1. Introduction

Since the Doi Moi Policy of 1986, Vietnam has promoted a strategy of industrialization and urbanization [

1]. This strategy has significantly increased the economic performance of the whole country [

2]. As a result, however, over 10 million hectares of agricultural land have been acquired to be converted to non-agricultural land, most of which has fertile soil [

3]. According to the General Statistics Office (GSO), Vietnam is an agricultural country, with approximately 70% of the population living in rural areas that are dependent on agriculture [

4]. Access to natural resources (especially land resources) is an essential factor to rural livelihoods [

5]. The agricultural land acquisition (ALA) policy, which has changed rural livelihoods and the socio-economic status of rural people, has had both negative and positive consequences. Several researchers have brought attention to the increasing unemployment and poverty in the affected communes after ALA [

1,

6,

7], while other researchers have revealed that agricultural landlessness led to an increasing rural labor force in the non-farming sectors, which can significantly contribute to poverty reduction in rural areas [

8]. Other studies have shown that the income of affected households has increased more than before ALA [

9,

10]. Furthermore, the country report of 2013 concluded that the lack of productive land promoted the migration of rural labor to urban areas; therefore, ALA positively changed socioeconomic conditions in rural areas [

11,

12,

13].

Women are one of the most vulnerable groups in the rural society [

14]. In Vietnam, the Government has made impressive progress for rural women regarding access to productive resources, improved income, health care and education to narrow gender inequity. However, the socioeconomic status (SES) of rural women depends mostly on natural resources [

15]. According to United Nations Women (UNW), 63.4% of rural women in Vietnam work in the agricultural sector and have low incomes [

16], leading to the limited occupational and economic status of most rural women. The International Labour Organization (ILO) also reported that most rural women are not well educated, as 86.5% of rural women do not have any vocational skills [

17]. As a result, their social status is still low [

16].

In the context of ALA, we focus on (i) how ALA impacts the SES of rural women, (ii) whether ALA for different purposes leads to different impacts on SES of rural women, and (iii) how stakeholders of ALA projects have supported and influenced the search for new jobs for rural women after ALA. Previous research has not considered these questions; therefore, we assess the change of occupation, income and socioeconomic knowledge of rural women before and after ALA to determine whether their SES has increased or decreased. We then compare their changing SES in three different zones of Huong Thuy town in Thua Thien Hue province, where agricultural land has been quickly acquired since the 2000s, to determine the different impacts on SES of rural women. Zone 1 is where ALA is used for city expansion and is very close to the city, Zone 2 is where ALA is used for industrial zone construction and is far from the city (yet has good roads connecting to the city), and Zone 3 is where ALA is used for hydropower construction and is located in remote areas. Moreover, we list stakeholders of ALA projects and evaluate their support and influence on the changing SES of women. Based on this, we show the gaps of ALA policy that need to be improved.

We assume that both ALA and gaps in the ALA policy lower the enhancement of SES for rural women. Furthermore, different purposes of ALA can lead to different impacts on rural women. We apply the sustainable livelihoods framework of the Department for International Development (DFID) to analyze the change of occupation and income of rural women. While analyzing the change, we also aim to understand the causes of the change in order to identify causes that are related to ALA. We also discuss with rural women and stakeholders to identify what challenges and opportunities ALA brings them and how stakeholders support and influence the SES of the women. With this information, we show the gaps of ALA policy and the link between ALA and SES of rural women.

For data collection, we used the gender approach and the bottom-up approach to increase the participation of the local people, rural women and stakeholders. We mixed both quantitative and qualitative data to provide comprehensive arguments in our paper. The research method is described in

Section 3 and results are contained in

Section 4, followed by discussion and policy implications in

Section 5 and

Section 6.

2. Conceptual Framework

In practice, the conversion of agricultural land for urbanization and industrialization is an indispensable trend in developing countries [

18]. In Vietnam, ALA for non-agricultural purposes is also a fundamental institutional framework to support the economic development that will turn Vietnam into an industrialized country by 2020 [

