Do Host Plant and Associated Ant Species Affect Microbial Communities in Myrmecophytes?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Microbial Isolation and Identification

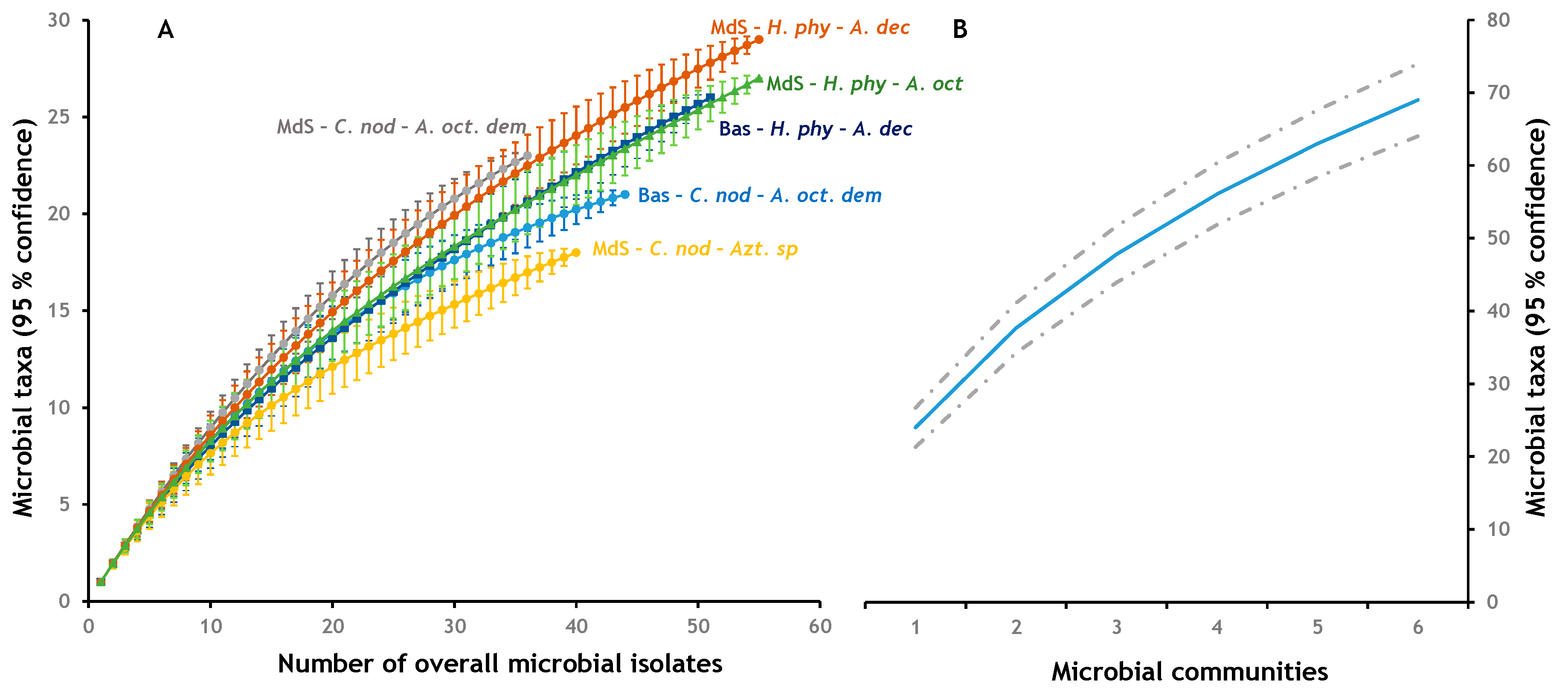

2.3. Alpha Diversity

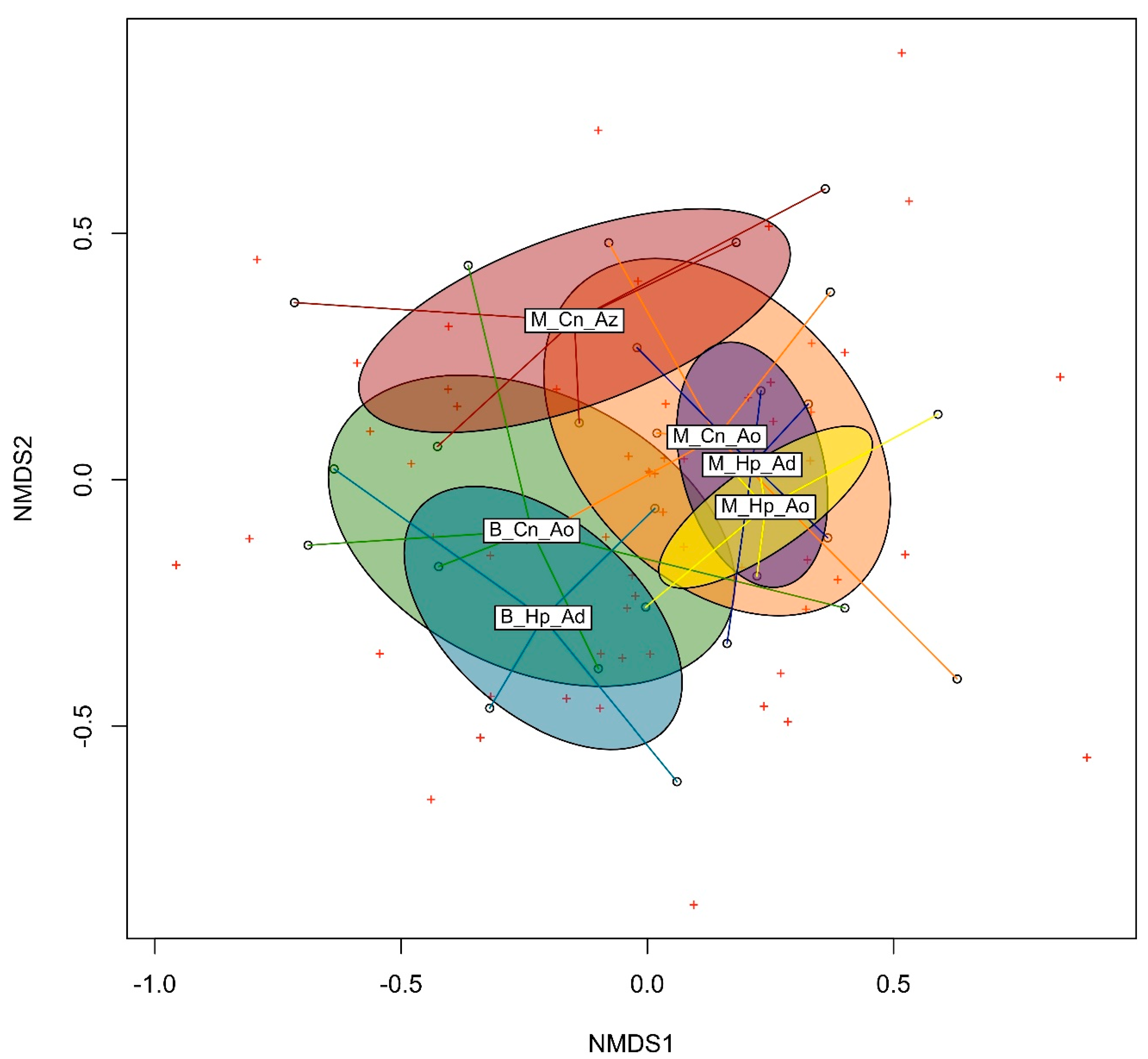

2.4. Beta Diversity

3. Results

3.1. Microbial Isolation

3.2. Alpha Diversity

3.3. Beta Diversity

4. Discussion

4.1. Microbial Diversity and Composition

4.2. Variations in Microbial Communities

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hung, K.-L.J.; Kingston, J.M.; Albrecht, M.; Holway, D.A.; Kohn, J.R. The worldwide importance of honey bees as pollinators in natural habitats. Proc. R. Soc. B 2018, 285, 20172140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, D.; van Veen, F.J.F. Ecosystem engineering and predation: The multi-trophic impact of two ant species. J. Anim. Ecol. 2011, 80, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, E.O. The Insect Societies; Belknap: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1971; p. 548. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, E. The effects of complex social life on evolution and biodiversity. Oikos 1992, 63, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremer, S.; Armitage, S.A.O.; Schmid-Hempel, P. Social Immunity. Curr. Biol. 2007, 17, 693–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meunier, J. Social immunity and the evolution of group living in insects. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2015, 370, 20140102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Hempel, P. Parasites in Social Insects; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, H.M.; Ashton, L.A.; Walker, A.E.; Hasan, F.; Evans, T.A.; Eggleton, P.; Parr, C.L. Ants are the major agents of resource removal from tropical rainforests. J. Anim. Ecol. 2018, 87, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Hempel, P. Parasites and their social hosts. Trends Parasitol. 2017, 33, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aylward, F.O.; Burnum, K.E.; Scott, J.J.; Suen, G.; Tringe, S.G.; Adams, S.M.; Barry, K.W.; Nicora, C.D.; Piehowski, P.D.; Purvine, S.O.; et al. Metagenomic and metaproteomic insights into bacterial communities in leaf-cutter ant fungus gardens. ISME J. 2012, 6, 1688–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, C.R.; Scott, J.A.; Summerbell, R.C.; Malloch, D. Fungus-growing ants use antibiotic-producing bacteria to control garden parasites. Nature 1999, 398, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, C.R.; Bot, A.N.M.; Boomsma, J.J. Experimental evidence of a tripartite mutualism: Bacteria protect ant fungus gardens from specialized parasites. Oikos 2003, 101, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, K.; Ishak, H.D.; Linksvayer, T.A.; Mueller, U.G. Bacterial community composition and diversity in an ancestral ant fungus symbiosis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2015, 91, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, A.E.F.; Currie, C.R. Symbiotic complexity: Discovery of a fifth symbiont in the attine ant-microbe symbiosis. