Abstract

The iron and steel industry is still dependent on fossil coking coal. About 70% of the total steel production relies directly on fossil coal and coke inputs. Therefore, steel production contributes by ~7% of the global CO2 emission. The reduction of CO2 emission has been given highest priority by the iron- and steel-making sector due to the commitment of governments to mitigate CO2 emission according to Kyoto protocol. Utilization of auxiliary carbonaceous materials in the blast furnace and other iron-making technologies is one of the most efficient options to reduce the coke consumption and, consequently, the CO2 emission. The present review gives an insight of the trends in the applications of auxiliary carbon-bearing material in iron-making processes. Partial substitution of top charged coke by nut coke, lump charcoal, or carbon composite agglomerates were found to not only decrease the dependency on virgin fossil carbon, but also improve the blast furnace performance and increase the productivity. Partial or complete substitution of pulverized coal by waste plastics or renewable carbon-bearing materials like waste plastics or biomass help in mitigating the CO2 emission due to its high H2 content compared to fossil carbon. Injecting such reactive materials results in improved combustion and reduced coke consumption. Moreover, utilization of integrated steel plant fines and gases becomes necessary to achieve profitability to steel mill operation from both economic and environmental aspects. Recycling of such results in recovering the valuable components and thereby decrease the energy consumption and the need of landfills at the steel plants as well as reduce the consumption of virgin materials and reduce CO2 emission. On the other hand, developed technologies for iron-making rather than blast furnace opens a window and provide a good opportunity to utilize auxiliary carbon-bearing materials that are difficult to utilize in conventional blast furnace iron-making.

1. Introduction

Iron and steel-making sector is one of the most important sectors due its great impact on the global growth and economy. The production rate of steel has sharply increased in the recent years [1]. However, the iron- and steel-making sector is one of the highest energy and carbon-consuming sectors [2]. About 70% of the total steel production relies directly on coal and coke inputs. Around 1.2 billion tonnes of coal are used globally for steel production, which is around 15% of the total coal consumption worldwide, which explains the high contribution of the sector in the global CO2 emission [3]. The ore based steel-making units like sintering, coke-making, and blast furnace (BF) facilities contribute together about 90% of the sector emission [4]. Recently, the reduction of CO2 emission has been given the highest priority within the iron and steel sector due to the commitment of governments to mitigate CO2 emission according to Kyoto protocol [5].

Therefore, an increasing attention has been recently paid on increasing the replacement rate of coke by more environmentally friendly alternative sources. Injection of pulverized coal into the BF is one of the most promising options to reduce the coke consumption. The efficient utilization of in-plant generated gases and fines as a source of heat and reducing agent can greatly enhance the overall efficiency of steel industry. The partial substitution of virgin fossil carbon, namely coal and coke, with H2-rich carbon-bearing waste materials like waste plastic and renewable and neutral carbon like biomass products represents one of few choices which could be in short and middle terms introduced to reduce the dependency on fossil carbon and reduce the CO2 emission [6].

Attempts to decrease dependency of metallurgical coke and consequently reduce the CO2 emission are for large extent based on the following approaches; (1) substituting coke with H2-rich carbon-bearing materials; (2) producing agglomerates from secondary resources; and (3) shifting the iron oxide reduction process toward lower carbon utilization

Continuous development connected to reducing coke consumption in, for example, the BF has been always under investigation. Such development resulted in a decrease in coke consumption by ~60% since 1960 [7]. Coke has been partially replaced by other alternative carbon sources (pulverized coal, natural gas, etc.) through the BF tuyeres over years and such replacement is now practiced in all modern BFs. Injection of other carbon sources including top gas of different processes, such as coke-making and steel-making, as well as carbon-bearing wastes has been tried, and even practiced in some cases [8]. Today, coke consumption is in the range of 286–320 kg/tHM and pulverized coal injection is in the range of 170–220 kg/tHM at the majority of the modern BFs [6].

The possibility to further reduce energy consumption and CO2 emission in the BF has been showed through use of reactive coke [9,10,11], ferro-coke [12,13], and coal composite agglomerate with or without the content of bio-coal [14,15,16]. Increased reactivity results in lowering the temperature in the furnace shaft which consequently leads to reduced coke consumption in the BF [17,18]. Further development connected to cutting or at least minimizing the CO2 emission by means of reducing the dependency on primary fossil carbon sources is still required due to the pressure set by the governments relevant to environmental regulations and post-Kyoto requirements. Although, there exists a great deal of research papers reporting on reducing coke consumption and, consequently, reduce CO2 emission, there are a few that summarize the most recent research relevant to the applications of carbon-bearing materials, including renewable and waste carbon-bearing sources in the iron-making sector. The paper provides relevant insights into development of new trends in the applications of carbon-bearing materials in iron- and steel-making.

The strategy adopted in the present review is as follows:

- The review starts by a brief description of the existing technologies of iron-making, including BF and alternative technologies.

- Conventional reducing agents (mainly coke) including production, its role in the BF iron-making and the most important required properties.

- Description of materials that have reduction potential (for example; carbon rich in-plant fines, waste plastic, and bio-based carbon materials)

2. The Making of Iron: An Overview

Iron ore reduction is the conversion of iron oxide minerals to metallic iron. There are several units in which the iron oxide can be converted into corresponding metallic form. The most common, and the one with highest production rate, is the BF which is basically dependent on high-quality metallurgical coke. In countries where coking coal is not available, a great interest was directed toward developing an iron ore reduction process which is independent of metallurgical coke. Other iron-making processes are for example rotary hearth furnace (RHF), shaft furnace or fluidized bed. They differ in nature of iron ore used, their physical and chemical properties, reducing agent, type of fuel used and even sometime the process concept. Additionally, the produced sponge iron differs from one to another. Table 1 shows some commercial iron-making processes and their feed requirements [19].

Table 1.

Some commercial iron-making processes and their feed requirements.

In this section, a brief description of the most common raw materials, iron-making technologies/routes will be given.

2.1. Raw Materials

The raw materials for ore based steelworks can be classified into four categories: (1) iron ore, (2) fluxes, (3) reductants and fuels, and (4) reverts. The characteristics of these materials strongly affect the process performance and the product quality.

2.1.1. Iron Ores

Iron ores include hematite, magnetite and goethite or mixture of them. Based on the shape, particle size and pretreatment, iron ores could be in form of iron ore lump, concentrate, pellets, or sinter. Iron ore lumps are roughly in the size range of 6 to 30 mm and can be charged directly to the BF. Iron ore lump is considered the lowest cost iron bearing material for the BF burden materials. In most cases and, to improve the iron-making process, the ores are upgraded through a series of crushing, milling, flotation, and magnetite separation processes. A concentrate with less gangue and higher Fe content is produced. The concentrate is either sintered or pelletized. Additives can be added during process to control the product composition for a specific purpose. If the ore concentrate contains Fe2+, in addition to sintering, it is also oxidized to Fe3+ during the induration process [20,21,22].

2.1.2. Carbon-Bearing Material

Carbon-bearing materials are used as chemical reducing agents and as source of energy in the iron-making processes. Coke is the major reductant in iron-making BF. In BF, Coke lumps with size 25–80 mm is charged in layers along with the iron burden. Coke is produced by carbonization of a mixture of coking coals in specific facility called coke oven. In this process, selected coals are crushed and ground into fine powder. The mix is then charged to the coke oven and the oven is heated to elevated temperature (approximately 1100 °C) in an oxygen deficit atmosphere. The coal is coked and most of the volatiles are released leaving behind a carbonaceous material with more than 90% solid carbon. The produced coke is then cooled and screened into the desired size fraction. The highly mechanical strength produced coke with high energy value provides the required heat, reducing gases, permeability, and the mechanical support required in the BF [20,21,22]. Other carbon-bearing materials that are today used in iron-making processes are coal, oil, natural gas and other hydrocarbons.

2.1.3. Fluxes

Fluxes are materials that are added to the iron burden in minor quantities during processing steps to adjust its physical and chemical properties to enhance and ensure smooth process performance and high-quality product. Additives are added to iron ore during sintering or pelletization to ensure a sinter/pellets with a good physical properties and high reducibility. Limestone is very common flux and it is used in iron ore sintering. It has a strong water adhering ability which makes it good for granulation of the sinter raw mix and, therefore, improves the sinter bed permeability and increases the productivity. Dolomite which is basically calcium magnesium carbonates provides the MgO for the BF slag formation. Olivine is also used as a flux in the iron-making processes. Using olivine as the MgO source shows better sinter strength and productivity than using dolomite. Moreover, to maintain the BF slag basicity at desired level, silica sand is usually added to the sinter raw mix and brought into the furnace within the sinter ore [20,21,22].

2.1.4. Reverts

During the iron and steel-making processes and other consequent processes dusts, sludges, slags, scales and slurries are produced. These residues in most cases (depending on the process) contain valuable carbon and iron and are worth to recover. However, their chemical and physical properties may not be favored by the process. In some cases, they require pretreatment to make their recovery possible [20,21,22].

