MRI Staging in Locally Advanced Vulvar Cancer: From Anatomy to Clinico-Radiological Findings. A Multidisciplinary VulCan Team Point of View

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Anatomy and MRI Findings

3.1. Mons Pubis, Labia Majora and Minora

3.2. Clitoris

3.3. Vestibule

3.4. Vascularization

3.5. Lymphatic Drainage

4. MRI Protocol

5. MR Imaging Impact Stage by Stage

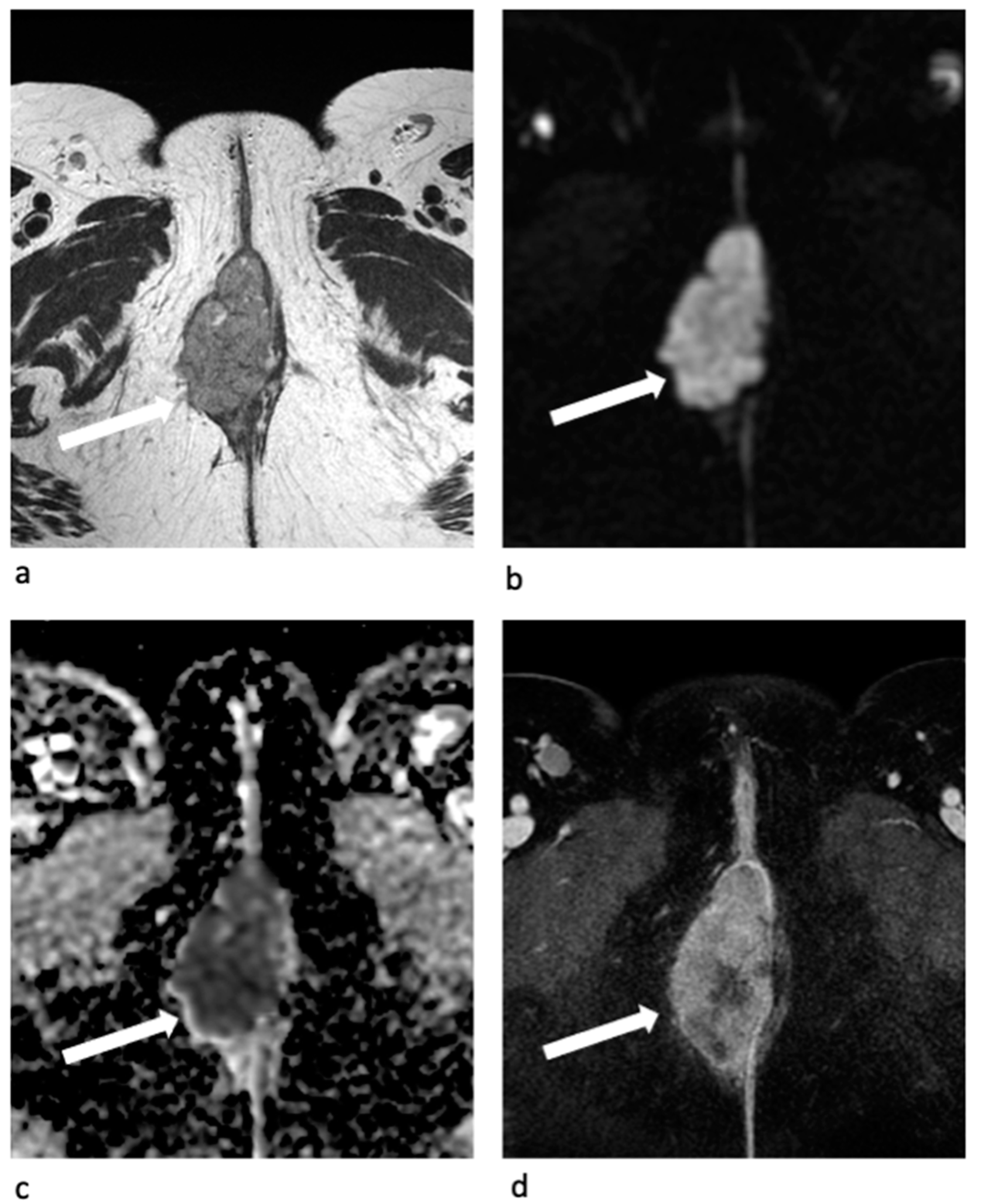

- Stage II

- Stage III

- Stage IVA

- Stage IVB

6. MRI Focused Report

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network Vulvar Cancer (Squamous Cell Carcinoma) (Version 03.2021). Available online: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/vulvar.pdf (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Miccò, M.; Sala, E.; Lakhman, Y.; Hricak, H.; Vargas, H.A. Imaging Features of Uncommon Gynecologic Cancers. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2015, 205, 1346–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Garganese, G.; Inzani, F.; Mantovani, G.; Santoro, A.; Valente, M.; Babini, G.; Petruzzellis, G.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Gentileschi, S.; Bove, S.; et al. The Vulvar Immunohistochemical Panel (VIP) Project: Molecular Profiles of Vulvar Paget’s Disease. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 2211–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, G.; Fagotti, A.; Franchi, M.; Scambia, G.; Garganese, G. Reviewing Vulvar Paget’s Disease Molecular Bases. Looking Forward to Personalized Target Therapies: A Matter of CHANGE. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2019, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shetty, A.S.; Menias, C.O. MR Imaging of Vulvar and Vaginal Cancer. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. N. Am. 2017, 25, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacker, N.F.; Eifel, P.J.; van der Velden, J. Cancer of the Vulva. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obs. 2015, 131 (Suppl. 2), S76–S83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, K.W.; Shinagare, A.B.; Krajewski, K.M.; Howard, S.A.; Jagannathan, J.P.; Zukotynski, K.; Ramaiya, N.H. Update on Imaging of Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2013, 201, W147–W157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favato, G.; Baio, G.; Capone, A.; Marcellusi, A.; Costa, S.; Garganese, G.; Picardo, M.; Drummond, M.; Jonsson, B.; Scambia, G.; et al. Novel Health Economic Evaluation of a Vaccination Strategy to Prevent HPV-Related Diseases: The BEST Study. Med. Care 2012, 50, 1076–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragomeni, S.M.; Inzani, F.; Fagotti, A.; Della Corte, L.; Gentileschi, S.; Tagliaferri, L.; Zannoni, G.F.; Scambia, G.; Garganese, G. Molecular Pathways in Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Implications for Target Therapeutic Strategies. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 146, 1647–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, S.A.; Moskovic, E.C. Imaging in Vulval Cancer. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obs. Gynaecol. 2003, 17, 543–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, O.; Sousa, F.A.E.; Cunha, T.M.; Nikolić, M.B.; Otero-García, M.M.; Gui, B.; Nougaret, S.; Leonhardt, H. ESUR Female Pelvic Imaging Working Group Vulvar Cancer Staging: Guidelines of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR). Insights Imaging 2021, 12, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrado, M.A.; Horta, M.; Cunha, T.M. State of the Art in Vulvar Cancer Imaging. Radiol. Bras. 2019, 52, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Suneja, G.; Viswanathan, A. Gynecologic Malignancies. Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 34, 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, C.; Kirschner, K.; Truong, M.; Balachandran, A.; Devine, C.; Bhosale, P. Multimodality Imaging of Vulvar Cancer: Staging, Therapeutic Response, and Complications. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2013, 200, 1387–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosseinzadeh, K.; Heller, M.T.; Houshmand, G. Imaging of the Female Perineum in Adults. Radiographics 2012, 32, E129–E168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collarino, A.; Garganese, G.; Valdés Olmos, R.A.; Stefanelli, A.; Perotti, G.; Mirk, P.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Ieria, F.P.; Scambia, G.; Giordano, A.; et al. Evaluation of Dual-Timepoint 18F-FDG PET/CT Imaging for Lymph Node Staging in Vulvar Cancer. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 1913–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Collarino, A.; Garganese, G.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Pereira Arias-Bouda, L.M.; Ieria, F.P.; Boellaard, R.; Rufini, V.; de Geus-Oei, L.-F.; Scambia, G.; Valdés Olmos, R.A.; et al. Radiomics in Vulvar Cancer: First Clinical Experience Using 18F-FDG PET/CT Images. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 60, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rufini, V.; Garganese, G.; Ieria, F.P.; Pasciuto, T.