Abstract

The European Union is actively promoting the idea of “smart villages”. The increased uptake of new technology and in particular, the use of the internet, is seen as a vital part of strategies to combat rural decline. It is evident that those areas most poorly connected to the internet are those confronted by the greatest decline. The analysis in this paper is based on Poland, which at the time of EU accession had many deeply disadvantaged rural areas. Using fine-grained socio-economic data, an association can be found between weak internet access and rural decline in Poland. The preliminary conclusions about the utility of the smart village concept as a revitalisation tool for rural Poland point to theoretical and methodological dilemmas. Barriers to the concept’s implementation are also observed, although there is a chance they may be overcome with the continued spread of information and communication technologies in rural areas.

1. Introduction

In the past decade European countries have been undergoing a transformation towards an information society, and the changes taking place depend on global technological development. Rural residents are also a part of this process. Adjusting to the changes is not so much an opportunity as a necessity, as more and more types of activity are performed in the virtual world. This allows distances to be “reduced” and goods and services, especially public ones, to become more accessible. In this context, information and communication technologies are treated as a chance to overcome development difficulties [1,2,3,4,5]. However, their usefulness depends on the availability and quality of the internet. Its absence or poor accessibility deprives a given area of opportunities for smart development [6,7,8,9].

A new concept for rural development proposed by the European Commission is called “smart villages”. It is primarily aimed at villages that are declining due to remoteness and depopulation [10,11,12]. The first and most often repeated definition of smart villages comes from the document on the EU’s actions for this idea [13]. According to its authors, smart villages are those (local communities) that use digital technologies and innovations in their daily life, thus improving its quality, improving the standard of public services and ensuring better use of local resources. The document by the European Network for Rural Development (ENRD) underlines that a smart environment is created by people, and their main objective should be to find practical solutions to the main problems they face. It can be said that the EU promotes support for the development of areas in decline by using digital technologies and innovations. By engaging in a discussion on the concepts that have only just been formulated, the question can be asked whether these areas have the capacity for smart technology-based development. The authors assume that smart villages “begin” with an analysis of the use of digital technologies to create a space in which it is easier for local leaders to take account of the needs and capabilities of the inhabitants. Adopting such an approach makes it possible to consider the elements necessary for this process. The authors believe that the sine qua non is access to the internet.

The accessibility of the internet is spatially differentiated. The question is about its scale and nature. So where does the smart-village concept stand a chance? The decline in rural areas is characterised by the lowest level of socio-economic development, the following hypothesis will be tested: the lower the level of rural development, the lower the internet accessibility. This makes it more difficult to implement the smart-village concept. The implementation of such a defined objective will take place in three stages: (1) tracing changes in the rural population in Poland in relation to the level of socio-economic development; (2) identification areas of internet infrastructure deficiency and verification that they overlap spatially with areas of the lowest development level; (3) determining what smart villages are or are meant to be, what they should be like in the future, and what resources rural areas need to support activities fostering such initiatives in the EU’s future financial framework.

The beginnings of the smart village concept date to the middle of the last decade, when a vision of smart rural areas was presented by T. van Gevelt and J. Holmes [14] on the basis of activities already pursued in this area in Africa and Asia. Due to substantial developmental and structural differences between rural areas in those regions of the world and rural areas in Europe, the concept is understood a little differently in the EU, also in view of its objectives and the instruments used in its implementation. An important document giving direction to smart village initiatives in Europe appears to be the above-mentioned the EU Action for Smart Villages [13], planning specific actions aimed at putting the idea into practice. What has become the driving force of the discussion on smart villages, however, is the vision of “a better life in rural areas” outlined in the 2016 Cork 2.0 Declaration [15], in which one of the challenges for EU policies for the development of rural areas was described as follows: “to overcome the digital divide and develop the potential offered by connectivity and digitisation of rural areas” (p. 3). The Rural People’s Declaration of Candás Asturias [16] from late 2019 underlines the necessity to support smart initiatives as part of EU policies. The development of “smart rural villages and towns” is also recommended by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in its rural policy-making principles [17] (p. 7). The great role of digital technologies is also highlighted by F. Bogovic and T. Szanyi, who view the concept’s development and practical application as a chance to ensure an easier and better life for rural residents, adding that it is necessary to respond to the problems created by the ageing of society and a shortage of services [10]. Another underlined aspect of smart villages is the idea’s territorial sensitivity, enabling any projects to be adjusted to local circumstances. The virtue of the concept’s possible broad application is at the same time a drawback whenever we try to say what a smart village really is (or can be) (see Section 3.3 and Section 4). The authors of the present paper see this issue as a general challenge, not just for the institutions that plan the development but also for the scientific community, its task being to deliver knowledge that best describes reality.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

