Rural Migrant Workers in Urban China: Does Rural Land Still Matter?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Labor Migration and Land Tenure

2.2. Rural Household Model for Labor Allocation

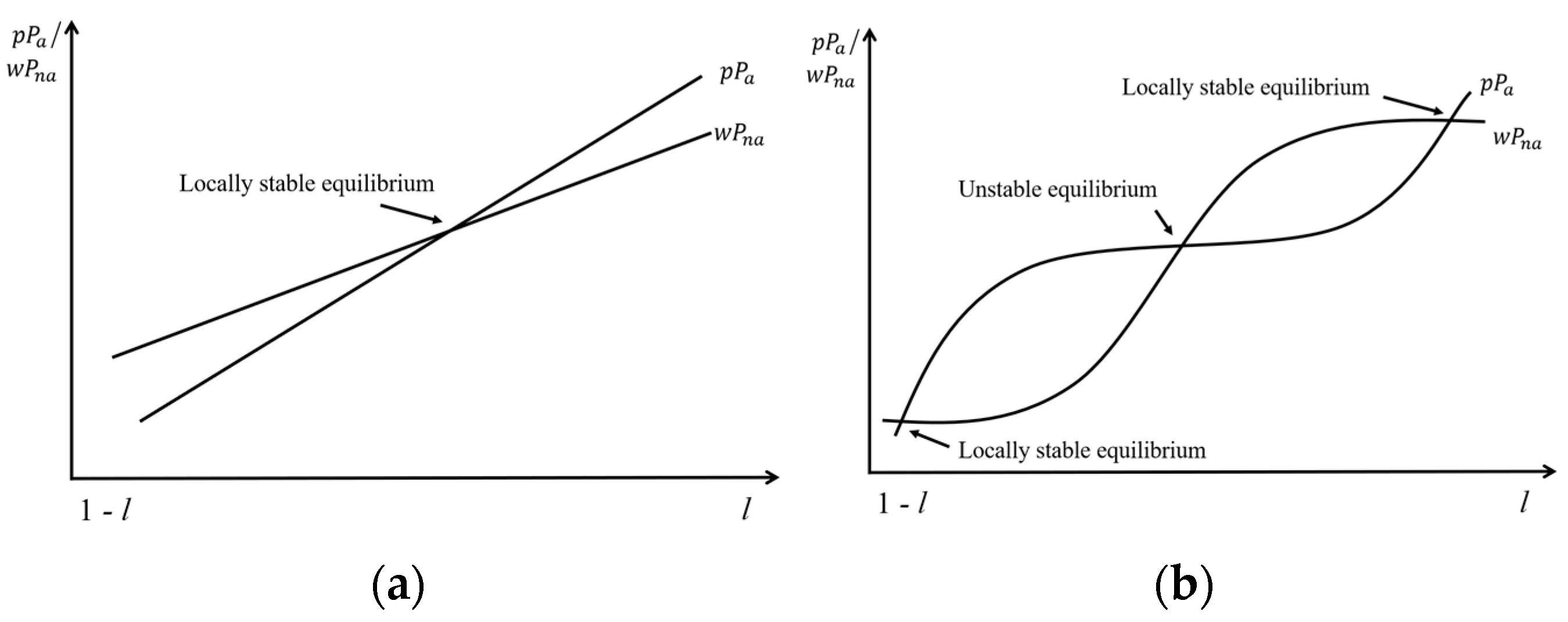

2.3. Locally Stable Equilibrium and Conditions

2.4. Land Endowment and Labor Supply: Heterogeneity in Land Tenure Security

3. Data

3.1. Questionnaire Survey

