Data Acquisition and Chatter Recognition Based on Multi-Sensor Signals for Blade Whirling Milling

Abstract

:1. Introduction

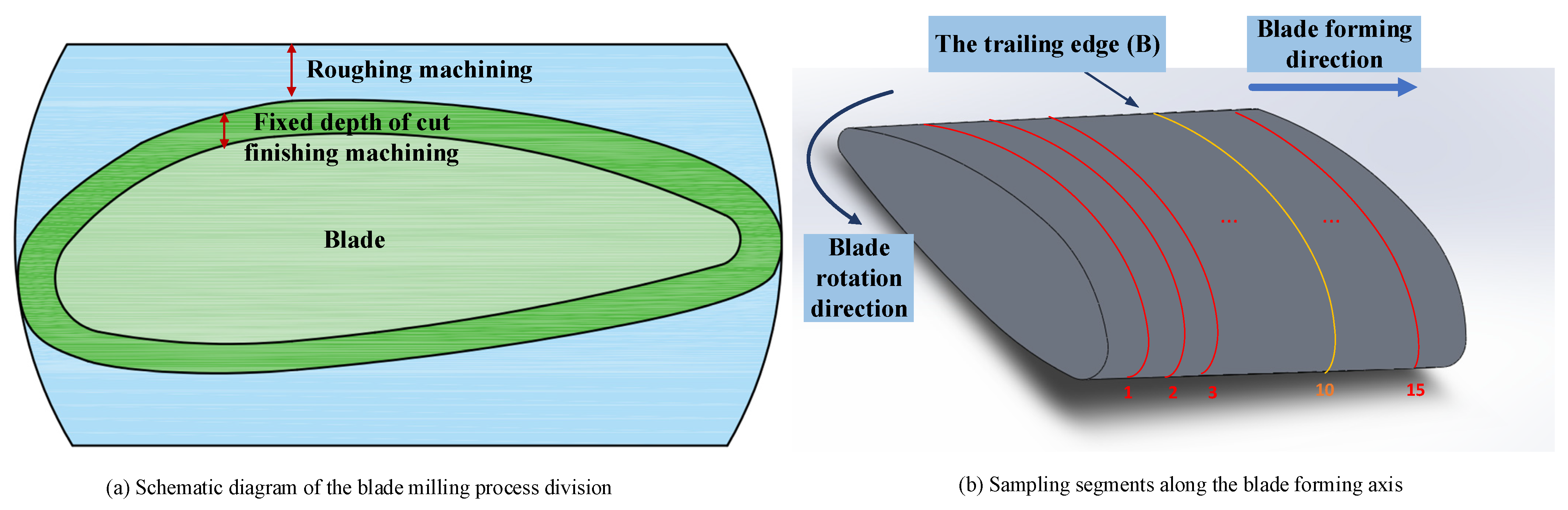

2. Overview of the Whirling Milling Process of Blades

3. Data Acquisition

3.1. Experimental Setup

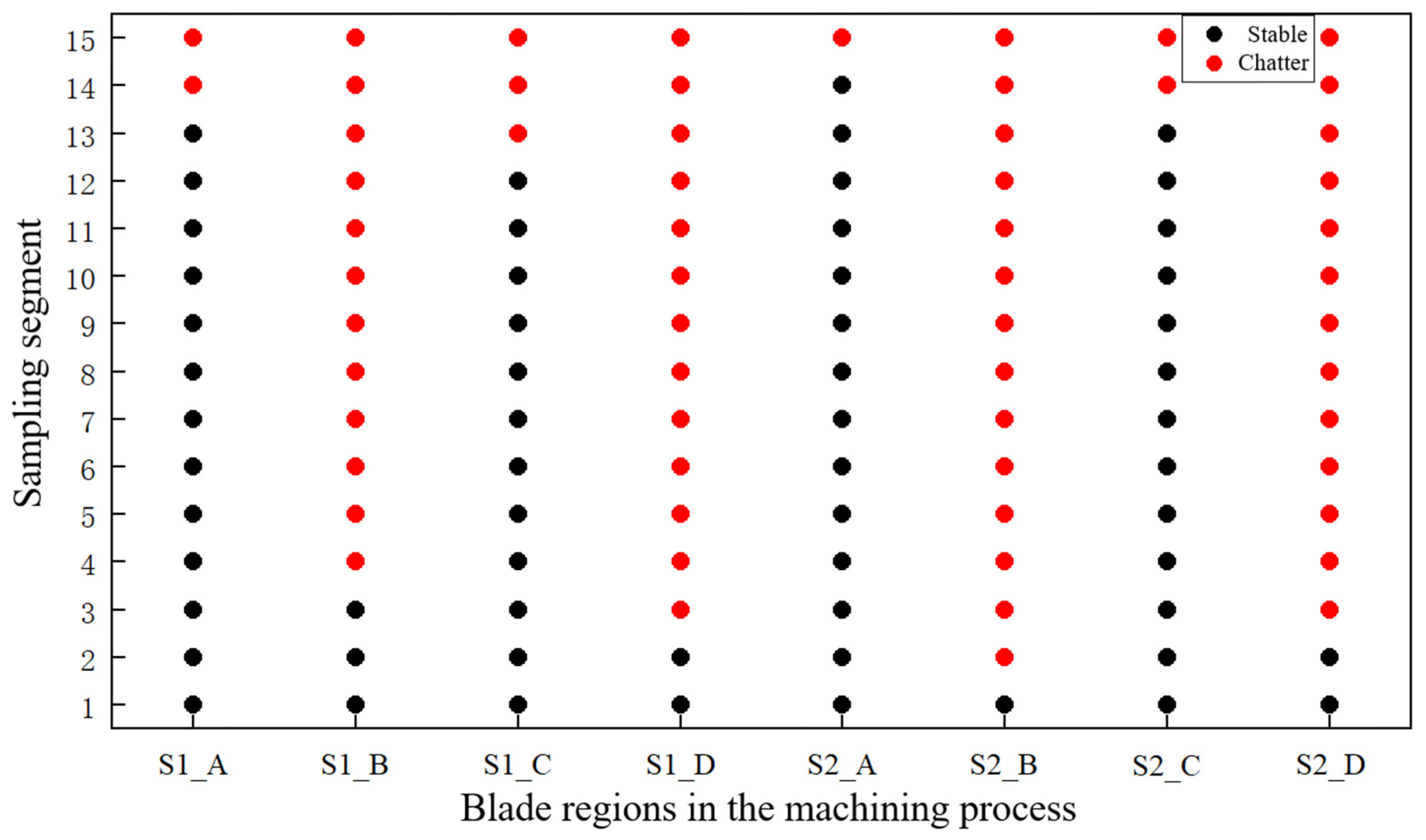

3.2. Experimental Cuts and Data Acquisition

4. Chatter Recognition Validation

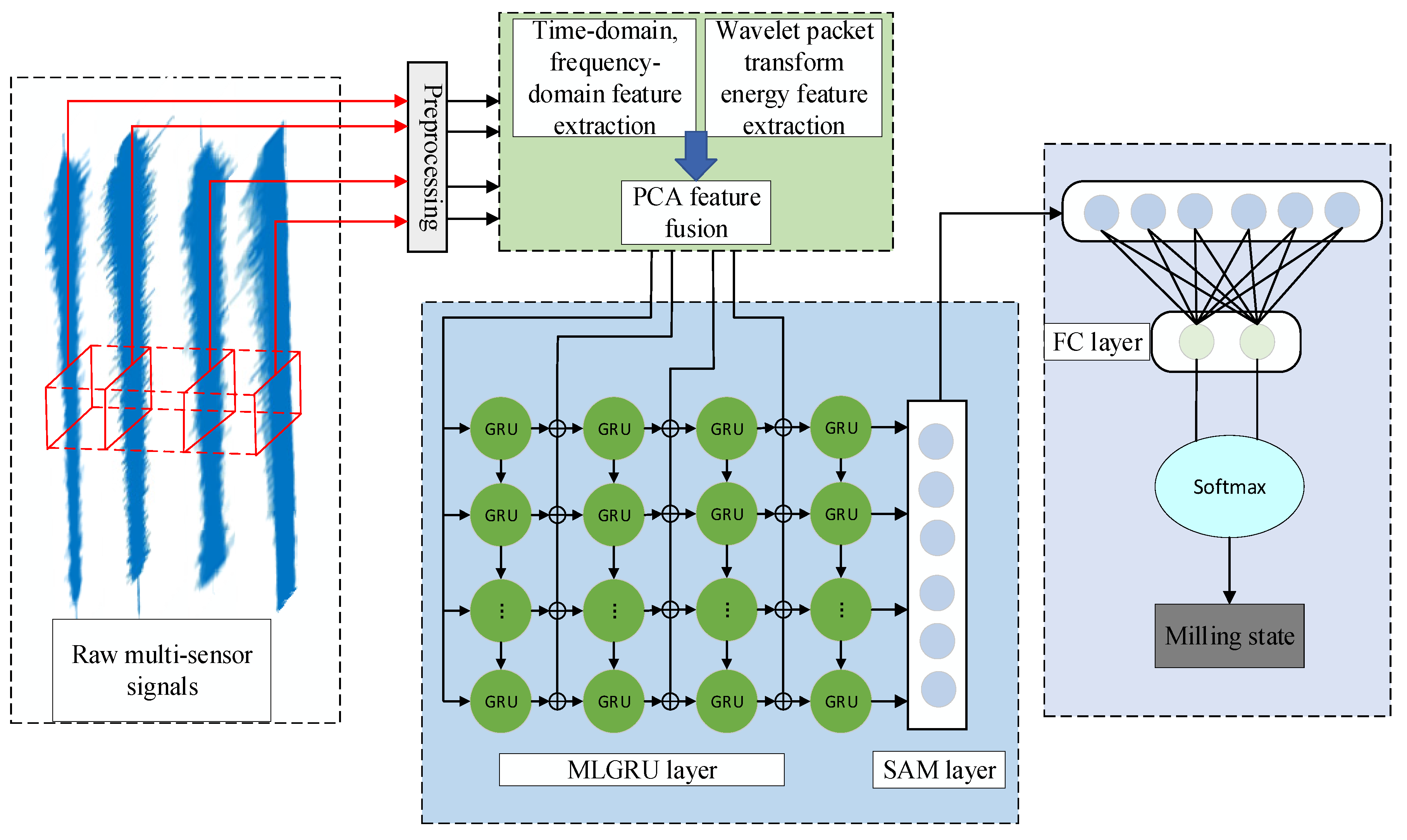

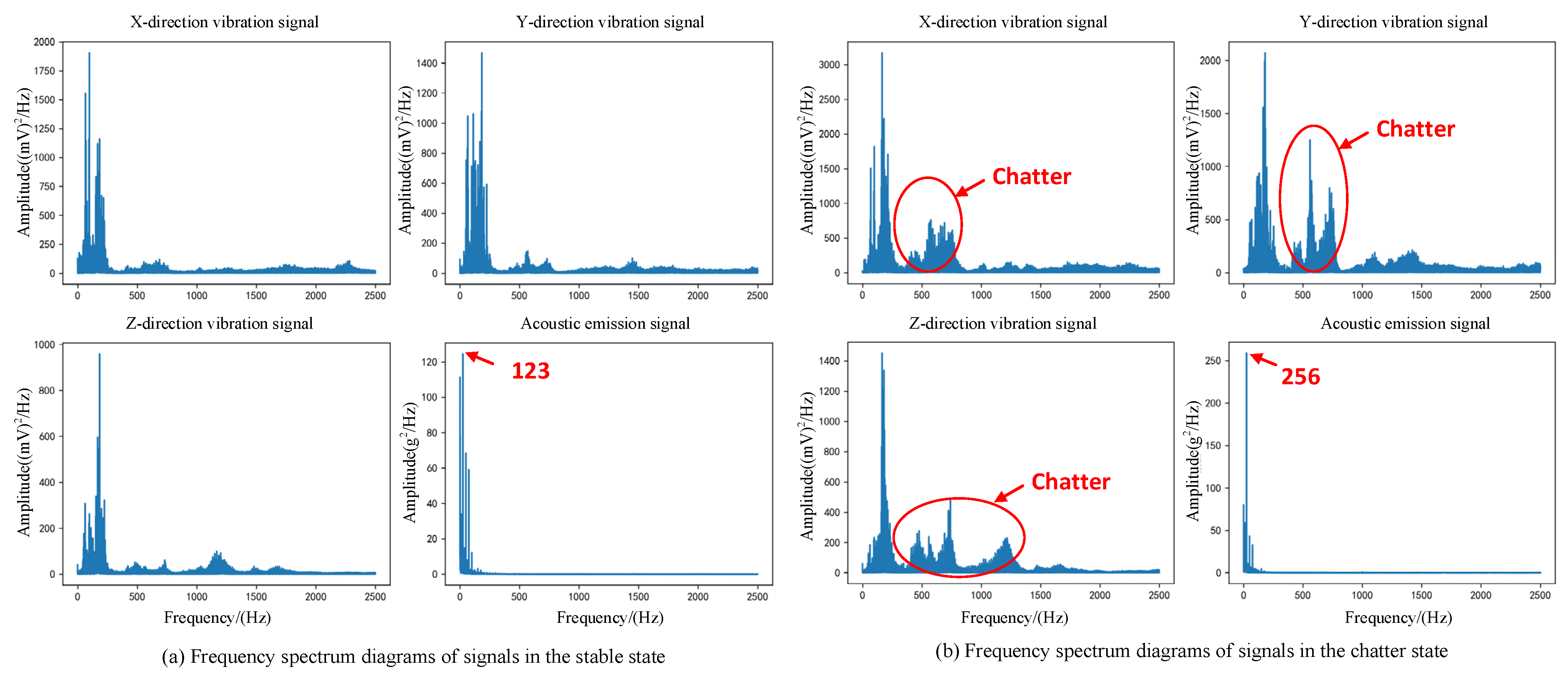

4.1. Multi-Signal Feature Selection and Fusion

4.2. Chatter Recognition Model Based on PCA-MLGRU-SAM

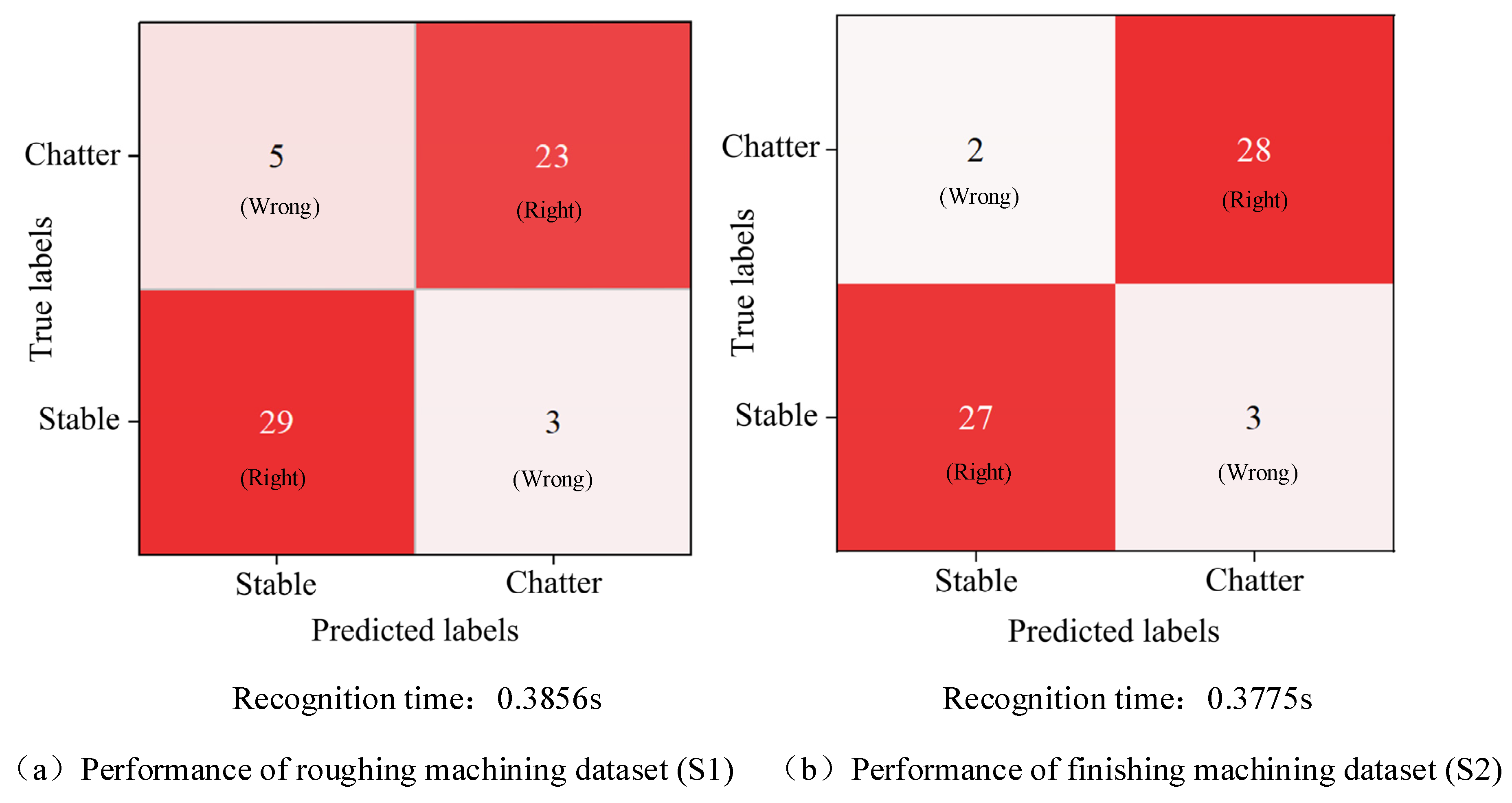

4.3. Chatter Recognition Result Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia, Z.; Ma, J.; Song, D.; Wang, F.; Liu, W. A review of contouring-error reduction method in multi-axis CNC machining. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2018, 125, 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, X.; Zhang, W.; Meng, G. Chatter mitigation for the milling of thin-walled workpiece. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2018, 138, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Liu, R.; Liu, X. Modal parameter determination and chatter prediction for blade whirling: A comparative study based on symmetric and asymmetric FRF. Adv. Manuf. 