Melting Curve of Potassium Carbonate K2CO3 at High Pressures

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Concurrent DTA and Ionic Conduction Experiments at Ambient Pressure (1 Bar)

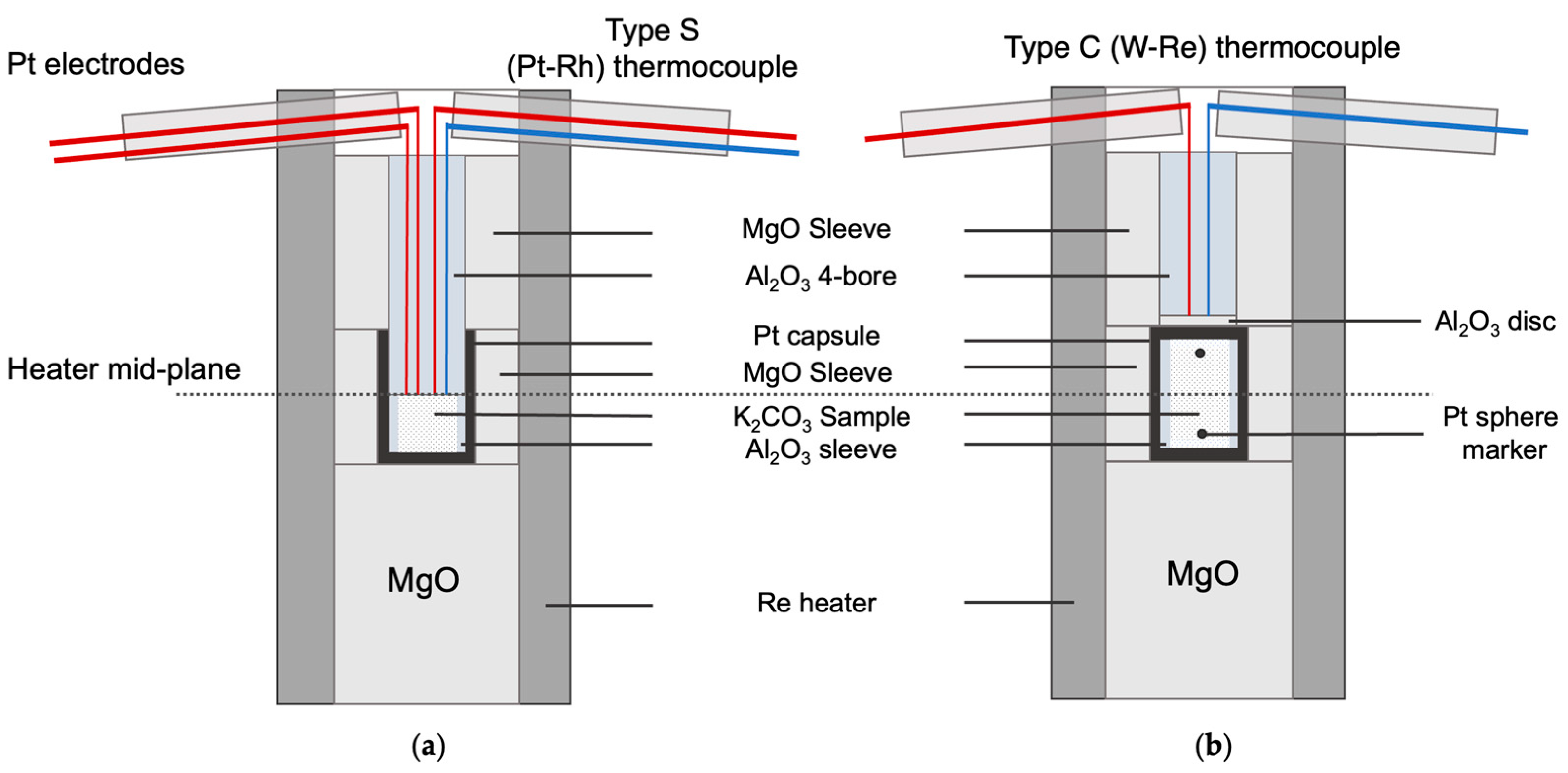

