Thermochronology of the Kalba–Narym Batholith and the Irtysh Shear Zone (Altai Accretion–Collision System): Geodynamic Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

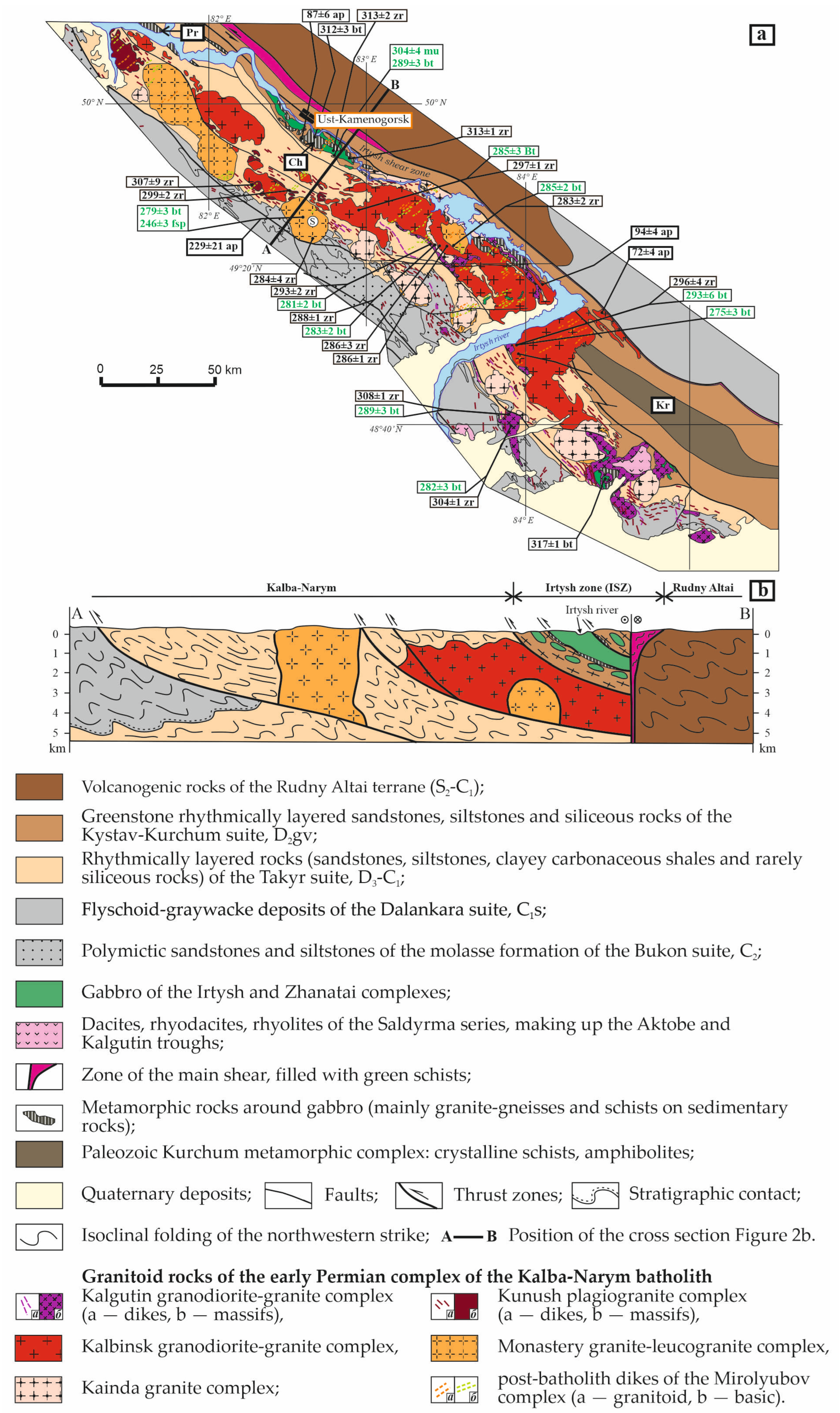

2. Geological Framework

2.1. The AACS Formation

2.2. The Kalba–Narym Batholith

2.3. The Irtysh Gabbro Complex

2.4. The Chechek Metamorphic Complex

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. The Fieldwork

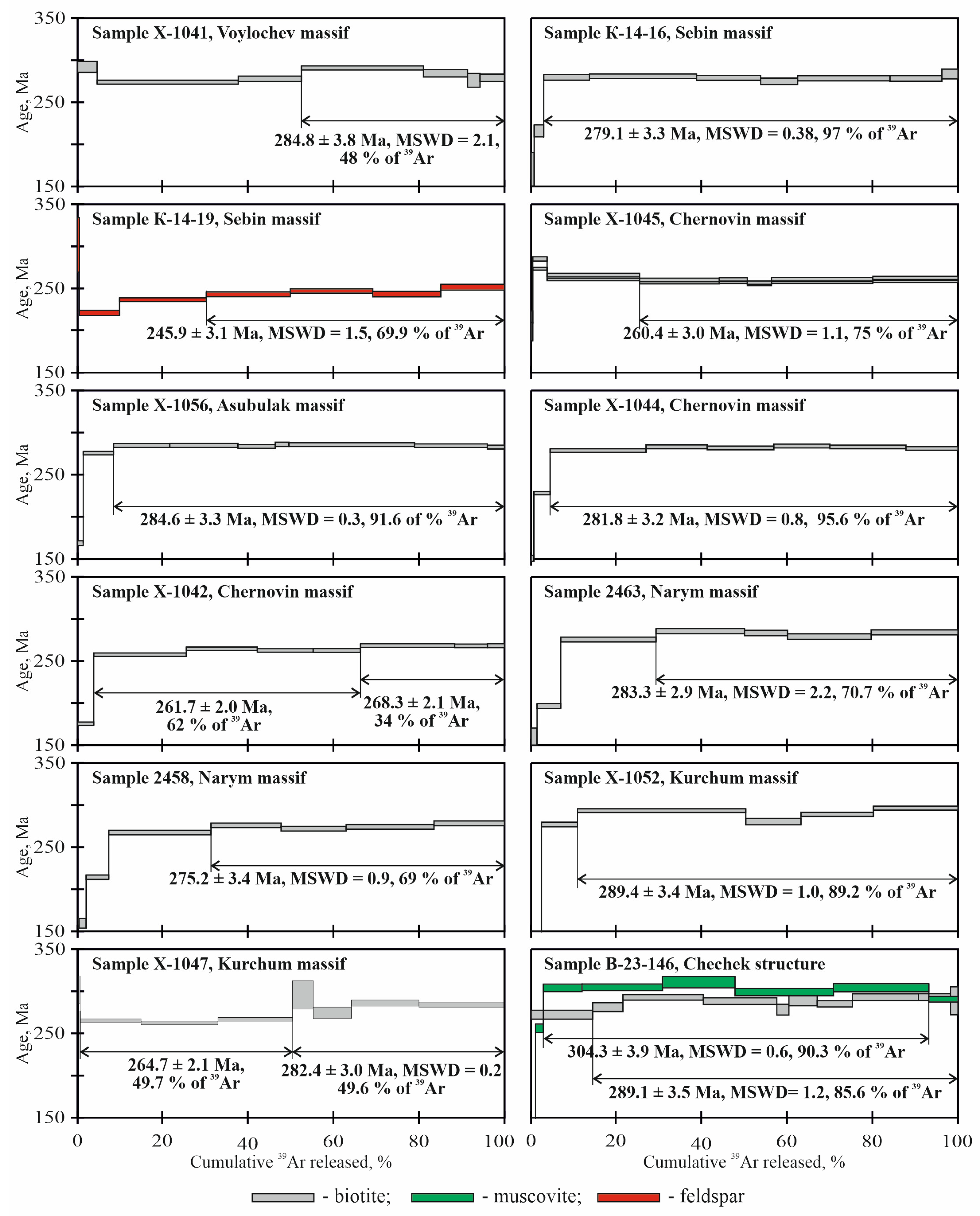

4.2. The 40Ar/39Ar Dating

5. Discussion

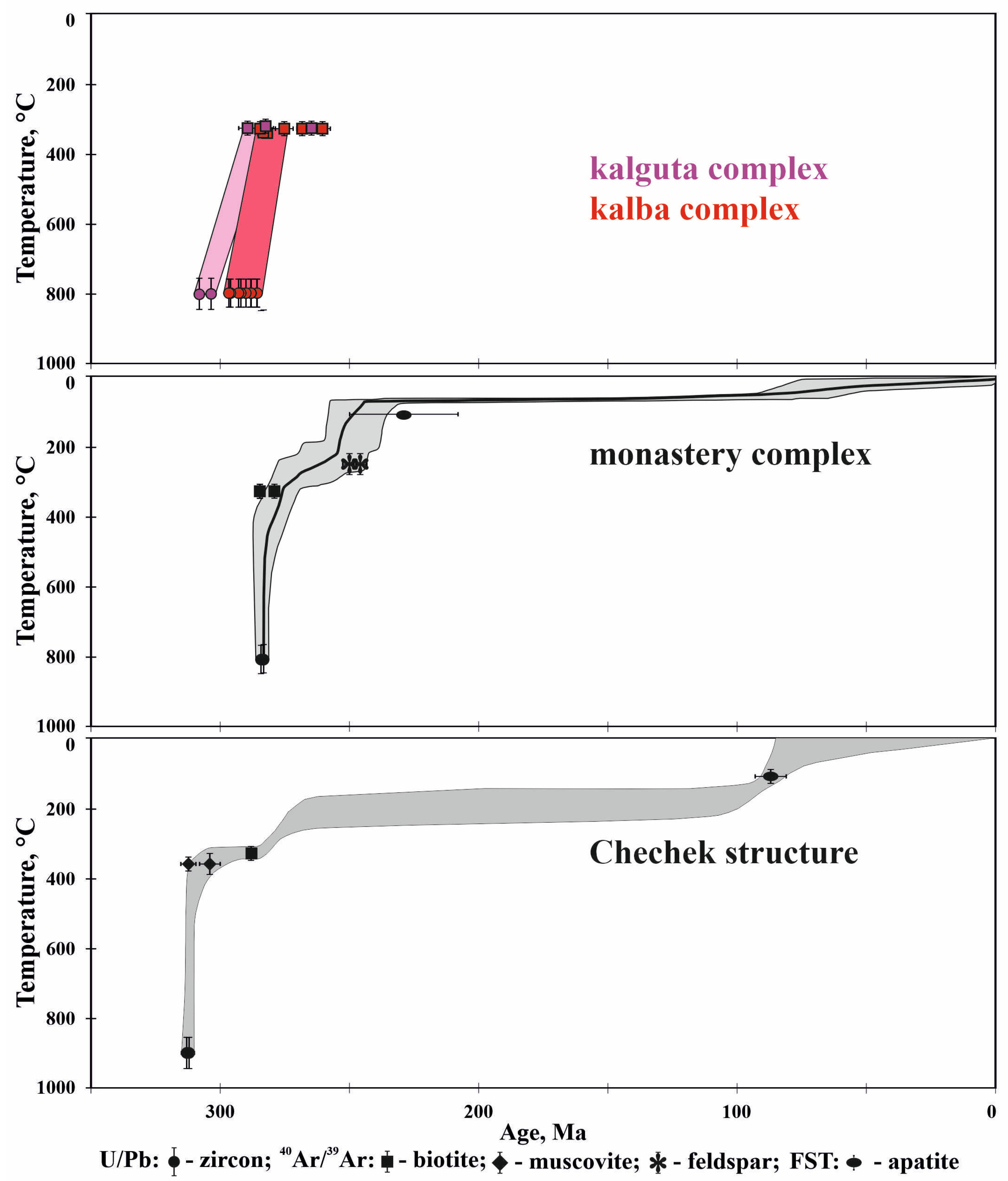

5.1. Ar/39Ar Dating

5.2. Thermochronology

5.3. Geological Implications

6. Conclusions

- At an early stage in the Carboniferous–early Permian (312–289 Ma), the ISZ formed as a shallow thrust structure under conditions of NE–SW compression. Synchronously with the thrust, the intrusion of the gabbro of the Irtysh complex (Surov massif and others) and the formation of tectonic mélange with gabbro-cataclasites and metamorphic rocks occurred. The foundation of the Chechek dome structure corresponds to this stage.

- At the next stage, the formation of a cover-thrust structure involving turbidites of the Middle Devonian–early Carboniferous (Kalba–Narym terrane) led to melting at the middle levels of the thickened crust and the formation of the early Permian Kalba–Narym batholith (297–284 Ma).

- Rapid denudation of the created orogen occurred at the final stage of collapse until the Early Triassic (279–229 Ma).

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| T °C | 40Ar (cm3 STP) | 40Ar/39Ar ± 1σ | 38Ar/39Ar ± 1σ | 37Ar/39Ar ± 1σ | 36Ar/39Ar ± 1σ | Ca/K | ∑39Ar (%) | Age (Ma) ± 1σ | 40Ar * (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample X-1041 biotite, weight 4.95 mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (850–1100 °C) = 284.8 ± 3.8 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 500 | 390.5 | 57.3 ± 0.3 | 0.01922 ± 0.00520 | 0.00002 ± 0.00002 | 0.00021 ± 0.00436 | 0.0001 | 4.6 | 291.7 ± 6.6 | 99.9 |