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 501–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdiabadi, N.J.; Hughes, B.; Mueller, U.G. Cooperation, conflict, and coevolution in the attine ant-fungus symbiosis. Behav. Ecol. 2006, 17, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, S.B.; Yek, S.H.; Nash, D.R.; Boomsma, J.J. Interaction specificity between leaf-cutting ants and vertically transmitted Pseudonocardia bacteria. BMC Evol. Biol. 2015, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T.R.; Brady, S.G. Major evolutionary transitions in ant agriculture. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 5435–5440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.J.; Budsberg, K.J.; Suen, G.; Wixon, D.L.; Balser, T.C.; Currie, C.R. Microbial community structure of leaf-cutter ant fungus gardens and refuse dumps. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boots, B.; Clipson, N. Linking ecosystem modification by the yellow meadow ant (Lasius flavus) to microbial assemblages in different soil environments. Eur. J. Soil. Biol. 2013, 55, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauber, J.; Schroeter, D.; Wolters, V. Species specific effects of ants on microbial activity and N-availability in the soil of an old-field. Eur. J. Soil. Biol. 2001, 37, 259–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Eldridge, D.J.; Hamonts, K.; Singh, B.K. Ant colonies promote the diversity of soil microbial communities. ISME J. 2019, 13, 1114–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duff, L.B.; Urichuk, T.M.; Hodgins, L.N.; Young, J.R.; Untereine, W.A. Diversity of fungi from the mound nests of Formica ulkei and adjacent non-nest soils. Can. J. Microbiol. 2016, 62, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Defossez, E.; Selosse, M.-A.; Dubois, M.-P.; Mondolot, L.; Faccio, A.; Djieto-Lordon, C.; McKey, D.; Blatrix, R. Ant-plants and fungi: A new three-way symbiosis. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, V.E.; Nepel, M.; Blatrix, R.; Oberhauser, F.B.; Fiedler, K.; Schönenberger, J.; Voglmayr, H. Transmission of fungal partners to incipient Cecropia-tree ant colonies. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, V.E.; Voglmayr, H. Mycelial carton galleries of Azteca brevis (Formicidae) as a multi-species network. Proc. R. Soc. B 2009, 276, 3265–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz-González, M.X.; Malé, P.-J.G.; Leroy, C.; Dejean, A.; Gryta, H.; Jargeat, P.; Quilichini, A.; Orivel, J. Specific, non-nutritional association between an ascomycete fungus and Allomerus plant-ants. Biol. Lett. 2011, 7, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janzen, D.H. Coevolution of mutualism between ants and acacias in Central America. Evolution 1966, 20, 249–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, P.J.; Durou, S.; Corbara, B.; Quilichini, A.; Cerdan, P.; Belin-Depoux, M.; Delabie, J.H.C.; Dejean, A. Myrmecophytes of the understory of French Guianian rainforests: Their distribution and their associated ants. Sociobiology 2003, 41, 605–614. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, V.E.; Frederickson, M.E.; McKey, D.; Blatrix, R. Current issues in the evolutionary ecology of ant-plant symbioses. New Phytol. 