Simple Summary

The abundance of bark beetles is generally explained by resource-related parameters. The bark beetle Phloeotribus rhododactylus feeds mainly on the shrub Cytisus scoparius. Other host plants include Spartium junceum, Cytisus sp., Ulex europaeus, Calicotome sp., Coronilla emeroides, Genista florida, Adenocarpus complicatus, and Ficus carica. Phloeotribus rhododactylus seems to have a stable range that is centred in Western Europe and extends to Eastern Europe. Its abundance is highest in Western Europe and decreases to the east, which coincides with the distribution of the host tree, Cytisus scoparius. Even though Cytisus scoparius is an invasive plant in agricultural and natural ecosystems out of Europe, Phloeotribus rhododactylus has not been found in any of the areas invaded by Cytisus scoparius.

Abstract

The bark beetle Phloeotribus rhododactylus feeds mainly on the shrub Cytisus scoparius. The range of P. rhododactylus extends from Spain in the south to southern Sweden, Denmark, and Scotland in the north. Its range to the east extends to Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary, but single localities are known further east in Romania, Bulgaria, and Greece. It is clear that the range of the beetle matches that of its main host. C. scoparius is adapted to Mediterranean and coastal climates, and its range is limited by low winter temperatures. P. rhododactylus is, therefore, rare in Central Europe. It infests either individuals of C. scoparius that have been damaged by mammalian herbivores or snow or that are drought-stressed. Although C. scoparius is an invasive plant in agricultural and natural ecosystems, P. rhododactylus has not been found in any of the areas where C. scoparius has invaded.

1. Introduction

Scolytinae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) includes both bark and ambrosia beetles and represents species of major economic and ecological importance in forests worldwide [1,2]. Most scolytine species feed on recently cut or injured tissues of woody plants, and such feeding can cause massive tree mortality depending on both tree health and beetle abundance [3,4,5].

Although weakened trees (i.e., wind-fallen, fire-injured, water-stressed, or trees damaged by other biotic factors) are highly attractive to Scolytinae, healthy trees are rarely attacked [6], and less than 1% of scolytine species regularly kill healthy standing trees [7]. Scolytinae affect forest dynamics by contributing to decomposition and nutrient cycling [3,8].

The absolute majority of Scolytinae beetles perforate the bark of trees and dig galleries near the cambium, but bark and ambrosia beetles differ in their feeding strategies. Bark beetles are mostly monophagous or oligophagous species that feed directly on phloem tissues (i.e., phloemophagy), whereas ambrosia beetles are polyphagous species that feed on fungi that they introduce and cultivate in their galleries (i.e., xylomycetophagy) and on xylem [6,9,10,11]. The lack of host specificity contributes to the invasiveness of ambrosia beetles in many forest ecosystems [12,13].

Scolytinae have been studied more than any other group of forest insects, but most investigations have been restricted to only a few pest species; see [14]. The abundance of scolytids is generally explained by resource-related parameters. In contrast to their abundance, the pest status of scolytids was previously found to be significantly related to species-specific traits, such as body size and maximum number of generations per year [14]. The latter study did not include the bark beetle Phloeotribus rhododactylus (Marsham, 1802) because information on its hosts was lacking [14].

Phloeotribus rhododactylus feeds mainly on the shrub Cytisus scoparius (L.) Link, 1822. Other host plants include Spartium junceum L., 1753; Cytisus sp., Ulex europaeus L., 1753; Calicotome sp.; Coronilla emeroides Boiss. & Spruner, 1843; Genista florida L., 1759; Adenocarpus complicatus (L.) J. Gay ex Gren. & Godr., 1848; and Ficus carica L., 1753 [15,16,17]. This bark beetle was previously reported to occur mainly in Western Europe and, to a lesser degree, in Central Europe, where its occurrence diminishes to the east [15]. Although C. scoparius is known to occur in most areas in Central Europe, P. rhododactylus has been considered rare in Central Europe [18,19].

The objectives of the current study were to summarize the occurrence of P. rhododactylus in Europe and to determine whether it remains rare in the Czech Republic.

