Theories of Land Reform and Their Impact on Land Reform Success in Southern Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Definitions

1.1.1. African Customary Law

1.1.2. Customary Land Tenure

- 1)

- Land rights are socially embedded, overlapping, and nested. They mirror the social and cultural values of the community and gain legitimacy from the trust a community places in the institutions governing the system.

- 2)

- Rights are derived from accepted membership of a social unit (kinship ties), either through birth or acquired allegiance.

- 3)

- They allow multiple uses (e.g., farming, fishing, occupation) and users (e.g., farmers, migrants, herders, residents) of resources.

- 4)

- Rights are both individual (the holding) and communal (the commons).

- 5)

- They are dynamic and evolve in response to external or internal change. Boundaries are flexible and negotiable.

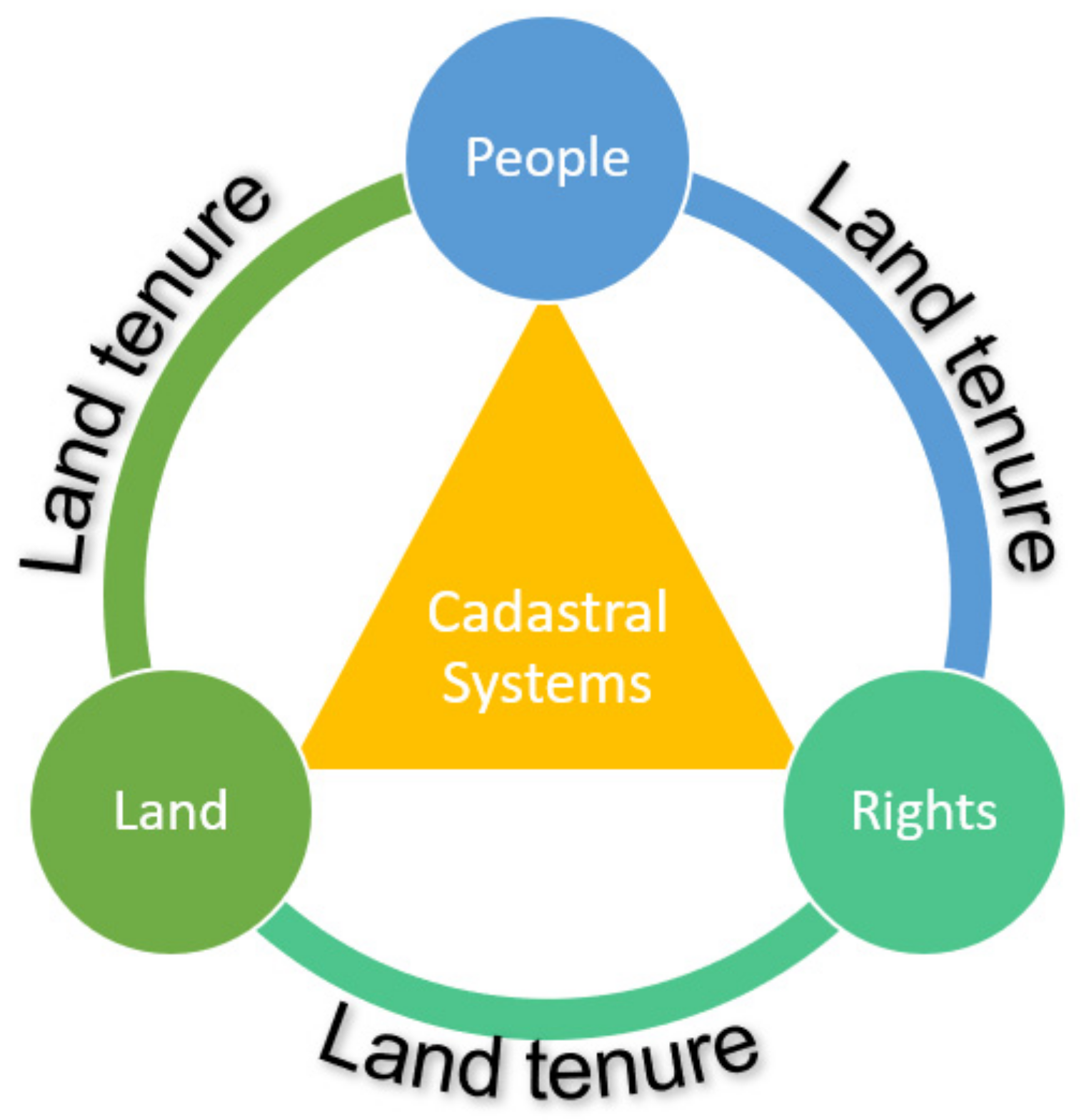

1.1.3. Cadastral Systems Development

1.2. Aim

2. Typology of Theories

2.1. Overview: Replacement or Conservation

- With the focus of customary tenure systems being on group rights, the tenure of individuals is insecure.

- Because customary rights are inalienable, they do not promote investment and thus hinder development.

- Common property related to customary systems is archaic and likely to disappear in the future as tenure evolves towards individualisation.