2]. According to the land law of 2003, land resources belong to the Vietnamese people, with the Vietnamese State as the representative owner. The State manages the land, makes land use planning decisions, and distributes land resources to people (land users) by issuing land use certificates. Land users can be individuals, households or organizations. They have the right to use the land, and they can also sell or transfer their land use right. Generally, most people living in rural areas are farmers and have an equally distributed agricultural land use right in the long term. When the State wants to convert agricultural land to other types of land for investors, however, the State and the investors have to create an ALA plan, compensation and livelihood support program. Then, they announce the plan and program to the affected land users to have them (the land users) return their agricultural land use right to the State. In return, the affected land users receive compensation for losing the land use right through a monetary payment or a land use right elsewhere. They are also supported in rehabilitating their livelihoods. Therefore, the term “agricultural land acquisition” in our study is the process of the State recovering agricultural land use rights from land users and compensating them based on the compensation and livelihood support policy that was issued by the State in the land law. Affected people are required to return their land use right without any negotiation of the amount of compensation with the State or investors. Therefore, ALA leads to a decrease in access to agricultural land for affected people (rural women included). The affected people can also receive other indirect benefits associated with implementing non-agricultural projects, such as non-agriculture job opportunities in factories, companies or small businesses, improved infrastructure, and various services. In many cases, however, ALA has led to a conflict between the affected people and the investor or the State because of the inadequate compensation and support policy [

2,

19].

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a complex term used to classify a group or an individual in a society [

20,

21]. In recent decades, many definitions of SES have been released, most of which incorporate education level, representing social status; income amount, representing economic status; and type of occupation, representing work status. Income is an important index of SES because it directly impacts health, access to goods, access to services, and increases the power in the family, but is also controlled by occupation and education level and vice versa. We can measure income through various aspects, namely family income, individual income, wealth, or savings. Education can be measured through either the number of years of school completed or the level of the education program completed. A high education level often relates to a high income and good occupation [

21]. We can evaluate occupation based on occupation prestige (goodness, status, worth, power), social class (working position, occupational title) or based on education requirements [

22].

Based on this, there are many ways to improve the SES of an individual or a group, such as increasing income, improving education level, attaining a better job, or all of the above. With rural women, improving SES is an important target in the sustainable development strategy all over the world [

23,

24]. Characteristics of their SES are a low education level, low income and unstable employment. So, the stability and security of occupations, types of job and income amounts are the main aspects in assessing the work and economic status of rural women [

24]. In terms of social status, vocational skills and socioeconomic knowledge must also be assessed [

23].

To assess the SES of rural women in our research, aspects of work status are investigated including the type of job, stability of job (number of working days per year), occupational security (working contract and working insurance), independence (self-employment, employee or employer), working pressure (number of working hours per day), and income. Most rural women are adults or middle-aged with a given education level that does not change over time [

25,

26]. To determine their social status, we focus on socioeconomic knowledge and vocational skills more than education level. For economic status, we only focus on their average daily income.

The SES of rural women is the consequence of their livelihood activities, which are mostly dependent on natural resources, including land, water, and natural forest [

27]. Among these resources, agricultural land is the most important factor for rural development, as access to it is key to the livelihoods of farmers as well as economic growth [

5,

28]. Decreasing access to land resources might lead to difficulties in the livelihood activities and SES of rural women [

28]. In recent decades, increasing access to land resources has been one of the solutions that has been applied in most developing countries to improve the SES of rural women [

14].

To show the link between ALA and the SES of rural women, we use the sustainable livelihoods framework designed by DFID that has been already applied in many rural livelihood development programs [

29]. According to this framework, natural resources are one of five livelihood assets. The accessibility of these natural resources has impacts on the others assets and vice versa. Along with the other assets, vulnerabilities and institutions/policies control the livelihood strategies, contributing to livelihood outcomes such as income, wealth, well-being, and food security [

30]. Based on this framework, we built a conceptual framework for our study. This framework shows the relationship between ALA and SES for rural women (

Figure 1).

Following this framework, ALA includes three components. The first component is the agricultural land use right recovery that leads to the loss of agricultural land as well as other natural resources, meaning reduced natural assets. The second component is the compensation and support program, in which the compensation could increase financial assets directly via cash payment, and the support program could increase human assets via vocational training courses. The final component is the non-agricultural project implementation, which could create new job opportunities and increase physical assets through an infrastructure construction project. Changing livelihood assets and new job opportunities lead to changing livelihood strategies of rural women, and as a result, their SES changes.

