Co-Designing an Integrated Care Network with People Living with Parkinson’s Disease: A Heterogeneous Social Network of People, Resources and Technologies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

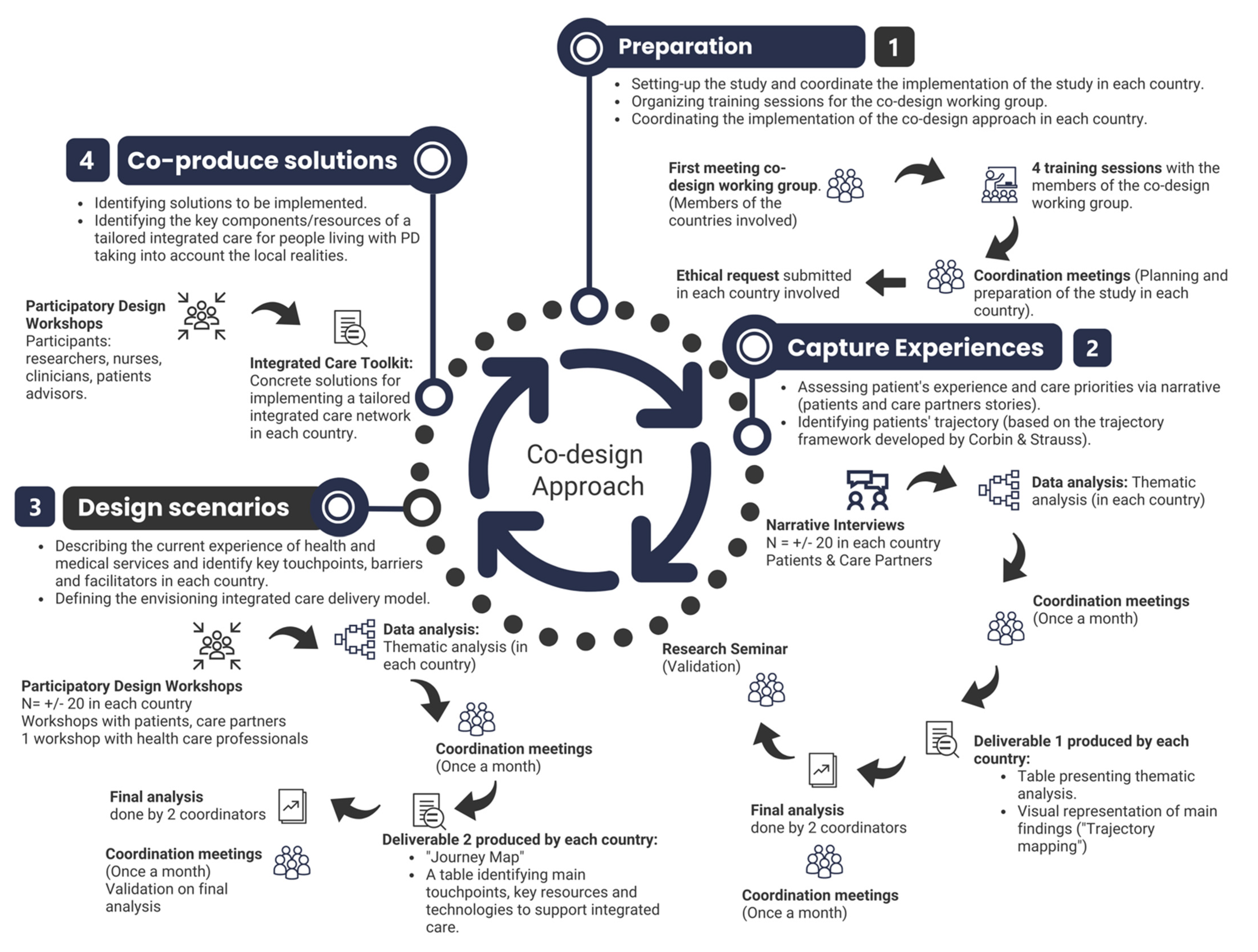

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Context of the Study: The iCARE-PD Project

2.2. Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

2.3.1. Pre-Workshop Tasks for PwP and Their CP

2.3.2. Workshop for PwP and Their CP

2.3.3. Pre-Workshop and Workshop with HCP

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Activity 1: Exploring with PwP & HCP the Actual Network of Care

3.1.1. Process of Diagnosis and Diagnosis Announcement

P5: Well, I think, of course the main event was the diagnosis, […], which was three years ago. But I think I knew, like I knew something was wrong before that, I didn’t know… I had a lot of pain, but I was almost relieved when, I should say, I just, once I knew what the diagnosis was, and I knew I would learn how to cope with it somehow.