2.2. Conservative Theory

2.3. Democratic Adaptation Theory

- respecting existing land rights that are legitimate in African customary law;

- providing clarity on what these existing rights are—the ‘arrangement’ vs. the ‘form’ of tenure [49]—in so far as these are recognised in African customary law; and

- providing land tenure security where customary tenure systems are weak.

2.4. Hybrid Adaptation Theory

2.5. Incremental Approaches

2.6. Evolutionary Replacement Theory

2.7. Collective Replacement Theory

- 1)

- Equitable distribution of resources;

- 2)

- Democratization of traditional and community leadership;

- 3)

- Increased development and improved land productivity;

- 4)

- Focus on self-reliance; and

- 5)

- Efficient distribution of services such as water, electricity, education, and health.

2.8. Systematic Titling

- The formalisation process is costly, and the result is increased land values that are inaccessible to vulnerable groups and consequently not pro-poor.

- Land markets emphasise inequality in land distribution.

- Formalisation may create opportunity for abuse, opportunism, and the destruction of established local systems if government institutions are weak.

- The ‘poor’, who are the intended beneficiaries of formalisation, are not a homogenous group.

- The formalisation model does not recognise the complexity of overlapping customary rights.

- There is little evidence to support the hypothesis that formalisation will lead to improved credit access in African countries.

2.9. Summary

3. Data Collection and Analysis

3.1. Data Collection

- 1)

- The ‘top-down’ group of people involved in cadastral systems development and land administration activities, representing the relevant state department or agency responsible for land administration.

- 2)

- The ‘bottom-up’ people who are the customary land rights-holders due to benefit from development.

- 3)

- The traditional leaders responsible for administering land in customary areas.

- 4)

- The observers (South African case only): academics and members of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) who are not involved in development but who are witnesses to the process of development and its effects.

3.2. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Nigeria

4.1.1. Justification for Development

4.1.2. Belonging

4.1.3. Gap Analysis

4.1.4. Measures of Success

4.1.5. Summary

4.2. Mozambique

4.2.1. Justification for Development

4.2.2. Belonging

- 1)

- Occupation of land by a community governed under African customary law;

- 2)

- Occupation of land for an uninterrupted period of 10 years as if the occupier were the owner;

- 3)

- Allocation of a 50-year lease by the State to a private investor, after consultation with the affected local community.

4.2.3. Gap Analysis

4.2.4. Measures of Success

4.2.5. Summary

4.3. South Africa

4.3.1. Justification for Development

4.3.2. Belonging

“We are owned by the land, we belong to it, not that it belongs to us. That is the African way. ... We are the custodians of the land for those who are still in our loins.”

“When I go to [my tribal home], … I belong to that place. It’s me belonging to that place, as part of it… Land connects people in posterity and to the future. Generations to come, people conceptualize property as belonging.”

“Look at restitution. It gives me the land back that my great grandfather lost many years ago. When I’m staying in East London, I don’t want to be a farmer… [It makes no sense] to give me [land], on the basis of the fact that I have a right because my great grandfather lost [land]. ... You end up restituting to me something I never had. Giving me ownership when I never had ownership. It creates problems because people who don’t want to own become owners because you only have the ‘straight jacket’ of titles as your system.”

4.3.3. Gap Analysis

4.3.4. Measures of Success

4.3.5. Summary

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Borras, S.; Franco, J.C. Contemporary Discourses and Contestations around Pro-Poor Land Policies and Land Governance. J. Agrar. Chang. 2010, 10, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, S.; Whittal, J. Towards a framework for assessing the impact of cadastral development on land rights-holders. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2016: Recovery from Disaster, Christchurch, New Zealand, 2–6 May 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Burns, A.; Grant, C.; Nettle, K.; Brits, A.; Dalrymple, K. Land Administration Reform: Indicators of Success, Future Challenges; Land Equity International: Wollongong, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zevenbergen, J.; Augustinus, C.; Antonio, D.; Bennett, R. Pro-poor land administration: Principles for recording the land rights of the underrepresented. Land Use Policy 2013, 31, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuholt, B.; Wahid, F.; Sæbø, Ø. Land Information Systems for Development (LIS4D): A Neglected Area within ICT4D Research? In Proceedings of the 48th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Kauai, HI, USA, 5–8 January 2015; pp. 2158–2167. [Google Scholar]

- Akrofi, E.O.; Whittal, J. Compulsory Acquisition and Urban Land Delivery in Customary Areas in Ghana. South African J. Geomatics 2013, 2, 280–295. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, M.; Danso, E.K. Tenure security, land registration and customary tenure in a peri-urban Accra community. Land use policy 2014, 39, 358–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enemark, S.; McLaren, R.; Lemmen, C. Fit-For-Purpose Land Administration Guiding Principles; Global Land Tool Network (GLTN): Copenhagen, Denmark, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Diala, A.C. The concept of living customary law: A critique. J. Leg. Plur. Unoff. Law 2017, 49, 143–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, T.W. “Official” vs “living” customary law: Dilemmas of description and recognition. In Land, Power & Custom: Controversies generated by South Africa’s Communal Land Rights Act; Claasens, A., Cousins, B., Eds.; UCT Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2008; pp. 138–153. [Google Scholar]