4. Findings

4.1. Characteristics of Surveyed Households and Women at the Study Sites

The similar percentage of laborers of the surveyed households and the average percentage of laborers in each zone as a whole indicate that our study sample is representative of the population. This sample size is also representative of the entire population when based on female laborers (

Table 1). In each of the 50 surveyed households, the number of women who had been laborers before ALA (over 18 years old) and were still laborers (under 55 years old) at the time of the survey is different between the studied zones. A total of 60 women in Zone 1, 56 women in Zone 2, and 52 women in Zone 3 were included in the study. Although each zone was different before the ALA period (2004, 2008, 2012), data from the survey show that the average age of affected women is rather similar (around 40-45 years old). This is explained by the application of the agricultural land policy in 1993 and the rural context in Vietnam. The agricultural land was equally allocated for all people who were residing in the rural area from 1993 until now. This means that people who were born after 1993 in rural areas were not issued agricultural land, and for people who died after 1993, their land belongs to their family after their death. In addition, since the 2000s, education and industry have been strongly promoted across the country; many young people who were born after 1980s in rural areas have been highly educated and have moved out of agricultural activities or no longer depend on agricultural land. Put another way, at present, most of the people who still depend on agricultural land were born in the period before the 1980s in rural areas because they still have agricultural land use rights and their education is limited (especially women). From this situation, the age of affected women in our research is not different between the three zones although each zone has different ALA implementation periods.

In Zone 1 and Zone 2, the women had passed primary and high school education, but in Zone 3, all women had only primary school education because they lived on boats until 1975, when they resettled in the Duong Hoa commune. Furthermore, before the 2000s, girls in rural areas of Vietnam were educationally limited due to male chauvinism. Given these influences, women may have faced difficulties in looking for new jobs after ALA.

4.2. Changing Work Status of Rural Women

Work status is one of the key factors that may hinder or improve the lives of rural women and also change their attitudes [

38,

39]. We studied how the employment of women has changed after ALA.

The data in

Table 2 shows the employment changes of the women in each zone. The biggest change occurred in Zone 1, where women have changed their jobs from agriculture to non-agriculture; the percentage of women specializing in agriculture decreased from 36.7% before ALA to 11.7% at present. During this same time period, the percentage of women running small businesses increased from 10% to 31.7% and the percentage of women working as hired labor rose from 11.6% to 20%. The total percentage of women participating in non-farm jobs dramatically increased from 63.3% to 88.3%.

The employment of women in Zone 3 is less diverse than in Zone 1. Before ALA, 96.2% of women were specialized in farming; they cultivated rice and vegetables, bred animals, exploited natural forestry, and planted forests. However, this percentage is now only 11.4%, and most of the women have participated in animal breeding and forestry. At present, a high percentage of women (70.6%) in Zone 3 have been working as both farmers and hired labor. The hired laborers mainly care for the plants of the forest owners; however, this job is neither always available nor near their commune, and they have therefore tried to continue cultivation and animal husbandry in their yards or on their remaining agricultural land in their free time to provide food for their family.

In Zone 2, women also had to change their occupation. Many women (69.6%) were specialized in agriculture before ALA, while others were hired laborers (3.6%) or dealers with small-scale businesses (10.7%). At the time of the survey, many women are working as hired laborers and farmers (48.2%), while others have become small businesswomen (19.6%), workers in industrial zones (7.1%) or specialized hired laborers (12.5%). When the construction of the industrial zone started, all people who had lost land had been promised jobs in the factories or companies of the industrial zone, but most of them—especially women—were turned away because of their age and lack of working skills. Women then started to look for alternative jobs, of which hired labor is the most popular.

Besides changing occupations, the characteristics of each type of job also show the occupational status of rural women. In

Table 3, we see the differential increases in working days, working hours and the income of each job. However, based on the ranking in the group discussion, there is no change in job classification. Civil servants, workers and small businesswomen are ranked as a good status (the good job group) both before ALA and presently because these jobs have a high number of working days (from 270 to 360 days/year), a good income, and working contracts (or are independent work).

In contrast, farmers and hired laborers are classified in the bad status (bad job group), both before ALA and at present, because these jobs have a low number of working days per year and high working pressure without a contract (hired labor), respectively. “Although women could get an alternative job quickly and avoid unemployment, some kinds of jobs entail high risks and pressure. Hired labor could involve spiritual violence (such as being despised, disrespected and sworn at by the owner) or overuse by the boss. Most women have also not been trained or learned any working skills related to their work in advance and thus have to spend between one and three extra hard-working months to be accepted. During this time, they could lose their job at any time because they do not have a working contract and insurance.” (Source: Key informant interview, Phu Bai ward, Zone 2).

