Metal Exchangeability in the REE-Enriched Biogenic Mn Oxide Birnessite from Ytterby, Sweden

Abstract

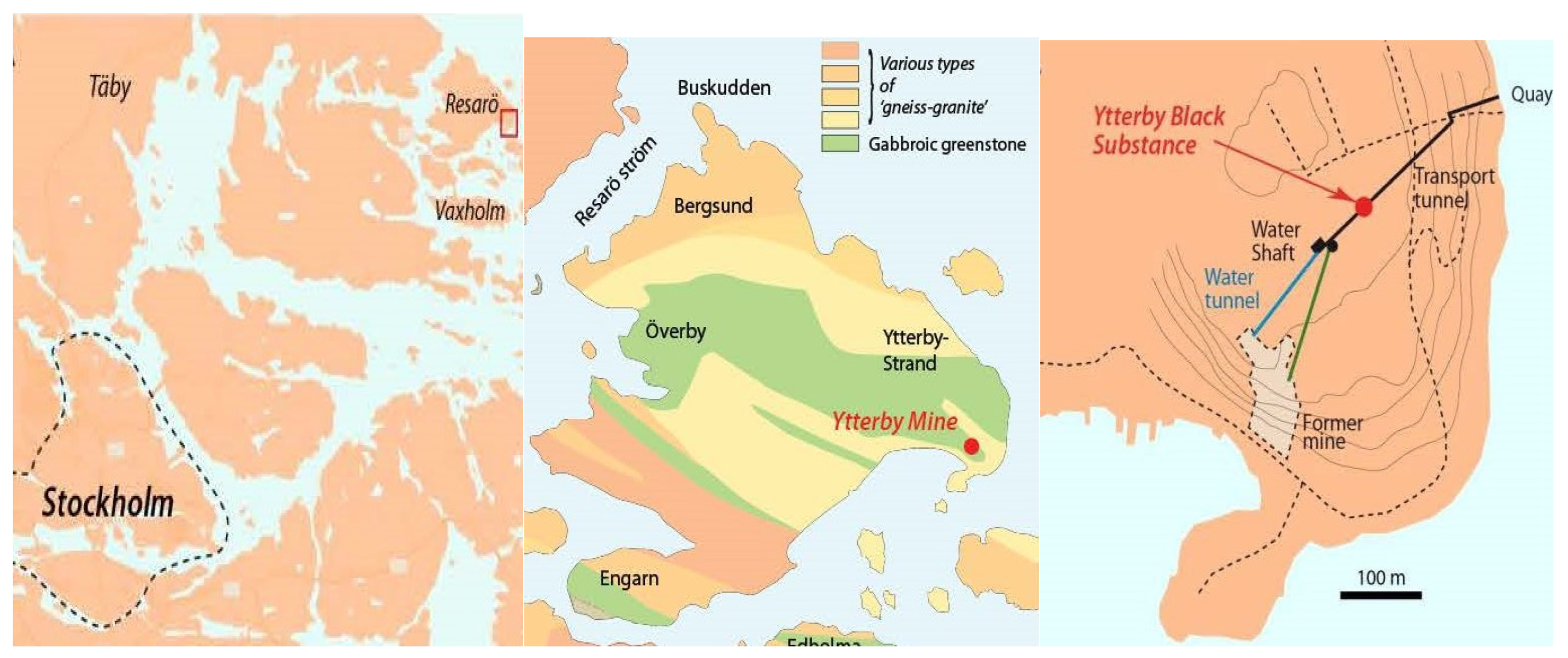

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

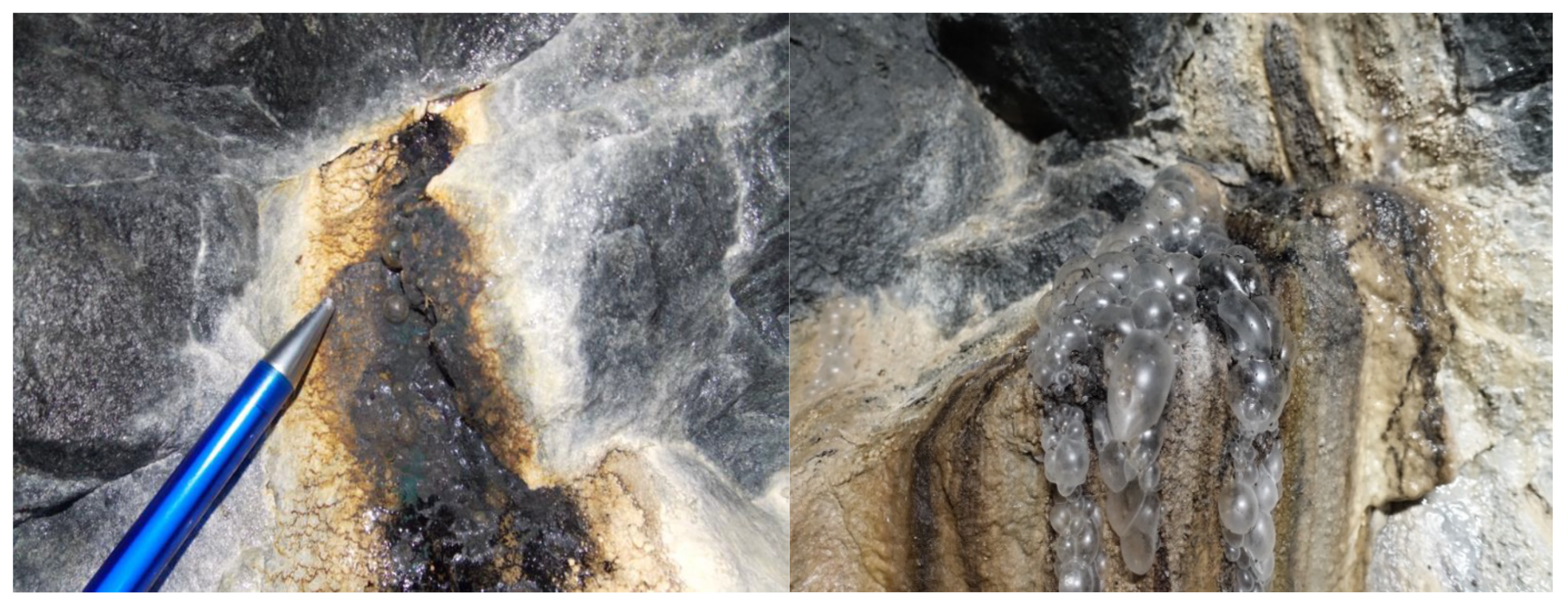

2.1. Sampling of YBS and Fracture Water

2.2. Characterization and Analysis of YBS

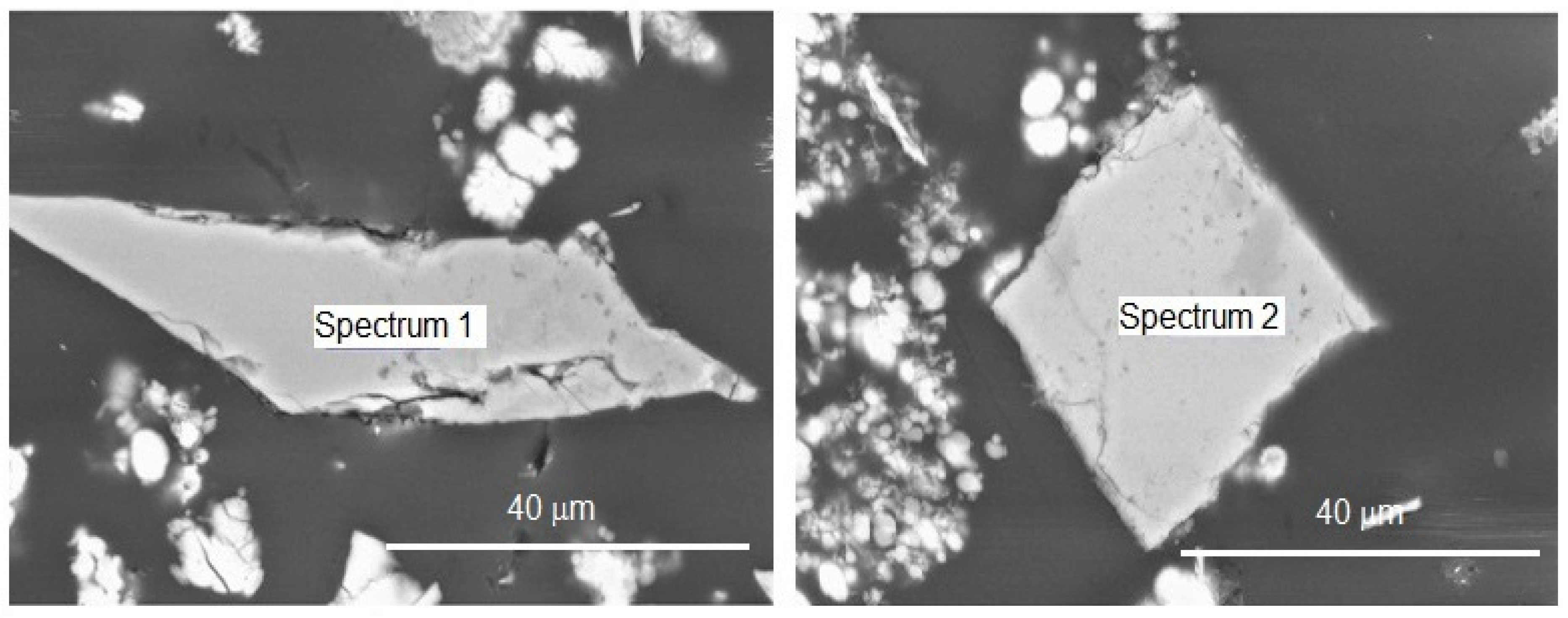

2.2.1. Environmental Scanning Electron Microscopy (ESEM-EDS)

2.2.2. Sequential Washing

- C1 Organics, dichloromethane/methanol (CH2Cl2/CH3OH) 1:1; 2 times

- C2 Exchangeable ions, 0.11 M acetic acid (CH3COOH, HAc), pH 4.2

- C3 Suspended colloids, deionized water (18.2 MΩ); 3 times

2.2.3. Element Exchange

2.2.4. X-ray Diffractometry

2.2.5. IR Spectroscopy

2.2.6. Element Analysis

2.3. Analysis of Water

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Environmental Scanning Electron Microscopy (ESEM-EDS)

