Abstract

Schizophrenia is one of the most disabling of the psychiatric diseases. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Extended (BRSE) is used to evaluate the severity of psychiatric symptoms. Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics are commonly used and are preferred over oral antipsychotic medications. A two-center-based cross-sectional study was performed on 130 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder based on the International Classification of Diseases 10 criteria. We studied the relation between the development of cardiovascular risk factors and the antipsychotic medication that was administered in these patients. Our study demonstrates strong links between several cardiovascular risk factors and the duration of psychosis; the duration of the LAI antipsychotic treatment; the duration between the onset of the disease and the start of LAI antipsychotic treatment; and the use of specific LAI antipsychotic medications.

1. Introduction

Schizophrenia is a serious psychiatric disorder where the ability to exhibit clear thinking is affected, along with the tendency to act or behave normally or to feel. It is one of the most common mental illnesses found in day-to-day practice [1,2]. The early development of the brain is affected due to heterogeneous genetic abnormalities and neurobiological changes [3]. The main key symptoms include hallucinations, disordered thoughts, delusions, a lack of motivation to accomplish goals, disturbances in sleep patterns, slow movements, motor and cognitive impairments, poor grooming, poor hygiene, changes in body language and emotions, and difficulties in maintaining social relationships. Although the symptoms differ from case to case, they can be grouped into three broad categories: positive (psychotic), negative (deficits), and cognitive [2]. Usually, patients suffering from this mental disorder are diagnosed in adolescence or early adulthood. Monitoring developmental milestones can help to identify children suffering from this illness at a much younger age. Moreover, inappropriate or unusual behaviors, together with cognitive impairment, are present in childhood but are often missed by the family and pediatricians or family doctors [3,4]. The presence of multiple symptoms indicates the advancement of the disease to a severe stage. Early life stress or parental factors that affect the environment of the child may lead to disruptions in the development of the brain, which, if left untreated, may lead to severe forms of schizophrenia.

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Extended (BRSE) is frequently used in psychiatric cases to evaluate the severity of psychiatric symptoms. The scale is based on a doctor-to-patient interview and includes an evaluation of different behavioral patterns observed during the past 2–3 days. The patient’s family observation reports can also be considered. It is a points-based questionnaire, with scores ranging from 0 to 7 points for every question. A score of “0” is negative or indicates the absence of symptoms and “7” denotes the presence of extremely severe symptoms [5].

In a meta-analysis conducted by K. Hagi et al. [6], the existence of an association between schizophrenia patients having metabolic syndrome, hypertension, or diabetes and cognitive impairment was described. Cardiovascular risk factors play an important role, leading to cognitive decline in psychosis cases. Premature mortality is commonly witnessed in psychiatric patients, with the predominant culprit being the cardiovascular system.

Medications used to treat schizophrenia can help to control the psychotic symptoms but are not very effective in improving the occupational, cognitive, or social functioning of the patient. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), cognitive remediation (CR), and support systems for education and employment are some of the psychosocial interventions that can help to improve the overall outcomes. Since there is a significant delay in diagnosis, in order to treat patients efficiently for risk mitigation, a global strategic approach is required, involving a psychiatrist and psychotherapist, along with the support of the family and the family physician.

Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics are preferred nowadays to overcome patient treatment adherence issues, which are witnessed with oral antipsychotic medications. LAI antipsychotics ensure a sustained effect upon target neuroreceptors that transmit specific neurochemicals, and this forecloses the need for oral medications on a regular basis, an aspect that patients diagnosed with schizophrenia and related conditions often find difficult. The benefit is that they allow the slow release of the drug into the bloodstream, which helps in reducing the frequency of administration. Risperidone, olanzapine, aripiprazole, and paliperidone are all frequently used LAI antipsychotics that are approved by the FDA and are named second-generation LAI antipsychotics. Nine different forms are available of these four drugs. These injections are costly but worthwhile as not only do they help in treatment adherence but they also improve patient outcomes. The route of administration is intramuscular and, differing with the drug preparation, gluteal or deltoid, with the latter providing better absorption. Similarly, the effectiveness of each shot can vary from weeks to months depending on the different preparations [7].

The commencement of LAIs in patients may be delayed due to certain reasons, such as a lack of information regarding the drug’s pharmacokinetics and dose selection [8], an overestimation of patient adherence to OA [9], and a lack of knowledge and updates regarding the benefits of second-generation LAI antipsychotics versus first-generation drugs, as well as oral antipsychotics [10,11]. Antipsychotics are lipophilic drugs and hence some drug is stored in the body’s lipid deposits, which may accumulate over time [12]. This is of concern since any adverse effect that appears after LAI administration will likely persist over a longer duration. As a discouraging aspect, there is evidence of injection-related adverse events and overall negative perceptions of the safety of LAI versus oral antipsychotics (OA) due to the slightly higher occurrence of extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia in LAI [13,14]. However, the perceived safety of OA use is also countered by their poor adherence and underdosing [15].

Mental illness in the form of schizophrenia and its range of symptoms has an adverse impact on patients’ cognition, behavior, and emotions, as well as on the performance of daily life activities [16]. There is a fivefold higher risk of cardiovascular mortality and sudden cardiac death (SCD) in patients with SMI [17]. This holds true across both sexes, all ages, and all ethnic groups [18]. Surprisingly, the death rates related to cardiovascular conditions in patients suffering from schizophrenia and other mental illnesses have been increasing [19]. This calls for attention to and a focus on analyzing the link between schizophrenia’s evolution, treatment, and cardiovascular risks.

2. Material and Methods

We performed a two-center-based (Timisoara and Cluj, Romania) cross-sectional study on 130 patients that presented to our ambulatory services and were diagnosed with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorders. Patients were diagnosed based on the International Classification of Diseases 10 criteria. Patients with a recent acute psychotic episode in the last 2 months (decompensated), patients with oral antipsychotic medication (compliance with medication may be questionable), and patients with a previously diagnosed cardiovascular disease were excluded. Patients who were placed on more than one LAI and those who were given multiple LAIs over their medication history were also excluded from this study.

The following parameters were evaluated for the entire group of patients: demographic data, clinical data (age of onset of psychosis, duration of psychosis, duration of injectable antipsychotic treatment, and duration of pre-LAI treatment), and the severity of the psychiatric symptoms using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale Extended (BRSE), as well as data after clinical examination and paraclinical findings (blood tests, electrocardiogram, echocardiography, and speckle tracking analysis).

