Improvements in Treatment Adherence after Family Psychoeducation in Patients Affected by Psychosis: Preliminary Findings

Abstract

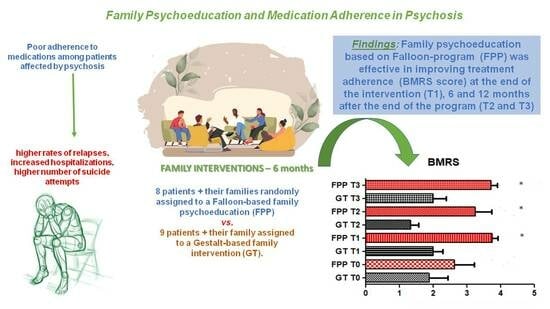

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Aim of the Study

2.3. Interventions

2.4. Assessment

- -

- The Mini-Mental State Examination by Folstein 1975 [27], or MMSE, is a simple pen-and-paper test of cognitive functioning; it explores patient’s orientation, concentration, attention, verbal memory, and naming and visuospatial skills. A total score ranging from 24 to 30 points indicates normal cognitive functioning; scores ranging between 18 and 23 indicate a mild/moderate cognitive impairment; and scores ≤ 17 indicate a severe cognitive impairment.

- -

- The Brief Medication Adherence Report Scale (BMARS), a shorter form of the MARS-10, was employed as a measure of treatment adherence in the clinical setting [28]. It includes five-items based on a yes/no self-reporting scoring system; total scores may vary from 0 (low medication adherence) to 5 (high medication adherence) [29].

- -

- The Personal Social Performance (PSP) scale assesses functioning across four dimensions (socially useful activities, personal and social relationships, self-care, and disturbing/aggressive behaviors), with instructions on how to assess the patient and assign a score. The score ranges from 1 to 100, with 100 indicating the highest level of patient functioning [30].

- -

- The World Health Organization Quality of Life—BREF (WHOQOL-Brief) is a 26-item tool used to measure patients’ quality of life. Each item is scored from 1 to 5. Higher scores indicate a better quality of life. This tool explores four domains of quality of life: physical health, psychological well-being, social relationships, and environment [31]. Physical health includes items on mobility, daily activities, functional capacity, energy, pain, and sleep. Psychological measures include self-image, negative thoughts, positive attitudes, self-esteem, mindset, learning ability, memory concentration, religion, and mental state. The domain regarding the social relations contains questions about personal relationships, social support, and sex life. The environmental domain explores financial resources, safety, health and social services, the physical environment in which one lives, recreational activities, and the general environment (noise, air pollution, transportation, etc.) [32].

- -

- The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) measures the severity of symptoms in schizophrenia. It is a 30-item scale exploring the positive and negative symptoms of illness and their relationship with the global psychopathology [33]. The PANSS includes three subscales: the Positive Scale, the Negative Scale, and the General Psychopathology Scale. Each subscale is rated from 1 to 7 points, i.e., from absent to extremely severe. The score of each subscale is the sum of the responses, while the total PANSS score is the sum of the subscales [34]. A composite scale, as considered in this study, was scored by subtracting the negative score from the positive one (PANSS composite scale = PANSS positive syndrome scale score – PANSS negative syndrome scale score). This yielded an index ranging from −42 to +42, reflecting the degree of predominance/balance of positive and negative symptoms [34].

- -

- The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) [35] is the most widely used scale to measure general psychopathology in patients affected by psychiatric conditions. The scale consists of 24 items to be rated on a seven-point severity scale ranging from “not present” to “extremely severe”. It is based on a clinical interview and the patient’s behavior. The patient’s family can also provide a behavioral report on the patient [36]. The BPRS measures psychiatric symptoms of depression, anxiety, and psychosis in both clinical and research settings [37].

- -

- The Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI) assesses the severity of illness and its changes from baseline as consequence of treatments. The CGI severity assessment is provided on a seven-point scale; additionally, improvements are rated on a seven-point scale, where responses may range from “much improved” to “much worsened” [38].

