Abstract

This research examines a semi-analytical approach for analyzing the nonlinear vibration (NV) characteristics of oblique-stiffened multilayer functionally graded (OSMFG) cylindrical shells (CSs) under external excitation. The material’s properties are continuously graded along the thickness direction. The CSs are made up of three layers: an inner metal-rich layer, an exterior ceramic-rich layer, and a functionally graded (FG) layer in between. The stiffeners’ constitutive material is graded constantly throughout their thicknesses. von Kármán equations, the smeared stiffener technique, and the Galerkin approach are used to address the NV problem. The vibration behavior is investigated via the method of multiple scales (MMSs). The analysis considers an internal resonance of 1:1/3:1/9 as well as a superharmonic resonance of order 3/1. The impacts of various material and geometric characteristics on the NV of OSMF-CSs are thoroughly investigated.

1. Introduction

Stiffeners are extensively utilized to reinforce structural systems, especially when composed of FG materials. In addition, CSs reinforced with stiffeners and composed of FG materials have various applications in different industries. In this regard, some researchers have concentrated on the vibration responses of plates and shells [1,2,3,4]. Meanwhile, others have addressed the vibration behaviors of shells made of FG materials [5,6,7].

Recently, Foroutan and Torabi [8] described the NV behaviors of porous sandwich FG CSs with a porous two-layered FG core. Additionally, some researchers have examined the vibration behaviors of FG shells reinforced with stiffeners [9,10,11,12]. At the same time, other researchers have focused on investigating the vibration behaviors of FG CSs reinforced with stiffeners [13,14,15].

Despite the widespread use of plates and shells in many industrial applications, their resonance behavior was not addressed in the aforementioned research. However, some researchers have focused on the resonant behavior of plates and shells [16,17,18,19], while others have examined the resonant response of plates and shells composed of FG materials [20,21,22]. Additionally, some researchers have investigated the resonance behaviors of FG shells reinforced with stiffeners [23,24]. At the same time, other researchers have studied the resonance behavior of FG CSs reinforced with stiffeners [25,26]. Recently, Foroutan and Torabi [27] examined the NV behavior of multilayer FG CSs reinforced with internal FG spiral stiffeners under thermal conditions, including subharmonic resonance of order 1/2 and an internal resonance of 1:2:4.

Despite the extensive usage of oblique-stiffened FG CSs in diverse industrial applications, the internal resonance and superharmonic resonance of order 3/1 for the first three modes of oblique-stiffened FG CSs were not studied in the abovementioned works. Therefore, for the first time in the presented study, we examined the nonlinear internal resonance and superharmonic resonance of order 3/1 for the first three modes of OSMFG-CSs. It is necessary to explain that these shells are commonly employed in industries where robust structural components are crucial, such as in aerospace, marine, and automotive engineering. Additionally, the unique composition and arrangement of multilayer shells make them ideal for environments subjected to dynamic external excitation, such as vibration in aircraft engines or marine hulls exposed to variable oceanic pressures. So, the novelties of this work are as follows: (I) The resonant case considered here is a 1:1/3:1/9 internal resonance and a superharmonic resonance of order 3/1. (II) We analyze the NV of OSMFG CSs with a semi-analytical method. (III) The CSs are composed of three layers: metal, FG, and ceramic. (IV) The external oblique stiffeners are assumed to be FG. To this end, to derive the nonlinear equations of OSMFG CSs, the smeared stiffener technique, classical shell theory, and von Kármán equations are utilized. Then, Galerkin’s approach is applied to discretize the nonlinear equations. The MMSs is utilized to examine the NV of OSMFG-CSs. We find that the observed resonance interactions can give rise to complex dynamic phenomena, which are crucial for understanding the operational limits and ensuring the safety of these structures in practical scenarios. Additionally, the findings from this study demonstrate that these resonances may either amplify or mitigate the NV characteristics, thus having a direct impact on the structural integrity and performance of OSMFG cylindrical shells.

2. Theoretical Formulations

2.1. OSMFG-CSs

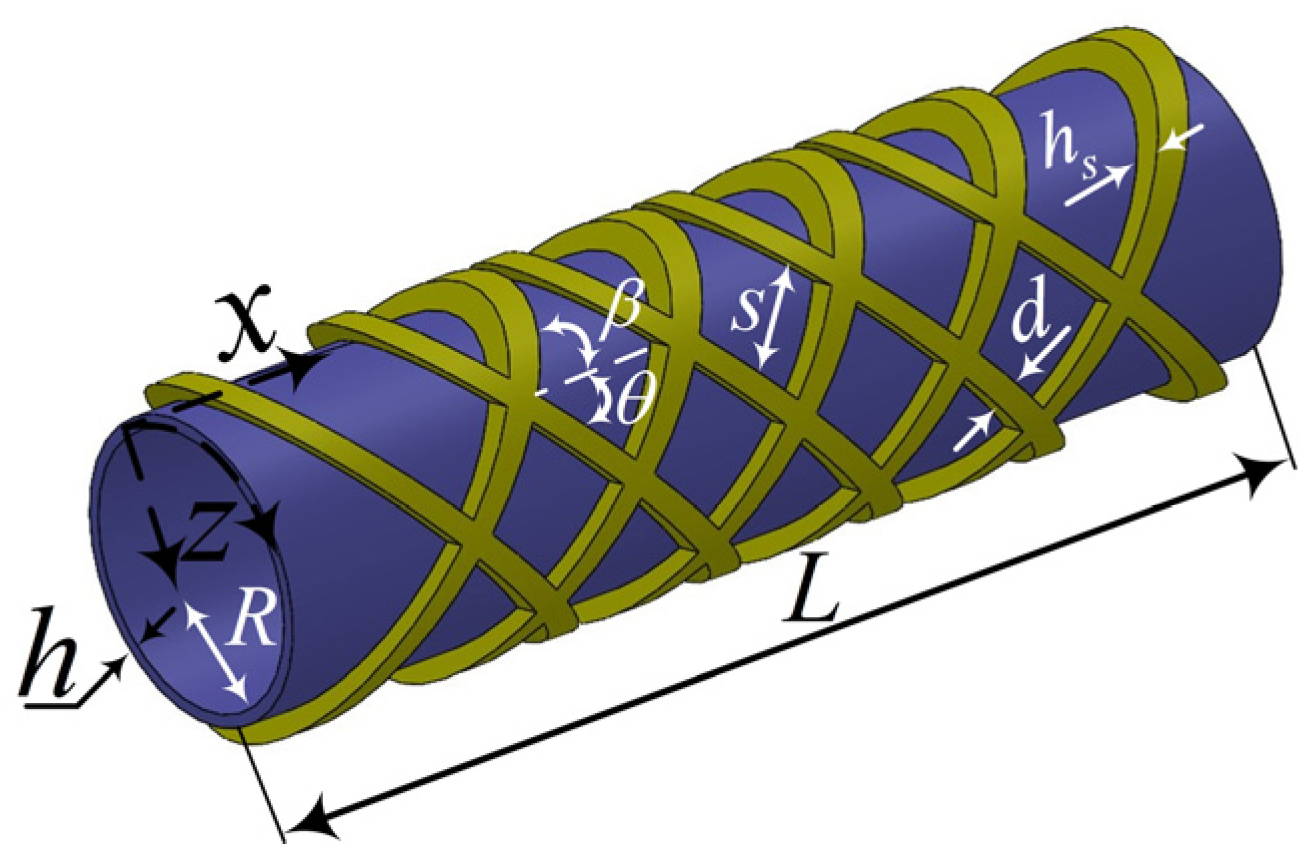

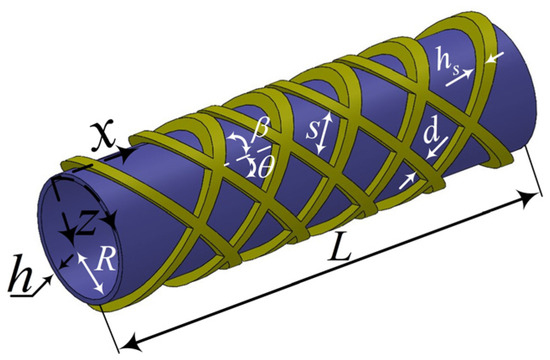

The configuration of OSMFG-CSs with length (), radius (), and thickness () is demonstrated in Figure 1. Also, as shown, the CSs are reinforced with external oblique stiffeners with thickness (), angles (), width (), and spacing ().

Figure 1.

Schematic of OSMFG-CSs.

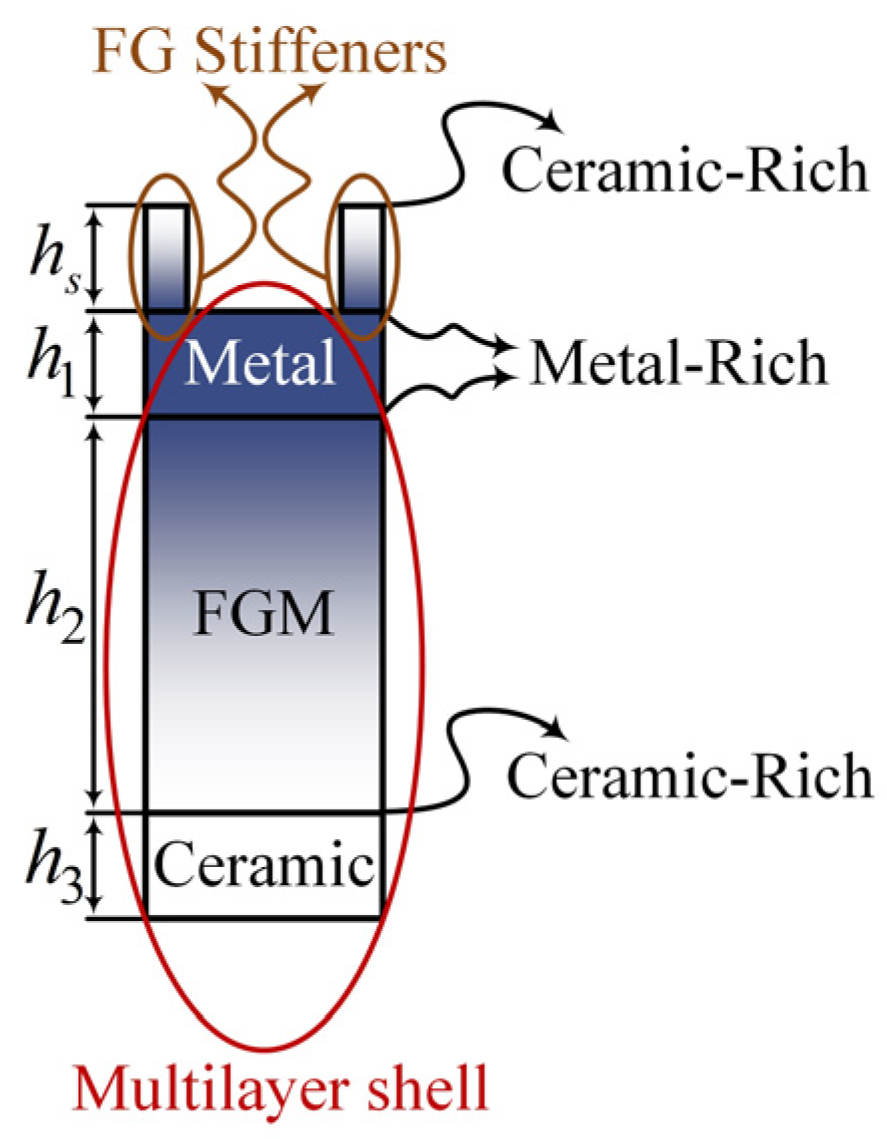

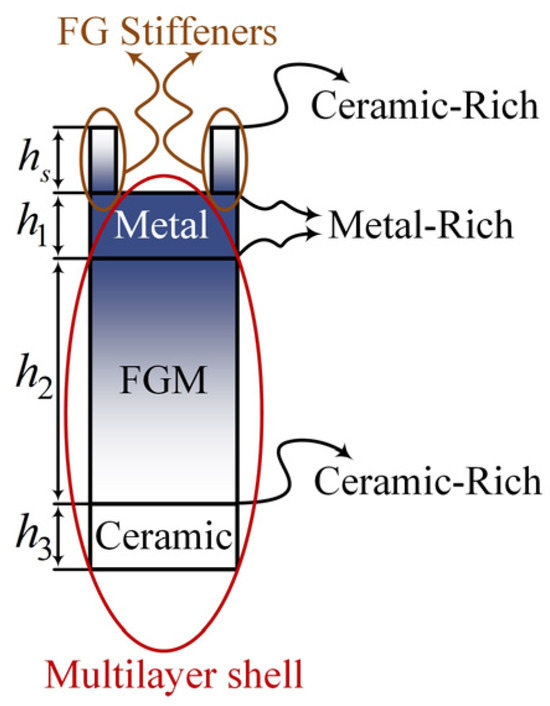

In this study, it was assumed that OSMFG-CSs have three layers, which are demonstrated in Figure 2. According to this figure, the CSs are made up of three layers: an inner metal-rich layer, an exterior ceramic-rich layer, and a functionally graded (FG) layer in between. In this regard, , respectively, indicate the thicknesses of the metal, FG, and ceramic layers.

