Sustainable Recovery of Lead from Secondary Waste in Chloride Medium: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Chemistry of Chloride Solutions

3. Lead Chloride Solubility

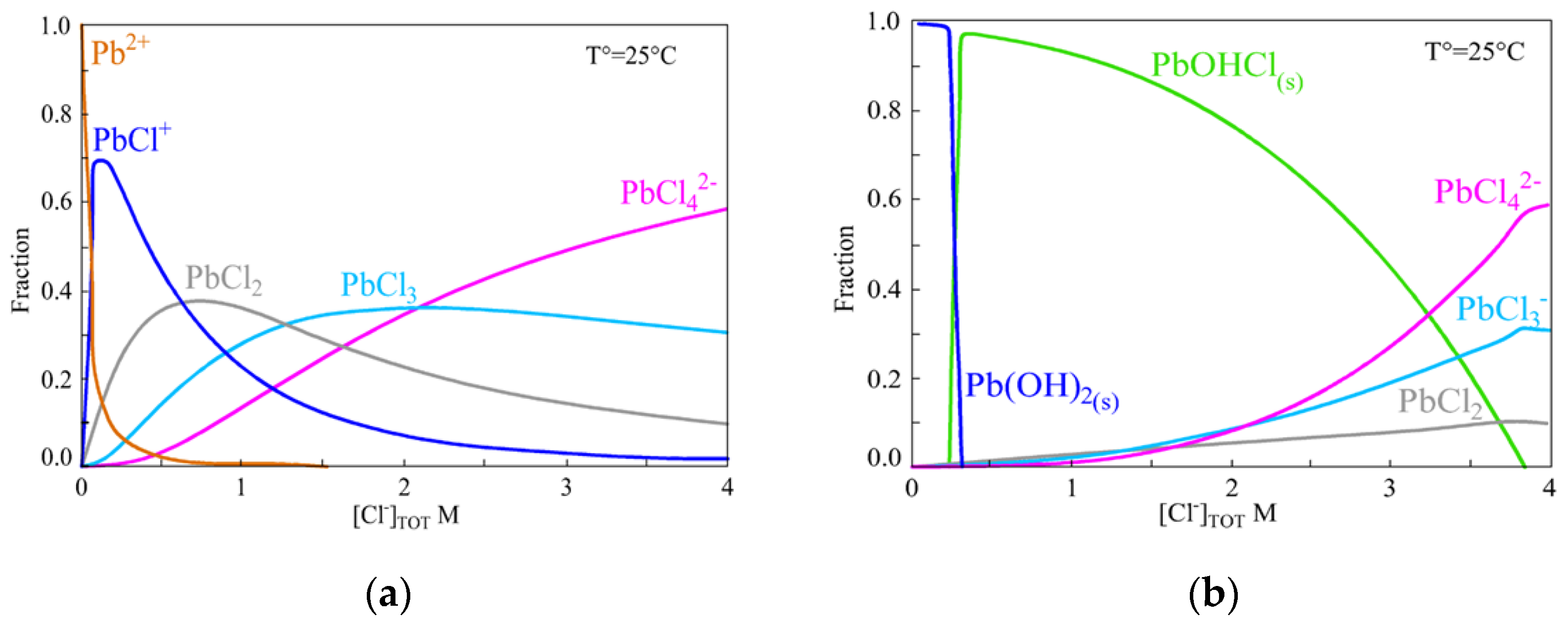

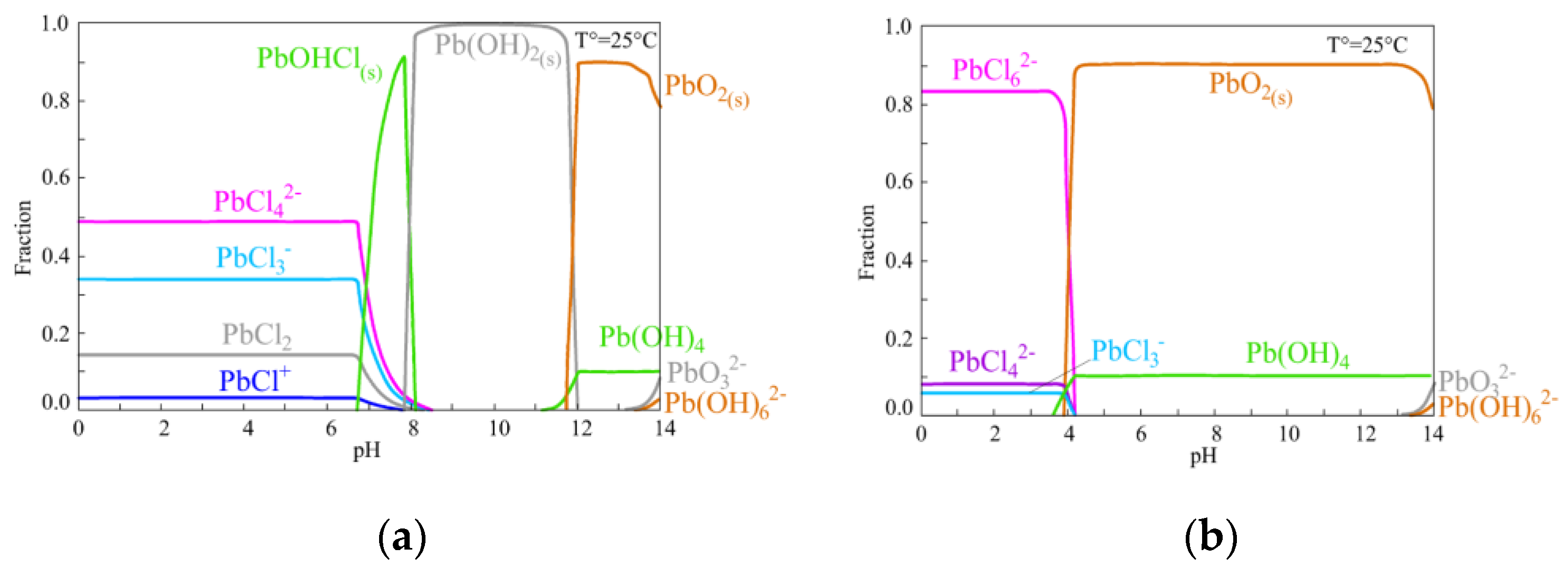

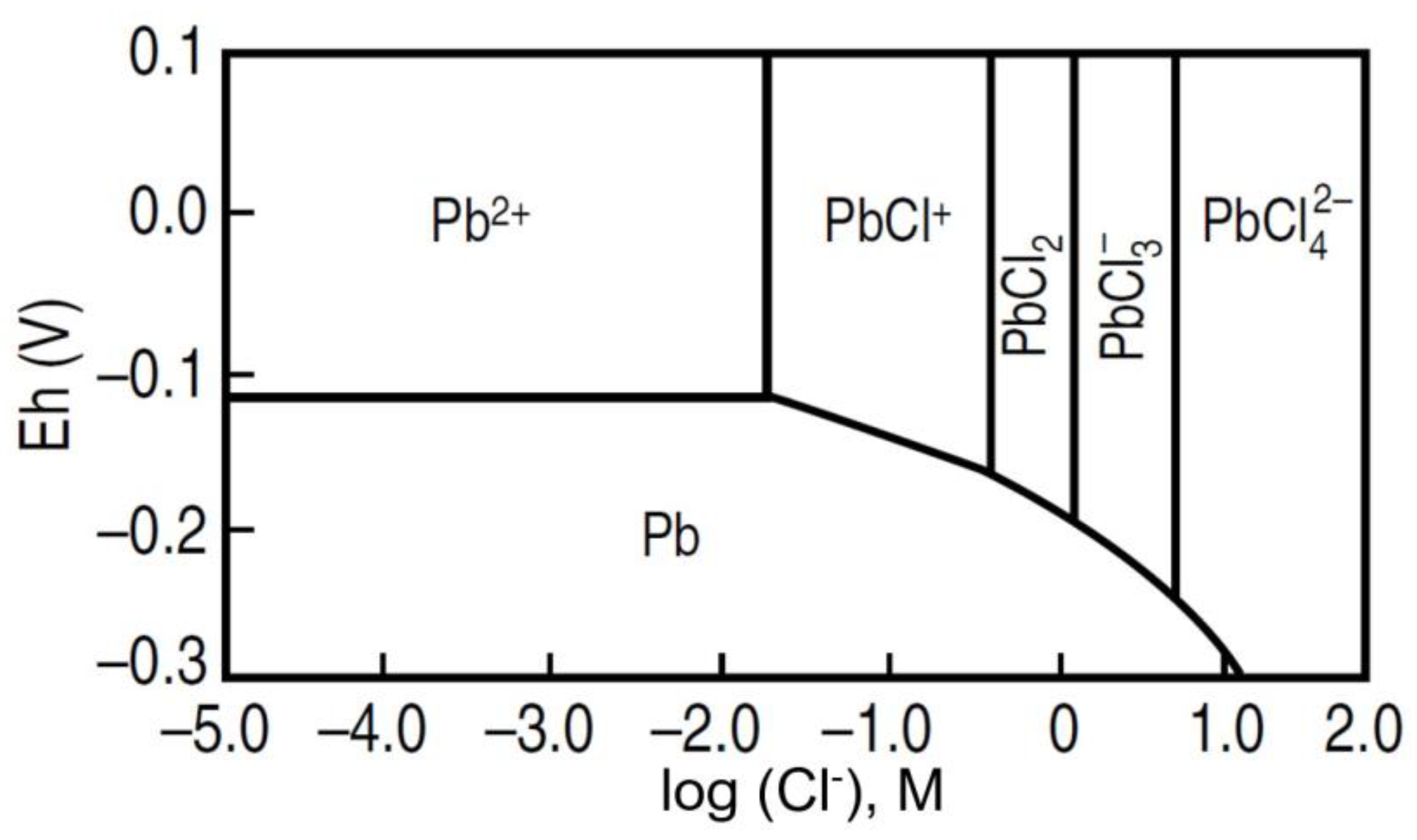

4. Lead–Chloride Complex

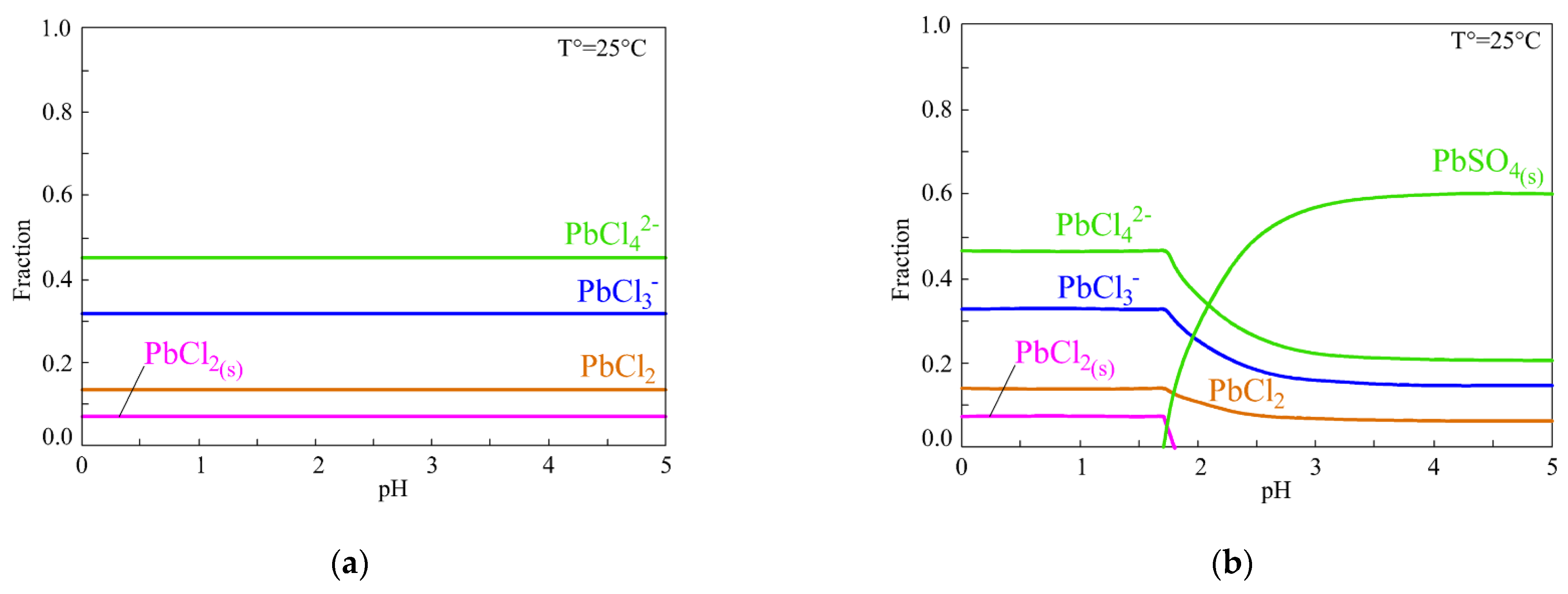

5. Effect of Lead–Chloride Complex Formation on the Reduction Potential

6. Lead Recovery from PbSO4 in Chloride Medium from Waste

6.1. Effect of Chloride Salts and Their Concentration

6.2. Influence of Acid Type and pH

6.3. Effect of Temperature

6.4. Effect of Reaction Time

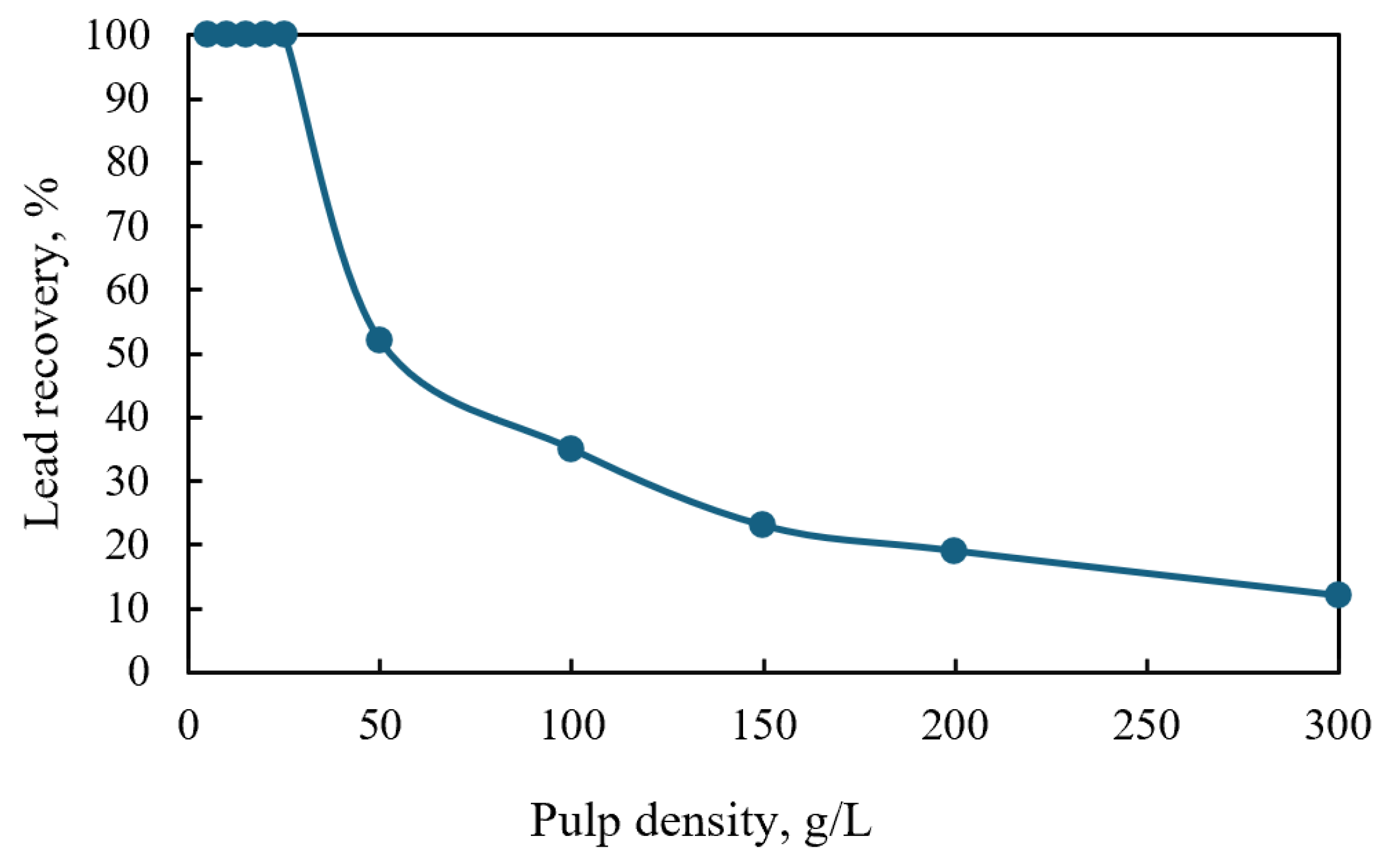

6.5. Effect of Pulp Density

