Is It Necessary to Adapt Training According to the Menstrual Cycle? Influence of Contraception and Physical Fitness Variables

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Determination of the Phases of the Natural MC

- -

- Phase I: Where estrogen and progesterone have low concentrations. In this research, this phase was considered from the first day of bleeding to day 5 [17,23]. The assessment of phase I was conducted as soon as possible from the first day of bleeding, with the cutoff for this first assessment being day 5 of the menstrual cycle.

- -

- Phase II: Detected by a positive urinary ovulation kit (Luteinizing Hormone (LH) screening). It is characterized by a marked increase in estrogen, as well as progesterone (compared to phase I). This study considered this phase from a positive urinary ovulation kit until 48 h after detection [23].

- -

- -

- Menstrual cycle mapping: Women communicated with the research team on the first day of their menstruation, which was considered as day 1 of the cycle.

- -

- Urinary LH measurement: Participants performed the ovulation detection test from day 8 of the cycle until a positive result was observed on the urine strip (Ovulation test, Acofar, Madrid, Spain). It was requested that it should be carried out first thing in the morning, and an appointment was scheduled as soon as possible to carry out the tests. During the first visit, women in the natural MC group were instructed on the use of urinary LH detection strips. For those not obtaining a positive result, tests were repeated in the next cycle. A negative test result on two consecutive occasions led to the exclusion of the athlete from the study. The result was verified by photographic evidence [17,23].

- -

- Serum hormone analysis: Estrogen and progesterone levels were determined. In addition, LH and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) were also measured in each phase, in order to detect possible pathologies such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). To determine whether ovulation had occurred or not, a minimum limit of 16 nmol·L−1 of serum progesterone was stated [17,23], determined between 7 and 9 days after a positive ovulation was detected in the urine. Subsequently, based on the levels of progesterone obtained in the analysis, all those who showed serum levels of progesterone greater than 16 nmol·L−1 were included in the group of women with natural ovulatory cycles. A lower result was grounds for exclusion from the analysis [17,23].

2.2. Phases of the Contraceptive MC

2.2.1. Study Variables

- -

- Hormonal variables: progesterone (nmol·L−1), estrogen (pmol/L), FSH (mIU/mL), LH (mIU/mL), total testosterone (nmol/L), SHBG (nmol/L), urinary LH (only in natural cycle), progesterone/estrogen ratio (P/E ratio), and FAI.

- -

- Variables related to physical fitness:

- ○

- Cardiorespiratory fitness: O2max (mL·kg−1·min−1) (indirectly calculated using the Course Navette test formula, explained later) and total meters achieved in the Course Navette test (m).

- ○

- High-speed strength: squat jump 50% additional body weight (cm), squat jump (cm), counter movement jump (cm), Abalakov jump (cm), and drop jump from 40 cm (cm).

- ○

- Hand grip strength: dominant hand grip (kg).

- ○

- Flexibility: sit and reach test (cm).

- -

- Variables related to body composition: height, body mass (kg), total body water (L), body fat percentage (%), skeletal muscle mass (kg), BMI (kg·m−2).

- -

- Variables related to sensitivity and pain: sensory threshold (mA), first pain threshold (mA).