Figure 2.

The distribution of the materials in OSMFG-CSs.

To ensure the continuity of the materials’ properties at the interface of the layers in the CSs, as well as at the metal-rich interface between the CSs and oblique stiffeners, Young’s modulus () and the mass density () were defined as follows:

- Shell

- External stiffeners

2.2. Governing Equation

The strain components across the thickness at a distance from the mid-surface of the CSs are as follows [28]:

in which, , and are respectively the displacements through the axes of , , and , respectively. Regarding Equation (3), the compatibility equation of OSMF-CSs is as below:

With regard to Hooke’s law, the relationships of the stress-strain of CSs are as below:

where is Poisson’s ratio. Additionally, the constitutive law of oblique stiffeners is

To model the stiffeners on the CSs, the smeared stiffener technique is applied. To obtain the resultant forces () and moments () of the OSMF-CSs, Equations (5) and (6) are integrated in the thickness direction, so that the resultant force and moment are obtained as follows:

- Resultant forces

- Resultant moments

The coefficients in Equations (7) and (8) are presented in Appendix A. The equilibrium equations for OSMF-CSs regarding classical shell theory are as follows [29,30,31]:

where is the damping coefficient, and mass density and excitation are as follows:

The following stress function () [32] can be defined to satisfy Equations (9) and (10):

Substituting the strain relations of Equation (7) into Equations (4) and (11) and using Equations (3) and (13), the system equations are obtained as

where are illustrated in Appendix B.

2.3. Dynamic Galerkin Approach

When we investigate the NV of OSMFG-CSs with simply supported boundary conditions, the low-frequency modes are considered to be more important than the high-frequency modes. In this context, according to the boundary conditions, the approximate solution is . So, in the present study, we concentrated on transverse nonlinear system oscillation in the first three modes (i.e., first mode: , second mode: and , and third mode: and ). Consequently, the following is the approximate solution:

where , , , , , and are, respectively, the amplitudes and shape functions of the first three modes.

Equation (16) is substituted in Equation (14) to obtain the following solution to :

The coefficients are functions of , , , , , , . They are too lengthy to be expressed explicitly here, but computer algebra makes them simple to calculate.

Substituting Equations (16) and (17) into Equation (15), and applying the Galerkin approach, the discretized equations of motion are obtained as

where the coefficients , , and are functions of , , , , , and . Similarly, they are too lengthy to be expressed explicitly here, but computer algebra makes them simple to calculate.

2.4. Investigation of Nonlinear Equations via MMSs

For solving Equations (18)–(20) via the MMSs, the following expansion is used:

where and the new time-dependent variables and are introduced as ().

As mentioned previously, only the case with a 1:1/3:1/9 internal resonance and a superharmonic resonance of order 3/1 was considered in the current study. Therefore, we have resonant relations in the following form:

Equations (14) and (15) are first substituted into Equations (18)–(20). Next, the coefficients of and (perturbation coefficients) are set to zero. The general solutions for the coefficients of (i.e., ) are then determined and subsequently substituted into the coefficients of . This process results in three equations that include secular terms (i.e., terms proportional to ), their complex conjugates, and nonsecular terms. Finally, the secular terms in the three obtained equations are set to zero, leading to the following equations in complex form:

To find the solutions to Equations (23)–(25), is assumed. In this context, denote the functions that relate to the NV’s amplitude and phase of the OSMFG-CSs. Therefore, by substituting Equation into Equations (23)–(25), the following provides the obtained equation’s imaginary and real components:

3. Numerical Outcomes

We first compared the results for certain circumstances using numerical simulations with those previously reported by other scholars. The dimensionless natural frequencies (DNFs) () in Table 1 are therefore compared to those reported by Yang et al. [33], Zhang et al. [34], and Song and Li [35]. It is clear from these comparisons that the agreement is good.

Table 1.

Comparison of DMFs of CSs ().

In this study, the NV behaviors of the OSMFG-CSs were examined. The OSMFG-CSs were considered to be made of alumina (ceramic) (, ) and aluminum (metal) (, ). Also, the geometric characteristics of the CSs and stiffeners are demonstrated in Table 2, which were applied to obtain the outcomes.

Table 2.

Geometric specifications of CSs and stiffeners.

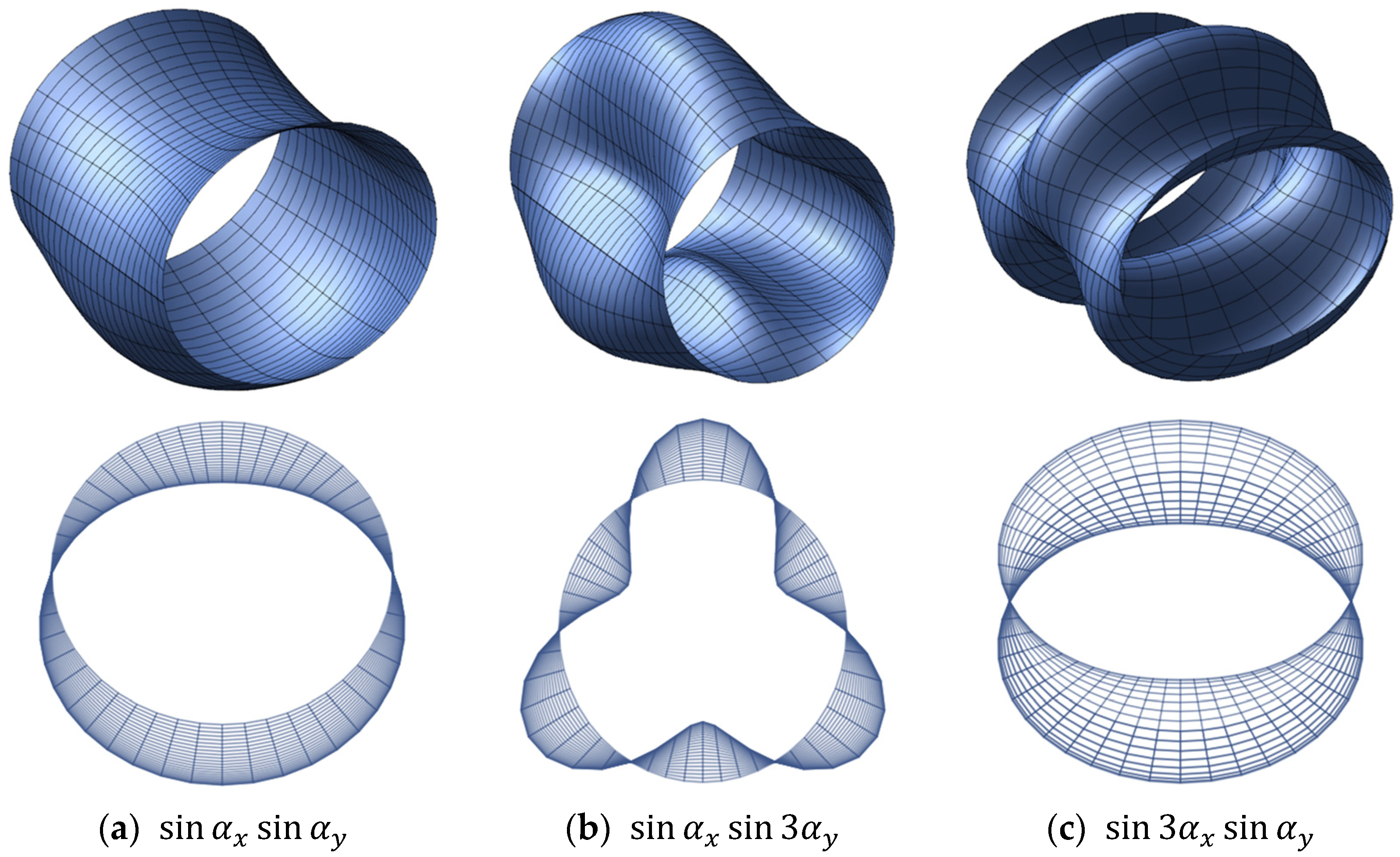

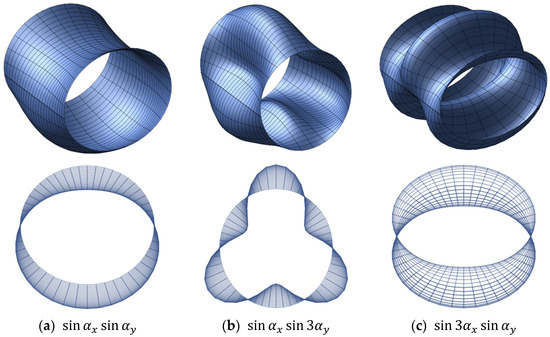

In Figure 3, the three mentioned mode’s shapes of the OSMFG-CSs, which were addressed in the current study, are illustrated in both two- and three-dimensional forms.

Figure 3.

The shapes of OSMFG-CSs in different modes.

