Experimental Investigation on the Cooling and Inerting Effects of Liquid Nitrogen Injected into a Confined Space

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

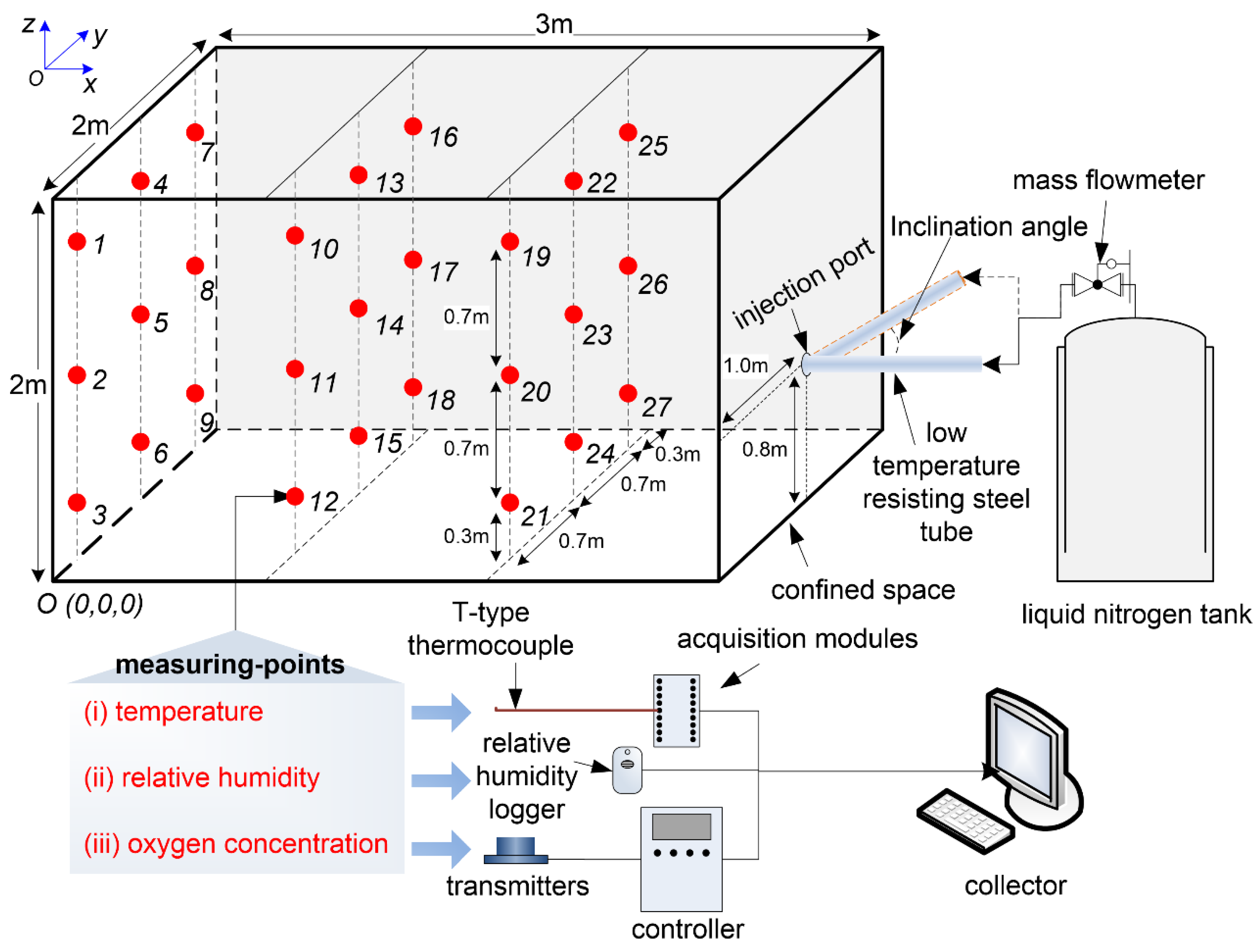

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Experimental Method

2.3. Modeling

3. Results and Discussion

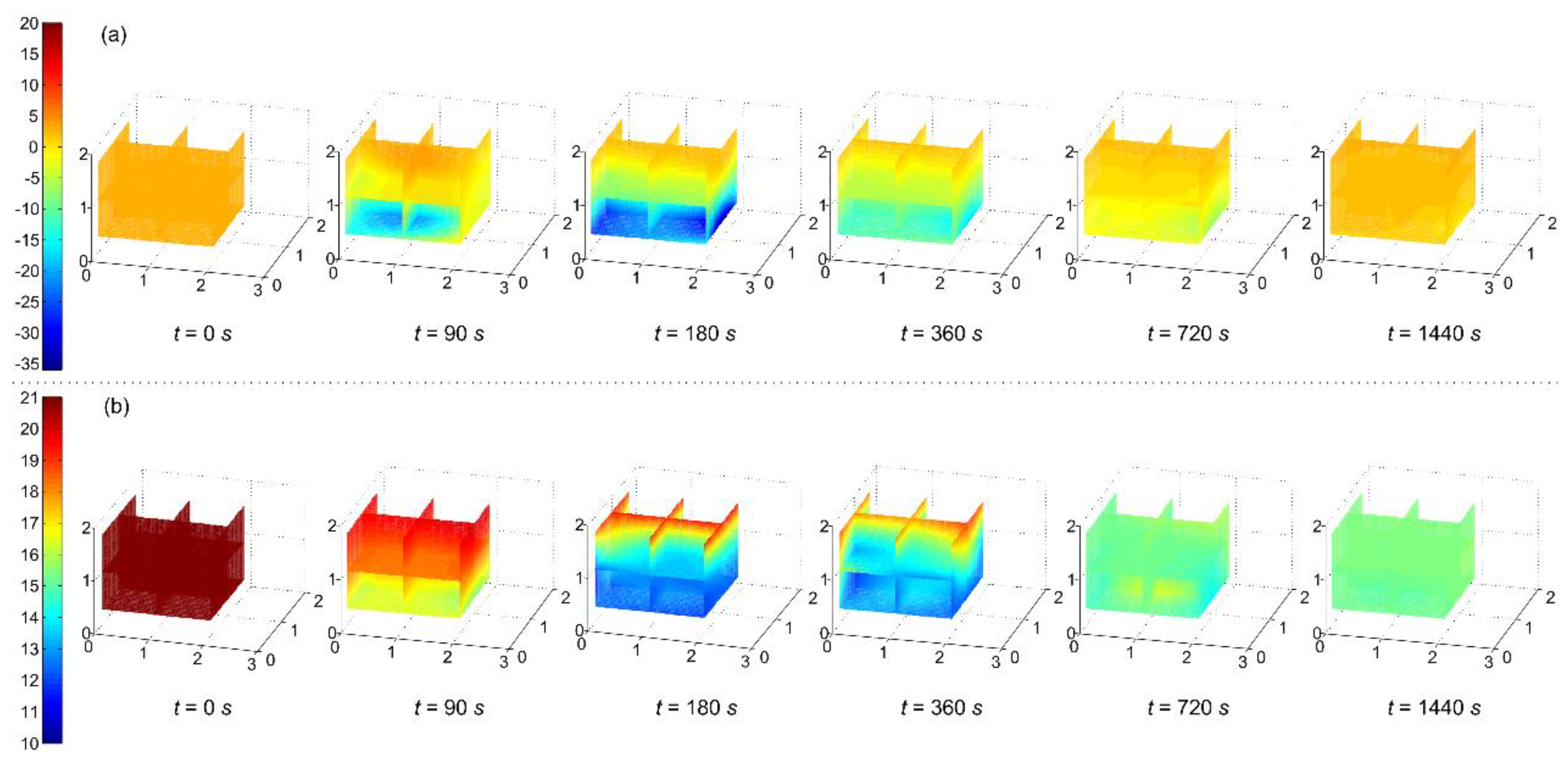

3.1. Temperatures and Oxygen Concentrations Versus Time

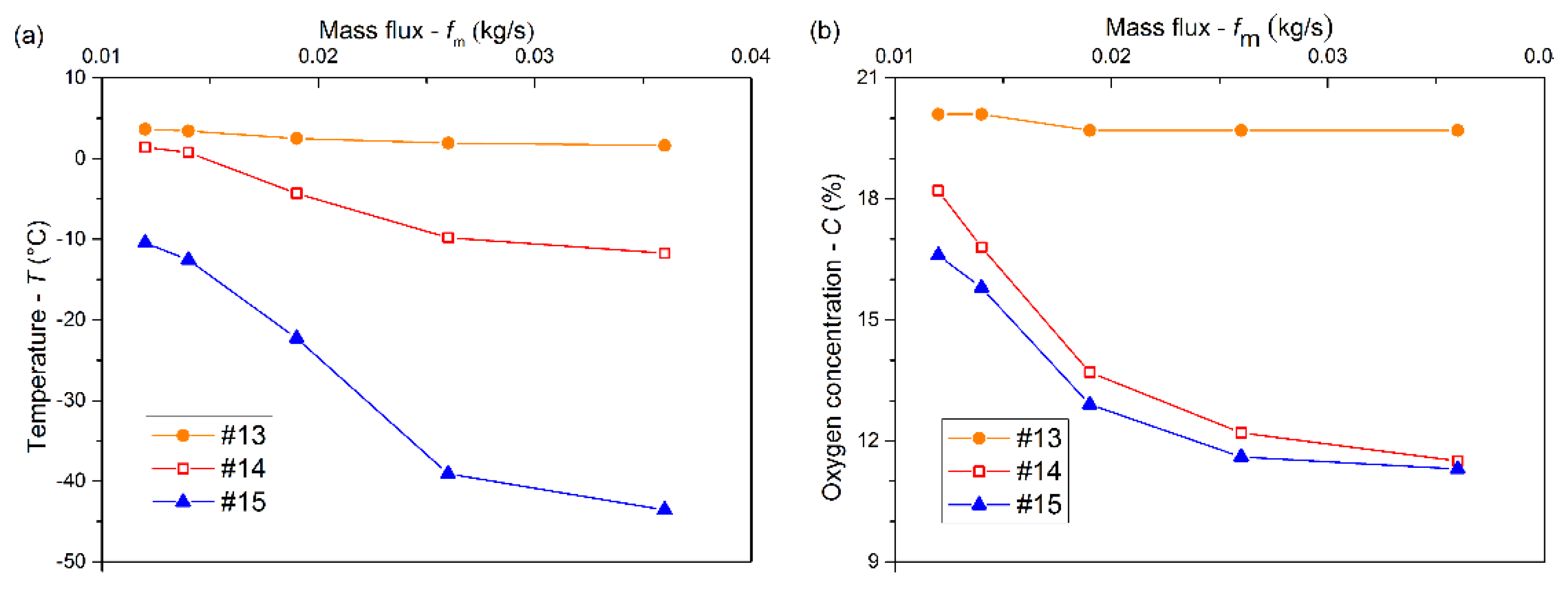

3.2. Effects of Mass Flux on the Cooling and Inerting Effects

3.3. Effects of Pipe Diameter on the Cooling and Inerting Effects

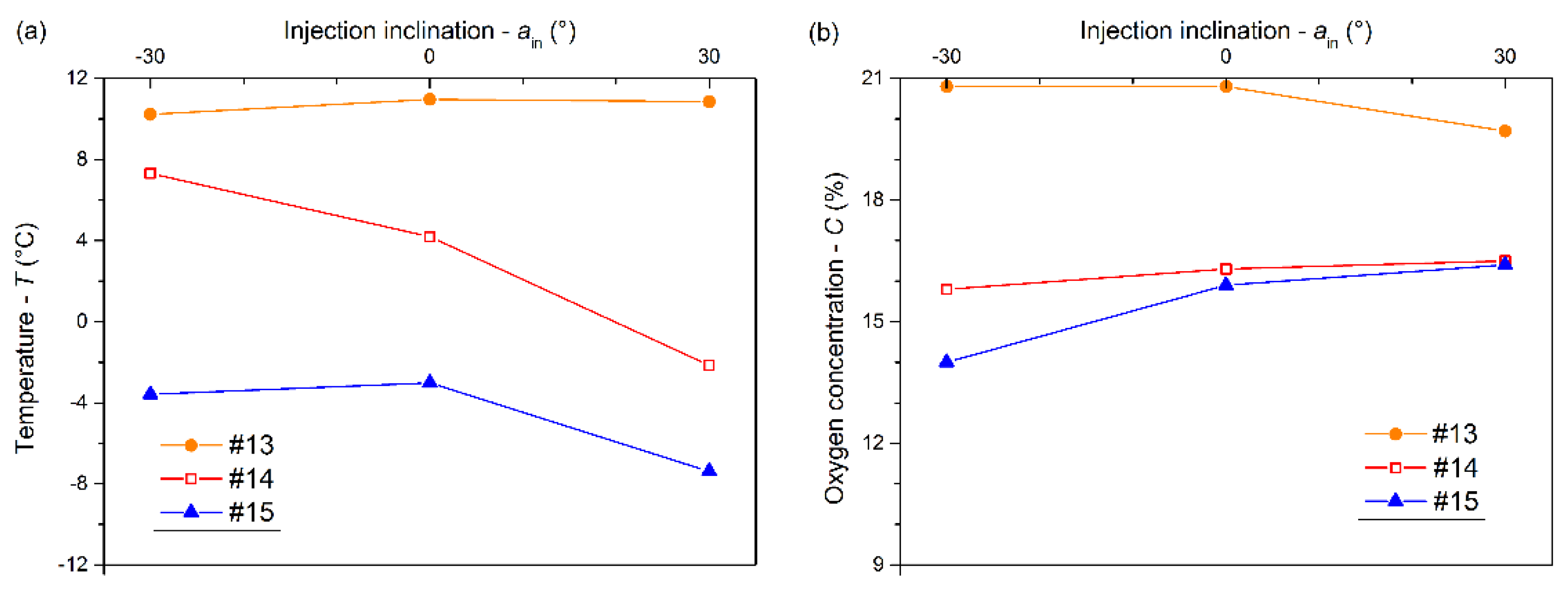

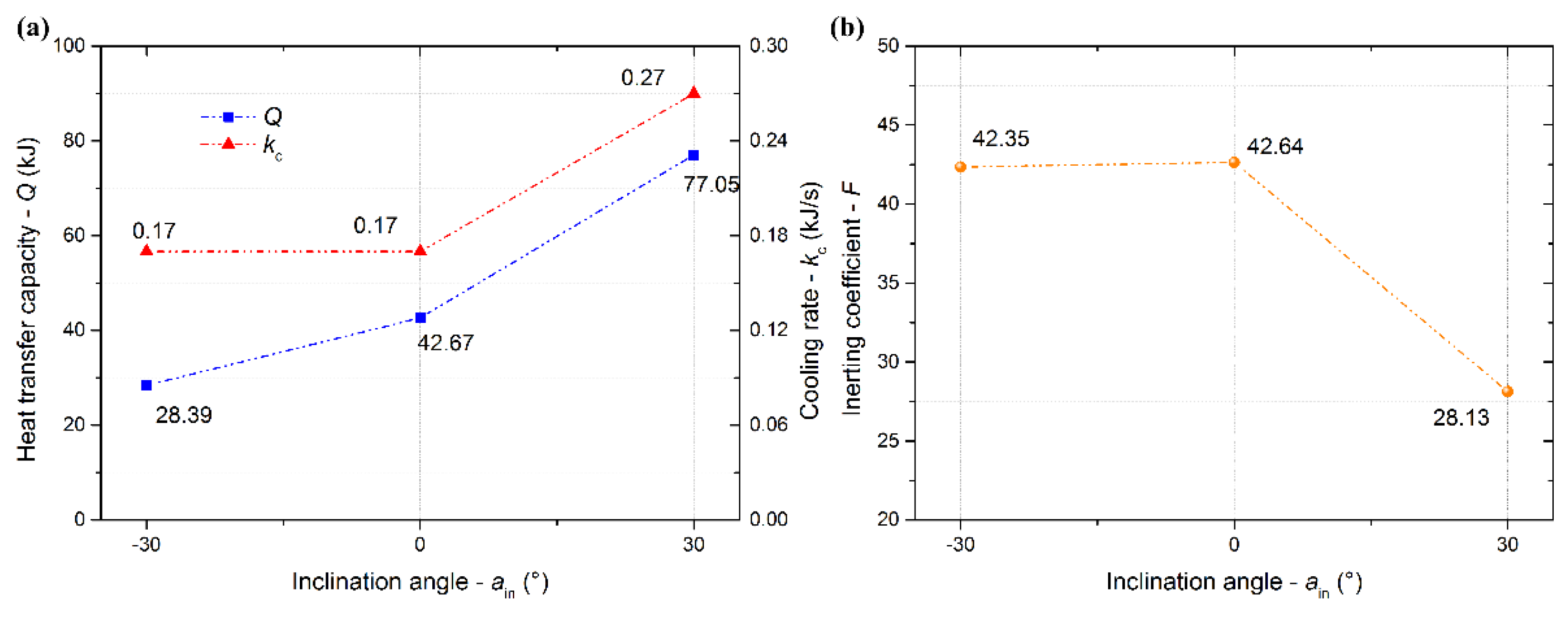