The IBM Statistics for Windows program, version 20, was used to analyze the data. As the Shapiro–Wilk test for normality of distribution showed a non-Gaussian distribution of the data, differences between groups were checked using non-parametrical tests (the Kruskal–Wallis test). Potential associations between the symptoms, the duration of the disease, and the cardiac EF were assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficients. For all statistical tests, the level of significance was considered 0.05 and all results were two-tailed.

The study was approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania (approval number 19/2015) and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained as a part of the routine procedure from all patients/relatives/legal caretakers undergoing treatment at our university hospitals for further research and educational purposes.

3. Results

Cardiovascular risk factors were studied in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, depending on the type of medication that was administered.

The entire group of patients was divided into four subgroups, depending on the LAI antipsychotic medication administered to them, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical data regarding the duration of psychosis depending on the administered medication (LAI: long-acting injectable).

Table 2 shows the number of patients in each dosage category for each antipsychotic drug. It is evident that most patients were prescribed olanzapine (N = 38), with the most dose variations (four), and there was a single dosage pattern with regard to prescribing aripiprazole, i.e., 400 mg/month.

Table 2.

Number of patients in each dosage category for each antipsychotic drug.

Table 3 shows the number of months that passed since the onset of psychosis, the months since LAI treatment initiation, and the gap between the onset of psychosis and the initiation of LAI among the different age groups.

Table 3.

Number of months passed since onset of psychosis, months since LAI treatment initiation, and gap between onset of psychosis and initiation of LAI among different age groups.

Table 4 shows the number of patients in each age group that were given LAI antipsychotics, with most patients receiving olanzapine.

Table 4.

Number of patients in each age group that were given LAI antipsychotics, with most patients receiving olanzapine.

When using the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by the Dunn–Bonferroni post hoc test, we found no significant differences between the four groups regarding the

- Age (p = 0.27);

- Age at the onset of the disease (p = 0.11);

- Total duration of the disease (p = 0.38);

- Duration of pre-LAI antipsychotic treatment (p = 0.52).

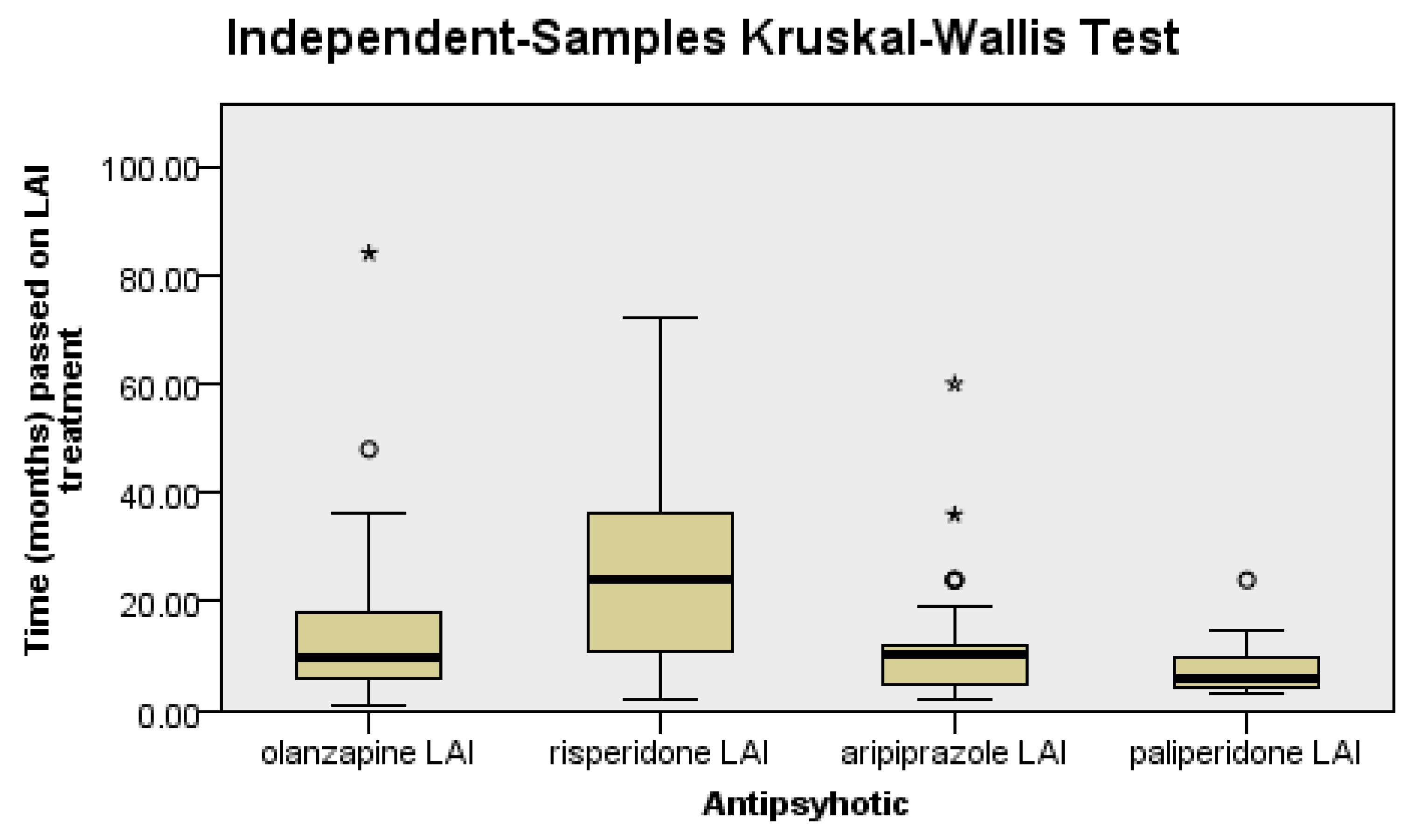

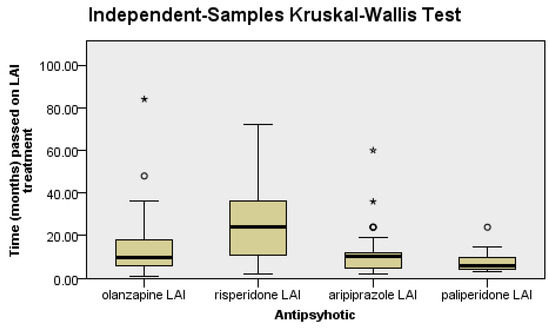

There were significant differences between the groups regarding the LAI antipsychotic treatment duration (p < 0.0001), as follows: patients on risperidone had a significantly longer LAI antipsychotic treatment duration than patients on olanzapine (p = 0.04), aripiprazole (p = 0.03), or paliperidone (p < 0.0001), since it was the first LAI second-generation antipsychotic introduced in clinical practice (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Risperidone patients have a longer duration of treatment than the rest of the patients.