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Gui, B.; Florit, A.; Inzani, F.; Zannoni, G.F.; Scambia, G.; et al. Diagnostic Performance of Preoperative [18F]FDG-PET/CT for Lymph Node Staging in Vulvar Cancer: A Large Single-Centre Study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 3303–3314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataoka, M.Y.; Sala, E.; Baldwin, P.; Reinhold, C.; Farhadi, A.; Hudolin, T.; Hricak, H. The Accuracy of Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Staging of Vulvar Cancer: A Retrospective Multi-Centre Study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 117, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadducci, A.; Aletti, G.D. Locally Advanced Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva: A Challenging Question for Gynecologic Oncologists. Gynecol. Oncol. 2020, 158, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfani, F.; Garganese, G.; Fagotti, A.; Lorusso, D.; Gagliardi, M.L.; Rossi, M.; Salgarello, M.; Scambia, G. Advanced Vulvar Carcinoma: Is It Worth Operating? A Perioperative Management Protocol for Radical and Reconstructive Surgery. Gynecol. Oncol. 2006, 103, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancellotta, V.; Macchia, G.; Garganese, G.; Fionda, B.; Fragomeni, S.M.; D’Aviero, A.; Casà, C.; Gui, B.; Gentileschi, S.; Corrado, G.; et al. The Role of Brachytherapy (Interventional Radiotherapy) for Primary and/or Recurrent Vulvar Cancer: A Gemelli Vul.Can Multidisciplinary Team Systematic Review. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2021, 23, 1611–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagliaferri, L.; Garganese, G.; D’Aviero, A.; Lancellotta, V.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Fionda, B.; Casà, C.; Gui, B.; Perotti, G.; Gentileschi, S.; et al. Multidisciplinary Personalized Approach in the Management of Vulvar Cancer—The Vul.Can Team Experience. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2020, 30, 932–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garganese, G.; Tagliaferri, L.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Lancellotta, V.; Colloca, G.; Corrado, G.; Gentileschi, S.; Macchia, G.; Tamburrini, E.; Gambacorta, M.A.; et al. Personalizing Vulvar Cancer Workflow in COVID-19 Era: A Proposal from Vul.Can MDT. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 146, 2535–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, L.; Tsui, B.Q.; Bahrami, S.; Masamed, R.; Memarzadeh, S.; Raman, S.S.; Patel, M.K. Gynecologic Tumor Board: A Radiologist’s Guide to Vulvar and Vaginal Malignancies. Abdom. Radiol. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakhman, Y.; Vargas, H.A.; Reinhold, C.; Akin, E.A.; Bhosale, P.R.; Huang, C.; Kang, S.K.; Khanna, N.; Kilcoyne, A.; Nicola, R.; et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Staging and Follow-up of Vulvar Cancer. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2021, 18, S212–S228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.D.; Resnick, E.L.; Mhuircheartaigh, J.N.; Mortele, K.J. MR Imaging of the Female Perineum: Clitoris, Labia, and Introitus. Magn. Reson. Imaging Clin. N. Am. 2017, 25, 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, C.D.; Brocker, K.A.; Eichbaum, M.; Sohn, C.; Arnegger, F.U.; Kauczor, H.-U.; Hallscheidt, P. Imaging of Female Pelvic Malignancies Regarding MRI, CT, and PET/CT: Part 2. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2011, 187, 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.D. Imaging of the Vagina and Vulva. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2002, 40, 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, S.A.A.; Richards, P.S.; Ind, T.; Jeyarajah, A.R.; Shepherd, J.H.; Jacobs, I.J.; Reznek, R.H. MR Imaging of Carcinoma of the Vulva. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 2002, 178, 373–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, N.; Grant, L.A.; Sala, E. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Vaginal and Vulval Pathology. Eur. Radiol. 2008, 18, 1269–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paño, B.; Sebastià, C.; Ripoll, E.; Paredes, P.; Salvador, R.; Buñesch, L.; Nicolau, C. Pathways of Lymphatic Spread in Gynecologic Malignancies. Radiographics 2015, 35, 916–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protzel, C.; Alcaraz, A.; Horenblas, S.; Pizzocaro, G.; Zlotta, A.; Hakenberg, O.W. Lymphadenectomy in the Surgical Management of Penile Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2009, 55, 1075–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Standring, S.; Borley, N.R.; Gray, H. Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 40th anniversary ed.; Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier: Edinburgh, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Daseler, E.H.; Anson, B.J.; Reimann, A.F. Radical Excision of the Inguinal and Iliac Lymph Glands; a Study Based upon 450 Anatomical Dissections and upon Supportive Clinical Observations. Surg. Gynecol. Obs. 1948, 87, 679–694. [Google Scholar]

