Abstract

Background: Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) severely affects the quality of life of affected patients. The development of a shield ulcer is considered one of the most severe late-stage complications, which when untreated leads to irreversible vision loss. In this systematic review, we outlined the results of surgical treatments of corneal shield ulcers in VKC. Methods: We searched 12 literature databases on 3 April 2023 for studies of patients with VKC in which shield ulcers were treated by any surgical treatment. Treatment results were reviewed qualitatively. Assessments of the risk of bias of individual studies were made using the Clinical Appraisal Skills Programme. Results: Ten studies with 398 patients with VKC were eligible for the qualitative review. Two categories of surgical approaches were described: supratarsal corticosteroid injection and debridement with or without amniotic membrane transplantation. Almost all patients experienced resolution or improvement of their shield ulcers, regardless of treatment modality. Time to healing was faster with surgical debridement. A small proportion experienced recurrence and side effects. Conclusions: Surgical treatment for shield ulcers in VKC seems highly effective, but careful post-operative treatment and follow-ups are necessary due to the risk of recurrence and potential side effects.

1. Introduction

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) is a seasonal determined allergic eye disease characterized by hypersensitivity reactions type 1 and 4 [1]. VKC typically occurs in primary school age and predominantly among males, and often resolves after puberty [1,2]. The prevalence of VKC exhibits ethnical differences, as it is more prevalent in Asia, Central and Western Africa, the Middle East, the Mediterranean, and South America than in Western Europe [1,2]. Although treatment and management of VKC has improved over time [3,4,5], severe and complicated cases remain difficult to manage in clinical practice.

Clinically, VKC is typically classified according to its primary area of affection, i.e., tarsal, limbal, or mixed [6]. In tarsal VKC, the tarsal conjunctiva is classically altered, with the presence of chemosis, hyperemia, and giant papillae. In limbal VKC, Horner–Trantas dots can be seen in the corneal limbus as well as punctate keratitis and corneal shield ulcer [2]. The shield ulcer is a corneal wound considered to be the consequence of the combination of a weakened corneal epithelium and the mechanical friction from conjunctival large papillae [1,2]. The patients experience severe symptoms, including pain and photophobia. An untreated shield ulcer leads to increased risk of keratitis, causes corneal scarring, which can lead to severe astigmatism, amblyopia, corneal neovascularization, and in very severe cases, corneal ulceration and perforation. Thus, shield ulcers can lead to blindness and constitute a significant threat to the patients’ quality of life [1,7]. The incidence of shield ulcers in VKC may vary between countries and through different times of the year, with the highest occurrence typically observed in the spring and summer seasons. Shield ulcer has been classified by Cameron according to three categories depending on its severity: grade 1, which has a transparent base; grade 2, which has a translucent base with or without opaque white or yellow deposits; and grade 3, which has an elevated plaque formation [8].

In this systematic review, we evaluated the published literature on the efficacy of surgical treatments for shield ulcers in VKC. Surgical treatments were stratified according to general themes and outcomes with a special emphasis on the remission and recurrence of shield ulcer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This was a systematic review of clinical studies of patients with VKC with shield ulcers who underwent surgical treatment for their shield ulcers. Institutional board review approval is not relevant for systematic reviews, according to Danish law. We followed the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [9].

2.2. Eligibility of Studies for Review

We defined eligible studies as any clinical study of patients with VKC who underwent any surgical treatment for their shield ulcers. Apart from single case studies, we included all retrospective and prospective studies with patients considered to be representative of the general VKC population and sampled them in a relevant and ideally consecutive manner. Any surgical intervention, including any injection therapy, was considered for this review. We only included studies in the English language, for practical purposes. Animal studies, conference abstracts, and publications without original data were not considered relevant for this review.

2.3. Literature Search Strategy and Study Selection

One trained author (Y.S.) searched 12 literature databases on 3 April 2023: PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Central, Web of Science Core Collection, BIOSIS Previews, Current Contents Connect, Data Citation Index, Derwent Innovations Index, KCI-Korean Journal Database, Preprint Citation Index, SciELO Citation Index, and ClinicalTrials.gov. No date restrictions were employed. Details of the literature search for each database are provided in Supplementary File S1.