Data regarding various cardiovascular risk factors are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Data regarding the cardiovascular risk factors.

Cardiovascular risk factors depending on the medications consumed are represented in Table 6. No significant differences were found between the four groups regarding the presence of abdominal obesity (χ2 = 2.39, p = 0.49).

Table 6.

Cardiovascular risk factors depending on the medication administered.

Similarly, no significant differences were found between the four groups regarding the presence of hypertension (χ2 = 2.67, p = 0.44).

Significant differences were also not found between the four groups regarding the presence of hypertriglyceridemia (χ2 = 3.82, p = 0.28).

There were statistically significant differences witnessed between the groups in terms of hyperglycemia (χ2 = 13.43, p = 0.004): patients on olanzapine and risperidone had significantly more frequent hyperglycemia compared to those on aripiprazole or paliperidone.

There were statistically significant differences noted between all four groups regarding hypo-HDL (χ2 = 17.80, p < 0.0001): patients on olanzapine and risperidone had significantly more frequent hypo-HDL compared to those on aripiprazole or paliperidone.

There were no significant differences between the four groups regarding smoking habits (χ2 = 1.45, p = 0.69).

Regarding echocardiographic changes, we found the following.

There were statistically significant differences between the four groups regarding the presence of hypokinetic disorders (χ2 = 8.98, p = 0.03): patients on risperidone presented significantly more frequent hypokinetic disorders compared to those on olanzapine, aripiprazole, or paliperidone; see Table 7.

Table 7.

Changes in kinetics depending on the medication administered.

There were no significant differences between the four groups regarding the presence of valvular dysfunction (χ2 = 12.82, p = 0.61) and also no significant differences between the four groups regarding the presence of pulmonary hypertension (χ2 = 5.45, p = 0.14), but there were statistically significant differences between the four groups regarding the presence of diastolic dysfunction (χ2 = 8.77, p = 0.03): patients on risperidone and aripiprazole presented significantly more frequent diastolic dysfunction compared to those on olanzapine or paliperidone.

Regarding the duration of the psychosis, the duration of the antipsychotic treatment, and the duration between the onset of the disease and the start of the antipsychotic treatment, the following were found.

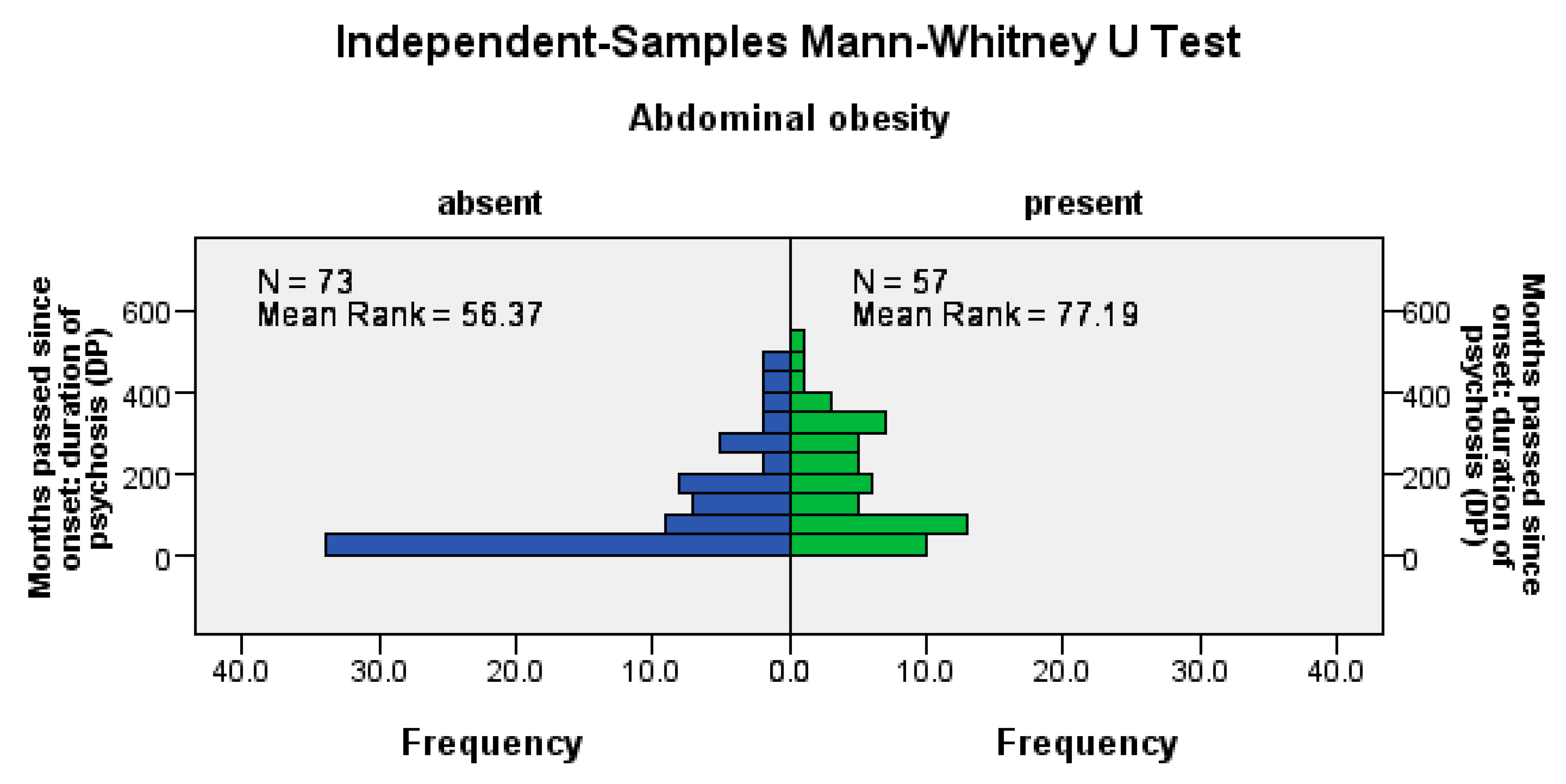

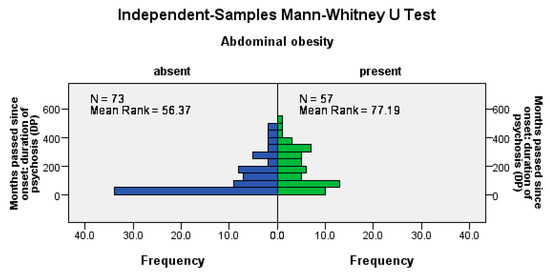

Abdominal obesity was significantly more frequent among patients with a longer psychosis duration (U = 1414, Z = −3.13, p = 0.002), among patients with a longer LAI antipsychotic duration (U = 1515, Z = −2.66, p= 0.008), and among those with a longer pre-LAI antipsychotic duration (U = 1474, Z = −2.85, p = 0.004); see Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Abdominal obesity correlates positively with the duration of the disease, the time before the start of the antipsychotic treatment, and the duration of the antipsychotic treatment.