- Cotula, L. Introduction. In Changes in “customary” land tenure systems in Africa; Cotula, L., Ed.; International Institute for Environment and Development: Stevenage, UK, 2007; pp. 5–14. ISBN 978-1-84369-657-5. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, T.; Hornby, D. The Realities of Tenure Diversity in South Africa. In Proceedings of the ‘At the Frontier of Land Issues: Social Embeddedness of Rights and Public Policy, Montpellier, France, 16–19 May 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, F. The ascertainment of living customary law: An analysis of the South African Constitutional Court’s jurisprudence. J. Leg. Plur. Unoff. Law 2019, 51, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautenbach, C. Oral Law in Litigation in South Africa: An Evidential Nightmare? Potchefstroom Electron. Law J./Potchefstroomse Elektron. Regsbl. 2017, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, M.; Sibanda, S.; Turner, S. Land tenure reform and rural livelihoods in southern Africa. Nat. Resour. Perspect. 1999, Volume February, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Land tenure and rural development; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2002; ISBN 9251048460. [Google Scholar]

- Enemark, S. Understanding the Land Management Paradigm. In Proceedings of the FIG Commission 7 Symposium on Innovative Technologies for Land Administration, Madison, WI, USA, 19–25 January 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cousins, B. Contextualising the controversies: Dilemmas of communal tenure reform in post-apartheid South Africa. In Land, Power & Custom: Controversies generated by South Africa’s Communal Land Rights Act; Claasens, A., Cousins, B., Eds.; UCT Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2008; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Chanock, M. The Making of South African Legal Culture, 1902–1936: Fear, Favour and Prejudice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; ISBN 0521791561. [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne Delville, P. Registering and administering customary land rights: Can we deal with complexity? In Innovations in Land Rights Recognition, Administration, and Governance; Deininger, K., Augustinus, C., Enemark, S., Munro-Faure, P., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; pp. 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Banda, J.L. Romancing Customary Tenure: Challenges and prospects for the neo-liberal suitor. In The Future of African Customary Law; Fenrich, J., Galizzi, P., Higgins, T.E., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 312–335. [Google Scholar]

- Chitonge, H.; Mfune, O.; Umar, B.B.; Kajoba, G.M.; Banda, D.; Ntsebeza, L. Silent privatisation of customary land in Zambia: Opportunities for a few, challenges for many. Soc. Dyn. 2017, 43, 82–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoth-Ogendo, H.W.O. The Tragic African Commons: A Century of Expropriation, Suppression and Subversion; Land reform and agrarian change in southern Africa, Occasional paper series; University of the Western Cape: Cape Town, South Africa, 2002; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Rugege, S. Land Reform in South Africa: An Overview. Int. J. Leg. Info 2004, 283, 283–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cousins, B.; Cousins, T.; Hornby, D.; Kingwill, R.; Royston, L.; Smit, W. Will formalising property rights reduce poverty in South Africa’s ‘second economy’? PLAAS Policy Br. 2005, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberger, M.; Bruce, J.; Mawalma, B.; de Wit, P.; Boudreaux, K. The Future of Customary Tenure: Options for policymakers. Available online: http://www.land-links.org/issue-brief/the-future-of-customary-tenure/ (accessed on 20 October 2016).

- Cousins, B. More Than Socially Embedded: The Distinctive Character of “Communal Tenure” Regimes in South Africa and its Implications for Land Policy. J. Agrar. Chang. 2007, 7, 281–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, S. No Condition is Permanent – The Social Dynamics of Agrarian Change in Sub-Saharan Africa; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, R. Statutory Recognition of Customary Land Rights in Africa: An Investigation into Best Practices for Lawmaking and Implementation; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cotula, L.; Toulmin, C.; Hesse, C. Land Tenure and Resource Access in Africa: Lessons of Experience and Emerging Issues; International Institute for Environment and Development: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- FIG FIG Statement on the Cadastre. Available online: http://www.fig.net/commission7/reports/cadastre/statement_on_cadastre.html (accessed on 26 March 2013).

- Silva, M.A.; Stubkjær, E. A review of methodologies used in research on cadastral development. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2002, 26, 403–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J. Rights, Responsibilities, Restrictions (RRRs). Available online: http://www.csdila.unimelb.edu.au/people/PeopleFiles/JudeWallace/Registrars_Presentation_4.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Lemmen, C.; van Oosterom, P.; van der Molen, P. Land Administration Domain Model. GIM Int. 2013, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackman-Antwi, R.; Bennett, R.M.; de Vries, W.; Lemmen, C.H.J.; Meijer, C. The point cadastre requirement revisited. Surv. Rev. 2013, 45, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, W.T.; Bennett, R.M.; Zevenbergen, J.A. Neo-cadastres: Innovative solution for land users without state based land rights, or just reflections of institutional isomorphism? Surv. Rev. 2015, 47, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, R.; Hornby, D. Traditional Land Matters—A Look into Land Administration in Tribal Areas in KwaZulu-Natal. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267260749%0ATraditional (accessed on 18 May 2017).

