Abstract

Loop ileostomy is commonly performed by colorectal and general surgeons to protect newly created large bowel anastomoses. The optimal timing for ileostomy closure remains debatable. Defining the timing associated with the best postoperative outcomes can significantly improve the clinical results for patients undergoing ileostomy closure. The LILEO study was a prospective multicenter cohort study conducted in Poland from October 2022 to December 2023. Full data analysis involved 159 patients from 19 surgical centers. Patients were categorized based on the timing of ileostomy reversal: early (<4 months), standard (4–6 months), and delayed (>6 months). Data on demographics, clinical characteristics, and perioperative outcomes were analyzed for each group separately and compared. No significant differences were observed in length of hospital stay (p = 0.22), overall postoperative complications (p = 0.43), or 30-day reoperation rates (p = 0.28) across the three groups. Additional analysis of Clavien–Dindo complication grades was performed and did not show significant differences in complication severity (p = 0.95), indicating that the timing of ileostomy closure does not significantly impact perioperative complications or hospital stay. Decisions on ileostomy reversal timing should be personalized and should consider individual clinical factors, including the type of adjuvant oncological treatment and the preventive measures performed for common postoperative complications.

1. Introduction

Loop ileostomy is commonly performed by colorectal and general surgeons to protect newly created large bowel anastomoses [1]. Due to the diversion of fecal contents from the large bowel in the event of anastomotic leakage, patients have a lesser risk of major postoperative complications, like fecal peritonitis and potential septic shock. Such complications can have detrimental effects on patients’ short- and long-term operative outcomes [2]. The creation of an independent diverting ileostomy can also negatively affect patient health by leading to electrolyte disturbances, and, in the worst case, to renal insufficiency. Readmissions with acute renal insufficiency increase tenfold in patients with an ileostomy that has not been reversed [3]. Furthermore, ileostomy closure is a separate surgical procedure that can also result in postoperative complications in up to 37% of cases [4]. The standard time of ileostomy closure and restoration of the gastrointestinal tract continuity is around 3 to 6 months [5]. Some surgeons tend to close the ileostomy very early, for example in less than 2 weeks, minimizing the possibility of delayed detrimental effects of the stoma on patients’ physical and mental health. This may not apply to patients undergoing adjuvant oncological therapy [6]. Additionally, as many as 73% of patients strongly desire to have the ileostomy closure as soon as possible [7]. A study from Japan assessing very early ileostomy closure showed serious postoperative adverse events and was even terminated due to a high number of complications [8]. Other surgeons prefer to close ileostomies later, only after the oncological treatment is finished [9]. There is also concern about low anterior resection syndrome (LARS), which can be associated with the presence of a defunctioning loop ileostomy [10]. Systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that the prolonged time to ileostomy closure may negatively influence bowel function. Vogel et al. concluded that patients with prolonged preservation of defunctioning loop ileostomies have a significantly higher risk of major LARS [11]. Therefore, it is important to establish the optimal time for ileostomy closure in order to minimize its adverse effects. To date, no prospective assessment of Polish patients undergoing ileostomy closure has been performed; only small, preliminary studies have been conducted [12]. The objective of this study was to perform a comparison of early postoperative outcomes in early, standard, and delayed ileostomy reversal patients.