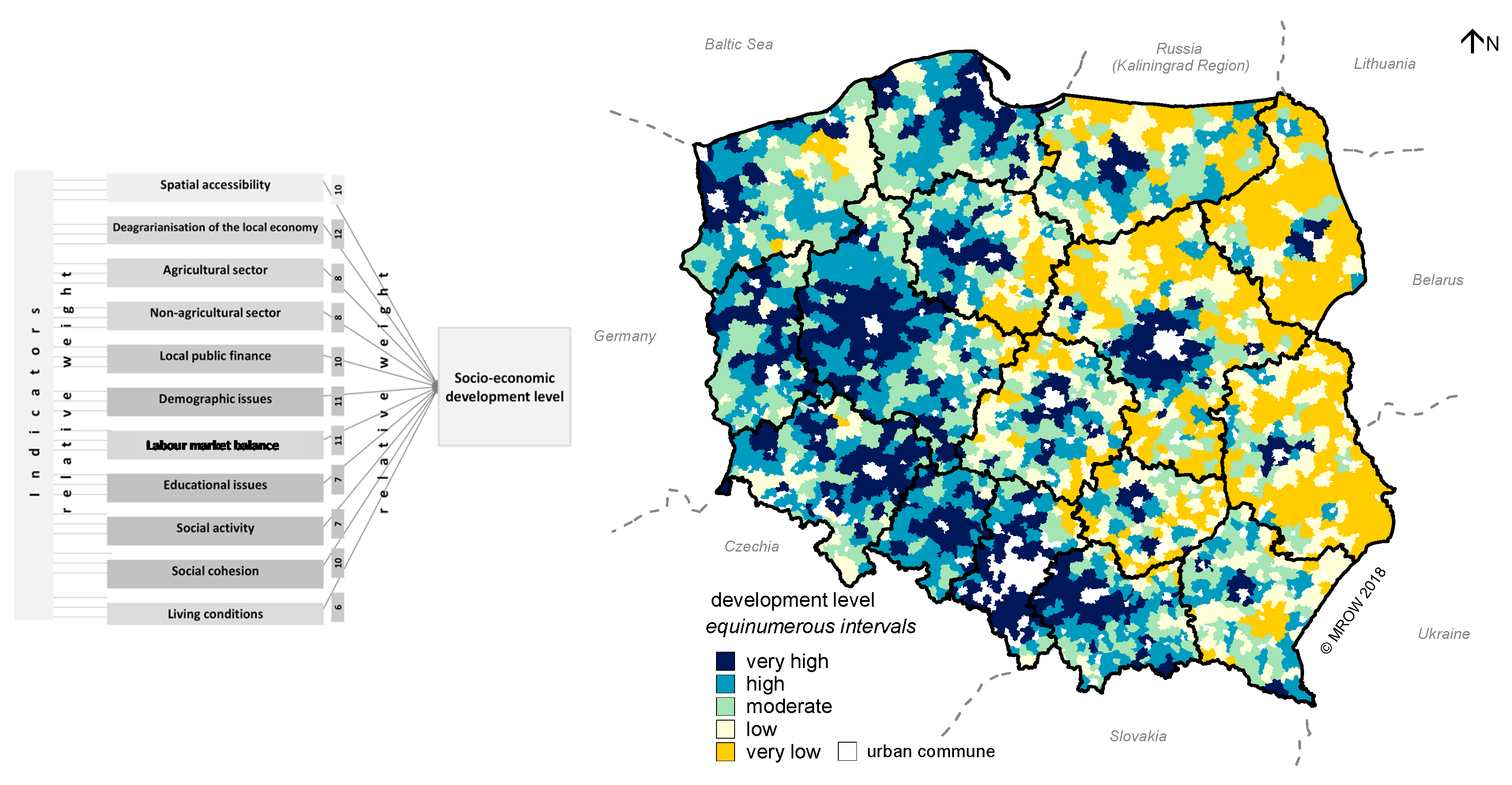

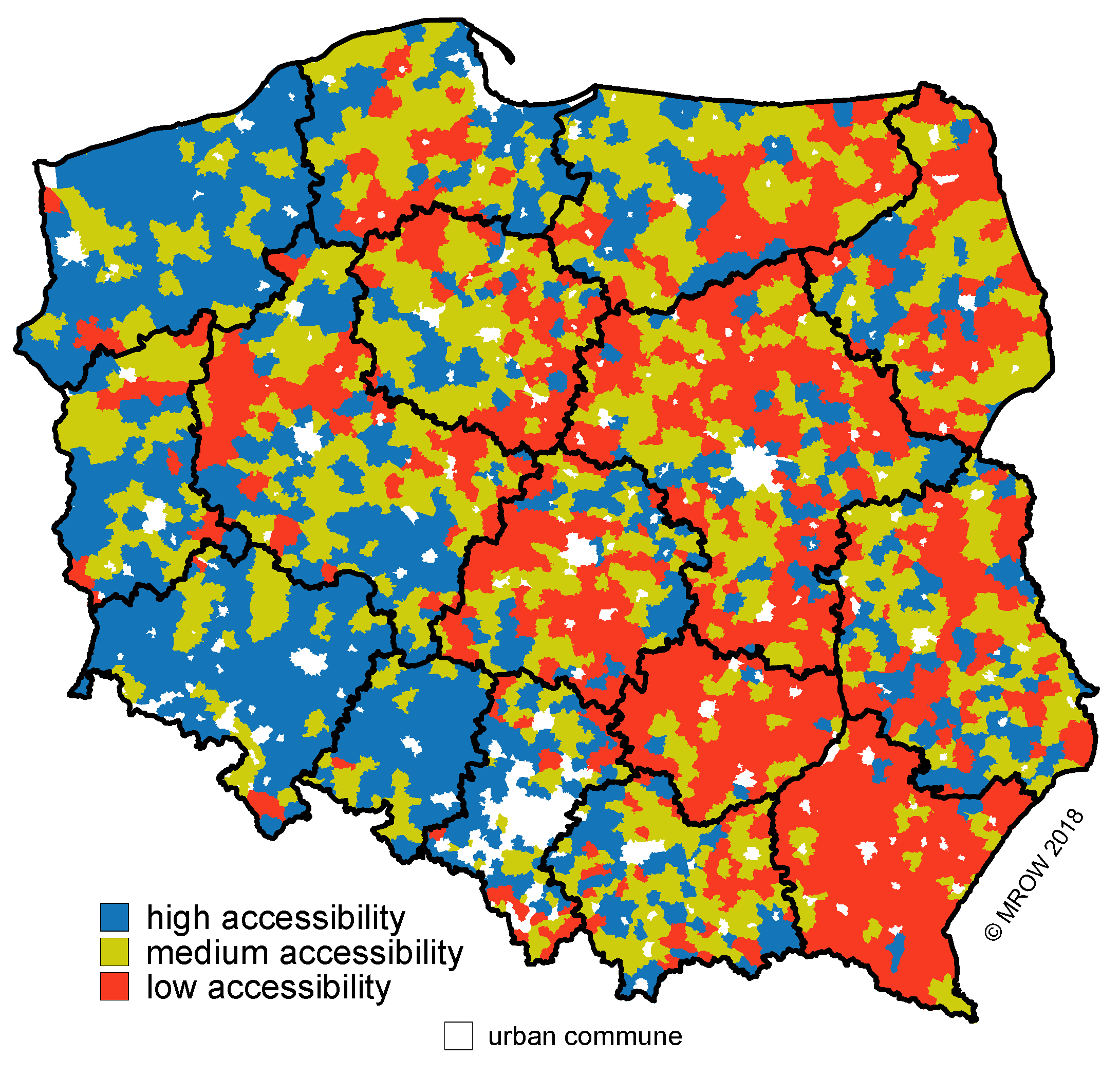

The analysis was carried out for rural areas in Poland, which show great territorial differences in the socioeconomic development level. This is the effect of historical (19th and 20th centuries) circumstances related to Poland being partitioned among three powers (Russia, Prussia and Austria) as well as socialist state policies for rural areas that were pursued until the fall of communism in Central and Eastern Europe in 1989 [18]. Efforts to make up for infrastructural backwardness in rural Poland did not really take off until the country joined the EU in 2004. The social and economic structure of rural areas is still heavily influenced by the economic power of regional cities, which drains the demographic potential from areas far from urban centres. The scale of these differences is well illustrated by the results of research conducted in Poland as part of the Rural Development Monitoring (MROW) project [19,20] (Figure 1). In order to see the true scale of these differences, it is advisable to consider the lowest level of spatial aggregation, i.e., the local structure. In Poland this requirement is met when data are considered for the gmina/commune (local administrative unit) level, based on the current administrative division (in this case from 2019), taking into account rural communes and the rural segments of urban-rural communes (2175 local administrative units—LAUs). By “rural areas” in Poland we mean areas lying outside the administrative boundaries of towns/cities [21].

Figure 1.

Synthetic measure of socioeconomic development level in rural areas in Poland1. Source: [20] (p. 16; 219).

2.2. Data Collection

The authors took advantage of public statistical databases available in the Local Data Bank of Statistics Poland (BDL GUS); in the field of “population”: total commune population (2005–2018); in the field of “communications”: land-line telephone subscribers (1995–2018). In addition, they used periodical publications of Statistics Poland (GUS)—statistical yearbooks and information society surveys to obtain data on the number of households with an internet connection (2005–2018). Since the amount of published statistics on information and communication technologies is limited (and available only at the voivodeship/province level), the authors also used data on internet accessibility in rural areas made available by the Office of Electronic Communications (UKE) for the Rural Development Monitoring (MROW) project. Results of MROW research project on the socioeconomic development were used as well. These data are not accessible through open repositories, hence the results of research conducted at the local level on their basis can be considered of great interest for territorial development.

In the study, quantitative methods have been used:

- -

- Thematic (choropleth) maps to show the spatial differentiation of the phenomena;

- -

- Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to identify the interdependence of the ordinal data;

- -

- Time-series analysis to observe and interpret trends;

- -

- Contingency tables to summarize the interrelatedness between variables.

2.3. Content Analysis

The authors of the present paper have carried out a broad analysis of scientific studies on the smart-village concept and broader rural development issues (in the context of demographic processes) as well as other publications: documents, declarations, reports, notes (see Section 3 and Section 4). This desk research suggests that the main group of sources are documents drawn up in connection with the planned smart-village concept (including by the European Network for Rural Development and the European Commission). The authors also used the participant-observation method, taking part in the 9th and 11th meetings of the ENRD Thematic Group on Smart Villages; study visits were undertaken in two Finnish localities vying for smart-village status; at the 4th European Rural Parliament in Candás (Spain)—taking part actively in workshops on the smart-village approach—and within the framework of the group developing the Common Agricultural Policy Strategic Plan for 2021–2027 (smart villages section). The authors were also responsible for holding Poland’s first My SMART Village competition to choose villages undertaking smart initiatives.2

