An Emulation of Randomized Trials of Administrating Antipsychotics in PTSD Patients for Outcomes of Suicide-Related Events

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Relationship between Antipsychotics and PTSD

1.2. Emulating Randomized Controlled Trial

2. Methods

2.1. Data Source

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria and Endpoints/Follow Up

2.3. Target Trials

2.4. Emulating Target Trials

2.5. Per-Protocol Analysis

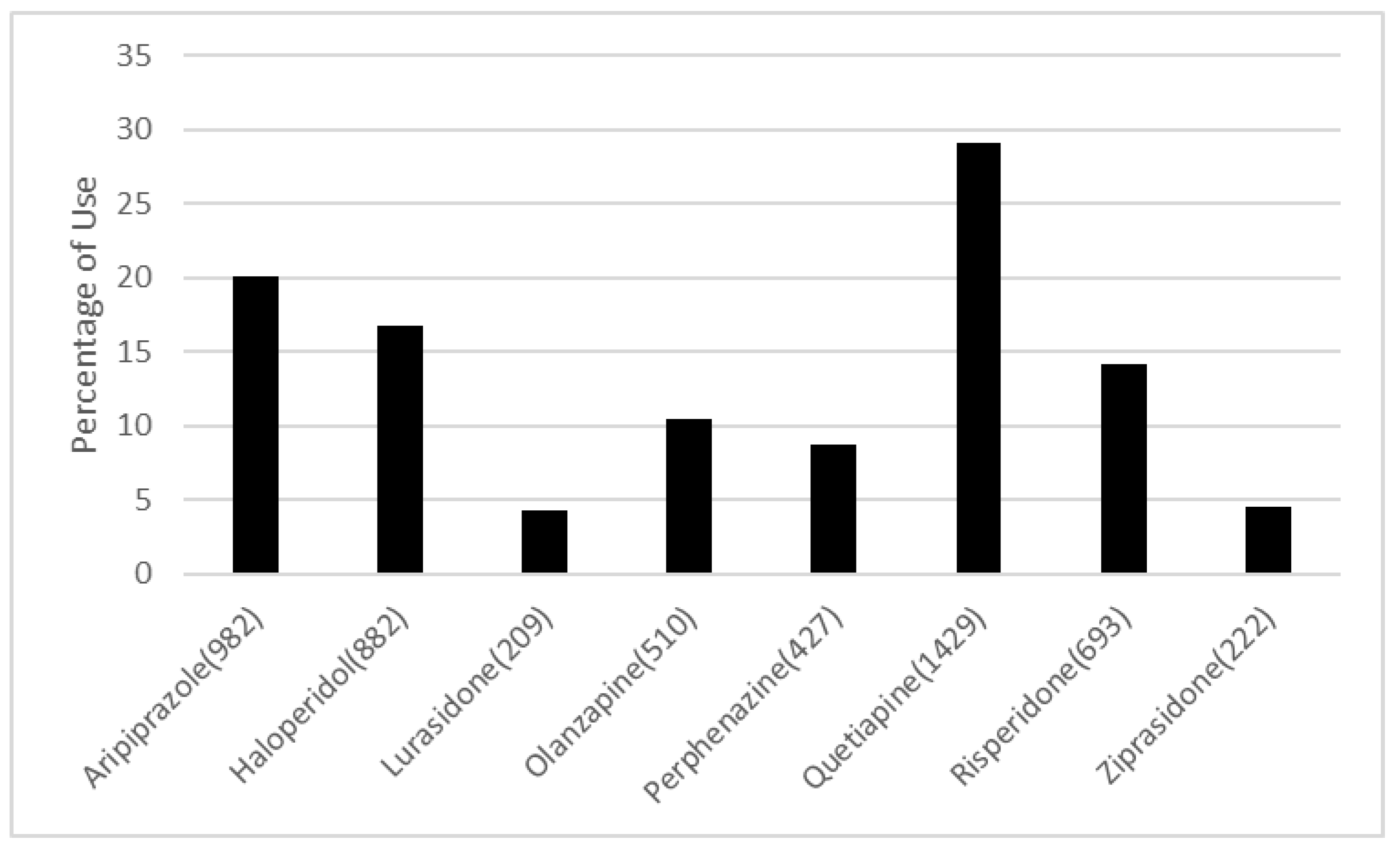

3. Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Diagnosis Codes

- PTSD:

- 309.81, F43.10, F43.11, F43.12

- Suicide-Related Events/Behaviors:

- V62.84,R45.851,E950.3,E956,E950.4,E950.0,E958.8,T14.91,E950.9,E958.9,T14.91XA,E950.5,E950.2,E953.0,E958.1,E953.8,E950.1,E950.7,E952.0,E958.0,E957.1,E957.0,E958.5,E952.1,E955.4,T14.91XD,E950.6,E953.9,E955.0,E957.9,E958.7,E958.3,E954,T14.91XS,E951.0,E951.8,E952.8,E953.1,E955.1,E958.6,E958.2,E955.9,E955.2,X83.8XXA,T42.4X2A,T43.592A,T39.1X2A,X78.8XXA,X78.9XXD,T42.6X2A,X78.9XXA,T43.222A,T50.902A,X83.8XXD,T39.312A,T43.212A,T45.0X2A,X78.1XXA,X78.8XXD,T50.992A,T40.2X2A,T43.292A,T43.012A,T39.012A,T42.8X2A,X78.0XXA,T51.0X2A,T40.5X2A,T40.4X2A,T40.1X2A,T44.7X2A,T38.3X2A,T44.6X2A,T48.1X2A,T46.5X2A,T71.162A,T48.3X2A,T43.022A,T44.3X2A,T50.902D,X79.XXXA,T65.92XA,X78.1XXD,T51.92XA,T42.1X2A,T65.892A,T56.892A,T43.622A,X80.XXXA,T42.4X2D,X78.0XXD,T42.72XA,T43.3X2A,X76.XXXD,T48.4X2A,T51.2X2A,T46.4X2A,T39.1X2D,T40.7X2A,T54.92XA,T40.602A,T45.512A,X76.XXXA,T43.222D,T39.392A,T47.1X2A,T50.902S,X74.9XXD,T39.092A,T38.1X2A,X74.9XXA,T39.312D,T38.892A,T43.612A,X82.8XXA,T42.6X2D,T43.632A,T46.1X2A,T45.0X2D,T50.992D,T54.2X2A,T40.3X2A,T39.012D,T43.4X2A,T58.02XA,T43.592D,X81.0XXA,T43.202A,T43.8X2A,T44.992A,T45.2X2A,T40.1X2D,T41.292A,T50.2X2A,T48.6X2A,T50.7X2A,T49.0X2A,T46.3X2A,T42.0X2A,T36.1X2A,T36.0X2A,X74.9XXS,X72.XXXD,T43.012D,T51.8X2A,T51.0X2D,T54.92XS,T54.3X2A,T65.892D,T65.92XD,T65.222D,T50.3X2A,T48.5X2A,T47.0X2A,T46.6X2A,T65.92XS,T54.1X2A,T52.4X2A,T52.0X2A,T55.1X2A,T59.892A,T42.4X2S,T42.3X2A,T36.3X2A,T37.8X2A,T38.2X2A,T38.3X2D,T40.992A,T40.8X2A,T44.4X2A,T43.692A,T45.2X2D,T44.7X2D,T43.502A,T71.192A,X79.XXXD,X83.2XXA,X83.8XXS,X72.XXXA,X71.9XXA,T48.202A,T40.2X2D,X74.8XXS,T48.3X2D,T39.8X2A,T47.4X2A,T47.6X2A,T50.6X2A,T49.6X2D,T43.3X2D,T50.5X2A,X74.01XA,X73.0XXA,T49.6X2A,X72.XXXS,X78.9XXS,T39.92XA,X80.XXXD,X81.8XXA,T39.4X2A,X77.8XXA,T50.2X2D,T43.622D,T43.292D,T45.4X2A,T46.0X2A,T41.3X2A,T42.5X2A,T42.6X2,T46.7X2A,T46.8X2A,T46.5X2D,T43.1X2A,T43.92XA,T40.5X2D,X71.0XXS,X71.3XXA,X71.8XXA,T43.212D,T46.2X2A,T40.8X2D,T40.602D,T43.022D,T44.1X2A,T46.4X2D,T65.222S,T62.0X2A,T71.162D,T51.1X2A,T51.2X2D,T51.2X2S,T52.8X2A,T51.92XD,T50.8X2A,T56.892D,T58.92XA,T54.3X2S,T54.3X2D,T54.0X2A,T55.0X2A,T36.0X2D,T36.4X2A,T38.5X2A,T36.8X2A,T37.5X2A