Two authors (S.A. and Y.S.) screened titles and abstracts of all records to remove records that were duplicates or obviously irrelevant in the context of this review. All remaining references were retrieved as full-text articles to evaluate their potential eligibly for inclusion in the review. The reference lists of these full-text articles were also evaluated for further potentially eligible studies. Two authors (S.A. and M.L.R.R.) evaluated the eligibility of all full-text articles and discussed any disagreements with a third author (Y.S.) to reach a final consensus.

2.4. Data Collection, Outcomes of Interest, Risk of Bias of Individual Studies, and Synthesis

Data regarding study design, study characteristics, population details, treatment employed, and clinical outcomes were extracted from each study using data extraction forms. The main clinical outcome of interest was the clinical recurrence of the shield ulcer after treatment. The risk of bias of individual studies was evaluated using the Clinical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklist for Cohort Studies [10]. Two authors (Y.S. and M.L.R.R.) performed data extraction and risk of bias assessment. If consensus could not be reached through the methods discussed, a third author (S.A.) was involved to reach a final consensus.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and Study Selection

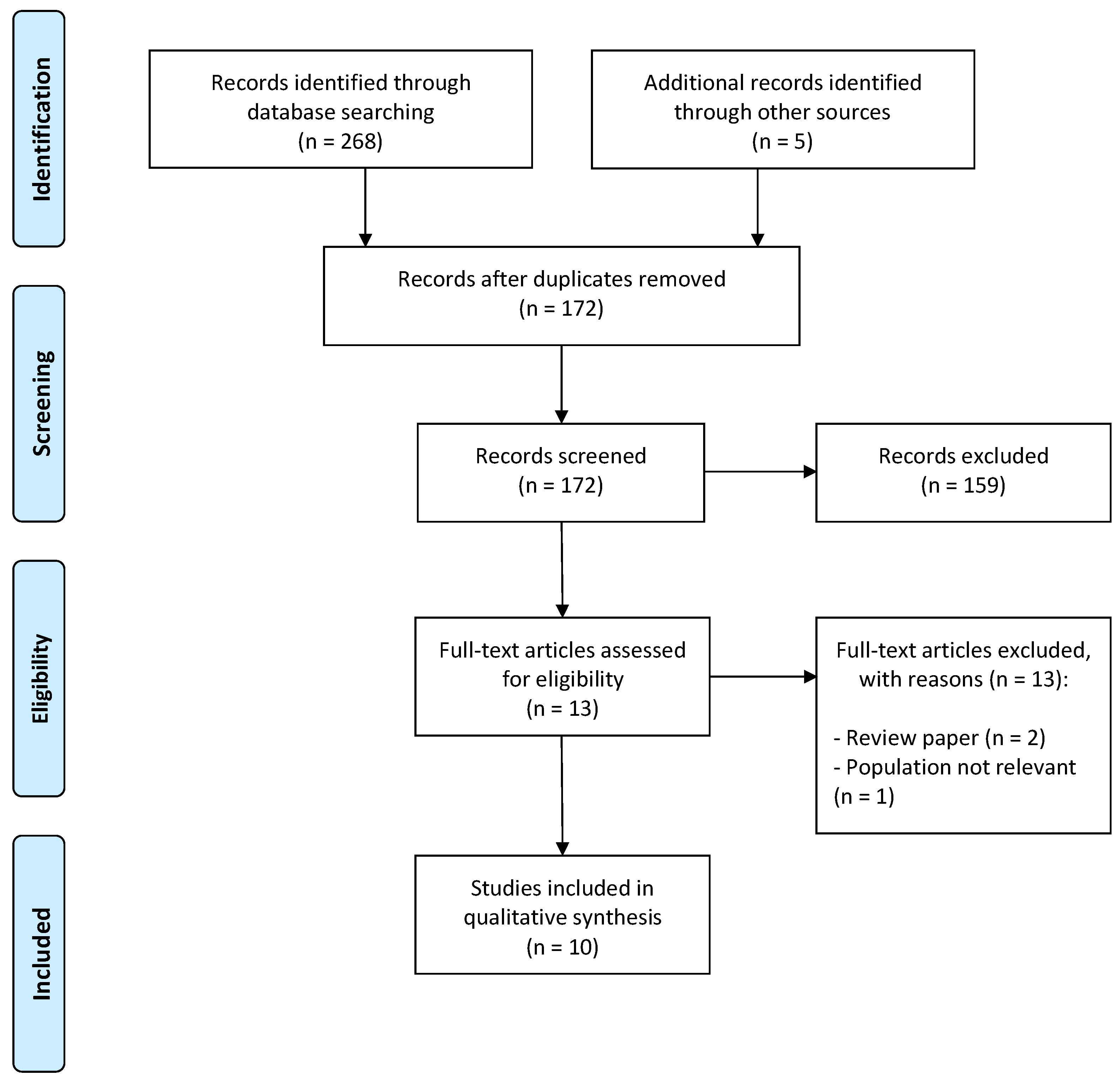

The literature search identified a total of 268 records from all 12 literature databases. Five records were known to us a priori, and these were added to the pool. Of the total of 273 records, 101 were duplicates, and 159 were obviously irrelevant (e.g., title or abstract clearly irrelevant for VKC or the treatment of shield ulcer). The remaining 13 records were evaluated in full-text form. Of these, 10 full-text articles were deemed eligible for our systematic review [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Figure 1 depicts the study selection flow diagram.

Figure 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart for study selection.

3.2. General Study Characteristics

The 10 eligible studies included in this review had a total of 398 patients with VKC. Study populations originated from India (n = 7), Italy (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 1), and the United States of America (n = 1). Studies were either cases followed in a prospective or retrospective cohort design (n = 6) or randomized clinical trials (n = 4). The sizes of the populations in the individual studies were: median 19, interquartile range 8–47, range 4–163. Patients were predominantly pediatric (defined as below 18 years of age). In all studies, patients were either predominantly males or exclusively males. Surgical treatment was largely categorized into surgical intervention with corticosteroid injections and surgical intervention with debridement. Further details of studies included in this review, as well as details of the shield ulcers included, are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study and population characteristics.

3.3. Results after Surgical Intervention with Corticosteroid Injections