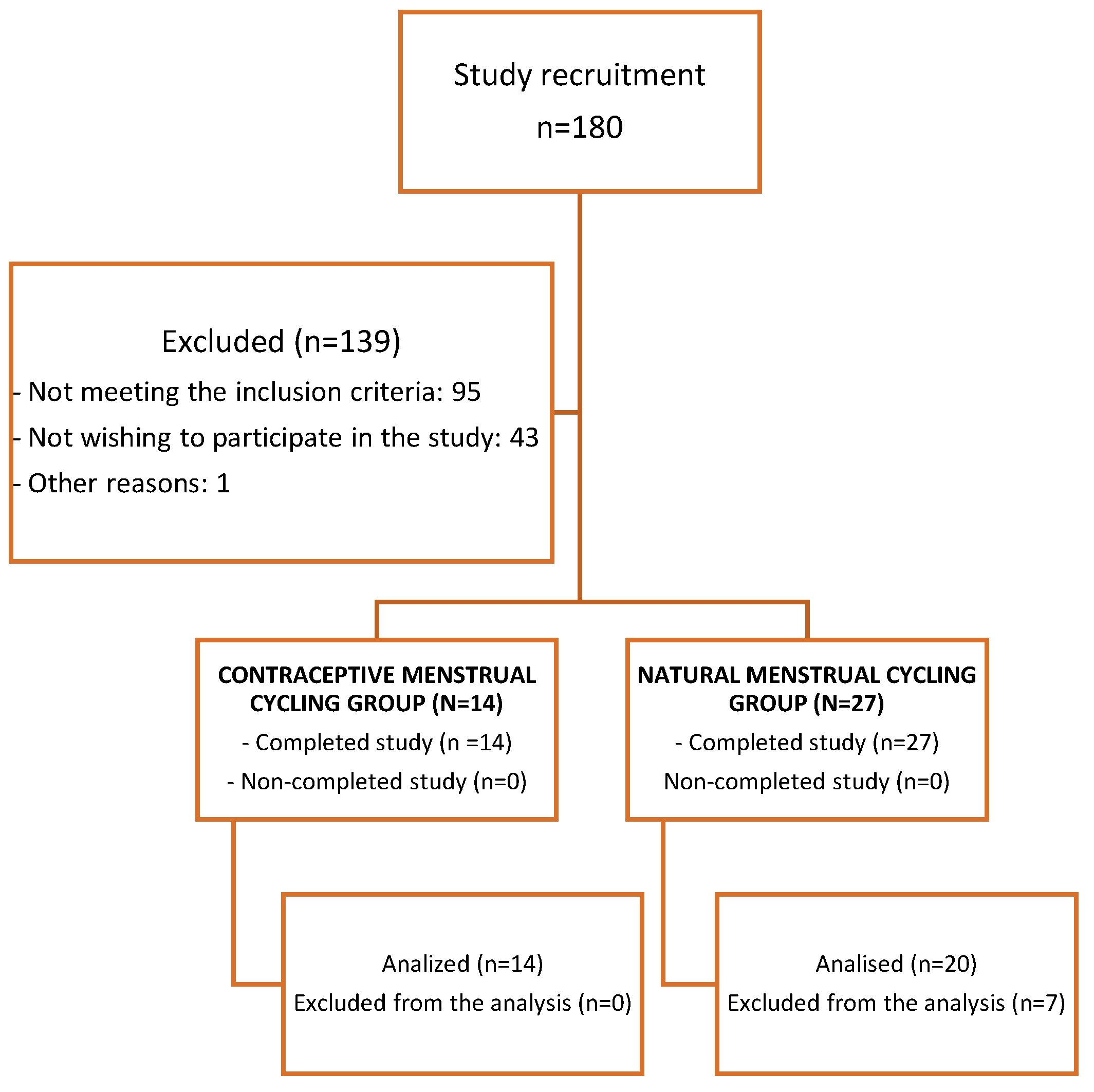

2.2.2. Participants

2.2.3. Test protocol

- I.

- Interview

- II.

- Bioimpedance

- III.

- Sensory and pain threshold

- IV.

- Blood test

- V.

- Warm-up and fitness level assessment tests:

- -

- Flexibility: sit and reach test

- -

- Hand grip strength: maximum grip dominant hand

- -

- High-speed strength: squat jump with 50% body weight, squat jump, countermovement jump, Abalakov jump, and drop jump from 40 cm

- -

- Cardiorespiratory fitness: Course Navette test

- (I)

- Interview

- (II)

- Bioimpedance

- (III)

- Sensory and first pain threshold test

- (IV)

- Blood test

- (V)

- Warm-up and fitness level assessment tests

- -

- The sit and reach test was used to measure flexibility [39].

- -

- Maximum grip dominant hand (hand grip) [40,41] was measured with a dynamometer (Takei TKK 5101, Tokyo, Japan). The athletes were instructed to stay in a relaxed position, and after a countdown of 3 s, they had to make the maximum possible force with their hand on the dynamometer, maintaining the maximum prehensile force for 5 s. Previously, the width of the dynamometer was adjusted to the comfort of each athlete. Jump battery [42]: squat jump with additional weight (50% body weight) [43], squat jump without additional weight [44], counter movement jump [44], Abalakov jump [43], drop jump from 40 cm with arm swing) [43,45,46]. The jump height was estimated by the flight time measured with a contact platform (Chronojump, Barcelona, Spain) [47]. Before the jumps, they were instructed on how to perform each of them. For squat jump with additional weight, the participant placed a bar over the shoulders with the corresponding weight.

- -

- Finally, the Course Navette test [48]. The test was stopped by the participant’s own fatigue or when for 2 consecutive times they failed to step on the line that marks the 20 m before the test sounds. The measurement of maximum oxygen consumption (O2max) was carried out. The measurement of maximum oxygen consumption (O2max) was indirectly determined using the Course Navette test, following the protocol developed by Luc Léger et al. [49]. The predicted O2max was calculated using the following formula: predicted O2max = −24.4 + 6 × X, where X1 represents the athlete’s maximal shuttle speed (km/h). Additionally, the distance covered by the athletes during the test was measured using the method described by Garcia and Secchi [50].

