Abstract

We examine collaborations between the state and civil society in the context of land grabbing in Argentina. Land grabbing provokes many governance challenges, which generate new social arrangements. The incentives for, limitations to, and contradictions inherent in these collaborations are examined. We particularly explore how the collaborations between the provincial government of Santiago del Estero and non-government organizations (NGOs) played out. This province has experienced many land grabs, especially for agriculture and livestock production. In response to protest and political pressure, two provincial agencies were established to assist communities in relation to land tenure issues (at different stages). Even though many scholars consider state–civil society collaborations to be introduced by nation states only to gain and maintain political power, we show how rural communities are actually supported by these initiatives. By empowering rural populations, active NGOs can make a difference to how the negative implications of land grabbing are addressed. However, NGOs and government agencies are constrained by global forces, local political power plays, and stakeholder struggles.

1. Introduction

Social movements (as represented by non-government organizations; NGOs) and governments increasingly collaborate to jointly address social and environmental issues [1,2,3,4]. However, the ability of alliances between NGOs and governments to contribute to social equality has been questioned [4]. Many scholars of Latin America have analyzed these collaborations, especially in the context of progressive, popular, left-wing governments. According to these scholars, the ultimate goal of these collaborations is to gain and maintain electoral power and build legitimacy for their policies and practices [1,2,4]. Conversely, these collaborations potentially allow people who were previously excluded to have political voice [1]. These collaborations exist at the municipal and provincial levels, as well as at the national level [5,6,7].

This paper explores how land grabbing challenges existing policy regimes and provokes changes in governance arrangements. The incentives for, limitations to, and contradictions inherent in the collaborations between the state and NGOs are examined by focusing on land grabbing in Argentina. Land grabbing and the resultant conflict over access to land encourages various actors to interact, including individuals, social movements, NGOs, governments, and companies [4,8,9]. In Argentina and elsewhere, global demand for commodities trigger land grabbing, altering governance at all levels. By facilitating corporate entry, the state (represented at national, provincial, and municipal levels) plays a central role in land grabbing [4,10]. The state tends to represent economic market interest rather than community interest. Land grabbing threatens social justice, because access to the resources of local communities becomes restricted [6,11]. In Argentina, both formal and customary land tenure is recognized, creating a clash between investors and local communities. Many social movements protest against land grabbing and its effects [12,13]. The exacerbation of unequal land distribution resulting from the commodity export boom in Argentina was a factor in encouraging NGOs to form alliances with government and/or to publicly endorse government policies in the hope of improving the situation of rural people [2,4]. Given the diverse role of the state and the nature of the legal system, land grabbing in Argentina is taking place in a context of legal and institutional pluralism. This context creates a variety of challenges for the effectiveness of the collaboration between NGOs and the provincial government.

To understand these collaborations, we build on the concepts of ‘governance’ and ‘collaborative governance’ [14] in their various forms, including state-society-capital nexus [1], and policing [3]. Uitermark and Nicholls [3] (p. 975) define policing as the attempt by the state “to neutralize and pre-empt challenges to the legal and social order … and refers to the range of governmental technologies, rationalities and arrangements—partly centrally orchestrated, partly self-organized locally—developed to align subjects with the state.”

Governance is a concept that implies the presence of a diverse set of actors in the political and social arena [15,16]. In this paper, governance is defined as a system of regulation involving the interactions between and within a variety of actors across geographical scales, and includes the socio-institutional arrangements in which the actors participate [15,17]. The interactions between the various levels of government, civil society, and market actors leads to constant renegotiation, restructuring, and readjustment of their roles, responsibilities, and interests [16,17,18]. In theory, governance aims to empower people and create equal opportunities for people to participate in decision-making [16]. However, in practice, this does not always occur [16,19]. Local communities are often excluded from decision-making, or not given equal say. According to McKay [1], rather than empower local people, governance is sometimes considered to advance the agendas of companies and governments. Nevertheless, in certain situations, NGOs might be formally included in government structures. These collaborations may result in jointly addressing various social issues, for example programs for education, housing, public health, waste management, and environmental issues [6]. However, state–civil society collaboration can also imply a narrowing of the operational domain of NGOs due to the restrictions imposed by the government [3].

We consider the governance dynamics of state–civil society collaborations in the province of Santiago del Estero in Northern Argentina. For decades, there have been many major conflicts over the way agricultural expansion has played out in this province, including murders, death threats, physical harassment, and the burning of crops and houses [2,10,13,20,21]. After an alarming period of social unrest due to agricultural expansion and consequent political pressure by social movements, the provincial government established two agencies to assist rural communities to improve land tenure security and reduce land conflict [22]. These agencies are ‘El Registro de Poseedores’ (a registry of informal landholders) and ‘El Comité de Emergencia’ (the Emergency Committee), and are cooperations between the state and NGOs, including Movimiento Campesino de Santiago del Estero (MOCASE), the Peasant-Indigenous Movement of Santiago del Estero. The establishment of these agencies can be analyzed as being the result of left-wing Latin American governments granting decision-making power to civil society with the goal of avoiding further social conflict [1,2,9]. In the academic literature, the potential co-optation of NGOs within government structures is much debated [3,4]. It is therefore interesting to analyze the mechanisms and characteristics by which this takes place in the agricultural expansion in Argentina. As McKay [1] suggests, such collaborations pose questions like: Why do these collaborations arise?; how do these collaborations work?; and is society transformed for the betterment of rural communities by these collaborations? This paper offers a theoretical overview of the different perspectives on collaborative governance, specifically in the context of NGOs collaborating with the provincial government. This perspective has been under-studied to date, and therefore this focus brings an original contribution to the governance of land grabbing.

2. State–Civil Society Collaborations in Latin America and Argentina

In Latin America, collaborations between NGOs and governments started around the 1990s, when many Latin American countries were still developing as democracies [6]. After the fall of the military dictatorships in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, the engagement of civil society was seen as fundamental to building democracy and development [6,23,24]. Social movements and NGOs were severely repressed during the military dictatorships [6,8]. After the fall of these regimes, throughout the continent, provincial and municipal governments started to collaborate with NGOs to co-develop, implement, and shape social policy and social services. NGOs possessed the contacts with communities in need, which benefitted governments in implementing programs more easily. These collaborations were considered a means to democratize society and help alleviate poverty and other social and environmental issues that were neglected during the dictatorships [6]. The structural adjustment programs that had been adopted in the 1990s and the consequent austerity meant that essential public services had been run down, and were in poor quality and quantity [25]. The various crises in many Latin American countries also contributed to poor infrastructure, healthcare, education, and widespread poverty [23,25]. The state–civil society collaborations were useful, as municipal and provincial governments in Latin America were ill-equipped to address the issues and needs of local residents [6].