2021, 9, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanger, F.; Sellmeier, V.; Klose, J.; Bartkowiak, M.; Schulze, V. Comparison of modeling methods to determine cutting tool profile for conventional and synchronized whirling. Procedia Cirp. 2017, 58, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omirou, S.; Charalambides, M.; Chasos, C. Advanced CNC thread milling: A comprehensive canned cycle for efficient cutting of threads with fixed or variable pitch and radius. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 133, 2219–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; He, Y.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Predicting residual properties of ball screw raceway in whirling milling based on machine learning. Measurement 2021, 173, 108605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botak, Z.; Pisačić, K.; Horvat, M.; Tomić, T. Determination of Optimal Machining Parameters Based on Roughness and Vibration Measurements of Pieces Produced by Whirling on a Lathe Machine. Machines 2024, 12, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merticaru, V.; Nagîț, G.; Dodun, O.; Merticaru, E.; Rîpanu, M.I.; Mihalache, A.M.; Slătineanu, L. Influence of Machining Conditions on Micro-Geometric Accuracy Elements of Complex Helical Surfaces Generated by Thread Whirling. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Cao, H.; Tao, G.; Yi, H.; Chen, Z. Recent Progress of Chatter Detection and Tool Wear Online Monitoring in Machining Process: A Review and Future Prospects. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Green Technol. 2024, 143, 106840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Li, X.; Yin, Y.; Hong, J. Milling chatter detection by multi-feature fusion and Adaboost-SVM. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 156, 107671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Gao, D.; Hong, D.; Lu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zan, S.; Liao, Z. Improving generalisation and accuracy of on-line milling chatter detection via a novel hybrid deep convolutional neural network. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 193, 110241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Sun, Y.; Xiong, Z. Online chatter suppression in turning by adaptive amplitude modulation of spindle speed variation. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2018, 140, 121003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Ma, H.; Sun, Y.; Song, Q.; Liu, Z.; Xiong, Z. An interpretable anti-noise convolutional neural network for online chatter detection in thin-walled parts milling. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2024, 206, 110885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Zhu, L.; Ni, C. Chatter detection in milling process based on VMD and energy entropy. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 105, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Huang, X.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, M. An intelligent chatter detection method for high-speed milling under variable tool-workpiece systems and cutting parameters. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 111960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frumusanu, G.R.; Constantin, I.C.; Marinescu, V.; Epureanu, A. Development of a stability intelligent control system for turning. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 64, 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoa, J.; Beudaert, X.; Dombovari, Z.; Altintas, Y.; Budak, E.; Brecher, C.; Stepan, G. Chatter suppression techniques in metal cutting. CIRP Ann. 2016, 65, 785–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Song, Q.; Jin, P.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Ma, H. Chatter suppression techniques in milling processes: A state of the art review. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2024, 37, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrelli, M.; Cosco, F.; Gagliardi, F.; Mundo, D. In-process chatter detection using signal analysis in frequency and time-frequency domain. Machines 2021, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krajnik, P.; Kopač, J. Modern machining of die and mold tools. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2004, 157, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavruska, P.; Pesice, M.; Zeman, P.; Kozlok, T. Automated feed rate optimization with consideration of angular velocity according to workpiece shape. Results Eng. 2022, 16, 100762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.K.; Wan, M.; Zhang, W.H.; Yang, Y. Chatter detection methods in the machining processes: A review. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 77, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Devia, J.H.; Chen, Y.; Dao, D.V.; Li, H. Chatter detection in milling processes—A review on signal processing and condition classification. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 125, 3943–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Liu, R.; Liu, X.; Feng, J. Theoretical modeling and chatter prediction for the whirling process of airfoil blades with consideration of asymmetric FRF and material removal. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 106, 2613–2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Liu, R.; Li, Y. Adapting whirling process for CNC manufacture of bespoke screws with variable pitch and diameters. Int. J. Manuf. Res. 2020, 15, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Liu, R. An MLGRU and SAM-based Approach to Milling Chatter Detection using Multi-sensor Data. Eng. Res. Express, 2024; accepted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akl, A.; El-Henawy, I.; Salah, A.; Li, K. Optimizing deep neural networks hyperparameter positions and values. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 37, 6665–6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Spindle Speed (rpm) | Cutting Depth (mm) | Feed Rate (mm/min) | Lubrication Method | Cutting Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Roughing Machining | 1000 | 0.3–0.9 | 10, 20, 30, …, 150 | Cutting Fluid | Whirling Milling |

| Finishing Machining | 1000 | 0.3 | 10, 20, 30, …, 150 | Cutting Fluid | Whirling Milling |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, X.; Liu, R.; Zhu, Z. Data Acquisition and Chatter Recognition Based on Multi-Sensor Signals for Blade Whirling Milling. Machines 2025, 13, 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13030206

Li X, Liu R, Zhu Z. Data Acquisition and Chatter Recognition Based on Multi-Sensor Signals for Blade Whirling Milling. Machines. 2025; 13(3):206. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13030206

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Xinyu, Riliang Liu, and Zhiying Zhu. 2025. "Data Acquisition and Chatter Recognition Based on Multi-Sensor Signals for Blade Whirling Milling" Machines 13, no. 3: 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13030206

APA StyleLi, X., Liu, R., & Zhu, Z. (2025). Data Acquisition and Chatter Recognition Based on Multi-Sensor Signals for Blade Whirling Milling. Machines, 13(3), 206. https://doi.org/10.3390/machines13030206