2. Environmental Conflicts and Environmentalist Movements

Environmental topics are becoming ordinary everyday news. On one hand, the piling-up of scientific reports on the various facets of the global ecological crisis and the increasing frequency of alarming and disrupting events (e.g., the SARS-Cov2 pandemic, with chances that its origin is due to deforestation and the interaction, consumption included, with wildlife, in particular, bats [

1,

2,

3]; or the increase in landscape scale megafires in Mediterranean-type regions [

4], and how disturbances from climate tipping points are accentuating forest vulnerabilities in other regions, such as North American boreal woods and the Amazon [

5]) are drawing increasing public and media attention. On the other, environmental activism is gaining coverage thanks to the new digital era global Fridays For Future movement and its icon Greta Thunberg. However, environmental conflicts with social movements at the forefront have been present all over the planet for several decades. Large popular organizations like Greenpeace, WWF, Friends of the Earth, etc., are at the top of a pyramid completed by a large myriad of smaller organizations and movements acting and cooperating at different scales. Gerlach and Hine described it as a segmented, polycentric and integrated network (SPIN) for the case of movements of the sixties and the seventies in the USA [

6]. To better visualize and understand the reality and extent of current worldwide environmental activism, the Environmental Science and Technology Institute of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, in 2015, launched the Environmental Justice Atlas (EJATLAS), an EU-funded research project managing a collaborative database about environmental conflicts [

7]. Cases in the EJATLAS express ecological distribution conflicts (EDC) “induced by existing or anticipated environmental pollution or damage to nature affecting communities” [

7]. As of January 2020, the catalogue includes more than 3000 registers with their geographical location and a descriptive sheet in 10 EDC categories. Several thematic maps and a Special Issue of

Sustainability Science (2018) have been published from this database.

Following a similar procedure to EJATLAS, in 2018 the Geography Department of the University of Girona initiated a knowledge co-production research project in cooperation with environmentalist organizations in the region of Girona. The platform

www.paisatgessalvats.cat (Saved Landscapes) was created as a way to collect and document the track-record of environmental activism in this area since the 1970s [

8]. To date, 160 conflicts have been registered with the aim of analyzing triggers (plans, projects, or specific activities), environmentalist movements, their territorial impact and outcomes, and discuss political opportunities and governance derivatives.

The first conclusions confirm an extensive network of more than 150 organizations and movements in the last 50 years, with around half of them currently active. Movements driven by place attachment or topophilia, by which positive emotions linked to places and landscapes derive notions like the sense of place, sense of belonging, or territorial identity [

9,

10,

11,

12]. For people in these movements, landscape is an essential aspect of their quality of life and worth fighting for in an organized way. In effect, the European Landscape Convention (2000) recognizes the profound relationship between people and their surrounding landscapes, and the right to participate in the definition and implementation of the landscape policies [

13].

Alongside, a powerful connection between this landscape-based activism and more holistic socioecological sustainability has been established. Longitudinal studies of environmental conflicts have shown that the success of the mobilization led to moving projects with high environmental impact on communities with a lower resistance capacity, intensifying pre-existing precarity in services and socioeconomic conditions with environmental pollution; the so-called Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY) movements and their unexpected impacts elsewhere [

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, the authors sustain that not all conflicts ignite after this “selfish” principle, nor does a movement activate upon such vision only. As different scholars have reflected, mobilizations are in a progressive way the consequence and reaction to inter-scalar interactions, between the global logics of capital and the local needs and interests, very often absolutely opposite [

18,

19,

20,

21]. In Girona, the success of the mobilizations as a result of these land use tensions exceeds 50% of the cases, with a remarkable contention of ecological footprint on the region (yet not thoroughly quantified), especially in areas under more pressure. There is also a significant conversion rate of conflicts to territorial or heritage protection figures, contributing in regards to nature to the region’s green infrastructure network with Natural Parks, restricted conservation areas, ecological corridors, etc. In addition, several regional, sectoral and urban land planning instruments evolved from the conflicts, increasing sustainability and balance in a territory dominated by powerful transformative forces due to the strategic location of the region.

