The Generalized OTOC from Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics—Study of Random Fluctuations from Eigenstate Representation of Correlation Functions

Abstract

:| Contents | ||

| 1 | Introduction | 3 |

| 2 | Lexicography | 12 |

| 3 | A Short Review of Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics | 12 |

| 4 | General Remarks on Time Disorder Averaging and Thermal OTOCs | 14 |

| 5 | Eigenstate Representation of thermal OTOCs in Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics | 20 |

| 5.1 Partition Function from Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics.................................................................................................................... | 23 | |

| 5.2 Representation of 2-Point OTOC: ................................................................................................................................ | 24 | |

| 5.3 Representation of 2-Point OTOC: ................................................................................................................................ | 25 | |

| 5.4 Representation of 2-Point OTOC: ................................................................................................................................ | 25 | |

| 5.5 Representation of 4-Point OTOC: ................................................................................................................................ | 26 | |

| 5.5.1 Un-Normalized: .................................................................................................................................... | 26 | |

| 5.5.2 Normalized: ..................................................................................................................................... | 27 | |

| 5.6 Representation of 4-Point OTOC: ................................................................................................................................ | 28 | |

| 5.6.1 Un-Normalized: ................................................................................................................................... | 28 | |

| 5.6.2 Normalized: .................................................................................................................................... | 29 | |

| 5.7 Representation of 4-Point OTOC: ................................................................................................................................. | 30 | |

| 5.7.1 Un-Normalized: .................................................................................................................................... | 30 | |

| 5.7.2 Normalized: .................................................................................................................................... | 31 | |

| 5.8 Summary of Results ......................................................................................................................................................... | 32 | |

| 6 | Model I: Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanical Harmonic Oscillator | 33 |

| 6.1 Eigenspectrum of the Super-Partner Hamiltonian............................................................................................................................. | 33 | |

| 6.2 Partition Function.......................................................................................................................................................... | 34 | |

| 6.3 Computation of 2-Point OTOCs................................................................................................................................................ | 35 | |

| 6.3.1 Computation of ................................................................................................................................... | 35 | |

| 6.3.2 Computation of .................................................................................................................................... | 37 | |

| 6.3.3 Computation of .................................................................................................................................... | 38 | |

| 6.4 Computation of Un-Normalized 4-Point OTOCs.................................................................................................................................. | 40 | |

| 6.4.1 Computation of ................................................................................................................................... | 40 | |

| 6.4.2 Computation of .................................................................................................................................... | 42 | |

| 6.4.3 Computation of .................................................................................................................................... | 44 | |

| 6.5 Computation of Normalized 4-Point OTOCs..................................................................................................................................... | 46 | |

| 6.5.1 Computation of .................................................................................................................................. | 46 | |

| 6.5.2 Computation of .................................................................................................................................. | 48 | |

| 6.5.3 Computation of .................................................................................................................................. | 49 | |

| 6.6 Summary of Results ......................................................................................................................................................... | 50 | |

| 7 | Model II: Supersymmetric One-Dimensional Potential Well | 52 |

| 8 | General Remarks on the Classical Limiting Interpretation of OTOCs | 54 |

| 9 | Classical Limit of OTOC for Supersymmetric One-Dimensional Harmonic Oscillator | 55 |

| 10 | Classical Limit of OTOC for Supersymmetric 1D Box | 57 |

| 11 | Numerical Results | 60 |

| 11.1 Supersymmetric 1D Infinite Potential Well................................................................................................................................... | 61 | |

| 11.2 Supersymmetric 1D Harmonic Oscillator....................................................................................................................................... | 72 | |

| 12 | Conclusions | 83 |

| Appendix A | Derivation of the Normalization Factors for the Supersymmetric HO | 86 |

| Appendix B | Poisson Bracket Relation for the Supersymmetric Partner Potential Associated with the 1D Infinite Well Potential | 88 |

| Appendix C | Derivation of the Eigenstate Representation of the Correlators | 91 |

| Appendix C.1 Representation of 2-point Correlator: .................................................................................................................. | 91 | |

| Appendix C.2 Representation of 2-point Correlator: .................................................................................................................. | 92 | |

| Appendix C.3 Representation of 2-point Correlator: .................................................................................................................. | 93 | |

| Appendix C.4 Representation of 4-Point Correlator: .................................................................................................................. | 93 | |

| Appendix C.4.1 Un-normalized: ....................................................................................................................................... | 93 | |

| Appendix C.4.2 Un-normalized: ....................................................................................................................................... | 95 | |

| Appendix C.5 Representation of 4-point Correlator: .................................................................................................................. | 98 | |

| Appendix C.6 Eigenstate Representation of the Normalization Factors for the 4-point Correlators...................... | 100 | |

| References | 100 | |

1. Introduction

- Formalism I:The first approach is based on the construction and the mathematical from of the solution of the Fokker Planck equation, using which various stochastic phenomena in the quantum out-of-equilibrium regime can be studied. One of the famous examples is the stochastic cosmological particle production phenomena, which can be directly mapped to a problem of solving Schrdinger equation with an impurity potential within the framework of quantum mechanics, which is actually describing propagation of electrons inside an electrical wire in presence of an impurity or defect. Within the framework of quantum statistical mechanics, instead of solving the Schrdinger problem directly, or maybe solving the dynamical equation for the quantum mechanical fluctuations during the stochastic particle production, one can think about a cumulative probability distribution function of this stochastic process, , which depends on two crucial quantities, which are: the number density of the produced particle and the associated time scale of the stochastic process. Using detailed physical arguments and computation, one can explicitly show that this probability distribution function, , satisfies the Fokker Planck equation, which is given by:where represents the mean stochastic particle production rate and associated potential, which is only significant at finite temperature. By solving this set of equations in the presence of appropriate initial conditions, one can get to know about the related profile of the stochastic process semi-classically in the present context. And not only that, but one can also treat these versions of the Fokker Planck equation as the semi-classical statistical moment generating equations because, by replacing the profile function with the appropriate moment generating function , one can compute all the moments. To serve this purpose, one needs to use the following fundamental equation:which physically represents the expectation value or the statistical average value of the number density-dependent moment generating any arbitrary function . Further substituting the appropriate form of this function in the moment dependent Fokker Planck equations, one can explicitly compute the expression for all the physically relevant statistical moments, i.e., , , ⋯ explicitly without explicitly knowing about the particular mathematical structure of the profile of the related stochastic dynamical process at infinite or finite temperature for a given structure of number density potential function. These moments are extremely important in the present context of study as all of them semi-classically compute the expressions for all the equal time quantum correlation functions required to study the out-of-equilibrium aspects, such as stochastic effects, disorder, random fluctuations [91], etc., both at infinite and finite temperatures. See References [2,92,93,94,95,96], where all authors have studied the physical impact of this formalism to describe out-of-equilibrium aspects in various different contexts.Now, let us speak about some applicability issues related to this particular formalism. Since this formalism only allows us to know about the effect of the semi-classical correlations at equal time that might be not very interesting when we are actually thinking of doing the computation of the correlations and its rate of change at different time scales associated with the quantum mechanical system of study. For example, if we are interested in computing any general N-point semi-classical correlation function as defined by the following expression:then this particular formalism will not work, as using this formalism one cannot capture the effect of disorder effect in the associated time scale of the system. On the other hand, by following the usual tools and techniques, one can only compute the aforementioned N-point correlators either in time ordered sense, where or in the anti-time ordered sense, where . So, from the technical ground defining this N-point correlator, including the effect of disorder in the time scale at any arbitrary temperature is also a very important topic of research, and here comes the crucial role of the next formalism where we are allowed to define and explicitly compute such quantum effects at the level of correlation functions. Another important aspect we want to point out here is that the present formalism does not bother with any Lagrangian or the Hamiltonian formulation of the associated quantum mechanical system under consideration. So, if we are really interested to know about the effect of time disordering in the expressions for the quantum mechanical correlation functions, which are defined in terms of the fundamental operators appearing in the quantum version of the Lagrangian or the Hamiltonian of the system under consideration, and also want to explicitly know about time variation with respect to different time scales associated with the system, which are actually the source of time disordering, then, instead of the present formalism, it is obviously technically correct and easier to think about the implementation of the second formalism, which gives us the better understanding of time scale disordering. In the next point, and in the rest of the paper, we will follow the second formalism to compute the quantum correlation functions from the fundamental operators from the quantum mechanical systems under study, which can explicitly capture the effect of disordering in the time scale. Not only us, but also the present trend in the research, suggests to make use of the next formalism to get better understanding of time disordering phenomena in quantum mechanical system.

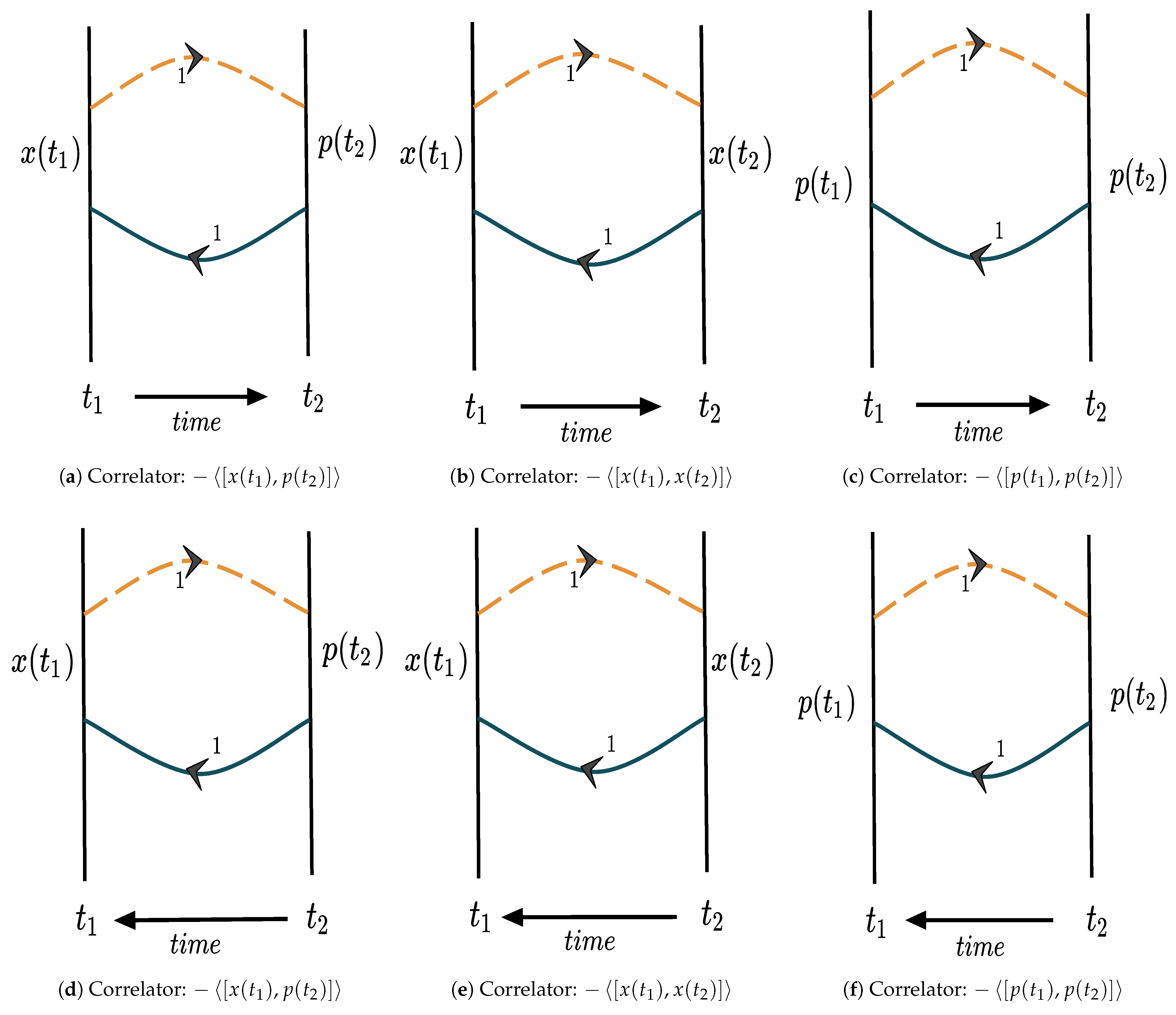

- Formalism II:The second approach is based on finding quantum correlation functions, including the time disordering effect, and, throughout the paper, we have followed this formalism to study effects of out-of-equilibrium physics in physical systems [89]. The present computational methodology helps us to know more about the underlying unexplored physical facts regarding the quantum mechanical aspects of various stochastic random process where time ordering or anti-time ordering is not at all important, and, instead of that, disorder in the time scale can be captured in the quantum correlations at very early time scale. This method not only helps us to know about the early time behavior of quantum correlations in the out-of-equilibrium regime of the quantum statistical mechanics but also gives crucial information regarding the late time equilibrium behavior of the quantum correlations of a specific quantum system. However, for all the systems in nature, the above interpretation of the quantum mechanical aspects of the randomness phenomena are not same. Based on all these types of quantum systems, one can categorize the random time disordering phenomena as: A.) a chaotic system which shows exponential growth in the quantum correlators, and B.) a non-chaotic system which shows periodic or aperiodic or irregular random fluctuations in the quantum correlators. The best possible theoretical measure of all such time disorder averaging phenomena for various statistical ensembles, micro-canonical and canonical ensembles, is described by out-of-time-ordered correlation (OTOC) function within the framework of quantum statistical mechanics. Let us define a set of operators, with or possibilities. The time disorder thermal average over statistical ensemble is described by the following expression: -4.6cm0cmwhere the thermal density matrix is defined as:In the present context, represents three possible types of OTOC, out of which only possibility, which will describe only one OTOC, has been explored in earlier works in this area. The other two OTOCs appearing from the possibility will be explicitly studied in this paper. The prime objective is to incorporate two more type of OTOCs, along with the well known other OTOC, to study all of the possible signatures of time disordering average from a quantum mechanical system. Our expectation is all these three types of OTOCs are able to describe the more general structure of stochastic randomness or any simple type of random process in the quantum regime. This idea was revived by Kitaev, then followed by Maldacena, Shenker, and Stanford (MSS) and many more in studying the quantum mechanical signature of chaos, which is actually the case in the above definition; but, the mathematical structure of the other two OTOCs represented by the case suggests that any non-chaotic behavior, such as periodic or aperiodic time-dependent behavior, any time-dependent growth in the correlators which is different from any type of exponential growth, and any type of decaying behavior in the correlators, can be explained in a better way compared to just studying the time-dependent behavior from the well known OTOCs which are commonly used in the literature. So, in short, to give a complete picture of any kind of time disordering phenomena, it is better to study all these possible three types of OTOCs to finally comment on the properties of any physical systems in quantum mechanical regime. A few other important things we want to point out here for better understanding the structure of all these OTOCs capturing the underlying physics of disordering averaging phenomena: First of all, here, we have to mention that, in using the definition that we have provided in this paper, we are able to compute three sets of point OTOCs. Though, in the further computation, we have restricted our study in the paper by considering and cases, to study the general time disorder averaging process, one may study any even multipoint (i.e., point) correlation functions from the present definition. Now, here, the case is basically representing a non-zero UTCR and can be treated as the building block of the full computation, as this particular case is mimicking the computation of the Green’s function in presence of time disordering. More technically, one can interpret that this contribution is made up of two disconnected time disorder averaged thermal correlator. These disconnected contributions are extremely significant if we wait for a large time scale; in literature, we usually identify this time scale as a dissipation time scale on which one can explicitly factorize any higher point correlators in terms of the non-vanishing disconnected contributions. For this specific reason, one can treat the case result as the building block of any higher point thermal correlators. However, for most of the quantum systems, the case shows random but decaying behavior with respect to the associated time scales which are explicitly appearing in the quantum operators of the theory. For this reason, study of any plays a significant role to give a better understanding of the time disordering phenomena. For this purpose, next, we studied the case, which represents the 4-point thermal correlator in the present context of study, and one of the most significant quantity in the present day research of this area, which can capture better information regarding the time disorder averaging compared to the case. In a future version of this work, we have a plan to extend the present computation to study the physical implications of quantum correlators to better understand the time disorder averaging phenomena. Now, we will comment on the technical side of the present formalism, using which one can explicitly compute these OTOCs in the present context. First of all, we talk about the time-independent Hamiltonians of a quantum system, which have their own eigenstates with a specific energy eigenvalue spectrum. In this case, construction of the OTOCs describing the time disorder thermal averaging over a canonical ensemble is described by two crucial components, the Boltzmann factor on which the general eigenstate dependent spectrum appears and also the temperature independent micro-canonical part of the OTOCs. At the end, we need to take the sum over all possible eigenstates, which will finally give a simplified closed expressions for OTOCs in the present context. Due to the appearance of the eigenstates from the time-independent Hamiltonian, this particular procedure will reduce the job extremely to study the time-dependent behavior of all the previously mentioned OTOCs that we have defined earlier in this paper. In the rest of the paper, we followed this prescription, which is only valid for time-independent Hamiltonian which have their own well-defined eigenstates. For more details, see the rest of the computations and related discussion that we studied in this paper. Most importantly, using this formalism, we can compute all of these OTOCs in a very simple model-independent way. The other technique is more complicated than the previously discussed one. In this case, one starts with a time-dependent Hamiltonian of the theory and uses the well-known Schwinger Keldysh formalism, which is a general path integral framework at finite temperature, for the study of the time evolution of a quantum mechanical system, which is in the out-of-equilibrium state. At the early time scale, once a small perturbation or a response is provided to a quantum system, then it is described by a out-of-equilibrium process within the framework of quantum statistical mechanics, and the present formalism provides us the sufficient tools and techniques, using which one can compute the expressions for the OTOCs. Not only that, the late time behavior of such an OTOC is described by a saturation behavior for chaotic systems, from which one can compute the various characteristic features of large time equilibrium behavior from these OTOCs.

- Formalism III:The third approach is based on the circuit quantum complexity [97,98,99,100,101,102,103], which is relatively a very new concept and physically defined as the minimum number of unitary operators, commonly known as quantum gates, that are specifically required to construct the desired target quantum state from a suitable reference quantum mechanical state. In a more generalized physical prescription, quantum mechanical complexity can serve as one of several strong diagnostics for probing the time disorder averaging phenomena of a quantum mechanical system or quantum randomness. The underlying physical concept of circuit complexity can essentially provide essential information regarding various aspects of quantum mechanical randomness, such as the concept of scrambling time, Lyapunov exponent, (The associated time scale when the quantum circuit complexity starts to grow is usually identified to be the scrambling time scale and, in the representative plot with respect to the time scale, particularly, the magnitude of the slope of the linear portion of the curve is physically interpreted as the Lyapunov exponent for the specific systems where the general quantum randomness or the time disorder averaging phenomena is described by quantum chaos.), etc., which are particularly the key features of the study of quantum mechanical chaos. One can further compare between the physical outcomes of the two strongest measures of quantum randomness, which are appearing from out-of-time-order correlators (OTOCs) and the quantum mechanical circuit complexity, and comment further that, for a specific quantum system which one is capturing, there is more information regarding the description of quantum mechanical randomness.

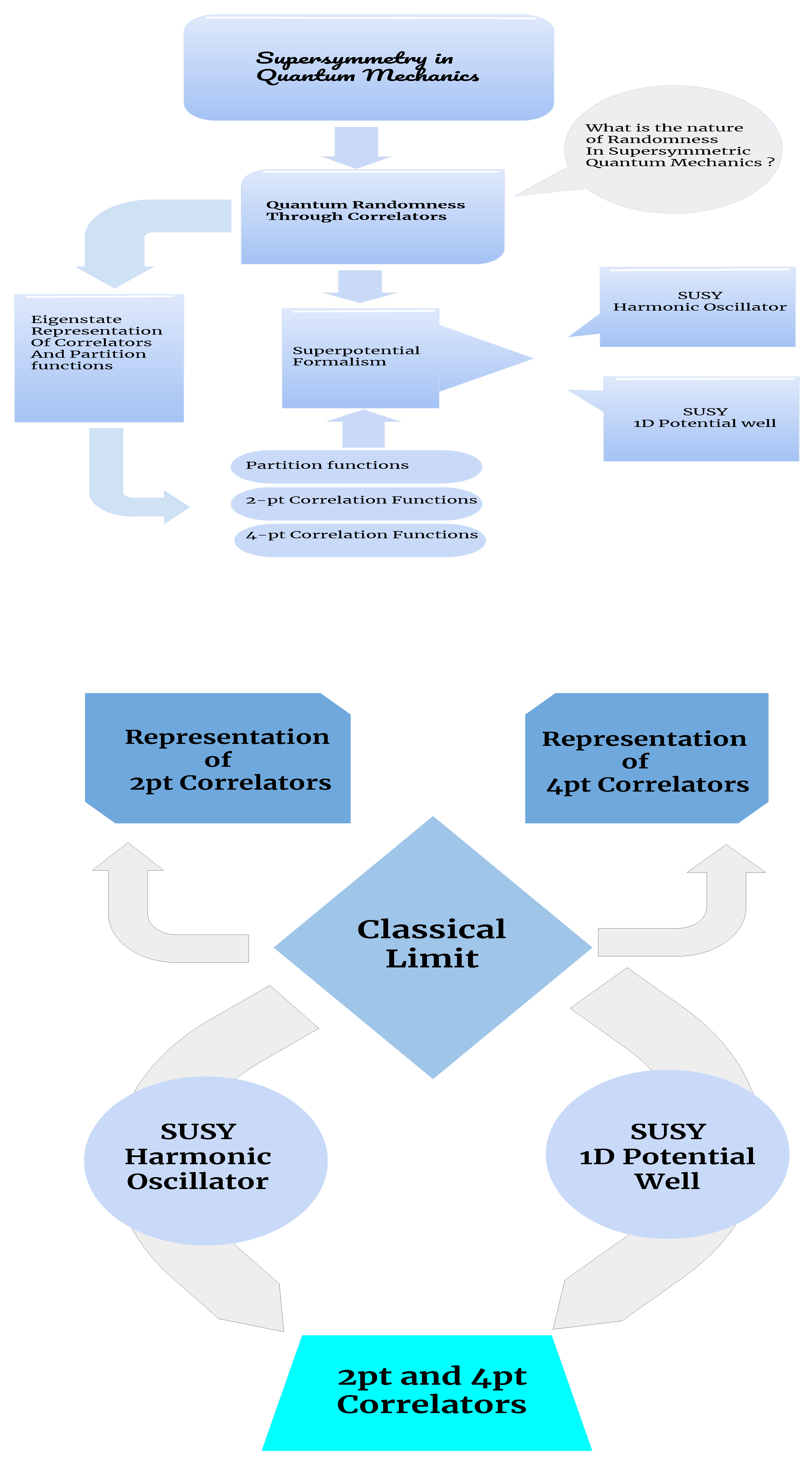

- In Section 3, we provide a brief review of the concept of Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics (QM).