- -

- The Five Point Test (5TT) is a neuropsychological test assessing figural fluency. The participant is asked to generate as many unique drawings as possible within a certain time limit [39]. The task to be performed is to produce as many different patterns as possible by connecting the dots in each square with one or more straight lines within two minutes. The correction is done by calculating some indices: the number of total drawings; the number of errors made; the number of unique drawings (UD); the number of strategies used, such as rotation (CS); and the error index (ErrI) as the proportion of the cumulative number of failed drawings to the number of total drawings [40].

- -

- The Family Questionnaire (FQ) is a 20-item, self-administered questionnaire that measures the Emotional state Expressed (EE) through two subscales: criticism and the excessive emotional involvement of family members toward patients with a mental illness [37]. Each item is rated on a four-point scale (1 = never/very rarely; 4 = very often). The FQ is scored by summing each item rating; higher scores on one or both subscales (criticality ≥ 24; emotional hyper involvement ≥ 28) indicate a high degree of expressed emotion [41].

- -

- The Modified Overt Aggression Scale (MOAS) assesses the presence of four types of aggressive behavior: verbal aggression, aggression against property, self-aggression, and physical aggression. Aggressive acts are scored on the basis of their severity, from 0 to 4. The value of each item is multiplied by a specific factor assigned to each category: 1 for verbal aggression, 2 for aggression against objects, 3 for aggression against self, and 4 for aggression against others. The total score ranges from 0 to 40, where a higher score indicates a greater presence of aggressive behaviors [42].