2014, 202, 749–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramette, A.; Tiedje, J.M. Multiscale responses of microbial life to spatial distance and environmental heterogeneity in a patchy ecosystem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 2761–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nemergut, D.R.; Schmidt, S.K.; Fukami, T.; O’Neill, S.P.; Bilinski, T.M.; Stanish, L.F.; Knelman, J.E.; Darcy, J.L.; Lynch, R.C.; Wickey, P.; et al. Patterns and processes of microbial community assembly. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013, 77, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejean, A.; Azémar, F.; Petitclerc, F.; Delabie, J.H.C.; Corbara, B.; Leroy, C.; Céréghino, R.; Compin, A. Highly modular pattern in ant-plant interactions involving specialized and non-specialized myrmecophytes. Sci. Nat. 2018, 105, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, F. The myrmicine ant genus Allomerus Mayr (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Caldasia 2007, 29, 159–175. [Google Scholar]

- Dejean, A.; Solano, P.J.; Ayroles, J.; Corbara, B.; Orivel, J. Arboreal ants build traps to capture prey. Nature 2005, 434, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauth, J.; Ruiz-González, M.X.; Orivel, J. New findings in insect fungiculture. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2011, 4, 728–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, C.; Séjalon-Delmas, N.; Jauneau, A.; Ruiz-González, M.X.; Gryta, H.; Jargeat, P.; Corbara, B.; Dejean, A.; Orivel, J. Trophic mediation by a fungus in an ant–plant mutualism. J. Ecol. 2011, 99, 583–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seipke, R.F.; Barke, J.; Ruiz-González, M.X.; Orivel, J.; Yu, D.W.; Hutchings, M.I. Fungus-growing Allomerus ants are associated with antibiotic-producing actinobacteria. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2012, 101, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orivel, J.; Malé, P.-J.; Lauth, J.; Roux, O.; Petitclerc, F.; Dejean, A.; Leroy, C. Trade-offs in an ant-plant-fungus mutualism. Proc. R. Soc. B 2017, 284, 20161679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, S.A.; Cremers, G.; Gracie, C.A.; de Granville, J.-J.; Heald, S.V.; Hoff, M.; Mitchell, J.D. Guide to the Vascular Plants of Central French Guiana, Part 2, Dicotyledons; The New York Botanical Garden: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, C.; Jauneau, A.; Quilichini, A.; Dejean, A.; Orivel, J. Comparison between the anatomical and morphological structure of leaf blades and foliar domatia in the ant-plant Hirtella physophora (Chrysobalanaceae). Ann. Bot. 2008, 101, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, P.S.; Metzger, D.A.; Higuchi, R. Chelex-100 as a medium for simple extraction of DNA for PCR-based typing from forensic material. Biotechniques 1991, 10, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisburg, W.G.; Barns, S.M.; Pelletier, D.A.; Lane, D.J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 1991, 173, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Innis, N., Gelfand, D., Sninsky, J., White, T., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST). Available online: https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol. Electron. 2001, 4, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Arbizu, P. PairwiseAdonis: Pairwise Multilevel Comparison Using Adonis. R Package Version 0.3. 2019. Available online: https://github.com/pmartinezarbizu/pairwiseAdonis (accessed on 17 June 2019).