- In Section 4, we explain how the phenomenon of Quantum Randomness can be diagnosed through the out of time ordered correlators.

- In Section 5, we provide a model-independent eigenstate representation of the 2- and the 4-point correlators of all the three kinds defined equally well for any QM model with well defined eigenstates.

- In Section 6, we explicitly calculate the correlators for the Supersymmetric Harmonic Oscillator.

- In Section 7, we provide the numerical calculations of the correlators for the Supersymmetric 1D infinite potnetial well.

- In Section 8, we discuss the semiclassical analogue results for the two Supersymmetric QM models.

- Finally, we conclude with the most important observations from our analysis of the considered Supersymmetric QM models.

2. Lexicography

3. A Short Review of Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics

4. General Remarks on Time Disorder Averaging and Thermal OTOCs

- 2-point OTOCs: , , ,

- 4-point OTOCs: , , ,

5. Eigenstate Representation of thermal OTOCs in Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics

- First, one can merely consider it as a tool to solve non-trivial potentials by means of solutions of their partner ones, provided that the partner ones are easily solvable.

- Secondly, one can consider it as a more unifying description of a more beautiful theory based on the principles of symmetries of nature. It is this second philosophy which has been considered in this work.

5.1. Partition Function from Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics

5.2. Representation of 2-Point OTOC:

5.3. Representation of 2-Point OTOC:

5.4. Representation of 2-Point OTOC:

5.5. Representation of 4-Point OTOC:

5.5.1. Un-Normalized:

5.5.2. Normalized:

5.6. Representation of 4-Point OTOC:

5.6.1. Un-Normalized:

5.6.2. Normalized:

5.7. Representation of 4-Point OTOC:

5.7.1. Un-Normalized:

5.7.2. Normalized:

5.8. Summary of Results

6. Model I: Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanical Harmonic Oscillator

6.1. Eigenspectrum of the Super-Partner Hamiltonian

6.2. Partition Function

6.3. Computation of 2-Point OTOCs

6.3.1. Computation of

6.3.2. Computation of

6.3.3. Computation of

6.4. Computation of Un-Normalized 4-Point OTOCs

6.4.1. Computation of

6.4.2. Computation of

6.4.3. Computation of

6.5. Computation of Normalized 4-Point OTOCs

6.5.1. Computation of

6.5.2. Computation of

6.5.3. Computation of

6.6. Summary of Results

7. Model II: Supersymmetric One-Dimensional Potential Well

8. General Remarks on the Classical Limiting Interpretation of OTOCs

9. Classical Limit of OTOC for Supersymmetric One-Dimensional Harmonic Oscillator

10. Classical Limit of OTOC for Supersymmetric 1D Box

11. Numerical Results

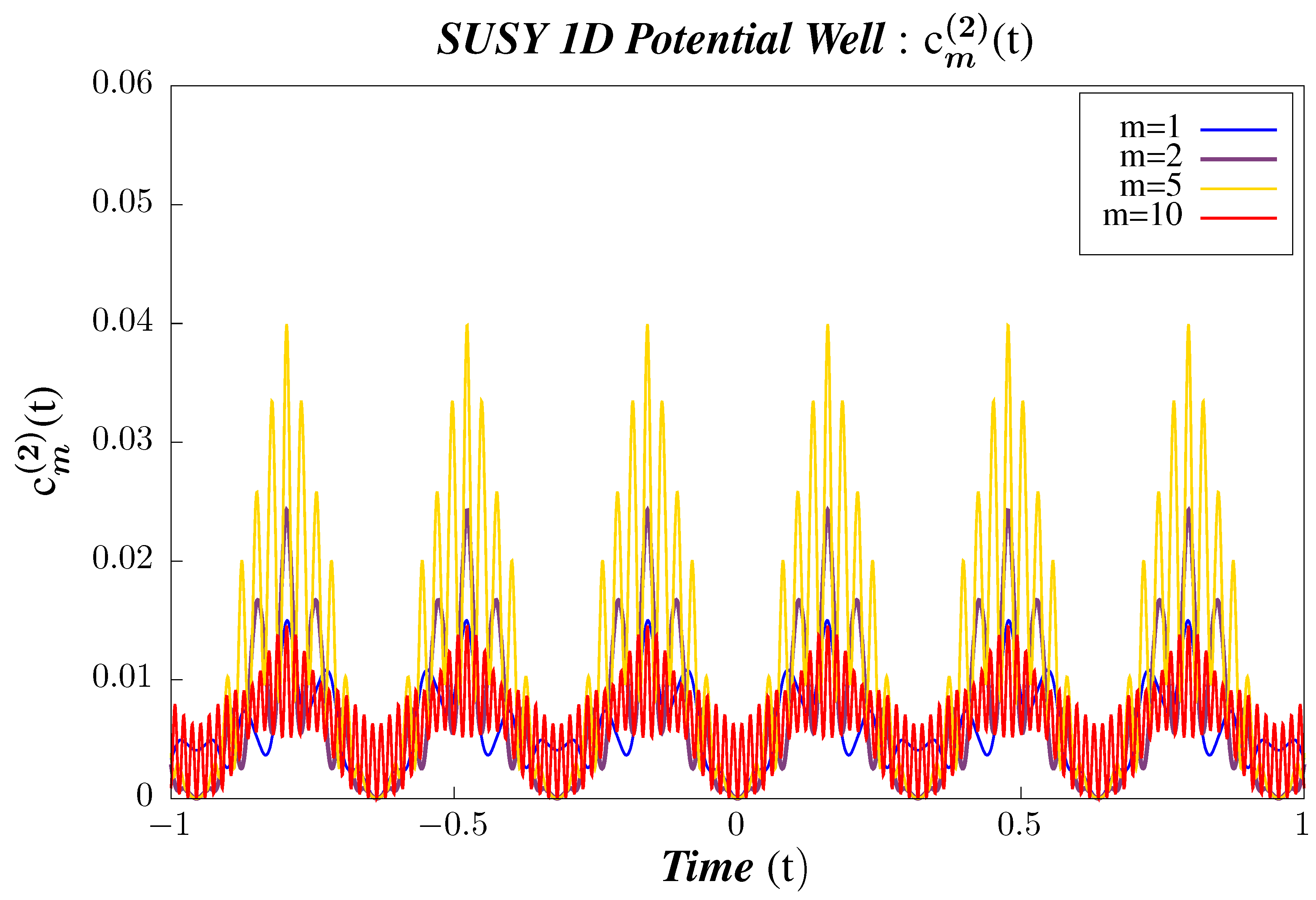

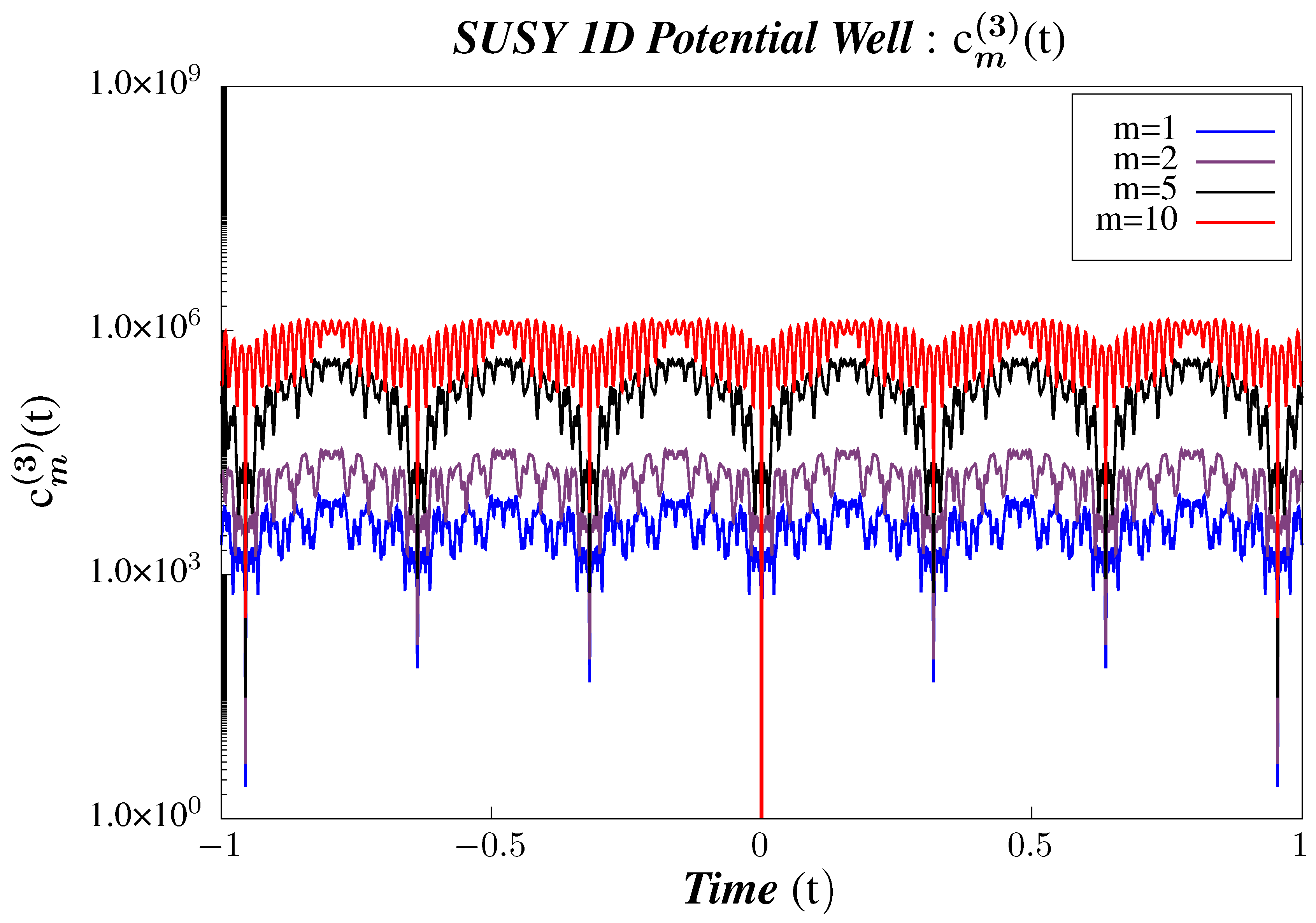

- Study A:The time dependence of 2-point and 4-point micro-canonical correlators for four different states: . This demonstrates the comparative behavior of micro-canonical correlators for different states under time evolution.