2.2. Ionic Conduction Experiments at High Pressures

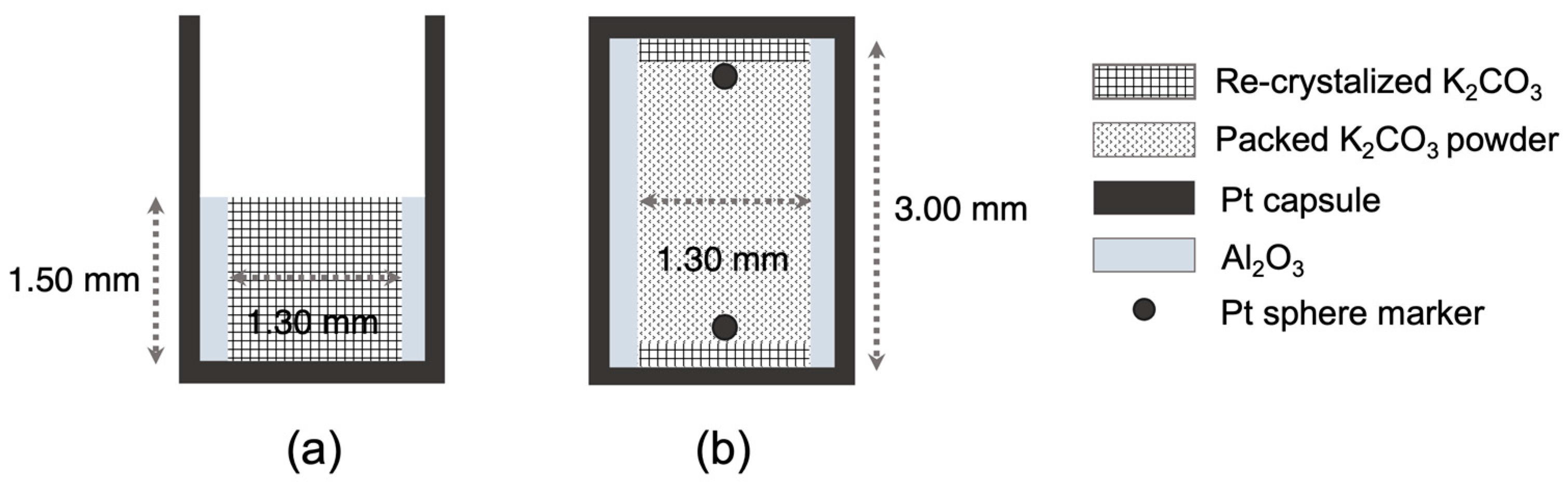

2.3. Pt Sphere Experiments on K2CO3 at High Pressures and X-Ray Radiography

3. Results

3.1. Concurrent DTA and Ionic Conduction Experiment on K2CO3 at 1 Bar