2.2. Methods of Iron and Steel-making

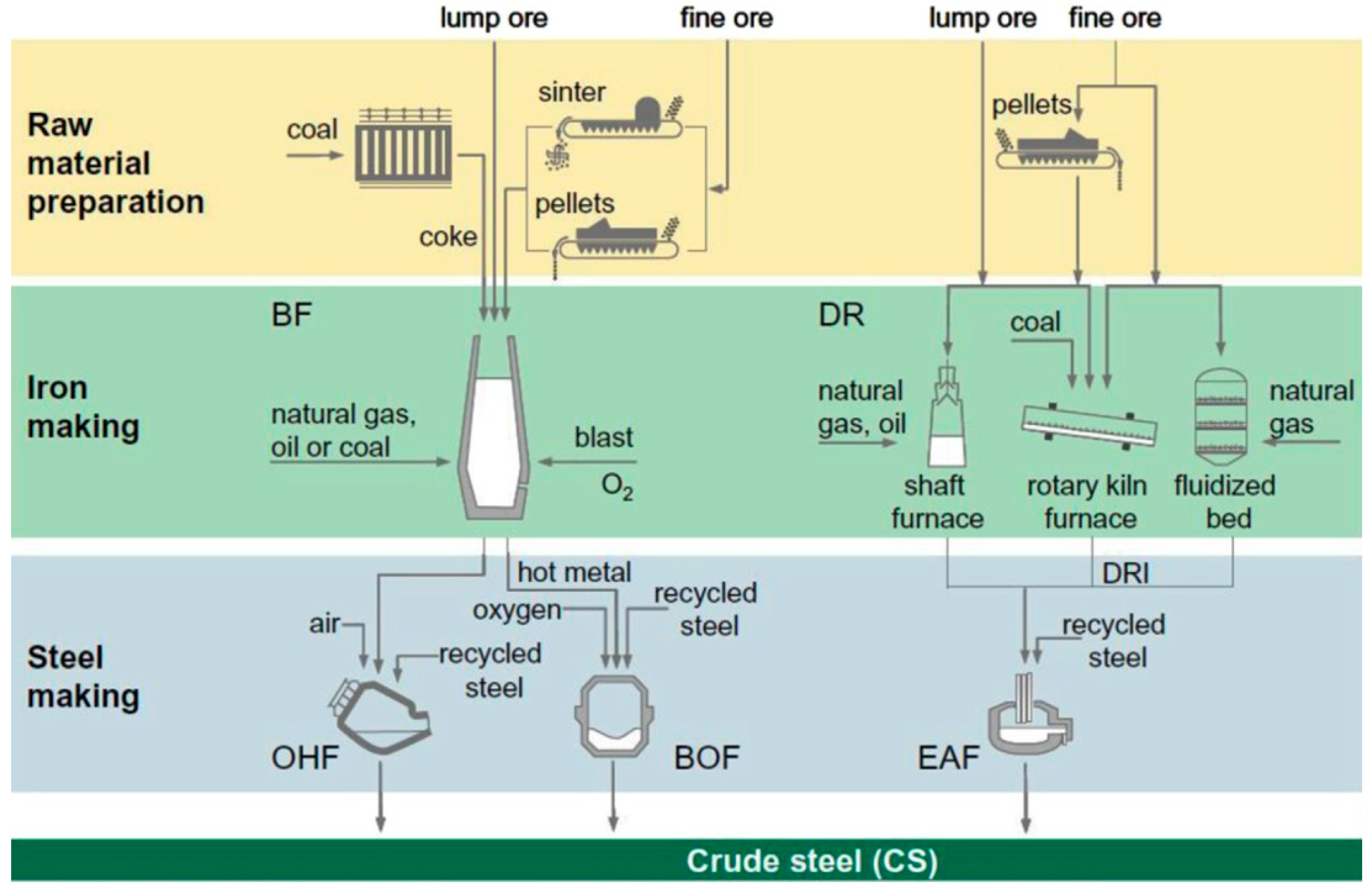

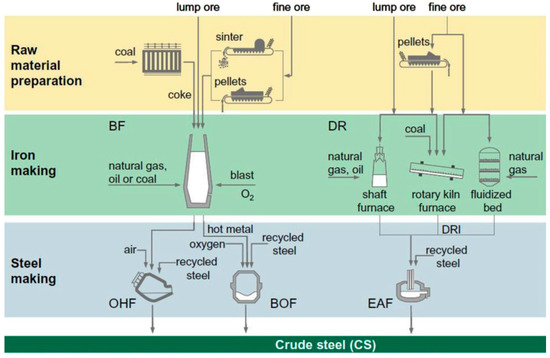

There are four basic routes commercially practiced for iron and steel production [23] (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of ore based steel-making routes (adopted with permission from [23]).

- The BF and the basic oxygen furnace (BOF) route; in this route coke and coal are the main carbon sources. Through this route approximately 70% of the world steel is being produced.

- Recycling of scrap through melting in electric arc furnace (EAF); through this route about 25% of the world steel is produced. Therefore, this route is considered the second important route for steel production.

- The direct reduction (DR) followed by smelting in EAF; by this route ~5% of the world steel is being produced and the most common used carbonaceous material in this case is natural gas.

- The smelting reduction followed by BOF; through this route only ~0.4% of the world steel is being produced. In this route neither ore preparation nor coking are needed.

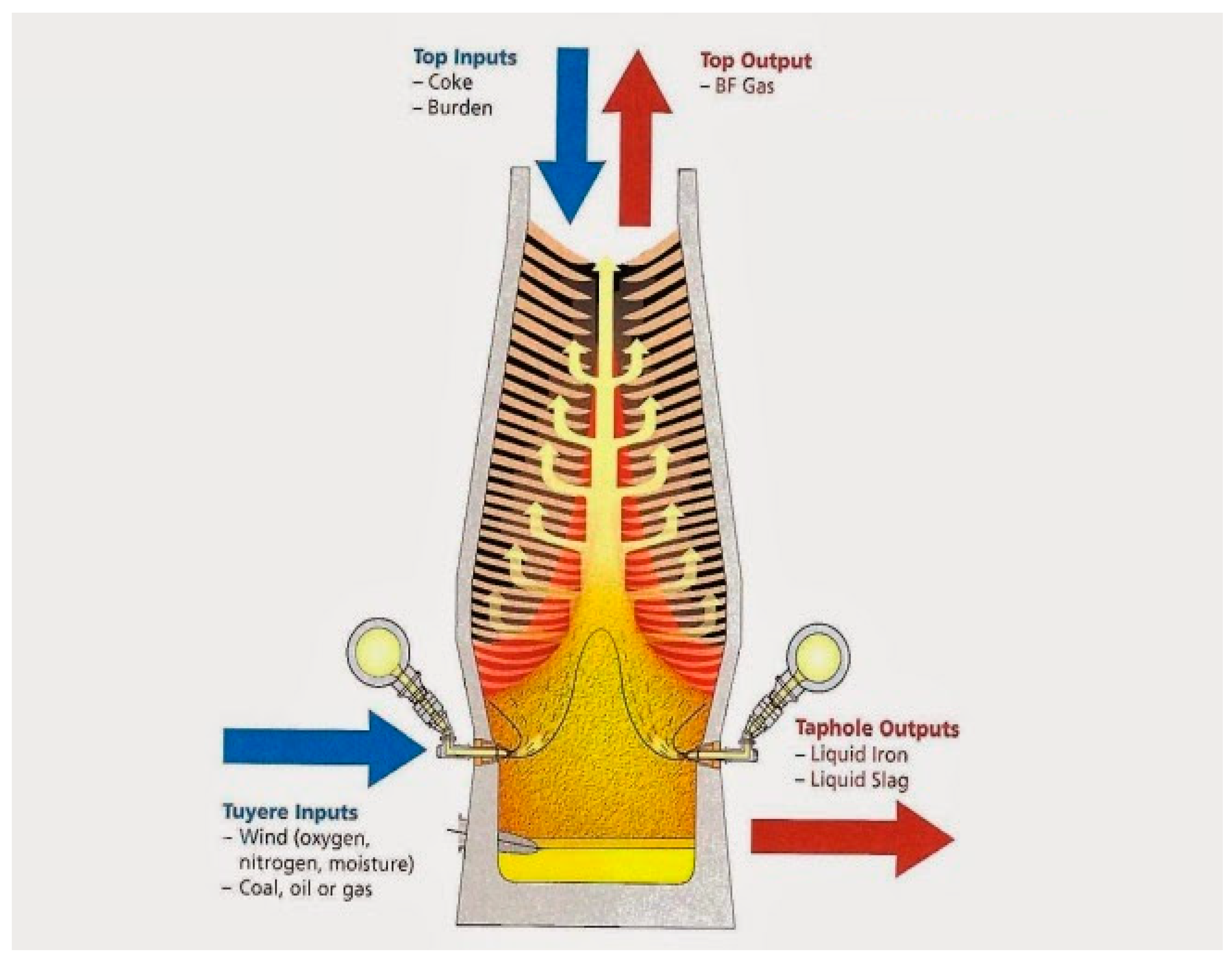

BF is the most common technology to produce iron with a share of ~70% of the total world steel production. In BF worldwide produced about 1155 million tonnes compared to 75 million tonnes via the DRI process [24]. For the foreseeable future and due to its high efficiency from both heat and mass exchange points of view, BF will continue to be the main iron-making reactor. The BF is an enormous vertical steel structure lined with refractory bricks. BF is a counter current heat exchanger and chemical reactor in which the iron bearing materials, carbon source, and fluxes are charged from the top and blast (pre-heated oxygen enriched air) is blown from the bottom. It takes 6–8 h for the charge material to descend through the furnace while it takes only 6–8 s for the blown blast to reach the furnace top.

Until the 18th century charcoal was the only reductant/fuel used in BFs, then coke (after invention in 1709) gradually replaced charcoal and BFs have grown considerably. The hearth diameter was 4–5 m with annual production rate of 100,000 t hot metal mostly from lump ore. Nowadays, BFs have hearth diameter up to 14–15 m with annual production rate of 3–4 million tonnes of hot metal. The largest known BF nowadays has an inner volume of 5800 m3 and annual production of 5.65 million tonnes HM [21]. The burden materials have changed from lump ore to more efficient materials, like sinter and/or pellets. The reductant materials have developed as well from 100% coke based operation to use other injectant materials through tuyeres. Attempts are also made to charge alternative reducing agents from the top along with burden materials like carbon composite agglomerates, etc. [16]. Modern BFs favor high Fe content in ore burden. Higher grade of iron ore burden can be realized after physical beneficiation process. Upwards of 70–80% of the modern BFs all over the world use sinter as the iron-bearing material while other BFs in Europe apply 100% iron ore pellets.

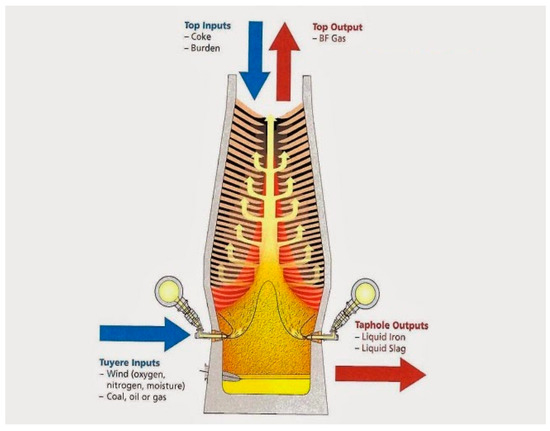

In a typical modern BF, the furnace is filled with alternating layers of coke and iron ore (sinter and/or pellets). Hot blast (compressed air) is blown into the BF through tuyeres. The hot blast gasifies coke and other carbon-bearing materials.

Figure 2 shows the major inputs and outputs of a typical modern BF.

Figure 2.

Input and output of modern BF (adopted with permission from [21]).

The quality demands for the BF burden materials include chemical composition as well as mechanical durability. The chemical composition must meet the end product properties. The mechanical durability of the burden is related to the material property in cold, hot, and during reduction to ensure the furnace permeability and, consequently, good performance and less operational difficulties. The reducibility of the iron ores is for large extent controlled by how easy the reducing gases can get into the iron oxide particles. The intrinsic reducibility of the burden material become less important factor if no sufficient gas is transported to the reaction front and the produced gas is moved away from the reaction site [19].

3. Conventional Carbon-Bearing Materials

Carbon-bearing materials are considered to be the major portion of iron-making cost and their production causes severe environmental concerns. The major challenge for the iron-making industry is the emission of greenhouse gases (GHG) from the use of fossil reductant (coke, coal, etc.). Coke is an inevitable material for the BF iron-making. It is known for its triple role in the BF (mechanical, carbon source, and energy supplier) [21]:

- Mechanical role: low reactive and strong coke descending along with the burden materials ensures good gas permeability and distribution, percolation of liquid iron and adsorption of dust. Moreover, left unreacted coke provides mechanical support for the descending materials.

- Source of carbon: coke along with other carbonaceous materials in the BF are responsible for producing reducing substances and hot metal carburization.

- Energy supplier: the combustion of carbonaceous materials including coke by hot blast in front of the tuyeres provides the majority of heat required in the BF.

Coke reactivity and coke strength after reaction are most important properties that determine the coke quality. Several factors affect the coke properties and consequently the chemical reactivity and the post-reaction strength. These factors include carbon microstructure, porosity, and pore structure, ash content, and ash composition and the blending coal ranking [25].