- Whittal, J. A New Conceptual Model for the Continuum of Land Rights. South African J. Geomatics 2014, 3, 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Alden Wily, L. Land tenure reform and the balance of power in eastern and southern Africa. ODI Nat. Resour. Perspect. 2000, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Royston, L. In the meantime... Moving towards secure tenure by recognising local practice. In Trading Places: Accessing land in African Cities; Napier, M., Berrisford, S., Kihato, C.W., McGaffin, R., Royston, L., Eds.; African Minds: Somerset West, South Africa, 2013; pp. 47–72. ISBN 978-1-920489-99-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, J. The Variety of Reform: A Review of Recent Experience with Land Reform and the Reform of Land Tenure, with Particular Reference to the African Experience. In Institutional Issues in Natural Resource Management; Marcussen, H.S., Ed.; International Development Studies: Roskilde, Denmark, 1993; Volume 9, pp. 13–56. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, M.; Augustinus, C. Framework for Evaluating Continuum of Land Rights Scenarios; UN-HABITAT: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016; ISBN 9789211327137. [Google Scholar]

- Arko-Adjei, A. Adapting land administration to the institutional framework of customary tenure: The case of peri-urban Ghana. Ph.D. Thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Platteau, J. The evolutionary theory of land rights as applied to sub-Saharan Africa: A critical assessment. Dev. Change 1996, 27, 29–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Soto, H. The Mystery of Capital: Why Capitalism Triumphs in the West and Fails Everywhere Else; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nkwae, B. Conceptual Framework For Modelling and Analysing Periurban Land Problems in Southern Africa. Ph.D. Thesis, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, NB, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiff, E. ‘Willing buyer, willing seller’: South Africa’s failed experiment in market-led agrarian reform. Third World Q. 2007, 28, 1577–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, J. Do Indigenous Tenure Systems Constrain Agricultural Development? In Land in African Agrarian Systems; Basset, T., Crummey, D., Eds.; The University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1993; pp. 35–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hornby, D.; Royston, L.; Kingwill, R.; Cousins, B. Introduction: Tenure practices, concepts and theories in South Africa. In Untitled: Securing Land Tenure in Urban and Rural South Africa; Hornby, D., Kingwill, R., Royston, L., Cousins, B., Eds.; University of KwaZulu-Natal Press: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2017; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Delius, P. Contested terrian: Land rights and chiefly power in historical perspective. In Land, Power & Custom: Controversies Generated by South Africa’s Communal Land Rights Act; Claassens, A., Cousins, B., Eds.; UCT Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2008; pp. 211–237. [Google Scholar]

- Chanock, M. Paradigms, Policies and Property: A review of the customary law of land tenure. In Law in Colonial Africa; Mann, K., Roberts, R., Eds.; Heinemann Educational Books, Inc.: Portsmouth, UK, 1991; ISBN 0-85255-602-0. [Google Scholar]

- Claassens, A. Power, accountability and apartheid borders: The impact of recent laws on struggles over land rights. In Land, Power & Custom: Controversies Generated by South Africa’s Communal Land Rights Act; Claassens, A., Cousins, B., Eds.; UCT Press: Cape Town, South Africa, 2008; pp. 262–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ubink, J.M.; Quan, J.F. How to combine tradition and modernity? Regulating customary land management in Ghana. Land use policy 2008, 25, 198–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingwill, R.; Hornby, D.; Royston, L.; Cousins, B. Conclusion—Beyond “the Edifice”. In Untitled: Securing Land Tenure in Urban and Rural South Africa2; Hornby, D., Kingwill, R., Royston, L., Cousins, B., Eds.; University of KwaZulu-Natal Press: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2017; pp. 388–430. [Google Scholar]

- DLA White paper on South African land policy; Department of Land Affairs (DLA): Pretoria, South Africa, 1997.

- Royston, L.; Abrahams, G.; Hornby, D.; Mtshiyo, L. Informal Settlement Upgrading: Incrementally upgrading Tenure under Customary Administration; Housing Development Agency: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Royston, L. “Entanglement”—A case study of changing tenure and social relations in inner-city buildings in Johannesburg. In Untitled: Securing Land Tenure in Urban and Rural South Africa; Hornby, D., Kingwill, R., Royston, L., Cousins, B., Eds.; University of KwaZulu-Natal Press: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2017; pp. 196–234. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, J.; Migot-Adholla, S.; Atherton, J. The findings and their policy Implications: Institutional adaptation or replacement. In Searching for Land Tenure Security in Africa; Bruce, J., Migot-Adholla, S., Eds.; Kendall/Hunt: Washington, DC, USA, 1994; pp. 251–265. [Google Scholar]

- Kingwill, R. Lost in translation: Family title in Fingo village, Grahamstown, Eastern Cape. Acta Juridica Plur. Dev. Stud. Access Prop. Africa 2011, 2011, 210–237. [Google Scholar]

- Augustinus, C.; Lemmen, C.; van Oosterom, P. Social tenure domain model: Requirements from the perspective of pro-poor land management. In Proceedings of the Proceeding of the 5th FIG Regional Conference; International Federation of Surveyors, Accra, Ghana, 8–11 March 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmen, C. The Social Tenure Domain Model: A Pro-Poor Land Tool; International Federation of Surveyors: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- UN-HABITAT; IIRR; GLTN. Handling Land: Tools for Land Governance and Secure Tenure; UN-HABITAT, GLTN, IIRR: Nairobi, Kenya, 2012; ISBN 9789211324389. [Google Scholar]