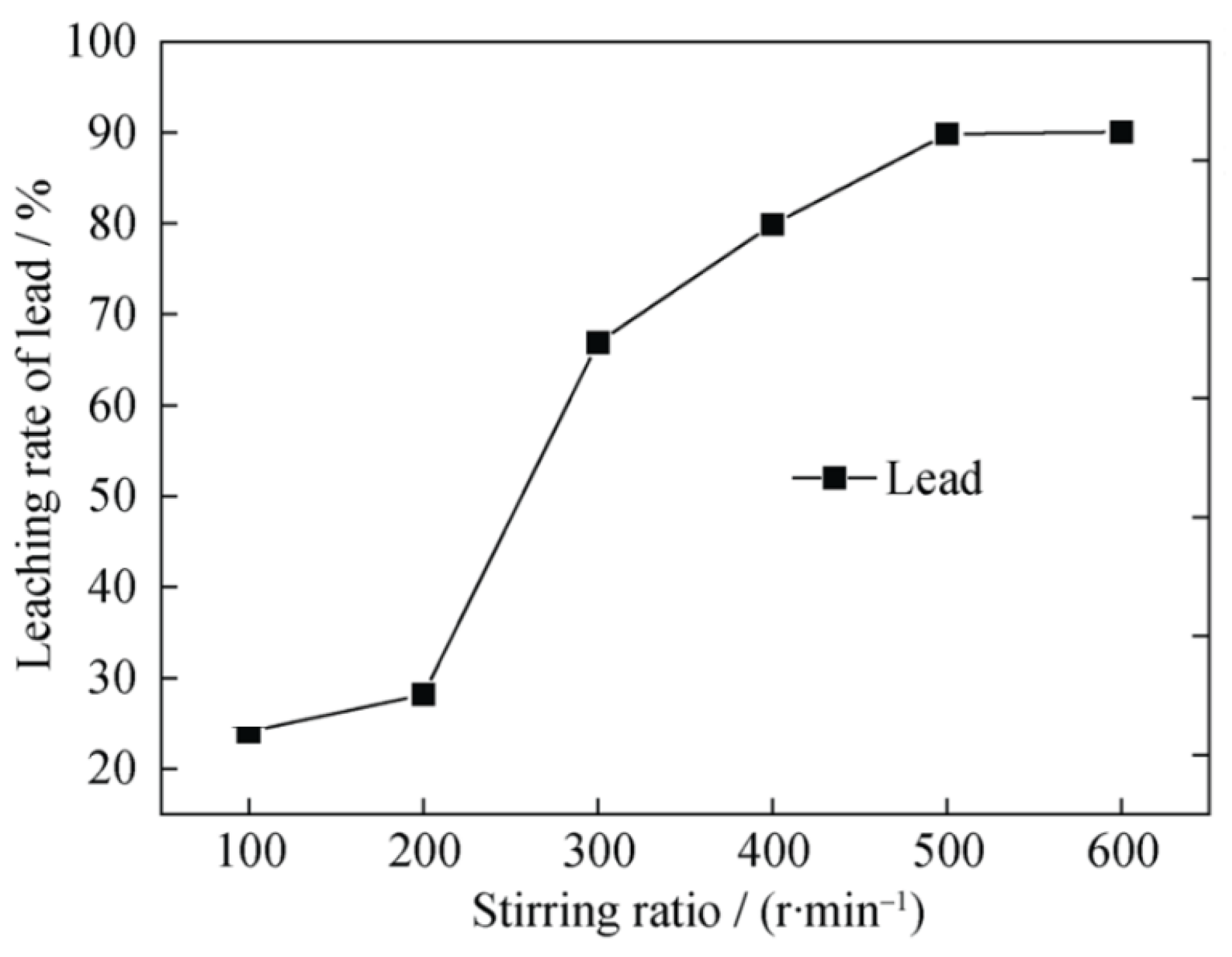

6.6. Effect of Stirring Speed

7. Kinetic Studies of the Dissolution of Lead Sulfate in Chloride Media

8. Lead Concentration Methods from Chloride Media

9. Implications of Future Sustainable Recovery of Lead from Secondary Waste

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Charkiewicz, A.E.; Backstrand, J.R. Lead Toxicity and Pollution in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Mu, L.; Guo, S.; Bi, Y. Lead Leaching Mechanism and Kinetics in Electrolytic Manganese Anode Slime. Hydrometallurgy 2019, 183, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruşen, A.; Sunkar, A.S.; Topkaya, Y.A. Zinc and Lead Extraction from Çinkur Leach Residues by Using Hydrometallurgical Method. Hydrometallurgy 