The collaboration between the national government and NGOs reached its peak during the so called ‘pink tide’ or ‘left turn’ in Latin America [4]. This period started with the presidency of Hugo Chávez in Venezuela in 1999 [5,8]. The support of, and alliances with, NGOs was crucial for the election of left-wing governments in Latin America [4,8]. The NGOs severely criticized the neoliberal policies of the earlier right-wing governments [4]. The new left-wing governments made electoral promises to NGOs to support them and to alleviate the impacts of the neoliberal policies that had been introduced. Their promises included land redistribution in favor of rural peasants and the introduction of various welfare programs [4,8]. However, scholars such as Vergara-Camus and Kay [4] state that no substantial change was experienced by rural people. Even though some advances were made, they questioned whether the NGOs adequately challenged governments. Some NGOs were criticized for losing sight of their original goals [8].

Lapegna [2] highlighted that, in Argentina, the governments of former Presidents, Néstor Kirchner (from 2003–2007) and Cristina Kirchner (from 2007–2015), sought collaborations with NGOs to ‘repoliticize’ society, meaning that they intended for social issues to be put back on the agenda and for people to become re-engaged politically. The collaborations with NGOs, for example with MOCASE, underpinned the government’s promise to change social structures and invest in rural development [2,8]. From 2003 on, including NGOs in government structures was promoted at the provincial and municipal levels [7,22,26]. However, the outcomes for rural people were less than expected [4]. One reason for this might be the passive nature of NGOs in Argentina [5]. Furthermore, it is debated whether these movements had a sufficiently strong organizational capacity to be able to adjust to the new situation [2,5]. Thus, the pink tide in Argentina had little impact [2,5]. Another reason that explains the limited achievement of social outcomes is the strong ties the Cristina Kirchner government had with the agro-industry, which led the country towards large-scale agricultural production at the expense of rural people [27].

In many cases, forming an alliance with or supporting the state might be the only real way for NGOs to influence policies [6,8]. However, collaboration with the state may lead to the disenfranchisement of social movements [8], although these collaborations can lead to building human capital, emancipation, empowerment, and/or the enhanced use of local knowledge [1,6]. However, governments are often afflicted by elite capture [4], which influences the success of these collaborations. In Argentina, the federal system means that lower levels of government have to implement the laws of the higher levels, and may be resource constrained, which means that they are not always able to implement their own policies or to implement federal policies effectively [6]. Thus, collaboration between the state and civil society is paradoxical.

3. An Analysis of State–Civil Society Collaborations

Land grabbing alters the interplay between actors [9]. The changes exacerbated by land grabbing can provoke processes in which it can become desirable for actors to initiate negotiated collaborations with previously less-obvious partners [17]. Ran and Qi [14] (p. 9) suggest that collaborative governance is a phenomenon “where diverse stakeholders from public, private, and civic sectors work together based on deliberative consensus and collective decision-making to achieve shared goals that could not be otherwise fulfilled individually.” Institutional arrangements adjust to political settings, such as the political pressure from social movements and NGOs. As a pragmatic step of government institutions to maintain or gain power, or to address a service deficit, they may actively seek to include NGOs in their activities [2,4,6]. However, this does not mean that these new partners are necessarily fighting for the same goals [1]. Below, we consider these collaborations from the state perspective and the NGO perspective.

3.1. The State’s Perspective to State–Civil Society Collaborations

Many state–civil society collaborations occur as a consequence of civil society pressuring governments in one way or another [8]. Because social movements can destabilize societal processes and challenge the credibility of the state [2], governments prefer to collaborate only with those NGOs that are not confrontational or that are only moderately critical of government policy [28]. State–civil society collaborations have become an important strategy for government, especially when social movements are a potential threat to the state. NGOs that are in alliance with the state are arguably more controllable. By collaborating with governments, it is more difficult for them to denounce government policies [3]. Sometimes, connecting with NGOs will lead to the state providing funding for activities that may flow from this collaboration. This might persuade NGOs to specialize on a narrow set of activities and/or reduce their use of confrontational tactics directed towards the government [3]. Other scholars argue that collaborations with NGOs are especially valuable when provincial or municipal governments lack resources, or where NGOs have better relationships with the groups of people they want to target [6].

Uitermark and Nicholls [3] considered that some strategies governments use to control NGOs are ‘temporal delimitation’ and ‘territorial encapsulation’. Temporal delimitation means that through collaboration, governments think they can delimit the scope and vision of the NGO to current and near future issues. By territorial encapsulation they mean that the NGO’s activities can be limited to a prescribed territory, zone, district, or region. These strategies help governments control the activities of the NGOs.

3.2. The Social Movement and NGO Perspective

In an attempt to pursue their agendas and push for change, NGOs use diverse strategies, including various forms of protest, as well collaborating with government [6,29]. Collaborations between the state and NGOs can be seen as a transformation from confrontation to collaboration. Uitermark and Nicholls [3] conceptualized this as being a shift from ‘politicizing’ to ‘policing’. By politicizing, they mean the process of “taking an explicitly antagonistic stance against extant institutions, values and practices”, in which state policies and practices are often entrenched but challenged by the confrontational actions of social movements [3] (p. 974). By policing, they mean the range of technologies, rationalities, and arrangements by which governments facilitate alignment of subjects (and NGOs) with the state.

In policing, governments allow NGOs to have an active role in decision-making and participation in policy implementation [3,5]. A manifestation of the transition from politicizing to policing is observed where NGOs stop defending marginalized groups of people and become agents of the state in assisting and monitoring the people being targeted by the state. NGOs thus “increasingly serve as the eyes, ears, and hands of the state” [3] (p. 8). Arguably, this potentially diminishes the range of actions NGOs can use to address inequality, injustice, and other socio-environmental issues and wrongdoings of the state and companies [3,5]. Moreover, NGOs that are busy being agents of the state have less time and energy to spend on the building of alternative societies and/or alternative futures [3,6]. Another outcome of policing is that social actors gradually put less effort into organizing actions and focus instead on managing social problems in cooperation with governments. However, NGOs might continue to seek collaborations and alliances at other scales to resolve conflict, exert pressure, make policy, and get their message across [9]. Several factors should be considered in the analysis of the alliances between the state and NGOs. Some considerations include that collaboration may be a necessity to achieve real change, or a pragmatic choice and opportunity for both parties to learn [28,30,31]. The ideological convictions that were once important for NGOs may have to be put aside. In the context of collaboration, whether NGOs are adversaries, collaborators, or surrogates of the state becomes unclear [6].

