The Impact of Cannabidiol Treatment on Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Criteria

2.3.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.3.2. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Study Identification

2.5. Data Extraction

3. Results

3.1. Search Output and Flow

3.2. Outcomes

| Author(s) and Year of Publication | Sample Size | Sex | Age Range | Cause of Anxiety | Concomitant Anxiolytic Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zuardi et al., 2017 [21] | 60 | M/W | 18–35 | Public speech | _____ |

| Hundal et al., 2018 [22] | 32 | M/W | 18–50 | Paranoid thoughts | _____ |

| Linares et al., 2019 [16] | 57 | M | ____ | Public speech | _____ |

| Hurd et al., 2019 [23] | 42 | M/W | 21–65 | Abstinence of heroin use | _____ |

| Appiah-Kusi et al., 2020 [24] | 58 | M/W | ____ | Social stress—speech | _____ |

| Faria et al., 2020 [25] | 24 | M/W | ____ | Public speech of volunteers with Parkinson’s disease | _____ |

| Meneses-Gaya et al., 2021 [17] | 31 | M | 18+ | Abstinence of crack cocaine use | Psychotherapy and benzodiazepine |

| Bloomfield et al., 2022 [26] | 24 | M/W | 18–70 | Stress | _____ |

| Hutten et al., 2022 [19] | 26 | M/W | _____ | Abstinence of illicit drugs and alcohol | 1 group received THC and CBD |

| Bolsoni et al., 2022 a [27] | 33 | M/W | 18–60 | PTSD | _____ |

| Bolsoni et al., 2022 b [28] | 33 | M/W | 18–60 | PTSD | _____ |

| Kwee et al., 2022 [18] | 80 | W | 18–65 | Social anxiety | _____ |

| Mongeau-Pérusse et al., 2022 [20] | 78 | M/W | 18–65 | Cocaine use | Diphenhydramine and/or trazodone was provided for insomnia but not within 24 h before the cue-induced craving session |

