Land Consolidation at the Household Level in the Red River Delta, Vietnam

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Land Consolidation and Policies

2.1. Around the World

2.2. In Vietnam

2.2.1. National Policies

2.2.2. Current Situation of Land Consolidation in Vietnam and the Red River Delta

3. Case Studies and Methodologies

3.1. Case Studies

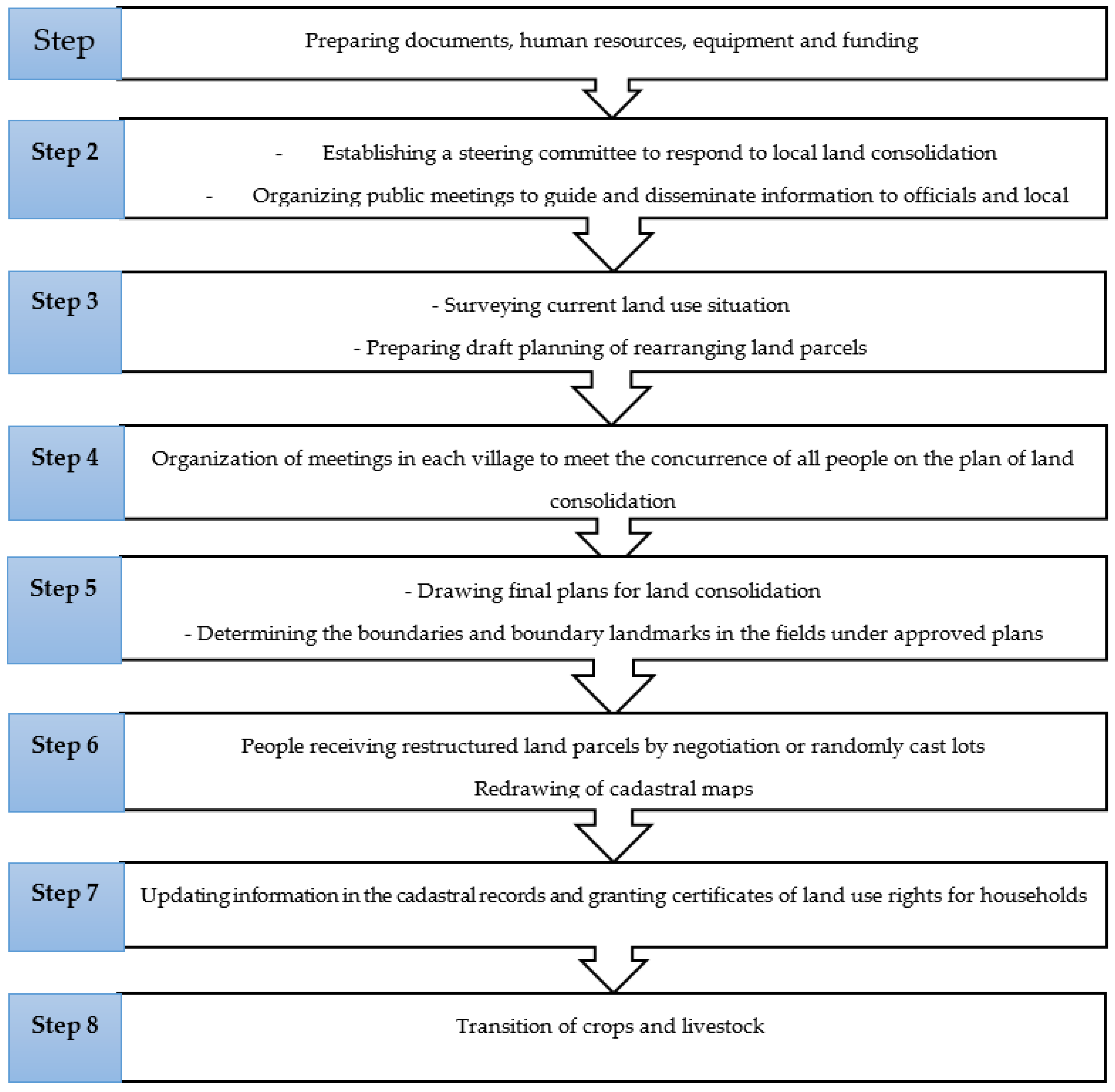