3.2. Variable Explanation and Descriptive Analysis

4. Methodology

4.1. Classification and Latent Class Model

4.2. Empirical Models and Identification

4.3. The Test for a U-Shaped Relationship

5. Results and Discussion

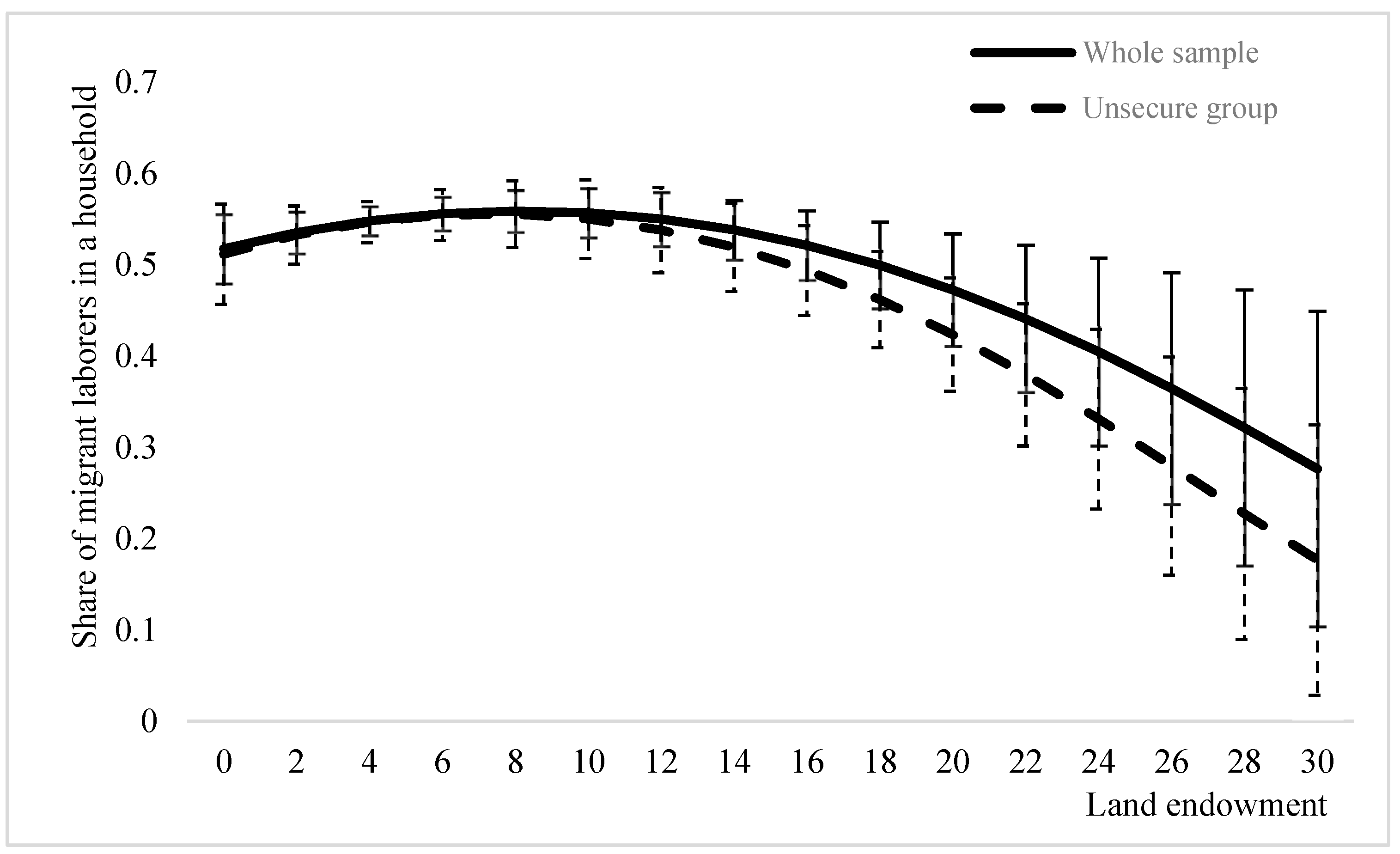

5.1. Household Labor Allocation

5.2. Individual Migration Decisions

5.3. The Land Rental Market

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| VARIABLES | HHINCOMEDIFF | SHARE |

