Community Development through the Empowerment of Indigenous Women in Cuetzalan Del Progreso, Mexico

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Indigenous Autonomy as an Asset for Social Resistance and Advancements of Land Rights

2.1. Problem Statement: The Struggle of Indigenous Groups to Secure Land Rights

2.2. Contextualization: The Bond of Women With Land and Water According to Nahua Cosmogony

3. Methods and Case Study

3.1. Data Collection Methods

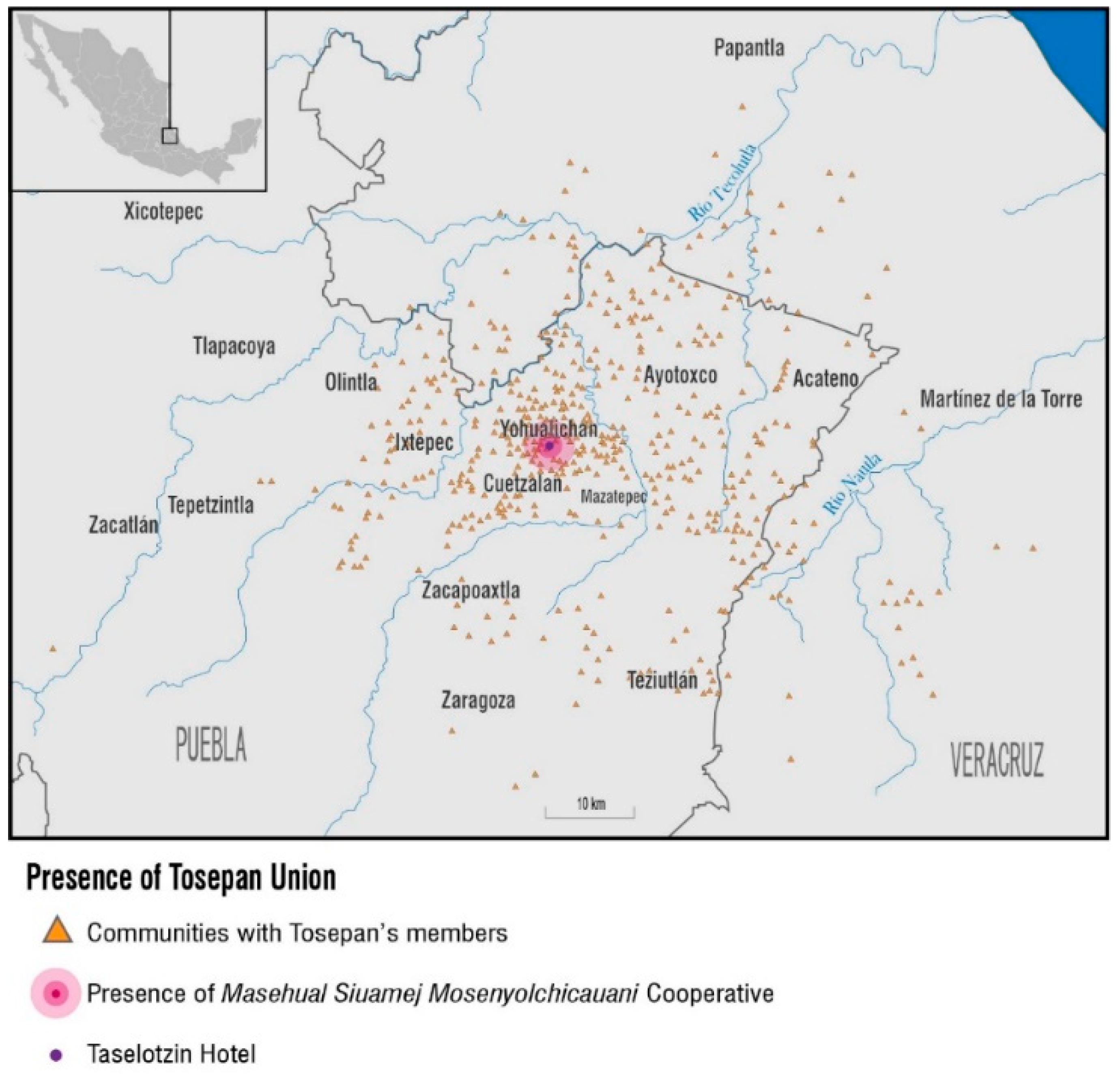

3.2. Case study: Masehual Siuamej Mosenyolchicauani, the Nahua Women that Work Together in Cuetzalan “Pueblo Mágico”

