Abstract

Sustainable community development is a prerequisite for national parks’ coordinated ecological and socio-economic development. This study analyzes the sustainable development challenges communities face in national parks, including the marginalization of indigenous peoples, the passive role of stakeholders, and insufficient protection of community interests. Using a grounded theory approach and a mixed research method (semi-structured interviews and questionnaires), the development constraints of community residents in Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park in China were systematically studied. The research framework identified five core dimensions (economic, social, ecological, institutional, and cultural) and eight major categories that characterize the community’s development dilemma. The analysis revealed systemic problems, including differences in income distribution, limited access to resources, gaps in policy implementation, and ambiguous stakeholder roles. A new framework for coordinated development of national park communities was constructed through multidimensional analysis, and coordinated development strategies were proposed from the five dimensions of economy, society, ecology, institution, and culture. These findings contribute to the theoretical underpinnings of national park governance in China and offer a transferable methodological system for managing nature reserves and national parks worldwide, particularly in achieving a balance between ecological protection and community development needs.

1. Introduction

In the face of escalating global climate change and the ongoing degradation of ecosystems, environmental protection has emerged as a paramount concern for the international community [1]. National parks, as effective instruments of ecological protection, embody a crucial mission to safeguard natural resources, maintain ecological balance, and foster sustainable development [2]. A global trend is evident, and numerous countries and regions are fortifying their ecological protection measures by establishing national parks. However, a prevailing challenge confronting numerous national parks is balancing ecological protection and socio-economic development [3,4,5]. This predicament not only jeopardizes the stability of the ecosystem but also endangers the economic interests and livelihood security of local communities [6].

In light of the aforementioned challenges, the sustainable development of the national park community has emerged as a pivotal strategy to promote the coordinated ecological protection and socio-economic development of national parks [7]. The successful practices of numerous countries have yielded invaluable insights. A notable example is the Akan Mashu National Park in Japan, which has attained a harmonious balance of multiple interests by implementing a stakeholder governance system that seamlessly integrates the lives of residents, agriculture, and forestry with park management [8]. Mount Elgon National Park in Uganda has adopted an ecotourism strategy, fostering collaboration between local governments and communities [9]. Udawalawe National Park in Sri Lanka has enhanced local community support for conservation measures through revenue generation. Sharing and tourism cluster development [10] in the Great Himalayan National Park has promoted ecological protection and economic development through community awareness and capacity building [11].

Since 2015, China has gradually established a national park system [12] and has accumulated considerable experience in promoting the sustainable development of national park communities to balance ecological protection and local economic development, achieving substantial results. For instance, the Sanjiangyuan National Park has proposed to enhance community participation through an optimized management and compensation mechanism [13]; the Wuyishan National Park has promoted regional coordination and community governance capacity improvement through a multi-scale community planning framework [14]; and the Zhangjiajie National Park has promoted the coordinated development of ecology and economy through an innovative unified management system [15]. These cases demonstrate that community sustainable development plays a pivotal role in coordinating national parks’ ecological protection and socio-economic development. As one of the inaugural national parks in China, Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park is endowed with the unique ecological resources of a tropical rainforest and is confronted with considerable pressure to promote coordinated socio-economic development of ecological protection. Consequently, there is an urgent need to study and determine sustainable development strategies for Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park communities.

A considerable body of scholarship has emerged on sustainable development strategies for national park communities, drawing upon various theoretical frameworks. Adaptive management theory places significant emphasis on implementing flexible governance strategies, positing that dynamic adjustments can engender mutually beneficial outcomes [16]. However, this theory neglects the intricate interplay between culture and stakeholders. The social capital theory advocates for community cooperation and posits that robust social capital can promote conservation [17], yet it does not adequately consider the role of external stakeholders. The sustainability theory advocates for a “conservation first, business-assisted” model [18], but protecting public interests can be challenging.

In contrast, grounded theory, as a qualitative research method, emphasizes a “bottom-up” approach, abstracting concepts from actual data and gradually building a theoretical framework. After data collection, researchers go through stages such as open coding, axial coding, and selective coding, revising the theory iteratively until data saturation is reached [19]. Ultimately, comparing the formed theory with the existing literature can verify its scientific validity and applicability. Its core strength lies in its ability to provide insights into the underlying mechanisms of complex social phenomena, making it particularly suitable for studying multiple stakeholders and dynamic interactions. Grounded theory does not rely on preconceived assumptions; rather, it generates more general theories by continuously comparing and inductively analyzing data to discover participants’ behavioral patterns, cognitive structures, and their interrelationships. Therefore, it is particularly effective in addressing complex social systems and environmental governance issues involving multiple, interconnected interests.

In the study of national parks, grounded theory can effectively reveal the interactions between governments, communities, and enterprises, providing a deeper understanding of the formation of ecological conservation intentions and their relationship with governance models [20,21]. Specifically, in the case of Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park, grounded theory can offer a clear framework to help identify and address key governance issues by analyzing the conflicts between the actual needs of local communities and environmental protection policies. Its participatory and inductive characteristics enable it to comprehensively consider local culture, community interests, and the role of external stakeholders, thereby providing strong support for the sustainable development of the national park.

This study focuses on the sustainability challenges faced by national park communities. Using a grounded theory approach and a mixed research method (semi-structured interviews and questionnaires), it focuses on the sustainability of ecological protection in China’s Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park and the interaction of multiple stakeholders within the park [22]. The study systematically analyzes and studies the limiting factors of national park community development and proposes a coordinated development strategy for national park communities. This strategy encompasses five dimensions: economic, social, institutional, ecological, and cultural. The study provides a theoretical basis for China’s national park governance and a transferable methodology for managing protected areas worldwide. This methodology is instrumental in balancing ecological protection and community development needs.