- Lucas, J.M.; Madden, A.A.; Penick, C.A.; Epps, M.J.; Marting, P.R.; Stevens, J.L.; Fergus, D.J.; Dunn, R.R.; Meineke, E.K. Azteca ants maintain unique microbiomes across functionally distinct nest chambers. Proc. R. Soc. B 2019, 286, 20191026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mueller, U.G.; Gerardo, N.M.; Aanen, D.K.; Six, D.L.; Schultz, T.R. The evolution of agriculture in insects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2005, 36, 563–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eilmus, S.; Heil, M. Bacterial associates of arboreal ants and their putative functions in an obligate ant-plant mutualism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 4324–4332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto-Tomas, A.A.; Anderson, M.A.; Suen, G.; Stevenson, D.M.; Chu, F.S.T.; Cleland, W.W.; Weimer, P.J.; Currie, C.R. Symbiotic nitrogen fixation in the fungus gardens of leaf-cutter ants. Science 2009, 326, 1120–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucchi, T.D.; Guidolin, A.S.; Cônsoli, F.L. Isolation and characterization of actinobacteria ectosymbionts from Acromyrmex subterraneus brunneus (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Microbiol. Res. 2011, 166, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, B.E.R.; Kautz, S.; Wray, B.D.; Moreau, C.S. Dietary specialization in mutualistic acacia-ants affects relative abundance but not identity of host-associated bacteria. Mol. Ecol. 2019, 28, 900–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Microbial Species in Domatia (New GENBANK Accession) Phylum–Class–Order–Family–Species | Closest Taxid Accession nb | Identity (%) | Azt M_C | Ao M_H | Aod M_C | Ad M_H | Aod B_C | Ad B_H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Actinobacteria–Actinobacteria–Micrococcales–Dermacoccaceae | ||||||||

| Flexivirga sp. (MN437546) | MH699193 | 97.56 | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.039 | |||

| Actinobacteria–Actinobacteria–Micrococcales–Microbacteriaceae | ||||||||

| Arthrobacter sp. 1 (MN437547) | KX036592 | 99.00 | 0.127 | 0.027 | 0.037 | 0.023 | 0.020 | |

| Curtobacterium albidum (MN437548) | MK414948 | 99.71 | 0.027 | 0.019 | ||||

| Curtobacterium flaccumfaciens st 4 (MN437549) | KT159381 | 99.54 | 0.045 | 0.020 | ||||

| Curtobacterium luteum st 2 (MN437550) | JQ660282 | 99.70 | 0.055 | 0.019 | 0.020 | |||

| Curtobacterium sp. 1 (MN437551) | MK704290 | 99.90 | 0.023 | |||||

| Curtobacterium sp. 9 (MN437552) | MH915626 | 98.31 | 0.018 | |||||

| Microbacterium sp. 1 (MN437554) | JX566640 | 97.63 | 0.020 | |||||

| Microbacterium sp. 3 (MN437553) | MK578285 | 99.79 | 0.018 | 0.045 | ||||

| Bacteroidetes–Flavobacteriia–Flavobacteriales–Flavobacteriaceae | ||||||||

| Chryseobacterium sp. 1 (MN437556) | LT547832 | 97.00 | 0.055 | |||||

| Chryseobacterium jejuense (MN437555) | KM114947 | 98.00 | 0.018 | 0.037 | ||||

| Elizabethkingia sp. 2 (MN437557) | KP975262 | 95.30 | 0.025 | |||||

| Bacteroidetes–Sphingobacteria–Sphingobacteriales–Sphingobacteriaceae | ||||||||

| Pedobacter sp. 1 (MN437558) | KP708597 | 98.10 | 0.019 | 0.023 | ||||

| Pedobacter sp. 2 (MN437559) | AB461805 | 96.66 | 0.018 | 0.027 | 0.045 | |||

| Firmicutes–Bacilli–Bacillales–Staphylococcaceae | ||||||||

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus (MN437560) | MF157599 | 99.71 | 0.020 | |||||

| Firmicutes–Bacilli–Lactobacillales–Streptococcaceae | ||||||||

| Lactococcus lactis (MN437561) | MF972078 | 99.46 | 0.019 | |||||

| Proteobacteria–Alphaproteobacteria–Rhizobiales–Bradyrhizobiaceae | ||||||||

| Afipia sp. 1 (MN437562) | KY827230 | 99.00 | 0.019 | |||||

| Proteobacteria–Alphaproteobacteria–Rhizobiales–Brucellaceae | ||||||||

| Brucella sp. (MN437563) | CP007717 | 92.54 | 0.019 | 0.045 | ||||

| Ochrobactrum sp. 1 (MN437564) | AY914071 | 100.00 | 0.150 | 0.109 | 0.081 | 0.074 | 0.023 | 0.059 |

| Proteobacteria–Alphaproteobacteria–Rhizobiales–Hyphomicrobiaceae | ||||||||

| Devosia sp. 2 (MN437565) | LC317339 | 99.27 | 0.018 | |||||

| Proteobacteria–Alphaproteobacteria–Rhizobiales–Methylobacteriaceae | ||||||||

| Methylobacterium cf. persicinum (MN437568) | NR_041442 | 99.60 | 0.050 | 0.073 | 0.054 | 0.037 | 0.023 | |

| Methylobacterium cf. phyllostachyos (MN437567) | FR872484 | 99.80 | 0.018 | 0.019 | 0.020 | |||

| Methylobacterium sp. 5 (MN437566) | KC702828 | 99.72 | 0.023 | |||||

| Proteobacteria–Alphaproteobacteria–Rhizobiales–Rhizobiaceae | ||||||||

| Agrobacterium sp. (MN437571) | EU295450 | 98.64 | 0.025 | 0.018 | 0.054 | 0.037 | 0.020 | |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens st 2 (MN437570) | KU240580 | 99.68 | 0.020 | |||||