4. Literature Review: Institutional Framework for the Village Renewal and Indigenous Organization

4.1. Village Renewal through the “Pueblos Mágicos” Federal Program

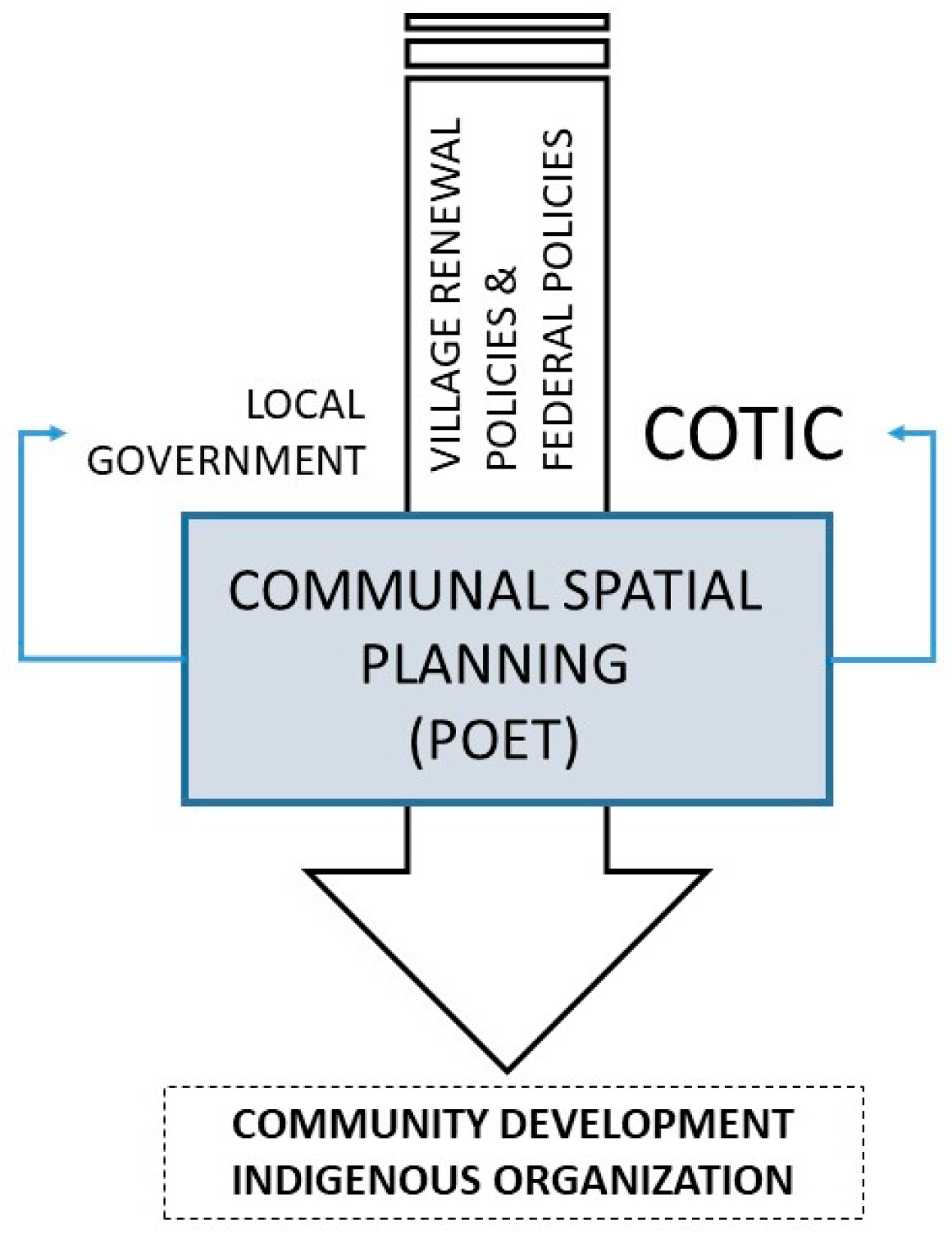

4.2. POET: Land and Environmental Management Program for Cuetzalan

5. Results and Discussion: Contextualization of Indigenous Rural Women’s Rights and Roles

5.1. First Statement—Women Are Segregated in Rural Areas

- “Life used to be harder, with fewer opportunities, I worked in the fields” (Y.S.H., 48 years old).