4. Methodology

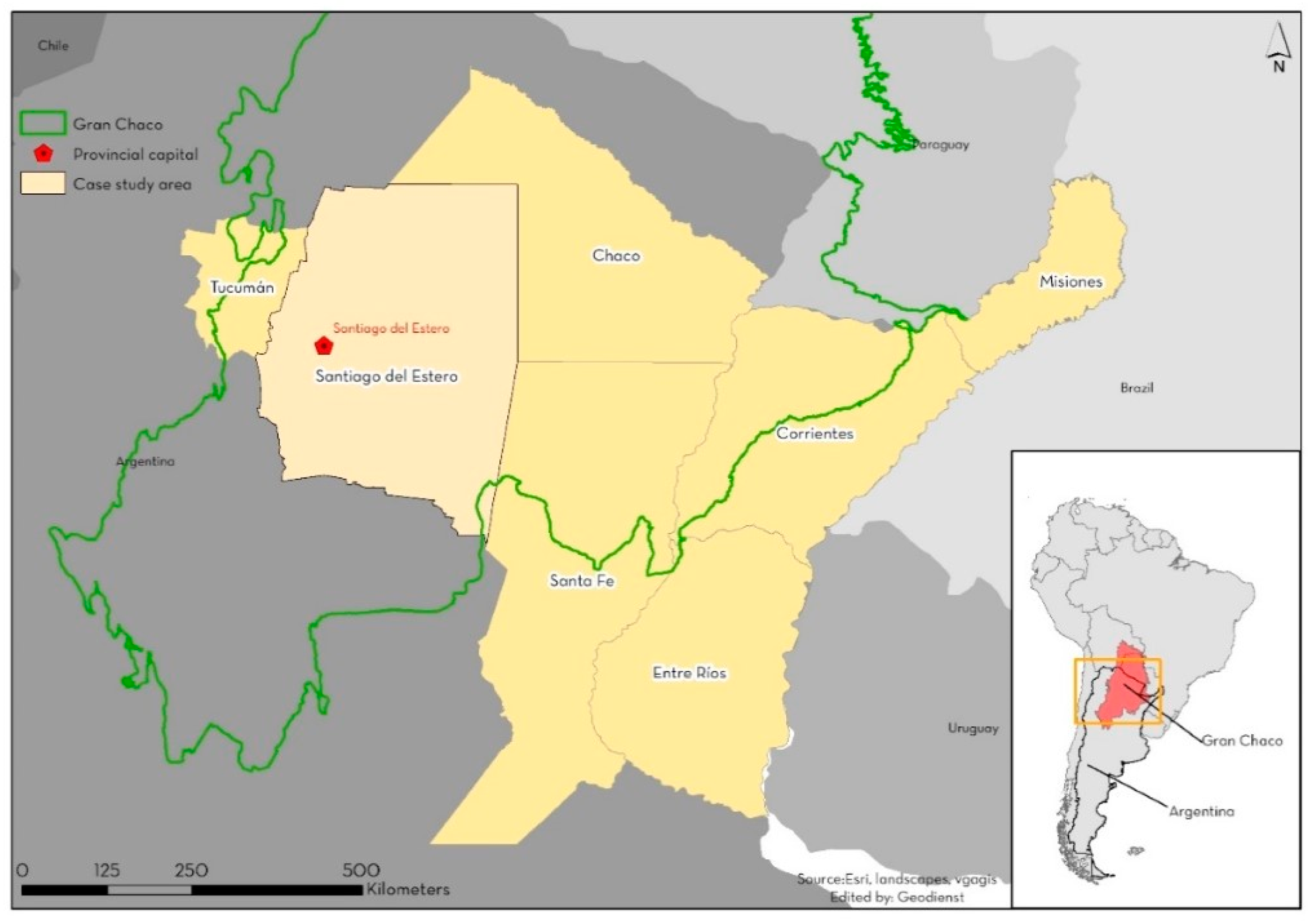

This paper is based on fieldwork carried out between 2011 and 2016. In total, 10 months were spent in Argentina (October–December 2011; November–December 2014; April-–July 2015; and April–May 2016). The fieldwork was part of a larger study, which focused on understanding the socio-environmental implications and governance dynamics of land grabbing for nature conservation, tree plantations, and agricultural expansion [10,11]. A multi-methods approach was used, including document analysis, analysis of media reports, participant observation, and in-depth interviews. In total, 70 in-depth interviews were conducted in Spanish with different types of actors, including government officials, researchers, NGOs, social movements, local communities, company representatives, and government institutions. These interviews were conducted in the provinces of Santiago del Estero, Corrientes, Tucumán, and Misiones (see Figure 1), as well as Buenos Aires, Córdoba, Entre Rios, and Santa Fe. Moreover, during the fieldwork, visits were made to many of the locations mentioned in the paper, including to forestry plantations, large-scale soy farms, and conservation reserves. The lead author also attended community meetings, demonstrations, and institutional stakeholder engagement activities.

Figure 1.

Map of Argentina showing location of Santiago del Estero. Source: Authors.

From October to December 2011, fieldwork was conducted with the assistance of a local NGO in Santiago del Estero. Aside from enhancing the resilience of local communities, this NGO supports them in issues relating to land tenure. As part of this collaboration, the lead author visited several communities experiencing land conflict. The strategies used by two communities to defend their land rights were intensively studied. To preserve anonymity of sources, these two communities are not named in the paper.

The aim of this paper is to consider the wider political processes that land grabbing provokes. It zooms in on the various collaborations between the provincial government and social movements (and NGOs) in Santiago del Estero. We specifically focus on two examples of such collaboration: El Registro de Poseedores (a registry of informal landholders) and El Comité de Emergencia (the Emergency Committee). These agencies were established in a context of social movements and NGOs pressuring the provincial government to address land conflict. This pressure was primarily applied by La Mesa Provincial de Tierras (the Provincial Roundtable for Land Issues), a shared platform involving social movements, NGOs, and the Catholic Church, which provided a forum for discussion and action on land issues. El Registro de Poseedores and El Comité de Emergencia were each established in 2007 to assist communities by facilitating the formalization of land titles and to support communities experiencing violence relating to land access.

For this paper, we primarily draw on 20 interviews undertaken specifically for the issues discussed herein. Interviews had a semi-structured character. These interviews were conducted in Santiago del Estero with community members, researchers, NGO representatives, persons representing (or collaborating with) the agencies being studied, social movement representatives, a land investor, and the key representative of the provincial government on these agencies (the Director of Dirección de Relaciones Institutionales). The interview participants were either experiencing land tenure issues themselves, or were studying or addressing these issues in various forms. Snowball sampling was used to select the interviewees.

A limitation of this research is that the lead researcher was only able to visit communities and talk to community members that had external connections, as she was typically introduced to these communities through gatekeepers. This may have influenced the findings, because the research is only of communities that are reasonably well-connected and well-functioning. Other limitations related to language nuance, given the regional dialects in some of the rural villages and that the lead researcher is not a native Spanish speaker. Therefore, statements about specific facts, events, or happenings were cross-checked or triangulated as much as possible. Prior to finalizing this paper, we followed up with our various contacts by email to verify and update certain information.

Interviews were recorded where appropriate and permission was granted. Where interviews were not recorded, detailed notes were taken. Field notes were also made after each research encounter. Informed consent was obtained for all interviews and other aspects of ethical social research were observed [32]. Recorded interviews were transcribed. The transcripts and notes were read several times by the lead author, with condensed summaries made. The quotes used in this paper have been translated into English by the authors. In translating the quotes into English, we have ensured that the intended meaning has been preserved, rather than necessarily providing an exact literal translation of the original Spanish.