| 650 | 2617.0 | 53.4 ± 0.1 | 0.00770 ± 0.00035 | 0.00008 ± 0.00003 | 0.00001 ± 0.00083 | 0.0003 | 37.6 | 273.5 ± 2.4 | 100.0 |

| 750 | 1191.1 | 54.2 ± 0.1 | 0.01199 ± 0.00168 | 0.04209 ± 0.00460 | 0.00001 ± 0.00169 | 0.1515 | 52.4 | 277.6 ± 3.2 | 100.0 |

| 850 | 2415.3 | 57.0 ± 0.1 | 0.00001 ± 0.00035 | 0.00026 ± 0.00250 | 0.00001 ± 0.00069 | 0.0009 | 81.0 | 290.6 ± 2.4 | 100.0 |

| 950 | 853.8 | 55.7 ± 0.2 | 0.00523 ± 0.00211 | 0.00009 ± 0.00007 | 0.00014 ± 0.00272 | 0.0003 | 91.3 | 284.2 ± 4.4 | 99.9 |

| 1025 | 234.8 | 54.0 ± 0.3 | 0.00049 ± 0.00007 | 0.00027 ± 0.00031 | 0.00044 ± 0.00554 | 0.0010 | 94.3 | 275.8 ± 8.2 | 99.8 |

| 1100 | 461.2 | 54.3 ± 0.1 | 0.00826 ± 0.00263 | 0.00107 ± 0.00002 | 0.00033 ± 0.00149 | 0.0039 | 100.0 | 277.4 ± 3.0 | 99.8 |

| Sample KA-14-16 biotite, weight 52.01 mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (720–1130 °C) = 279.1 ± 3.3 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 500 | 22.5 | 43.8 ± 0.7 | 0.05938 ± 0.02329 | 16.63285 ± 7.78847 | 0.06168 ± 0.01523 | 59.9 | 0.7 | 162.8 ± 27.5 | 58.4 |

| 610 | 97.2 | 59.8 ± 0.3 | 0.05926 ± 0.00630 | 3.99485 ± 2.93448 | 0.08588 ± 0.00393 | 14.4 | 3.0 | 216.0 ± 7.2 | 57.6 |

| 720 | 371.4 | 48.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01561 ± 0.00161 | 1.73254 ± 0.60034 | 0.00884 ± 0.00130 | 6.3 | 13.6 | 279.6 ± 3.4 | 94.6 |

| 800 | 844.9 | 46.4 ± 0.1 | 0.01708 ± 0.00025 | 0.01537 ± 0.15000 | 0.00280 ± 0.00051 | 0.1 | 38.8 | 280.9 ± 2.7 | 98.2 |

| 850 | 509.1 | 46.7 ± 0.1 | 0.01585 ± 0.00100 | 0.14254 ± 0.38051 | 0.00485 ± 0.00090 | 0.5 | 53.8 | 279.1 ± 3.0 | 96.9 |

| 920 | 296.8 | 47.4 ± 0.1 | 0.02001 ± 0.00191 | 1.82078 ± 1.74010 | 0.00974 ± 0.00179 | 6.5 | 62.4 | 274.9 ± 3.9 | 93.9 |