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens st 3 (MN437569) | KY874047 | 99.62 | 0.019 | |||||

| Rhizobium sp. 1 (MN437573) | LC385714 | 98.29 | 0.027 | |||||

| Rhizobium sp. 4 (MN437574) | KP219134 | 99.71 | 0.027 | 0.020 | ||||

| Rhizobium sp. 5 (MN437572) | MH327921 | 97.54 | 0.025 | 0.039 | ||||

| Proteobacteria–Alphaproteobacteria–Rhizobiales–Xanthobacteraceae | ||||||||

| Labrys sp. 1 (MN437575) | KR778886 | 99.72 | 0.027 | |||||

| Proteobacteria–Alphaproteobacteria–Sphingomonadales–Sphingomonadaceae | ||||||||

| Sphingobium sp. (MN437576) | HM321152 | 98.27 | 0.037 | |||||

| Sphingomonas echinoides (MN437577) | MH725538 | 98.90 | 0.125 | 0.018 | 0.054 | 0.019 | 0.114 | 0.078 |

| Sphingomonas polyaromaticivorans st 1 (MN437578) | HM241216 | 99.63 | 0.027 | |||||

| Proteobacteria–Betaproteobacteria–Burkholderiales–Burkholderiaceae | ||||||||

| Burkholderia contaminans (MN437582) | KY886142 | 99.80 | 0.050 | |||||

| Burkholderia sp. 5 (MN437583) | AB299574 | 98.98 | 0.055 | 0.068 | ||||

| Burkholderia sp. 9 (MN437580) | KX232126 | 98.78 | 0.018 | 0.027 | 0.019 | 0.045 | 0.020 | |

| Burkholderia sp. 21 (MN437581) | JN634250 | 96.51 | 0.018 | |||||

| Burkholderia tropica st 1 (MN437579) | KT390912 | 99.67 | 0.023 | 0.137 | ||||

| Paraburkholderia fungorum (MN437584) | MG576012 | 99.71 | 0.025 | 0.114 | 0.020 | |||

| Proteobacteria–Gammaproteobacteria–Enterobacterales–Enterobacteriaceae | ||||||||

| Cedecea lapagei (MN437585) | MH074798 | 99.39 | 0.039 | |||||

| Enterobacter hormaechei cf subsp xiangfangensis (MN437588) | MG928407 | 99.16 | 0.018 | 0.045 | 0.039 | |||

| Enterobacter sp. 1 (MN437587) | JQ660160 | 99.52 | 0.025 | 0.055 | 0.054 | 0.130 | 0.020 | |

| Enterobacter sp. 5 (MN437586) | KM021337 | 98.58 | 0.018 | |||||

| Enterobacteriaceae sp. 2 (MN437589) | KJ934757 | 98.55 | 0.020 | |||||

| Escherichia sp. (MN437590) | MH465145 | 99.13 | 0.027 | |||||

| Klebsiella aerogenes st 1 (MN437591) | JF494822 | 99.25 | 0.091 | 0.054 | 0.074 | 0.068 | ||

| Klebsiella oxytoca (MN437592) | KT260783 | 98.90 | 0.018 | |||||

| Proteobacteria–Gammaproteobacteria–Enterobacterales–Erwiniaceae | ||||||||

| Pantoea agglomerans (MN437593) | AF130896 | 98.90 | 0.025 | 0.054 | 0.056 | 0.023 | ||

| Pantoea dispersa st 1 (MN437594) | KC182050 | 98.11 | 0.027 | |||||

| Proteobacteria–Gammaproteobacteria–Pseudomonadales–Moraxellaceae | ||||||||

| Acinetobacter cf. bereziniae (MN437596) | MK087738 | 100.00 | 0.025 | 0.081 | 0.020 | |||

| Acinetobacter sp. 2 (MN437597) | JQ433924 | 99.27 | 0.045 | 0.020 | ||||

| Acinetobacter sp. 3 (MN437595) | KR189585 | 99.30 | 0.019 | |||||

| Proteobacteria–Gammaproteobacteria–Pseudomonadales–Pseudomonadaceae | ||||||||

| Pseudomonas cf. aeruginosa (MN437602) | KT943976 | 99.62 | 0.019 | |||||

| Pseudomonas cf. citronellolis (MN437599) | JQ659858 | 99.90 | 0.100 | |||||

| Pseudomonas fulva (MN437603) | KY511074 | 98.95 | 0.019 | |||||

| Pseudomonas nitroreducens (MN437601) | MH675504 | 98.90 | 0.045 | |||||

| Pseudomonas sp. 2 (MN437600) | KJ184870 | 99.90 | 0.037 | 0.020 | ||||

| Pseudomonas sp. 3 (MN437598) | KM187195 | 98.33 | 0.018 | |||||

| Proteobacteria–Gammaproteobacteria–Xanthomonadales–Rhodanobacteraceae | ||||||||

