Emergency-Driven Multiple Simultaneous Invasive Procedures in Haemophilia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

- -

- assess the type of haemophilia, comorbidities, age at the time of the intervention, type of emergency, type of intervention, and quantity of blood loss and transfusion;

- -

- consider three main principles: costs (including treatment with coagulation factor products and hospital stay), early complications (such as infection, bleeding, and thrombotic events), and late complications (including infection, onset of inhibitors, and thrombosis), as well as outcomes (aseptic loosening and need for revision).

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mannucci, P.M. Hemophilia treatment innovation: 50 years of progress and more to come. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2023, 21, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermans, C.; Gruel, Y.; Frenzel, L.; Krumb, E. How to translate and implement the current science of gene therapy into haemophilia care? Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2023, 14, 20406207221145627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Washington Medical Commission, Guidance Document, Overlapping and Simultaneous Elective Surgeries, WMC.wa.gov. Available online: https://wmc.wa.gov/sites/default/files/public/Overlapping%20and%20Simultaneous%20Elective%20Surgeries%20-%20Revised%208%2026%2022.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS), Overlapping, Simultaneous and Concurrent Surgery. Available online: https://www.surgeons.org/-/media/Project/RACS/surgeons-org/files/position-papers/2017-10-25_pos_fes-pst-039_overlapping_simultaneous_and_concurrent_surgery.pdf?rev=be3d6916f5024becb1e1928652e634b4&hash=09ED0D65F4594CB36EAAE3E168D115A7 (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Bakeer, N.; Saied, W.; Gavrilovski, A.; Bailey, C. Haemophilic arthropathy: Diagnosis, management, and aging patient considerations. Haemophilia 2024, 30 (Suppl. S3), 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schramm, W.; Gringeri, A.; Ljung, R.; Berger, K.; Crispin, A.; Bullinger, M.; Giangrande, P.L.; Von Mackensen, S.; Mantovani, L.G.; Nemes, L.; et al. ESCHQOL Study Group. Haemophilia care in Europe: The ESCHQoL study. Haemophilia 2012, 18, 729–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Merchán, E.C. The role of orthopaedic surgery in haemophilia: Current rationale, indications and results. EFORT Open Rev. 2019, 4, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hardaker, W.T.; Ogden, W.S., Jr.; Musgrave, R.E.; Goldner, J.L. Simultaneus and staged bilateral total knee arthroplasrty. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 1978, 60, 247–250. [Google Scholar]