| 1020 | 730.9 | 46.6 ± 0.1 | 0.01493 ± 0.00108 | 0.02376 ± 0.30843 | 0.00487 ± 0.00091 | 0.1 | 84.1 | 278.5 ± 3.0 | 96.9 |

| 1080 | 416.8 | 47.3 ± 0.1 | 0.01827 ± 0.00208 | 2.03645 ± 0.75456 | 0.00751 ± 0.00130 | 7.3 | 96.2 | 278.2 ± 3.4 | 95.3 |

| 1130 | 131.2 | 48.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01356 ± 0.00322 | 3.15342 ± 1.56345 | 0.00651 ± 0.00311 | 11.3 | 100.0 | 283.6 ± 5.9 | 96.0 |

| Sample KA-14-19 feldspar, weight 125.67 mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (825–1130 °C) = 245.9 ± 3.1 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 500 | 16.9 | 65.7 ± 1.7 | 0.02802 ± 0.02545 | 1.26424 ± 3.96484 | 0.05341 ± 0.01919 | 4.5 | 0.4 | 301.8 ± 32.4 | 76.0 |

| 625 | 240.2 | 40.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01436 ± 0.00227 | 0.56055 ± 0.24672 | 0.01465 ± 0.00147 | 2.0 | 9.8 | 220.7 ± 3.2 | 89.2 |

| 725 | 524.4 | 40.4 ± 0.1 | 0.01805 ± 0.00072 | 0.40446 ± 0.24077 | 0.00672 ± 0.00034 | 1.5 | 30.1 | 236.5 ± 2.2 | 95.1 |

| 825 | 517.4 | 41.2 ± 0.1 | 0.01845 ± 0.00062 | 0.35746 ± 0.18756 | 0.00590 ± 0.00109 | 1.3 | 49.8 | 243.0 ± 2.9 | 95.8 |

| 925 | 515.0 | 41.7 ± 0.1 | 0.01629 ± 0.00125 | 0.31492 ± 0.28741 | 0.00517 ± 0.00078 | 1.1 | 69.1 | 246.9 ± 2.6 | 96.3 |

| 1025 | 429.3 | 42.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01733 ± 0.00101 | 0.69472 ± 0.04437 | 0.00849 ± 0.00136 | 2.5 | 85.1 | 243.2 ± 3.2 | 94.0 |

| 1130 | 405.6 | 42.7 ± 0.1 | 0.01868 ± 0.00158 | 1.80304 ± 0.54957 | 0.00575 ± 0.00157 | 6.5 | 100.0 | 251.4 ± 3.5 | 96.0 |

| Sample X-1045 biotite, weight 9.86 mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (750–1100 °C) = 260.4 ± 3.0 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 500 | 91.0 | 45.9 ± 0.3 | 0.06044 ± 0.01423 | 3.80707 ± 0.18499 | 0.02491 ± 0.00748 | 13.70 | 0.4 | 198.8 ± 11.0 | 84.0 |

| 600 | 965.2 | 55.2 ± 0.1 | 0.02026 ± 0.00145 | 0.25325 ± 0.02180 | 0.00471 ± 0.00109 | 0.91 | 3.7 | 285.2 ± 2.6 | 97.5 |

| 700 | 6005.1 | 53.1 ± 0.1 | 0.01943 ± 0.00024 | 0.03393 ± 0.00338 | 0.00196 ± 0.00053 | 0.12 | 25.4 | 266.0 ± 2.1 | 98.9 |

| 750 | 5037.7 | 51.8 ± 0.1 | 0.01511 ± 0.00008 | 0.01110 ± 0.00074 | 0.00174 ± 0.00058 | 0.04 | 44.1 | 260.3 ± 2.1 | 99.0 |

| 800 | 1765.3 | 51.7 ± 0.1 | 0.01582 ± 0.00033 | 0.00828 ± 0.00220 | 0.00083 ± 0.00035 | 0.03 | 50.6 | 260.9 ± 2.0 | 99.5 |

| 900 | 1522.2 | 51.4 ± 0.1 | 0.01543 ± 0.00024 | 0.02381 ± 0.00194 | 0.00268 ± 0.00046 | 0.09 | 56.3 | 257.1 ± 2.0 | 98.5 |

| 1025 | 6418.3 | 51.9 ± 0.1 | 0.01449 ± 0.00008 | 0.00698 ± 0.00046 | 0.00123 ± 0.00054 | 0.02 | 80.1 | 261.2 ± 2.1 | 99.3 |

| 1100 | 5418.4 | 52.1 ± 0.1 | 0.01400 ± 0.00009 | 0.00207 ± 0.00067 | 0.00106 ± 0.00031 | 0.01 | 100.0 | 262.6 ± 2.0 | 99.4 |

| Sample X-1056 biotite, weight 71.5 mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (650–1130 °C) = 284.6 ± 3.3 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 500 | 71.2 | 42.3 ± 0.1 | 0.02143 ± 0.00369 | 0.14170 ± 0.01263 | 0.03549 ± 0.00165 | 0.51 | 1.3 | 169.0 ± 2.8 | 75.2 |

| 600 | 531.1 | 58.4 ± 0.1 | 0.01791 ± 0.00040 | 0.02686 ± 0.00165 | 0.01668 ± 0.00036 | 0.10 | 8.4 | 275.7 ± 2.1 | 91.6 |

| 650 | 961.7 | 56.8 ± 0.1 | 0.01561 ± 0.00020 | 0.00895 ± 0.00096 | 0.00504 ± 0.00026 | 0.03 | 21.6 | 284.7 ± 2.2 | 97.4 |

| 700 | 1151.4 | 56.1 ± 0.1 | 0.01555 ± 0.00018 | 0.00523 ± 0.00080 | 0.00246 ± 0.00023 | 0.02 | 37.6 | 285.1 ± 2.2 | 98.7 |

| 750 | 623.5 | 55.7 ± 0.1 | 0.01624 ± 0.00013 | 0.01362 ± 0.00144 | 0.00220 ± 0.00056 | 0.05 | 46.3 | 283.5 ± 2.3 | 98.8 |

| 850 | 229.2 | 55.9 ± 0.1 | 0.01740 ± 0.00110 | 0.02538 ± 0.00314 | 0.00093 ± 0.00096 | 0.09 | 49.5 | 286.1 ± 2.5 | 99.5 |

| 975 | 2125.4 | 56.2 ± 0.1 | 0.01544 ± 0.00008 | 0.01527 ± 0.00029 | 0.00235 ± 0.00025 | 0.05 | 78.9 | 285.7 ± 2.2 | 98.8 |

| 1050 | 1223.3 | 55.9 ± 0.1 | 0.01539 ± 0.00019 | 0.03660 ± 0.00062 | 0.00218 ± 0.00032 | 0.13 | 96.0 | 284.4 ± 2.2 | 98.9 |

| 1130 | 288.9 | 56.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01608 ± 0.00041 | 0.15098 ± 0.00084 | 0.00354 ± 0.00061 | 0.54 | 100.0 | 282.7 ± 2.3 | 98.1 |

| Sample X-1044 biotite, weight 71.5 mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (650–1130 °C) = 284.6 ± 3.3 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 500 | 19.0 | 39.2 ± 0.2 | 0.02941 ± 0.00265 | 0.40784 ± 0.01722 | 0.03673 ± 0.00212 | 1.47 | 0.6 | 150.7 ± 3.5 | 72.3 |

| 600 | 140.4 | 49.1 ± 0.1 | 0.01934 ± 0.00098 | 0.09718 ± 0.00144 | 0.01826 ± 0.00049 | 0.35 | 4.4 | 227.9 ± 1.9 | 89.0 |

| 700 | 934.6 | 55.3 ± 0.1 | 0.01565 ± 0.00017 | 0.02390 ± 0.00042 | 0.00370 ± 0.00018 | 0.09 | 26.9 | 278.5 ± 2.1 | 98.0 |

| 775 | 599.7 | 55.7 ± 0.1 | 0.01575 ± 0.00028 | 0.01383 ± 0.00187 | 0.00173 ± 0.00053 | 0.05 | 41.2 | 282.9 ± 2.3 | 99.1 |