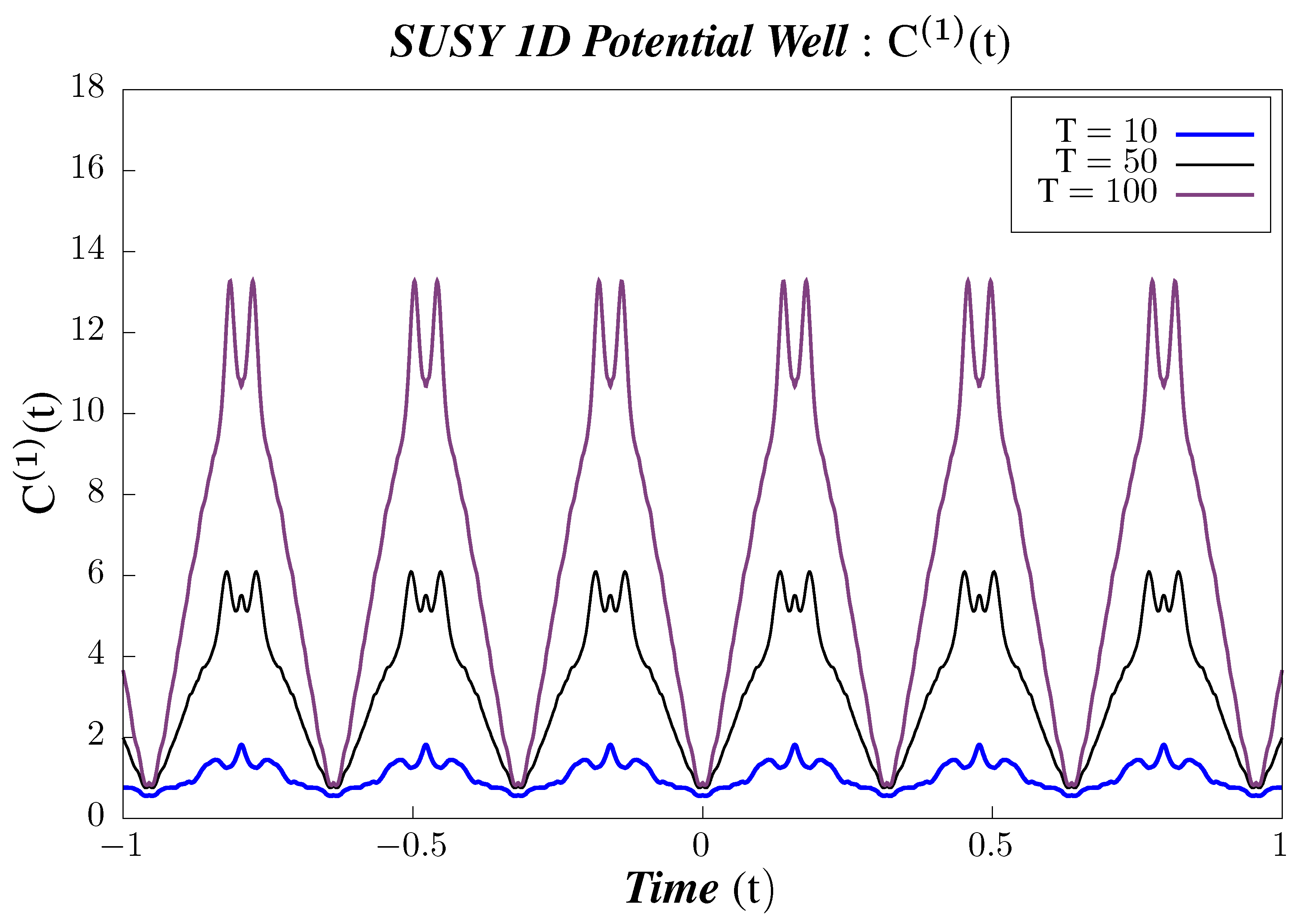

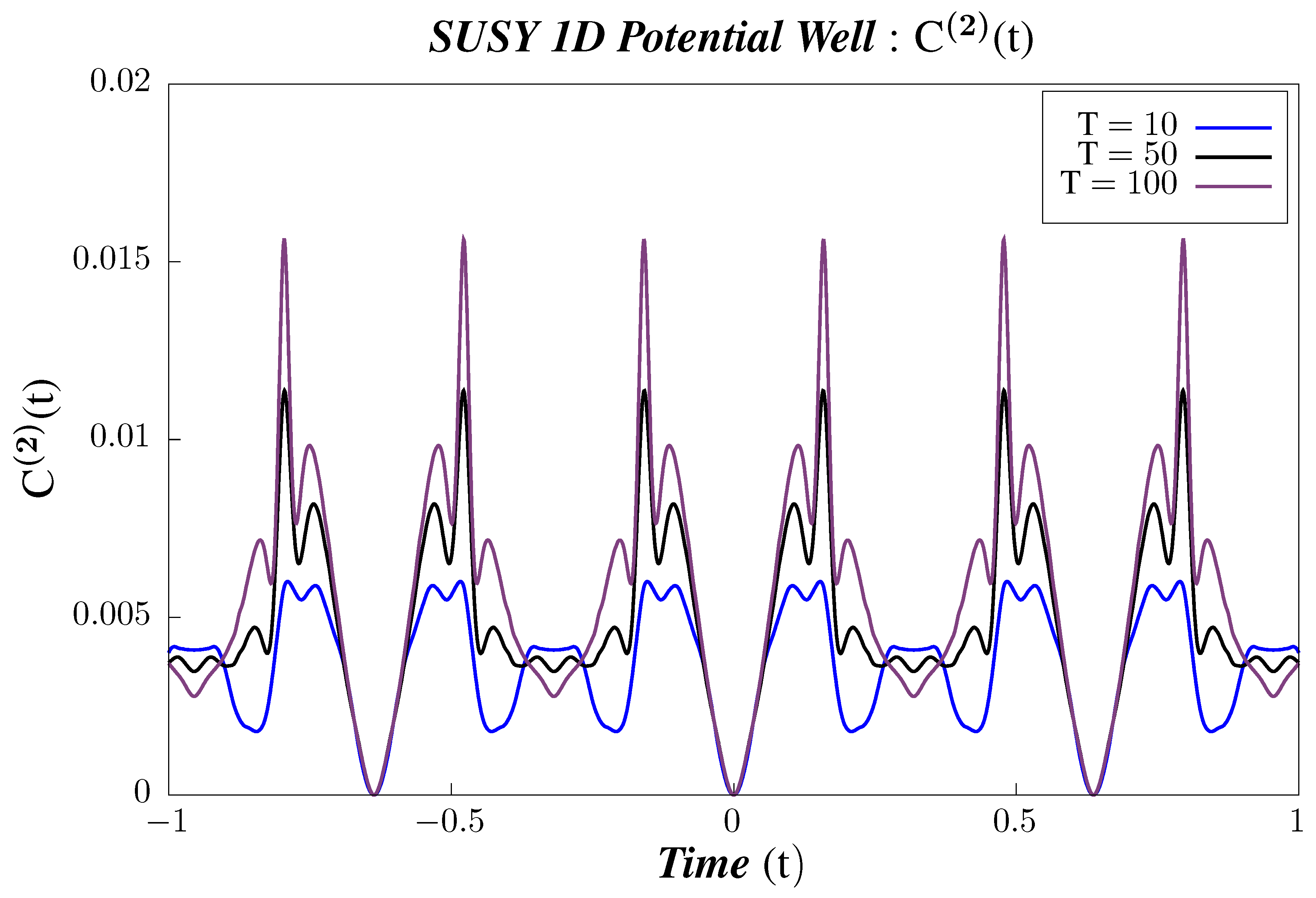

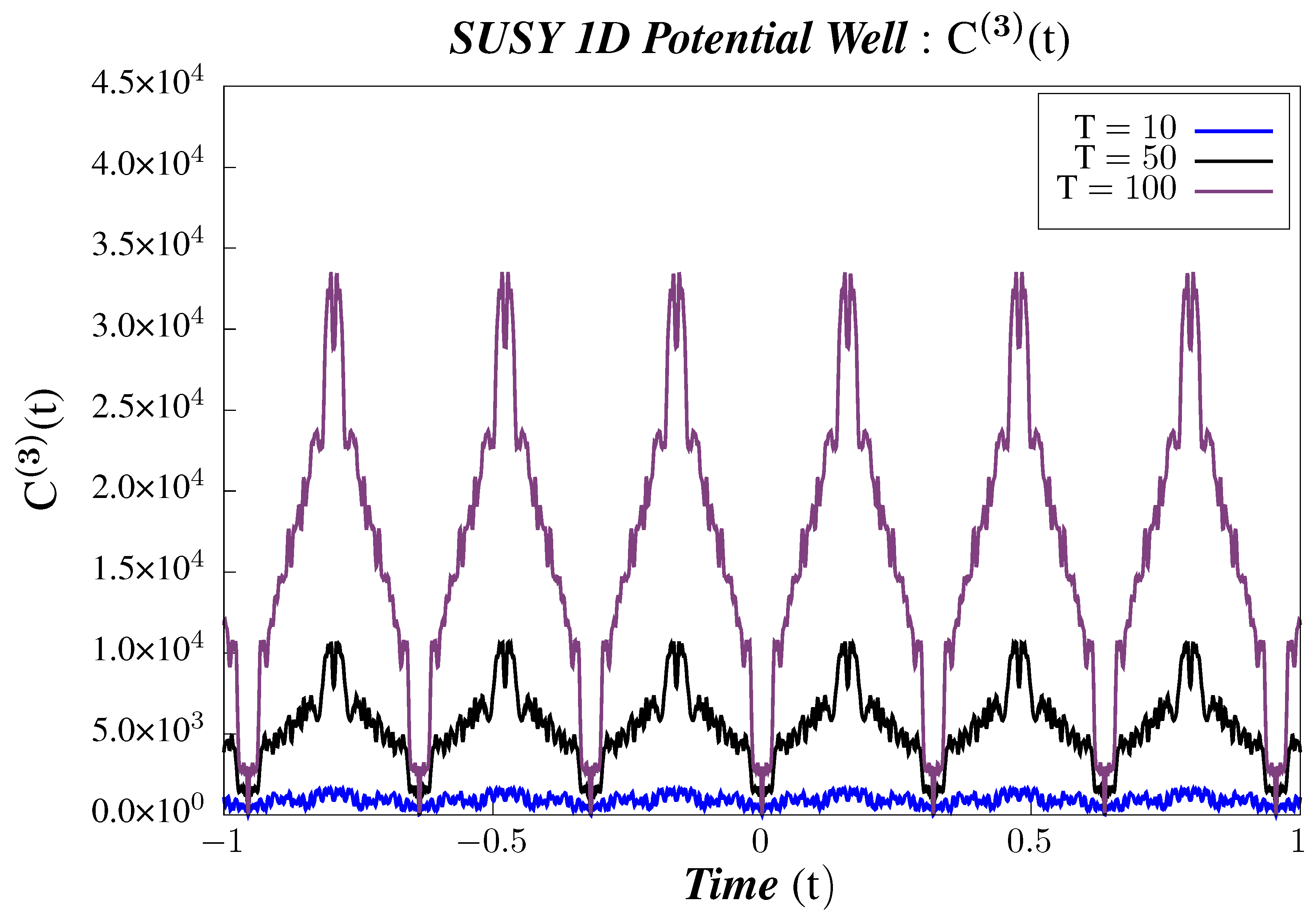

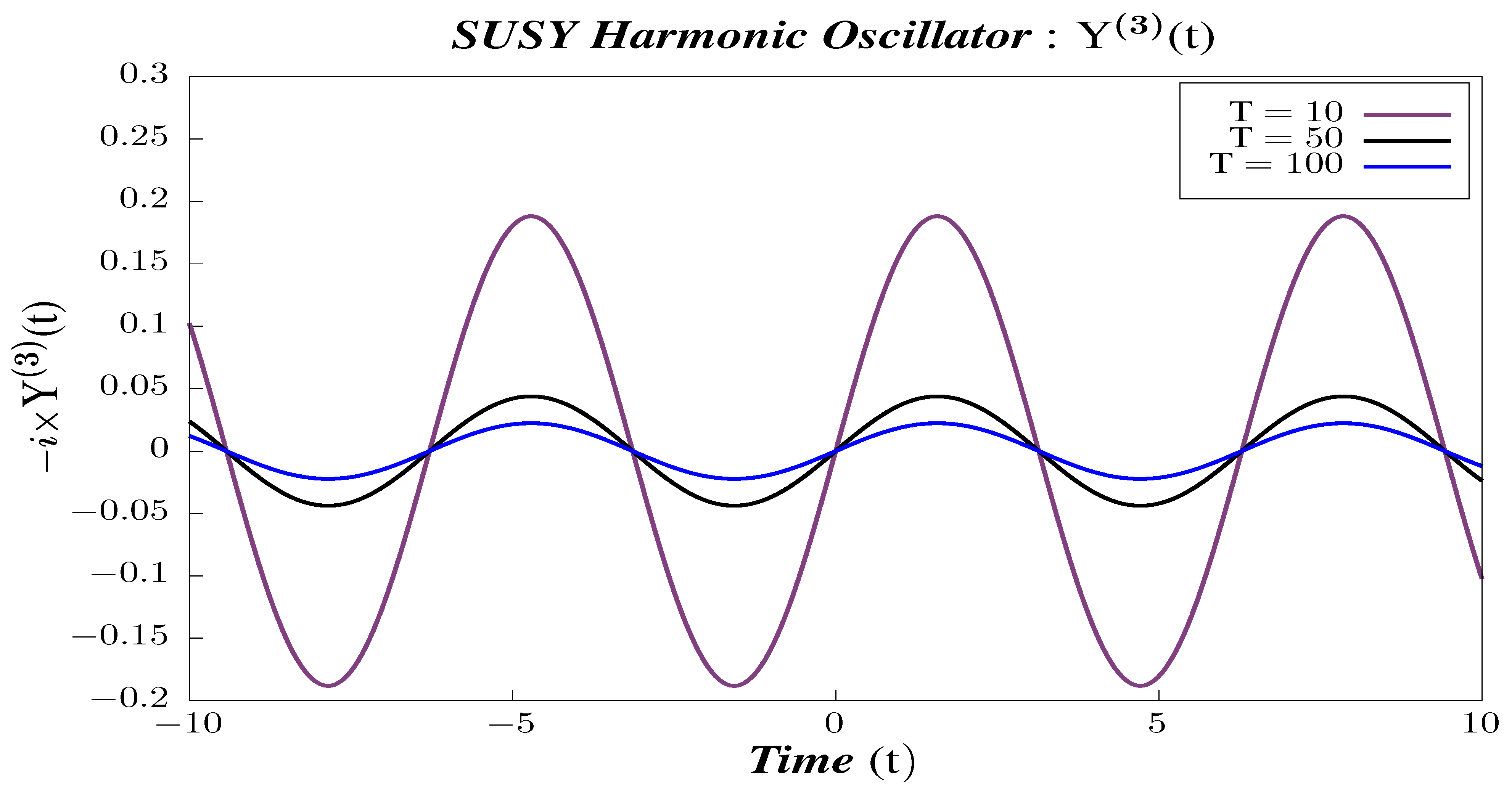

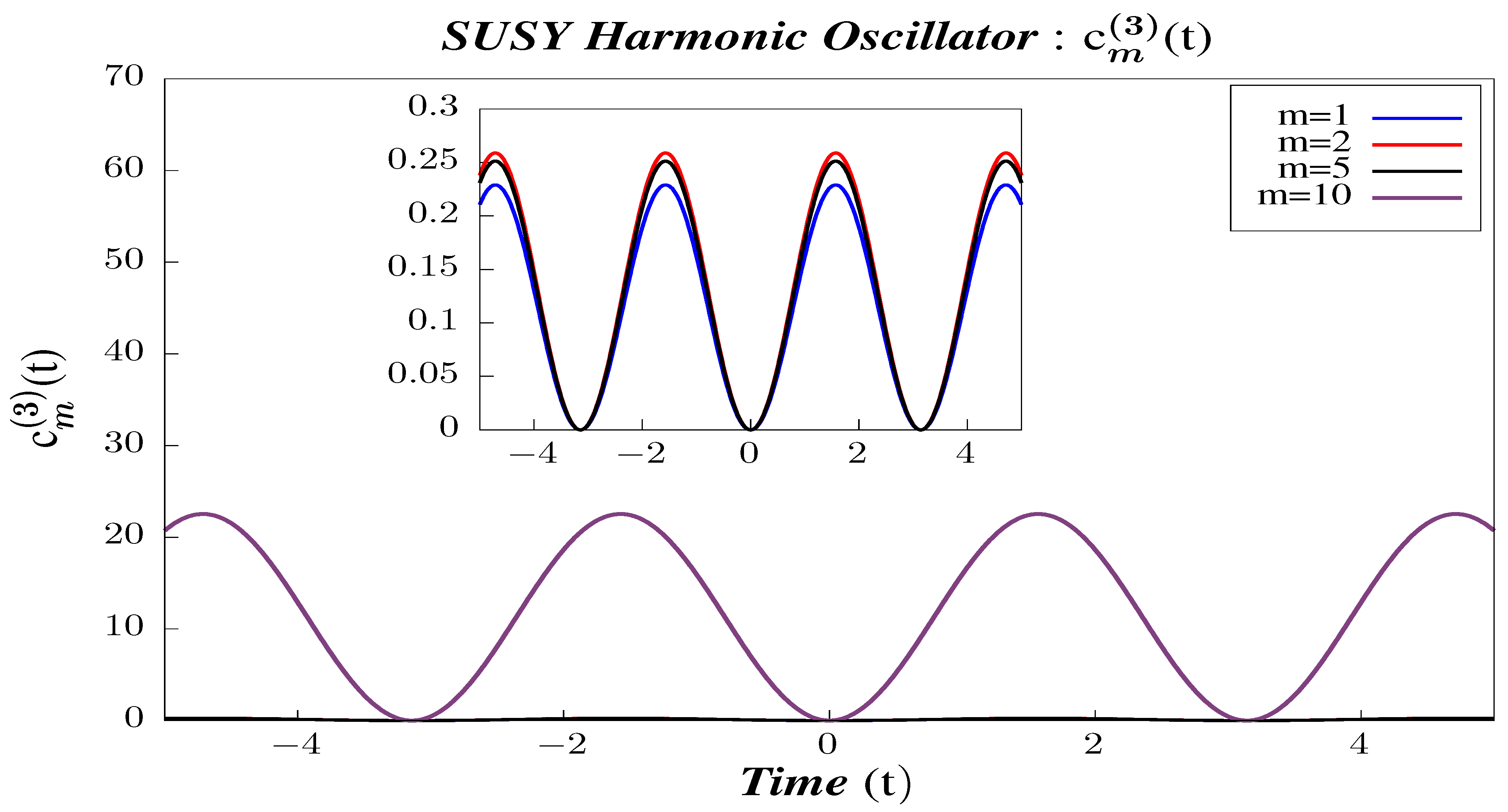

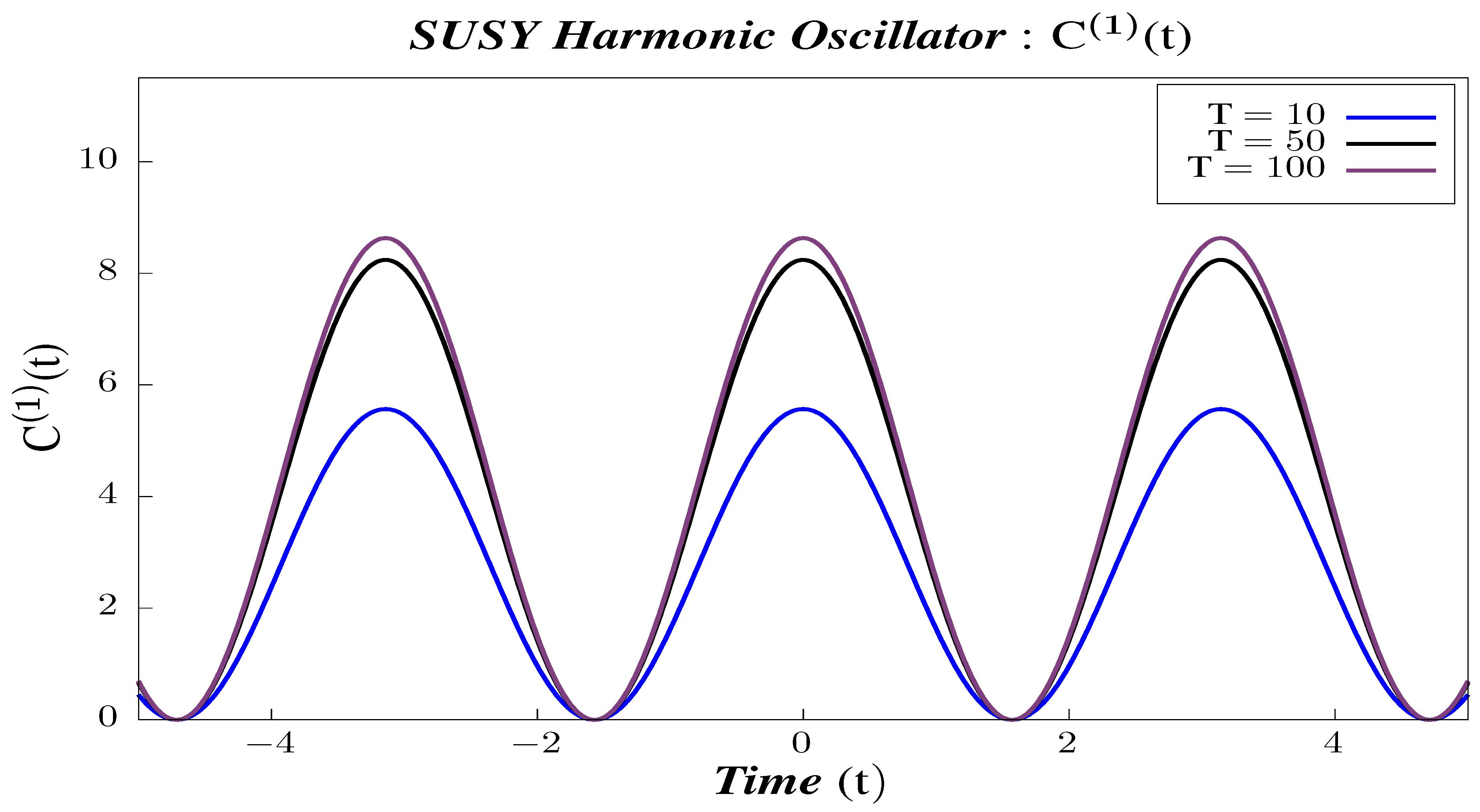

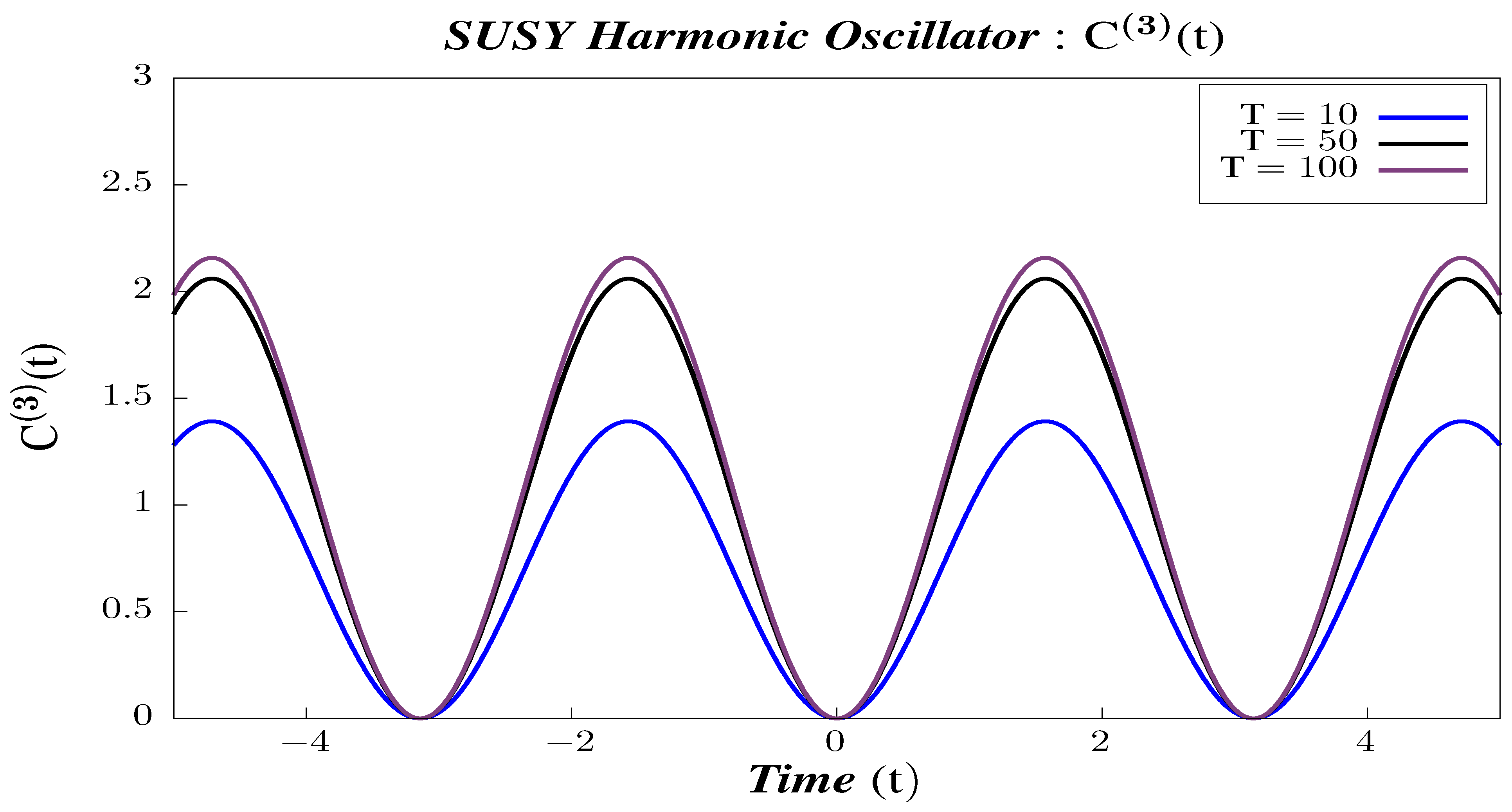

- Study B:The time dependence of 2-point and 4-point canonical correlators for three different temperatures: at fixed time . We have chosen units such that the Boltzmann Constant, , so that the inverse temperature, . This demonstrates the comparative behavior of canonical correlators for different temperature under time evolution.