The total reducing agent rate in large BFs is around 460–520 kg/tHM of which 280–320 kg/tHM is coke. [26]. Coke consumption in BF has been a concern for many researchers and steel producers over the years. A lot of efforts have been made to partially replace coke with other carbon sources. Examples of these sources are pulverized coal, natural gas, oil [27,28], plastic, biomass and other resources derived from wastes [29,30]. Coal can be considered as a conventional carbon-bearing material since it has been practiced as injectant material for decades. One of the advantages of injected coal is its high hydrogen content which significantly helps in reducing the CO2 emission. However, injection of PC is limited due to the fact that PC is partially combusted in the raceway. The unburnt char ascends and accumulates in the cohesive zone which results in impairing the furnace permeability and consequently the furnace productivity. [31].

4. Alternative Carbon-Bearing Materials

Expected shortcut in the availability of coking coal, continued focus on energy consumption and GHG emissions as well as the need for best possible raw material utilization will make it necessary to continue the strive for making use of secondary and renewable resources within the process. The new carbon-bearing materials should maintain the following properties [21]:

- Low contents of sulfur, phosphorus, and alkali: sulfur and phosphorus removal in later process stages increases costs. Higher alkali content results in alkali accumulation and circulation in the furnace which not only attacks the refractory lining but also results in energy losses.

- Moisture content: moisture content should be kept minimum

- Volatile content: the volatile content in the carbon source should be controlled as it affects the gasification process in the raceway. Higher volatiles mean less replacement ratio for coke as well as low heating value.

- Controlled hardness or grindability

- High solid or fixed carbon content, low ash, and high heating value.

In the following section a brief description of the most common alternative reducing agents that are commercially available or still under development will be given.

4.1. Active (Nut) Coke

BF requires special coke size, as well as relatively low reactive coke, to maintain the furnace permeability in the lower part of the shaft [32]. In addition, the size distribution should be narrow to maintain a stable operation and low coke rate [33]. The required size is in the range of 40 to 60 mm which can be achieved by screening the produced coke, the screening results in generation of under-sieve coke, which is known as nut coke. Due to difficulties and GHG emission to produce coke, there are several attempts that have been carried out to utilize this under-sieve coke or nut coke in the BF which, of course, will affect the furnace permeability and operation smoothness, as well as productivity.

4.2. In-Plant Fines

One more promising reducing agent is carbon rich iron- and steel-making residues. Large quantities of residues are annually generated during iron and steel production, a significant amount having potential of being valuable resources of carbon and iron [34,35].

Typical carbon content for the BF dust and sludge from a production site in Sweden is ~43% and ~33%, respectively [36,37]. When operating the BF on iron ore pellets, all the dry dust may be recycled through injection in the tuyeres and by cold-bonded agglomeration [38]. However, problems arise when attempting to recycle both the dust and sludge from the gas cleaning system back to the BF. The main issue is the accumulation of zinc in the furnace which may lead to high zinc loads which, in turn, disturb the smooth running of the process [20]. An additional problem is the cost related to drying of the sludge prior to recycling.

Upgrading of BF sludge (lowering its zinc content) using a hydrocyclone has been demonstrated in previous studies [39,40,41]. Another way to reduce the zinc content of the BF sludge is by leaching. This has been realized in different leaching reagents such as sulfuric acid [37], hydrochloric acid [42], and carboxylic acids [36]. On the other hand, effective utilization of carbon rich integrated steel-making residues based on pyrometallurgical treatments has been also investigated [43,44].

4.3. Bio-Based Carbon-Bearing Materials

Biomass originating from forest residues, food wastes, etc. is today, to a large extent, used or intended for use in a number of different applications. Biomass (charcoal) was used to be the main carbon-bearing material in iron-making process until the 1880s. Later, and in order to protect the forest trees and plants against massive exploitation, it was illegalized to use such in industrial applications as a source of energy in many parts of the world. Nowadays, this type of renewable and neutral carbon has attracted more public and policy attention due its capability of mitigating fossil CO2 emission.

The use of charcoal as a reductant in smaller BFs is widely practiced in, e.g., Brazil [45]. Utilization of biomass in metallurgical processes has been studied by many researchers. They have revealed their high reactivity and high combustion degree [46,47]. However, pretreatment of biomass (carbonization) to selectively remove oxygen and improve its grindability, combustibility, and reactivity is required. A completely carbonized and devolatilized charcoal is, today, in most countries, expensive to be competitive with fossil carbon sources. A partly devolatilized or torrefied biomass is, however, a carbon source that might be competitive in the future. The carbonized biomass char is known for its high reactivity due to its highly porous structure, high specific surface area, and the non-crystalline nature. It has been reported that reactivity of biomass is couple of dozen times higher than coke which makes it promising reducing agent for even low-grade iron ores with high efficiency [48].

Biomass can be utilized in the iron-making industry through one or more of following processes:

- Biomass can be mixed with coking coal blend prior to coking in the coke oven [46].

- It can partially substitute coke by top charging of lump charcoal or through biomass containing iron composite agglomerates. A more promising route to introduce biomass in BF could be the replacement of coal injected through the tuyeres [16,49,50,51].

- It can also partially replace coke breeze as source of energy in the sintering process [52].

- Synthesis and injection of reducing gas through controlled biomass gasification [18,53]

4.4. Waste Plastic Materials

The demand for plastics has grown significantly over the past decades, and will continue. Significant amount of these plastics are today landfilled after the end-of-life cycle. Therefore, with an aim of zero plastic to landfill by 2020 [54], it becomes a necessity to develop new recycling technologies and further increase the chemical utilization of these materials instead of simple incineration. Its high content of carbon and hydrogen makes it a potential candidate to substitute the conventional carbonaceous materials used in most of the metallurgical industries [55]. It has been reported that waste plastics have the potential to be a cheap and readily available auxiliary source of carbon. Its high hydrogen content will directly help in reducing CO2 emission in iron and steel-making sector. However, the variation in composition of collected plastics from day to day and the probability of presence of impurity elements has limited its commercial utilization in many of BFs around the world.

There are three basic ways to use waste plastics in iron-making:

- Synthesis and injection of reducing gas through controlled gasification [18,53];

- Blending with raw materials (composite agglomerates, coal blend for coke-making and fuel for sintering) [25];

- Direct use by injection through tuyeres [56].

4.5. Carbon Composite Agglomerates

Composite pellets [57] or carbon composite agglomerates (CCA) are agglomerates of carbonaceous material and iron oxide mixture. The carbonaceous material can be coke fines, coal, charcoal, carbon rich in-plant fines, biomass, waste plastics, etc., while the iron oxide can be low-grade iron ores, iron rich in-plant fines, etc. [58].

Utilization of such will not only help in mitigating CO2 emission but also will help in coke and energy saving. The close distance between iron and carbon in such agglomerates will improve the reaction kinetics significantly. The other benefits that can be visualized upon utilization of such agglomerates are briefly mentioned here [58]:

- Improved reaction kinetics;

- Possibility of using iron and/or carbon rich in-plant fines [59];

- Lower gasification temperature due to the coupling effect between the gasification reaction and iron oxide (wustite) reduction [13,57]; and

- Less dependency on CO2 and energy intensive ore preparation processes.

Detailed literature survey on utilization of carbon composite agglomerates in different iron-making technologies using wider range of primary and secondary raw materials has been given earlier by Ahmed et al. [16].

5. Trends in the Applications of Alternative Carbon-Bearing Materials

Alternative carbon-bearing materials can be introduced to the iron-making processes through several ways. In the sintering process, biomass or waste plastics can partially substitute coke breeze. In-plant fines can be used as source of both carbon and iron. In coke-making, attempts were made to add biomass, as well as plastics to the coking coal blend. Alternative carbon-bearing materials can either be charged to the BF from the top along with burden materials in form of carbon composites or lump coal. Carbon rich in-plant fines, waste plastics and/or biomass can be injected to the BF through the tuyeres. In DR processes, alternative reducing agents can either be mixed with the iron oxide or gasified externally and the reduction is executed by the gasification gaseous product. The following sections are a summary of the recent research conducted in this regard with a focus on biomass.

5.1. Sintering

Sintering of iron ores can be defined as the transformation of iron ore fines into large, hard, and porous agglomerates. Sinter represents the main feed iron bearing material for the majority of modern BFs all over the world due the many advantages sinter possesses over the lump iron ore like efficient utilization of fine iron ore, dryness, less dust generation, and controlled composition [60,61].

The main fuel used in sintering process is the undersize coke or coke breeze which is generated during coke screening. Sintering contributes to the total iron and steel industry CO2 emission by approximately 10% [52]. The CO2 in this case is a result of combustion of coke breeze and the calcination of limestone for example. Therefore, it becomes a necessity to partially or completely replace the coke breeze by renewable and neutral carbon. The move from coke breeze to biomass will affect the process in several ways.

Using higher reactive carbon-bearing materials compared to coke results in decreasing the maximum temperature and shorten the time of holding at high temperature [50,62]. Utilization of biomaterials has been reported to produce a sinter with lower bulk density compared to sinter made with coke which is attributed to the narrower combustion and sintering zones due to the increased flame front speed [63]. Attempts of utilization of biomass with different levels of carbonization (starting from raw to highly carbonized biomass) in sintering process instead of coke breeze have been recently conducted. It has been found that the partial replacement of coke breeze by charcoal leads to improved off-gas quality with a decrease in SOx and NOx emissions [64,65]. A decrease in the net fossil CO2 emission by 5–15% in such a case is expected [66].

However, the moisture content of the raw biomass and the high affinity of charcoal to absorb moisture negatively affect the granulation process of sinter feed [66]. Mousa et al. [67] have studied the effect of substitution of coke breeze with bio-char with a replacement ratio up to 100%. They have found that the bed permeability as well as the sintering speed were negatively affected at replacement rate of coke breeze with biochar higher than 25%. Moreover, the higher reactivity of such material promotes the increase in CO concentration in the off-gas and decrease the degree of post combustion. Such decrease in post combustion results in lowering the combustion zone temperature by 150 °C (from ~1390 °C in case of coke breeze to ~1240 °C in case of bio-char). Other researchers have demonstrated that up to 40% bio-char can replace coke breeze without negatively affecting the process [52]. The replacement ratio can be further increased through utilization of composites of coke and bio-char [50]. In order to maintain the sinter yield as well productivity larger particles of bio-char (1–5 mm) with high solid carbon content (fixed carbon > 90%) should be used [68].

Generally, it can be concluded that in order to maximize the substitution ratio of biomass without adversely affecting the sintering process and the sinter quality, many parameters have to be controlled. These parameters include particle size, strength, reactivity, and chemical composition. The feasible share of charcoal is found to be 25–40% and the porous structure of the sinter produced in this case led to higher reducibility of the sinter without decreasing the sinter strength down to an unaccepted level [69].

5.2. Coking Coal

As previously discussed, coke cannot be totally replaced by other means. In the meanwhile, coke is the most expensive and the most CO2 intensive material to be used in the BF. Additionally, coke quality is very essential for smooth operation and high quality product. It is obvious that mechanical strength and reactivity are the very important properties to ensure smooth operation. In modern large BFs, it is always preferred to have high mechanical strength and low reactivity coke [19].