2008, 93, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Mu, W.; Shen, H.; Liu, S.; Zhai, Y. Leaching of Lead from Zinc Leach Residue in Acidic Calcium Chloride Aqueous Solution. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2015, 22, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, G.; Andrews, D. Placid-A Clean Process for Recycling Lead from Batteries. JOM 1996, 48, 29–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracin, L.C.; Chácon-Sanhueza, A.E.; Davoglio, R.A.; Rocha, L.O.; Caffeu, D.J.; Fontanetti, A.R.; Rocha-Filho, R.C.; Biaggio, S.R.; Bocchi, N. Lead Recovery from a Typical Brazilian Sludge of Exhausted Lead-Acid Batteries Using an Electrohydrometallurgical Process. Hydrometallurgy 2002, 65, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichlas, Z.T.; Rustandi, R.A.; Mubarok, M.Z. Selective Nitric Acid Leaching for Recycling of Lead-Bearing Solder Dross. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 264, 121675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, J.; Tan, Q.; Peters, A.L.; Yang, C. Global Status of Recycling Waste Solar Panels: A Review. Waste Manag. 2018, 75, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.K.; Man, X.D.; Walsh, D.E. Lead Removal via Soil Washing and Leaching. JOM 2001, 53, 22–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, A.L.; Ara, A.; Usmani, J.A. Lead Toxicity: A Review. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2015, 8, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Wang, W.; Ye, B. Impacts of Lead/Zinc Mining and Smelting on the Environment and Human Health in China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2012, 184, 2261–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yang, J.; Wu, X.; Hu, Y.; Yu, W.; Wang, J.; Dong, J.; Li, M.; Liang, S.; Hu, J.; et al. A Critical Review on Secondary Lead Recycling Technology and Its Prospect. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 61, 108–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagos, G. Requerimientos y Desafíos Ambientales Para La Minería Chilena. In Inserción Global y Medio Ambiente; Centro de Investigación y Planificación del Medio Ambiente (CIPMA): Santiago, Chile, 2015; pp. 173–203. [Google Scholar]