2. Materials and Methods

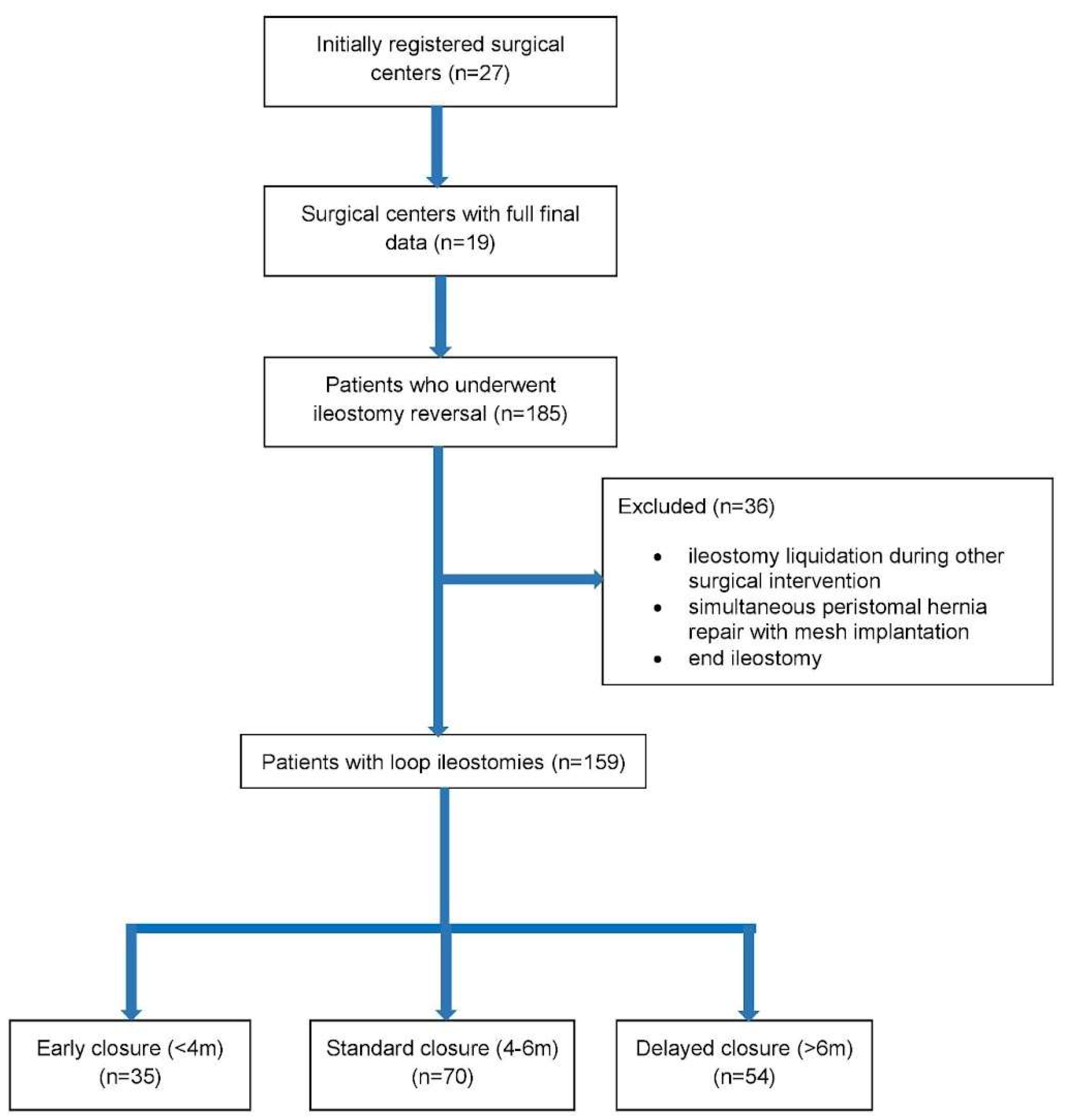

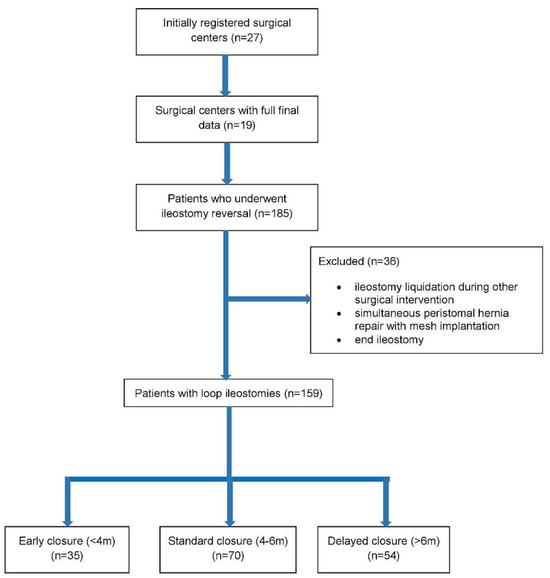

The LIquidation of iLEOstomy (LILEO) study was a prospective multicenter cohort study that lasted from October 2022 until the end of December 2023 and focused on the clinical outcomes of patients undergoing ileostomy reversal (liquidation of the ileostomy procedure). A unified study protocol was sent to all participating surgical centers before the start of the study, providing precise instructions on inclusion and exclusion criteria, as well as on how the database should be filled in prospectively. Furthermore, the patient consent form and information about the study, provided in the form of a leaflet, were sent to each surgical center to ensure that every patient received the same information. The specially designed database included anonymous parameters divided into several categories: demographic data, ileostomy creation data (e.g., created by a specialist or resident, indications), perioperative care parameters, surgical procedure and technique data, complications, and postoperative outcomes (e.g., reoperations, mortality, and readmissions within 30 days of discharge). Out of 27 initially registered surgical centers in Poland, 19 centers provided data by the end of the study using a password-secured database.

The inclusion criteria consisted of the following requirements: patients undergoing ileostomy reversal who were older than 18 years of age and who provided informed consent to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria were the following: ileostomy reversal that occurred during a different procedure, for example during a hemihepatectomy, and concomitant parastomal hernia repair with mesh implantation. The data were obtained during the hospital stay and outpatient visits within 30 days after discharge. Ileostomy closure was possible after the assurance of healed rectal anastomosis. The healing was confirmed by endoscopy conducted prior to ileostomy closure.