2. Bionomics of Phloeotribus rhododactylus

Phloeotribus rhododactylus feeds under the bark of the branches of Cytisus scoparius, Spartium junceum, and other shrubs. The larval corridors are long and sparse. It has only one generation per year. It flies in May, the larvae mature during the summer, and new beetles hatch at the end of the summer. The new beetles remain where they hatch for an extended period of maturation feeding and then overwinter [15]. The exit holes are round with diameters of 0.7 ± 0.2 mm (n = 40). The gallery system is in the shape of the letter Y with a width of 1.1 ± 0.1 mm and a length of 10–16 mm (n = 10); the larval corridors are 12–15 mm long (Figure 1; the photographs in this figure were taken with a TSC5005-S951B-V3 mobile camera with a resolution of 5.0 Mpx with a millimetre scale; measurements were made with the web application www.cnspg.cz/mince/index.php).

Figure 1.

Galleries (A) and exit holes (B) of Phloeotribus rhododactylus.

Little is known about the pheromone communication of P. rhododactylus. The spriroacetal, (E)-conophthorin, which has previously been reported from Hylesinus varius (Fabricius, 1775) [20] and Taphrorychus bicolor (Herbst, 1793) [21], was identified in the frass produced by boring beetles of P. rhododactylus. The antennae of P. rhododactylus, however, provided no clues about P. rhododactylus pheromones due to experimental difficulties with antennal preparation [22].

Phloeotribus rhododactylus may be a vector of the fungus Geosmithia langdonii (Kolařík, Kubátová and Pažoutová, 2005), although the latter authors studied only one specimen of the beetle [23].

Geosmithia sp. is a yeast and is found much less frequently in bark beetles in comparison with other yeasts or ophiostomatoid fungi [24]. Geosmithia sp. is also able to produce enzymes that can degrade lignocellulose-like substances [25]. The yeast converts food into an aggregation pheromone [26,27]. At the same time, a large population of yeasts in a weakened tree can increase its infestation by bark beetles [28]. In contrast, the defences of a healthy tree can reduce the diversity of yeasts that it supports [29].

Overall, yeasts are important to bark beetles; i.e., they affect beetle competitiveness and production of semiochemicals, serve as a food supplement, and influence the distribution of microorganisms that can affect the beetles in the subcortical environment [30,31]. Yeast development is affected by temperature. Yeast cannot survive at temperatures above 39 °C, and the optimum temperature range is 27–30 °C [32]. That temperature range is also the developmental optimum for bark beetles [33,34,35,36,37].

3. Common Broom Cytisus scoparius

Cytisus scoparius, the common broom or Scotch broom, is a perennial leguminous shrub native to all Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East [38]. Plants of C. scoparius typically grow to 1–3 m (3.3–9.8 ft) tall, rarely to 4 m (13 ft), with main stems up to 5 cm (2.0 in) thick, rarely 10 cm (3.9 in). The shrubs have green shoots with small deciduous trifoliate leaves 5–15 mm long, and in spring and summer, they are covered in profuse golden yellow flowers 20–30 mm from top to bottom and 15–20-mm wide.

This species is adapted to Mediterranean and coastal climates, and its range is limited by cold winter temperatures. Especially the seeds, seedlings, and young shoots are sensitive to frost, but adult plants are hardier, and branches affected by freezing temperatures regenerate quickly [39,40,41].

C. scoparius is found in sunny sites, usually on dry, sandy soils at low altitudes, tolerating very acidic soil conditions [39]. In some places outside of its native range, such as India, South America, western North America—particularly Vancouver Island, Washington, Oregon, and California, and west of the Cascade and Sierra Nevada mountains—Australia, and New Zealand (where it is a declared weed), it has become an ecologically destructive colonizing invasive species in grassland, shrub and woodland, and other habitats [42]. Over some parts of its native range, C. scoparius is an invasive plant in agricultural and natural ecosystems. In France, it is often considered an occupying species that preferentially colonizes abandoned pastures [43].