| 875 | 658.0 | 56.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01646 ± 0.00041 | 0.03710 ± 0.00134 | 0.00374 ± 0.00039 | 0.13 | 56.9 | 281.6 ± 2.2 | 98.0 |

| 975 | 554.3 | 56.2 ± 0.1 | 0.01502 ± 0.00032 | 0.04986 ± 0.00169 | 0.00263 ± 0.00030 | 0.18 | 70.0 | 284.0 ± 2.2 | 98.6 |

| 1050 | 749.2 | 55.9 ± 0.1 | 0.01536 ± 0.00033 | 0.07133 ± 0.00117 | 0.00257 ± 0.00016 | 0.26 | 87.8 | 282.8 ± 2.1 | 98.6 |

| 1130 | 512.0 | 56.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01504 ± 0.00023 | 0.19017 ± 0.00162 | 0.00416 ± 0.00035 | 0.68 | 100.0 | 281.0 ± 2.2 | 97.8 |

| Sample X-1042 biotite, weight 5.81 mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (900–1100 °C) = 268.3 ± 2.1 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 500 | 500.0 | 40.8 ± 0.1 | 0.02330 ± 0.00072 | 0.03415 ± 0.00579 | 0.02496 ± 0.00101 | 0.12 | 3.8 | 175.4 ± 2.0 | 81.9 |

| 600 | 3636.3 | 51.4 ± 0.1 | 0.01567 ± 0.00013 | 0.00354 ± 0.00103 | 0.00405 ± 0.00027 | 0.01 | 25.5 | 257.6 ± 2.0 | 97.7 |

| 675 | 2827.7 | 52.2 ± 0.1 | 0.01543 ± 0.00016 | 0.00801 ± 0.00123 | 0.00160 ± 0.00049 | 0.03 | 42.1 | 264.6 ± 2.1 | 99.1 |

| 800 | 2231.2 | 52.3 ± 0.1 | 0.01390 ± 0.00019 | 0.01403 ± 0.00131 | 0.00352 ± 0.00030 | 0.05 | 55.2 | 262.6 ± 2.0 | 98.0 |

| 900 | 1910.8 | 53.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01665 ± 0.00019 | 0.01726 ± 0.00161 | 0.00566 ± 0.00048 | 0.06 | 66.3 | 262.6 ± 2.1 | 96.8 |

| 1000 | 3810.1 | 53.0 ± 0.1 | 0.01522 ± 0.00012 | 0.01699 ± 0.00119 | 0.00161 ± 0.00053 | 0.06 | 88.3 | 268.5 ± 2.2 | 99.1 |

| 1050 | 1336.5 | 53.3 ± 0.1 | 0.01608 ± 0.00029 | 0.04024 ± 0.00315 | 0.00296 ± 0.00036 | 0.14 | 96.0 | 268.2 ± 2.1 | 98.4 |

| 1100 | 698.2 | 53.8 ± 0.1 | 0.02001 ± 0.00074 | 0.20121 ± 0.00596 | 0.00454 ± 0.00075 | 0.72 | 100.0 | 268.4 ± 2.3 | 97.5 |

| Sample 2463 biotite, weight 21.75mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (900–1130 °C) = 283.3 ± 2.9 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 500 | 30.0 | 33.3 ± 0.2 | 0.02120 ± 0.02120 | 0.08281 ± 0.01910 | 0.03934 ± 0.00628 | 0.2981 | 1.4 | 157.4 ± 13.0 | 65.2 |

| 600 | 124.5 | 35.0 ± 0.1 | 0.02333 ± 0.02333 | 0.02432 ± 0.00227 | 0.02595 ± 0.00105 | 0.0876 | 7.0 | 196.5 ± 2.9 | 78.2 |

| 700 | 603.9 | 42.3 ± 0.1 | 0.02018 ± 0.02018 | 0.01386 ± 0.00076 | 0.01009 ± 0.00041 | 0.0499 | 29.3 | 275.7 ± 2.9 | 93.0 |

| 800 | 578.4 | 43.5 ± 0.1 | 0.02021 ± 0.02021 | 0.01265 ± 0.00103 | 0.00903 ± 0.00053 | 0.0455 | 50.0 | 285.7 ± 3.1 | 93.9 |

| 900 | 278.7 | 43.2 ± 0.1 | 0.02146 ± 0.02146 | 0.02131 ± 0.00300 | 0.00928 ± 0.00077 | 0.0767 | 60.1 | 283.5 ± 3.2 | 93.7 |

| 1000 | 542.6 | 43.3 ± 0.1 | 0.02125 ± 0.02125 | 0.02368 ± 0.00146 | 0.01160 ± 0.00082 | 0.0852 | 79.6 | 279.2 ± 3.3 | 92.1 |

| 1130 | 564.7 | 43.3 ± 0.1 | 0.01970 ± 0.01970 | 0.07923 ± 0.00085 | 0.00912 ± 0.00028 | 0.2852 | 100.0 | 284.2 ± 2.9 | 93.8 |

| Sample 2458 biotite, weight 39.8 mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (800–1130 °C) = 275.2 ± 3.4 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 500 | 72.6 | 33.2 ± 0.1 | 0.02810 ± 0.00232 | 0.06164 ± 0.00328 | 0.03617 ± 0.00272 | 0.22 | 1.7 | 159.5 ± 5.7 | 67.8 |

| 600 | 257.9 | 37.1 ± 0.1 | 0.02130 ± 0.00044 | 0.02316 ± 0.00169 | 0.02176 ± 0.00069 | 0.08 | 7.0 | 214.4 ± 2.6 | 82.7 |

| 700 | 1329.7 | 42.3 ± 0.1 | 0.01945 ± 0.00012 | 0.01324 ± 0.00040 | 0.01173 ± 0.00020 | 0.05 | 31.0 | 267.5 ± 2.7 | 91.8 |

| 800 | 939.7 | 43.7 ± 0.1 | 0.01900 ± 0.00022 | 0.01347 ± 0.00059 | 0.01176 ± 0.00020 | 0.05 | 47.5 | 276.0 ± 2.8 | 92.1 |

| 900 | 863.0 | 43.1 ± 0.1 | 0.01906 ± 0.00018 | 0.01866 ± 0.00060 | 0.01204 ± 0.00031 | 0.07 | 62.8 | 272.1 ± 2.8 | 91.8 |

| 1000 | 1175.2 | 43.5 ± 0.1 | 0.01941 ± 0.00014 | 0.01991 ± 0.00042 | 0.01220 ± 0.00009 | 0.07 | 83.4 | 274.2 ± 2.7 | 91.7 |

| 1130 | 954.1 | 44.1 ± 0.1 | 0.01902 ± 0.00023 | 0.11439 ± 0.00069 | 0.01178 ± 0.00026 | 0.41 | 100.0 | 278.5 ± 2.8 | 92.1 |

| Sample X-1052 biotite, weight 3.3 mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (850–1100 °C) = 289.4 ± 3.4 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 500 | 20.9 | 62.2 ± 1.3 | 0.05037 ± 0.02094 | 0.87014 ± 0.18577 | 0.19526 ± 0.02100 | 3.132 | 0.6 | 24.4 ± 32.6 | 7.4 |

| 600 | 57.1 | 50.7 ± 0.2 | 0.03431 ± 0.00644 | 0.14209 ± 0.06394 | 0.11289 ± 0.00382 | 0.511 | 2.4 | 91.7 ± 5.8 | 34.3 |

| 700 | 294.1 | 58.4 ± 0.1 | 0.02949 ± 0.00139 | 0.05529 ± 0.01259 | 0.01127 ± 0.00136 | 0.199 | 10.8 | 276.5 ± 2.8 | 94.3 |

| 850 | 1430.0 | 60.3 ± 0.1 | 0.01715 ± 0.00023 | 0.02236 ± 0.00224 | 0.00558 ± 0.00032 | 0.080 | 50.3 | 293.0 ± 2.2 | 97.3 |

| 950 | 469.1 | 60.4 ± 0.1 | 0.01869 ± 0.00086 | 0.10875 ± 0.00882 | 0.01643 ± 0.00098 | 0.391 | 63.2 | 278.5 ± 2.5 | 92.0 |

| 950 | 469.1 | 60.4 ± 0.1 | 0.01869 ± 0.00086 | 0.10875 ± 0.00882 | 0.01643 ± 0.00098 | 0.391 | 63.2 | 278.5 ± 2.5 | 92.0 |

