1. Introduction

Fast economic development is often accompanied by rapid urbanization or rural-urban migration in developing countries. In the past 40 years, Chinese rural areas and agricultural production have witnessed substantial progress with neck-breaking speed ever since the implementation of the Reform and Opening-up Policy in the late 1970s. However, urbanization and industrialization have also had a detrimental impact on rural development [

1,

2,

3]. With the non-agriculturalization of rural populations, hollowed villages, environmental pollution, and increased poverty, a series of “rural problems” have emerged [

2]. As urbanization progresses, massive numbers of rural residents migrate into large and coastal cities [

4,

5,

6]. Most of these people work and live in cities, even without holding an urban

hukou (a residential registration system in China), while leaving rural homesteads in the countryside. As a result, many rural houses stay vacant, leading to a serious waste of land resources. Simultaneously, the development of urbanization has brought a series of problems to cities themselves. For example, water pollution, air pollution, and solid waste pollution in cities have become increasingly prominent, which has affected the regular lifestyle of urban residents [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Congested traffic, skyrocketing housing prices, and a shortage of public services (e.g., schools, hospitals) are causing adverse impacts on the welfare of urban residents. These phenomena are prevalent throughout the world, especially in fast-developing countries like China.

Many countries are expanding their cities to boost their economies and living standards [

4]. The proportion of people living in urban areas around the world rose from 33% in 1960 to 54% in 2016, with particular growth in Asia and Africa [

12] and in North America and Europe, more than three-quarters of the population already live in urban areas; urban areas are growing and expanding [

13]. The ever increasing and expanding of urban areas and the population was often accompanied by emigration and depopulation of rural areas, as well as the abandonment of farmland and rural houses. These empty farmsteads, the half-filled factory, the vacant storefronts, and the threadbare homes are all too familiar in the postindustrial heart of the United States [

14]; Some central and eastern European countries, such as Poland, also experienced a continuing dip in agricultural productivity and agricultural employment, and this process was followed by migration, urbanization, and modernization of housing [

15]. The vacant farmhouses become a big waste of assets as well as resources, while also hindering rural development.

On the other hand, rapid and overextended urbanization may lead to a stressful life in urban conglomerates due to long commutes, traffic congestions and accidents, severe air and water pollution, high crime rate, stress, and the squalor of slums [

13]. As one of the largest developing countries, India, for example, has been suffering from severe problems such as the development of slums, pollution, and noise issues during the process of urbanization [

16]. In recent decades, due to these serious “urban diseases, “ many urban residents have started to show a desire to live in the countryside. Many medium-high income citizens opt to move from metropolitan areas to suburban or even rural areas. This urban-rural migration, or so-called ex-urbanization, has been widely observed in developed countries, like in the United States of America. Alternatively, citizens sometimes choose to buy or co-own a second house in rural areas. In Finland, for example, rural second home tourism has become a fundamental part of the country’s cultural identity and modern life [

17]. This trend is also emerging in developing countries such as China, where middle- and high-income citizens show great interest in living in rural areas or purchasing a second or weekend houses in rural areas. Additionally, thanks to the widespread use of the internet, many people can work remotely, e.g., from home. The COVID-19 pandemic further strengthened the work-from-home trend.

The situation involving vacant farmhouses and “urban diseases” is especially worrisome in China. Massive rural-urban migration has created demographic problems. The rural population decreased from 790 million in 1978 to 570 million in 2018 [

18]. While the rural population has been reducing substantially, the total area of China’s villages is expanding at the cost of fertile cropland despite the scarcity of farmland in China. For example, from 1990 to 2016, the total villages area did not decrease with the dropping of the rural population; instead, this population increased by about 2.52 million hectares [

19]. This perplexing phenomenon is a direct result of two things. Firstly, the migration of a large number of rural populations to cities has left many dwellings in the village unoccupied either seasonally or permanently [

1]. Secondly, new modern houses are continued to be built on the village’s periphery, often at the expense of fertile farmland, to get bigger homesteads without demolishing the old houses that are usually characterized by smaller homesteads and basic building materials [