- Osma Rueda, J.L.; Oliveros Vargas, A.; Sosa, C.D. Supracondylar femoral osteotomy and knee joint replacement during the same surgical procedure in a type A haemophiliac patient with knee flexion deformity and ankylosis. Knee 2017, 24, 477–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, A.; Antoniou, J.; Brin, Y.S.; Huk, O.L.; Zukor, D.J.; Bergeron, S.G. Simultaneous Bilateral Versus Unilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Comparison of 30-Day Readmission Rates and Major Complications. J. Arthroplast. 2016, 31, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Lv, Z.; Li, X.; Qin, X.; Fan, W. Mortality and morbidity associated with simultaneous bilateral or staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty: A metaanalysis. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2011, 131, 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Yoon, J.Y.; Nam, C.H.; Kim, T.K.; Jung, K.A.; Lee, D.W. Cerebral fat embolism syndrome after simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty: A case series. J. Arthroplast. 2012, 27, 409–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, N.; Chien, T.; Hussain, F.; Bookwala, A.; Simunovic, N.; Shetty, V.; Bhandari, M. Simultaneous versus staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty. HSS J. 2013, 9, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trojani, C.; Bugnas, B.; Blay, M.; Carles, M.; Boileau, P. Bilateral total knee arthroplasty in a one-stage surgical procedure. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2012, 98, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheth, D.S.; Cafri, G.; Paxton, E.W.; Namba, R.S. Bilateral simultaneous vs staged total knee arthroplasty: A comparison of complications and mortality. J. Arthroplast. 2016, 31 (Suppl. S9), 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagsby, D.; Pierson, J.L. Functional outcomes of simultaneous bilateral versus unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2015, 38, e43–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, A.C.; Chao, E.; Yang, C.M.; Wen, H.C.; Ma, H.L.; Lu, T.C. Costs of staged versus simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty: A population-based study of the Taiwanese National Health Insurance Database. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2014, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odum, S.M.; Troyer, J.L.; Kelly, M.P.; Dedini, R.D.; Bozic, K.J. A cost-utility analysis comparing cost-effectiveness of simultaneous and staged bilateral total knee arthroplasty. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2013, 95, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thès, A.; Molina, V.; Lambert, T. Simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty in severe hemophilia: A retrospective cost-effectiveness analysis. Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2015, 101, 147–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, S.M.J.; Haghpanah, B.; Ebrahiminasab, M.M.; Baghdadi, T.; Hantooshzadeh, R.; Toogeh, G. Simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty in patients with haemophilia: A safe and cost-effective procedure? Haemophilia 2016, 22, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shashikant, A.; Rajesh, P.; Aditi, J.; Kannan, S. Bilateral, Simultaneous Total Knee Replacement (TKR) Surgery for Hemophilia a with Eloctate (Extended Half-Life Product)—A Feasible and Cost Effective Approach. Blood 2018, 132 (Suppl. S1), 4684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Xiao, K.; Gao, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Ren, Y.; Weng, X. Comparison of 90-Day Complication Rates and Cost Between Single and Multiple Joint Procedures for End-Stage Arthropathy in Patients with Hemophilia. JBJS Open Access 2018, 3, e0026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- de Kleijn, P.; Sluiter, D.; Vogely, H.C.; Lindeman, E.; Fischer, K. Long-term outcome of multiple joint procedures in haemophilia. Haemophilia 2014, 20, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, B.; Zhai, J.; Bian, Y.; Qiu, G.; Weng, X. Simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty in patients with end-stage hemophilic arthropathy: A mean follow-up of 6 years. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, B.J.; Mao, Q.; Li, J.; Lv, S.J.; Tong, P.; Jin, H.T. Bilateral synchronous total hip arthroplasty for end-stage arthropathy in haemophilia A patients: A retrospective study. Medicine 2022, 101, e29667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Caviglia, H.; Candela, M.; Galatro, G.; Neme, D.; Moretti, N.; Bianco, R.P. Elective orthopaedic surgery for haemophilia patients with inhibitors: Single centre experience of 40 procedures and review of the literature. Haemophilia 2011, 17, 910–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ji, L.; Xu, C. A simultaneous minimally invasive approach to treat a patient with coronary artery disease and metastatic lung cancer. Wideochir. Inne Tech. Maloinwazyjne 2016, 11, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarov, R.; Osminin, S.; Ismailbaev, A.; Ivashov, I.; Agakina, Y.; Schekoturov, I. The First Case of Simultaneous Surgical Procedure for Mitral Valve Disease and Esophageal Cancer. Case Rep. Oncol. 2021, 14, 1665–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandy, K.; Gangadhara, B.; Reddy, S.; Chakravarthy, M.; Jawali, V.; Thimmaiah, S.G.; Khan, A.; Nayak, S.P. Simultaneous surgical management of malignancy and coronary heart disease. Indian J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2024, 40, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Merchan, E.C. Simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty in haemophilia: Is it recommended? Expert. Rev. Hematol. 2017, 10, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Merchan, E.C. What’s New in Orthopedic Surgery for People with Hemophilia. Arch. Bone Jt. Surg. 2018, 6, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fu, D.; Li, G.; Chen, K.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, X.; Cai, Z. Comparison of clinical outcome between simultaneous-bilateral and staged-bilateral total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review of retrospective studies. J. Arthroplast. 2013, 28, 1141–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayam, L.; Theaker, J.; Shah, S.V. Knee Arthropathy and Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty Ratio in Hemophilia A Patients. Sak. Med. J. 2019, 9, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Intervention | One-Stage | Simultaneous | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orthopedic | 188 | 2 | 190 |

| Non-orthopedic | |||

| 29 | 29 | |

| 7 | 7 | |

| 6 | 6 | |

| 4 | 4 | |

| 2 | 2 | |

| 3 | 3 | |

| 6 | 6 | |

| 1 | 1 | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | 13 | |

| Total | 259 | 3 | 262 |

| Characteristics | Comorbidities | Emergency | Intervention | Blood Loss | Total Estimated Costs | Complications | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