P8: to get the diagnosis, it took a while. But I mean that’s not, I know it’s hard to diagnose Parkinson’s, and because I don’t have a family history for it, because I was female, I was young. The typical symptoms, I didn’t fit everything. And, I think it was just my situation. But also, not being taken seriously [by] the two of the neurologists. And that’s a barrier, but I think that, like I said, I think that’s a lot of women in this country.

P5: And I certainly have the great treatment and people looking after me for all my Parkinson’s symptoms, so the touchpoints for me were, of course, the first touchpoint was the neurological clinic.

P1: Okay, well I can tell you that I was not geared or pointed towards any community services or any information of any kind for Parkinson’s.

P1: I finally found what I found by myself, and I didn’t find any support, actually. The support was very poor, I have to admit, with everything you hear on the news, and anything else, about the research and everything else about Parkinson’s.

P8: I believe that, even when I go to the clinic, you know, you’re just giv[en] a sheet saying this is the symptoms. Like […], there’s no place to direct you, and you have to do your homework on your own. I am, I don’t know how other people find that, but that’s been my, my experience.

P6: Yeah then the same thing with the group that started that in winter. And we joined the group there, the Parkinson’s group, and it was just tremendous. And that’s when we got most of our information, because when he was diagnosed, they just left us on our own, and we were just, you know.

P2: One thing I did do after the diagnosis, but not too long after, was going to a physiotherapist who was recommended by a friend of mine to do some, well a series of exercises which she’d be trained on.

HCP2: Yeah, I mean, I think one of our main struggles is how […] we can be appealing for general practitioners to care for people with Parkinson’s. That’s a barrier, but in a sense, […] could be a facilitator. […] But definitely, I think both P5 and P1, you know, we end up seeing ourselves being the GPs of our patients, which also shouldn’t happen, so how you strike this balance and make family doctors more at ease of managing problems that do happen let’s say in the geriatric population, but not necessarily specific of Parkinson’s, and so, in a way, but they could also manage those problems, for example.

3.1.2. Impact of PD on Work Life, Social Activities and Trips

HCP2: I think I mentioned what would happen if she would change schools for example and she would practice without a place. That was one aspect and then um sure I’m you want to talk about barriers, facilitators but that was something that occurred to me in terms of a teacher that could all of a sudden have to teach in another school, another place, and so how that would change her care, that was one.

P3: The idea is I ended up stopping working voluntarily because I was losing power on one side, and I was doing physical work, before somebody gets hurt, I decided to take myself out of the job.

P5: I think, you know, people faced with early on in their Parkinson’s they wanna just, you know, they the initial reaction I think a lot of people have is just keep plugging away and keep everything as normal as possible but is that really in their best interest, but helping them work through that problem, there’s definitely a lack of resources, I think, to help them work through that specific issue.

HCP4: One of the things I’m truly interested in if she’s very young, she has a full-time job, very demanding in elementary school. So, for me, education really with respect to why is she having such terrible fatigue because we really want to happen to her, with how young she is, is to keep her active and keep her functioning higher for longer. So, for me, education is really key with understanding what is going on in the sleep. What’s going on with fatigue, can we better manage that to actually address potential issues as well when people aren’t sleeping well and that increases their risk for having, you know, other problems and that emotional field. So, for me it’s the education on that level is where I would like to see some input.

CP3: Yeah and to be honest, P3 isn’t at a point with the illness where we’ve done much in this, along these lines, but I would imagine that it would be great if there was a focal point somewhere and you can go and you can ask “well, what physiotherapy practices in [name of city], specialized in…?”. We found that out through word of mouth. What about speech? I don’t know if some Parkinson’s patients that want to access speech patho or speech therapist, massage therapist, like it’s all, at least it has been for us, and maybe we haven’t found the key yet, the keyhole in the door. But as we try to find those supports, we kind of starting all over all the time. And we ask a friend like a physio “Who do you know that has specialized in Parkinson’s?”. And then you go to the physio you and “what about massage therapy and who do you know?” [P2 nods]. It’s just not as connected as it should be in my view.

3.1.3. Treatment Plan or Changes in the Treatment

P7: Oh, I think the first one would have been appropriate medication and treatment for my Parkinson’s symptoms, which made a huge difference […] I was able to do more physical and social activities once I got on the medication. I kind of didn’t want to do it for quite some time. I thought I could manage it myself but it just came to a point where I realized that I did need some extra help. So that made a huge difference for me.

HCP survey response: LHIN [Local Health Integration Network] is limited in what they can provide due to budget cuts and can’t offer the home health support they would benefit from. The cost of equipment in the home is high and they may not be able to afford all that is suggested to them to improve quality of life and prevent falls.

3.1.4. ON/OFF Episodes or Communication Challenges

P8: The other one I did was, like, my progression with Parkinson’s has been a little hard, especially […] ‘cause I’m having communication problems as you can tell [chuckles], so I’m trying to find the right words and that, and my speech has changed. It’s a little lower. Those are the challenges. The communication has been a big change in my new symptoms.