2. Overview of the Research Area and Methods

2.1. Overview of the Research Area

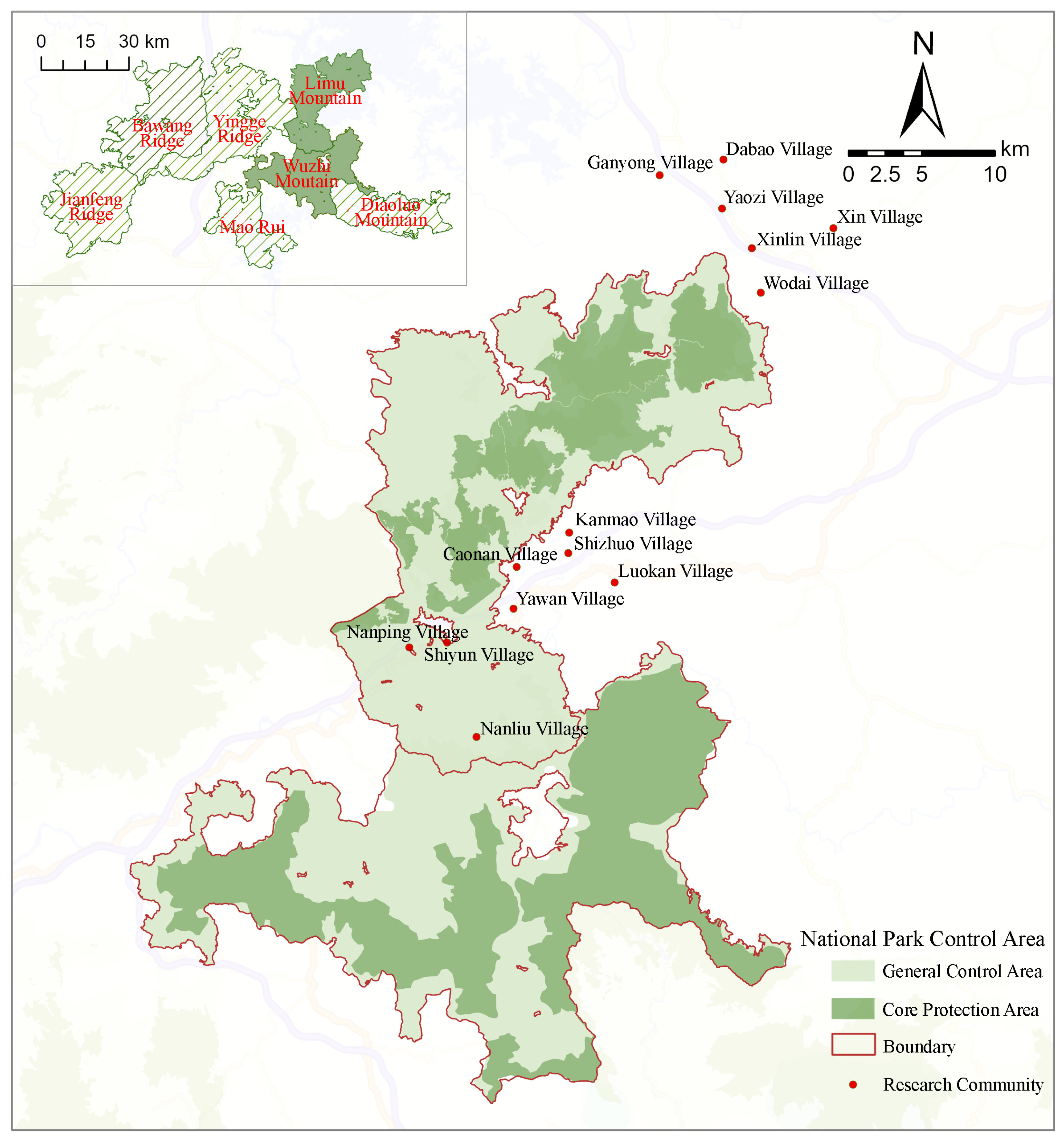

Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park, one of the first national parks established in China, is located in the south-central region of Hainan Island (108°44′–110°04′ E, 18°33′–19°14′ N). The park spans a total area of 4403 km2 and encompasses seven National Park control areas: Jianfeng Ridge, Bawang Ridge, Yingge Ridge, Diaoluo Mountain, Wuzhi Mountain, Lmu Mountain, and Mao Rui. Its rich natural resources and ecological functions make it immensely significant in developing China’s national ecological civilization.

The region’s tropical monsoon climate (24 °C to 25 °C annual mean temperature and 1500 to 2500 mm annual precipitation) fosters the growth of tropical rainforests due to its high humidity, concurrent rainfall, and heat. The region’s topography is predominantly mountainous, with an altitude range of 200 to 1867 m. Notable peaks within the area include Wuzhi Mountain and Limu Mountain. The park has a sophisticated water system, with the Nandu, Changhua, and Wanquan rivers serving as its primary water sources. The region boasts a rich biodiversity, with a significant forest coverage that nurtures various rare species, including the Hainan gibbon and Hainan tallow tree. This makes the area of great ecological conservation value.

This study focuses on the Limu Mountain area (109°31′–109°49′ E, 18°54′–19°14′ N) and Wuzhi Mountain area (109°32′–109°49′ E, 18°42′–18°59′ N), where the issues of ecological protection and balanced socio-economic development are most prominent (Figure 1). The permanent population of the research area is approximately 24,300, with the majority of residents belonging to the Li and Miao ethnic groups. Both groups possess a rich cultural heritage and distinctive folk traditions passed down through generations, remaining well preserved. The primary sources of livelihood for local residents include agriculture, forestry, and the emerging sectors of tourism and services. Agriculture and forestry remain the main economic pillars, with most households relying on these industries for their income. In recent years, tourism has increasingly become an important supplementary source of income, driven by the region’s unique natural landscapes and cultural resources. While the local way of life remains closely linked to traditional industries, the service sector is gradually becoming a significant driver of economic growth as the region continues to develop. The sample sites were determined based on the distance from the forest park, the impact of ecological policies, and the convenience of research. This involved seven townships (Limu Mountain Town, Hongmao Town, Shiyun Township, Maoyang Town, Tongshi Town, Shuiman Township, and Nansheng Town). The scope of the research included typical villages such as Shiyun Village and Nanping Village, which are close to the core protection area of the national park, and villages far away from the core protection area (such as Xin Village and Dabao Village).

Figure 1.

Location of the study area.

2.2. Data Sources

The study’s data sources included questionnaires administered to residents in and around the Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park and semi-structured interviews with business representatives and government staff. The aim was to gain a comprehensive understanding of the multidimensional impact of ecological protection policies on community residents, businesses, and government governance at the grassroots level.

The questionnaire survey was conducted using purposive sampling in the Limu Mountain and Wuzhi Mountain areas from 14 December 2023 to 19 January 2024 in seven townships (Limu Mountain Town, Hongmao Town, Shiyun Township, Maoyang Town, Nansheng Town, Shuiman Township, and Tongshi Town). A total of 192 resident questionnaires were collected. The content of the questionnaire encompassed four domains: (1) the economic livelihoods of the residents’ families; (2) social and cultural conditions; (3) perceptions of the ecological environment; and (4) willingness to participate in the coordinated development of the community. The theoretical sampling method was employed to select the households to be interviewed. The village committees were responsible for referring representative industrial households to ensure an even distribution of respondents across the study area and comprehensive coverage of the industrial sector. This approach was adopted to maximize the potential for mining relationships between concepts. Each household was interviewed with the assistance of a single representative.