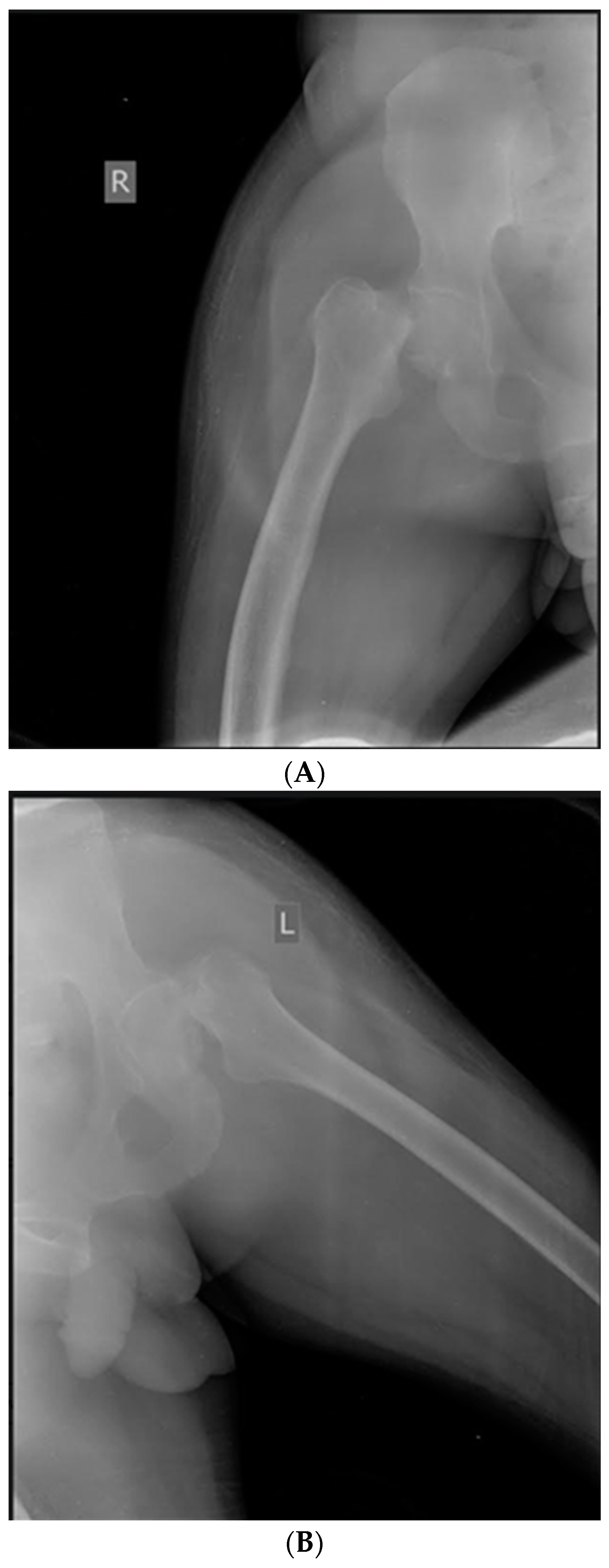

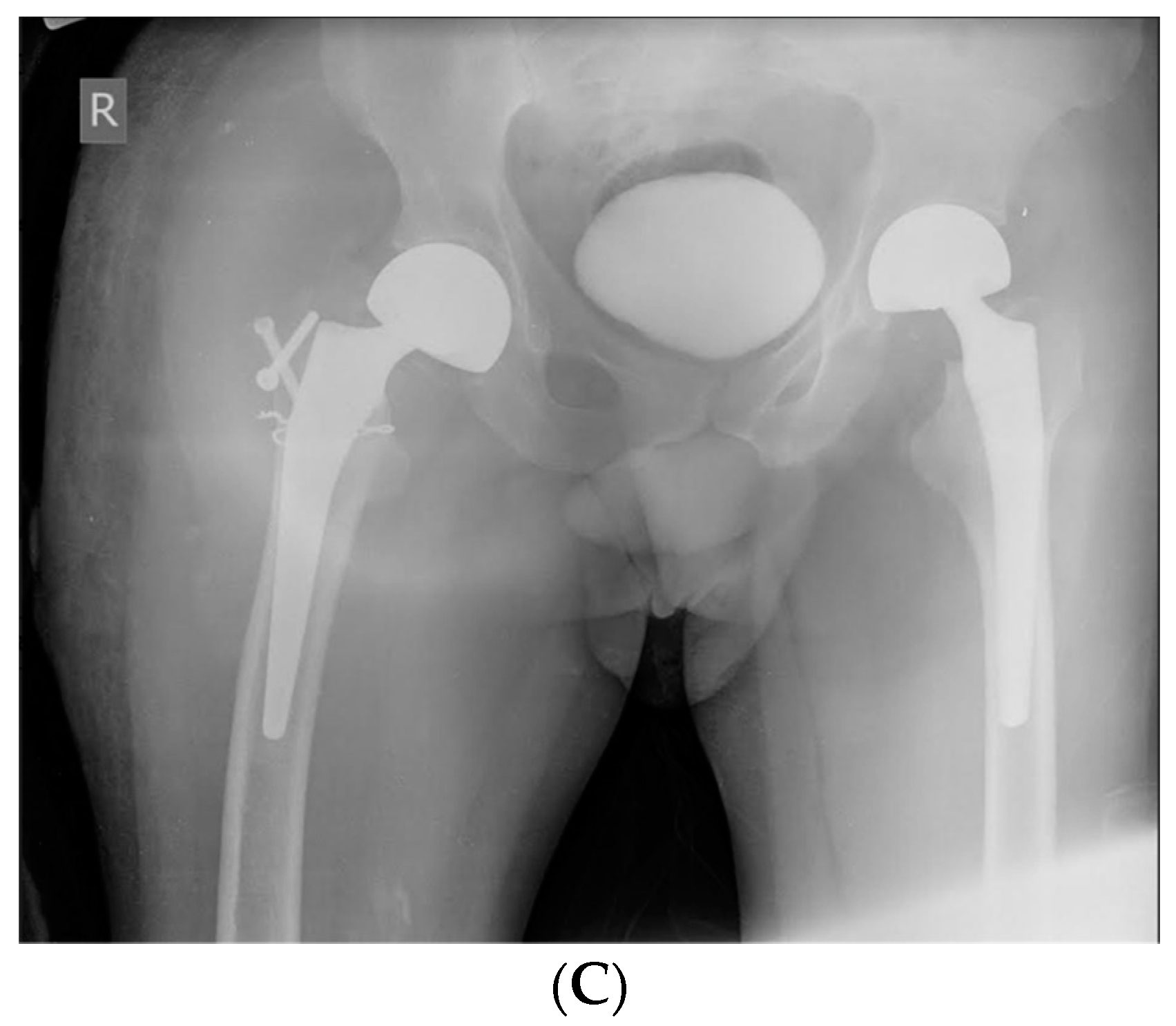

| Case 1. 50-years-old male, with severe haemophilia B | -known and treated for epilepsy -chronic viral hepatitis C | -trauma-related bilateral femoral neck fracture | -bilateral simultaneous hip arthroplasty -the right hip joint is complicated with pertrochanteric fracture, needing an additional osteosynthesis with screws | ~1200 mL (3 units pRBCs) | ~86,856.05 € (91.75% for recombinant FIX concentrate) | No | Good, discharged after 30 days |