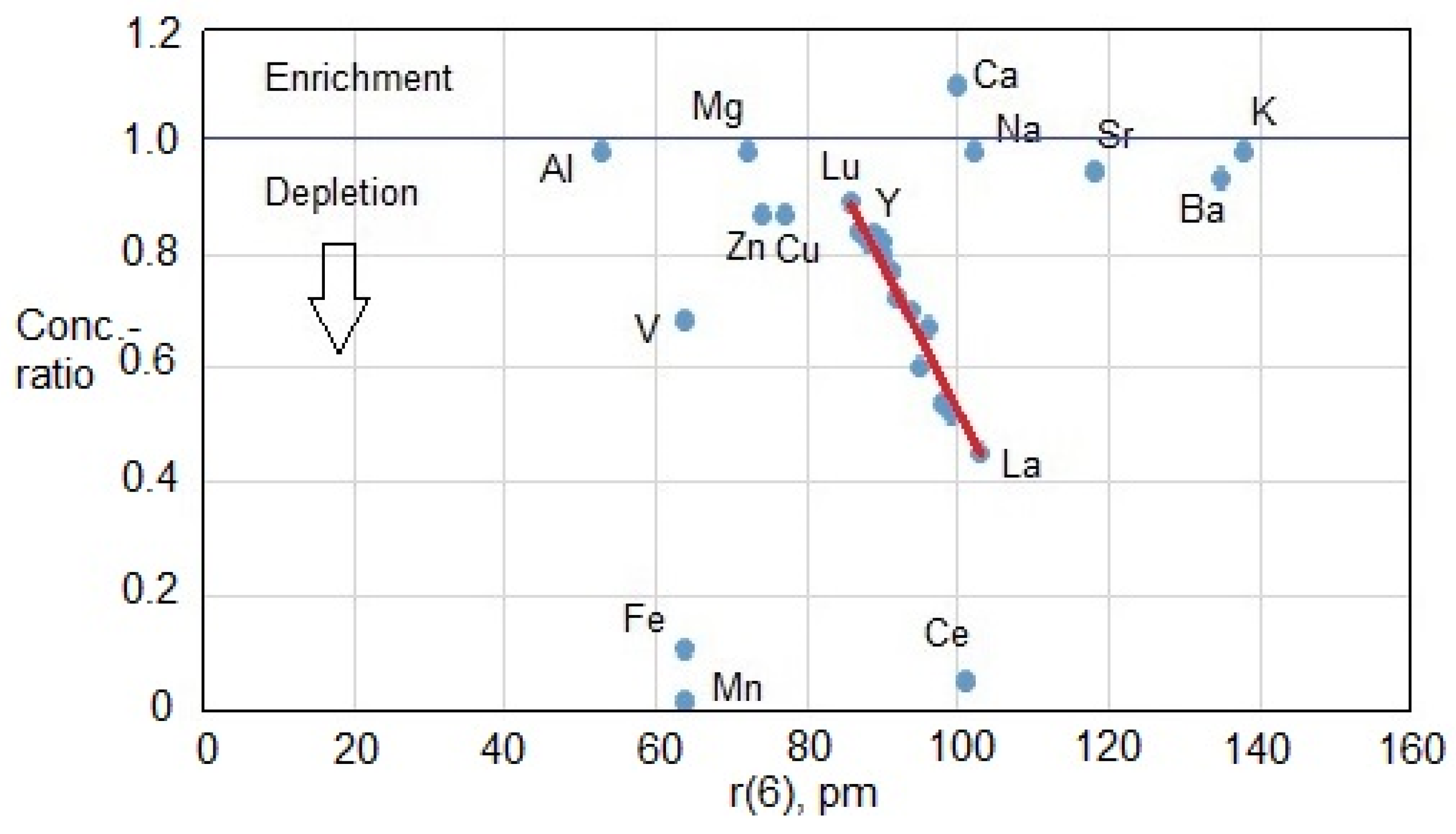

3.2. Fracture Water Chemistry and YBS Metal Enrichment

3.3. Phase Analysis

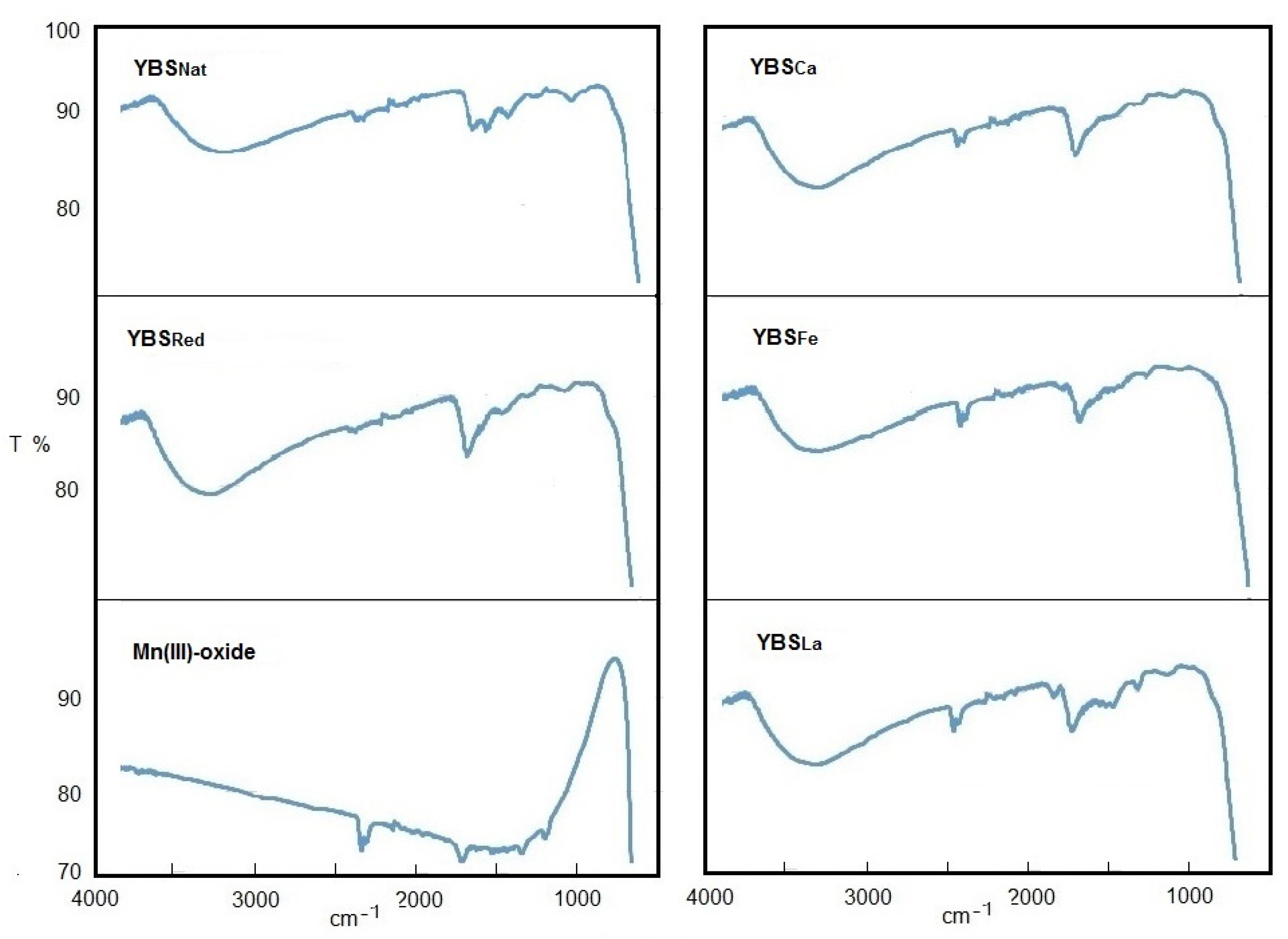

3.4. Infrared Spectroscopy

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sjöberg, S.; Allard, B.; Rattray, J.E.; Callac, N.; Grawunder, A.; Ivarsson, M.; Sjöberg, V.; Karlsson, S.; Skelton, A.; Dupraz, C. Rare earth element enriched birnessite in water-bearing fractures, the Ytterby mine, Sweden. Appl. Geochem. 2017, 78, 158–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordenskjöld, I. Der Pegmaitite von Ytterby. Bull. Geol. Inst. Univ. Uppsala 1910, IX, 1908–1909. [Google Scholar]

- Sundius, N. Description of the Bedrock Map of the Stockholm Region; Sveriges Geologiska Undersökning, Ser. Ba No: 13, Kungl. Boktryckeriet. P.A; Norstedt & Söner: Stockholm, Sweden, 1948. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Ralph, J.; Zhang, J.; Que, X.; Prabhu, A.; Morrison, S.M.; Hazen, R.M.; Wyborn, L.; Lehnert, K. OpenMindat: Open and FAIR mineralogy data from the Mindat database. Geosci. Data J. 2023, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L.H.P.; Milne, A.A. Birnessite, a new manganese oxide mineral from Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Miner. Mag. 1956, 31, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, E.D. Characterization of a marine birnessite. Am. Mineral. 1977, 62, 278–285. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, R.M.; Rossman, G.R. The tetravalent manganese oxides: Identification, hydration, and structural relationships by infrared spectroscopy. Am. Mineral. 