3.2. Pressure Calibration Using NaCl Melting Curve

3.3. Ionic Conduction Experiments on K2CO3 at High Pressures

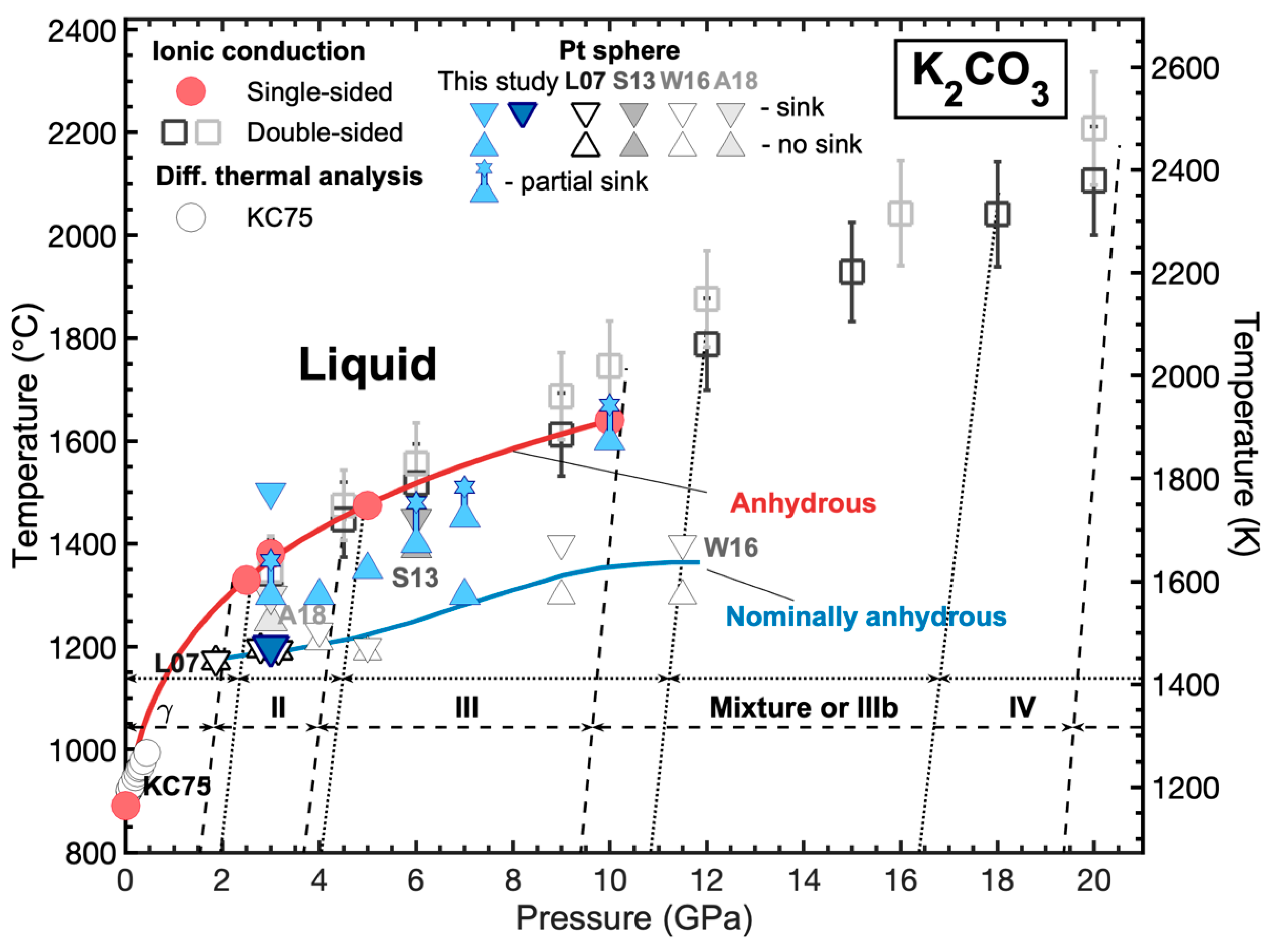

3.4. Pt Sphere Experiments on K2CO3 at High Pressures

3.5. Melting Curve of K2CO3 at High Pressures