P8: Well, I’m still waiting […] for a speech therapist referral. It’s been since April so I figured I’m gonna call back the clinic, to figure out why I haven’t gotten one yet.

P5: one of the barriers that immediately comes up is small-town Canada and how people in Canada access specialized services so I think that really, that unfortunately in a lot of places, that’s just not possible because there aren’t any specialized services in the smaller towns and especially if you’re thinking about, you know, physiotherapy or those types of things where the local physiotherapist might not have seen very many Parkinson’s patients, but I think that the idea that maybe the most practical for them is to try to access local, whatever the resources are locally, even if they’re not super specialized.

3.1.5. Stronger Symptoms, Access to Home Care or Medical Equipment

P3: Specifically, here is to start thinking about an assisted living-like situation. How long are they going to be in their home? How long are they going to be able to negotiate stairs, etc. […]. So with falls or near falls that have happened. There’s only so much that we can do with this impaired balance and somebody who’s had Parkinson’s for a long time, so I think it’s really important to start thinking about this and yes, we can organize […] mediated help at home.

P1: So, the example that I used beforehand was contacting the local [name of resource centre] to get a caseworker involved and to do a home assessment to assess the needs in the home and provide access to local resources, have an OT[Occupational Therapy] assessment come in, put things in, you know, like grab bars, assess the needs in the home, prevent falls, link them to local resources in [name of rural area] since they live an hour away from [name of urban centre], so we’re not quite as aware of them. That was the example I used for the life event with the [name of resource centre].

HCP1: So, community resources would be, having some home care coming in, using respite if needed so you don’t have that caregiver fatigue for his wife, as they’re elderly. And then what was the other part, sorry I can’t see the full– so the respite, the home care, any extra means that they might need in [name of rural area] like the [name of food delivery service] and sometimes the [name of resource centre] is more aware of those local things than we are in [name of urban centre].

P3: low-cost physiotherapists, especially, you know, they charge a higher rate than normal therapy which is, fair enough, with a specialist. But it’s certainly a barrier for some. […] Well I think I put down domestic support as a segue into issues of affordability for a lot of those supports.

HCP1: They contact the [name of health care service] to get some supports in the home—[name of health care service] is limited in what they can provide due to budget cuts and can’t offer the home health support they would benefit from—The cost of equipment in the home is high and they may not be able to afford all that is suggested to them to improve QoL and prevent falls.

P1: At this moment, I do not have problems with transportation, like, I still drive. I am steady enough for that … but eventually that’s not gonna work.

P3: I would love to have a social worker be at hand that can help guide them in the right direction. P5 remembers the period where we had a social worker in the clinic that was just a godsend [with] Huntington’s people or difficult cases. We would pick up the phone and they would, an hour later, they’d be connected with our patient, it was just awesome. It should be the way it should be so that we don’t have to do the work, but we can direct people and hook them up with social workers or other facilitators.

3.1.6. Hospitalization Episodes and Rehabilitation Time

CP6: That’s the thing, if we hadn’t been at the hospital, we would not have had all of those. It’s just because that’s the hospital that organized it, because they didn’t want him to go home but they wanted him to go to a special place for rehabilitation. Interviewer: Ah, okay, I understand. […] So, that’s why they organized it. I don’t think it would have been organized for just Parkinson’s, but I don’t know. I’m not sure, maybe yes, maybe no, I don’t know, but they were very helpful.

3.1.7. Journey with PD

3.1.8. Various Distributed Local Networks Enrolled over Time

3.1.9. A Medically Oriented Care Network

P3: This may be a little bit of a danger focusing too much on the Parkinson’s side and I mean there’s lots of people who need home care or some kind of home care for, you know for the whole Alzheimer’s issue for example. I mean there are worse things supposed to happen with Parkinson’s. So I guess you want to separate out what you want the specialized for the Parkinson’s and what’s much more generic should be existing.

3.2. Activity 2: Envisioning Integrated Care Delivery

3.2.1. Networks Interconnected (Personal, Care and Community Network) and Key Actors Such as Family Doctors, Pharmacists, Patients’ Organizations

P3: What would be attractive to me would be some combination of support group and activity. I never became involved, but I’ve got a friend that does, in [name of city] there was some group and they do boxing and dancing.

P2: Dancing yes.

P3: It’s mainly people with Parkinson’s but not just people with Parkinson’s so. It’s just not a support group where people sit in a circle and talk about their problems [CP3, P2 and P1 chuckle]. It brings people together in an activity and then people are informally going to say “Geez my medication isn’t working well this week” or something else.

P2: Yeah. My family doctor has recommended that I go to that dance group.