Hyperglycemia was significantly more frequent among patients with a longer LAI antipsychotic duration (U = 1267, Z = −3.25, p = 0.001), with no significant differences between patients with a longer DP and those with a shorter DP regarding hyperglycemia (p = 0.08) and with no significant differences between patients with a longer pre-LAI antipsychotic duration and those with a shorter pre-LAI antipsychotic duration regarding hyperglycemia (p = 0.16).

HTN was significantly more frequent among patients with a longer pre-LAI antipsychotic duration (U = 2326, Z = −2.35, p = 0.04). There were significant differences between patients with a longer DP and those with a shorter DP regarding HTN (p = 0.55) but no significant differences between patients with a longer LAI antipsychotic duration and those with a shorter LAI antipsychotic duration regarding HTN (p = 0.45).

No significant differences were found between patients with a longer DP, pre-LAI antipsychotic duration, and LAI antipsychotic duration and those with a shorter DP, pre-LAI antipsychotic duration, and LAI antipsychotic duration regarding the frequency of hypertriglyceridemia (p > 0.05), regarding the frequency of hypo-HDL cholesterol (p > 0.05), and in terms of the smoking frequency (p > 0.05).

Concerning the correlation between the duration of psychosis, the time before the start of the antipsychotic treatment, and the duration of LAI antipsychotic treatment and echocardiographic changes, we can state the following.

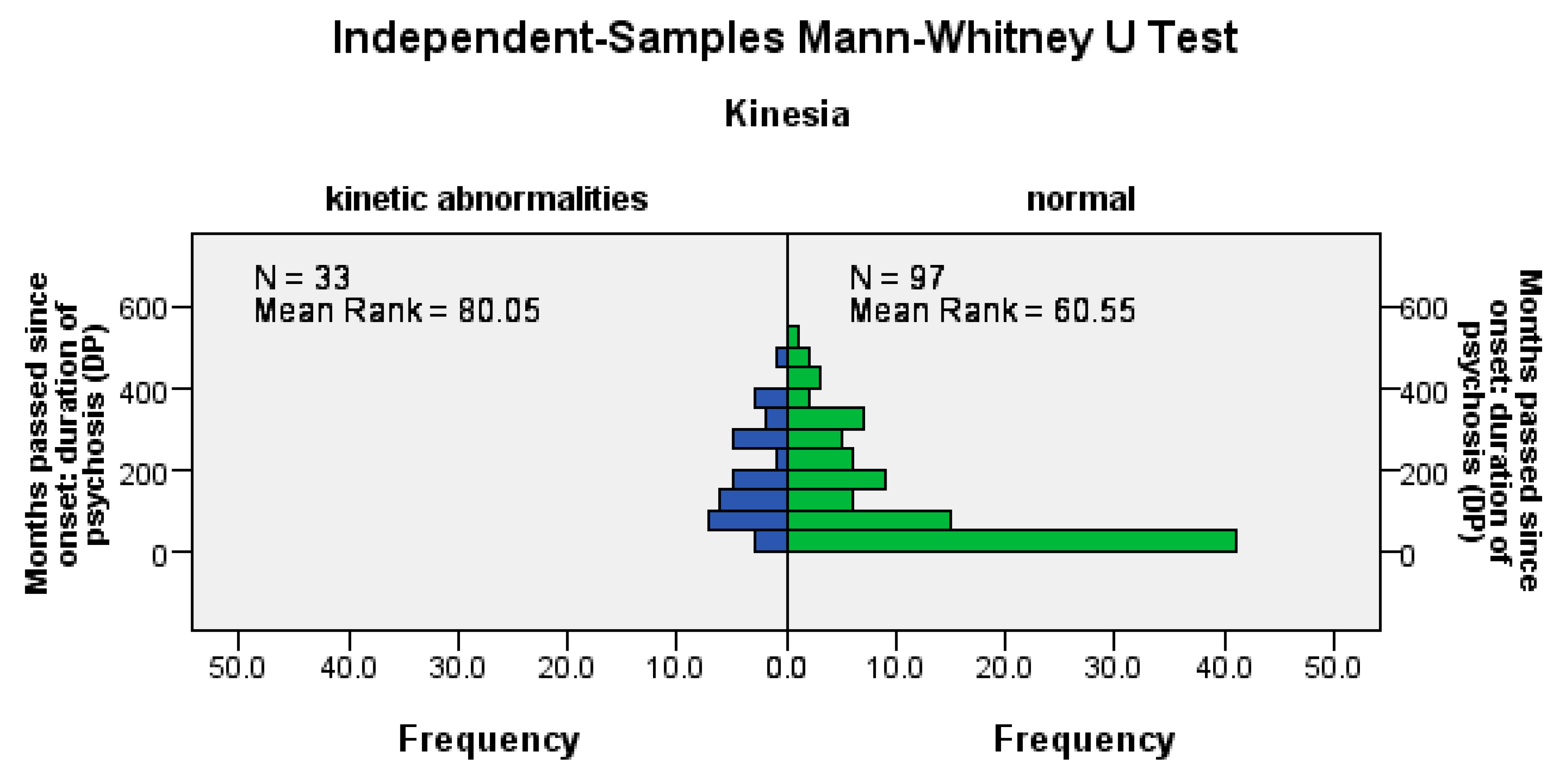

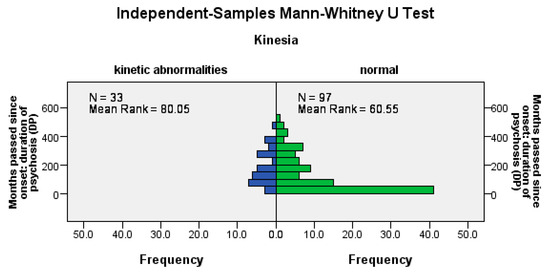

Hypokinesia disorders were significantly more frequent among patients with a longer DP (U = 1120.5, Z = −2.57, p = 0.01), among patients with a longer LAI antipsychotic duration (U = 1162.5, Z = −2.66, p= 0.02), and among those with a longer pre-LAI antipsychotic duration (U = 1178, Z = −2.26, p = 0.02); see Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The occurrence of hypokinetic disorders correlates positively with the duration of the disease, the time before the start of the LAI antipsychotic treatment, and the duration of the treatment.