Information acquired from the surgical centers included data from 185 patients after ileostomy reversal and various demographic, clinical, and perioperative parameters. For this particular study, 159 patients who underwent loop ileostomy reversal were selected for further analysis (106 males, 53 females). Patients were divided into 3 groups according to the time of ileostomy reversal: (1) early (<4 months); (2) standard (4–6 months); and (3) delayed (>6 months). A flowchart showing the formation of the three study groups is presented below in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study.

The primary goals of the study were the length of hospital stay (LOS), postoperative complications, and 30-day reoperation rate. The secondary goal was the assessment of the complication rate according to the Clavien–Dindo classification. Statistical analysis was performed using Statsoft STATISTICA v.13 (StatSoft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Numerical variables are shown as mean and/or standard deviation (SD) with the use of median and interquartile range (IQR) when appropriate, and categorical variables are displayed using percentages. The Pearson chi-square test of independence was applied to examine the relationship between each variable and outcome. For normally distributed data, the Shapiro–Wilk test was used. In non-normally distributed quantitative variable groups, a comparison was made using the Kruskal–Wallis test. A p-value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The study (KBKA/55/O/2022) was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the Andrzej Frycz-Modrzewski University in Cracow, Poland.

3. Results

The earliest ileostomy reversal took place 2 weeks after the initial ileostomy, and the latest occurred 28 months afterward. The median age at the time of ileostomy closure was 65 years in group 1, 64 years in group 2, and 66 years in group 3 (p = 0.635). The median body mass index (BMI) of the studied groups was 25.5, 26.2, and 26.4 kg/m2, respectively (p = 0.313). The number of female patients was higher in the early ileostomy reversal group, but, in reference to age, BMI, ASA scale, or comorbidities, such as ischemic heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes, no statistically significant differences between the groups were observed. The majority (>90%) of ileostomies were created by specialist surgeons in all three groups. Demographics and analysis of the study groups are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the patients.