4. Geographic Range of Phloeotribus rhododactylus

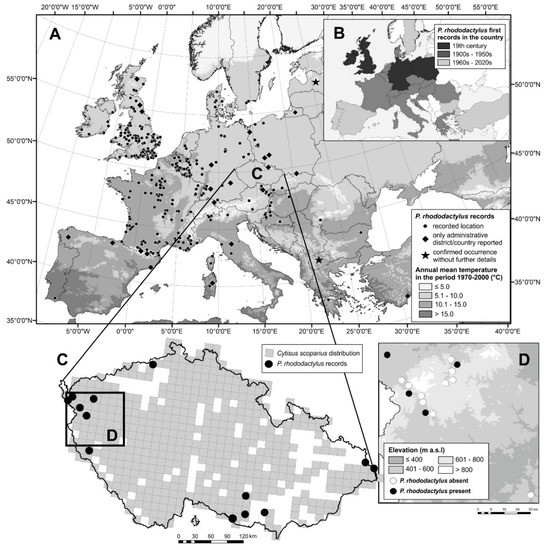

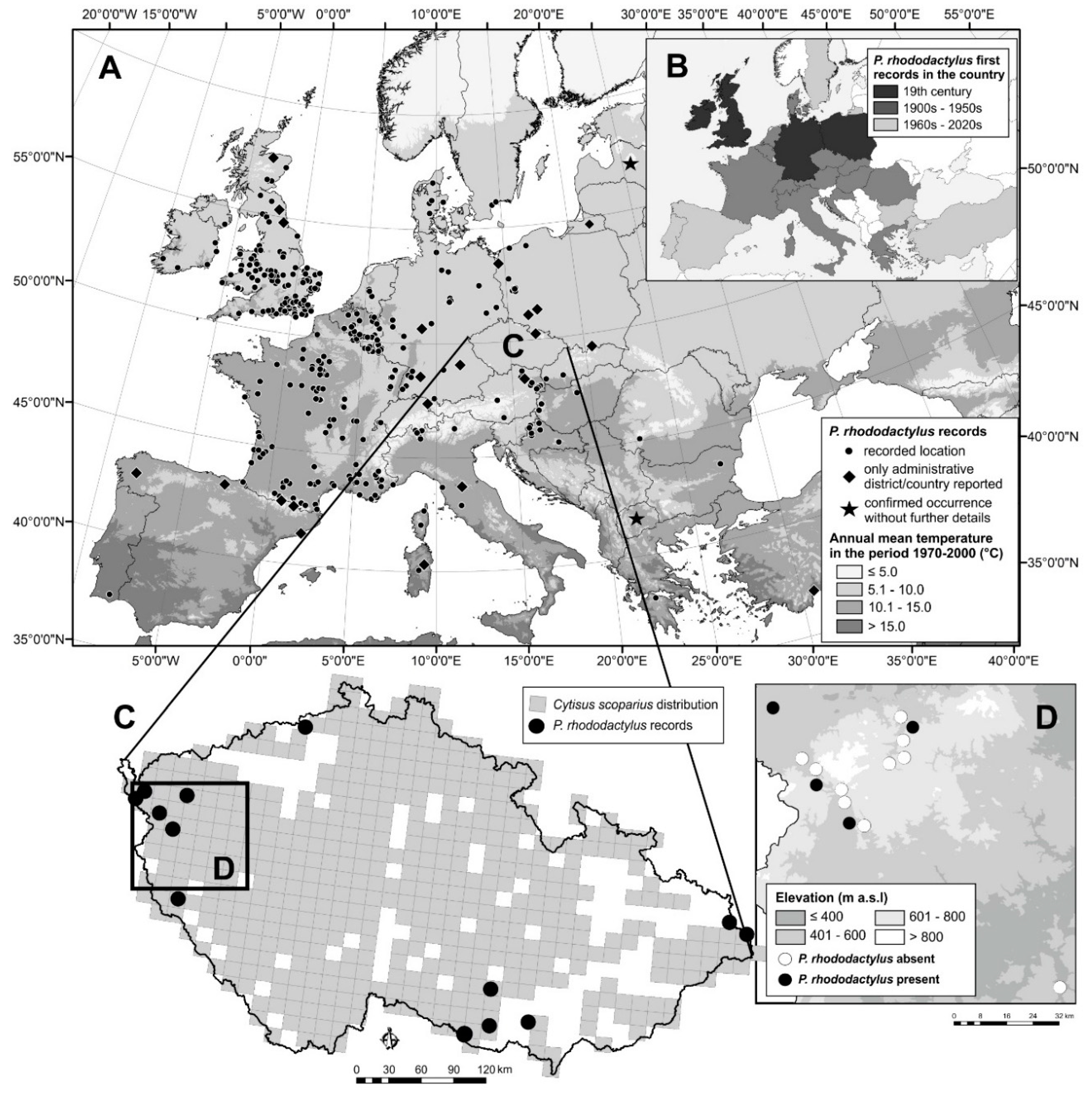

The occurrence of P. rhododactylus has been already known in Western and Central Europe for a long time. In most countries, the first records date back to the 1950s, and only in few countries has it been reported later in the second part of the 20th century (Figure 2A,B), something that could be potentially associated with the low abundance of the insect. Even in one of the most comprehensive works on bark beetles based on extensive research by the author [44,45], the records of P. rhododactylus were mainly concentrated in Western Europe, being significantly rarer in the east [15].

Throughout the natural distribution of P. rhododactylus, we found records of its occurrence at 357 specific localities (Table 1). The number of localities is much greater for Western Europe (Great Britain, Germany, and France) than for Central or Eastern Europe (Figure 2A).

Table 1.

Known localities of Phloeotribus rhododactylus in Europe. Data and localities are summarized based on the literature available from Google Scholar, Zobodat, Biodiversity Heritage Library, and www.gbif.org.

The range of P. rhododactylus extends to Spain (probably northern Spain) in the south and to southern Sweden, Denmark, and Scotland in the north. The range to the east extends to Poland, Slovakia, and Hungary, but single localities are known further to the east in Romania, Bulgaria, and Greece (Figure 2A). It is likely that the small number of sites in south and east Europe is due to a lack of literary resources and not to the natural absence of beetles in these countries. Occurrences in Latvia and Macedonia have been reported but without designation of the specific locality [91].

Although P. rhododactylus occurs throughout Europe (Figure 2A) [91], it appears to be a Euro-Mediterranean species [92]. It is also widespread in non-European countries, such as Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Madeira, Tunisia, and Iran [91]. Its abundance is highest Western Europe and decreases to the north and east. Its current distribution (Figure 2A) appears to be similar to that reported in 1955 [15].