3.4. Effects of Injection Angle on the Cooling and Inerting Effects

4. Conclusions

- The low-temperature area mainly was located in the lower place owing to gravity. There was a linear relationship between the heat transfer capacity and time when LN2 reached a vaporization balance in the low-temperature resistance steel pipe. After LN2 injection, the cooling effect was only limited in the lower part of the confined space. However, there were no significant differences both among the temperatures and among the oxygen concentrations in the same horizontal plane.

- The low-temperature low-oxygen space gradually expanded upward with increasing mass flux. The increasing pipe diameter (>20 mm) went against the heat and mass transfer of LN2 in the confined space. Both the contact time and the contact area between LN2 and the air could increase with a positively increasing inclination angle, which strengthened the cooling and inerting.

- The inerting effect of LN2 was gradually enhanced with a mass flux increasing from 0.014 to 0.026 kg/s and then tended to level off. An appropriate pipe diameter should be selected to improve the cooling and inerting effects of LN2, the optimal one being 12 mm in this experiment. Otherwise, a positively increasing inclination angle could contribute to the cooling and inerting effects of LN2 injected into the confined space. However, there was little effect on the cooling and inerting when the inclination angle was below 0°.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gage, A.A.; Baust, J. Mechanisms of Tissue Injury in Cryosurgery. Cryobiology 1998, 37, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowlen, C.; Mattick, A.T.; Bruckner, A.P.; Hertzberg, A. High Efficiency Energy Conversion Systems for Liquid Nitrogen Automobiles. SAE Trans. 1998, 107, 1837–1842. [Google Scholar]

- Proux, O.; Nassif, V.; Prat, A.; Ulrich, O.; Lahera, E.; Biquard, X.; Menthonnex, J.J.; Hazemann, J.L. Feedback system of a liquid-nitrogen-cooled double-crystal monochromator: Design and performances. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2010, 13, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H. Femtosecond laser induced formation of nanostructures on silicon and silver surfaces in liquid nitrogen. Diss. Theses-Gradworks 2015. Available online: https://search.proquest.com/openview/16ae0ef5d4f7b71f02d4989dc63078b9/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 17 April 2019).

- Beidelman, J.A. Liquid Nitrogen Fire Extinguishing System Test Report; NASA Sti/recon Technical Report N; Argonne National Lab.: Lemont, IL, USA, 1972; Volume 77. [Google Scholar]