To further ensure the depth and diversity of the research, 20 semi-structured interviews were conducted with business representatives and government staff. The interviews focused on the impact of ecological protection policies on the lives of community residents, the production of business operations, and grassroots governance by the government. The interviews also explored the responses and feedback of various stakeholders in policy implementation. To ensure the comprehensiveness and representativeness of the data, the interviewees were divided according to group attributes (community residents, business representatives, and government staff) while also focusing on the differences and uniqueness of the positions of different groups in adapting to the policies.

2.3. Data Processing

2.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The population under study included 56.8% male respondents and 71.3% between the ages of 30 and 60. Regarding income, 60.4% of the respondents’ families earned less than 20,000 yuan per year, and 63.5% of the residents relied on forestry as their primary source of income. In comparison, only 10% relied on tourism. This indicates that the community’s economy depends significantly on forestry, making it vulnerable to external shocks. Furthermore, the overall educational level of the residents was found to be relatively low, mainly concentrated in junior high school and below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the surveyed population.

Among the surveyed enterprises, 31% were agricultural enterprises, 38% were cultural tourism enterprises, and 31% were accommodation and catering enterprises. The seven government staff interviewed were all engaged in work related to national park ecological protection and cultural tourism in towns and villages (Table 2).

Table 2.

Basic information on other interviewees.

2.3.2. Grounded Theory

This study used grounded theory for coding, verified the sufficiency of the data and the robustness of the conclusions through the saturation test, and combined it with descriptive statistical analysis and graphical display to further support the scientific rigor and representativeness of the study. The remaining data were coded using Nvivo 11.0 software to abstract relevant concept categories and form a theoretical framework for the research objectives.

Open Coding

Open coding is the preliminary data analysis stage, which aims to conduct a detailed word-by-word analysis of interview and questionnaire data. The main objective of open coding is to extract concepts and categories with similar meanings from the raw data. Through repeated readings and annotations of the textual data, core factors affecting the transformation of community residents in the context of national park policy in Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park were identified. In this process, sixteen initial categories (Table 3) covering different social, economic, and ecological factors were summarized. Each category was carefully analyzed and conceptualized to ensure that it reflected the key themes in the raw data, laying the foundation for subsequent construction of the theoretical framework.

Table 3.

Concepts and categories of open coding formation.

Axial Coding

The axial coding stage not only helped organize and integrate the data but also clarified the connections between different variables, laying the foundation for a more systematic theoretical framework. Axial coding ultimately reduced the sixteen initial categories to eight main categories based on the paradigm model, with each main category consisting of a logical axis (Table 4). For example, in the context of differences in the distribution of benefits (the context in which the phenomenon occurs), by improving the mechanism for the distribution of benefits (management actions or plans implemented for this context), such as promoting ecological compensation policies and establishing an institutionalized pension system, residents’ sense of gain can be enhanced, and the economy can be driven towards sustainable development (the result of actions). The relationship between these categories is integrated into the same main category—“economic development motivation”.

Table 4.

Results of axial coding.

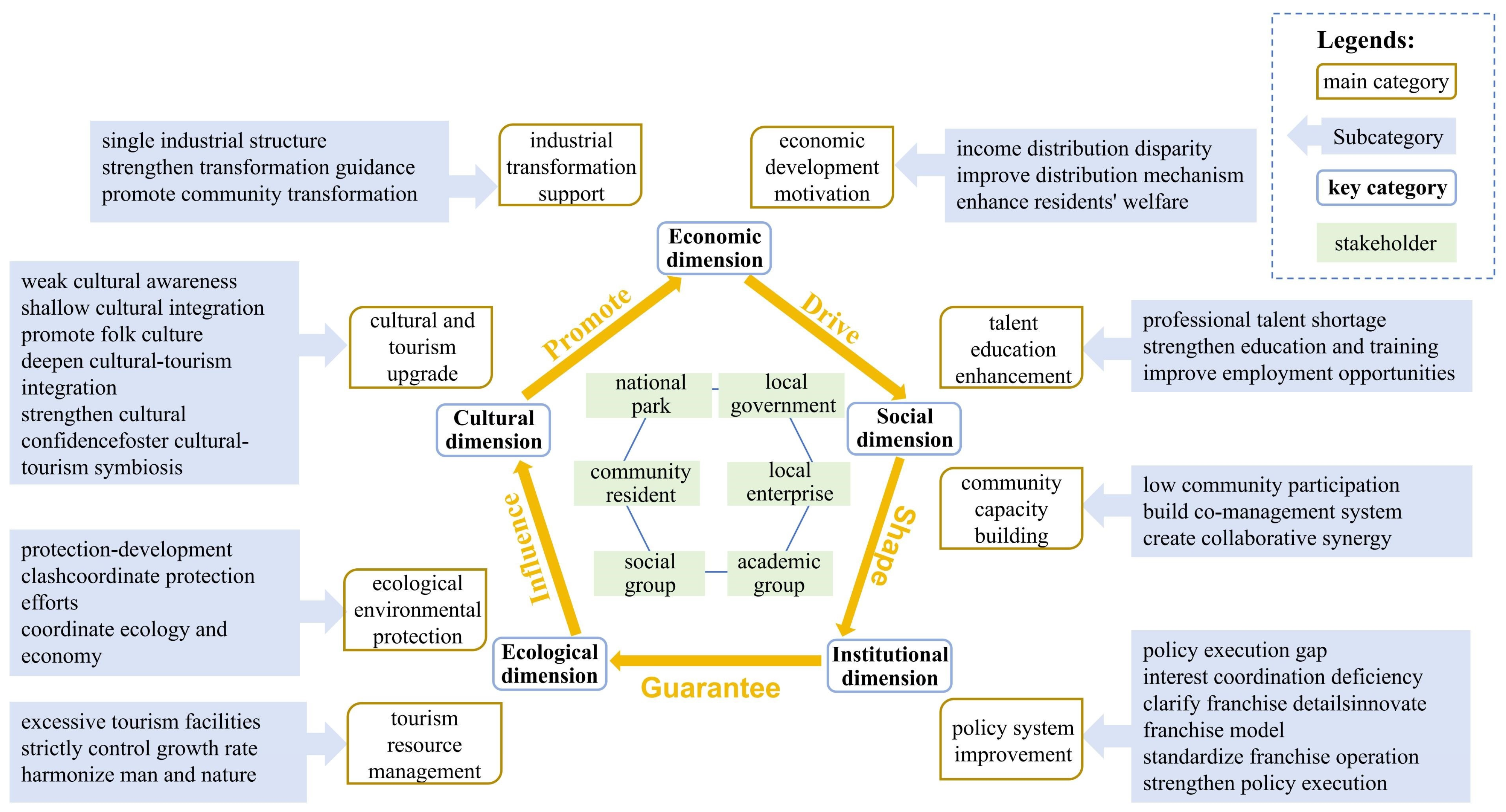

Selective Coding and Saturation Testing

Selective coding further extracted key categories from the conditions, coping strategies, and outcome paths identified in the main categories and systematically linked them with other categories and explained their interrelationships. This was ultimately summarized into five core dimensions: economic, social, institutional, ecological, and cultural (Table 5). Categories with incomplete conceptualization were supplemented to generate a coordinated development model for the national park community (Figure 1). In this process, three interview transcripts were extracted for reanalysis, and the results showed that no new core concepts were found in the coding process, confirming the theoretical saturation. This test ensured the integrity and stability of the research’s theoretical framework at the data level.