The range of P. rhododactylus matches that of its main host, C. scoparius. C. scoparius is adapted to milder climates and its range is limited by cold winter temperatures. Although adult plants are relatively hardy, the seeds, seedlings, and young shoots of C. scoparius are sensitive to frost [39,40,41]. Its occurrence to the east (Russia and Ukraine) is sporadic [93].

C. scoparius has become an ecologically destructive invasive species in grasslands, shrublands, woodlands, and other habitats in India, South America, western North America, Australia, and New Zealand [42]. P. rhododactylus has not been found in any of the areas invaded by C. scoparius [3,94].

Figure 2.

Localities (or countries and counties) where Phloeotribus rhododactylus has been reported to occur in Europe with annual mean temperature (A) (see Table 1); periods of its first reports in countries (B); occurrence of Phloeotribus rhododactylus with Cytisus scoparius in the Czech Republic (https://portal.nature.cz/nd/) (see Table 2) (C,D) in a recent study in western Bohemia, reported here (List of localities where Phloeotribus rhododactylus was not found in the study conducted by T. Fiala in 2020 in western Bohemia: Bečov na Teplou (50.0858942 N, 12.8625314 E); Blovice (49.5961411 N, 13.5222964 E); Dolní Žandov (50.0175272 N, 12.5845317 E); Dolní Žandov—Manský dvůr (50.0356972 N, 12.5319819 E); Kfely (50.1607864 N, 12.8421089 E); Mariánské Lázně (49.9555339 N, 12.6991647 E), NR Lazurový vrch (49.9135836 N, 12.7724494 E); NR Údolí Teplé (50.0554547 N, 12.8287328 E); Valy (49.9824786 N, 12.6813111 E); Vodná (50.1106978 N, 12.8631644 E)). NR—Natural Reserve.

Table 2.

Known localities of Phloeotribus rhododactylus in the Czech Republic. Data were excerpted from the literature, as well from private collections and from unpublished entomological reports (NM—Natural Monument; NR—Natural Reserve). Collection of data by T. Fiala in 2020 is described in this report.

Figure 2.