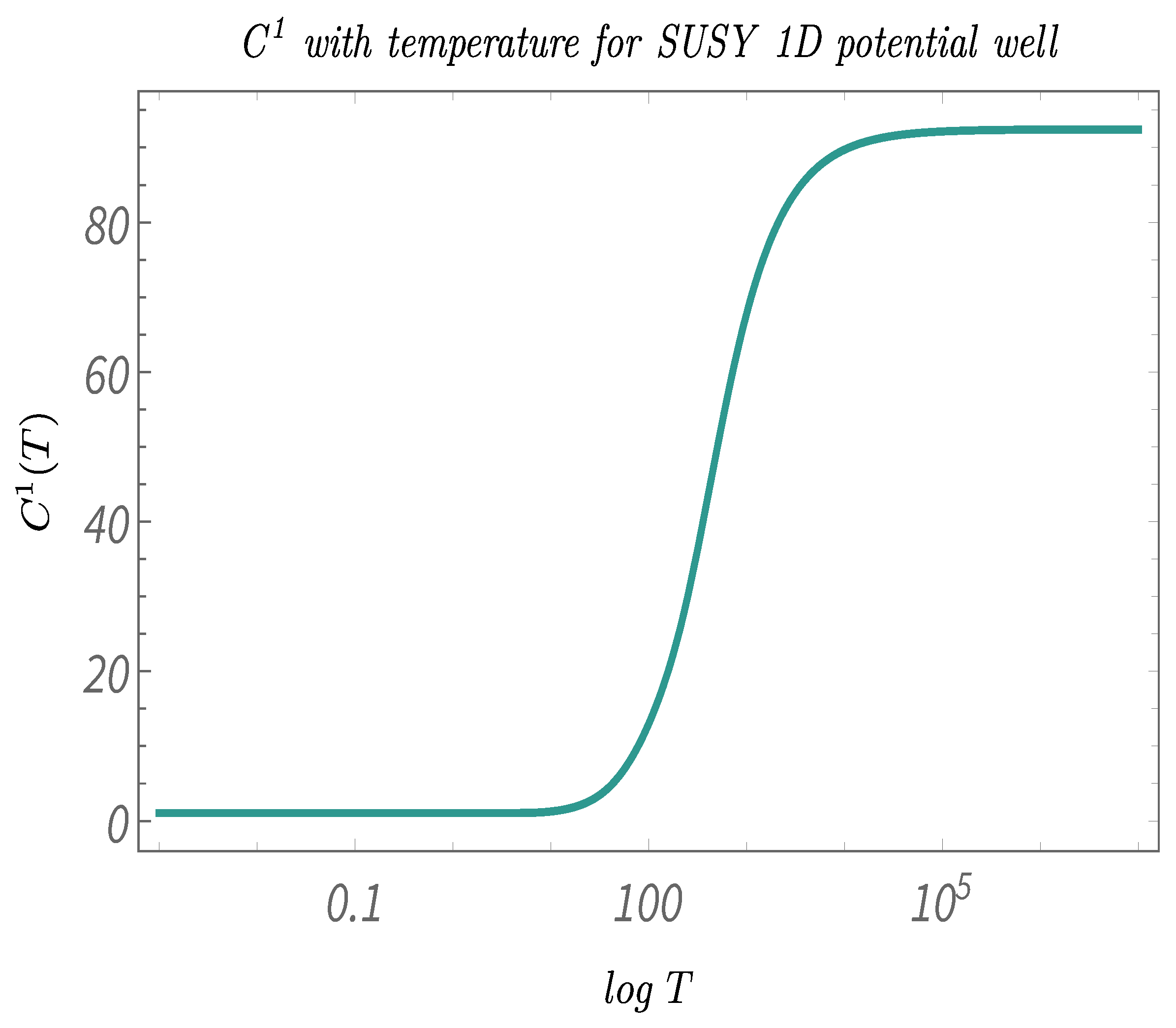

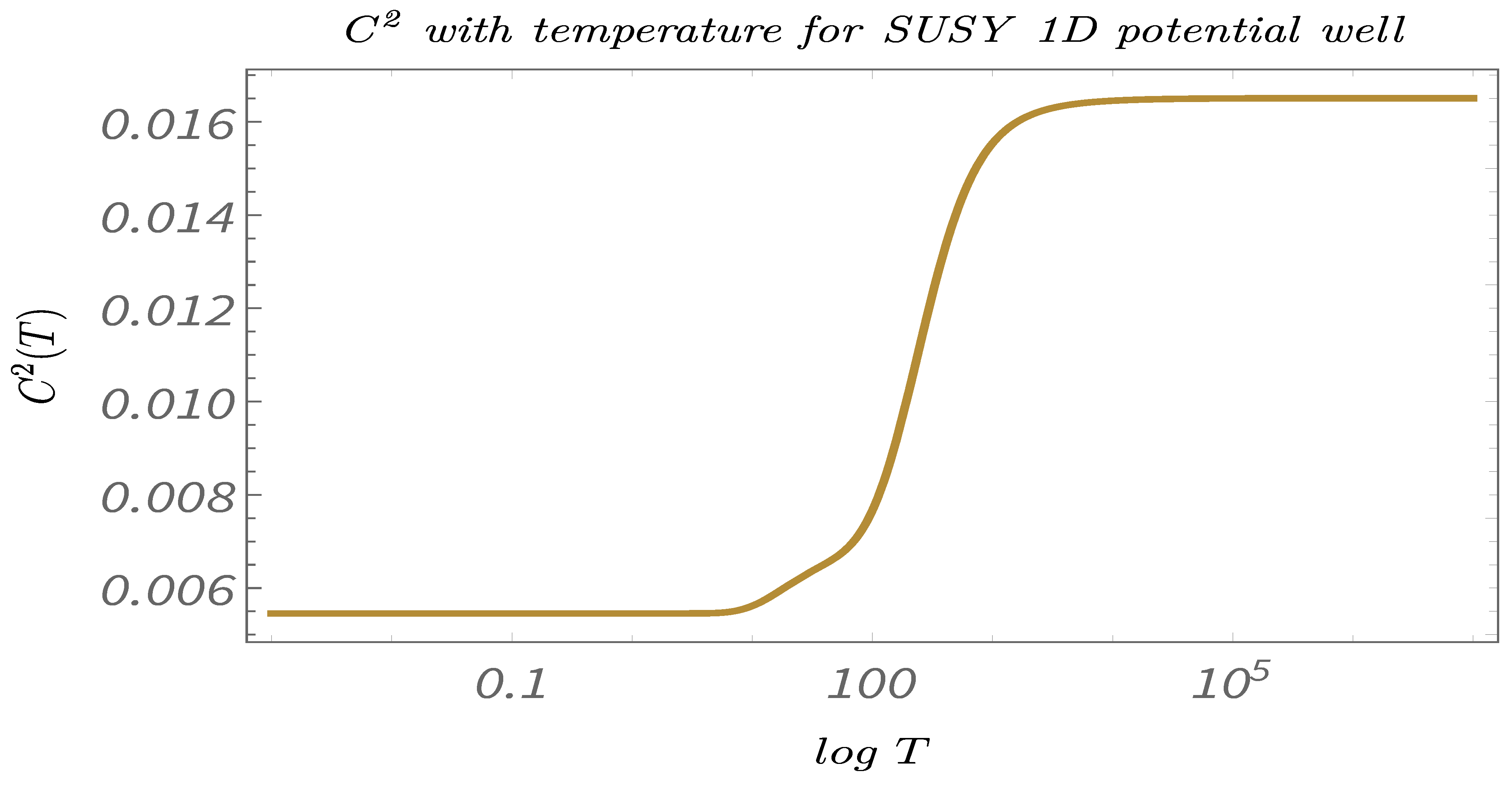

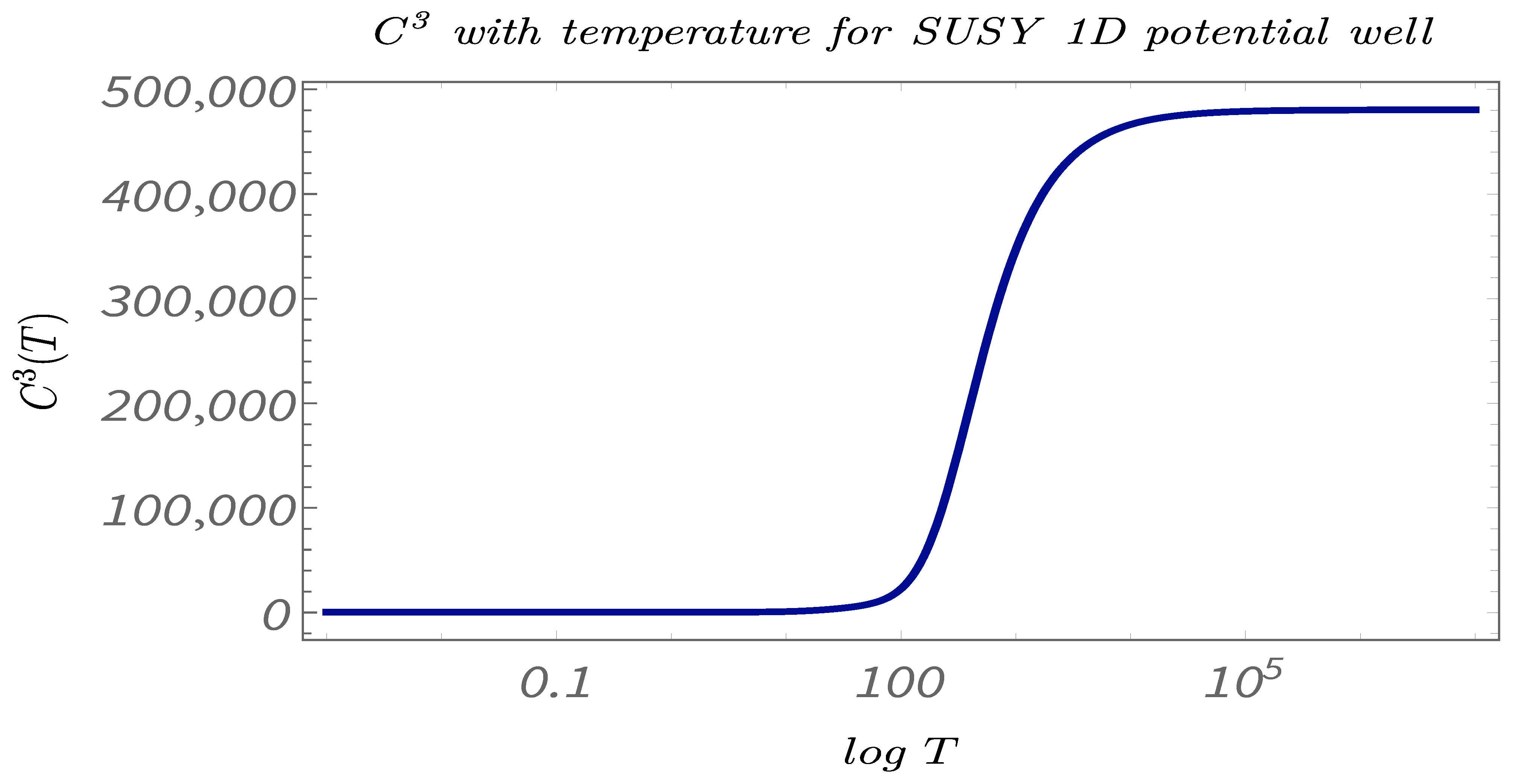

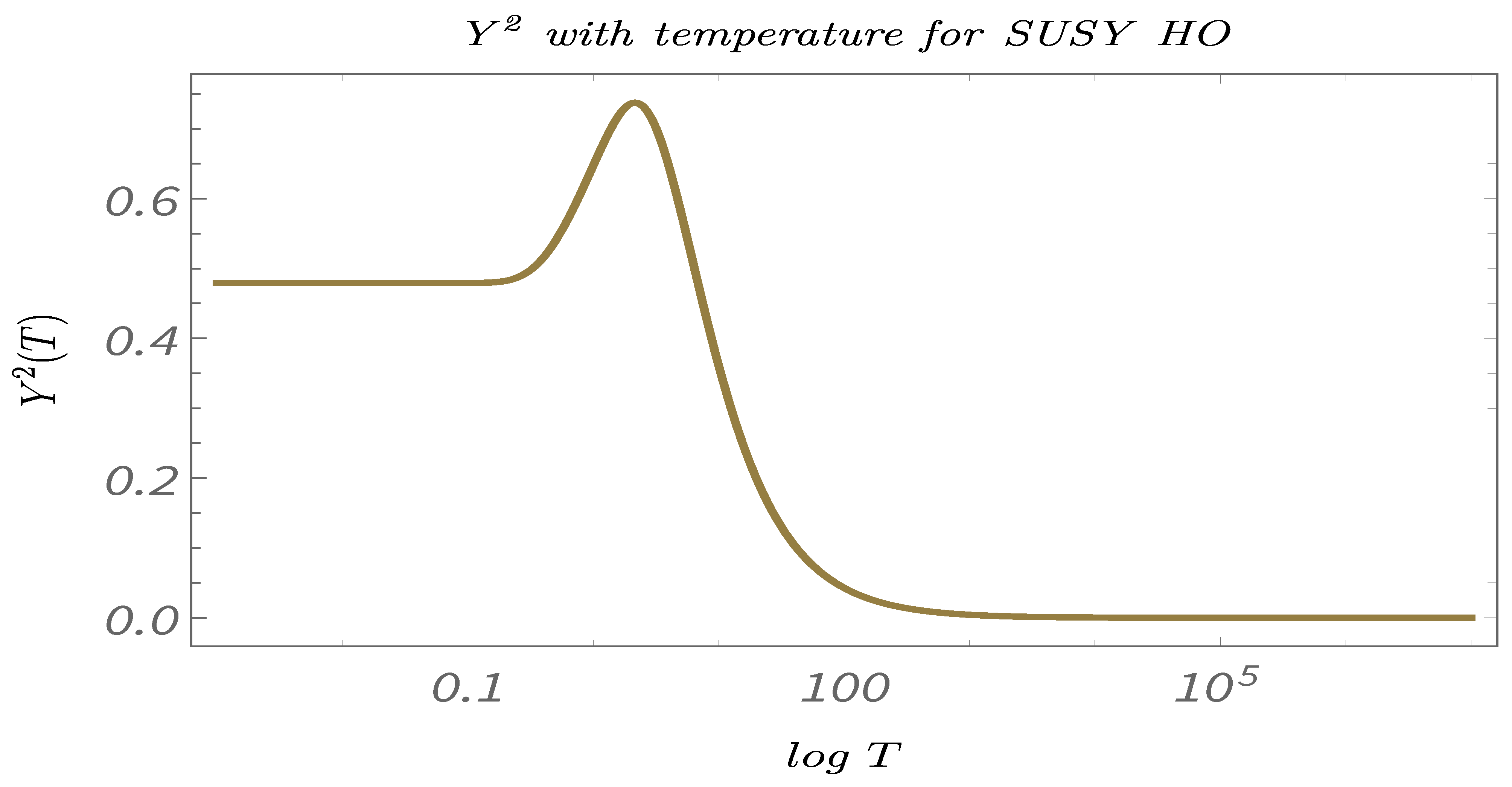

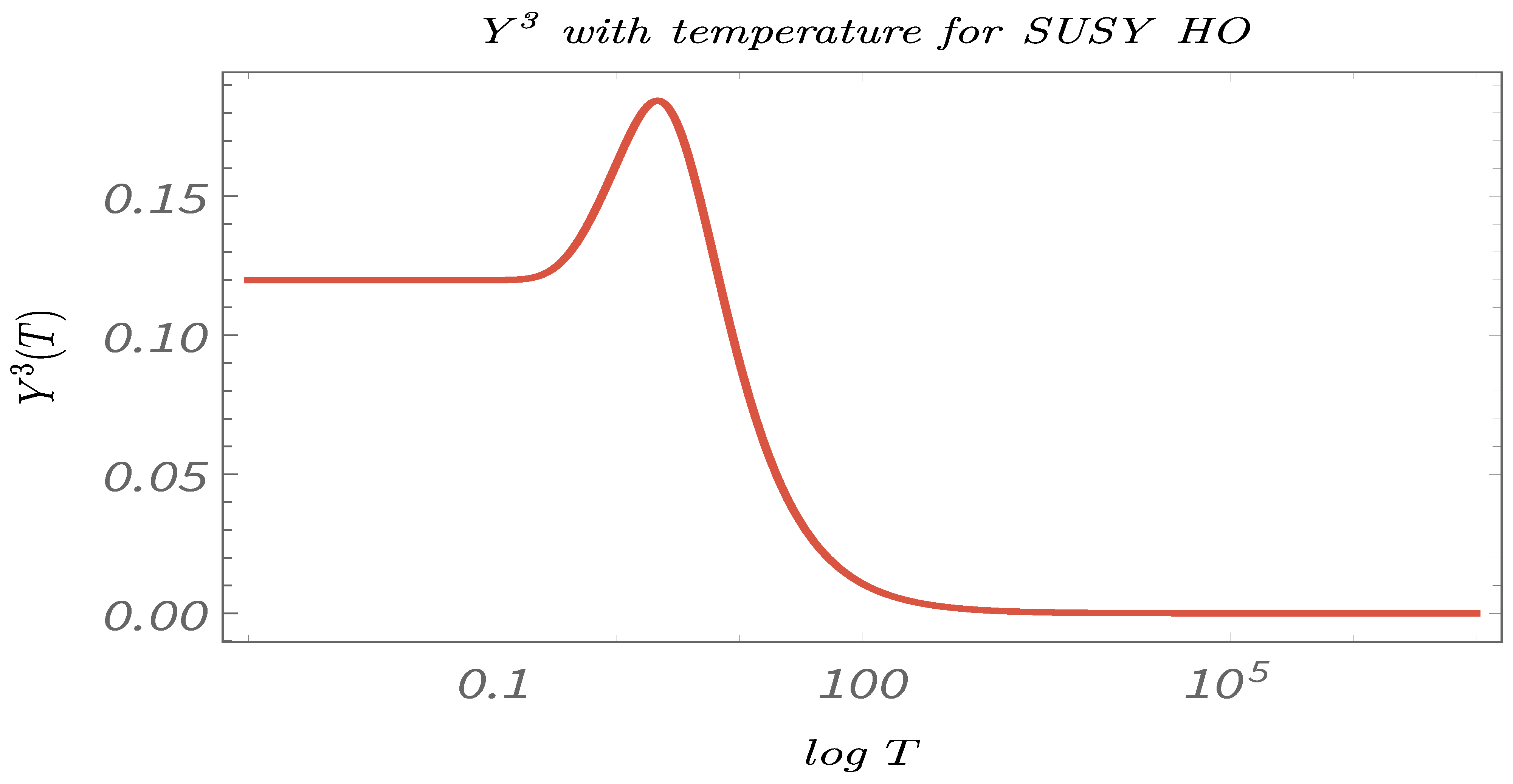

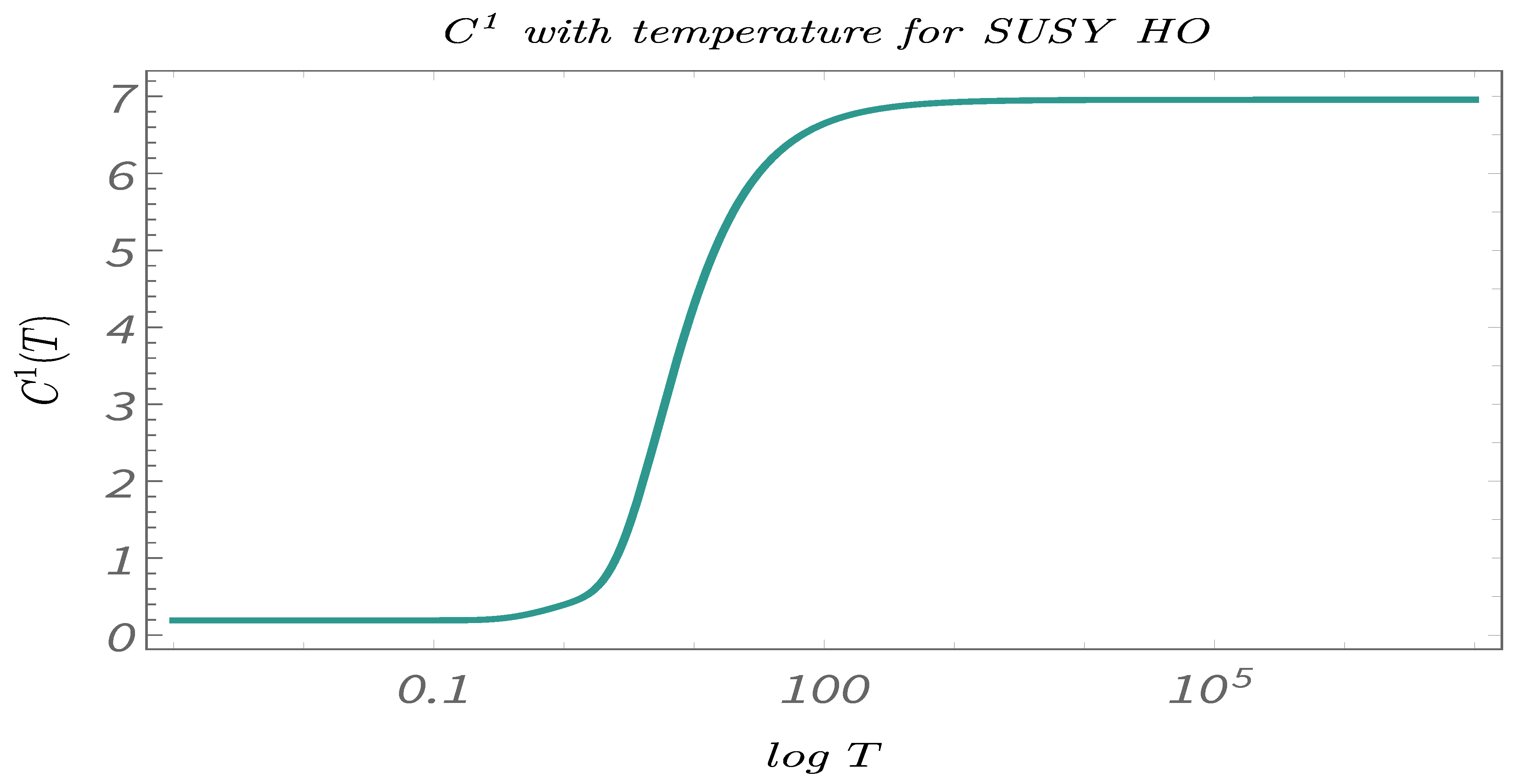

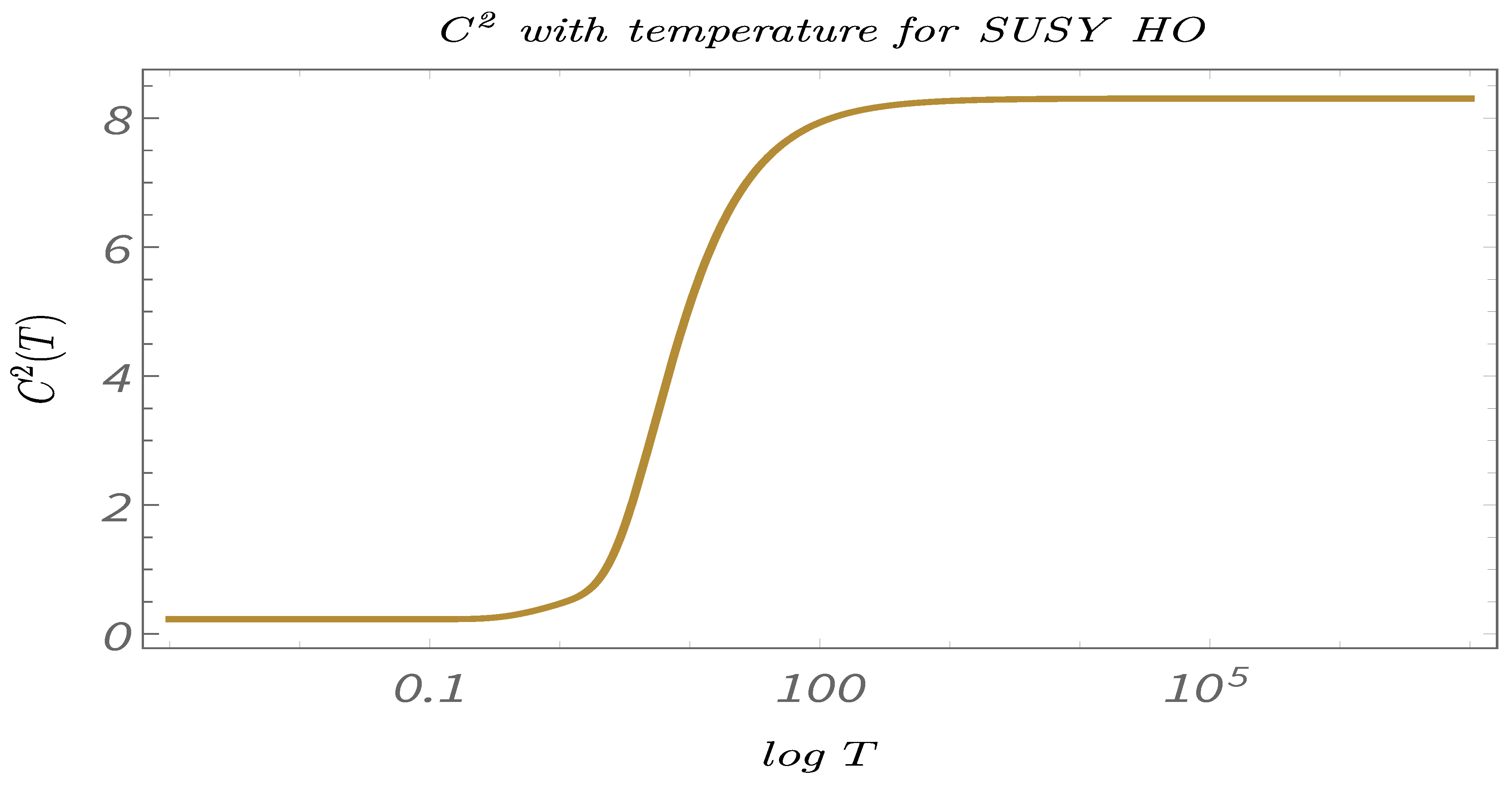

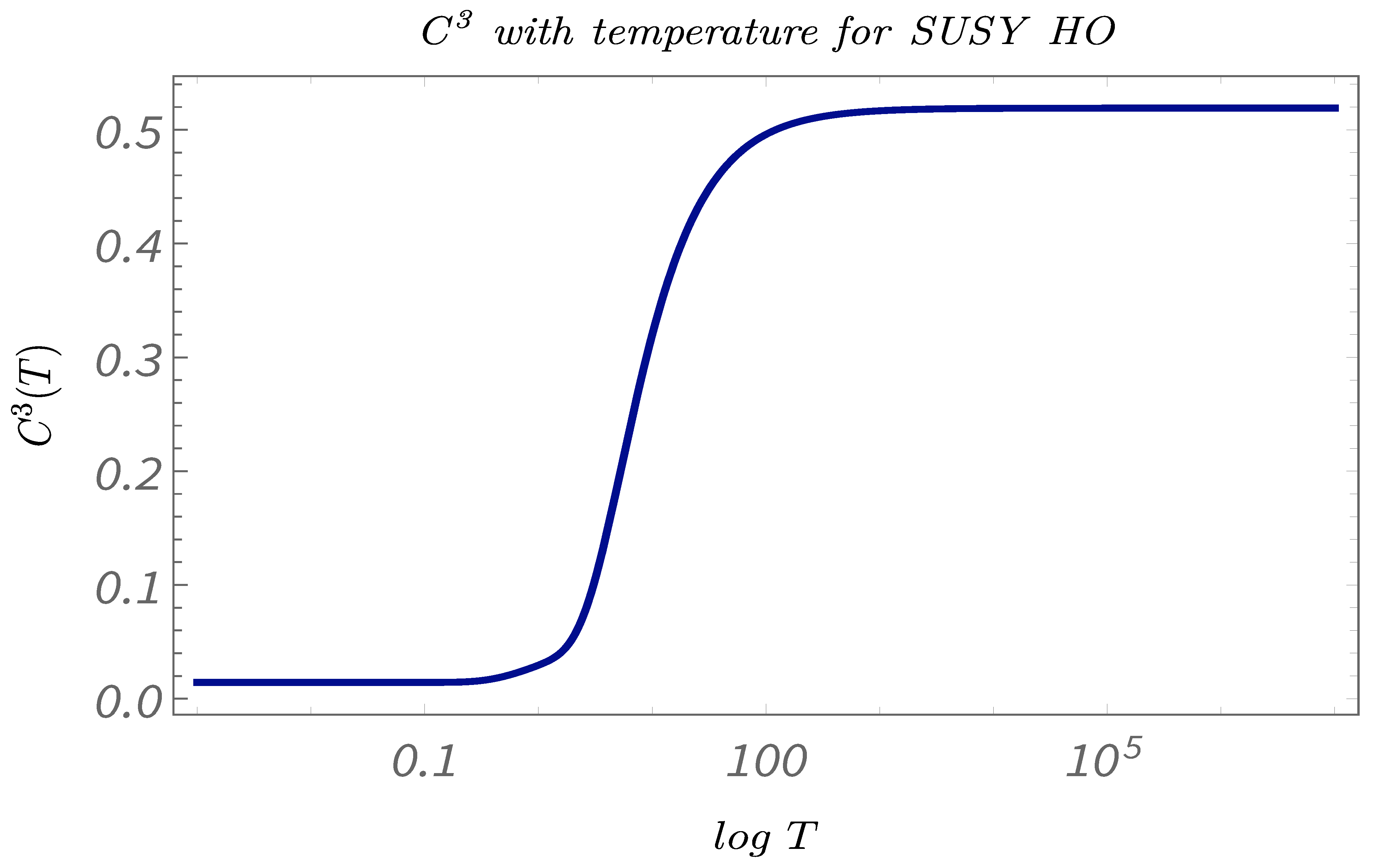

- Study C:The temperature dependence of the 2-point and 4-point canonical correlators in the temperature range: . This demonstrates the explicit temperature dependence of the canonical correlators.