|---|---|---|

| ACRE | −1.500 *** | 0.034 ** |

| (0.327) | (0.014) | |

| ACRESQ | −0.002 *** | |

| (0.001) | ||

| PARCEL | 0.607 | −0.011 |

| (0.619) | (0.008) | |

| HHEDU | 2.927 * | −0.046 * |

| (1.685) | (0.026) | |

| HHSIZENL | 0.218 | −0.315 *** |

| (1.930) | (0.021) | |

| HHINCOMEDIFF | 0.005 *** | |

| (0.002) | ||

| −0.001 | ||

| (0.002) | ||

| MONEYGIFT | 3.173 *** | |

| (0.445) | ||

| Constant | 38.704 *** | 0.110 |

| (5.189) | (0.123) | |

| Observations | 736 | 736 |

| R2/Pseudo R2 | 0.114 | 0.045 |

| VARIABLES | INCOMEDIFF | PLAN |

|---|---|---|

| ACREIND | −1.096 *** | 0.067 |

| (0.399) | (0.130) | |

| ACREINDSQ | −0.005 | |

| (0.014) | ||

| PARCEL | 0.016 | −0.035 |

| (0.264) | (0.030) | |

| LANDTENURE | 0.007 | 0.408 *** |

| (1.496) | (0.157) | |

| MALE | 6.360 *** | −0.567 ** |

| (1.976) | (0.259) | |

| AGE | −0.186 ** | −0.026 *** |

| (0.077) | (0.009) | |

| EDUC | 0.636 | 0.306 * |

| (1.194) | (0.174) | |

| INTEGRATION | 3.083 ** | 0.748 *** |

| (1.544) | (0.179) | |

| HHEDU | 0.854 | −0.274 |

| (1.205) | (0.171) | |

| HHSIZENL | 2.016 * | −0.088 |

| (1.098) | (0.104) | |

| INCOMEDIFF | 0.029 | |

| (0.020) | ||

| −0.024 | ||

| (0.020) | ||

| MONEYGIFT | 0.975 *** | |

| (0.281) | ||

| Constant | 28.230 *** | −0.282 |

| (5.544) | (0.795) | |

| Observations | 736 | 736 |

| R2/Pseudo R2 | 0.081 | 0.063 |

References

- SCRO (The State Council Research Office). Survey and Research Report on Chinese Migrant Workers; China Yanshi Press: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 2–4. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 2023 Monitoring and Investigation Report on Migrant Workers. (In Chinese). Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202404/t20240430_1948783.html (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Mullan, K.; Grosjean, P.; Kontoleon, A. Land tenure arrangements and rural-urban migration in China. World Dev. 2011, 39, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Feng, S. Access to public schools and the education of migrant children in China. China Econ. Rev. 2013, 26, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Michael, R.C.; Yao, Y. Dimensions and diversity of property rights in rural China: Dilemmas on the road to further reform. World Dev. 1998, 26, 1789–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Huang, J.; Rozelle, S. Employment, emerging labor markets, and the role of education in rural China. China Econ. Rev. 2002, 13, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Chen, K.; Yan, L.; Yu, L.; Zhu, Y. Citizenization of Rural Migrants in China’s New Urbanization: The Roles of Hukou System Reform and Rural Land Marketization. Cities 2023, 132, 103968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Janvry, A.; Sadoulet, E. Progress in the modeling of rural households’ behavior under market failures. In Poverty, Inequality and Development: Economic Studies in Inequality, Social Exclusion and Well-Being; De Janvry, A., Kanbur, R., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; Volume 1, pp. 155–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, J.K. Off-Farm Labor Markets and the Emergence of Land Rental Markets in Rural China. J. Comp. Econ. 2002, 30, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Fang, X.; Li, G.; Cao, Y. Does Land Tenure Fragmentation Aggravate Farmland Abandonment? Evidence from Big Survey Data in Rural China. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 91, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, R.; Xu, Z. Urbanization, rural land system and social security for migrants in China. J. Dev. Stud. 2007, 43, 1301–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanWey, L.K. Land ownership as a determinant of temporary migration in Nang Rong, Thailand. Eur. J. Popul. 2003, 19, 121–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckenzie, D.; Rapoport, H. Network effects and the dynamics of migration and inequality: Theory and evidence from Mexico. J. Dev. Econ. 2007, 84, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Heerink, N.; van Ierland, E.; Shi, X. Land tenure insecurity and rural-urban migration in rural China. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2016, 95, 383–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, P.; de Janvry, A.; Sadoulet, E. Family and community networks in Mexico-U.S. migration. J. Hum. Resour. 2001, 36, 159–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P. Relative deprivation and migration in an agricultural setting of Nepal. Popul. Environ. 2004, 25, 475–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Heerink, N. Are farm households’ land renting and migration decisions inter-related in rural China? NJAS-Wagen. J. Life Sci. 2008, 55, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lind, J.T.; Mehlum, H. With or without U? The appropriate test for a U-shaped relationship. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2010, 72, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, D.; Long, H.; Qiao, W.; Wang, Z.; Sun, D.; Yang, R. Effects of Rural–Urban Migration on Agricultural Transformation: A Case of Yucheng City, China. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 76, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, E. Entitled to work: Urban property rights and labor supply in Peru. Q. J. Econ. 2007, 122, 1561–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besley, T.; Ghatak, M. Property rights and economic development. In Handbook of Development Economics, 1st ed.; Rodrik, D., Rosenzweig, M., Eds.; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 5, Chapter 68; pp. 4525–4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, T.; Luo, B.; Choy, S.B.; Li, Y.; He, Q. Do Land Renting-in and Its Marketization Increase Labor Input in Agriculture? Evidence from Rural China. Land Use Policy 2020, 99, 104820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todaro, M.P. A model of labor migration and urban unemployment in less developed Countries. Am. Econ. Rev. 1969, 59, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Adamopoulos, T.; Brandt, L.; Leight, J.; Restuccia, D. Misallocation, selection and productivity: A quantitative analysis with panel data from China. Econometrica 2022, 90, 1261–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restuccia, D.; Rogerson, R. The causes and costs of misallocation. J. Econ. Perspect. 