3. Results

3.1. Rural Decline: Where is the Problem?

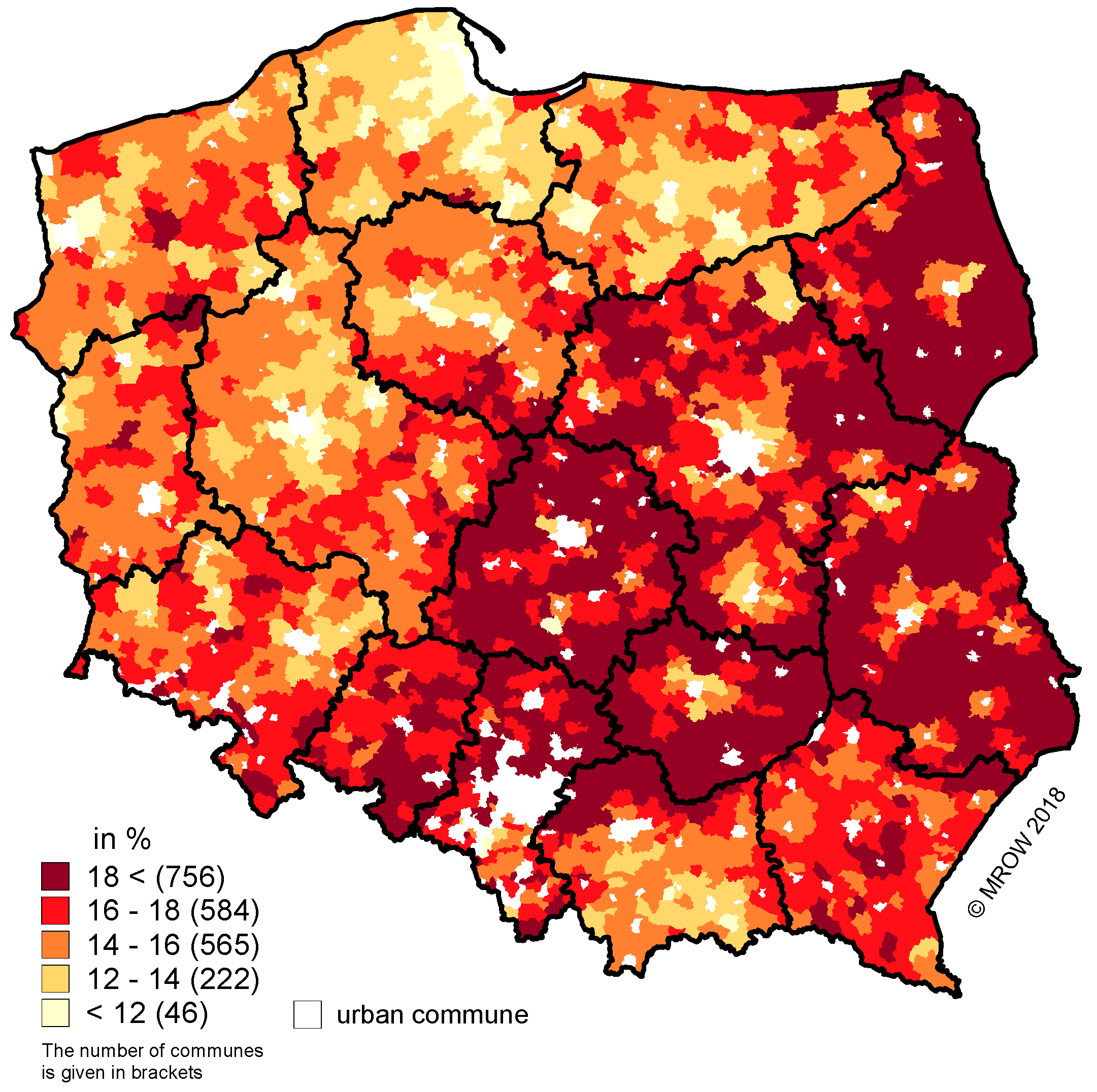

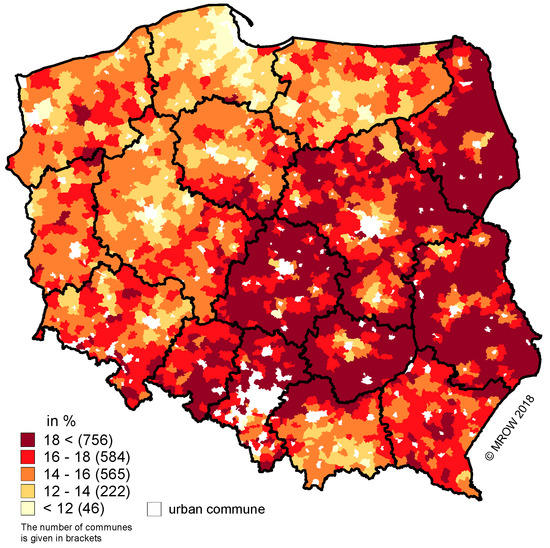

Demographic processes (internal migration above all) which shape the demographic and social/occupational structure of the rural population today are key factors determining the socioeconomic development of a given area. With the exception of suburban areas, in most European countries including Poland rural areas are becoming depopulated (the rural net migration rate is below zero), and the low birth rate (often close to zero) is unable to compensate for the population decline [23]. This relationship between the components of actual population growth is leading to the rural depopulation and consequently to the rural ageing. The existing demographic structure affects the functioning of entire local communities in aspects such as education, the labour market, healthcare and other public services. It is this last aspect that is currently at the focus of the discussion on adapting services to the needs of an ageing society. In Poland this problem is most often limited territorially to the central-eastern regions, in which rural residents are the oldest in Poland on average. Among the demographically oldest 100 rural and rural-urban communes, more than half are located in the east of the country, in Podlaskie province, and one-third are in Lubelskie province. The median share of people beyond retirement age in the overall commune population in this group is 24%, seven percentage points more than in Poland as a whole. These are relatively mono-functional agricultural areas with a permanent outflow of people. The depopulation process had already been diagnosed there in the 1980s [24]. Figure 2 confirms that the suburban areas of regional centres are relatively young, indicating a steady outflow of young residents from peripheral communes. The demographically youngest rural communities are found in western Poland, in Pomorskie province in particular. Such a perceptible territorial diversity of the population’s age structure is—similarly to the diverse level of development—a consequence of two main factors: historical circumstances (post-World War II resettlement) and the polarisation of regional development (an outflow of residents from peripheral areas to the suburban zones of big cities) [25]. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of these two spatial trends is rho = −0.600, i.e., the most underdeveloped areas are usually demographically old (cf. Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of rural residents at retirement age in the total commune population. Source: [20] (p. 116).

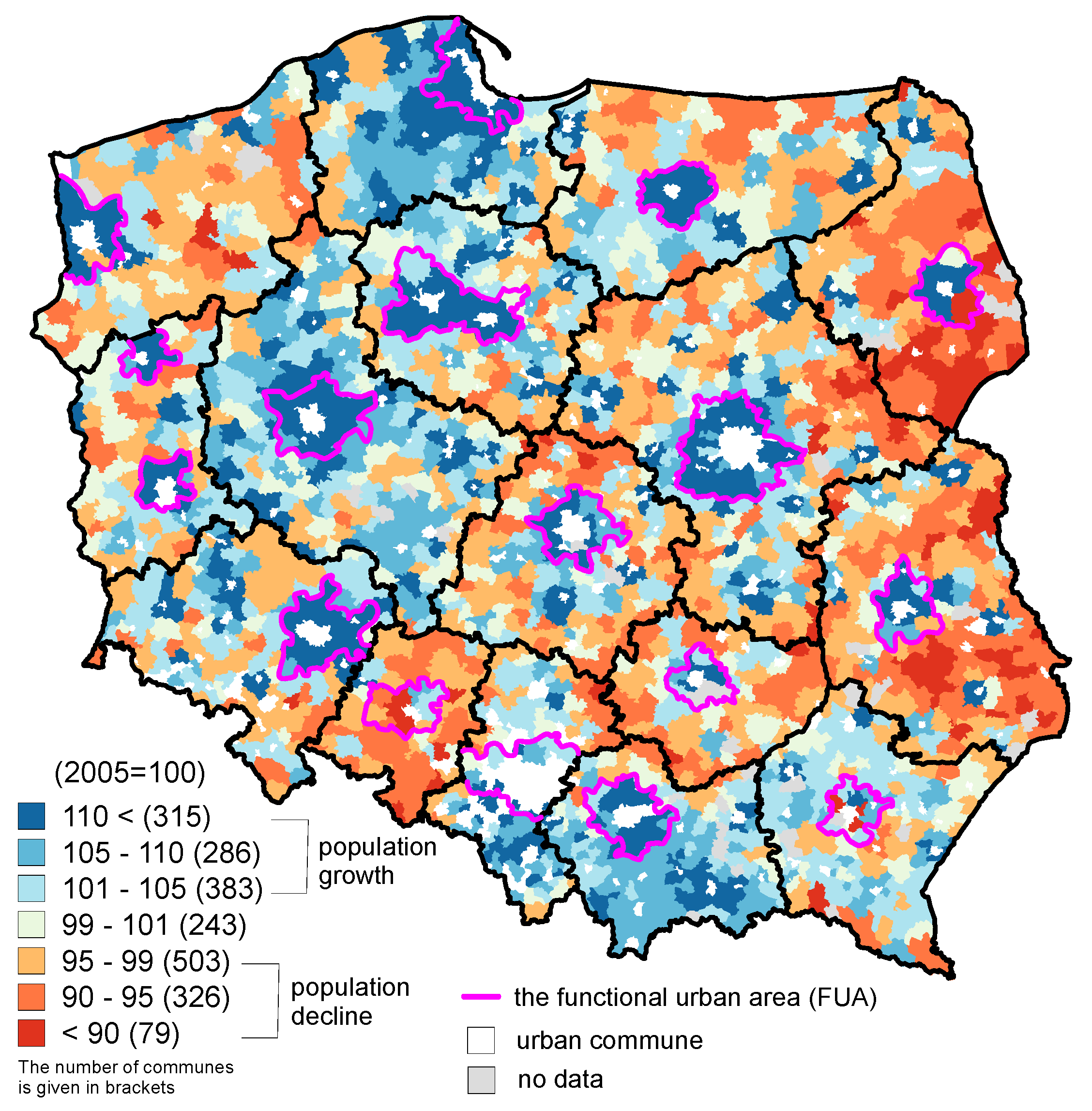

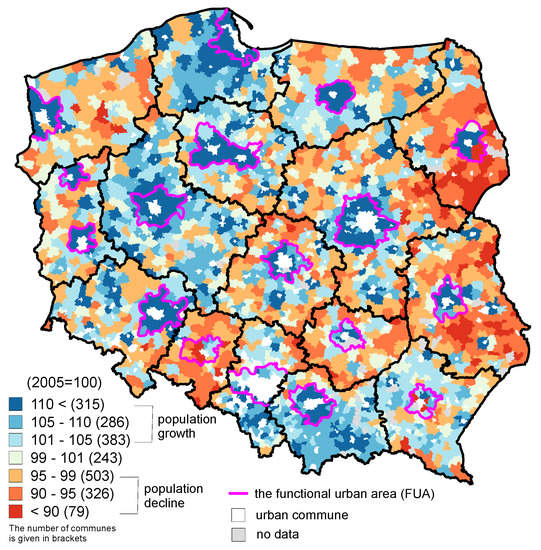

Poland’s regular Rural Development Monitoring (MROW) survey confirms that migration is a “silent moderator” of social and economic changes in rural areas [20] (p. 258). These changes can also be the result of a certain inertia of development in a given area, and at the same time a cause of further changes—both positive (in areas with immigration) and negative (in areas undergoing depopulation) (Figure 3). The emigration of rural residents drives the vicious cycle of collapse (underdevelopment), which can be described by cause-and-effect relations strengthened by negative population trends in many rural areas (more: [26,27,28,29]). Awareness of this process is even more important, as population changes are strongly interdependent with the level of rural development. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient is rho = 0.700 (cf. Figure 1 and Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Rural population change in 2005–2018. Source: own work based on the Local Data Bank of Statistics Poland (BDL GUS) data and [34] (p. 196–197).

Population changes recorded since Poland’s accession to the EU deepen the tendencies observed for the beginning of the country’s urbanisation process, which accelerated in the 1950s [30]. Areas where the population is increasing cover about one-third of rural and urban-rural communes in Poland and these are mainly suburban zones around large regional centres. Nearly 90% of communes located within the boundaries of functional urban areas (FUAs)3 in provincial capitals show the highest population growth. These are areas of long-term immigration.

Increasing the number of inhabitants of rural areas takes place not only within the range of influence of provincial capitals but also around cities of subregional importance. However, it is a tendency determined by historical factors and more often characterises the cities of western rather than eastern Poland. In regional terms, the greatest increase in the rural population is observed in the communes from the Pomorskie, Podkarpackie and Wielkopolskie provinces. These regions are inhabited by indigenous people, with traditions of circular migration, relatively culturally (ethnically) homogeneous, with a strong sense of what is known as land attachment [32].

The communes with the deepest, permanent depopulation are located on the “eastern wall” (Podlaskie and Lubelskie provinces). The others are scattered along the provinces’ borders of central Poland. The deep depopulation also enters the areas of what are known as the Western and Northern Lands, incorporated into Poland after World War II. The region underwent a profound economic transformation in the 1990s, which, however, did not stop the emigration. After Poland joined the EU, it was mainly emigration to Germany and Great Britain [33]. This problem concerns Opolskie province in particular.

The falling number of residents (“tax base”) as a result of emigration reduces local-government budgets, leading to difficulties in providing day-to-day public services (e.g., in transport or culture). It also causes local authorities to hesitate to undertake infrastructure projects improving residents’ lives and increasing a locality’s attractiveness to prospective investors. Given the low number of potential users, this translates into high maintenance costs for such projects. A lack of economic stimuli then leads to relative mono-functionality of the local economy’s structure, based on farming. A poorly developed labour market increases emigration, but such emigration is selective: those leaving are young people, women more often than men [35,36,37]. This in turn negatively affects the structure of the remaining population, now dominated by people at retirement age. The population density decreases, the distances between homesteads grow, which further exacerbates problems in providing services and necessary infrastructure. This system of inter-related events leads to loss of rural vitality, the consequence being rural decline [28].

The process of depopulation, although in a sense inevitable, encourages the scientific community and all the rural stakeholders to seek solutions that would limit the negative effects of emigration and its socioeconomic consequences. This has led to increasingly frequent questions about instruments that could be used to intervene at the present time as well as enabling the prevention of future problems caused by existing demographic trends (see: [38]).