Alternative carbon-bearing materials, for example biomass, exhibit different properties compared to coal. Thus, adding biomass to coal blend affects the following properties which are essential for producing coke with good metallurgical properties:

- Fluidity: the addition of alternative carbon-bearing bio-materials is found to invariably decrease the blend fluidity [70,71]. The main reason for the deterioration of fluidity when biomaterials, for example, are added to the coal blend is attributed to their unique physical characteristics [72].

- Reactivity (coke reactivity index, CRI) and strength (coke strength after reaction, CSR) are the most important measures that are considered for evaluating coke properties. Good quality coke is always characterized by relatively low CRI (<30) and relatively high CSR (>55) [73]. Adding charcoal to the coal blend increases the reactivity of the produced bio-coke which is attributed to the calcium and/or alkali content of the charcoal, the higher the alkali index the higher the reactivity [70]. On the other hand, the poor mechanical properties, like strength and low density, have negative impacts on the mechanical properties of the produced bio-coke [74].

In the last decade, several researchers have tried to produce coke using bio-coal. The produced bio-coke has showed higher reactivity toward CO2 and, hence, using such can minimize the total carbon consumption [18]. However, as discussed earlier, adding biomass to coal blend leave behind bio-coke with poor mechanical properties compared to conventional coke. Some studies showed that even adding 3% sawdust to the coal blend prior to coking has negatively affected the product mechanical properties [72,74] while other studies stated that up to 5% biomass can be added to the coking coal blend without significant deterioration of the produced coke properties [70,72,75].

Compacting biomass prior to coking was found to reduce the negative effect on both mechanical and chemical properties [46]. Further, the compaction of biomass at 200–350 °C was found to suppress the deterioration of CSR and opens a window to increased addition rate of biomass.

5.4. BF Iron-Making

Partial substitution of virgin fossil carbon-bearing materials in BF with secondary (by products), or renewable and neutral carbon-bearing materials is one of the promising approaches to mitigate CO2 emission. There are two ways to introduce carbon-bearing materials to the BF: top charging or injection from the bottom through tuyeres. The basis on which the charging way is decided is the chemical and physical properties of the charging materials and the operating conditions.

5.4.1. Top Charging

In this section the most common carbon-bearing materials that can be charged to the BF from the top will be discussed except carbon composite agglomerate which is given elsewhere [16].

Nut Coke

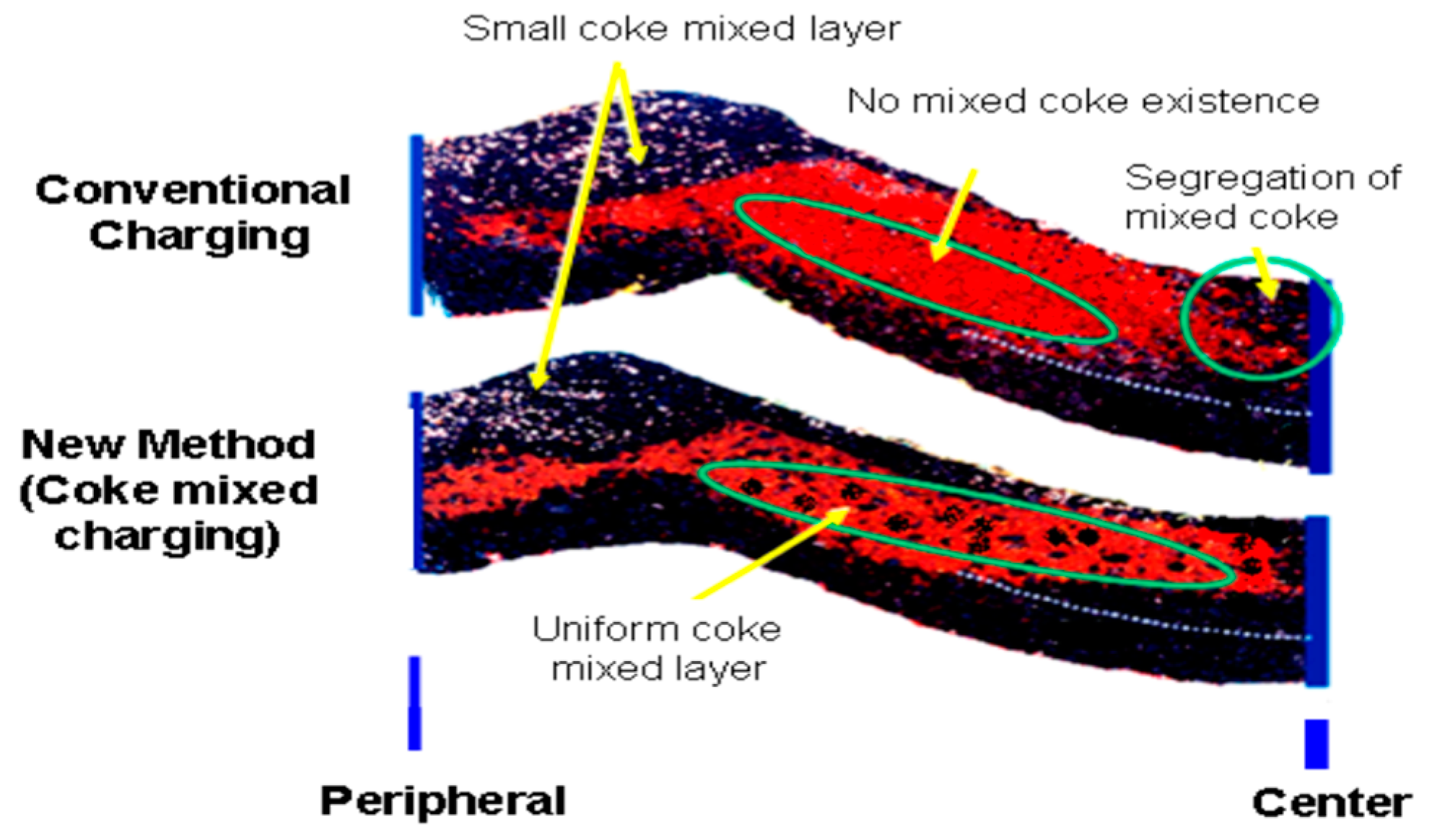

Several studies have been conducted to address the effect of charging nut coke with the burden material on the process efficiency and, hence, the productivity [8,76,77,78,79,80]. The attempts started by charging the under-sieve coke with different ratios (5–30%) within the coke layer. It resulted in reducing the productivity by 0.9–6.5%. It also led to non-uniform distribution of ascending gases [81]. Later, it has been suggested to charge the nut coke along with the burden material [82,83]. The idea was successfully tested and followed by a good improvement in the BF productivity and lowered the coke rate.

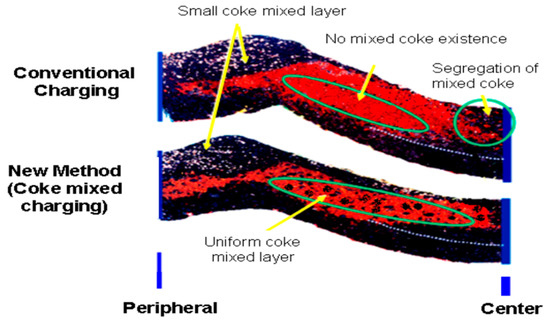

Figure 3 depicts how the size as well as its distribution affects the furnace permeability.

Figure 3.

Comparison between conventional charging method and coke mixed charging method (adopted with permission from [85]).

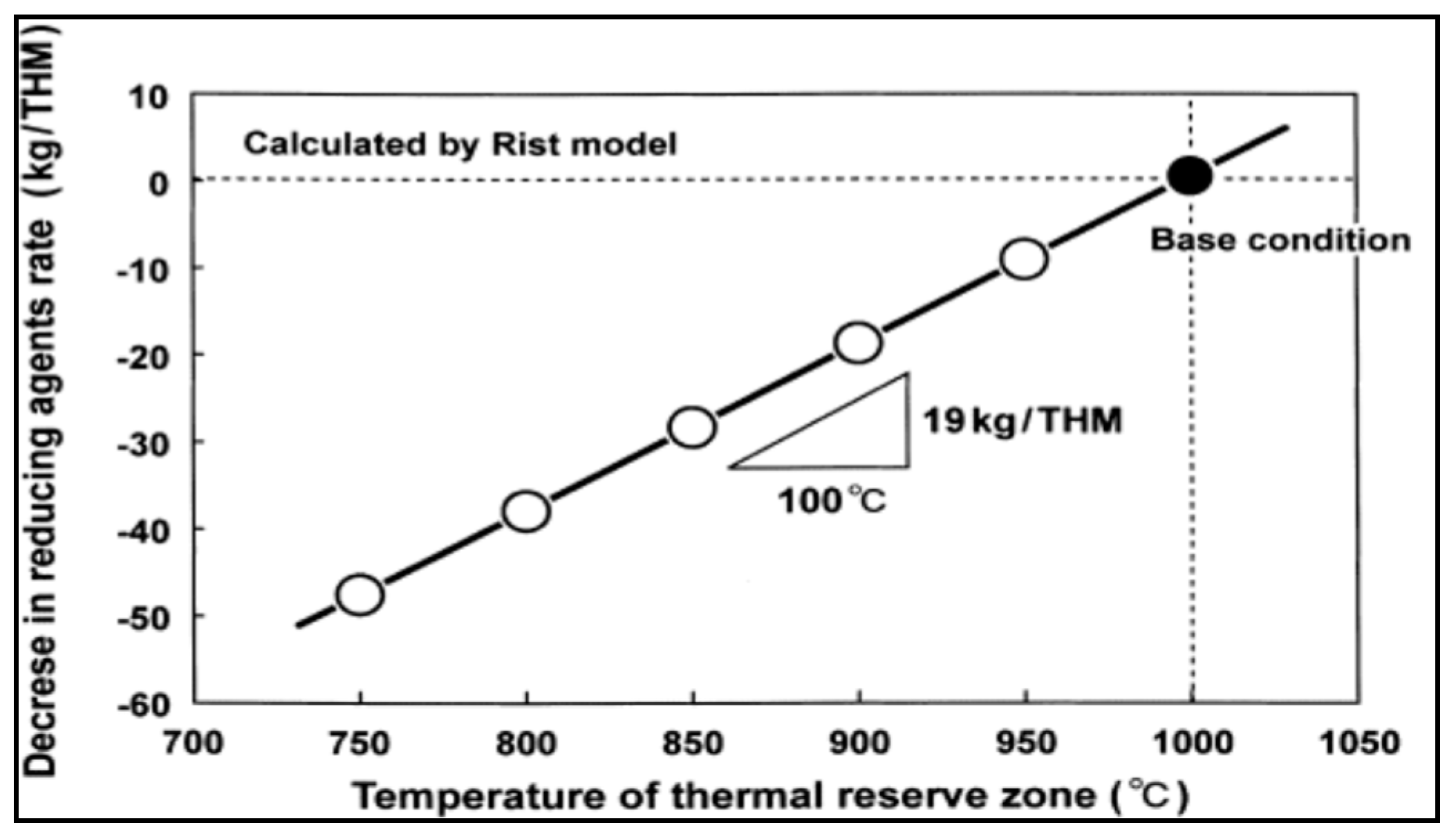

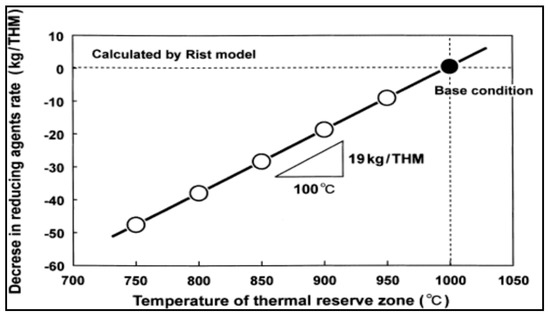

This success has inspired researchers to conduct an intensive research to study the effect of nut coke on different process parameters like permeability, reducibility, total coke consumption, etc. [8,76,77,79,80,84,85]. One of the important issues that should be taken care of is the uniform mixing of nut coke in the ore layer to maintain proper gas distribution and maintain the required permeability especially in the cohesive zone [81]. Mixing of nut coke within the ore bed was very effective in increasing the rate of carbon solution loss [13]. This further decreased the gasification reaction temperature which consequently decreased the lower limit of the thermal reserve zone (TRZ) temperature. Such a decrease in TRZ temperature shifts the process toward higher utilization of CO and, consequently, decreases the total coke consumption [13]. Figure 4 shows the relation between the thermal reserve zone temperature and coke rate consumption. Mixing nut coke in the ore layer is not only expected to improve the solution loss reaction but also expected to protect the lump coke from gasification and consequently abrasion [86].