2017, 31, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Restuccia, D.; Santaeulalia-llopis, R. Land misallocation and productivity. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 2023, 15, 441–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restuccia, D. Misallocation and aggregate productivity across time and space. Can. J. Econ. 2019, 19, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.R.; Todaro, M.P. Migration, unemployment and development: A two-sector analysis. Am. Econ. Rev. 1970, 60, 126–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Brauw, A. Seasonal migration and agricultural production in Vietnam. J. Dev. Stud. 2010, 46, 114–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshri, K.; Bhagat, R.B. Temporary and seasonal migration in India. Genus 2010, 66, 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, L.; Zhao, M.Q. Permanent and temporary rural–urban migration in China: Evidence from field surveys. China Econ. Rev. 2018, 51, 228–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Cook, S.; Salazar, M.A. Internal migration and health in China. Lancet 2008, 372, 1717–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.Y. Rural factor markets in China: After the household responsibility system reform. In Chinese Economic Policy: Economic Reform at Midstream; Reynolds, B.L., Kim, I.J., Eds.; Paragon House: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 169–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bowlus, A.J.; Sicular, T. Moving toward markets? Labor allocation in rural China. J. Dev. Econ. 2003, 71, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Gong, J.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Y. Exploring the Effects of Rural Site Conditions and Household Livelihood Capitals on Agricultural Land Transfers in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 108, 105523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Tan, M. Land titling program and farmland rental market participation in China: Evidence from pilot provinces. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, A.C. Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics, 3rd ed.; McGraw-Hill, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 204–225. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical Bulletin on National Economic and Social Development of the People’s Republic of China in 2023. (In Chinese). Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202402/t20240228_1947915.html (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Giles, J.; Mu, R. Village political economy, land tenure insecurity, and the rural to urban migration decision: Evidence from China. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2018, 100, 521–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, J.K.S.; Bai, Y. Induced institutional change or transaction costs? The economic logic of land reallocations in Chinese agriculture. J. Dev. Stud. 2011, 47, 1510–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarsfeld, P.F.; Henry, N.W. Latent Structure Analysis; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan, G.; Peel, D.A. Finite Mixture Models; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa, R.; Thiene, M. Destination choice models for rock climbing in the Northeastern Alps: A latent-class approach based on intensity of preferences. Land Econ. 2005, 81, 426–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonsky, E.D.; Olino, T.M. Identifying clinically distinct subgroups of self-injurers among young adults: A latent class analysis. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2008, 76, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, A.P.; Islam, M.M.; Toma, L. Heterogeneity in climate change risk perception amongst dairy farmers: A latent class clustering analysis. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 41, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipnis, A.B. Producing Guanxi: Sentiment, Self, and Subculture in a North China Village; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Hudik, M.; Fang, E.S. Money or in-kind gift? Evidence from red packets in China. J. Institutional Econ. 2020, 16, 731–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasabuchi, S. A test of a multivariate normal mean with composite hypotheses determined by linear inequalities. Biometrika 1980, 67, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieller, E.C. Some problems in interval estimation. J. R. Stat. Soc. 1954, 16, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyourko, J.; Shen, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhang, R. Land Finance in China: Analysis and Review. China Econ. Rev. 2022, 76, 101868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Duan, J.; Yang, L. Spatio-Temporal Pattern and Driving Mechanisms of Cropland Circulation in China. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 105118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, J.K. Common Property Rights and Land Reallocations in Rural China: Evidence from a Village Survey. World Dev. 2000, 28, 701–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H. Effects of Farmland Use Rights Transfer on Collective Action in the Commons: Evidence from Rural China. Land Use Policy 2022, 120, 106262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Feng, S.; Lu, H.; Qu, F.; D’Haese, M. How Do Non-Farm Employment and Agricultural Mechanization Impact on Large-Scale Farming? A Spatial Panel Data Analysis from Jiangsu Province, China. Land Use Policy 2021, 107, 105517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Definition | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Migration variables | |||||