2.5. Ethical Considerations

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Comptonm, M.T.; Broussard, B. The First Episode of Psychosis: A Guide for Patients and Their Families; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Best, M.W.; Bowie, C.R. Social exclusion in psychotic disorders: An interactional processing model. Schizophr. Res. 2022, 244, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, W.C.; Chen, E.S.M.; Hui, C.L.M.; Chan, S.K.W.; Lee, E.H.M.; Chen, E.Y.H. The relationships of suicidal ideationwith symptoms, neurocognitive function, and psychological factors in patients with first-episode psychosis. Schizophr. Res. 2014, 157, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, D.F.K.; Lam, A.Y.K.; Chan, S.K.; Chan, S.F. Quality of life of caregivers with relatives suffering from mental illness in Hong Kong: Roles of caregiver characteristics, caregiving burdens, and satisfaction with psychiatric services. Health Qual. Life Outcomes. 2012, 10, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haddad, P.M.; Brain, C.; Scott, J. Non adherence with antipsychotic medication in schizophrenia: Challenges and management strategies. Dove Med. Press 2014, 5, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashi, K.; Medic, G.; Littlewood, K.J.; Diez, T.; Granström, O.; De Hert, M. Medication adherence in schizophrenia: Factors influencing adherence and consequences of non-adherence, a systematic literature review. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol. 2013, 3, 200–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, B.A.; McGinty, E.E.; Zhang, Y.; dos Reis, S.C.; Steinwachs, D.M.; Guallar, E.; Daumit, G.L. Guideline-concordant antipsychotic use and mortality in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2013, 39, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, V.; Lora, A.; Cipriani, A.; Fortino, I.; Merlino, L.; Barbui, C. Persistence with pharmacological treatment in the specialist mental healthcare of patients with severe mental disorders. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 68, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, S.; Martínez-Cengotitabengoa, M.; López-Zurbano, S.; Zorrilla, I.; López, P.; Vieta, E.; González-Pinto, A. Adherence to antipsychotic medication in bipolar disorder and schizophrenic patients: A systematic review. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 36, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huxley, N.A.; Rendall, M.; Sederer, L. Psychosocial treatments in schizophrenia: A review of the past 20 years. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2000, 88, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falloon, I.R.H.; Roncone, R.; Held, T.; Coverdale, J.H.; Laidlaw, T.M. An international overview of family interventions: Developing effective treatment strategies and measuring their benefits to patients, carers, and communities. In Family Interventions in Mental Illness: International Perspectives; Lefley, H.P., Johnson, D.L., Eds.; Westport: Greenwood, SC, USA, 2002; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yesufu-Udechuku, A.; Harrison, B.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; Young, N.; Woodhams, P.; Shiers, D.; Kuipers, E.; Kendall, T. Interventions to improve the experience of caring for people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2015, 206, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falloon, I.R.H.; Fadden, G.; Mueser, K.; Gingerich, S.; Rappaport, S.; McGill, C.; Graham-Hole, V.; Gair, F. Family Work Manual; Meriden Family Programme: Birmingham, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Falloon, I.R. Family interventions for mental disorders: Efficacy and effectiveness. World Psychiatry 2003, 2, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galletly, C.A. Effective family interventions for people with schizophrenia. Lancet. Psychiatry 2022, 9, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodolico, A.; Bighelli, I.; Avanzato, C.; Concerto, C.; Cutrufelli, P.; Mineo, L.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Siafis, S.; Signorelli, M.S.; Wu, H.; et al. Family interventions for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. Psychiatry 2022, 9, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorillo, A.; Del Vecchio, V.; Luciano, M.; Sampogna, G.; De Rosa, C.; Malangone, C.; Volpe, U.; Bardicchia, F.; Ciampini, G.; Crocamo, C.; et al. Efficacy of psychoeducational family intervention for bipolar I disorder: A controlled, multicentric, real-world study. J. Affect. Disord. 2015, 172, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petretto, D.R.; Preti, A.; Zuddas, C.; Veltro, F.; Rocchi, M.B.; Sisti, D.; Martinelli, V.; Carta, M.G.; Masala, C.; SPERA-S group. Study on psychoeducation enhancing results of adherence in patients with schizophrenia (SPERA-S): Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2013, 14, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltro, F.; Magliano, L.; Morosini, P.; Fasulo, E.; Pedicini, G.; Cascavilla, I.; Falloon, I.; Gruppo di Lavoro DSM-BN1. Studio controllato randomizzato di un intervento psicoeducativo familiare: Esito ad 1 e a 11 anni [Randomised controlled trial of a behavioural family intervention: 1 year and 11-years follow-up]. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2006, 15, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncone, R.; Giusti, L.; Bianchini, V.; Casacchia, M.; Carpiniello, B.; Aguglia, E.; Altamura, M.; Barlati, S.; Bellomo, A.; Bucci, P.; et al. Family functioning and personal growth in Italian caregivers living with a family member affected by schizophrenia: Results of an add-on study of the Italian network for research on psychoses. Front. Psychiatr. 2023, 13, 1042657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; Text Revision; American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D.V.; Lecrubier, Y.; Sheehan, K.H.; Amorim, P.; Janavs, J.; Weiller, E.; Hergueta, T.; Baker, R.; Dunbar, G.C. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1889, 59 (Suppl. S20), 22–57. [Google Scholar]