3.2. Land Consolidation Process in the Research Areas

3.3. Research Methodology

4. Research Results

4.1. Expanding the Land Area of Farm Households

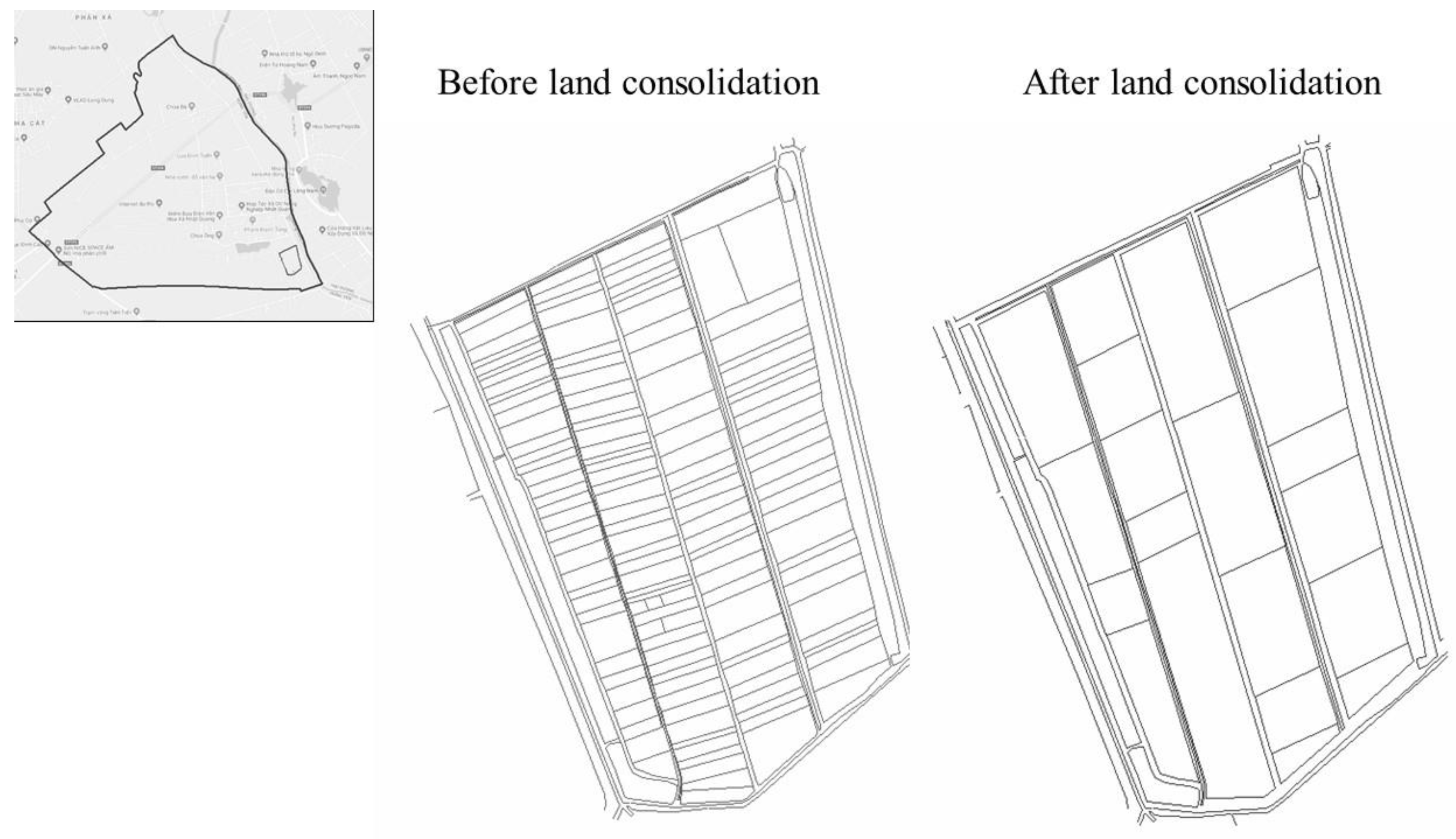

4.2. Changes in the Spatial Structure of Land Parcels

4.3. Changes in Crop Structure, Increase in Household Income, and Provision of More Opportunities for Larger-Scale Agricultural Production