Operations were performed by specialist surgeons in 65.7% of surgeries in the early group, in 55.7% of surgeries in the standard group, and in 70.4% of surgeries in the delayed group; no statistically significant differences were seen (p = 0.45). Two cases of operator change from resident to specialist occurred; one in the standard reversal group and one in the delayed reversal group. The length of hospital stay (LOS) did not differ between the early, standard, and delayed ileostomy reversal groups. Median LOS was 5, 5.5, and 6 days in the three groups, respectively (p = 0.22). Postoperative complications were observed in all three ileostomy reversal groups: 34.3% in the early group, 24.3% in the standard group, and 33.3% in the delayed group (p = 0.43). No difference in the 30-day reoperation rate was observed between the early reversal (8.6%), standard reversal (2.9%), and delayed reversal groups (9.3%), (p = 0.28). The results according to the primary goals of the study are presented below in Table 2.

Table 2.

Outcomes of ileostomy reversal in the three groups according to the primary goals of the study.

The wound infection rate in the early reversal group was 25.7%, it was 12.9% in the standard reversal group, and in the delayed group, it was the lowest at 7.4%. Despite the noticeable difference between the early reversal group (25.7%) and the delayed reversal group (7.4%), we observed no statistical significance (p = 0.05).

In a separate analysis of complications in the Clavien–Dindo scale with special consideration according to complication severity, we also did not notice a difference between light (grade 1 and 2) and serious (grade 3–5) complications (p = 0.95). The results according to the secondary goals of the study are presented below in Table 3.

Table 3.

Outcomes of ileostomy reversal in the three groups according to the secondary goals of the study.

4. Discussion

One of the novelties of our approach was to divide the study population into three groups of loop ileostomy reversal times: early, standard, and delayed. Most of the preceding studies were designed to compare very early versus delayed ileostomy reversal groups, or simply early versus delayed ileostomy reversal groups. In our multicenter prospective study, we also introduced a standard group, which, we believe, provides more clarity and answers the question regarding loop ileostomy closure timing that has been lingering for many years, with the first scientific inquiry occurring about 20 years ago [13].

Single-center studies performed previously were commonly retrospective in their character, and the results suggested better outcomes of early ileostomy closure [14,15]. Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that those studies analyzed groups of patients operated on over a long time period, ranging from 5 to 12 years. During this time, perioperative care evolved significantly, due to the introduction of fast-track pathways, such as the ERAS protocol in colorectal surgery, which was introduced in 2005 [16,17]. Other retrospective studies by Zhou et al. and Sauri et al. failed to show any differences between early and delayed ileostomy reversal groups in terms of postoperative complications and LOS [18,19].

On the other hand, a prospective study with randomization from 3 Swiss hospitals was ended due to significantly increased postoperative complications in the early reversal group [20]. Similarly, a randomized study by Vogel et al., in which ileostomy reversal took place 7 to 12 days after proctocolectomy with ileal pouch construction, was also ended prematurely due to the unacceptably high number of postoperative complications in comparison to the delayed group [21]. However, the earlier closure of ileostomy in inflammatory bowel disease patients has been advocated by Morada et al. due to the risk of ileostomy site malignancies, which was found to be time-dependent; the longer the ileostomy was present, the higher was the risk of ileostomy site malignancy. Similarly, in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis, researchers believe that ileostomy reversal should be performed earlier [22,23].

Meta-analysis performed by Li Wang et al. found that early ileostomy closure can result in a greater number of postoperative complications with the predominance of wound infections. Conversely, delayed closure was associated with more preoperative stoma-related complications, such as skin irritation and stoma bag leakage. No difference was observed in the comparison of severe complications between groups [24]. Interestingly, the postoperative quality of life of ileostomy patients was similar when compared in the early and standard closure groups by the EORTC QLQ-C30 and LARS questionnaires [25].