| Luteibacter cf. rhizovinicus st 1 (MN437606) | KY938100 | 99.90 | 0.020 | |||||

| Luteibacter cf. rhizovinicus st 2 (MN437607) | EU022023 | 99.72 | 0.027 | |||||

| Luteibacter sp.1 (MN437604) | FR714940 | 99.25 | 0.018 | 0.054 | 0.037 | |||

| Luteibacter cf. yeojuensis st 2 (MN437605) | KF668474 | 99.90 | 0.050 | 0.055 | 0.081 | 0.093 | 0.091 | 0.176 |

| Luteibacter cf. yeojuensis st 3 (MN437608) | JQ798488 | 98.74 | 0.020 | |||||

| Proteobacteria–Gammaproteobacteria–Xanthomonadales–Xanthomonadaceae | ||||||||

| Pseudoxanthomonas sp. (MN437609) | MH795540 | 99.72 | 0.018 | 0.037 | ||||

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia st 1 (MN437612) | MK537385 | 99.61 | 0.125 | 0.027 | ||||

| Stenotrophomonas panacihumi (MN437610) | KF668484 | 99.35 | 0.025 | 0.018 | 0.054 | 0.019 | 0.059 | |

| Stenotrophomonas sp. 3 (MN437611) | JQ684520 | 99.50 | 0.025 | |||||

| Ascomycota–Dothideomycetes–Pleosporales–Didymellaceae | ||||||||

| Phoma sp. (MN435151) | KP307011 | 99.83 | 0.100 | |||||

| Basidiomycota–Tremellomycetes–Trichosporonales–Trichosporonaceae | ||||||||

| Trichosporon siamense (MN435152) | AB164370 | 99.27 | 0.025 | |||||

| Communities | S | N | C % | Margalef’s DMG | Chao ± SE S | Shannon’s H’ | Simpson D | Inversed Simpson DS | Fisher α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | |||||||||

| Basevie | 37 | 95 | 71.0 | 7.91 | 52.11 ± 9.73 | 3.26 | 0.959 | 18.61 | 22.27 |

| Montagne des Singes | 57 | 186 | 52.9 | 10.72 | 107.75 ± 26.46 | 3.56 | 0.946 | 24.40 | 28.05 |

| Plant species | |||||||||

| C. nodosa | 42 | 120 | 77.8 | 8.56 | 54.00 ± 7.96 | 3.43 | 0.957 | 23. 61 | 22.97 |

| H. physophora | 53 | 161 | 35.9 | 10.23 | 147.50 ± 55.56 | 3.53 | 0.958 | 23.72 | 27.56 |

| Ant species | |||||||||

| A. decemarticulatus | 43 | 106 | 73.1 | 9.01 | 58.83 ± 9.37 | 3.42 | 0.953 | 21.44 | 26.94 |

| A. octoarticulatus | 27 | 55 | 15.0 | 6.49 | 180.00 ± 74.29 | 3.02 | 0.94 | 16.01 | 20.98 |

| A. octoarticulatus demerarae | 35 | 80 | 85.4 | 7.76 | 41.00 ± 4.53 | 3.36 | 0.96 | 23.70 | 23.73 |

| Azteca sp. cf. depilis | 18 | 40 | 61.5 | 4.61 | 29.25 ± 9.53 | 2.64 | 0.9125 | 11.43 | 12.59 |

| Site × Plant | |||||||||

| Basevie × C. nodosa | 21 | 44 | 87.1 | 5.29 | 24.11 ± 3.10 | 2.89 | 0.950 | 15.61 | 15.75 |

| Basevie × H. physophora | 26 | 51 | 48.9 | 6.36 | 53.20 ± 18.16 | 2.93 | 0.946 | 13.20 | 21.24 |

| Montagne des Singes × C. nodosa | 31 | 76 | 50.8 | 6.93 | 61.00 ± 20.92 | 3.15 | 0.924 | 18.51 | 19.53 |

| Montagne des Singes × H. physophora | 40 | 110 | 65.2 | 8.30 | 61.38 ± 13.14 | 3.32 | 0.936 | 20.58 | 22.61 |

| Site × Ant | |||||||||

| Basevie × A. decemarticulatus | 26 | 51 | 48.9 | 6.36 | 53.20 ± 18.16 | 2.93 | 0.953 | 13.20 | 21.24 |

| Basevie × A. octoarticulatus demerarae | 21 | 44 | 87.1 | 5.29 | 24.11 ± 3.10 | 2.89 | 0.912 | 15.61 | 15.75 |

| Montagne des Singes × A. decemarticulatus | 29 | 55 | 68.5 | 6.99 | 42.33 ± 8.84 | 3.15 | 0.924 | 18.56 | 24.83 |

| Montagne des Singes × A. octoarticulatus | 27 | 55 | 15.0 | 6.49 | 180.00 ± 74.29 | 3.02 | 0.94 | 16.01 | 20.98 |

| Montagne des Singes × A. octoarticulatus demerarae | 23 | 36 | 77.7 | 6.14 | 29.6 ± 5.13 | 3.05 | 0.95 | 19.64 | 27.45 |

| Montagne des Singes × Azteca sp. cf. depilis | 18 | 40 | 61.5 | 4.61 | 29.25 ± 9.53 | 2.64 | 0.944 | 11.43 | 12.59 |