Figure 4.

Reducing agents rate and thermal reserve zone temperature (adopted with permission from [13]).

The reactivity of small sized coke was further increased by means of surface coating with compounds that contains iron and calcium. It was found that activated nut coke shows even higher rates of gasification compared to original ones. The activation was more pronounced for coke with low CRI values and further reduced the coke rate consumption [87].

In-Plant Fines

Effective utilization of carbon rich integrated steel-making residues in iron-making have been investigated [43,44,88,89]. Producing agglomerates with a self-reducing property, which is used further to produce DRI has been proved to be an effective way to recycle the integrated steel plants generated fines. Heating such agglomerates results in high quality low zinc DRI which can be used as a replacement for the scrap in the electric arc furnace or can even be charged back to the BF to decrease the coke consumption [88,89].

Biomass

Nowadays, about 10 Mt of steel is produced using charcoal by mini-BFs with inner volume in the range of 50–350 m3 in Brazil [74]. In large modern BFs, partial replacement of top charged coke by lump charcoal (20 kg/tHM) reduces the coke consumption by approximately 30 kg/tHM without significant effect on the BF operation [18,70].

Carbon composite agglomerates (CCA) are the other option for top charging of biomass to the BF. CCA are a mixture of carbonaceous material and iron oxide in form of pellets or briquettes. Quite often these agglomerates are designed in a way to be self-reducing, C/O molar ratio is ≥1. Due to the close packing of biomass and iron oxide in the agglomerates and the unique reactivity of biomass [90], the equilibrium temperature of wustite-iron reaction shifts toward lower temperature. This shift results in higher efficiency in the BF, improved gas utilization and, consequently, reduced carbon consumption. In a study by Kasai et al. they have found that up to 19 kg/tHM can be saved if the thermal reserve zone temperature is decreased by 100 °C [13].

Plastic Materials

Top charging of plastic materials is practically impossible unless it is in form of CCA due to its chemical and physical properties. Therefore, all studies on introducing plastic to the BF are either through carbon composite agglomerates or injection through tuyeres [16,56,91].

5.4.2. Injection

Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI)

PCI is one of essential methods to enhance the BF profitability. Due to the ease of use, oil and natural gas were popular injectants in 1960s but due to the oil crises in 1970s many companies stopped the oil injection and turned to coal injection since 1980s. Nowadays, the vast majority of BFs all over the world apply PCI due to the relatively lower cost of coal compared to other fuels beside the beneficial effect on the BF efficiency. Injection of PC into the BF provides various economic and operational benefits [92]. These benefits include: (i) lower consumption of expensive coke, (ii) replacing high rank expensive coal with low grade cheaper coals, (iii) longer life period for coke oven, (iv) higher BF productivity, (v) higher flexibility in BF operation, (vi) improving the hot metal quality, and (vii) lower CO2 emission.

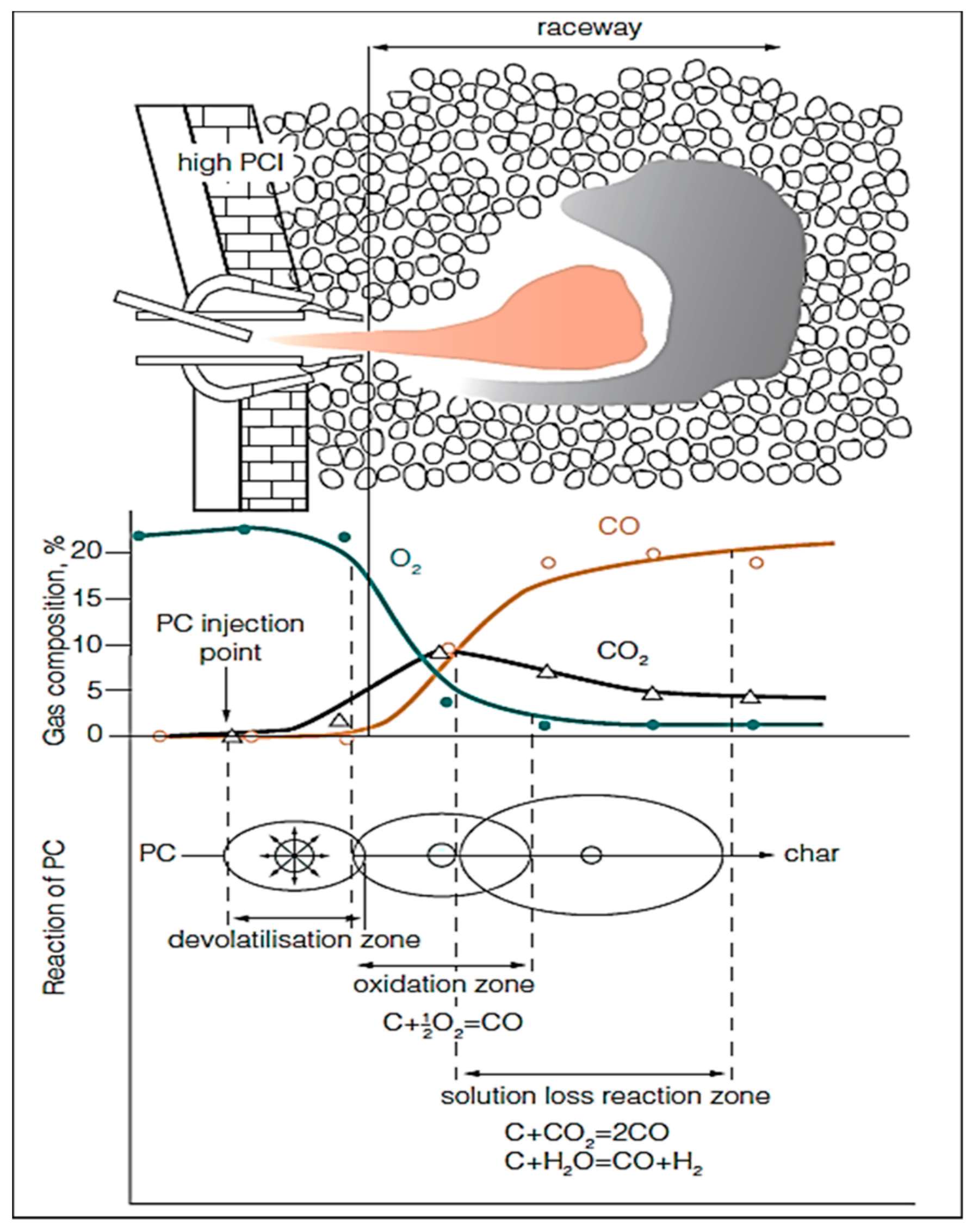

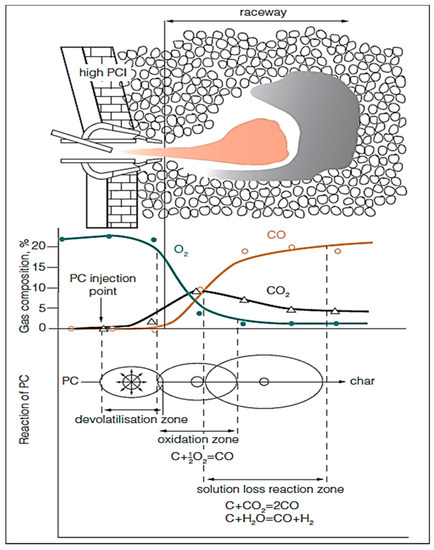

The raceway can be classified into 3 main zones: (i) PC devolatilization zone, (ii) oxidation or combustion zone, and (iii) solution loss reaction zone. The concentration of oxygen sharply decreases in the oxidation zone due to its reaction with carbon of coke and coal to produce CO/CO2. Figure 5 shows a schematic representation of the PC injection and the subsequent reactions in the raceway.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram for PC reactions in raceway (adopted with permission from [95]).