20]. The underlying reason for these trends is that most rural migrants face difficulties completely settling down in cities due to the barriers they face, such as not holding the relevant

hukou. Working and living in cities do not automatically entitle them to an urban

hukou; thus, they cannot enjoy the same benefits in education, healthcare, and social security as urban citizens with an urban

hukou [

21,

22]. In addition, many rural migrants do not have a permanent job and lack job security. They are not entirely urbanized even though they live in cities for a long time. Consequently, the migrants still want to keep their rural houses and even build new ones even if they do not need to live there. In other words, those rural houses serve as a form of social security [

23]. In some cases, migrants may have an urban

hukou or simply want to sell their rural houses. However, there is little demand within the village in such cases, as rural construction lands are collectively owned and rural houses can only be exchanged within the village. Thus, these migrants cannot capitalize on the potential economic value of their rural houses and improve their life in the city through transactions [

24]. Ultimately, this is indirectly caused by the lack of a functioning rural housing market and institutional barriers, like the

hukou system.

In big cities, on the other hand, the issues of traffic congestion [

25], haze [

26,

27,

28], soaring housing prices [

29], and food safety concerns [

30,

31] are becoming increasingly prominent in China. Concurrently, the travel time between urban and rural areas has been shortened due to the fast development of transportation infrastructure such as highways, high-speed railways, subways, and light rail, in recent years. These developments facilitate the daily commute of urban residents living in rural areas, as well as shorter commutes for activities such as business meetings and leisure trips [

32]. As a result, more and more urban residents wish to move to the countryside for better traffic conditions, fresher air, cheaper houses, safer food, and a quieter environment. However, China has not yet established a rural vacant farmhouse market because the collectively-owned rural homesteads can only be used by members of collectives and cannot be transferred outside the original collective, i.e., urban residents. Nevertheless, lured by significantly lower housing prices in rural areas, urban residents in some cities buy or rent rural homesteads and rural houses under informal transactions—strictly speaking, these are illegal transactions [

33].

Given the profound scientific and policy implications of these developments, the homesteads and vacant rural houses in rural China have attracted increasing attention from international researchers. The homestead here refers to the construction land allocated to rural residents by the collective community, i.e., the village, for building self-used rural houses. While rural houses on top of the homestead are private properties, the homesteads, which are the lands that houses are built on, are collectively owned. This unique tenure system hinders the formation of the rural housing market. Most of the current studies address homestead withdrawal (i.e., giving up the homesteads), homestead transfer, and the institutional systems of rural homesteads (e.g., tenure settings). For example, a study analyzed factors that affect farmers’ willingness to withdraw (or give up) homesteads in Zhejiang Province. The research showed that farmers are reluctant to give up their homesteads due to the concerns regarding employment risk, lack of social security, the high cost of new houses, low compensation for homesteads, the decline in the standard of living, and inconvenience in agricultural production. The authors thus argued that employment support and social security provision are the keys to enabling the farmers to give up their homesteads [

34]. In terms of homestead transfer, a study on Shenzhen’s reforms that allow collective-owned rural land transactions in the open market found that the dual-track land administration system, that is, the state manages market transactions, has led to many social problems, such as urban construction land scarcity, the inefficiency of land resource allocation, and exacerbated social injustice [

35]. Another study explored the advantages and disadvantages of the existing rural homestead transfer models through comparative analysis and proposed a new rural homestead land transfer system under collective ownership. This research provides a clear direction for rural homestead land transfers [

36]. As for the institutional setting of the rural homestead system, Zhou et al., studied the evolution of China’s land system, analyzed the main problems and new challenges in China’s land system, discussed the current specific measures used to deepen China’s land system reform, and pointed out that the development direction of China’s rural land system reform is to make the property rights relationship clearer, the farmland rights more complete, the transfer transactions more market-oriented, and the property rights’ protection more equal [

37]. Some studies that commented on the new Law of Land Management in August 2019, discussed the potential challenges that the country may face in revitalizing rural areas and called for further institutional innovation in rural land system reform. The proposal is that the rural residential land acquired for a fee can be freely transferred or converted [

38]. The above-mentioned related studies have introduced some basic conditions, theoretical discussions, and typical cases of China’s rural homesteads to the international academic community. These studies are related to the potential rural housing transactions; however, there are relatively few studies on the construction of China’s rural housing market, especially in international journals.