2.2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sex Hormones

3.2. Fitness Level and MC Phases

3.3. Body Composition

3.4. Sensory Threshold and Pain Threshold

Multiple Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Influence of Natural MC on Cardiorespiratory Fitness

4.2. Influence of Natural MC on High-Speed Strength, Hand Grip Strength, and Flexibility

4.3. Influence of Natural MC on the Pain and Sensory Thresholds

4.4. Influence of Contraceptive Menstrual Cycling Phases on the Level of Cardiorespiratory Fitness, High-Speed Strength, Hand Grip Strength, and Flexibility

4.5. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oosthuyse, T.; Bosch, A.N. The effect of the menstrual cycle on exercise metabolism: Implications for exercise performance in eumenorrhoeic women. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 207–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Strength & Conditioning Association. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning, 4th ed.; Haff, G.G., Triplett, N.T., Eds.; National Strength & Conditioning Association: Colorado Springs, Co, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Findlay, R.J.; MacRae, E.H.R.; Whyte, I.Y.; Easton, C.; Forrest, L.J. How the menstrual cycle and menstruation affect sporting performance: Experiences and perceptions of elite female rugby players. Br. J. Sports Med. 2020, 54, 1108–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott-Sale, K.J.; McNulty, K.L.; Ansdell, P.; Goodall, S.; Hicks, K.M.; Thomas, K.; Swinton, P.A.; Dolan, E. The Effects of Oral Contraceptives on Exercise Performance in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 1785–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNulty, K.L.; Elliott-Sale, K.J.; Dolan, E.; Swinton, P.A.; Ansdell, P.; Goodall, S.; Thomas, K.; Hicks, K.M. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Exercise Performance in Eumenorrheic Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2020, 50, 1813–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde, E. The Reconciliation of Sporting Life and Training of Top-Level Sportsmen and Women in Spain: A Quantitative Overview. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Sports Sciences, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Toledo, OH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ansdell, P.; Brownstein, C.G.; Škarabot, J.; Hicks, K.M.; Simoes, D.C.; Thomas, K.; Howatson, G.; Hunter, S.K.; Goodall, S. Menstrual cycle-associated modulations in neuromuscular function and fatigability of the knee extensors in eumenorrheic women. J. Appl. Physiol. 2019, 126, 1701–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, A.C. Sex Hormones, Exercise and Women, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; 315p. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmer, J.T.; Ivey, F.M.; Ryan, A.S.; Martel, G.F.; Hurlbut, D.E.; Metter, J.E.; Fozard, J.L.; Fleg, J.L.; Hurley, B.F. Effect of strength training on resting metabolic rate and physical activity: Age and gender comparisons. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julian, R.; Hecksteden, A.; Fullagar, H.H.K.; Meyer, T. The effects of menstrual cycle phase on physical performance in female soccer players. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, J.; Reilly, T. The effect of menstrual cycle on 2000-m rowing ergometry performance. Eur. J. Sport Sci. 2008, 8, 351–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazil, K.N.; Fatyh, K.; Guleda, B.; Murat, T.; Yakup, P.; Fulya, E. Some Performance Parameter Changes During Menstrual Cycle Periods of Athletes and Non-Athletes. Ovidius Univ. Ann. Ser. Phys. Educ. Sport/Sci. Mov. Health 2010, 10, 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Štefanovský, M.; Péterová, A.; Vanderka, M.; Lengvarský, L. Influence of selected phases of the menstrual cycle on performance in special judo fitness test and wingate test. Acta Gymnica 2016, 46, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.J.; Miller, B.E.; Loucks, A.B.; Luciano, A.A.; Pescatello, L.S.; Campbell, C.G.; Lasley, B.L. High frequency of luteal phase deficiency and anovulation in recreational women runners: Blunted elevation in follicle-stimulating hormone observed during luteal-follicular transition. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 4220–4232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Janse De Jonge, X.A.K. Effects of the menstrual cycle on exercise performance. Sports Med. 2003, 33, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaumberg, M.A.; Jenkins, D.G.; Janse de Jonge, X.A.K.; Emmerton, L.M.; Skinner, T.L. Three-step method for menstrual and oral contraceptive cycle verification. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 965–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jonge, X.J.; Thompson, B.; Han, A. Methodological Recommendations for Menstrual Cycle Research in Sports and Exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 2610–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermon, S.; Garnier, P.Y.; Hirschberg, A.L.; Robinson, N.; Giraud, S.; Nicoli, R.; Baume, N.; Saugy, M.; Fénichel, P.; Bruce, S.J.; et al. Serum androgen levels in elite female athletes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 99, 4328–4335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Crée, C. Sex steroid metabolism and menstrual irregularities in the exercising female. Sports Med. 1998, 25, 369–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaumberg, M.A.; Jenkins, D.G.; Janse De Jonge, X.A.K.; Emmerton, L.M.; Skinner, T.L. Oral contraceptive use dampens physiological adaptations to sprint interval training. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2017, 49, 717–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, M.; Bird, S. The physiology of the highly trained female endurance runner. Sports Med. 2000, 30, 281–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, M.F.; Harrison, M.L.; Lalande, S. Impact of Menstrual Blood Loss and Oral Contraceptive Use on Oxygen-carrying Capacity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2019, 52, 1414–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott-Sale, K.J.; Minahan, C.L.; de Jonge, X.A.J.; Ackerman, K.E.; Sipilä, S.; Constantini, N.W.; Lebrun, C.M.; Hackney, A.C. Methodological Considerations for Studies in Sport and Exercise Science with Women as Participants: A Working Guide for Standards of Practice for Research on Women. Sports Med. 2021, 51, 843–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebrun, C.M.; Joyce, S.M.; Constantini, N.W. Effects of Female Reproductive Hormones on Sports Performance. In Endocrinology of Physical Activity and Sport; Contemporary Endocrinology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 267–301. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-33376-8_16 (accessed on 18 July 2023).