Appendix B

| ICD9 Code | Disease Name | Category | ICD9 Code | Disease Name | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 291 | Alcohol-induced mental disorders | 1 | 301 (not 301.1 or 301.2) | Personality disorders (not Affective personality disorder or Schizoid personality disorder) | 6 |

| 292 | Drug-induced mental disorders | 1 | 302 | Sexual and gender identity disorders | 7 |

| 303 | Alcohol dependence syndrome | 1 | 306 | Physiological malfunction arising from mental factors | 8 |

| 304 | Drug dependence | 1 | 316 | Psychic factor w oth dis. | 8 |

| 305 (not 305.1) | Nondependent abuse of drugs (not Tobacco use disorder) | 1 | 307 | Special symptoms or syndromes not elsewhere classified | 9 |

| 295 | Schizophrenic disorders | 2 | 290 | Dementias | 10 |

| 301.2 | Schizoid personality disorder | 2 | 293 | Transient mental disorders due to conditions classified elsewhere | 10 |

| 296 | Episodic mood disorders | 3 | 294 | Persistent mental disorders due to conditions classified elsewhere | 10 |

| 298 | Depressive-type psychosis | 3 | 310 | Specific nonpsychotic mental disorders due to brain damage | 10 |

| 300.4 | Dysthymic disorder | 3 | 299 | Autistic disorder-current | 11 |

| 301.1 | Affective personality disorder | 3 | 312 | Disturbance of conduct not elsewhere classified | 11 |

| 309 | Adjustment reaction | 3 | 313 | Disturbance of emotions specific to childhood and adolescence | 11 |

| 311 | Depressive disorder NEC | 3 | 314 | Hyperkinetic syndrome of childhood | 11 |

| 297 | Delusional disorders | 4 | 315 | Specific delays in development | 11 |

| 298 (but not 2980) | Other nonorganic psychoses (not depressive-type psychosis) | 4 | 317 | Mild intellectual disabilities | 12 |

| 308 | Acute reaction to stress | 5 | 318 | Other specified intellectual disabilities | 12 |

| 300 (but not 300.4) | Anxiety, dissociative and somatoform disorders (not dysthymic disorder) | 5 | 319 | Unspecified intellectual disabilities | 12 |

Appendix C

| Level | Aripiprazole | Haloperidol | Lurasidone | Olanzapine | Perphenazine | Quetiapine | Risperidone | Ziprasidone | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 982 | 822 | 209 | 510 | 427 | 1429 | 693 | 222 | ||

| Acetaminophen (%) | 0 | 673 (68.5) | 230 (28.0) | 144 (68.9) | 303 (59.4) | 75 (17.6) | 850 (59.5) | 461 (66.5) | 144 (64.9) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 309 (31.5) | 592 (72.0) | 65 (31.1) | 207 (40.6) | 352 (82.4) | 579 (40.5) | 232 (33.5) | 78 (35.1) | ||

| Almotriptan (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.606 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Alprazolam (%) | 0 | 910 (92.7) | 760 (92.5) | 193 (92.3) | 461 (90.4) | 386 (90.4) | 1285 (89.9) | 650 (93.8) | 210 (94.6) | 0.022 |

| 1 | 72 (7.3) | 62 (7.5) | 16 (7.7) | 49 (9.6) | 41 (9.6) | 144 (10.1) | 43 (6.2) | 12 (5.4) | ||

| Amitriptyline (%) | 0 | 932 (94.9) | 783 (95.3) | 195 (93.3) | 489 (95.9) | 407 (95.3) | 1379 (96.5) | 666 (96.1) | 216 (97.3) | 0.259 |

| 1 | 50 (5.1) | 39 (4.7) | 14 (6.7) | 21 (4.1) | 20 (4.7) | 50 (3.5) | 27 (3.9) | 6 (2.7) | ||

| Amphetamine (%) | 0 | 930 (94.7) | 809 (98.4) | 202 (96.7) | 493 (96.7) | 418 (97.9) | 1389 (97.2) | 665 (96.0) | 216 (97.3) | 0.001 |

| 1 | 52 (5.3) | 13 (1.6) | 7 (3.3) | 17 (3.3) | 9 (2.1) | 40 (2.8) | 28 (4.0) | 6 (2.7) | ||

| Aripiprazole (%) | 0 | 0 (0.0) | 820 (99.8) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1426 (99.8) | 690 (99.6) | 222 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 982 (100.0) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Armodafinil (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 426 (99.8) | 1427 (99.9) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.88 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Aspirin (%) | 0 | 918 (93.5) | 664 (80.8) | 197 (94.3) | 442 (86.7) | 377 (88.3) | 1273 (89.1) | 625 (90.2) | 204 (91.9) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 64 (6.5) | 158 (19.2) | 12 (5.7) | 68 (13.3) | 50 (11.7) | 156 (10.9) | 68 (9.8) | 18 (8.1) | ||

| Atomoxetine (%) | 0 | 960 (97.8) | 818 (99.5) | 205 (98.1) | 503 (98.6) | 424 (99.3) | 1405 (98.3) | 680 (98.1) | 220 (99.1) | 0.07 |

| 1 | 22 (2.2) | 4 (0.5) | 4 (1.9) | 7 (1.4) | 3 (0.7) | 24 (1.7) | 13 (1.9) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Atropine (%) | 0 | 976 (99.4) | 753 (91.6) | 205 (98.1) | 496 (97.3) | 417 (97.7) | 1387 (97.1) | 680 (98.1) | 217 (97.7) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 6 (0.6) | 69 (8.4) | 4 (1.9) | 14 (2.7) | 10 (2.3) | 42 (2.9) | 13 (1.9) | 5 (2.3) | ||

| Benzoate (%) | 0 | 963 (98.1) | 810 (98.5) | 206 (98.6) | 495 (97.1) | 419 (98.1) | 1409 (98.6) | 683 (98.6) | 218 (98.2) | 0.488 |

| 1 | 19 (1.9) | 12 (1.5) | 3 (1.4) | 15 (2.9) | 8 (1.9) | 20 (1.4) | 10 (1.4) | 4 (1.8) | ||

| Brompheniramine (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1427 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.809 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Buprenorphine (%) | 0 | 950 (96.7) | 803 (97.7) | 203 (97.1) | 494 (96.9) | 418 (97.9) | 1381 (96.6) | 676 (97.5) | 212 (95.5) | 0.552 |

| 1 | 32 (3.3) | 19 (2.3) | 6 (2.9) | 16 (3.1) | 9 (2.1) | 48 (3.4) | 17 (2.5) | 10 (4.5) | ||

| Bupropion (%) | 0 | 834 (84.9) | 755 (91.8) | 183 (87.6) | 465 (91.2) | 382 (89.5) | 1286 (90.0) | 625 (90.2) | 192 (86.5) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 148 (15.1) | 67 (8.2) | 26 (12.4) | 45 (8.8) | 45 (10.5) | 143 (10.0) | 68 (9.8) | 30 (13.5) | ||

| Buspirone (%) | 0 | 904 (92.1) | 783 (95.3) | 183 (87.6) | 474 (92.9) | 406 (95.1) | 1312 (91.8) | 639 (92.2) | 204 (91.9) | 0.002 |

| 1 | 78 (7.9) | 39 (4.7) | 26 (12.4) | 36 (7.1) | 21 (4.9) | 117 (8.2) | 54 (7.8) | 18 (8.1) | ||

| Butalbital (%) | 0 | 980 (99.8) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.753 |

| 1 | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Butorphanol (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 819 (99.6) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.488 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Caffeine (%) | 0 | 972 (99.0) | 811 (98.7) | 206 (98.6) | 498 (97.6) | 418 (97.9) | 1411 (98.7) | 686 (99.0) | 220 (99.1) | 0.38 |

| 1 | 10 (1.0) | 11 (1.3) | 3 (1.4) | 12 (2.4) | 9 (2.1) | 18 (1.3) | 7 (1.0) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Calcium Carbonate (%) | 0 | 963 (98.1) | 806 (98.1) | 207 (99.0) | 499 (97.8) | 403 (94.4) | 1400 (98.0) | 677 (97.7) | 218 (98.2) | 0.001 |

| 1 | 19 (1.9) | 16 (1.9) | 2 (1.0) | 11 (2.2) | 24 (5.6) | 29 (2.0) | 16 (2.3) | 4 (1.8) | ||

| Carbamazepine (%) | 0 | 968 (98.6) | 811 (98.7) | 203 (97.1) | 497 (97.5) | 424 (99.3) | 1411 (98.7) | 673 (97.1) | 218 (98.2) | 0.033 |

| 1 | 14 (1.4) | 11 (1.3) | 6 (2.9) | 13 (2.5) | 3 (0.7) | 18 (1.3) | 20 (2.9) | 4 (1.8) | ||

| Carbidopa (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 423 (99.1) | 1426 (99.8) | 692 (99.9) | 221 (99.5) | 0.015 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.9) | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Carisoprodol (%) | 0 | 972 (99.0) | 809 (98.4) | 207 (99.0) | 504 (98.8) | 421 (98.6) | 1410 (98.7) | 685 (98.8) | 217 (97.7) | 0.877 |

| 1 | 10 (1.0) | 13 (1.6) | 2 (1.0) | 6 (1.2) | 6 (1.4) | 19 (1.3) | 8 (1.2) | 5 (2.3) | ||

| Chlordiazepoxide (%) | 0 | 980 (99.8) | 807 (98.2) | 206 (98.6) | 506 (99.2) | 424 (99.3) | 1410 (98.7) | 681 (98.3) | 222 (100.0) | 0.011 |

| 1 | 2 (0.2) | 15 (1.8) | 3 (1.4) | 4 (0.8) | 3 (0.7) | 19 (1.3) | 12 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Chlorpheniramine (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 691 (99.7) | 222 (100.0) | 0.254 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Chlorpromazine (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.734 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Chlorthalidone (%) | 0 | 978 (99.6) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 508 (99.6) | 426 (99.8) | 1424 (99.7) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.82 |

| 1 | 4 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Choline (%) | 0 | 956 (97.4) | 636 (77.4) | 203 (97.1) | 480 (94.1) | 260 (60.9) | 1369 (95.8) | 669 (96.5) | 216 (97.3) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 26 (2.6) | 186 (22.6) | 6 (2.9) | 30 (5.9) | 167 (39.1) | 60 (4.2) | 24 (3.5) | 6 (2.7) | ||

| Citalopram (%) | 0 | 821 (83.6) | 724 (88.1) | 179 (85.6) | 435 (85.3) | 384 (89.9) | 1193 (83.5) | 576 (83.1) | 200 (90.1) | 0.001 |