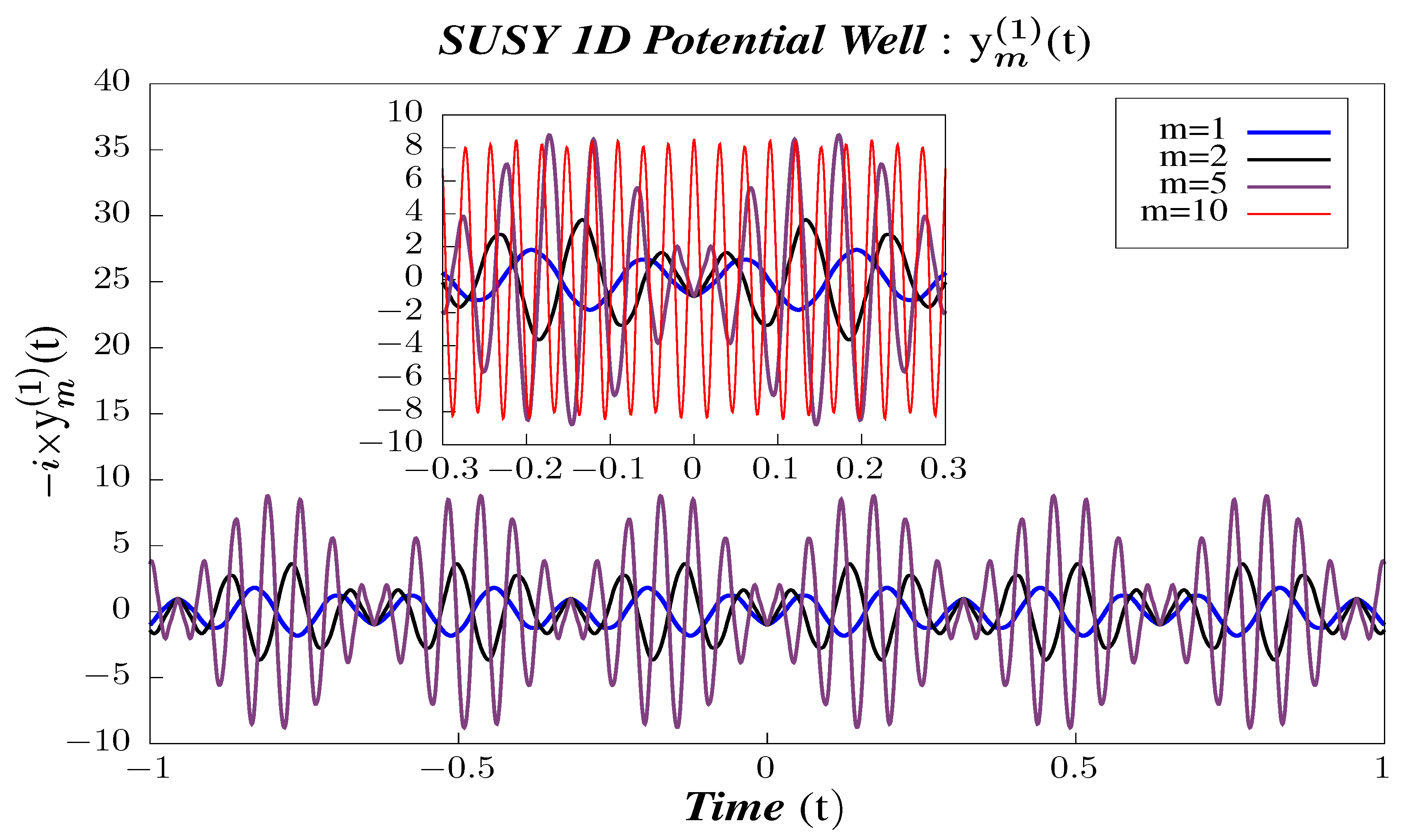

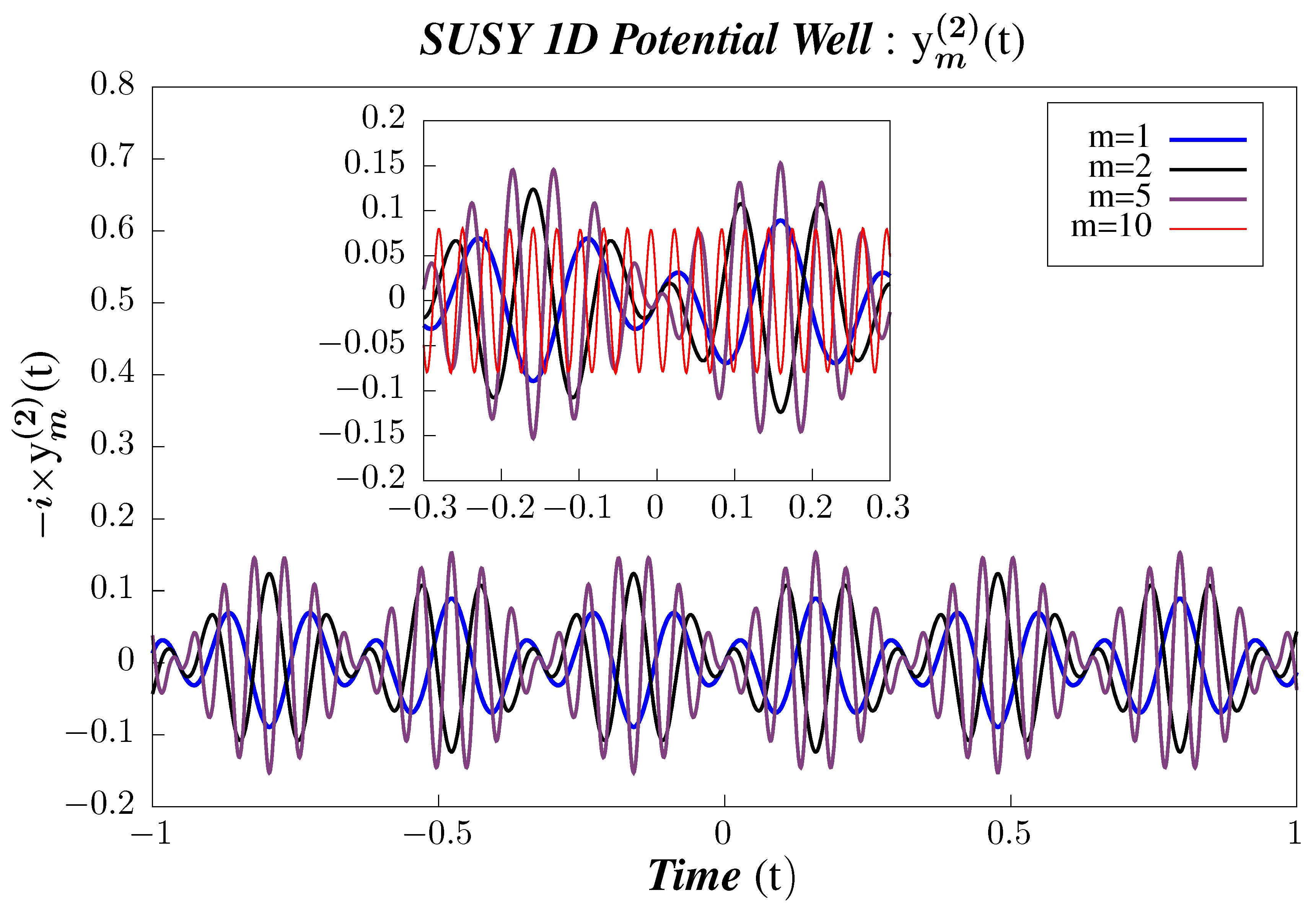

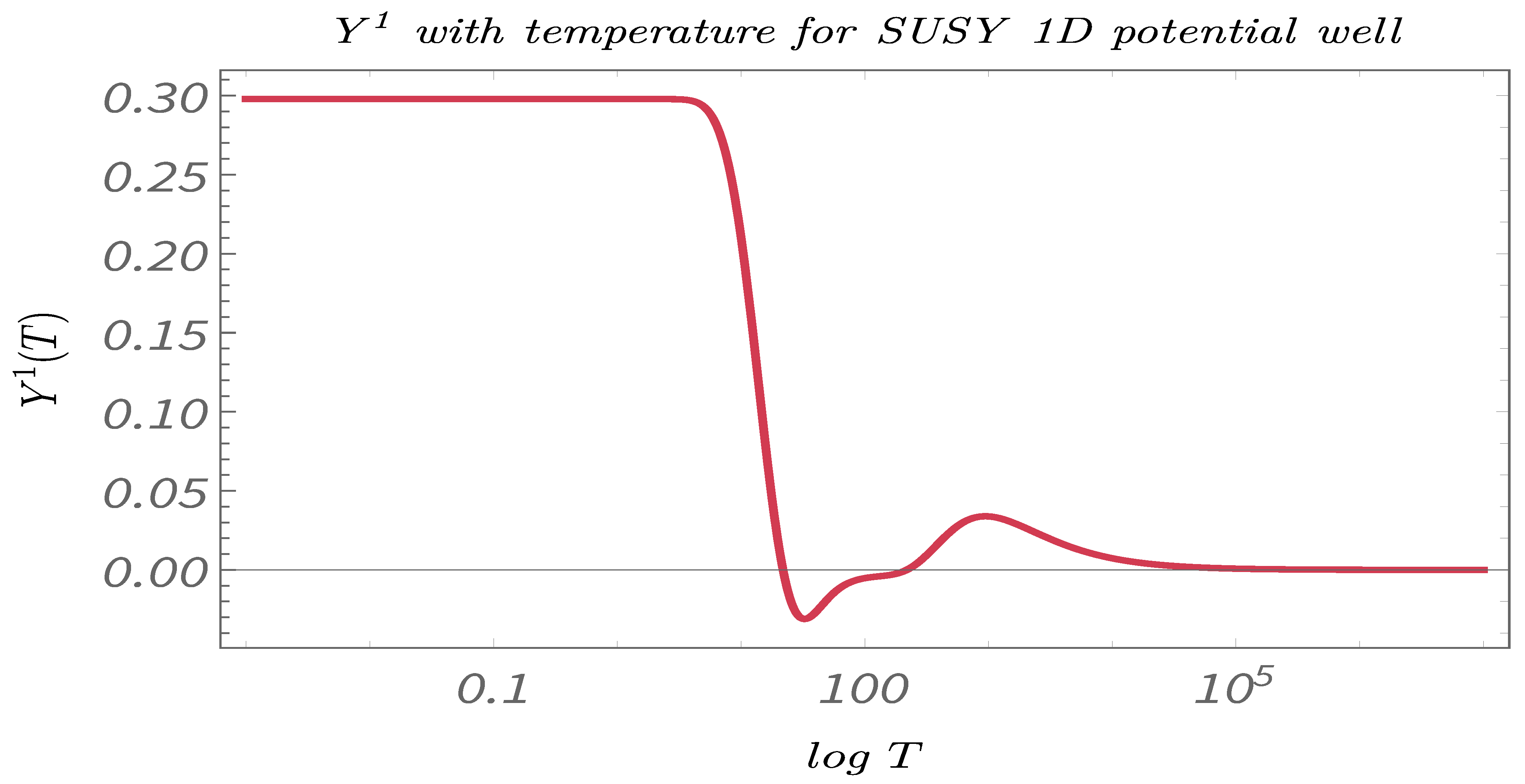

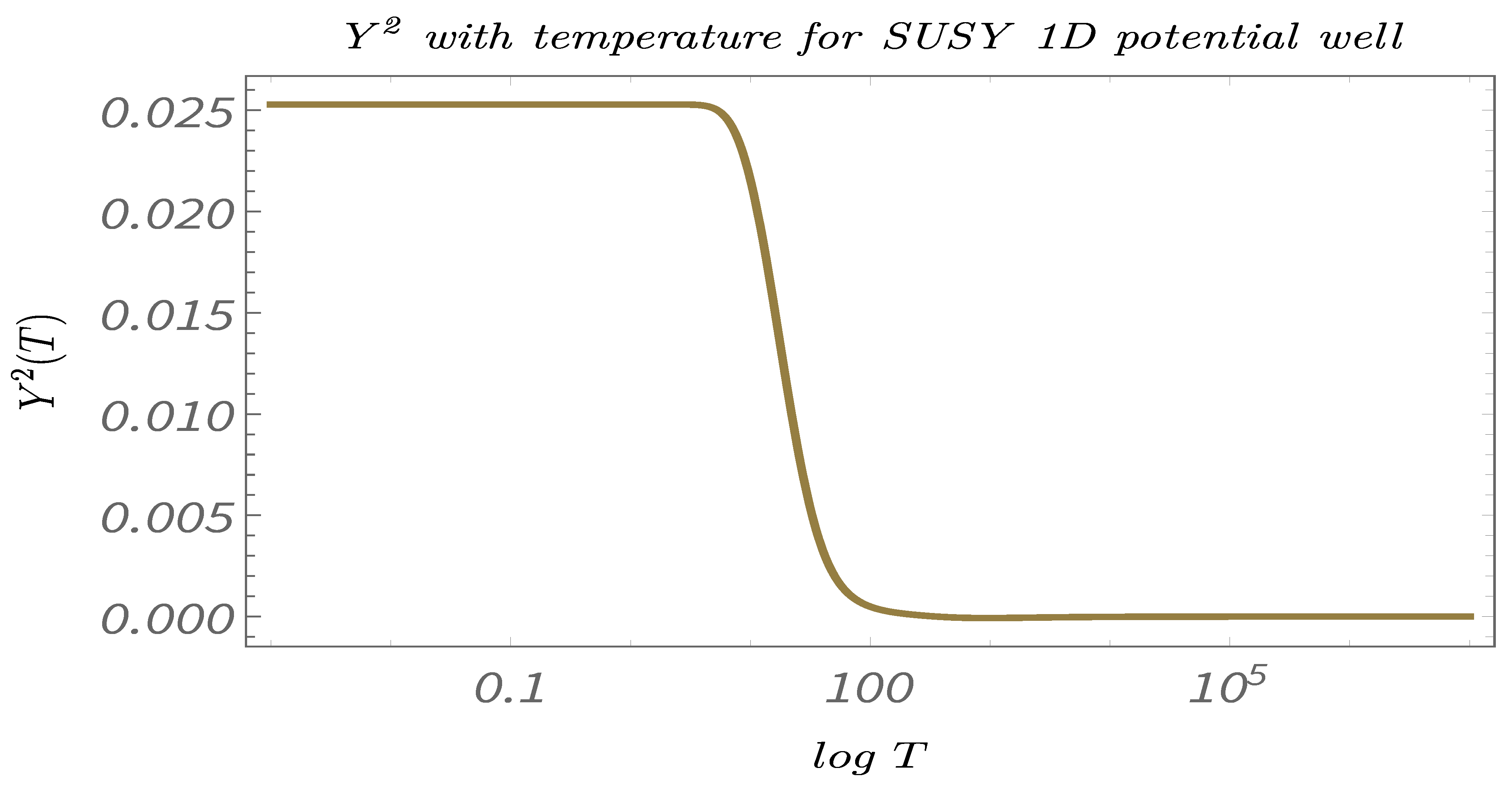

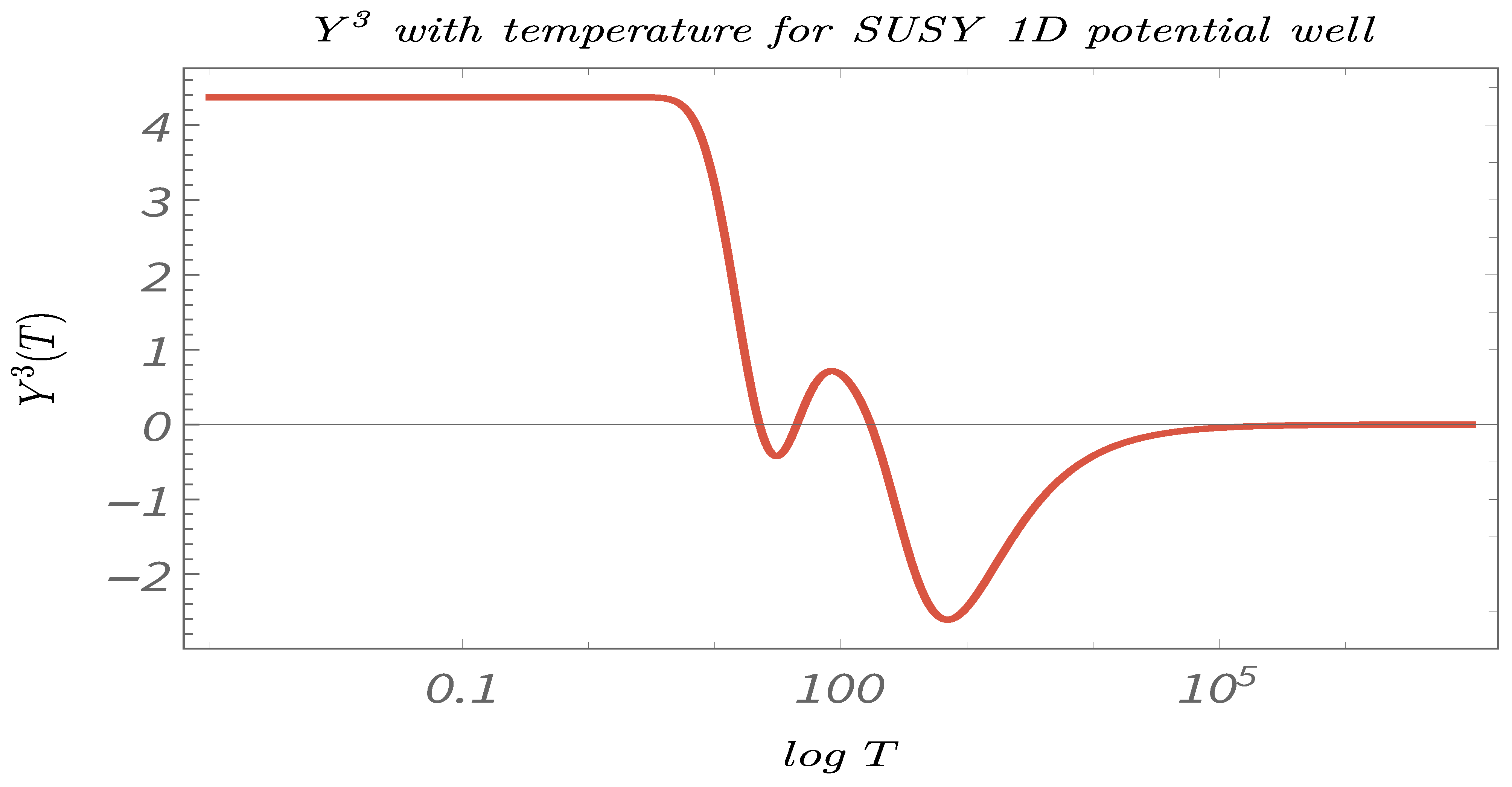

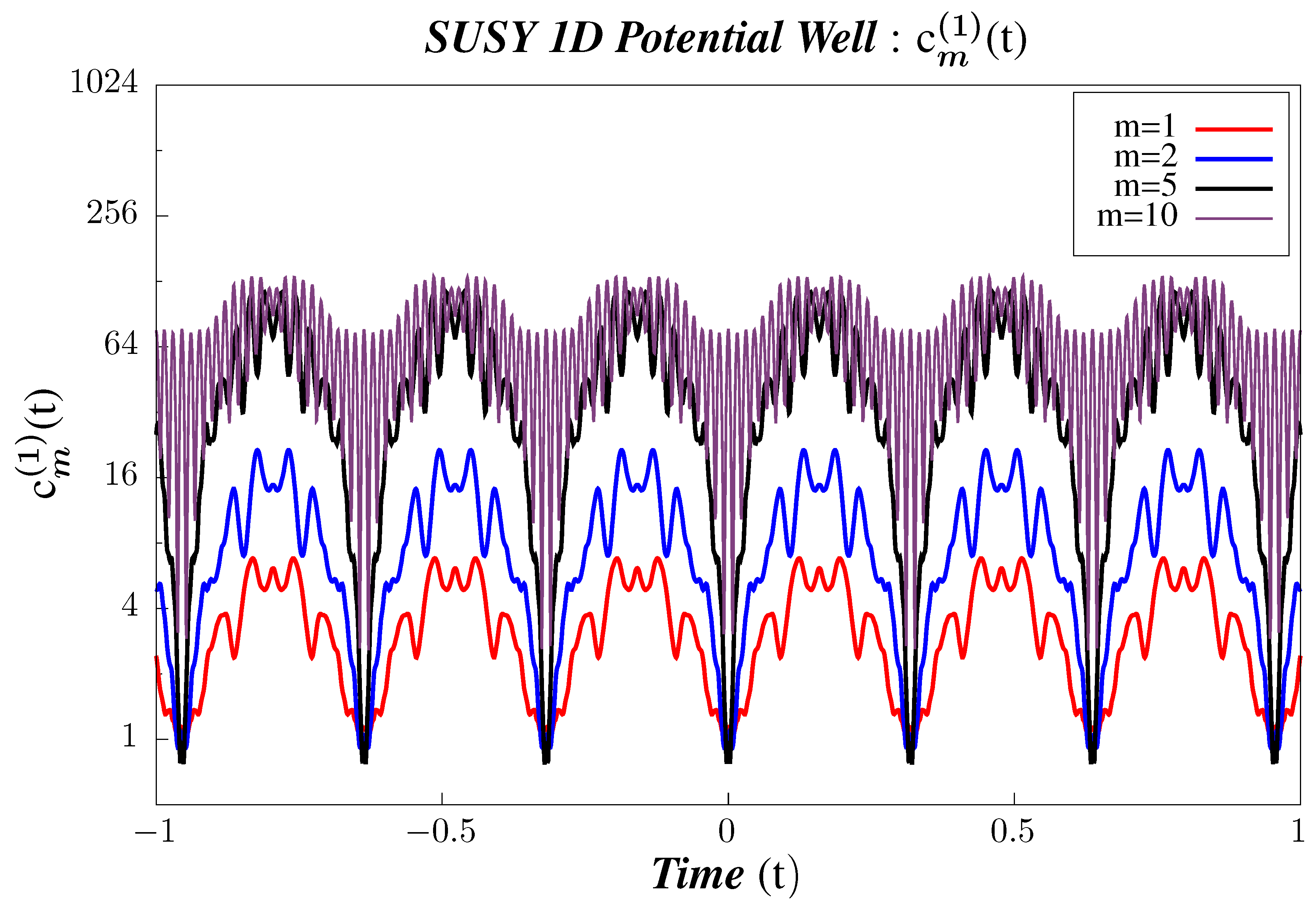

11.1. Supersymmetric 1D Infinite Potential Well

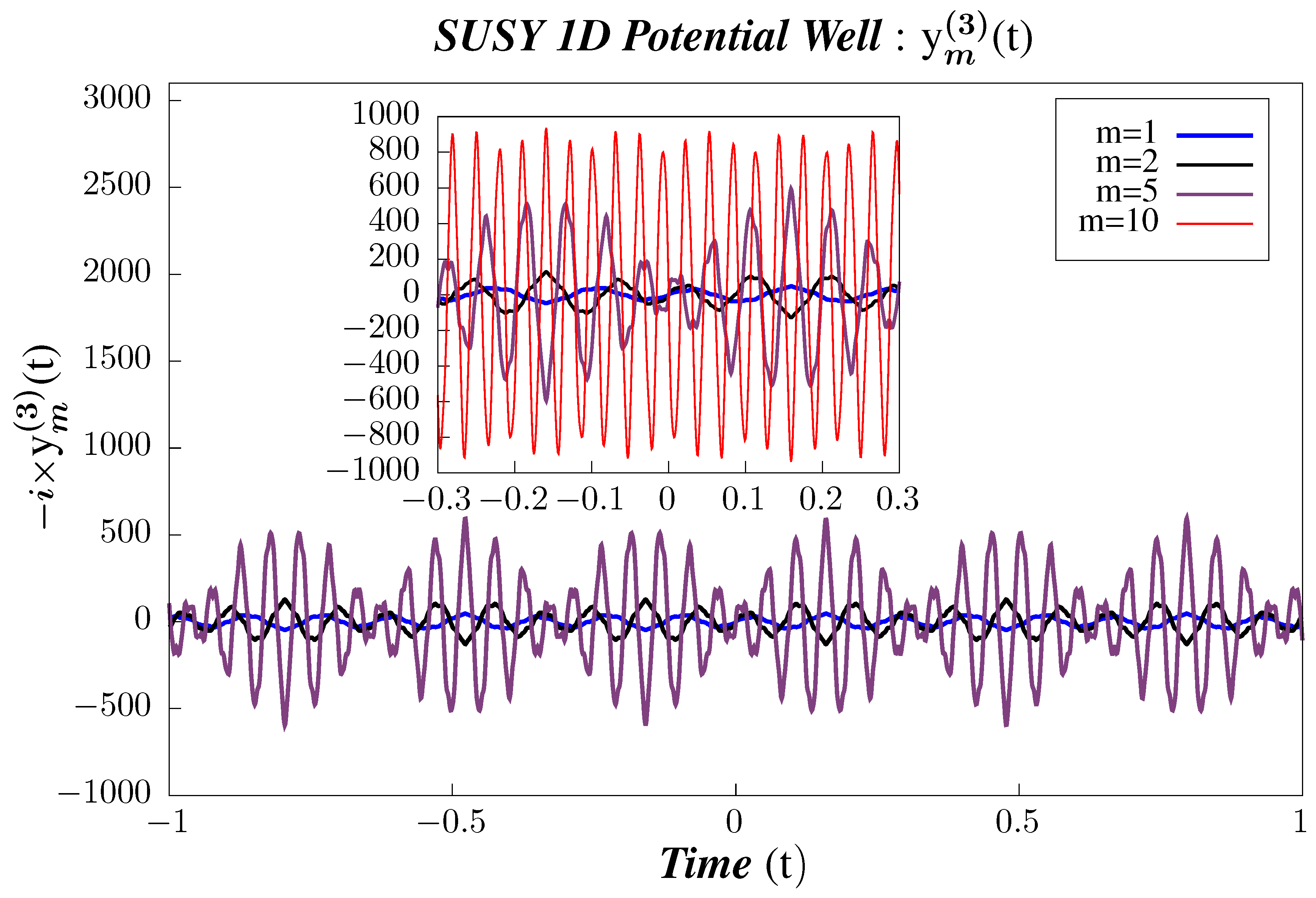

- In Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, we perform Study A on the 2-point micro-canonical correlators for Supersymmetric 1D Infinite Potential Well.

- -

- We observe that the correlators are periodic and that their periodicity does not vary with the state. For the correlator , the periodicity is . At present, there are no studies for the non-Supersymmetric case for , and we plan to do the same in a work which is to appear very shortly.

- -

- The amplitude of the correlators increases with increasing m, which primarily comes about because we have:in the correlator’s eigenstate representation, which increases with increasing state number.

- -

- It is also observed that, with a higher and higher excited state, the number of nodes increases and takes on the shape of a wave-packet. This is so because, as we go to higher and higher excited states, the high frequency modes become more and more prominent. So, the comparison of the scaling of the number of nodes here with non-Supersymmetric case is also important job to perform in near future.

- -

- In the insets of Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7, we have also plotted to draw a contrast of the boundary / truncation state with the other states. The correlators are lacking in features, sometimes deceptively so, as compared to the other states, which should come as no surprise because we have set our truncation at . Furthermore, this state appears to violate the properties shown by other intermediate states, but, in fact, this is merely an artefact of being the truncation state and that contribution of states with could not be accommodated in the calculations for .

- -

- The correlators largely follow the same patterns and behavior as shown by with two exceptions. First, the amplitude for correlator is suppressed, whereas that of is amplified, both by a factor of , as compared to . This comes from the absence of factor in and the presence of an additional factor in as compared to . Second is the contrasting behavior in the symmetry properties in t, whereas is symmetric in t, and are anti-symmetric.

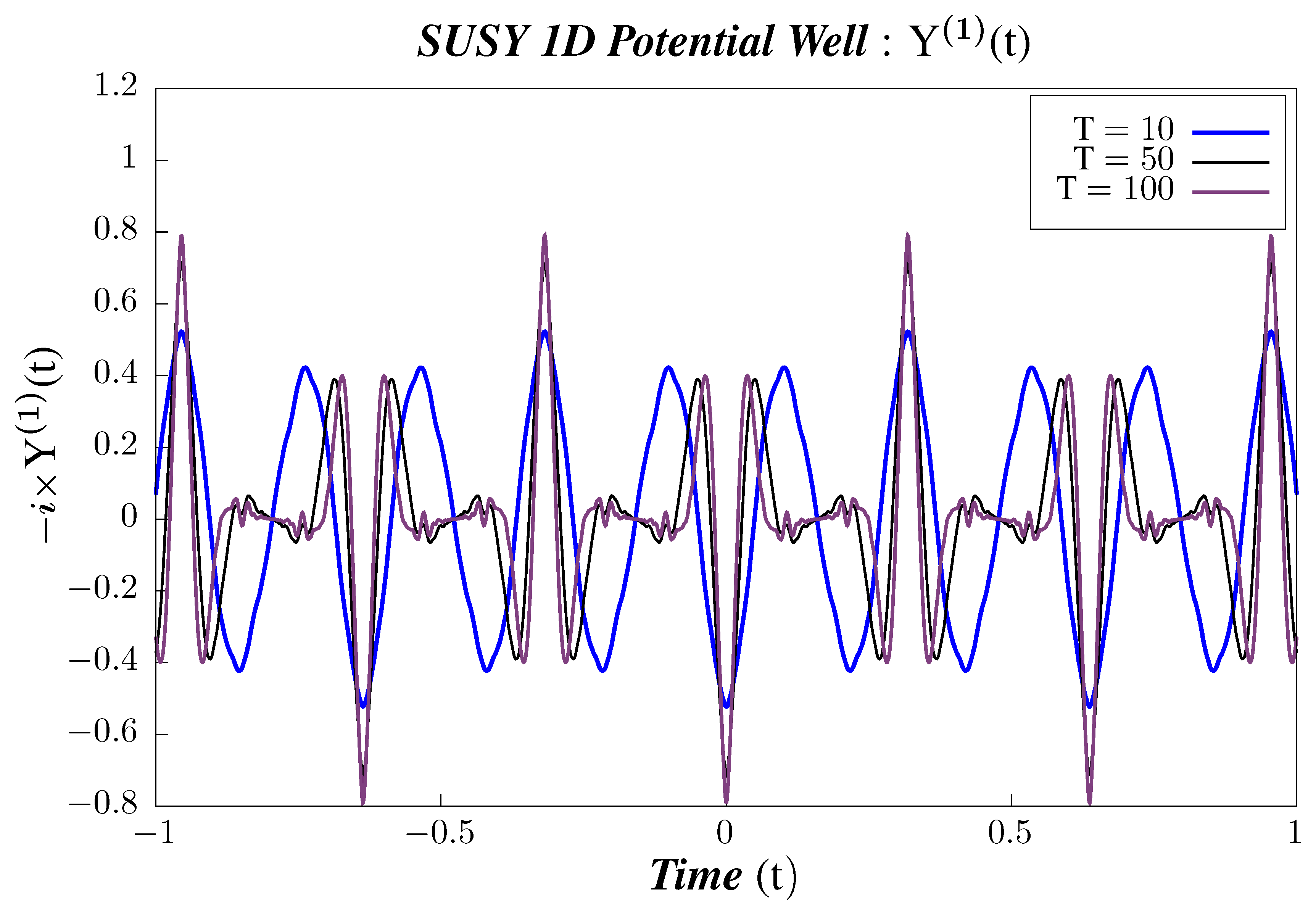

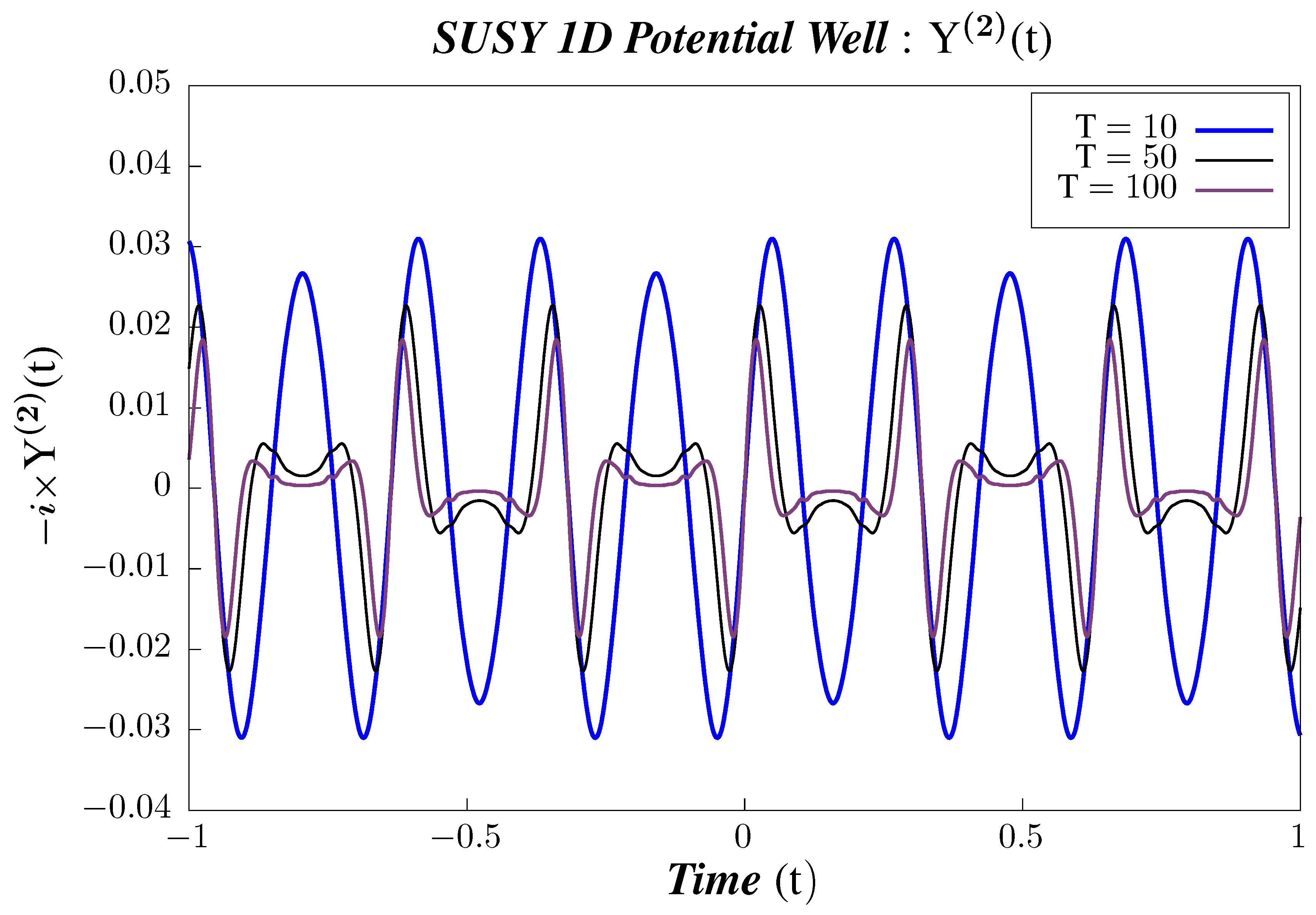

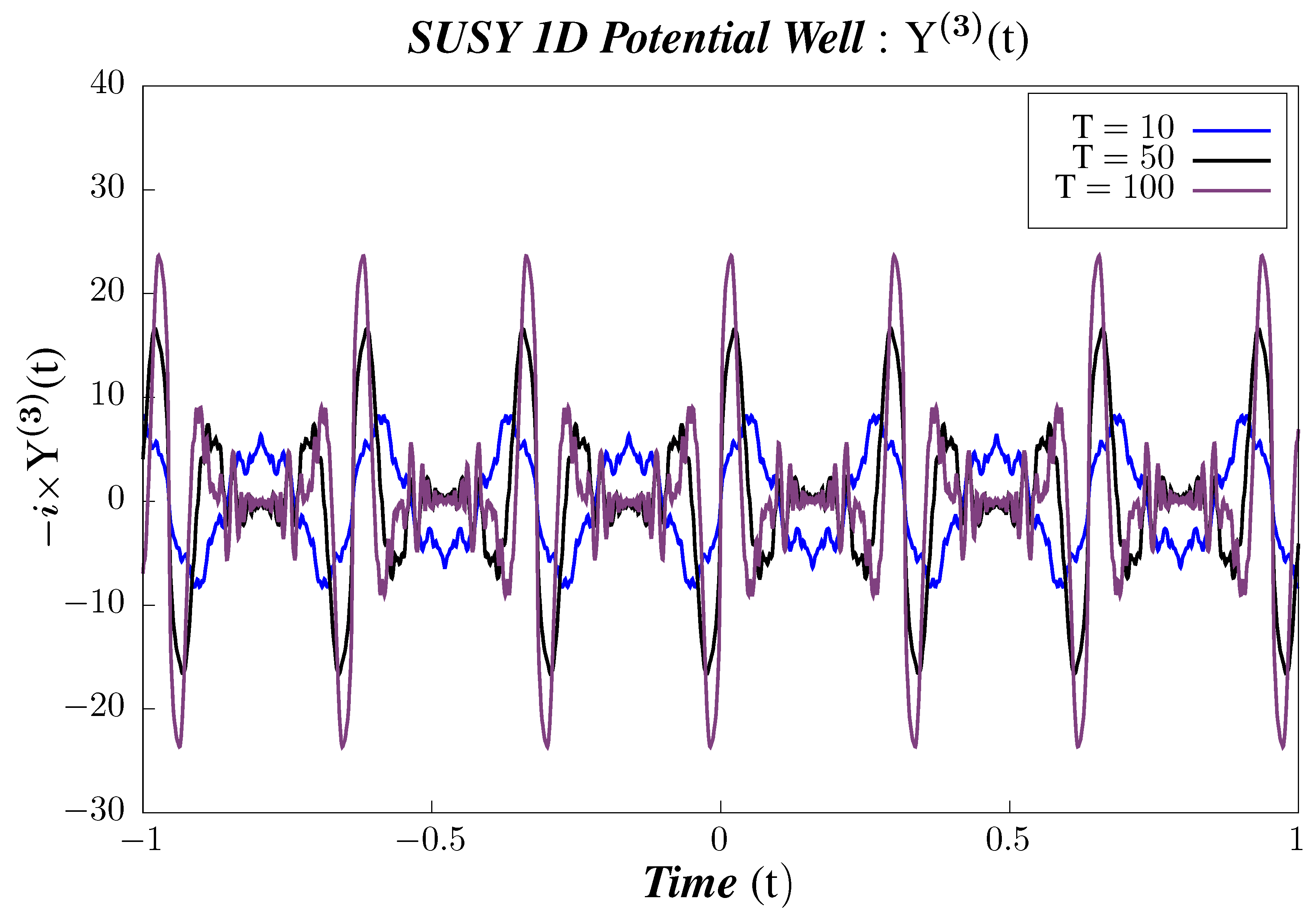

- We present the results of performing Study B and Study C on 2-point canonical correlators as follows:

- -

- In Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10, we perform Study B on the 2-point canonical correlators . We observe that the correlators shows periodic behavior for the different chosen values of temperature. We observe that, for , the mid temperature value 50 shows the minimum amplitude, whereas lower value of temperature (10) has greater amplitude. However, there is a sudden increase in the amplitude of the correlator for temperatures in the higher value range as can be seen from Figure 8. In correlators and , however, we follow a gradual pattern of decreasing amplitude with increasing in temperature, as observed from Figure 9 and Figure 10. To have a better understanding of the temperature dependence of the 2-point correlators, we plot them with varying temperatures, keeping the time constant.

