A Differentiated Spatial Assessment of Urban Ecosystem Services Based on Land Use Data in Halle, Germany

Abstract

:1. Introduction

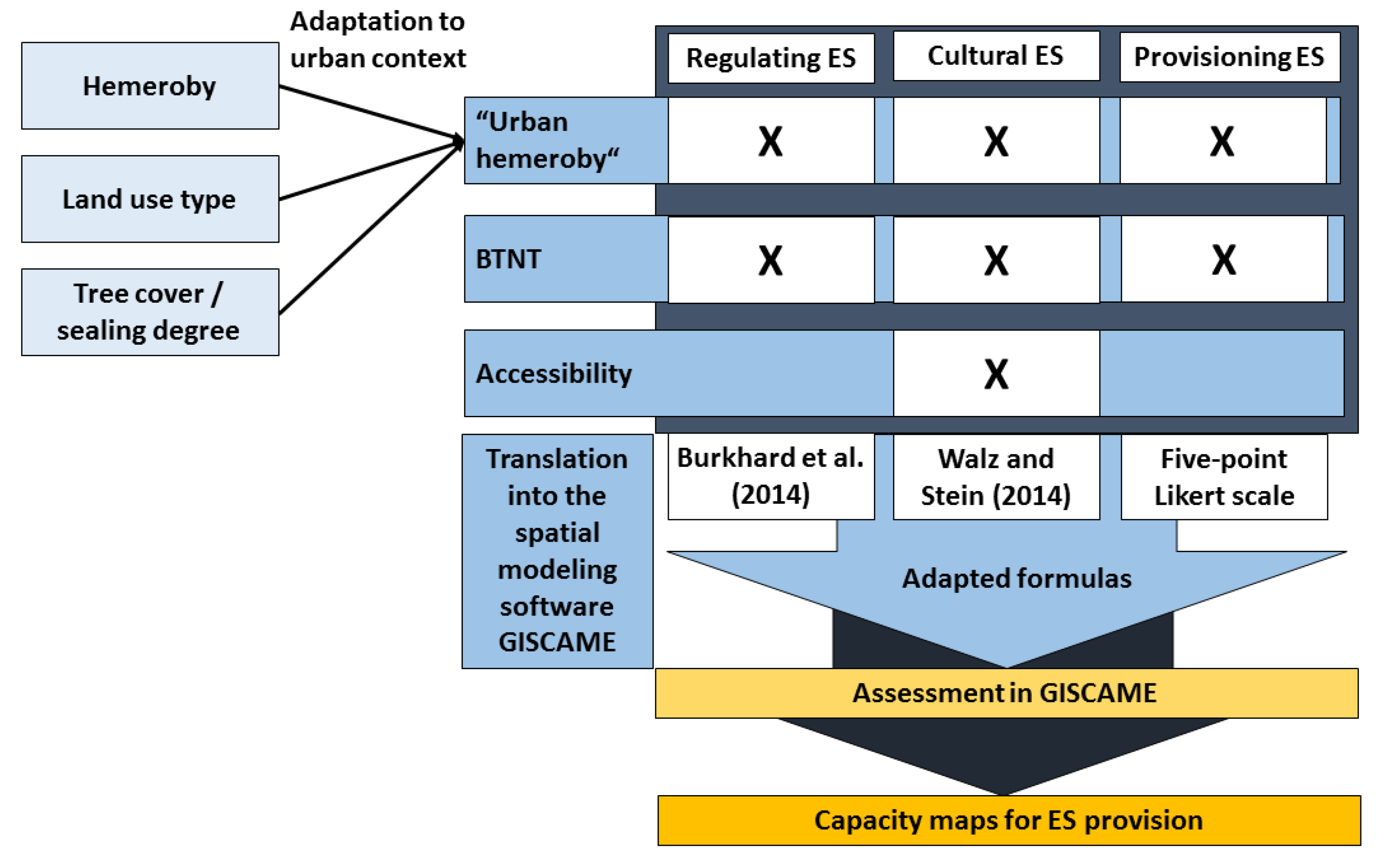

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Spatial Assessment Tools

2.3. Data Base and Re-Classification—Combination of the Regional Biotope and Land Use Data Set, Hemeroby and Accessibility

- First digit: the hemeroby of the area (Section 2.3.1)

- Second digit: the biotope or land use type of the area (Section 2.3.2)

- Third digit: the accessibility of urban nature to the public (Section 2.3.3).

2.3.1. Classification of Land Use Classes into Hemeroby Degrees (1st Digit)

2.3.2. Land Use/Land Cover Data Sets—Biotope and Land Use Mapping Data (2nd Digit)

- (7a)

- Built-up area 1: green and open areas of the built-up area

- (7b)

- Built-up area 2: residential and mixed-use areas

- (7c)

- Built-up area 3: industrial and commercial areas

- (7d)

- Built-up area 4: allotment gardens

- (7e)

- Built-up area 5: traffic areas

- (7f)

- Built-up area 6: sports and leisure facilities/camping

- (7g)

- Remaining built-up areas (not further classified)

2.3.3. Division into Private or Public Accessible Urban Area (3rd Digit)

2.4. Selection of Urban Ecosystem Services

2.5. Assessment Approach of Urban Ecosystem Services

2.5.1. Regulating Ecosystem Services

- Examples:

- HI of hemeroby degree 4 = 70

- BM for green urban areas = 2

- BM for residential and mixed-used areas = 0

- Green urban area: 70 − ((5 − 2):10) × 70 = 49

- Residential and mixed-used area: 70 − ((5 − 0):10) × 70 = 35

2.5.2. Cultural Services

- Examples:

- HI of hemeroby 4 = 70

- DH for green urban areas = 1

- DH for residential and mixed-used areas = 4

- Green urban area: 70 − (1:10) × 70 = 63

- Residential and mixed-used area: 70 − (4:10) × 70 = 38

2.5.3. Food Supply

3. Results

3.1. Spatial Statistics—Areas Allocated to BTNT, Hemeroby and Accessibility

3.2. Results of the Ecosystem Service Assessment

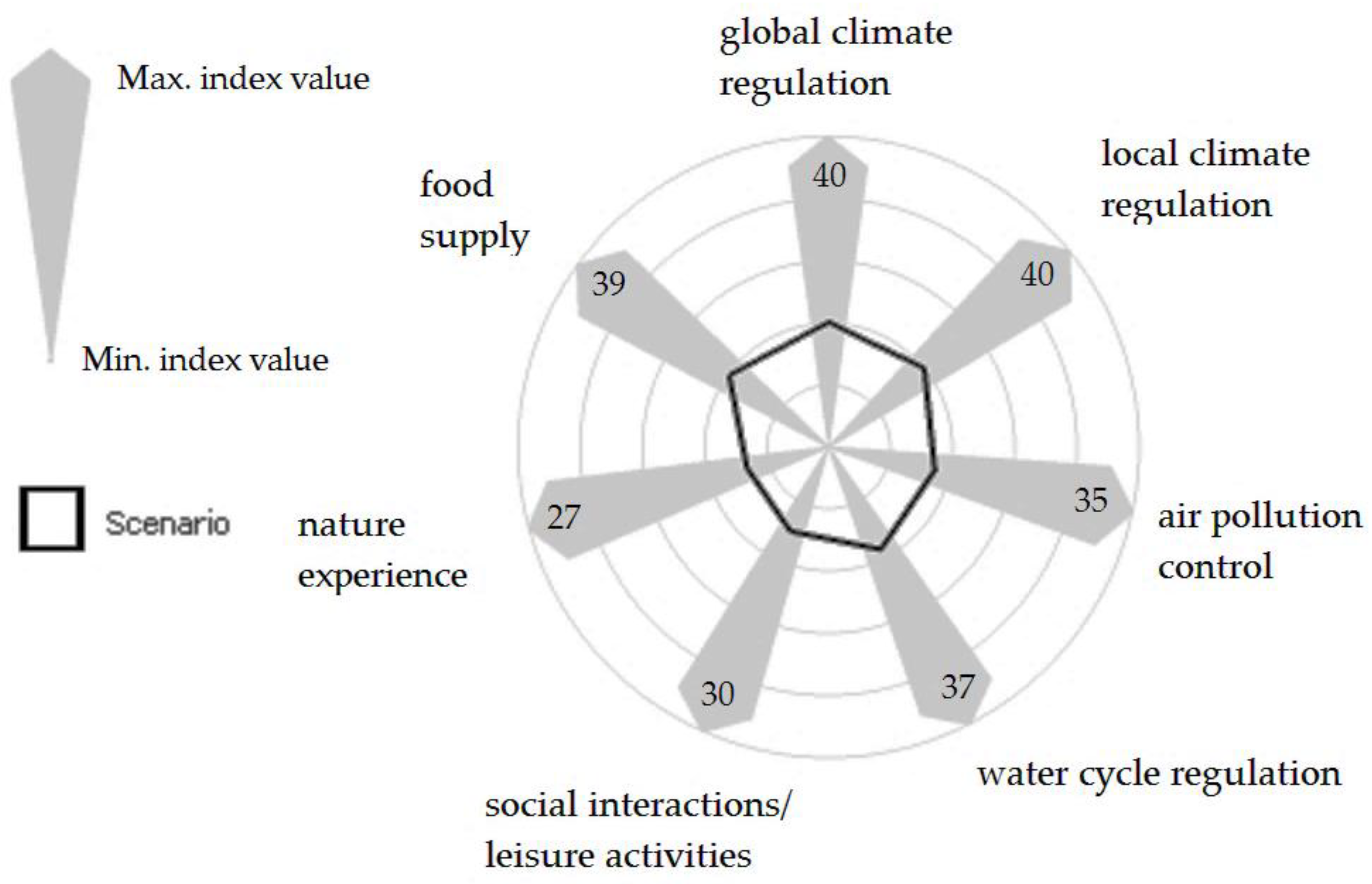

3.2.1. Index Values of Ecosystem Services

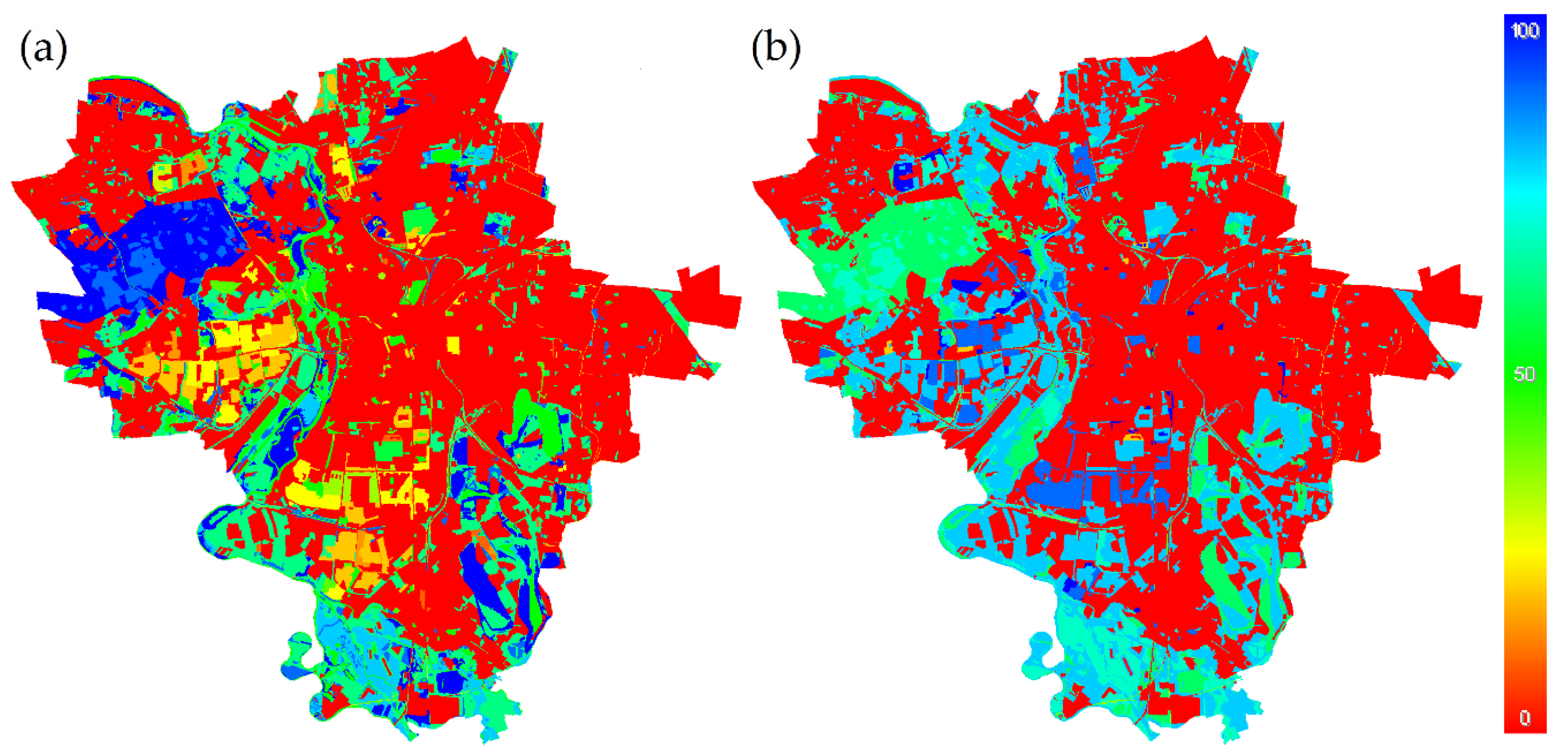

3.2.2. Capacity Maps for Regulating Ecosystem Services

3.2.3. Capacity Maps for the Cultural Ecosystem Services

3.2.4. Capacity Map for the Provisioning Ecosystem Service “Food Supply”

4. Discussion

4.1. Ecosystem Services Capacity in Halle

4.2. Assessment Approach and Database

4.3. Impact for Urban Planning and Decision Making

5. Conclusions

- The assessment approach contributes to the localization and a refined estimation of urban ES provision levels.

- The consideration of hemeroby represents a more differentiated ES assessment adapted to the context of urban areas.

- A sub-classification of ES (in our case, the cultural ES “recreation”) should be taken into account since they might also differ in ES provision.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Examples of Building Types and Accessibility of Green Space

Appendix B. Detailed Description of Selected Ecosystem Services

Appendix B.1. Global Climate Regulation

Appendix B.2. Local Climate Regulation

Appendix B.3. Air Pollution Control

Appendix B.4. Water Cycle Regulation

Appendix B.5. Nature Experience and Social Interactions/Leisure Activities

- Aesthetic nature experience: sensual experience of beauty and uniqueness of nature

- Exploring nature experience: examining animals and plants

- Instrumental nature experience: maintaining and use of animals and plants

- Social nature experience: building a relationship with animals, plants and natural places

Appendix B.6. Food Supply

References

- Birch, E.; Wachter, S. World urbanization: The critical issue of the twenty-first century. In Global Urbanization; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Urbanisation Prospects: The 2018 Revision. Key Facts. Economic and Social Affairs; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Barton, D.N. Classifying and valuing ecosystem services for urban planning. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 86, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, R.S.; Wilson, M.A.; Boumans, R.M.J. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecol. Econ. 2002, 41, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daily, G.C.; Polasky, S.; Goldstein, J.; Kareiva, P.M.; Mooney, H.A.; Pejchar, L.; Ricketts, T.H.; Salzman, J.; Shallenberger, R. Ecosystem services in decision making: Time to deliver. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2009, 7, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M. The links between biodiversity, ecosystem services and human well-being. In Ecosystem Ecology: A New Synthesis; Raffaelli, D., Frid, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 110–139. [Google Scholar]

- TEEB. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity: Mainstreaming the Economics of Nature: A Synthesis of the Approach, Conclusions and Recommendations of TEEB; TEEB: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz, S.; Demissew, S.; Carabias, J.; Joly, C.; Lonsdale, M.; Ash, N.; Larigauderie, A.; Adhikari, J.R.; Arico, S.; Báldi, A.; et al. The IPBES Conceptual Framework—Connecting nature and people. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M. Proposal for a Common International Classification of Ecosystem Goods and Services (CICES) for Integrated Environmental and Economic Accounting; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010; Volume 30. [Google Scholar]