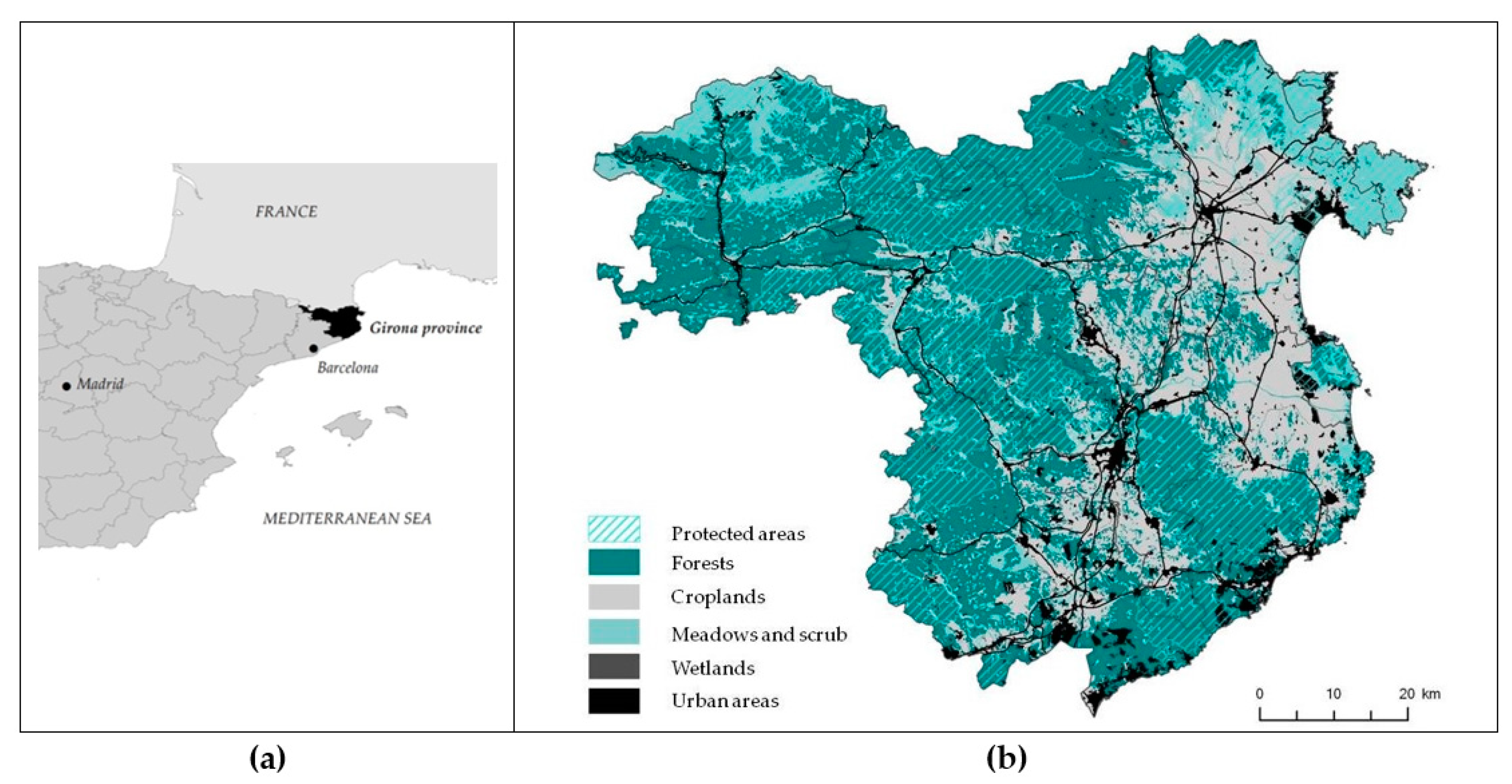

3. Girona: A Territory with a Landscape Narrative

The region of Girona is located on the northeast of the Iberian Peninsula as presented in

Figure 1, forming one of the four Catalan provinces in Spain’s administrative division

(a), or the Counties of Girona

(b), one of the eight decentralization territories according to Catalonia’s autonomous organization, with slight differences in between them, in surface, number of municipalities and counties included. For this research, the latter reference will be used, spanning 5584 Km

2 for a population of 756,193 (2019) in 208 municipalities.

Landscape diversity and strategic location are the main geographic characteristics in this territory. In a two-hour drive, ecological gradients and geological contrasts span from close to 3,000 m above sea level in the Pyrenees to 200 Km of shoreline include volcanic and karstic systems, fluvial flatlands, dunes and wetlands, alongside with traditional cultural landscapes, such as cork production forests, stonewall architecture, olive groves and vineyards [

23]. All of this for a region with a very strategic role in the Iberian Peninsula, thanks to the combination of cross-border location, exposure to the Mediterranean and the vicinity to Barcelona. Hosting the main terrestrial corridor to-from Africa and the rest of the European continent, alongside with historic maritime routes, have made of Girona settlement and crossroads for multiple cultures and relevant historic events. As a result, the region embraces a very high density of natural and cultural heritage, with more than one third of its territory in the EU’s Nature 2000 network and 516 Cultural Good of National Interest elements [

23].

From an economic point of view, Girona and its counties have also received the qualification of “balanced”. This refers to a notable economic diversification, within and between sectors (primary sector, services, industry and construction), and one of the highest per capita incomes in the country [

24]. This vision obviously hides different dynamics and realities across the region, and historic balance was broken after the substantial and accelerated transformations since the 1960s. Economic activity and population rapidly concentrated on the coast and along the central infrastructures corridor, leading to very specialized areas like the Costa Brava for tourism and construction; others in clear and persistent rural/industrial decay; and some in deep transformation processes, such as the metropolitan area of Girona, which hosts a growing hub of infrastructures and services—airport, high-speed and freight railway stations, University, Autonomic and Central government Administration buildings, etc.—that is boosting the city’s role as regional capital [

24]. This process of change took place in a series of cycles of high economic and construction intensity (1960–1974; 1986–1991; 1998–2007), followed by stagnation periods (1975–1985; 1992–1997; 2008–2018) [

22,

25].

Regional landscape features of Girona have been, at least in the Catalan context, at the source of artistic inspiration for poets, novelists and painters since the second half of 19th century. As it was happening elsewhere in Europe, art works were constructing the landscape; i.e., through them portions of land were “framed”, creating a socialized imaginary loaded with meanings [

26]. Indeed, the territory of Girona contained and condensed through its mountains, valleys and coasts, beauty and identity ideas in much larger measure than other areas of the country [

27]. Therefore, to the region’s objective natural and cultural values—i.e., biodiversity, landmarks, monuments—must be added to others that, during the first decades of the 20th century, will conform to the narrative of some of the principal links between landscape and Catalan identity [

27].

This symbolic “burden” of the landscape got socialized, and already in the first half of the 20th century voices emerged demanding the recognition, projection, and more incipiently, the protection of some of these spaces. The historical center of Girona at the beginning of the 1900s [

28], the Greek and Roman ruins of Empúries in the decade of 1910, or the Costa Brava in 1935 [

29], were among those that society claimed, and in some cases managed, through planning or political action, to obtain recognition of their values and the risks of abandonment or destruction.

Lehtinen et al. define “places at the nature-culture continuum that are practically, or in identity-terms, or spiritually, etc. important for the community/civil society” as

thick or

dense places [

30]. For the authors, Girona is an example of this

thickness extended to the whole region, through a historic landscape narrative that has become an inherent element of the local identity and even for the national identity. Environmentalist movements have become the contemporary civic expression of this shared cultural feature.