Based on this result, we recognize that the occupational status of rural women at present has improved, with the clearest improvement being in Zone 1, where the total percentage of women who are working in the good job group increased to 45%. In Zone 2 and Zone 3, although the percentage of women working in the good job group is still low, the percentage of women working in the bad job group decreased from 73.5% to 25% and from 96.15% to 21.57%, respectively.

While the percentage of job changes for rural women is different among the studied zones, the trend from agricultural to non-agricultural jobs is the same. To understand how ALA contributed to this change, we asked the women about the reasons for their job changes and then grouped these reasons into three main groups: directly due to ALA (landless, compensation and support), indirectly due to ALA (infrastructure development of non-agricultural projects which came from ALA, new job opportunities from new businesses around industrial zones and expanded zones of city), and other reasons (age, health, working skills, common trend, etc.).

Many women selected direct or indirect reasons for their job change (

Table 4). A total of 70% of women in Zone 1 changed their job, of which 52.4% changed their job because of agricultural landlessness, 83.3% changed their job due to jobs from new businesses around industrial zones and expanded zones of the city, and 47.6% changed their job due to infrastructure development of non-agricultural projects after ALA. “Since 2010, ALA for city expansion has led to infrastructure development in and around our commune. Many new residents have moved to our commune and many new businesses have opened. We don’t have land anymore, so we have carefully learned from each other how to improve our skills in order to get new full-time jobs from the non-farm sector. As a result, we can not only take new jobs, but our working days are also higher. Until now, we still have a small agricultural land area, but we hope it will be acquired soon, so we can get compensation and then totally invest our time in off-farm activities.” (Source: Key informant interview, Thuy Van commune, Zone 1).

In Zone 3, 86.5% of women have changed their job and 100% of them changed because of agricultural landlessness due to ALA. At present in Zone 2, 72% of women have changed their job, of which 62.8% changed jobs due to ALA, 52.5 % of them changed jobs associated with infrastructure development, and 40% of them changed jobs because of new business facilities around industrial zones and expanded zones of the city. “After ALA, we could easily and quickly go to Hue city, Phu Bai ward or Huong Thuy town to work because the infrastructure developed. We can spend all our time on new work, so we can get to new jobs as sellers, maids and babysitters easier than before ALA. Therefore, our working days increased. Outside of working time, we can quickly go back home, cultivate vegetables and breed chickens for family food purposes. Ever since the industrial zone started operation, more workers have come to the area, so some women with good enterprise skills have opened small and cheap food shops or small variety stores.” (Source: Key informant interview, Thuy Phu commune, Zone 2).

4.3. Changing Economic Status of Rural Women

Due to the different employment opportunities between the three zones, the total working days and income of women in each zone changed compared to before ALA. The average number of working days per year of women in all three zones has dramatically increased (

Table 5); the number of working days in Zone 1 is the highest, with 315.7 days per year, and the lowest is in Zone 3, with 208.4 days per year. Women in Zone 3 are jobless nearly five months out of the year, which has notably increased compared to before ALA. This also means that the average level of daily income of women in Zone 1 is highest and lowest in Zone 3.

In this table, we do not compare the income of affected women at present and before ALA because the value of money has changed during this time. We also do not compare the income per affected woman between three zones because the economic status in each zone is not similar. We do compare their income with the average income per person in each zone to indicate how it has developed. Moreover, we also compare their income with the average income per local woman to see how ALA impacted this.

This comparison demonstrates that the income difference between the average income per affected woman and the average income per person in Zone 1 at present is very wide (173.2 vs. 83.3), while before ALA it was narrow (63.9 vs. 56.7). Moreover, the average income per affected woman is also much higher than the average income per local woman at present (173.2 vs. 108.2), although it was similar before ALA. “At present, women in our commune are respected more than in the past because they have become a main income generator in their families. Even in some families, husbands stay at home and support their wife’s business. ALA still has many problems with compensation that people are still not satisfied with, but compared with the women in other nearby communes where ALA does not occur, the income of the women in our commune is higher and unemployment is lower. Therefore, many people are still expecting that their agriculture land remainder will be acquired soon for city expansion.” (Source: Key informant interview, Thuy Van commune, Zone 1).