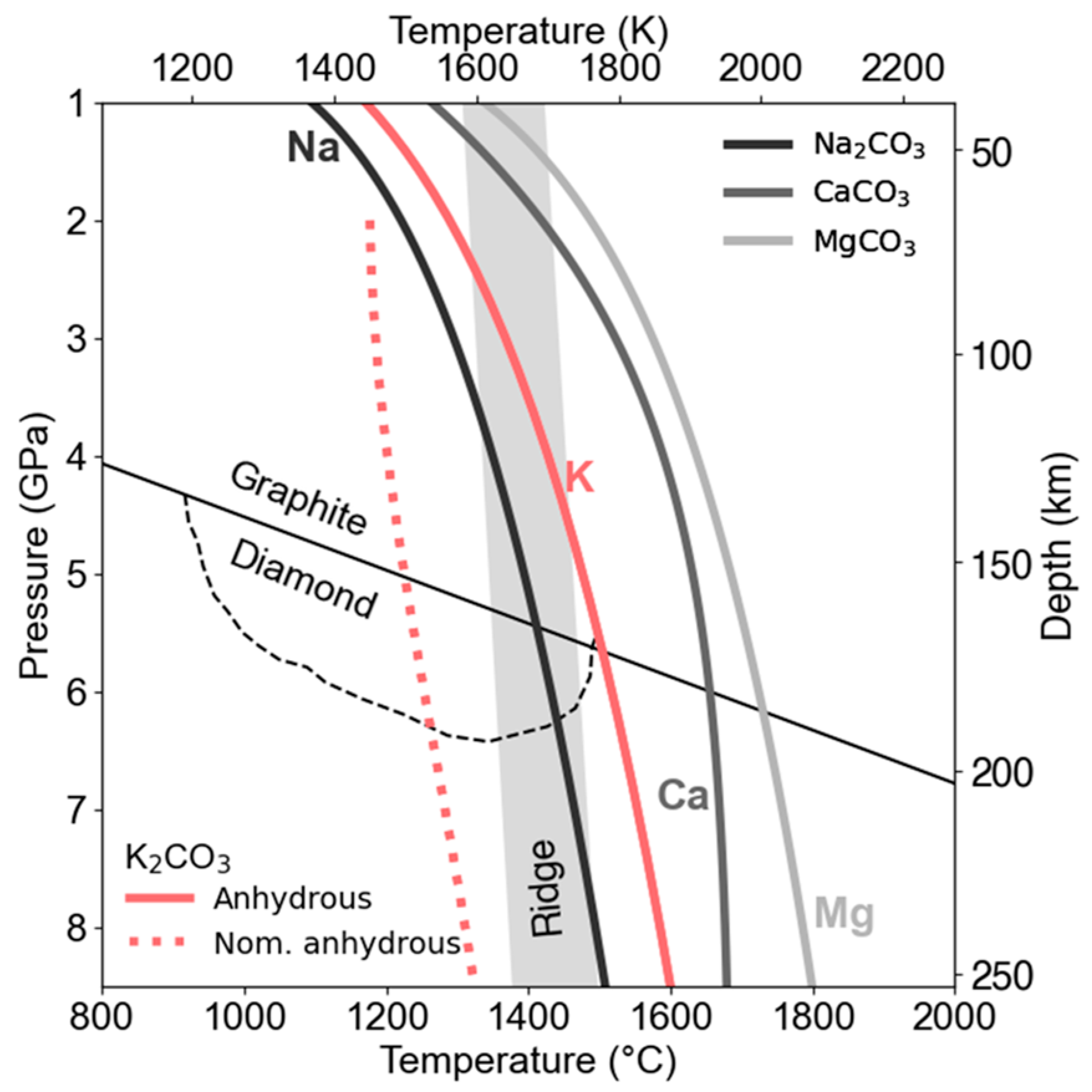

4. Discussion

4.1. Concurrent Ionic Conduction Method and DTA at 1 Bar

4.2. Ionic Conduction Experiments on K2CO3 at High Pressures

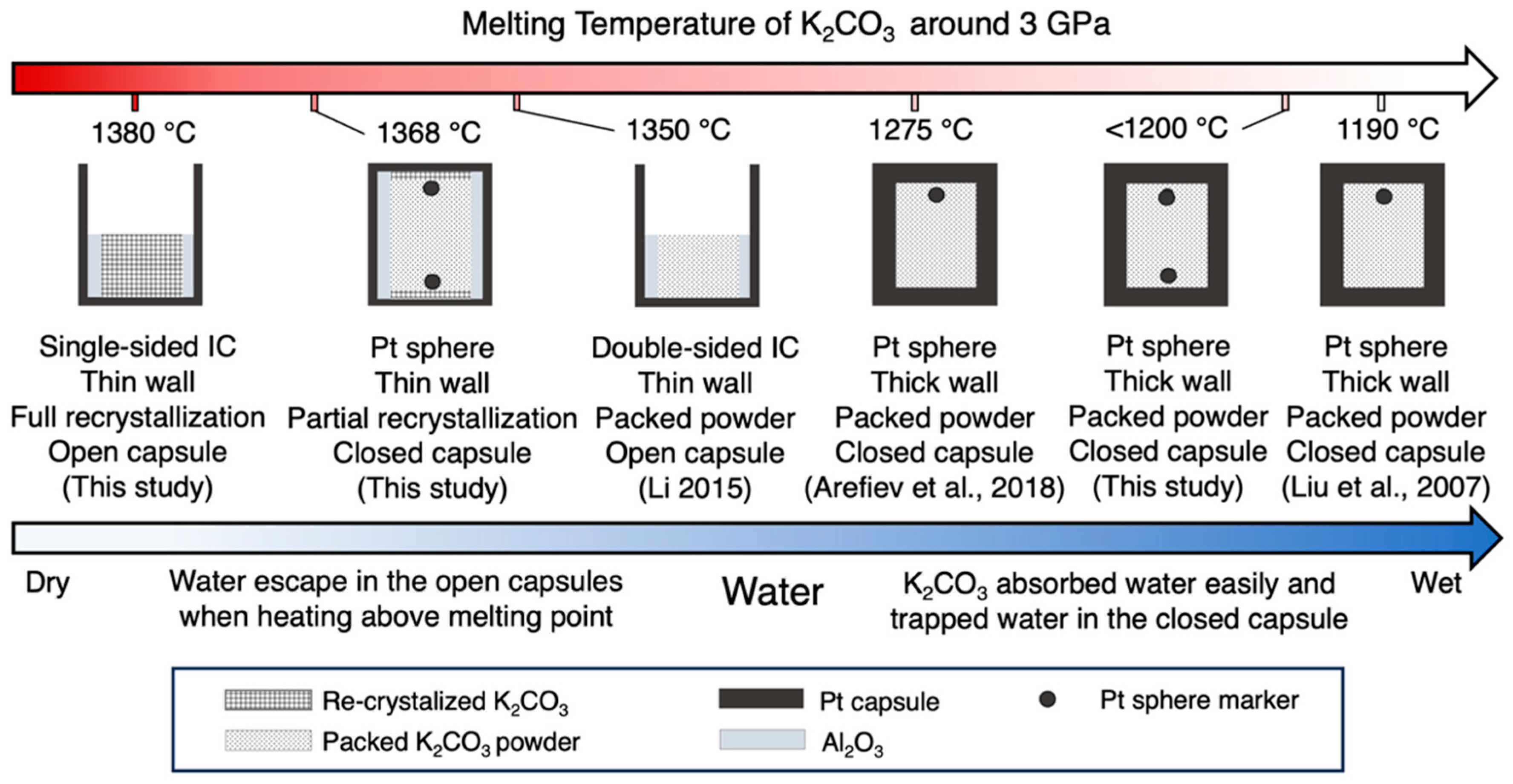

4.3. Pt Sphere Experiments on K2CO3 at High Pressures

4.4. Discrepancies Among Melting Points of K2CO3 and Effect of Water

4.5. Implications for Diamond Formation

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Pressure Calibration Using NaCl Melting Curve at High Pressures