4.4. Accelerating Mechanization in Agricultural Production

4.5. Create More Job Opportunities for Agricultural Laborers

4.6. Farmers’ Positive Perception of Land Consolidation

5. Discussion

5.1. Inadequacies of the Land Consolidation Process

5.2. Land Consolidation Should be an Integrated Process of Multiple Policies

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colombo, S.; Perujo-Villanueva, M. A practical method for the ex-ante evaluation of land consolidation initiatives: Fully connected parcels with the same value. Land Use Policy 2019, 81, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarosław, J.; Magdalena, Ł.; Ewa, J. Land Consolidation in Mountain Areas – Case Study from Southern Poland. Geod. Cartogr. 2017, 66, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Huu Quynh, N.; Peter, W. Land Consolidation as Technical Change: Impacts on-Farm and off-Farm in Rural Vietnam; ANU College of Asia and the Pacific: Canberra, Australia, 2018; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Hiironen, J.; Riekkinen, K. Agricultural impacts and profitability of land consolidations. Land Use Policy 2016, 55, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, P. The Role of Land Use Consolidation in Improving Crop Yields among Farm Households in Rwanda. J. Dev. Stud. 2019, 55, 1726–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Zhu, F.; Chen, F.; Yu, M.; Zhang, S.; Yang, Y. Assessing the Impacts of Land Consolidation on Agricultural Technical Efficiency of Producers: A Survey from Jiangsu Province, China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pašakarnis, G.; Maliene, V. Towards sustainable rural development in Central and Eastern Europe: Applying land consolidation. Land Use Policy 2010, 27, 545–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Guidance Note C: Ex-Ante Evaluation Guidelines Including SEA. Communities; 566 Office for Officials Publications of the European Communities, Ed.; European Commission: Luxemburg, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Agricultural Policies in Vietnam; OECD: Paris, France, 2015; p. 239. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Vietnam’s Agricultural Growth: Increasing Value, Reducing Inputs; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Transforming Vietnamese Agriculture: Gaining More for Less; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Anh Tuan, T. Institutional Analysis of the Comtemporary Land Consolidation in the Red River Delta: A Village-Level Study of Dong Long Commune in Tien Hai District, Thai Binh Province, Vietnam. J. Jimbunchiri 2006, 1, 20–39. [Google Scholar]

- Thi Thu Thao, X.; Xuan Phuong, H.; Thi Lam Tra, H. Efficient use of farm land after the process of agricultural land accumulation in Nam Dinh province. J. Rural Dev. Agric. 2015, 19, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hung, P.; MacAulay, T.G.; Marsh, S.P. The Economics of Land Fragmentation in the North of Vietnam. Austral. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2007, 51, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, S.P.; MacAulay, T.G. Farm Size and Land Use Changes in Vietnam Following Land Reforms. In Proceedings of the the 47th Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society, Sydney, Australia, 12–14 February 2003; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- Quy-Toan, D.; Lyer, L. Land Rights and Economic Development: Evidence from Vietnam; World bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The Design of Land Consolidation Pilot Projects in Central and Eastern Europe; FAO: Rome, UK, 2003; p. 55. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Resler Lynn, M.; Campbell James, B.; Chen, G.; Zhou, Y. The evaluation of land consolidation policy in improving agricultural productivity in China. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. FAO’s Land Tenure Service of the Rural Development Division. Available online: http://Fao.org (accessed on 4 November 2019).

- Chunfa, W.; Jingyi, H.; Hao, Z.; Limin, Z.; Budiman, M.; Ben, P.M.; Alex, B.M. Spatial changes in soil chemical properties in an agricultural zone in southeastern China due to land consolidation. Soil Till. Res. 2019, 187, 152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Zahra, K.; Alireza, K. Land consolidation and its economic effects on the city district of Loutak_Zabol. Int. J. Econ. Res. 2012, 3, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.; Heerink, N.; Qu, F. Land fragmentation and its driving forces in China. Land Use Policy 2006, 23, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaian, P.; Guri, F.; Rajcaniova, M.; Drabik, D.; Paloma, S.G.Y. Land fragmentation and production diversification: A case study from rural Albania. Land Use Policy 2018, 76, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crecente, R.; Alvarez, C.; Fra, U. Economic, social and environmental impact of land consolidation in Galicia. Land Use Policy 2002, 19, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayılan, H. Importance of Land Consolidation in the Sustainable Use of Turkey’s Rural Land Resources. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 120, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Jin, X.; Yang, X.; Guan, X.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, Y. Determining the effects of land consolidation on the multifunctionlity of the cropland production system in China using a SPA-fuzzy assessment model. Eur. J. Agron. 2015, 63, 12–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiama, K.; Bennett, R.; Zevenbergen, J. Towards Responsible Consolidation of Customary Lands: A Research Synthesis. Land 2019, 8, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathiresan, A. Farm Land Use Consolidation in Rwanda; Ministry of Agriculture and Animal Resources: Kigali, Rwanda, 2012; p. 45. [Google Scholar]