4. Materials and Methods

This research develops the analysis of territory advocacy mobilization processes in the region of Girona from 1970 onwards, through quantitative–qualitative treatment and cartography of two types of data: environmental conflict cases, and grassroots environmentalist movements.

Both databases are the result of collaborative work with environmental activism groups, their legal services, and documental research (the literature, the organizations’ archives, online search). At the beginning of 2018, the authors produced a preliminary list of approximately 60 cases based on their own knowledge—including direct involvement. From thereon, an iterative communication process with activists took place, in order to increase and refine data and results, including that of the environmental movements dataset. Communication followed an organic and informal process, through emails, phone calls, instant messaging, and eventually meetings (in group or individualized), based on pre-existing relationship and trust between the researchers and the activists. The two most relevant organizations in Girona—IAEDEN-Salvem Empordà and Associació Naturalistes de Girona—own an extensive documental archive, which helped clarify certain doubts regarding the cases. Equally relevant was the cooperation from Diagonal Advocats, a law firm that has been involved in many of the cases, with a solid documental background, who are very specialized in environmental law and court litigations. Additional research was conducted through website searches, with four outstanding sources of information: (a) the city of Girona’s Document Management, Archives and Publications Service, which gathers digitalized news from press dating back to 1793 (

https://www.girona.cat/sgdap/cat/premsa.php) [

31]; (b) the Territorial Yearbook of Catalonia, published by the Catalan Society for Land Management, which developed between 2003 and 2015 a systematic observation of territorial transformations and review of the derived debates and conflicts (

http://territori.scot.cat/cat/anuari.php) [

32]; (c) the Urban Map of Catalonia, an information transparency tool of the Territory and Sustainability Department of Catalonia, that provides an online map server for site-specific analysis of spatial and urban planning of the 947 municipalities of Catalonia, allowing to overlay certain sectorial and environmental layers, and consult related planning documents at different scales (

http://dtes.gencat.cat/muc-visor/AppJava/home.do) [

33]; and (d) the Justice Department of Catalonia, which has a search and download engine about legally registered civil society organizations, with data about the type of entity, its mission or focus, registration date, and address, among other details (

http://justicia.gencat.cat/ca/serveis/guia_d_entitats/index.html) [

34]. Last but not least, the collaborating environmental activists were also a sound source of information through their expert judgment and networking capacity.

In what refers to the conflicts, the database registered a set of descriptive fields, such as: denomination; conflict trigger; location (point-based coordinates and pertinence at municipal and county scale, either singular or multiple); current status of the conflict as described in

Table 1; land use protection figures present in the conflict area or declared as a result; and leading movement(s). In addition, the Kernel Density algorithm was applied to analyze the geographical distribution of the environmental conflicts. Using QGis software, the points dataset was rasterized into 100m resolution pixels and a radius of 8500 m in order to avoid empty spots in the study area.

Regarding the movements, a separate dataset was produced, based on the foretold records of the Catalan Justice Department [

34]. The activists’ contributions allowed extending the list of collectives, include informal movements, analyze their geographic action scope, and current active or inactive status. Active status refers to movements for which activity is known, or has been verified by visiting an updated webpage or through recent entries found the Google search engine. Inactive movements are, in contrast, those that, despite appearing in registers or being known by the activists, have no recent activity, or website/blog contents frozen for years. There is evidence, though, that some movements labelled as inactive, have actually entered into a lethargic status as the environmental threat that triggered their appearance was stopped, and are able to reactivate after time if the conflicting plan or project reactivates as well. Movements were, moreover, classified in typologies, with an ad-hoc categorization adapted from Vallès and Martí [

29], according to their legal nature and social role (

Table 2).

First results of the research are available on the website

www.paisatgessalvats.cat (Saved Landscapes) [

8], a knowledge coproduction platform shared by three historic environmentalist organizations—Associació Naturalistes de Girona, IAEDEN-Salvem Empordà and LIMNOS—to which the authors contributed by publishing the databases of 160 cases and their current status, using the Instamaps online open mapping software [

36]. The Saved Landscapes project received support from the Catalan Territory and Sustainability Department in 2018 and 2019, including different dissemination activities, such as a yearly seminar on environmental conflicts and activism co-organized with the Geography Department of the University of Girona.

Research is ongoing, with the construction of a larger database, in order to address very specific aspects of the cases, such as: quantitative magnitudes of the environmental impacts prevented (or not); vector cartography shaping the exact territorial extension of each case (instead of the current point-based location); detailed chronology and conflict cycles; precise legal and/or political resolutions; agents involved and their roles; action repertory; human and economic resources; dissemination materials; media impact. Furthermore, parallel works promoted by the movements themselves, such as the book Escola de Radicals (

School of Radicals; 2019) are revealing the presence of more conflicts and movements, and their extension further back in time [

37]. Apparently, this information is managed by amateur historians taking care of county records, or in the memory of the certain persons, who will be contacted and interviewed or invited to take part in “memory workshops” in the future.

5. Results

5.1. Environmental Movements: Geographical Distribution and Typology

Figure 2 presents a map with the distribution of movements at county level depicting if they are active or inactive. Confederations and platforms formed by multiple organizations and acting on an issue that affects multiple counties or at regional scale are separately represented under “Regional Impact”.

Between 1970 and 2020 the region of Girona has seen the birth, development and in some cases extinction of more than one hundred and fifty environmentalist movements. Currently, division between active and inactive movements is 64 and 90, respectively (42% and 58%). Data about the year of formation or dissolution of the movements are incomplete, hampering a full analysis of which ones are recent creations, which ones have decades of activity, and the exact period of work for those no longer active. Nevertheless, for 50 years, there has been near to a 1:1 replacement rate between extinguishing (or currently lethargic) and newborn movements, showing the permanent vitality and effervescence of environmental activism in this territory. In demographic terms, nowadays there is one active group for every 12,000 inhabitants, a ratio that could be labeled as high (in the absence of data from other territories to compare with).