- Kaunitz, A.M. Menstruation: Choosing whether…and when. Contraception 2000, 62, 277–284. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11239613/ (accessed on 28 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- Archer, D.F. Menstrual-cycle-related symptoms: A review of the rationale for continuous use of oral contraceptives. Contraception 2006, 74, 359–366. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17046376/ (accessed on 28 July 2023). [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.J.; Toombs, R.J.; Scheid, J.L.; O’Donnell, E.; West, S.L.; Williams, N.I. High prevalence of subtle and severe menstrual disturbances in exercising women: Confirmation using daily hormone measures. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, T. The Menstrual Cycle and Human Performance: An Overview. Biol. Rhythm. Res. 2010, 31, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spona, J.; Elstein, M.; Feichtinger, W.; Sullivan, H.; Lüdicke, F.; Müller, U.; Düsterberg, B. Shorter pill-free interval in combined oral contraceptives decreases follicular development. Contraception 1996, 54, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blode, H.; Kowal, K.; Roth, K.; Reif, S. Pharmacokinetics of drospirenone and ethinylestradiol in Caucasian and Japanese women. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2012, 17, 284–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endrikat, J.; Blode, H.; Gerlinger, C.; Rosenbaum, P.; Kuhnz, W. A pharmacokinetic study with a low-dose oral contraceptive containing 20 μg ethinylestradiol plus 100 μg levonorgestrel. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2002, 7, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sociedad Española de Ginecología. Combined Oral, Transdermal and Vaginal Hormonal Contraception; Sociedad Española de Ginecología: Madrid, Spain, 2006; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, A.K.; Stellingwerff, T.; Smith, E.S.; Martin, D.T.; Mujika, I.; Goosey-Tolfrey, V.L.; Sheppard, J.; Burke, L.M. Defining Training and Performance Caliber: A Participant Classification Framework. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, N.M.; Hills, A.P.; Hunter, G.R.; Weinsier, R.L.; Schutz, Y. Metabolic equivalent: One size does not fit all. J. Appl. Physiol. 2005, 99, 1112–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digitimer. Digitimer Operator’s Manual; Digitimer: Welwyn Garden City, UK, 2013; Available online: https://www.digitimer.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/DS8R-MAN_v2.1.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Current, D.C.; Voltage, H. Digitimer; Digitimer Ltd.: Welwyn Garden City, UK, 2014; p. 510. [Google Scholar]

- de Brito Barbosa, M.; de Oliveira Guirro, E.C.; Nunes, F.R. Evaluation of sensitivity, motor and pain thresholds across the menstrual cycle through mediumfrequency transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Clinics 2013, 68, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giamberardino, M.A.; Berkley, K.J.; Iezzi, S.; De Bigontina, P.; Vecchiet, L. Pain threshold variations in somatic wall tissues as a function of menstrual cycle, segmental site and tissue depth in non-dysmenorrheic women, dysmenorrheic women and men. Pain 1997, 71, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Miñarro, P.Á.; Vaquero-Cristóbal, R.; Muyor, J.M.; Espejo-Antúnez, L. Criterion-related validity of sit-and-reach test as a measure of hamstring extensibility in older women. Nutr. Hosp. 2015, 32, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nikolaidis, P.T.; Rosemann, T.; Knechtle, B. Force-velocity characteristics, muscle strength, and flexibility in female recreational marathon runners. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, J.R.; Artero, E.G.; Ortega, F.B.; Chillón, P.; Girela Rejón, M.J.; Mora, J.; Gutierrez, A.; Suni, J.; Sjöstrom, M.; Castillo, M.J. Alpha-fitness battery: Field test for the assessment of health-related physical fitness in children and adolescents. Nutr. Hosp. 2011, 26, 1210–1214. [Google Scholar]