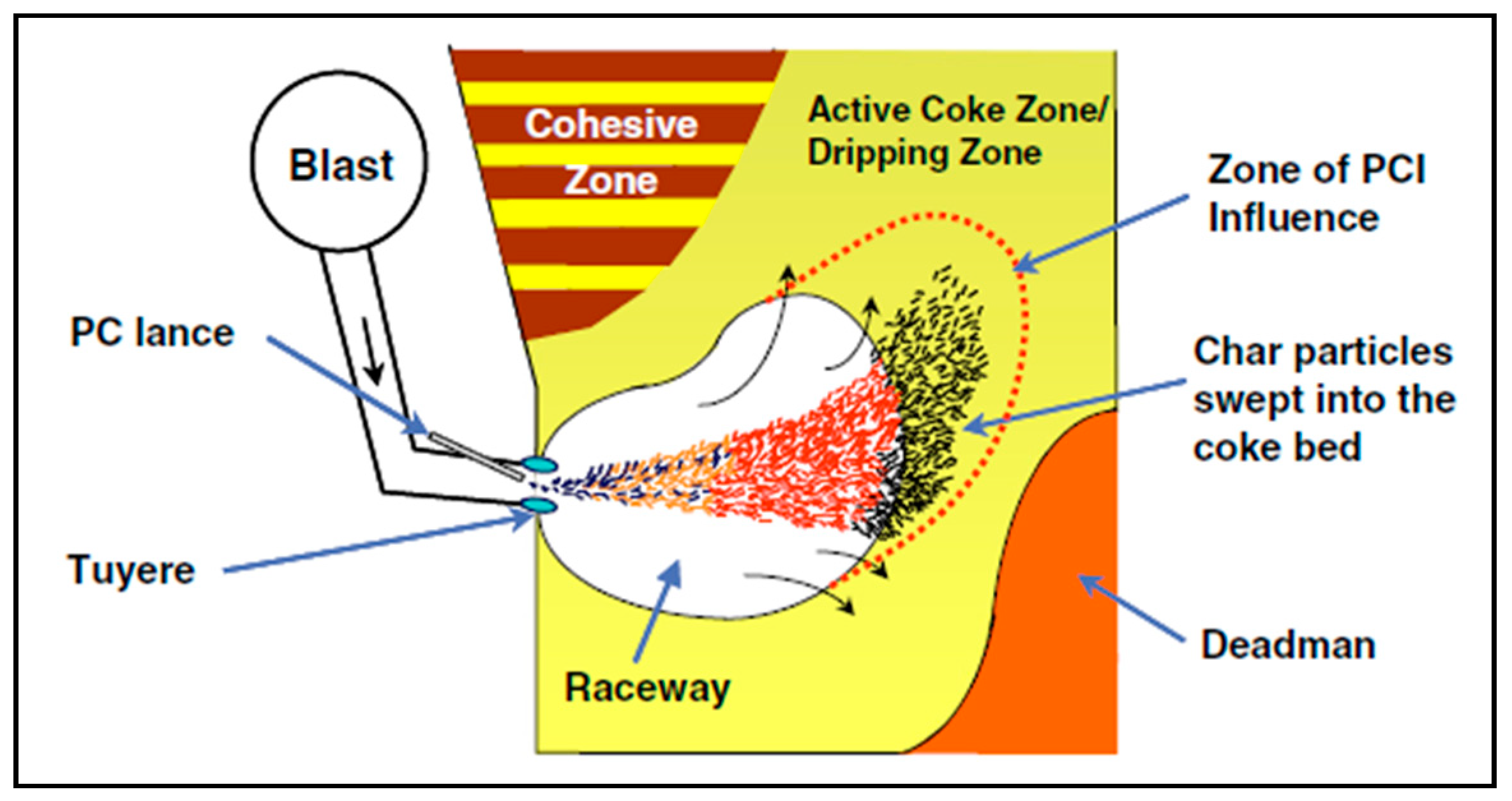

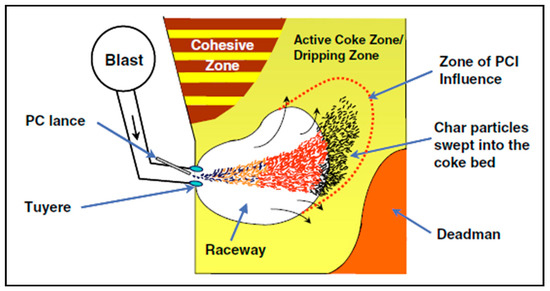

For an optimal BF operation using PCI, it is crucial to assure that the whole amount of the injected coal is gasified as fast as possible [93]. The transit time of the injected coal particles in the raceway could reach 20–30 ms. Within such limited time, the PC particles will not be completely combusted and a considerable amount of char will escape from the raceway region to reach the active coke zone as can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic of the lower zone of the BF (adopted with permission from [96]).

As a result of high injection rate of PC the fine char tend to block the bed voidage and, consequently, disturb the gas flow and increase the pressure drop, reduce the permeability, reduce the shaft efficiency and, consequently, the furnace productivity [94].

Injection of Oil and Natural Gas

The injection of oil and natural gas into the BF were firstly practiced before PCI but the energy crisis during 1970s resulted in more attention to PCI. However, the countries locally produce oil and natural gas, such as USA, Russia, and some other countries are still injecting these carbon-bearing materials into the BF to reduce the coke consumption. It has been reported that 1.0 t of oil or natural gas replaces 1.2 t of coke. The average consumption of natural gas is 70–100 m3/tHM (~50–70 kg/tHM) but often exceeds to 150–170 m3/tHM (~105–120 kg/tHM) [97,98].

In-Plant Gases

Utilization of integrated steel plant top-gases becomes necessary to achieve profitability to steel mill operation from both economic and environmental aspects. The most common gases that are daily produced in steel works and have further energy potential to be extracted are BF top gas (BFG), coke oven gas (COG), and basic oxygen furnace gas (BOFG) [97]. The heat value of the COG is greatest among other generated gases with an average value of 17 MJ/Nm3 (STP) compared to that of either BOFG which has a heating value as low as ~8.8 MJ/Nm3 or BFG which has even much lower heating value (3.0–3.7 MJ/Nm3) [99]. The specific amount of generated coke oven gas is in the range of 410–560 Nm3/t of coke while the amount of BOFG is in the range of 50–100 Nm3/t of steel in most cases. More than 650 million tonnes of coking coal are used to produce 500 million tonnes of coke annually [100]. The coke-making process is therefore accompanied by more than 310 billion Nm3 of COG [101]. Currently, coke oven gas is used after cleaning in heating stoves (BF), heating furnace (rolling mills), ignition furnaces (sintering plant), and power generation (power plant) [99].

Waste Plastics Injection

As the plastics contain mainly hydrogen and carbon it can provide additional benefits similar to oil and natural gas injection into the BF. Injection of “pure” waste plastic has been practiced at several BFs in Germany, Japan, and Austria with an injection rate up to 60–80kg/tHM [102,103,104,105]. Since the collected waste plastics are heterogeneous mixture from different types, it is recommended to conduct heat treatment at 200 °C before its injection into the BF. The pre-treatment will generate a homogenous pulverized waste plastic mixture [102]. Moreover, the pre-treatment of waste plastics will perform de-chlorination for the plastics containing chlorine, such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and, hence, avoid the corrosive effect on the BF tuyeres and the refractory materials in the hearth lining.

Due to the substantial difference in combustion and gasification characteristics between plastic and coal particles, special precautions have to be taken to insure smooth operation and maintained productivity. Studies have shown that plastic particles have the capability to gasify completely in the raceway, which is known to improve the process efficiency and sustain the gas permeability along the BF cohesive zone. The reaction kinetics of waste plastic materials under the raceway, bird’s nest and shaft conditions was studied by Babich et al. [56]. They found that physical properties of plastic including grain size, shape, and porosity have strong effects on their reaction kinetics. The unburnt char in the raceway can be successfully consumed under the conditions of bird’s nest and shaft. The theoretical limit of waste plastics injection is estimated to be 70 kg/tHM while the higher injection rate will result in problems similar to that obtained with the relatively high PCI. Every tonne of plastics used in the BF can replace 750 kg of coke. Injection of waste plastics (polyethylene, polypropylene, etc.) into the BF can reduce the CO2 emission by 30% due to the higher H2 content compared to coke [29]. However, due to restrictions mentioned above, the net influence of waste plastics can be small. Waste plastic collection and pre-treatment still represent the main challenge for its industrial implementation. An efficient and effective routine has to be developed to attain sustainable and reliable supply of waste plastics.

In-Plant Fines

BF is the production unit responsible for generating residues rich in carbon. There are two such residues: namely, the BF dust and the BF sludge. The injection of BF dust into the BF through tuyeres was actively studied in the 1980s in order to efficiently use the waste materials and increase the productivity. Further, the injection of BF flue dust and its influence on the coke consumption and hot metal quality has been tested in LKAB experimental BF (EBF) and it has been applied in a full scale BF [106,107]. It was found that the injection of BF flue dust improves the coal combustion efficiency and the slag formation in the raceway. Injection of such can be a promising solution to increase the amount of materials recycled in an operation where sintering facility does not exist.

The tuyeres injection of in-plant fines (BF dust) could achieve various advantages to the iron-making BF represented in lower top-charging of pellets and sinter, more flexibility in controlling the raceway flame temperature and hot metal quality. On the other hand, the injection rate of in-plant fines has to be adjusted with the injection rate of PC and the condition of hot blast. The calculation based on the raceway heat balance indicated that 184–100 kg/tHM of in-plant fines can be co-injected with 100–200 kg/tHM of PC, respectively [106].

Biomass Injection

The top charging of biomass into the large BF is still suffering from some problems, which are related to the low mechanical strength and the high volatile content compared to coke. In order to overcome these problems, the tuyeres injection provides a possibility for biomass utilization in modern BFs. Mechanical strength is not a prerequisite in this case. What actually important is the devolatilization, gasification and combustion characteristics as they affect (along with the heating value) the raceway adiabatic flame temperature (RAFT). Injection trials using specially-designed injection rig have demonstrated that biomass possess higher reactivity and higher combustion degree compared to pulverized coal [46,47].

The replacement rate of coal by biomass materials like charcoal, torrefied (pretreated at relatively low temperature 200–250 under inert atmosphere for short time 5–15 min) and raw biomass was theoretically investigated by means of static heat and mass balance model. A total of 155 kg/tHM of pulverized coal could be replaced by 166.7 kg/tHM charcoal. In the case of torrefied and raw wood pellets, the replacement ratio decreases significantly. The former can replace 22.8% while the later can replace only 20% of the injected pulverized coal. Further increase in the injection rate of bio-based materials requires further oxygen enrichment and it might lead to decreased RAFT temperature and increased the top gas temperature [108,109].

Theoretically, all injected coal can be replaced by charcoal (200–220 kg/tHM), which corresponds to a reduction in net CO2 emission up to ~40% [51]). Moreover, a highly efficient process is expected due to lower slag volume and low sulfur content and consequently increased production rate [110]. However, the undesired physico-chemical properties of biomass still represent the major obstacle for commercial implementation of biomass injection. These obstacles include the high moisture content, low density, and different grindability characteristics compared to coal and the low heating value [90].

6. Conclusions

Although steel is an essential product for everyday use in our life and one of the main drivers for the global growth and development, its production is considered as one of the most intensive CO2 emission sources with a share of ~7% of the global CO2 emission. Approximately 1.8 t of CO2 are emitted per every produced tonne of finished steel product. The mean reason for this is that iron and steel production is mainly dependent on fossil coking coal. Recently, the reduction of CO2 emission has put on top priorities of iron and steel producers due to the commitment of governments according to Kyoto protocol.

In the present review, the partial substitution of virgin fossil carbon namely, coal and coke, in iron-making processes with either secondary or renewable carbon-bearing materials has been discussed. It has been revealed that such substitution represents one of vital options to reduce the dependency on virgin fossil carbon and, consequently, reduce the CO2 emission.

Attempts to decrease the dependency on metallurgical coke and consequently reduce the CO2 emission have been primarily using the following approaches:

- Efficient utilization of active under size coke and in-plant gases and fines instead of the virgin metallurgical coke results in lowering the overall energy and carbon consumption and consequently decreases the CO2 emission.

- Replacing the coke with renewable, neutral and H2 rich carbon-bearing materials will directly reduce the CO2 emission due to the increased share of H2 as a reducing agent. These materials can be introduced to the iron-making processes via several means:

- (a)

- Partial replacement of coke breeze in the sintering process;

- (b)

- Blending with coking coal prior to the coke-making process;

- (c)

- Partial replacement of top charged coke by lump charcoal; and

- (d)

- Replacement of injectant pulverized coal with waste plastics, charcoal, or torrefied biomass.

- Producing agglomerates from secondary resources and/or alternative carbonaceous materials provides an opportunity to utilize wide range of materials, including mechanically unsuitable materials for direct use.