Table 5.

Coding results for grounded theory.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Overall Analysis of the Development Dilemma of the National Park Community

Grounded theory, employing open coding and axial coding analysis, was utilized in the study to reveal the main development dilemmas faced by the Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park community in the five core dimensions of economy, society, ecology, institutions, and culture. Among these, economic issues accounted for 42.85% and represent the key bottleneck restricting the coordinated development of the community. This issue is pervasive, manifesting in several ways, including income distribution disparities, a single industrial structure, and a dearth of technology and capital. These factors collectively hinder the community’s capacity for sustained development.

In the dimensions of society, ecology, institutions, and culture, issues such as low resident participation, passive roles of stakeholders, gaps in policy implementation, restrictions on resource access, and insufficient integration of culture and tourism further exacerbate economic development challenges. Specifically, community residents’ lack of organizational capacity and skill levels limits the effective integration and efficient utilization of resources. The ambiguous role positioning of stakeholders makes it difficult to establish effective co-management mechanisms. The conflict between ecological conservation goals and economic commercialization demands intensifies resource development restrictions. Complex policy approval processes and the slow implementation of franchising policies significantly delay the progress of economic projects. Weak awareness of preserving traditional folk culture and insufficient support for cultural protection projects pose significant challenges.

3.2. Sub-Dimensional Analysis of the Dilemma of Community Development in National Parks

3.2.1. Economic Dimension

Economic issues are widely recognized as a core obstacle to community development [23]. Although the rapid development of the tourism industry has brought employment opportunities and increased consumption (7.41%), problems such as differences in income distribution (8.99%), a single industrial structure (8.99%), and insufficient subsidies for traditional agriculture (6.35%) remain prominent and have failed to improve the economic situation of the residents significantly. Many parks are in poverty-stricken areas, and residents have long relied on natural resources for survival. However, land expropriation or restricted land use to protect resources has forced many to abandon traditional agricultural practices [24], such as betel nut and rubber cultivation, further exacerbating the decline of traditional industries. The existing compensation system is unsustainable [25]. It fails to guarantee long-term benefits, which, if they do not outweigh the costs, may lead to conflict and undermine support for park management [26]. Moreover, although the commercialization of tourism and the expansion of specialty product sales channels are considered key catalysts for economic development, the absence of a mechanism to regulate tourism revenue has led to a general perception among interviewees that current economic returns are insufficient to meet basic needs or yield a benefit.

3.2.2. Social Dimension

A community is a group of people with a particular historical residence within or around a national park who share a standard value system, cultural characteristics, and common interests. The production and life of community residents have long depended on local natural resources, forming an environmentally friendly production method and an ecological culture that respects nature. However, the current relevant regulations do not clearly define the positioning and role of the community in the construction and management of national parks, resulting in the community’s subjective initiative in participating in the construction and management of national parks not being fully utilized, which restricts the coordinated development of ecological protection and social economy in national parks. Interview data show that 71% of government staff surveyed believed that the roles of the park, community, enterprises, and local government in promoting ecological protection and sustainable community economic development in the national park are not clearly defined and that an effective co-management mechanism has not been established. In addition,4.76% of residents surveyed pointed out that although the government has strengthened its efforts to organize cultural education and skills training for community residents, the current cultural education level and vocational skills portfolio of community residents cannot meet the needs of the community-led industry’s transformation into a high value-added industry. The lack of innovative and professional talent has weakened the intrinsic development momentum of the community economy.

3.2.3. Ecological Dimension

Although the ecological protection policy has improved the quality of the environment (4.76%), it has also severely restricted local economic development. Accordingly, 6.67% of the respondents pointed out that tourism development, while promoting economic development, has also increased the pressure on environmental protection. With the increase in tourists, many tourist accommodation services such as homestays and farm stays have been built in national parks (7.94%), seriously affecting the ecological environment. Without other employment support and industry guidance, some residents in national parks have taken the opportunity to renovate their own houses to build a large number of homestays and farm stays quickly. During the construction process, the area’s natural topography and forest vegetation have been significantly disrupted. The generation of substantial solid waste residues further exacerbated the adverse impacts on the local ecological environment. Moreover, the influx of tourists has intensified environmental pressures. Waste left by visitors is often not promptly cleared, undermining the natural landscape and ecological balance of the national park.

3.2.4. Institutional Dimension

The insufficient implementation of policies and ineffective coordination of interests have further constrained regional economic development. During interviews, respondents highlighted that the complexity of policy approval procedures and land use restrictions have hindered the realization of economic benefits. Due to the stringent protection redlines of the national park, land use and commercial activities are subject to strict controls (8.47%), with production and business operations permitted only through franchising mechanisms. However, the current implementation framework of the franchise policy remains ambiguous and impractical, characterized by a lack of clear access standards, a relatively narrow scope of permissible projects, and an incomplete exit mechanism for franchisees (7.41%). These shortcomings have significantly dampened the investment enthusiasm of local businesses and individual operators. For instance, restrictions on the approval of projects such as the expansion of recreational facilities and the construction of owner-occupied housing have limited the full potential of local ecotourism development. Consequently, there is an urgent need to clarify the operational details and guidelines of the franchise policy, streamline the approval process, provide more transparent investment frameworks for businesses and individual operators, and foster sustainable economic growth.

3.2.5. Cultural Dimension

The inadequate preservation of traditional folk culture and the underdevelopment of cultural resources have significantly constrained the economic potential of the local cultural tourism industry, and 9.52% of respondents noted that despite the increasing commercialization of tourism, the integration of local cultural resources with tourism remains superficial, leaving the economic value of the traditional cultural industry largely untapped. Concurrently, the socio-economic and cultural foundations essential for sustaining traditional folk culture have been eroded, depriving it of its nurturing environment. The forces of urban modernization have contributed to the gradual erosion of traditional folk culture, while excessive commercial development has further undermined its foundational elements. The decline in community populations and resident numbers has also weakened the social base necessary for transmitting traditional folk culture. During community construction and development, historical buildings and cultural relics have suffered damage or destruction, and community residents’ recognition of the value of traditional folk culture has diminished. Furthermore, awareness of the need to protect and inherit traditional folk culture remains insufficient.