| Share | Share of migrants in household | 0.55 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 1 |

| Plan | 1 = stay in cities; 0 = return to villages | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0 | 1 |

| Land endowment | |||||

| Acre | Land endowment in mu | 5.39 | 3.99 | 0.6 | 23 |

| Acreind | Land endowment per household laborer | 1.96 | 1.67 | 0.23 | 10 |

| Parcel | Land parcel number | 3.94 | 2.81 | 1 | 15 |

| Land tenure variables | |||||

| Landcont | 1 = land contract with collective | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 |

| Landadjustatt | Attitude towards land adjustment a | 2.29 | 1.32 | 1 | 5 |

| Landprivate | Land ownership assessment b | 2.09 | 1.40 | 1 | 4 |

| Landrent | 1 = land rental market | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 |

| Control variables | |||||

| Individual-level | |||||

| Male | 1 = male | 0.82 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 |

| Educ | Respondent education level c | 2.72 | 0.85 | 1 | 5 |

| Age | Age in years | 42.66 | 9.86 | 16 | 72 |

| Incomediff | Annual income difference between city and farming job(s), in 1000 CNY | 34.97 | 20.74 | 7.2 | 138 |

| Integration | 1 = integrated into cities | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0 | 1 |

| Household-level | |||||

| Hhedu | Household-head education c | 2.67 | 0.83 | 1 | 5 |

| Hhsizenl | Number of non-working household members | 3.04 | 0.95 | 1 | 6 |

| Hhincomediff | Household annual income difference between city and farming job(s), in 1000 CNY | 54.15 | 40.36 | −15 | 237.6 |

| Instrumental variable | |||||

| Moneygift | Monetary gift-giving in 1000 CNY | 4.15 | 3.82 | 0 | 36 |

| Model | Number of Clusters | Npar | BIC (LL) | L2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 1 Cluster | 9 | 4950.61 | 132.44 | 9.6× 10−6 |

| Model 2 | 2 Clusters | 14 | 4935.45 | 84.28 | 0.054 |

| Model 3 | 3 Clusters | 19 | 4948.17 | 63.99 | 0.34 |

| Model 4 | 4 Clusters | 24 | 4971.27 | 54.08 | 0.51 |

| Variables | Cluster 1—No of Obs. | Cluster 2—No of Obs. | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landadjustatt | 416 | 320 | 3.27 (0.90) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.00 |

| Landprivate | 416 | 320 | 2.09 (1.40) | 2.08 (1.41) | 0.94 |

| Landcont | 416 | 320 | 0.67 (0.47) | 0.62 (0.49) | 0.21 |

| Landrent | 416 | 320 | 0.26 (0.44) | 0.08 (0.26) | 0.00 |

| Landadjust | 416 | 320 | 0.69 (0.46) | 0.72 (0.45) | 0.46 |

| Landlaw | 416 | 320 | 0.15 (0.36) | 0.09 (0.29) | 0.02 |

| Variables | Secured Group | Unsecured Group | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Migration variables | |||