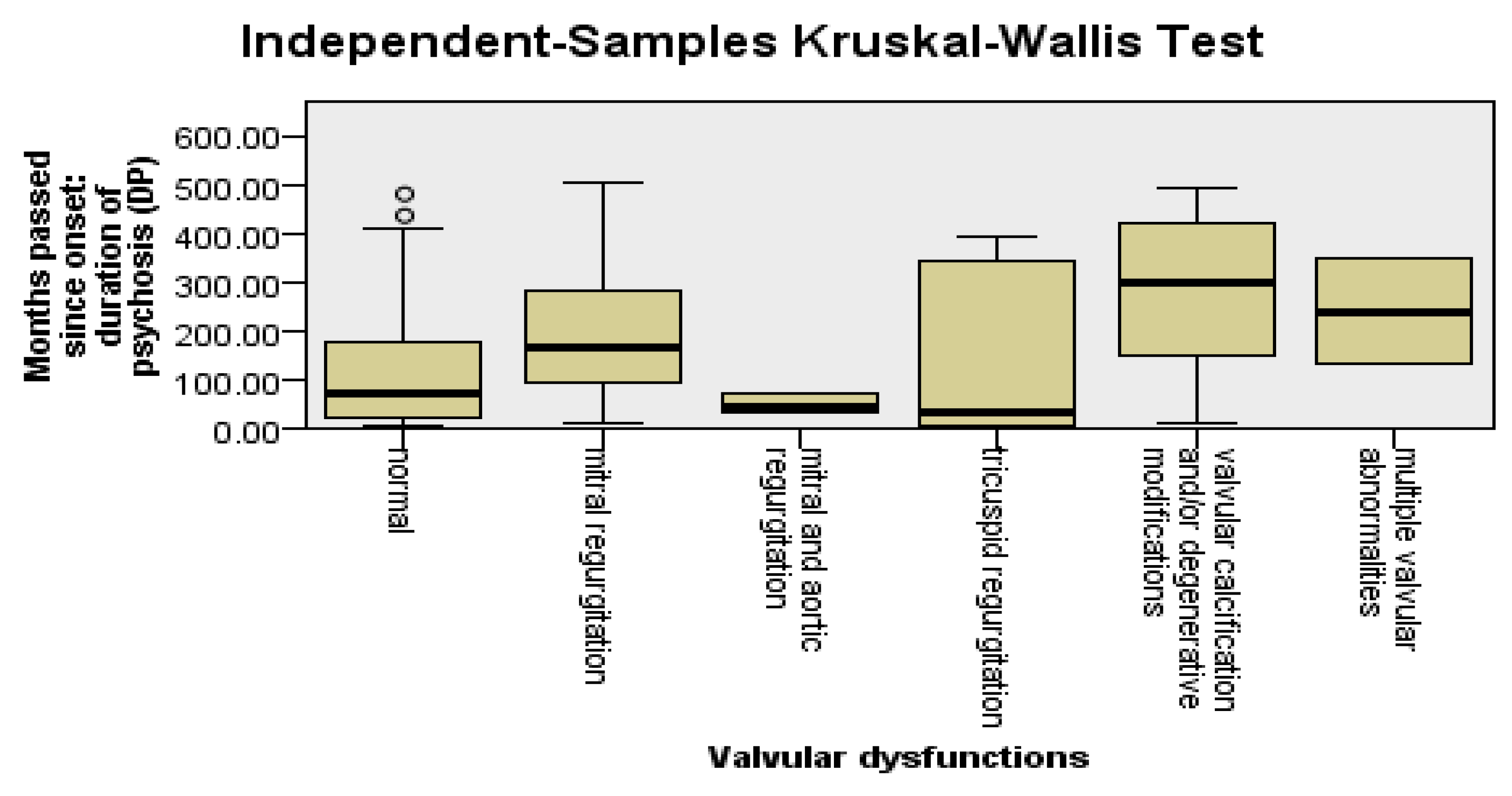

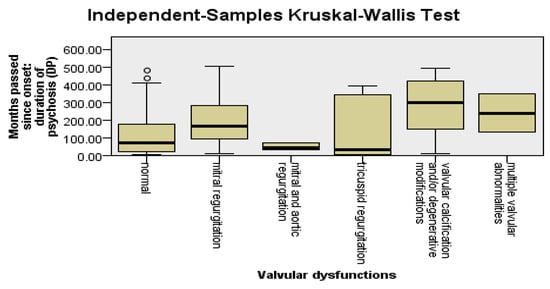

Valvular changes were significantly more frequent among patients with a longer pre-LAI antipsychotic duration (U = 1352, Z = −3.16, p = 0.002). Valvular changes were significantly more frequent among patients with a longer DP (U = 1375, Z = −3.05, p = 0.002). No significant differences were found between patients with a longer LAI antipsychotic duration and those with a shorter LAI antipsychotic duration regarding the presence of valvular changes (p = 0.52).

To detect the types of valvular changes that were more frequent among patients with DP and a longer pre-LAI antipsychotic duration, we applied the Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by the Dunn–Bonferroni post hoc test. Mitral regurgitation was found to be significantly more frequent among patients with DP (p = 0.03) and the pre-LAI antipsychotic duration (p = 0.03) was longer. The other types of valvular changes did not have statistically significant relevance in relation to DP, the pre-LAI antipsychotic duration, or the LAI antipsychotic duration; see Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Valvular changes are more frequent among patients with DP and a longer pre-LAI antipsychotic duration.

Diastolic dysfunction was significantly more frequent among patients with a longer pre-LAI antipsychotic duration (U = 925, Z = −4.68, p < 0.0001). Diastolic dysfunction was significantly more frequent among patients with a longer DP (U = 911.5, Z = −4.75, p < 0.0001). There were no significant differences between patients with a longer LAI antipsychotic duration and those with a shorter LAI antipsychotic duration regarding diastolic dysfunction (p = 0.62).