3.3. Community Coordinated Development Model Construction

In response to the sustainable development challenges faced by national park communities, this study constructed a new framework for coordinated community development in Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park (Figure 2). The framework aims to foster the sustainable development of communities within the Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park by integrating and interacting cross-dimensional factors, ultimately achieving a win–win outcome of ecological conservation and local economic development. The model proposes a coordinated development strategy centered on five core dimensions: economic, social, ecological, institutional, and cultural. In the sustainable development process of national park communities, these five dimensions interact synergistically to advance governance: the economic dimension provides the material foundation for communities and drives social progress; the social dimension ensures that economic benefits are equitably distributed among residents and enhance social well-being; the ecological dimension regulates development activities and ensures the sustainable utilization of resources; the institutional dimension establishes regulatory safeguards and promotes coordinated development across dimensions; and the cultural dimension strengthens community identity and provides spiritual motivation. This strategy offers theoretical support and practical pathways for the sustainable development of national park communities. It emphasizes the integration of cross-dimensional resources and policy coordination, balances the interests of all stakeholders, and facilitates the achievement of sustainable governance objectives.

Figure 2.

A new framework for coordinated community development in Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park.

3.3.1. Economic Dimension: Improve the Benefit Distribution Mechanism and Strengthen Industrial Transformation Guidance

To solve the core problems in the development of community economies, it is necessary to improve the benefit distribution mechanism gradually. Based on strengthening the minimum living guarantee for community residents and providing more employment opportunities, efforts should be made to increase ecological protection compensation further. It is necessary to explore establishing a social pension security system for parks and include eligible indigenous people in the scope of the minimum living guarantee. It is necessary to explore establishing a benefit coordination mechanism for residents to participate in ecological protection. The management and protection positions in various existing protected areas should be unified into ecological management and protection public welfare positions, and the scale of public welfare positions should be set reasonably, prioritizing the employment of residents with labor in core protected areas and ecological restoration areas. It is necessary to study and introduce an ecological compensation mechanism for national parks, exploring the establishment of a sustainable and innovative ecological protection compensation mechanism that focuses on financial compensation and is supplemented by compensation methods such as technology, in-kind compensation, and employment to standardize and institutionalize ecological compensation and promote a shift in attitude among community residents from “I am being asked to protect” to “I want to protect”.

At the same time, for the guidance of industrial transformation, stakeholders should study and introduce a national park industrial guidance mechanism. The government should strengthen financial subsidies, technical training, and market support; actively guide the community to develop industries with characteristic ecological products such as forest undergrowth economy, rainforest tourism, forest health care, and mountain outdoor sports; guide the national park community to transform the primary industry, restrict the secondary industry, and focus on developing the tertiary industry; promote the transformation of community development; and promote the implementation of the concept of “lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets”. In the process of industrial transformation, villages can follow the example of Shihui Village to strengthen characteristic planting industries, develop ornamental orchid cultivation, and combine the “government + enterprise + farmer” model to create an “industry + tourism + sales” industry chain. Villages can also learn from Mao’na Village to upgrade farmhouse tourism, promote the integration of tea tourism, explore Li culture, and develop experiential projects such as tea picking and tea making to form a “culture + ecology + tourism” model. Villages can also learn from the standard system of the Japanese “Forest Therapy Society” [27], highlight forest health projects, and develop industries such as eco-hiking and eco-resort cabins to meet the daily leisure needs of urban residents.

3.3.2. Social Dimension: Build a Community Co-Management System and Strengthen the Education and Training of Talent

Community participation is a prerequisite for sustainable conservation [28]. Community co-management is a management model in which the community assumes specific responsibilities for protecting and utilizing natural ecological resources within a specific scope and agrees that the sustainable use of these resources will not conflict with the relevant goals of nature and ecological protection [29]. Establishing a community co-management system is key to the sustainable development of the national park community. It is necessary to clarify the role of relevant stakeholders further and encourage the establishment of a community co-management committee with the participation of stakeholders such as the national park, local government, community resident representatives, business representatives, and social groups to jointly manage community public affairs and participate in national park decision making and planning, ensuring that residents obtain economic, social and other benefits during the participation process [30] and forming a community co-management mechanism for national parks that “jointly makes decisions, plans, uses, and protects”. With the national park as the overall planner, the local government as the policy implementer, local enterprises as development promoters, community residents as direct participants, academic groups as the proponents of science, and social groups as ecological advocates, a mature mechanism can be established with an efficient operation and reasonable institutional framework. This promotes the integration of resources and the balancing of interests, ultimately achieving a win–win situation for ecological protection and economic development.

Cultivating ecological protection concepts and providing vocational skills training for all community residents is necessary [31]. In order to enhance the ability of community residents in national parks to participate in ecological protection and tourism services, a three-in-one training system of “basic + special + practical” needs to be constructed. First, nature education courses should be offered to all residents to popularize basic knowledge of ecological protection, garbage sorting, and emergency rescue skills and enhance environmental awareness. Second, tailor-made training should be provided to meet different needs: for residents interested in participating in tourism services, courses such as eco-tour guiding, homestay management, and handicrafts making should be offered to improve service capabilities; for residents planning to participate in franchise projects, training in business operations, financial management, marketing, etc., should be provided to enhance management capabilities; for residents interested in ecological protection, professional training in the use of infrared cameras, species identification, patrolling skills, etc., should be provided to cultivate local ecological management and protection capabilities. At the practical level, the joint venture and scientific research institutions have set up practical training bases, such as the Maona Village Tea Tourism Integration Project and the Shihui Village Orchid Plantation Base, to enable residents to improve their skills in practice. At the same time, a “training + employment” articulation mechanism must be implemented, whereby outstanding trainees are given priority in being recommended for employment in franchise enterprises or ecological conservation positions.