| Plant × Ant | |||||||||

| C. nodosa × A. octoarticulatus demerarae | 35 | 80 | 85.4 | 7.76 | 41.00 ± 4.53 | 3.36 | 0.953 | 23.70 | 23.73 |

| C. nodosa × Azteca sp. cf. depilis | 18 | 40 | 61.5 | 4.61 | 29.25 ± 9.53 | 2.64 | 0.938 | 11.43 | 12.59 |

| H. physophora × A. decemarticulatus | 43 | 106 | 73.1 | 9.01 | 58.83 ± 9.37 | 3.42 | 0.958 | 21.44 | 26.94 |

| H. physophora × A. octoarticulatus | 27 | 55 | 15.0 | 6.49 | 180.00 ± 74.29 | 3.02 | 0.913 | 16.01 | 20.98 |

| Site × Plant × Ant | |||||||||

| Basevie × C. nodosa × A. octoarticulatus demerarae | 21 | 44 | 87.1 | 5.29 | 24.11 ± 3.10 | 2.89 | 0.938 | 15.61 | 15.75 |

| Basevie × H. physophora × A. decemarticulatus | 26 | 51 | 48.9 | 6.36 | 53.20 ± 18.16 | 2.93 | 0.944 | 13.20 | 21.24 |

| Montagne des Singes × C. nodosa × A. octoarticulatus demerarae | 23 | 36 | 77.7 | 6.14 | 29. 60 ± 5.13 | 3.05 | 0.948 | 19. 64 | 27.45 |

| Montagne des Singes × C. nodosa × Azteca sp. cf. depilis | 18 | 40 | 61.5 | 4.61 | 29.25 ± 9.53 | 2.64 | 0.913 | 11.43 | 12.59 |

| Montagne des Singes × H. physophora × A. decemarticulatus | 29 | 55 | 68.5 | 6.99 | 42.33 ± 8.84 | 3.15 | 0.936 | 18.56 | 24.83 |

| Montagne des Singes × H. physophora × A. octoarticulatus | 27 | 55 | 15.0 | 6.49 | 180.00 ± 74.29 | 3.02 | 0.924 | 16.01 | 20.98 |

| Shannon’s Richness | Simpson’s Evenness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community 1 vs | Community 2 | t | df | p-Value | t | df | p-Value |

| Basevie | Montagne des Singes | 2.399 | 203.420 | 0.017 * | −1.225 | 143.920 | 0.223 |

| C. nodosa | H. physophora | −0.829 | 274.410 | 0.408 | 0.025 | 264.410 | 0.980 |

| A. decemarticulatus | A. octoarticulatus | 2.646 | 119.85 | 0.009 | −1.085 | 104.410 | 0.281 |

| A. octoarticulatus demerarae | 0.498 | 185.1 | 0.619 | 0.423 | 185.52 | 0.673 | |

| Azteca sp. cf. depilis | 4.854 | 83.287 | <0.001 * | −2.101 | 57.704 | 0.040 | |

| A. octoarticulatus | A. octoarticulatus demerarae | −2.284 | 108.14 | 0.024 | 1.464 | 87.986 | 0.147 |

| Azteca sp. cf. depilis | 2.140 | 89.375 | 0.035 | −1.167 | 74.564 | 0.247 | |

| A. octoarticulatus demerarae | Azteca sp. cf. depilis | 4.562 | 76.011 | <0.001 * | −2.397 | 51.779 | 0.020 |

| Basevie–C. nodosa | Basevie–H. physophora | −0.225 | 92.749 | 0.823 | −0.528 | 87.968 | 0.599 |

| MdS–C. nodosa | −1.783 | 104.080 | 0.077 | 0.655 | 85.616 | 0.514 | |

| MdS–H. physophora | −3.059 | 104.050 | 0.003 * | 1.086 | 70.285 | 0.281 | |

| Basevie–H. physophora | MdS–C. nodosa | −1.313 | 98.465 | 0.192 | 1.074 | 74.704 | 0.286 |

| MdS–H. physophora | −2.387 | 95.101 | 0.019 | 1.399 | 65.154 | 0.167 | |

| MdS–C. nodosa | MdS–H. physophora | −1.286 | 172.780 | 0.200 | 0.491 | 154.160 | 0.624 |

| Basevie–A. dec. | Basevie–A. oct. demer. | 0.225 | 92.749 | 0.823 | 0.528 | 87.968 | 0.599 |

| MdS–A. dec | −1.222 | 100.810 | 0.225 | 1.018 | 86.199 | 0.311 | |

| MdS–A. oct. | −0.475 | 102.62 | 0.636 | 0.606 | 89.906 | 0.546 | |

| MdS–A. oct. demer. | −0.689 | 86.952 | 0.493 | 1.172 | 79.185 | 0.245 | |

| MdS–Azteca sp. | 1.537 | 90.593 | 0.128 | −0.463 | 90.246 | 0.644 | |

| Basevie–A. oct. demer. | MdS–A. dec | −1.635 | 98.523 | 0.105 | 0.601 | 94.668 | 0.550 |