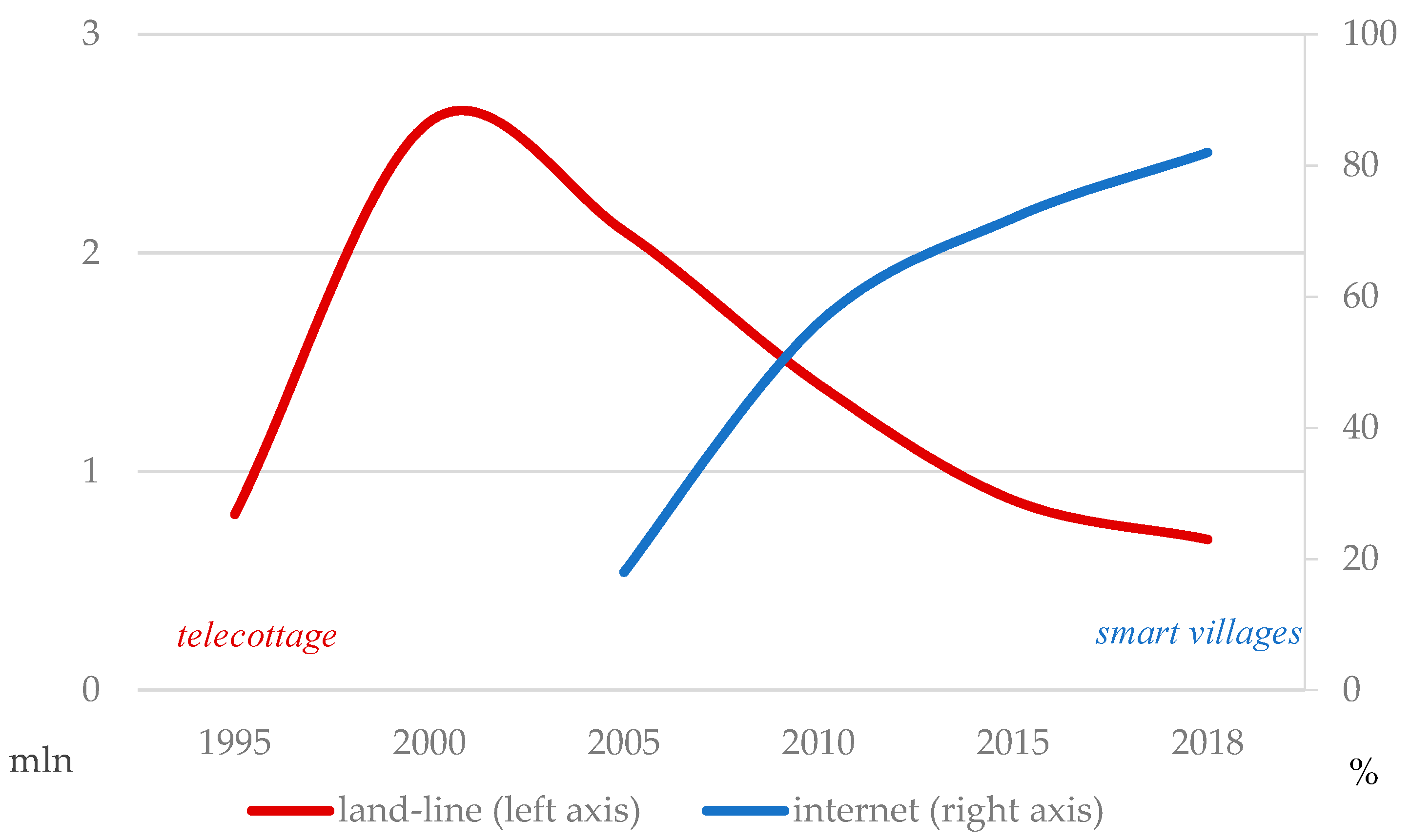

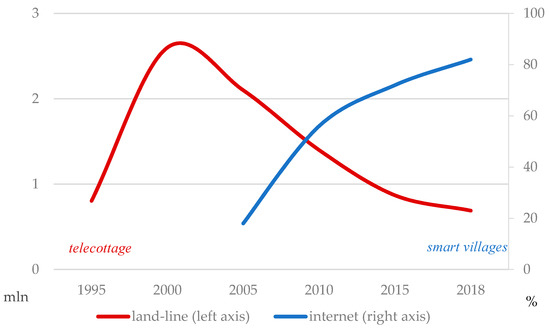

3.2. Development of Information and Communication Technologies in Rural Areas

The measurable benefits of using state-of-the-art forms of telecommunications, which by their nature help overcome many inconveniences of the rural living, were already noticed in the 1980s and 1990s [39]. The purpose of new means of communication was to reduce the distance to public services, e.g., health care, educational, cultural or recreational services. Using technical innovations such as—at the time–telephones, faxes and non-portable computers was meant to contribute to halting rural outmigration and to revitalise rural areas experiencing infrastructural backwardness. The instrument promoted at the time was the telecottage—a local telecommunications centre equipped with the latest telecommunications tools, made available to residents and entrepreneurs to meet informational, cultural and the work-related needs [40].

The first telecottage was set up in the mid-1980s in Sweden. It was intended as a response to the growing ‘brain drain’ process. A joint initiative of the Swedish government, the local authorities and scientists, it revived the local community cut off from the outside world, enabling residents to acquire new skills (transit to an information society), launch collaborations and stimulate enterprises [41].

In the following years the Swedish idea was adapted elsewhere, initially in the Nordic countries and later also in the west of Europe and in Hungary. In the mid-1990s Poland also saw a similar initiative, involving a telecommunications centre in Kujawsko-Pomorskie province, but the idea was never put into practice [40]. It seems that 30 years ago it was a concept which in Poland’s case was ahead of its time, especially in terms of infrastructure requirements. It was not until the late 1990s that rural areas were speedily supplied with land-line telephones, but then other technologies (computers, mobile phones, the internet) rapidly supplanted this form of communication [42]. The evolution of telecommunications in rural Poland is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Rural land-line telephone subscribers and rural households with internet access. Source: own work based on BDL GUS data and [43,44] (p. 437, p. 327).

According to GUS data, in 2018 84.2% of Polish households had internet access, most of them via a broadband link [44] (p. 327). The difference between urban and rural areas was a mere 3.3 percentage points, although in 2005 access in cities had been twice as high (36% compared to 19% in rural areas) [43] (p. 437). Public statistics on spatial differentiation in internet access is only available at the provincial level, without a division into cities/towns and rural areas. These data show that the situation was the worst in provinces of central and eastern Poland, i.e., the part of the country with the highest percentage of less-developed communes (cf. Figure 1.).