One of the most common postoperative complications encountered by patients undergoing ileostomy closure is postoperative ileus (POI), accounting for as many as 20% of complications. The longer the ileostomy was present, the higher was the POI risk [26]. Also, the POI risk was higher in patients who had POI after initial colorectal surgery [27]. Loss of the microbiota in the malfunctioning bowel can be responsible for increased risk of perioperative complications. Probiotics were used preoperatively to minimize this, but eventually there was no difference in the final microbiota diversity observed in patients with and without complications [28]. Among the preoperative maneuvers that can potentially decrease the frequency of POI is bowel stimulation via the efferent limb of ileostomy [29]. Lloyd et al. performed a meta-analysis of available studies where the efferent limb of ileostomy was physiologically stimulated by administration of saline solution with a thickening agent that resulted in reduced postoperative complications and shortened LOS. This can be an additional factor favoring delayed ileostomy closure [30]. Also, postoperative gum chewing is a simple and effective way to prevent POI. The return of peristalsis was significantly faster when gum was chewed for 30 min approximately 6 h after surgery and repeated every 8 h, resulting in a shorter LOS [31].

Infections are also among the most common complications of ileostomy reversal. Surgical site infections (SSIs) occurred more frequently in patients undergoing early ileostomy reversal [19]. Many authors suggested that wound closure by purse-string sutures or by the use of incisional negative pressure wound therapy (iNPWT) may be a very effective way to prevent SSIs [32,33,34]. Moreover, Clostridium difficile infection is a postoperative complication affecting up to 4% of patients undergoing ileostomy reversal and, in a retrospective study by Richards et al., was shown to occur more often in the delayed ileostomy reversal groups [35,36]. The aforementioned arguments should be taken into account during the general assessment of prospective ileostomy reversal patients. Instead of solely using the time criterion (early, standard, or delayed), an individualized approach should be the basis for clinical decision making.

Lastly, many patients with defunctioning ileostomies undergo continuous systematic oncological therapy. Cheng et al. showed that ileostomy patients can undergo reversal surgery in adequate time following chemotherapy, without a consequent increase in postoperative complications. Nevertheless, patients receiving specific agents, such as bevacizumab, can develop major drug-specific complications, and special caution should be used when planning ileostomy reversals in such patients [37].

The limitations of our study include various surgical techniques and perioperative care practices and are due to data coming from different surgical departments across Poland. In this study, we did not analyze the methods of ileostomy closure and outpatient preoperative preparation for the procedure, which also could differ between surgical centers involved in this study. However, given the large number of patients analyzed prospectively, we are able to draw conclusions regarding the impact of ileostomy closure time on subsequent outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Our analysis showed that the time interval from index surgery until ileostomy reversal is not predictive for perioperative complications, for 30-day reoperation rate, or for LOS. When deciding on the optimal time for ileostomy reversal, many other clinical factors should be taken into consideration, including oncological prognosis and the current type of adjuvant therapy. Common postoperative complications, like POIs and SSIs, should be prevented by readily available evidence-based techniques, such as preoperative efferent-limb stimulation, postoperative gum chewing, purse-string suturing, or iNPWT.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K., T.W. and W.M.W.; methodology, M.K. and M.P.-A.; software, M.P.-A. and V.C.; validation, M.K., T.W. and W.M.W.; formal analysis, M.P.-A. and V.C.; investigation, M.K., N.D.-G., Ł.N., W.S., M.W. (Mateusz Wierdak), J.W., K.S., M.J., M.D., J.P., M.M., W.F., M.J., K.T., M.W. (Michał Wysocki), M.L., M.Z. and T.S.; resources, M.K., N.D.-G., Ł.N., W.S., M.W. (Mateusz Wierdak), J.W., K.S., M.J., M.D., J.P., M.M., W.F., M.J., K.T., M.W. (Michał Wysocki), M.L., M.Z. and T.S.; data curation, M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, M.K., M.P.-A. and W.M.W.; writing—review and editing, M.K., N.D.-G. and W.M.W.; visualization, M.K. and W.M.W.; supervision, W.M.W.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. and W.M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski Krakow University—grants WDPR/2024/03/00002 and WSUB/2024/03/00002.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski Krakow University (KBKA/55/o/2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish the scientific results of the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data without personal patient information can be available upon request via email to the main author.