- Ley 20920: Establece Marco para la Gestión de Residuos, la Responsabilidad Extendida del Productor y Fomento al Reciclaje. Available online: https://bcn.cl/2exlx (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Sinadinovic, D.; Kamberovic, Z.; Sutic, A. Leaching Kinetics of Lead from Lead (II) Sulphate in Aqueous Calcium Chloride and Magnesium Chloride Solutions. Hydrometallurgy 1997, 47, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, B.; Song, Q.; Chen, B.; Wang, C. Leaching Behavior of Lead and Silver from Lead Sulfate Hazardous Residues in NaCl-CaCl2-NaClO3 Media. JOM 2019, 71, 2388–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silwamba, M.; Ito, M.; Hiroyoshi, N.; Tabelin, C.B.; Hashizume, R.; Fukushima, T.; Park, I.; Jeon, S.; Igarashi, T.; Sato, T.; et al. Recovery of Lead and Zinc from Zinc Plant Leach Residues by Concurrent Dissolution-Cementation Using Zero-Valent Aluminum in Chloride Medium. Metals 2020, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COCHILCO. Proyección de Consumo de Agua en la Minería del Cobre 2020–2031; COCHILCO: Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Prengaman, R.D.; Mirza, A.H. Recycling Concepts for Lead-Acid Batteries. In Lead-Acid Batteries for Future Automobiles; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 575–598. ISBN 9780444637031. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, C.; Navarro, P.; Esquivel, E. Tratamiento Hidrometalúrgico de Borras Anódicas con EDTA. In Proceedings of the IBEROMET XI X CONAMET/SAM, Viña del Mar, Chile, 2–5 January 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Koppala, S.; Yin, S.; Li, S.; Yang, K.; Zhu, F. Efficient Recycling of Pb from Zinc Leaching Residues by Using the Hydrometallurgical Method. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 075505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Yang, J.; Liang, S.; Hou, H.; Hu, J.; Liu, B.; Kumar, R.V. Review on Clean Recovery of Discarded/Spent Lead-Acid Battery and Trends of Recycled Products. J. Power Sources 2019, 436, 226853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, P.; Wang, C.; Wang, L.; Ma, B.; Chen, Y. Hydrometallurgical Recovery of Lead from Spent Lead-Acid Battery Paste via Leaching and Electrowinning in Chloride Solution. Hydrometallurgy 2019, 189, 105134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrizac, J.E. The Dissolution of Galena in Ferric Chloride Media. Metall. Trans. B 1986, 17, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freza, S.; Kabir, M.; Anusiewicz, I.; Skurski, P.; Błazejowski, J. Ab Initio Studies of the Structure, Physicochemical Properties and Behavior of Lead Chlorides and Chloroplumbate Anions in Gaseous and Aqueous Phases. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2013, 1004, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awakura, Y.; Kamei, S.; Majima, H. A Kinetic Study of Nonoxidative Dissolution of Galena in Aqueous Acid Solution. Metall. Trans. B 1980, 11B, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez Yévenes, L. The Kinetics of the Dissolution of Chalcopyrite in Chloride Media. Ph.D. Thesis, Murdoch University, Perth, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Majima, H.; Awakura, Y. Measurement of the Activity of Electrolytes and the Application of Activity to Hydrometallurgical Studies. Metall. Trans. B 1981, 12B, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majima, H.; Awakura, Y.; Sato, T.; Michimoto, T. Activities of H+ and Cl− Ions in Concentrated Acidic Chloride Solutions. Denki Kagaku 1982, 50, 934–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalique, A.; Akram, A.; Ali, S.; Hafeez, A. Non-Oxidative Dissolution of Lead Sulphide in Hydrochloric Acid Solution. J. Chem. Soc. Pak. 2005, 27, 194–198. [Google Scholar]

- Winand, R. Chloride Hydrometallurgy. Hydrometallurgy 1991, 27, 285–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdich, R.G.; Lawson, G.J. The Solubility of Aqueous Lead Chloride Solutions. Hydrometallurgy 1987, 19, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, L. Z = 82, Plomo, Pb. Un Dulce Veneno Que Te Puede Volver Loco. An. Quím. RSEQ 2019, 2, 144. [Google Scholar]

- Behnajady, B.; Moghaddam, J.; Behnajady, M.A.; Rashchi, F. Determination of the Optimum Conditions for the Leaching of Lead from Zinc Plant Residues in NaCl-H2SO4-Ca(OH)2 Media by the Taguchi Method. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 3887–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmand, F.; Moradkhani, D.; Safarzadeh, M.S.; Rashchi, F. Brine Leaching of Lead-Bearing Zinc Plant Residues: Process Optimization Using Orthogonal Array Design Methodology. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 95, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creighton, J.A.; Woodward, L.A. Raman Spectrum of the Hexachloroplumbate Ion PbCl62− in Solution. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1962, 58, 1077–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storoniak, P.; Kabir, M.; Blazejowski, J. Infuence of Ion Size on the Stability of the Chloroplumbates Containing PbCl5− or PbCl62−. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2008, 93, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigdomenech, I. Make Equilibrium Diagrams Using Sophisticated Algorithms (MEDUSA), Inorganic Chemistry; Royal Institute of Technology: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nicol, M. Hydrometallurgy Theory; Elsevier: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; Volume 1, ISBN 978-0-323-99322-7. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan, R.; Mohanan, P.K.; Swarnkar, S.R. Hydrometallurgical Processing of Lead-Bearing Materials for the Recovery of Lead and Silver as Lead Concentrate and Lead Metal. Hydrometallurgy 2000, 58, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houshmand, A.R.; Azizi, A.; Bahri, Z. Recovery of Lead from the Leaching Residue Derived from Zinc Production Plant: Process Optimization and Kinetic Modeling. Geosystem Eng. 2024, 27, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, T.; Gibas, K.; Borowski, K.; Adamski, Z.; Wozniak, B.; Muszer, A. Chloride Leaching of Silver and Lead from a Solid Residue after Atmospheric Leaching of Flotation Copper Concentrates. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2017, 53, 893–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrizac, J.E. Sulphate Control in Chloride Leaching Processes. Hydrometallurgy 1989, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuñez, C.; Espiell, F.; Roca, A. Recovery of Copper, Silver and Zinc from Huelva (Spain) Copper Smelter Flue Dust by a Chloride Leach Process. Hydrometallurgy 1985, 14, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenspiel, O. Chemical Reaction Engineering, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0-471-25424-9. [Google Scholar]