- Falloon, I. Intervento Psicoeducativo Integrato in Psichiatria. Guida al Lavoro con le Famiglie; Magliano, L.; Morosini, P., Translators; Edizioni Centro Studi Erickson: Trento, Italy, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Koolaee, A.K.; Etemadi, A. The outcome of family interventions for the mothers of schizophrenia patients in Iran. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2010, 56, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, R. Gestalt approach to family therapy. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 1979, 7, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falloon, I.R.; Boyd, J.L.; McGill, C.W.; Williamson, M.; Razani, J.; Moss, H.B.; Gilderman, A.M.; Simpson, G.M. Family management in the prevention of morbidity of schizophrenia: Clinical outcome of a two-year longitudinal study. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 1985, 42, 887–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state”: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psych. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, A.H.Y.; Horne, R.; Hankins, M.; Chisari, C. The medication adherence report scale: A measurement tool for eliciting patients’ reports of nonadherence. Fr. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 86, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byerly, M.J.; Nakonezny, P.A.; Rush, A.J. The Brief Adherence Rating Scale (BARS) validated against electronic monitoring in assessing the antipsychotic medication adherence of outpatients with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Schizophr. Ris. 2008, 100, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, S.; Dominise, C.; Naik, D.; Killaspy, H. The reliability of the Personal and Social Performance scale—Informing its training and use. Psychiatry Res. 2016, 243, 312–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, S. World Health Organization Quality-of-Life Scale (WHOQOL-BREF): Analyses of their item response theory properties based on the graded responses model. Iran. J. Psychiatry 2010, 5, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Nejat, S.A.H.A.R.N.A.Z.; Montazeri, A.; Holakouie Naieni, K.; Mohammad, K.A.Z.E.M.; Majdzadeh, S.R. The World Health Organization quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire: Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. J. Sch. Public Health Inst. Public Health Res. 2006, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, S.R. Positive-negative symptom assessment in schizophrenia: Psychometric issues and scale comparison. Psychiatr. Q. 1990, 61, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kay, S.R.; Fizbein, A.; Opler, L.A. The positive and negative sympton scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schiophr. Bull. 1987, 13, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanello, A.; Berthoud, L.; Ventura, J.; Merlo, M.C. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (version 4.0) factorial structure and its sensitivity in the treatment of outpatients with unipolar depression. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 210, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncone, R.; Ventura, J.; Impallomeni, M.; Falloon, I.; Morosini, P.L.; Chiaravalle, E.; Casacchia, M. Reliability of an Italian standardized and expanded Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS 4.0) in raters with high vs. low clinical experience. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1999, 100, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafkenscheid, A. Psychometric measures of individual change: An empirical comparison with the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000, 101, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busner, J.; Targum, S.D. The clinical global impressions scale: Applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry 2007, 4, 28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tucha, L.; Aschenbrenner, S.; Koerts, J.; Lange, K.W. The Five-Point Test: Reliability, validity and normative data for children and adults. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e46080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattelani, R.; Dal Sasso, F.; Corsini, D.; Posteraro, L. The Modified Five-Point Test: Normative data for a sample of Italian healthy adults aged 16–60. J. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 32, 595–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiedemann, G.; Rayki, O.; Feinstein, E.; Hahlweg, K. The Family Questionnaire: Development and validation of a new self-report scale for assessing expressed emotion. Psychiatry Res. 2002, 109, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margari, F.; Matarazzo, R.; Casacchia, M.; Roncone, R.; Dieci, M.; Safran, S.; Simoni, L. Italian validation of MOAS and NOSIE: A useful package for psychiatric assessment and monitoring of aggressive behaviours. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2005, 14, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magni, E.; Binetti, G.; Bianchetti, A.; Rozzini, R.; Trabucchi, M. Mini-Mental State Examination: A normative study in Italian elderly population. Eur. J. Neurol. 1996, 3, 198–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponti, L.; Stefanini, M.C.; Troiani, M.R.; Tani, F. A study on the Italian validation of the family questionnaire. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 1116–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pancheri, P.; Brugnoli, R. Valutazione dimensionale della sintomatologia schizofrenica. Validazione della versione italiana della Scala per la valutazione dei Sintomi Positivi e Negativi (PANSS). Ital. J. Psychopathol. 1995, 1, 60–75. [Google Scholar]

- De Girolamo, G.; Rucci, P.; Scocco, P.; Becchi, A.; Coppa, F.; D’Addario, A.; Darú, E.; De Leo, D.; Galassi, L.; Mangelli, L.; et al. La valutazione della qualità della vita: Validazione del WHOQOL-Breve [Quality of life assessment: Validation of the Italian version of the WHOQOL-Brief]. Epidemiol. Psichiatr. Soc. 2000, 9, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosini, P.L.; Magliano, L.; Brambilla, L.; Ugolini, S.; Pioli, R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2000, 101, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SOLE Study Group. Translation and initial validation of the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS) in Italian patients with Crohn’s Disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 2019, 51, 640–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventriglio, A.; Ricci, F.; Magnifico, G.; Chumakov, E.; Torales, J.; Watson, C.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Petito, A.; Bellomo, A. Psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia: Focus on guidelines. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventriglio, A.; Petito, A.; Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Torales, J.; Sannicandro, V.; Milano, E.; Iuso, S.; Bellomo, A. Use of Psychoeducation for Psychotic Disorder Patients Treated with Modern, Long-Acting, Injected Antipsychotics. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 804612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iuso, S.; Severo, M.; Ventriglio, A.; Bellomo, A.; Limone, P.; Petito, A. Psychoeducation Reduces Alexithymia and Modulates Anger Expression in a School Setting. Children 2022, 9, 1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventriglio, A.; Gentile, A.; Baldessarini, R.J.; Bellomo, A. Early-life stress and psychiatric disorders: Epidemiology, neurobiology and innovative pharmacological targets. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, N.; Vahlne, J.O.; Edman, A. Family intervention in schizophrenia—Impact on family burden and attitude. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2003, 38, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, N.; Watanabe, N.; Katsuki, F.; Sakaguchi, H.; Akechi, T. Effectiveness of the Japanese standard family psychoeducation on the mental health of caregivers of young adults with schizophrenia: A randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics at T0, Baseline | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|