- National Strength & Conditioning Association. High-speed strength with a jump battery. In Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning, 4th ed.; Haff, G.G., Triplett, N.T., Eds.; National Strength & Conditioning Association: Colorado Springs, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Centeno Prada, R.A. Reference Values for Jumps on a Dynamometric Platform in a Population of Andalusian Sportsmen and Women. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Pablo de Olavide, Sevilla, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- De Blas, X.; Padullés, J.M.; Del Amo, J.L.L.; Guerra-Balic, M. Creación y validación de Chronojump-Boscosystem: Un instrumento libre para la medición de saltos verticales. RICYDE Rev. Int. Cienc. Deporte 2012, 8, 334–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Blas, X. Free Software Tool for the Kinematic Study of Vertical Jumping: Time Measurement, Markerless Bending Angle Detection and Percentile Tables. Ph.D. Thesis, Chronojump-Boscosystem Project, Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Turner, A.; Comfort, P.; Harry, J.R.; McMahon, J.J.; Chavda, S.; Bishop, C. A Systematic Review of the Different Calculation Methods for Measuring Jump Height During the Countermovement and Drop Jump Tests. Sports Med. 2023, 53, 1055–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Blas Foix, X.; Padull, X. Manual de Chronojump. 2021, pp. 1–116. Available online: https://www.google.com.hk/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwj-tZPT-OKAAxWNVd4KHUnQCWwQFnoECBgQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fchronojump.org%2Fdocs%2Fchronojump_manual_en.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1cLpZ4dw3MNObhoYPlyjNr&opi=89978449 (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Léger, L.A.; Lambert, J. A maximal multistage 20-m shuttle run test to predict VO2 max. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1982, 49, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Léger, L.A.; Mercier, D.; Gadoury, C.; Lambert, J. The multistage 20 metre shuttle run test for aerobic fitness. J. Sports Sci. 1988, 6, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G.C.; Secchi, J.D. 20-metre test course navette with one-minute stages. An original idea that has been around for 30 years. Apunt. Sports Med. 2014, 49, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Dokumacı, B.; Hazır, T. Effects of the Menstrual Cycle on Running Economy: Oxygen Cost Versus Caloric Cost. Res. Q. Exerc. Sport 2019, 90, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrel, P.A.; Wilmor, J.H.; Coyl, E.F.; Billin, J.E.; Costil, D.L. Plasma lactate accumulation and distance running performance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1979, 25, 1091–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawilowsky, S.S. Very large and huge effect sizes. J. Mod. Appl. Stat. Methods 2009, 8, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. The Analysis of Variance and Covariance. In Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1988; pp. 273–407. [Google Scholar]

- Vaiksaar, S.; Jürimäe, J.; Mäestu, J.; Purge, P.; Kalytka, S.; Shakhlina, L.; Jürimäe, T. No Effect of Menstrual Cycle Phase and Oral Contraceptive Use on Endurance Performance in Rowers. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2011, 25, 1571–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba-Moreno, L.; Cupeiro, R.; Romero-Parra, N.; De Jonge, X.A.K.J.; Peinado, A.B. Cardiorespiratory Responses to Endurance Exercise Over the Menstrual Cycle and With Oral Contraceptive Use. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2022, 36, 392–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltgalvis, K.A.; Greising, S.M.; Warren, G.L.; Lowe, D.A. Estrogen regulates estrogen receptors and antioxidant gene expression in mouse skeletal muscle. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D.A.; Baltgalvis, K.A.; Greising, S.M. Mechanisms behind Estrogens’ Beneficial Effect on Muscle Strength in Females. Exerc. Sport Sci. Rev. 2011, 38, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isacco, L.; Boisseau, N. Sex Hormones and Substrate Metabolism During Endurance Exercise. In Sex Hormones, Exercise and Women; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- Vingren, J.L.; Kraemer, W.J.; Ratamess, N.A.; Anderson, J.M.; Volek, J.S.; Maresh, C.M. Testosterone physiology in resistance exercise and training: The up-stream regulatory elements. Sports Med. 2010, 40, 1037–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado-Boira, E.; Baliño, P.; Boldo-Roda, A.; Martínez-Navarro, I.; Hernando, B.; Recacha-Ponce, P.; Hernando, C.; Muriach, M. Influence of female sex hormones on ultra-running performance and post-race recovery: Role of testosterone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Navarro, I.; Montoya-Vieco, A.; Collado, E.; Hernando, B.; Hernando, C. Ultra Trail Performance is Differently Predicted by Endurance Variables in Men and Women. Int. J. Sports Med. 2022, 43, 600–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, B.M.; Drover, K.B.; Stellmaker, R.J.; Sculley, D.V.; Janse de Jonge, X.A.K. The effect of the menstrual cycle and oral contraceptive cycle on muscle performance and perceptual measures. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, T.V.; Dalgaard, L.B.; Sevdalis, V.; Bibby, B.M.; de Jonge, X.J.; Gravholt, C.H.; Hansen, M. Muscle Performance during the Menstrual Cycle Correlates with Psychological Well-Being, but Not Fluctuations in Sex Hormones. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2022, 54, 1678–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiling, E.; Bryant, A.L.; Petersen, W.; Murphy, A.; Hohmann, E. Effects of menstrual-cycle hormone fluctuations on musculotendinous stiffness and knee joint laxity. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2007, 15, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bell, D.R.; Blackburn, J.T.; Hackney, A.C.; Marshall, S.W.; Beutler, A.I.; Padua, D.A. Hamstring Stiffness and Knee Laxity Across the Menstrual Cycle in Females with ACL Reconstruction. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2011, 43, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa, F.; Micheli, M.L.; Pompignoli, M.; Cannataro, R.; Gulisano, M.; Toselli, S.; Greco, G.; Coratella, G. The Influence of Menstrual Cycle on Bioimpedance Vector Patterns, Performance, and Flexibility in Elite Soccer Players. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2022, 17, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sambanis, M.; Kofotolis, N.; Kalogeropoulou, E.; Noussios, G.; Sambanis, P.; Kalogeropoulos, J. A study of the effects on the ovarian cycle of athletic training in different sports. J. Sports Med. Phys. Fit. 2003, 43, 398–403. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Parra, N.; Alfaro-Magallanes, V.M.; Rael, B.; Cupeiro, R.; Rojo-Tirado, M.A.; Benito, P.J.; Peinado, A.B. Indirect markers of muscle damage throughout the menstrual cycle. Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform. 2021, 16, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackney, A.C.; Smith-Ryan, A.E.; Fink, J.E. Methodological Considerations in Exercise Endocrinology. In Endocrinology of Physical Activity and Sport; Humana Press Inc.: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 1–17. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-33376-8_1 (accessed on 18 July 2023).