- Borsellino, V.; Di Franco, C.; Schimmenti, E.; Asciuto, A.; Di Gesaro, M.; D’Acquisto, M. Land consolidation policies in Sicily and their effects on its farmland. Calit. -Acces La Succes 2014, 15, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Phuc, T.; Mahanty, S.; Wells-Dang, A. From “Land to the Tiller” to the “New Landlords”? The Debate over Vietnam’s Latest Land Reforms. Land 2019, 8, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. Land law 1993. 1993. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Bat-dong-san/Luat-Dat-dai-1993-24-L-CTN-38481.aspx (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Secretariat of the Communist Party of Viet Nam. Resolution No. 06-BCT, Resolution on Some Issues of Agriculture and Rural Development. 1998. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Linh-vuc-khac/Nghi-quyet-06-NQ-TW-van-de-phat-trien-nong-nghiep-nong-thon-112629.aspx (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Prime Minister of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. Directive No 10/1998/CT-TTg Instruction for Strengthening and Completing the Lallocates Land, Granting Certificates of Right for Use of Agricultural Land. 1998. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Linh-vuc-khac/Nghi-quyet-06-NQ-TW-van-de-phat-trien-nong-nghiep-nong-thon-112629.aspx (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Prime Minister of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. Directive No. 18/1999/CT-TTg, On a Number of Measures to Promote the Grant of Certificates of Right to Use of Agricultural, Land in RURAL areas in 2000. 1999. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Bat-dong-san/Chi-thi-18-1999-CT-TTg-bien-phap-day-manh-hoan-thanh-cap-giay-chung-nhan-quyen-su-dung-dat-nong-nghiep-dat-lam-nghiep-dat-o-nong-thon-2000-45410.aspx (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Prime Minister of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. Resolution No. 03/2000/NQ-CP on Farm Economics. 2000. Available online: http://www.chinhphu.vn/portal/page/portal/chinhphu/hethongvanban?mode=detail&document_id=7274 (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Prime Minister of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. Decision 80/2002/QD-TTg on Policy to Encourage Agricultural Products Consumption through Contract. 2002. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Linh-vuc-khac/Quyet-dinh-80-2002-QD-TTg-chinh-sach-khuyen-khich-tieu-thu-nong-san-hang-hoa-thong-qua-hop-dong-49655.aspx (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- The National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. Land law 2003. 2003. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Bat-dong-san/Luat-Dat-dai-2003-13-2003-QH11-51685.aspx (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- The Central Committee of the Communist Party of Viet Nam. Resolution No 26/NQ/TW7 on Agriculture, Farmers and Rural. 2008. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Linh-vuc-khac/Nghi-quyet-26-NQ-TW-nong-nghiep-nong-dan-nong-thon-69455.aspx (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Prime Minister of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. Decision 491/QD-TTg on the National Criteria for Building NEW countryside. 2009. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Van-hoa-Xa-hoi/Quyet-dinh-491-QD-TTg-Bo-tieu-chi-quoc-gia-nong-thon-moi-87345.aspx (accessed on 31 May 2020).

- Central Committee of the Communist Party of Viet Nam. Resolution No.19-NQ/TW the Sixth Conference, Central Committee of the Communist Party of Vietnam Course XI. 2012. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Bat-dong-san/Nghi-quyet-19-NQ-TW-nam-2012-doi-moi-chinh-sach-phap-luat-ve-dat-dai-171705.aspx (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Prime Minister of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. Decision 62/2013/QD-TTg on Encouraging the Development of Cooperation, Production LINKAGE with agricultural Product Consumption, and Forming Large Fields. 2013. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Thuong-mai/Quyet-dinh-62-2013-QD-TTg-chinh-sach-khuyen-khich-phat-trien-hop-tac-lien-ket-san-xuat-211219.aspx (accessed on 1 November 2019).

- The National Assembly of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Land law 2013. 2013. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Bat-dong-san/Luat-dat-dai-2013-215836.aspx (accessed on 30 October 2019).

- Prime Minister of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. Decree No. 98/2018/ND-CP Regarding Incentive Policy for Development of Linkages in Production and Consumption of Agricultural Products. 2018. Available online: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/thuong-mai/Nghi-dinh-98-2018-ND-CP-chinh-sach-khuyen-khich-phat-trien-hop-tac-san-xuat-san-pham-nong-nghiep-387110.aspx (accessed on 26 April 2020).