| GT | FPP | |

| Patients’ current age | ||

| 38.6 ± 10.8 | 36.8 ± 8.70 | 0.7074 |

| Sex (males) | ||

| 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) | 0.0235 |

| Education (years) | ||

| 11.4 ± 3.67 | 12.3 ± 4.86 | 0.6606 |

| Employment (yes) | ||

| 4 (66.7%) | 2 (33.3%) | 0.4024 |

| The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | ||

| 17.6 ± 5.31 | 23.7 ± 9.45 | 0.1389 |

| 5 Point (The Five Point Test) | ||

| 4.77 ± 2.86 | 5.12 ± 0.83 | 0.7361 |

| BPRS (The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale) | ||

| 47.0 ± 12.2 | 51.2 ± 22.1 | 0.6399 |

| Family Questionnaire-EE (Expressed Emotionality) | ||

| 18.9 ± 3.75 | 15.0 ± 7.03 | 0.1918 |

| PANSS (The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale)-composite scale | ||

| 13.7 ± 5.01 | 13.3 ± 5.65 | 0.8794 |

| WHOQOL-B (The World Health Organization Quality of Life—BREF) | ||

| 54.5 ± 7.90 | 62.0 ± 13.23 | 0.1931 |

| SPS (The Personal Social Performance) | ||

| 42.4 ± 13.1 | 48.0 ± 14.7 | 0.4290 |

| MOAS (Modified Overt Aggression Scale) | ||

| 3.00 ± 2.82 | 1.75 ± 2.05 | 0.3112 |

| CGI (The Clinical Global Impression Scale) | ||

| 3.88 ± 1.16 | 3.62 ± 1.56 | 0.6955 |

| BMARS (The Brief Medication Adherence Report Scale) | ||

| 1.88 ± 1.61 | 2.62 ± 1.68 | 0.3749 |

| T0, Baseline | T1, after the Intervention | T2, 6 Months from the End | T3, 12 Months from the End | F | p-Value | Post Hoc Test (Bonferroni) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GT | FPP | GT | FPP | GT | FPP | GT | FPP | p-Value | ||

| The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) | ||||||||||

| 17.6 ± 5.31 | 23.7 ± 9.45 | 15.1 ± 4.91 | 23.6 ± 13.09 | 15.3 ± 4.06 | 19.6 ± 6.67 | 14.6 ± 3.46 | 20.0 ± 8.52 | 0.1821 | 0.9082 | 0.4376 |

| 5 Point (The Five Point Test) | ||||||||||

| 4.77 ± 2.86 | 5.12 ± 0.83 | 4.11 ± 2.31 | 4.25 ± 1.48 | 3.55 ± 1.74 | 4.00 ± 1.30 | 3.82 ± 1.64 | 3.28 ± 1.38 | 0.2535 | 0.8585 | 0.6753 |

| BPRS (The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale) | ||||||||||

| 47.0 ± 12.2 | 51.2 ± 22.1 | 39.8 ± 8.89 | 48.3 ± 27.4 | 48.5 ± 12.3 | 51.7 ± 22.1 | 49.1 ± 14.0 | 54.7 ± 24.7 | 0.0643 | 0.9785 | 0.2235 |