Appendix B

Recrystallization of Starting Materials

References

- Dasgupta, R.; Mallik, A.; Tsuno, K.; Withers, A.C.; Hirth, G.; Hirschmann, M.M. Carbon-Dioxide-Rich Silicate Melt in the Earth’s Upper Mantle. Nature 2013, 493, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, R.; Hirschmann, M.M. The Deep Carbon Cycle and Melting in Earth’s Interior. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2010, 298, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dasgupta, R.; Hirschmann, M.M. Melting in the Earth’s Deep Upper Mantle Caused by Carbon Dioxide. Nature 2006, 440, 659–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Redfern, S.A.T.; Giovannelli, D. Introduction: Deep Carbon Cycle through Five Reactions. Am. Mineral. 2019, 104, 465–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Jing, Z.; Bajgain, S.K.; Mookherjee, M.; Van Orman, J.A.; Yu, T.; Wang, Y. High-Pressure Elastic Properties of Dolomite Melt Supporting Carbonate-Induced Melting in Deep Upper Mantle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 18285–18291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, F.; Malki, M.; Iacono-Marziano, G.; Pichavant, M.; Scaillet, B. Carbonatite Melts and Electrical Conductivity in the Asthenosphere. Science 2008, 322, 1363–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sifré, D.; Hashim, L.; Gaillard, F. Effects of Temperature, Pressure and Chemical Compositions on the Electrical Conductivity of Carbonated Melts and Its Relationship with Viscosity. Chem. Geol. 2015, 418, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifré, D.; Gardés, E.; Massuyeau, M.; Hashim, L.; Hier-Majumder, S.; Gaillard, F. Electrical Conductivity during Incipient Melting in the Oceanic Low-Velocity Zone. Nature 2014, 509, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal’yanov, N.; Sokol, A.G.; Borzdov, M.; Khokhryakov, A.F. Fluid-Bearing Alkaline Carbonate Melts as the Medium for the Formation of Diamonds in the Earth’s Mantle: An Experimental Study. Lithos 2002, 60, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmerman, S.; Spivak, A.V.; Jones, A.P. Carbonatitic Melts and Their Role in Diamond Formation in the Deep Earth. Elements 2021, 17, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, D.G.; Brenker, F.E.; Nestola, F.; McNeill, J.; Nasdala, L.; Hutchison, M.T.; Matveev, S.; Mather, K.; Silversmit, G.; Schmitz, S.; et al. Hydrous Mantle Transition Zone Indicated by Ringwoodite Included within Diamond. Nature 2014, 507, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.B. Sodium Carbonate Lavas from Oldoinyo Lengai, Tanganyika. Nature 1962, 195, 1075–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyle, D.M.; Dawson, J.B.; Ivanovich, M. Short-Lived Decay Series Disequilibria in the Natrocarbonatite Lavas of Oldoinyo Lengai, Tanzania: Constraints on the Timing of Magma Genesis. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1991, 105, 378–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefiev, A.V.; Shatskiy, A.; Podborodnikov, I.V.; Litasov, K.D. Melting and Subsolidus Phase Relations in the System K2CO3 –MgCO3 at 3 GPa. High Press. Res. 2018, 38, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatskiy, A.; Sharygin, I.S.; Gavryushkin, P.N.; Litasov, K.D.; Borzdov, Y.M.; Shcherbakova, A.V.; Higo, Y.; Funakoshi, K.-I.; Palyanov, Y.N.; Ohtani, E. The System K2CO3-MgCO3 at 6 GPa and 900–1450 °C. Am. Mineral. 2013, 98, 1593–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, J.; Lange, R.; Liu, J.; Militzer, B. Determination of Calcium Carbonate and Sodium Carbonate Melting Curves up to Earth’s Transition Zone Pressures with Implications for the Deep Carbon Cycle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2017, 457, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsura, T.; Ito, E. Melting and Subsolidus Phase Relations in the MgSiO3-MgCO3 System at High Pressures: Implications to Evolution of the Earth’s Atmosphere. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1990, 99, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Melting and Structural Transformations of Carbonates and Hydrous Phases in Earth’s Mantle. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Klement, W.; Cohen, L.H. Solid-Solid and Solid-Liquid Transitions in K2CO3, Na2CO3 and Li2CO3: Investigations to ≥5 Kbar by Differential Thermal Analysis; Thermodynamics and Structural Correlations. Berichte Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 1975, 79, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Tenner, T.J.; Lange, R.A. Do Carbonate Liquids Become Denser than Silicate Liquids at Pressure? Constraints from the Fusion Curve of K2CO3 to 3.2 GPa. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 2007, 153, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Liu, Q.; Inoue, T.; Li, B.; Pottish, S.; Wood, J.; Yang, C.; Tao, R. The K2CO3 Fusion Curve Revisited: New Experiments at Pressures up to 12 GPa. J. Mineral. Petrol. Sci. 2016, 111, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatskiy, A.; Podborodnikov, I.V.; Arefiev, A.V.; Litasov, K.D.; Chanyshev, A.D.; Sharygin, I.S.; Karmanov, N.S.; Ohtani, E. Effect of Alkalis on the Reaction of Clinopyroxene with Mg-Carbonate at 6 GPa: Implications for Partial Melting of Carbonated Lherzolite. Am. Mineral. 2017, 102, 1934–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, E.S.; O’Neill, M.J.; Justin, J.; Brenner, N. A Differential Scanning Calorimeter for Quantitative Differential Thermal Analysis. Anal. Chem. 1964, 36, 1233–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Dong, J.; Si, Y.; Zhu, F.; Li, J. Melting Curve of Potassium Chloride from in Situ Ionic Conduction Measurements. Minerals 2020, 10, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, J. Melting Curve of NaCl to 20 GPa from Electrical Measurements of Capacitive Current. Am. Mineral. 2015, 100, 1892–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.; Li, J. Castable Solid Pressure Media for Multianvil Devices. Matter Radiat. Extrem. 2020, 5, 018402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Li, J.; Zhu, F.; Li, Z.; Farawi, R. Melting Curve Minimum of Barium Carbonate BaCO3 near 5 GPa. Am. Mineral. 2019, 104, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leinenweber, K.D.; Tyburczy, J.A.; Sharp, T.G.; Soignard, E.; Diedrich, T.; Petuskey, W.B.; Wang, Y.; Mosenfelder, J.L. Cell Assemblies for Reproducible Multi-Anvil Experiments (the COMPRES Assemblies). Am. Mineral. 2012, 97, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F.; Glatzel, G. Bemerkungen zur Schmelzdruckkurve. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 1929, 178, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavryushkin, P.N.; Bekhtenova, A.; Lobanov, S.S.; Shatskiy, A.; Likhacheva, A.Y.; Sagatova, D.; Sagatov, N.; Rashchenko, S.V.; Litasov, K.D.; Sharygin, I.S.; et al. High-Pressure Phase Diagrams of Na2CO3 and K2CO3. Minerals 2019, 9, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, G.J.; Neuenschwander, E.; Kelly, F.J. High-Temperature Heat Content and Related Properties for Li2CO3, Na2CO3, K2CO3, and the Ternary Eutectic Mixture. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1963, 59, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlen, S.R.; Boettcher, A.L. The Quartz⇋ Coesite Transformation: A Precise Determination and the Effects of Other Components. J. Geophys. Res. 1982, 87, 7073–7078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, D.L.; Bassett, W.A.; Merrill, L.; Hall, H.T.; Barnett, J.D. High-Pressure Calibration: A Critical Review. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1972, 1, 773–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Utsumi, W.; Liebermann, R.C. In Situ X-Ray Observations of the Coesite-Stishovite Transition: Reversed Phase Boundary and Kinetics. Phys. Chem. Miner. 1996, 23, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susaki, J.; Akaogi, M.; Akimoto, S.; Shimomura, O. Garnet-perovskite Transformation in CaGeO3: In-situ X-ray Measurements Using Synchrotron Radiation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1985, 12, 729–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsura, T.; Ito, E. The System Mg2SiO4-Fe2SiO4 at High Pressures and Temperatures: Precise Determination of Stabilities of Olivine, Modified Spinel, and Spinel. J. Geophys. Res. 1989, 94, 15663–15670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal’yanov, Y.N.; Sokol, A.G.; Borzdov, Y.M.; Khokhryakov, A.F.; Shatsky, A.F.; Sobolev, N.V. The Diamond Growth from Li2CO3, Na2CO3, K2CO3 and Cs2CO3 Solvent-catalysts at P=7 GPa and T=1700 °C. Diam. Relat. Mater. 1999, 8, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, A.G.; Tomilenko, A.A.; Pal’Yanov, Y.N.; Borzdov, Y.M.; Pal’Yanova, G.A.; Khokhryakov, A.F. Fluid Regime of Diamond Crystallisation in Carbonate-Carbon Systems. EJM 2000, 12, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Exp. ID | Pressure 1 (GPa) | Melting Temperature 2 (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement | Average | ||

