, 19, 330–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roggema, R. Finding space for urban productivity. In The Coming of Age of Urban Agriculture; Roggema, R., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 27–47. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, E. To-Morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbusier, L. La Ciudad del Futuro, 5th ed.; Ediciones Infinito: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, F.L. When Democracy Builds; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1945. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock, N. Why Farm the City? Theorizing Urban Agriculture through a Lens of Metabolic Rift. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premat, A. State power, private plots and the greening of Havana’s urban agriculture movement. City Soc. 2009, 21, 28–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jettner, J.F. Community Gardens: Exploring Race, Racial Diversity and Social Capital in Urban Food Deserts. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, USA, 2017. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/community-gardens-exploring-race-racial-diversity/docview/1910863416/se-2 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Pobreza a Nivel Municipio 2010-2020. CONEVAL. Available online: https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/Paginas/Pobreza-municipio-2010-2020.aspx (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- PLAN 2050 Plan Estratégico del Municipio de Querétaro a Largo Plazo. 2020. Available online: https://implanqueretaro.gob.mx/v2/ot/p2050-inicio (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Embelleciendo Querétaro: Mi Querétaro Lindo. Available online: https://oem.com.mx/diariodequeretaro/local/supervisa-nava-obras-de-urbanizacion-en-la-colonia-las-plazas-13094306. (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Krusky, A.M.; Heinze, J.E.; Reischl, T.M.; Aiyer, S.M.; Franzen, S.P.; Zimmerman, M.A. The Effects of Produce Gardens on Neighborhoods: A Test of the Greening Hypothesis in a Post-Industrial City. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 136, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kodmany, K. Supporting Imageability on the World Wide Web: Lynch’s Five Elements of the City in Community Planning. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2001, 28, 805–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B. Embodied Connections: Sustainability, Food Systems, and Community Gardens. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 509–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J. Urban Community Gardens as Multimodal Social Spaces. In Greening Cities; Tan, P.Y., Jim, C.Y., Eds.; Advances in 21st century Human Settlements; Springer: Singapore, 2017; pp. 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, M.P. Growing What You Eat: Developing Community Gardens in Baltimore, Maryland. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 1232–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Reardon, T. Obesity and the Food System Transformation in Latin America. Obes. Rev. 2018, 19, 1028–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Calls on Countries to Reduce Sugar Intake Among Adults and Children. News. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/04-03-2015-who-calls-on-countries-to-reduce-sugars-intake-among-adults-and-children (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Arosemena, G. Agricultura Urbana: Espacios de Cultivo Para una Ciudad Sostenible; Editorial Gustavo Gili: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Sustainable Development. Goal 2: Zero Hunger; United Nations Sustainable Development: New York, NY, USA; Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/hunger/ (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Russo, A.; Cirella, G.T. Edible urbanism 5.0. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, M.; Toxrres, M.A. El origen del jardín mexica de Chapultepec. Arqueología Mexicana. 2002, 10, 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lovell, S.T. Multifunctional urban agriculture for sustainable land use planning in the United States. Sustainability 2010, 2, 2499–2522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).