Localities (or countries and counties) where Phloeotribus rhododactylus has been reported to occur in Europe with annual mean temperature (A) (see Table 1); periods of its first reports in countries (B); occurrence of Phloeotribus rhododactylus with Cytisus scoparius in the Czech Republic (https://portal.nature.cz/nd/) (see Table 2) (C,D) in a recent study in western Bohemia, reported here (List of localities where Phloeotribus rhododactylus was not found in the study conducted by T. Fiala in 2020 in western Bohemia: Bečov na Teplou (50.0858942 N, 12.8625314 E); Blovice (49.5961411 N, 13.5222964 E); Dolní Žandov (50.0175272 N, 12.5845317 E); Dolní Žandov—Manský dvůr (50.0356972 N, 12.5319819 E); Kfely (50.1607864 N, 12.8421089 E); Mariánské Lázně (49.9555339 N, 12.6991647 E), NR Lazurový vrch (49.9135836 N, 12.7724494 E); NR Údolí Teplé (50.0554547 N, 12.8287328 E); Valy (49.9824786 N, 12.6813111 E); Vodná (50.1106978 N, 12.8631644 E)). NR—Natural Reserve.

5. Occurrence of Phloeotribus rhododactylus on the Eastern Edge of Its Range

In the last 60 years, P. rhododactylus has been detected in only 14 localities in the Czech Republic, with eight of them being after 2000 (Table 2). The localities lie at altitudes ranging from 290 to 1000 m a.s.l., but most of the localities are between 300 and 600 m a.s.l. (Figure 2C,D). An exception is the locality of the Velká Čantoryje Mt., which was deforested in the past, which allowed the occurrence of the Scotch broom and, subsequently, thanks to the connectivity of the landscape, also the bark beetle. In recent years, the species has been detected only in the western and south-eastern part of the country. P. rhododactylus has been known in the south-eastern Czech Republic since the 1920s [96], where the presence of a large population has been repeatedly confirmed (Table 2). We consider the localities in the northern and eastern part of the Czech Republic to be historical, because the species has not been recently reported from either area.

C. scoparius is abundant only in two areas where P. rhododactylus is known to occur (https://portal.nature.cz/publik_syst/nd_nalez-public.php?idTaxon=36486). Although C. scoparius is found almost everywhere, its distribution is uneven, and the sizes (areas) of the stands are not known. We suspect that large areas of C. scoparius, especially large areas that are near other large areas, have an increased probability of containing P. rhododactylus. The absence of large stands of C. scoparius in eastern Czech Republic probably explains the absence of P. rhododactylus in that part of the country (J. Holuša observ.).

In the western part of the country (Bohemia), in 2020, the first author inspected more than 10 weakened or dead C. scoparius branches in each of the 15 localities in which C. scoparius occupied more than 0.1 ha. P. rhododactylus occurrence was determined based on the presence of galleries (Figure 1A) and exit holes (Figure 1B). Rods were placed in emergence traps, and captured beetles were reared at 20 °C and light-dark 16-8 hrs. The beetles were identified to species level by the first author based on Pfeffer [15]. With these methods, P. rhododactylus was found in four localities (Table 2, Figure 2D) at altitudes ranging from 450 to 580 m a.s.l. They appeared consistently on shrubs that were damaged by game beating (90%) or broken by wet snow (10%). The beetles infested the lower third of trunks that were 1.5–2.5 cm in diameter. Exit holes numbered about five per m of branch, but thousands of entry holes per m of shrub were previously reported from Popice in south-eastern Czech Republic [95]. We suggest that this difference in P. rhododactylus abundance between the western and south-eastern regions of the Czech Republic can be explained by the drought and higher temperatures that occur in the south-eastern region [99]. Under severe water stress, trees may lack sufficient kino, resin, or latex to resist attack and are, therefore, more likely to be attacked by wood borers, secondary bark beetles, and latent pathogens [100,101].

6. Conclusions

Phloeotribus rhododactylus seems to have a stable range that is centred in Western Europe and extends to Eastern Europe. Its abundance is highest in Western Europe and decreases to the east, which coincides with the distribution of the host tree, C. scoparius. P. rhododactylus is a rare species in Central Europe. It occupies trees or shrubs that have been damaged or that are drought-stressed. It is possible that weak pheromone communication and weak interactions with fungi also contribute to its rare occurrence.

As is the case for abundance of most bark beetles [14], the abundance of P. rhododactylus can apparently be explained by resource-related parameters.