| 1 | 161 (16.4) | 98 (11.9) | 30 (14.4) | 75 (14.7) | 43 (10.1) | 236 (16.5) | 117 (16.9) | 22 (9.9) | ||

| Clidinium (%) | 0 | 978 (99.6) | 816 (99.3) | 209 (100.0) | 507 (99.4) | 426 (99.8) | 1425 (99.7) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.444 |

| 1 | 4 (0.4) | 6 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Clobazam (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 221 (99.5) | 0.034 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Clomipramine (%) | 0 | 980 (99.8) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 691 (99.7) | 220 (99.1) | 0.094 |

| 1 | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Clonazepam (%) | 0 | 809 (82.4) | 730 (88.8) | 182 (87.1) | 423 (82.9) | 378 (88.5) | 1179 (82.5) | 587 (84.7) | 179 (80.6) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 173 (17.6) | 92 (11.2) | 27 (12.9) | 87 (17.1) | 49 (11.5) | 250 (17.5) | 106 (15.3) | 43 (19.4) | ||

| Clonidine (%) | 0 | 951 (96.8) | 755 (91.8) | 202 (96.7) | 465 (91.2) | 387 (90.6) | 1332 (93.2) | 641 (92.5) | 212 (95.5) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 31 (3.2) | 67 (8.2) | 7 (3.3) | 45 (8.8) | 40 (9.4) | 97 (6.8) | 52 (7.5) | 10 (4.5) | ||

| Clorazepate (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 508 (99.6) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.278 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Codeine (%) | 0 | 955 (97.3) | 785 (95.5) | 205 (98.1) | 496 (97.3) | 410 (96.0) | 1386 (97.0) | 677 (97.7) | 216 (97.3) | 0.208 |

| 1 | 27 (2.7) | 37 (4.5) | 4 (1.9) | 14 (2.7) | 17 (4.0) | 43 (3.0) | 16 (2.3) | 6 (2.7) | ||

| Desipramine (%) | 0 | 979 (99.7) | 822 (100.0) | 208 (99.5) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.278 |

| 1 | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Desvenlafaxine (%) | 0 | 977 (99.5) | 817 (99.4) | 208 (99.5) | 509 (99.8) | 425 (99.5) | 1423 (99.6) | 688 (99.3) | 217 (97.7) | 0.062 |

| 1 | 5 (0.5) | 5 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 6 (0.4) | 5 (0.7) | 5 (2.3) | ||

| Dexmedetomidine (%) | 0 | 969 (98.7) | 698 (84.9) | 205 (98.1) | 496 (97.3) | 307 (71.9) | 1394 (97.6) | 687 (99.1) | 220 (99.1) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 13 (1.3) | 124 (15.1) | 4 (1.9) | 14 (2.7) | 120 (28.1) | 35 (2.4) | 6 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Dexmethylphenidate (%) | 0 | 978 (99.6) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 508 (99.6) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 689 (99.4) | 220 (99.1) | 0.053 |

| 1 | 4 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Dextroamphetamine (%) | 0 | 930 (94.7) | 809 (98.4) | 202 (96.7) | 493 (96.7) | 418 (97.9) | 1389 (97.2) | 665 (96.0) | 216 (97.3) | 0.001 |

| 1 | 52 (5.3) | 13 (1.6) | 7 (3.3) | 17 (3.3) | 9 (2.1) | 40 (2.8) | 28 (4.0) | 6 (2.7) | ||

| Dextromethorphan (%) | 0 | 980 (99.8) | 816 (99.3) | 207 (99.0) | 509 (99.8) | 424 (99.3) | 1420 (99.4) | 690 (99.6) | 222 (100.0) | 0.477 |

| 1 | 2 (0.2) | 6 (0.7) | 2 (1.0) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.7) | 9 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Diazepam (%) | 0 | 941 (95.8) | 755 (91.8) | 197 (94.3) | 485 (95.1) | 409 (95.8) | 1357 (95.0) | 662 (95.5) | 214 (96.4) | 0.006 |

| 1 | 41 (4.2) | 67 (8.2) | 12 (5.7) | 25 (4.9) | 18 (4.2) | 72 (5.0) | 31 (4.5) | 8 (3.6) | ||

| Dihydroergotamine (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 817 (99.4) | 209 (100.0) | 503 (98.6) | 426 (99.8) | 1425 (99.7) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.004 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.4) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Dimenhydrinate (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 817 (99.4) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 406 (95.1) | 1428 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 21 (4.9) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Diphenhydramine (%) | 0 | 925 (94.2) | 591 (71.9) | 195 (93.3) | 438 (85.9) | 350 (82.0) | 1289 (90.2) | 634 (91.5) | 206 (92.8) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 57 (5.8) | 231 (28.1) | 14 (6.7) | 72 (14.1) | 77 (18.0) | 140 (9.8) | 59 (8.5) | 16 (7.2) | ||

| Dipyridamole (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 426 (99.8) | 1428 (99.9) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.717 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Donepezil (%) | 0 | 978 (99.6) | 818 (99.5) | 208 (99.5) | 509 (99.8) | 426 (99.8) | 1415 (99.0) | 683 (98.6) | 221 (99.5) | 0.079 |

| 1 | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 14 (1.0) | 10 (1.4) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Doxepin (%) | 0 | 953 (97.0) | 795 (96.7) | 204 (97.6) | 495 (97.1) | 419 (98.1) | 1386 (97.0) | 677 (97.7) | 209 (94.1) | 0.197 |

| 1 | 29 (3.0) | 27 (3.3) | 5 (2.4) | 15 (2.9) | 8 (1.9) | 43 (3.0) | 16 (2.3) | 13 (5.9) | ||

| Doxylamine (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 208 (99.5) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1426 (99.8) | 693 (100.0) | 221 (99.5) | 0.118 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Duloxetine (%) | 0 | 874 (89.0) | 766 (93.2) | 185 (88.5) | 455 (89.2) | 394 (92.3) | 1291 (90.3) | 652 (94.1) | 203 (91.4) | 0.002 |

| 1 | 108 (11.0) | 56 (6.8) | 24 (11.5) | 55 (10.8) | 33 (7.7) | 138 (9.7) | 41 (5.9) | 19 (8.6) | ||

| Eletriptan (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 508 (99.6) | 425 (99.5) | 1428 (99.9) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.285 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Ergotamine (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 817 (99.4) | 209 (100.0) | 502 (98.4) | 426 (99.8) | 1425 (99.7) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.001 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 5 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (1.6) | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Escitalopram (%) | 0 | 903 (92.0) | 786 (95.6) | 193 (92.3) | 476 (93.3) | 409 (95.8) | 1336 (93.5) | 644 (92.9) | 211 (95.0) | 0.03 |

| 1 | 79 (8.0) | 36 (4.4) | 16 (7.7) | 34 (6.7) | 18 (4.2) | 93 (6.5) | 49 (7.1) | 11 (5.0) | ||

| Estazolam (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.226 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Eszopiclone (%) | 0 | 977 (99.5) | 821 (99.9) | 208 (99.5) | 509 (99.8) | 425 (99.5) | 1423 (99.6) | 691 (99.7) | 220 (99.1) | 0.744 |

| 1 | 5 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 6 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Fentanyl (%) | 0 | 903 (92.0) | 436 (53.0) | 196 (93.8) | 434 (85.1) | 191 (44.7) | 1233 (86.3) | 616 (88.9) | 202 (91.0) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 79 (8.0) | 386 (47.0) | 13 (6.2) | 76 (14.9) | 236 (55.3) | 196 (13.7) | 77 (11.1) | 20 (9.0) | ||

| Fluoxetine (%) | 0 | 871 (88.7) | 761 (92.6) | 188 (90.0) | 440 (86.3) | 385 (90.2) | 1291 (90.3) | 603 (87.0) | 206 (92.8) | 0.002 |

| 1 | 111 (11.3) | 61 (7.4) | 21 (10.0) | 70 (13.7) | 42 (9.8) | 138 (9.7) | 90 (13.0) | 16 (7.2) | ||

| Fluphenazine (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 820 (99.8) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.144 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Flurazepam (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.553 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Fluvoxamine (%) | 0 | 976 (99.4) | 818 (99.5) | 207 (99.0) | 506 (99.2) | 426 (99.8) | 1419 (99.3) | 689 (99.4) | 220 (99.1) | 0.94 |

| 1 | 6 (0.6) | 4 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (0.8) | 1 (0.2) | 10 (0.7) | 4 (0.6) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Frovatriptan (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.817 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Gabapentin (%) | 0 | 797 (81.2) | 605 (73.6) | 147 (70.3) | 384 (75.3) | 264 (61.8) | 1069 (74.8) | 564 (81.4) | 168 (75.7) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 185 (18.8) | 217 (26.4) | 62 (29.7) | 126 (24.7) | 163 (38.2) | 360 (25.2) | 129 (18.6) | 54 (24.3) | ||

| Galantamine (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.923 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Guaifenesin (%) | 0 | 963 (98.1) | 769 (93.6) | 202 (96.7) | 493 (96.7) | 421 (98.6) | 1370 (95.9) | 677 (97.7) | 217 (97.7) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 19 (1.9) | 53 (6.4) | 7 (3.3) | 17 (3.3) | 6 (1.4) | 59 (4.1) | 16 (2.3) | 5 (2.3) | ||

| Haloperidol (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 822 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Homatropine (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 816 (99.3) | 209 (100.0) | 505 (99.0) | 424 (99.3) | 1416 (99.1) | 690 (99.6) | 220 (99.1) | 0.223 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 6 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (1.0) | 3 (0.7) | 13 (0.9) | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Hydrocodone (%) | 0 | 859 (87.5) | 682 (83.0) | 176 (84.2) | 451 (88.4) | 328 (76.8) | 1245 (87.1) | 612 (88.3) | 195 (87.8) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 123 (12.5) | 140 (17.0) | 33 (15.8) | 59 (11.6) | 99 (23.2) | 184 (12.9) | 81 (11.7) | 27 (12.2) | ||