Geographical distribution of movements is consistent with the region’s population, showing that environmental activism is a common denominator of Girona in general. More than 55% of the active groups and 59% of the population belong to the three coastal counties of the Costa Brava (Alt Empordà, Baix Empordà and La Selva); 17% of organizations and 15% of the population are in the three interior counties (Garrotxa, Pla de l’Estany and Ripollès); and 28% of movements, either of local or regional scope, and 26% of the population are in the capital county of Gironès.

Figure 3 complements the activity/inactivity status and geographical display of the movements with an ad-hoc categorization adapted from Vallès and Martí [

35], according to their legal nature and social role, in three typologies (as described in

Table 2): (a) informal temporary; (b) formal local; (c) structuring. With this categorization, the vast majority of movements (71%) belong to the formal local type. Hence, in general, Girona’s environmentally motivated civil society follows a track-record of formalizing this engagement through a legally constituted organization with registered members. This is relevant when facing an emerging environmental conflict, as representation of the movement through a constituted association is necessary for formally repelling a plan, project, or activity in its administrative procedure. In the long run, this kind of movement can wear out the activists, because it requires a steady commitment, a board, budget management, etc. However, it also increases the transparency and seriousness of the movements, and they become recognized brands, with identifiable leaders which the local community, the authorities, and the press can easily refer to, and they are capable of embarking on long and expensive legal processes in the courts (i.e., a decade or more for one single case). As examples of the formal local type among the active organizations, there are seven whose names start with Salvem (Let’s Save) and continue with a specific place (la platja de Pals; la costa de Begur; la muntanya de Sant Sebastià; el Golfet, el Crit; la Pineda d’en Gori; Solius; etc.). Movements born to defend one specific spot are now fixed members of the network, some of which have several cases under their domain.

Informal temporary movements are 16% of the sample. These are, usually, short-lived heterogeneous platforms created in response to an environmental threat or impact, through the federation of formal local and structuring organizations with other types of civil society (unions, neighbor associations, private sector stakeholders, local authorities, political parties, academic institutions, etc.), with the signature of a founding manifesto as common ground for the claims. This typology is more commonly used against big infrastructures (power lines, roads, landfill, etc.). nuisance activities (e.g., quarries or factories, due to noise, smell), or as a way to gain lobbying capacity thanks to the federative approach. Temporary platforms flourish and cease to exist closely following the development of the activity, plan or project they oppose. Thus, if the case is either dropped or executed, the platform will afterwards disappear as it never had the intention to become a stable movement. Even so, if the threat reactivates years after, the platform may do too, initiating a new conflict cycle for which there is already a track-record of community-acquired knowledge about the issue (in its multiple environmental and legal facets), and mobilization skills.

Finally, 20% of the movements are understood as structuring, given their capacity to structure and coordinate large campaigns, and/or their role for decades as referents at county or regional scale. There are currently 14 active movements in the Structuring category, and the other six are no longer active as their associated conflict is over. Structuring movements can be divided into two subtypes. First, those that grow around a cause and start in form of a Platform or Coordinator—like in the informal temporary case—but which evolve into a permanent structure capable of responding to several policy and/or conflict cycles. A very good example of this is the SOS Costa Brava, a platform born in August 2018 with 16 initial organizations and, nowadays, more than 30. In less than two years, it has been able to induce a regional planning process by the Catalan Government aiming at downscaling the urban growth potential by more than 15,000 units (mainly secondary residences). The second subtype is for the “historic organizations”. When small groups need support in technical and legal affairs, in reaching the media or the authorities, in organizing activities, etc, they reach out to these organizations seeking for guidance, assistance, or simply for the co-signature of their demands, as this empowers their cause in front of society and the governmental institutions. In fact, all plural platforms usually take off after these structuring organizations have endorsed them, and very often they become the pillar on which the campaign develops in the long-run. Historic organizations are very few, but have a solid trajectory of 30 to 40 years. Even so, in practice, mainly two organizations—IAEDEN–Salvem Empordà and Associació Naturalistes de Girona—have been the nodes sustaining the whole network for more than 20 years.

Future research in archives or through interviews may reveal information about unregistered organizations, or conclude that the proposed categories or the typology assigned to a certain movement should change, producing certain variation in these results. Nevertheless, main conclusions about the high density of environmental movements in Girona, their continued presence throughout time, and their structure based on strong historic nodes, local groups, temporary movements, and larger-scale/long-term unifying platforms, are expected to remain unchanged. Even so, the forthcoming application of Actor-Network Theory and Social Networks Analysis methods will deepen the understanding of the movements as a system (their activities, interactions, etc.) and make results more comparable with other territories (e.g., waste pollution network in Campania, Italy [

38])