| MdS–A. oct. | −0.780 | 98.949 | 0.437 | 0.090 | 96.931 | 0.929 | |

| MdS–A. oct. demer. | −1.032 | 78.551 | 0.305 | 0.793 | 79.779 | 0.430 | |

| MdS–Azteca sp. | 1.483 | 79.961 | 0.142 | −1.081 | 73.544 | 0.283 | |

| MdS–A. dec | MdS–A. oct. | 0.799 | 109.76 | 0.426 | −0.517 | 109.5 | 0.606 |

| MdS–A. oct. demer. | 0.596 | 87.278 | 0.553 | 0.189 | 88.710 | 0.850 | |

| MdS–Azteca sp. | 2.946 | 87.273 | 0.004 | −1.601 | 70.977 | 0.114 | |

| MdS–A. oct. | MdS–A. oct. demer. | −0.220 | 88.762 | 0.826 | 0.712 | 90.237 | 0.478 |

| MdS–Azteca sp. | 2.14 | 89.375 | 0.035 | −1.167 | 74.564 | 0.247 | |

| MdS–A. oct. demer | MdS–Azteca sp. | 2.401 | 75.388 | 0.019 | −1.767 | 65.232 | 0.082 |

| C. nodosa–A. oct. demer | C. nodosa–Azteca sp. | 4.562 | 76.011 | <0.001 * | −2.397 | 51.779 | 0.020 |

| H. physophora–A. decemarticulatus | −0.498 | 185.100 | 0.619 | −0.423 | 185.520 | 0.673 | |

| H. physophora–A. octoarticulatus | 2.284 | 108.140 | 0.024 | −1.464 | 87.986 | 0.147 | |

| C. nodosa–Azteca sp. | H. physophora–A. decemarticulatus | −4.854 | 83.287 | <0.001 * | 2.101 | 57.704 | 0.040 |

| H. physophora–A. octoarticulatus | −2.140 | 89.375 | 0.035 | 1.167 | 74.564 | 0.247 | |

| H. physophora–A. dec. | H. physophora–A. octoarticulatus | 2.646 | 119.850 | 0.009 | −1.085 | 104.410 | 0.281 |

| Bas.–C. nod.–A. oct. demer | Basevie–H. physophora–A. dec. | −0.225 | 92.749 | 0.823 | −0.528 | 87.968 | 0.599 |

| MdS–C. nodosa–A. oct. demer. | −1.032 | 78.551 | 0.305 | 0.793 | 79.779 | 0.430 | |

| MdS–C. nodosa–Azteca sp. | 1.483 | 79.961 | 0.142 | −1.081 | 73.544 | 0.283 | |

| MdS–H. physophora–A. dec. | −1.635 | 98.523 | 0.105 | 0.601 | 94.668 | 0.550 | |

| MdS–H. physophora–A. oct. | −0.780 | 98.949 | 0.437 | 0.090 | 96.931 | 0.929 | |

| Bas.–H. phy.–A. dec. | MdS–C. nodosa–A. oct. demer. | −0.688 | 86.952 | 0.493 | 1.172 | 79.185 | 0.245 |

| MdS–C. nodosa–Azteca sp. | 1.537 | 90.593 | 0.128 | −0.463 | 90.246 | 0.644 | |

| MdS–H. physophora–A. dec. | −1.222 | 100.810 | 0.225 | 1.018 | 86.199 | 0.311 | |

| MdS–H. physophora–A. oct. | −0.475 | 102.620 | 0.636 | 0.606 | 89.906 | 0.546 | |

| MdS–C. nod.–A. oct. demer | MdS–C. nodosa–Azteca sp. | 2.401 | 75.388 | 0.019 | −1.767 | 65.232 | 0.082 |

| MdS–H. physophora–A. dec. | −0.596 | 87.278 | 0.553 | −0.189 | 88.710 | 0.850 | |

| MdS–H. physophora–A. oct. | 0.220 | 88.762 | 0.826 | −0.712 | 90.237 | 0.478 | |

| MdS–C. nod.–Azteca sp. | MdS–H. physophora–A. dec. | −2.946 | 87.273 | 0.004 | 1.601 | 70.977 | 0.114 |

| MdS–H. physophora–A. oct. | −2.140 | 89.375 | 0.035 | 1.167 | 74.564 | 0.247 | |

| MdS–H. phy.–A. dec. | MdS–H. physophora–A. oct. | 0.799 | 109.760 | 0.426 | −0.517 | 109.500 | 0.606 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ruiz-González, M.X.; Leroy, C.; Dejean, A.; Gryta, H.; Jargeat, P.; Armijos Carrión, A.D.; Orivel, J. Do Host Plant and Associated Ant Species Affect Microbial Communities in Myrmecophytes? Insects 2019, 10, 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects10110391

Ruiz-González MX, Leroy C, Dejean A, Gryta H, Jargeat P, Armijos Carrión AD, Orivel J. Do Host Plant and Associated Ant Species Affect Microbial Communities in Myrmecophytes? Insects. 2019; 10(11):391. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects10110391

Chicago/Turabian StyleRuiz-González, Mario X., Céline Leroy, Alain Dejean, Hervé Gryta, Patricia Jargeat, Angelo D. Armijos Carrión, and Jérôme Orivel. 2019. "Do Host Plant and Associated Ant Species Affect Microbial Communities in Myrmecophytes?" Insects 10, no. 11: 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects10110391

APA StyleRuiz-González, M. X., Leroy, C., Dejean, A., Gryta, H., Jargeat, P., Armijos Carrión, A. D., & Orivel, J. (2019). Do Host Plant and Associated Ant Species Affect Microbial Communities in Myrmecophytes? Insects, 10(11), 391. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects10110391