Six studies evaluated results after surgical intervention with corticosteroid injections from a total of 142 patients. Follow-up was available for at least 4 months and up to 48 months. Details of treatment and outcomes from these studies are briefly summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies of corticosteroid injections for shield ulcer in vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC).

Anand et al. compared supratarsal injection of triamcinolone (20 mg) with 0.1% cyclosporine/triamcinolone and topical difluprednate [11]. Seventy-eight patients were stratified into three groups with twenty-six patients in each. Supratarsal injection of triamcinolone led to the best outcome of the three groups, with resolution of the shield ulcer occurring in 97% of patients [11].

Aslam et al. examined the efficacy of supratarsal injection of triamcinolone in severe VKC. Eighteen patients were included in the study and received 20 mg triamcinolone each [12]. Resolution of shield ulcer was observed in 20% within one to three weeks after commencement of treatment [12].

Two studies compared the efficacy of supratarsal injection with either dexamethasone or triamcinolone. Horsclaw et al. compared the outcomes after supratarsal injection of either dexamethasone (4 mg/mL) or triamcinolone (40 mg/mL) in 12 patients [14]. This study found no significant difference in the resolution of shield ulcer, which led to the discussion of considering the shorter-acting dexamethasone due to its more favorable overall safety profile [14]. Saini et al. compared the outcomes after supratarsal injection with either dexamethasone (2 mg) or triamcinolone (20 mg) in 19 patients [17]. All cases of shield ulcer were healed, and no differences were found between the groups [17].

Two other studies compared the efficacy of supratarsal injection with either dexamethasone, triamcinolone, or hydrocortisone. Kumar et al. compared the outcomes after supratarsal injection with either dexamethasone (2 mg), triamcinolone (10.5 mg), or hydrocortisone (50 mg) in 48 patients [15]. However, only 8 had shield ulcer, and at 3 weeks all cases of shield ulcer were healed [15]. Singh et al. compared the outcomes after supratarsal injection with either dexamethasone (2 mg), triamcinolone (10.5 mg), or hydrocortisone (50 mg) [19]. Resolution of shield ulcer was observed after 3 weeks for all cases regardless of treatment [19].

3.4. Results after Surgical Intervention with Debridement

Six studies evaluated results after surgical intervention with debridement from a total of 171 patients. Follow-up was available for at least 2–25 months in studies that reported follow-up periods. Details of treatment and outcomes from these studies are briefly summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Studies of corticosteroid injections for shield ulcer in vernal keratoconjunctivitis (VKC).

Caputo et al. performed surgical debridement on four patients with shield ulcers [13]. Ulcer plaques were scraped using a crescent knife and the epithelium was removed up to 1 mm around the plaque, leaving the surface of the corneal stroma as smooth as possible [13]. Patients received cyclosporine treatment after surgery until complete remission, which was achieved within 4–5 days [13].