- Stadtökosysteme. Funktion, Management und Entwicklung, 1st ed.; Breuste, J., Pauleit, S., Haase, D., Sauerwein, M., Eds.; Springer Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, M. Measurement of road traffic noise reduced by the employment of low physical barriers and potted vegetation. Inter-Noise Noise-Con Congr. Conf. Proc. 1994, 29–31, 595–598. [Google Scholar]

- Nowak, D.J.; Hirabayashi, S.; Bodine, A.; Greenfield, E. Tree and forest effects on air quality and human health in the United States. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 193, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Andersson, E.; Barthel, S.; Borgström, S.; Colding, J.; Elmqvist, T.; Folke, C.; Gren, Å. Reconnecting cities to the biosphere: Stewardship of green infrastructure and urban ecosystem services. Ambio 2014, 43, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hope, D.; Gries, C.; Zhu, W.; Fagan, W.F.; Redman, C.L.; Grimm, N.B.; Nelson, A.; Martin, C.; Kinzig, A. Socio-economics drive urban plant diversity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 8788–8792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graves, R.A.; Pearson, S.M.; Turner, M.G. Landscape dynamics of floral resources affect the supply of a biodiversity-dependent cultural ecosystem service. Landsc. Ecol. 2017, 32, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aronson, M.F.J.; Lepczyk, C.A.; Evans, K.L.; Goddard, M.A.; Lerman, S.B.; MacIvor, J.S.; Nilon, C.H.; Vargo, T. Biodiversity in the city: Key challenges for urban green space management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 15, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziter, C. The biodiversity-ecosystem service relationship in urban areas: A quantitative review. Oikos 2016, 125, 761–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastian, O.; Haase, D.; Grunewald, K. Ecosystem properties, potentials and services—The EPPS conceptual framework and an urban application example. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 21, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban green space, public health, and environmental justice: The challenge of making cities ‘just green enough’. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jalas, J. Hemerobe and hemerochore Pflanzenarten: Ein terminologischer Reformversuch. Acta Soc. Pro Fauna Flora Fenn. 1955, 72, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sukopp, H. Wandel von Flora und Vegetation in Mitteleuropa unter dem Einfluß des Menschen. Berichte Landwirtsch. 1972, 50, 112–139. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, U.; Lehmann, I.; Behnisch, M. Modellansatz zur geotopographischen Analyse von Wohngebieten und urbaner grüner Infrastruktur. AGIT J. Angew. Geoinform. 2016, 2, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beichler, S.A.; Bastian, O.; Haase, D.; Heiland, S.; Kabisch, N.; Müller, F. Does the Ecosystem Service Concept Reach its Limits in Urban Environments? Landsc. Online 2017, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauleit, S.; Duhme, F. Assessing the environmental performance of land cover types for urban planning. Landsc. Urban Plann. 2000, 52, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadt Halle (Saale). ISEK Halle Saale 2025; Stadt Halle: Halle, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, A.; Röhl, D.; Haase, D.; Schwarz, N. Leipzig-Halle: Ecosystem Services in a Stagnating Urban Region in Eastern Germany. In Peri-Urban Futures: Scenarios and Models for Land Use Change in Europe; Nilsson, K., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 209–239. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesamt für Kartographie und Geodäsie. ©GeoBasis-DE/BKG; BKG: Frankfurt, Germany, 2018.