| Measurement | Natural MC (n = 20) | Contraceptive MC (n = 14) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 26.55 ± 5.880 | 26.86 ± 5.187 | 0.769 |

| Height (cm) | 165.21 ± 6.529 | 162.11 ± 5.088 | 0.231 |

| BMI (kg·m−2) | 23.06 ± 2.419 | 22.79 ± 3.087 | 0.545 |

| Age at first menstruation (year) | 12.15 ± 1.137 | 12.62 ± 1.557 | 0.501 |

| Duration of cycles | 27.90 ± 2.732 | 27.23 ± 1.739 | 0.598 |

| Duration of bleedings | 4.41 ± 0.795 | 3.83 ± 0.937 | 0.166 |

| Years practicing sport | 13.75 ± 8.22 | 14.14 ± 8.55 | 0.890 |

| Measurement Natural Cycle | PHASE I | p Value/d de Cohen | PHASE II | p Value/d de Cohen | PHASE III | p Value/d de Cohen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone (nmol/L) | 1.98 ± 1.09 (1.47 to 2.49) b | 0.022/0.80 | 9.21 ± 8.84 (5.07 to 13.35) c | 0.005/1.66 | 33.89 ± 9.80 (29.30 to 38.48) a | 0.001/3.28 |

| Estrogen (pmol/L) | 140.39 ± 84.50 (100.84 to 179.94) b | 0.000/1.05 | 493.34 ± 326.31 (340.62 to 646.06) | 519.26 ± 192.54 (429.14 to 609.38) a | 0.001/2.05 | |

| P/E ratio | 20.94 ± 19.87 (26.84–9.59) b | 29.07 ± 29.52 (39.73–4.75) c | 0.000/1.01 | 72.20 ± 29.30 (94.79–50.64) a | 0.001/2.16 | |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 6.01 ± 1.69 (5.21 to 6.80) b | 5.88 ± 3.53 (4.22 to 7.54) c | 0.000/0.83 | 2.75 ± 0.90 (2.32 to 3.17) a | 0.001/1.79 | |

| LH (mIU/mL) | 4.07 ± 1.83 (3.21 to 4.92) b | 0.000/0.61 | 15.07 ± 18.10 (6.59 to 23.54) c | 0.000/0.62 | 3.80 ± 2.41 (2.67 to 4.93) | |

| Total testosterone (nmol/L) | 1.21 ± 0.37 (1.03 to 1.38) b | 0.02/0.54 | 1.38 ± 0.41 (1.18 to 1.57) c | 0.02/0.84 | 1.13 ± 0.24 (1.01 to 1.24) | |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 75.69 (63.41 to 87.96) | 81.13 (66.32 to 95.93) | 83.98 (68.12 to 99.84) | |||

| Free androgen index (nmol/L) | 1.68 ± 26.22 (1.45 to 1.91) | 1.92 ± 31.63 (1.49 to 2.35) c | 0.011/0.46 | 1.54 ± 33.88 (1.22 to 1.86) a | 0.027/0.30 |

| Measurement Contraceptive MC | Inactive HC Phase | Active HC Phase | p Value | d de Cohen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Progesterone (nmol/L) | 2.22 ± 0.95 (1.67 to 2.77) | 2.95 ± 1.78 (1.60 to 3.60)) | 0.470 | 0.28 |

