Analysis of Frailty Syndrome in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Scoping Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

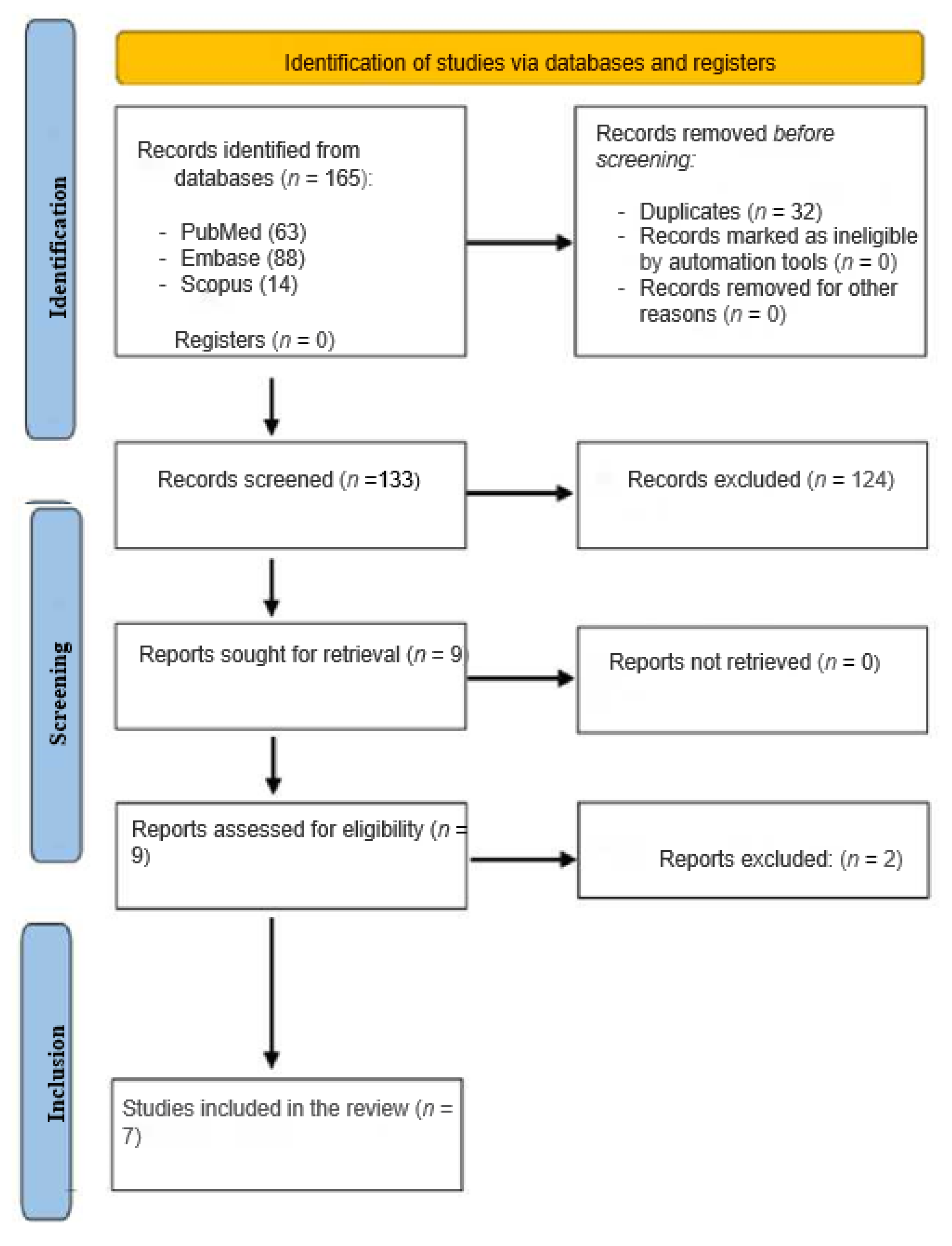

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Analysis of Information in the Selected Studies