- Ban chỉ đạo Tổng điều tra Nông Thôn Nông Nghiệp và Thủy sản Trung Ương. Báo Cáo sơ bộ kết Quả Tổng điều tra Nông Thôn, Nông Nghiệp và Thủy Sản Năm 2016 (Preliminary Report on the Results of the National Rural, Agricultural and Fishery Census); Statistical Publisher: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2016; p. 139. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. Circular 15/2014/BNNPTNT; Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment (MONRE). Tình Hình Tích tụ, tập Trung đất đai cho Phát Triển Nông Nghiệp: Phương Thức, mô Hình Thực Hiện và Các Giải Pháp (Concentrated Land Consolidation Situation for Agricultural Development, Modes, Implementation Models and Solutions); Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ban chỉ đạo tổng điều tra dân số và nhà ở. Kết Quả Tổng điều tra Dân số và nhà ở 2019 (Population and Housing Census 2019); United Nations Population Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- General Statistics Office of Vietnam. National Data Census. Available online: https://gso.gov.vn/ (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Huu Quang, T. Land accumulation in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam: A question revisited. Can. J. Dev. Stud. Rev. 2018, 39, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Jerez, M. The rural transformation of the two rice bowls of Vietnam: The making of a new Asian miracle economy? Innov. Dev. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Transforming Vietnam’s Agriculture: Increasing Value, Reducing Inputs, Vietnam Development Report 2016; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; p. 126. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Chung, D. Land Accumulation and Concentration: Theoretical and Practical Fundamentals for Commodity Oriented Agricultural Development. Vietnam J. Agric. Sci. 2018, 16, 412–424. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Committee of Hung Yen Province. Báo Cáo Thống kê đấT đai Tỉnh Hưng Yên năm 2017 (Land Statistics Report of Hung Yen Province in 2017); People’s Committee of Hung Yen Province: Thành phố Hưng Yên, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Committee of Hung Yen Province. Báo Cáo Tình Hình tập Trung, Tích tụ đất đai để Phát triển sản xuất Nông Nghiệp (Report on the Concentration and Accumulation of Land for Agricultural Production Development); People’s Committee of Hung Yen Province: Thành phố Hưng Yên, Vietnam, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Committee of Vinh Phuc Province. Land Statistics Report of Vinh Phuc Province in 2017; People’s Committee of Vinh Phuc Province: Thành phố Vĩnh Yên, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- DERG; CIEM. Báo Cáo Phân Tích yếu tố ảnh Hưởng tới Phân Mảnh Ruộng đât và các tác động tại Việt Nam—Hỗ trợ Chương Trình Phát Triển Nông Nghiệp và Nông Thôn (Analytical Report on Factors Affecting Land Fragmentation and Impacts in Vietnam—Support for Agriculture and Rural Development Program) (ARD SPS) 2017–2013; NGO Resource Centre: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Committee of Vinh Phuc Province. Báo Cáo Tổng kết Thực Hiện thí điểm Công tác dồn Thửa, đổi ruộng 02 xã Cao Đại và Ngũ Kiên, huyện Vĩnh Tường, bài học Kinh Nghiệm, Nhiệm vụ Thực hiện dồn thửa đổi Ruộng trên địa bàn Tỉnh Vĩnh Phúc (Summary Report on Piloting Land Regrouping in Cao Dai and Ngu Kien Communes, Vinh Tuong District—Lessons Learned, Tasks of Land Regrouping in Vinh Phuc province; People’s Committee of Vinh Phuc Province: Thành phố Vĩnh Yên, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Committee of Vinh Phuc Province. Plan for Implementing Land Consolidation in Agriculture in Vinh Phuc Province; People’s Committee of Vinh Phuc Province: Thành phố Vĩnh Yên, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Committee of Nhat Quang Commune. Báo Cáo Tổng kết Việc ThựC Hiện dồn Thửa đổi Ruộng đất Nông Nghiệp Giai đoạn 2013–2015 xã Nhật Quang (Summary Report on the Implementation of Agricultural Land Regrouping for the Period 2013–2015 Nhat Quang Commune); People’s Committee of Nhat Quang Commune: Thành phố Hưng Yên, Vietnam, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Committee of Minh Hoang Commune. Báo Cáo Tổng kết Thực Hiện dồn Thửa đổi Ruộng xã Minh Hoàng năm 2013–2015 (Summary Report on Land Regrouping Implementation in Minh Hoang Commune in 2013–2015); People’s Committee of Minh Hoang Commune: Thành phố Hưng Yên, Vietnam, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- People’s Committee of Phu Thinh Commune. Báo CáO Tổng kết kết Quả Thực Hiện dồn Thửa, đổi RuộNg Thôn Đan Phượng, xã Phú Thịnh (Summary Report on Results of Land Regrouping in Dan Phuong Village, Phu Thinh Commune); People’s Committee of Phu Thinh Commune: Thành phố Vĩnh Yên, Vietnam, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dinh Bong, N.; Van Dan, D.; Xuan Phuong, H. Pro-poor Policy Options/Vietnam: The Case for Land Consolidation Linked to Labor Transformation; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO): Rome, Italy, 2008; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Thi Minh Khue, N.; Thi Dien, N.; Thi Minh Chau, L.; Philippe, B.; Philippe, L. Leaving the Village but Not the Rice Field: Role of Female Migrants in Agricultural Production and Household Autonomy in Red River Delta, Vietnam. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