5. Background to Land Grabbing in Argentina

Land grabbing can be understood as a wide range of strategies to control and gain access to land [11,33]. It often leads to local people being expelled or ousted from their land, and a conversion of family farming to industrial farming [34,35,36,37]. The expansion of large-scale agriculture, plantation forestry, and nature conservation initiatives has led to many issues related to land use, including rural violence, land tenure insecurity for smallholders, and the violation of the rights of indigenous peoples [12,34,38,39,40,41]. Land grabbing has led to food security issues for local communities, as well as to environmental degradation and health issues associated with agrochemical use [42,43]. Another impact is an increase in land prices [13,44].

As indicated above, the social and environmental issues associated with land grabbing have led to much conflict. This violence occurs in various ways, frequently in the form of armed thugs heavying informal land holders to leave their customary land [21]. There was also criminalization of environmental defenders by governments (at various levels) [12]. A state of hostility existed in Argentina, which led to social movements and NGOs being engaged in provocative actions, which, in turn, led to retaliatory and punitive actions by the state, and a downward spiral [12,21]. Thus, land grabbing can constitute a type of ‘slow violence’. Slow violence refers to the ultimately severe, long-term, insidious, negative consequences on communities and individuals, which are caused by individuals, companies, governments, and the processes of change. Slow violence also implies the negative social consequences that are not known, invisible, or overlooked [45]. An example of slow violence is the slowly-diminishing amount of land and water available for communities in locations where land grabbing is rife.

A factor that aggravates the impact of agricultural expansion on rural communities is that land tenure is not formalized in many locations. The Argentinian Civil Code (Código Civil y Comercial de la Nación) recognizes that formal title holders and informal land users can coexist on the same piece of land. Articles 2351, 2385, 2469, 2470, and 4015 of the Argentinian Civil Code describe the rights of informal landholders (see also [46]). The Code establishes that there are three ways by which people have rights over the use of land. The first is el propietario (owner, i.e., formal titleholder), someone who possesses formal documentation of ownership of the land. Their ownership is independent of its use. The second is el poseedor (possessor, i.e., informal titleholder), someone who does not have proof of ownership, but behaves as if they did, and may actually be able to make a legal case for ownership. The third is el tenedor (holder, i.e., renter), a person who uses the land but recognizes that another person (or entity) is the owner, but has certain rights established through lease or rental arrangements, whether formal or informal.

For poseedores to access judicial protection, there are two important elements. First, they must undertake activities on the land on a regular basis—for example, having constructed a house; demarcated the property with fences; utilized the land for grazing, orcharding, and/or cropping; and/or constructed water wells, dams, and/or pens for livestock. These activities are called actos posessorios (acts of possession). A person’s (or group’s) ability to claim rights depends on their ability to demonstrate that they have undertaken actos posessorios for at least 20 years continuously. The second element is that they should behave as if they were the real owners and defend it against people who pose a threat to this. In legal terms, they should be able to demonstrate ánimo de dueño (the spirit of being an owner of the land).

To obtain formal land title, poseedores can apply for a prescripción veinteañal (i.e., the twenty-year procedure). This is a legal procedure meant to enable informal titleholders to gain formal title of their land. The most important requirement is that people must have lived on the land continuously for a minimum of 20 years. It is very important that occupation of the land is not interrupted, especially because occupation rights and the occupation history are transferable to family members on the death of the poseedor. Another requirement is that the claims of possession as el poseedor must be endorsed by other people in the community.

The land that poseedores occupy can be formally owned by the state, a company, or a person. Because of the land rush, there are many new buyers in Argentina [13]. The sale of land by the formal land owners does not necessarily change the rights that poseedores have. This generates tension, especially when a land investor encounters communities of which they were not previously aware living on the land in question. Furthermore, the sale of the land is often the moment when local communities start a prescripción veinteañal. From a community rights perspective, one issue is that there is a lack of knowledge by local communities regarding their rights and the law, which may mean that they are sometimes persuaded (coerced) to leave the land and thus forfeit their ability to claim the right in the future. There are many factors that constrain people in commencing a prescripción veinteañal procedure, including the costs involved, the bureaucracy, as well as the amount of time it takes [13,38]. The agencies studied in this paper played a key role in assisting communities in the prescripción veinteañal procedure and in supporting communities in instances of conflict with a formal titleholder.

6. Land Grabbing and Land Use Change in Santiago del Estero

Santiago del Estero is part of the Gran Chaco region, which includes areas in Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Brazil [37] (see Figure 1). Gran Chaco is allegedly the world’s largest continuous dry forest [37]. Gran Chaco is also an active deforestation hotspot [42,47]. A high percentage of the population of Santiago del Estero are smallholders [44]. Most of them are descendants of the indigenous populations that historically populated the area. Their production is for self-consumption or sale in local markets [48]. Their activities include subsistence and market gardening, livestock grazing, hunting, and gathering [13,47,49]. Many smallholders practice communal land use strategies [13,37].

The province has a history of foreign companies exploiting its natural resources, including the Quebracho tree (Schinopsis balansae), which is a hardwood very useful for railway sleepers. Over time, resource exploitation has had severe ecological and socio-economic impacts for the province [13]. To build the railway network in the early 1900s, a large amount of hardwood was required, leading to deforestation of large areas [49]. After the railway companies left, many workers stayed on the land without formalizing land titles or adequately establishing their land occupation, resulting in contemporary land tenure insecurity [13].

For various reasons, land conflict is more prevalent and more severe in Santiago del Estero than in other provinces in Argentina [44]. There were many cases of forced eviction, violence towards smallholders, and intimidation [44]. The sub-secretary of Human Rights of Santiago del Estero reported that, from 2004 to 2011, 422 cases of conflict over land were registered, involving 6747 families [13]. According to Bidaseca et al. [44], in 2011, around 3500 families were affected by some type of land use issue in Santiago del Estero.

Land tenure insecurity began around the 1960s when there was an influx of investors interested in cultivating cotton, beans, and conventional soy [13,50]. From 1988, the rapid expansion of genetically-modified soy cultivation led to a major increase in land tenure conflict [13]. Governments regard commercial farming as superior to small-scale farming, seeing it as a strategy to obtain increased revenue, and were thus keen to facilitate land sales thereby opening-up Argentina to land grabbing [51].

Over time, the land grabbers included Argentinians from other provinces, as well as foreign investors. The investors from neighboring provinces such as Salta, Tucumán, Santa Fe, and Córdoba were attracted by low land prices, limited entry barriers, and little monitoring of activities. In 2011, Cristian Ferreyra was killed in a conflict with a land investor from the neighboring province, Santa Fe. The person who actually pulled the trigger was sentenced to a 10-year prison term for the crime, but the investor was absolved. With Cristian being a member of MOCASE, his death led to a series of protests in the capital city partly instigated by MOCASE. Also, there has been an increase in land investments from Argentine social elites and politicians [13].