- Collarino, A.; Donswijk, M.L.; van Driel, W.J.; Stokkel, M.P.; Valdés Olmos, R.A. The Use of SPECT/CT for Anatomical Mapping of Lymphatic Drainage in Vulvar Cancer: Possible Implications for the Extent of Inguinal Lymph Node Dissection. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2015, 42, 2064–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonk, M.H.M.; Hollema, H.; de Hullu, J.A.; van der Zee, A.G.J. Prediction of Lymph Node Metastases in Vulvar Cancer: A Review. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2006, 16, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Orakwue, C.O.; Honest, H.; Balogun, M.; Lopez, C.; Luesley, D.M. Accuracy of Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Inguinofemoral Lymph Nodes in Vulval Cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2006, 16, 1179–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischerova, D.; Garganese, G.; Reina, H.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Cibula, D.; Nanka, O.; Rettenbacher, T.; Testa, A.C.; Epstein, E.; Guiggi, I.; et al. Terms, Definitions and Measurements to Describe Sonographic Features of Lymph Nodes: Consensus Opinion from the Vulvar International Tumor Analysis (VITA) Group. Ultrasound Obs. Gynecol. 2021, 57, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garganese, G.; Bove, S.; Fragomeni, S.; Moro, F.; Triumbari, E.K.A.; Collarino, A.; Verri, D.; Gentileschi, S.; Sperduti, I.; Scambia, G.; et al. Real-Time Ultrasound Virtual Navigation in 3D PET/CT Volumes for Superficial Lymph Node Evaluation: An Innovative Fusion Examination. Ultrasound Obs. Gynecol. 2021, 58, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triumbari, E.K.A.; de Koster, E.J.; Rufini, V.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Garganese, G.; Collarino, A. 18F-FDG PET and 18F-FDG PET/CT in Vulvar Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2021, 46, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garganese, G.; Fragomeni, S.M.; Pasciuto, T.; Leombroni, M.; Moro, F.; Evangelista, M.T.; Bove, S.; Gentileschi, S.; Tagliaferri, L.; Paris, I.; et al. Ultrasound Morphometric and Cytologic Preoperative Assessment of Inguinal Lymph-Node Status in Women with Vulvar Cancer: MorphoNode Study. Ultrasound Obs. Gynecol. 2020, 55, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garganese, G.; Romito, A.; Scambia, G.; Fagotti, A. New Developments in Rare Vulvar and Vaginal Cancers. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2021, 33, 485–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Figo Stage | Tumor Spread Description |