| 1025 | 614.1 | 60.2 ± 0.1 | 0.02091 ± 0.00062 | 0.00100 ± 0.00719 | 0.00849 ± 0.00087 | 0.004 | 80.2 | 288.5 ± 2.4 | 95.8 |

| 1100 | 719.8 | 60.4 ± 0.1 | 0.01887 ± 0.00070 | 0.02122 ± 0.00600 | 0.00381 ± 0.00065 | 0.076 | 100.0 | 296.0 ± 2.4 | 98.1 |

| Sample X-1047 biotite, weight 5.24 mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (800–1100 °C) = 282.4 ± 3.0 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 500 | 61.3 | 61.8 ± 0.5 | 0.03026 ± 0.00880 | 0.20401 ± 0.03479 | 0.00451 ± 0.01198 | 0.734 | 0.6 | 302.0 ± 16.6 | 97.8 |

| 650 | 1270.7 | 55.0 ± 0.1 | 0.00836 ± 0.00019 | 0.00036 ± 0.00135 | 0.00853 ± 0.00066 | 0.001 | 14.9 | 265.1 ± 2.2 | 95.4 |

| 700 | 1563.9 | 53.6 ± 0.1 | 0.01071 ± 0.00037 | 0.01784 ± 0.00141 | 0.00561 ± 0.00054 | 0.064 | 32.9 | 262.5 ± 2.1 | 96.9 |

| 750 | 1522.4 | 53.7 ± 0.1 | 0.01059 ± 0.00047 | 0.01534 ± 0.00308 | 0.00284 ± 0.00074 | 0.055 | 50.4 | 266.8 ± 2.2 | 98.4 |

| 800 | 501.3 | 63.8 ± 0.4 | 0.09076 ± 0.01452 | 0.00591 ± 0.02531 | 0.01590 ± 0.01223 | 0.021 | 55.2 | 295.9 ± 16.9 | 92.7 |

| 925 | 850.6 | 58.8 ± 0.1 | 0.00911 ± 0.00225 | 0.00423 ± 0.00551 | 0.01633 ± 0.00282 | 0.015 | 64.1 | 272.2 ± 4.4 | 91.8 |

| 1025 | 1485.6 | 58.0 ± 0.2 | 0.00832 ± 0.00177 | 0.00721 ± 0.00663 | 0.00321 ± 0.00213 | 0.026 | 79.9 | 286.1 ± 3.7 | 98.4 |

| 1100 | 1942.4 | 59.8 ± 0.1 | 0.01366 ± 0.00172 | 0.00397 ± 0.00436 | 0.01070 ± 0.00154 | 0.014 | 100.0 | 284.2 ± 3.0 | 94.7 |

| Sample B-23-146 biotite, weight 56.52 mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (540–1130 °C) = 289.1 ± 3.5 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 500 | 1475.3 | 45.5 ± 0.1 | 0.05481 ± 0.00154 | 0.08531 ± 0.00183 | 0.02000 ± 0.00236 | 0.307 | 14.4 | 272.2 ± 5.3 | 87.0 |

| 540 | 739.0 | 46.4 ± 0.1 | 0.05862 ± 0.00128 | 0.08216 ± 0.00440 | 0.01834 ± 0.00234 | 0.296 | 21.5 | 281.2 ± 5.2 | 88.3 |

| 580 | 2019.2 | 47.7 ± 0.1 | 0.03036 ± 0.00164 | 0.05464 ± 0.00293 | 0.01642 ± 0.00079 | 0.197 | 40.3 | 292.9 ± 3.3 | 89.8 |

| 680 | 1897.9 | 49.0 ± 0.1 | 0.03041 ± 0.00095 | 0.04899 ± 0.00194 | 0.02329 ± 0.00145 | 0.176 | 57.6 | 288.4 ± 4.0 | 86.0 |

| 750 | 329.6 | 51.9 ± 0.2 | 0.06585 ± 0.00199 | 0.14083 ± 0.00598 | 0.03874 ± 0.00306 | 0.507 | 60.4 | 278.3 ± 6.4 | 78.0 |

| 850 | 726.2 | 48.7 ± 0.2 | 0.05198 ± 0.00154 | 0.08909 ± 0.00517 | 0.02158 ± 0.00330 | 0.322 | 67.0 | 289.7 ± 6.9 | 86.9 |

| 950 | 898.5 | 48.3 ± 0.1 | 0.04831 ± 0.00068 | 0.07979 ± 0.00307 | 0.02287 ± 0.00132 | 0.287 | 75.3 | 285.2 ± 3.8 | 86.0 |

| 1050 | 1654.5 | 47.6 ± 0.1 | 0.02852 ± 0.00071 | 0.04228 ± 0.00164 | 0.01602 ± 0.00143 | 0.152 | 90.7 | 293.2 ± 4.0 | 90.1 |

| 1090 | 804.4 | 47.7 ± 0.1 | 0.04002 ± 0.00127 | 0.06076 ± 0.00257 | 0.01650 ± 0.00153 | 0.219 | 98.2 | 293.1 ± 4.1 | 89.8 |

| 1130 | 194.5 | 48.5 ± 0.4 | 0.13083 ± 0.00451 | 0.16040 ± 0.01004 | 0.02136 ± 0.00868 | 0.577 | 100.0 | 288.8 ± 16.6 | 87.0 |

| Sample B-23-146 muscovite, weight 56.52 mg, J = 0.004528 ± 0.000054 1, plateau age (540–1130 °C) = 289.1 ± 3.5 Ma (1σ) | |||||||||

| 550 | 58.1 | 70.4 ± 1.0 | 0.07549 ± 0.01069 | 5.97844 ± 0.15611 | 0.19980 ± 0.01286 | 21.522 | 1.0 | 81.0 ± 26.2 | 16.3 |

| 650 | 152.0 | 106.8 ± 0.5 | 0.02627 ± 0.00522 | 0.67446 ± 0.03905 | 0.23315 ± 0.00191 | 2.428 | 2.8 | 256.8 ± 5.0 | 35.6 |

| 750 | 478.5 | 66.7 ± 0.1 | 0.01776 ± 0.00310 | 0.06931 ± 0.03274 | 0.07116 ± 0.00179 | 0.249 | 11.9 | 304.7 ± 4.4 | 68.5 |

| 825 | 906.9 | 60.9 ± 0.1 | 0.01377 ± 0.00175 | 0.05460 ± 0.01719 | 0.05143 ± 0.00134 | 0.197 | 30.8 | 305.3 ± 3.9 | 75.1 |

| 910 | 745.1 | 55.6 ± 0.2 | 0.01799 ± 0.00339 | 0.00549 ± 0.01820 | 0.03006 ± 0.00323 | 0.020 | 47.8 | 311.3 ± 6.7 | 84.0 |

| 985 | 1011.3 | 55.5 ± 0.1 | 0.01475 ± 0.00121 | 0.00360 ± 0.01646 | 0.03622 ± 0.00167 | 0.013 | 70.8 | 299.5 ± 4.3 | 80.7 |

| 1055 | 1123.9 | 63.8 ± 0.1 | 0.01787 ± 0.00388 | 0.00461 ± 0.02962 | 0.06130 ± 0.00205 | 0.017 | 93.2 | 304.8 ± 4.8 | 71.6 |

| 1130 | 377.1 | 69.8 ± 0.1 | 0.02801 ± 0.00591 | 0.02533 ± 0.02013 | 0.08913 ± 0.00095 | 0.091 | 100.0 | 291.2 ± 3.4 | 62.3 |

References

- Zonenshain, L.P.; Kuz’min, M.I.; Natapov, L.M. Tectonics of the Lithospheric Plates of the USSR Territory; B.1; Nedra: Moscow, Russia, 1990; 327p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Shcherba, G.N.; Diyachkov, B.A.; Stuchevsky, N.I.; Nakhtigal, G.P.; Antonenko, A.N.; Lubetsky, V.N. Great Altai: Geology and Metallogeny. In Geological Construction; Book 1; Gylym: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1998; 304p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Yelkin, E.A.; Sennikov, N.V.; Buslov, M.M.; Yazikov, A.; Yu Grazianova, R.T.; Bakharev, N.L. Paleogeographic reconstructions of the western part of the Altai-Sayan region in the Ordovician, Silurian and Devonian and their geodynamic interpretation. Geol. I Geofiz. (Russ. Geol. Geophys.) 1994, 35, 118–145. [Google Scholar]