- “I used to work in the fields, I planted corn and beans, and could go to school. I learned to embroider at 11 years old by watching my mother doing it” (J.M.N.C., 51 years old).

- “I was one of the few who got permission from my parents to continue studying until my teenage years” (C.A.L., 41 years old).

- “Before Masehual, there were no opportunities for women, nor capacity building. We could not go out alone, although the community always supported us” (Y.C.S., 68 years old) [51].

5.2. Second Statement—The Feminization of Rurality through Social Organizations Empowers Women

5.3. Third Statement—The Empowerment of Indigenous Women Is a Catalyst for Development

5.4. Fourth Statement—Village Renewal Policies Should be Facilitators of Community Development

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- What is the status quo of Indigenous rural women? Indigenous women face particular challenges in exerting their rights. This means that more than 10 million women live in conditions of poverty attributable to the socio-political and cultural context in which they are embedded and due to the patriarchal dependence networks, that they are forced to rely on for survival. A lack of access to land prevents them from producing food for self-consumption and trade, building a house, and achieving autonomy. It also obstructs their participation in decision making processes at the ejidal assemblies. This statement does not imply, however, that their contribution to farming is insignificant. On the contrary, women represent 34% of the workforce and are responsible for half of the country’s foodstuff production.

- Which mechanisms are used to empower Indigenous women in the rurality? There are legal instruments to empower Indigenous women in the rurality, such as the Mexican Constitution, the General Social Development Act, and the Sustainable Rural Development Act. They state that men and women have equal rights, recognize Indigenous autonomy, and seek social and gender equity throughout the development of rural actions and programs. Nonetheless, Nahua customary practices are weakly implemented, and thus, women’s rights are under-rated. In Cuetzalan, under a patriarchal structure that neglects women’s needs, worth, voice, and right to vote, Indigenous women have recovered their Nahua identity and cosmogony by uniting in the form of female associations. These mechanisms of self-empowerment, such as the Masehual organization, address the immediate needs of their members via capacity building, biocultural management, and tenure security with a sustainable rural development approach that has direct positive effects in the community. This vision ensures the sustainability of the project in the long run. As a result, the members participate more actively in decision making through COTIC. Cuetzalan is an exemplary case in which social resistance, respect for traditions, changes in roles, and the determination to succeed can result in inclusive programs, instruments, and mechanisms.

- What are the socioeconomic impacts of empowered Indigenous women in Cuetzalan? In the case of Masehual, the empowerment of Indigenous women in the rurality has contributed to community development in terms of promoting female participation in the ejidal, communal, and land management assemblies, engagement in the COTIC, sustainable development, human rights, women’s rights, economic opportunities, education, inclusiveness, equality, and identity. Training the local women to improve their agricultural, artisanal, and management skills is perceived among the participants as having direct positive effects on the household economy and social cohesion. Masehual stands as an exemplary case in which, despite social and legal marginalization, the empowerment of Indigenous female farmers has led to social, economic, environmental, and cultural growth for the community.

- What is the role of village renewal policies in community development? The “Pueblos Mágicos” program tried to homogenize Indigenous culture through urban image and economic incentives. The vertical approach of the Federal policy is not complementary to Cuetzalan’s bioculture. Therefore, land management instruments like POET and groups like COTIC act as transversal monitors of the program. Therefore, the “Pueblos Mágicos” program fell by the wayside as it was limited to promoting touristic spots without facilitating community development. Cultural tourism could act as a catalyst for multi-dimensional development rather than bringing only economic growth if it is respectful towards the environment, cultural heritage, and local common good. Federal programs that foster cultural tourism projects, such as “Pueblos Mágicos” and POET, have had both positive and negative effects on the regional land management approach and economy. Although the programs were not formulated specifically to empower women, Indigenous female associations have taken part. As a prime example, the Taselotzin hotel successfully manages to integrate Indigenous traditional knowledge and global tourism demands through fair trade; moreover, its success proves that tenure security can lead to social cohesion and that sustainable projects can be profitable.