CP3: I think one of our main struggles is how, you know, we can, be appealing for general practitioners to care for people with Parkinson’s. That’s a barrier, but in a sense, a potential could be a facilitator. But definitely, also a challenge because GPs do see– actually I think we have that feedback already with the [iCARE-PD project] that GPs see a whole gamut of patients and PD alerts are our main focus of practice… it’s a grain of sand in their ocean of patients [chuckles]. But definitely, I think both P5 and P1, you know, we end up seeing ourselves being the GPs of our patients, which also shouldn’t happen, so how you strike this balance and make family doctors more at ease of managing problems that do happen let’s say in the geriatric population, but not necessarily specific of Parkinson’s, and so, in a way, but they could also manage those problems for example.

CP5: So, I guess maybe one of the keys, as P3 was saying, not every patient was saying, not every patient needs all of these services, but I do think if you look at our red boxes, every patient with Parkinson’s, I feel an essential need is a general practitioner. For many patients in smaller communities that’s still unfortunately easier said than done. But I think that’s critical. This is not a condition that is going to get better and is going to get worse and we know all the non-motor things, definitely having the family doctor involved early and feeling more comfortable and knowing the patient can really make a big difference to how the patients are doing, because of, you know, treating their depression and really having a really strong family doctor can be a real key. And again, I think with our Canadian health care system is something we need to make sure is a real part of this process.

P4: so, for me virtual reality has opened up access to expertise and, you know, having resources that you wouldn’t typically have, for me that would be a big bonus. Although saying that I live in [name of rural area] and can’t do virtual reality from my house since we have terrible Wi-Fi reception. So, it opens up in that avenue, but if you have terrible Wi-Fi, then there’s a limitation and a barrier to that.

P5: how am I ever going to know who’s the physiotherapist that’s within five kilometres of our patient who lives in a small town somewhere in Canada? There’s just zero chance I know that and then who is going to help us figure that out? And I think this is where technology is the only solution. Even in [name of city] we can’t keep a running database of all the physiotherapists, let alone the social workers, let alone the occupational therapists, so I think we have to engage technology to help us come up with solutions for this because for 15–20 years I’ve tried to keep a list of these types of things and it doesn’t work.

3.2.2. OPP: Single Point of Contact and Navigation Tools

P7: Having the ability to contact someone to get some information if I’m not able to find it myself.

HCP3: I think a wonderful model would be if there’s a nurse coordinator who interacts with the patient, and she identifies four things that should be done: education, physiotherapy, maybe day programs or whatever. So, she fills out four forms for pharmacy, optimization of drugs.

HCP2: [is] key you know, building this network of resources by having ways to obtain that information, in a certain geographical area, but I would say [name of rural area] would be one, and it’s not that far from [urban centre] and we receive patients from that area. And of course, the challenge is not only how we identify them, but actually maintain that tie-in. So iCARE finder resource that allow us to help these patients navigate whatever resources are available. […] And so, I guess that’s one potential facilitator, but it’s definitely challenging but then, the likelihood of having resources in [rural area] I think it’s less, at least, not in terms of the sheer number but also that the degree of expertise in Parkinson’s disease, for example.

3.2.3. Key Intermediaries or Mediators: Specialized Nurse, Advisory Board, Information Brokers, Programs Orientation, Specific eHealth Technologies Improving Communication with HCP

P2: it might become an old-fashioned idea, but I do think patients, they really cherish the physical patient-physician relationship. A lot could change but definitely having these direct interactions I think it’s very important.

CP4: So for me, I would like to see the nurse coordinator as P1 is saying, to then spread out and bring out a multidisciplinary team on board depending on where that person is on their journey. […] I’ve been working for a while and a lot of times the nurse coordinator was a team coordinator that would link up with the other professionals in a said team, and whatever that team is. Right, so that’s looking probably at health care in the past, where you had a team, part of a movement disorder clinic. Whether that’s in-person or virtual.

P2: I think a lot of it has already been said, but perhaps I like the idea of the curation of how can we help the patient navigate in the wealth of information and I do agree that information is key but it can also be toxic in a way. And so, what’s the role of we health care professionals in helping to navigate that wealth of information?

P2: I think the idea, we had that idea when we created the advisory board for the [name of network], but, of course, that could be expanded in almost like a forum or, you know, create times where you can actually brainstorm with patients and CP of how they seek care, right? And so, what P3 is saying, expanding this idea of a patient advocate or a patient advisory board, right, and, but be part of, on a regular, I guess, be part of the structure of the care delivery model, right, where there’s a more regular interaction with patients and CP.

P3: Depending on, well ideally, I think it would be nice to have the person in the clinic, but it doesn’t have to be. If I had someone in [name rural area], who I can call because I know he or she is a social worker who’s doing a great job with the community members, he or she does not have to be at the [name of facilities in urban centre]. […] I don’t think the social worker has to be involved for every person, but we should have access to that menu option as well is what I’m trying to say. […] it’s very much like a drop-down menu where you pick what is the best match for what the person needs in the near future.