In Santiago del Estero, there were large acquisitions by foreign firms, especially Chongqing Grain (a Chinese state-owned company) and Adecoagro (an investment fund partly owned by the magnate George Soros) [13,52]. Additionally, companies from France, Spain, the Netherlands, and South Korea are known to own land in the province. Aside from company investments, foreign social elites are also increasingly known to buy land, as well as hedge funds [13]. In 2011, the extent of foreign land ownership was limited under the presidency of Cristina Kirchner by Law 26.737, although foreign ownership still remains contentious [13]. The established rural elite also play a role in land grabbing, in that historic land owners (propietarios) are now increasingly inclined to sell land [38]. The provincial, as well as national, governments played an important role in the increase in land grabbing [13]. To attract businesses to the province, the Province Governor (Zamora) promoted official visits by foreign governments and companies, especially from South Korea and China, to Santiago del Estero. He also visited China to strengthen business ties [13,53,54].

An important issue associated with land grabbing is deforestation [47,55]. The agency responsible for approving land clearance is the Dirección de Bosques (i.e., Directorate of Forests). This agency implements the Forest Law of 2007. Despite extensive zoning of land clarifying what can and cannot be cleared, there is much concern about legal and illegal clearing [44,47,56]. Our fieldwork revealed that local authorities cannot do as much as they would like against illegal deforestation, given their limited capacity and the large territory in which they operate.

Agricultural expansion in Santiago del Estero has promulgated many governance challenges [13]. Many social movements and NGOs are concerned about the insecure land tenure situation, especially MOCASE, which was founded in 1990 in response to the expulsion of peasants from certain rural areas of Santiago del Estero [13,21]. With the global food crisis and increasing land grabbing from 2008 on, conflict escalated [57]. Several people were killed in defense of the land, including Eli Sandra Juárez (2010), Cristian Ferreyra (2011), and Miguel Galván (2012) [13,21]. The violence in the province stimulated NGOs to engage in different strategies to confront land grabbing.

7. State–Civil Society Collaborations in Response to Land Grabbing

The history of conflict in Santiago del Estero has been responsible for generating innovative responses. Since 1990, MOCASE has been pressuring the provincial government to find more effective ways to address the various issues experienced. As mentioned earlier, a turning point was the election of Néstor Kirchner as President in 2003, and the more inclusive policies that were implemented at all levels of government. With the endorsement of MOCASE, the provincial government implemented policies that had much greater support from civil society [22]. After the death of Néstor Kirchner, Cristina Kirchner continued with social justice policies and left-wing populism [58]. At the provincial level, the government entered into a range of collaborations with social movements and NGOs, including Incupo, Fundapaz, and Greenpeace. This was particularly embodied in the two agencies we study in this paper: El Registro de Poseedores and el Comité de Emergencia. These agencies were formally established as a joint initiative of the provincial government and civil society to address land conflict. The roundtable, La Mesa Provincial de Tierras, played a fundamental role in the initiation of these collaborations.

According to Law 7.054, the overarching aim of the Registro de Poseedores and the Comité de Emergencia is management of land tenure issues. The agencies take actions to ensure safe land tenure of rural inhabitants, especially those not holding formal title. The intention was that land tenure security would lead to greater community resilience and the development of sustainable and efficient land use. Overall, the law advocates respect for the values and the ways of life of the local communities. The Registro de Poseedores collects and provides accurate and precise information about land conflicts between its propietario and the poseedor. The Registro de Poseedores facilitates the obtaining of technical documentation for inhabitants who want to formalize their land tenure but lack the capacity to do so. The Comité de Emergencia intervenes when the possession rights of an individual, family, group, or rural community are threatened, for example by acts of physical or psychological violence, intimidation, harassment, property being damaged, or destruction of natural resources. The committee has responsibilities for: (1) Receiving notifications of cases to examine; (2) visiting the site to collect evidence; (3) mediating to resolve conflict; and (4) documenting the case in the event that there will be legal action. The Comité de Emergencia is also responsible for liaison between other government agencies in resolving conflict.

A social movement representative we interviewed in 2011 described the context in which the agencies were created. “It was chaos, the police and judges did not do anything regarding the violence.” According to our interviewee, there were armed thugs intimidating people to leave the land. “The creation of Comité de Emergencia and Registro de Poseedores was a direct response to the pressure created by our mobilizations and marches.” An employee of the Registro de Poseedores (Interview 2011) gave more detail:

“The Registro de Poseedores started in 2007 after a period with many problems, like the deaths of some peasants, as well as other issues. MOCASE and La Mesa Provincial de Tierras made a series of demands with marches and all of that. At that moment, an agreement was reached. La Mesa Provincial de Tierras made a proposal, which led to where we are now. The arrangement was that the provincial government would provide the logistics, including paying the salaries, transport and providing physical space. In addition, La Mesa Provincial de Tierras would provide the human resources.”

This perspective was extended on by a senior agency staff member (Interview 2016):

“Because of the creation of the two agencies, we have a mixed situation: the convergence of the state [Provincial Government] and the NGOs. There is constant interaction. I am not sure I want to say it is a relationship of tension, but it surely is an interaction of great challenge with respect to the execution of tasks. I am no longer a lawyer fighting against the state [as he was in his last job]; now I see all the conflict, and the challenge is to see how we can seek to influence and address conflicts together with the state.”

In an interview conducted with two government officials (2011), the work of the Registro de Poseedores was explained. Their first task is a technical survey and to develop the documentation needed to start a legal procedure (specifically plan de levantamiento territorial para la prescripción). The survey includes taking GPS coordinates, determining land area, and establishing evidence of having occupied the land for over 20 years. This information has to be verified by the provincial cadastral office/register of land titles (Dirección de Inmueble) before a legal procedure can start. The second task is the legal part, especially assembling the documents to establish continued occupation of the land. Various documents can be used, including sworn testimonies, historic photos, statements of payment of taxes and utility bills over the years, birth certificates, school records, and records of the vaccination of children and/or animals. An assessment is done to establish the accuracy, legitimacy, and adequacy of the survey details and documentation about occupation. If the assessment is positive, the community can apply for inscription of their property in the property registry (Registro de la Propiedad de Inmueble). However, as a response to this registration, it is possible that the legal title holder will start a counter claim (Juicio de Reivindicación). In the process, a lawyer, notary, and surveyor are needed. The whole legal procedure, which is relatively expensive for local communities, can take years. Even though the Registro de Poseedores assists with costs, communities still need to make a relatively large contribution.

The Registro de Poseedores has a role in assisting poseedores to strengthen their case to claim possession. To the frustration of one employee (Interview 2011), this role was not regarded as important by the provincial government. To ensure that poseedores can retain their possessory rights, assisting communities to remain independent and viable is very important. If communities become vulnerable, they could get into a precarious situation where they may have to move and, thus, potentially lose their continuity of occupation leading to the inability to claim land title. The Registro de Poseedores, therefore, actively promotes actions that enable people to continue to live on their land, including through the creation and maintenance of roads, and the provision of water supply and other infrastructure necessary for the livelihoods and wellbeing of rural communities. Rural decline has affected many rural areas in the province, as there is an absence of the state from key social responsibilities. During an interview, local government officials indicated that Santiago del Estero has been historically marginalized in terms of the allocation of funding by the national government, leading to poor provision of essential public services. If there would be no support for strengthening rural communities, they feared that there would be little future for peasants in Santiago del Estero.