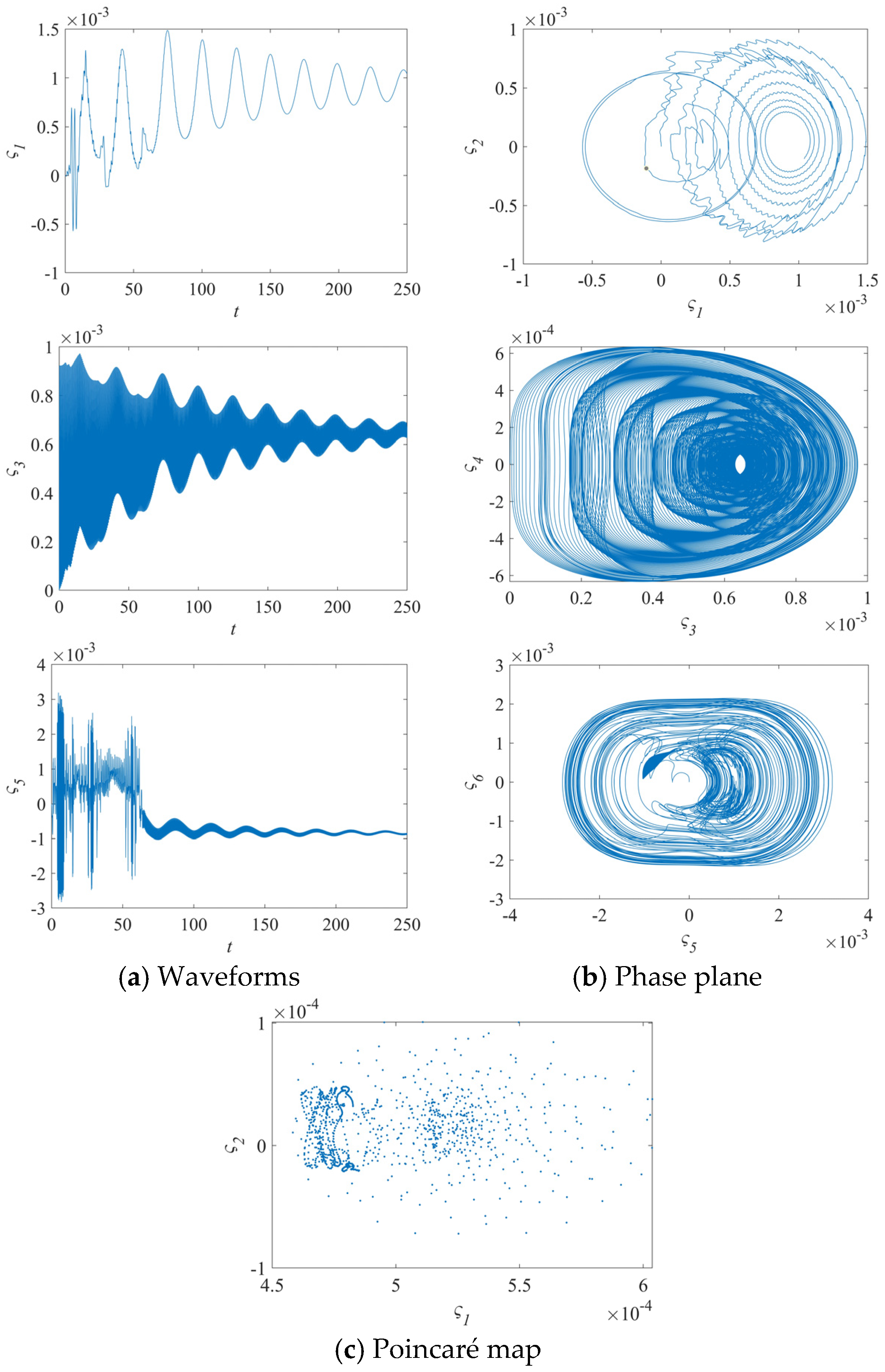

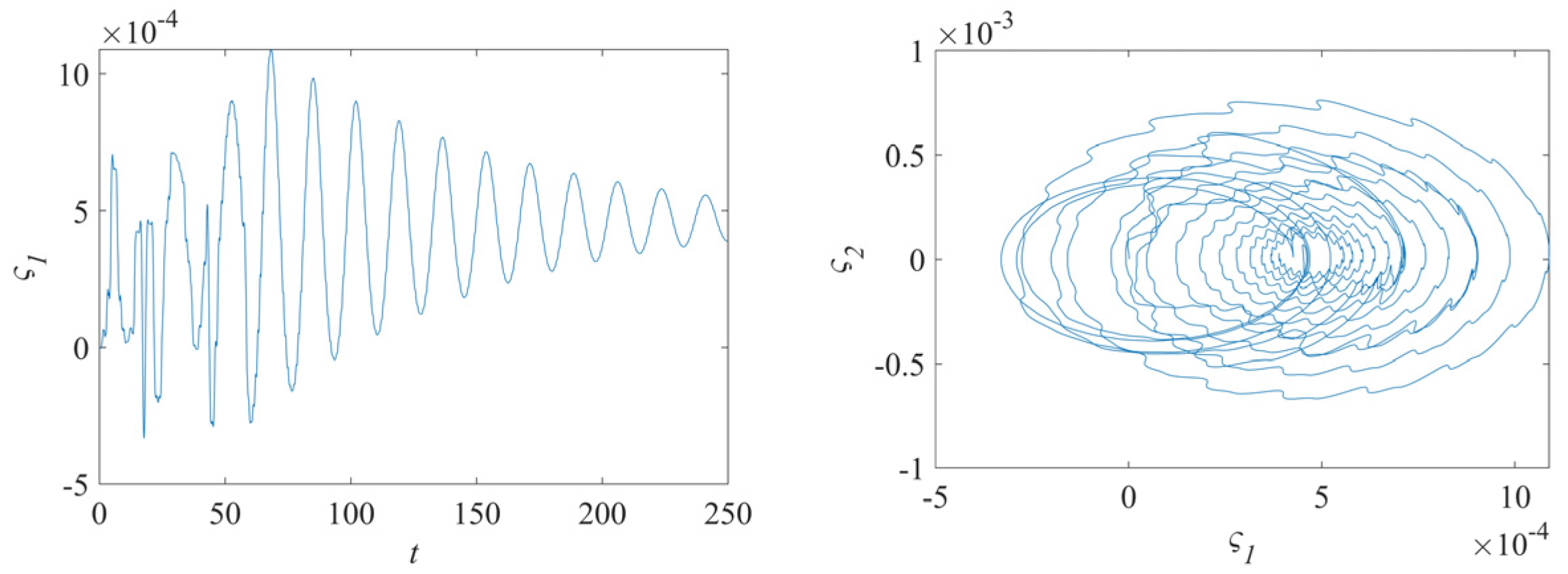

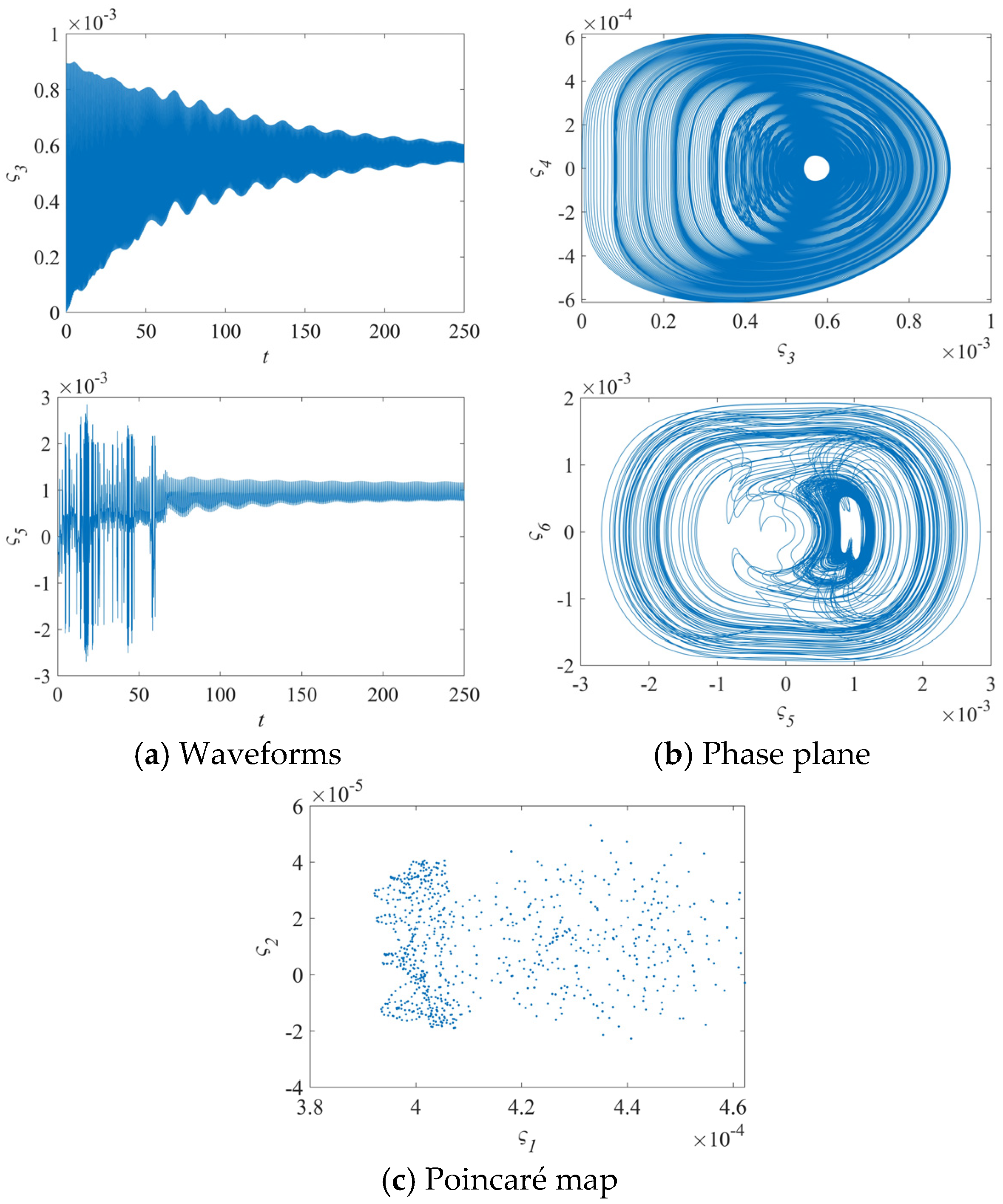

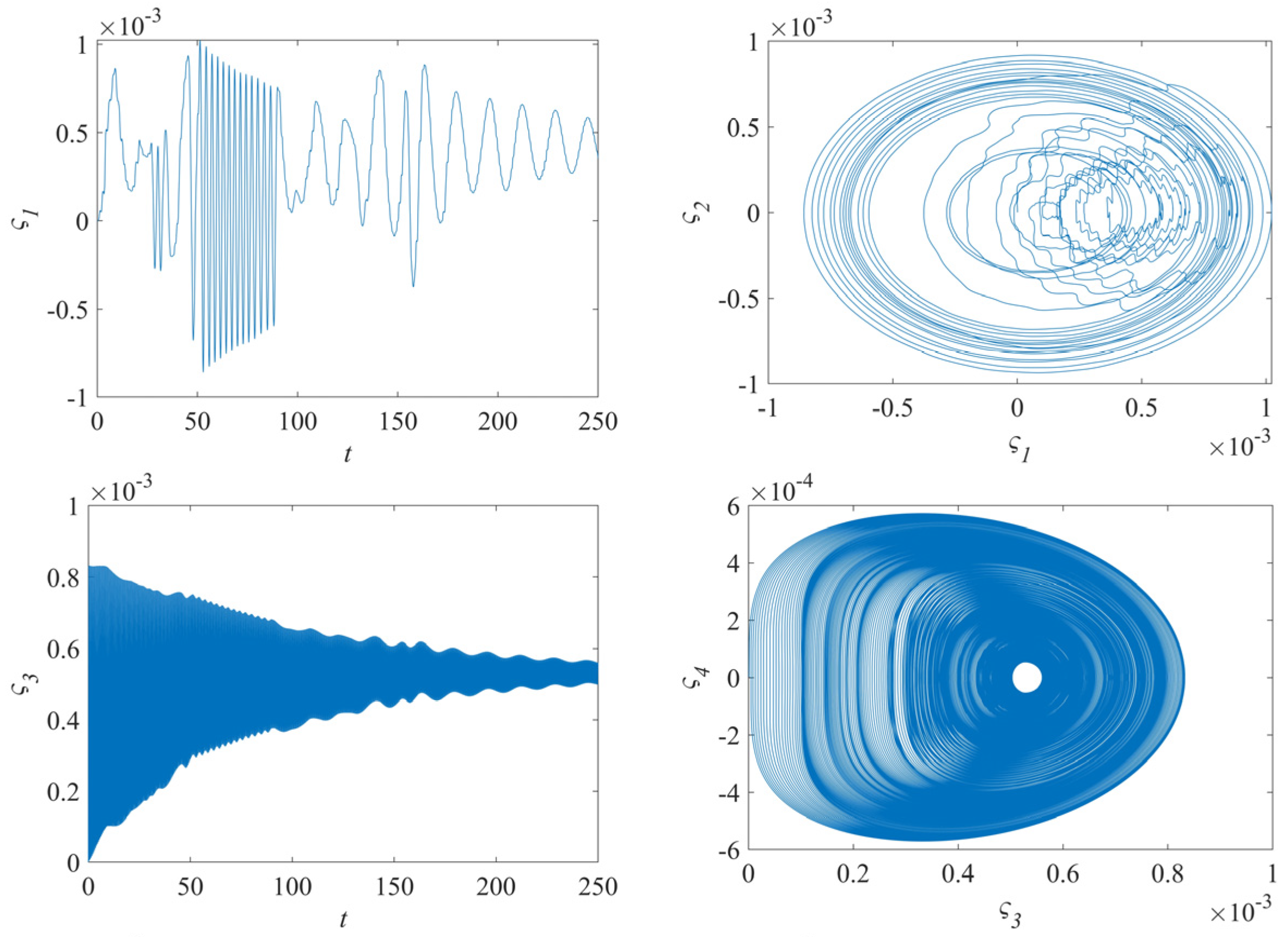

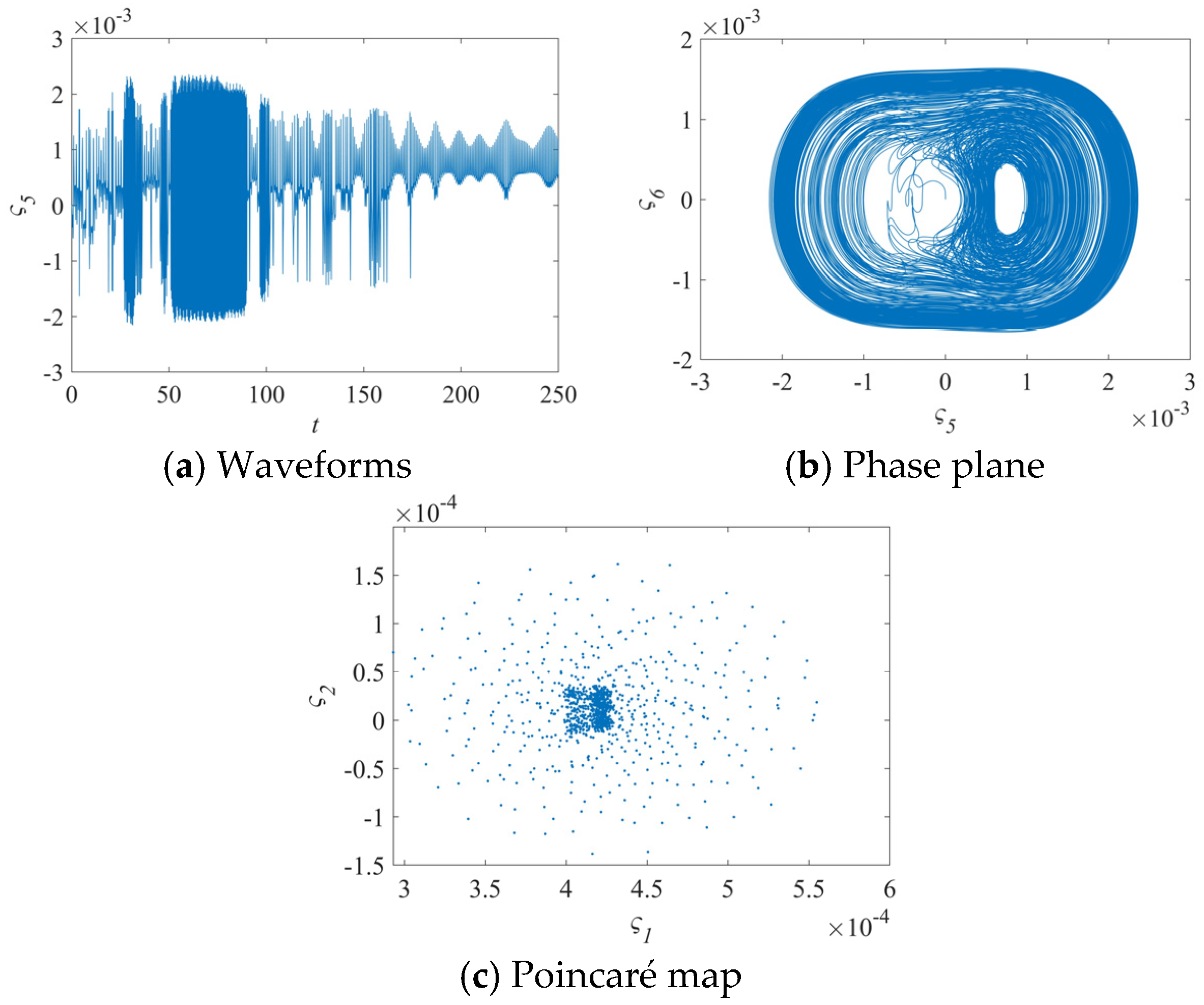

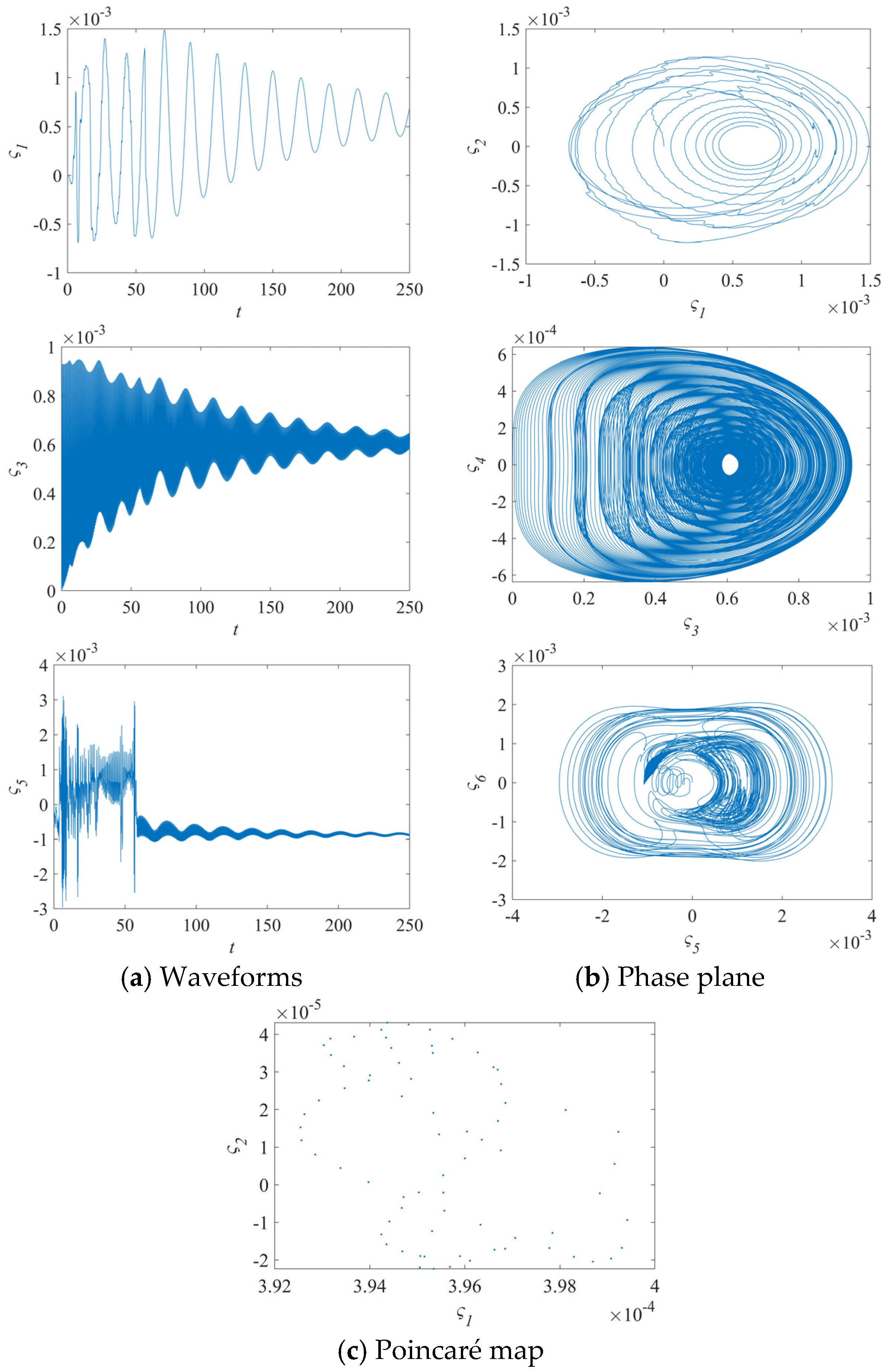

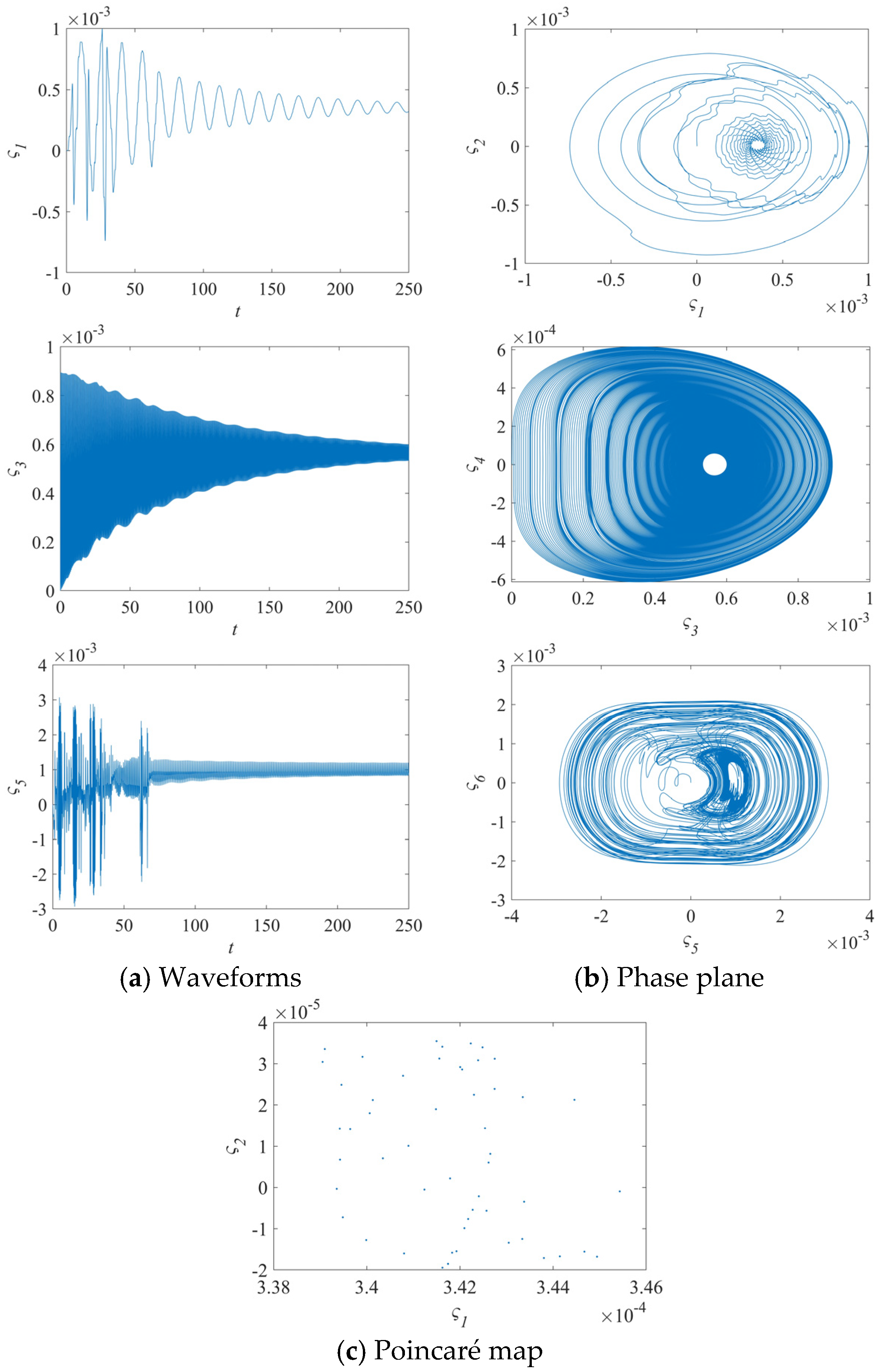

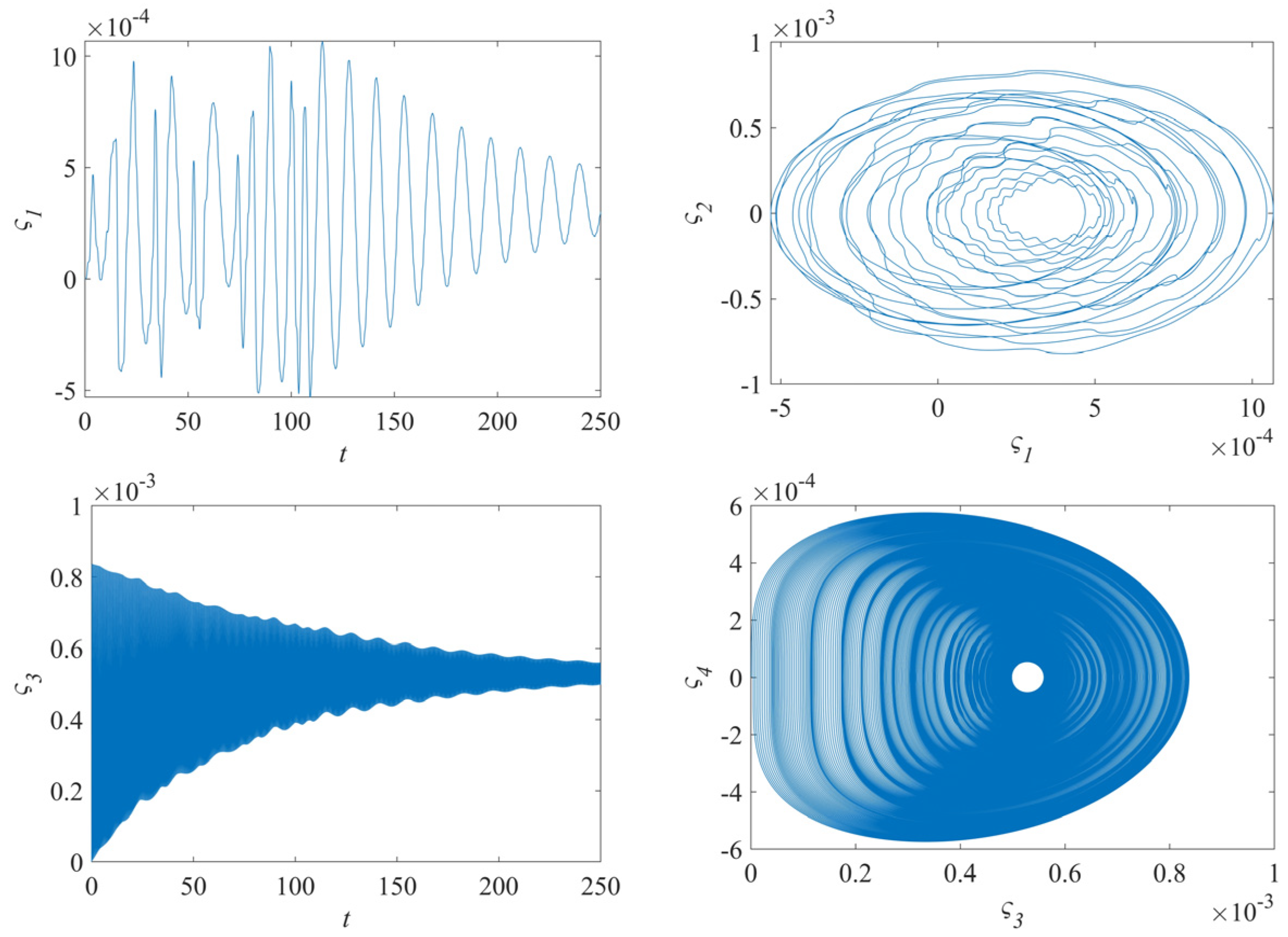

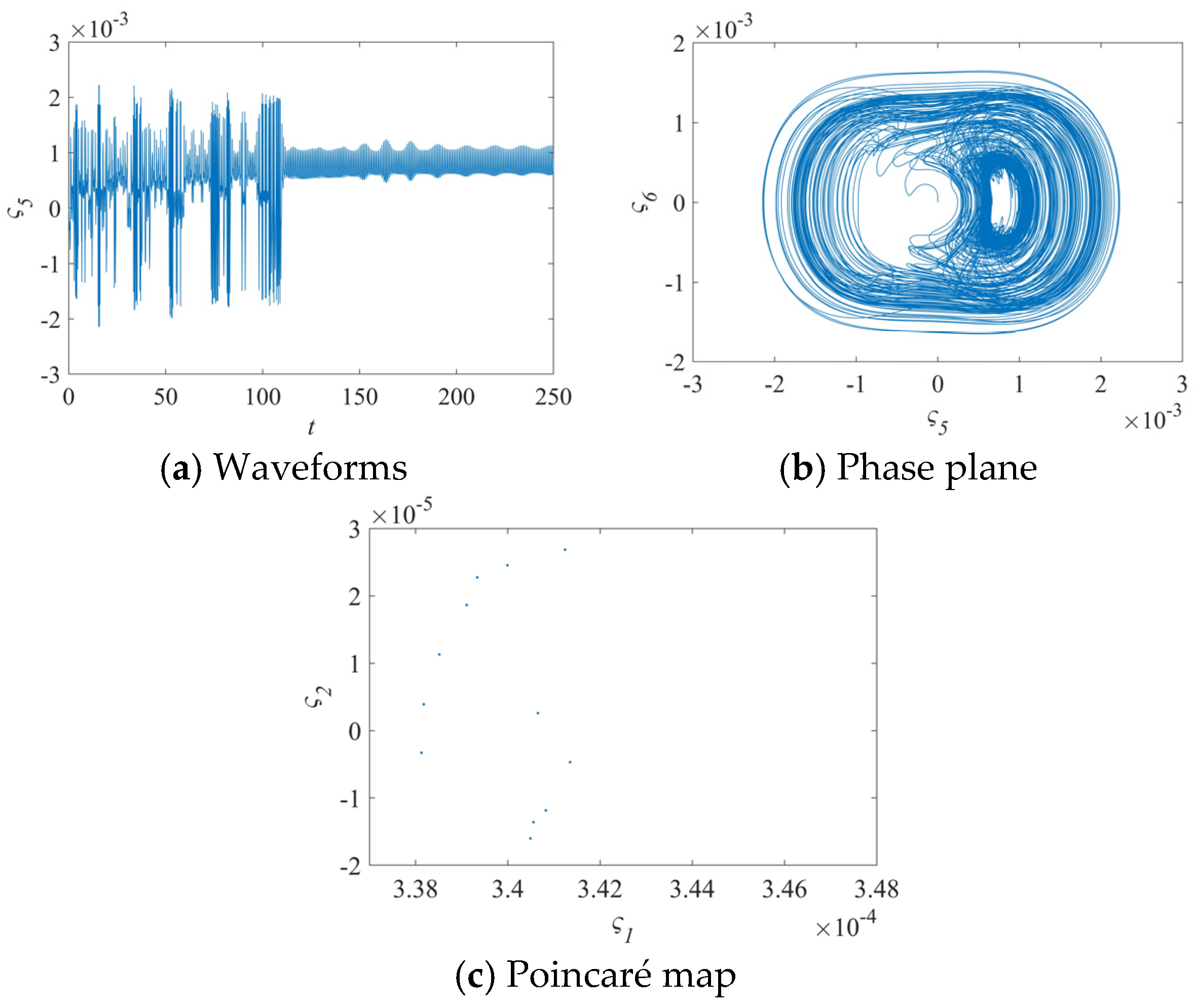

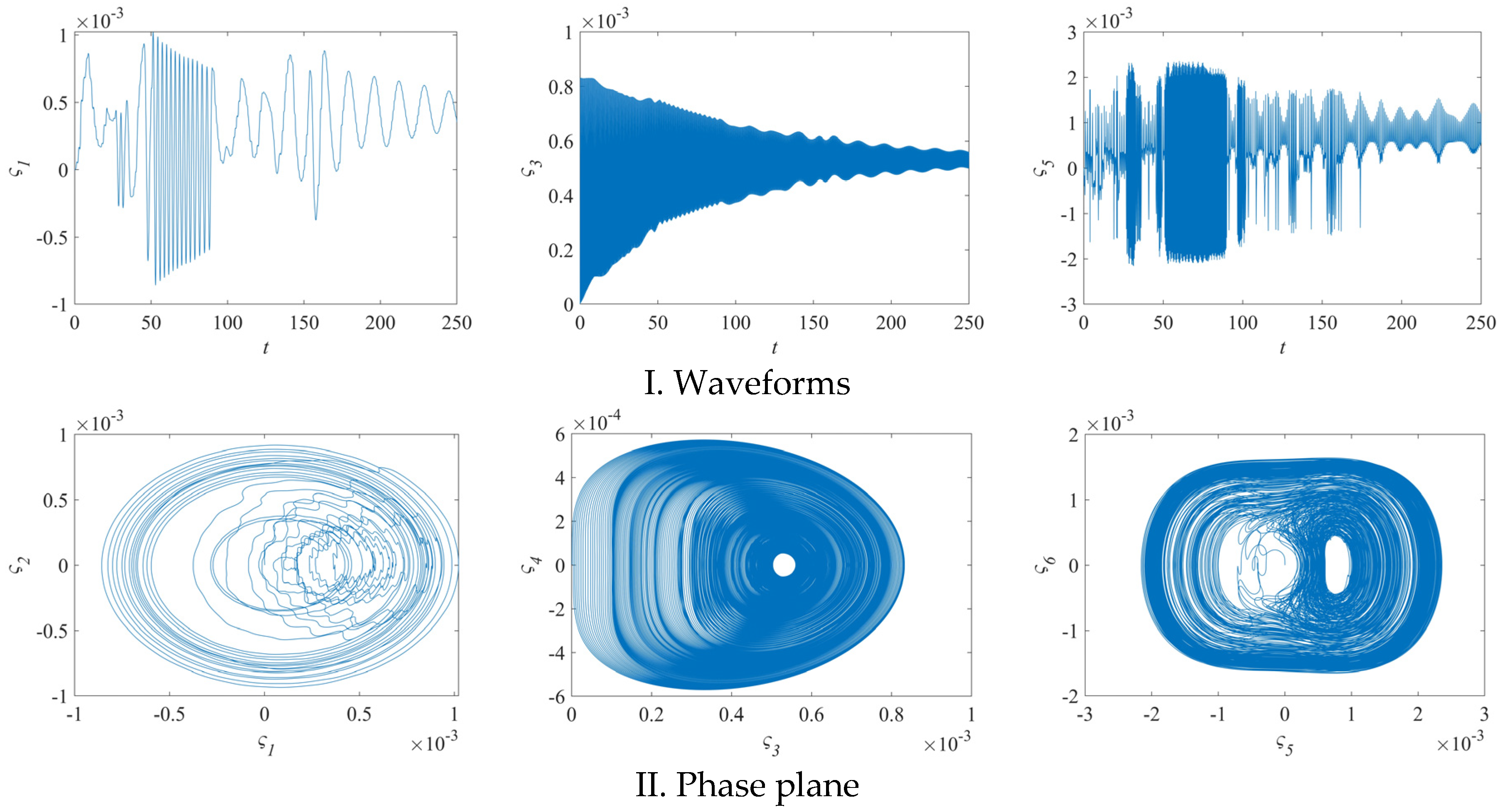

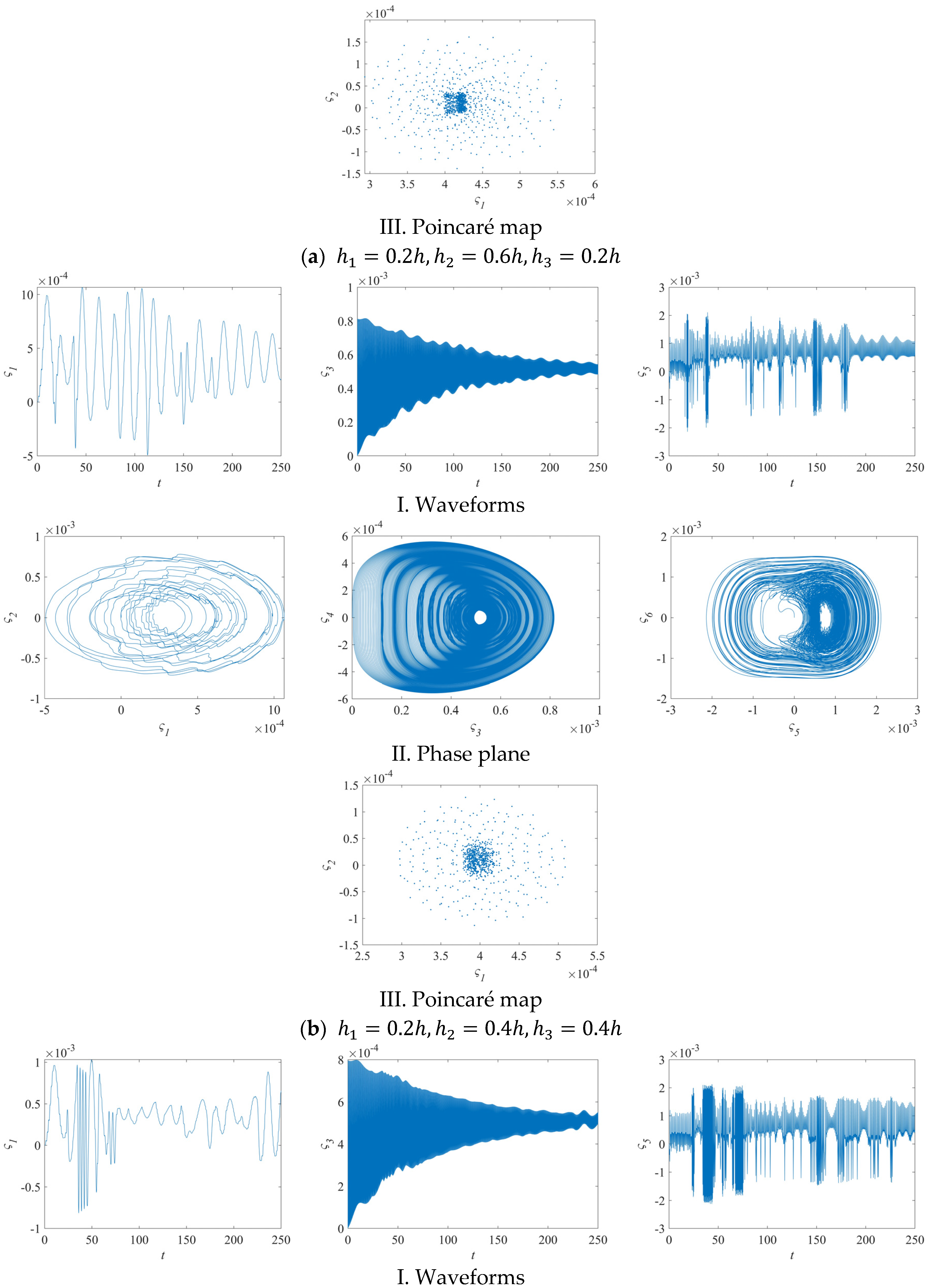

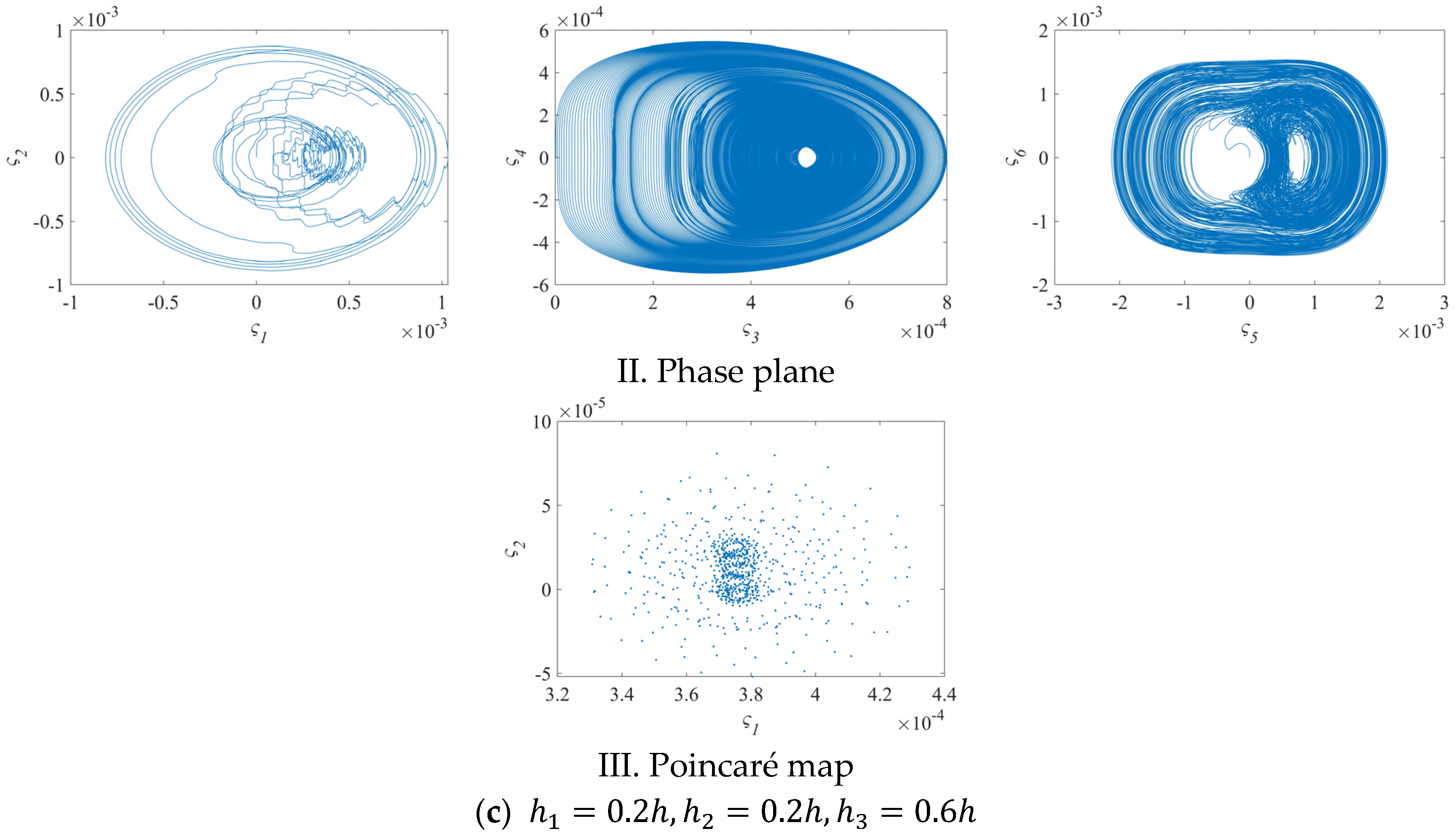

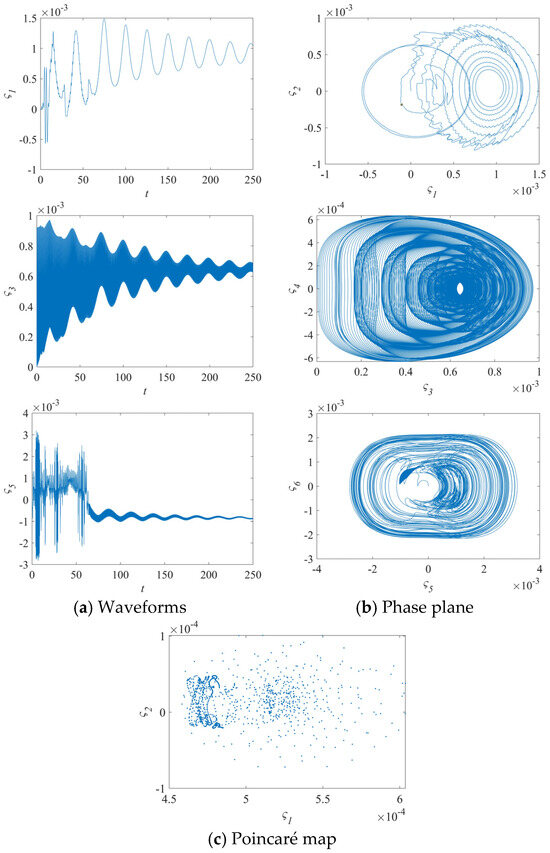

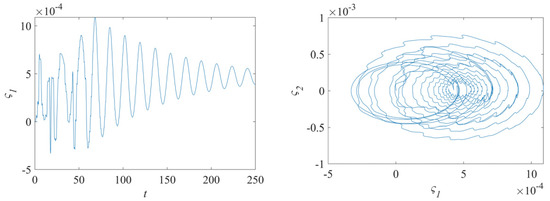

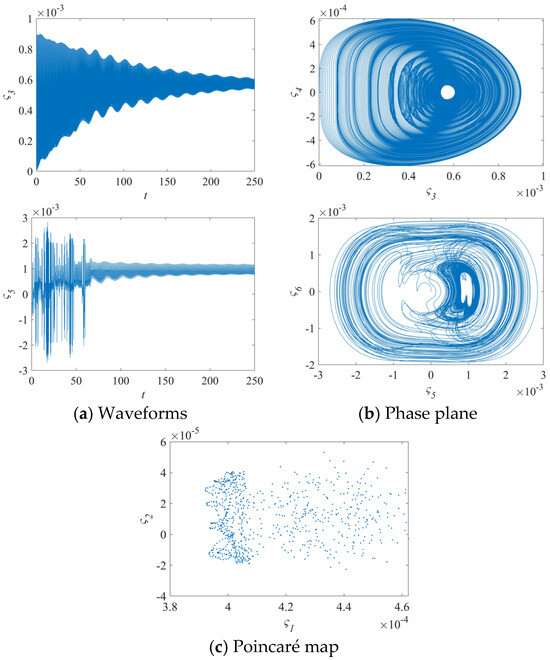

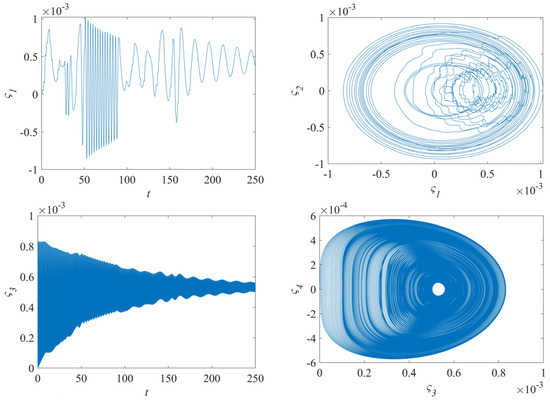

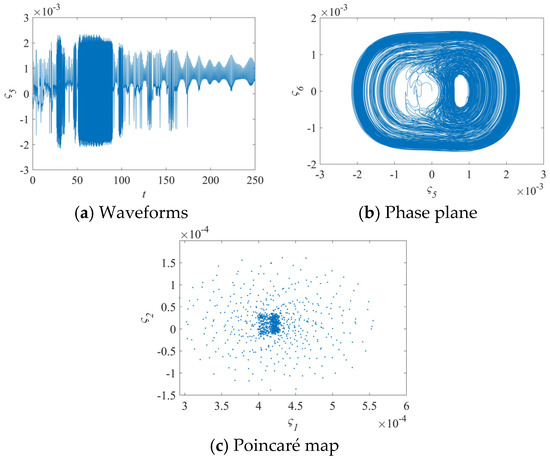

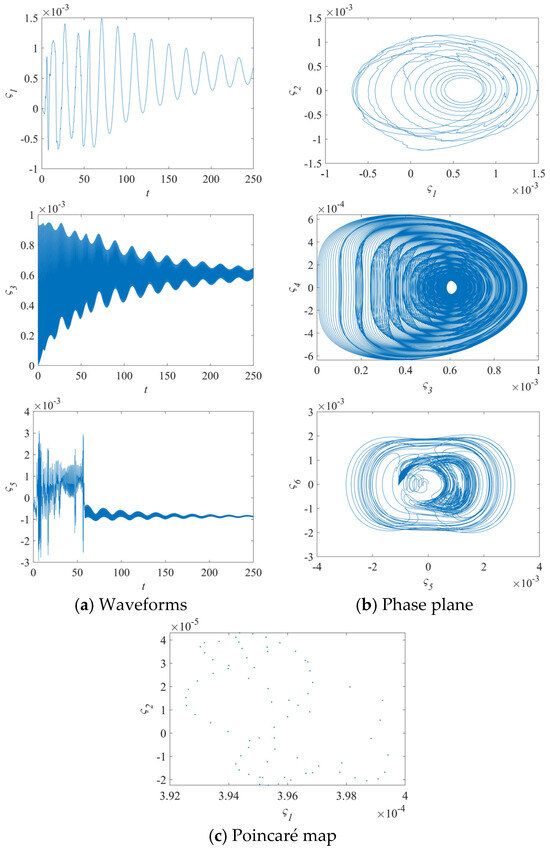