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies Analyzed

3.2. The Frailty Scales Used

3.3. Frailty Analysis between Metastatic and Non-Metastatic Prostate Cancer

3.4. The Relationship between Frailty and Other Clinical Variables

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Clegg, A.; Young, J.; Iliffe, S.; Rikkert, M.O.; Rockwood, K. Frailty in Elderly People. Lancet 2013, 381, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fried, L.P.; Tangen, C.M.; Walston, J.; Newman, A.B.; Hirsch, C.; Gottdiener, J.; Seeman, T.; Tracy, R.; Kop, W.J.; Burke, G.; et al. Frailty in Older AdultsEvidence for a Phenotype. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 2001, 56, M146–M157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, D.A.; O’Neil, M.E.; Richards, T.B.; Dowling, N.F.; Weir, H.K. Prostate Cancer Incidence and Survival, by Stage and Race/Ethnicity—United States, 2001–2017. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohile, S.G.; Xian, Y.; Dale, W.; Fisher, S.G.; Rodin, M.; Morrow, G.R.; Neugut, A.; Hall, W. Association of a Cancer Diagnosis With Vulnerability and Frailty in Older Medicare Beneficiaries. JNCI J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, T.N.; Walston, J.D.; Brummel, N.E.; Deiner, S.; Brown, C.H.; Kennedy, M.; Hurria, A. Frailty for Surgeons: Review of a National Institute on Aging Conference on Frailty for Specialists. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2015, 221, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildiers, H.; Heeren, P.; Puts, M.; Topinkova, E.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.G.; Extermann, M.; Falandry, C.; Artz, A.; Brain, E.; Colloca, G.; et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology Consensus on Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients with Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzmaurice, C.; Allen, C.; Barber, R.M.; Barregard, L.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brenner, H.; Dicker, D.J.; Chimed-Orchir, O.; Dandona, R.; Dandona, L.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived with Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-Years for 32 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlay, J.; Parkin, D.M.; Steliarova-Foucher, E. Estimates of Cancer Incidence and Mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur. J. Cancer 2010, 46, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cayuela, L.; Lendínez-Cano, G.; Chávez-Conde, M.; Rodríguez-Domínguez, S.; Cayuela, A. Recent trends in prostate cancer in Spain. Actas Urol. Esp. (Engl. Ed.) 2020, 44, 483–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado de la Orden, S.; Saá Requejo, C.; Quintás Viqueira, A. Situación Epidemiológica Del Cáncer de Próstata En España. Actas Urol. Esp. 2006, 30, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martinez-Amores Martinez, B.; Durán Poveda, M.; Sánchez Encinas, M.; Molina Villaverde, R. Actualización En Cáncer de Próstata. Med. -Programa Form. Médica Contin. Acreditado 2013, 11, 1578–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brawley, O.W. Prostate Cancer Epidemiology in the United States. World J. Urol. 2012, 30, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebello, R.J.; Oing, C.; Knudsen, K.E.; Loeb, S.; Johnson, D.C.; Reiter, R.E.; Gillessen, S.; van der Kwast, T.; Bristow, R.G. Prostate Cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2021, 7, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.A.; Hollen, P.J.; Wenzel, J.; Weiss, G.; Song, D.; Sims, T.; Petroni, G. Understanding Advanced Prostate Cancer Decision-Making Utilizing an Interactive Decision Aid. Cancer Nurs. 2018, 41, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, e1–e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaya, T.; Hatakeyama, S.; Momota, M.; Narita, T.; Iwamura, H.; Kojima, Y.; Hamano, I.; Fujita, N.; Okamoto, T.; Togashi, K.; et al. Association between the Baseline Frailty and Quality of Life in Patients with Prostate Cancer (FRAQ-PC Study). Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 26, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momota, M.; Hatakeyama, S.; Soma, O.; Tanaka, T.; Hamano, I.; Fujita, N.; Okamoto, T.; Yoneyama, T.; Yamamoto, H.; Imai, A.; et al. Geriatric 8 Screening of Frailty in Patients with Prostate Cancer. Int. J. Urol. 2020, 27, 642–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handforth, C.; Burkinshaw, R.; Freeman, J.; Brown, J.E.; Snowden, J.A.; Coleman, R.E.; Greenfield, D.M. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment and Decision-Making in Older Men with Incurable but Manageable (Chronic) Cancer. Support. Care Cancer 2019, 27, 1755–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- della Pepa, C.; Cavaliere, C.; Rossetti, S.; di Napoli, M.; Cecere, S.C.; Crispo, A.; de Sangro, C.; Rossi, E.; Turitto, D.; Germano, D.; et al. Predictive Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in Elderly Prostate Cancer Patients: The Prospective Observational Scoop Trial Results. Anticancer Drugs 2017, 28, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, H.M.; Llaniguez, J.T.; Telemi, E.; Chuang, M.; Abouelleil, M.; Wilkinson, B.; Chandra, A.; Boyce-Fappiano, D.; Elibe, E.; Schultz, L.; et al. Sarcopenia Predicts Overall Survival in Patients with Lung, Breast, Prostate, or Myeloma Spine Metastases Undergoing Stereotactic Body Radiation Therapy (SBRT), Independent of Histology. Neurosurgery 2020, 86, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Martínez, R.; Serrano-Carrascosa, M.; Buigues, C.; Fernández-Garrido, J.; Sánchez-Martínez, V.; Castelló-Domenech, A.B.; García-Villodre, L.; Wong-Gutiérrez, A.; Rubio-Briones, J.; Cauli, O. Frailty Syndrome Is Associated with Changes in Peripheral Inflammatory Markers in Prostate Cancer Patients Undergoing Androgen Deprivation Therapy. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2019, 37, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buigues, C.; Navarro-Martínez, R.; Sánchez-Martínez, V.; Serrano-Carrascosa, M.; Rubio-Briones, J.; Cauli, O. Interleukin-6 and Lymphocyte Count Associated and Predicted the Progression of Frailty Syndrome in Prostate Cancer Patients Undergoing Antiandrogen Therapy. Cancers 2020, 12, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decoster, L.; van Puyvelde, K.; Mohile, S.; Wedding, U.; Basso, U.; Colloca, G.; Rostoft, S.; Overcash, J.; Wildiers, H.; Steer, C.; et al. Screening Tools for Multidimensional Health Problems Warranting a Geriatric Assessment in Older Cancer Patients: An Update on SIOG Recommendations. Ann. Oncol. 