- -

- In Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13, we perform Study C on the 2-point canonical correlators . We plot, respectively, , which are the thermal or canonical correlators corresponding to , respectively, with respect to temperature. It is clearly visible that, for very low temperatures, the canonical correlators are constant. However, after a certain value of the temperature, the correlators decays rapidly and falls off to zero within a small temperature range.

- -

- -

- We observe that the correlators are periodic and that their periodicity does not vary with the state. For the correlator , the periodicity is , which is roughly half of the corresponding 2-point micro-canonical correlator. We note that this is approximately the same periodicity, within numerical error, observed in the case of non-Supersymmetric 1D Infinite Potential Well as obtained by Hashimoto et al. [90]. Hence, we conclude that introducing Supersymmetry in integrable QMcal models does not affect the periodicity of 4-point micro-canonical correlators. At present, there are no studies for the non-Supersymmetric case for , and we plan to do the same in a work which is to appear very shortly.

- -

- Other properties of are much like . We observe a similar increase in the amplitude of the correlators with increasing m. The scaling of amplitudes in the case of 4-point micro-canonical correlators is with a factor of instead of a factor as is the case with such that the relative order of amplitudes can be arranged as: .

- -

- All are symmetric about , which means that, to these 4-point micro-canonical correlators, it does not matter whether or .

- -

- In Figure 17, Figure 18 and Figure 19, we perform Study B on the 4-point canonical correlators. We plot the 4-point canonical correlators for three different temperatures. We observe that all the 4-point correlators shows periodic behavior irrespective of the value of the temperature. It is also observed that, for each correlator, the amplitude increases with the increasing temperature. To have a better understanding of the temperature dependence of the 4-point correlators, we plot them with varying temperature, keeping the time constant.

- -

- In Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 22, we perform Study C on the 4-point canonical correlators. we plot, respectively, , which are the thermal or canonical correlators corresponding to , respectively, with respect to temperature. It is observed that, for low temperatures, the 4-point correlators show negligible value. However, after a certain threshold temperature, the 4-point correlators increases and then saturates to a certain finite value.

- The temperature-dependent plots for the 2-point and the 4-point canonical correlators suggests that both the 2- and the 4-point canonical correlators are essential if one wants to have a complete understanding of the phenomenon of Quantum randomness. The plots suggests that 2-point correlators are a better probe for understanding Quantum randomness at low temperatures, whereas, at high temperatures, it is actually the 4-point correlators, which is more significant. However, in the mid-temperature range, the 2-point and the 4-point correlators have exactly opposite behavior. Hence, to understand the significance of temperature in this range on any Supersymmetric Quantum mechanical model, having knowledge of both 2- and 4-point correlators is of utmost importance.