- Buslov, M.M.; Watanabe, T.; Smirnova, L.V.; Fujiwara, Y.; Iwata, K.; De Grave, J.; Semakov, N.N.; Travin, A.V.; Kir’ynova, A.P.; Kokh, D.A. Role of strike-slip faulting in Late Paleozoic–Early Mesozoic tectonics and geodynamics of the Altai–Sayan and East Kazakhstan regions. Geol. I Geofiz. (Russ. Geol. Geophys.) 2003, 44, 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Khromykh, S.V. Basic and Associated Granitoid Magmatism and Geodynamic Evolution of the Altai Accretion–Collision System (Eastern Kazakhstan). Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2022, 63, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berzin, N.A.; Dobretsov, N.L. Geodynamic evolution of Southern Siberia in Late Precambrian–Early Paleozoic time. In Reconstruction of the Paleoasian Ocean; VSP Int. Sci. Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 45–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mossakovsky, A.A.; Ruzhentsev, S.V.; Samygin, S.G.; Kheraskova, T.N. The Central Asian orogen: Geodynamic evolution and formation history. Geotektonika 1993, 6, 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Didenko, A.N.; Mossakovsky, A.A.; Pechersky, D.M.; Ruzhentsev, S.V.; Samygin, S.G.; Kheraskova, T.N. Geodynamics of the Paleozoic Oceans of Central Asia. Geol. I Geofiz. (Russ. Geol. Geophys.) 1994, 35, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Berzin, N.A.; Coleman, R.G.; Dobretsov, N.L.; Zonenshain, L.P.; Xuchang, X.; Chang, E.Z. Geodynamic map of the western part of the Paleoasian Ocean. Geol. I Geofiz. (Russ. Geol. Geophys.) 1994, 35, 8–28. [Google Scholar]

- Berzin, N.A.; Kungurtsev, L.V. Geodynamic interpretation of Altai– Sayan geological complexes. Geol. I Geofiz. (Russ. Geol. Geophys.) 1996, 37, 63–81. [Google Scholar]

- Dobretsov, N.L. Evolution of structures of the Urals, Kazakhstan, Tien Shan, and Altai–Sayan region within the Ural–Mongolian fold belt (Paleoasian ocean). Geol. I Geofiz. (Russ. Geol. Geophys.) 2003, 44, 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ermolov, P.V. Actual Problems of Isotopic Geology and Metallogeny of Kazakhstan; Publishing and Printing Center of the Kazakh-Russian University: Karaganda, Kazakhstan, 2013; p. 206. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Vladimirov, V.G.; Kruk, N.N.; Khromykh, S.V.; Polyansky, O.P.; Chervov, V.V.; Vladimirov, V.G.; Travin, A.V.; Babin, G.A.; Kuibida, M.L.; Khomyakov, V.D. Permian magmatism and lithospheric deformation in the Altai caused by crustal and mantle thermal processes. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2008, 49, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromykh, S.V.; Kotler, P.D.; Sokolova, E.N. Mantle-crust interaction at the late stage of evolution of Hercynian Altai collision system, Western part of CAOB. Geodyn. Tectonophys. 2017, 8, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sengör, A.M.C.; Natal’in, B.A.; Burtman, V.S. Evolution of the Altaid tectonic collage and Paleozoic crustal growth in Eurasia. Nature 1993, 36, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windley, B.F.; Alexeiev, D.; Xiao, W.; Kröner, A.; Badarch, G. Tectonic models for accretion of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Geol. Soc. Lond. 2007, 164, 31–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glorie, S.; De Grave, J.; Delvaux, D.; Buslov, M.M.; Zhimulev, F.I.; Vanhaecke, F.; Elburg, M.A.; Van den Haute, P. Tectonic history of the Irtysh shear zone (NE Kazakhstan): New constraints from zircon U/Pb dating, apatite fission track dating and palaeostress analysis. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 45, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.L.; Santosh, M.; Zou, H.B.; Xu, Y.G.; Zhou, G.; Dong, Y.G.; Ding, R.F.; Wang, H.Y. Revisiting the “Irtish tectonic belt”: Implications for the Paleozoic tectonic evolution of the Altai orogen. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2012, 52, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kröner, A.; Kovach, V.; Belousova, E.; Hegner, E.; Armstrong, R.; Dolgopolova, A.; Seltmann, R.; Alexeiev, D.V.; Hoffmann, J.E.; Wong, J.; et al. Reassessment of continental growth during the accretionary history of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. Gondwana Res. 2014, 25, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.J.; Huang, B.; Han, C.; Sun, S.; Li, J. A review of the western part of the Altaids: A key to understanding the architecture of accretionary orogens. Gondwana Res. 2010, 18, 253–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Windley, B.; Sun, S.; Li, J.; Huang, B.; Han, C.; Yuan, C.; Sun, M.; Chen, H. A tale of amalgamation of three collage systems in the Permian–Middle Triassic in Central-East Asia: Oroclines, sutures, and terminal accretion. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 43, 477–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Sun, M.; Rosenbaum, G.; Jourdan, F.; Li, S.; Cai, K. Late Paleozoic closure of the Ob-Zaisan Ocean along the Irtysh shear zone (NW China): Implications for arc amalgamation and oroclinal bending in the Central Asian orogenic belt. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2017, 129, B31541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buslov, M.M. Tectonics and geodynamics of the Central Asian Foldbelt: The role of Late Paleozoic large-amplitude strike-slip faults. Russ. Geol. Geophys. (Geol. I Geofiz.) 2011, 52, 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buslov, M.M.; Cai, K. Tectonics and geodynamics of the Altai-Junggar orogen in the Vendian-Paleozoic: Implications for the continental evolution and growth of the Central Asian fold belt. Geodyn. Tectonophys. 2017, 8, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buslov, M.M.; Shcerbanenko, T.A.; Kulikova, A.V.; Sennikov, N.V. Palaeotectonic reconstructions of the Central Asian folded belt in the Silurian Tuvaella and Retziella brachiopod fauna locations. Lethaia 2022, 55, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolov, P.V.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Izokh, A.E.; Polyansky, N.V.; Revyakin, P.S.; Bortsov, V.D. Orogenic Magmatism of Ophiolite Belts; Nauka: Novosibirsk, Russia, 1983; p. 206. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Buslov, M.M.; Fujiwara, Y.; Safonova, I.Y.; Okada, S.; Semakov, N.N. The junction zone of the Gorny Altai and Rudny Altai terranes: Structure and evolution. Geol. I Geofiz. (Russ. Geol. Geophys.) 2000, 41, 383–397 (377–390). [Google Scholar]