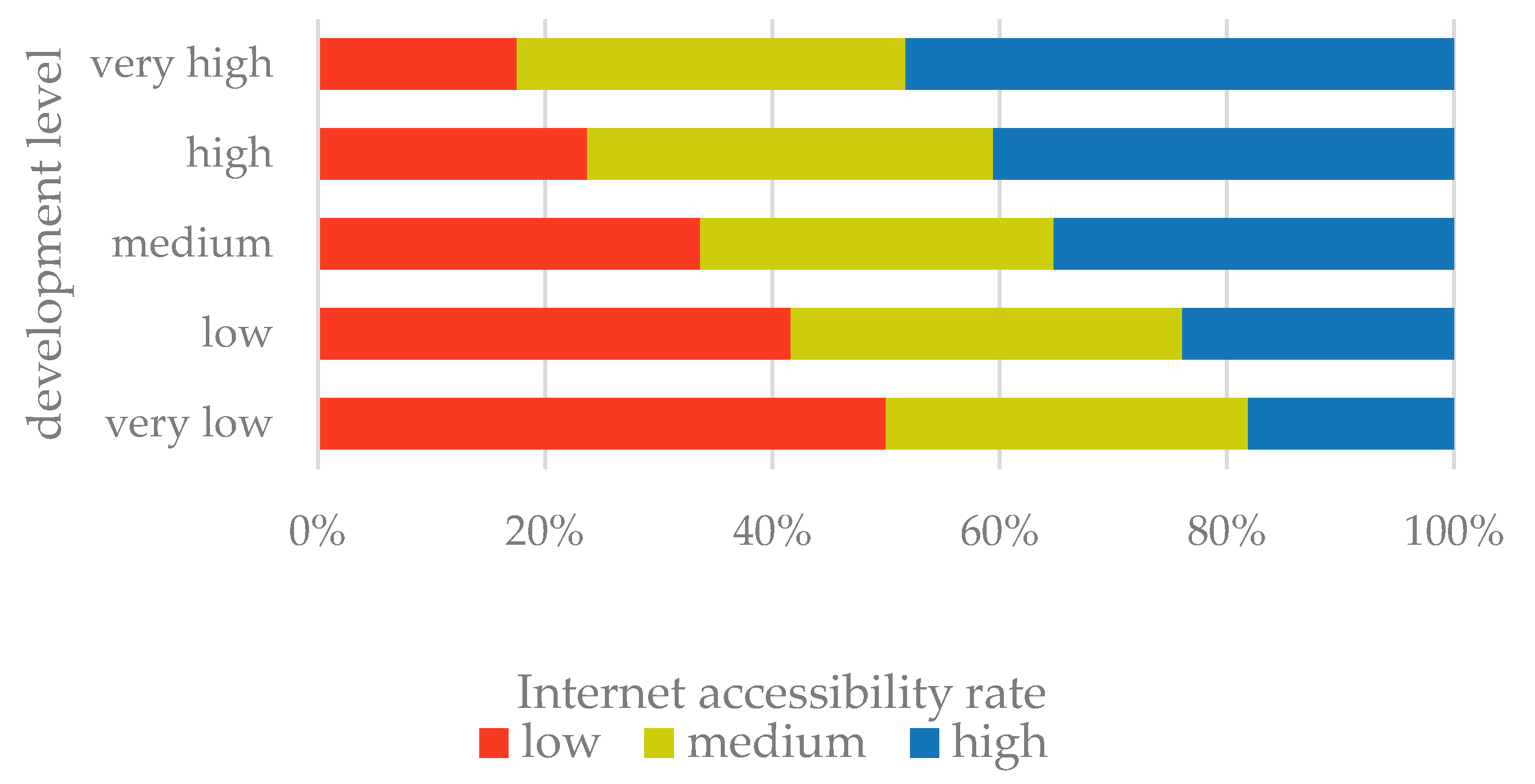

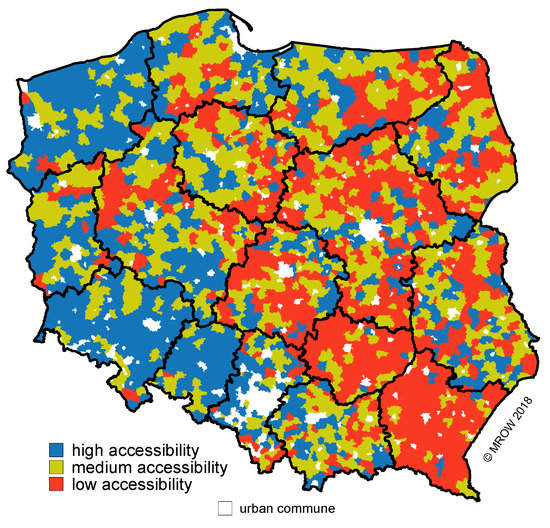

A little more information is provided by data from the Office of Electronic Communications (UKE) aggregated to the local level (Figure 5). It shows that the most basic measures—internet accessibility—have large inter- and intra-regional differences. The technically most developed base is found in the western regions, some areas around big cities, and isolated areas in the rest of the country. On the other hand, the least developed internet infrastructure measured in this way is found in south-eastern and central Poland and, with a few exceptions, in the east of the country.

Figure 5.

Internet accessibility rate in rural areas4. Source: own work based on UKE data.

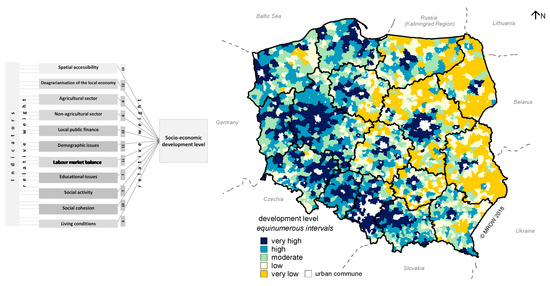

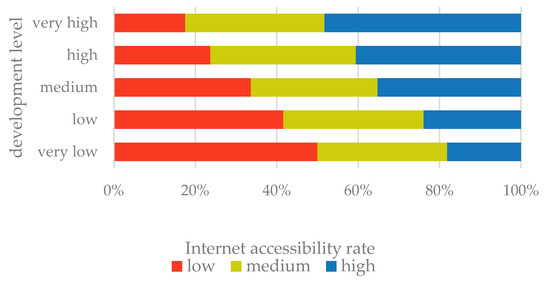

The interdependence of the accessibility of internet infrastructure and the level of socio-economic development has been confirmed statistically. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient is rho = 0.300 and is statistically significant (cf. Figure 1 and Figure 5). It is not a strong interdependence; however, it should be remembered that it is calculated for the full set of communes (N = 2175). It is therefore justified to conclude that with the increase in the level of development, the provision of ICT infrastructure in rural areas also increases. The verification of this relation in five development levels (as in Figure 1) has shown that only one in five communes with a low or very low level of development have a high level of internet accessibility. However, one in two of the communes in the category with high and very high levels of development also have the highest level of internet accessibility (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Internet accessibility rate structure according to socio-economic development level. Source: own work.

Insufficient internet access is a problem that rural communities often try to solve when dealing with local authorities. The basis for such a conclusion is provided by the Communes Survey,5 carried out as a part of the Rural Development Monitoring (MROW). The topic of internet access is discussed with village leaders in two out of three gatherings and meetings. However, as calculated by the authors the weaker the access to the internet the more often is this issue discussed: in 70% of cases in the low-access class and 58% in the high-access class. This shows that the financial needs of the villages are still in many cases focused on “hard” projects. The allocation of funds for digitisation of rural areas under the Digital Poland 2014–2020 Operational Programme (co-funded by the EU) is a reflection of this and, at the same time, an opportunity to overcome the infrastructural barrier. By February 2020, contracts for tasks of about €3bn had been signed [45]. The programme implementation plan assumes that about 37% of the total allocation will directly cover rural areas [46] (p. 53).

3.3. Smart Village, Meaning What?

Insofar as the telecottage idea emerged too soon for the technical (and awareness-related) possibilities of rural Poland, the currently discussed concept of smart villages appears to fit in well with current circumstances. The recommendations on the smart village idea recently developed in a collaboration between the Polish Rural Network (KSOW), the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, rural residents and researchers suggests some answers to the earlier question of what a smart village is (can be). These recommendations state that for the successful implementation of the concept, we need to [47]:

- Build on experience, on the basis of existing forms of collaboration, often long-term and successful, for example related to rural revival or the LEADER approach. The concept should not be allowed to become bureaucratised.

- Start from one village, but build partnership. Smart-village projects have to respond to the needs of local communities, even if they are in small localities. Advisory support in finding funds should be obtained from units specialising in consulting.

- Account for the digital backwardness of rural areas. Although smart villages, unlike smart cities, are not based solely on new technologies, rural residents’ basic access to a (fast and stable) internet network is crucial for local development. Appropriate competences are also important.

- Appreciate people’s activity. The smart-village approach should not be planned without the involvement of local leaders, local government, NGOs and other stakeholders. Existing resources should be utilised, such as active village heads and other local leaders.

- Reward active attitudes. To promote the smart-village concept, it is worth showing rural communities the potential benefits of its implementation, for example with the help of identified, existing examples of smart solutions.

- Make sure the smart-village concept helps small farms. Agriculture is a large area for developing the smart-village concept, as it uses advanced new technologies more and more often. Together with stimulating cooperation among farmers, this creates chances for the development of this segment of the economy, also in places where farming is fragmented and seemingly in decline.

- Involve the consulting sector in supporting smart ideas of local communities. New technologies should be used to develop consulting services, which should ultimately become innovation brokers.

The fact that smart villages are not a fully developed or researched concept is reflected in the small number of scientific studies on the issue. The great majority of such publications are overviews, due to the fact that work still continues on determining what smart villages are (or will be), what they should be like in the future, and what instruments would be used for their implementation in the EU’s future financial framework [48]. The concept is often criticised for its lack of scientific foundations, although some authors have sought to place it within some kind of theoretical framework [49,50,51,52,53]. B. Slee remarks that “the evolution of support for community level development generally and what are termed smart villages has happened almost without reference to theory” [51] (p. 645). He situates the smart-village concept in regional development theories (centre-peripheries), Florida’s creative classes, or Putnam’s social capital theory. A. Davies considers the ties between smart technologies, political strategies and the vitality of the rural population in the context of the Internet of Things (IoT) [53]. A different approach is offered by M. Zwolińska-Ligaj, D. Guzal-Dec and M. Adamowicz, who have tried to operationalise the smart-village concept. However, they also conclude that such an approach “creates many problems in the way research reflects new factors of development” [54] (p. 271), and point to the weakness of data from public statistics related to innovation and technological changes on the local level.

The authors also wish to contribute to these deliberations, offering their own theoretical analysis. We would like to suggest considering an analogy between the smart-village concept and the concept of sustainable development. The analogy has also been recognised by other researchers (more: [50,55,56]). Both these approaches seek a compromise between environmental, economic and social goals, consisting in a game of limitations in utilising all forms of capital. It involves improving residents’ quality of life (the social order) while necessarily optimising current economic benefits for households as well as local government and businesses (the economic order) and ensuring continual nature and landscape protection (the environmental order). It seems that some years ago sustainable development was—and today smart villages can be—a concept invoked in legal regulations, political documents and development strategies at different management levels (e.g., Poland’s National Regional Development Strategy 2030, adopted in 2019). This could be a “daughter concept” seeking harmony among three components: the natural environment, the economy and society, highlighting the social factor in the name of social justice, access to services, standard of living, life surroundings and wellbeing. It is already a concept based on overcoming territorial barriers (reducing distances) experienced by rural residents when accessing public services, in order to create a responsible and desirable living environment.

4. Discussion

Some researchers believe that the smart-village concept draws upon the equivalent concept of smart cities [49,57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. However, the problems faced by urban and rural areas seem to be completely different, therefore the solutions proposed during implementation of these two approaches are also different. The authors of one study on smart villages conclude that one of the biggest challenges is how to overcome the emigration from rural areas to conurbations, and ask a fundamental question: “what smart services, provided by whom, how and at what cost could be provided to ease the situation?” [63] (p. 3). In this context, it seems equally important to ask not only about the scope but also the means of providing such services.

In the context of areas struggling with problems caused by negative demographic trends, we can speak of smart solutions in three aspects: public services, public management, and economic activity in a broad sense (Table 1).

The first group includes services provided mainly in traditional forms by local government. The steadily diminishing population, decreasing population density and increasing percentage of the elderly will reduce the financial capacity to continue these services. On the other hand, demand for some specific services, e.g., related to healthcare or elderly care, will grow. L. Philip and F. Williams [64] noted this in their study, mentioning such solutions as digitally supported communication platforms or assisted living technologies. This forces us to think about how to meet these needs, and new technologies are one of the tools proposed in development policies being drafted for the coming years [65,66]. Apart from solutions for basic social services, the idea of smart villages also envisages using innovative solutions in transport and power supply.

Table 1.

Examples of smart actions in rural areas.

Table 1.

Examples of smart actions in rural areas.

| Smart Solution Group | Public Services: | Public Management: | Enterprise: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Areas of intervention | power supply (e.g., RES) | e-administration | precision agriculture |

| safety and security (e.g., visual monitoring) | waste management (e.g., container fill-level sensors) | online trade (e.g., in local products) | |

| distance learning | town-and-country planning (e.g., digitisation) | rural tourism (based on smart solutions) | |

| transport (e.g., telebuses) | environmental monitoring (e.g., air quality sensors) | sharing (e.g., of specialist equipment) | |

| e-care | |||

| e-health |

Source: own work based on [67] and materials from meetings of the European Network for Rural Development (ENRD) Thematic Group on Smart Villages [68].