- Fürst, C.; Volk, M.; Pietzsch, K.; Makeschin, F. Pimp your landscape: A tool for qualitative evaluation of the effects of regional planning measures on ecosystem services. Environ. Manag. 2010, 46, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koschke, L.; Fürst, C.; Frank, S.; Makeschin, F. A multi-criteria approach for an integrated land-cover-based assessment of ecosystem services provision to support landscape planning. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 21, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giscame. 2018. Available online: https://www.giscame.com/giscame/english_home.html (accessed on 6 July 2018).

- Burkhard, B.; Kandziora, M.; Hou, Y.; Müller, F. Ecosystem Service Potentials, Flows and Demands-Concepts for Spatial Localisation, Indication and Quantification. Landsc. Online 2014, 34, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walz, U.; Stein, C. Indicators of hemeroby for the monitoring of landscapes in Germany. J. Nat. Conserv. 2014, 22, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, H.-P.; Sukopp, H. Ökologische Bedeutung anthropogener Bodenveränderungen. Schriftenreihe Vegetationskunde 1976, 10, 75–89. [Google Scholar]

- Schlüter, H. Natürlichkeitsgrad der Vegetation. In Analyse und Ökologische Bewertung der Landschaft, 2nd ed.; Bastian, O., Schreiber, K.-F., Eds.; Spektrum Akademischer Verlag: Heidelberg/Berlin, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Landesamt für Umweltschutz Sachsen-Anhalt. Katalog der Biotoptypen und Nutzungstypen für die CIR-luftbildgestützte Biotoptypenkartierung im Land Sachsen-Anhalt. In Berichte des Landesamtes für Umweltschutz Sachsen-Anhalt; Landesamtes für Umweltschutz Sachsen-Anhalt: Halle (Saale), Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald, K.; Richter, B.; Meinel, G.; Herold, H.; Syrbe, R.-U. Proposal of indicators regarding the provision and accessibility of green spaces for assessing the ecosystem service “recreation in the city” in Germany. Int. J. Biodivers. Sci. Ecosyst. Serv. Manag. 2017, 13, 26–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D. Was leisten Stadtökosysteme für die Menschen in der Stadt? In Stadtökosysteme: Funktion, Management und Entwicklung, 1st ed.; Breuste, J., Pauleit, S., Haase, D., Sauerwein, M., Eds.; Springer Spektrum: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 129–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium für Umwelt. Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit. In Grün in der Stadt—Für Eine Lebenswerte; Zukunft: Berlin, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, A.; Eichhorn, S. Öffentliche und Private Räume—Gebaute und Gelebte Räume; Jahrbuch der Stadterneuerung: Berlin, Germany, 2004; pp. 359–376. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, S.; Keil, A.; Keil, P.; Reidl, K.; Rink, D.; Schemel, H.J. Naturerleben, Naturerfahrung und Umweltbildung in der Stadt. In Naturkapital Deutschland TEEB (2016): Ökosystemleistungen in der Stadt. Gesundheit Schützen und Lebensqualität Erhöhen; TU Berlin, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung UFZ Berlin: Leipzig, Germany, 2016; pp. 146–169. [Google Scholar]

- Skelhorn, C.; Lindley, S.; Levermore, G. The impact of vegetation types on air and surface temperatures in a temperate city: A fine scale assessment in Manchester, UK. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 121, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohbach, M.W.; Haase, D. Above-ground carbon storage by urban trees in Leipzig, Germany: Analysis of patterns in a European city. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2012, 104, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataki, D.E.; Alig, R.J.; Fung, A.S.; Golubiewski, N.E.; Kennedy, C.A.; McPherson, E.G.; Nowak, D.J.; Pouyat, R.V.; Romero Lankao, P. Urban ecosystems and the North American carbon cycle. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2006, 12, 2092–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Wang, Y.; Chang, Q.; Fu, M.; Ye, M. Assessment of landscape patterns affecting land surface temperature in different biophysical gradients in Shenzhen, China. Urban Ecosyst. 2013, 16, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.E.; Handley, J.F.; Ennos, A.R.; Pauleit, S. Adapting Cities for Climate Change: The Role of the Green Infrastructure. Built Environ. 2007, 33, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Säumel, I.; Draheim, T.; Endlicher, W.; Langner, M. Stadtnatur fördert saubere Luft. In Naturkapital Deutschland TEEB (2016): Ökosystemleistungen in der Stadt. Gesundheit Schützen und Lebensqualität Erhöhen; TU Berlin, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung UFZ Berlin: Leipzig, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Armson, D.; Stringer, P.; Ennos, A.R. The effect of street trees and amenity grass on urban surface water runoff in Manchester, UK. Urban For. Urban Green. 2013, 12, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maller, C.; Townsend, M.; Pryor, A.; Brown, P.; St Leger, L. Healthy nature healthy people: ‘contact with nature’ as an upstream health promotion intervention for populations. Health Promot. Int. 2006, 21, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellert, S.R. Experiencing nature: Affective, cognitive, and evaluative development in children. In Children and Nature: Psychological, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary Investigations; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Derkzen, M.; van Teeffelen, A.J.A.; Verburg, P.H.; Diamond, S. Quantifying urban ecosystem services based on high-resolution data of urban green space: An assessment for Rotterdam, The Netherlands. J. Appl. Ecol. 2015, 52, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, R.; Pölling, B. Urbane Landwirtschaft in der Metropole Ruhr. B&B Agrar 2014, 2, 9–12. [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi, G.; Eyzaguirre, P.; Negri, V. Home gardens: Neglected hotspots of agro-biodiversity and cultural diversity. Biodivers. Conserv. 2010, 19, 3635–3654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunewald, K.; Bastian, O. Ökosystemdienstleistungen. Konzept, Methoden und Fallbeispiele; Springer Spektrum: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Breuste, J.H. Decision making, planning and design for the conservation of indigenous vegetation within urban development. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 439–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haase, D.; Schwarz, N.; Strohbach, M.; Kroll, F.; Seppelt, R. Synergies, trade-offs, and losses of ecosystem services in urban regions: An integrated multiscale framework applied to the Leipzig-Halle Region, Germany. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, C.; Walz, U. Hemerobie als Indikator für das Flächenmonitoring. Methodenentwicklung Beispiel von Sachsen/Hemeroby as Indicator for the Monitoring of Land Use—Development of methods using the example of Saxony. Naturschutz Landschaftsplanung 2012, 44, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- García-Llorente, M.; Martín-López, B.; Iniesta-Arandia, I.; López-Santiago, C.A.; Aguilera, P.A.; Montes, C. The role of multi-functionality in social preferences toward semi-arid rural landscapes: An ecosystem service approach. Environ. Sci. Policy 2012, 19–20, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadt Halle (Saale). Erlass Einer Satzung zum Schutze des Stadtwaldes “Dölauer Heide”. 1954. Available online: http://www.halle.de/Publications/4520/sr925.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2018).