- Platteau, J. Does Africa need land reform? In Evolving Land Rights, Policy and Tenure in Africa; Toulmin, C., Quan, J., Eds.; DFID/IIED/NRI: London, UK, 2000; pp. 51–73. [Google Scholar]

- van der Molen, P. The Future Cadastres – Cadastres after 2014. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2003; International Federation of Surveyors, Paris, France, 13–17 April 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, R.; Rajabifard, A.; Kalantari, M.; Wallace, J.; Williamson, I. Cadastral futures: Building a new vision for the nature and role of cadastres. In Proceedings of the FIG Congress 2010: Facing the Challenges—Building the Capacity, Sydney, Australia, 11–16 April 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.; Land, N. Cadastre 2.0 – A technology vision for the cadastre of the future. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2012, Rome, Italy, 6–10 May 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Akrofi, E.O. Assessing Customary Land Administration Systems for Peri-Urban Land in Ghana. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Feder, G.; Nishio, A. The benefits of land registration and titling: Economic and social perspectives. Land Use Policy 1999, 15, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M. Somalia Land Policies and Tenure Impacts: The case of the Lower Shebelle. In Land in African Agrarian Systems; Bassett, T., Crummey, D., Eds.; University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1993; pp. 298–325. [Google Scholar]

- Okoth-Ogendo, H.W.O. Agrarian Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa: An assessment of state responses to the African agrarian crisis and their implications for agricutural development. In Land in African Agrarian Systems; Bassett, T.J., Crummey, D.E., Eds.; The University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, USA, 1993; pp. 247–273. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiff, E. Land Reform in South Africa: A Status Report 2008; Research Report; Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies (PLAAS): Cape Town, South Africa, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Unruh, J.D. Land Tenure Conflict Resolution in Mozambique: The Role of Conflict Resolution in Land Policy Reform; LTC Land Conflict Study: Madison, WI, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Unruh, J.D. Postwar land dispute resolution: Land tenure and the peace process in Mozambique. Int. J. World Peace 2001, 18, 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- de Quadros, M.C. Current land policy issues in Mozambique. L. Reform, L. Settl. Coop. 2003, 3, 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, M.; Roux, L. A change based framework for theory building in land tenure information systems. Surv. Rev. 2012, 44, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith-Charles, C. The Impact of Land Titling on Land Transaction Activity and Registration System Sustainability. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Florida, Florida, FL, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Steudler, D.; Törhönen, M.-P.; Pieper, G. FLOSS in Cadastre and Land Registration: Opportunities and Risks; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO) and the International Federation of Surveyors (FIG): Rome, Italy, 2010; ISBN 9789251065105. [Google Scholar]

- Conning, J.; Deb, P. Impact Evaluation for Land Property Rights Reforms; Hunter College and The Graduate Centre, City University of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Goyal, A. Going digital: Credit effects of land registry computerization in India. J. Dev. Econ. 2012, 99, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J. Land tenure, economic growth and poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Evolving Land Rights, Policy and Tenure in Africa; Toulmin, C., Quan, J., Eds.; DFID/IIED/NRI: London, UK, 2000; pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mubangizi, J.; Kaya, H. African Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Human Rights: Implications for Higher Education, Based on the South African Experience. Int. J. African Renaiss. Stud. Multi Inter Transdiscipl. 2015, 10, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalola, K.H.; Hull, S.A. Using the New Continuum of Land Rights Model to Measure Tenure Security: A case study of Itaji-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria. South Afr. J. Geomatics 2019, 8, 84–97. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; SAGE Publications Ltd: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Shenton, A.K. Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Educ. Inf. 2004, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, J.A. From Grounded Theory to Grounded Theorizing in Qualitative Research. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Business and Management Research Methods; Cassell, C., Cunliffe, A., Grandy, G., Eds.; SAGE Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2017; pp. 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, G. A critique of using grounded theory as a research method. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 2, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Holton, J. Remodeling Grounded Theory. Hist. Soc. Res. Suppl. 2007, 47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Guba, E.G. ERIC/ECTJ Annual Review Paper: Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Educ. Commun. Technol. 1981, 29, 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Woods, M.; Paulus, T.; Atkins, D.P.; Macklin, R. Advancing Qualitative Research Using Qualitative Data Analysis Software (QDAS)? Reviewing Potential Versus Practice in Published Studies using ATLAS.ti and NVivo, 1994-2013. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2016, 34, 597–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friese, S. Qualitative Data Analysis with ATLAS.ti, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-44628-204-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bringer, J.D.; Johnston, L.H.; Brackenridge, C.H. Using Computer-Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software to Develop a Grounded Theory Project. Field Methods 2006, 18, 245–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, S.; Whittal, J. Human rights in tension: Guiding cadastral systems development in customary land rights contexts. Surv. Rev. 2019, 51, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.; Clarke, M.; Baxter, J. Evaluating land administration projects in developing countries. Land Use Policy 2008, 25, 464–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith-Charles, C.; Sutherland, M. Analysing the costs and benefits of 3D cadastres with reference to Trinidad and Tobago. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2013, 40, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Asperen, P. Evaluation of Innovative Land Tools in Sub-Saharan Africa: Three Cases from a Peri-Urban Context; Doctoral dissertation, Delft University of Technology: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; ISBN 9781614994435. [Google Scholar]