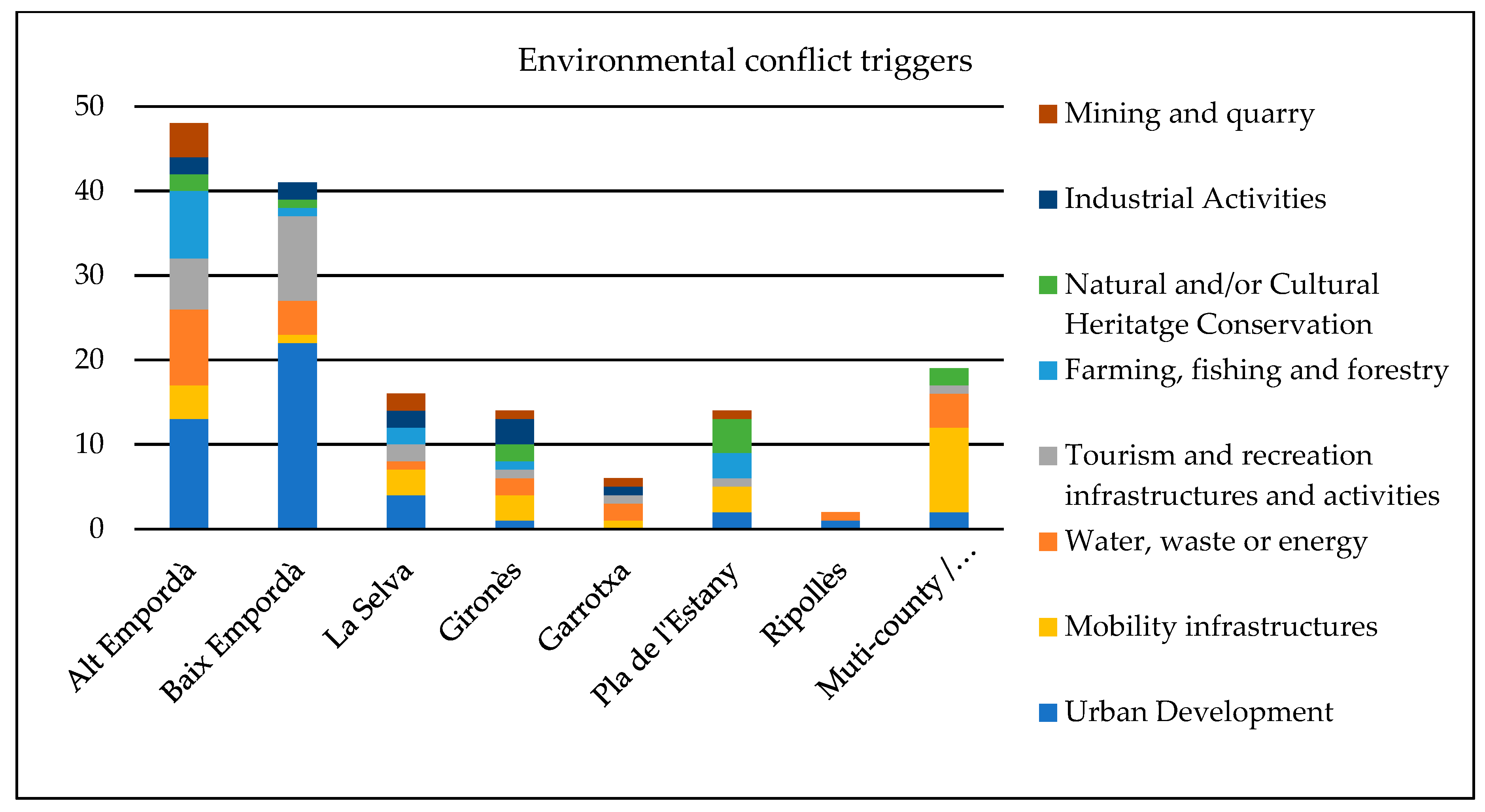

5.2. Environmental Conflicts: Map, Tipology and Impact

To date, the record of environmental conflicts in Girona contains 160 cases since 1970, which breaks down to an average over 30 cases per decade (

Supplementary Materials).

Figure 4 lays out the territorial distribution of conflict triggering plans, projects or activities. urban development is the principal source of mobilizations, with 45 cases (28%), followed by mobility infrastructures (16%); next are water, waste or energy infrastructures, facilities and activities (14%); and in fourth place tourism and recreation infrastructures and activities (14%). These four modalities concentrate almost 3/4 of the conflicts in Girona since 1970, manifesting the strong character of the region as a recreational–touristic destination and passage territory.

It is worth noting that 66% of the cases (105 in total) take place in the three counties of the Costa Brava (Alt Empordà, Baix Empordà, La Selva), compared to 22% in the three interior counties (Garrotxa, Pla de l’Estany and Ripollès), 14% in Gironès; and 12% in more than one county. Coastal counties aggregate 39 out of 45 (87%) urban development conflicts, and 18 out of 22 (82%) for those related to tourism and recreation infrastructures and activities, showing the intertwined functioning of mass tourism specialization and the construction sector.

Figure 5 explains the current status of each case. Adding up saved and partially/provisionally saved landscapes, it is remarkable that 58% of the conflicts (92 out of the 160) have ended in either one of these categories (saved 42%, and partially/provisionally saved 16%).

A mere 13% corresponds to “defeats”, with the development of the plan, project or activity in its full extent and impact. Another 30% of the cases (46) are currently active conflicts, as proof that tension over landscape quality and conservation is a constant feature of territorial and socioecological dynamics in Girona. A total of 77% of the ongoing conflicts take place in the Costa Brava counties (and almost half in Baix Empordà), explaining why local environmentalist groups joined into the SOS Costa Brava platform in 2018. Of the 20 “lost landscapes” in

Figure 5, 17 belong to conflicts related to infrastructures, for either mobility, or for water, waste or energy provisioning. Sustained by existing sectoral plans and often declarations of public interest, these projects obtain powerful momentum—in form of top-down political and economic support, even at the European level; e.g., the High-Speed Train or the Very High Voltage power lines—which translates into a much lower mobilization effectiveness, compared to social opposition against discrete projects dependent on local decision-making and competencies.

To better show the geographical spread of the conflicts, two maps were generated.

Figure 6 presents a map with their location and status, and

Figure 7 their dispersion according to a Kernel Density analysis. Aggregated distribution reconfirms the notion that the Costa Brava is Girona’s most important hotspot for territorial conflicts and environmental mobilizations. The 22 municipalities on the coastline make up 36% of the conflicts (57 cases) since 1970. Hence, from 208 municipalities all across the region, more than one third of the tension concentrates in one tenth of the territory in administrative terms.

