Deforming Gibbs Factor Using Tsallis q-Exponential with a Complex Parameter: An Ideal Bose Gas Case

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Starting Points

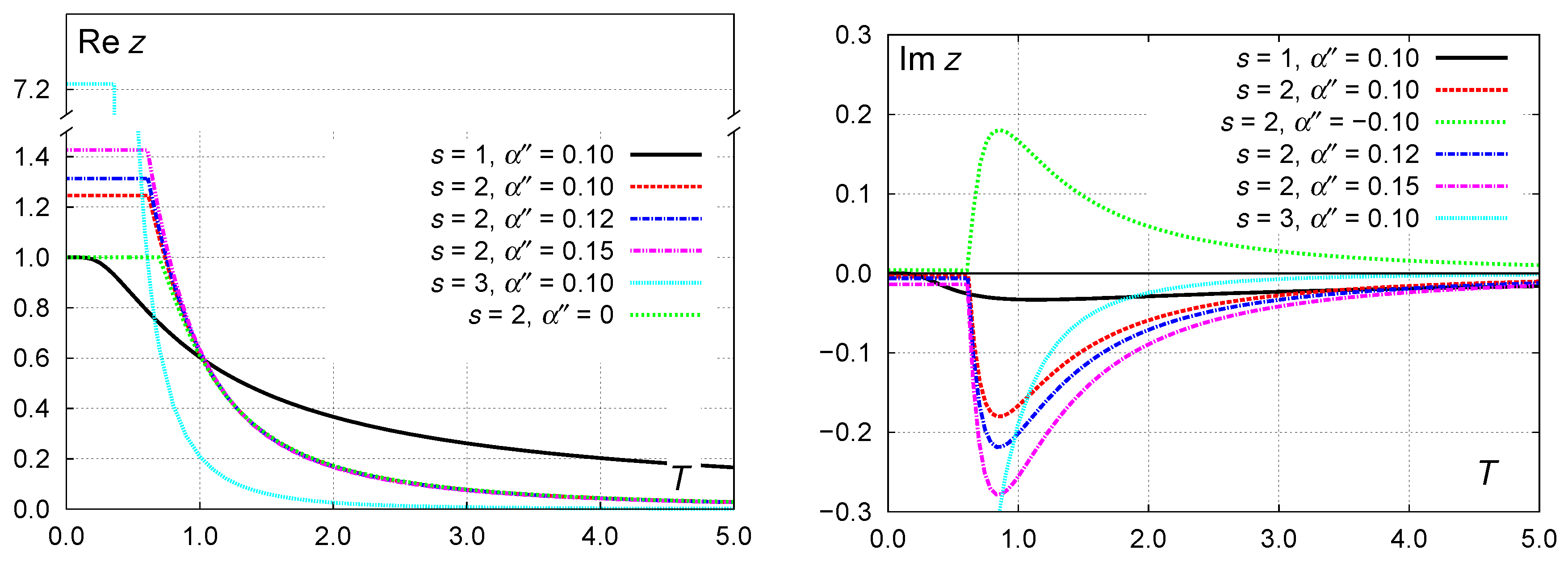

3. Calculations of Fugacity and Energy

4. Numerical Results and High-Temperature Behavior

5. Towards the Critical Point

6. The Limit of

7. Discussion

8. Materials and Methods

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bender, C.M.; Boettcher, S. Real spectra in non-Hermitian Hamiltonians having PT symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 80, 5243–5246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bender, C.M.; Dorey, P.E.; Dunning, C.; Fring, A.; Hook, D.W.; Jones, H.F.; Kuzhel, S.; Lévai, G.; Tateo, R. PT Symmetry In Quantum and Classical Physics; World Scientific: Singapore, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachuk, V.M.; Fityo, T.V. Factorization and superpotential of the PT symmetric Hamiltonian. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2001, 34, 8673–8677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, A.; Salamo, G.J.; Duchesne, D.; Morandotti, R.; Volatier-Ravat, M.; Aimez, V.; Siviloglou, G.A.; Christodoulides, D.N. Observation of PT-symmetry breaking in complex optical potentials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2009, 103, 093902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hayward, R.; Biancalana, F. Complex Berry phase dynamics in PT-symmetric coupled waveguides. Phys. Rev. A 2018, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- El-Ganainy, R.; Makris, K.G.; Khajavikhan, M.; Musslimani, Z.H.; Rotter, S.; Christodoulides, D.N. Non-Hermitian physics and PT symmetry. Nat. Phys. 2018, 14, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashida, Y.; Furukawa, S.; Ueda, M. Parity-time-symmetric quantum critical phenomena. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, D.J. Introduction to Electrodynamics, 3rd ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, G.S.; Hennig, H.; Fleischmann, R.; Kottos, T.; Geisel, T. Avalanches of Bose–Einstein condensates in leaking optical lattices. New J. Phys. 2009, 11, 073045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveev, V.; Shrock, R. Complex-temperature properties of the Ising model on 2D heteropolygonal lattices. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1995, 28, 5235–5256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chakraborty, P.K.; Nag, B.; Ghatak, K.P. On the electron energy spectrum in heavily doped non-parabolic semiconductors. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2003, 64, 2191–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, G.E.; Kerman, A.K. Complex Chemical Potential: Signature of Decay in a Bose-Einstein Condensate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 190402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ipsen, J.R.; Splittorff, K. Baryon number Dirac spectrum in QCD. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 86, 014508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bender, C.M.; Brody, D.C.; Hook, D.W. Quantum effects in classical systems having complex energy. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 2008, 41, 352003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kuzmak, A.R.; Tkachuk, V.M. Detecting the Lee-Yang zeros of a high-spin system by the evolution of probe spin. EPL (Europhys. Lett.) 2019, 125, 10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rényi, A. On measures of entropy and information. In Proceedings of the 4th Berkeley Symposium on Mathematics, Statistics and Probability 1960; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1961; pp. 547–561. [Google Scholar]