Reddy et al. treated 163 patients (193 eyes) with shield ulcers with either medical treatment or by performing surgical debridement [16]. In cases with surgical debridement, each ulcer was scraped at its base and in its margin, and in patients who did not show signs of re-epithelization within 2 weeks, an amniotic membrane transplantation was performed [16]. During a relatively long follow-up period of 544 ± 751 days, 118 eyes (61%) were managed medically, and 75 eyes (39%) underwent surgical debridement, of which 44 also had amniotic membrane transplantation [16]. This strategy led to an overall rate of resolution of 94%, with 15% experiencing recurrence during the follow-up period [16].

Sharma et al. performed a modified surgical technique of continuous intraoperative optical coherence tomography-guided shield ulcer debridement and amniotic membrane transplantation on four patients [18]. The benefit of this technique is described as being able to visualize any residual plaque as a hyperreflective membrane and dots, thus being able to obtain real-time feedback to ensure the complete removal of the ulcer [18]. Resolutions were obtained within 7–12 days [18].

Sridhar et al. performed surgical debridement and amniotic membrane transplantation in four patients, of which two also received supratarsal injection with corticosteroids [20]. The plaque was removed, the ulcer bed was thoroughly debrided, and the amniotic membrane was positioned over the epithelial defect [20]. All cases experienced resolution within 2 weeks [20].

3.5. Risk of Bias of Individual Studies

Risk of bias of individual studies showed that studies generally addressed a focused issue, recruited in an acceptable way, and accurately described the treatments employed (exposure). Measurement of the outcome when using definitions of shield ulcer was unclear in all studies apart from two. Identification and addressing of potential confounding factors were only performed in four studies, which were all randomized clinical trials. An adequate follow-up period after surgical treatment of shield ulcer was considered to be at least three months, and this was present in all but two studies. Details of the evaluation of the risk of bias of individual studies are available as Table 4.

Table 4.

Risk of bias of individual studies using the Clinical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Checklist.

4. Discussion

Our systematic review highlights the overall beneficial results from both supratarsal injection with corticosteroids and surgical debridement as nearly all obtain remission. However, findings of the studies and the necessity of intense postoperative eyedrop regimens and controls also highlight that the management of this severe type of VKC can be complicated.

The mechanism of action of supratarsal corticosteroid injection relies on a general suppression of the local immune system. The rapid reduction in giant papilla formation helps prevent direct mechanical trauma, while deactivating the toxic major basic proteins released by activated eosinophils within the shield ulcer debris, thereby creating a favorable environment for corneal epithelial healing [16]. Studies in this review found that corticosteroid injections have high efficacy in the treatment of shield ulcer. The average time required for healing across the studies was consistently within the range of 2–3 weeks. Interestingly, the specific type of corticosteroid used did not seem to significantly affect the healing of shield ulcers. This contrasts with the general knowledge that specific corticosteroids have different potencies [21]. Relative to each other, a ranking order of potency (from highest to lowest) is dexamethasone, triamcinolone, and hydrocortisone [21]. However, these potency-related pharmacological aspects, including side effects, such as systemic absorption with the concern of potential adrenal insufficiency and inhibition of growth hormones, remain poorly understood when given supratarsal or topical on the conjunctiva [22]. Ocular side effects of corticosteroid injections are generally well-described and also seen in studies of this review. In two studies [11,14], 6–8% of patients experienced elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) for months following triamcinolone injections.

Recurrence of the shield ulcer may be influenced by the type of glucocorticoid used [17]. This was demonstrated by Saini et al., in which both dexamethasone and triamcinolone injections led to complete resolution of shield ulcer; however, the recurrence of shield ulcer occurred after 6–20 days after dexamethasone treatment, whereas the recurrence occurred after 180–290 days after triamcinolone treatment [17]. This difference highlights the known pharmacodynamic differences between dexamethasone and triamcinolone, i.e., triamcinolone is more long-acting [21].

Surgical debridement led to faster healing, either with or without amniotic membrane transplantation. Time to healing ranged within 4–17 days. Since debridement involves the removal of the dense plaque tissue, one can speculate about the removal of this plaque, which is likely composed of cytotoxic eosinophilic granule major basic proteins [16,23]; removal of these proteins from the local milieu can hasten the healing and re-epithelialization process.