The average income per affected woman in Zone 2 was lower than the average income per person before ALA (30.9 vs. 55.6), but is now slightly higher (127.9 vs. 111.1). This means women are the main income generators in the family and the commune. In the comparison with the average income per woman in the respective zone, the income per affected woman is slightly higher (127.9 vs. 120.1) “The new jobs request that women work hard, but we earn more money and are more respected as well. We are more independent and have higher income compared with women in other villages where agriculture is main income. We can buy anything we desire, like clothes, cosmetics or jewelry. Some of us can even give money to our parents and close relatives, which we could not do before ALA.” (Source: Key informant interview, Thuy Phu commune, Zone 2).

However, this change does not apply to women in Zone 3; although their income improved significantly over time, it is still lower than the average income per person of the commune (96.6 vs. 101.1) and the income per woman in the respective zone as well (96.6 vs. 106.2) “There are no new job opportunities associated with ALA for dam construction in our commune. We have low education, are advanced in years and live far from Hue city and Huong Thuy town. We didn’t have enough time to improve our capacity before ALA to adapt with the situation of landlessness because ALA was implemented in a hurry. Our income is still slow and unstable.” (Source: key informant interview, Duong Hoa commune, Zone 3).

4.4. Changing Social Status of Rural Women

In our research, we did not analyze the education level of these affected women because, at their age level and living condition, their education level is not possible to change. Instead, we considered the changing of their socioeconomic knowledge and ability to evaluate their social status, because these can also help women integrate into society. At group discussions in the three zones, women stated that their social interactions and social knowledge have clearly increased, especially in Zone 1. According to these women, before ALA, most of the women in all three zones stayed at home, took care of the children, and did agricultural work and housework. Their social relationships were only with family members, relatives and neighbors. Their social knowledge was also limited due to limited social interactions and low levels of education. In the past, rural women were not expected to have high education and social knowledge because it might make it harder for them to marry. However, the social status of women has been notably enhanced since ALA. First of all, women state that they understand their family’s economic activities more. Before ALA, most women only practiced agriculture under the management of their husband, who played the role of the cost–benefit calculator, but now the women themselves have to control the costs and benefits from non-farm activities. When they go out of their village to do a non-farm job, they receive more social knowledge than in the past as well. “Working in a non-farm sector helped us to have more relationships with other people from outside the commune such as customers, bosses, colleagues and new friends in the working place. We communicate and interact with each other about our employment and social information. We opened our minds and have since felt more confident and active.” (Source: Key informant interview, Thuy Van commune, Zone 1).

Besides that, increasing accessibility to social media helps both women and men access more information. According to the household survey, 58% of households used the money from compensation to buy or replace televisions, and 60% of households also bought mobile phones from that money source. Presently, 100% of households have at least one television and one mobile phone. “We have money from the compensation and support policy, so we used a part of this money to buy a television, as well as a mobile phone or smart phone. Such equipment has quickly connected us to social knowledge and information. Consequently, we are more confident and brave when arguing with other people.” (Source: Key informant interview, Thuy Phu commune, Zone 2).

Moreover, after ALA, most men work in the city or town, so they are often not available at home. This situation encourages women to play their husband’s traditional roles, such as participating in social events in the commune and with their family. As a result, day-by-day, women are more active in social interactions. “Before ALA, my wife only stayed at home, took care of our children, and did housework. But after ALA, I took a job in Da Nang city and do not have much free time anymore; she has had to participate in social events as the family representative. She is not shy anymore when interacting with people in the commune and with our relatives. In addition to my wife, most women in our village now are more active and confident. They also take care of themselves better with respect to clothes, beauty and health.” (Source: Key informant interview, Duong Hoa commune, Zone 3).

Since most women now participate in non-farm activities, they receive a higher income, more social knowledge and vocational skills. Besides that, increasing social media accessibility also helped men change their mind about equality in the family. As a result, the voice of women has risen in the family. In the group discussion, women revealed that before ALA their husbands asked for their ideas for all decisions in the family, but their ideas would be ignored. However, at present, their ideas seem to be more accepted due to their social knowledge increasing. Moreover, the more money women earn, the more respect their husbands give them. This opportunity is clearest with women in Zone 1. At the group discussion, women in Zone 2 reported that gender equity has improved because women have understood their rights and can live more independently than before ALA.