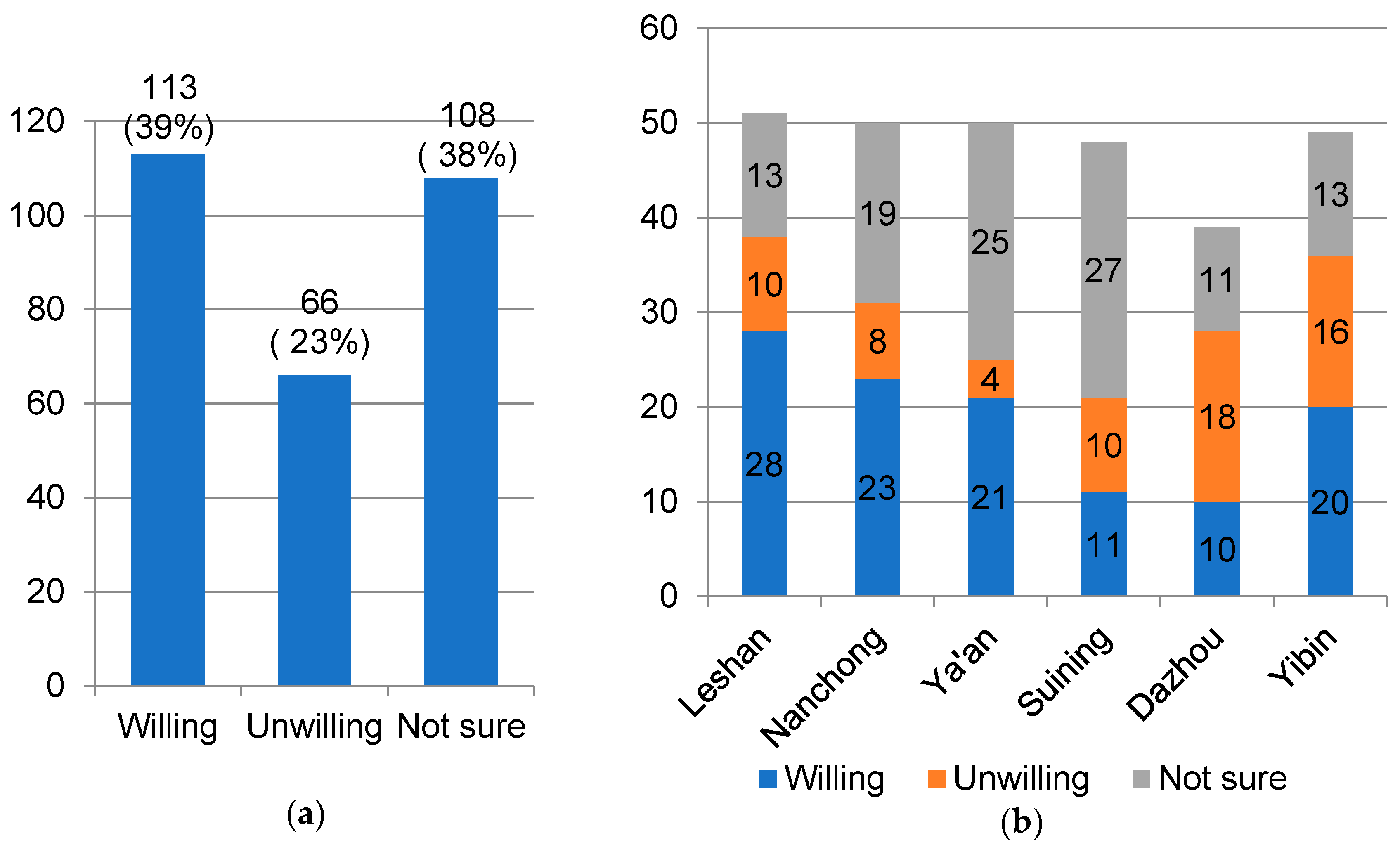

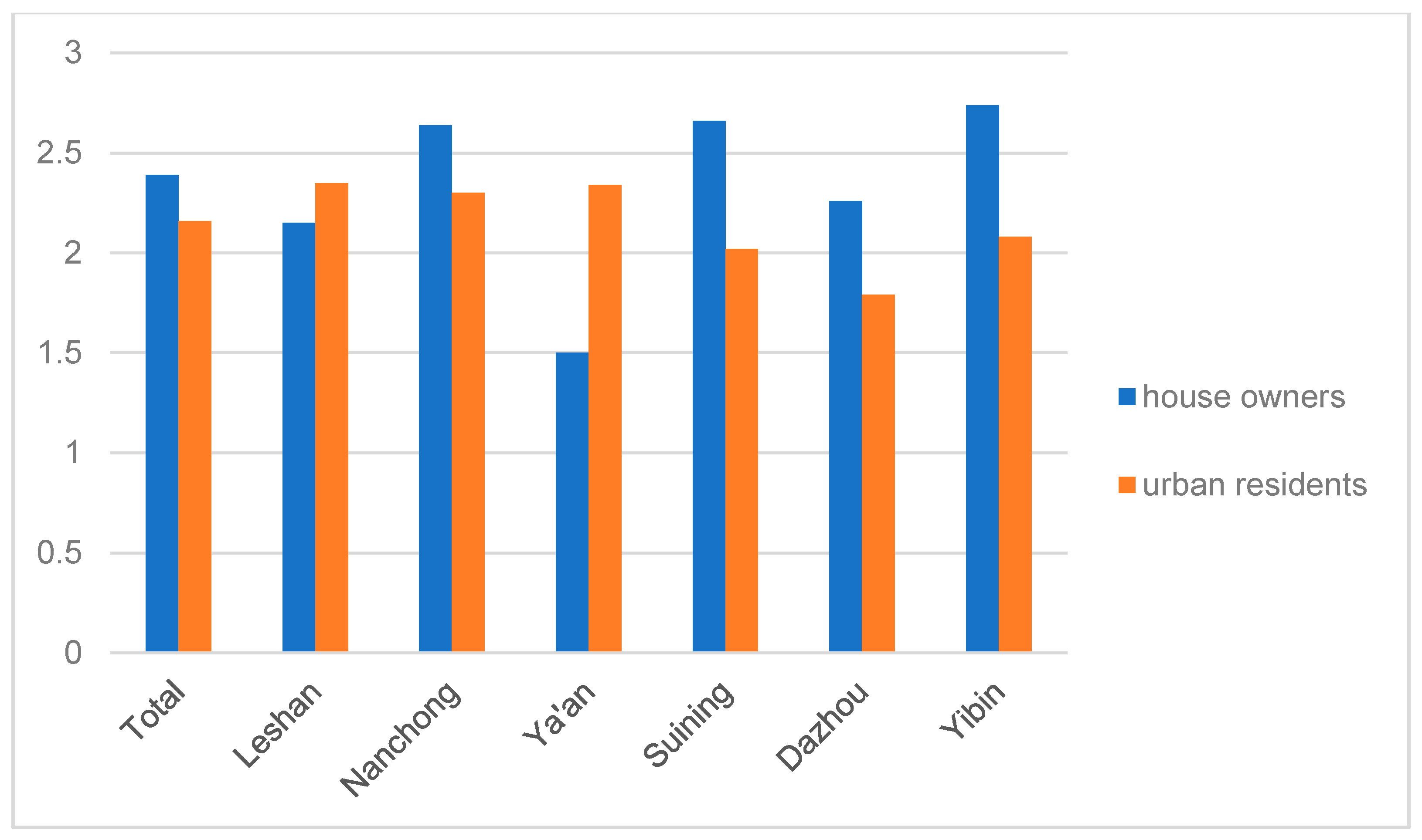

To bridge this research gap, we focus on the potential demand and supply of vacant rural houses. In any market, transactions only happen when the supply matches the demand, implying an acceptable price for both suppliers and buyers. While the real estate market in cities of China has been functioning ever since the reform of commercialization of urban housing in the 1990s [

39], there is not yet a functioning vacant farmhouse market in China. To assess the potential formation of the vacant farmhouse market (VFM), we need to first investigate whether there are enough suppliers and demanders who are willing to sell or buy farmhouses, and then what kind of products are needed and what is the acceptable price. The farmers who own vacant farmhouses are the possible suppliers while the citizens who are willing to live in the countryside are the possible demanders. Therefore, in this research, we studied whether there are enough suppliers, i.e., owners of the vacant farmhouse, and demanders, urban residents who are willing to live in the countryside, and what kind of products, i.e., farmhouses, are needed and planned to conduct further study on the acceptable price in the future. Thus, we specifically examine the willingness and influencing factors of house owners and urban residents involved in rural house transactions. To do this, we conducted a questionnaire-based survey on randomly selected rural housing owners and urban residents in Sichuan Province, China. With these survey data, we used logistic regression to assess the influencing factors of the willingness of these transaction participants. Based on the empirical analysis result, we then assessed the necessity and feasibility of establishing the VFM. We further put forward advice for the government to formulate related policies in the future in supporting the VFM.