- Buslov, M.M.; Watanabe, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Iwata, K.; Smirnova, L.V.; Safonova, I.Y.; Semakov, N.N.; Kiryanova, A.P. Late Paleozoic faults of the Altai region, Central Asia: Tectonic pattern and model of formation. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2004, 23, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirajno, F. Intracontinental strike-slip faults, associated magmatism, mineral systems and mantle dynamics: Examples from NW China and Altay-Sayan (Siberia). J. Geodyn. 2010, 50, 325–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyachkov, B.A.; Bissatova, A.Y.; Mizernaya, M.A.; Zimanovskaya, N.A. Specific features of geotectonic development and ore potential in Southern Altai (Eastern Kazakhstan). Geol. Ore Depos. 2021, 63, 383–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travin, A.V.; Boven, A.; Plotnikov, A.V.; Vladimirov, V.G.; Tennisen, K.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Melnikov, A.I.; Titov, A.V. 40Ar/39Ar Dating of ductile deformations in the Irtysh Shear Zone, Eastern Kazakhstan. Geochem. Int. 2001, 39, 1237–1241. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Sun, M.; Rosenbaum, G.; Cai, K.; Chen, M.; He, Y. Transpressional deformation, strain partitioning and fold superimposition in the southern Chinese Altai, Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Struct. Geol. 2016, 87, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.; Han, C.; Yuan, C.; Sun, M.; Lin, S.; Chen, H.; Li, Z.; Li, J.; Sun, S. Middle Cambrian to Permian subduction-related accretionary orogenesis of North Xinjiang, NW China: Implications for the tectonic evolution of Central Asia. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2008, 32, 102–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Sun, M.; Rosenbaum, G.; Cai, K.; Yu, Y. Structural evolution of the Irtysh Shear Zone (northwestern China) and implications for the amalgamation of arc systems in the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Struct. Geol. 2015, 80, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Sun, M.; Rosenbaum, G.; Yuan, C.; Safonova, I.; Cai, K.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Geometry, kinematics and tectonic models of the Kazakhstan Orocline, Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2018, 153, 42–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Sun, M.; Yuan Ch Jourdan, F.; Hu, W.; Jiang, Y. Late Paleozoic tectonic transition from subduction to collision in the Chinese Altai and Tianshan (Central Asia): New geochronological constraints. Am. J. Sci. 2021, 321, 178–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.L.; Zou, H.B.; Yao, C.Y.; Dong, Y.G. Origin of permian gabbroic intrusions in the southern margin of the Altai Orogenic belt: A possible link to the permian tarim mantle plume? Lithos 2014, 204, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromykh, S.V.; Tsygankov, A.A.; Kotler, P.D.; Navozov, O.V.; Kruk, N.N.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Travin, A.V.; Yudin, D.S.; Burmakina, G.N.; Khubanov, V.B.; et al. Late paleozoic granitoid magmatism of Eastern Kazakhstan and Western Transbaikalia: Plume model test. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2016, 57, 773–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navozov, O.V.; Solyanik, V.P.; Klepikov, N.A.; Karavaeva, G.S. Unsolved problems concerning the spatial and genetic relationship between some types of mineral resources and the intrusions of the Kalba–Narym and West Kalba zones of the Great Altai. Geol. Conserv. Miner. Resour. 2011, 4, 66–72. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Pirajno, F.; Ernst, R.E.; Borisenko, A.S.; Fedoseev, G.; Naumov, E.A. Intraplate magmatism in central Asia and China and associated metallogeny. Ore Geol. Rev. 2009, 35, 114–136. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Han, B.F.; Ji, J.Q.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.; He, G.Q.; Wang, T. Zircon U-Pb ages and tectonic implications of Paleozoic plutons in northern West Junggar, North Xinjiang, China. Lithos 2010, 115, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, G.V.; Izokh, A.E.; Borisenko, A.S. Permian ultramafic-mafic magmatism and accompanying Cu-Ni mineralization in the Gobi-Tien Shan belt as a result of the Tarim plume activity. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2008, 49, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, R.E. Large Igneous Provinces; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014; 653p. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.Q.; Li, Z.L.; Yu, X.; Langmuir, C.H.; Santosh, M.; Yang, S.F.; Chen, H.L.; Tang, Z.L.; Song, B.A.; Zou, S.Y. Origin of the Early Permian zircons in Keping basalts and magma evolution of the Tarim Large Igneous Province (northwestern China). Lithos 2014, 204, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarmolyuk, V.V.; Kuzmin, M.I.; Ernst, R.E. Intraplate geodynamics and magmatism in the evolution of the Central Asian Orogenic Belt. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2014, 93, 158–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobretsov, N.L. Early Paleozoic tectonics and geodynamics of Central Asia: Role of mantle plumes. Russ. Geol. Geophys. (Geol. I Geofiz.) 2011, 52, 1539–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromykh, S.V.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Izokh, A.E.; Travin, A.V.; Prokop’ev, I.R.; Azimbaev, E.; Lobanov, S.S. Petrology and geochemistry of gabbro and picrites from the Altai collisional system of Hercynides: Evidence for the activity of the Tarim plume. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2013, 54, 1288–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermolov, P.V.; Polyansky, N.V. Metamorphic complexes of the junction zone of the Rudny Altai and the rare-metal Kalba. Geol. Geophys. 1980, 3, 49–57. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Bespaev, K.A.; Polyansky, N.V.; Ganjenko, G.D.; Dyachkov, B.A.; Evtushenko, O.P.; Li, T.D. Geology and Metallogeny of South-Western Altai (Within the Territory of Kazakhstan and China); Gylym: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1997; 288p. [Google Scholar]

- Khoreva, B.Y. Geological Structure, Intrusive Magmatism and Metamorphism of the Irtysh Shear Zone; Gosgeoltekhizdat: Moscow, Russia, 1963; 206p. [Google Scholar]

- Chikov, B.M.; Zinoviev, S.V. Post-Hercynian (Early Mesozoic) collisional structures of Western Altai. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 1996, 37, 61. [Google Scholar]

- Buslov, M.M.; Geng, H.; Travin, A.V.; Otgonbaatar, D.; Kulikova, A.V.; Chen, M.; Stijn, G.; Semakov, N.N.; Rubanova, E.S.; Abildaeva, M.A.; et al. Tectonics and geodynamics of Gorny Altai and adjacent structures of the Altai-Sayan folded area. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2013, 54, 1250–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, S.M.; Yin, A.; Manning, C.E.; Chen, Z.L.; Wang, X.F.; Grove, M. Late Paleozoic tectonic history of the Ertix Fault in the Chinese Altai and its implications for the development of the Central Asian Orogenic System. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2007, 119, 944–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinov’ev, S.V.; Travin, A.V. The problem of dynamometamorphic transformations of rocks and ores of the upper part of the Ridder Sokol’noye deposit (Rudnyi Altai). Dokl. Earth Sci. 2012, 444, 738–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodges, K.V. Geochronology and Thermochronology in Orogenic Systems. Treatise Geochem. 2004, 3, 263–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, T.A. Crustal Thermal Processes and the Interpretation of Thermochronometer Data. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 2005, 58, 315–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travin, A.V. Thermochronology of Early Paleozoic collisional and subductioncollisional structures of Central Asia. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2016, 57, 434–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travin, A.V.; Buslov, M.M.; Bishaev, Y.A.; Tsygankov, A.A.; Mikheev, E.I. Late Paleozoic–Cenozoic Tectonothermal Evolution of Transbaikalia: Thermochronology of the Angara–Vitim Granitoid Batholith. Russ. Geol. Geophys. 2023, 64, 1086–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobretsov, N.L.; Borisenko, A.S.; Izokh, A.E.; Zhmodik, S.M. Thermochemical model of Permian mantle plumes of Eurasia as a basis for identifying patterns of formation and prediction of copper-nickel, noble and rare metal deposits. Geol. Geophys. 2010, 51, 1159–1187. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.D.; Khromykh, S.V.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Navozov, O.V.; Travin, A.V.; Karavaeva, G.S.; Murzintsev, N.G. New data on the age and geodynamic interpretation of the Kalba-Narym granitic batholith, eastern Kazakhstan. Dokl. Earth Sci. 2015, 462, 565–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khromykh, S.V.; Izokh, A.E.; Gurova, A.V.; Cherdantseva, M.V.; Savinsky, I.A.; Vishnevsky, A.V. Syncollisional gabbro in the Irtysh shear zone, Eastern Kazakhstan:nCompositions, geochronology, and geodynamic implications. Lithos 2019, 346–347, 105144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.G.; Wei, X.; Luo, Z.Y.; Liu, H.Q.; Cao, J. The early permian tarim large Igneous Province: Main characteristics and a plume incubation model. Lithos 2014, 204, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatnikov, V.V.; Izokh, E.P.; Ermolov, P.V.; Ponomareva, A.P.; Stepanov, A.S. Magmatism and Metallogeny of the Kalba-Narym Zone, Eastern Kazakhstan; Nauka: Moscow, Russia, 1982; p. 248. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Dyachkov, B.A.; Mayorova, N.P.; Shcherba, G.N.; Abdrakhmanov, K.A. Granitoid and Ore Formations of the Kalba-Narym Belt: Ore Altai; Gylym: Almaty, Kazakhstan, 1994; 208p. [Google Scholar]