The Kernel Density map in

Figure 7 shows the gradual reduction in conflicts in a coast to inland direction, expressing the regional economic and development effect of the Costa Brava. Case by case, an additional 13% of conflicts (21) can be directly related to it. These are detached-housing projects —sometimes including an airfield, a golf course, a spa, etc.; recreational theme parks; power lines or road-splitting projects serving to the coast; etc. In sum, the Costa Brava has had an influence on half of the environmental conflicts in the last 50 years, but, thanks to the presence of active citizenship, half those have ended in saved or partially/provisionally saved landscapes. Two additional focuses appear in

Figure 7: one in the urban area of Girona, as paramount development hub of the region; the other in Pla de l’Estany, where different urban and industrial settlements coincide with a high concentration of rare water-ecosystems in a very small flatland.

Based on the status of the conflicts in the past five decades (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), the authors sustain that Girona’s environmental activism has been significant for landscape conservation. In the majority of cases it led to dropping, stopping, or improving plans, projects or activities that, otherwise, would have had relevant impacts on the region’s landscape and environment. On the other hand, in cultural terms, preserving these landscapes, ordinary or “pristine”, through mobilizations was essential for building and feeding a strong

territoriality; i.e., the empowerment embedded in the identity of a community that makes it react when environmental threats appear [

39].

In regards to the actual ecological footprint prevented, in the future the ongoing research will quantify data about hectares of open spaces maintained and, inherently, their ecosystem services, housing units and Km of new roads avoided, etc.

For a first approach to the territorial impact of mobilizations,

Figure 8 displays a preliminary analysis of the conversion rate of conflict areas to land use protection figures. It turns out, with the available data, that at least in 46 conflicts (29%) the outcome was the approval of some type of land use or heritage figure valorizing the existing land use and impeding significant transformations. This can be at municipal (e.g., forest or farming value land; protected green area; local catalogue of protected buildings), Catalan (e.g., Natural Park; Natural Interest Space; Cultural Good of National Interest), Spanish (e.g., Picturesque Landscape, terrestrial-maritime public domain), or even international level (Nature 2000 area; Ramsar wetland; etc.). In 31 additional cases (19%), the conflict was sparked in an area with pre-existing protection. Here, activism had the aim of enforcing the legal status of that area, with a specific balance of 12 saved or partially/provisionally saved landscapes, 15 ongoing conflicts and four lost. Thus, in close to 50% of the conflicts (77 out of 160), activism means more territory and heritage (including single sites or elements) under protection figures, or deals with those areas that are regulated. For the authors, this represents an opening gap between the environmentalist movement in Girona and mere NIMBY groups, as among the outcomes of territory defense, mobilizations are common goods for the whole of society.

Table 3 collects a number of conflicts, their most relevant resolution milestones and current legal status. A detailed description of the action repertoire of the mobilizations has been ignored on purpose, because what is relevant for the authors is their “butterfly effect”. In short, the action repertoire has always been mainly contained, with a few transgressive exceptions (e.g., land occupation in the Aiguamolls de l’Empordà) when referring to the corresponding literature [

40]. Contained action includes: filing technical-legal allegations; collecting support signatures; legal performances or rallies; political influence (Council/Parliament motions, etc.); public opinion support; court appeals; fundraising, etc. In turn, milestones in

Table 3 represent political decision-making, legal-judiciary responses, and unexpected events key to the evolution of the case (e.g., s’Alguer: the death of Franco; La Pletera: bankruptcy of the investing company). In very few cases the transition from a threatened area to a non-developable/protection figure was almost immediate (e.g., Pinya de Rosa and Cap Ras). Generally, after the conflict ignites, a long social, political-legal and court process develops, until the area is finally permanently protected. In some cases, more than 20 years passed since the first social mobilizations began and the approval of a legally binding zoning, impeding the original threat or other future changes (e.g., La Pletera). Thus, the conflict acts as a governance mechanism to raise understanding of the values (tangible and intangible) of the threatened place, halt administrative procedures, or construction works, and allow society and the different powers to discuss and establish what is the proper solution for that specific piece of land.

As the Discussion will present, mobilizations have also fueled the evolution of the policy framework; thus, they behave as a regime-changing catalyst. However, the amount and extensive timespan of environment and landscape conflicts in Girona region, may also be understood as a sign of subjacent governance weakness. In other words, after five decades of conflicts, it appears that governmental institutions have not been able to develop more collaborative forms of landscape governance, capable of producing a culture of cessions, tradeoffs and agreements on land planning and management, instead of recurrent disputes due to confronted interests.

6. Discussion

What explains the amount and continuity of environmental movements and mobilizations in the region of Girona? What is their political opportunity framework? How have these movements influenced the territory’s governance, planning and development? Answering these questions requires to look back onto the region’s transformation process occurred in the last 50-70 years, for the intertwined relationship between development cycles, mobilizations—as an expression of civil rights and local identity—and spatial planning policies.

After an initial period of landscape and heritage praise and valorization movements of the first decades of the 1900s, a long lapse of silence followed under Franco’s dictatorship, until the 1950s and 1970s with the period called

“Desarrollismo”. Accelerated economic growth took place in certain territories, remarkably linked to the irruption of tourism as economic engine and supported by a significant leap in infrastructures; in Girona, the construction of the Girona-Costa Brava airport (inaugurated in 1967) and the E15 highway connecting to France (with international service as of 1976). This had strong territorial and landscape impact, with deep transformations on both natural–rural environments, and urban and peri-urban areas [

25]. As in many other places, what constituted and attraction for visitors turned into a victim of its “success”. This took place in a context of speculation, corruption and altering urban planning—where it existed—without a square meter of protected land, and in an authoritarian regime with neither power division, nor democratic control by the citizenship [

25].