| Family Questionnaire-EE (Expressed Emotionality) | ||||||||||

| 18.9 ± 3.75 | 15.0 ± 7.03 | 18.4 ± 6.48 | 18.1 ± 8.02 | 19.4 ± 7.00 | 19.5 ± 6.56 | 18.3 ± 6.36 | 22.0 ± 4.35 | 1.0240 | 0.3883 | 0.4563 |

| PANSS (The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale)-composite scale | ||||||||||

| 13.7 ± 5.01 | 13.3 ± 5.65 | 12.2 ± 3.83 | 13.8 ± 5.66 | 14.1 ± 4.62 | 14.7 ± 4.92 | 14.3 ± 4.03 | 15.8 ± 6.89 | 0.1408 | 0.9351 | 0.7658 |

| WHOQOL-B (The World Health Organization Quality of Life—BREF) | ||||||||||

| 54.5 ± 7.90 | 62.0 ± 13.23 | 58.4 ± 11.4 | 58.3 ± 13.1 | 53.8 ± 11.6 | 52.3 ± 8.34 | 51.3 ± 11.58 | 49.1 ± 11.8 | 0.6657 | 0.5764 | 0.5757 |

| SPS (The Personal Social Performance) | ||||||||||

| 42.4 ± 13.1 | 48.0 ± 14.7 | 48.2 ± 14.8 | 48.5 ± 15.4 | 46.8 ± 16.1 | 43.7 ± 14.0 | 43.3 ± 16.8 | 37.0 ± 11.3 | 0.5103 | 0.6767 | 0.5234 |

| MOAS (Modified Overt Aggression Scale) | ||||||||||

| 3.00 ± 2.82 | 1.75 ± 2.05 | 3.22 ± 3.23 | 1.75 ± 2.25 | 4.33 ± 3.24 | 3.37 ± 3.37 | 5.25 ± 3.45 | 3.42 ± 2.63 | 0.0659 | 0.9777 | 0.2387 |

| CGI (The Clinical Global Impression Scale) | ||||||||||

| 3.88 ± 1.16 | 3.62 ± 1.56 | 3.77 ± 1.09 | 3.75 ± 1.66 | 4.00 ± 0.70 | 4.00 ± 1.51 | 3.75 ± 1.03 | 4.00 ± 1.73 | 0.1042 | 0.9573 | 0.1435 |

| BMARS (The Brief Medication Adherence Report Scale) | ||||||||||

| 1.88 ± 1.61 | 2.62 ± 1.68 | 2.00 ± 0.86 | 3.75 ± 0.46 | 1.33 ± 0.76 | 3.25 ± 1.38 | 2.00 ± 1.06 | 3.71 ± 0.48 | 0.9496 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iuso, S.; Severo, M.; Trotta, N.; Ventriglio, A.; Fiore, P.; Bellomo, A.; Petito, A. Improvements in Treatment Adherence after Family Psychoeducation in Patients Affected by Psychosis: Preliminary Findings. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13101437

Iuso S, Severo M, Trotta N, Ventriglio A, Fiore P, Bellomo A, Petito A. Improvements in Treatment Adherence after Family Psychoeducation in Patients Affected by Psychosis: Preliminary Findings. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2023; 13(10):1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13101437

Chicago/Turabian StyleIuso, Salvatore, Melania Severo, Nicoletta Trotta, Antonio Ventriglio, Pietro Fiore, Antonello Bellomo, and Annamaria Petito. 2023. "Improvements in Treatment Adherence after Family Psychoeducation in Patients Affected by Psychosis: Preliminary Findings" Journal of Personalized Medicine 13, no. 10: 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13101437

APA StyleIuso, S., Severo, M., Trotta, N., Ventriglio, A., Fiore, P., Bellomo, A., & Petito, A. (2023). Improvements in Treatment Adherence after Family Psychoeducation in Patients Affected by Psychosis: Preliminary Findings. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 13(10), 1437. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13101437