11.2. Supersymmetric 1D Harmonic Oscillator

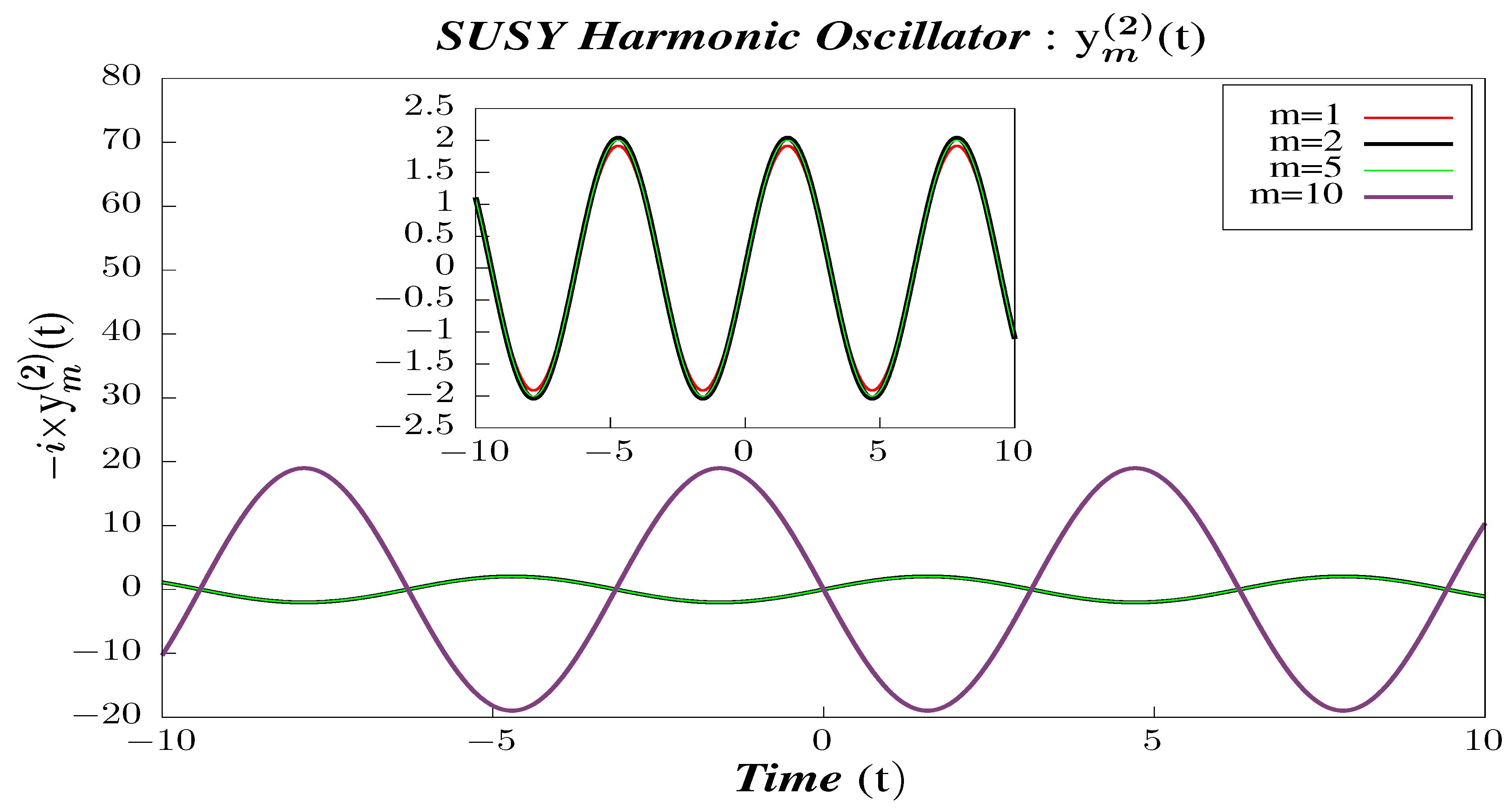

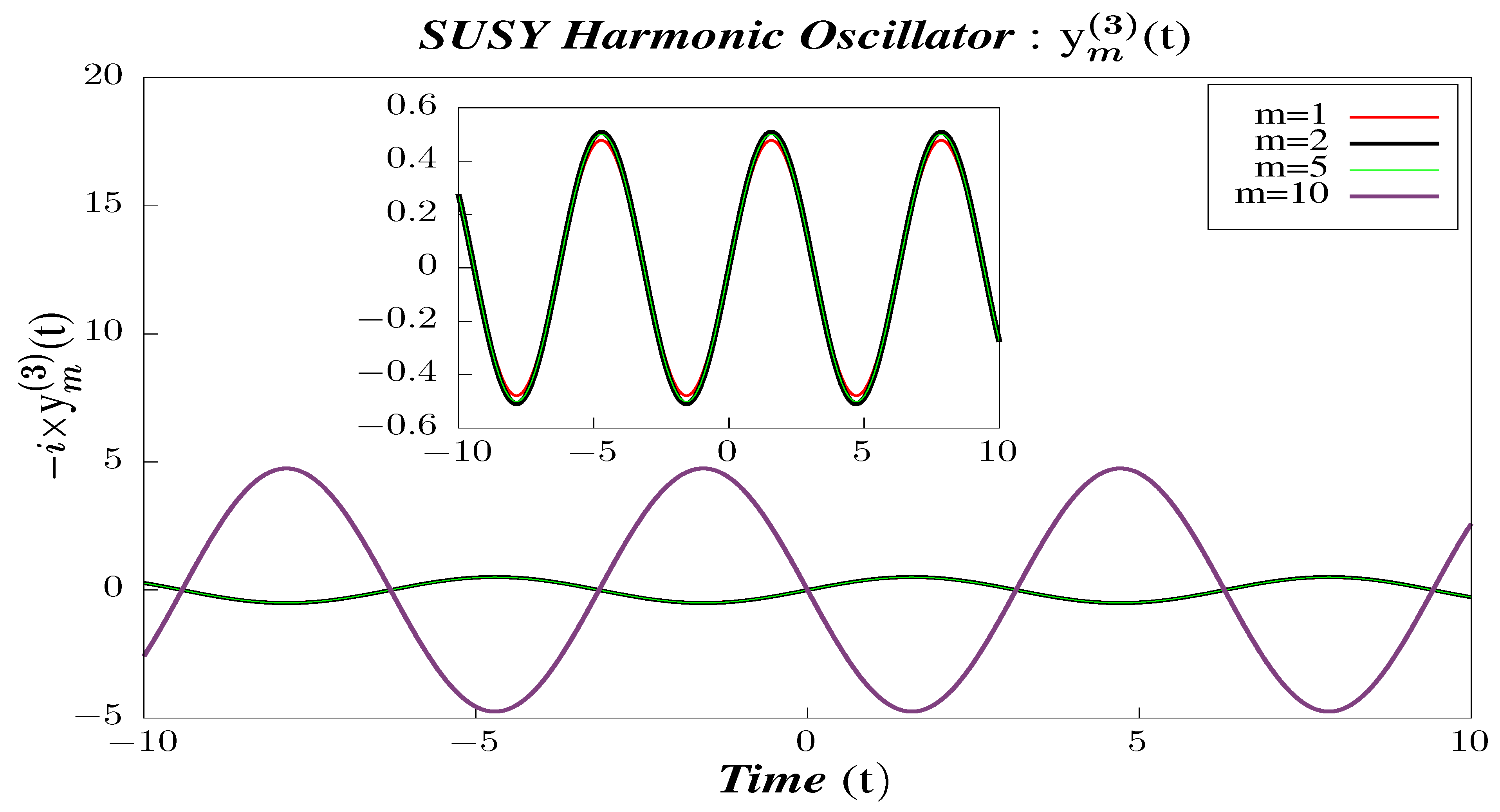

- In Figure 23, Figure 24 and Figure 25, we perform Study A on the 2-point micro-canonical correlators for Supersymmetric 1D Harmonic Oscillator.

- -

- We observe that the correlators are periodic and that their periodicity does not vary with the state.

- -

- The amplitude of the correlator initially increases with increasing m, which can be seen from the greater amplitude for m = 2 than the amplitude for m = 1. However, with further increase of m, the amplitude of the correlator shows negligible change, and the amplitudes of the higher states almost overlap. This suggests that, for the lower energy states, the micro-canonical correlators depend on the energy state in which they are calculated. However, this state dependency goes away when calculated for the higher energy states. This can also be understood from the analytical expression obtained for the micro-canonical correlators obtained in Section 6 (calculated for Harmonic Oscillator of unit mass, i.e., ). The micro-canonical correlators have a non-trivial state dependence in the form of the factor , which reduces simply to 1 for higher energy states.

- -

- In Figure 23, Figure 24 and Figure 25, we have also plotted to draw a contrast of the boundary / truncation state with the other states. The correlators are lacking in feature, sometimes deceptively so, as compared to the other states, which should come as no surprise because we have set our truncation at . Furthermore, this state appears to violate the properties shown by other intermediate states, but, in fact, this is merely an artefact of being the truncation state and that contribution of states with could not be accommodated in the calculations for .

- -

- The correlators largely follow the same patterns and behavior as shown by with two exceptions. First, the amplitude for correlator is amplified, whereas that of is suppressed, as compared to . The order of the amplification of the micro-canonical correlator is exactly twice the amplitude of , which is merely a reflection of the fact that the mass of the oscillator has been chosen as . Similarly, the suppression of is exactly by the same factor. Second is contrasting behavior in the symmetry properties in t, whereas is symmetric in t, and are anti-symmetric.

- -

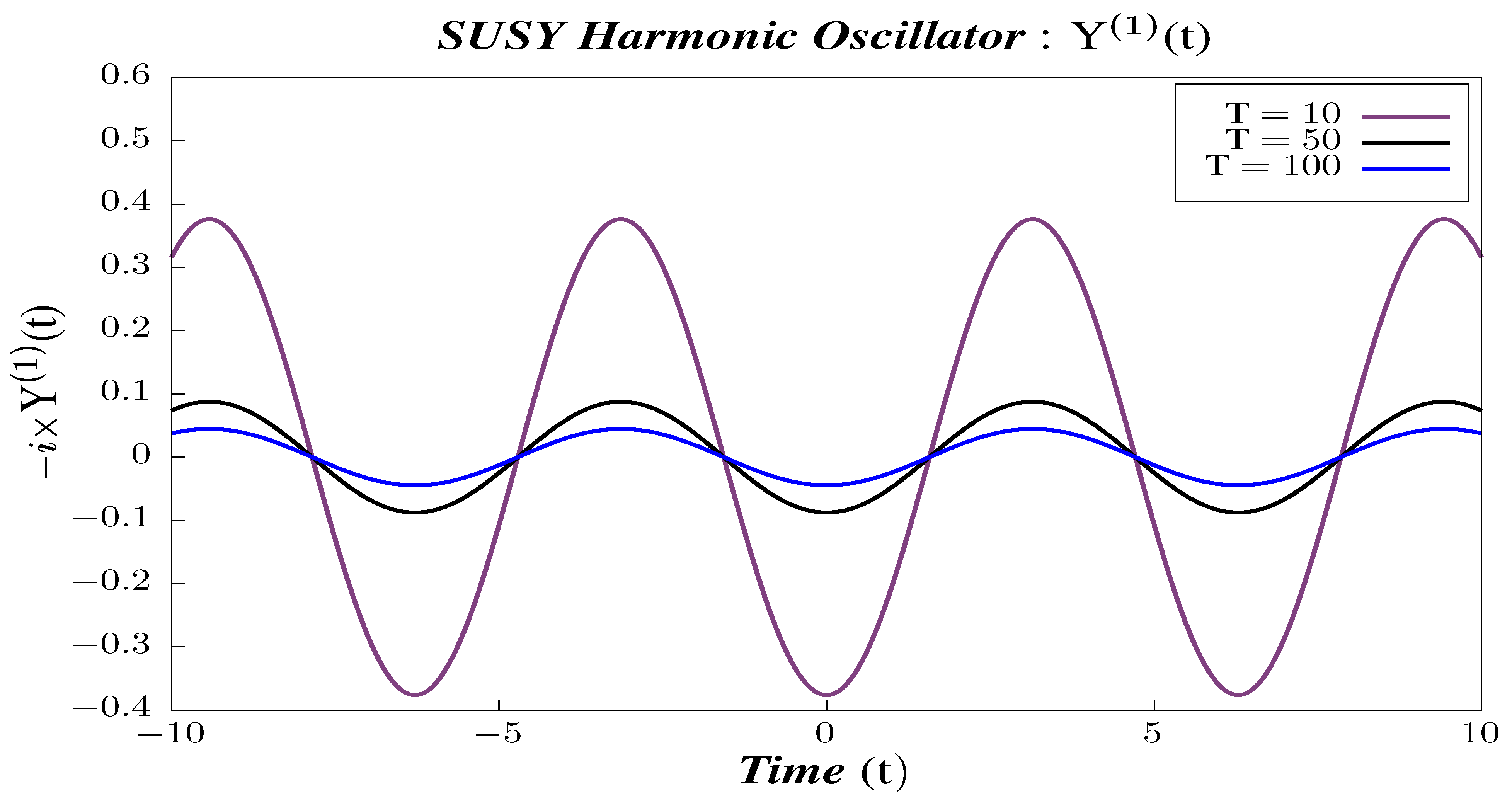

- In Figure 26, Figure 27 and Figure 28, we perform Study B on the 2-point canonical correlators . We observe that the correlators shows periodic behavior for the different chosen values of temperature. We observe that each of the 2-point correlators behave identically with respect to temperature. The amplitude of each of them decreases with increasing temperature. To have a better understanding of the temperature dependence of the 2-point correlators, we plot them with varying temperatures, keeping the time constant.

- -

- In Figure 29, Figure 30 and Figure 31, we present the results of performing Study C on 2-point canonical correlators . Here, we plot , which are the thermal or canonical correlators corresponding to , respectively, with respect to temperature. It is clearly visible that, for very low temperatures, the canonical correlators are constant. After a certain value of the temperature, the amplitude of the correlator shows a gradual increase. It reaches a maximum for a particular value of the temperature and then decays exponentially to zero.

- In Figure 32, Figure 33 and Figure 34, we perform Study A on the 4-point micro-canonical correlators for Supersymmetric Harmonic Oscillator.

- -

- We observe that the correlators are periodic and that their periodicity does not vary with the state. For the correlator , the periodicity is roughly half of the corresponding 2-point micro-canonical correlator.

- -

- Other properties of are much like . We observe a similar change in the amplitude of the correlators with changing m. The scaling of amplitudes in the case of 4-point micro-canonical correlators, and is exactly by a factor of 2 than . This is because, for the 4-point correlators, there is a mass square dependence, unlike the 2-point correlators, which have just mass dependence. The amplitudes of the respective 4-point correlators can also be found to be exactly half of the amplitudes of its 2-point counterpart. This is obvious from the time-dependent functions appearing in the case of Supersymmetric Harmonic oscillator.

- -

- All are symmetric about , which means that, to these 4-point micro-canonical correlators, it does not matter whether or .

- -

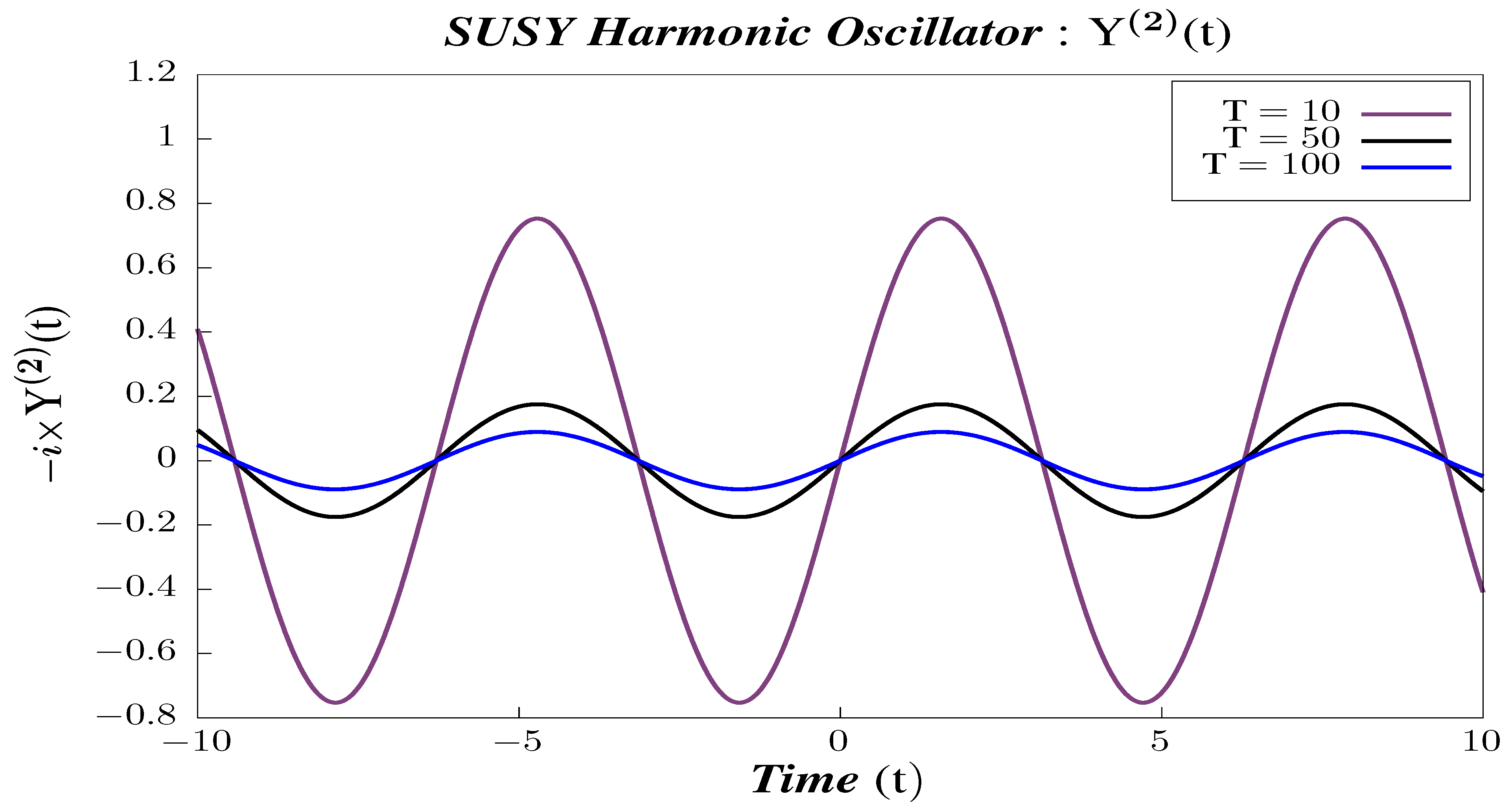

- In Figure 35, Figure 36 and Figure 37, we perform Study B on the 4-point canonical correlators . We observe that the correlators shows periodic behavior for the different chosen values of temperature. We observe that each of the 4-point correlators behaves identically with respect to temperature, which is exactly opposite in character from the 2-point canonical correlators. The amplitude of each of them increases with increasing temperature. To have a better understanding of the temperature dependence of the 4-point correlators, we plot them with varying temperature, keeping the time constant.

- -

- In Figure 38, Figure 39 and Figure 40, we present the results of performing Study C on 4-point canonical correlators . Here, we plot , which are the thermal or canonical correlators corresponding to , respectively, with respect to temperature. It is clearly visible that, for very low temperatures, the 4-point canonical correlators have negligible amplitudes. After a certain value of the temperature, the amplitude of the correlator starts increasing and, finally, saturates to a finite value.

- The temperature-dependent plots shows the significance of computing the 4-point and the 2-point correlators to study the phenomenon of quantum randomness for a Supersymmetric quantum mechanical model. From the plots, it can be seen that, for very low temperatures, the 2-point correlators show a certain finite value, whereas the 4-point correlators are almost negligible. On the other hand, at very high temperatures, the 2-point correlators are almost zero, whereas the 4-point correlators shows certain finite value. This suggests that, to understand quantum randomness for a Supersymmetric model at very low temperature, the results from the 4-point correlators can be misleading, and, similarly, at high temperatures, the 2-point correlators might not be an appropriate quantity to study randomness. However, to understand quantum randomness at the mid temperature range, both 2- and 4-point correlators play a significant role. We feel this shows the necessity for computing the 2-point correlators.

12. Conclusions

- We apply the computational techniques of recently developed methodology of out of time ordered correlators (OTOCs) to study the phenomenon of time disorder averaging for a given quantum statistical ensemble or quantum randomness for two very well known integrable one-dimensional quantum mechanical models viz. Harmonic Oscillator and 1D potential well in the context of one-dimensional Supersymmetric quantum mechanics. We show that, to develop a complete understanding of the underlying randomness in the quantum system, not only the correlators constructed from different operators at different times scales are important but also the correlators, constructed from similar quantum mechanical operators at different time scales, play a pivotal role.

- We have constructed all the temperature independent micro-canonical and temperature-dependent canonical un-normalized and normalized version of these OTOCs in the eigenstate representation of the Supersymmetric time-independent Hamiltonian of the quantum system and represent all of them in a general model-independent way. From the previous study, it is expected that the OTOCs in the eigenstate representation one should not expect any chaotic behavior, i.e., the exponential growth with respect to the time scale in the correlators. However, one can get a broader knowledge of some other aspects of quantum randomness, which might capture the random behavior in the correlators in terms of non-chaoticity. From our analysis, it is expected that a large class of quantum mechanical models will be covered which provide the signature of quantum mechanical randomness, in general.

- The explicit calculation of the 4-point correlator , for the Supersymmetric Harmonic Oscillator, shows the significance of the introduction of Supersymmetry within the context of quantum mechanics compared to the framework of quantum mechanics without having any Supersymmetry. Supersymmetry introduces an energy state dependence on the temperature-independent micro-canonical correlators, which usually does not appear in the framework without having Supersymmetry in the quantum mechanics description. Apart from the dependence on the energy states, the canonical correlators have an additional dependence on temperature, which is also a different and notable feature compared to the results obtained from quantum mechanical set up without having Supersymmetry. This energy state and temperature dependence of the correlators differentiates a Supersymmetric and a Non-Supersymmetric Harmonic oscillator [90], though the time dependence in the OTOCs remains same. In addition, particularly for the Supersymmetric Harmonic Oscillator, we have found that the normalized 4-point OTOCs that are made up of same operators at different time scales show exactly the same behavior, which implies they are not independent of each other. However, this statement might not be true for other integrable models. On the other hand, in the un-normalized version of these two correlators, we have found exact same time dependence, but the overall frequency dependent normalization factors will be different, which implies that they are proportional to each other in this case.

- The classical limit, however, matches with the non-Supersymmetric case apart from a factor of 2, which can be inferred from the fact that, in a Supersymmetric quantum mechanical model, there are two degrees of freedom, one from the original potential and the other associated with the partner potential. The time dependence of the classical and the quantum version of the correlators are exactly identical. However, the temperature dependence observed in the quantum case vanishes for its classical counterpart, which is obviously an important finding from our computation.