| Year of Issued | Name of Policy | Issued Content Related to Land Consolidation |

|---|---|---|

| 1993 | Land Law 1993 [31] | Land consolidation through land users exercising their rights: conversion, transfer, lease, inheritance, and mortgage of LURs. |

| 1998–1999 | Resolution No. 06-BCT [32], Directive No 10/1998/CT-TTg [33], No. 18/1999/CT-TTg [34] | Encouraging local governments and the farmers to participate in plan development and implementation of a program of “Regrouping and rearranging of land parcels” to create larger fields for agricultural production. |

| 2000 | Resolution No. 03/2000/NQ-CP [35] | Encouraging the development of farm economics. |

| 2002 | Decision 80/2002/QD-TTg [36] | Directing the planning of zoning concentrated commodity agricultural regions, favoring advantageous conditions for producers and enterprises to organize agricultural production and make contracts regarding selling commodity agricultural products. This decision inspired the implementation of forming large fields. |

| 2003 | Land Law 2003 [37] | Expanding LURs for people: subleases, donations, guarantees and capital contribution with LURs. |

| 2008 | Resolution No 26/NQ/TW7 [38] | Expanding the duration of LURs; encouraging and promoting land consolidation. |

| 2009 | Decision 491/QD-TTg [39] | Promulgating the national criteria for building a new countryside, in which land use planning and essential infrastructure for agricultural development is the first criterion. Understanding this criterion, land grouping and rearranging had been conducted in several localities. |

| 2012 | Resolution No 19-NQ/TW [40] | Allocating or leasing agricultural land to households and individuals for a longer term than before. In addition, expanding limited land area for LURs based on the specific conditions of each region to enhance the process of land consolidation, gradually forming large fields for agricultural commodity production. |

| 2013 | Decision 62/2013/QD-TTg [41] | Encouraging the development of cooperation, production linkage with agricultural product consumption, and forming large fields. |

| 2013 | Land Law 2013 [42] | Households and individuals may transfer LURs no more than ten times the agricultural land assignment quota, increasing the land use term for the land cultivation of annual crops to 50 years. Enterprises are considered by the State for land allocation or leases based on an approved investment project. The State encourages households and individuals to contribute capital by LURs to project investors. |

| 2018 | Decree 98/2018/ND-CP [43] | Encouraging the development of cooperation and linkages in the production and consumption of agricultural products, in which rearranging fields and expanding the area of concentrated agricultural production region is one of the necessary criteria for a cooperation project. |

| Province | District | Commune | Number of Structured Questionnaires | In-Depth Interviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hung Yen | Phu Cu | Nhat Quang | 52 | 4 |

| Minh Hoang | 33 | 3 | ||

| Vinh Phuc | Vinh Tuong | Ngu Kien | 33 | 5 |

| Cao Dai | 32 | 6 | ||

| Phu Thinh | 22 | 4 |

| No | Question | Phu Cu District | Vinh Tuong District |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | Information about agricultural land of an interviewed household | ||

| Total agricultural area before the latest land consolidation | 100 | 100 | |

| Total agricultural area allocated by the state before the latest land consolidation | 100 | 100 | |

| Total agricultural area rented from 5% communal land before the latest land consolidation | 100 | 100 | |

| Total agricultural area rented from other households before the latest land consolidation | 100 | 100 | |

| Total number of parcels before the latest land consolidation | 97.6 | 100 | |

| An area of the largest parcel before the latest land consolidation | 94.1 | 100 | |

| An area of the smallest parcel before the latest land consolidation | 92.4 | 100 | |

| Type of land use before the latest land consolidation | 100 | 100 | |

| Total agricultural area after the latest land consolidation | 100 | 100 | |

| Total agricultural area allocated by the state after the latest land consolidation | 100 | 100 | |

| Total agricultural area rented from 5% communal land after the latest land consolidation | 100 | 100 | |

| Total area of agriculture rented from other households after the latest land consolidation | 100 | 100 | |

| Total number of parcels after the latest land consolidation | 100 | 100 | |

| An area of the largest parcel after the latest land consolidation | 100 | 99 | |

| An area of the smallest parcel after the latest land consolidation | 100 | 99 | |

| Type of land use after the latest land consolidation | 100 | 100 | |

| Forms of land consolidation | 98.8 | 80.5 | |

| 2.0 | The Degree of Agreement with Each Statement about Economic Benefit from Agriculture | ||

| Do you agree that there is an increase in your benefit from agricultural production after the latest land consolidation? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| In your opinion, how many times do you benefit from agriculture increase after the latest land consolidation (if existing)? | 82.4 | 88.5 | |