| Hydromorphone (%) | 0 | 897 (91.3) | 418 (50.9) | 190 (90.9) | 430 (84.3) | 107 (25.1) | 1181 (82.6) | 613 (88.5) | 196 (88.3) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 85 (8.7) | 404 (49.1) | 19 (9.1) | 80 (15.7) | 320 (74.9) | 248 (17.4) | 80 (11.5) | 26 (11.7) | ||

| Hyoscyamine (%) | 0 | 976 (99.4) | 804 (97.8) | 207 (99.0) | 507 (99.4) | 419 (98.1) | 1422 (99.5) | 693 (100.0) | 220 (99.1) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 6 (0.6) | 18 (2.2) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (0.6) | 8 (1.9) | 7 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Ibuprofen (%) | 0 | 840 (85.5) | 637 (77.5) | 167 (79.9) | 428 (83.9) | 274 (64.2) | 1173 (82.1) | 574 (82.8) | 189 (85.1) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 142 (14.5) | 185 (22.5) | 42 (20.1) | 82 (16.1) | 153 (35.8) | 256 (17.9) | 119 (17.2) | 33 (14.9) | ||

| Imipramine (%) | 0 | 979 (99.7) | 821 (99.9) | 207 (99.0) | 507 (99.4) | 426 (99.8) | 1418 (99.2) | 691 (99.7) | 222 (100.0) | 0.235 |

| 1 | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (1.0) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) | 11 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Lacosamide (%) | 0 | 980 (99.8) | 819 (99.6) | 208 (99.5) | 508 (99.6) | 427 (100.0) | 1427 (99.9) | 691 (99.7) | 220 (99.1) | 0.48 |

| 1 | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Lamotrigine (%) | 0 | 889 (90.5) | 784 (95.4) | 167 (79.9) | 459 (90.0) | 408 (95.6) | 1318 (92.2) | 628 (90.6) | 187 (84.2) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 93 (9.5) | 38 (4.6) | 42 (20.1) | 51 (10.0) | 19 (4.4) | 111 (7.8) | 65 (9.4) | 35 (15.8) | ||

| Levetiracetam (%) | 0 | 965 (98.3) | 773 (94.0) | 200 (95.7) | 485 (95.1) | 419 (98.1) | 1380 (96.6) | 680 (98.1) | 216 (97.3) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 17 (1.7) | 49 (6.0) | 9 (4.3) | 25 (4.9) | 8 (1.9) | 49 (3.4) | 13 (1.9) | 6 (2.7) | ||

| Levodopa (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 425 (99.5) | 1427 (99.9) | 692 (99.9) | 221 (99.5) | 0.316 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Levomilnacipran (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 208 (99.5) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1427 (99.9) | 689 (99.4) | 221 (99.5) | 0.177 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 4 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Lisdexamfetamine (%) | 0 | 955 (97.3) | 822 (100.0) | 203 (97.1) | 505 (99.0) | 421 (98.6) | 1416 (99.1) | 676 (97.5) | 222 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 27 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (2.9) | 5 (1.0) | 6 (1.4) | 13 (0.9) | 17 (2.5) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Lithium (%) | 0 | 950 (96.7) | 812 (98.8) | 183 (87.6) | 487 (95.5) | 420 (98.4) | 1370 (95.9) | 668 (96.4) | 214 (96.4) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 32 (3.3) | 10 (1.2) | 26 (12.4) | 23 (4.5) | 7 (1.6) | 59 (4.1) | 25 (3.6) | 8 (3.6) | ||

| Lorazepam (%) | 0 | 841 (85.6) | 359 (43.7) | 173 (82.8) | 388 (76.1) | 375 (87.8) | 1140 (79.8) | 595 (85.9) | 202 (91.0) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 141 (14.4) | 463 (56.3) | 36 (17.2) | 122 (23.9) | 52 (12.2) | 289 (20.2) | 98 (14.1) | 20 (9.0) | ||

| Lurasidone (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 209 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Magnesium Carbonate (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.734 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Meclizine (%) | 0 | 970 (98.8) | 807 (98.2) | 208 (99.5) | 496 (97.3) | 420 (98.4) | 1407 (98.5) | 681 (98.3) | 221 (99.5) | 0.244 |

| 1 | 12 (1.2) | 15 (1.8) | 1 (0.5) | 14 (2.7) | 7 (1.6) | 22 (1.5) | 12 (1.7) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Melatonin (%) | 0 | 952 (96.9) | 735 (89.4) | 201 (96.2) | 463 (90.8) | 413 (96.7) | 1346 (94.2) | 659 (95.1) | 209 (94.1) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 30 (3.1) | 87 (10.6) | 8 (3.8) | 47 (9.2) | 14 (3.3) | 83 (5.8) | 34 (4.9) | 13 (5.9) | ||

| Memantine (%) | 0 | 976 (99.4) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1423 (99.6) | 690 (99.6) | 221 (99.5) | 0.303 |

| 1 | 6 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Meperidine (%) | 0 | 974 (99.2) | 772 (93.9) | 208 (99.5) | 499 (97.8) | 416 (97.4) | 1415 (99.0) | 684 (98.7) | 221 (99.5) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 8 (0.8) | 50 (6.1) | 1 (0.5) | 11 (2.2) | 11 (2.6) | 14 (1.0) | 9 (1.3) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Methadone (%) | 0 | 971 (98.9) | 788 (95.9) | 206 (98.6) | 501 (98.2) | 426 (99.8) | 1402 (98.1) | 681 (98.3) | 219 (98.6) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 11 (1.1) | 34 (4.1) | 3 (1.4) | 9 (1.8) | 1 (0.2) | 27 (1.9) | 12 (1.7) | 3 (1.4) | ||

| Methocarbamol (%) | 0 | 962 (98.0) | 801 (97.4) | 202 (96.7) | 498 (97.6) | 415 (97.2) | 1381 (96.6) | 685 (98.8) | 216 (97.3) | 0.136 |

| 1 | 20 (2.0) | 21 (2.6) | 7 (3.3) | 12 (2.4) | 12 (2.8) | 48 (3.4) | 8 (1.2) | 6 (2.7) | ||

| Methylergonovine (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 504 (98.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Methylnaltrexone (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 819 (99.6) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.088 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Methylphenidate (%) | 0 | 944 (96.1) | 812 (98.8) | 206 (98.6) | 495 (97.1) | 424 (99.3) | 1399 (97.9) | 661 (95.4) | 215 (96.8) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 38 (3.9) | 10 (1.2) | 3 (1.4) | 15 (2.9) | 3 (0.7) | 30 (2.1) | 32 (4.6) | 7 (3.2) | ||

| Metoclopramide (%) | 0 | 953 (97.0) | 727 (88.4) | 205 (98.1) | 483 (94.7) | 408 (95.6) | 1352 (94.6) | 664 (95.8) | 215 (96.8) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 29 (3.0) | 95 (11.6) | 4 (1.9) | 27 (5.3) | 19 (4.4) | 77 (5.4) | 29 (4.2) | 7 (3.2) | ||

| Midazolam (%) | 0 | 914 (93.1) | 469 (57.1) | 197 (94.3) | 443 (86.9) | 86 (20.1) | 1272 (89.0) | 636 (91.8) | 206 (92.8) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 68 (6.9) | 353 (42.9) | 12 (5.7) | 67 (13.1) | 341 (79.9) | 157 (11.0) | 57 (8.2) | 16 (7.2) | ||

| Milnacipran (%) | 0 | 975 (99.3) | 822 (100.0) | 207 (99.0) | 508 (99.6) | 426 (99.8) | 1426 (99.8) | 689 (99.4) | 221 (99.5) | 0.19 |

| 1 | 7 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.0) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 4 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Mirtazapine (%) | 0 | 914 (93.1) | 760 (92.5) | 198 (94.7) | 454 (89.0) | 415 (97.2) | 1308 (91.5) | 628 (90.6) | 209 (94.1) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 68 (6.9) | 62 (7.5) | 11 (5.3) | 56 (11.0) | 12 (2.8) | 121 (8.5) | 65 (9.4) | 13 (5.9) | ||

| Modafinil (%) | 0 | 978 (99.6) | 819 (99.6) | 208 (99.5) | 509 (99.8) | 425 (99.5) | 1423 (99.6) | 690 (99.6) | 222 (100.0) | 0.979 |

| 1 | 4 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 6 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Morphine (%) | 0 | 926 (94.3) | 653 (79.4) | 197 (94.3) | 457 (89.6) | 270 (63.2) | 1294 (90.6) | 649 (93.7) | 213 (95.9) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 56 (5.7) | 169 (20.6) | 12 (5.7) | 53 (10.4) | 157 (36.8) | 135 (9.4) | 44 (6.3) | 9 (4.1) | ||

| Nalbuphine (%) | 0 | 973 (99.1) | 782 (95.1) | 206 (98.6) | 507 (99.4) | 379 (88.8) | 1410 (98.7) | 685 (98.8) | 221 (99.5) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 9 (0.9) | 40 (4.9) | 3 (1.4) | 3 (0.6) | 48 (11.2) | 19 (1.3) | 8 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Naloxone (%) | 0 | 935 (95.2) | 708 (86.1) | 200 (95.7) | 473 (92.7) | 386 (90.4) | 1327 (92.9) | 654 (94.4) | 207 (93.2) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 47 (4.8) | 114 (13.9) | 9 (4.3) | 37 (7.3) | 41 (9.6) | 102 (7.1) | 39 (5.6) | 15 (6.8) | ||