No significant differences were found between patients with DP, a pre-LAI antipsychotic duration, and a longer LAI antipsychotic duration and those with DP, a pre-LAI antipsychotic duration, and a shorter LAI antipsychotic duration regarding the frequency of HTP (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

Sudden cardiovascular death is up to five times more common in patients with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses than in the general population [20]. More than 60% of patients with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses have had undetected cardiovascular disease before any grave cardiovascular event [21], and this is significantly higher than in the general population. The higher mortality rate [17,18] and its increasing trend [19] have raised concerns regarding a better understanding of the link between the management of schizophrenia and cardiovascular risk factors. There is a clearly higher mortality rate in patients with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses, even without a high coronary artery calcification score [22,23], which may usually have added predictive value. Several studies have presented work in this direction. Our study is one of the first in Romania to establish a relationship between the treatment of schizophrenia and the cardiovascular risk.

Our study demonstrated a strong relationship between several cardiovascular risk factors and the duration of psychosis; the duration of the LAI antipsychotic treatment; the duration between the onset of the disease and the start of LAI antipsychotic treatment; and the use of specific LAI antipsychotic medications. These are discussed in the subsequent paragraphs.

Abdominal obesity was more frequent among patients with a longer duration of psychosis (DP). Hyperglycemia was more frequent among patients with a longer duration before the onset of LAI antipsychotic use. Patients on olanzapine and risperidone had significantly more frequent hyperglycemia compared to those on aripiprazole or paliperidone. Patients on olanzapine and risperidone had more frequent low HDL levels that posed a cardiovascular risk. Social deprivation is linked to the poor control of cholesterol, poor management of blood glucose levels, and poor outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease [24,25]. It is to be noted here that patients having higher BRSE scores with or without treatment resistance would require higher dosages of LAIs [26].

Hypertension was more frequent among patients with a longer duration between the onset of the disease and the start of the LAI antipsychotic treatment. According to old and new literature [27,28], there is a very high rate of unrecognized myocardial infarction in patients with schizophrenia and psychosis. Factors contributing to myocardial infarction in such patients include hyperglycemia, low HDL levels, and hypertension, but are not limited to these alone. A change in pain threshold with decreased pain sensitivity is one mechanism to which the high cardiovascular risk may be attributed in schizophrenia patients [29]. This may explain the late diagnosis of cardiovascular comorbidities in such patients.

Antipsychotic drugs are linked with arrhythmogenic risks in terms of QTc interval prolongation, ventricular arrhythmias, polymorphic ventricular tachycardia torsades de pointes, and sudden cardiac arrest [30]. Antipsychotic drugs are also linked with a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction in patients with schizophrenia [31]. In our study, the occurrence of hypokinetic heart disorders correlated positively with the duration of psychosis, the duration of the LAI treatment, and the duration between the onset of the disease and the start of LAI treatment. In our study, patients on risperidone presented more frequent hypokinetic heart disorders. Echocardiographic findings of valvular changes as well as of diastolic dysfunction were more frequent among patients with a longer duration of psychosis and a longer pre-LAI duration. Another study conducted by Dahelean et al. in 2018 [32] also observed similar findings. Patients on risperidone had significantly more frequent regional myocardial contractility abnormalities and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction than those on olanzapine. Hypokinesia, valvular findings, and diastolic dysfunction can easily lead to ventricular arrhythmias. The pro-arrhythmic effects of psychotropic drugs including antipsychotics and antidepressants can contribute to the increased arrhythmogenicity in patients with schizophrenia [33]. The development of myocardial impairment in schizophrenia patients on long-term treatment may be due to the high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and may be generated by the disease itself [34]. Moreover, a delay in initiating the LAI treatment of schizophrenia patients is a statistically relevant risk factor for LV diastolic dysfunction and overall cardiovascular impairment [34]. Our study also demonstrated that LV diastolic dysfunction was significantly more frequent among patients with a longer pre-LAI antipsychotic duration and with a longer duration following the onset of psychosis.

At present, there are no specific guidelines regarding the early use of LAI antipsychotics [35], and this may contribute to their less frequent or delayed commencement [36]. There is evidence that suggests that olanzapine causes an increased appetite and weight gain [37], especially in patients with a lack of exercise in their routine [38], and a reduction in insulin sensitivity, leading to impaired glucose tolerance [39]. In our study, patients on olanzapine had significantly more frequent hyperglycemia and more frequent low HDL levels; hence, olanzapine should be used with caution in diabetic and obese patients.

The available literature has shown overall good patient outcomes and good patient compliance [40,41,42] and improvements in the quality of life of patients [43] with the use of the aripiprazole LAI. Based on our data, we found that patients on aripiprazole had a lower frequency of hyperglycemia or low HDL levels as well as hypokinesia. However, patients on aripiprazole presented significantly more frequent diastolic dysfunction compared to those on olanzapine or paliperidone.

As with any work, our study is not devoid of limitations. Firstly, it may not reflect the findings in a larger population with psychosis treated with LAI antipsychotics. Secondly, in our study, we could only focus on antipsychotics having LAI formulations to establish their correlations with cardiovascular risk factors. However, the overall approach towards patients with schizophrenia from their diagnosis, the initiation of medication, the use of oral medications, psychological tools, family support systems, and their exercise and dietary patterns have to be addressed in order to have a better understanding of the high cardiovascular risk burden in these patients. Moreover, further studies may be conducted with larger data sets. Not all schizophrenia patients receive monotherapy with LAIs. In addition, the drugs used for LAIs often change over the course of the evolution of a patient’s disease. The use of multiple LAI antipsychotics and their collective impact on patients’ cardiovascular status also have to be considered in future studies. Similar studies can be conducted in the future with a broader, multi-centric population, possibly with the inclusion of more groups, such as non-schizophrenic individuals, schizophrenic individuals not placed on LAIs but given OAs instead, and schizophrenic individuals not given any form of antipsychotic medication, for a comparison of their cardiovascular health outcomes. The literature has also shown subclinical chronic systemic inflammation and immune dysfunction as mechanisms behind the high cardiovascular risk in schizophrenia [44]. This calls for a study of such inflammation-/immunity-related factors and their association with cardiovascular comorbidities in schizophrenia patients.