- Durand-Lasserve, A.; Selod, H. The formalisation of urban land tenure in developing countries. In Proceedings of the The World Bank’s Urban Research Symposium, Washington, DC, USA, 14–16 May 2007; pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Shipton, P. Mortgaging the Ancestors. Ideologies of Attachment in Africa; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Deininger, K.; Hilhorst, T.; Songwe, V. Identifying and addressing land governance constraints to support intensification and land market operation: Evidence from 10 African countries. Food Policy 2014, 48, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghebru, H.; Edeh, H.; Ali, D.; Deininger, K.; Okumo, A.; Woldeyohannes, S. Tenure Security and Demand for Land Tenure Regularization in Nigeria Empirical Evidence from Ondo and Kano States; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ghebru, H.; Okumo, A. Land Administration Service Delivery and Its Challenges in Nigeria: A Case Sstudy of Eight States; NSSP working paper; International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abugu, U. Land Use and Reform in Nigeria: Law and Practice, 1st ed.; Immaculate Prints: Abuja, Nigeria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maduekwe, N.C. The Land Tenure System Under the Customary Law. In Proceedings of the Nigerian Institute Of Advanced Legal Studies Training Programme For Judges Of The Customary Courts And Area Courts, Abuja, Nigeria, 13 May 2014; p. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Babalola, S.O.; Rahman, A.A.; Choon, L.T.; van Oosterom, P.J.M. POSSIBILITIES OF LAND ADMINISTRATION DOMAIN MODEL (LADM) IMPLEMENTATION IN NIGERIA. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, II, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amokaye, O.G. The impact of the Land Use Act upon land rights in Nigeria. In LOCAL CASE STUDIES IN AFRICAN LAND LAW; Home, R., Ed.; Pretoria University Law Press: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011; pp. 59–78. ISBN 978-1-920538-01-9. [Google Scholar]

- Otubu, A.K. The Land Use Act and Land Ownership Debate in Nigeria: Resolving the Impasse. SSRN Electron. J. 2015. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2564539 (accessed on 10 November 2019).

- OTUBU, A. Private Property Rights and Compulsory Acquisition Process in Nigeria: The Past, Present and Future. Eur. Int. Law 2012, 8, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Otubu, A. THE LAND USE ACT AND LAND ADMINISTRATION IN 21ST CENTURY NIGERIA: NEED FOR REFORMS. J. Sustain. Dev. Law Policy 2018, 9, 81–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuhu, M.B.; Aliyu, A.U. Compulsory Acquisition of Communal Land and Compensation Issues: The Case of Minna Metropolis. In Proceedings of the FIG Working Week 2009, Eilat, Israel, 3–8 May 2009; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, I.O. Practical Approach to Law of Real Property in Nigeria; Ecowatch Publications: Lagos, Nigeria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Otubu, A.K. Compulsory Acquisition Without Compensation and the Land Use Act. SSRN Electron. J. 2014. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2420039 (accessed on 10 November 2019).

- Mabogunje, A.L. Land Reform In Nigeria: Progress, Problems & Prospects. In Proceedings of the Annual Conference on Land Policy and Administration, Washington, DC, USA, 26–27 April; 2010; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Matfess, H. Institutionalizing instability: The constitutional roots of insecurity in nigeria’s fourth republic. Stab. Int. J. Secur. Dev. 2016, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British Council Nigeria. Gender in Nigeria Report 2012: Improving the lives of girls and women in Nigeria, 2nd ed.; British Council: Abuja, Nigeria, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Norwegian Refugee Council Unsettlement: Urban Displacement in the 21st Century; Norwegian Refugee Council: Oslo, Norway, 2018.

- Amaza, M. A former Boko Haram stronghold is now one of Nigeria’s fastest growing property markets. Available online: https://qz.com/africa/688038/a-former-boko-haram-stronghold-is-now-one-of-nigerias-fastest-growing-property-markets/ (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Iyorah, F. As north-east Nigeria battles Boko Haram’s insurgency, the city of Maiduguri is experiencing a construction boom. Available online: https://www.equaltimes.org/as-north-east-nigeria-battles-boko?lang=en#.Xbhtq-gzYdU (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Babagana, M.; Ismail, M.; Mohammed, B.G.; Dilala, M.A.; Hussaini, I.; Zangoma, I.M. Impacts of Boko Haram Insurgency on Agricultural Activities in Gujba Local Government Area, Yobe State, Nigeria. Int. J. Contemp. Res. Rev. 2018, 9, 20268–20282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO Northeast Nigeria Situation Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2016.