| Naltrexone (%) | 0 | 973 (99.1) | 814 (99.0) | 206 (98.6) | 506 (99.2) | 425 (99.5) | 1400 (98.0) | 687 (99.1) | 217 (97.7) | 0.048 |

| 1 | 9 (0.9) | 8 (1.0) | 3 (1.4) | 4 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) | 29 (2.0) | 6 (0.9) | 5 (2.3) | ||

| Naproxen (%) | 0 | 929 (94.6) | 764 (92.9) | 202 (96.7) | 486 (95.3) | 396 (92.7) | 1342 (93.9) | 653 (94.2) | 212 (95.5) | 0.287 |

| 1 | 53 (5.4) | 58 (7.1) | 7 (3.3) | 24 (4.7) | 31 (7.3) | 87 (6.1) | 40 (5.8) | 10 (4.5) | ||

| Naratriptan (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 508 (99.6) | 424 (99.3) | 1429 (100.0) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.019 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Nefazodone (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 208 (99.5) | 510 (100.0) | 426 (99.8) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.018 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Nortriptyline (%) | 0 | 962 (98.0) | 812 (98.8) | 208 (99.5) | 495 (97.1) | 419 (98.1) | 1406 (98.4) | 679 (98.0) | 220 (99.1) | 0.226 |

| 1 | 20 (2.0) | 10 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) | 15 (2.9) | 8 (1.9) | 23 (1.6) | 14 (2.0) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Olanzapine (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 426 (99.8) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 510 (100.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Omeprazole (%) | 0 | 837 (85.2) | 705 (85.8) | 177 (84.7) | 442 (86.7) | 349 (81.7) | 1222 (85.5) | 596 (86.0) | 198 (89.2) | 0.312 |

| 1 | 145 (14.8) | 117 (14.2) | 32 (15.3) | 68 (13.3) | 78 (18.3) | 207 (14.5) | 97 (14.0) | 24 (10.8) | ||

| Opium (%) | 0 | 947 (96.4) | 776 (94.4) | 203 (97.1) | 480 (94.1) | 409 (95.8) | 1349 (94.4) | 669 (96.5) | 209 (94.1) | 0.07 |

| 1 | 35 (3.6) | 46 (5.6) | 6 (2.9) | 30 (5.9) | 18 (4.2) | 80 (5.6) | 24 (3.5) | 13 (5.9) | ||

| Orphenadrine (%) | 0 | 978 (99.6) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 504 (98.8) | 426 (99.8) | 1418 (99.2) | 691 (99.7) | 222 (100.0) | 0.064 |

| 1 | 4 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.2) | 1 (0.2) | 11 (0.8) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Oxazepam (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1427 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.809 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Oxcarbazepine (%) | 0 | 969 (98.7) | 817 (99.4) | 205 (98.1) | 502 (98.4) | 423 (99.1) | 1405 (98.3) | 680 (98.1) | 217 (97.7) | 0.349 |

| 1 | 13 (1.3) | 5 (0.6) | 4 (1.9) | 8 (1.6) | 4 (0.9) | 24 (1.7) | 13 (1.9) | 5 (2.3) | ||

| Oxycodone (%) | 0 | 840 (85.5) | 480 (58.4) | 176 (84.2) | 411 (80.6) | 125 (29.3) | 1108 (77.5) | 583 (84.1) | 194 (87.4) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 142 (14.5) | 342 (41.6) | 33 (15.8) | 99 (19.4) | 302 (70.7) | 321 (22.5) | 110 (15.9) | 28 (12.6) | ||

| Oxymorphone (%) | 0 | 974 (99.2) | 811 (98.7) | 208 (99.5) | 502 (98.4) | 418 (97.9) | 1410 (98.7) | 683 (98.6) | 218 (98.2) | 0.562 |

| 1 | 8 (0.8) | 11 (1.3) | 1 (0.5) | 8 (1.6) | 9 (2.1) | 19 (1.3) | 10 (1.4) | 4 (1.8) | ||

| Pamabrom (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 208 (99.5) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.001 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Paroxetine (%) | 0 | 946 (96.3) | 796 (96.8) | 207 (99.0) | 495 (97.1) | 417 (97.7) | 1355 (94.8) | 660 (95.2) | 215 (96.8) | 0.01 |

| 1 | 36 (3.7) | 26 (3.2) | 2 (1.0) | 15 (2.9) | 10 (2.3) | 74 (5.2) | 33 (4.8) | 7 (3.2) | ||

| Pentazocine (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.226 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Pentobarbital (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.606 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Perphenazine (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 427 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Phenazopyridine (%) | 0 | 968 (98.6) | 801 (97.4) | 205 (98.1) | 506 (99.2) | 407 (95.3) | 1413 (98.9) | 690 (99.6) | 221 (99.5) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 14 (1.4) | 21 (2.6) | 4 (1.9) | 4 (0.8) | 20 (4.7) | 16 (1.1) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Phenelzine (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.911 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Pheniramine (%) | 0 | 980 (99.8) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1427 (99.9) | 691 (99.7) | 222 (100.0) | 0.837 |

| 1 | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Phenobarbital (%) | 0 | 978 (99.6) | 806 (98.1) | 206 (98.6) | 499 (97.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1408 (98.5) | 686 (99.0) | 219 (98.6) | 0.008 |

| 1 | 4 (0.4) | 16 (1.9) | 3 (1.4) | 11 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 21 (1.5) | 7 (1.0) | 3 (1.4) | ||

| Phentermine (%) | 0 | 968 (98.6) | 820 (99.8) | 208 (99.5) | 510 (100.0) | 424 (99.3) | 1421 (99.4) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.001 |

| 1 | 14 (1.4) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.7) | 8 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Phenylephrine (%) | 0 | 953 (97.0) | 675 (82.1) | 205 (98.1) | 481 (94.3) | 316 (74.0) | 1370 (95.9) | 676 (97.5) | 221 (99.5) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 29 (3.0) | 147 (17.9) | 4 (1.9) | 29 (5.7) | 111 (26.0) | 59 (4.1) | 17 (2.5) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Phenyltoloxamine (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 221 (99.5) | 0.002 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Phenytoin (%) | 0 | 979 (99.7) | 799 (97.2) | 207 (99.0) | 505 (99.0) | 425 (99.5) | 1407 (98.5) | 691 (99.7) | 220 (99.1) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 3 (0.3) | 23 (2.8) | 2 (1.0) | 5 (1.0) | 2 (0.5) | 22 (1.5) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Pramipexole (%) | 0 | 980 (99.8) | 815 (99.1) | 208 (99.5) | 508 (99.6) | 422 (98.8) | 1416 (99.1) | 689 (99.4) | 218 (98.2) | 0.157 |

| 1 | 2 (0.2) | 7 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 5 (1.2) | 13 (0.9) | 4 (0.6) | 4 (1.8) | ||

| Pregabalin (%) | 0 | 964 (98.2) | 799 (97.2) | 203 (97.1) | 497 (97.5) | 409 (95.8) | 1390 (97.3) | 674 (97.3) | 219 (98.6) | 0.307 |

| 1 | 18 (1.8) | 23 (2.8) | 6 (2.9) | 13 (2.5) | 18 (4.2) | 39 (2.7) | 19 (2.7) | 3 (1.4) | ||

| Primidone (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 818 (99.5) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1424 (99.7) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.078 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Promazine (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.734 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Promethazine (%) | 0 | 962 (98.0) | 772 (93.9) | 203 (97.1) | 490 (96.1) | 401 (93.9) | 1389 (97.2) | 677 (97.7) | 218 (98.2) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 20 (2.0) | 50 (6.1) | 6 (2.9) | 20 (3.9) | 26 (6.1) | 40 (2.8) | 16 (2.3) | 4 (1.8) | ||

| Propoxyphene (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 820 (99.8) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 426 (99.8) | 1427 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.713 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Protriptyline (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.911 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Pseudoephedrine (%) | 0 | 967 (98.5) | 816 (99.3) | 207 (99.0) | 502 (98.4) | 421 (98.6) | 1420 (99.4) | 689 (99.4) | 221 (99.5) | 0.192 |

| 1 | 15 (1.5) | 6 (0.7) | 2 (1.0) | 8 (1.6) | 6 (1.4) | 9 (0.6) | 4 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Quetiapine (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 508 (99.6) | 424 (99.3) | 0 (0.0) | 693 (100.0) | 219 (98.6) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.4) | 3 (0.7) | 1429 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.4) | ||

| Quinidine (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.911 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Rasagiline (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.911 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Remifentanil (%) | 0 | 980 (99.8) | 811 (98.7) | 208 (99.5) | 508 (99.6) | 414 (97.0) | 1424 (99.7) | 691 (99.7) | 221 (99.5) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 2 (0.2) | 11 (1.3) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 13 (3.0) | 5 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Riboflavin (%) | 0 | 979 (99.7) | 819 (99.6) | 209 (100.0) | 502 (98.4) | 425 (99.5) | 1424 (99.7) | 689 (99.4) | 222 (100.0) | 0.021 |

| 1 | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (1.6) | 2 (0.5) | 5 (0.3) | 4 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Risperidone (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 819 (99.6) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1427 (99.9) | 0 (0.0) | 220 (99.1) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 693 (100.0) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Rivastigmine (%) | 0 | 979 (99.7) | 821 (99.9) | 208 (99.5) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 691 (99.7) | 222 (100.0) | 0.412 |

| 1 | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Rizatriptan (%) | 0 | 962 (98.0) | 809 (98.4) | 206 (98.6) | 495 (97.1) | 418 (97.9) | 1408 (98.5) | 682 (98.4) | 218 (98.2) | 0.576 |