- Utilization of highly reactive carbon and/or carbon composite agglomerates will shift the iron oxide reduction process toward lower carbon consumption.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The work was carried out within CAMM—Centre of Advanced Mining and Metallurgy at Luleå University of Technology, Sweden.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- World Steel Association. Steel’s Contribution to a Low Carbon Future: Worldsteel Position Paper; World Steel Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Gambhir, A.; Florin, N.; Fennell, P. Reducing CO2 Emissions from Heavy Industry: A Review of Technologies and Considerations for Policy Makers; Briefing paper No7; Imperial College: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Coal & Steel Statistics 2014. Available online: https://www.worldcoal.org/sites/default/files/resources_files/coal_steel_facts_2014%2812_09_2014%29.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2018).

- Pardo, N.; Moya, J.A. Prospective scenarios on energy efficiency and CO2 emissions in the European Iron & Steel industry. Energy 2013, 54, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Protocol, K. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; Kyoto Protocol; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 19. [Google Scholar]

- Babich, A.; Senk, D. Coal Use in Iron and Steel Metallurgy. In The Coal Handbook: Towards Cleaner Production; Osborne, D., Ed.; Coal Utilisation; Elsevier: York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Schmöle, P.; Lüngen, H. In Hot metal production in the blast furnace gas from an ecological point of view. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Meeting on Ironmaking and 1st International Symposium on Iron Ore, Vitoria, Brazil, 12–15 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Babich, A.; Senk, D.; Yaroshevskiy, S.; Chlaponin, N.S.; Kochura, V.; Kuzin, A.; Бабич, А.; Кoчура, В.; Ярoшевский, С.; Кузин, А. In Effect of nut coke on blast furnace shaft permeability. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Process Development in Iron and Steelmaking (SCANMET III), Lulea, Sweden, 8–11 June 2008; Volume 2, pp. 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, S.; Higuchi, K.; Kunitomo, K.; Naito, M. Reaction behavior of Formed Iron Coke and Its Effect on Decreasing Thermal Reserve Zone Temperature in Blast Furnace. ISIJ Int. 2010, 50, 1388–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, S.; Ayukawa, H.; Kitaguchi, H.; Tahara, T.; Matsuzaki, S.; Naito, M.; Koizumi, S.; Ogata, Y.; Nakayama, T.; Abe, T. Improvement in Blast Furnace Reaction Efficiency through the Use of Highly Reactive Calcium Rich Coke. ISIJ Int. 2005, 45, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, S.; Kitaguchi, H.; Yamaguchi, K.; Naito, M. The characteristics of catalyst-coated highly reactive coke. ISIJ Int. 2007, 47, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, S.; Terashima, H.; Sato, E.; Naito, M. Some fundamental aspects of highly reactive iron coke production. Tetsu-to-Hagane (J. Iron Steel Inst. Jpn.) 2006, 92, 849–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, A.; Matsui, Y. Lowering of thermal reserve zone temperature in blast furnace by adjoining carbonaceous material and iron ore. ISIJ Int. 2004, 44, 2073–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasai, A.; Toyota, H.; Nozawa, K.; Kitayama, S. Reduction of reducing agent rate in blast furnace operation by carbon composite iron ore hot briquette. ISIJ Int. 2011, 51, 1333–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, S.; Yanagiya, K.; Watanabe, K.; Murakami, T.; Inoue, R.; Ariyama, T. Reaction model and reduction behavior of carbon iron ore composite in blast furnace. ISIJ Int. 2009, 49, 827–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Viswanathan, N.; Bjorkman, B. Composite Pellets—A Potential Raw Material for Iron-Making. Steel Res. Int. 2014, 85, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, M.; Okamoto, A.; Yamaguchi, K.; Yamaguchi, T.; Inoue, Y. Improvement of Blast Furnace Reaction Efficiency by Temperature Control of Thermal Reserve Zone; Nippon Steel: Tokyo, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hanrot, F.; Sert, D.; Delinchant, J.; Pietruck, R.; Bürgler, T.; Babich, A.; Fernández López, M.; Álvarez García, R.; Díez Díaz-Estébanez, M. CO2 mitigation for steelmaking using charcoal and plastics wastes as reducing agents and secondary raw materials. In Proceedings of the 1st Spanish National Conference on Advances in Materials Recycling and Eco-Energy, Madrid, Spain, 12–13 November 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Seetharaman, S. Industrial processes. In Treatise on Process Metallurgy; Elsevier: York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Biswas, A.K. Principles of Blast Furnace Ironmaking: Theory and Practice; Cootha: Brisbane, Australia, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Geerdes, M.; Chaigneau, R.; Kurunov, I. Modern Blast Furnace Ironmaking: An Introduction (2015); Ios Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Peacey, J.G.; Davenport, W.G. The Iron Blast Furnace: Theory and Practice; International Series on Materials Science and Technology; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1979; Volume 31, p. 251. [Google Scholar]

- World Steel Association. The World Steel Association Energy Fact Sheet 2008. Available online: https://www.worldsteel.org/?action=programs&id=68&about=1 (accessed on 23 March 2017).

- World Steel in Figures 2015. Available online: https://www.worldsteel.org (accessed on 23 March 2017).

- Nomura, S. Recent developments in cokemaking technologies in Japan. Fuel Process. Technol. 2017, 159, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luengen, H.B.; Peters, M.; Schmoele, P. Ironmaking in Western Europe. Iron Steel Technol. 2012, 9, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, A.M. Use of PCI in Blast Furnaces; IEA Clean Coal Centre: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sahajwalla, V.; Gupta, S. TRP0033-PCI Coal Combustion Behavior and Residual Coal Char Carryover in the Blast Furnace of 3 American Steel Companies during Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI) at High Rates; School of Materials Science and Engineering, University of New South Wales: Sydney, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, A.M. Injection of Coal and Waste Plastics in Blast Furnaces; IEA Clean Coal Centre: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chukwuleke, O.P.; Cai, J.J.; Chukwujekwu, S.; Xiao, S. Shift from Coke to Coal Using Direct Reduction Method and Challenges. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2009, 16, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangqing, Z.; Oleg, O. Energy and Exergy Analyses of Low Coke Blast Furnace Ironmaking. In Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on the Science and Technology of Ironmaking, Shanghai, China, 20–22 October 2009; pp. 603–607. [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix, P.; Dauwels, G.; Dufresne, P.; Godijn, R.; Perini, P.; Stricker, K.; Virtala, J. High blast furnaces productivity operations with low coke rates in the European Union. Revue de Métallurgie 2001, 98, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podkorytov, A.; Kuznetsov, A.; Dymchenko, E.; Padalka, V.; Yaroshevskii, S.; Kuzin, A. Theoretical and experimental foundations for preparing coke for blast-furnace smelting. Metallurgist 2009, 53, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Prakash, S.; Reddy, P.; Misra, V. An overview of utilization of slag and sludge from steel industries. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2007, 50, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trung, Z.H.; Kukurugya, F.; Takacova, Z.; Orac, D.; Laubertova, M.; Miskufova, A.; Havlik, T. Acidic leaching both of zinc and iron from basic oxygen furnace sludge. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 192, 1100–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steer, J.M.; Griffiths, A.J. Investigation of carboxylic acids and non-aqueous solvents for the selective leaching of zinc from blast furnace dust slurry. Hydrometallurgy 2013, 140, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereš, J.; Lovás, M.; Jakabský, Š.; Šepelák, V.; Hredzák, S. Characterization of blast furnace sludge and removal of zinc by microwave assisted extraction. Hydrometallurgy 2012, 129, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grip, C. Steel and sustainability: Scandinavian perspective. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2005, 32, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterworth, P.; Linsley, K.; Aumonier, J. Hydrocyclone treatment of blast furnace slurry within British Steel. Revue de Metallurgie Cahiers d’Informations Techniques 1996, 93, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijwegen, C.; Kat, W. Beneficiation of Blast Furnace Sludge. World Steel Metalwork Export Man 1984, 26, 35–39. [Google Scholar]

- Itoh, Y.; Fieser, A. Zinc Removal from Blast Furnace Dust. Iron Steel Eng. 1982, 59, 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Van Herck, P.; Vandecasteele, C.; Swennen, R.; Mortier, R. Zinc and lead removal from blast furnace sludge with a hydrometallurgical process. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2000, 34, 3802–3808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R. High temperature properties of by-product cold bonded pellets containing blast furnace flue dust. Thermochim. Acta 2005, 432, 112–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, F.; Lampinen, H.; Robinson, R. Recycling of sludge and dust to the BOF converter by cold bonded pelletizing. ISIJ Int. 2004, 44, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, S.P.; Calixto, O.K.; Vasques, F.I.; Prado, T.M.; Martins, E.M. Economical Feasibility of the Use of Biogas in Iron- and Steelmaking. In Proceedings of the Iron and Steel Technology Conference and Exposition, Cleveland, OH, USA, 4–7 May 2015; pp. 652–655. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura, T.; Ichida, M.; Nagasaka, T.; Kato, K. Carbonization behaviour of woody biomass and resulting metallurgical coke properties. ISIJ Int. 2008, 48, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janiana, M.; Eduardo, O.; Antonio, V.; Alexander, B.; Heinrich, G.; Dieter, S. Study of the Behavior of Biomass, Coal and Mixtures at Their Injection into Blast Furnace. In Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on the Science and Technology of Ironmaking, Shanghai, China, 20–22 October 2009; pp. 804–808. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, S.; Watanabe, K.; Yanagiya, K.; Inoue, R.; Ariyama, T. Improvement of Reactivity of Carbon Iron Ore Composite with Biomass Char for Blast Furnace. ISIJ Int. 2009, 49, 1505–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hata, Y.; Purwanto, H.; Hosokai, S.; Hayashi, J.; Kashiwaya, Y.; Akiyama, T. Biotar Ironmaking Using Wooden Biomass and Nanoporous Iron Ore. Energy Fuels 2009, 23, 1128–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Ji, Z.; Gan, M.; Chen, X.; Yin, L.; Jiang, T. Characteristics of prepared coke–biochar composite and its influence on reduction of NOx emission in iron ore sintering. ISIJ Int. 2015, 55, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feliciano-Bruzual, C. Charcoal injection in blast furnaces (Bio-PCI): CO2 reduction potential and economic prospects. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2014, 3, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, M.; Fan, X.; Ji, Z.; Jiang, T.; Chen, X.; Yu, Z.; Li, G.; Yin, L. Application of biomass fuel in iron ore sintering: Influencing mechanism and emission reduction. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2015, 42, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, A.; Senk, D. Recent developments in blast furnace iron-making technology. In Iron Ore: Mineralogy, Processing and Environmental Sustainability; Lu, L., Ed.; Elsevier: York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- The Statistics Portal. Available online: http://www.statista.com/statistics/282732/global-production-of-plastics-since-1950 (accessed on 23 March 2017).