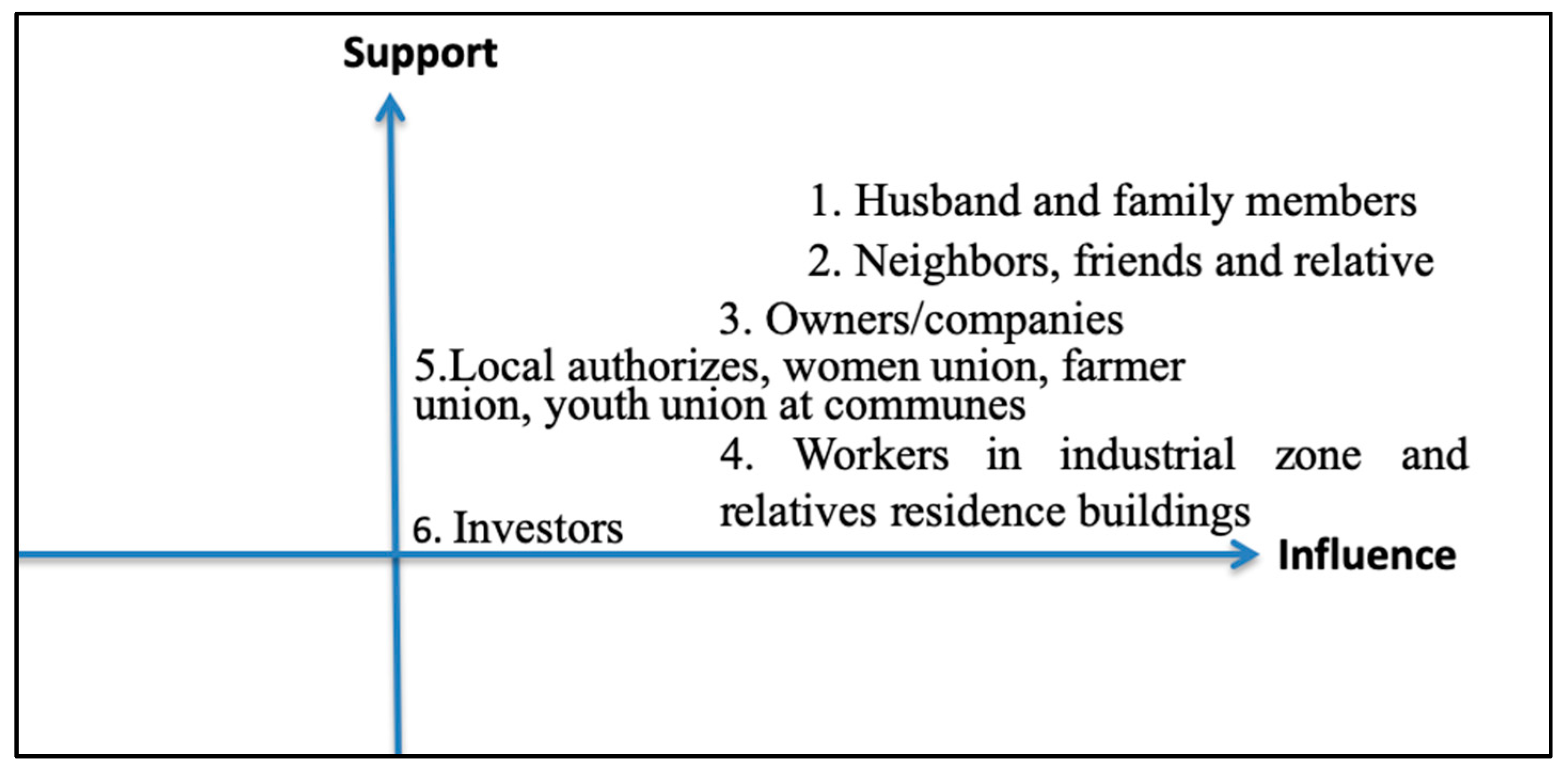

4.5. Support and Influence of Stakeholders of the ALA Project on Rural Women

The support and influence of stakeholders of the ALA project on women is very significant because it can directly impact the process by which women change their occupation, income and socioeconomic knowledge. We used power mapping in the women’s group discussion to discuss this issue. We asked women to list all stakeholders who supported and influenced them in the livelihood rehabilitation process, then grouped stakeholders by their amount of support and influence. Based on the influence and support of each group that they defined, they arranged these groups in a figure. Then, they evaluated and prioritized these groups on a scale from 1 to 6 (

Figure 3).