| Stanley et al., 2022 [29] | 32 | M/W | 18–55 | Test anxiety | ______ |

| Gournay et al., 2023 [30] | 63 | M/W | 18–55 | High trait worriers | _____ |

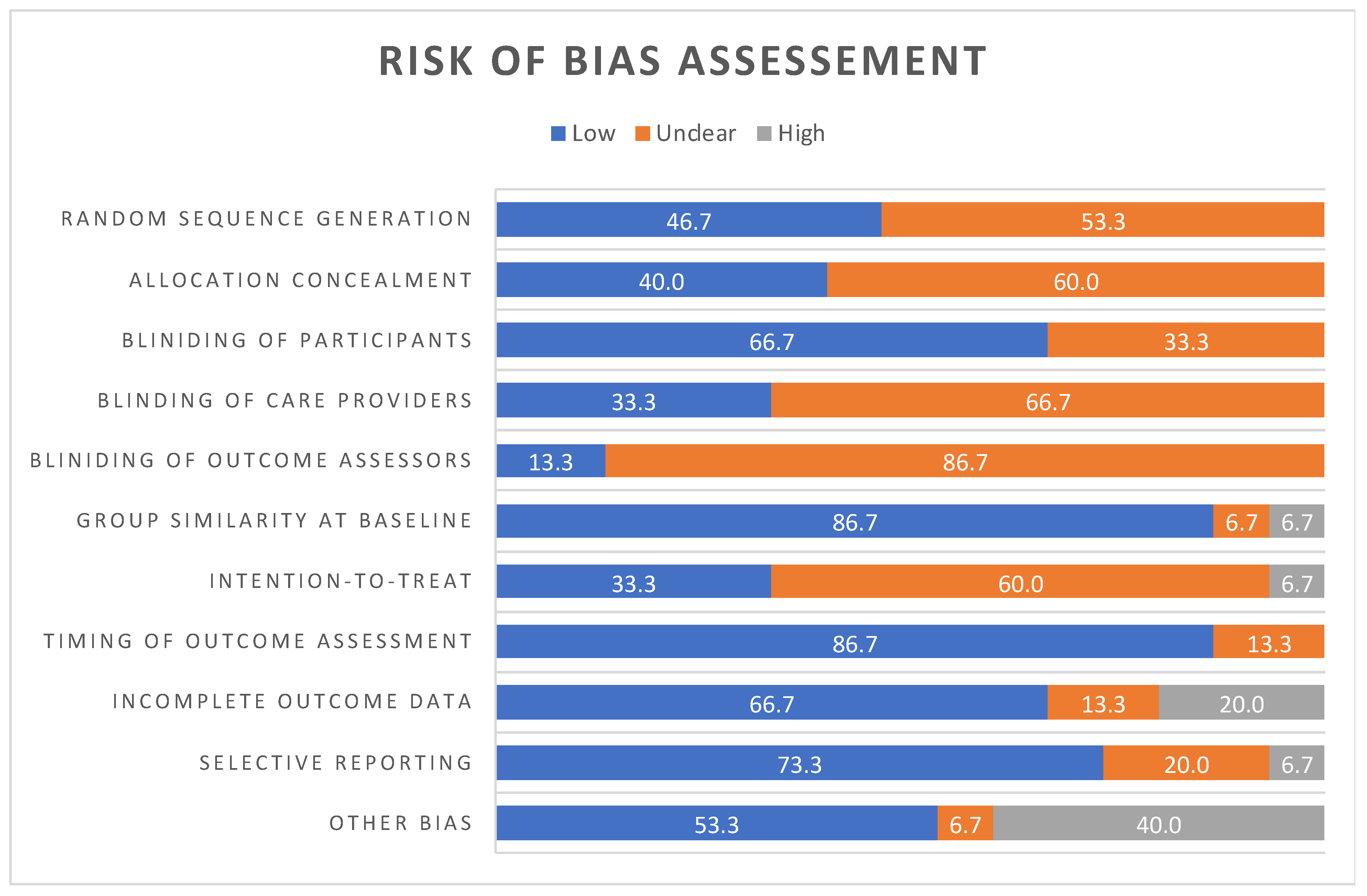

3.3. Quality Appraisal—Assessment of Risk of Bias

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, S.A.; Ross, S.A.; Slade, D.; Radwan, M.M.; Khan, I.A.; ElSohly, M.A. Minor oxygenated cannabinoids from high potency Cannabis sativa L. Phytochemistry 2015, 117, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, E.M.; Parker, L.A. Constituents of Cannabis Sativa. In Cannabinoids and Neuropsychiatric Disorders; Murillo-Rodriguez, E., Pandi-Perumal, S., Monti, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, V.N.; Menezes, A.R.; Deschutter, A.; Lavie, C.J. The Cardiovascular Effects of Marijuana: Are the Potential Adverse Effects Worth the High? Mo. Med. 2019, 116, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Viana, M.D.B.; Aquino, P.E.A.D.; Estadella, D.; Ribeiro, D.A.; Viana, G.S.D.B. Cannabis sativa and Cannabidiol: A Therapeutic Strategy for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases? Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids 2022, 5, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.; Hunt, M.; Clark, J. Structure of Cannabidiol, a Product Isolated from the Marihuana Extract of Minnesota Wild Hemp. I. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1940, 62, 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechoulam, R.; Shvo, Y. Hashish-I The Structure of Cannabidiol. Tetrahedron 1963, 19, 2073–2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechoulam, R.; Parker, L.A.; Gallily, R. Cannabidiol: An Overview of Some Pharmacological Aspects. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2002, 42, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devinsky, O.; Cross, J.H.; Laux, L.; Marsh, E.; Miller, I.; Nabbout, R.; Scheffer, I.E.; Thiele, E.A.; Wright, S. Trial of Cannabidiol for Drug-Resistant Seizures in the Dravet Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2011–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, R.F.; Wilkinson, D.J.; England, T.J.; O’Sullivan, S.E. The Pharmacological Effects of Plant-Derived versus Synthetic Cannabidiol in Human Cell Lines. Med. Cannabis Cannabinoids 2021, 4, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, B.; Lee, J.K.; Kim, J.; Kang, E.K.; Han, S.Y.; Lee, H.Y.; Choi, I.S. Synthetic Strategies for (−)-Cannabidiol Its Structural Analogs. Chem. Asian J. 2019, 14, 3749–3762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, G.N.; Nastase, A.S.; Aukema, R.J.; Hill, M.N. Endocannabinoids, cannabinoids and the regulation of anxiety. Neuropharmacology 2021, 195, 108626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, S.B.; Singewald, N. Novel pharmacological targets in drug development for the treatment of anxiety and anxiety-related disorders. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 204, 107402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Santos, C.M.C.; Pimenta, C.A.M.; Nobre, M.R.C. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savovic, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linares, I.M.; Zuardi, A.W.; Pereira, L.C.; Queiroz, R.H.; Mechoulam, R.; Guimarães, F.S.; Crippa, J.A. Cannabidiol presents an inverted U-shaped dose-response curve in a simulated public speaking test. Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 2019, 41, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meneses-Gaya, C.D.; Crippa, J.A.; Hallak, J.E.; Miguel, A.Q.; Laranjeira, R.; Bressan, R.A.; Zuardi, A.W.; Lacerda, A.L. Cannabidiol for the treatment of crack-cocaine craving: An exploratory double-blind study. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2021, 43, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwee, C.M.; Baas, J.M.; van der Flier, F.E.; Groenink, L.; Duits, P.; Eikelenboom, M.; Moerbeek, M.; Batelaan, N.M.; van Balkom, A.J.; Cath, D.C. Cannabidiol enhancement of exposure therapy in treatment refractory patients with social anxiety disorder and panic disorder with agoraphobia: A randomised controlled trial. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 59, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutten, N.R.; Arkell, T.R.; Vinckenbosch, F.; Schepers, J.; Kevin, R.C.; Theunissen, E.L.; Kuypers, K.P.C.; McGregor, I.S.; Ramaekers, J.G. Cannabis containing equivalent concentrations of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) induces less state anxiety than THC-dominant cannabis. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 3731–3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mongeau-Pérusse, V.; Rizkallah, E.; Morissette, F.; Brissette, S.; Bruneau, J.; Dubreucq, S.; Gazil, G.; Trépanier, A.; Jutras-Aswad, D. Cannabidiol Effect on Anxiety Symptoms and Stress Response in Individuals With Cocaine Use Disorder: Exploratory Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Addict. Med. 2022, 16, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuardi, A.W.; Rodrigues, N.P.; Silva, A.L.; Bernardo, S.A.; Hallak, J.E.; Guimarães, F.S.; Crippa, J.A. Inverted U-shaped dose-response curve of the anxiolytic effect of cannabidiol during public speaking in real life. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 247580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundal, H.; Lister, R.; Evans, N.; Antley, A.; Englund, A.; Murray, R.M.; Freeman, D.; Morrison, P.D. The effects of cannabidiol on persecutory ideation and anxiety in a high trait paranoid group. J. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 32, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurd, Y.L.; Spriggs, S.; Alishayev, J.; Winkel, G.; Gurgov, K.; Kudrich, C.; Oprescu, A.M.; Salsitz, E. Cannabidiol for the reduction of cue-induced craving and anxiety in drug-abstinent individuals with heroin use disorder: A double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2019, 176, 911–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appiah-Kusi, E.; Petros, N.; Wilson, R.; Colizzi, M.; Bossong, M.G.; Valmaggia, L.; Mondelli, V.; McGuire, P.; Bhattacharyya, S. Effects of short-term cannabidiol treatment on response to social stress in subjects at clinical high risk of developing psychosis. Psychopharmacology 2020, 237, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Faria, S.M.; de Morais Fabrício, D.; Tumas, V.; Castro, P.C.; Ponti, M.A.; Hallak, J.E.; Zuardi, A.W.; Crippa, J.A.S.; Chagas, M.H.N. Effects of acute cannabidiol administration on anxiety and tremors induced by a Simulated Public Speaking Test in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J. Psychopharmacol. 2020, 34, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, M.A.; Yamamori, Y.; Hindocha, C.; Jones, A.P.; Yim, J.L.; Walker, H.R.; Statton, B.; Wall, M.B.; Lees, R.H.; Howes, O.D.; et al. The acute effects of cannabidiol on emotional processing and anxiety: A neurocognitive imaging study. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 1539–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsoni, L.M.; Crippa, J.A.S.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Guimarães, F.S.; Zuardi, A.W. Effects of cannabidiol on symptoms induced by the recall of traumatic events in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychopharmacology 2022, 239, 1499–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolsoni, L.M.; Crippa, J.A.S.