The second group of smart solutions is intended for the public administration. The solutions that seem especially important from the point of view of the rural areas being considered here are those designed to rationalise the performance of some of its tasks, e.g., in waste management. Equally important, although requiring greater involvement and skills from residents, are e-administration tools, which research has shown are still inadequately developed in Poland, partly due to barriers of awareness in society [69,70].

One important objective of smart villages is not just to uphold the vitality of depopulating areas but to revitalise them as well. The solutions proposed here are related to farming itself as well as to other economic sectors not linked to agriculture. Enterprise in a broad sense is the least identified and, it seems, most difficult area of implementation. It depends on many aspects that are of a highly individual nature (impossible to standardise), such as businesses’ financial resources, competences as well as residents’ needs.

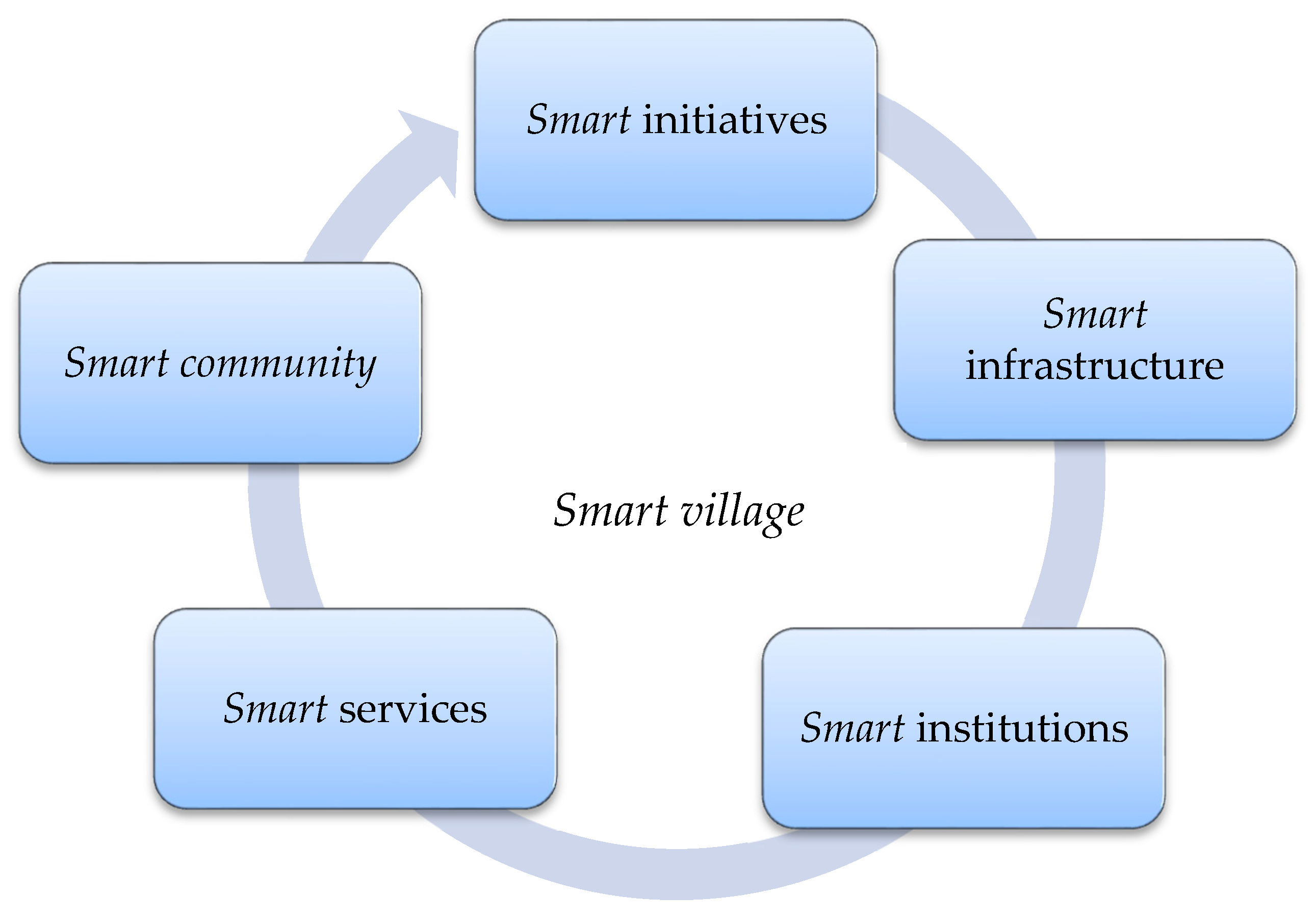

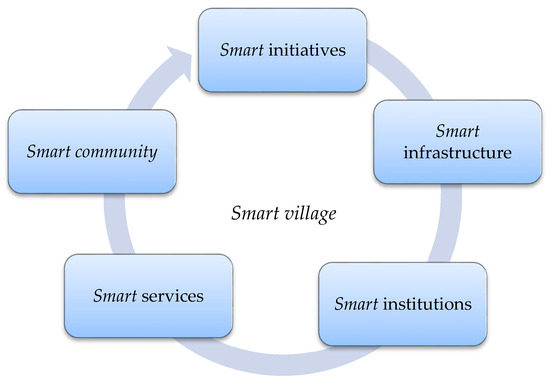

For the smart-village concept to function it requires the harmonisation of several elements: initiatives and collaboration aimed at proposing new solutions, necessary infrastructure related to information and communication technology, institutions activating and coordinating the work, and finally, the provision of services which would respond to the needs of local communities on the one hand, while enabling local authorities to alleviate the effects of emigration on the other (e.g., by reducing the cost of providing services). Implementations of the concept carried out so far, however, show that the above elements will not become reality without appropriate competence, skills and changes in rural residents’ perception of new technologies (awareness of the need for them)—this applies both to the recipients of smart solutions and to the people and maybe even institutions that will provide those solutions.

These requirements appear in the plans to support smart villages in the future Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), among others in Finland [71] and Poland [72]. In both countries support is planned in two ways:

- At the national and regional level, where projects in basic infrastructure (e.g., broadband), development of e-services for different economic sectors (e.g., tourism, agriculture, public health) will be financed. In addition, the environmental component of such projects will be mandatory—thus, national authorities also see an analogy between smart villages and sustainable development.

- At the level of local communities, ideas and strategies of individual villages, their clusters or local action groups (LAGs) are to be supported. The scope of support will depend on the bottom-up smart-village concept” proposed (especially highlighted in Poland).

The link between these levels of support can be provided by what are called innovation brokers, selected from LAGs and national rural network structures. Thus the initial government proposals take into account, to a certain extent, the elements of smart villages: both the basic ones (such the ICT infrastructure), but also those related to the expertise and activity of the rural residents, above all their leaders (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Main elements of smart village ‘space’. Source: own work based on [73] (p. 441).

GUS data from 2019 [74] indicate that, of the people who do not use the internet on a daily basis, as much as 68% see no such need and over half justify it with their lack of skills. This is hard to imagine, however, when we see how common smartphones or notebooks have become as elements of the daily lives of the Polish and, more broadly, the European population, offering online access to all kinds of resources. Excessive costs of ensuring internet accessibility are indicated by a fifth of those polled, while some 14% cite overcoming an aversion to the internet as a barrier (p. 2). The results of the Social Diagnosis from 2015 enable us to conclude that rural residents’ competence in using the latest devices is increasing, including among the elderly [75]. There are also other studies indicating that this group uses new technologies increasingly often and has a more positive attitude towards them [76,77]. The need to digitise rural areas has been recognised in research carried out in other countries, to mention the United States, Germany, Italy and Slovenia [60,78]. At the same time, access to fast internet networks is just one link in the entire chain of a process that also includes issues of adapting to the new technologies and matching smart solutions to the needs of local communities. It needs remembering, however, that in practice the implementation of the concept in question could take a dozen (or a few dozen) years, which means that the potential beneficiaries will be people who already function very well in a world based on new technologies.

5. Conclusions

The attention of rural stakeholders is turning to the concept of smart villages, an idea that raises great hopes for improving rural residents’ standard of living. Successful development based on the concept of the smart village is conditional on relatively good access to the village internet. Without it, there is no access to digital technologies and further to smart initiatives based on digital solutions. Research has shown that only one in five communes with a low or very low level of development have high internet access. At the same time, more than half of the rural areas facing decline have a low level of accessibility to the internet infrastructure (which may also sometimes mean a lack of it). The authors confirmed the hypothesis that with the decrease in the level of development the provision of ICT infrastructure in rural areas also decreases. Although research on smart villages is not yet advanced, it would seem that given the possibility of such solutions being co-financed from European funds, the main barrier to implementing the idea are a lack of skills and confidence in new technologies among people who do not use them on a daily basis. As data on rural residents’ access to and use of computers, the internet or smartphones suggest, however, innovative solutions are increasingly being used by people who will become beneficiaries of smart initiatives in the coming years. It is worth underlining that the competence of entities responsible for local development will be equally important for smart villages to be a success.

In view of the above, we posit that the smart-village concept should not be limited to the conditions created by developing technologies, but should be more open, i.e., receptive to social innovations. By these we mean not only introducing unique solutions but also implementing already existing ones, albeit in a new social context—an ageing society or rural decline. The solutions in question are intended to respond to the needs of a specific local community as well as to lead to lasting, positive changes in a given social group. This can involve innovative products, smart services or processes enabling different solutions to be found for typical social problems in local communities, in line with the motto “a better life in rural areas” [15] (p. 1).

We see a certain analogy between the smart-village concept and the sustainable-development concept. In both these concepts, attention is drawn to maintaining a balance between the economy, society and the natural environment. This should improve the quality of life of residents but take account of current economic benefits of different groups as well as the environment they live in. In this context, it is worth mentioning U. von der Leyen’s declaration on measures aimed at adjusting to the digital age: “I want Europe to strive for more by grasping the opportunities from the digital age within safe and ethical boundaries” [79] (p. 13).