- (1)

- Study tenure security and landuse changes making use, among others, of the guidelines for Tenure Responsive Land Use Planning [64] and remote sensing;

- (2)

- Conduct household surveys as a data collection method to determine and compare the household economy based on agriculture and cultural tourism managed by men and women;

- (3)

- Carry out an assessment of the quality and quantity of the crops and hostelry services managed by men and women.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- INPI. Indicadores Socioeconómicos de los Pueblos Indígenas de México 2015; Gobierno de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2017.

- Solís, P.; Güémez, B.; Lorenzo, V. Por mi Raza Hablará la Desigualdad. Efectos de las Características Étnico-Raciales en la Desigualdad de Oportunidades en México; Oxfam: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- CONEVAL. Medición de Pobreza 2008–2018; Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Consejo Nacional de Población. Infografía de la población indígena 2015. 2016. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/121653/Infografia_INDI_FINAL_08082016.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres. Las Mujeres Rurales Producen Más del 50% de la Producción de Alimentos en México; INMUJERES: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tlali, T. El ordenamiento territorial ecológico de Cuetzalan, una herramienta para la defensa del territorio ante megaproyectos. La Jornada de Oriente. 17 June 2014. Available online: https://www.lajornadadeoriente.com.mx/puebla/el-ordenamiento-territorial-ecologico-de-cuetzalan-una-herramienta-para-la-defensa-del-territorio-ante-megaproyectos-el-caso-del-proyecto-de-pemex (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Benton Zavala, A.M. Paisaje Lingüístico en Tosepan Kalnemachtiloyan: ‘Lecturas’ sobre educación intercultural y revitalización. In Proceedings of the Conference “XIV Congreso Nacional de Investigación Educativa”, San Luis Potosí, Mexico, 20–24 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bernkopfová, M. La Identidad Cultural de los Nahuas de la Sierra Nororiental de Puebla y la Influencia de la Unión de Cooperativas Tosepan; Karolinum Press: Prague, Czech Republic, 2014; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- López Bárcenas, F. La Autonomía de los Pueblos Indígenas de México; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, La Revista la Universidad de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2019; pp. 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Bonfil Batalla, G. El concepto de indio en América: Una categoría de la situación colonial. Boletín Bibliográfico Antropol. Am. 1977, 39, 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, M.; Durán-Díaz, P.; Kurjenoja, A.K.; Gutiérrez-Juárez, E.; González-Rivas, D.A. Evolution and collapse of ejidos in Mexico-To what extent is communal land used for urban development? Land 2019, 8, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aparicio Wilhelmi, M. La libre determinación y la autonomía de los pueblos indígenas: El caso de México. Boletín Mex. De Derecho Comp. 2009, 42, 13–38. [Google Scholar]

- Quién hay detrás del Hotel Taselotzin? Available online: http://taselotzin.mex.tl/frameset.php?url=/actividades.html (accessed on 25 February 2020).

- Reyes García, C. El Altépetl, Orígen y Desarrollo: Construcción de la Identidad Regional Náuatl; El Colegio de Michoacán: Morelia, Mexico, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, L. The Woman Who Turned into a Jaguar, and Other Narratives of Native Women in Archives of Colonial Mexico; Stanford University Press: Redwood City, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez Galindo, Y.; Rodríguez González, H. El agua y sus significados. Una aproximación al mundo de los nahuas en México. Antípoda. Rev. De Antropol. Y Arqueol. 2019, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcos, S. Mesoamerican women’s Indigenous spirituality: Decolonizing religious beliefs. J. Fem. Stud. Relig. 2009, 25, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermoal, N.; Altamirano-Jiménez, I. Living on the Land: Indigenous Women’s Understanding of Place; Athabasca University Press: Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Rocheleau, D.; Thomas-Slayter, B.; Wangari, E. Feminist Political Ecology: Global Issues and Local Experience; Routledge: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, K.P. Indigenous women, climate change impacts, and collective action. Hypatia A J. Fem. Philos. 2014, 29, 1527–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGregor, D. Anishnaabe-kwe, Traditional Knowledge and Water Protection. Can. Woman Stud. 2008, 26, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Anaya Muñoz, A. Los Derechos de los Pueblos Indígenas, Un Debate Práctico y Ético. Renglones 2004, 56, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, K. Notokwe Opikiheet-”Old Lady Raised”: Aboriginal Women’s Reflections on Ethics and Methodologies in Health. Can. Woman Stud. 2008, 26, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Castle, E.A. Keeping one foot in the community: Intergenerational Indigenous women’s activism from the local to the global (and back again). Am. Indian Q. 2003, 27, 840–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sistema Nacional de la Información Municipal (SNIM). 2015. Available online: http://www.snim.rami.gob.mx (accessed on 9 December 2019).

- Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres. Sistema de Indicadores de Género. Gobierno de México. 2015. Available online: http://estadistica.inmujeres.gob.mx/formas/fichas.php?pag=2 (accessed on 13 December 2019).

- Jacobo Herrera, F.E.; López-Levi, L.; Valverde, C. Cuetzalan del Progreso, Puebla. Un pueblo mágico organizado por sus habitantes. In Pueblos Mágicos, Una Visión Interdisciplinaria; Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana and Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2015; pp. 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Turismo. Cuetzalan del Progreso, Puebla. SECTUR Gobierno de México. 2014. Available online: http://www.sectur.gob.mx/gobmx/pueblos-magicos/cuetzalan-del-progreso-puebla (accessed on 28 October 2019).

- Fundación Humbert para el Desarrollo Social y de la Biodiversidad A.C. Asamblea Preliminar de Información a las Comunidades del Municipio de Cuetzalan de Progreso; Municipio de Cuetzalan: Puebla, México, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- CONEVAL. Lugares para visitar: Los Pueblos Mágicos. 2012. Available online: https://www.coneval.org.mx/Informes/boletin_coneval/marzoabril2012/pueblosmagicos.html (accessed on 28 October 2019).

- Secretaría de Turismo. Pueblos Mágicos. Gobierno de México. 2014. Available online: http://www.sectur.gob.mx/gobmx/pueblos-magicos/ (accessed on 28 October 2019).

- Escalante, P.; Staples, A. El Colegio de México. Sección de obras de historia. In Historia de la Vida Cotidiana en México; El Colegio de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Gómez, M.J.; Goldsmith, M.R. Reflexiones en torno a la identidad étnica y genérica, Estudios sobre las mujeres indígenas en México. Política y Cult. 2000, 14, 61–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tovar-Hernán, D.M.; Tena Guerrero, O. Mujeres nahuas: Desapropiando la condición masculina. Culturales 2017, 5, 39–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Unión de Cooperativas Tosepan. Breve reseña histórica. Tosepan. 2016. Available online: http://www.tosepan.com/ (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Alcalá, E. Masehual Sihuamej: Mujeres Indígenas Que Resisten, Trabajan y se Apoyan Juntas. 2018. Available online: https://luchadoras.mx/masehual-sihuamej/ (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Martínez Corona, B. Género, Empoderamiento Y Sustentabilidad: Una Experiencia De Microempresa Artesanal de Mujeres Indígenas; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Centro Regional de Investigaciones Multidisciplinarias: Cuernavaca, México, 2016; pp. 109–150. [Google Scholar]

- Villa Hernández, R.E. Semistructured interview about Masehual Organization. [interv.] M. Schumacher and A. Armenta-Ramírez. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tapia Villagómez, I. Emprendimiento Femenino Rural Indígena: El Hotel Taseoltzin, Cuetzalan, Puebla; Universidad Iberoamericana Puebla: Puebla, México, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaría de Turismo. 1er Informe de Labores 2012–2013; Gobierno de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2013.

- Puga, T. Pueblos Mágicos... pero pobres. El Universal. 29 October 2018. Available online: https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/cartera/pueblos-magicos-pero-pobres (accessed on 29 October 2018).

- Secretaría de Turismo. Inversión Turística Privada Y Pública Cuetzalan; Gobierno de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014.

- Secretaría de Desarrollo Social. Pobreza y rezago. Entidad: Puebla. Municipio: Cuetzalan del Progreso. Clave 21043. Unidad de Microrregiones, Cñedulas de Información Municipal. 2010. Available online: http://www.microrregiones.gob.mx/zap/rezago.aspx?entra=zap&ent=21&mun=043 (accessed on 29 October 2019).

- Rifkin, J. The Hydrogen Economy: The Creation of the Worldwide Energy Web and the Redistribution of Power on Earth; Tarcher/Penguin: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuntamiento del Municipio de Cuetzalan del Progreso. Programa de Ordenamiento Ecológico Local del Territorio del Municipio de Cuetzalan del Progreso; Municipio de Cuetzalan: Cuetzalan, Mexico, 2010.