The commodity boom in Argentina has led to an increasing demand for land, changing who the land owners are and how they relate to the people living on the land (see [13,[40]). The federal and provincial governments actively support agricultural expansion by various policies, resulting in land grabbing. One reason for this might be the need of foreign currency to pay off the large external debt. The historic land owners were often indifferent regarding the occupation of land by local communities, and therefore gaining formal title was not high on the list of priorities of local communities. However, the new land owners (i.e., the land grabbers) have a strong motivation to get rid of poseedores, whose lack of formal title puts the poseedores in a precarious situation. Sometimes, the new investors do not inspect the land before acquisition, and subsequently encounter people and communities living on the land the investors have bought, leading to conflict. In some cases, communities may first hear about their land being for sale by seeing advertisements from real estate agencies in newspapers. For them, an impending change in land ownership is a harbinger of future conflict.

Investors have several ways of coping with the presence of poseedores. They may try to expel poseedores using various tactics, both legal and illegal—including the use of threats, the use of private security forces, intimidatory behavior and harassment, entice them to leave by offering money or land elsewhere, hire them as employees, and/or let them stay on a smaller part of the land [10]. With a new land owner, it is very rare that the status quo will prevail. The reason why the Registro de Poseedores has a focus on strengthening possession is because this improves the position of poseedores in conflicts with new buyers, and is a precaution against being dispossessed while a legal procedure is underway.

As observed during our fieldwork, many communities were assisted by the two agencies. In one community assisted by the Comité de Emergencia, a local businessman inherited a formal land title of over 3600 hectares of land, on which a local community had lived for generations (see also [10]). Although this man’s family did not actively use the land, when he inherited it, he developed a plan to establish a major ranching operation and initially wanted to expel the community. The behavior and manner of him and his staff led to some members of the community feeling threatened, and it was evident that their continued occupation was at risk. The community contacted the Comité de Emergencia, which clarified their rights and assisted them in negotiating with the land owner. People from the Comité de Emergencia were present during community meetings and negotiations with the propietario, assisting the community in making the right choices like safeguarding access to the most fertile land in the negation with the propietario. They also helped the community in taking steps to enable them to stay on the land, including fencing their land. This made the community members feel safe and supported. With the help of the Comité de Emergencia and a local NGO, and without judicial involvement, the community was eventually able to negotiate with the propietario to gain formal land title to 1400 hectares. The owner paid all legal costs incurred by the community. He settled on owning 2200 hectares. This case is regarded as an exemplar by the provincial government and proof of the success of the two agencies. This was especially the case because, during the negotiations, the propietario came to appreciate the rights of the community and changed from being an adversary to a champion of the community, the two agencies, and the rights of poseedores.

Although this story seems promising, our fieldwork in this community in 2011 and 2016 revealed that the community faced several challenges in land formalization. The NGO assisting this community had been working for years to make the community more resilient. The NGO established several initiatives to enable the community to manage the diminished area of land better. The problem was that only a few of the community members were participating in these initiatives. This led to struggles within the community regarding the development of sustainable and efficient land use. Another issue was land taxes. Poseedores do not have to pay land tax, but when communities gain formal land title they then incur an obligation to pay land tax. Not all families could afford these taxes. This created tension in the community. It is unclear how this land tenure formalization will turn out in the long-run and how the community will address the challenges of paying taxes, having less land available, and the communal management of land.

Land titling and formalization reduce the impact of land grabbing on local people. However, in some cases, formalization may provide opportunities for land grabbing to occur, because it clarifies ownership and commodifies (and financializes) land [59]. Formal land titles may mean that local communities can ensure their ongoing control over land in the long-run, or it might lead to the forced sale of land in times of financial distress. Thus, even after the formalization of land, there is still a need to protect rural communities against the pressure that market actors can exercise to acquire land.

8. Incentives, Limitations, and Contradictions in Collaboration

In Table 1, we summarize the incentives, limitations, and contradictions inherent in state–civil society collaboration. Four overarching issues emerged during the analysis. The first issue is that the agencies can only work on demand and only have limited capacity and resources. This leads to reactive rather than proactive actions. This means that communities only ask for assistance after they encounter risky situations, when it may be too late to achieve desirable outcomes. In some situations, conflict may have already escalated before the communities ask for or receive assistance. An interviewee claimed that the provincial government was not being proactive in giving priority to strengthening the cases of communities to claim possession. As another interviewee said:

Table 1.

Overview of the incentives for, limitations to, and contradictions inherent in collaboration. NGOs: Non-government organizations.

“The Registro de Poseedores works on demand. This means we do not need to have a publicity campaign to get work. We go where the communities call for us. And when they call for us, this means that they already have a conflict, or where there is a real necessity for us to work with the community. It is not like we are going out of our way to look for the communities in need. There are only a few of us.”

The second issue relates to potential constriction of the operational space of NGOs that are in collaborations with government. Constriction can occur in several ways: By self-imposed reprioritization of the issues considered to be important; a conscious awareness of being tolerant of new friends, even when you do not agree with them about everything; or actual or perceived external restriction. In our interviews, there was very little mention of constriction, perhaps because of a reluctance to talk about this issue, given the general approval of the current collaboration arrangements. When the lead author of this paper raised this topic, most interviewees were evasive, non-committal, or vague in their responses.

A third issue is that the creation of the two agencies did not stop the violence towards rural communities or all of the expulsions taking place. The violence meant that the agencies could not focus only on their core tasks, but also had to deal with other immediately-pressing issues. It also meant that their employees felt unsafe. This fear affected their willingness to visit communities. NGOs again took action against the provincial government, as they were unhappy with the provincial governments’ ability to confront the issues faced. As a response to the presence of armed thugs and other tactics of land investors, and especially because of the death of Eli Sandra Juárez in 2010, MOCASE blocked Highway 34 for almost two months and held demonstrations in the provincial capital city. This suggests that, even though the NGOs (including MOCASE) were working with the provincial government, they were still able to apply political pressure.

A fourth issue was the difficulty in maintaining continuity of funding for these agencies. Some staff members of the Registro de Poseedores indicated that after one year of operation, the provincial government stopped paying its subvention to the agency. Thus, the two agencies started looking for other sources of income and identified that the national Subsecretaría de Agricultura Familiar (Sub-secretary for family farming, part of the Ministry of Agroindustry) was willing to support the program. After a few months, they discovered there were strings attached to this support, and they cancelled the arrangement. The Registro de Poseedores then successfully re-initiated dialogue with the provincial government.