- Geidarov, A.A.; Akhmedov, M.M.; Karimov, M.A.; Valiev, B.S.; Efendieva, S.G. Kinetics of Leaching of Lead Sulfate in Sodium Chloride Solutions. Russ. Metall. 2009, 2009, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Wang, H.B.; Wang, S. Direct Leaching of Molybdenum and Lead from Lean Wulfenite Raw Ore. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2019, 29, 2638–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, P.; Ma, B.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y. Extraction and Separation of Zinc, Lead, Silver, and Bismuth from Bismuth Slag. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2019, 55, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veintemillas-Verdaguer, S.; Rodríguez-Clemente, R.; Torrent-Burgues, J. Lead Chloride Crystal Growth from Boiling Solutions. J. Cryst. Growth 1993, 128, 1282–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, E.; Du, Z.; Shen, J.; Cheng, F. Facile Generation of Rod-like PbCl2 Crystals from Pb(II) Aqueous Solutions Induced by Aliquat 336 at Room Temperature. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2017, 92, 2410–2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyakov, N.K.; Atanasova, D.A.; Vassilev, V.S.; Haralampiev, G.A. Desulphurization of Damped Battery Paste by Sodium Carbonate and Sodium Hydroxide. J. Power Sources 2007, 171, 960–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olper, M.; Maccagni, M. Pb Battery Recycling New Frontiers in Paste Desulphurisation and Lead Production. In Lead and Zinc; The Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Johannesburg, South Africa, 2008; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yi, L.; Yang, L.; Huang, Y.; Zhou, W.; Bian, W. A New Pre-Desulphurization Process of Damped Lead Battery Paste with Sodium Carbonate Based on a “Surface Update” Concept. Hydrometallurgy 2016, 160, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prengaman, D.R. Recovering Lead from Batteries. JOM 1995, 47, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Li, S.; Guo, Z.; Xu, Z. Extraction of Lead from Electrolytic Manganese Anode Mud by Microwave Coupled Ultrasound Technology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 407, 124622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.S.; Shih, Y.J.; Huang, Y.H. Recovery of Lead from Smelting Fly Ash of Waste Lead-Acid Battery by Leaching and Electrowinning. Waste Manag. 2016, 52, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, L.D.; Etsell, T.H. The Cementation of Lead from Ammoniacal Ammonium Sulphate Solution. Hydrometallurgy 1998, 47, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzatu, T.; Ghica, G.V.; Petrescu, I.M.; Iacob, G.; Buzatu, M.; Niculescu, F. Studies on Mathematical Modeling of the Leaching Process in Order to Efficiently Recover Lead from the Sulfate/Oxide Lead Paste. Waste Manag. 2017, 60, 723–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zárate-Gutiérrez, R.; Lapidus, G.T. Anglesite (PbSO4) Leaching in Citrate Solutions. Hydrometallurgy 2014, 144–145, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, M.; Oliveri, D.; Ferrara, G.; Salvaggio, M.; Piazza, S.; Italiano, S.; Sunseri, C. Metallic Lead Recovery from Lead-Acid Battery Paste by Urea Acetate Dissolution and Cementation on Iron. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 96, 123–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Yang, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, X.; Xie, W.; Yang, J. PbSO4 Leaching in Citric Acid/Sodium Citrate Solution and Subsequent Yielding Lead Citrate via Controlled Crystallization. Minerals 2017, 7, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polaris Market Research Analysis. Hydrochloric Acid Market Share, Size, Trends, Industry Analysis Report, By Grade (Synthetic, By-Product); By Application Type; By End Use Industry; By Region; Segment Forecast, 2024–2032; Polaris Market Research: Dover, DE, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- BCC Publishing. Carboxylic Acids: Applications and Global Markets to 2022; BCC Research LLC: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rauld, J.; Montealegre, R.; Bustos, S.; Reyes, R.; Yañez, H.; Ruiz, M.; Neuburg, H.; Rojas, J.; Jo, M.; D’amico, J.; et al. Procedimiento Para Aglomerar Minerales de Cobre Chancados Fino, Mediante La Adición de Cloruro de Calcio y Ácido Sulfúrico y Procedimiento de Lixiviación Previa Aglomeración Del Mineral. Chilean Patent CL40891, 15 January 2001. [Google Scholar]