Among the included studies, one study exclusively performed surgical debridement [13]. The remaining three studies [16,18,20] utilized a combination of debridement, amniotic membrane transplantation, and supratarsal corticosteroid injections. Two studies employed a stepwise approach, with the most severe cases of grade 3 shield ulcer receiving debridement, amniotic membrane transplantation, and supratarsal corticosteroid injections using dexamethasone [16,20]. The post-operative treatment varied among the studies but generally involved a combination of the following: topical antibiotic treatment for the initial weeks, often with fluoroquinolones or moxifloxacin; topical corticosteroids, topical cyclosporine, and lubricating eyedrops, and topical cromoglycate. These treatment modalities aimed to address the shield ulcer and to prevent its recurrence [13,16,18,20]. However, despite intense topical postsurgical treatment, Reddy et al. reported recurrence rates of 13–14% in a large Indian population, even with a stepwise treatment approach [16]. Complications reported in the studies include secondary bacterial keratitis (10%), disintegration of the amniotic membrane, and corneal scarring [16,20]. It is important to note that in the context of a severe shield ulcer of grade 3, corneal scarring may be considered a natural progression rather than a distinct complication.

Limitations of this review should be noted when interpreting its results. Eight of ten studies in this review are from India and Pakistan, which challenges the generalizability of results to other populations. However, this also reflects the epidemiology of the disease, as VKC and shield ulcer are more commonly observed in tropical regions such as India, Pakistan, central Africa, and certain Middle Eastern countries. The specific factors responsible for this epidemiological phenomenon are not fully understood; however, a hot and humid climate or increased exposure to airborne allergens are speculated to be contributing factors [24]. Another important limitation is that none of the studies had a placebo or an observation group, which makes it difficult to estimate the efficacy of these treatment modalities. However, considering that patients are severely symptomatic and the reports of the natural history of shield ulcer without treatment, it would be ethically challenging to design a study with a group that does not receive the standard of care. Further studies on the treatment of shield ulcers are warranted.

It should also be noted that there are important adjacent aspects of shield ulcer management that are not included in this review. First, the use of cyclosporine and tacrolimus before and after surgery may facilitate the recovery process [25]. In general, for VKC, and especially in the presence of any corneal complication, the patient and the parents should be advised to achieve control of ocular rubbing, as it plays an important role in the etiology of progression. Finally, from a surgical perspective, the use of intraoperative anterior segment OCT may allow for a more precise depth of debridement and placement of an amniotic graft [18].