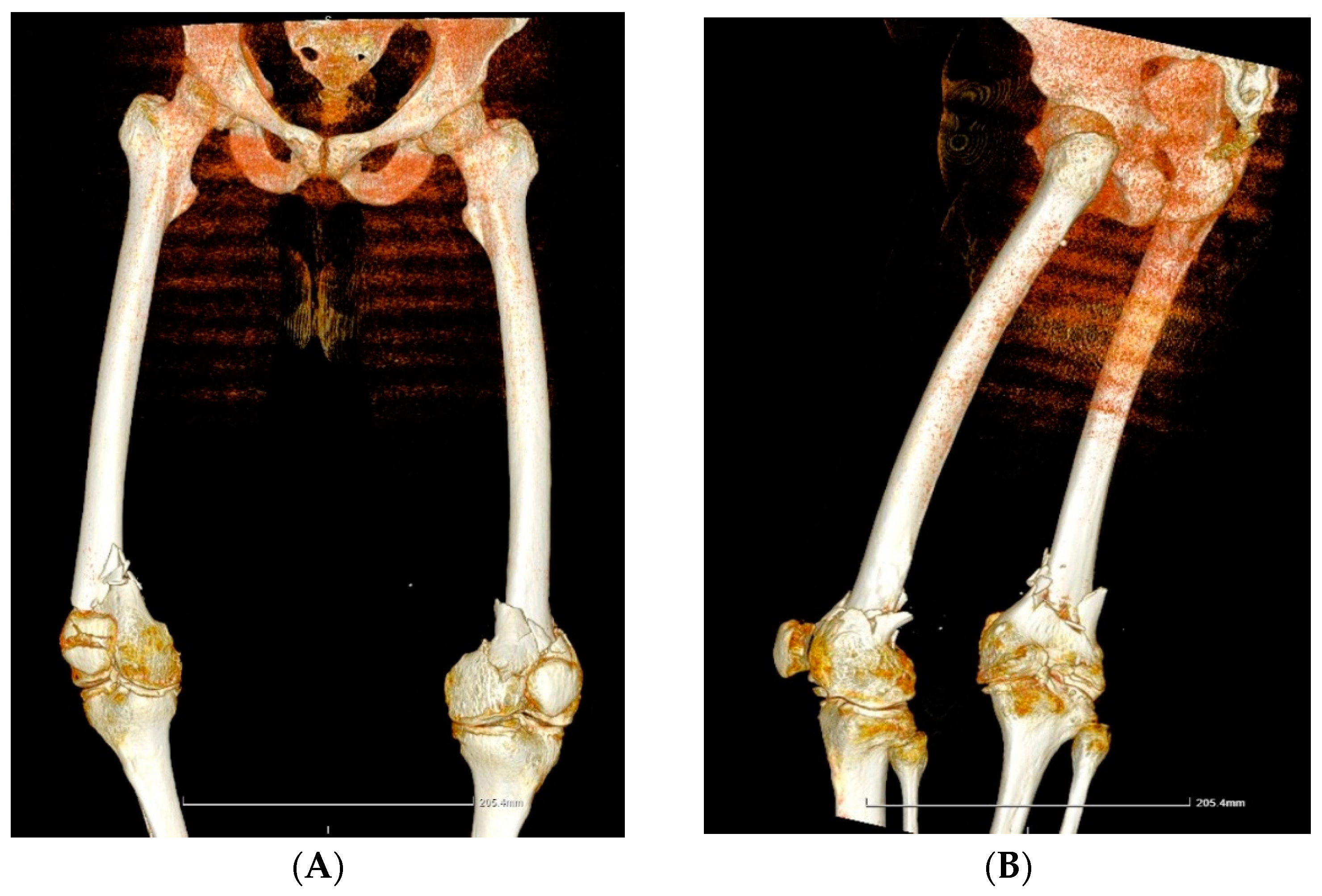

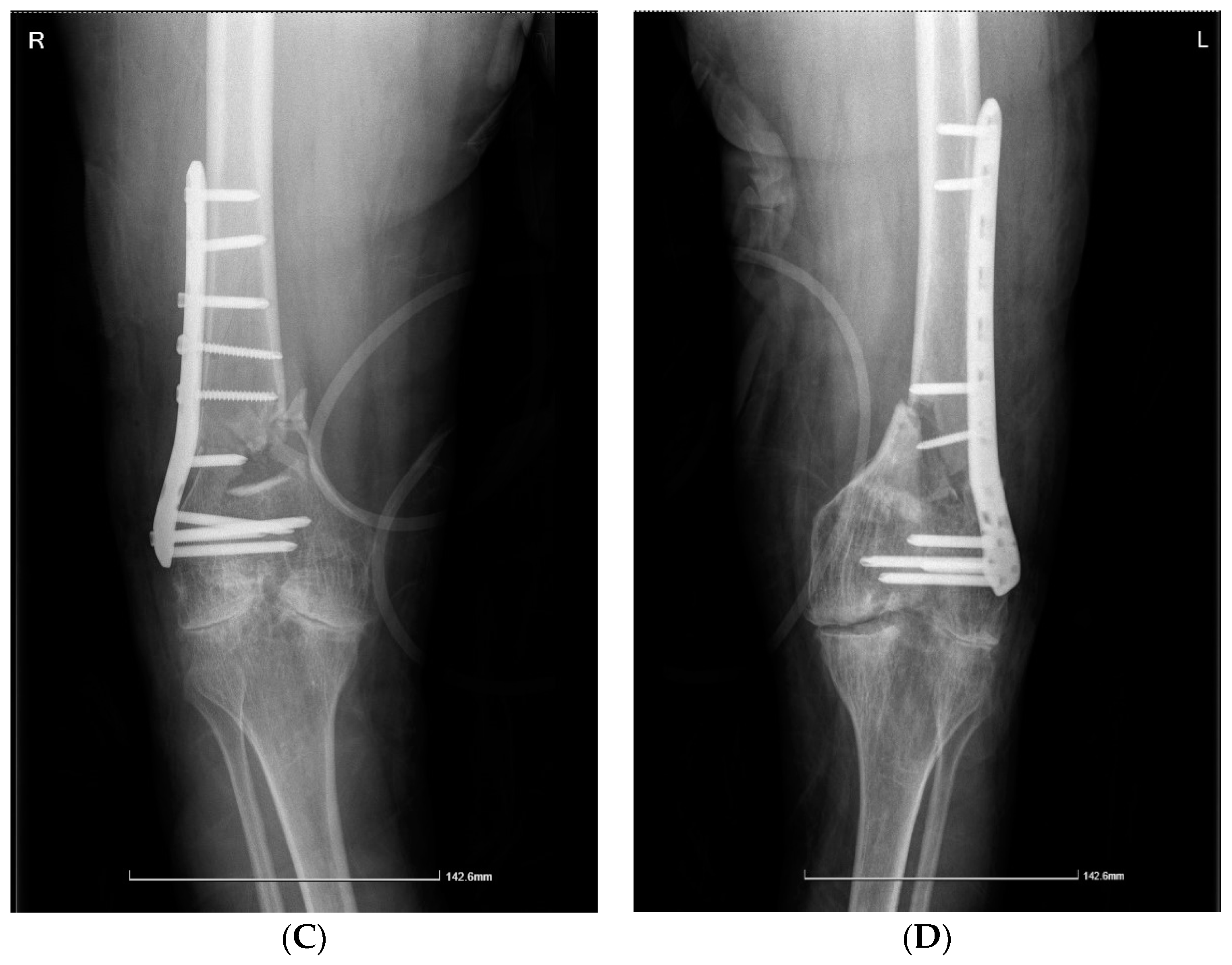

| Case 2. 39-years-old male, with severe haemophilia A | -chronic viral hepatitis C | -post-traumatic bilateral femoral supracondylar fracture | -open reduction and osteosynthesis with plates and screws of the pelvic limb bilaterally | ~1300 mL (4 units pRBCs) | ~40,217.44 € (71.78% for EHL FVIII concentrate) | No | Good, discharge after 21 days |