3.3.3. Ecological Dimension: Comprehensively Coordinate the Overall Conservation Pattern and Strictly Control the Growth of the Economy While Transforming and Repairing It

The principle of giving equal consideration to ecological restoration and social and economic development should be followed [32]. The ecological protection pattern inside and outside the park should be comprehensively coordinated through relocation and reconstruction by the functional positioning of protecting scientific research, education and recreation, and community development. Within the park, ecological resettlement of the original inhabitants of the core area should be gradually implemented, with the removal of production facilities; outside the park, the surrounding industrial structure should be adjusted, gradually eliminating industries that do not conform to the main functional orientation of the region and are not conducive to ecological protection. We must adhere to the concepts of intensification, integration, and greening; build characteristic towns and beautiful villages according to local conditions; improve supporting functions such as concentrated residence, medical education, business, and tourism; and preserve the history, culture, and folk customs of the park’s location. A comprehensive review of current ecological protection policies should be conducted, management tools should be dynamically adjusted, and non-depleting use of resources should be appropriately carried out to obtain benefits without harming the environment. For the ecological conservation areas and core areas of the national park, on the premise of not affecting protection, consideration can be given to designating a certain area within acceptable limits as a recreational display area, constructing a minimum of necessary facilities, and creating more opportunities for surrounding communities to participate in and develop eco-tourism. To balance conservation and utilization, both rigid control and flexible guidance need to be implemented simultaneously: on the one hand, the scope and scale of activities can be limited through electronic fences and dynamic monitoring systems for visitor carrying capacity; on the other hand, an “ecological points” system could be designed to give discounts on admission tickets or priority for licensed experience programs to tourists who travel low-carbon and recycle their trash, forming a dual mechanism of “restraint–incentive”.

Systematic governance measures are essential to address the ecological damage caused by the unregulated construction of homestays and farm stays in national parks. First, a classified remediation approach can be implemented for existing facilities: illegally constructed homestays that severely damage the ecology should be demolished and reclaimed by the law, prioritizing replanting native tree species and restoring the terrain. Proceeds from surplus construction land indicators trade can be used to compensate residents for resettlement. For legally compliant homestays with sewage issues, the installation of sewage treatment systems must be mandatory, and they should be included in franchising supervision, requiring regular garbage disposal and zero direct sewage discharge. Second, incremental development must be strictly controlled by designating no-build and limited-build zones for homestays based on ecological carrying capacity assessments. A franchising access system can be established, permitting only professional enterprises to build low-carbon homestays that are also responsible for ecological restoration in surrounding areas. At the same time, industrial substitution can be promoted by guiding residents toward undergrowth cultivation, ecological management, and protection roles and the development of non-heritage handicrafts, thereby reducing their reliance on the homestay economy through skills training and financial support. Additionally, an intelligent monitoring system can be put in place, combining satellite remote sensing and uncrewed aerial vehicles to patrol for violations. A community oversight system may also be established to encourage residents to report environmental violations in exchange for rewards. Lastly, a special ecological restoration fund should be established, with funds proportionally extracted from homestay operation revenues for vegetation restoration. The reclaimed area can be incorporated into the carbon sink trading system, and future profits should be allocated to benefit local residents, creating a sustainable governance loop of “remediation–transformation–restoration–benefit” to achieve the dual goals of ecological protection and improved livelihoods.

3.3.4. Institutional Dimension: Clarify the Details of the Franchise and Innovate the Franchise Model

Concessions play a key role in managing nature reserves and national parks. However, concessions in some protected areas in China create problems such as monopolization, homogeneity, and information opacity [33], resulting in higher social costs for local governments. At the same time, companies have received disproportionate returns [34]. Although the concession policy framework already exists, it must refine its implementation rules to ensure accurate implementation and effective enforcement. It is necessary to further clarify the implementation rules for concessions; improve the mechanisms for concession authorization and access, benefit distribution, supervision, and management, etc., from multiple perspectives; introduce a “negative list” system of strictly prohibited matters and a temporary takeover system in the event of project interruption or termination; introduce specific implementation measures around the subjects of franchise authorization, revenue distribution, ticket management, and agreement signing; further clarify the franchise authorization procedures, contract content, and other content; establish a comprehensive supervision system with the National Park Administration at its core, supplemented by local agencies and third-party institutions; pay attention to the public supervision role of groups such as indigenous people and tourists; and strengthen specific policy guidance for implementing departments and enterprises.

In the innovation of the franchising model, franchising projects need to be classified according to the overall plan and ecological protection goals into prohibited categories (such as highly polluting industries), restricted categories (accommodation and catering, tourism, and transportation that require bidding), and encouraged categories (low-impact projects such as merchandise sales and nature education). For example, priority should be given to guiding residents or enterprises to participate in franchising projects, allowing communities to operate mushroom cultivation, orchid tourism, and other low-ecological impact businesses directly, and exempting them from the bidding process. Residents should be supported in business activities such as forest economy and farming experience in suitable areas, and all parties should be encouraged to participate in activities such as nature education, ecological experience, and science popularization and education. At the same time, the development of characteristic towns should be guided and supported in communities surrounding or at the entrances to national parks to improve the level of public services and promote the deep integration of ecological protection and community development.

3.3.5. Cultural Dimension: Popularize Folk Culture and Promote the In-Depth Integration of Culture and Tourism

It is essential to promote folk culture education actively. Folk culture content should be incorporated into physical education, art teaching, and extracurricular activities at all educational stages. Folk culture operation and performance skills should be developed, especially in ethnic minority regions, where high-quality traditional cultural education courses should be introduced. Modern resources for the practice of new-era civilization should be explored within the traditional folk culture to achieve its creative transformation and innovative development. This will allow ethnic minority students to deepen their understanding and recognition of their own traditional culture, thereby cultivating their sense of national cultural pride and confidence. Local governments should increase investment in the protection and inheritance of folk culture, conduct scientific surveys of traditional folk culture, and formulate relevant policies for its preservation. A combination of spiritual incentives and material rewards should encourage young people interested in inheriting folk culture to learn the skills and pass down traditional culture. Residents should be encouraged to make traditional foods, clothing, and handicrafts, preserving and promoting folk culture. Valuable old houses should be functionally renovated, optimizing the village landscape and environment. Additionally, efforts should be made to deepen culture–tourism integration by incorporating cultural tourism projects highlighting local folk traditions, creating synergies between cultural heritage preservation and tourism development.

Combining traditional cultural resources with tourism development can promote cultural revitalization and innovative inheritance [35]. It is necessary to combine the existing resources of national parks and communities, strengthen policy guidance and overall planning, encourage cooperation and linkage between relevant cultural and tourism units and individuals, and promote the integration, optimization, integration, and complementarity of cultural and tourism resources. It is necessary to strengthen the promotion of cultural tourism and enhance tourists’ awareness and interest in culture and tourism through media publicity and internet promotion. It is necessary to increase investment in cultural and tourism facilities and build cultural scenic spots, cultural theme parks, cultural museums (such as Dongpo Study Hall), and other tourist destinations with distinctive features and strong appeal. It is necessary to combine local characteristics with innovative cultural tourism products. The Wuzh Mountain Lindong Cultural Industrial Park can be used as a reference for combining Li and Miao traditional techniques with ecological resources to create unique cultural tourism projects. It is necessary to further explore and preserve the Li and Miao cultures, attract tourists to experience the unique charm of folk culture, and achieve the interactive symbiosis of culture and tourism through such means as customizing cultural and creative products, organizing festive events (such as the 3 March Festival), displaying traditional handicrafts (such as Li brocade, Miao embroidery, and pottery making), and staging folk performances.