| 1 | 20 (2.0) | 13 (1.6) | 3 (1.4) | 15 (2.9) | 9 (2.1) | 21 (1.5) | 11 (1.6) | 4 (1.8) | ||

| Ropinirole (%) | 0 | 969 (98.7) | 816 (99.3) | 204 (97.6) | 503 (98.6) | 423 (99.1) | 1408 (98.5) | 684 (98.7) | 218 (98.2) | 0.632 |

| 1 | 13 (1.3) | 6 (0.7) | 5 (2.4) | 7 (1.4) | 4 (0.9) | 21 (1.5) | 9 (1.3) | 4 (1.8) | ||

| Ropivacaine (%) | 0 | 973 (99.1) | 781 (95.0) | 208 (99.5) | 507 (99.4) | 359 (84.1) | 1415 (99.0) | 687 (99.1) | 221 (99.5) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 9 (0.9) | 41 (5.0) | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.6) | 68 (15.9) | 14 (1.0) | 6 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Rufinamide (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 221 (99.5) | 0.002 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Salicylic Acid (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.789 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Scopolamine (%) | 0 | 977 (99.5) | 750 (91.2) | 209 (100.0) | 504 (98.8) | 341 (79.9) | 1424 (99.7) | 685 (98.8) | 221 (99.5) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 5 (0.5) | 72 (8.8) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.2) | 86 (20.1) | 5 (0.3) | 8 (1.2) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Selegiline (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.606 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Sertraline (%) | 0 | 803 (81.8) | 712 (86.6) | 181 (86.6) | 444 (87.1) | 374 (87.6) | 1209 (84.6) | 568 (82.0) | 189 (85.1) | 0.011 |

| 1 | 179 (18.2) | 110 (13.4) | 28 (13.4) | 66 (12.9) | 53 (12.4) | 220 (15.4) | 125 (18.0) | 33 (14.9) | ||

| Sodium Bicarbonate (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 819 (99.6) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 426 (99.8) | 1428 (99.9) | 691 (99.7) | 222 (100.0) | 0.735 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Sufentanil (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.606 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Sumatriptan (%) | 0 | 934 (95.1) | 790 (96.1) | 192 (91.9) | 468 (91.8) | 402 (94.1) | 1371 (95.9) | 675 (97.4) | 210 (94.6) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 48 (4.9) | 32 (3.9) | 17 (8.1) | 42 (8.2) | 25 (5.9) | 58 (4.1) | 18 (2.6) | 12 (5.4) | ||

| Suvorexant (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1425 (99.7) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.146 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Tacrine (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.734 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Tapentadol (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.732 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Tasimelteon (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.606 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Temazepam (%) | 0 | 963 (98.1) | 797 (97.0) | 203 (97.1) | 495 (97.1) | 423 (99.1) | 1383 (96.8) | 668 (96.4) | 216 (97.3) | 0.135 |

| 1 | 19 (1.9) | 25 (3.0) | 6 (2.9) | 15 (2.9) | 4 (0.9) | 46 (3.2) | 25 (3.6) | 6 (2.7) | ||

| Thiamine (%) | 0 | 961 (97.9) | 715 (87.0) | 201 (96.2) | 470 (92.2) | 418 (97.9) | 1343 (94.0) | 666 (96.1) | 212 (95.5) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 21 (2.1) | 107 (13.0) | 8 (3.8) | 40 (7.8) | 9 (2.1) | 86 (6.0) | 27 (3.9) | 10 (4.5) | ||

| Tiagabine (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.719 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Topiramate (%) | 0 | 891 (90.7) | 785 (95.5) | 177 (84.7) | 460 (90.2) | 395 (92.5) | 1308 (91.5) | 645 (93.1) | 189 (85.1) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 91 (9.3) | 37 (4.5) | 32 (15.3) | 50 (9.8) | 32 (7.5) | 121 (8.5) | 48 (6.9) | 33 (14.9) | ||

| Tramadol (%) | 0 | 910 (92.7) | 732 (89.1) | 196 (93.8) | 471 (92.4) | 368 (86.2) | 1304 (91.3) | 649 (93.7) | 204 (91.9) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 72 (7.3) | 90 (10.9) | 13 (6.2) | 39 (7.6) | 59 (13.8) | 125 (8.7) | 44 (6.3) | 18 (8.1) | ||

| Tranylcypromine (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.734 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Trazodone (%) | 0 | 781 (79.5) | 691 (84.1) | 173 (82.8) | 418 (82.0) | 386 (90.4) | 1164 (81.5) | 547 (78.9) | 189 (85.1) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 201 (20.5) | 131 (15.9) | 36 (17.2) | 92 (18.0) | 41 (9.6) | 265 (18.5) | 146 (21.1) | 33 (14.9) | ||

| Triazolam (%) | 0 | 980 (99.8) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1427 (99.9) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.897 |

| 1 | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Trifluoperazine (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.467 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Valbenazine (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 822 (100.0) | 209 (100.0) | 510 (100.0) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.734 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Valproate (%) | 0 | 977 (99.5) | 812 (98.8) | 209 (100.0) | 500 (98.0) | 426 (99.8) | 1420 (99.4) | 690 (99.6) | 221 (99.5) | 0.012 |

| 1 | 5 (0.5) | 10 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (2.0) | 1 (0.2) | 9 (0.6) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Venlafaxine (%) | 0 | 842 (85.7) | 764 (92.9) | 188 (90.0) | 472 (92.5) | 395 (92.5) | 1269 (88.8) | 622 (89.8) | 195 (87.8) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 140 (14.3) | 58 (7.1) | 21 (10.0) | 38 (7.5) | 32 (7.5) | 160 (11.2) | 71 (10.2) | 27 (12.2) | ||

| Vilazodone (%) | 0 | 974 (99.2) | 821 (99.9) | 205 (98.1) | 509 (99.8) | 420 (98.4) | 1423 (99.6) | 690 (99.6) | 221 (99.5) | 0.004 |

| 1 | 8 (0.8) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (1.9) | 1 (0.2) | 7 (1.6) | 6 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Vitamin B6 (%) | 0 | 978 (99.6) | 818 (99.5) | 208 (99.5) | 508 (99.6) | 427 (100.0) | 1427 (99.9) | 691 (99.7) | 221 (99.5) | 0.739 |

| 1 | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.5) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Vortioxetine (%) | 0 | 970 (98.8) | 821 (99.9) | 206 (98.6) | 508 (99.6) | 425 (99.5) | 1425 (99.7) | 691 (99.7) | 220 (99.1) | 0.012 |

| 1 | 12 (1.2) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (1.4) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (0.5) | 4 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Zaleplon (%) | 0 | 981 (99.9) | 820 (99.8) | 208 (99.5) | 508 (99.6) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 691 (99.7) | 220 (99.1) | 0.205 |

| 1 | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.9) | ||

| Ziprasidone (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 821 (99.9) | 208 (99.5) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1429 (100.0) | 693 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 222 (100.0) | ||

| Zolmitriptan (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 822 (100.0) | 208 (99.5) | 508 (99.6) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.155 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Zolpidem (%) | 0 | 908 (92.5) | 734 (89.3) | 195 (93.3) | 467 (91.6) | 401 (93.9) | 1303 (91.2) | 653 (94.2) | 206 (92.8) | 0.016 |

| 1 | 74 (7.5) | 88 (10.7) | 14 (6.7) | 43 (8.4) | 26 (6.1) | 126 (8.8) | 40 (5.8) | 16 (7.2) | ||

| Zonisamide (%) | 0 | 978 (99.6) | 818 (99.5) | 207 (99.0) | 506 (99.2) | 427 (100.0) | 1425 (99.7) | 692 (99.9) | 221 (99.5) | 0.388 |

| 1 | 4 (0.4) | 4 (0.5) | 2 (1.0) | 4 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Doxazosin (%) | 0 | 980 (99.8) | 819 (99.6) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 425 (99.5) | 1424 (99.7) | 693 (100.0) | 222 (100.0) | 0.676 |

| 1 | 2 (0.2) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 5 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Prazosin (%) | 0 | 882 (89.8) | 800 (97.3) | 184 (88.0) | 463 (90.8) | 408 (95.6) | 1276 (89.3) | 642 (92.6) | 205 (92.3) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 100 (10.2) | 22 (2.7) | 25 (12.0) | 47 (9.2) | 19 (4.4) | 153 (10.7) | 51 (7.4) | 17 (7.7) | ||

| Terazosin (%) | 0 | 980 (99.8) | 815 (99.1) | 208 (99.5) | 509 (99.8) | 426 (99.8) | 1428 (99.9) | 690 (99.6) | 222 (100.0) | 0.081 |

| 1 | 2 (0.2) | 7 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

Appendix D

| Drug Group | # of Patients | # of Months of Follow Up | # of Events | # of Patients Switched (%) | Average # of ED Visits at the First Month of Follow Up | Average # of ED Visits at the Last Month of Follow Up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole | 982 | 9.76 | 38 | 115 (12) | 0.47 | 0.29 |