In conclusion, we here report the efficacy of surgical treatments of corneal shield ulcers in VKC. Overall, two major approaches are available: supratarsal corticosteroid injection, and debridement with or without amniotic membrane transplantation. The utilization of the Cameron grading system to assess the severity of shield ulcers provides a reasonable method to distinguish between shield ulcers in a clinically meaningful manner. Using the Cameron grading system, our review suggests that grade 1 shield ulcers can be treated using topical steroids or supratarsal injection of corticosteroids, whereas grade 2 and 3 shield ulcers may need debridement +/- supratarsal injection of corticosteroids as well as amniotic membrane transplantation over the debridement in cases with deep stromal involvement to increase the speed of healing.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jpm13071092/s1, Supplementary File S1: Details of literature search across databases.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A., Y.S. and M.L.R.R.; methodology, Y.S. and M.L.R.R.; software, Y.S. and M.L.R.R.; formal analysis, S.A., Y.S. and M.L.R.R.; resources, Y.S. and M.L.R.R.; data curation, S.A., Y.S. and M.L.R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.S. and M.L.R.R.; writing—review and editing, S.A., Y.S. and M.L.R.R.; supervision, M.L.R.R.; project administration, M.L.R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Feizi, S.; Javadi, M.A.; Alemzadeh-Ansari, M.; Arabi, A.; Shahraki, T.; Kheirkhah, A. Management of corneal complications in vernal keratoconjunctivitis: A review. Ocul. Surf. 2021, 19, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, D.; Sahay, P.; Maharana, P.K.; Raj, N.; Sharma, N.; Titiyal, J.S. Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis. Surv. Ophthalmol. 2019, 64, 289–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.L.R.; Schou, M.G.; Bach-Holm, D.; Heegaard, S.; Jørgensen, C.A.B.; Kessel, L.; Wiencke, A.K.; Subhi, Y. Comparative efficacy of medical treatments for vernal keratoconjunctivitis in children and young adults: A systematic review with network meta-analyses. Acta Ophthalmol. 2022, 100, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, M.L.R.; D’Souza, M.; Topal, D.G.; Gradman, J.; Larsen, D.A.; Lehrmann, B.B.; Kjaer, H.F.; Kessel, L.; Subhi, Y. Prevalence of allergic sensitization with vernal keratoconjunctivitis: A systematic review with meta-analyses. Acta Ophthalmol. 2023, 101, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, M.L.R.; Larsen, A.C.; Subhi, Y.; Potapenko, I. Artificial intelligence-based ChatGPT chatbot responses for patient and parent questions on vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Graefe’s Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2023; epub ahead of printing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonini, S.; Sacchetti, M.; Mantelli, F.; Lambiase, A. Clinical grading of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 7, 436–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Rana, J.; Kataria, S.; Bhan, C.; Priya, P. Demographic and clinical characteristics of childhood and adult onset Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis in a tertiary care center during COVID pandemic: A prospective study. Rom. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 66, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cameron, J.A. Shield ulcers and plaques of the cornea in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology 1995, 102, 985–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available online: https://casp-uk.net (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- Anand, S.; Varma, S.; Sinha, V.B. A comparative study on uses of supratarsal triamcinolone injection, topical steroids and cyclosporine in cases of refractory vernal keratoconjunctivitis. J. Evol. Med. Dent. Sci. 2017, 6, 1129–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, S.; Arshad, M.; Khizar, M. Efficacy of Supratarsal Injection of Triamcinolone Acetonide (Corticosteroid) for treating severe Vernal Keratoconjunctivitis (VKC) refractory to all Conventional Therapy. Pak. J. Med. Health Sci. 2017, 11, 656–658. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo, R.; Pucci, N.; Mori, F.; De Libero, C.; Di Grande, L.; Bacci, G.M. Surgical debridement plus topical cyclosporine A in the treatment of vernal shield ulcers. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2012, 25, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holsclaw, D.S.; Whitcher, J.P.; Wong, I.G.; Margolis, T.P. Supratarsal injection of corticosteroid in the treatment of refractory vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1996, 121, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, R.K. A Study on the Supratarsal Injection of Corticosteroids in the Treatment of Refractory Vernal Keratoconjuctivitis. Int. J. Pharm. Clin. Res. 2022, 14, 325–330. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, J.C.; Basu, S.; Saboo, U.S.; Murthy, S.I.; Vaddavalli, P.K.; Sangwan, V.S. Management, clinical outcomes, and complications of shield ulcers in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2013, 155, 550–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, J.S.; Gupta, A.; Pandey, S.K.; Gupta, V.; Gupta, P. Efficacy of supratarsal dexamethasone versus triamcinolone injection in recalcitrant vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 1999, 77, 515–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, N.; Singhal, D.; Maharana, P.K.; Jain, R.; Sahay, P.; Titiyal, J.S. Continuous intraoperative optical coherence tomography-guided shield ulcer debridement with tuck in multilayered amniotic membrane transplantation. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 66, 816–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Pal, V.; Dhull, C.S. Supratarsal injection of corticosteroids in the treatment of refractory vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Indian J. Ophthalmol. 2001, 49, 241–245. [Google Scholar]

- Sridhar, M.S.; Sangwan, V.S.; Bansal, A.K.; Rao, G.N. Amniotic membrane transplantation in the management of shield ulcers of vernal keratoconjunctivitis. Ophthalmology 2001, 108, 1218–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Ahmet, A.; Ward, L.; Krishnamoorthy, P.; Mandelcorn, E.D.; Leigh, R.; Brown, J.P.; Cohen, A.; Kim, H. A practical guide to the monitoring and management of the complications of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2013, 9, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, D.C.; Kessel, L.; Bach-Holm, D.; Main, K.M.; Larsen, D.A.; Bangsgaard, R. Prevalence and risk factors for hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression in infants receiving glucocorticoid eye drops after ocular surgery. Acta Ophthalmol. 2023, 101, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, K.R.; Ackerman, S.J. Eosinophil granule proteins: Form and function. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 17406–17415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonardi, A.; Busca, F.; Motterle, L.; Cavarzeran, F.; Fregona, I.A.; Plebani, M.; Secchi, A.G. Case series of 406 vernal keratoconjunctivitis patients: A demographic and epidemiological study. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 2006, 84, 406–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdinest, N.; Ben-Eli, H.; Solomon, A. Topical tacrolimus for allergic eye diseases. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2019, 19, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).