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Guimaraes, F.S.; Zuardi, A.W. The anxiolytic effect of cannabidiol depends on the nature of the trauma when patients with post-traumatic stress disorder recall their trigger event. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2022, 44, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanley, T.B.; Ferretti, M.L.; Bonn-Miller, M.O.; Irons, J.G. A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Test of the Effects of Cannabidiol on Experiences of Test Anxiety Among College Students. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2022, 8, 1090–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gournay, L.R.; Ferretti, M.L.; Bilsky, S.; Vance, E.; Nguyen, A.M.; Mann, E.; Williams, P.; Leen-Feldner, E.W. The effects of cannabidiol on worry and anxiety among high trait worriers: A double-blind, randomized placebo controlled trial. Psychopharmacology 2023, 240, 2147–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, F.S.; Chiaretti, T.M.; Graeff, F.G.; Zuardi, A.W. Antianxiety effect of cannabidiol in the elevated plus-maze. Psychopharmacology 1990, 100, 558–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galaj, E.; Bi, G.H.; Yang, H.J.; Xi, Z.X. Cannabidiol attenuates the rewarding effects of cocaine in rats by CB2, 5-HT1A and TRPV1 receptor mechanisms. Neuropharmacology 2020, 167, 107740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griebel, G.; Holmes, A. 50 years of hurdles and hope in anxiolytic drug discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2013, 12, 667–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwee, C.M.; van Gerven, J.M.; Bongaerts, F.L.; Cath, D.C.; Jacobs, G.; Baas, J.M.; Groenink, L. Cannabidiol in clinical and preclinical anxiety research. A systematic review into concentration–effect relations using the IB-de-risk tool. J. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 36, 1299–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huestis, M.A.; Solimini, R.; Pichini, S.; Pacifici, R.; Carlier, J.; Busardò, F.P. Cannabidiol Adverse Effects and Toxicity. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2019, 17, 974–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, M.; Devine, J. Assessment of patient-reported symptoms of anxiety. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 16, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mchorney, C.A.; Tarlov, A.R. Individual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: Are available health status surveys adequate? Qual. Life Res. 1995, 4, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, O.B.; Becker, J.; Bjorner, J.B.; Fliege, H.; Klapp, B.F.; Rose, M. Development and evaluation of a computer adaptive test for ‘Anxiety’ (Anxiety-CAT). Qual. Life Res. 2007, 16, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbons, R.D.; Weiss, D.J.; Pilkonis, P.A.; Frank, E.; Moore, T.; Kim, J.B.; Kupfer, D.J. Development of the CAT-ANX: A computerized adaptive test for anxiety. Am. J. Psychiatry 2014, 171, 187–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s) and Year of Publication | Groups and CBD Dose | Anxiety Measurement Methods | CBD Effects on Anxiety | CBD Side Effects | Study Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zuardi et al., 2017 [21] | - CBD 100 mg - CBD 300 mg - CBD 900 mg - CLON 1 mg - Placebo | - STAI - VAMS - Blood pressure - Heart rate | CBD 300 mg significantly relieved anxiety post public speech in comparison to placebo but did not reduce the blood pressure as much as CLON. | No side effects were mentioned | - small sample size; - did not have the results with other moderate doses of CBD (400 or 600 mg) |