| Haloperidol | 822 | 4.38 | 28 | 65 (8) | 1.18 | 0.63 |

| Lurasidone | 209 | 7.94 | 0 | 30 (14) | 0.44 | 0.42 |

| Olanzapine | 510 | 7.05 | 22 | 79 (15) | 0.68 | 0.47 |

| Perphenazine | 427 | 5.2 | 3 | 14 (3) | 0.57 | 0.42 |

| Quetiapine | 1429 | 9.04 | 38 | 166 (12) | 0.55 | 0.43 |

| Risperidone | 693 | 9 | 17 | 127 (18) | 0.54 | 0.37 |

| Ziprasidone | 222 | 8.02 | 11 | 23 (10) | 0.49 | 0.39 |

References

- Byers, A.L.; Covinsky, K.E.; Neylan, T.C.; Yaffe, K. Chronicity of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Risk of Disability in Older Persons. JAMA Psychiatry 2014, 71, 540–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalev, A.; Liberzon, I.; Marmar, C. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2459–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Summary of the clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. Am. Psychol. 2019, 74, 596–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, G.D.M.; Zanatta, F.B.; Ziegelmann, P.K.; Barros, A.J.S.; Mello, C.F. Pharmacological treatments for adults with post-traumatic stress disorder: A network meta-analysis of comparative efficacy and acceptability. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 130, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardis, D.D.; Marini, S.; Serroni, N.; Iasevoli, F.; Tomasetti, C.; de Bartolomeis, A.; Mazza, M.; Tempesta, D.; Valchera, A.; Fornaro, M.; et al. Targeting the noradrenergic system in posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prazosin trials. Curr. Drug Targets 2015, 16, 1094–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.C.; Norra, C.; Wetter, T.C. Sleep Disturbances and Suicidality in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: An Overview of the Literature. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskind, M.A.; Peskind, E.R.; Chow, B.; Harris, C.; Davis-Karim, A.; Holmes, H.A.; Hart, K.L.; McFall, M.; Mellman, T.A.; Reist, C.; et al. Trial of Prazosin for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Military Veterans. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 507–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nock, M.K.; Hwang, I.; Sampson, N.A.; Kessler, R.C. Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Mol. Psychiatry 2009, 15, 868–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisco, B.E.; Marx, B.P.; Holowka, D.W.; Vasterling, J.J.; Han, S.C.; Chen, M.S.; Gradus, J.L.; Nock, M.K.; Rosen, R.C.; Keane, T.M. Traumatic Brain Injury, PTSD, and Current Suicidal Ideation Among Iraq and Afghanistan U.S. Veterans. J. Trauma. Stress 2014, 27, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.E.; Campbell-Sills, L.; Kessler, R.C.; Sun, X.; Heeringa, S.G.; Nock, M.K.; Ursano, R.J.; Jain, S.; Stein, M.B. Pre-deployment insomnia is associated with post-deployment post-traumatic stress disorder and suicidal ideation in US Army soldiers. Sleep 2019, 42, zsy229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krysinska, K.; Lester, D. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Suicide Risk: A Systematic Review. Arch. Suicide Res. 2010, 14, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeardMann, C.A.; Powell, T.M.; Smith, T.C.; Bell, M.R.; Smith, B.; Boyko, E.J.; Hooper, T.I.; Gackstetter, G.D.; Ghamsary, M.; Hoge, C.W. Risk Factors Associated With Suicide in Current and Former US Military Personnel. JAMA 2013, 310, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, P.; Guo, X.; Qi, X.; Matharu, M.; Patel, R.; Sakolsky, D.; Kirisci, L.; Silverstein, J.C.; Wang, L. Prediction of Suicide-Related Events by Analyzing Electronic Medical Records from PTSD Patients with Bipolar Disorder. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohen, I.; Lester, P.E.; Lam, S. Antipsychotic treatments for the elderly: Efficacy and safety of aripiprazole. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2010, 6, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muench, J.; Hamer, A.M. Adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. Am. Fam. Phys. 2010, 81, 617–622. [Google Scholar]

- Dold, M.; Samara, M.T.; Li, C.; Tardy, M.; Leucht, S. Haloperidol versus first-generation antipsychotics for the treatment of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 1, CD009831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, U.; Carmassi, C.; Cosci, F.; De Cori, D.; Di Nicola, M.; Ferrari, S.; Poloni, N.; Tarricone, I.; Fiorillo, A. Role and clinical implications of atypical antipsychotics in anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, trauma-related, and somatic symptom disorders. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 31, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeman, P. Atypical Antipsychotics: Mechanism of Action. Can. J. Psychiatry 2002, 47, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doménech-Matamoros, P. Influence of the use of atypical antipsychotics in metabolic syndrome. Rev. Espanola Sanid. Penit. 2020, 22, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saguil, A. Psychological and Pharmacologic Treatments for Adults with PTSD. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 99, 577–583. [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal, G.; Hamner, M.B.; Cañive, J.M.; Robert, S.; Calais, L.A.; Durklaski, V.; Zhai, Y.; Qualls, C. Efficacy of Quetiapine Monotherapy in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Am. J. Psychiatry 2016, 173, 1205–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, P.; Suliman, S.; Ganesan, K.; Seedat, S.; Stein, D.J. Olanzapine monotherapy in posttraumatic stress disorder: Efficacy in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2012, 27, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suissa, S. Immortal Time Bias in Pharmacoepidemiology. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 167, 492–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernán, M.A.; Robins, J.M. Using Big Data to Emulate a Target Trial When a Randomized Trial Is Not Available: Table 1. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 183, 758–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suissa, S. Immortal time bias in observational studies of drug effects. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2007, 16, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danaei, G.; Rodríguez, L.A.G.; Cantero, O.F.; Logan, R.W.; Hernán, M.A. Electronic medical records can be used to emulate target trials of sustained treatment strategies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 96, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanderson, M.; Bulloch, A.G.; Wang, J.; Williams, K.G.; Williamson, T.; Patten, S.B. Predicting death by suicide following an emergency department visit for parasuicide with administrative health care system data and machine learning. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 20, 100281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossum, G.; Drake, F.L., Jr. Python Reference Manual; Centrum voor Wiskunde en Informatica: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. Base SAS 9.4 Procedures Guide; SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, K.X. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. Lond. Edinb. Dublin Philos. Mag. J. Sci. 1900, 50, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Student. The probable error of a mean. Biometrika 1908, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehret, M. Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: Focus on pharmacotherapy. Ment. Health Clin. 2019, 9, 373–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, A.R.; Maglione, M.; Bagley, S.; Suttorp, M.; Hu, J.H.; Ewing, B.; Wang, Z.; Timmer, M.; Sultzer, D.; Shekelle, P.G. Efficacy and comparative effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic medications for off-label uses in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2011, 306, 1359–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Cha, D.S.; Kim, R.D.; Mansur, R.B. A review of FDA-approved treatment options in bipolar depression. CNS Spectr. 2013, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamner, M.B.; Hernandez-Tejada, M.A.; Zuschlag, Z.D.; Agbor-Tabi, D.; Huber, M.; Wang, Z. Ziprasidone Augmentation of SSRI Antidepressants in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study of Augmentation Therapy. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 39, 153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sher, L.; Kahn, R.S. Suicide in Schizophrenia: An Educational Overview. Medicina 2019, 55, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, D.; Petersen, T.; Amado, S.; Kuperberg, M.; Dufour, S.; Rakhilin, M.; Hall, N.E.; Kinrys, G.; Desrosiers, A.; Deckersbach, T.; et al. An evaluation of suicidal risk in bipolar patients with comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 266, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; White, J.; Turley, R.; Slater, T.; Morgan, H.; Strange, H.; Scourfield, J. Comparison of suicidal ideation, suicide attempt and suicide in children and young people in care and non-care populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 82, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Level | Aripiprazole | Haloperidol | Lurasidone | Olanzapine | Perphenazine | Quetiapine | Risperidone | Ziprasidone | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of Patients | 982 | 822 | 209 | 510 | 427 | 1429 | 693 | 222 | - | |

| Age (mean (SD)) | 38.13 (16.18) | 46.48 (17.12) | 37.71 (12.15) | 42.64 (15.83) | 42.71 (13.56) | 40.31 (14.52) | 38.39 (17.66) | 37.24 (12.88) | <0.001 | |

| Male (%) | 245 (24.9) | 289 (35.2) | 33 (15.8) | 186 (36.5) | 99 (23.2) | 473 (33.1) | 261 (37.7) | 45 (20.3) | <0.001 | |

| # of ED visits in previous 3 months (mean (SD)) | 0.47 (1.26) | 1.18 (2.11) | 0.44 (0.90) | 0.68 (1.31) | 0.57 (1.06) | 0.55 (1.08) | 0.54 (1.20) | 0.49 (0.88) | <0.001 | |

| Category 1 * (%) | 0 | 876 (89.2) | 549 (66.8) | 189 (90.4) | 421 (82.5) | 390 (91.3) | 1156 (80.9) | 584 (84.3) | 195 (87.8) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 106 (10.8) | 273 (33.2) | 20 (9.6) | 89 (17.5) | 37 (8.7) | 273 (19.1) | 109 (15.7) | 27 (12.2) | ||

| Category 2 * (%) | 0 | 957 (97.5) | 788 (95.9) | 201 (96.2) | 482 (94.5) | 423 (99.1) | 1393 (97.5) | 647 (93.4) | 210 (94.6) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 25 (2.5) | 34 (4.1) | 8 (3.8) | 28 (5.5) | 4 (0.9) | 36 (2.5) | 46 (6.6) | 12 (5.4) | ||

| Category 3 * (%) | 0 | 408 (41.5) | 187 (22.7) | 104 (49.8) | 176 (34.5) | 137 (32.1) | 540 (37.8) | 284 (41.0) | 93 (41.9) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 574 (58.5) | 635 (77.3) | 105 (50.2) | 334 (65.5) | 290 (67.9) | 889 (62.2) | 409 (59.0) | 129 (58.1) | ||

| Category 4 * (%) | 0 | 962 (98.0) | 792 (96.4) | 209 (100.0) | 477 (93.5) | 425 (99.5) | 1400 (98.0) | 653 (94.2) | 216 (97.3) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 20 (2.0) | 30 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 33 (6.5) | 2 (0.5) | 29 (2.0) | 40 (5.8) | 6 (2.7) | ||