- We observe a similar temperature and state dependence on the correlators for the Supersymmetric 1D Infinite potential well. However, it is interesting to note that Reference [90] also observed this state and temperature dependence for Non-Supersymmetric Infinite potential well. The behavior of the only correlator studied in Reference [90] is exactly identical to what we observe for the Supersymmetric case. The correlator showed increase in the amplitude with increasing state number and higher temperatures, which is exactly what we observe here. Hence, we conclude that introduction of Supersymmetry does not introduce new features in the case of 1D Infinite potential well.

- The significance of Supersymmetry in 1D potential well, however, can be realized from its classical counterpart, which is markedly different from what is obtained in the non-Supersymmetric case. The classical limit of OTOC for the 1D non-Supersymmetric infinite potential is well independent of time and is merely a constant, whereas, for the Supersymmetric case, there is a non-trivial time dependence, which is obviously a new finding from our computations.

- In this paper, we restricted ourselves in considering only 2- and 4-point correlation functions to study quantum randomness in various Supersymmetric QM models. However, a more generalized approach would be to consider the multipoint correlation functions to have a better understanding about the randomness underlying the system. We have an immediate plan to carry forward the work along this direction very soon.

- The study of OTOCs can be used to understand quantum randomness in various quantum mechanical models, which are of prime significance in various condensed matter, nuclear, and atomic physics models. Particularly, the time-dependent Hamiltonians we have not studied in this paper are where this eigenstate formalism and related simplification to determine OTOC will not work. In that case, one needs to use the general definition and representation of OTOC in terms of the well known Schwinger Keldysh formalism. We have some future plans on that direction, as well.

- The other types of correlators defined in this paper can be used to study some of the well understood QM models to have an insight on the lost information of quantum randomness. We are very hopeful that incorporating the study of these additional correlators, which we have defined and evaluated in this paper, can make it possible to capture more broader perspective on time disorder averaging phenomena through quantum randomness, rather than only give insight about quantum mechanical chaos from the temporal growth of the correlators.

- Very recently, in Reference [110,111,112,113,114], the authors have studied various relevant measures for an entangled open quantum system. The study of OTOCs for such type of entangled systems [115,116,117,118] will be quite relevant for understanding the rtime disorder averaging phenomena and chaos for such an entangled OQS.

- Last but not least, very recently, we proposed a detailed mechanism and framework, using which one is able to compute the OTOC within the framework of primordial cosmological perturbation theory by making use of the gauge invariant scalar perturbations and its associated canonically conjugate momenta [89], and, finally, found out the chaotic-like behavior in the representative cosmological version of OTOC. However, in that paper, we did not reported anything about the other possible two operators, which we have introduced in this paper. At present, we are working on that direction and very hopeful to get the certain non-trivial features of time disorder averaging, which might have application to explain various cosmologically-relevant phenomena within the evolution history of our universe, which was not explored earlier at all.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Derivation of the Normalization Factors for the Supersymmetric HO

Appendix B. Poisson Bracket Relation for the Supersymmetric Partner Potential Associated with the 1D Infinite Well Potential

Appendix C. Derivation of the Eigenstate Representation of the Correlators

Appendix C.1. Representation of 2-point Correlator: ()

Appendix C.2. Representation of 2-point Correlator: ()

Appendix C.3. Representation of 2-point Correlator: ()

Appendix C.4. Representation of 4-Point Correlator: ()

Appendix C.4.1. Un-normalized: ()

Appendix C.4.2. Un-normalized: ()

Appendix C.5. Representation of 4-point Correlator: ()

Un-Normalized: ()

Appendix C.6. Eigenstate Representation of the Normalization Factors for the 4-point Correlators

References

- Larkin, A.I.; Ovchinnikov, Y.N. Quasiclassical method in the theory of superconductivity. Sov. Phys. JETP 1969, 28, 1200–1205. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, S.; Mukherjee, A.; Chauhan, P.; Bhattacherjee, S. Quantum Out-of-Equilibrium Cosmology. Eur. Phys. J. C 2019, 79, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haehl, F.M.; Loganayagam, R.; Narayan, P.; Rangamani, M. Classification of out-of-time-order correlators. SciPost Phys. 2019, 6, 001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haehl, F.M.; Loganayagam, R.; Narayan, P.; Nizami, A.A.; Rangamani, M. Thermal out-of-time-order correlators, KMS relations, and spectral functions. JHEP 2017, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaudhuri, S.; Loganayagam, R. Probing Out-of-Time-Order Correlators. JHEP 2019, 07, 006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chaudhuri, S.; Chowdhury, C.; Loganayagam, R. Spectral Representation of Thermal OTO Correlators. JHEP 2019, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chakrabarty, B.; Chaudhuri, S.; Loganayagam, R. Out of Time Ordered Quantum Dissipation. JHEP 2019, 7, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gharibyan, H.; Hanada, M.; Swingle, B.; Tezuka, M. A characterization of quantum chaos by 2-point correlation functions.

- Gharibyan, H.; Hanada, M.; Swingle, B.; Tezuka, M. Quantum Lyapunov Spectrum. JHEP 2019, 04, 082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kitaev, A. A simple model of quantum holography. KITP Strings Seminar and Entanglement. 2015, Volume 12. Available online: https://online.kitp.ucsb.edu/online/entangled15/kitaev/ (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Heemskerk, I.; Penedones, J.; Polchinski, J.; Sully, J. Holography from Conformal Field Theory. JHEP 2009, 10, 079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemskerk, I.; Sully, J. More Holography from Conformal Field Theory. JHEP 2010, 09, 099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Czech, B.; Lamprou, L.; McCandlish, S.; Sully, J. Integral Geometry and Holography. JHEP 2015, 10, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anous, T.; Sonner, J. Phases of scrambling in eigenstates. SciPost Phys. 2019, 7, 003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yan, B.; Cincio, L.; Zurek, W.H. Information Scrambling and Loschmidt Echo. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 160603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yoshida, B. Firewalls vs. Scrambling. JHEP 2019, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhuang, Q.; Schuster, T.; Yoshida, B.; Yao, N.Y. Scrambling and Complexity in Phase Space. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 99, 062334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hartmann, J.G.; Murugan, J.; Shock, J.P. Chaos and Scrambling in Quantum Small Worlds. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.04561. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Hartnoll, S.A. Quantum Scrambling and State Dependence of the Butterfly Velocity. SciPost Phys. 2019, 7, 045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Choudhury, S.; Liu, W.V. Fast scrambling without appealing to holographic duality. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.11269. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, S.; Swingle, B. Information scrambling at finite temperature in local quantum systems. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.10814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swingle, B. Unscrambling the physics of out-of-time-order correlators. Nat. Phys. 2018, 14, 988–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibyan, H.; Hanada, M.; Shenker, S.H.; Tezuka, M. Onset of Random Matrix Behavior in Scrambling Systems. JHEP 2018, 7, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shenker, S.H.; Stanford, D. Stringy effects in scrambling. JHEP 2015, 5, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shenker, S.H.; Stanford, D. Black holes and the butterfly effect. JHEP 2014, 3, 067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Addazi, A. Quantum chaos inside Black Holes. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 2017, 32, 1750087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aleiner, I.L.; Faoro, L.; Ioffe, L.B. Microscopic model of quantum butterfly effect: Out-of-time-order correlators and traveling combustion waves. Ann. Phys. 2016, 375, 378–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts, D.A.; Stanford, D. Two-dimensional conformal field theory and the butterfly effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2015, 115, 131603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.J.; Motrunich, O.I. Out-of-time-ordered correlators in a quantum Ising chain. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97, 144304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kukuljan, I.; Grozdanov, S.; Prosen, T. Weak Quantum Chaos. Phys. Rev. B 2017, 96, 060301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, X. Out-of-time-ordered correlators in many-body localized systems. Ann. Phys. 2017, 529, 1600318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syzranov, S.V.; Gorshkov, A.V.; Galitski, V. Out-of-time-order correlators in finite open systems. Phys. Rev. B 2018, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roberts, D.A.; Stanford, D.; Susskind, L. Localized shocks. JHEP 2015, 3, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shenker, S.H.; Stanford, D. Multiple Shocks. JHEP 2014, 12, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stanford, D.; Susskind, L. Complexity and Shock Wave Geometries. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 90, 126007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maldacena, J.; Shenker, S.H.; Stanford, D. A bound on chaos. JHEP 2016, 8, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sachdev, S.; Ye, J. Gapless spin fluid ground state in a random, quantum Heisenberg magnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 70, 3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Maldacena, J.; Stanford, D. Remarks on the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev model. Phys. Rev. D 2016, 94, 106002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fu, W.; Gaiotto, D.; Maldacena, J.; Sachdev, S. Supersymmetric Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev models. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 95, 026009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rosenhaus, V. An introduction to the SYK model. J. Phys. A 2019, 52, 323001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Witten, E. An SYK-Like Model Without Disorder. J. Phys. A 2019, 52, 474002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gross, D.J.; Rosenhaus, V. All point correlation functions in SYK. JHEP 2017, 12, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polchinski, J.; Rosenhaus, V. The Spectrum in the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev Model. JHEP 2016, 4, 001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, Y.; Kitaev, A.; Sachdev, S.; Tarnopolsky, G. Notes on the complex Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev model. JHEP 2020, 2, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Das, S.R.; Ghosh, A.; Jevicki, A.; Suzuki, K. Duality in the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev Model. Springer Proc. Math. Stat. 2017, 255, 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.R.; Ghosh, A.; Jevicki, A.; Suzuki, K. Space-Time in the SYK Model. JHEP 2018, 7, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nosaka, T.; Numasawa, T. Quantum Chaos, Thermodynamics and Black Hole Microstates in the mass deformed SYK model. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.12302. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, S.; Dey, A.; Halder, I.; Janagal, L.; Minwalla, S.; Poojary, R. Notes on melonic O(N)q−1 tensor models. JHEP 2018, 6, 094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klebanov, I.R.; Milekhin, A.; Tarnopolsky, G.; Zhao, W. Spontaneous Breaking of U(1) Symmetry in Coupled Complex SYK Models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.07317. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Liu, J.; Xin, Y.; Zhou, Y. Supersymmetric SYK model and random matrix theory. JHEP 2017, 6, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, E.; Vandoren, S. A new class of SYK-like models with maximal chaos. JHEP 2019, 1, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kobrin, B.; Yang, Z.; Kahanamoku-Meyer, G.D.; Olund, C.T.; Moore, J.E.; Stanford, D.; Yao, N.Y. Many-Body Chaos in the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev Model. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.05725. [Google Scholar]

- Almheiri, A.; Milekhin, A.; Swingle, B. Universal Constraints on Energy Flow and SYK Thermalization. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.04912. [Google Scholar]

- Turiaci, G.; Verlinde, H. Towards a 2d QFT Analog of the SYK Model. JHEP 2017, 10, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurau, R. The complete 1/N expansion of a SYK–like tensor mode. Nucl. Phys. B 2017, 916, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurau, R. Quenched equals annealed at leading order in the colored SYK model. EPL 2017, 119, 30003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurau, R. The ıϵ prescription in the SYK model. J. Phys. Comm. 2018, 2, 015003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti, D.; Carrozza, S.; Gurau, R.; Sfondrini, A. Tensorial Gross-Neveu models. JHEP 2018, 1, 003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benedetti, D.; Gurau, R. 2PI effective action for the SYK model and tensor field theorie. JHEP 2018, 05, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gurau, R. Notes on Tensor Models and Tensor Field Theories. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.03531. [Google Scholar]

- Klebanov, I.R.; Tarnopolsky, G. Uncolored random tensors, melon diagrams, and the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev models. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 95, 046004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klebanov, I.R.; Tarnopolsky, G. On Large N Limit of Symmetric Traceless Tensor Models. JHEP 2017, 10, 037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bulycheva, K.; Klebanov, I.R.; Milekhin, A.; Tarnopolsky, G. Spectra of Operators in Large N Tensor Models. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 97, 026016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giombi, S.; Klebanov, I.R.; Popov, F.; Prakash, S.; Tarnopolsky, G. Prismatic Large N Models for Bosonic Tensors. Phys. Rev. D 2018, 98, 105005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klebanov, I.R.; Popov, F.; Tarnopolsky, G. TASI Lectures on Large N Tensor Models. PoS TASI 2018, 2017, 004. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.; Klebanov, I.R.; Tarnopolsky, G.; Zhao, W. Symmetry Breaking in Coupled SYK or Tensor Models. Phys. Rev. X 2019, 9, 021043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lakshminarayan, A. Out-of-time-ordered correlator in the quantum bakers map and truncated unitary matrices. Phys. Rev. E 2019, 99, 012201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qi, X.L.; Streicher, A. Quantum Epidemiology: Operator Growth, Thermal Effects, and SYK. JHEP 2019, 08, 012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Kim, D.; Kim, D.H. Typical growth behavior of the out-of-time-ordered commutator in many-body localized systems. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 184202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, H.; Gu, Y.; Sachdev, S. Transport and chaos in lattice Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev models. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 045140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romero-Bermúdez, A.; Schalm, K.; Scopelliti, V. Regularization dependence of the OTOC. Which Lyapunov spectrum is the physical one? JHEP 2019, 07, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jahnke, V.; Kim, K.Y.; Yoon, J. On the Chaos Bound in Rotating Black Holes. JHEP 2019, 05, 037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tuziemski, J. Out-of-time-ordered correlation functions in open systems: A Feynman-Vernon influence functional approach. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 100, 062106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rozenbaum, E.B.; Bunimovich, L.A.; Galitski, V. Early-Time Exponential Instabilities in Non-Chaotic Quantum Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 014101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dag, C.B.; Sun, K.; Duan, L.M. Detection of Quantum Phases via Out-of-Time-Order Correlators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 140602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Turiaci, G.J. An Inelastic Bound on Chaos. JHEP 2019, 07, 099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Poojary, R.R. BTZ dynamics and chaos. JHEP 2020, 03, 048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sünderhauf, C.; Piroli, L.; Qi, X.L.; Schuch, N.; Cirac, J.I. Quantum chaos in the Brownian SYK model with large finite N: OTOCs and tripartite information. JHEP 2019, 11, 038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohseninia, R.; Alonso, J.R.G.; Dressel, J. Optimizing measurement strengths for qubit quasiprobabilities behind out-of-time-ordered correlators. Phys. Rev. A 2019, 100, 062336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lian, B.; Sondhi, S.L.; Yang, Z. The chiral SYK model. JHEP 2019, 09, 067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrow, A.W.; Kong, L.; Liu, Z.W.; Mehraban, S.; Shor, P.W. A Separation of Out-of-time-ordered Correlator and Entanglement. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.02219. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, B.B.; Sun, G.; Hwang, M.J. Dynamical Scaling Laws of Out-of-Time-Ordered Correlators. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 195107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergamasco, P.D.; Carlo, G.G.; Rivas, A.M.F. OTOC, complexity and entropy in bi-partite systems. Phys. Rev. Res. 2019, 1, 033044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kitaev, A.; Suh, S.J. Statistical mechanics of a 2-dimensional black hole. JHEP 2019, 05, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gu, Y.; Kitaev, A. On the relation between the magnitude and exponent of OTOCs. JHEP 2019, 02, 075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lunkin, A.V.; Kitaev, A.Y.; Feigel’man, M.V. Perturbed Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev model: A polaron in the hyperbolic plane. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.14535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitaev, A.; Suh, S.J. The soft mode in the Sachdev-Ye-Kitaev model and its gravity dual. JHEP 2018, 5, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murthy, C.; Srednicki, M. Bounds on chaos from the eigenstate thermalization hypothesis. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 123, 230606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choudhury, S. The Cosmological OTOC: Formulating new cosmological micro-canonical correlation functions for random chaotic fluctuations in Out-of-Equilibrium Quantum Statistical Field Theory. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, K.; Murata, K.; Yoshii, R. Out-of-time-order correlators in quantum mechanics. JHEP 2017, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kitaev, A. Hidden correlations in the Hawking radiation and thermal noise. Talk Given at the Fundamental Physics Prize Symposium. 2014, Volume 10. Available online: https://online.kitp.ucsb.edu/online/joint98/kitaev/ (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Choudhury, S.; Mukherjee, A. Quantum randomness in the Sky. Eur. Phys. J. C 2019, 79, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Mukherjee, A. A bound on quantum chaos from Random Matrix Theory with Gaussian Unitary Ensemble. JHEP 2019, 5, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amin, M.A.; Baumann, D. From Wires to Cosmology. JCAP 2016, 2, 045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garcia, M.A.G.; Amin, M.A.; Green, D. Curvature Perturbations From Stochastic Particle Production During Inflation. JCAP 2020, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, M.A.G.; Amin, M.A.; Carlsten, S.G.; Green, D. Stochastic Particle Production in a de Sitter Background. JCAP 2019, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Nandy, P.; Sinha, A. Renormalized Circuit Complexity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 101602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhattacharyya, A.; Shekar, A.; Sinha, A. Circuit complexity in interacting QFTs and RG flows. JHEP 2018, 10, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Susskind, L. Three Lectures on Complexity and Black Holes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Susskind, L. Black Holes and Complexity Classes. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.02175. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A.R.; Susskind, L. Complexity geometry of a single qubit. Phys. Rev. D 2019, 100, 046020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, A.R.; Susskind, L.; Zhao, Y. Quantum Complexity and Negative Curvature. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 95, 045010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cotler, J.; Hunter-Jones, N.; Liu, J.; Yoshida, B. Chaos, Complexity, and Random Matrices. JHEP 2017, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagchi, B. Supersymmetry in Quantum and Classical Mechanics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, F.; Khare, A.; Sukhatme, U. Supersymmetry and quantum mechanics. Phys. Rept. 1995, 251, 267–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khare, A. Supersymmetry in quantum mechanics. AIP Conf. Proc. 2004, 744, 133–165. [Google Scholar]

- Andreas, W. Introduction to Supersymmetry; Lecture Notes; University of Jena: Jena, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wellman, T. An Introduction to Supersymmetry in Quantum Mechanical Systems; Brown University Memorandum; Brown University: Providence, RI, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, A.; Ramadevi, P. Supersymmetry. Reson 2003, 8, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, C.; Loganayagam, R.; Rangamani, M. Open quantum systems and Schwinger-Keldysh holograms. J. High Energy Phys. 2020, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Gupta, N.; Swain, A. QMetrology from QCosmology: Study with Entangled Two Qubit Open Quantum System in De Sitter Space. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.13555. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, S.; Choudhury, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Das, R.N.; Gupta, N.; Panda, S.; Swain, A. Indirect detection of Cosmological Constant from large N entangled open quantum system. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.13058. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, S.; Choudhury, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Goswami, D.; Panda, S.; Swain, A. Open Quantum Entanglement: A study of two atomic system in static patch of de Sitter space. Eur. Phys. J. C 2020, 8, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohra, H.; Choudhury, S.; Chauhan, P.; Mukherjee, A.; Narayan, P.; Panda, S.; Swain, A. Relating the curvature of De Sitter Universe to Open Quantum Lamb Shift Spectroscopy. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.0740. [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury, S.; Panda, S. Quantum entanglement in de Sitter space from stringy axion: An analysis using α vacua. Nucl. Phys. B 2019, 943, 114606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, S.; Panda, S. Entangled de Sitter from stringy axionic Bell pair I: An analysis using Bunch–Davies vacuum. Eur. Phys. J. C 2018, 78, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choudhury, S.; Panda, S.; Singh, R. Bell violation in primordial cosmology. Universe 2017, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Choudhury, S.; Panda, S. Cosmological Spectrum of 2-Point Correlation Function from Vacuum Fluctuation of Stringy Axion Field in De Sitter Space: A Study of the Role of Quantum Entanglement. Universe 2020, 6, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Symbol | Meaning |

|---|---|

| W(x) | Superpotential |

| Hamiltonian of the Supersymmetric Quantum mechanical model. | |

| Eigenstate of the Supersymmetric QM model in the direct sum Hilbert space. | |

| = | Energy difference between the nth and mth energy eigenstate. |

| Microcanonical 2-point correlator of first kind. | |

| Microcanonical 2-point correlator of second kind. | |

| Microcanonical 2-point correlator of third kind. | |

| = | Un-normalized 2-point correlator of first kind. |

| = | Un-normalized 2-point correlator of second kind. |

| = | Un-normalized 2-point correlator of third kind. |

| Microcanonical 4-point correlator of first kind. | |

| Microcanonical 4-point correlator of second kind. | |

| Microcanonical 4-point correlator of third kind. | |

| = | Un-normalized 4-point canonical correlator of first kind. |

| = | Un-normalized 4-point canonical correlator of second kind. |

| = | Un-normalized 4-point canonical correlator of third kind. |

| = | Normalized 2-point correlator of first kind. |

| = | Normalized 2-point correlator of second kind. |

| = | Normalized 2-point correlator of third kind. |

| = | Normalized 4-point correlator of first kind. |

| = | Normalized 4-point correlator of second kind. |

| = | Normalized 4-point correlator of third kind. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bhagat, K.Y.; Bose, B.; Choudhury, S.; Chowdhury, S.; Das, R.N.; Dastider, S.G.; Gupta, N.; Maji, A.; Pasquino, G.D.; Paul, S. The Generalized OTOC from Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics—Study of Random Fluctuations from Eigenstate Representation of Correlation Functions. Symmetry 2021, 13, 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym13010044

Bhagat KY, Bose B, Choudhury S, Chowdhury S, Das RN, Dastider SG, Gupta N, Maji A, Pasquino GD, Paul S. The Generalized OTOC from Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics—Study of Random Fluctuations from Eigenstate Representation of Correlation Functions. Symmetry. 2021; 13(1):44. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym13010044

Chicago/Turabian StyleBhagat, Kaushik Y., Baibhab Bose, Sayantan Choudhury, Satyaki Chowdhury, Rathindra N. Das, Saptarshhi G. Dastider, Nitin Gupta, Archana Maji, Gabriel D. Pasquino, and Swaraj Paul. 2021. "The Generalized OTOC from Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics—Study of Random Fluctuations from Eigenstate Representation of Correlation Functions" Symmetry 13, no. 1: 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym13010044

APA StyleBhagat, K. Y., Bose, B., Choudhury, S., Chowdhury, S., Das, R. N., Dastider, S. G., Gupta, N., Maji, A., Pasquino, G. D., & Paul, S. (2021). The Generalized OTOC from Supersymmetric Quantum Mechanics—Study of Random Fluctuations from Eigenstate Representation of Correlation Functions. Symmetry, 13(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.3390/sym13010044