1979, 64, 1199–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Drits, V.A.; Silvester, E.; Gorshkov, A.I.; Manceau, A. Structure of synthetic monoclinic Na-rich birnessite and hexagonal birnessite: I. Results from X-ray diffraction and selected-area electron diffraction. Am. Miner. 1997, 82, 946–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebo, B.M.; Bargar, J.R.; Clement, B.G.; Dick, G.J.; Murray, K.J.; Parker, D.; Verity, R.; Webb, S.M. Biogene manganese oxides: Properties and mechanisms of formation. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet Sci. 2004, 32, 287–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villalobos, M.; Lanson, B.; Manceau, A.; Toner, B.; Sposito, G. Structural model for biogenic Mn oxide produced by Pseudomonas putida. Am. Mineral. 2006, 91, 489–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bargar, J.R.; Fuller, C.C.; Marcus, M.A.; Brearley, A.J.; De la Rosa, M.P.; Webb, S.M.; Caldwell, W.A. Structural characterization of terrestrial microbial Mn oxides from Pinal Creek, AZ. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 889–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dick, G.J.; Clement, B.G.; Webb, S.M.; Fodrie, F.J.; Bargar, J.R.; Tebo, B.M. Enzymatic microbial Mn(II) oxidation and Mn biooxide production in the Guyamas Basin deep-sea hydrothermal plume. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 6517–6530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, J.; Kwon, K.D.; Refson, K.; Bargar, J.R.; Sposito, G. Mechanisms of nickel sorption by a bacteriogenic birnessite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 3076–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spiro, T.G.; Bargar, J.R.; Sposito, G.; Tebo, B.M. Bacteriogenic manganese oxides. Accounts Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 2–9. [Google Scholar]