- Stadt Halle (Saale). Verordnung zur Festsetzung des Naturschutzgebietes “Forstwerder”. 1998. Available online: http://www.halle.de/Publications/3264/nsg_forstwerder.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2018).

- Breuste, J.H.; Artmann, M. Allotment Gardens Contribute to Urban Ecosystem Service: Case Study Salzburg, Austria. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2015, 141, A5014005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadt Halle (Saale). Kleingartenkonzeption Halle (Saale); Stadt Halle: Halle, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kroll, F.; Müller, F.; Haase, D.; Fohrer, N. Rural–urban gradient analysis of ecosystem services supply and demand dynamics. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupp, G.; Förster, B.; Kantelberg, V.; Markmann, T.; Naumann, J.; Honert, C.; Koch, M.; Pauleit, S. Assessing the Recreation Value of Urban Woodland Using the Ecosystem Service Approach in Two Forests in the Munich Metropolitan Region. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baró, F.; Palomo, I.; Zulian, G.; Vizcaino, P.; Haase, D.; Gómez-Baggethun, E. Mapping ecosystem service capacity, flow and demand for landscape and urban planning: A case study in the Barcelona metropolitan region. Land Use Policy 2016, 57, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, A.K.; Bloch, R.; Lamond, J. Cities and Flooding: A Guide to Integrated Urban Flood Risk Management for the 21st Century; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Fritzsche, B.; Fuchs, M.; Orth, A.K. Strukturbericht Sachsen-Anhalt; ECONSTOR: IAB-Regional, IAB Sachsen-Anhalt-Thüringen, No. 03/2016; Institut für Arbeitsmarkt- und Berufsforschung (IAB): Nürnberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Santamouris, M. Cooling the cities—A review of reflective and green roof mitigation technologies to fight heat island and improve comfort in urban environments. Sol. Energy 2014, 103, 682–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, M. Green facades—A view back and some visions. Urban Ecosyst. 2008, 11, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.; Fürst, C.; Koschke, L.; Witt, A.; Makeschin, F. Assessment of landscape aesthetics—Validation of a landscape metrics-based assessment by visual estimation of the scenic beauty. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 32, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stadt Halle (Saale). Wohnungspolitisches Konzept 2018; Stadt Halle: Halle, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerholm, N.; Käyhkö, N.; Ndumbaro, F.; Khamis, M. Community stakeholders’ knowledge in landscape assessments—Mapping indicators for landscape services. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 18, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N. Ecosystem service implementation and governance challenges in urban green space planning—The case of Berlin, Germany. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J.; Cilliers, S.; Niemelä, J. The concept of ecosystem services in adaptive urban planning and design: A framework for supporting innovation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 254–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, L.; Chu, E.; Anguelovski, I.; Aylett, A.; Debats, J.; Goh, K.; Schenk, T.; Seto, K.C.; Dodman, D.; Roberts, D.; et al. Roadmap towards justice in urban climate adaptation research. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2016, 6, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Früh-Müller, A.; Hotes, S.; Breuer, L.; Wolters, V.; Koellner, T. Regional Patterns of Ecosystem Services in Cultural Landscapes. Land 2016, 5, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, S.; Fürst, C.; Witt, A.; Koschke, L.; Makeschin, F. Making use of the ecosystem services concept in regional planning—trade-offs from reducing water erosion. Landsc. Ecol. 2014, 29, 1377–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandziora, M.; Dörnhöfer, K.; Oppelt, N.; Müller, F. Detecting Land Use And Land Cover Changes in Northern German Agricultural Landscapes to Assess Ecosystem Service Dynamics. Landsc. Online 2014, 35, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revi, A.; Satterthwaite, D.; Aragón-Durand, F.; Corfee-Morlot, J.; Kiunsi, R.B.R.; Pelling, M.; Roberts, D.; Solecki, W. Urban areas. In Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovern Mental Panel on Climate Change; Field, C.B., Barros, V.R., Dokken, D.J., Mach, K.J., Mastrandrea, M.D., Bilir, T.E., Chatterjee, M., Ebi, K.L., Estrada, Y.O., Genova, R.C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 535–561. [Google Scholar]

- Hansestadt Lübeck. Thematischer Landschaftsplan. Klimawandel in Lübeck. Vorsorge- und Anpassungsmaßnahmen für die Landnutzungen; Schriftenreihe Deutschen Rates Landespflege: Meckenheim, Germany, 2013; p. 32. [Google Scholar]