Author Contributions

Data curation, T.F.; Formal analysis, J.H.; Methodology, T.F.; Writing—original draft, T.F. and J.H.; Writing—review and editing, T.F. and J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the grant “Advanced research supporting the forestry and wood-processing sector’s adaptation to global change and the 4th industrial revolution,” No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000803, financed by OP RDE.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Bruce Jaffee (U.S.A.) for editorial and linguistic improvement of the manuscript. The authors also thank Václav Týr (Žihle), Jiří Procházka (Moravské zemské muzeum, Brno), and Jiří Vávra (Ostravské muzeum, Ostrava) for providing data from their private or museum collections.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Raffa, K.F.; Aukema, B.H.; Bentz, B.J.; Carroll, A.L.; Hicke, J.A.; Turner, M.G.; Romme, W.H. Cross-scale Drivers of Natural Disturbances Prone to Anthropogenic Amplification: The Dynamics of Bark Beetle Eruptions. Bioscience 2008, 58, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weed, A.S.; Ayres, M.P.; Hicke, J.A. Consequences of climate change for biotic disturbances in North American forests. Ecol. Monogr. 2013, 83, 441–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.L. The bark and ambrosia beetles of North and Central America (Coleoptera: Scolytidae), a taxonomic monograph. Great Basin Nat. Mem. 1982, 6, 1–1359. [Google Scholar]