- Santelli, C.M.; Webb, S.M.; Dohnalkova, A.C.; Hansel, C.M. Diversity of Mn oxides produces by Mn(II)-oxidizing fungi. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2011, 75, 2762–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, S.; Gutierrez, L.; Fontaine, C.; Croue, J.-P.; Gallard, H. Organic matter interactions with natural manganese oxide and synthetic birnessite. Sci. Totel Environ. 2017, 583, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, J.E.; Veblen, D.R. Crystal structure determinations of synthetic sodium, magnesium, and potassium birnessite using TEM and the Rietveld method. Am. Miner. 1990, 75, 477–489. [Google Scholar]

- Drits, V.A.; Lanson, B.; Gorshkov, A.I.; Manceau, A. Substructure and superstructure of four-layer Ca-exchanged birnessite. Am. Mineral. 1998, 83, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Silvester EManceau, A.; Drits, V.A. Structure of synthetic Na-rich birnessite and hexagonal birnessite: II. Results from chemical studies and EXAFS spectroscopy. Am. Mineral. 1997, 82, 962–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelo, C.A.J.; Postma, D. A consistent model for surface complexation on birnessite (–MnO2) and its application to a column experiment. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1999, 63, 3039–3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lanson, B.; Drits, V.A.; Feng, Q.; Manceau, A. Structure of triclinic Na-rich birnessite. Acta Cryst. 2000, A56, 366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lanson, B.; Drits, V.A.; Gaillot, A.C.; Silvester, E.J.; Plancon, A.; Manceau, A. Structure of heavy-metal sorbed birnessite: Part 1. Results from X-ray diffraction. Am. Mineral. 2002, 87, 1631–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Drits, V.A.; Lanson, B.; Bougerol-Chaillout, C.; Gorshkov, A.I.; Manceau, A. Structure of heavy-metal sorbed birnessite. Part 2: Results from electron diffraction. Am. Mineral. Soc. Am. 2002, 87, 1646–1661. [Google Scholar]

- Post, J.E.; Heaney, P.J.; Hanson, J. Rietveld refinement of a triclinic structure for synthetic Na-birnessite using synchrotron powder diffraction data. Powder Diffract. 2002, 17, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillot, A.-C.; Flot, D.; Drits, V.A.; Manceau, A.; Burghammer, M.; Lanson, B. Structure of synthetic K-rich birnessite obtained by high-temperature decomposition of KMnO4. I. Two-layer polytype from 800C experiment. Chem. Mater. 2003, 15, 4666–4678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Villalobos, M.; Toner, B.; Bargar, J.; Sposito, G. Characterization of the manganese oxide produced by Pseudomonas putida strain MnB1. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2003, 67, 2649–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davranche, M.; Pourret, O.; Gruau, G.; Dia, A.; Le Coz-Bouhnik Caren, M. Adsorption of REE(III)-humate complexes onto MnO2: Experimental evidence for cerium anomaly and lanthanide tetrad effect suppression. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2005, 69, 4825–4834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.H.; Tan, W.F.; Liu, F.; Huang, Q.; Liu, X. Pathways of birnessite formation in alkali medium. Sci. China Ser. D Earth Sci. 2005, 48, 1438–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davranche, M.; Pourret, O.; Gruau, G.; Dia, A.; Jin, D.; Gaertner, D. Competitive binding of REE to humic acid and manganese oxide: Impact of reaction kinetics on development of cerium anomaly and REE adsorption. Chem. Geol. 2008, 247, 154–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.A.; Post, J.E. Water in the interlayer region of birnessite: Importance in cation exchange and structural stability. Am. Mineral. 2006, 91, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopano, C.L.; Heaney, P.J.; Post, J.E.; Hanson, J.; Komarneni, S. Time-resolved structural analysis of K- and Ba-exchange reactions with synthetic Na-birnessite using synchrotron X-ray diffraction. Am. Miner. 2007, 97, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopano, C.L.; Heaney, P.J.; Post, J. Cs-exchange in birnessite: Reaction mechanisms inferred from time-resolved X-ray diffraction and transmission electron microscopy. Am. Mineral. 2009, 94, 816–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.C.; Ju, J.H.; Kiim, S.S.; Baik, M.H.; Rhee, S.W. Sorption of aqueous Pb2+ ion on synthetic manganese oxides-intercalated with exchangeable cations. J. Industr. Eng. Chem. 2011, 17, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cygan, R.T.; Post, J.E.; Heaney, P.J.; Kubick, J.D. Molecular models of birnessite and related hydrated layered minerals. Amer. Mineral. 2012, 97, 1505–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, X.; Villalobos, M.; Tan, W.; Liu, F. Sorption behaviour of heavy metals on birnessite: Relationship with its Mn average oxidation state and implications for types of sorption sites. Chem. Geol. 2012, 292–293, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Tan, W.; Zheng, L.; Cui, H.; Qiu, G.; Liu, F.; Feng, X. Characterization of Ni-rich hexagonal birnessite and its geochemical effects on aqueous Pb2+/Zn2+ and As(III). Geochim. Cosmichim. Acta 2012, 93, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Liu, F.; Feng, X.; Hu, T.; Zheng, L.; Qui, G.; Koopal, L.K.; Tan, W. Effects of Fe doping on the structures and properties of hexagonal birnessites—Comparison with Co and Ni doping. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2013, 117, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumaiza, H.; Coustel, R.; Medjahdi, G.; Ruby, C.; Bergaoui, L. Conditions for the formation of pure birnessite during the oxidation of Mn(II) cations in aqueous alkaline medium. J. Solid State Chem. 2017, 248, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.B.; Vito, C.; Scheetz, E. The mineralogy and trace element chemistry of black manganese oxide deposits from caves. J. Cave Karst Studies 2009, 71, 136–143. [Google Scholar]