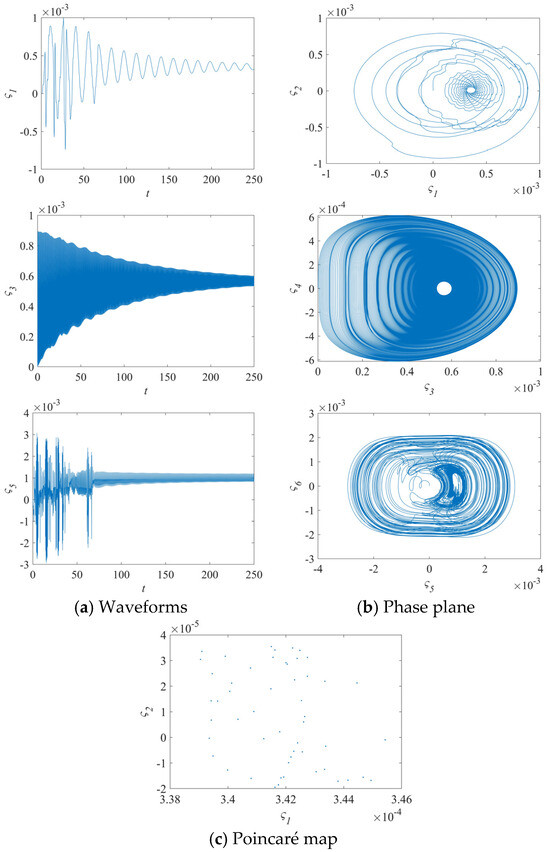

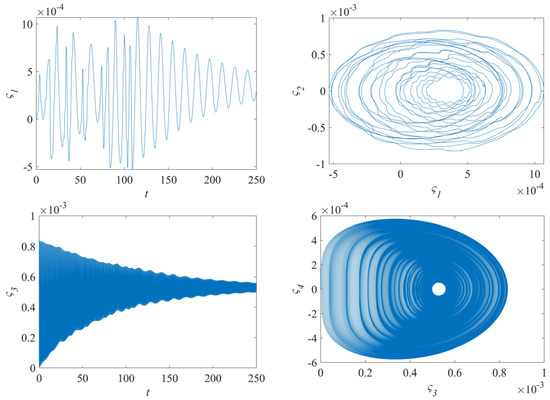

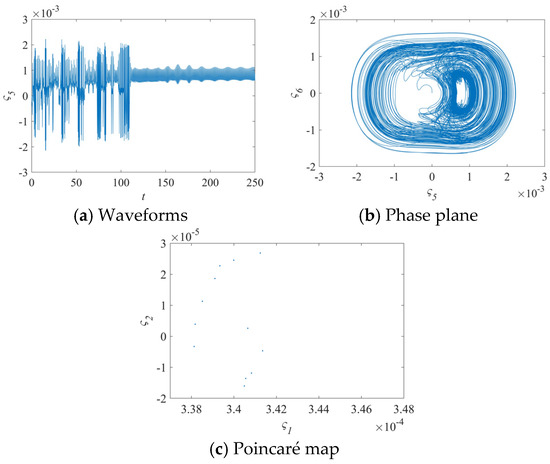

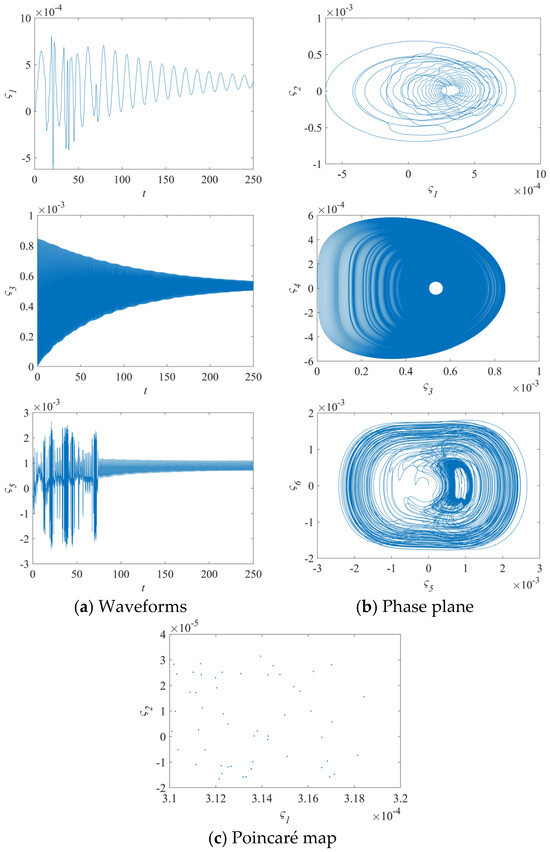

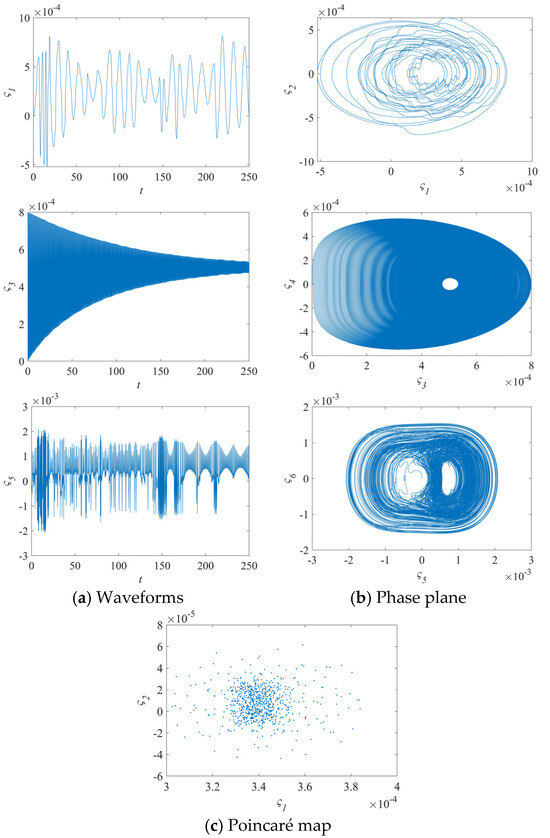

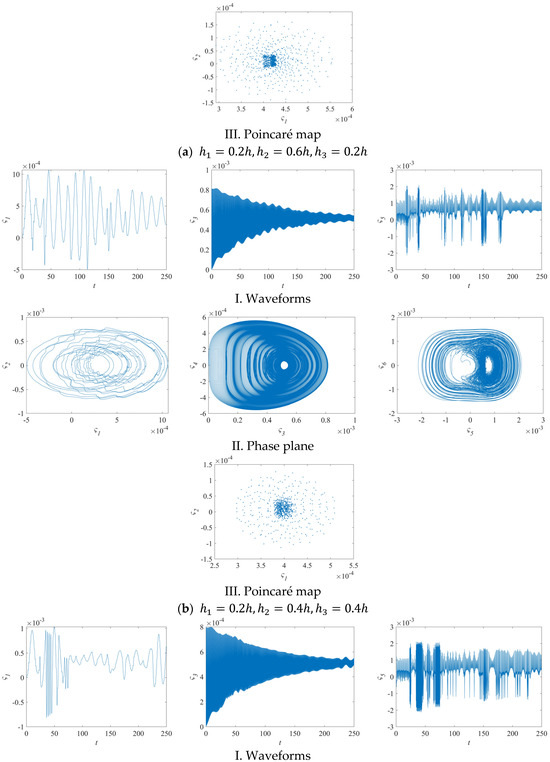

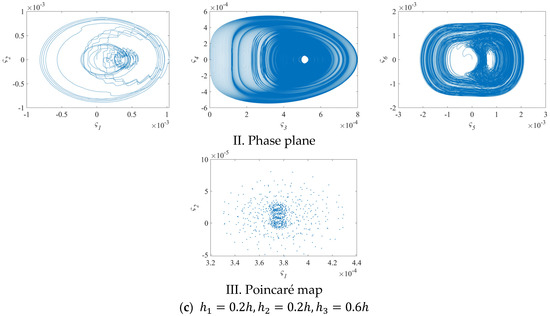

The impacts of the stiffener angle on the NV behavior and the NV phase plane of OSMFG-CSs with a superharmonic of order 3/1 and an internal resonance of 1:1/3:1/9 for the first three modes are revealed in Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. Regarding the outcomes, the vibration amplitudes of OSMFG-CSs in the first mode with stiffener angles of and , in the second mode when one of the stiffener angles is (either or ), and in the third mode with