- Sahajwalla, V.; Rahman, M.; Khanna, R.; Saha-Chaudhury, N.; O’Kane, P.; Skidmore, C.; Knights, D. Recycling Waste Plastics in EAF Steelmaking: Carbon/Slag Interactions of HDPE-Coke Blends. Steel Res. Int. 2009, 80, 535–543. [Google Scholar]

- Babich, A.; Senk, D.; Knepper, M.; Benkert, S. Conversion of injected waste plastics in blast furnace. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2016, 43, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.K.; Ghosh, A. Study of nonisothermal reduction of iron ore-coal/char composite pellet. MMTB 1994, 25, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Nogami, H.; Yagi, J. Numerical Analysis on Charging Carbon Composite Agglomerates into Blast Furnace. ISIJ Int. 2004, 44, 510–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, G.M.; Roy, G.G.; Roy, S.K. Reduction Kinetics of Iron Ore-Graphite Composite Pellets in a Packed-Bed Reactor under Inert and Reactive Atmospheres. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2008, 39, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, R.P.; Chattoraj, U.S.; Sil, S.K. Porosity of Sinter and its relation with the sintering indices. ISIJ Int. 2006, 46, 1728–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubu, H.; Kodama, T.; Itaya, H.; Oguchi, Y. Formation of pores in iron ore sinter. Trans. Iron Steel Inst. Jpn. 1986, 26, 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Ji, Z.; Gan, M.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Jiang, T. Influence of preformation process on combustibility of biochar and its application in iron ore sintering. ISIJ Int. 2015, 55, 2342–2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovel, R.R.; Vining, K.R.; Dell’Amico, M. The influence of fuel reactivity on iron ore sintering. ISIJ Int. 2009, 49, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L. Iron Ore: Mineralogy, Processing and Environmental Sustainability; Elsevier: York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Adam, M.; Kilburn, M.; Hapugoda, S.; Somerville, M.; Jahanshahi, S.; Mathieson, J.G. Substitution of charcoal for coke breeze in iron ore sintering. ISIJ Int. 2013, 53, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieson, J.; Norgate, T.; Jahanshahi, S.; Somerville, M.; Haque, N.; Deev, A.; Ridgeway, P.; Zulli, P. The potential for charcoal to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions from the Australian steel industry. In Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on the Science & Technology of Ironmaking—ICSTI 2012, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 14–18 October 2012; Volume 3, pp. 1602–1613. [Google Scholar]

- Mousa, E.; Babich, A.; Senk, D. Iron Ore Sintering Process with Biomass Utilization. In Proceedings of the METEC & 2nd ESTAT, Düsseldorf, Gemany, 15–19 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi, T.; Hara, M. Utilization of biomass for iron ore sintering. ISIJ Int. 2013, 53, 1599–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suopajärvi, H.; Kemppainen, A.; Haapakangas, J.; Fabritius, T. Extensive review of the opportunities to use biomass-based fuels in iron and steelmaking processes. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 148, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPhee, J.; Gransden, J.; Giroux, L.; Price, J. Possible CO2 mitigation via addition of charcoal to coking coal blends. Fuel Process. Technol. 2009, 90, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Díaz, M.; Zhao, H.; Kokonya, S.; Dufour, A.; Snape, C.E. The effect of biomass on fluidity development in coking blends using high-temperature SAOS rheometry. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiano, M.; Barriocanal, C.; Alvarez, R. Effect of the addition of waste sawdust on thermoplastic properties of a coal. Fuel 2013, 106, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, R.; Diez, M.; Barriocanal, C.; Diaz-Faes, E.; Cimadevilla, J. An approach to blast furnace coke quality prediction. Fuel 2007, 86, 2159–2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiano, M.; Díaz-Faes, E.; Barriocanal, C.; Alvarez, R. Influence of biomass on metallurgical coke quality. Fuel 2014, 116, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiano, M.; Díaz-Faes, E.; Barriocanal, C. Effect of briquette composition and size on the quality of the resulting coke. Fuel Process. Technol. 2016, 148, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, E.A.; Babich, A.; Senk, D. Effect of nut coke-sinter mixture on the blast furnace performance. ISIJ Int. 2011, 51, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, E.; Senk, D.; Babich, A.; Gudenau, H. Influence of nut coke on iron ore sinter reducibility under simulated blast furnace conditions. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2010, 37, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, E. Reduction of Iron Ore Burden Materials Mixed with Nut Coke Under Simulated Blast Furnace Conditions. Ph.D. Thesis, Shaker Verlag Gmbh, Aachen, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mousa, E.; Senk, D.; Babich, A. Reduction of Pellets-Nut Coke Mixture under Simulating Blast Furnace Conditions. Steel Res. Int. 2010, 81, 706–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babich, A.; Senk, D.; Gudenau, H.W. Effect of coke reactivity and nut coke on blast furnace operation. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2009, 36, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, L.; Mar’yasov, M.; Gorbachev, V.; Bugaev, S.; Denisov, Y.M. Blast-furnace operation with coke fines. Metallurgist 1999, 43, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loginov, V.; Solomatin, S.; Korzh, A. Experimental melts with blast furnaces charged with mixture of coke and sinter. Metallurgist 1976, 20, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loginov, V.; Berin, A.; Solomatin, S. Effect of mixing burden with coke on blast furnace fluid mechanics and operation parameters. STAL 1977, 5, 391. [Google Scholar]

- Yaroshevskii, S.; Nozdrachev, V.; Chebotarev, A.; Rudenko, V.; Feshchenko, S.; Kuznetsov, A.; Padalka, V.; Khlaponin, N.; Kuzin, A. Efficiency of using coke fractions smaller than 40 mm in a blast furnace. Metallurgist 2000, 44, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watakabe, S.; Takeda, K.; Nishimura, H.; Goto, S.; Nishimura, N.; Uchida, T.; Kiguchi, M. Development of high ratio coke mixed charging technique to the blast furnace. ISIJ Int. 2006, 46, 513–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawayama, M.; Miyagawa, K.; Nozawa, K.; Matsui, Y.; Shibata, K. Low coke rate operation of blast furnace by controlling size of coke mixed into ore layer. In Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on the Science and Technology of Ironmaking, Shanghai, China, 20–22 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ökvist, L.S.; Brandell, C.; Lundgren, M.; AB, L. Impact of Activated nut Coke on Energy Efficiency in the Blast Furnace. Available online: https://www.lkab.com/sv/SysSiteAssets/documents/kund/2014-impact-of-activated-nut-coke-on-energy-efficiency-in-the-blast-furnace.pdf (accessed on 3 April 2018).

- Ahmed, H.; Persson, A.; Sundqvist, L.; Biorkman, B. Energy Efficient Recycling of in-Plant Fines. Energy 2014, 1, 9689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.M.; Persson, A.; Okvist, L.S.; Bjorkman, B. Reduction Behaviour of Self-reducing Blends of In-plant Fines in Inert Atmosphere. ISIJ Int. 2015, 55, 2082–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueda, S.; Watanabe, K.; Yanagiya, K.; Inoue, R.; Ariyama, T. Optimization of Biomass Utilization for Reduction CO2 in Ironmaking Process. In Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on the Science and Technology of Ironmaking, Shanghai, China, 20–22 October 2009; pp. 593–599. [Google Scholar]

- Mirabile, D.; Pistelli, M.I.; Marchesini, M.; Falciani, R.; Chiappelli, L. Thermal valorisation of automobile shredder residue: Injection in blast furnace. Waste Manag. 2002, 22, 841–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, P.; Fukushima, T. Impact of PCI coal quality on blast furnace operations. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Computational Science (ICCS), Melbourne, Australia and St. Petersburg, Russia, 2–4 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schott, R. State-of-the-Art PCI technology for blast furnace ensured by continuous technological and economical improvement. Iron Steel Technol. 2013, 10, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Raask, E. Mineral Impurities in coal Combustion: Behavior, Problems, and Remedial Measures; Taylor & Francis: York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Kamijou, T.; Shimizu, M. PC Combustion in Blast Furnace. In Advanced Pulverized coal Injection Technology and Blast Furnace Operation; Pergamon: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2000; Volume 1, pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson, J.G.; Truelove, J.S.; Rogers, H. Toward an understanding of coal combustion in blast furnace tuyere injection. Fuel 2005, 84, 1229–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worrell, E. Energy Efficiency Improvement and Cost Saving Opportunities for the US Iron and Steel Industry—An ENERGY STAR (R) Guide for Energy and Plant Managers; Berkeley National Laboratory: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lingiard, O.; Burrai, O.; Partemio, C.; Giandoménico, F.; Etchevarne, P.; Gonzalez, J.M. High productivity and coke rate reduction at Siderar blast furnace# 2. In Proceedings of the 1st International Meeting on Ironmaking, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 24 September 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Diemer, P.; Knop, K.; Luengen, H.B.; Reinke, M.; Wuppermann, C. Utilization of coke oven gas for the production of DRI. Stahl Eisen 2007, 127, 19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Spirin, N.; Shvidkiy, V.; Yaroshenko, Y.; Gordon, Y. Improvement in energy efficiency of blast furnace. In Proceedings of the METEC & ESTAD, Düsseldorf, Germany, 15–19 June 2015; pp. 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, X.; Ding, W. Steam reforming of coke oven gas for hydrogen production over a NiO/MgO solid solution catalyst. Energy Fuels 2009, 24, 785–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asanuma, M.; Ariyama, T.; Sato, M.; Murai, R.; Nonaka, T.; Okochi, I.; Tsukiji, H.; Nemoto, K. Development of waste plastics injection process in blast furnace. ISIJ Int. 2000, 40, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyama, T.; Matsuura, M.; Noda, H.; Asanuma, M.; Shikada, T.; Murai, R.; Nakamura, H.; Sumigama, T. Development of shaft-type scrap melting process characterized by massive coal and plastics injection. ISIJ Int. 1997, 37, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, J.; Weiss, W. Injection of waste plastics into the blast furnace of Stahlwerke Bremen. Revue de Métallurgie 1996, 93, 1219–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchwalder, J.; Scheidig, K.; Schingnitz, M.; Schmöle, P. Results and trends on the injection of plastics and ASR into the blast furnace. ISIJ Int. 2006, 46, 1767–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ökvist, L.S. Co-Injection of Basic fluxes or BF Flue Dust with PC into a BF Charged with 100% Pellets: Effects on Slag Formation and Coal Combustion. Ph.D. Thesis, Luleå Tekniska Universitet, Luleå, Sweden, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson, B.; Ökvist, L.S. Injection of BF flue dust into the BF-a full-scale test at BF No. 3 in Luleå. In Proceedings of the Scanmet II 2nd International Conference on Process Development in Iron and Steelmaking, Luleå, Sweden, 6–9 June 2004; pp. 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Mellin, P.; Lövgren, J.; Nilsson, L.; Yang, W.; Salman, H.; Hultgren, A.; Larsson, M. Biomass as blast furnace injectant–Considering availability, pretreatment and deployment in the Swedish steel industry. Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 102, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Larsson, M.; Lövgren, J.; Nilsson, L.; Mellin, P.; Yang, W.; Salman, H.; Hultgren, A. Injection of solid biomass products into the blast furnace and its potential effects on an integrated steel plant. Energy Procedia 2014, 61, 2184–2187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suopajärvi, H.; Pongrácz, E.; Fabritius, T. The potential of using biomass-based reducing agents in the blast furnace: A review of thermochemical conversion technologies and assessments related to sustainability. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 511–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).