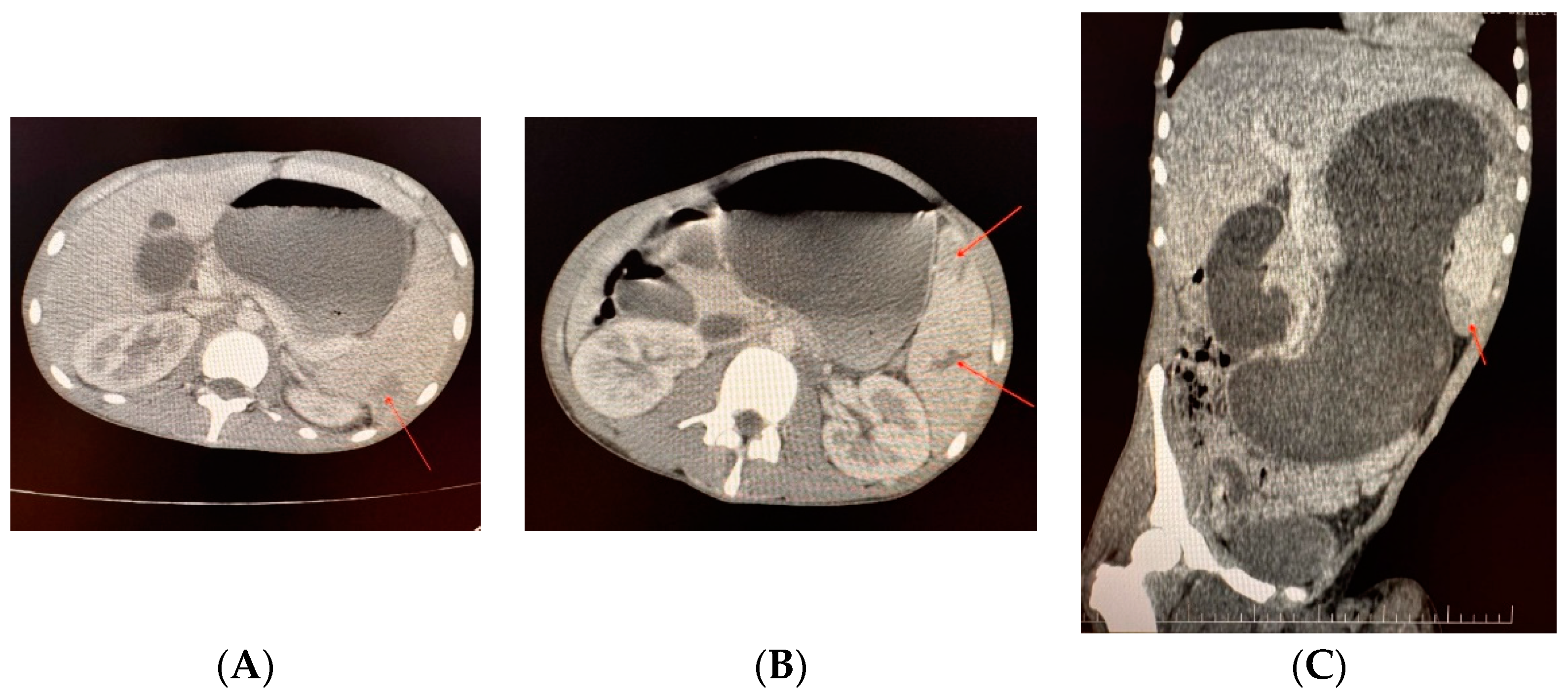

| Case 3. 19-years-old male with severe haemophilia B | -chronic viral hepatitis C | -intense pain in the left hypochondrium, epigastrium, and mesogastrium -massive abdominal distension -splenomegaly with two hematomas in the mid-body and inferior pole, and suspected rupture in two times -left elbow and calf hematoma with cutaneous necrosis | -splenectomy -evacuation of the left elbow hematoma -elbow skin necrosis excision (defect 6/4 cm) followed by partial covering, with skin collected from the anterolateral and 1/3 middle side of the left thigh -evacuation of the left calf hematoma, approximately 400 mL sero-hematic liquid + clots (fibrillar rupture of internal gemini muscles) | ~1500 mL (4 units pRBCs) | ~32,763.70 € (92.80% for plasma-derived FIX concentrate) | -acute functional gastric dilatation due to pyloric spasm, with evacuation of 2.5 L of gastric stasis liquid -hematoma at the inferior pole of the surgical wound. | Good, discharge after 27 days |

| Factor VIII/IX Plasma Level Required (%) | Duration of Treatment (Days) | |

|---|---|---|

| Pre- and intra-operatively | 80–100% | |

| Postoperatively | 60–80% | 1–7 |

| 30–50% | 7–14 | |

| 15–30% | Rehabilitation period |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ursu, C.E.; Șerban, M.; Pătrașcu, J.M.; Coriu, D.; Pătrașcu, J.M., Jr.; Ioniță, I.; Trăilă, A.; Tomuleasa, C.; Săvescu, D.; Brânză, M.; et al. Emergency-Driven Multiple Simultaneous Invasive Procedures in Haemophilia. Life 2024, 14, 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14091172

Ursu CE, Șerban M, Pătrașcu JM, Coriu D, Pătrașcu JM Jr., Ioniță I, Trăilă A, Tomuleasa C, Săvescu D, Brânză M, et al. Emergency-Driven Multiple Simultaneous Invasive Procedures in Haemophilia. Life. 2024; 14(9):1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14091172

Chicago/Turabian StyleUrsu, Cristina Emilia, Margit Șerban, Jenel Marian Pătrașcu, Daniel Coriu, Jenel Marian Pătrașcu, Jr., Ioana Ioniță, Adina Trăilă, Ciprian Tomuleasa, Delia Săvescu, Melen Brânză, and et al. 2024. "Emergency-Driven Multiple Simultaneous Invasive Procedures in Haemophilia" Life 14, no. 9: 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14091172

APA StyleUrsu, C. E., Șerban, M., Pătrașcu, J. M., Coriu, D., Pătrașcu, J. M., Jr., Ioniță, I., Trăilă, A., Tomuleasa, C., Săvescu, D., Brânză, M., Ivan, C., & Arghirescu, T. S. (2024). Emergency-Driven Multiple Simultaneous Invasive Procedures in Haemophilia. Life, 14(9), 1172. https://doi.org/10.3390/life14091172