| 8 mm TEL single-sided configuration | |||

| M100623_8 | 2.5 | 1328 | 1330 ± 2 |

| 1331 | |||

| M110623_8 | 3.0 | 1385 | 1380 ± 7 |

| 1375 | |||

| M100624_8 | 5.0 | 1475 ± 20 | 1475 |

| M061624_8 | 10.0 | 1641 ± 14 | 1641 |

| 5 mm TEL double-sided configuration [18] | |||

| M081814_5 | 3.0 | 1337 | 1353 ± 14 |

| 1364 | |||

| 1359 | |||

| 4.5 | 1455 | 1456 ± 1 | |

| 1457 | |||

| 6.0 | 1524 | 1520 ± 6 | |

| 1516 | |||

| 9.0 | 1623 | 1621 ± 3 | |

| 1619 | |||

| 12.0 | 1785 | 1788 ± 3 | |

| 1790 | |||

| 15.0 | 1936 | 1933 ± 4 | |

| 1930 | |||

| 18.0 | 2050 | 2045 ± 7 | |

| 2040 | |||

| 20.0 | 2110 | 2108 ± 2 | |

| 2107 | |||

| M090214_5 | 3.0 | 1343 | 1348 ± 7 |

| 1353 | |||

| 4.5 | 1475 | 1476 ± 1 | |

| 1476 | |||

| 6.0 | 1558 | 1557 ± 1 | |

| 1555 | |||

| 9.0 | 1688 | 1688 ± 1 | |

| 1687 | |||

| 10.0 | 1751 | 1750 ± 1 | |

| 1749 | |||

| 12.0 | 1875 | 1876 ± 1 | |

| 1876 | |||

| 16.0 | 2048 | 2046 ± 3 | |

| 2043 | |||

| 20.0 | 2209 | 2208 ± 2 | |

| 2206 | |||

| Exp. ID | Pressure 1 (GPa) | Thermocouple Temperature (°C) | Upper Sphere Position | Upper Sphere Movement 2 | Melting Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M011624 | 4.0 | 1300 | Top | No sink | >1380 |

| M011924 | 5.0 | 1352 | Top | No sink | >1422 |

| M020424 3 | 3.0 | ~1500 | Bottom | Sink | <1500 |

| M022024 | 3.0 | 1300 | Middle | Partial sink | 1368 |

| M030324 4 | 3.0 | 1200 | Bottom | Sink | <1200 |

| M030824 | 6.0 | 1400 | Middle | Partial sink | 1480 |

| M031024 | 7.0 | 1450 | Middle | Partial sink | 1510 |

| M062224 | 7.0 | 1300 | Top | No sink | >1394 |

| M092924 | 10.0 | 1600 | Middle | Partial sink | 1670 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lu, J.; He, S.; Lange, R.; Li, J. Melting Curve of Potassium Carbonate K2CO3 at High Pressures. Minerals 2025, 15, 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030217

Lu J, He S, Lange R, Li J. Melting Curve of Potassium Carbonate K2CO3 at High Pressures. Minerals. 2025; 15(3):217. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030217

Chicago/Turabian StyleLu, Jiaqi, Siyuan He, Rebecca Lange, and Jie Li. 2025. "Melting Curve of Potassium Carbonate K2CO3 at High Pressures" Minerals 15, no. 3: 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030217

APA StyleLu, J., He, S., Lange, R., & Li, J. (2025). Melting Curve of Potassium Carbonate K2CO3 at High Pressures. Minerals, 15(3), 217. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030217