2015, 26, 288–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, G.; Gardner, M.; Tsiachristas, A.; Langhorne, P.; Burke, O.; Harwood, R.H.; Conroy, S.P.; Kircher, T.; Somme, D.; Saltvedt, I.; et al. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment for Older Adults Admitted to Hospital. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2017, CD006211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.J.; Malik, A.T.; Jain, N.; Yu, E.; Kim, J.; Khan, S.N. The Modified 5-Item Frailty Index: A Concise and Useful Tool for Assessing the Impact of Frailty on Postoperative Morbidity Following Elective Posterior Lumbar Fusions. World Neurosurg. 2019, 124, e626–e632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwood, K.; Song, X.; MacKnight, C.; Bergman, H.; Hogan, D.B.; McDowell, I.; Mitnitski, A. A Global Clinical Measure of Fitness and Frailty in Elderly People. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2005, 173, 489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, S.; Rogers, E.; Rockwood, K.; Theou, O. A Scoping Review of the Clinical Frailty Scale. BMC Geriatr. 2020, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, C.F.; Christie, D.R.H.; Bitsika, V. Depression and Prostate Cancer: Implications for Urologists and Oncologists. Nat. Rev. Urol. 2020, 17, 571–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collard, R.M.; Boter, H.; Schoevers, R.A.; Oude Voshaar, R.C. Prevalence of Frailty in Community-Dwelling Older Persons: A Systematic Review. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2012, 60, 1487–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ethun, C.G.; Bilen, M.A.; Jani, A.B.; Maithel, S.K.; Ogan, K.; Master, V.A. Frailty and Cancer: Implications for Oncology Surgery, Medical Oncology, and Radiation Oncology. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2017, 67, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martinez-Tapia, C.; Canoui-Poitrine, F.; Bastuji-Garin, S.; Soubeyran, P.; Mathoulin-Pelissier, S.; Tournigand, C.; Paillaud, E.; Laurent, M.; Audureau, E. Optimizing the G8 Screening Tool for Older Patients With Cancer: Diagnostic Performance and Validation of a Six-Item Version. Oncologist 2016, 21, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardhana, D.D.; Hardoon, S.; Rait, G.; Weerasinghe, M.C.; Walters, K.R. Prevalence of Frailty and Prefrailty among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in Low-Income and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2018, 8, 18195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockwood, K.; Mitnitski, A. Frailty in Relation to the Accumulation of Deficits. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2007, 62, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornford, P.; van den Bergh, R.C.N.; Briers, E.; van den Broeck, T.; Cumberbatch, M.G.; de Santis, M.; Fanti, S.; Fossati, N.; Gandaglia, G.; Gillessen, S.; et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-SIOG Guidelines on Prostate Cancer. Part II-2020 Update: Treatment of Relapsing and Metastatic Prostate Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2020, 79, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourey, L.; Gravis, G.; Sevin, E.; Priou, F.; Bompas, E.; Sarda, C.; Houede, N.; Carola, E.; Lacourtoisie, S.A.; Latorzeff, I.; et al. Feasibility of Docetaxel-Prednisone (DP) in Frail Elderly (Age 75 and Older) Patients with Castration-Resistant Metastatic Prostate Cancer (CRMPC): GERICO10-GETUG P03 Trial Led by Unicancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droz, J.P.; Aapro, M.; Balducci, L.; Boyle, H.; van den Broeck, T.; Cathcart, P.; Dickinson, L.; Efstathiou, E.; Emberton, M.; Fitzpatrick, J.M.; et al. Management of Prostate Cancer in Older Patients: Updated Recommendations of a Working Group of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, e404–e414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Garrido, M.J.; Guillén-Ponce, C. Use of Geriatric Assessment and Screening Tools of Frailty in Elderly Patients with Prostate Cancer. Review. Aging Male 2017, 20, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, F.; Fletcher, K.; Prigerson, H.G.; Braun, I.M.; Maciejewski, P.K. Advanced Cancer as a Risk for Major Depressive Episodes. Psychooncology 2015, 24, 1080–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, S.; Leydon, G.; Birch, B.; Prescott, P.; Lai, L.; Eardley, S.; Lewith, G. Depression and Anxiety in Prostate Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prevalence Rates. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e003901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, A.; Berruti, A.; Cracco, C.; Sguazzotti, E.; Porpiglia, F.; Russo, L.; Bertaglia, V.; Picci, R.L.; Negro, M.; Tosco, A.; et al. Psychological Distress in Men with Prostate Cancer Receiving Adjuvant Androgen-Deprivation Therapy. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2013, 31, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Jim, H.S.; Fishman, M.; Zachariah, B.; Heysek, R.; Biagioli, M.; Jacobsen, P.B. Depressive Symptomatology in Men Receiving Androgen Deprivation Therapy for Prostate Cancer: A Controlled Comparison. Psychooncology 2015, 24, 472–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buigues, C.; Padilla-Sánchez, C.; Fernández Garrido, J.; Navarro-Martínez, R.; Ruiz-Ros, V.; Cauli, O. The Relationship between Depression and Frailty Syndrome: A Systematic Review. Aging Ment. Health 2014, 19, 762–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Number of Patients with mPCa | Pharmacological Treatment | Instruments Used to Measure Frailty and Other Variables | Prevalence of Frailty in Patients with mPCa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hamaya et al., 2021 [16] | 40 | Did not specify. | Frailty was assessed using the G8 screening tool [23]; the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire C30 (QLQ-C30) was also used. | Not reported. |