| Hundal et al., 2018 [22] | - CBD 600 mg - Placebo | - BAI; - Blood pressure - Heart rate | No beneficial effects of CBD, and apparently, it increased the anxiety induced by paranoid thoughts. | CBD-treated group adverse events were tiredness/sedation, lightheaded/dizziness, nausea, abdominal discomfort, and increased appetite/hunger | - absence of plasma monitoring of CBD concentrations; - small sample size - single CBD dose |

| Linares et al., 2019 [16] | - CBD 150 mg - CBD 300 mg - CBD 600 mg - Placebo | - VAMS - Blood pressure | CBD 300 mg decreased anxiety during the speech in comparison with placebo. | No side effects were mentioned | - effects of CBD on subjective reports of anxiety and not physiological effects, - study was made only with men |

| Hurd et al., 2019 [23] | - CBD 400 mg - CBD 800 mg - Placebo | -VAS-A | CBD 400 mg and 800 mg reduced anxiety in heroin-abstinent volunteers. | No side effects were detected | - craving and anxiety outcomes were subjective self-reported measures, which may have provided unreliability or bias; - small sample size |

| Appiah-Kusi et al., 2020 [24] | - CBD 600 mg - Placebo | - STAI-S | CBD did not show any significant improvement on public speech—induced anxiety of people with high risk of psychosis. | No side effects were mentioned | - modest sample size; - stress caused by venepuncture to collect venous blood sampling; - they could not control other factors that could impact cortisol levels |

| Faria et al., 2020 [25] | - CBD 300 mg - Placebo | - VAMS - SSPS - Blood pressure - HR | CBD attenuated the anxiety induced by public speech on volunteers with Parkinson’s disease. | No side effects were detected | - small sample size; - time of CBD administration and the anxiety induction model should have been longer; - the anxiolytic effects observed cannot be generalized directly to any symptom of anxiety that may occur in daily living, since anxiety was induced experimentally in this study |

| Meneses-Gaya et al., 2021 [17] | - CBD 300 mg - Placebo | - BAI | CBD did not have any effect on anxiety induced by crack cocaine abstinence compared to placebo group. | - Sleepiness and increased sleep duration; nausea and headache | - symptoms tend to be less severe in hospitalized patients; - CBD dose is relatively low; - one single dose of CBD; - interference of other treatment outcomes once these patients were hospitalized more often; - sample may not represent the general socioclinical profile of crack cocaine users in general |

| Bloomfield et al., 2022 [26] | - CBD 600 mg - Placebo | - VAS-A - BAI - HR - Blood pressure | CBD did not have any effects on any measures relating to anxiety. | No side effects were mentioned | - the oral route of CBD administration was slow and associated with variable bioavailability; - relatively long fasting time and did not use an oil buffer, which may have led to insufficient absorption of CBD; - stimuli employed across tasks were inconsistent; - the mental arithmetic task was novel in the context of CBD research, whereas previous studies have employed public speaking |

| Hutten et al., 2022 [19] | - THC 13.75 mg - CBD 13.75 mg -THC/CBD 13.75 mg each - Placebo | - STAI—trait - VAS-A - EST | CBD, by itself, did not significantly change anxiety ratings on any of the anxiety measures induced by illicit drugs and alcohol abstinence. CBD relieved THC-induced anxiety completely when baseline anxiety was low, partly reduced THC-induced anxiety when baseline anxiety was medium and did not counteract THC-induced anxiety when baseline anxiety was high. CBD only counteracted THC-induced anxiety when trait anxiety was low. | No side effects were mentioned | - baseline state of anxiety was measured only by VAS and not by STAI and EST; -single dose of THC and CBD |

| Bolsoni et al., 2022 a [27] | - CBD 300 mg - Placebo | - IDATE - VAMS | CBD failed to attenuate increases in anxiety, alertness, and discomfort induced by the trauma recall; however, measures of cognitive impairment were significantly lower after recall in patients who received CBD compared to placebo. | No side effects were mentioned | - measurements were not subjected to correction for multiple comparisons; - presence of comorbidities as a variable in group matching was not included, which led to a greater concentration of participants with comorbidities in one of the groups (CBD) and hampered the interpretation of results. |