CP3: And whether it’s a spouse or it’s another care, somebody who is stepping up to play a role, like a child, an adult child or. Yes, obviously I think our, the support, support system or ideal care system should include, you know, a family orientation. If a family, if that’s what the, you know, the individuals choose.

P3: I just find telephone communication is not effective. There has to be another way and I think virtual interactions, which is then difficult to organize because there has to be a booking, there has to be a Zoom link, you have to be online, and that in itself take a lot of time of admin people or doctors or nurses. I have absolutely no idea how to solve this. The better we are in helping people with an integrated care approach, it’s so time and resource consuming. I don’t have anything productive to add is what I’m trying to say.

P1: So, in terms of technology, I would say that telemedicine has been really good at having easier access to the physicians to get advice and just those virtual appointments have been really nice especially for those, was trouble with mobility or access to rides to get to appointments and stuff. I think virtual appointments have been really good for patients.

P2: I find that now with my chart at the [city] hospital anyway, you can go in and look at your test results and things like that. If you understand what it means. So I will go in there and look at reports and some things I had to fill out for various doctors. I also have the telehealth and mobile applications so I just find any technology, the more technology you can have, you know what it means, it’s useful to have, at times.

3.2.4. Inscriptions

HCP3: the integration of the nurses and the physicians’ assessment which services should be utilized, accessed, and at that time put in place. And so, you know, I think because this so much depends on the individual and on the family, right. So, you don’t have one model that fits everybody, but you have the option of a whole list and menu, and you pick and the nurse’s perspective and the doctor’s perspective, and the patient and his family’s perspective cross off these overlapping needs, or the needs that have been collectively identified, that would be the best-case scenario for me to access the resources available.

P4: Education for me is a huge thing and one of the big areas of focus that I would like to see is more along the lines of chronic disease self-management programs that Stanford have piloted, done with educational workshops for those, in major diseases, but certainly some aspect of understanding chronic disease self-management program and whether that’s through, as P5 and P2 said, the [name of the organization] or through [name of the organization] or linking up with experts from your movement disorder clinic but for me that would be a big role that I would like to see.

P2: I think the wearables, although they have a lot of potential, we’re still trying to understand exactly what we use it for even just measuring Parkinson’s disease and its different dimensions. And then, of course, the next step, how can we use it for care, so I think that will really take longer, it will be a longer process but is still valuable, right? If ideally, we could, technology could help us to understand what’s happening to people living with Parkinson’s between, you know, clinical visits, that will be huge, but I again, I don’t think you’re interested in getting the big data, 20 pages of a report, but in an eloquent, synthetic way can technology gives us a portrait of how, a snapshot of how the patient has been doing in the six months prior to seeing them in person.