4. Discussion

Based on grounded theory, this study explores the contradictions between ecological protection and economic development in the communities of Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park. The study shows that residents face restrictions on resource use and industrial development, and enterprises encounter challenges in terms of infrastructure, markets, and policy control, leading to conflicts between ecological protection and economic development and hindering the implementation of ecological protection policies and local economic development. To this end, this paper proposes to balance ecological protection and community interests through various methods such as multi-party cooperation, resource integration, policy adjustment, and economic incentives.

The governance models of national parks worldwide are diversified due to differences in ecological characteristics and institutional backgrounds. For example, Brazil’s Yaw National Park has established an “ecological–cultural reserve” to give aboriginal communities the right to manage resources, deeply integrating ecological protection and cultural heritage [36]; Canada’s Banff National Park has adopted “zonal collaborative management”, dividing protection levels according to ecological sensitivity and balancing tourism development and ecological protection [37]. National Parks in New South Wales, Australia, has implemented the “public–private partnership (PPP) model” and introduced private capital to improve the management efficiency [38]; Yellowstone National Park in the United States and Keoladeo National Park in India have dynamically adjusted their strategies to cope with ecosystem changes through “adaptive management”. Yellowstone emphasizes a community participation approach to resource management, while Keoladeo Park conducts simultaneous long-term monitoring of ecological and social systems [39].

The strategy for coordinated community development in the Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park promotes multi-party coordination and cooperation by integrating the five dimensions of society, economy, ecology, institutions, and culture, which has the following advantages: (1) It fosters industrial diversification by developing eco-tourism, agro-tourism, and cultural experience industries, providing sustainable livelihood pathways for local communities. (2) It ensures a balance between economic benefits and ecological conservation through scientific management, safeguarding resources from degradation. (3) It enhances policy flexibility by allowing dynamic adjustments based on local needs, improving implementation effectiveness. (4) It facilitates multi-stakeholder cooperation, emphasizes community participation, mitigates resource-use conflicts, and fosters a governance model characterized by co-construction, co-management, and shared benefits. (5) It promotes the integration of culture and ecology, strengthens community cultural identity, and generates endogenous motivation for ecological conservation. This framework provides comprehensive guidance for the coordinated development of national park communities, advancing the sustainability of both ecological protection and economic development.

Despite the significant advantages of the coordinated development model of Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park, its governance still faces unique challenges, particularly in achieving a balance between ecological conservation, economic development, and community empowerment. A good governance structure should include multi-party cooperation, power sharing, and adjustments to management strategies based on the actual situation to ensure that ecological conservation and socio-economic goals are achieved synergistically—the synergistic realization of ecological conservation and socio-economic goals [40]. Effective governance relies on a precise distribution of power and requires a flexible response to different regions’ ecological and social needs to achieve sustainable conservation and development goals. Hainan needs to integrate international experience further, enhance the scientific and inclusive nature of community participation, and establish dynamic monitoring and feedback mechanisms to address complex local challenges.

Although the coordinated management framework proposed in this study provides theoretical support and practical guidance for the sustainable development of Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park, it still has certain limitations. First, the framework’s effectiveness in different contexts, especially in cross-regional applications, has not yet been fully verified, so more empirical studies are needed in the future. Second, balancing the multiple objectives of ecological protection, economic development, and social culture remains a significant challenge in practice. The framework’s operationalization and practical effects can be better assessed in the future by combining quantitative and qualitative research. Finally, although the framework emphasizes multi-party cooperation, in practice, how to effectively resolve conflicts among governments, enterprises, and residents, especially the issue of trust, remains an urgent difficulty. Future research could explore the feasibility and sustainability of the framework through third-party mediation with a transparent benefit-sharing mechanism. In addition, while this study does not specifically address biodiversity conservation, future research could consider incorporating the impact of tourism and production activities on biodiversity into the framework. This would further enhance ecological protection measures in national parks and provide additional perspectives for sustainable development in the future.

5. Conclusions

The core of coordinated community development in Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park lies in the deep integration of multi-actor coordinated participation and whole-process community-driven governance. This study constructs a new framework for coordinated community development in Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park based on grounded theory, providing a governance path from five dimensions. The main conclusions are as follows:

- (1)

- Revealing the limiting factors for sustainable development of the community: Through systematic analysis grounded in grounded theory, this study summarizes eight main categories that represent the community development challenges in Hainan Tropical Rainforest National Park (economic development motivation, industrial transformation support, talent education enhancement, community capacity building, ecological environmental protection, tourism resource management, policy system improvement, and cultural and tourism upgrade) and five core categories (economic, social, ecological, institutional, and cultural). The research shows that while ecological protection policies have significantly improved environmental quality, they have also triggered a series of issues in community economic and social development. These issues mainly manifest as income distribution disparity, single industrial structure, professional talent shortage, low community participation, excessive tourism facilities, protection–development clash, policy execution gap, interest coordination deficiency, weak cultural awareness, and shallow cultural integration, reflecting the complex and closely interconnected relationships between different categories. The interaction of these five dimensions further exacerbates the governance challenges, highlighting the importance and urgency of multi-party coordination mechanisms in achieving the dual goals of ecological protection and community development;

- (2)

- Multidimensional analysis to construct a coordinated community development: Through multidimensional analysis, this study constructs a new framework for coordinated community development in national parks based on five dimensions: economic, social, institutional, ecological, and cultural. In the economic dimension, improving the distribution mechanism and enhancing transformation guidance promote resident income growth and livelihood diversification. In the social dimension, strengthening education and training and building a co-management system improve community governance efficiency. In the ecological dimension, by strengthening tourism facility management, coordinating protection efforts, and strictly controlling the growth rate, the stability of the ecosystem is enhanced to achieve sustainable resource utilization. In the institutional dimension, clarifying franchise details and innovating the franchise model ensure rational and orderly policy execution. In the cultural dimension, promoting folk culture and deepening culture–tourism integration fosters the inheritance and innovation of traditional culture, driving the synergistic development of the cultural and tourism industries;

- (3)

- Clarifying the division of roles and the linkage mechanism among multiple stakeholders: Field research based on grounded theory reveals the central role of coordinated governance by all parties in local ecological protection. The research further clarifies the division of responsibilities among the national park, local government, local enterprises, community residents, academic groups, and social groups in the sustainable governance of the national park: the national park is the overall planner, the local government is the policy implementer, local enterprises are the development promoters, community residents are the direct participants, academic groups are the proponents of science, and social groups are the ecological advocates. Through the community co-management mechanism, all parties work together to promote the dual goals of ecological protection and community development, providing a practical path for the sustainable governance of the national park.