- Frierdich, A.J.; Hasenmueller, E.A.; Catalano, J.G. Composition and structure of nanocrystalline Fe and Mn oxide cave deposits: Implications for trace element mobility in karst systems. Chem. Geol. 2011, 284, 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.Z.; Dionisio, A.; Sequeira Braga, M.A.; Hernandez-Mariné, M.; Afonso, M.J.; Muralha, V.S.F.; Herrera, L.K.; Raabe, J.; Fernandez-Cortes, A.; Cuezva, S.; et al. Biogenic Mn oxide minerals coating in a subsurface granite environment. Chem. Geol. 2012, 322–323, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sjöberg, S. Microbially Mediated Manganese Oxides Enriched in Yttrium and Rare Earth Elements in the Ytterby Mine. Ph.D. Thesis, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sjöberg, S.; Callac, N.; Allard, B.; Smittenberg, R.H.; Dupraz, C. Microbial communities inhabiting a rare earth element enriched birnessite-type manganese deposit in the Ytterby mine, Sweden. Geomicrobiol. J. 2018, 35, 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sjöberg, S.; Stairs, C.; Allard, B.; Hallberg, R.; Homa, F.; Martin, T.; Ettema, T.J.G.; Dupraz, C. Bubble biofilm: Bacterial colonization of air-air interface. Biofilm 2020, 2, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöberg, S.; Stairs, C.; Allard, B.; Homa, F.; Martin, T.; Sjöberg, V.; Ettema, T.J.G.; Dupraz, C. Microbiomes in a manganese oxide producing ecosystem in the Ytterby mine, Sweden: Impact on metal mobility. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjöberg, S.; Yu, C.; Stairs, C.W.; Allard, B.; Hallberg, R.; Henriksson, S.; Åström, M.; Dupraz, C. Microbe-Mediated Mn Oxidation—A Proposed Model of Mineral Formation. Minerals 2021, 11, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylward, G.; Findlay, T. SI Chemical Data, 5th ed.; John Wiley and Sons: Melbourne, Australia, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bau, M.; Koschinsky, A. Oxdative scavenging of cerium on hydrous Fe oxide: Evidence from the distribution of rare earth elements and yttrium between Fe oxides and Mn oxides in hydrogenetic ferromanganese crusts. Chem. Geol. 2009, 43, 37–47. [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo, E.H.; Wen, X. The influence of redox reactions on the uptake of dissolved Ce by suspended Fe and Mn oxide particles. Aquat. Geochem. 1998, 3, 357–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, A.; Kawabe, I. REE(III) adsorption onto Mn dioxide (δ-MnO2) and Fe oxyhydroxide: Ce(III) oxidation by δ-MnO2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2001, 65, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Tani, Y.; Takahashi, Y.; Tanimizu, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Kozai, N.; Ohnuki, T. A specific Ce oxidation process during sorption of rare earth elements on biogenic Mn oxide produced by Acremonium sp. Strain KR21-2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2010, 74, 5463–5477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loges, A.; Wagner, T.; Barth, M.; Bau, M.; Göb, S.; MArkl, G. Negative Ce anomaliesin Mn oxides: The role of Ce4+ mobility during water-mineral nteraction. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2012, 86, 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnuki, T.; Jiang, M.; Sakamoto, F.; Kozai, N.; Yamasaki, S.; Yu, Q.; Tanaka, K.; Utsumomiya, S.; Xia, X.; Yang, K.; et al. Sorption of trivalent cerium by a mixture of microbial cells and manganese oxides: Effect of microbial cells on the oxidation of trivalent cerium. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2015, 163, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, D.; Tepe, N.; Pourret, O.; Bau, M. Negative cerium anomalies in manganese (hydr)oxide precipitates due to cerium oxidation in the presence of dissolved siderophores. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 196, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allard, B.; Karlsson, M.; Tullborg, E.-L.; Larson, S.Å. Ion Exchange Capacities and Surface Areas of Some Major Components and Common Fracture Filling Materials of Igneous Rocks; SKBF Technical Report 83-64; Swedish Nuclear Fuel Supply Co/Division KBS: Stockholm, Sweden, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Francis, C.W.; Grigal, D.F. A rapid and simple procedure using Sr85 for determining cation exchange capacities of soils and clays. Soil. Sci. 1971, 112, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Liao, Q.; Linghu, W.; Huang, Y.; Shen, R.; Alsaedi, A.; Wang, J.; Hayar, Y.T.; Sheng, G. Application of EXAFS with a bent crystal analyzer to study the pH-dependent microstructure of Eu(III) onto birnessite. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, K.D.; Refson, K.; Sposito, G. Understanding the trends in transition in transition metal sorption by vacancy sites in birnessite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2013, 101, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saratovsky, I.; Wightman, P.G.; Pasten, P.A.; Gaillard, J.-F.; Poeppelmeier, K.R. Manganese oxides: Parallells between abiotic and biotic structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 11188–11198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saratovsky, I.; Gurr, S.J.; Hayward, M.A. The structure of manganese oxide formed by the fungus Acremonium sp. Strain KR21-2. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2009, 73, 3291–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Sasaki, K.; Tanaka, K.; Ohnuki, T.; Hirajima, T. Structural factors of biogenic birnessite produced by fungus Paraconiothyrium sp. WL-2 strain affecting sorption of Co2+. Chem. Geol. 2012, 310–311, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Sasaki, K.; Tanaka, K.; Ohnuki, T.; Hirajima, T. Zinc sorption during bio-oxidation and precipitation of manganese modifies the layer stacking of biogenic birnessite. Geomicrobiol. J. 2013, 30, 829–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayanna, S.; Peacock, C.L.; Schaffner, F.; Grawunder, A.; Merten, D.; Kothe, E.; Buchel, G. Biogenic precipitation of manganese oxides and enrichment of heavy metals at acidic soil pH. Chem. Geol. 2015, 402, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, D.C.; Chen, C.C.; Dixon, J.B. Transformation of birnessite to buserite, todorokite, and manganite under mild hydrothermal treatment. Clays Clay Minerals 1987, 35, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Huang, A.; Park, S.H.; Suib, S.L.; O’Young, C.-L. Crystallization of sodium-birnessite and accompanied phase transformation. Chem. Mater. 1998, 10, 1561–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.S.; Wang, M.K. Synthesis and characterization of well-crystallized birnessite. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 2589–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novikov, G.V.; Kulikova, L.N.; Bogdanova, O.Y.; Sychkova, G.I. Layered hydrous manganese dioxide saturated with alkaline-earth cations: Synthesis and sorption properties. Russ. J. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 51, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Zhang, M.; Liu, Z.-H.; Ooi, K. IR spectra of manganese oxides with either layered or tunnel structures. Spectrochim. Acta 2007, A67, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, E.; Gumus, H.; Sarihan, A. Synthesis, structural characterization and Pb(II) adsorption behaviour of K- and H-birnessite samples. Desalination 2011, 279, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Liu, F.; Feng, X.; Liu, M.; Tan, W.; Qiu, G. Co2+-exchange mechanism of birnessite and its application for the removal of Pb2+ and As(III). J. Hazardous Mater. 2011, 196, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, A.L.; Shaw, S.; Peacock, C.L. Nucleation and growth of todorokite from birnessite: Implications for trace metal cycling in marine sediments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 144, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, H.; Kwon, K.D.; Lee, J.-Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, X.; Liu, F.; Zhang, J.; Feng, X. Distinct effects of Al3+ doping on the structure and properties of hexagonal turbostratic birnessite: A comparison with Fe3+ doping. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2017, 208, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Element | YBSNat mg/kg | AqA μg/L | AqB μg/L | [AqB]/[AqA] | log ke L/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 8.31 | 8.33 | |||