- Strohbach, M.V. Stadtnatur fördert Klimaschutz. In Naturkapital Deutschland TEEB (2016): Ökosystemleistungen in der Stadt. Gesundheit Schützen und Lebensqualität Erhöhen; TU Berlin, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung UFZ Berlin: Leipzig, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kuttler, W. Klimatologie, 2nd ed.; UTB Schöningh: Paderborn, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Endlicher, W.; Scherer, D.; Büter, B.; Kuttler, W.; Mathey, J.; Schneider, C. Stadtnatur fördert gutes Stadtklima. In Naturkapital Deutschland TEEB (2016): Ökosystemleistungen in der Stadt. Gesundheit Schützen und Lebensqualität Erhöhen; TU Berlin, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung UFZ Berlin: Leipzig, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Leiva, G.M.A.; Santibañez, D.A.; Ibarra, E.S.; Matus, C.P.; Seguel, R. A five-year study of particulate matter (PM2.5) and cerebrovascular diseases. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 181, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommer, T.; Karpf, C.; Ettrich, N.; Haase, D.; Weichel, T.; Peetz, J.-V.; Steckel, B.; Eulitz, K.; Ullrich, K. Coupled modelling of subsurface water flux for an integrated flood risk management. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2009, 9, 1277–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haase, D. Effects of urbanisation on the water balance—A long-term trajectory. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2009, 29, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuste, J.; Haase, D.; Elmqvist, T. Urban landscapes and ecosystem services. In Ecosystem Services in Agricultural and Urban Landscapes; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 83–104. [Google Scholar]

- Bögeholz, S. Qualitäten Primärer Naturerfahrung und Ihr Zusammenhang mit Umweltwissen und Umwelthandeln; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Naturbewusstsein 2013. Bevölkerungsumfrage zu Natur und biologischer Vielfalt; Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz und Reaktorsicherheit, Bundesministerium für Naturschutz, Eds.; BMUB; BfN: Berlin/Bonn, Germany, 2014.

- Riechers, M.; Barkmann, J.; Tscharntke, T. Bewertung Kultureller Ökosystemleistungen von Berliner Stadtgrün Entlang Eines Urbanen-Periurbanen Gradienten; Diskussionspapiere No. 1507; PUBLISSO: Göttingen, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lohrberg, F.; Timpe, A. Urbane Agrikultur–Neue Formen der Primärproduktion in der Stadt. Planerin 2011, 5, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Brenck, M.; Hansjürgens, B.; Haase, D.; Hartje, V.; Kabisch, N.; Ring, I.; Born, W. Ansätze zur Erfassung und Bewertung städtischer Ökosystemleistungen. In Naturkapital Deutschland TEEB (2016): Ökosystemleistungen in der Stadt. Gesundheit Schützen und Lebensqualität Erhöhen; TU Berlin, Helmholtz-Zentrum für Umweltforschung UFZ Berlin: Leipzig, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Typical Hemeroby Degrees after Blume and Sukopp [33] | Reclassified Urban Hemeroby Degrees |

|---|---|

| 1 ahemorob—almost no human impact | - |

| 2 oligohemerob—weak human impact | 1 Conditionally natural |

| 3 mesohemerob—moderate human impact | 2 Close to nature |

| 4 ß-euhemerob—moderate–strong human impact | 3 Conditionally close to nature |

| 4 Semi-natural | |

| 5 α-euhemerob—strong human impact | 5 Conditionally unnatural |

| 6 Far from nature | |

| 6 polyhemerob—very strong human impact | 7 Very far from nature |

| 8 Conditionally non-natural | |

| 7 metahemerob—excessively strong human impact | 9 Non-natural |

| 10 Artificial |

| Hemeroby | Hemeroby Designation | Built-up Area (According to the Regional Biotope and Land Use Data Set) | Others 1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Conditionally natural | - | (Mixed) forest, bog |

| 2 | Close to nature | - | Forest, group of trees, bushes |

| 3 | Conditionally close to nature | Sealing degree < 25% and wood cover > 50% | Natural grassland |

| 4 | Semi-natural | Sealing degree 25–50% and wood cover 10–50%; | Grassland |

| Sealing degree < 25% and wood cover 10–50% | |||

| 5 | Conditionally unnatural | Sealing degree < 25% and single trees (max. 10%) | Intensively used grassland, agriculture |

| 6 | Far from nature | Sealing degree 25–50% and wood cover 10–50%; | |

| Sealing degree 50–75% and wood cover > 50%; | |||

| 7 | Very far from nature | Sealing degree 50–75% and wood cover 10–50%; | |

| Sealing degree 25–50% and single trees (max. 10%); | |||

| Sealing degree 25% and wood-free area | |||

| 8 | Conditionally non-natural | Sealing degree 50–75% and single trees (max. 10%); | |

| Sealing degree 25–50% and wood-free area; | |||

| Sealing degree 75–100% and wood cover 10–50% | |||

| 9 | Non-natural | Sealing degree 75–100% and single trees (max. 10%); | |

| Sealing degree 0–75% and wood-free area | |||

| 10 | Artificial | Sealing degree 75–100% and wood-free area |

| Mapping Unit | Land Use Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Forest | Woody areas with closed canopy and a mean size of over two hectares are mapped as forest. |

| 2 | Woody plants | Woody plants are areas with open canopy structures/dingle trees or are less than two hectares in size. Furthermore, all bushes are recorded in this unit. |

| 3 | Herbaceous vegetation | Herbaceous vegetation includes grasslands, perennial meadows and moors with less than 75% shrub cover. |

| 4 | Water | All open water areas are classified as water. |

| 5 | Vegetation-free area | Vegetation-free areas are bare soil and/or rocky areas that are covered by loose vegetation to a maximum of 50%. |

| 6 | Agriculture | All arable land, horticulture and viticulture. |

| 7 | Built-up area | All urban areas, urban green areas, traffic areas, river crossings and construction sites. |

| Ecosystem Service Group | Ecosystem Service | Positive Effects by Green Spaces in Urban Areas |

|---|---|---|

| Regulating ES | Global climate regulation | |

| Local climate regulation |

| |

| ||

| Air pollution control |

| |

| ||

| Water cycle regulation |

| |

| Cultural ES | Recreation: nature experience and social interactions/leisure activities | |