9. Conclusions

Land grabbing triggers governance dynamics that have contributed to non-state and state actors cooperating to strengthen land rights and support the rural peasantry. The provincial government of Santiago del Estero and several NGOs took the initiative to create arenas for discussion, which led to a rethinking of their various roles and how they interact. A collaboration developed, which strengthened institutional arrangements for protecting and assisting rural communities. Civil society has now seen land issues better addressed. Coming from a background of weak technical and institutional capacity, by joining with NGOs, the province was able to make a significant contribution to addressing land conflict. The provincial government benefitted from the collaboration by being able to harness the resources of the NGOs, and develop more effective means of addressing locally important issues. The NGOs benefitted by progressing their objectives, but they still have many challenges ahead to ensure the security of land tenure of marginalized communities. This state–civil society collaboration showed that innovative governance initiatives can occur and have positive outcomes. Thus, our findings differ from some of the literature on state–civil society collaboration that suggest NGOs are always co-opted and constrained by these arrangements.

Our research identified that, in the case of Santiago del Estero, the outcomes of the collaboration between NGOs and the provincial government were: A better-informed civil society, empowerment of local communities, and improved land tenure security. However, the negative dimensions of agricultural expansion continue at the expense of local people. Rural communities continue to face violence and land tenure insecurity, and are forced to change their livelihoods. The Registro de Poseedores and the Comité de Emergencia were not strong enough to stop companies from expanding their land acquisition activities or to have the values and ways of life of rural communities in Santiago del Estero respected. Given that the national and provincial governments were keen on attracting foreign investment, despite the contribution the NGOs made, they were still not able to provide an adequate counter balance against international companies.

Elaborating further on this, there are several potential reasons why the outcome of the collaboration between NGOs and the provincial government can be considered problematic. First, land investment proceeds, as there is an economic dependence by state actors on the revenues made from land investment. Second, land grabbing continues, given the constant global demand for commodities. Third, there continues to be a general lack of respect for customary land tenure, which makes avoiding land conflict difficult. Fourth, the state potentially facilitates land grabbing, because it believes it can improve the socio-economic position of local communities. Finally, the limited countervailing power NGOs have makes them unable to fully meet their goals.

What we can learn from the collaborations discussed in this paper is that they are important in a context in which local communities cannot, on their own, exert pressure on companies to respect their customary tenure. Also, the willingness of the provincial government to collaborate with NGOs shows that, under certain circumstances, key actors are willing to listen to the concerns of people, or can be forced to do so. To further understand the issues addressed in this paper, a deeper analysis of how the goals of such agencies can be better embedded in and supported by laws and regulations is needed. Moreover, research is needed on how community-focused government agencies can establish their value in a context of violent repression of rural people. These insights will be central to promoting social justice and for enabling local communities to maintain access to the resources that are essential for the continuation of their livelihoods.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.B. and C.P.; methodology, N.B. and C.P.; formal analysis, N.B., F.V., and C.P.; investigation, N.B.; data curation, N.B., F.V., and C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, N.B.; writing—review and editing, N.B., F.V., and C.P.; supervision, F.V. and C.P.; project administration, F.V. and C.P.; funding acquisition, N.B. and C.P.

Funding

This research was funded by Erasmus Mundus Action 2 EURICA, grant number 2013-2587, and the Research Fund of the KU Leuven, grant number STG 14/022.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the people in Argentina who contributed by sharing their experiences, knowledge, and time. On top of that, there were some people especially helpful in the process of developing this paper, such as Mohamed Saleh, Koen Bandsema, and Julia Gabella. We would also like to thank the Geodienst of the University of Groningen for providing us with a map of the study region.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McKay, B. The politics of agrarian change in Bolivia’s soy complex. J. Agrar. Chang. 2018, 18, 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapegna, P. The political economy of the agro-export boom under the Kirchners: Hegemony and passive revolution in Argentina. J. Agrar. Chang. 2017, 17, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uitermark, J.; Nicholls, W. From Politicization to Policing: The Rise and Decline of New Social Movements in Amsterdam and Paris. Antipode 2014, 46, 970–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Camus, L.; Kay, C. Agribusiness, peasants, left-wing governments, and the state in Latin America: An overview and theoretical reflections. J. Agrar. Chang. 2017, 17, 239–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massetti, A. Limitaciones de los movimientos sociales en la construcción de un estado progresista en Argentina. Argum. Rev. Crít. Soc. 2010, 12, 81–108. [Google Scholar]

- Reilly, C.A. Public Policy and Citizenship. In New Paths to Democratic Development in Latin America: The Rise of NGO-Municipal Collaboration; Reilly, C.A., Ed.; Lynne Rienner Publishers: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, F. Estado movimientos sociales: Disputas territoriales e identitarias. La Organización Barrial Tupac Amaru—Jujuy-Argentina. Revista 2017, 20, 86–106. [Google Scholar]

- Dangl, B. Dancing with Dynamite: Social Movements and States in Latin America; AK Press: Edinburgh, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Jessop, B. The State: Past, Present, Future; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Busscher, N.; Parra, C. Vanclay, F. Environmental justice implications of land grabbing for industrial agriculture and forestry in Argentina. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busscher, N.; Parra, C.; Vanclay, F. Land grabbing within a protected area: The experience of local communities with conservation and forestry activities in Los Esteros del Iberá, Argentina. Land Use Policy 2018, 78, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brent, Z.W. Territorial restructuring and resistance in Argentina. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 671–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara, C.; Paz, R. Ordenar el territorio para detener el acaparamiento mundial de tierras. La conflictividad de la estructura agraria de Santiago del Estero y el papel del estado. Proyección 2013, 15, 171–195. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, B.; Qi, H. Contingencies of Power Sharing in Collaborative Governance. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 2017, 48, 836–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, C. Sustainability and multi-level governance of territories classified as protected areas in France: The Morvan Regional Park case. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2010, 53, 491–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E. Governance Innovation and the Citizens: The Janus Face of Governance-beyond-the-State. Urban Stud. 2005, 42, 1991–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, J.A. Territory, Politics, Governance. Territory Politics Gov. 2013, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corson, C.; MacDonald, K.I. Enclosing the global commons: The convention on biological diversity and green grabbing. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, B.; Kothari, U. (Eds.) Participation: The New Tyranny? Zed Books: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Del Huerto Díaz Habra, M.; Franzzini, M. Políticas Publicas Fiscales: La Reforma del Código Procesal Penal en Frías. Diferentes Estrategias de Intervención en el Territorio. In Desarrollo Rural, Política Pública y Agricultura Familiar. Reflexiones en torno a experiencias de la Agricultura Familiar en Santiago del Estero; Gutiérrez, M.E., Gonzalez, V.G., Eds.; Magna Publicaciones: San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina, 2016; pp. 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Lapegna, P. Notes from the field. The expansion of transgenic soybeans and the killing of Indigenous peasants in Argentina. Soc. Bord. 2012, 8, 291–308. [Google Scholar]