5. Conclusions

We found strong links between several cardiovascular risk factors and the duration of psychosis; the duration of the LAI antipsychotic treatment; the duration between the onset of the disease and the start of LAI antipsychotic treatment; and the use of specific LAI antipsychotic medications. Abdominal obesity was more frequent among patients with a longer duration of psychosis (DP). Hyperglycemia was more frequent among patients with a longer duration before the onset of LAI antipsychotic use. Patients on olanzapine and risperidone had significantly more frequent hyperglycemia compared to those on aripiprazole or paliperidone. Hypertension was more frequent among patients with a longer duration between the onset of the disease and the start of the LAI antipsychotic treatment. The occurrence of hypokinetic heart disorders correlated positively with the duration of psychosis, the duration of the LAI treatment, and the duration between the onset of the disease and the start of LAI treatment. Patients on risperidone presented more frequent hypokinetic heart disorders. Echography findings of valvular changes as well as of diastolic dysfunction were more frequent among patients with a longer duration of psychosis and longer pre-LAI duration. Our study highlights the need for a better and more personalized cardiovascular care approach in patients with schizophrenia and also the need to explore the choice and timing of the LAI antipsychotic treatment that carries the lowest cardiovascular risk. Further research is needed before reaching any conclusion regarding the recommendation of any particular LAI antipsychotic with the “best” cardiovascular safety profile.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A., L.D. and N.R.K.; methodology, D.N. and A.-M.R.; software, A.-M.R.; validation, M.M.M., M.A. and L.D.; formal analysis, M.M.M. and M.N.N.; investigation, M.A. and M.M.M.; resources, D.A.A.; data curation, D.A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, N.R.K. and D.N.; writing—review and editing, M.M.M. and A.-M.R.; visualization, N.R.K.; supervision, L.D.; project administration, L.D.; funding acquisition, N.R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by the “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Timisoara, Romania.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics committee board of the hospital where the study was performed. The study was carried out according to the Helsinki Declaration. The protocol of the study and the informed consent of the patients were approved by the Scientific Research Ethics Committee of “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timisoara, Romania (reference number 19/2015). Approval date: 22 January 2015.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients/relatives/legal caretakers included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on valid written requests to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McCutcheon, R.A.; Reis Marques, T.; Howes, O.D. Schizophrenia-An Overview. JAMA Psychiatry 2020, 77, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGrath, J.; Saha, S.; Chant, D.; Welham, J. Schizophrenia: A concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol. Rev. 2008, 30, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahn, R.S.; Sommer, I.E.; Murray, R.M.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Weinberger, D.R.; Cannon, T.D.; O’Donovan, M.; Correll, C.U.; Kane, J.M.; van Os, J.; et al. Schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2015, 1, 15067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safiri, S.; Noori, M.; Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Shamekh, A.; Sullman, M.J.M.; Collins, G.S.; Kolahi, A.A. The burden of schizophrenia in the Middle East and North Africa region, 1990–2019. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajraktarov, S.; Blazhevska Stoilkovska, B.; Russo, M.; Repišti, S.; Maric, N.P.; Dzubur Kulenovic, A.; Arënliu, A.; Stevovic, L.I.; Novotni, L.; Ribic, E.; et al. Factor structure of the brief psychiatric rating scale-expanded among outpatients with psychotic disorders in five Southeast European countries: Evidence for five factors. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1207577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagi, K.; Nosaka, T.; Dickinson, D.; Lindenmayer, J.P.; Lee, J.; Friedman, J.; Boyer, L.; Han, M.; Abdul-Rashid, N.A.; Correll, C.U. Association Between Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Cognitive Impairment in People With Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2021, 78, 510–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VandenBerg, A.M. An update on recently approved long-acting injectable second-generation antipsychotics: Knowns and unknowns regarding their use. Ment. Health Clin. 2022, 12, 270–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, C.U.; Kim, E.; Sliwa, J.K.; Hamm, W.; Gopal, S.; Mathews, M.; Venkatasubramanian, R.; Saklad, S.R. Pharmacokinetic Characteristics of Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics for Schizophrenia: An Overview. CNS Drugs 2021, 35, 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samalin, L.; Charpeaud, T.; Blanc, O.; Heres, S.; Llorca, P.M. Clinicians’ attitudes toward the use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2013, 201, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misawa, F.; Kishimoto, T.; Hagi, K.; Kane, J.M.; Correll, C.U. Safety and tolerability of long-acting injectable versus oral antipsychotics: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies comparing the same antipsychotics. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 176, 220–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stip, E.; Lachaine, J. Real-world effectiveness of long-acting antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of 3957 patients with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and other diagnoses in Quebec. Ther. Adv. Psychopharmacol 2018, 8, 287–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyea, S.C.; Nicoll, L.H. Administration of medications via the intramuscular route: An integrative review of the literature and research-based protocol for the procedure. Appl. Nurs. Res. 1995, 8, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, D.M.; Velaga, S.; Werneke, U. Reducing the stigma of long acting injectable antipsychotics—Current concepts and future developments. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2018, 72, S36–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novick, D.; Haro, J.M.; Bertsch, J.; Haddad, P.M. Incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms and tardive dyskinesia in schizophrenia: Thirty-six-month results from the European schizophrenia outpatient health outcomes study. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 30, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, J.M.; Garcia-Ribera, C. Clinical guideline recommendations for antipsychotic long-acting injections. Br. J. Psychiatry Suppl. 2009, 52, S63–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correll, C.U.; Ismail, Z.; McIntyre, R.S.; Rafeyan, R.; Thase, M.E. Patient Functioning, Life Engagement, and Treatment Goals in Schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2022, 83, LU21112AH2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, R.E.; Banner, J.; Jensen, S.E. Cardiovascular disease in patients with severe mental illness. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2021, 18, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Gallagher, K.; Teo, J.T.; Shah, A.M.; Gaughran, F. Interaction Between Race, Ethnicity, Severe Mental Illness, and Cardiovascular Disease. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e025621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, C.U.; Solmi, M.; Croatto, G.; Schneider, L.K.; Rohani-Montez, S.C.; Fairley, L.; Smith, N.; Bitter, I.; Gorwood, P.; Taipale, H.; et al. Mortality in people with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of relative risk and aggravating or attenuating factors. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 248–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risgaard, B. Sudden cardiac death: A nationwide cohort study among the young. Dan. Med. J. 2016, 63, B5321. [Google Scholar]