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| ||

| Provisioning ES | Food supply |

|

|

| Urban Hemeroby Degrees | Example | Index Value Urban Hemeroby |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mixed forest | 100 |

| 2 | Forest as monoculture | 90 |

| 3 | Park with sealing degree < 25% and wood cover > 50% | 80 |

| 4 | Allotment garden with sealing degree < 25% and wood cover 10–50% | 70 |

| 5 | Park with sealing degree < 25% and single trees (max. 10%) | 60 |

| 6 | Housing estate with sealing degree 25–50% and wood cover 10–50% | 50 |

| 7 | Row houses with sealing degree 50–75% and wood cover 10–50% | 40 |

| 8 | Condensed living area with sealing degree 50–75% and single trees (max. 10%) | 30 |

| 9 | City center with sealing degree 75–100% and single trees (max. 10%) | 20 |

| 10 | Street with sealing degree 75–100% and wood-free area | 0–10 |

| Biotope and Land Use Data Set (See Section 2.3.2) | Global Climate Regulation | Local Climate Regulation | Air Pollution Control | Water Cycle Regulation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM | D | BM | D | BM | D | BM | D | |

| 1 = Forest | 5 | 0% | 5 | 0% | 5 | 0% | 3 | −20% |

| 2 = Woody plants | ||||||||

| 3a = Natural grassland | 5 | 0% | 2 | −30% | 0 | −50% | 1 | −40% |

| 3b = Grassland | 2 | −30% | 1 | −40% | 0 | −50% | 1 | −40% |

| 5 = Vegetation-free area | 0 | −50% | 1 | −40% | 0 | −50% | 1 | −40% |

| 6 = Agriculture | 1 | −40% | 2 | −30% | 1 | −40% | 1 | −40% |

| 7a = Green urban areas | 2 | −30% | 2 | −30% | 2 | −30% | 2 | −30% |

| 7b = Residential and mixed-use areas | 0 | −50% | 0 | −50% | 0 | −50% | 0 | −50% |

| 7c = Industrial or commercial areas | 0 | −50% | 0 | −50% | 0 | −50% | 0 | −50% |

| 7d = Allotment gardens | 1 | −40% | 2 | −30% | 1 | −40% | 1 | −40% |

| 7e = Traffic areas | 0 | −50% | 0 | −50% | 0 | −50% | 0 | −50% |

| Biotope and Land Use Types that Are Open for Public (See Section 2.3.3) | Hemeroby Degree by Walz and Stein (2014) [32] | Devaluation of the Hemeroby Index Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 = Forest | 1–3 | 0% |

| 2 = Woody plants | ||

| 3a = Natural grassland | 3 | 0% |

| 3b = Grassland | 4 | −10% |

| 5 = Vegetation-free area | 3 | 0% |

| 7a = Green urban areas | 4 | −10% |

| 7b = Public residential and mixed-use areas | 7 | −40% |

| Urban Hemeroby Degrees | Example | Index Values Urban Hemeroby |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mixed forest | 60 |

| 2 | Group of trees | 70 |

| 3 | Park with wood cover > 50% | 80 |

| 4 | Park with wood cover 10–50% | 90 |

| 5 | Park with sport area, playing field (sealing degree < 25% and single trees) | 100 |

| 6 | Park with sport area, playing field (sealing degree 25–50% and wood cover 10–50%) | 90 |

| 7 | Public residential area with sealing degree 50–75% and wood cover 10–50% | 80 |

| 8 | Public residential area with sealing degree 50–75% and single trees (max. 10%) | 70 |

| 9 | Public residential area with sealing degree 75–100% and single trees (max. 10%) | 60 |

| 10 | Town square (sealing degree 75–100% and wood-free area) | 50 |

| Biotope and Land Use Data Types (BTNT) | Likert Scale | Normalized Index Values in GISCAME |

|---|---|---|

| 6 = Agriculture | Very high | 100 |

| 7d = Allotment gardens | High | 75 |

| All other BTNT with hemeroby degree 1–3 | Medium | 50 |

| All other BTNT with hemeroby degree 4–7 | Low | 25 |

| All other BTNT with hemeroby degree 8–10 | Very low/no | 0 |

| BTNT (See Section 2.3.2) | Access-Ibility | Hemeroby Degrees in Percentage (%) of the City of Halle | Percent of the City of Halle | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1 = Forest | Public | 8.77 | 1.65 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 10.42 |

| 2 = Woody plants | Public | - | 1.89 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.89 |

| 3a = Herbaceous vegetation | Public | 0.19 | - | 2.43 | 13.44 | 0.21 | - | - | - | - | - | 16.27 |

| 4 = Water | Public | - | 3.16 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 5 = Vegetation-free area | Public | 0.02 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.11 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.44 | |

| 6 = Agriculture | Private | - | - | - | - | 21.29 | - | - | - | - | - | 21.29 |

| 7a = Green urban areas | Public | - | - | 1.16 | 0.99 | 0.61 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.05 | - | - | 3.03 |

| 7b = Residential and mixed-use areas | Public | - | - | - | 0.35 | 0.17 | 2.06 | 2.39 | 0.39 | 0.13 | - | 5.74 |

| 7b = Residential and mixed-use areas | Private | - | - | 0.13 | 4.37 | 0.59 | 2.21 | 2.78 | 2.35 | 3.69 | 0.01 | 16.13 |

| 7c = Industrial or commercial areas | Private | - | - | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.46 | 0.93 | 2.88 | 4.37 | 0.28 | 9.19 |

| 7d = Allotment gardens | Private | - | - | 0.68 | 4.94 | 0.91 | - | - | - | - | - | 6.53 |

| 7e = Traffic areas | Private | - | - | - | - | - | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 1.48 | 2.04 | 3.66 |

| 7f = Sports and leisure facilities | Private | - | - | - | 0.12 | 0.50 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.33 | - | 1.38 |

| 7g = Remaining built-up area | Private | - | - | - | 0.02 | - | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.58 | - | 0.87 |

| Most Common Biotope and Land Use Types (See Section 2.3.2) | ES Values from Burkhard et al. (2014) [31] and Devaluation in Percent | Values for Global Climate Regulation for Each Hemeroby Degree Based on the Formula Described in Section 2.5.1 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1 = Forest | 5 | 0% | 100 | 90 | ||||||||

| 2 = Woody plants | ||||||||||||

| 3a = Natural grassland | 5 | 0% | 80 | |||||||||

| 3b = Grassland | 2 | −30% | 49 | 42 | ||||||||

| 6 = Agriculture | 1 | −40% | 36 | |||||||||

| 7a = Green urban areas | 2 | −30% | 56 | 49 | 42 | 35 | 28 | 21 | ||||

| 7b = Residential and mixed-use areas | 0 | −50% | 40 | 35 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 5 | ||

| 7c = Industrial or commercial areas | 0 | −50% | 40 | 35 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 0 | ||