- Wilson Myers, G. Land and Power: The impact of the Land Use Act in southwest Nigeria; LTC Research Paper; Land Tenure Center: Madison, WI, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Babalola, K. Measuring Tenure Security of the Rural Poor using pro-poor land tools: A case study of Itaji-Ekiti, Ekiti State, Nigeria. University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, J. Pro-poor policy reforms and governance in state/public lands: A critical civil society perspective. L. Reform L. Settl. Coop. 2009, 1, 8–18. [Google Scholar]

- Nwocha, M.E. Impact of the Nigerian Land Use Act on Economic Development in the Country. Acta Univ. Danubius. Adm. 2016, 8, 117–128. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Doing Business: Equal Opportunity for All Doing Business; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nwuba, C.C.; Nuhu, S.R. Challenges to Land Registration in Kaduna State, Nigeria. African Real Estate 2018, 3, 141–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbolahan, B.; Adegoke, J.; Aderibigbe, A. Factors influencing land title registration practice in Osun State. Int. J. Law Built Environ. 2017, 9, 240–255. [Google Scholar]

- Atilola, O. Land Administration Reform Nigerian: Issues and Prospects. In Proceedings of the FIG Congress 2010: Facing the Challenges—Building the Capacity, Sydney, Australia, 11–16 April 2010; 2010; p. 16. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Brink, R. Land Reform in Mozambique; Agriculture and Rural Development Notes: Land policy and administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Volume December. [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, C. Law-Making in an African context: The 1997 Mozambican land law; Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO): Maputo, Mozambique, 2002; Volume March. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, G.W. Competitive Rights, Competitive Claims: Land Access in Post-War Mozambique. J. South. Afr. Stud. 1994, 20, 603–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloeck-Jenson, S. Mozambique Country Profile. In Country Profiles of Land Tenure: Africa, 1996; Bruce, J., Ed.; Land Tenure Centre, University of Wisconsin-Madison: Madison, WI, USA, 1998; pp. 238–246. [Google Scholar]

- Norfolk, S.; Bechtel, P. Land Delimitation & Demarcation: Preparing communities for investment; TerraFirma Rural Development Consultants: Maputo, Mozambique, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- UN-HABITAT. Land Tenure, Housing Rights and Gender in Mozambique; Rosenberg, G., Ed.; UN-HABITAT: Nairobi, Kenya, 2005; ISBN 9211317711. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Mozambique A Política Nacional de Terras e Estrategia para a sua Implementação; Council of Ministers: Maputo, Mozambique, 1995.

- Monteiro, J.; Salomão, A.; Quan, J. Improving land administration in Mozambique: A participatory approach to improve monitoring and supervision of land use rights through community land delimitation. In Proceedings of the 2014 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington, DC, USA, 23–27 March 2014; p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber, L. Putting rural communities on the map: Land registration in Mozambique, 2007–2016. Available online: https://successfulsocieties.princeton.edu/publications/putting-rural-communities-map-land-registration-mozambique (accessed on 23 January 2018).

- EDG. Evaluation of the Mozambique Community Land Use Fund—Final Report; Effective Development Group, GRM International, The QED Group: Maputo, Mozambique, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Balas, M.; Murta, J.; Matlava, L.; Marques, M.R.; Joaquim, S.P.; Carrilho, J.; Lemmen, C. A Fit-For-Purpose Land Cadastre in Mozambique. In Proceedings of the 2017 World Bank Conference on Land and Poverty, Washington, DC, USA, 20–24 March 2017; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. Mozambique Land Administration Project (Terra Segura) (P164551). Available online: http://projects.worldbank.org/P164551?lang=en (accessed on 10 Febuary 2018).

- Mahlati, V. Final Report of the Presidential Advisory Panel on Land Reform and Agriculture; Presidential Advisory Panel on Land Reform and Agriculture: Pretoria, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DRDLR. Communal Land Tenure Policy (CLTP); Department of Rural Development and Land Reform: Stellenbosch, South Africa, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Planning Commission National Development Plan 2030 Our Future—Make It Work; National Planning Commission: Pretoria, South Africa, 2012; ISBN 9780621411805.

- Cousins, B. Land reform in South Africa is sinking. Can it be saved? Available online: https://www.nelsonmandela.org/uploads/files/Land__law_and_leadership_-_paper_2.pdf (accessed on 2 Febuary 2017).

- Cousins, B. Why title deeds aren’t the solution to South Africa’s land tenure problem. Available online: https://theconversation.com/why-title-deeds-arent-the-solution-to-south-africas-land-tenure-problem-82098 (accessed on 15 August 2017).

- Centre for Law and Society. Communal Land Tenure Policy and IPILRA; Centre for Law and Society: University of Cape Town: Cape Town, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- de Satgé, R.; Cartwright, K.; Kingwill, R.; Royston, L. The role of land tenure and governance in reproducing and transforming spatial inequality. Available online: https://www.parliament.gov.za/storage/app/media/Pages/2017/october/High_Level_Panel/Commissioned_Report_land/Commissioned_Report_on_Spatial_Inequality.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- Kingwill, R. Square Pegs in Round Holes: The competing faces of land title. In Untitled: Securing Land Tenure in Urban and Rural South Africa; Hornby, D., Kingwill, R., Royston, L., Cousins, B., Eds.; University of KwaZulu-Natal Press: Pietermaritzburg, South Africa, 2017; pp. 235–282. [Google Scholar]

- Eglin, R. A NEW LAND RECORDS SYSTEM. Available online: http://afesis.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/A-new-land-Records-System-Learning-Brief-8_final.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2017).