The women listed and evaluated six groups of stakeholders who have supported and influenced them. Among these, husbands, family members, friends, neighbors, and relatives have strongly supported and influenced them through financial support, experience, job information sharing, employment connections, and spiritual encouragement. In contrast, investors and local authorities, as well as the women’s unions, farmers, and youths were less supportive and influential. Investors only provided a small amount of money following ALA policy regulations, while local authorities only supported women if the employer requested that women submit individual documents with certificates to the Commune People Committee. “Our land use right is inadequately compensated, and their support is not significant. After taking our land use right, they forgot us, so we don’t dream about support from investors after ALA in either the short term or long term.” (Source: Key informant interview, Thuy Van commune, Zone 1).

Women expect that investors will support them to find alternative jobs and to connect them with employers or companies. This support is very important to ensure that women can get an alternative job quickly and safely. In reality, some women have given money to people who promised to find a job for them, but after receiving money, such persons disappeared. If investors or local authorities had a clear support mechanism for alternative jobs, women would not have to face such problems. “If investors had supported us before ALA by providing vocational skills training courses suitable to the working market and connected us with employers or companies, or developed new jobs at our commune, most of us would have found alternative jobs after ALA.” (Source: Key informant interview, Duong Hoa commune, Zone 3).

5. Discussion

The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) concluded that access to agricultural land is very important to rural women [

40], and many previous researchers have shown the negative impacts of ALA [

7,

9,

41]. This study, however, reveals that while ALA led to decreasing access to agricultural land, it has also created new chances for rural women to break out from the typical social preconceptions and improve their SES. Indeed, the research results show that having an agricultural land use right is a reasonable cause to ask women to stay at home, practice agriculture with low income and provide food for the family. Moreover, due to having agricultural land, most rural women also accepted that they should stay in the village to maintain their agricultural activities while their husbands migrate to the city to earn money. This point of view does not only exist in our study site, but is also very typical in other rural areas of Vietnam [

42]. However, when agricultural land accessibility ceases or is reduced by ALA projects, the men have no reason to request the women to stay at home, and the women are freer to look for non-farm jobs with higher income. Of course, looking for a new job is not easy for rural women because their skills are limited. However, with money from a compensation and support program, new job opportunities related to urbanization and industrialization, upgraded infrastructure due to non-agricultural projects, and agricultural landlessness are the main factors that create an ideal environment for women to improve their occupation and income. Taking advantage of this occasion, many rural women have successfully changed their jobs and have become the main income generator of the family. Whether pushed into or attracted to non-farm activities after ALA, most women can independently live or even provide money for their entire family. Their economic status has been noticeably upgraded. This is one of the main goals that the sustainable development and gender equality programs are expected to achieve [

43]. In addition to being the main income generator, rural women’s income sources have also diversified more than before ALA. Even with their limited education, some kinds of non-farm jobs that ALA created for urbanization and industrialization are suitable to rural women’s skills. This evidence is also very significant for rural development because the income diversification from the non-farm sector is one of the most important issues in rural sustainable livelihood development under the context of degradation of natural resources [

30].

Not only has economic and occupational status increased, ALA has indirectly provided chances for women to improve their working capacity and socioeconomic knowledge. They become more confident after working in non-farm sector jobs because the new working environment gives them chances to learn and exchange socioeconomic information, cultural skills, vocational skills, and working market knowledge. Their thinking is more open and active. As a result, their ideas and arguments are more respected, and their position and voice in the family have improved. This is one of the indirect impacts of ALA. Many gender equity programs were applied during the past few decades, but these above-mentioned changes are not easy to achieve in rural areas in Vietnam because of long-lasting gender discrimination [

42,

44]. This study does not reject the importance of access to agricultural land to rural women, but in the context of low effective agricultural production, urbanization and industrialization, ALA for non-agriculture projects could also be a good solution to improve the SES of rural women.

In the argument at the Expert Group Meeting in 2001 at Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia, UNW stated that the change of socioeconomic conditions might provide opportunities for rural women to improve their income, but the changes also impact them negatively because they do not have important skills to achieve sustainable success [

9,

13,

23,

38]. Results from this research also support the UNW’s argument. Although after ALA, women could get new employment from non-farm sectors, most of these jobs were informal paid work without working contracts and health insurance. Working requirements also seemed to be higher than the average woman’s skills, so they were faced with more pressure from the new working environment and the instability of an alternative job. These problems have also occurred in many other rural areas in Vietnam, especially in places where urbanization and industrialism have strongly increased [

42,

45]. This means ALA projects have improved the SES of rural women, but this improvement has not yet been sustainable. Data and information in this study also show that these above-mentioned difficulties derived mostly from the unreasonable support and compensation plans of the ALA projects. Many researchers have mentioned the inadequate compensation price and support for livelihood rehabilitation, since affected people need more support in the long term. A vague and late announcement about an agricultural land acquisition plan also pushes people into a defensive position. Most steps of ALA projects did not involve the participation of the affected people, yet this is key for the success of the rural development program. This situation has also occurred in many ALA projects around the country [

46,

47,

48] and could have been limited if all steps of ALA projects had been set up logically with participation from the affected people.