The rest of the paper is constructed as follows.

Section 2 describes the institutional and legislative framework on the property and rights of rural housing, the study area, and the data survey.

Section 3 briefly introduces the data and methods used in the analysis. In

Section 4, we present the analysis of farmers’ and urban residents’ willingness to participate in VFM and its influencing factors and discuss the empirical analysis results.

Section 5 concludes with a summary of the main results of this research, policy implications, and future research.

2. Study Area and Data Source

2.1. Institutional and Legislative Framework on the Property and Rights of Rural Housing

Given the unique setting of the rural housing tenure system in China, as we already mentioned in the Introduction, it is necessary to further describe the tenure system of rural houses and related institutions. China is a society with a dual structure of urban and rural systems for people and lands: residents are in general classified as rural residents and urban residents according to the household registration system, widely known as the

hukou system [

22]; while urban land is state-owned, rural land is collectively-owned by villagers living in the same community, i.e., villages. Therefore, the land management agency has adopted different management and governing regulations for urban and rural areas [

40]. Compared with urban construction land, which is given full land rights, including possession, use, income-generating, and disposal, rural construction lands including rural homesteads have limited property rights and are heavily restricted by relevant laws [

41]. According to China’s Constitution and Land Management Law, rural land, including farmhouses, is owned by rural collectives and prohibits homestead transfer outside of the collective. Therefore, only members of the collective can use and manage collective land [

42]. The current complicated and unreasonable land tenure system inhibited the formation of the rural housing market. This in turn leads to the idleness of an increasing number of vacant houses, which is exacerbated by the demographic changes caused by the rural-urban migration and the low fertility rate. Farmers are, unfairly, being deprived of the chance to generate income from these vacant assets, renting them out, or selling them.

In recent years, the Chinese government has embarked on the reform of the homestead system to revitalize the vacant land resources in rural areas. There are four main tasks in the reform of the homestead system, i.e., reforming the way to protect and obtain the rights and interests of the homestead, exploring the system of paid use of homestead, and the mechanism of voluntary withdrawal and improving the management system of the homestead. Since 2015, the government has carried out rural “three pieces of land” (i.e., agricultural land, rural operational construction land, and homesteads) reforms to regulate farmland acquisition for construction, market entrance of collective operational construction land, and homestead management system, in 33 cities and counties across the country from 2015 to 2018. These pilot areas were allowed to remove some restrictions on rural land in the Land Management Law and the Urban Real Estate Management Law.

At the same time, the No.1 document of the CPC Central Committee in 2018 further clearly stated that the “Separation of three rights (the rural homestead collective land ownership, the qualification rights for homestead allocation, and the homestead land use rights) in homestead” should be explored. Moreover, the rural homestead collective land ownership should be implemented, and the qualification rights for homestead allocation and the farmer house property rights for homestead should be ensured, and the homestead land use rights and farmer house use rights should be moderately released, step by step. In 2019, China’s “Land Management Law” has officially stipulated that China’s non-agricultural construction land will have the same rights as the state-owned urban land, clearing up the legal barriers to the entry of collectively operated construction land into the market. This means that in the near future, China will likely establish a pilot for the VFM, and the research will hopefully provide a certain reference value for the pilot construction.