In the 1970s, with the decay of the dictatorship, qualified as corrupt, speculator and anti-Catalan, first expressions of nature defense groups appeared, integrated in wider anti-Franco and pro-democracy movements. Among the environmental mobilizations of that period, three of them reached outstanding social and media repercussion, and became milestones in the recent history of Girona. They are the Costa Brava Debate, and the campaigns for the protection of the Alt Empordà Wetlands and the Volcanic Area of La Garrotxa; all of them from the period 1975-1976. The Costa Brava Debate, promoted by local authorities, meant opening the issue of land planning and management to all stakeholders; moving it from closed technical–political offices to the public agora [

41]. The two nature protection campaigns, represented the empowerment of a young generation of biologists, geologists, geographers, architects, economists, etc., and the “devolution” of power to the people. Power to question a development model (e.g., mass tourism and industrial activities) was exhausted, in the context of the impact of the 1973 oil crisis, in the eyes of a greater proportion of inhabitants. In addition, these fights led to the declaration of two of the first Natural Parks in Catalonia (the Garrotxa Volcanic Area Park in 1982 and the Alt Empordà Wetlands in 1983), and were the precursor to the birth of Girona’s oldest environmentalist organizations, with 30 to 40 years of activity to date, some of which remain as referents and structuring nodes for the whole movement at county or regional level (IAEDEN–Salvem Empordà, 1980 and Associació Naturalistes de Girona, 1981).

With the transition to democracy and elections at state, municipal and autonomous community levels between 1977 and 1980, the logical expectation aroused: if speculation was a consequence of Francoism, it would end with the causal problem. In fact, some protagonists of the mobilizations became political or technical managers of the new democratic moment, with urban planning among their most explicit priorities as an instrument to improve the living conditions and the protection of the territory. Thereby, an extraordinary planning effort took place during the 1980s and 1990s, and the urban improvements were evident [

42].

Nevertheless, after a vigorous period of activity in the construction sector between 1987–1992, that ended with a recession following the Olympics Games in Barcelona, it became obvious that, despite the new urban plans of the democratic period, the inheritances of the plans from Francoist times were manifold, especially in terms of land programmed as developable emerging with the new growth. Likewise, it was realized that speculation was not an authoritarian regime logic only, but a practice acting on and influencing democratic urban developments as well; triggering a new wave of environmental conflicts against housing projects, marinas, roads, etc., such as the campaign against urbanizing Castell beach in Palamós (1992–2002), highlighted by a local referendum in 1994 and a Supreme Court sentence in 2001 protecting it (

Table 3). It was evident, then, that an intense territorial transformation processes would continue to be present in a region marked by real estate economics and a strategic geographical location, in a country wanting to catch (economically) its continental neighbors, and position itself in the globalization of the economy. In effect, a new growth cycle took place between 1998 and 2007, of unprecedented magnitude. On average, 14,000 new housing units were started every year—threefold that of the previous period—matching in absolute terms the average annual demographic growth of the decade—mainly, migrants getting jobs in the construction sector [

22]. This frenzy collapsed with the international financial crisis in 2008, leading to a subsequent decade in which yearly construction stayed below 2000 new dwellings in nine out of the 10 years [

43]. Paradoxically, social housing remained in stagnant levels for the whole 1992-2018 timespan, falling from a maximum of 1500 new units in 1995 to near 0 between 2012 and 2018 [

43]. Today’s outcome of this trajectory is a territorial model with 4.8% built-up land (and potential to reach 6.6%) [

44]; housing stock far beyond demographic necessities (in 2019 +517,000 housing units for a population of 756,193; a ratio of 0.68) [

43]; more than 300 industrial areas, 40% of which empty, in a region with little more than 200 municipalities [

45]; near half the recreational sailing moorings in Catalonia [

46].

Throughout these three cycles of growth and crisis, environmental activism was deeply rooted and spread in Girona’s society, building the cohesive and robust network needed for ecologically sound transformations to progress [

38]. Awareness about the quality and value of landscape became part of a social

milieu, ready to react when transformations were done at an accelerated pace or affected spaces that, in a new context of values, made sense from the point of view of local identity or sustainability. However, the usual case-by-case advocacy reaction, despite necessity, was unintelligent from a territorial model perspective. At the turn of the century, a tipping—and maturing—point in the action repertoire of the movements occurred, by which regenerative action became central to their demands through the proposition of wide-ranging alternatives.

In 2001, the structuring organization Associació Naturalistes de Girona initiated a long-term collaboration (2001–2009) with the Province Council that delivered, through successive studies, a regional catalogue of nature and landscape interest spaces, covering and describing the values of 280,000 Ha of land that had been ignored by Catalonia’s Natural Spaces Interest Plan (1992) and Nature 2000 Network (2006) [

47] despite their ecological interest. As the Province Council has no competencies of land planning, this catalogue couldn’t go beyond the category of a not binding study. Still, the document became a fundamental source for the Landscape Catalogue of Girona Counties prepared by the Landscape Observatory of Catalonia, and approved by the Public Works and Territory Policy Department of Catalonia in 2010 [

23].

In parallel, in 2002, IAEDEN–Salvem Empordà—the other flagship organization in the region— deployed a county scale campaign petitioning for a regional Director Plan, after listing a full set of plans and projects threatening the landscape and different natural areas of the two Empordà counties (Alt and Baix) [

37]. It was a sound campaign with dozens of local assemblies and many protest actions. The Catalan Government had no other possible answer than to embrace the demand. Background studies on the Director Plan started by the end of 2002 and the initial approval in May 2004 [