- Cámara de Diputados. Ley General de Equilibrio Ecológico y la Protección al Ambiente. D. Of. De La Fed. 1998, 18. [Google Scholar]

- González, A. El ordenamiento de Cuetzalan, una herramienta de defensa comunitaria. La Jornada del Campo. 17 February 2018. Available online: https://www.jornada.com.mx/2018/02/17/cam-cuetzalan.html (accessed on 2 May 2020).

- Max-Neef, M. From the Outside looking in: Experiences in Barefoot Economics; Förlaget, N., Ed.; Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation: Stockholm, Sweden, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, Artículos 1 Y 4 [Capítulo I]; H. Congreso de la Unión 25 Legislatura, Mexico: Mexico City, Mexico, 1992.

- FAO. Mujer Rural y Derecho a la Tierra. In Situación General de las Mujeres Rurales e Indígenas de México; FAO: Mexico City, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Masehual Women. Focus group discussion with five representatives from Masehual Sihuamej Mosenyolchicauani. [interv.] M. Schumacher and P. Durán-Díaz. [trans.] Pamela Durán-Díaz. Cuetzalan. 9 April 2020; Telephone interview. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Human Rights. Articles 14, 15 and 16. In Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women; United Nations Human Rights: New York, NY, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Ley General de Desarrollo Social, Article 3; H. Congerso de la Unión 25 Legistatura: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018.

- FAO. Ley del Desarrollo Rural Sustentable; FAO: Mexico City, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Registro Agrario Nacional. Datos Geográficos de las Tierras de Uso Común, Por Estado; Gobierno de México: Mexico City, Mexico, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Blanco, E. Género, etnicidad y cambio cultural: Feminización del sistema de cargos de Cuetzalan. Política y Cult. 2011, 35, 87–110. [Google Scholar]

- Villa, H.; Rufina, E. Mujeres Masehual, Deshierbando el Machismo; La Coperacha: Mexico City, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuse, P. Whose right(s) to what city? In Cities for People, not for Profit; N. Brenner, P.M., Mayer, M., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 36–53. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, M. Peri-urban Development in Cholula, Mexico. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität München, Munich, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Loeza, S.E. La participación en los procesos de desarrollo. El caso de cuatro organizaciones de la sociedad civil en el municipio de Cuetzalan, Puebla. Econ. Soc. Y Territ. 2011, XI, 95–120. [Google Scholar]

- Masehual Siuamej, M. Hilando Nuestras Historias. El Camino Recorrido Hacia Una Vida Digna/Ibero Puebla; Cecilia Ramón, F., Ed.; Instituto de los Derechos Humanos Ignacio Ellacuría: Puebla, Mexico, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Red Indígena de Turismo de México (RITA). 2013. Available online: http://www.rita.com.mx (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- United Nations Development Program. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Goal 5; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Chigbu, U.E.; Chigbu, U.E.; Haub, O.; Mabikke, S.; Antonio, D.; Espinoza, J. Tenure Responsive Land Use Planning: A Guide for Country Level Implementation; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| Overview of the Status of Women in Cuetzalan | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total population | 47,983 | 100% |

| Female population | 25,067 | 52% |

| Population that speaks a native language | 32,132 | |

| Women that speak a native language | 16,428 | 65.5% |

| Women that speak a native language and do not speak Spanish | 3721 | 22.6% |

| Total population illiteracy (*) | 6230 | |

| Illiterate women | 4238 | 16.9% |

| Economically active population | 16,623 | |

| Economically active women | 3617 | 14.4% |

| Matriarchal familiar and non-familiar households | 27% | |

| Note: (*) Population of over 15 years of age. | ||

| Public and Private Touristic Economic Investment vs. Social Welfare in Cuetzalan (*) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Public funding 2002–2012 | $57,918,208.35 | |

| Private investment 4th trimester 2011, 1st trimester 2013 and 3rd trimester 2013 | $42,580,000.00 | |

| Total amount | $100,498,208.35 | |

| Social welfare indicators | ||

| Marginalization rank (**) | 2000 | 2010 |

| High | Very High | |

| Migration (***) | 648 | 1010 |

| Population in poverty | NA | 80.8% |

| STAKEHOLDERS | LEADER(S) | ROLE |

|---|---|---|

| FEDERAL | Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources | Representatives |