2.2. Study Area

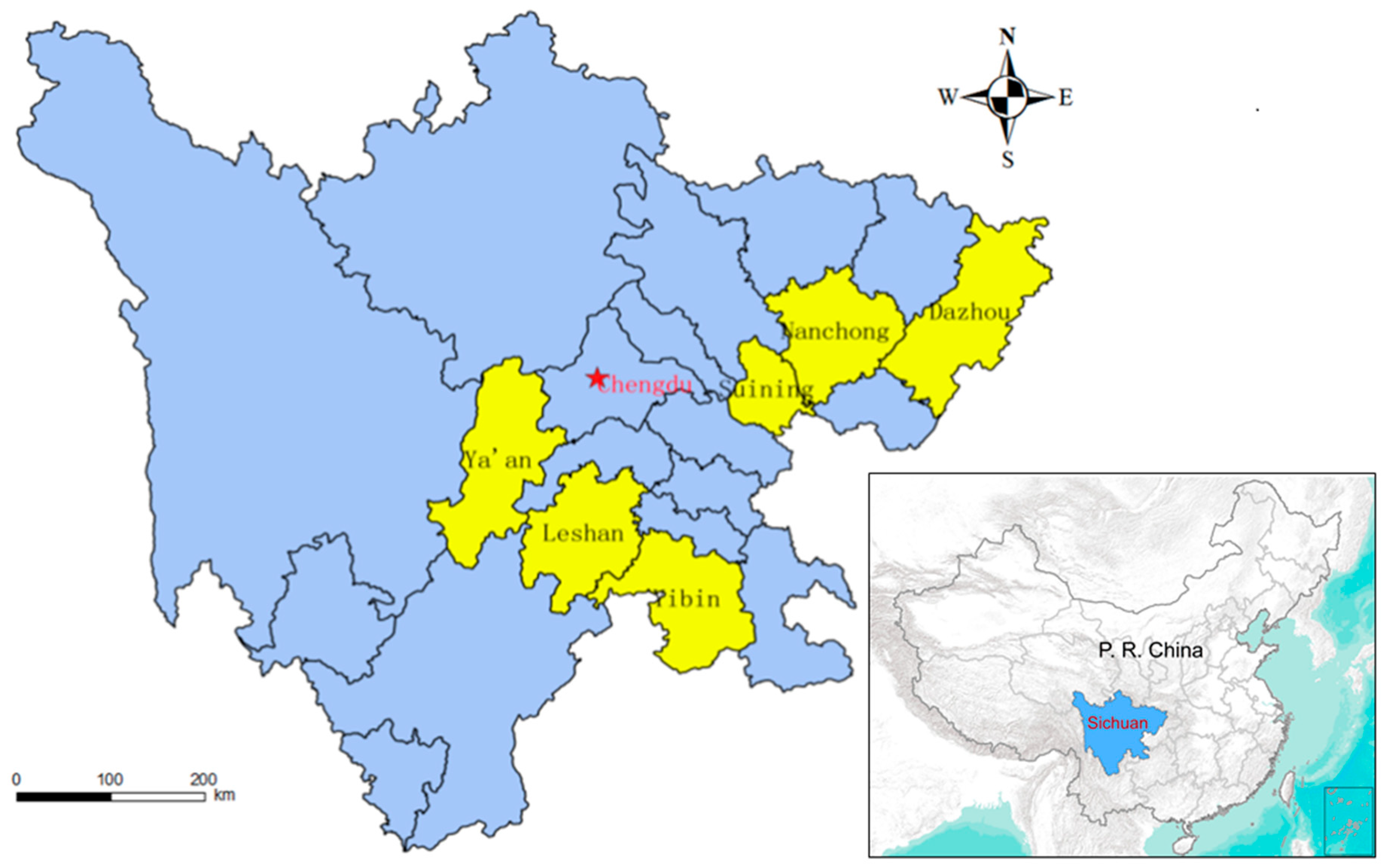

Sichuan Province is located upstream of the Yangtze River in southwestern China. It covers 486, 052 km2 and has a population of 81.07 million, of which 44.67 million are engaged in agricultural production [

43]. The total labor force of Sichuan in 2013 was 64.39 million, of which 33.68 million were rural laborers [

43]. Statistical data shows that in 2014, the number of migrant workers in Sichuan Province reached 24.723 million, making it the country’s largest labor exporting province. In rural areas of Sichuan, especially remote areas, the problem of rural labor loss is prominent, and most of the people left behind in the countryside are lonely old people and left-behind children. A large predominately young and middle-aged labor force has been transferred to the cities, and a large population migration has caused vacant rural housing and other problems. Data show that in many rural areas of Sichuan province, the vacant rate of farmhouses is close to 40% [

44]. Therefore, rural real estate waste is particularly serious in Sichuan Province, compared with in other provinces, making it a good example for studying farmers’ and urban residents’ willingness to participate in VFM.