4. Discussion

4.1. OPP as “Boundary Spanners” to Enroll Actors

4.2. Intermediaries to Connect Actors in the Networks

4.3. Inscriptions to Support Tailored Care Network and Improve Communication Process

4.4. Practical Implications

4.4.1. Examples of “Boundary Spanners”

4.4.2. Examples of Informational and Technological Infrastructure and Mediators

4.4.3. Examples of Tools, Data and Resources

4.5. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fabbri, M.; Caldas, A.C.; Ramos, J.B.; Sanchez-Ferro, Á.; Antonini, A.; Růžička, E.; Lynch, T.; Rascol, O.; Grimes, D.; Eggers, C.; et al. Moving towards home-based community-centred integrated care in Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2020, 78, 21–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloem, B.R.; Henderson, E.; Dorsey, E.R.; Okun, M.S.; Okubadejo, N.; Chan, P.; Andrejack, J.; Darweesh, S.K.L.; Munneke, M. Integrated and patient-centred management of Parkinson’s disease: A network model for reshaping chronic neurological care. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, D.; Hauteclocque, J.; Grimes, D.; Mestre, T.; Côtéd, D.; Liddy, C. Development of the Integrated Parkinson’s Care Network (IPCN): Using co-design to plan collaborative care for people with Parkinson’s disease. Qual. Life Res. 2019, 28, 1355–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorsey, E.R.; Vlaanderen, F.P.; Engelen, L.J.; Kieburtz, K.; Zhu, W.; Biglan, K.M.; Faber, M.J.; Bloem, B.R. Moving Parkinson care to the home. Mov. Disord. 2016, 31, 1258–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R.; Brennan, L.; Bloem, B.R.; Dahodwala, N.; Gardner, J.; Goldman, J.G.; Grimes, D.A.; Iansek, R.; Kovács, N.; McGinley, J.; et al. Integrated Care in Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mov. Disord. 2020, 35, 1509–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenison, E.; Smink, A.; Redwood, S.; Darweesh, S.; Cottle, H.; Van Halteren, A.; Haak, P.V.D.; Hamlin, R.; Ypinga, J.; Bloem, B.R.; et al. Proactive and Integrated Management and Empowerment in Parkinson’s Disease: Designing a New Model of Care. Park. Dis. 2020, 2020, 8673087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Eijk, M.; Faber, M.J.; Al Shamma, S.; Munneke, M.; Bloem, B.R. Moving towards patient-centered healthcare for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2011, 17, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, J. Notes on the theory of the actor-network: Ordering, strategy, and heterogeneity. Syst. Pract. 1992, 5, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M. Assemblages and Actor-networks: Rethinking Socio-material Power, Politics and Space. Geogr. Compass 2015, 9, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Altabaibeh, A.; Caldwell, K.A.; Volante, M.A. Tracing healthcare organisation integration in the UK using actor–network theory. J. Health Organ. Manag. 2020, 34, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poku, M.K.; Kagan, C.M.; Yehia, B. Moving from Care Coordination to Care Integration. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 1906–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Strategy on People-Centred and Integrated Health Services: Interim Report. World Health Organization, WHO/HIS/SDS/2015.6. 2015. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/155002 (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Kodner, D.L.; Spreeuwenberg, C. Integrated care: Meaning, logic, applications, and implications—A discussion paper. Int. J. Integr. Care 2002, 2, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, P.; Robert, G. Bringing User Experience to Healthcare Improvement: The Concepts, Methods and Practices of Experience-Based Design; Radcliffe Publishing: Oxford, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Donetto, S.; Pierri, P.; Tsianakas, V.; Robert, G. Experience-based Co-design and Healthcare Improvement: Realizing Participatory Design in the Public Sector. Des. J. 2015, 18, 227–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ERA-LEARN. Integrated Parkinson Care Networks: Addressing Complex Care in Parkinson Disease in Contemporary Society. 2018. Available online: https://www.era-learn.eu/network-information/networks/sc1-hco-04-2018/health-and-social-care-for-neurodegenerative-diseases/integrated-parkinson-care-networks-addressing-complex-care-in-parkinson-disease-in-contemporary-society (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Grosjean, S.; Ciocca, J.-L.; Gauthier-Beaupré, A.; Poitras, E.; Grimes, D.; Mestre, T. Co-designing a digital companion with people living with Parkinson’s to support self-care in a personalized way: The eCARE-PD Study. Digit. Health 2022, 8, 20552076221081695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bate, P.; Robert, G. Experience-based design: From redesigning the system around the patient to co-designing services with the patient. Qual. Saf. Health Care 2006, 15, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Simonsen, J.; Robertson, T. Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013; Volume 711. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, S.; Bonneville, L.; Redpath, C. Le patient comme acteur du design en e-santé: Design participatif d’une application mobile pour patients cardiaques. Sci. Des. 2019, 9, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sylvie, G.; Coma, J.F.; Ota, G.; Aoife, L.; Anna, S.; Johanne, S.; Tiago, M. Co-designing an Integrated Care Network with People Living with Parkinson’s Disease: From Patients’ Narratives to Trajectory Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2021, 31, 2585–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendra, A.; Grosjean, S.; Bonneville, L. Co-constructing experiential knowledge in health: The contribution of people living with Parkinson to the co-design approach. Qual. Health Commun. 2022, 1, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: A hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A.; Moser, I.; Pols, J. Care in Practice: On Tinkering in Clinics, Homes and Farms; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, I. Correction to: Contemporary Applications of Actor Network Theory, 1st ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2020; Volume 59, p. 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, R.G.; Andrusyszyn, M.-A.; Iwasiw, C.; Donelle, L.; Compeau, D. Actor-Network Theory as a sociotechnical lens to explore the relationship of nurses and technology in practice: Methodological considerations for nursing research. Nurs. Inq. 2015, 23, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bencherki, N. Actor–Network Theory. In The International Encyclopedia of Organizational Communication; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCarthy, S.; O’Raghallaigh, P.; Woodworth, S.; Lim, Y.L.; Kenny, L.C.; Adam, F. An integrated patient journey mapping tool for embedding quality in healthcare service reform. J. Decis. Syst. 2016, 25, 354–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Trebble, T.M.; Hansi, N.; Hydes, T.; Smith, M.A.; Baker, M. Process mapping the patient journey: An introduction. BMJ 2010, 341, c4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Munster, M.; Stümpel, J.; Thieken, F.; Pedrosa, D.; Antonini, A.; Côté, D.; Fabbri, M.; Ferreira, J.; Růžička, E.; Grimes, D.; et al. Moving towards Integrated and Personalized Care in Parkinson’s Disease: A Framework Proposal for Training Parkinson Nurses. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abendroth, M.; Greenblum, C.A.; Gray, J.A. The Value of Peer-Led Support Groups among Caregivers of Persons with Parkinson’s Disease. Holist. Nurs. Pract. 2014, 28, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Habermann, B.; Davis, L.L. Caring for Family with Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease. J. Gerontol. Nurs. 2005, 31, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekawaty, A.; Malini, H.; Fernandes, F. Family experiences as a caregiver for patients with Parkinson’s disease: A qualitative study. J. Res. Nurs. 2019, 24, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuller, K.A.; Vaughan, B.; Wright, I. Models of Care Delivery for Patients with Parkinson Disease Living in Rural Areas. Fam. Community Health 2017, 40, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-N.; Zheng, D. The Role of the Primary Care Physician in the Management of Parkinson’s Disease Dementia. In Dementia in Parkinson’s Disease-Everything you Need to Know; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, P. The life and times of the boundary spanner. J. Integr. Care 2011, 19, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloem, B.R.; Dorsey, E.R.; Okun, M.S. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 Crisis as Catalyst for Telemedicine for Chronic Neurological Disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, S.; Curry, N.; Goodwin, N. Case Management: What it Is and How it Can Best Be Implemented London: The King’s Fund. 2011. Available online: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Case-Management-paper-The-Kings-Fund-Paper-November-2011_0.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Stümpel, J.; van Munster, M.; Grosjean, S.; Pedrosa, D.J.; Mestre, T.A.; on behalf of the iCare-PD Consortium. Coping Styles in Patients with Parkinson’s Disease: Consideration in the Co-Designing of Integrated Care Concepts. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| PwP *—Characteristics | n = 10 | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 5 |