|---|---|

| I | Tumor confined to the vulva: |

| IA | lesions ≤ 2 cm in size, confined to the vulva and/or perineum with stromal invasion ≤ 1 mm. No nodal metastasis. |

| IB | lesions > 2 cm in size or any size with stromal invasion > 1 mm confined to the vulva and/or perineum. No nodal metastasis. |

| II | Tumor of any size with extension to adjacent perineal structures (lower 1/3 urethra, lower 1/3 vagina, anus). No nodal metastasis. |

| III | Tumor of any size with or without extension to adjacent perineal structures (lower 1/3 urethra, lower 1/3 vagina, anus) with involvement of inguinofemoral lymph nodes: |

| IIIA | with 1 lymph node metastasis (≥5 mm) or 1–2 lymph node metastases (<5 mm). |

| IIIB | with 2 or more lymph node metastases (≥5 mm) or 3 or more lymph node metastases (<5 mm). |

| IIIC | with positive lymph nodes with extracapsular spread. |

| IV | Tumor with invasion of other regional (upper 2/3 urethra, upper 2/3 vagina) or distant structures: |

| IVA | tumor of any size with extension to any of the following: upper/proximal 2/3 urethra; upper/proximal 2/3 vagina; bladder mucosa; rectal mucosa or fixed to pelvic bone or fixed or ulcerated inguinofemoral lymph nodes. |

| IVB | distant metastasis including pelvic lymph nodes. |

| 1st Author | Year | Patient Number | Study Type | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nikolić [11] | 2021 | Guidelines—Vulvar cancer staging: guidelines of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) | Guidelines for staging vulvar cancer with expert MRI recommendations of patient preparation, protocol, and structured report | |

| Lakhman [26] | 2021 | Guidelines—ACR Appropriateness Criteria. Staging and follow-up of vulvar cancer | Summary of the literature and guidelines for the use of imaging for staging and follow-up of vulvar cancer | |

| Serrado [12] | 2019 | Review—State of the art in vulvar cancer imaging | Imaging (MRI, CT, PET/CT) of vulvar cancer | |

| Shetty [5] | 2017 | Review—MR Imaging of vulvar and vaginal cancer | MRI of vulvar and vaginal cancer | |

| Agarwal [27] | 2017 | Review—MR imaging of the female perineum. Clitoris, labia, and introitus | MRI of female perineum, normal anatomy, benign and malignant pathology | |