- Groenewald, A.J. South Africa’s Land Reform Programme. St. Mary’s Law Rev. Minor. Issues 2003, 5, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Williams-Wynn, C. Land rights: What people want, PositionIT, January/February 2017. Available online: www.ee.co.za/article/land-rights-people-want.html (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- Clark, M.; Luwaya, N. Communal Land Tenure 1994–2017. Available online: https://www.parliament.gov.za/storage/app/media/Pages/2017/october/High_Level_Panel/Commissioned_Report_land/Commisioned_Report_on_Tenure_Reform_LARC.pdf (accessed on 21 January 2019).

- Weinberg, T. Rural Status Report 3: The contested status of ‘communal land tenure’ in South Africa; Sparg, L., Ed.; Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies: Cape Town, Soth Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- DRDLR Green Paper on Land Reform; Department of Rural Development and Land Reform: Pretoria, South Africa, 2011.

- Statistics South Africa The South African MPI: Creating a Multidimensional Poverty Index Using Census Data; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2014.

- High Level Panel Report of the High Level Panel on the Assessment of Key Legislation and the Acceleration of Fundamental Change. Available online: https://www.parliament.gov.za/storage/app/media/Pages/2017/october/High_Level_Panel/HLP_Report/HLP_report.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2018).

| Cadastral System | Registered Freehold | Unregistered, Customary |

|---|---|---|

| People | Natural and juristic persons (e.g., individuals, companies, trusts) | Recognized members of a customary community governed according to African customary law. |

| Land | Parcels precisely defined by land surveyors following legislated standards of accuracy (e.g., the South African Land Survey Act 8 of 1997 and associated regulations). | Plots allocated according to custom [37] and demarcated following customary norms (e.g., building a cairn at the corners of the demarcated plot). Plots and boundaries may be flexible (variable over time). |

| Rights | Exclusive use, ownership, occupation, access, exclusion [38] as stipulated in the registered title or deed and as restricted by any relevant legislation. | Access, occupation, use, exclusion, rights and interests defined according to (official and/or living) African customary law [38] and recorded in the collective memories of the community or by some other means. |

| Theory | Possible Indicators |

|---|---|

| Conservative | Preservation of customary tenure Broadly African view of land Traditional leaders prominent in land administration |

| Democratic adaptation | Respecting and clarifying existing, legitimate land rights Improving gender equity, accountability and democracy Building on existing customary practices |

| Hybrid adaptation | Combination of statutory and customary arrangements Participatory approach: communities decide which rights are recorded |

| Incremental adaptation | Titles are a long-term objective Extra-legal, off-register practices recognised as legitimate Spontaneous titling according to need |

| Incremental replacement | Titles are the desired end state Customary tenure provides sufficient tenure security Legal recognition of customary tenure and adjudication practices |

| Evolutionary replacement | Land rights spontaneously evolve towards individualisation Titles are required for tenure security |

| Collective replacement | Nationalisation of all land/collective farming villages Equitable distribution of resources and services Democratisation of traditional leadership Improved productivity and self-reliance |

| Systematic titling | Titles are required for tenure security Titling leads to economic development Customary tenure must be replaced |

| Aspects | Elements |

|---|---|

| Understanding land in its social context | Justification for development |

| Belonging | |

| Goals for development | Gap analysis |

| Measures of Success |

| Understanding Land | Goals for Development | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theory | Justification for Development | Belonging | Gap Analysis | Measures of Success |

| Conservative | X | |||

| Democratic adaptation | X | X | ||

| Hybrid adaptation | X | X | ||

| Incremental adaptation | ||||

| Incremental replacement | ||||

| Evolutionary replacement | X | X | ||

| Collective replacement | X | |||

| Systematic titling | X | X | ||

| Understanding Land | Goals for Development | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theory | Justification for Development | Belonging | Gap Analysis | Measures of Success |

| Conservative | ||||

| Democratic adaptation | X | X | ||

| Hybrid adaptation | X | |||

| Incremental adaptation | X | |||

| Incremental replacement | X | X | X | |

| Evolutionary replacement | ||||

| Collective replacement | ||||

| Systematic titling | X | X | ||

| Understanding Land | Goals for Development | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theory | Justification for Development | Belonging | Gap Analysis | Measures of Success |

| Conservative | X | |||

| Democratic adaptation | X | |||

| Hybrid adaptation | X | |||

| Incremental adaptation | X | |||

| Incremental replacement | ||||

| Evolutionary replacement | ||||

| Collective replacement | ||||

| Systematic titling | X | X | X | X |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hull, S.; Babalola, K.; Whittal, J. Theories of Land Reform and Their Impact on Land Reform Success in Southern Africa. Land 2019, 8, 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8110172

Hull S, Babalola K, Whittal J. Theories of Land Reform and Their Impact on Land Reform Success in Southern Africa. Land. 2019; 8(11):172. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8110172

Chicago/Turabian StyleHull, Simon, Kehinde Babalola, and Jennifer Whittal. 2019. "Theories of Land Reform and Their Impact on Land Reform Success in Southern Africa" Land 8, no. 11: 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8110172

APA StyleHull, S., Babalola, K., & Whittal, J. (2019). Theories of Land Reform and Their Impact on Land Reform Success in Southern Africa. Land, 8(11), 172. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8110172