| Momota et al., 2020 [17] | 96 | The G8 score was assessed at the baseline visit prior to treatment. Some patients with mHNPC and every patient with mCRPC was treated with short-term primary ADT or alternative primary ADT antiandrogen therapy, respectively. | Frailty was assessed using the patient’s G8 score [23], from 0 to 17, with a frailty cut-off point of ≤14. The G8 and Fried phenotypes [2] were used. | In the group with mPCa, 70% of the patients were frail (G8 ≤ 14). |

| Pepa et al., 2017 [19] | 24 | None of the patients had received chemotherapy and they were all about to start docetaxel. Prior treatment included one to four hormonal manipulations. | Frailty evaluated by the 5 domains of the CGA [24]. | 79% of the patients were ‘healthy’ while 21% were ‘frail’. |

| Zakaria et al., 2020 [20] | 75 | Not specified. | A mFI-5 [25] was used at the time of the first stereotactic body radiation therapy treatment. The mFI-5 score was calculated based on the presence of 5 comorbidities. | 77% of the patients had frailty scores > 2. |

| Navarro-Martinez et al., 2019 [21] | 10 | All patients were being treated with ADT. Pharmacological treatment with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogues (bicalutamide, leuprorelin, or triptorelin). | The Fried [2] phenotype criteria were used. | 10% of the patients were classified as frail (meeting ≥ 3 criteria), 60% were pre-frail (meeting 1 or 2 criteria), and 30% were robust. |

| Buigues et al., 2020 [22] | 7 | All the patients were treated with ADT for at least 6 months. Pharmacological treatment with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogues (leuprorelin or triptorelin). | The Fried [2] phenotype criteria were used. | 14.3% of the patients were classified as frail (meeting ≥ 3 criteria), 57.1% were pre-frail (meeting 1 or 2 criteria), and 28.5% were robust. |

| Handforth et al., 2019 [18] | 24 | All of the patients with PCa received ADT, 20 patients (83%) received corticosteroids, 3 patients (12%) had chemotherapy, and 2 patients (4%) received other systemic treatments. | Patient-self reported frailty score (physician assessment and the Rockwood clinical frailty modified scale) [26]. | 54.1% of patients were identified as vulnerable or frail. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mafla-España, M.A.; Torregrosa, M.D.; Cauli, O. Analysis of Frailty Syndrome in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Scoping Review. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13020319

Mafla-España MA, Torregrosa MD, Cauli O. Analysis of Frailty Syndrome in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Scoping Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2023; 13(2):319. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13020319

Chicago/Turabian StyleMafla-España, Mayra Alejandra, María Dolores Torregrosa, and Omar Cauli. 2023. "Analysis of Frailty Syndrome in Men with Metastatic Prostate Cancer: A Scoping Review" Journal of Personalized Medicine 13, no. 2: 319. https://doi.org/10.3390/jpm13020319