Acknowledgments

Special gratitude to the collaborative authors from LILEO study group: Michał Stańczak, Maria Wikar, Paula Franczak, Ewa Grudzińska, Sławomir Mrowiec, Jakub Wantulok, Wiktor Krawczyk, Bartosz Grzechulski, Krzysztof Ratnicki, Ignacy Oleszczuk, Bartosz Molasy, Andrzej Komorowski.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pisarska, M.; Gajewska, N.; Małczak, P.; Wysocki, M.; Witowski, J.; Torbicz, G.; Major, P.; Mizera, M.; Dembiński, M.; Migaczewski, M.; et al. Defunctioning ileostomy reduces leakage rate in rectal cancer surgery-systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 20816–20825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chiarello, M.M.; Fransvea, P.; Cariati, M.; Adams, N.J.; Bianchi, V.; Brisinda, G. Anastomotic leakage in colorectal cancer surgery. Surg. Oncol. 2022, 40, 101708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fielding, A.; Woods, R.; Moosvi, S.R.; Wharton, R.Q.; Speakman, C.T.M.; Kapur, S.; Shaikh, I.; Hernon, J.M.; Lines, S.W.; Stearns, A.T. Renal impairment after ileostomy formation: A frequent event with long-term consequences. Color. Dis. 2020, 22, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Climent, M.; Frago, R.; Cornella, N.; Serrano, M.; Kreisler, E.; Biondo, S. Prognostic factors for complications after loop ileostomy reversal. Tech. Coloproctol. 2022, 26, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, N.J.; Temperley, H.C.; Nugent, T.S.; Low, E.Z.; Kavanagh, D.O.; Larkin, J.O.; Mehigan, B.J.; McCormick, P.H.; Kelly, M.E. Early vs. standard reversal ileostomy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech. Coloproctol. 2022, 26, 851–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Z.Q.; Levitt, M.; Platell, C. The feasibility and safety of early ileostomy reversal: A systematic review and meta-analysis. ANZ J. Surg. 2020, 90, 1580–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caminsky, N.G.; Moon, J.; Morin, N.; Alavi, K.; Auer, R.C.; Bordeianou, L.G.; Chadi, S.A.; Drolet, S.; Ghuman, A.; Liberman, A.S.; et al. Patient and surgeon preferences for early ileostomy closure following restorative proctectomy for rectal cancer: Why aren’t we doing it? Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fukudome, I.; Maeda, H.; Okamoto, K.; Yamaguchi, S.; Fujisawa, K.; Shiga, M.; Dabanaka, K.; Kobayashi, M.; Namikawa, T.; Hanazaki, K. Early stoma closure after low anterior resection is not recommended due to postoperative complications and asymptomatic anastomotic leakage. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ahmadi-Amoli, H.; Rahimi, M.; Abedi-Kichi, R.; Ebrahimian, N.; Hosseiniasl, S.M.; Hajebi, R.; Rahimpour, E. Early closure compared to late closure of temporary ileostomy in rectal cancer: A randomized controlled trial study. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2023, 408, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, F.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, J.; Sun, Z. A novel nomogram to predict low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) after ileostomy reversal for rectal cancer patients. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 2023, 49, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, I.; Reeves, N.; Tanis, P.J.; Bemelman, W.A.; Torkington, J.; Hompes, R.; Cornish, J.A. Impact of a defunctioning ileostomy and time to stoma closure on bowel function after low anterior resection for rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech. Coloproctol. 2021, 25, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kisielewski, M.; Wysocki, M.; Stefura, T.; Wojewoda, T.; Safiejko, K.; Wierdak, M.; Sachanbiński, T.; Jankowski, M.; Tkaczyński, K.; Richter, K.; et al. Preliminary results of Polish national multicenter LILEO study on ileostomy reversal. Pol. J. Surg. 2024, 96, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krand, O.; Yalti, T.; Berber, I.; Tellioglu, G. Early vs. delayed closure of temporary covering ileostomy: A prospective study. Hepato-Gastroenterol. 