| Men | 5 | |

| Age | ≤50 | 0 |

| 50–60 | 1 | |

| 61–70 | 4 | |

| ≥71 | 5 | |

| Stage of the disease | Stage 2 | 5 |

| Stage 3 | 4 | |

| Stage 4 | 0 | |

| Stage 5 | 1 | |

| Years since diagnosis | ≤2 years | 1 |

| (2 years ≤ 8 years) | 8 | |

| >8 years | 1 | |

| HCP—Characteristics | n = 5 | |

| Physiotherapists | 1 | |

| PD nurse | 1 | |

| Neurologists | 3 | |

| Concepts | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Actors/actants | Human or non-human entities that interact within networks of other actors. Actors could be individual or collective. |

| Networks | Collection of actors that interact, form, and align with each other for the purposes of accomplishing actions or tasks. |

| Intermediaries/mediators | An individual or object that serves as a connection between two actors. |

| Translation | “Translation consists in one particular actor being able to act as the spokesperson for the many others it manages to enroll in a particular program of action.” [29] (p. 5). The process of translation includes four stages: (i) problematization (bring together actors with common interests), (ii) interessment (convince other actors to play a role in the newly emerging network); (iii) enrollment (when actors accept to play a role in the network); (iv) mobilization of allies. |

| Obligatory Passage Point (OPP) | A dominant actor that becomes a gatekeeper between other actors in the forming network. |

| Inscriptions | Inscription is the process that ascribes meaning to artefacts. Inscriptions could be material elements such as documents but also practices, rules, routines or skills. |

| Events | Diagnostic | Impact on Work, Trips or Activities | Treatment Plan or Change | ON/OFF Episodes or Communication Challenges | Stronger Symptoms, Home Care, and Medical Equipment | Stop Driving, Buy Medical Equipment | Hospitalization Episodes & Rehabilitation Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Touch points | Personal Network Family and Friends Care Network General Practitioner (GP) PD Clinic PD Nurse Tools Booklet about PD Technologies Website about PD & Internet | Personal Network Family and Friends Parkinson Patient & PD associations Care Network GP Physiotherapist Community Network Exercise Groups Sports complexes | Care Network PD Clinic PD Nurse Pharmacist Allied Health Professionals (i.e., Physiotherapist Alternative medicine Professionals) Technologies Websites about PD & Internet | Personal Network CP and Family Formal caregivers Care Network Allied Health Professionals (i.e., physiotherapist, speech therapist) Community Network Community Programs & Resources centres (Volunteers) Community Parkinson’s Group—Networking Group Technologies Internet | Personal Network CP and Family Care Network GP Allied Health Care (i.e., Physiotherapist Occupational therapist Massage Therapist) PD Nurse Community Network Community Programs Care at home program Social worker Transport services Technologies Help Line/Phone Electronic Health Record (EHR) Virtual care | Personal Network CP and family Friends Care Network Occupational therapist Physiotherapist Community Network Transport services Community Programs Social worker Technologies Information resources (online or in accessible format) | Care Network PD clinic PD nurse Rehab Program Physiotherapist Community Network Community Programs/Exercise Group Parkinson’s Association Technologies EHR |