The issue outlined here leads to one more observation: that the smart-village concept is not completely new. Similar ideas to take advantage of new technologies have appeared before, and the current technological progress allows us to conceive that today’s initiatives have a greater chance of success. However, it is worth referring to earlier experiences in order to adapt the present intervention in the best possible way to both the needs and the capacity of local communities and their institutional environment. Especially since work on the new framework of European funds for 2021–2027 is about to reach the crucial phase when decisions will be taken on how much funding will go to smart villages.

This article was written just before the coronavirus pandemic. During the pandemic, the authors have added this paragraph, also at the suggestion of reviewers. The whole world of science is observing this new situation and trying to draw conclusions from the current facts. We have started thinking differently about the future. We have undoubtedly entered a world of permanent changes. Will the “corona crisis” deepen the processes of depopulation of peripheral zones and at the same time increase the concentration of population in suburban areas? Will we take advantage of the possibilities offered by virtual communication, remote working, on-line consumption and telemedicine, and will there be a renaissance of villages remote from urban civilisation? What is happening is a “process” and as we observe it we will acquire arguments to determine possible scenarios. Today, however, we can already see that the emergence of this crisis has shown both certain weaknesses and benefits in the implementation of this concept. The undoubted benefits include, among others, the rapid acquisition of competences by people of different ages, development of on-line services, and above all—in the hinterland—“taming the internet”.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Ł.K. and M.S.; methodology, Ł.K. and M.S.; formal analysis, Ł.K. and M.S.; investigation, Ł.K. and M.S.; resources, Ł.K. and M.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Ł.K. and M.S.; writing—review and editing, Ł.K. and M.S.; visualisation, Ł.K.; supervision, M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The study uses data from the Rural Development Monitoring (MROW) project carried out jointly by the European Fund for the Development of Polish Villages (EFRWP) and the Institute of Rural and Agricultural Development, Polish Academy of Sciences (IRWiR PAN). The data concern internet accessibility in rural areas (source: Office of Electronic Communications–UKE and the Commune Survey) and the level of socioeconomic development of rural and urban-rural communes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bryden, J.M.; Dawe, S.P. Development Strategies for Remote Rural Regions: What Do We Know So Far? 1998. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/17486574/Development_strategies_for_remote_rural_regions_what_do_we_know_so_far (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- Chapman, R.; Slaymaker, T. ICTs and Rural Development: Review of the Literature, Current Interventions and Opportunities for Action; ODI: London, UK, 2002; Working Paper 192. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez, R. Appreciating the contribution of broadband ICT with rural and remote communities: Stepping stones toward an alternative paradigm. Inform. Soc. 2007, 23, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.K.; Thorat, S.B.; Kalyankar, N.V. Reaching the unreached. A role of ICT in sustainable rural development. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Secur. 2010, 7, 220–224. [Google Scholar]

- Salemink, K.; Strijker, D.; Bosworth, G. Rural development in the digital age: A systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. J. Rur Stud. 2017, 54, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, J. Information Technology and Development: A New Paradigm for Delivering the Internet to Rural Areas in Developing Countries; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Warren, M. The digital vicious cycle: Links between social disadvantage and digital exclusion in rural areas. Telecommun. Policy 2007, 31, 374–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janc, K.; Czapiewski, K.Ł. The internet as a development factor of rural areas and agriculture—Theory vs. Practice. Studia Reg. 2013, 36, 89–105. [Google Scholar]

- Naldi, L.; Nilsson, P.; Westlund, H.; Wixe, S. What is smart rural development? J. Rural Stud. 2015, 40, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ENRD. Smart Villages: Revitalising Rural Services. EU Rural Rev. 2018, 26. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/enrd_publications/publi-enrd-rr-26-2018-en.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- ENRD. Smart Villages: Revitalising Rural Services. 2018. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ckB71hb0kx0 (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- ENRD. How to Support Smart Villages Strategies Which Effectively Empower Rural Communities? Orientations for Policy-Makers and Implementers. 2019. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/enrd_publications/smart-villages_orientations_sv-strategies.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- EC. EU Action for Smart Villages. 2017. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/eu-action-smart-villages_en (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- van Gevelt, T.; Holmes, J. A Vision for Smart Villages. 2015. Available online: https://e4sv.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/05-Brief.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Cork 2.0 Declaration. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/sites/agriculture/files/events/2016/rural-development/cork-declaration-2-0_en.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Rural People’s Declaration of Candás Asturias. 2019. Available online: https://www.arc2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/declaration.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- OECD. Principles on Urban Policy and on Rural Policy. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/regional/ministerial/documents/urban-rural-Principles.pdf (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Davies, N. Volume II: 1795 to the Present. In God’s Playground. A History of Poland; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner, A.; Stanny, M. Socio-Economic Development of Rural Areas in Poland; EFRWP, IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Stanny, M.; Rosner, A.; Komorowski, Ł. Monitoring Rozwoju Obszarów Wiejskich. Etap III. Struktury Społeczno-Gospodarcze, Ich Przestrzenne Zróżnicowanie i Dynamika (Rural Development Monitoring. Stage III. Socioeconomic Structures, Their Spatial Diversity and Dynamics); EFRWP, IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. Rural Areas in Poland—National Agricultural Census 2010. 2013. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/agriculture-forestry/national-agricultural-census-2010/rural-areas-in-poland-national-agricultural-census-2010,1,1.html (accessed on 3 March 2020).

- Stanny, M.; Rosner, A.; Komorowski, Ł. The Relationship between the Level of development and the socio economic structure of Rural Areas. Poland: At the junction of Eastern and Western Europe. IRWiR PAN. under review.

- ESPON. Shrinking rural regions in Europe. Towards Smart and Innovative Approaches to Regional Development Challenges in Depopulating Rural Regions. 2017. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/ESPON%20Policy%20Brief%20on%20Shrinking%20Rural%20Regions.pdf (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Stasiak, A. Problems of Depopulation of Rural Areas in Poland after 1950. In The Processes of Depopulation of Rural Areas in Central and Eastern Europe; Stasiak, A., Mirowski, W., Eds.; IGiPZ PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 1990; Conference Papers 8; pp. 13–37. [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, I.; Rosner, A.; Stanny, M. Kształtowanie się populacji ludności wiejskiej (Rural population development). In Ciągłość i zmiana. Sto lat Rozwoju Polskiej Wsi (Continuity and Change: A Hundred Years of the Development of Polish Rural Areas); Halamska, M., Stanny, M., Wilkin, J., Eds.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 77–117. [Google Scholar]

- Flaga, M.; Wesołowska, M. Demographic and social degradation in the Lubelskie Voivodeship as a peripheral area of East Poland. Bull. Geogr. Socio-Econ. Ser. 2018, 41, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halamska, M. Wspierać czy zalesiać? Dylematy rozwoju wiejskich obszarów problemowych (Supporting or Afforesting? Dilemmas in the Development of Rural Problem Areas in Poland). Wieś I Rol. 2018, 180, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the world. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OF. Błędne Koło Niedorozwoju (The Vicious Circle of Underdevelopment). 2019. Available online: https://www.obserwatorfinansowy.pl/tematyka/makroekonomia/bledne-kolo-niedorozwoju (accessed on 4 March 2020).

- Czarnecki, A. Urbanizacja Kraju I Jej Etapy (Urbanization of the Country and Its Stages). In Ciągłość i zmiana. Sto Lat Rozwoju Polskiej Wsi (Continuity and Change: A Hundred Years of the Development of Polish Rural Areas); Halamska, M., Stanny, M., Wilkin, J., Eds.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; Volume 1, pp. 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Glossary: Functional Urban Area. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Functional_urban_area (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- Rosner, A. Zmiany Rozkładu Przestrzennego Zaludnienia Obszarów Wiejskich. Wiejskie Obszary Zmniejszające Zaludnienie I Koncentrujące Ludność Wiejską (Changes in the Spatial Distribution of Rural Population. Rural Areas Reducing and Concentrating Rural Population); IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Grabowska-Lusińska, I. Migrations from Poland after 1 May 2004 with Special Focus on British Isles. Space Popul. Soc. 2008, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śleszyński, P. Delimitacja miejskich obszarów funkcjonalnych stolic województw (Delimitation of the Functional Urban. Areas around Poland’s voivodship capital cities). Przegląd Geograficzny 2013, 85, 173–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenstein, E.G. The Birthplaces of the People and the Laws of Migration; Trübner & Co., Ludgate Hill, E.C.: London, UK, 1876. [Google Scholar]

- Stanny, M. Dynamika zmian demograficznych ludności wiejskiej i jej zasobów pracy (Demography of Rural Areas in Poland). Polityka Społeczna 2012, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rosner, A. Współczesne procesy zmian zaludnienia obszarów wiejskich w Polsce (Contemporary Processes of Population Changes of Rural Areas in Poland). In Obszary Wiejskie. Wiejska Przestrzeń I Ludność, Aktywność Społeczna I Przedsiębiorczość (Rural Areas—Countryside Expanse and Population, Social Activity and Enterpreneurship); Heffner, K., Klemens, B., Eds.; KPZK PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; Volume 167, pp. 232–249. [Google Scholar]

- Paniagua, A. Smart Villages in Depopulated Areas. In Smart Village Technology. Concepts and Developments; Patnaik, S., Sen, S., Mahmoud, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 17, pp. 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, R.; Hunt, P. Telecentre Evaluation: A Global Perspective. Report of an International Meeting on Telecentre Evaluation; Gómez, R., Hunt, P., Eds.; IDRC: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Kaleta, A. Telechata jako instrument zrównoważonego rozwoju obszarów wiejskich (Telecottage as a tool of the rural areas sustainable development). Annales Universitatis Mariae Curiae-Skłodowska Sectio I Philosophia-Sociologia 2011, 36, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, R. Communications Technology. In Think Tank on Research into Rural Education, Proceedings of the Conference Held by the RERDC, Townsville, Australia, 10–14 June 1990; McShane, W., Ed.; James Cook University: Townsville, Australia, 1990; pp. 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Komorowski, Ł.; Stanny, M. (R)ewolucja wyposażenia wsi w wodę, prąd i telefon ((R)evolution in bringing water, electricity and telephones to rural areas). In Ciągłość i Zmiana. Sto Lat Rozwoju Polskiej Wsi (Continuity and Change. Hundred Years of the Development of Polish Rural Areas); Halamska, M., Stanny, M., Wilkin, J., Eds.; IRWiR PAN: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 761–801. [Google Scholar]