- Klueg, E.P. Liquid nitrogen as a powerplant fire extinguishant. Fire Technol. 1969, 5, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torikai, H.; Ishidoya, M.; Ito, A. Examination of Extinguishment Method with Liquid Nitrogen Packed in a Spherical Ice Capsule. Fire Technol. 2016, 52, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levendis, Y.; Ergut, A.; Delichatsios, M. Cryogenic extinguishment of liquid pool fires. Process Saf. Progr. 2010, 29, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Sunderland, P.B.; Lathrop, D.P. Suppression of sodium fires with liquid nitrogen. Fire Saf. J. 2013, 58, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levendis, Y.A.; Delichatsios, M.A. Pool fire extinction by remotely controlled application of liquid nitrogen. Process Saf. Prog. 2011, 30, 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcguire, J. Fighting building fires with liquid nitrogen: A literature survey. Fire Saf. J. 1981, 4, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Zhou, F. Fire extinguishment behaviors of liquid fuel using liquid nitrogen jet. Process Saf. Prog. 2016, 35, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. Experimental investigation of applying MgCl2 and phosphates to synergistically inhibit the spontaneous combustion of coal. J. Energy Inst. 2018, 91, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Wang, H. Experimental investigation on microstructure evolution and spontaneous combustion properties of secondary oxidation of lignite. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 124, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.G. Cryogenic injection to control a coal waste bank fire. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2004, 59, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohalik, N.K.; Singh, R.V.K.; Pandey, J.; Singh, V.K. Application of nitrogen as preventive and controlling subsurface fire—Indian context. J. Sci. Ind. Res. 2005, 64, 273–280. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, B.; Ma, L.; Dong, W.; Zhou, F. Application of a Novel Liquid Nitrogen Control Technique for Heat Stress and Fire Prevention in Underground Mines. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2015, 12, D168–D177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.B.; Shi, B.B.; Cheng, J.W.; Ma, L.J. A New Approach to Control a Serious Mine Fire with Using Liquid Nitrogen as Extinguishing Media. Fire Technol. 2015, 51, 325–334. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, B.; Zhou, F. Impact of heat and mass transfer during the transport of nitrogen in coal porous media on coal mine fires. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 4198–4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, R.Z.; Xu, L.X. Flow boiling of liquid nitrogen in micro-tubes: Part II -Heat transfer characteristics and critical heat flux. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2007, 50, 5017–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.C.; Brian, P.L.T.; Weber, M.E. Heat transfer and frost formation inside a liquid nitrogen-cooled tube. Aiche J. 1966, 12, 1190–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaeffer, R.; Hong, H.; Chung, J.N. An experimental study on liquid nitrogen pipe chilldown and heat transfer with pulse flows. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 67, 955–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.M.; Wen, J.; Li, Y.M.; Wang, S.H.; Li, Y.Z. Population balance modelling for subcooled boiling flow of liquid nitrogen in a vertical tube. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 60, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (1) | Fixed Parameters | Φ = 28 mm, ain = 0° | |||||

| Mass flux fm (kg/s) | 0.012 | 0.014 | 0.019 | 0.026 | 0.036 | ||

| (2) | Fixed Parameters | fm = 0.014 kg/s, ain = 0° | |||||

| Pipe diameter Φ (mm) | 4 | 12 | 20 | 28 | 32 | 40 | |

| (3) | Fixed Parameters | fm = 0.014 kg/s, Φ = 20 mm | |||||

| Inclination angle ain (°) | −30 | 0 | +30 | ||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ji, H.; Li, Y.; Su, H.; Cheng, W.; Wu, X. Experimental Investigation on the Cooling and Inerting Effects of Liquid Nitrogen Injected into a Confined Space. Symmetry 2019, 11, 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11040579

Ji H, Li Y, Su H, Cheng W, Wu X. Experimental Investigation on the Cooling and Inerting Effects of Liquid Nitrogen Injected into a Confined Space. Symmetry. 2019; 11(4):579. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11040579

Chicago/Turabian StyleJi, Huaijun, Yunzhuo Li, Hetao Su, Wuyi Cheng, and Xiang Wu. 2019. "Experimental Investigation on the Cooling and Inerting Effects of Liquid Nitrogen Injected into a Confined Space" Symmetry 11, no. 4: 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11040579

APA StyleJi, H., Li, Y., Su, H., Cheng, W., & Wu, X. (2019). Experimental Investigation on the Cooling and Inerting Effects of Liquid Nitrogen Injected into a Confined Space. Symmetry, 11(4), 579. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym11040579