| REGIONAL | Ministry of Environment | Representatives |

| LOCAL | Cuetzalan Major | Council President |

| Committee Partner | Secretary | |

| Municipal officers for tourism, education, agriculture, economy, etc. | Representatives | |

| COMMUNITY | Community members from each district | |

| Citizen members of the rural development council | ||

| Citizens from each productive sector—tourism, coffee plantations, agriculture, agro-industry, cattle, handcrafts, health, infrastructure, etc. | ||

| Citizen members of social organizations registered at the committee (18) | ||

| Independent citizens elected by the committee (6) | ||

| ACADEMY | Academics from the Autonomous University of Puebla BUAP |

| Female Fertility Rate in 2015 Indigenous Language Speakers vs. Non-Indigenous Language Speakers in Mexico | |

|---|---|

| Average number of live-born children for women who speak an Indigenous language | 3.1 |

| Average number of live-born children for women who speak a non-Indigenous language | 2.2 |

| Teenage pregnancy rate at the National level (15–19 years old) | 74 births/1000 women |

| Teenage pregnancy rate in Indigenous language speakers (15–19 years old) | 82.8 births/1000 women |

| Teenage pregnancy rate in non-Indigenous language speakers (15–19 years old) | 61.4 births/1000 women |

| ISSUES | “PUEBLOS MÁGICOS” PROGRAM | POET | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| POSITIVE ASPECTS | NEGATIVE ASPECTS | POSITIVE ASPECTS | NEGATIVE ASPECTS | |

| ECONOMY | Federal Program that grants resources to the community and infrastructure investment. | Focuses mainly on attracting tourism. | Integration of different stakeholders and community members. | Does not have economic support from the Federal Government. |

| Grants incentives for economic development. | The infrastructure investment is focused on touristic areas and not on other sectors of Cuetzalan. | Guides stakeholders in the decision-making process when new investment projects reach the community. | Does not provide direct economic incentives for the community. | |

| PATRIMONY | Operates as a caretaker of built heritage. | The protection of built heritage is only granted when there are enough Federal resources. | Local caretaker of built and intangible heritage and natural resources. | Legal and death threats against members of COTIC, especially by mining, fracking, and infrastructure projects. |

| REGULATION | Regulates urban image. | The improvements to the urban image are only granted when there are sufficient Federal resources. | All new development and infrastructure projects must be approved by COTIC. The operation rules of the program are clear and comprehensive. | Regulations established by the POET are not always well received by majors and local authorities. |

| POLICY | Invest in the national and international advertisements to attract tourism. | The commodification of local culture and vertical decisions from the Federal Government to define Indigenous culture. | It incentive the creation of COTIC. | Some individual projects oppose to POET regulations, thus achieving a unanimous stakeholders’ agreement with COTIC is challenging. |

| The local government manages economic incentives. | Corruption and suspicious use of allocated economic resources. | POET is the only legal mechanism of land management and protection of natural resources. | It has not been updated since its publication in 2010. | |

| SOCIO-SPATIAL | Delimitates an impact area of the program focused on the historical core. | The protection and delimitation of the “Pueblos Mágicos” area is not fit-for-purpose. | POET is the only permanent program that helps to improve local land management. | Insufficient instruments to integrate informal housing and urban planning over natural reserves. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Durán-Díaz, P.; Armenta-Ramírez, A.; Kurjenoja, A.K.; Schumacher, M. Community Development through the Empowerment of Indigenous Women in Cuetzalan Del Progreso, Mexico. Land 2020, 9, 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9050163

Durán-Díaz P, Armenta-Ramírez A, Kurjenoja AK, Schumacher M. Community Development through the Empowerment of Indigenous Women in Cuetzalan Del Progreso, Mexico. Land. 2020; 9(5):163. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9050163

Chicago/Turabian StyleDurán-Díaz, Pamela, Adriana Armenta-Ramírez, Anne Kristiina Kurjenoja, and Melissa Schumacher. 2020. "Community Development through the Empowerment of Indigenous Women in Cuetzalan Del Progreso, Mexico" Land 9, no. 5: 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9050163

APA StyleDurán-Díaz, P., Armenta-Ramírez, A., Kurjenoja, A. K., & Schumacher, M. (2020). Community Development through the Empowerment of Indigenous Women in Cuetzalan Del Progreso, Mexico. Land, 9(5), 163. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9050163