2.3. Sampling Strategy

We adopted a stratified random sampling design: we first selected six cities from the strata defined by the level of urbanization and economic development in Sichuan Province. Thus, the survey samples can representatively reflect the general situation of the entire Sichuan Province. From each city, we tried to randomly sample 50 house owners and 50 urban residents to fill out the questionnaires through face-to-face interviews. In doing so, we strived for a decent sample size for the later regression analysis. We largely followed the rules of thumb proposed by Green (1991) in estimating the necessary sample size for regression analysis to ensure there was adequate statistical power [

45,

46].

To implement the stratified random sampling, first of all, we divided the 21 cities in Sichuan Province into three categories according to the level of socioeconomic development, i.e., developed, moderately developed, and less developed. Among the developed cities, we randomly selected one city; among the moderately developed cities, we randomly selected three cities; and among the underdeveloped cities, we randomly selected two cities. As a result, the 6 cities, including Leshan (developed), Yibin, Ya’an, Suining (moderately developed), Nanchong, and Dazhou (less developed), were selected. The results are shown in

Figure 1 and

Table 1. The reason why we only selected one city among the developed cities and three among the moderate cities, instead of two from each group, is that this largely reflects the coherent structure of cities in terms of development level—this ensures the representativeness of the sample data. Among the 21 cities of Sichuan province, there are 11 middle-income while only 5 of 21 were developed and less developed cities, respectively. After the six cities were selected, we randomly chose three to six villages in each city and finally got 24 villages out of these six cities.

2.4. Survey Design and Data

The survey includes questionnaires from two groups. One group is the house owners, i.e., the owners of the vacant farmhouses. Thus, in this paper, sometimes we also refer to house owners as “farmers.” The other group is the urban residents, i.e., randomly selected urban residents who could be the potential buyers or the tenants of the vacant farmhouses. In the vacant farmhouse market, the house owners act as the suppliers, while the urban residents act as the demanders.

Therefore, the questionnaire was designed based on previous relevant studies. It contained five parts: Part 1 is about the respondent’s age, marital status, occupation, etc. Part 2 concerns the family situation of the respondent. Part 3 is about the basic situation of the vacant farmhouses for farmers and current housing conditions for urban residents. In Parts 4, we asked respondents about their understanding and perception of the rural homestead market. In the last part, i.e., Part 5, the respondents were asked about their willingness to participate in vacant real estate purchases in rural areas. The influencing factors and their importance were obtained through logistic analysis using data from the questionnaire.

It is noted that, in this paper, a “vacant farmhouse” refers to the completely vacant houses, instead of houses which have some vacant rooms. Also, the “vacant farmhouse market” includes both purchasing and renting these farmhouses. Because this market is quite undeveloped at present we believe both purchasing or renting can improve the utilization of these vacant farmhouses. Also, it is quite complicated if at all possible to buy or sell rural houses, as we explained earlier. So, during the interview, we asked the interviewees what their willingness was to buy/sell or rent in/rent out vacant farmhouses. In other words, we did not differentiate between the willingness to purchase or rent. A purchase in the future VFM was merely defined as a long-term “rental” unless the land tenure system would be completely reformed.

The survey was carried out and completed within two weeks in August 2016. As for the survey on house owners, we randomly selected 3–6 villages within each city. Some of these randomly chosen villages only have several vacant farmhouses, while some others may have up to 20 vacant houses. Since we aimed to survey the owners of vacant farmhouses, we could not expect to meet the owners by visiting these vacant houses. To solve this problem, we visited the village heads first in each village because, in China, the village heads generally know the situation for all the villagers and know how to contact them. From the village heads, we got to know how to find the house owners. For the house owners who have bought houses in the towns nearby, we visited their new houses and conducted interviews. For other house owners who were working in other provinces or could not be found in their new houses, we conducted the survey via telephone calls. The survey for urban residents was much easier. We went to these six cities and randomly selected 50 persons in each city to carry out the survey.

Data were firstly recorded on paper, then inputted into a computer database, and then cleaned for statistical analysis. A total of 600 questionnaires were distributed, of which 300 were house owners and urban residents, respectively. A total of 571 valid questionnaires were retrieved: 284 house owners and 287 urban residents with an effective response rate of 95.2%.