- Jara, C.; Gil Villanueva, L.; Moyano, L. Resistiendo en la frontera. La Agricultura Familiar y las luchas territoriales en el Salado Norte (Santiago del Estero) en el período 1999–2014. In Desarrollo Rural, Política Pública y Agricultura Familiar. Reflexiones en torno a experiencias de la Agricultura Familiar en Santiago del Estero; Gutiérrez, M.E., Gonzalez, V.G., Eds.; Magna Publicaciones: San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina, 2016; pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Nogueira, R. Negotiated Interactions: NGOs and Local Government in Rosario, Argentina. In New Paths to Democratic Development in Latin America: The Rise of NGO- Municipal Collaboration; Reilly, C.A., Ed.; Lynne Rienner Publishers: Boulder, CO, USA, 1995; pp. 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, C.; Moulaert, F. The governance of the nature-culture nexus: Lessons learned from the San Pedro de Atacama case-study. Nat. Cult. 2016, 11, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, S.L. Los Movimientos sociales en la Argentina: De los noventa a la actualidad: Origen, desarrollo y perspectivas. Teoría y Praxis 2015, 27, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zibechi, R. Territorios en resistencia: Cartografía política de las periferias urbanas latinoamericanas; La Vaca: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Newell, P. Bio-Hegemony: The Political Economy of Agricultural Biotechnology in Argentina. J. Lat. Am. Stud. 2009, 41, 27–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gera, W. Public participation in environmental governance in the Philippines: The challenge of consolidation in engaging the state. Land Use Policy 2016, 52, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, P.; Vanclay, F.; Langdon, J.; Arts, J. Conceptualizing social protest and the significance of protest action to large projects. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2016, 3, 217–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, C. Return to Freedom: Anti-GMO Aloha ‘Āina Activism on Molokai as an Expression of Place-based Food. Globalizations 2015, 12, 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulaert, F.; MacCallum, D.; Mehmood, A.; Hamdouch, A. (Eds.) The International Handbook on Social Innovation: Collective Action, Social Learning and Transdisciplinary Research; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vanclay, F.; Baines, J.; Taylor, C.N. Principles for ethical research involving humans: Ethical professional practice in impact assessment Part I. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2013, 31, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R.; Edelman, M.; Borras, S.M.; Scoones, I.; White, B.; Wolford, W. Resistance, acquiescence or incorporation? An introduction to land grabbing and political reactions ‘from below’. J. Peasant Stud. 2015, 42, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, D.M. Accumulation by dispossession and socio-environmental conflicts caused by the expansion of agribusiness in Argentina. J. Agrar. Chang. 2015, 15, 116–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craviotti, C. Agrarian trajectories in Argentina and Brazil: Multilatin seed firms and the South American soybean chain. Globalizations 2018, 15, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giarracca, N.; Teubal, M. Argentina: Extractivist dynamics of soy production and open-pit mining. In The New Extractivism. A Post-Neoliberal Development Model or Imperialism of the Twenty-First Century? Veltmeyer, H., Petras, J., Eds.; Zed Books: London, UK, 2014; pp. 47–79. [Google Scholar]

- Matteucci, S.D.; Totino, M.; Arístide, P. Ecological and social consequences of the Forest Transition Theory as applied to the Argentinean Great Chaco. Land Use Policy 2016, 51, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, L.; van der Haar, G. The moving frontiers of genetically modified soy production: Shifts in land control in the Argentinian Chaco. J. Peasant Stud. 2016, 43, 562–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguizamón, A. Modifying Argentina: GM soy and socio-environmental change. Geoforum 2014, 53, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murmis, M.; Murmis, M.R. Land concentration and foreign land ownership in Argentina in the context of global land grabbing. Can. J. Dev. Stud. 2012, 33, 490–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, F. Principles to assist in gaining a social licence to operate for green initiatives and biodiversity projects. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 29, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leguizamón, A. Environmental injustice in Argentina: Struggles against genetically modified soy. J. Agrar. Chang. 2016, 16, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otero, G.; Lapegna, P. Transgenic Crops in Latin America: Expropriation, Negative Value and the State. J. Agrar. Chang. 2016, 16, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidaseca, K.; Gigena, A.; Gómez, F.; Weinstock, A.M.; Oyharzábal, E.; Otal, D. Relevamiento y Sistematización de Problemas de Tierras de los Agricultores Familiares en Argentina; Ministerio de la Agricultura, Ganadería y Pesca de la Nación: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2013.

- Nixon, R. Slow Violence and Environmentalism of the Poor; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fundapaz. Derechos Posesorios-Prescripción Veinteañal. n.d. Available online: http://www.fundapaz.org.ar/cartillas/derechos-posesorios-prescripcion-veinteanal/ (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Volante, J.N.; Mosciaro, M.J.; Gavier-Pizarro, G.I.; Paruelo, J.M. Agricultural expansion in the Semiarid Chaco: Poorly selective contagious advance. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapegna, P. Genetically modified soybeans, agrochemical exposure, and everyday forms of peasant collaboration in Argentina. J. Peasant Stud. 2016, 43, 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altrichter, M.; Basurto, X. Effects of land privatization on the use of common-pool resources of varying mobility in the Argentine Chaco. Conserv. Soc. 2008, 6, 154–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargoltz, R.E. Hacha y quebracho. Historia ecológica y social de Santiago del Estero; Marco Vizoso Libros: Santiago del Estero, Argentina, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Rudi, L.M.; Azadi, H.; Witlox, F.; Lebailly, P. Land rights as an engine of growth? An analysis of Cambodian land grabs in the context of development theory. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 564–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infocampo. Adecoagro compró otro campo en Santiago del Estero por 18 milliones de dólares. 2011. Available online: http://www.infocampo.com.ar/adecoagro-compro-otro-campo-en-santiago-del-estero-por-18-millones-de-dolares/ (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Ortiz de Rozas, V. El gran elector provincial en Santiago del Estero (2005-2010). Una perspectiva desde adentro de un “oficialismo invencible”. Rev. SAAP 2011, 5, 359–400. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, L.A. Elecciones 2017-Santiago del Estero: Zamora fue Electo Gobernador por Tercera vez y Sucederá a su Esposa. 2017. Available online: www.lanacion.com.ar/2074701-elecciones-2017-santiago-del-estero-zamora-fue-electo-gobernador-por-tercera-vez-y-sucedera-a-su-esposa (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- García, M.; Román, M.; del Carmen González, M. Desmonte y soja en una Provincia del Norte Argentina: Implicaciones Ecosistémicas y Socio-económicas. Ambiente y Desarrollo 2014, 18, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foro Ambiental. Santiago del Estero: El dueño de Manaos otra vez acusado de usurpación y desmontes clandestinos. 2017. Available online: https://www.foroambiental.net/archivo/noticias-ambientales/recursos-naturales/2380-santiago-del-estero-el-dueno-de-manaos-otra-vez-acusado-de-usurpacion-y-desmontes-clandestinos-2 (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Zoomers, E.B. Globalization and the foreignization of space: The seven processes driving the current global land grab. J. Peasant Stud. 2010, 37, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, E.; Murillo, M.V. Argentina: The persistence of Peronism. J. Democr. 2012, 23, 148–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loehr, D. Capitalization by formalization? Challenging the current paradigm of land reforms. Land Use Policy 2012, 29, 837–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).