| Category 5 * (%) | 0 | 671 (68.3) | 372 (45.3) | 137 (65.6) | 287 (56.3) | 204 (47.8) | 877 (61.4) | 470 (67.8) | 155 (69.8) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 311 (31.7) | 450 (54.7) | 72 (34.4) | 223 (43.7) | 223 (52.2) | 552 (38.6) | 223 (32.2) | 67 (30.2) | ||

| Category 6 * (%) | 0 | 951 (96.8) | 781 (95.0) | 202 (96.7) | 489 (95.9) | 419 (98.1) | 1385 (96.9) | 670 (96.7) | 214 (96.4) | 0.158 |

| 1 | 31 (3.2) | 41 (5.0) | 7 (3.3) | 21 (4.1) | 8 (1.9) | 44 (3.1) | 23 (3.3) | 8 (3.6) | ||

| Category 7 * (%) | 0 | 982 (100.0) | 821 (99.9) | 209 (100.0) | 509 (99.8) | 427 (100.0) | 1428 (99.9) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.881 |

| 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Category 8 * (%) | 0 | 980 (99.8) | 821 (99.9) | 208 (99.5) | 509 (99.8) | 425 (99.5) | 1424 (99.7) | 692 (99.9) | 222 (100.0) | 0.842 |

| 1 | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.5) | 5 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Category 9 * (%) | 0 | 955 (97.3) | 787 (95.7) | 203 (97.1) | 494 (96.9) | 417 (97.7) | 1383 (96.8) | 679 (98.0) | 216 (97.3) | 0.343 |

| 1 | 27 (2.7) | 35 (4.3) | 6 (2.9) | 16 (3.1) | 10 (2.3) | 46 (3.2) | 14 (2.0) | 6 (2.7) | ||

| Category 10 * (%) | 0 | 964 (98.2) | 753 (91.6) | 207 (99.0) | 475 (93.1) | 422 (98.8) | 1383 (96.8) | 663 (95.7) | 214 (96.4) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 18 (1.8) | 69 (8.4) | 2 (1.0) | 35 (6.9) | 5 (1.2) | 46 (3.2) | 30 (4.3) | 8 (3.6) | ||

| Category 11 * (%) | 0 | 905 (92.2) | 764 (92.9) | 197 (94.3) | 466 (91.4) | 414 (97.0) | 1366 (95.6) | 611 (88.2) | 212 (95.5) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 77 (7.8) | 58 (7.1) | 12 (5.7) | 44 (8.6) | 13 (3.0) | 63 (4.4) | 82 (11.8) | 10 (4.5) | ||

| Category 12 * (%) | 0 | 979 (99.7) | 816 (99.3) | 209 (100.0) | 506 (99.2) | 426 (99.8) | 1423 (99.6) | 687 (99.1) | 220 (99.1) | 0.492 |

| 1 | 3 (0.3) | 6 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (0.8) | 1 (0.2) | 6 (0.4) | 6 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) |

| Drug Pair | Hazard Ratio * 95% Confidence Interval (Adjusting Comorbidities) | p Value | Q Value ** | Hazard Ratio 95% Confidence Interval (Adjusting Comorbidities + Concomitant Drugs) | p Value | Q Value ** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole vs. Haloperidol | 0.73 [0.437, 1.22] | 0.233 | 0.2610 | 0.44 [0.25, 0.79] | 0.0062 | 0.0154 |

| Aripiprazole vs. Lurasidone | 15.4 [8.65, 27.5] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 | 43.25 [10.65, 175.56] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 |

| Aripiprazole vs. Olanzapine | 0.70 [0.421, 1.15] | 0.1599 | 0.2356 | 0.75 [0.41, 1.39] | 0.3594 | 0.4193 |

| Aripiprazole vs. Perphenazine | 2.27 [0.847, 6.06] | 0.1034 | 0.1756 | 1.09 [0.49, 2.44] | 0.8319 | 0.8627 |

| Aripiprazole vs. Quetiapine | 1.41 [0.919, 2.17] | 0.1159 | 0.1803 | 2.05 [1.28, 3.28] | 0.0028 | 0.0087 |

| Aripiprazole vs. Risperidone | 1.37 [0.846, 2.22] | 0.2002 | 0.2372 | 2.20 [1.21, 4.01] | 0.0101 | 0.0202 |

| Aripiprazole vs. Ziprasidone | 0.68 [0.373, 1.23] | 0.2033 | 0.2372 | 0.98 [0.52, 1.85] | 0.9542 | 0.9542 |

| Haloperidol vs. Lurasidone | 23.2 [7.68, 70.2] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 | 52.20 [14.97, 182.18] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 |

| Haloperidol vs. Olanzapine | 1.05 [0.547, 2.00] | 0.8938 | 0.9269 | 1.86 [1.02, 3.42] | 0.0447 | 0.0834 |

| Haloperidol vs. Perphenazine | 4.25 [1.23, 14.7] | 0.0219 | 0.0472 | 1.97 [0.80, 4.84] | 0.1399 | 0.1996 |

| Haloperidol vs. Quetiapine | 1.73 [1.038, 2.87] | 0.0354 | 0.0661 | 1.62 [0.86, 3.05] | 0.1321 | 0.1996 |

| Haloperidol vs. Risperidone | 1.72 [0.89, 3.31] | 0.1066 | 0.1756 | 3.20 [1.47, 6.97] | 0.0033 | 0.0092 |

| Haloperidol vs. Ziprasidone | 0.590 [0.27, 1.30] | 0.1897 | 0.2372 | 1.81 [0.82, 3.98] | 0.1426 | 0.1996 |

| Lurasidone vs. Olanzapine | 0.057 [0.031, 0.10] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 | 0.01 [0.002, 0.04] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 |

| Lurasidone vs. Perphenazine | 0.13 [0.064, 0.28] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 | 0.17 [0.01, 2.41] | 0.1904 | 0.2423 |

| Lurasidone vs. Quetiapine | 0.12 [0.077, 0.18] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 | 0.05 [0.02, 0.16] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 |

| Lurasidone vs. Risperidone | 0.13 [0.073, 0.25] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 | 0.24 [0.14, 0.40] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 |

| Lurasidone vs. Ziprasidone | 0.065 [0.033, 0.13] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 | 0.05 [0.02, 0.11] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 |

| Olanzapine vs. Perphenazine | 2.945 [1.15, 7.58] | 0.025 | 0.0500 | 0.66 [0.30, 1.43] | 0.2901 | 0.3532 |

| Olanzapine vs. Quetiapine | 1.813 [1.104, 2.98] | 0.0188 | 0.0439 | 1.95 [1.20, 3.15] | 0.0066 | 0.0154 |

| Olanzapine vs. Risperidone | 2.153 [1.15, 4.02] | 0.0161 | 0.0439 | 2.35 [1.41, 3.94] | 0.0011 | 0.0039 |

| Olanzapine vs. Ziprasidone | 0.882 [0.43, 1.80] | 0.7296 | 0.7857 | 1.61 [0.83, 3.11] | 0.1572 | 0.2096 |

| Perphenazine vs. Quetiapine | 0.541 [0.22, 1.33] | 0.1801 | 0.2372 | 1.22 [0.48, 3.11] | 0.677 | 0.7582 |

| Perphenazine vs. Risperidone | 0.506 [0.18, 1.40] | 0.188 | 0.2372 | 2.55 [1.27, 5.14] | 0.0087 | 0.0187 |

| Perphenazine vs. Ziprasidone | 0.315 [0.12, 0.82] | 0.0176 | 0.0439 | 1.93 [0.81, 4.59] | 0.1358 | 0.1996 |

| Quetiapine vs. Risperidone | 1.024 [0.60, 1.75] | 0.9286 | 0.9286 | 1.08 [0.64, 1.80] | 0.7762 | 0.8359 |

| Quetiapine vs. Ziprasidone | 0.451 [0.24, 0.84] | 0.0118 | 0.0367 | 0.59 [0.32, 1.08] | 0.0866 | 0.1516 |

| Risperidone vs. Ziprasidone | 0.432 [0.23, 0.83] | 0.0118 | 0.0367 | 0.30 [0.17, 0.52] | <0.0001 | <0.0004 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Delapaz, N.R.; Hor, W.K.; Gilbert, M.; La, A.D.; Liang, F.; Fan, P.; Qi, X.; Guo, X.; Ying, J.; Sakolsky, D.; et al. An Emulation of Randomized Trials of Administrating Antipsychotics in PTSD Patients for Outcomes of Suicide-Related Events. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11030178

Delapaz NR, Hor WK, Gilbert M, La AD, Liang F, Fan P, Qi X, Guo X, Ying J, Sakolsky D, et al. An Emulation of Randomized Trials of Administrating Antipsychotics in PTSD Patients for Outcomes of Suicide-Related Events. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021; 11(3):178. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11030178

Chicago/Turabian StyleDelapaz, Noah R., William K. Hor, Michael Gilbert, Andrew D. La, Feiran Liang, Peihao Fan, Xiguang Qi, Xiaojiang Guo, Jian Ying, Dara Sakolsky, and et al. 2021. "An Emulation of Randomized Trials of Administrating Antipsychotics in PTSD Patients for Outcomes of Suicide-Related Events" Journal of Personalized Medicine 11, no. 3: 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11030178

APA StyleDelapaz, N. R., Hor, W. K., Gilbert, M., La, A. D., Liang, F., Fan, P., Qi, X., Guo, X., Ying, J., Sakolsky, D., Kirisci, L., Silverstein, J. C., & Wang, L. (2021). An Emulation of Randomized Trials of Administrating Antipsychotics in PTSD Patients for Outcomes of Suicide-Related Events. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 11(3), 178. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm11030178