| Bolsoni et al., 2022 b [28] | - CBD 300 mg - Placebo | - VAMS - Blood pressure - Heart rate | In nonsexual trauma, CBD attenuated the increased anxiety and cognitive impairment of recall. However, it failed to do so when the event was sexual in nature. | No side effects were mentioned | - the mean patient age and time since the traumatic event were significantly lower among those with sexual trauma than nonsexual trauma, which could have influenced the nonattenuation of anxiety in the sexual trauma subsample; - the analysis was not corrected for multiple comparisons; - small sample size |

| Kwee et al., 2022 [18] | - CBD 300 mg - Placebo | - BAI - FQ - LSAS | CBD did not have any effect on anxiety induced by agoraphobia. | - Dizziness; drowsiness; tiredness; feeling of a strong blood flow | - suboptimal dose; - single dose of CBD, timing of administration and form of administration could impact the results |

| Mongeau-Pérusse et al., 2022 [20] | - Daily doses: CBD 800 mg - Placebo | - BAI - VAS-A - Levels of cortisol | No evidence for long-term administration of 800 mg CBD to be more efficacious than placebo for modulating anxiety symptoms and cortisol levels in individuals with cocaine use disorder. | No side effects were mentioned | - exclusion of individuals with other substances disorders limited the findings; - small sample size; - high attrition rate; - use of cocaine during the test may have masked the effects of cannabidiol during the weeks of its administration |

| Stanley et al., 2022 [29] | - CBD 150 mg - CBD 300 mg - CBD 600 mg - Placebo | - WTAS - VAS-A - VAMS - STAI-state - SSS-8 | A single dose of CBD in different doses did not impact on anxiety triggered by test anxiety in college students, and a higher dose seemed to increase the anxiety symptoms. | No side effects were mentioned | - sample was not diverse; - CBD 300 mg showed anxiolytic effects on anxiety triggered by the speech test, but not on anxiety triggered by test anxiety; - test anxiety needed to be validated; - experimental manipulations were sensitive to inducing changes in TA specifically rather than anxiety symptoms broadly |

| Gournay et al., 2023 [30] | - Repeated doses: CBD 50 e 300 mg -Placebo | - DASS-A | Repeated 300 mg CBD administration for 2 weeks, but not an acute 300 mg dose, reduced anxiety symptoms compared to placebo. | - Somnolence; dry mouth; lightheadedness; nausea; headache; increased appetite | - differences in anxiety symptoms between groups at the baseline; - the current study exclusively relied on self-report indicators, leaving findings open to confounds related to affect and memory bias; - the modifications to the BMWS instructional set obfuscated the interpretation of acute effects |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Coelho, C.d.F.; Vieira, R.P.; Araújo-Junior, O.S.; Lopes-Martins, P.S.L.; dos Santos, L.G.; Dias, L.D.; Filho, A.S.d.S.; Leonardo, P.S.; Silva, S.D.e.; Lopes-Martins, R.A.B. The Impact of Cannabidiol Treatment on Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Life 2024, 14, 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14111373

Coelho CdF, Vieira RP, Araújo-Junior OS, Lopes-Martins PSL, dos Santos LG, Dias LD, Filho ASdS, Leonardo PS, Silva SDe, Lopes-Martins RAB. The Impact of Cannabidiol Treatment on Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Life. 2024; 14(11):1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14111373

Chicago/Turabian StyleCoelho, Carly de Faria, Rodolfo P. Vieira, Osvaldo Soares Araújo-Junior, Pedro Sardinha Leonardo Lopes-Martins, Larissa Gomes dos Santos, Lucas Danilo Dias, Alberto Souza de Sá Filho, Patrícia Sardinha Leonardo, Sandro Dutra e Silva, and Rodrigo Alvaro Brandão Lopes-Martins. 2024. "The Impact of Cannabidiol Treatment on Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials" Life 14, no. 11: 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14111373

APA StyleCoelho, C. d. F., Vieira, R. P., Araújo-Junior, O. S., Lopes-Martins, P. S. L., dos Santos, L. G., Dias, L. D., Filho, A. S. d. S., Leonardo, P. S., Silva, S. D. e., & Lopes-Martins, R. A. B. (2024). The Impact of Cannabidiol Treatment on Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Life, 14(11), 1373. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14111373