| Barriers | Lack of support/ guidance -Difficulty identifying who is better suited to address specific needs or issues. -Lack of clear direction before & after diagnosis. Lack of knowledge about PD (family and GP). Lack of trust in the care team (e.g., first neurologist). Inequality of access -Long wait time to see a neurologist | Lack of guidance to navigate local resources -Lack of knowledge about local resources Personal attitude & condition -Stress -Concerns about bothering people—Taking up time from other people | Lack of PD expertise in the community services | Personal skills or attitudes -Safety concerns limiting access to community resources and activities -Computer literacy Lack of guidance to navigate local resources -Lack of knowledge about local resources Lack of PD expertise in the community services | Treatment efficacy -Medication less effective -uncontrolled symptoms -Pain, anxiety or loss of independence Environmental constraints -Technological difficulties (needing to do virtual consultation) Lack of support/guidance -Limited help—respite for informal caregivers Inequality of access -Waiting time to access day programs (e.g., Bruyère Day Program) -Lack of transportation services -Lack of financial resources Lack of PD expertise in the community services | Inequality of access -Lack of access to transportation services -Lack of financial support to buy medical equipment -Waiting time to access occupational therapist or care at home Lack of support/guidance -Limited help—Respite for informal caregivers Environmental constraints -Lack of mobility and risk of social isolation) | Inequality of access -Long wait time at local hospital (not specialized PD clinic) -Lack of support for CP and family -Distance from PD clinic Personal condition -Loss of autonomy and independence Lack of PD expertise in the community services |

| Facilitators | Single point of contact -Having a contact person to ask questions (nurse or general practitioner). Easy access to information -Easy access to information (via mediator or personal research) -Personal information-seeking behaviour | Personal network -Support from family & friends. -Support groups (PD associations). Access to educational resources -Educational resources about PD & treatments available | Positive and trusting relationship with the care team -Access to caring & knowledgeable health care professionals Treatment efficiency -Appropriate medication to control symptoms -Access to alternative medicine Single point of contact -Mediators to connect PwP with community services -Virtual visits (distance from clinic) Access to financial aid | Access to useful & tailored educational resources or programs -Improve patient education by focusing on tailored needs -Sufficient knowledge to get appropriate information -Online support groups Access to caring & knowledgeable health care professionals -Maintain close relationship Single point of contact & information brokers | Access to home support -Care from other individuals—respite care Access to local clinic (convenience) Single point of contact -Mediators to connect PwP with community services (informal caregivers) Easy communication channel -Emergency phone call (Help line) Accessible environment and equipment | Single point of contact -Mediators to connect PwP with community services Access to home support Access to home support Access to financial aid Easy access to information Via mediators or personal research | Single point of contact -Mediators to connect PwP with community services Access to home support |

| Core Themes Based on ANT | Subthemes | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Networks | Personal network/Care network/Community network | ||

| Actors/Actants | Personal network | Care network | Community network |

| Informal caregivers | PD clinic | Community services or program | |

| Work colleagues | Neurologist | Domestic support or home care | |

| Friends | Specialized Nurse | Transportation services | |

| Supports groups | Allied professionals | Social workers | |

| Patient’s organizations | GP | Financial resources | |

| mHealth | Pharmacist | Medical equipment | |

| Assistive technologies | |||

| Virtual care | |||

| OPP | Single point of contact and Navigation tools | ||

| Intermediaries Mediators | People | Organizational structure and programs | Technologies |

| Specialized or PD nurse | Patient buddy | Family orientation programs | |

| Facilitators/information brokers (i.e., social worker, GP) | Patient advisory board for iCARE-PD | HER—eConsult/Help Line | |

| Inscriptions | Shared assessment tools Tailored educational resources Emotional/psychological programs or resources Sensors/wearable devices (big data and precision medicine) | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gauthier-Beaupré, A.; Poitras, E.; Grosjean, S.; Mestre, T.A.; on behalf of the iCARE-PD Consortium. Co-Designing an Integrated Care Network with People Living with Parkinson’s Disease: A Heterogeneous Social Network of People, Resources and Technologies. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12061001

Gauthier-Beaupré A, Poitras E, Grosjean S, Mestre TA, on behalf of the iCARE-PD Consortium. Co-Designing an Integrated Care Network with People Living with Parkinson’s Disease: A Heterogeneous Social Network of People, Resources and Technologies. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022; 12(6):1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12061001

Chicago/Turabian StyleGauthier-Beaupré, Amélie, Emely Poitras, Sylvie Grosjean, Tiago A. Mestre, and on behalf of the iCARE-PD Consortium. 2022. "Co-Designing an Integrated Care Network with People Living with Parkinson’s Disease: A Heterogeneous Social Network of People, Resources and Technologies" Journal of Personalized Medicine 12, no. 6: 1001. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm12061001