| 7d = Allotment gardens | 1 | −40% | 48 | 42 | 36 | |||||||

| Most Common Biotope and Land Use Types (See Section 2.3.2) | ES Values from Burkhard et al. (2014) [31] and Devaluation in Percent | Values for Local Climate Regulation for Each Hemeroby Degree Based on the Formula Described in Section 2.5.1 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1 = Forest | 5 | 0% | 100 | 90 | ||||||||

| 2 = Woody plants | ||||||||||||

| 3a = Natural grassland | 2 | −30% | 56 | |||||||||

| 3b = Grassland | 2 | −30% | 49 | 42 | ||||||||

| 6 = Agriculture | 2 | −30% | 42 | |||||||||

| 7a = Green urban areas | 2 | −30% | 56 | 49 | 42 | 35 | 28 | 21 | ||||

| 7b = Residential and mixed-use areas | 0 | −50% | 40 | 35 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 5 | ||

| 7c = Industrial or commercial areas | 0 | −50% | 40 | 35 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 0 | ||

| 7d = Allotment gardens | 2 | −30% | 56 | 49 | 42 | |||||||

| Most Common Biotope and Land Use Types (See Section 2.3.2) | ES Values from Burkhard et al. (2014) [31] and Devaluation in Percent | Values for Air Pollution Control for Each Hemeroby Degree Based on the Formula Described in Section 2.5.1 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1 = Forest | 5 | 0% | 100 | 90 | ||||||||

| 2 = Woody plants | ||||||||||||

| 3a = Natural grassland | 1 | −40% | 48 | |||||||||

| 3b = Grassland | 1 | −40% | 42 | 36 | ||||||||

| 6 = Agriculture | 1 | −40% | 36 | |||||||||

| 7a = Green urban areas | 2 | −30% | 56 | 49 | 42 | 35 | 28 | 21 | ||||

| 7b = Residential and mixed-use areas | 0 | −50% | 40 | 35 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 5 | ||

| 7c = Industrial or commercial areas | 0 | −50% | 40 | 35 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 0 | ||

| 7d = Allotment gardens | 1 | −40% | 48 | 42 | 36 | |||||||

| Most Common Biotope and Land Use Types (See Section 2.3.2) | ES Values from Burkhard et al. (2014) [31] and Devaluation in Percent | Values for Water Cycle Regulation for Each Hemeroby Degree Based on the Formula Described in Section 2.5.1 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1 = Forest | 3 | −20% | 80 | 72 | ||||||||

| 2 = Woody plants | ||||||||||||

| 3a = Natural grassland | 1 | −40% | 48 | |||||||||

| 3b = Grassland | 1 | −40% | 42 | 36 | ||||||||

| 6 = Agriculture | 1 | −40% | 36 | |||||||||

| 7a = Green urban areas | 2 | −30% | 56 | 49 | 42 | 35 | 28 | 21 | ||||

| 7b = Residential and mixed-use areas | 0 | −50% | 40 | 35 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 5 | ||

| 7c = Industrial or commercial areas | 0 | −50% | 40 | 35 | 30 | 25 | 20 | 15 | 10 | 0 | ||

| 7d = Allotment gardens | 1 | −40% | 48 | 42 | 36 | |||||||

| Most Common Biotope and Land Use Types (See Section 2.3.2) | Devaluation in % | Private /Public | Values for Nature Experience Based on the Formula Described in Section 2.5.2 | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1 = Forest | 0 | public | 100 | 90 | ||||||||

| 2 = Woody plants | ||||||||||||

| 3a = Natural grassland | 0 | public | 80 | |||||||||

| 3b = Grassland | −10 | public | 63 | 54 | ||||||||

| 6 = Agriculture | - | private | 0 | |||||||||

| 7a = Green urban areas | −10 | public | 72 | 63 | 54 | 45 | 36 | 27 | ||||

| 7b = Residential and mixed-use areas | −40 | public | 48 | 42 | 36 | 30 | 24 | 18 | 12 | 6 | ||

| 7b = Residential and mixed-use areas | - | private | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 7c = Industrial or commercial areas | - | private | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 7d = Allotment gardens | - | private | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Most Common Biotope and Land Use Types (See Section 2.3.2) | Devaluation in % | Private/Public | Values for Social Interaction and Leisure Activities Based on Table 8 | |||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| 1 = Forest | 0 | public | 60 | 70 | ||||||||

| 2 = Woody plants | ||||||||||||

| 3a = Natural grassland | 0 | public | 80 | |||||||||

| 3b = Grassland | −10 | public | 90 | 100 | ||||||||

| 6 = Agriculture | - | private | 0 | |||||||||

| 7a = Green urban areas | −10 | public | 80 | 90 | 100 | 90 | 80 | 70 | ||||

| 7b = Residential and mixed-use areas | −40 | public | 80 | 90 | 100 | 90 | 80 | 70 | 60 | 50 | ||

| 7b = Residential and mixed-use areas | - | private | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 7c = Industrial or commercial areas | - | private | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 7d = Allotment gardens | - | private | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||||||

| Most Common Biotope and Land Use Types (See Section 2.3.2) | Values for Food Supply Based on Table 9 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| 1 = Forest | 50 | 50 | ||||||||

| 2 = Woody plants | ||||||||||

| 3a = Natural grassland | 50 | |||||||||

| 3b = Grassland | 25 | 25 | ||||||||

| 6 = Agriculture | 100 | |||||||||

| 7a = Green urban areas | 50 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 0 | ||||

| 7b = Residential and mixed-use areas | 50 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 7c = Industrial or commercial areas | 50 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 7d = Allotment gardens | 75 | 75 | 75 | |||||||

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arnold, J.; Kleemann, J.; Fürst, C. A Differentiated Spatial Assessment of Urban Ecosystem Services Based on Land Use Data in Halle, Germany. Land 2018, 7, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7030101

Arnold J, Kleemann J, Fürst C. A Differentiated Spatial Assessment of Urban Ecosystem Services Based on Land Use Data in Halle, Germany. Land. 2018; 7(3):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7030101

Chicago/Turabian StyleArnold, Janis, Janina Kleemann, and Christine Fürst. 2018. "A Differentiated Spatial Assessment of Urban Ecosystem Services Based on Land Use Data in Halle, Germany" Land 7, no. 3: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7030101

APA StyleArnold, J., Kleemann, J., & Fürst, C. (2018). A Differentiated Spatial Assessment of Urban Ecosystem Services Based on Land Use Data in Halle, Germany. Land, 7(3), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/land7030101