| Miccò [2] | 2015 | Review—Imaging features of uncommon gynecologic cancers | Imaging (US, CT, MR, PET/CT) of uncommon gynecologic cancers | |

| Kim [7] | 2013 | Review—Update on imaging of vulvar squamous cell carcinoma | Imaging (MRI, PET/CT) for staging and follow-up of vulvar cancer | |

| Viswanathan [14] | 2013 | Review—Multimodality Imaging of Vulvar Cancer: Staging, Therapeutic Response, and Complications | Imaging (MRI, CT, PET/CT) of vulvar cancer | |

| Hosseinzadeh [15] | 2012 | Review—Imaging of the Female Perineum in Adults | Imaging of female perineum, normal anatomy and pathology of vulva, vagina, urethra and anus | |

| Kataoka [19] | 2010 | 49 | Retrospective—The accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging in staging of vulvar cancer: a retrospective multi-centre study |

Staging accuracy unenhanced MRI 69.4% (n = 36). Adding CE-MRI raised staging accuracy from 75% to 85% (n = 20). |

| Alt [28] | 2011 | Review—Imaging of Female Pelvic Malignancies Regarding MRI, CT and PET/CT | Imaging (MRI, CT, PET/CT) of vulvar, vaginal and ovarian cancer | |

| Griffin [1] | 2008 | Review—Magnetic Resonance Imaging of vaginal and vulval pathology | MRI of vaginal and vulvar benign and malignant pathology | |

| Sohaib [10] | 2003 | Review—Imaging in vulval cancer | Imaging (US, CT, MRI, PET, lymphoscintigraphy for sentinel lymph node) of vulvar cancer | |

| Chang [29] | 2002 | Review—Imaging of the vagina and vulva | Imaging (MRI, US, CT, radiograph, lymphangiography) of vaginal and vulvar benign and malignant pathology | |

| Sohaib [30] | 2002 | 22 | Retrospective—MR Imaging of carcinoma of the vulva | Moderate MRI correlation with clinico-pathological staging of the primary tumor and high specificity for the detection of nodal involvement |

| Sequence | Plane | Objective |

|---|---|---|

| T1WI pelvis | Axial | Panoramic view (lymph nodes, uterus, adnexa, bone) |

| T2WI pelvis | Axial | Panoramic view (lymph nodes, uterus, adnexa, bone) |

| T2WI pelvis | Sagittal | Vulva and adjacent structures (urethra, anus, vagina) |

| T2WI (small FOV) | Axial oblique (perpendicular to the long axis of the urethra) | Vulva and adjacent structures (urethra, anus, vagina) |

| T2WI (small FOV) | Coronal oblique (parallel to the long axis of the urethra) | Vulva and adjacent structures (urethra, anus, vagina) |

| DWI (b 0–1000) (small FOV) | Axial oblique as T2WI (perpendicular to the long axis of the urethra) | Tumor detection and extension |

| T2WI abdomen | Axial | Lymph nodes and hydronephrosis |

| T1WI Multhiphase DCE 3D GRE pelvis | Axial oblique (perpendicular to the long axis of the urethra) | Tumor detection and extension, lymph nodes |

| T1WI DCE 3D GRE pelvis | Coronal oblique (parallel to the long axis of the urethra) | Tumor detection and extension, lymph nodes |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gui, B.; Persiani, S.; Miccò, M.; Pignatelli, V.; Rodolfino, E.; Avesani, G.; Di Paola, V.; Panico, C.; Russo, L.; Fragomeni, S.M.; et al. MRI Staging in Locally Advanced Vulvar Cancer: From Anatomy to Clinico-Radiological Findings. A Multidisciplinary VulCan Team Point of View. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111219

Gui B, Persiani S, Miccò M, Pignatelli V, Rodolfino E, Avesani G, Di Paola V, Panico C, Russo L, Fragomeni SM, et al. MRI Staging in Locally Advanced Vulvar Cancer: From Anatomy to Clinico-Radiological Findings. A Multidisciplinary VulCan Team Point of View. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021; 11(11):1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111219

Chicago/Turabian StyleGui, Benedetta, Salvatore Persiani, Maura Miccò, Vincenza Pignatelli, Elena Rodolfino, Giacomo Avesani, Valerio Di Paola, Camilla Panico, Luca Russo, Simona Maria Fragomeni, and et al. 2021. "MRI Staging in Locally Advanced Vulvar Cancer: From Anatomy to Clinico-Radiological Findings. A Multidisciplinary VulCan Team Point of View" Journal of Personalized Medicine 11, no. 11: 1219. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11111219