32]. A Director Plan that was the kick-off of an extensive regional planning policy at Catalonian level, including, among others, two Urban Master Plans of the Coastal System (2005)—which protected 9123 ha along a 500 m fringe of coastline, and declassified 267 ha of developable land—and a Territorial Partial Plan (2010) and the aforementioned Landscape Catalogue (2010) for the whole of the region of Girona. Until then, urbanistic growth had been planned by local governments only (despite the plans’ final approval is done by the Territory Department of the Catalan Administration). With this new regional planning policy, a renovated and more comprehensive vision of the territory was endorsed, with the idea of tackling both planning failures (i.e., excessive growth potential) embedded in local plans, and insufficient integrated environmental planning (e.g., conservation of nature and landscape values). Even so, the outcomes of these regional plans were severely questioned. In 2006, different environmental NGOs—among which, once more, the Associació Naturalistes de Girona—created the Sustainability Observatory for the Region of Girona. With the support of the Province Council, this independent civil-society-based body produced the first sustainability reports at regional scale. Regarding the Territorial Plan of 2010, these studies criticized the fact that growth prospects were still excessive, allowing a 30% increase in built-up land and 22% in housing by 2026, compared to 2008; i.e., from 495,000 to 603,000 dwellings, for a territory with a projected population of 826,000 (leading, if fulfilled, to the growth of the dwellings-per-inhabitant ratio up to 0.73 at the end of the period). The reports also pinpointed that planning and management of protected areas were far behind what was stated in the Nature Interest Plan of 1992, and proved the correlation between population increase and landscape fragmentation (i.e., the reduction in and loss of continuous open spaces, due to more infrastructures, urbanization, etc.) [

22].

In 2008, with the financial crisis, economic activity in all kinds of construction activities came close to a full stop, especially in real estate. The causal relationship between the construction bubble and economic collapse in Spain was so largely discussed that the notion that that model was a thing of the past conquered public opinion. In Catalonia, as in the previous recession cycles, the crisis was just a stand-by lapse, instead of a period for reviewing land and urban planning and aiming for a more sustainable model. A new boom of residential projects began in 2018, especially on some of the last well-preserved sites of the Costa Brava (e.g., sa Guarda in Cadaqués, Pineda d’en Gori in Palamós, cala El Golfet in Palafrugell, sa Riera and Aiguafreda in Begur, La Morisca in Tossa de Mar) [

48]. Environmental movements reacted fast and loudly by uniting under the SOS Costa Brava platform, and became tightly interconnected, as was also reported in Italian Catania with the waste-related crisis spanning since 1994 [

38]. This new platform, founded in August 2018 by 18 organizations (currently more than 30) made an inventory of conflicts and initiated an awareness of and legal opposition campaign against seven specific cases (that after grew to 16), and raised the essential claim that sustainable urban development principles collected in the legislation be effectively enforced. This refers to not allowing building on land with slope above 20%; on forests; when geological, flood, or wildfire risk is present; in conditions of high visual or landscape impact; on maritime-terrestrial public domain (or its protection fringe); on nature protection areas; when water availability is not granted; etc. In order to extensively implement these principles, SOS Costa Brava demanded the Territory and Sustainability Department to submit an Urban Master Plan for the Costa Brava, with the main aim of analyzing in detail the urban plans of the 22 shoreline municipalities and proceed to their revision, by declassifying and cancelling all sectors that would not be legal if zoning be done at present times, instead of 30 years back, or inherited from the pre-democratic period.

The impact of SOS Costa Brava’s campaign was so intense—news every other day and several international reports and TV documentaries—that three months after the birth of the platform the Catalan Government announced it, they started working on the Urban Master Plan. By January 2019, the plan draft was officially presented, justified by the “urban pressure” and “higher percentage of already transformed land” on the Costa Brava, while “both the coastal legislation and the documents of the coast (Urban Master Plan of the Coastal System, Landscape Catalogue, etc.) provide for more careful treatment to safeguard the identity and the landscape of this space” [

44] (p. 2). Two building moratoriums were passed in parallel, putting a break on several cases the platform had appealed against. The initial approval of the Plan from December 2019 reviewed 202 development sectors in conflict with regulated sustainability principles, proposing to fully declassify 91 of them (return to non-developable land) and reduce the other 50. In total, +15,000 housing units cancelled and +1200 Ha of land to remain unbuilt [

49]. SOS Costa Brava estimated the total residential growth potential on 50,000 dwellings and considered the plan “a first necessary step ahead, but manifestly insufficient” in the direction of sustainable land planning [

50].

For the authors, Girona’s environmental mobilizations have clearly influenced the sustainability of land planning and management policies in this territory, yet it also signposts a reality of very weak collaborative landscape governance practice. In a sort of

Groundhog Day, or

Sisyphus tale, Girona appears to need environmental activism to face cyclic landscape degradation and implement sustainability measures. Nel·lo, argues that the contemporary boom in environmental activism is related to several types of difficulties of classical representation and decision-making mechanisms [

51]. For Brenner, this is due to governments’ and parties’ legitimacy crisis caused by the rescaling derived from globalization [

52]. In Girona, in addition, environmental movements appear to have become the bearers of a historical territoriality based on the landscape, which carries a much deeper standpoint than NIMBY movements: a territoriality—topophilia, territorial identity, landscape

thickness— deeply rooted in the values of society. This departs from saying "No" as a prelude for giving space to a

project identity willing to say "Yes" to the structural and qualitative development of the territory [

53]. When the expansion and crisis cycles of the current economy of growth model are leading humankind to the tipping points of planetary sustainability [

5,

54], resistance seems to be an essential step for the emergence of pathways to a new post-growth paradigm and to long-term socioecological resilience delivered by multifunctional landscape management based on co-evolutive and adaptive mechanisms promoted by place attachment [

55].

Collaborative governance processes, as defined by Emerson and Nabatchi (2015) [

56], are the challenge for the future. The Landscape Law of Catalonia of 2005 meant enormous progress with the creation of the Landscape Charter figure, an instrument for bottom-up collaborative and agreement-based local landscape planning [

57]. Development of these charters is, however, voluntary and, to date, rare in the whole of Catalonia. As Beery et al. (2015) raise, “nurturing potential topophilic tendencies may be a useful method to promote sustainable efforts at the local level with implications for the global” [

55] (p. 8837). Environmental activism is contributing to this cultural nursery and, hopefully, this will prompt the collaborative governance of local and regional planning as the new normal.