| Estrogen (pmol/L) | 103.14 ± 130.53 (27.77 to 178.51) | 30.05 ± 58.29 (−3.60 to 63.71) | 0.016 | 0.49 |

| P/E ratio | 63.90 ± 79.03 (18.27 to 109.54) | 200.44 ± 211.18 (78.50 to 322.37) | 0.026 | 0.70 |

| FSH (mIU/mL) | 5.05 ± 3.42 (3.33 to 7.29) | 1.07 ± 1.27 (0.34 to 1.81) | 0.001 | 1.2 |

| LH (mIU/mL) | 2.72 ± 2.41 (1.33 to 4.12) | 0.59 ± 0.02 (0.06 to 1.12) | 0.003 | 0.8 |

| Total testosterone (nmol/L) | 1.34 ± 0.41 (1.10 to 1.58) | 1.01 ± 0.25 (0.86 to 1.16) | 0.003 | 1.09 |

| SHBG (nmol/L) | 217.91 ± 92.81 (164.32 to 271.50) | 361.59 ± 142.64 (279.23 to 443.95) | 0.002 | 1.51 |

| Free androgen index (nmol/L) | 0.84 ± 0.76 (0.39 to 1.28) | 0.36 ± 0.24 (0.22 to 0.50) | 0.005 | 0.60 |

| Measurement Natural Cycle | PHASE I | p Value/d de Cohen (I vs. II) | PHASE II | p Value/d de Cohen (II vs. III) | PHASE III | p Value/d de Cohen (I vs. III) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass (kg) | 63.23 ± 10.05 (58.52 to 67.94) c | 62.64 ± 9.66 (58.11 to 67.16) | 62.48 ± 9.74 (57.92 to 67.04) a | 0.006/0.60 | ||

| Total body water (L) | 36.50 ± 5.02 (34.15 to 38.84) | 36.39 ± 4.90 (34.09 to 38.68) | 36.42 ± 4.66 (34.23 to 38.60) | |||

| Body fat percent (%) | 20.61 ± 6.691 (17.48 to 23.74) c | 20.18 ± 6.603 (17.09 to 23.27) | 19.85 ± 6.583 (16.76 to 22.93) a | 0.011/0.54 | ||

| Skeletal muscle mass | 27.84 ± 4.06 (25.93 to 29.73) | 27.75 ± 3.9 (25.87 to 29.62) | 27.82 ± 3.86 (26.01 to 29.62) | |||

| BMI (kg·m−2) | 23.05 ± 2.41 (21.92 to 24.18) b,c | 0.003/1.15 | 22.84 ± 2.35 (21.73 to 23.94) a | 22.79 ± 2.37 (21.67 to 23.90) a | 0.040/0.68 | |

| Course Navette (m) | 1100 ± 332.96 (944 to 1255) b,c | 0.005/1.15 | 1207 ± 316.91 (1058 to 1355) a | 1176 ± 396.91 (990 to 1361) a | 0.034/0.40 | |

| O2max (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 41.75 ± 5.28 (39.27 to 44.22) b,c | 0.004/1.45 | 43.85 ± 5.13 (41.44 to 46.25) a | 43.25 ± 6.19 (40.35 to 46.14) a | 0.043/0.49 | |

| Hand grip dominant hand (Kg) | 32.15 ± 6.93 (28.90 to 35.40) | 32.87 ± 7.80 (29.22 to 36.52) | 33.51 ± 6.53 (30.45 to 36.56) | |||

| Sit and reach (cm) | 11.15 ± 7.41 (7.68 to 14.62) | 11.28 ± 7.38 (7.82 to 14.74) | 11.97 ± 6.70 (8.83 to 15.11) | |||

| SJ 50% additional body weight (cm) | 14.08 ± 3.74 (12.33 to 15.84) | 14.40 ± 3.76 (12.67 to 16.20) | 14.85 ± 4.04 (12.96 to 16.74) | |||

| SJ (cm) | 26.49 ± 5.19 (24.06 to 28.92) | 25.97 ± 5.52 (23.39 to 28.56) | 26.74 ± 5.91 (23.74 to 29.51) | |||

| CMJ (cm) | 27.80 ± 5.40 (25.27 to 30.33) | 27.38 ± 5.00 (27.38 to 29.73) | 28.58 ± 6.10 (25.72 to 31.44) | |||

| ABK jump (cm) | 30.23 ± 5.19 (29.28 to 34.63) b | 0.001/0.71 | 29.15 ± 5.45 (27.77 to 32.77) a | 30.21 ± 6.00 (28.47 to 34.87) | ||

| DJ 40 cm (cm) | 24.32 ± 6.25 (21.39 to 27.24) | 25.39 ± 6.42 (22.38 to 28.40) | 25.45 ± 7.72 (21.84 to 29.07) | |||