- Daróczy, Z. Generalized information functions. Inf. Control 1970, 16, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsallis, C. Possible generalization of Boltzmann-Gibbs statistics. J. Stat. Phys. 1988, 52, 479–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M.; Tsallis, C. (Eds.) Nonextensive Entropy: Interdisciplinary Applications; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, S.; Okamoto, Y. (Eds.) Nonextensive Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyükkılıç, F.; Demirhan, D.; Güleç, A. A statistical mechanical approach to generalized statistics of quantum and classical gases. Phys. Lett. A 1995, 197, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragão-Rêgo, H.H.; Soares, D.J.; Lucena, L.S.; da Silva, L.R.; Lenzi, E.K.; Fa, K.S. Bose–Einstein and Fermi–Dirac distributions in nonextensive Tsallis statistics: An exact study. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2003, 317, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.; Chen, J. Thermostatistic properties of a q-generalized Bose system trapped in an n-dimensional harmonic oscillator potential. Phys. Rev. E 2003, 68, 026123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh, H.; Adli, F.; Nouri, S. Perturbative thermodynamic geometry of nonextensive ideal classical, Bose, and Fermi gases. Phys. Rev. E 2016, 94, 062118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rovenchak, A. Ideal Bose-gas in nonadditive statistics. Low Temp. Phys. 2018, 44, 1025–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adli, F.; Mohammadzadeh, H.; Najafi, M.N.; Ebadi, Z. Condensation of nonextensive ideal Bose gas and critical exponents. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2019, 521, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanatar, B. Trapped interacting Bose gas in nonextensive statistical mechanics. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 65, 046105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsallis, C. What are the numbers that experiments provide? Química Nova 1994, 17, 468–471. [Google Scholar]

- Gliozzi, F.; Tagliacozzo, L. Entanglement entropy and the complex plane of replicas. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2010, 2010, P01002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plastino, A.; Rocca, M.C. A direct proof of Jauregui-Tsallis’ conjecture. J. Math. Phys. 2011, 52, 103503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Plastino, A.; Rocca, M.C. Inversion of Umarov–Tsallis–Steinberg’s q-Fourier transform and the complex-plane generalization. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2012, 391, 4740–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilk, G.; Włodarczyk, Z. Tsallis distribution with complex nonextensivity parameter q. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2014, 413, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Matsuzoe, H.; Wada, T. Deformed algebras and generalizations of independence on deformed exponential families. Entropy 2015, 17, 5729–5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilk, G.; Włodarczyk, Z. Tsallis distribution decorated with log-periodic oscillation. Entropy 2015, 17, 384–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rotundo, G.; Ausloos, M. Complex-valued information entropy measure for networks with directed links (digraphs). Application to citations by community agents with opposite opinions. Eur. Phys. J. B 2013, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, R.; Darus, M. Analytic study of complex fractional Tsallis’ entropy with applications in CNNs. Entropy 2018, 20, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abreu, E.M.C.; Moura, N.J.; Soares, A.D.; Ribeiro, M.B. Oscillations in the Tsallis income distribution. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2019, 533, 121967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isihara, A. Statistical Physics; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Khare, A. Fractional Statistics and Quantum Theory, 2nd ed.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Xie, S.; Feng, W.; Wu, X. Statistics for q-commutator in the case of qs+1 = 1. Mod. Phys. Lett. A 1998, 13, 879–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrilik, A.M.; Rebesh, A.P. Deformed gas of p, q-bosons: Virial expansion and virial coefficients. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2012, 25, 1150030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rovenchak, A. Phase transition in a system of 1D harmonic oscillators obeying Polychronakos statistics with a complex parameter. Low Temp. Phys. 2013, 39, 888–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rovenchak, A. Complex-valued fractional statistics for D-dimensional harmonic oscillators. Phys. Lett. A 2014, 378, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovenchak, A.; Sobko, B. Fugacity versus chemical potential in nonadditive generalizations of the ideal Fermi-gas. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2019, 534, 122098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salasnich, L. BEC in nonextensive statistical mechanics. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2000, 14, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. Statisticsl Physics. Part 1, 3rd ed.; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ashida, Y.; Furukawa, S.; Ueda, M. Quantum critical behavior influenced by measurement backaction in ultracold gases. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 053615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- The Mathematical Functions Site, 1998–2020. Available online: http://functions.wolfram.com (accessed on 20 March 2020).

| s, | at | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| , | 0 | 1 | |

| , | 0.690 | 1 | 2.857 |

| , | 0.616 | ||

| , | 0.612 | ||

| , | 0.609 | ||

| , | 0.359 |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rovenchak, A. Deforming Gibbs Factor Using Tsallis q-Exponential with a Complex Parameter: An Ideal Bose Gas Case. Symmetry 2020, 12, 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12050732

Rovenchak A. Deforming Gibbs Factor Using Tsallis q-Exponential with a Complex Parameter: An Ideal Bose Gas Case. Symmetry. 2020; 12(5):732. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12050732

Chicago/Turabian StyleRovenchak, Andrij. 2020. "Deforming Gibbs Factor Using Tsallis q-Exponential with a Complex Parameter: An Ideal Bose Gas Case" Symmetry 12, no. 5: 732. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym12050732