- GUS. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland. 2017. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbook-of-the-republic-of-poland-2017,2,17.html (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- GUS. Statistical Yearbook of the Republic of Poland. 2019. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/en/topics/statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbooks/statistical-yearbook-of-the-republic-of-poland-2019,2,21.html (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- POPC. Lista Projektów (List of Projects). Available online: https://www.polskacyfrowa.gov.pl/strony/o-programie/projekty/lista-beneficjentow/ (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- MFiPR. Wpływ Polityki Spójności na Rozwój Obszarów Wiejskich (The Impact of Cohesion Policy on Rural Development). 2019. Available online: https://www.ewaluacja.gov.pl/strony/badania-i-analizy/wyniki-badan-ewaluacyjnych/badania-ewaluacyjne/wplyw-polityki-spojnosci-na-rozwoj-obszarow-wiejskich/ (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- KSOW. Rekomendacje KSOW Wobec Smart Villages (KSOW Recommendations for Smart Villages). 2019. Available online: http://ksow.pl/news/entry/15022-rekomendacje-ksow-wobec-smart-villages.html (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- Komorowski, Ł. Laboratorium Smart Villages: Wizyta w Fińskich Smart Wsiach (Smart Village Laboratory: A Visit to Finnish Smart Villages). 2019. Available online: http://ksow.pl/news/entry/15075-laboratorium-smart-villages-wizyta-w-finskich.html (accessed on 16 February 2020).

- Guzal-Dec, D. Inteligentny Rozwój Wsi—Koncepcja Smart Villages: Założenia, Możliwości I Ograniczenia Implementacyjne (Intelligent Development of the Countryside—the Concept of Smart Villages: Assumptions, Possibilities and Implementation Limitations). Econ. Reg. Stud. 2018, 3, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-delHoyo, R.; Mora, H. Toward a New Sustainable Development Model for Smart Villages. In Smart Villages in the EU and Beyond; Visvizi, A., Lytras, M.D., Mudri, G., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, B. Delivering on the concept of smart villages—in search of an enabling theory. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 634–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolski, O.; Wójcik, M. Smart Villages Revisited: Conceptual Background and New Challenges at the Local Level. In Smart Villages in the EU and Beyond; Visvizi, A., Lytras, M.D., Mudri, G., Eds.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A. IOT, Smart Technologies, Smart Policing: The Impact for Rural Communities. In Smart Village Technology. Concepts and Developments; Patnaik, S., Sen, S., Mahmoud, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 17, pp. 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwolińska-Ligaj, M.; Guzal-Dec, D.; Adamowicz, M. Koncepcja inteligentnego rozwoju lokalnych jednostek terytorialnych na obszarach wiejskich regionu peryferyjnego na przykładzie województwa lubelskiego (The Concept of Smart Development of Local Territorial Units in Peripheral Rural Areas: The Case of Lublin Voivodeship). Wieś I Rol. 2018, 179, 247–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishar, A.; Šťastná, M. Smart village and sustainability. Southern Moravia case study. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 651–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonenberg, W.; Qi, L.; Zhou, M.; Wei, X. Smart Village as a Model of Sustainable Development. Case Study of Wielkopolska Region in Poland. In Advances in Human Factors in Architecture, Sustainable Urban Planning and Infrastructure; Charytonowicz, J., Falcão, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidyba, M.; Makowski, Ł. Smart City. Innowacyjne Rozwiązania w Administracji Publicznej a Zarządzanie Inteligentnym Miastem (Smart City: Innovative Solutions in Public Administration vs. Smart city Management); Wydawnictwo WSB: Poznań, Poland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fajrillah, F.; Mohamad, Z.; Novarika, W. Smart city vs smart village. J. Mantik Penusa 2018, 22, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Visvizi, A.; Lytras, M.D. Rescaling and refocusing smart cities research: From mega cities to smart villages. J. Sci. Tech. Pol. Manag. 2018, 9, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavratnik, V.; Kos, A.; Duh, E.S. Smart villages: Comprehensive review of initiatives and practices. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malek, J.A.; Adawiyah, R. Smart city (SC)—smart village (SV) and the ‘Rurban’ concept from a malaysia-indonesia perspective. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2019, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.; Cha, J. A Trend on smart village and implementation of smart village platform. Inter. J. Adv. Smart Converg. 2019, 8, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visvizi, A.; Lytras, M.D. It’s not a fad: Smart cities and smart villages research in European and global contexts. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, L.; Williams, F. Healthy ageing in smart villages? Observations from the field. Eur. Countrys. 2019, 11, 616–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Rural 3.0. A Framework for Rural Development. 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regional-policy/Rural-3.0-Policy-Note.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- MFiPR. Krajowa Strategia Rozwoju Regionalnego 2030. Rozwój Społecznie Wrażliwy I Terytorialnie Zrównoważony (National Regional Development Strategy 2030: Socially Sensitive and Territorially Sustainable Development). 2019. Available online: https://www.gov.pl/web/fundusze-regiony/krajowa-strategia-rozwoju-regionalnego (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Bled Declaration. 2018. Available online: http://pametne-vasi.info/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Bled-declaration-for-a-Smarter-Future-of-the-Rural-Areas-in-EU.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- ENRD Thematic Group “Smart Villages”. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/enrd-thematic-work/smart-and-competitive-rural-areas/smart-villages_en (accessed on 1 February 2020).

- Jedlińska, R.; Rogowska, B. Rozwój e-administracji w polsce (The development of e-administration in Poland). Ekon. Probl. Usług 2016, 123, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Śledziewska, K.; Zięba, D. E-Administracja w Polsce na tle Unii Europejskiej. Jak z Niej (nie) Korzystamy (E-Administration in Poland Compared to the European Union: How We Are (Not) Using It); Digital Economy Lab UW: Warsaw, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maaseutu. Smart Villages in Finland, Plans for the Future. 2019. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/tg9_smart-villages_future-interventions_selkainaho.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- MARD. The Existing Rural Development Measures and Idea for Future Framework for Supporting Smart Villages in Poland. 2020. Available online: https://enrd.ec.europa.eu/sites/enrd/files/5_tg11_smart-villages_sv-interventions_gierulska_0.pdf (accessed on 3 May 2020).

- Haider, M.F.; Siddique, A.R.; Alam, S. An approach to implement frees space optical (FSO) technology for smart village energy autonomous systems. Far East. J. Electron. Commun. 2018, 18, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GUS. Społeczeństwo Informacyjne w Polsce w 2019 r. (The Information Society in Poland in 2019). 2019. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/nauka-i-technika-spoleczenstwo-informacyjne/spoleczenstwo-informacyjne/spoleczenstwo-informacyjne-w-polsce-w-2019-roku,2,9.html (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Batorski, D. Technologies and Media in Households and Lives of Poles. In Social Diagnosis 2015, The Objective and Subjective Quality of Life In Poland; Czapiński, J., Panek, T., Eds.; Contemporary Economics: Warsaw, Poland, 2015; Volume 9/4, pp. 367–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalega, T. Korzystanie z Internetu i Wirtualizacja Konsumpcji Wśród Polskich Seniorów: Wyniki Badań Bezpośrednich (The use of the Internet and the Virtualisation of Consumption among Polish Seniors: The Results of Primary Research). In Organizacja Społeczna w Strukturach Sieci: Doświadczenia i Perspektywy Rozwoju w Europie Środkowej i Wschodniej (Social Organisation in Network Structures: Experiences and Development Prospects in Central and Eastern Europe); Betlej, A., Partycki, S., Parzyszek, M.J., Eds.; Wydawnictwo KUL: Lublin, Poland, 2016; pp. 138–153. [Google Scholar]

- Kolkowska, E.; Soja, E.; Soja, P. Implementation of ICT for Active and Healthy Ageing: Comparing Value-Based Objectives Between Polish and Swedish Seniors. In Information Systems: Research, Development, Applications, Education; Wrycza, S., Maślankowski, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 333, pp. 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyn, M. Digitalization and Its Impact on Life in Rural Areas: Exploring the Two Sides of the Atlantic: USA and Germany. In Smart Village Technology. Concepts and Developments; Patnaik, S., Sen, S., Mahmoud, M.S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 17, pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ursula von der Leyen A Union that Strives for More. My Agenda for Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/political-guidelines-next-commission_en.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2020).

| 1 | Socioeconomic development is understood as “the process of transforming rural areas into an inhabitant-friendly environment, i.e., one which allows them to fulfil their needs and aspirations, particularly with regard to labour conditions and obtaining satisfactory income; access to public services and broadly defined cultural goods; a sense of participation in the life of the local community; a sense of agency in the ongoing transformation; etc.” [19] (p. 13). According to the MROW study, “to obtain one evaluation that would characterise an object from many standard features, all standardised variables for each object should be summed. The evaluation of a variable that characterises an i-th object is called a ‘synthetic variable’. A synthetic variable obtained from following Formula (2) assumes values within the range 0–1: where a′ij is the normalised value of the j-th feature in the i-th object (after the destimulant is changed to stimulant), n is number of objects, and mi is the weight factor of an i feature” [22]. |

| 2 | The organiser was the Institute of Rural and Agricultural Development of the Polish Academy of Sciences, call for applications 3/2019 of the Polish Rural Network (KSOW). The project involved a competition for descriptions of smart-village initiatives, which contributed to disseminating and promoting the concept among rural residents, identifying a wide range of social and digital innovations emerging in rural areas, and presenting them in a knowledge bank. |

| 3 | “A functional urban area consists of a city and its commuting zone. Functional urban areas therefore consist of a densely inhabited city and a less densely populated commuting zone whose labour market is highly integrated with the city” [31]. |

| 4 | The internet accessibility rate is measured as the ratio of the number of network terminations enabling internet services to be provided in a given area to the number of housing units in that area. |

| 5 | The questionnaire form was filled in by the commune office. The response rate was 95% (N = 2064). |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).