2008, 55, 142–145. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, S.; Scarpinata, R. Early and Late Closure of Loop Ileostomies: A Retrospective Comparative Outcomes Analysis. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2018, 64, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, T.W.; Dudi-Venkata, N.N.; Beh, Y.Z.; Bedrikovetski, S.; Kroon, H.M.; Thomas, M.L.; Sammour, T. Impact of timing of reversal of loop ileostomy on patient outcomes: A retrospective cohort study. Tech. Coloproctol. 2021, 25, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eskicioglu, C.; Forbes, S.S.; Aarts, M.-A.; Okrainec, A.; McLeod, R.S. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs for patients having colorectal surgery: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2009, 13, 2321–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, K.A.; Fleming, R.Y.D.; Fox, A.W.; Grimes, A.E.; Mohiuddin, S.S.; Robertson, H.T.; Moxham, J.; Wolf, J.S., Jr. The Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) Elements that Most Greatly Impact Length of Stay and Readmission. Am. Surg. 2021, 87, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.W.; Wang, Z.H.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Xiang, J.-B.; Gu, X.-D. Advantages of Early Preventive Ileostomy Closure after Total Mesorectal Excision Surgery for Rectal Cancer: An Institutional Retrospective Study of 123 Consecutive Patients. Dig. Surg. 2017, 34, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauri, F.; Sakr, A.; Kim, H.S.; Alessa, M.; Torky, R.; Zakarneh, E.; Yang, S.Y.; Kim, N.K. Does the timing of protective ileostomy closure post-low anterior resection have an impact on the outcome? A retrospective study. Asian J. Surg. 2021, 44, 374–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsner, A.T.; Brosi, P.; Walensi, M.; Uhlmann, M.; Egger, B.; Glaser, C.; Maurer, C.A. Closure of Temporary Ileostomy 2 Versus 12 Weeks after Rectal Resection for Cancer: A Word of Caution from a Prospective, Randomized Controlled Multicenter Trial. Dis. Colon. Rectum 2021, 64, 1398–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.D.; Fleshner, P.R.; Holubar, S.D.; Poylin, V.Y.; Regenbogen, S.E.; Chapman, B.C.; Messaris, E.; Mutch, M.G.; Hyman, N.H. High Complication Rate after Early Ileostomy Closure: Early Termination of the Short Versus Long Interval to Loop Ileostomy Reversal after Pouch Surgery Randomized Trial. Dis. Colon. Rectum 2023, 66, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morada, A.O.; Senapathi, S.H.; Bashiri, A.; Chai, S.; Cagir, B. A systematic review of primary ileostomy site malignancies. Surg. Endosc. 2022, 36, 1750–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanada, M.; Chika, N.; Kamae, N.; Muta, Y.; Chikatani, K.; Ito, T.; Mori, Y.; Suzuki, O.; Hatano, S.; Iwama, T.; et al. A Case of Carcinoma of the Ileostomy Site Associated with Familial Adenomatous Polyposis-Report of a Case. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 2021, 48, 1990–1992. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Chen, X.; Liao, C.; Wu, Q.; Luo, H.; Yi, F.