| Cl− | 20,900 | 20,700 | 0.99 | ||

| SO42− | 29,100 | 35,000 | 1.20 | ||

| HCO3− | 205,000 | 228,000 | 1.11 | ||

| Mn(III,IV) | 452,710 | 172 | 2.72 | 0.016 | 6.42 |

| M(I) | |||||

| Na | 399 | 24,510 | 24,080 | 0.98 | 1.21 |

| K | 666 | 1720 | 1690 | 0.98 | 2.59 |

| M(II) | |||||

| Ca | 64,170 | 56,360 | 61,740 | 1.09 | 3.06 |

| Mg | 4075 | 8340 | 8140 | 0.98 | 2.69 |

| Ba | 1765 | 4.50 | 4.17 | 0.93 | 5.59 |

| Cu | 1555 | 3.89 | 3.40 | 0.87 | 5.60 |

| Sr | 639 | 250 | 237 | 0.95 | 3.41 |

| Zn | 276 | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.87 | 5.57 |

| M(III) | |||||

| Y | 1357 | 5.00 | 4.08 | 0.82 | 5.43 |

| Al | 841 | 5.26 | 5.14 | 0.98 | 5.20 |

| V | 683 | 2.68 | 1.82 | 0.68 | 5.41 |

| Fe | 583 | 0.40 | 0.044 | 0.11 | 6.16 |

| REE | |||||

| Ce | 3180 | 1.15 | 0.059 | 0.051 | 6.44 |

| La | 1825 | 1.04 | 0.47 | 0.45 | 6.24 |

| Nd | 1785 | 1.27 | 0.69 | 0.54 | 6.14 |

| Gd | 419 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.70 | 5.98 |

| Pr | 418 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 6.22 |

| Sm | 375 | 0.27 | 0.18 | 0.67 | 6.14 |

| Dy | 308 | 0.43 | 0.33 | 0.77 | 5.85 |

| Er | 150 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.83 | 5.63 |

| Yb | 99 | 0.31 | 0.26 | 0.84 | 5.50 |

| Ho | 60 | 0.11 | 0.088 | 0.80 | 5.74 |

| Tb | 56 | 0.061 | 0.044 | 0.72 | 5.96 |

| Eu | 31 | 0.025 | 0.015 | 0.60 | 6.09 |

| Tm | 18 | 0.049 | 0.040 | 0.82 | 5.57 |

| Lu | 15 | 0.055 | 0.049 | 0.89 | 5.46 |

| Element | YBSNat mg/kg | YBSRed mg/kg | YBSNa mg/kg | YBSCa mg/kg | YBSLa mg/kg | YBSFe mg/kg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn(III,IV) | 452,710 | 528,230 | 507,030 | 486,120 | 537,290 | 483,340 |