stiffeners angles of and or , are less than others. Conversely, the vibration amplitudes of OSMFG-CSs in the first mode with stiffener angles of and or , OSMFG-CSs in the second mode with stiffener angles of and , and OSMFG-CSs in the third mode with stiffener angles of and or or were larger than the others. Additionally, the results indicate that the time-domain curves of OSMFG-CSs in the first mode with stiffener angles of and or , OSMFG-CSs in the second mode with stiffener angles of and , and OSMFG-CSs in the third mode with stiffener angles of and or reach stability earlier than the others. In addition, the outcomes illustrate that OSMFG-CSs with various stiffener angles demonstrate periodic, quasi-periodic, or chaotic motion. In this regard, OSMFG-CSs exhibit chaotic motion at stiffener angles of and or or , as well as and . Conversely, OSMFG-CSs undergo quasi-periodic motion at stiffener angles of and or , and , and multiple periodic motions at stiffener angles of and .

Figure 4.

NV responses of OSMFG-CSs ().

Figure 5.

NV responses of OSMFG-CSs ().

Figure 6.

NV responses of OSMFG-CSs ().

Figure 7.

The NV responses of OSMFG-CSs ().

Figure 8.

NV responses of OSMFG-CSs ().

Figure 9.

NV responses of OSMFG-CSs ().

Figure 10.

NV responses of OSMFG-CSs ().

Figure 11.

NV responses of OSMFG-CSs ().

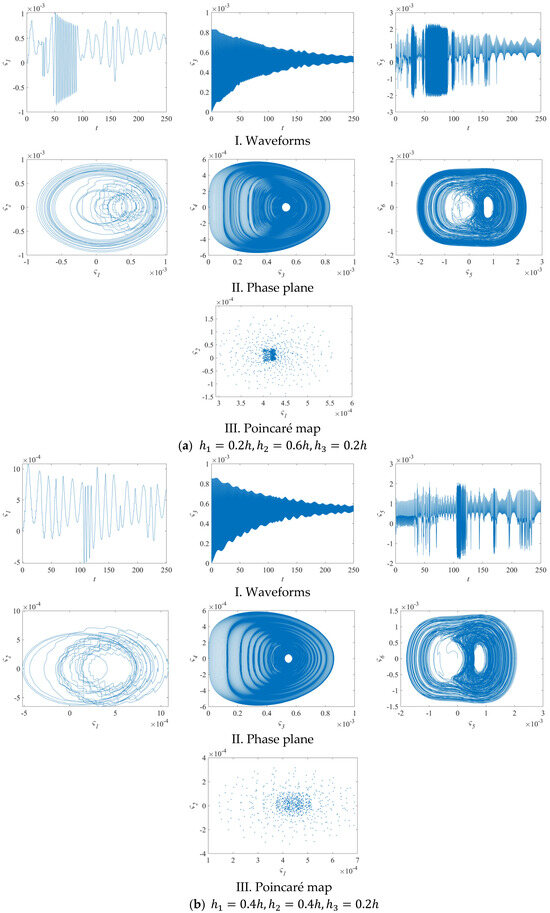

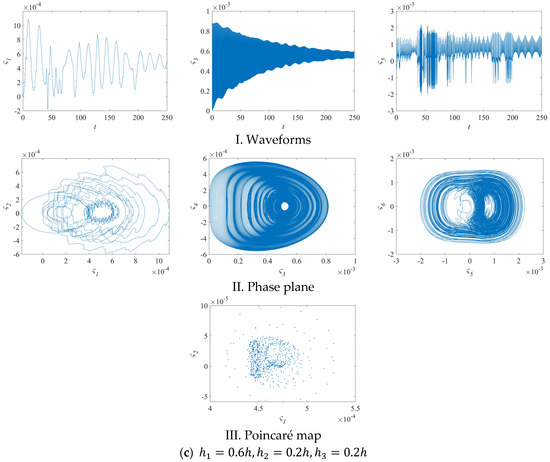

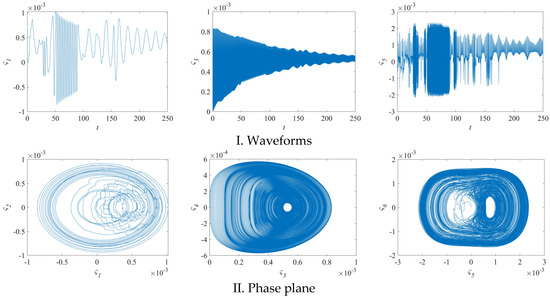

Figure 12 and Figure 13 illustrate the impact of the thickness of the shell layers on the NV responses of OSMFG-CSs. As shown in these figures, increasing the ceramic layer thickness generally increases the vibration amplitude in all three modes. Specifically, when the metal layer thickness equals that of the FG layer, the vibration amplitude significantly increases in the first mode but decreases in the third mode. Additionally, enhancing the ceramic layer thickness leads to a reduction in the vibration amplitude in the second and third modes. However, with a metal layer thickness equal to that of the FG layer, there is an increase in the vibration amplitude in the first mode. Also, the outcomes illustrate that OSMFG-CSs with stiffener angles of and for various shell layer thicknesses exhibit chaotic motion.