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, W. Early versus late closure of temporary ileostomy after rectal cancer surgery: A meta-analysis. Surg. Today 2021, 51, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulskas, A.; Petrauskas, V.; Kuliavas, J.; Bickaite, K.; Kairys, M.; Pauza, K.; Kilius, A.; Sangaila, E.; Bausys, R.; Stratilatovas, E. Quality of Life and Bowel Function Following Early Closure of a Temporary Ileostomy in Patients with Rectal Cancer: A Report from a Single-Center Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Guidolin, K.; Jung, F.; Spence, R.; Quereshy, F.; Chadi, S.A. Extended duration of faecal diversion is associated with increased ileus upon loop ileostomy reversal. Color. Dis. 2021, 23, 2146–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Padilla, Á.; Morales-Martín, G.; Perez-Quintero, R.; Gomez-Salgado, J.; Balongo-Garcia, R.; Ruiz-Frutos, C. Postoperative Ileus after Stimulation with Probiotics before Ileostomy Closure. Nutrients 2021, 13, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beamish, E.L.; Johnson, J.; Shih, B.; Killick, R.; Dondelinger, F.; McGoran, C.; Brewster-Craig, C.; Davies, A.; Bhowmick, A.; Rigby, R.J. Delay in loop ileostomy reversal surgery does not impact upon post-operative clinical outcomes. Complications are associated with an increased loss of microflora in the defunctioned intestine. Gut Microbes 2023, 15, 2199659. [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkle, R.; Demian, M.; Sabboobeh, S.; Moon, J.; Hulme-Moir, M.; Liberman, A.S.; Feinberg, S.; Hayden, D.M.; Chadi, S.A.; Demyttenaere, S.; et al. Bowel stimulation before loop ileostomy closure to reduce postoperative ileus: A multicenter, single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Surg. Endosc. 2023, 37, 3934–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lloyd, A.J.; Hardy, N.P.; Jordan, P.; Ryan, E.J.; Whelan, M.; Clancy, C.; O’Riordan, J.; Kavanagh, D.O.; Neary, P.; Sahebally, S.M. Efferent limb stimulation prior to loop ileostomy closure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tech. Coloproctol. 2023, 28, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatti, S.; Malik, Y.J.; Changazi, S.H.; Rahman, U.A.; Malik, A.A.; Butt, U.I.; Umar, M.; Farooka, M.W.; Ayyaz, M. Role of Chewing Gum in Reducing Postoperative Ileus after Reversal of Ileostomy: A Randomized Controlled Trial. World J. Surg. 2021, 45, 1066–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajibandeh, S.; Hajibandeh, S.; Kennedy-Dalby, A.; Rehman, S.; Zadeh, R.A. Purse-string skin closure versus linear skin closure techniques in stoma closure: A comprehensive meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of randomised trials. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2018, 33, 1319–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajibandeh, S.; Hajibandeh, S.; Maw, A. Purse-string skin closure versus linear skin closure in people undergoing stoma reversal. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 3, CD014763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wierdak, M.; Pisarska-Adamczyk, M.; Wysocki, M.; Major, P.; Kołodziejska, K.; Nowakowski, M.; Vongsurbchart, T.; Pędziwaitr, M. Prophylactic negative-pressure wound therapy after ileostomy reversal for the prevention of wound healing complications in colorectal cancer patients: A randomized controlled trial. Tech. Coloproctol. 2021, 25, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Harries, R.L.; Ansell, J.; Codd, R.J.; Williams, G.L. A systematic review of Clostridium difficile infection following reversal of ileostomy and colostomy. Color. Dis. 2021, 23, 1837–1848. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, S.J.G.; Udayasiri, D.K.; Jones, I.T.; Hastie, I.A.; Chandra, R.; McCormick, J.; Chittleborough, T.J.; Read, D.J.; Hayes, I.P. Delayed ileostomy closure increases the odds of Clostridium difficile infection. Color. Dis. 2021, 23, 3213–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-H.; Shao, Y.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chiang, T.-W.; Chen, M.-C.; Chiu, T.-Y.; Huang, Y.-L.; Chen, C.-C.; Chen, C.-P.; Chiang, F.-F. Impact of chemiotherapy on surgical outcomes in ileostomy reversal: A propensity score matching study from a single center. Tech. Coloproctol. 2023, 12, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).