Author Contributions

Methodology, H.F.; data processing, software, and writing—original draft preparation, Y.G., G.F. and Q.Z.; supervision, L.Z. and T.X.; writing—review and funding acquisition, H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by Hainan Institute of National Park, Hainan Provincial Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project (HNSK(ZX)24-252); Hainan Provincial Higher Education Teaching Reform Research Fund (Hnjg2024-10); Hainan University Teaching Reform Research Project (hdjy2420); Hainan University Humanities and Social Sciences Young Scholar Support Project (24QNFC-14); and Natural Science Foundation of Hainan Province (722QN288).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang, J.; Yu, H.; Han, D.; Zhang, G.; Wei, Y.; An, L.; Liu, X.; Ren, Y. Declines in global ecological security under climate change. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 117, 106651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, R.G. (Ed.) National Parks and Protected Areas: Their Role in Environmental Protection; Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, U.R. An overview of park-people interactions in Royal Chitwan National Park, Nepal. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1990, 19, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C. National Parks and Rural Development: Practice and Policy in the United States; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sriarkarin, S.; Lee, C.H. Integrating multiple attributes for sustainable development in a national park. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 28, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, S.K.; Weber, K.W. Managing resources and resolving conflicts: National parks and local people. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 1995, 2, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortin, M.J.; Gagnon, C. An assessment of social impacts of national parks on communities in Quebec, Canada. Environ. Conserv. 1999, 26, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W.; Li, X. Study on the evolution, planning, management and enlightenment of National Park System of Japan. Northeast Asia Econ. Res. 2018, 2, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakakaawa, C.; Moll, R.; Vedeld, P.; Sjaastad, E.; Cavanagh, J. Collaborative resource management and rural livelihoods around protected areas: A case study of Mount Elgon National Park, Uganda. For. Policy Econ. 2015, 57, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariyawasam, S.; Wilson, C.; Rathnayaka, L.I.M.; Sooriyagoda, K.G.; Managi, S. Conservation versus socio-economic sustainability: A case study of the Udawalawe National Park, Sri Lanka. Environ. Dev. 2020, 35, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.P.; Kumar, J. Ecotourism for community development: A stakeholder’s perspective in Great Himalayan National Park. Int. J. Soc. Ecol. Sustain. Dev. IJSESD 2011, 2, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanglin, T.; Yan, Y.; Wenguo, L. Construction progress of national park system in China. Biodivers. Sci. 2019, 27, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J. Research on Community Participation Mechanism in the Management of Three-River-Source National Park; Beijing Forestry University: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L. Research on Community Planning of the Wuyishan National Park System Pilot Area; Tsinghua University: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Wu, C. A study on the management innovation of ecotourism region—A case study of Zhangjiajie National Forest Park. Issues For. Econ. 2006, 203–206+240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novellie, P.; Biggs, H.; Roux, D. National laws and policies can enable or confound adaptive governance: Examples from South African national parks. Environ. Sci. Policy 2016, 66, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Michaels, J.L.; Bell, S.E. Social capital’s influence on environmental concern in China: An analysis of the 2010 Chinese General Social Survey. Sociol. Perspect. 2019, 62, 844–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.G. National parks and protected areas, national conservation strategies and sustainable development. Geoforum 1987, 18, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Grounded theory. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 3, pp. 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- He, S.Y.; Wei, Y.; Su, Y.; Min, Q.W. A grounded theory approach to understanding the mechanism of community participation in national park establishment and management. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 3021–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, A. Using grounded theory to explore stakeholder perceptions of tourism. J. Tour. Cult. Change 2005, 3, 108–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, C.L. National park and reserve planning to protect biological diversity: Some basic elements. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1999, 44, 123–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handy, J.W. Community economic development: Some critical issues. Rev. Black Political Econ. 1993, 21, 41–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ma, Y. Study on Community Participation Mechanisms in Natural Heritage Conservation and Development. J. Jiangxi Univ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 35, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Wang, Y. Analysis on the disposition of collective land ownership in the construction of national park. Nat. Resour. Econ. China 2015, 28, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, X. The game theory analying between management of nature reserve and surrounding communities. Econ. Probl. 2007, 10, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nan, H.L.; Wang, X.P.; Chen, J.Q.; Zhu, J.G.; Yang, X.H.; Wen, Z.Y. Forest therapy in Japan and its revelation. World For. Res. 2013, 26, 74–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S. The role of communities in the governance of China’s national parks and the consolidation and development of their role. J. Nat. Resour. 2024, 39, 2310–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zuo, T.; Tang, L. Guidelines for Co-Management of Nature Reserves in China, 3rd ed.; China Agricultural Press: Beijing, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, F. Analysis on the relation of chess playing between the habitants in tourist community and the benefits related people—Taking the natural set performance of landscape of Guilin The Impression on Sister Liu as an example. Guangxi Ethn. Stud. 2007, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Yu, H. Theory, Methods, and Practices of Collaborative Development Planning for Protected Areas and Rural Communities, 3rd ed.; China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, S.; Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Xian, J. Balancing ecological conservation with socioeconomic development. Ambio 2021, 50, 1117–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W. The Study on the Concession Management Revolution of National Park Based on the Research on the American Example; East China Normal University: Shanghai, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bao, J.; Zuo, B. Institutional opportunistic behavior in tourism investment promotion—A Case from Western China. Hum. Geogr. 2008, 23, 1–6+91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z. Theory and practice of the integration of culture and tourism. Frontiers 2019, 11, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Lai, Q. Practice and experience of community participation in ecological compensation in other countries. For. Soc. 2005, 13, 40–44. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y. Research on the Division of National Parks in Canada from the Dual Perspectives of Conservation and Utilization; Southeast University: Nanjing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.; Nielsen, N.; Buultjens, J. From lessees to partners: Exploring tourism public–private partnerships within the New South Wales national parks and wildlife service. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, F. Research and insights on community-based adaptive and collaborative management pathways in nature reserves. J. Green Sci. Technol. 2020, 172–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, M. Good governance for terrestrial protected areas: A framework, principles and performance outcomes. J. Environ. Manag. 2010, 91, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).