| Sensory threshold (mA) | 0.64 ± 0.22 (0.53 to 0.74) b | 0.017/0.50 | 0.76 ± 0.29 (0.62 to 0.89) a | 0.75 ± 0.29 (0.61 to 0.89) | ||

| First pain threshold (mA) | 1.34 ± 1.05 (0.85 to 1.83) b,c | 0.027/0.40 | 1.69 ± 1.60 (0.94 to 2.44) a | 1.59 ± 1.31 (0.97 to 2.20) a | 0.011/0.31 |

| Measurement Contraceptive Menstrual Cycling | Inactive HC Phase | Active HC Phase | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body mass (kg) | 59.75 ± 7.67 (55.32 to 64.18) | 59.02 ± 7.68 (54.58 to 63.45) | 0.027/0.87 |

| Total body water (L) | 33.49 ± 2.70 (31.93 to 35.05) | 33.56 ± 2.54 (32.08 to 35.02) | |

| Body fat percent (%) | 22.64 ± 7.88 (18.08 to 27.19) | 21.54 ± 7.96 (16.94 to 26.14) | 0.014/0.76 |

| Skeletal muscle mass | 25.34 ± 2.23 (24.04 to 26.62) | 25.39 ± 2.10 (24.17 to 26.60) | |

| BMI (kg·m−2) | 22.79 ± 3.08 (21.00 to 24.56) | 22.49 ± 3.04 (20.73 to 24.25) | 0.017/0.66 |

| Course Navette (m) | 1110.00 ± 305.81 (933 to 1285) | 1185.71 ± 307.58 (1008 to 1363) | 0.040/0.59 |

| O2max (mL·kg−1·min−1) | 42.02 ± 4.53 (39.41 to 44.64) | 42.60 ± 6.34 (38.93 to 46.26) | |

| Hand grip hand dominant (kg) | 27.82 ± 3.32 (25.89 to 29.74) | 29.31 ± 3.89 (27.06 to 31.56) | |

| Seat and reach (cm) | 10.95 ± 6.68 (7.09 to 14.81) | 11.51 ± 7.68 (7.07 to 15.95) | 0.041/0.22 |

| SJ WITH 50% additional body weight (cms) | 12.15 ± 5.84 (8.77 to 15.52) | 13.48 ± 5.85 (10.10 to 16.86) | 0.009/0.40 |

| SJ (cms) | 23.26 ± 6.81 (19.32 to 27.19) | 23.80 ± 7.29 (19.58 to 28.01) | |

| CMJ (cms) | 24.20 ± 7.10 (20.10 to 28.31) | 25.07 ± 7.83 (20.55 to 29.59) | |

| ABK jump (cms) | 27.71 ± 8.03 (23.07 to 32.35) | 28.52 ± 8.05 (23.88 to 33.17) | |

| DJ (cms) | 23.42 ± 9.87 (17.17 to 29.12) | 22.02 ± 8.77 (16.95 to 27.09) | |

| Sensory threshold (mA) | 0.57 ± 0.26 (0.42 to 0.73) | 0.62 ± 0.19 (0.51 to 0.73) | |

| First pain threshold (mA) | 1.43 ± 0.98 (0.86 to 2.00) | 1.67 ± 1.14 (1.01 to 2.33) |

| Model | R2 Adjusted | Standardized Coefficients Beta | Standard Error | F (p) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: O2max Covariates: First pain threshold | 0.319 | 0.595 | 4.3619 | 9.885 (0.006) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Recacha-Ponce, P.; Collado-Boira, E.; Suarez-Alcazar, P.; Montesinos-Ruiz, M.; Hernando-Domingo, C. Is It Necessary to Adapt Training According to the Menstrual Cycle? Influence of Contraception and Physical Fitness Variables. Life 2023, 13, 1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13081764

Recacha-Ponce P, Collado-Boira E, Suarez-Alcazar P, Montesinos-Ruiz M, Hernando-Domingo C. Is It Necessary to Adapt Training According to the Menstrual Cycle? Influence of Contraception and Physical Fitness Variables. Life. 2023; 13(8):1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13081764

Chicago/Turabian StyleRecacha-Ponce, Paula, Eladio Collado-Boira, Pilar Suarez-Alcazar, Macarena Montesinos-Ruiz, and Carlos Hernando-Domingo. 2023. "Is It Necessary to Adapt Training According to the Menstrual Cycle? Influence of Contraception and Physical Fitness Variables" Life 13, no. 8: 1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13081764

APA StyleRecacha-Ponce, P., Collado-Boira, E., Suarez-Alcazar, P., Montesinos-Ruiz, M., & Hernando-Domingo, C. (2023). Is It Necessary to Adapt Training According to the Menstrual Cycle? Influence of Contraception and Physical Fitness Variables. Life, 13(8), 1764. https://doi.org/10.3390/life13081764