| Share | 0.55 (0.24) | 0.54 (0.24) | 0.65 |

| Plan | 0.51 (0.50) | 0.41 (0.49) | 0.01 ** |

| Control variables | |||

| Individual-level | |||

| Acreind | 2.04 (1.73) | 1.84 (1.59) | 0.11 |

| Parcel | 4.02 (2.91) | 3.83 (2.69) | 0.37 |

| Male | 0.83 (0.38) | 0.82 (0.39) | 0.69 |

| Educ | 2.77 (0.86) | 2.66 (0.85) | 0.09 |

| Age | 42.31 (10.09) | 43.11 (9.53) | 0.28 |

| Incomediff | 34.74 (21.19) | 35.27 (20.18) | 0.73 |

| Integration | 0.67 (0.47) | 0.68 (0.47) | 0.66 |

| Household-level | |||

| Acre | 5.53 (4.04) | 5.21 (3.92) | 0.28 |

| Hhedu | 2.68 (0.83) | 2.66 (0.82) | 0.83 |

| Hhsizenl | 3.01 (0.98) | 3.08 (0.90) | 0.37 |

| Hhincomediff | 53.25 (40.81) | 55.32 (39.81) | 0.49 |

| Variable | Full Sample | Secure Group | Unsecure Group | Full Sample | Secure Group | Unsecure Group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acre | 0.014 | 0.026 | −0.005 | 0.033 ** | 0.030 | 0.038 * |

| (0.015) | (0.020) | (0.023) | (0.014) | (0.019) | (0.021) | |

| Acresq | −0.001 * | −0.002 | −0.001 | −0.002 *** | −0.001 | −0.002 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Parcel | - | - | - | −0.011 | −0.009 | −0.009 |

| (0.007) | (0.010) | (0.011) | ||||

| Hhedu | - | - | - | −0.043 * | −0.024 | −0.065 * |

| (0.025) | (0.033) | (0.038) | ||||

| Hhsizenl | - | - | - | −0.314 *** | −0.309 *** | −0.313 *** |

| (0.021) | (0.029) | (0.032) | ||||

| Hhincomediff | - | - | - | 0.004 *** | 0.004 *** | 0.006 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||||

| Constant | 0.090 | 0.054 | 0.151 * | 0.148 | 0.141 | 0.114 |

| (0.055) | (0.073) | (0.084) | (0.092) | (0.126) | (0.134) | |

| Observations | 736 | 416 | 320 | 736 | 416 | 320 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.045 | 0.038 | 0.056 |

| Item | Overall | Secure Tenure | Unsecure Tenure |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACRE | 0.033 ** (0.014) | 0.030 (0.019) | 0.038 * (0.021) |

| ACRESQ | −0.002 *** (0.001) | −0.001 (0.001) | −0.002 *** (0.001) |

| Slope at lower bound | 0.025 ** | 0.024 * | 0.030 * |

| Slope at upper bound | −0.048 *** | −0.035 * | −0.069 *** |

| Appropriate for an inverse U shape (t-value) | 1.91 ** | 1.35 * | 1.53 * |

| Extremum point (mu) | 8.191 | 9.695 | 7.332 |

| 90% confidence interval, Fieller method | [3.332, 10.547] | [-, -] | [-, -] |

| Variables | PLAN | PLAN |

|---|---|---|

| Acreind | 0.016 | 0.041 |

| (0.118) | (0.128) | |

| Acreindsq | −0.006 | −0.005 |

| (0.014) | (0.014) | |

| Parcel | - | −0.034 |

| - | (0.030) | |

| Landtenure | - | 0.394 ** |

| (0.156) | ||

| Incomediff | - | 0.005 |

| (0.004) | ||

| Male | - | −0.408 * |

| (0.223) | ||

| Age | −0.030 *** | |

| (0.009) | ||

| Educ | - | 0.323 * |

| (0.174) | ||

| Integration | - | 0.823 *** |

| (0.170) | ||

| Hhedu | −0.246 | |

| (0.170) | ||

| Hhsizenl | −0.034 | |

| (0.094) | ||

| Constant | −0.121 | 0.400 |

| (0.167) | (0.575) | |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.001 | 0.062 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Florkowski, W.J.; Liu, Z. Rural Migrant Workers in Urban China: Does Rural Land Still Matter? Land 2025, 14, 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040901

Chen H, Florkowski WJ, Liu Z. Rural Migrant Workers in Urban China: Does Rural Land Still Matter? Land. 2025; 14(4):901. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040901

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Huiguang, Wojciech J. Florkowski, and Zhongyuan Liu. 2025. "Rural Migrant Workers in Urban China: Does Rural Land Still Matter?" Land 14, no. 4: 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040901

APA StyleChen, H., Florkowski, W. J., & Liu, Z. (2025). Rural Migrant Workers in Urban China: Does Rural Land Still Matter? Land, 14(4), 901. https://doi.org/10.3390/land14040901