| If the total revenue of your households covers 10 points, how much is your benefit from agriculture? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Do you agree that your benefit from agriculture is enough to cover your living expenses? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| 3.0 | Information about Hired Labors for Agricultural Production of an Interviewed Household | ||

| Do you hire regular workers for agricultural production before the latest land consolidation? | 100 | 100 | |

| If yes, how much are the regular workers? | 100 | 100 | |

| Did you hire temporary workers for agricultural production before the latest land consolidation? | 100 | 100 | |

| Did you hire regular workers for agricultural production after the latest land consolidation? | 100 | 98.8 | |

| If yes, how much are the regular workers? | 100 | 98.8 | |

| Did you hire temporary workers for agricultural production after the latest land consolidation? | 100 | 79.3 | |

| 4.0 | The Usage of Machinery for Agricultural Production | ||

| Did your household use plows and harrows on any of your parcels before the latest land consolidation? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Did your household use reapers on any of your parcels before the latest land consolidation? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Did your household use combine harvesters on any of your parcels before the latest land consolidation? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Did your household use cultivator machines on any of your parcels before the latest land consolidation? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Does your household use plows and harrows on any of your parcels after the latest land consolidation? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Does your household use reapers on any of your parcels after the latest land consolidation? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Does your household use combine harvesters on any of your parcels after the latest land consolidation? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Does your household use cultivator machines on any of your parcels after the latest land consolidation? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| 5.0 | The Degree of Agreement with Each Statement about the Effectiveness of Land Consolidation | ||

| Do you agree that land consolidation helps you reduce the traveling time to each land parcel? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Do you agree that land consolidation helps to improve the ability to apply machinery on agriculture? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Do you agree that land consolidation helps to improve the ability to apply high technology? | 97.6 | 97.6 | |

| Do you agree that land consolidation helps to increase the opportunity to stably work for more laborers in agriculture? | 98.8 | 98.8 | |

| Do you agree that land consolidation helps to reduce the amount of pesticides on crops? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Do you agree that land consolidation helps to reduce the amount of inorganic fertilizer on crops? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Do you agree that land consolidation helps to improve the village landscape scenery? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Do you agree that the soil environment can be improved due to land consolidation? | 98.8 | 100 | |

| Do you agree with the local policies on land consolidation? | 98.8 | 100 |

| Case Studies in Phu Cu District | Case Studies in Vinh Tuong District | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the Latest Land Regrouping | Present | Before the Latest Land Regrouping | Present | |

| The total agricultural land area of the interviewed households (m2) | 269,397 | 490,312 | 170,432 | 312,094 |

| Average agricultural land area per a household (m2) | 3367 | 5768 | 1982 | 3587 |

| Average annual cropland area per household (m2) | 3360 | 3765 | 1960 | 2348 |

| Average perennial crop and farmland area per household (m2) | - | 7388 | - | 11,161 |

| Proportion of allocated land area (%) | 96.4 | 66.1 | 97.5 | 56.4 |

| Proportion of rented communal land area (%) | 3.0 | 28.3 | 2.0 | 30.4 |

| Proportion of rented land area from other local households (%) | 0.6 | 5.6 | 0.5 | 13.2 |

| Case Studies in Phu Cu District | Case Studies in Vinh Tuong District | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the Latest Land Regrouping | Present | Before the Latest Land Regrouping | Present | |

| The average area of the largest parcel of a household (m2) | 1521 | 5216 | 500 | 2449 |

| Area of the largest parcel in the research areas (m2) | 4680 | 26,496 | 1800 | 18,000 |

| The average area of the smallest parcel of a household (m2) | 505 | 1747 | 155 | 821 |

| Area of the smallest parcel in the research areas (m2) | 360 | 972 | 144 | 384 |

| The average number of land parcels of a household | 3.7 | 1.3 | 6.2 | 2.4 |

| The largest number of land parcels of a household | 11 | 4 | 12 | 6 |

| The smallest number of land parcels of a household | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| District | Commune | Total Land Area for Consolidation (ha) | The Average Area Per Parcel Before the Latest Land Regrouping | The Average Area Per Parcel After the Latest Land Regrouping | Number of Participating Households in the Latest Land Regrouping |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phu Cu | Nhat Quang | 274.83 | 921.1 | 1794.83 | 1389 |

| Minh Hoang | 322.49 | 1029.6 | 1942.7 | 1249 | |

| Vinh Tuong | Cao Dai | 157.1 | 264.7 | 864.6 | 1034 |

| Ngu Kien | 229.6 | 269.2 | 988.0 | 1405 | |

| Phu Thinh | 19.84 | 234.1 | 1210.3 | 158 |

| The Proportion of Households Mainly Growing Paddy and Annual Crops | The Proportion of Households Mainly Planting Fruit (Perennial Cropland) | The Proportion of Households Mainly Doing Mixed Farms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the Latest Land Regrouping | Present | Before the Latest Land Regrouping | Present | Before the Latest Land Regrouping | Present | |