- Savinskiy, I.A.; Vladimirov, V.G.; Sukhorukov, V.P. Chechek granite-gneiss structure (Irtysh shear zone). Geol. I Pol. Iskop. Sib. 2015, 1, 15–22, (In Russian with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Savinskiy, I.A. Composition and isotopic characteristic of gneyss-granit of the Chechek Dome structure (Irtysh Shear Zone, East Kazakhstan). Lithosphere 2016, 5, 81–90. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.D.; Khromykh, S.V.; Kruk, N.N.; Sun, M.; Li, P.; Khubanov, V.B.; Semenova, D.V.; Vladimirov, A.G. Granitoids of the Kalba batholith, Eastern Kazakhstan: U–Pb zircon age, petroge nesis and tectonic implications. Lithos 2021, 388–389, 108056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mar'in, A.M.; Nazarov, G.V.; Tkachenko, G.G.; Shulikov, E.S. Geological Position and Age of Gabbro Intrusions in the Irtysh Fold Zone. Magmatism, Geochemistry and Metallogeny of Rudny Altai; Nauka: Alma-Ata, Russia, 1966; pp. 32–45. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Kuzebny, V.S.; Vladimirov, A.G.; Ermolov, P.V.; Mar'in, A.M. Main types of gabbro intrusions in Zaisan folded system. In Mafic-Ultramafic Complexes of Siberia; Nauka: Novosibirsk, Russia, 1979; pp. 166–196. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Saetgaleeva, Y.; Kotler, P.D.; Kulikova, A.V. Thermal History of the Sibinsky Granitoid Massif (East Kazakhstan) According To Track Dating Data Apatite. In Proceedings of the XXX All-Russian Youth Conference Structure of the Lithosphere and Geodynamics, Irkutsk, Russia, 16–21 May 2023; Institute of the Earth’s Crust SB RAS: Irkutsk, Russia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, K. Isoplot 3.00: A Geochronological Toolkit for Microsoft Excel; Berkeley Geochronology Center: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2003; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- Fleck, R.J.; Sutter, J.F.; Elliot, D.H. Interpretation of discordant 40Ar/39Ar age-spectra of Mesozoic tholeiites from Antarctica. Geoch. Cosm. Acta 1977, 41, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Godard, V.; Liu-Zeng, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, Z.; Xu, S.; Yao, W.; Yuan, Z.; Aumaitre, G.; Bourlès, D.L.; et al. Tectonic controls on surface erosion rates in the Longmen Shan, Eastern Tibet. Tectonics 2021, 40, e2020TC006445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Cluzel, D.; Jahn, B.-M.; Shu, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhai, Y.; Branquet, Y.; Barbanson, L.; Sizaret, S. Late paleozoic pre- and syn-kinematic plutons of the Kangguer–Huangshan Shear zone: Inference on the tectonic evolution of the eastern Chinese north Tianshan. Am. J. Sci. 2014, 314, 43–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Wang, T.; Jahn, B.M.; Sun, M.; Hong, D.W.; Gao, J.F. Post-accretionary permian granitoids in the Chinese Altai orogen: Geochronology, petrogenesis and tectonic implications. Am. J. Sci. 2014, 314, 80–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.J.; Chung, S.L.; Hawkesworth, C.J.; Cawood, P.A.; Wang, Q.; Wyman, D.A.; Xu, Y.G.; Zhao, Z.H. Short episodes of crust generation during protracted accretionary processes: Evidence from Central Asian Orogenic Belt, NW China. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2017, 464, 142–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Li, P.; Rosenbaum, G.; Liu, J.; Jourdan, F.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, C.; Sun, M. Structural evolution of the eastern segment of the Irtysh shear zone: Implications for the collision between the east Junggar Terrane and the Chinese Altai orogen (northwestern China). J. Struct. Geol. 2020, 139, 104126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample/ Massif | Complex/ Rock/Mineral * | Method ** | Age (Ma) | Closure/ Formation T (°C) *** | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-1052 | Kalgutin/ granodiorite/zrn | U/PbL | 308 ± 2 | ~850f | [38] |

| X-1052 Kurchum | Kalgutin/ granodiorite/bt | 40Ar/39Ar | 289 ± 3 | 330c | This work |

| X-1047 | Kalgutin/ granodiorite/zrn | U/PbL | 303 ± 1 | ~850f | [38] |

| X-1047 Kurchum | Kalgutin/ granodiorite/bt | 40Ar/39Ar | 282 ± 3 | 330c | This work |

| X-1056 | Kalba/granite/zrn | U/PbL | 297 ± 1 | ~806f | [38] |

| X-1056/ Asubulak | Kalba/granite/bt | 40Ar/39Ar | 285 ± 2 | 330c | This work |

| X-1045 | Kalba/granodiorite/zrn | U/PbL | 297 ± 1 | ~806f | [38] |

| X-1045 Chernovin | 40Ar/39Ar | 281 ± 2 | 330c | This work | |

| X-1042 | Kalba/granite/zrn | U/PbL | 286 ± 3 | ~806f | [38] |

| X-1042 Chernovin | Kalba/granite/bt | 40Ar/39Ar | 268 ± 2 | 330c | This work |

| Narym | Kalba/granite/zrn | U/PbL | 296 ± 4 | ~806f | [5] |

| 2458 | Kalba/granite/bt | 40Ar/39Ar | 275 ± 3 | 330c | This work |

| 2463 | Kalba/granite/bt | 40Ar/39Ar | 283 ± 3 | 330c | This work |

| X-1044 | Kalba/granite/zrn | U/PbL | 288 ± 1 | ~806f | [38] |

| X-1044 Chernovin | Kalba/granite/bt | 40Ar/39Ar | 282 ± 2 | 330c | This work |

| X-1041 | Monastery/ leucogranite/zrn | U/PbL | 283 ± 2 | ~810f | [38] |

| X-1041 Voylochev | Monastery/ leucogranite/bt | 40Ar/39Ar | 285 ± 2 | 330c | This work |

| 8-03-10 Sebin | Monastery/ leucogranite/zrn | U/PbL | 284 ± 4 | ~810f | [38] |

| KA-14-18 | Monastery/ leucogranite/bt | 40Ar/39Ar | 280 ± 2 | 330c | This work |

| KA-14-18 Sebin | Monastery/ leucogranite/fsp | 40Ar/39Ar | 243 ± 3 | 250c | This work |

| KA-21-345 KA-21-346 KA-21-347 Sebin | Monastery/ leucogranite/ap | FST | Average 229 ± 21 | 110c | [70] |

| X-1414 Surov intrusion | Irtysh/gabbronorite/zrn | U/PbL | 313 ± 1 | >900f | [61] |

| X-1207 Surov intrusion | Irtysh/gabbrodiorite/zrn | U/PbL | 313 ± 1 | >900f | [61] |

| E-32 Chechek | Chechek/granite-gneiss/ms | 40Ar/39Ar | 312 ± 3 | 360c | [65] |

| KZ-06 Chechek | Chechek/granite-gneiss/ap | FST | 87 ± 6 | 110c | [17] |

| B-23-146 | Chechek/gabbro tectonite/ms | 40Ar/39Ar | 304 ± 4 | 360c | This work |

| B-23-146 Surov intrusion | Chechek/gabbro tectonite/bt | 40Ar/39Ar | 289 ± 3 | 330c | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Travin, A.; Buslov, M.; Murzintsev, N.; Korobkin, V.; Kotler, P.; Khromykh, S.V.; Zindobriy, V.D. Thermochronology of the Kalba–Narym Batholith and the Irtysh Shear Zone (Altai Accretion–Collision System): Geodynamic Implications. Minerals 2025, 15, 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030243

Travin A, Buslov M, Murzintsev N, Korobkin V, Kotler P, Khromykh SV, Zindobriy VD. Thermochronology of the Kalba–Narym Batholith and the Irtysh Shear Zone (Altai Accretion–Collision System): Geodynamic Implications. Minerals. 2025; 15(3):243. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030243

Chicago/Turabian StyleTravin, Alexey, Mikhail Buslov, Nikolay Murzintsev, Valeriy Korobkin, Pavel Kotler, Sergey V. Khromykh, and Viktor D. Zindobriy. 2025. "Thermochronology of the Kalba–Narym Batholith and the Irtysh Shear Zone (Altai Accretion–Collision System): Geodynamic Implications" Minerals 15, no. 3: 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030243

APA StyleTravin, A., Buslov, M., Murzintsev, N., Korobkin, V., Kotler, P., Khromykh, S. V., & Zindobriy, V. D. (2025). Thermochronology of the Kalba–Narym Batholith and the Irtysh Shear Zone (Altai Accretion–Collision System): Geodynamic Implications. Minerals, 15(3), 243. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030243