Figure 12.

Effect of thickness of metal shell layer on nonlinear vibration responses of OSMFG-CSs ().

Figure 13.

Effect of thickness of ceramic shell layer on nonlinear vibration responses of OSMFG-CSs ().

4. Conclusions

A semi-analytical approach was used to examine the NV behavior of OS-MFG-CSs under external excitation. The NV problem of OSMFG-CSs was addressed utilizing the smeared stiffener technique, classical shell theory, von Kármán equations, and the Galerkin approach. Then, the MMSs was applied to examine the NV of OSMFG-CSs. The resonant case considered here was an internal resonance of 1:1/3:1/9 and a superharmonic of order 3/1. The influences of the geometrical characteristics on the NV behavior of OSMFG-CSs were investigated. The following is a summary of some of the key findings:

- The vibration amplitude of OSMFG-CSs is lower for specific stiffener angle configurations, including and in the first mode, either or in the second mode, and and or in the third mode. Conversely, higher vibration amplitudes are observed in the configurations where and or in the first mode, and in the second mode, and and or or in the third mode.

- OSMFG-CSs exhibit chaotic motion at stiffener angles of and or or , and and . Conversely, OSMFG-CSs show quasi-periodic motion at stiffener angles of and or , and , and multiple periodic motion at stiffener angles of and .

- Increasing the ceramic layer thickness generally raises the vibration amplitude across all three modes. However, when the metal and FG layer thicknesses are equal, the first mode’s amplitude increases significantly while that of the third mode decreases. Additionally, a thicker ceramic layer reduces the vibration amplitude in the second and third modes, except when the thicknesses of the metal layer and the FG layer are the same, which increases the first mode’s amplitude.

The insights gained from the current analysis can be utilized in the design and optimization of aerospace structures, such as rocket casings and fuselage components, where resistance to dynamic loads and material efficiency are critical. Additionally, these findings contribute to the automotive industry, particularly in the development of more resilient and lighter vehicle frames that experience less wear and tear due to vibration. Also, by integrating the present semi-analytical approach into the early stages of design and material selection, engineers can predict the vibration behavior of these complex structures more accurately, leading to safer and more cost-effective constructions. Moreover, the adaptability of the current method to different materials and geometries can help with customizing solutions for specific application needs, thereby enhancing the structural integrity and longevity of the cylindrical shells used in high-performance applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.F. and F.T.; Methodology, K.F.; Software, K.F.; Validation, K.F. and F.T.; Formal analysis, K.F.; Investigation, K.F. and F.T.; Writing—original draft, K.F.; Writing—review & editing, F.T.; Visualization, K.F. and F.T.; Supervision, F.T.; Funding acquisition, F.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partially supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) (Grant No. RGPIN-2024-06363), awarded to Farshid Torabi.

Data Availability Statement

The data are contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Nomenclature

| Ceramic | |

| Width of stiffeners | |

| Young’s modulus | |

| Thickness of CSs and stiffeners, respectively | |

| Thickness of metal, FG, and ceramic layers, respectively | |

| Length of CSs | |

| Bending and twisting moment intensities | |

| Metal | |

| In-plane normal force and shearing force intensities | |

| Material power law index of FG layer of CSs and stiffeners, respectively | |

| Excitation | |

| Radius of CSs | |

| Stiffener spacing | |

| Displacements through the , axes, respectively | |

| Deflection of CSs | |

| Angles of stiffeners | |

| Poisson’s ratio | |

| Damping coefficient | |

| Densities of CSs and stiffeners, respectively | |

| Stress function |

Appendix A

The coefficients in Equations (7) and (8) are as follows:

where

Appendix B

The coefficients in Equations (14) and (15) are

References

- Civalek, Ö. Nonlinear dynamic response of laminated plates resting on nonlinear elastic foundations by the discrete singular convolution-differential quadrature coupled approaches. Compos. B Eng. 2013, 50, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.S.; Xiang, Y. Nonlinear vibration of nanotube-reinforced composite cylindrical shells in thermal environments. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2012, 213, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornabene, F.; Viscoti, M.; Dimitri, R. Higher order theories for the free vibration analysis of laminated anisotropic doubly-curved shells of arbitrary geometry with general boundary conditions. Compos. Struct. 2022, 297, 115740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, E.; Pagani, A.; Azzara, R.; Augello, R. Vibration of metallic and composite shells in geometrical nonlinear equilibrium states. Thin Wall. Struct. 2020, 157, 107131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.H.; Chai, Q.; Wang, Y.Q. Free vibration of spinning stepped functionally graded circular cylindrical shells in a thermal environment. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2024, 53, 2075–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofiyev, A.H.; Hui, D.; Valiyev, A.A.; Kadioglu, F.; Turkaslan, S.; Yuan, G.Q.; Kalpakci, V.; Özdemir, A. Effects of shear stresses and rotary inertia on the stability and vibration of sandwich cylindrical shells with FGM core surrounded by elastic medium. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2016, 44, 384–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefi, M.; Karroubi, R.; Irani-Rahaghi, M. Free vibration analysis of functionally graded laminated sandwich cylindrical shells integrated with piezoelectric layer. Appl. Math. Mech. 2016, 37, 821–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, K.; Torabi, F. Nonlinear dynamic analyses of sandwich porous FG cylindrical shells with dual-layered FG porous cores. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bich, D.H.; Ninh, D.G. An analytical approach: Nonlinear vibration of imperfect stiffened FGM sandwich toroidal shell segments containing fluid under external thermo-mechanical loads. Compos. Struct. 2017, 162, 164–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D.Q.; Anh, V.T.T.; Duc, N.D. Vibration and nonlinear dynamic response of eccentrically stiffened functionally graded composite truncated conical shells surrounded by an elastic medium in thermal environments. Acta Mech. 2019, 230, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahranifard, F.; Malekzadeh, P.; Golbahar Haghighi, M.R.; Malakouti, M. Free vibration of point supported ring-stiffened truncated conical sandwich shells with GPLRC porous core and face sheets. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2024, 52, 6142–6172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bich, D.H.; Van Dung, D.; Nam, V.H. Nonlinear dynamic analysis of eccentrically stiffened imperfect functionally graded doubly curved thin shallow shells. Compos. Struct. 2013, 96, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, T.M.; Loi, N.V. Vibration analysis of rotating functionally graded cylindrical shells with orthogonal stiffeners. Lat. Am. J. Solids Struct. 2016, 13, 2952–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.N.; Kanwal, S.; Shah, A.G.; Arshad, S.H.; Mahmood, T. Vibration Characteristics of Ring-Stiffened Functionally Graded Circular Cylindrical Shells. Int. Sch. Res. Not. 2012, 2012, 232498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebitooti, M.; Daneshjou, K.; Talebitooti, R. Vibration and critical speed of orthogonally stiffened rotating FG cylindrical shell under thermo-mechanical loads using differential quadrature method. J. Therm. Stress. 2013, 36, 160–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.F. Nonlinear resonant responses of hyperelastic cylindrical shells with initial geometric imperfections. Chaos Soliton. Fract. 2023, 173, 113709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.F.; Zhang, W.; Yao, Z.G. Analysis on nonlinear vibrations near internal resonances of a composite laminated piezoelectric rectangular plate. Eng. Struct. 2018, 173, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, T.; Xi, A.; Wang, Y.N. Resonant responses and chaotic dynamics of composite laminated circular cylindrical shell with membranes. J. Sound Vib. 2018, 423, 65–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, A.; Kobayashi, Y.; Yamada, G. Nonlinear dynamic behaviors of clamped laminated shallow shells with one-to-one internal resonance. J. Sound Vib. 2007, 304, 957–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Gao, W.; Wu, B.; Wu, D.; Song, C. Nonlinear primary resonance of functionally graded porous cylindrical shells using the method of multiple scales. Thin Wall. Struct. 2018, 125, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Li, Y. Nonlinear resonance behavior of functionally graded cylindrical shells in thermal environments. Compos. Struct. 2013, 102, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, R.; Gholami, R. Nonlinear primary resonance of third-order shear deformable functionally graded nanocomposite rectangular plates reinforced by carbon nanotubes. Compos. Struct. 2016, 154, 707–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aris, H.; Ahmadi, H. Nonlinear forced vibration and resonance analysis of rotating stiffened FGM truncated conical shells in a thermal environment. Mech. Based Des. Struct. Mach. 2023, 51, 4063–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Bayat, A.; Duc, N.D. Nonlinear forced vibrations analysis of imperfect stiffened FG doubly curved shallow shell in thermal environment using multiple scales method. Compos. Struct. 2021, 256, 113090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.G.; Wang, X. The dynamic stability and nonlinear vibration analysis of stiffened functionally graded cylindrical shells. Appl. Math. Model. 2018, 56, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Wu, X.; Xiao, Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, J. Vibro-acoustic characteristics of eccentrically stiffened functionally graded material sandwich cylindrical shell under external mean fluid. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 91, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, K.; Torabi, F. Influence of Spiral Stiffeners’ Symmetric and Asymmetric Angles on Nonlinear Vibration Responses of Multilayer FG Cylindrical Shells. Symmetry 2024, 16, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, D.O.; Almroth, B.O. Buckling of Bars, Plates, and Shells; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Volmir, A.S. Non-Linear Dynamics of Plates and Shells; Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union: Moscow, Russia, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Phuong, N.T.; Nam, V.H.; Trung, N.T.; Duc, V.M.; Phong, P.V. Nonlinear stability of sandwich functionally graded cylindrical shells with stiffeners under axial compression in thermal environment. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2019, 19, 1950073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, G.G.; Wang, X.; Fu, G.; Hu, H. The nonlinear vibrations of functionally graded cylindrical shells surrounded by an elastic foundation. Nonlinear Dynam. 2014, 78, 1421–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.G.; Chen, Z.P.; Feng, W.Z.; Zhou, F.; Cao, G.W. Dynamic buckling of cylindrical shells with arbitrary axisymmetric thickness variation under time dependent external pressure. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 2015, 15, 1450053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.W.; Zhang, W.; Mao, J.J. Nonlinear vibrations of carbon fiber reinforced polymer laminated cylindrical shell under non-normal boundary conditions with 1: 2 internal resonance. Eur. J. Mech. A Solids 2019, 74, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Liu, G.R.; Lam, K.Y. Vibration analysis of thin cylindrical shells using wave propagation approach. J. Sound Vib. 2001, 239, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.G.; Li, F.M. Aerothermoelastic analysis and active flutter control of supersonic composite laminated cylindrical shells. Compos. Struct. 2013, 106, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).