| Phu Cu | 100 | 42.4 | 0.0 | 12.9 | 0.0 | 44.7 |

| Vinh Tuong | 100 | 87.4 | 0.0 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 9.2 |

| Crops | Average Gross Profit (1000 VND/ha/Year) | Initial Investment (1000 VND/ha) | Years Spent to Harvest (Year) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phu Cu | Vinh Tuong | Phu Cu | Vinh Tuong | ||

| Two-crop paddy | 13,811 | 11,800 | - | - | - |

| Two-crop paddy + wax gourd (winter season) | 53,612 | 49,675 | - | - | - |

| Two-crop paddy + maize (winter season) | 29,185 | 27,730 | - | - | - |

| Banana trees | 85,146 | 72,480 | - | - | 1 |

| Orange trees | 258,000 | - | 180,603 | - | 3 |

| Grapefruit trees | 246,440 | 164,440 | 80,678 | 55,640 | 3 |

| Longan fruit trees | 173,780 | - | 45,676 | - | 3 |

| Lychee tree | 128,950 | - | 65,889 | - | 3 |

| Used Plows and Harrows | Used Reapers | Used Harvesters | Used Cultivator Machines | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phu Cu | Before the latest land consolidation | 50.6 | 17.7 | 11.4 | 1.3 |

| After the latest land consolidation | 91.4 | 88.6 | 51.4 | 11.4 | |

| Vinh Tuong | Before the latest land consolidation | 70.9 | 25.6 | 7.0 | 17.4 |

| After the latest land consolidation | 96.1 | 89.5 | 56.6 | 50 |

| The Proportion of Households Hiring Permanent Agricultural Labors (%) | The Average Number of Permanent Hired Labors/Household | The Proportion of Households Hiring Seasonal Agricultural Labors (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before the Latest Land Regrouping | Present | Before the Latest Land Regrouping | Present | Before the Latest Land Regrouping | Present | |

| Phu Cu | 1.2 | 5.9 | - | 2.4 | 9.4 | 54 |

| Vinh Tuong | 0 | 3.4 | - | 1.3 | 14.9 | 30 |

| Degree of Agreement | Phu Cu District | Vinh Tuong District | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local policies and implementation plans | Strongly agree | 50 | 59.8 |

| Agree | 45.2 | 40.2 | |

| Disagree | 2.4 | 0.0 | |

| Reduction in the field traveling time | Strongly agree | 48.8 | 47.1 |

| Agree | 48.8 | 49.4 | |

| Disagree | 1.2 | 1.1 | |

| Increased probability of applying mechanization in cultivation | Strongly agree | 35.7 | 43.7 |

| Agree | 59.5 | 54.0 | |

| Disagree | 3.6 | 1.1 | |

| Improvement in the scenery of the village landscape | Strongly agree | 36.9 | 60.9 |

| Agree | 57.1 | 35.6 | |

| Disagree | 2.4 | 3.4 | |

| Improved soil quality | Strongly agree | 48.8 | 65.5 |

| Agree | 45.2 | 8.0 | |

| Disagree | 2.4 | 10.3 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nguyen, T.H.T.; Thai, T.Q.N.; Tran, V.T.; Pham, T.P.; Doan, Q.C.; Vu, K.H.; Doan, H.G.; Bui, Q.T. Land Consolidation at the Household Level in the Red River Delta, Vietnam. Land 2020, 9, 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9060196

Nguyen THT, Thai TQN, Tran VT, Pham TP, Doan QC, Vu KH, Doan HG, Bui QT. Land Consolidation at the Household Level in the Red River Delta, Vietnam. Land. 2020; 9(6):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9060196

Chicago/Turabian StyleNguyen, Thi Ha Thanh, Thi Quynh Nhu Thai, Van Tuan Tran, Thi Phin Pham, Quang Cuong Doan, Khac Hung Vu, Huong Giang Doan, and Quang Thanh Bui. 2020. "Land Consolidation at the Household Level in the Red River Delta, Vietnam" Land 9, no. 6: 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9060196

APA StyleNguyen, T. H. T., Thai, T. Q. N., Tran, V. T., Pham, T. P., Doan, Q. C., Vu, K. H., Doan, H. G., & Bui, Q. T. (2020). Land Consolidation at the Household Level in the Red River Delta, Vietnam. Land, 9(6), 196. https://doi.org/10.3390/land9060196