- Heiberg, I.H.; Jacobsen, B.K.; Balteskard, L.; Bramness, J.G.; Naess, Ø.; Ystrom, E.; Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.; Hultman, C.M.; Nesvåg, R.; Høye, A. Undiagnosed cardiovascular disease prior to cardiovascular death in individuals with severe mental illness. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2019, 139, 558–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghe, A.G.; Jacobsen, C.; Thomsen, R.; Linnet, K.; Lynnerup, N.; Andersen, C.B.; Fuchs, A.; Kofoed, K.F.; Banner, J. Coronary artery CT calcium score assessed by direct calcium quantification using atomic absorption spectroscopy and compared to macroscopic and histological assessments. Int. J. Leg. Med. 2019, 133, 1485–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugathasan, P.; Johansen, M.B.; Jensen, M.B.; Aagaard, J.; Nielsen, R.E.; Jensen, S.E. Coronary Artery Calcification and Mortality Risk in Patients With Severe Mental Illness. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, e008236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veru-Lesmes, F.; Rho, A.; King, S.; Joober, R.; Pruessner, M.; Malla, A.; Iyer, S.N. Social Determinants of Health and Preclinical Glycemic Control in Newly Diagnosed First-Episode Psychosis Patients. Can. J. Psychiatry 2018, 63, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veru-Lesmes, F.; Rho, A.; Joober, R.; Iyer, S.; Malla, A. Socioeconomic deprivation and blood lipids in first-episode psychosis patients with minimal antipsychotic exposure: Implications for cardiovascular risk. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 216, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehelean, L.; Romoşan, A.M.; Andor, M.; Buda, V.O.; Bredicean, A.C.; Manea, M.M.; Papavă, I.; Romoşan, R.Ş. clinical factors influencing antipsychotic choice, dose and augmentation in patients treated with long acting antipsychotics. Farmacia 2020, 68, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, W.E. Occurrence of painless myocardial infarction in psychotic patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 1955, 253, 51–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.; Juel, J.; Alzuhairi, K.S.; Friis, R.; Graff, C.; Kanters, J.K.; Jensen, S.E. Unrecognised myocardial infarction in patients with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2015, 27, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stubbs, B.; Thompson, T.; Acaster, S.; Vancampfort, D.; Gaughran, F.; Correll, C.U. Decreased pain sensitivity among people with schizophrenia: A meta-analysis of experimental pain induction studies. Pain 2015, 156, 2121–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhn, M.; Nikolakopoulou, A.; Schneider-Thoma, J.; Krause, M.; Samara, M.; Peter, N.; Arndt, T.; Bäckers, L.; Rothe, P.; Cipriani, A.; et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 939–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, D.; Saetre, P.; Fors, B.M.; Nilsson, B.M.; Kullberg, J.; Jönsson, E.G.; Ebeling Barbier, C.; Agartz, I. Cardiac left ventricular ejection fraction in men and women with schizophrenia on long-term antipsychotic treatment. Schizophr. Res. 2020, 218, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dehelean, L.; Andor, M.; Romoşan, A.M.; Manea, M.M.; Romoşan, R.Ş.; Papavă, I.; Bredicean, A.C.; Buda, V.O.; Tomescu, M.C. Pharmacological and disorder associated cardiovascular changes in patients with psychosis. A comparison between olanzapine and risperidone. Farmacia 2018, 66, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Fanoe, S.; Kristensen, D.; Fink-Jensen, A.; Jensen, H.K.; Toft, E.; Nielsen, J.; Videbech, P.; Pehrson, S.; Bundgaard, H. Risk of arrhythmia induced by psychotropic medications: A proposal for clinical management. Eur. Heart J. 2014, 35, 1306–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minodora Andor, L.D.; Romosan, A.-M.; Buda, V.; Radu, G.; Caruntu, F.; Bordejevic, A.; Manea, M.M.; Papava, I.; Bredicean, C.A.; Romosan, R.S. A novel approach to cardiovascular disturbances in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders treated with long-acting injectable medication. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2019, 15, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keepers, G.A.; Fochtmann, L.J.; Anzia, J.M.; Benjamin, S.; Lyness, J.M.; Mojtabai, R.; Servis, M.; Walaszek, A.; Buckley, P.; Lenzenweger, M.F.; et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 868–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samalin, L.; Garnier, M.; Auclair, C.; Llorca, P.M. Clinical Decision-Making in the Treatment of Schizophrenia: Focus on Long-Acting Injectable Antipsychotics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, P.H.; Chang, G.R.; Chen, C.P.; Lin, Y.L.; Chao, I.S.; Shen, T.T.; Mao, F.C. Long-term administration of olanzapine induces adiposity and increases hepatic fatty acid desaturation protein in female C57BL/6J mice. Iran. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2018, 21, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, M.; Yu, L.; Pan, F.; Lu, S.; Hu, S.; Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Jin, P.; Qi, H.; Xu, Y. A randomized, 13-week study assessing the efficacy and metabolic effects of paliperidone palmitate injection and olanzapine in first-episode schizophrenia patients. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 81, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicol, G.E.; Yingling, M.D.; Flavin, K.S.; Schweiger, J.A.; Patterson, B.W.; Schechtman, K.B.; Newcomer, J.W. Metabolic Effects of Antipsychotics on Adiposity and Insulin Sensitivity in Youths: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 788–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, J.M.; Sanchez, R.; Baker, R.A.; Eramo, A.; Peters-Strickland, T.; Perry, P.P.; Johnson, B.R.; Tsai, L.F.; Carson, W.H.; McQuade, R.D.; et al. Patient-Centered Outcomes with Aripiprazole Once-Monthly for Maintenance Treatment in Patients with Schizophrenia: Results From Two Multicenter, Randomized, Double-Blind Studies. Clin. Schizophr. Relat. Psychoses 2015, 9, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naber, D.; Baker, R.A.; Eramo, A.; Forray, C.; Hansen, K.; Sapin, C.; Peters-Strickland, T.; Nylander, A.G.; Hertel, P.; Nitschky Schmidt, S.; et al. Long-term effectiveness of aripiprazole once-monthly for schizophrenia is maintained in the QUALIFY extension study. Schizophr. Res. 2018, 192, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potkin, S.G.; Loze, J.Y.; Forray, C.; Baker, R.A.; Sapin, C.; Peters-Strickland, T.; Beillat, M.; Nylander, A.G.; Hertel, P.; Nitschky Schmidt, S.; et al. Multidimensional Assessment of Functional Outcomes in Schizophrenia: Results From QUALIFY, a Head-to-Head Trial of Aripiprazole Once-Monthly and Paliperidone Palmitate. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017, 20, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Calahorro, C.M.; Guerrero Jiménez, M.; Navarro Barrios, J.C. Assessing quality of life following long-acting injection treatment: 4 cases register. Eur. Psychiatry 2016, 33, S537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, D.C.; Vincenzi, B.; Andrea, N.V.; Ulloa, M.; Copeland, P.M. Pathophysiological mechanisms of increased cardiometabolic risk in people with schizophrenia and other severe mental illnesses. Lancet Psychiatry 2015, 2, 452–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).