United Nations Women also emphasized that to reduce the vulnerability associated with the change of socioeconomic conditions, rural women need an appropriate support system that assists them in the short term and that improves their human capital and resource access in the long term [

23]. This means that when agricultural land (i.e., an important factor of their livelihoods) is acquired, rural women need to be supported to improve their skills as soon as possible. Research findings in this study also show that although the educational levels of women are quite similar, women who had improved their working skills before ALA (women in Zone 1) got a new job more easily compared with others who had not yet improved their skills (women in Zones 2 and Zone 3). This paper also indicates that the support and influence of important stakeholders such as investors and local authorities are very low, even though these stakeholders are the main beneficiaries of ALA projects. Moreover, although women were listed as the most vulnerable group in rural society, the ALA projects do not have any specific support policy or action to help them after ALA. The support for affected people including women does not differ among ALA projects while the benefits from each ALA project are different. In this research, ALA projects associated with urbanization often create more new livelihood opportunities, but ALA projects associated with hydropower or highway development often create more difficulties for affected people. These gaps have led to different impacts on women, which lead to conflict or inequity in community development and gender equity.

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

This paper studies the impacts of ALA for non-agricultural purposes on the SES of rural women by comparing their SES before and after ALA. The occupational status of women has changed from agricultural to non-agricultural activities. ALA is one of the important causes of this shift because it has not only required women to change jobs, but has also indirectly created new non-farm job opportunities, as well as developing infrastructure and other services. Moreover, this shift has led to an improved economic and social status of rural women. As result, the SES of rural women has increased, but not equally. The SES improvement of rural women is different between ALA projects. When ALA took place for city expansion purposes, the SES of women significantly improved. The indirect benefits of ALA for this purpose supported women in quickly finding new jobs with higher incomes. Their new working environment gave them opportunities to improve their social knowledge and vocational skills. Many women have become the main income generator, have better occupations, and have gained more social knowledge and vocational skills. Vice versa, in Zone 2 and especially in Zone 3, the SES improvement is still slow because ALA for industrial development and hydropower dam construction does not create many new job opportunities that are suitable for the skills of women. Hence, some of them still face unemployment, and many of them have to accept unstable jobs. In general, direct and indirect impacts of ALA have significantly contributed to SES improvements; however, they are not yet sustainable and are not equal among the different zones.

This study also shows that rural women are not yet satisfied with the compensation and support policy. The responsibilities of stakeholders, especially of investors, are few and unclear. The support and influence on SES of rural women from investors after ALA are very low and insignificant, although they are main beneficiaries of ALA. This situation is quite similar in three zones even though the ALA period at each zone is different. Moreover, ALA for different non-agricultural purposes caused differential job opportunities, leading to different impacts on the SES of women. Support policies of ALA projects, especially vocational support policies, were only seminally applied. All these problems lead to inequality for affected women.

This paper strongly recommends that the support policy for women be flexible, not only in terms of payments but also action. First, ALA projects should cooperate with rural research organizations or social development researchers to study the social and economic consequences for laborers and women, including both direct and indirect benefits. The ALA projects also need to cooperate with stakeholders such as the Center of Support and Vocational Training for Farmers, the Center of Agricultural Consultancy and Support, the Agricultural Extension Center, the Industrial Extension Center, the Women’s Union, local or regional companies, enterprises and the affected women to build and implement a concrete support plan for women, such as providing vocational training courses, occupational consultancy, connection with employers, and supporting financial capital. This step should come first and should be well planned before starting ALA to ensure that women are able to find an alternative job. Finally, in the first years after ALA, the SES of women should be surveyed to provide more support to women who have not found an alternative job or whose job is not stable. Certainly, all steps of this support model need to be explicitly and equally discussed among stakeholders. The investor needs to take responsibility for the implementation of this support model until success is achieved. These recommendations can be combined with other support programs from the Government and Women’s Union to achieve the best results.