| M(I) | ||||||

| Na | 399 | 1823 | 19,265 | 73 | 69 | 84 |

| K | 666 | 1310 | 1109 | 1255 | 437 | 372 |

| M(II) | ||||||

| Ca | 64,170 | 57,930 | 68,067 | 104,270 | 10,723 | 8640 |

| Mg | 4075 | 2442 | 1826 | 1405 | 1250 | 700 |

| Ba | 1765 | 1959 | 1856 | 1817 | 2199 | 1250 |

| Cu | 1555 | 1838 | 1716 | 1652 | 1727 | 1035 |

| Sr | 639 | 707 | 627 | 504 | 178 | 45 |

| Zn | 276 | 237 | 224 | 204 | 232 | 81 |

| M(III) | ||||||

| Y | 1357 | 1515 | 1430 | 1350 | 909 | 372 |

| Al | 841 | 850 | 1208 | 925 | 693 | 532 |

| V | 683 | 664 | 627 | 591 | 630 | 605 |

| Fe | 583 | 666 | 1424 | 707 | 533 | 95,931 |

| REE | ||||||

| Ce | 3180 | 3121 | 2946 | 2785 | 2928 | 2203 |

| La | 1825 | 1634 | 1549 | 1474 | 124,315 | 497 |

| Nd | 1785 | 1685 | 1592 | 1499 | 984 | 516 |

| Gd | 419 | 419 | 394 | 377 | 291 | 137 |

| Pr | 418 | 403 | 383 | 363 | 220 | 122 |

| Sm | 375 | 369 | 347 | 329 | 239 | 121 |

| Dy | 308 | 335 | 329 | 303 | 230 | 103 |

| Er | 150 | 171 | 162 | 155 | 118 | 51 |

| Yb | 99 | 116 | 110 | 106 | 90 | 38 |

| Ho | 60 | 65 | 61 | 58 | 45 | 20 |

| Tb | 56 | 65 | 60 | 60 | 42 | 19 |

| Eu | 31 | 31 | 30 | 28 | 20 | 10 |

| Tm | 18 | 21 | 20 | 19 | 16 | 7 |

| Lu | 15 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 13 | 6 |

| Element | YBSNat x | YBSRed x | YBSNa x | YBSCa x | YBSLa x | YBSFe x | r(6) pm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn(III,IV) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 64, 46 |

| M(I) | |||||||

| Na | 0.004 | 0.016 | 0.182 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 102 |

| K | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.002 | 138 |

| M(II) | |||||||

| Ca | 0.388 | 0.301 | 0.368 | 0.588 | 0.179 | 0.049 | 100 |

| Mg | 0.040 | 0.021 | 0.016 | 0.013 | 0.012 | 0.007 | 72 |

| Ba | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 135 |

| Cu | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.004 | 73 |

| Sr | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 118 |

| Zn | 0.001 | <0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | 74 |

| M(III) | |||||||

| Y | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 90 |

| Al | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.010 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 53 |

| V | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.003 | 64, 59 a |

| Fe | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.391 | 64, 78 b |

| REE | |||||||

| Ce | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 101, 87 c |

| La | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.183 | 0.001 | 103 |

| Nd | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 98 |

| Gd | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 94 |

| Pr | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 99 |

| Sm | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 96 |

| Element M | YBSNat x | YBSRed x | YBSNa x | YBSCa x | YBSLa x | YBSFe x |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | 0.02 | 0.18 | ||||

| Ca | 0.39 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.59 | 0.18 | 0.05 |

| Mg | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Fe | 0.01 | 0.39 | ||||

| REE + Y | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.19 | 0.01 |

| ΣOthers, x < 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Σx | 0.48 | 0.39 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.41 | 0.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allard, B.; Sjöberg, S.; Sjöberg, V.; Skogby, H.; Karlsson, S. Metal Exchangeability in the REE-Enriched Biogenic Mn Oxide Birnessite from Ytterby, Sweden. Minerals 2023, 13, 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/min13081023

Allard B, Sjöberg S, Sjöberg V, Skogby H, Karlsson S. Metal Exchangeability in the REE-Enriched Biogenic Mn Oxide Birnessite from Ytterby, Sweden. Minerals. 2023; 13(8):1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/min13081023

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllard, Bert, Susanne Sjöberg, Viktor Sjöberg, Henrik Skogby, and Stefan Karlsson. 2023. "Metal Exchangeability in the REE-Enriched Biogenic Mn Oxide Birnessite from Ytterby, Sweden" Minerals 13, no. 8: 1023. https://doi.org/10.3390/min13081023