- CEC. Environmentally Sound Management of Spent Lead-Acid Batteries in North America: Technical Guidelines; Commission for Environmental Cooperation: Montreal, QC, Canada, 2016; ISBN 978-2-89700-104-9. [Google Scholar]

| PbSO4 Source | Pb Content (wt, %) | Leaching Agent | Concentration | Temperature | pH | Particle Size | Stirring Speed, RPM | Density Pulp | Leaching Time | Pb Recovery, % | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic | 68.3 | CaCl2 | 444 g/L | 80 °C | - | 12.5 μm | 125 | 303 g/L | 240 min | 95 | [15] |

| MgCl2 | 380 g/L | 60 min | 99 | ||||||||

| Zn residue | 25 | NaCl | 300 g/L | 30 °C | 2.0 | 150 μm | - | 20 g/L | 30 min | 92 | [40] |

| HCl | |||||||||||

| 15.5 | NaCl | 300 g/L | 95 °C | - | 68 μm | 250 | 50 g/L | 10 min | 98.90 | [3] | |

| HCl | 30 mL/L | ||||||||||

| 12.4 | NaCl | 300 g/L | 37 °C | 1.0 | P80 = 118 μm | 400 | 25 g/L | 30 min | 89.43 | [35] | |

| HCl | |||||||||||

| 14.4 | NaCl | 300 g/L | 70 °C | 2.0 | P80 = 88 μm | 700 | 25 g/L | 10 min | 78.94 | [34] | |

| HCl | |||||||||||

| 2.6 | CaCl2 | 400 g/L | 80 °C | 1.0 | <106 μm | 500 | 143 g/L | 45 min | 93.79 | [4] | |

| HCl | |||||||||||

| 14.1 | CaCl2 | 350 g/L | 45 °C | 2.0 | - | - | 63 g/L | 120 min | 85.78 | [21] | |

| 6.2 | NaCl | 175 g/L | 25 °C | - | P50 = 9.6 μm | 120 | 50 g/L | - | 72 | [17] | |

| HCl | 0.1 M | ||||||||||

| 3.4 | NaCl | 350 g/L | room | - | P90 = 150 μm | 300 | 10% | 90 min | 75.72 | [41] | |

| HCl | 2 M | ||||||||||

| Concentrate | 5.2 | NaCl | 233 g/L | 90 °C | - | - | 500 | 100 g/L | 600 min | 99.50 | [42] |

| H2SO4 | 0.05 M | ||||||||||

| O2 | 0.03 m3/h | ||||||||||

| Battery paste | 71.1 | CaCl2 | 400 g/L | 90 °C | 1.0 | <150 μm | 500 | 33 g/L | 120 min | 99.20 | [23] |

| Fe2+ | 5 g/L | ||||||||||

| HCl |

| PbSO4 Source | Leaching Medium | Temperature, °C | Rate-Determining Step | Activation Energy, kJ/mol | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Synthetic | CaCl2 | 25–80 | Mixed -Diffusion product layer | 31.0 | [15] |

| -Chemical reaction | 69.0 | ||||

| MgCl2 | 25–80 | Mixed -Diffusion | 15.0 | ||

| -Chemical reaction | 46.0 | ||||

| Intermediate residue | NaCl | 25–80 | Diffusion | 12.4 | [46] |

| Zn residue | CaCl2 | 35–65 | Diffusion | 17.6 | [21] |

| NaCl HCl | 25–60 | Diffusion product layer | 16.7 | [41] | |

| NaCl | 45–90 | Mixed control | 13.4 | [16] | |

| CaCl2 | |||||

| NaClO3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vivar, Y.; Velásquez-Yévenes, L.; Vargas, C. Sustainable Recovery of Lead from Secondary Waste in Chloride Medium: A Review. Minerals 2025, 15, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030244

Vivar Y, Velásquez-Yévenes L, Vargas C. Sustainable Recovery of Lead from Secondary Waste in Chloride Medium: A Review. Minerals. 2025; 15(3):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030244

Chicago/Turabian StyleVivar, Yeimy, Lilian Velásquez-Yévenes, and Cristian Vargas. 2025. "Sustainable Recovery of Lead from Secondary Waste in Chloride Medium: A Review" Minerals 15, no. 3: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030244

APA StyleVivar, Y., Velásquez-Yévenes, L., & Vargas, C. (2025). Sustainable Recovery of Lead from Secondary Waste in Chloride Medium: A Review. Minerals, 15(3), 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/min15030244