- Kausrud, K.; Økland, B.; Skarpaas, O.; Grégoire, J.-C.; Erbilgin, N.; Stenseth, N.C. Population dynamics in changing environments: The case of an eruptive forest pest species. Biol. Rev. 2011, 87, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, B.J.; Donato, D.C.; Turner, M.G. Recent mountain pine beetle outbreaks, wildfire severity, and postfire tree regeneration in the US Northern Rockies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 15120–15125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, S.L. The Bark and Ambrosia Beetles of South America (Coleoptera: Scolytidae); Brigham Young University: Provo, UT, USA, 2007; p. 900. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkendall, L.R.; Biedermann, P.H.W.; Jordal, B.H. Evolution and diversity of bark and ambrosia beetles. In Bark Beetles: Biology and Ecology of Native and Invasive Species; Vega, F.E., Hofstetter, R.W., Eds.; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 85–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronque, M.U.V.; Flechtmann, C.A.; Lopes, J. Scolytidae (Coleoptera) in forest fragment of semideciduous tropical forest and reforestation of riparian vegetation in southern of Brazil. In Proceedings of the 49th Annual Meeting of The Association for Tropical Biology and Conservation, Bonito, Brazil, 18–22 June 2012; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, T.H.; Equihua-Martinez, A. Biology of Bark and Ambrosia Beetles (Coleoptera: Scolytidae and Platypodidae) of a Tropical Rain Forest in Southeastern Mexico with an Annotated Checklist of Species. Ann. Èntomol. Soc. Am. 1986, 79, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulcr, J.; Kolařík, M.; Kirkendall, L.R. A new record of fungus- beetle symbiosis in Scolytodes bark beetles (Scolytinae, Curculionidae, Coleoptera). Symbiosis 2007, 43, 151–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hulcr, J.; Atkinson, T.H.; Cognato, A.I.; Jordal, B.H.; McKenna, D.D. Morphology, taxonomy, and phylogenetics of bark beetles. In Bark Beetles: Biology and Ecology of Native and Invasive Species; Vega, F.E., Hofstetter, R.W., Eds.; Elsevier: San Diego, CA, USA, 2015; pp. 41–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkendall, L.R.; Cortivo, M.D.; Gatti, E. First record of the ambrosia beetle, Monarthrum mali (Curculionidae, Scolytinae) in Europe. J. Pest Sci. 2008, 81, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkendall, L.R.; Faccoli, M. Bark beetles and pinhole borers (Curculionidae, Scolytinae, Platypodinae) alien to Europe. ZooKeys 2010, 56, 227–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussler, H.; Bouget, C.; Brustel, H.; Brändle, M.; Riedinger, V.; Brandl, R.; Müller, J. Abundance and pest classification of scolytid species (Coleoptera: Curculionidae, Scolytinae) follow different patterns. For. Ecol. Manag. 2011, 262, 1887–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, A. Fauna ČSR. Svazek Kůrovci—Scolytoidea (Řád: Brouci–Coleoptera); Československá Akademie Věd: Praha, Czech Republic, 1955; p. 340. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, A. Revision der Gattung Phloeophthorus Wollaston (Coleoptera, Scolytidae). Acta Entomol. Bohemoslov. 1972, 69, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardero, M.J. Plantas huésped y escolítidos (Col.: Scolytidae) en Galicia (Noroeste de la Península Ibérica). Bol. Sanid. Veg. Plagas 1995, 21, 357–370. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, A. Kůrovci (Scolytoidea)—Fauna ČSR 6—Dodatek. Acta Entomol. Bohemoslov. 1965, 62, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, A. Kůrovcovití Scolytidae a Jádrohlodovití Platypodidae; Academia: Praha, Czech Republic, 1989; p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- Francke, W.; Hindorf, G.; Reith, W. Alkyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[4.5]-decanes—A new class of pheromones. Naturwissenschaften 1979, 66, 618–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallara, P.L.; Seybold, S.J.; Meyer, H.; Tolasch, T.; Francke, W.; Wood, D.L. Semiochemicals from Three Species of Pityophthorus (Coleoptera: Scolytidae): Identification and Field Response. Can. Èntomol. 2000, 132, 889–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.-H.; Tolasch, T.; Schlyter, F.; Francke, W. Enantiospecific antennal response of bark beetles to spiroacetal (E)-conophthorin. J. Chem. Ecol. 2002, 28, 1839–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolařík, M.; Kubátová, A.; Hulcr, J.; Pažoutová, S. Geosmithia Fungi are Highly Diverse and Consistent Bark Beetle Associates: Evidence from their Community Structure in Temperate Europe. Microb. Ecol. 2008, 55, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubátová, A.; Kolařík, M.; Prášil, K.; Novotný, D. Bark beetles and their galleries: Well-known niches for little known fungi on the example of Geosmithia. Czech. Mycol. 2004, 56, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselská, T.; Skelton, J.; Kostovčík, M.; Hulcr, J.; Baldrian, P.; Chudíčková, M.; Cajthaml, T.; Vojtová, T.; Garcia-Fraile, P.; Kolařík, M. Adaptive traits of bark and ambrosia beetle-associated fungi. Fungal Ecol. 2019, 41, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falsen, E.; Leufvén, A.; Bergström, G. Interconversion of verbenols and verbenone by identified yeasts isolated from the spruce bark beetle Ips typographus. J. Chem. Ecol. 1984, 10, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, D.W.A.; Borden, J.H. Conversion of verbenols to verbenone by yeasts isolated from Dendroctonus ponderosae (Coleoptera: Scolytidae). J. Chem. Ecol. 1990, 16, 1385–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leufvén, A.; Nehls, L. Quantification of different yeasts associated with the bark beetle, Ips typographus, during its attack on a spruce tree. Microb. Ecol. 1986, 12, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, F.N.; González, E.; Gómez, Z.; López, N.; Cesar, H.-R.; Berkov, A.; Zúñiga, G. Gut-associated yeast in bark beetles of the genus Dendroctonus Erichson (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2009, 98, 325–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Davis, T.S. The Ecology of Yeasts in the Bark Beetle Holobiont: A Century of Research Revisited. Microb. Ecol. 2014, 69, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedermann, P.H.W.; Vega, F.E. Ecology and Evolution of Insect–Fungus Mutualisms. Annu. Rev. Èntomol. 2020, 65, 431–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaham, R.Z. The yeasts associated with bark beetles. For. Sci. 1960, 6, 146–154. [Google Scholar]

- Baier, P.; Pennerstorfer, J.; Schopf, A. PHENIPS—A comprehensive phenology model of Ips typographus (L.) (Col., Scolytinae) as a tool for hazard rating of bark beetle infestation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2007, 249, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baier, P.; Pennerstorfer, J.; Schopf, A. Online-monitoring of the phenology and the development of Ips typographus (L.) (Col., Scolytinae). Mitt. Dtsch. Ges. Allg. Angew. Entomol. 2009, 17, 155–158. [Google Scholar]

- Öhrn, P.; Lindelöw, Å.; Långström, S. Flight activity of the ambrosia beetles Trypodendron leave and Trypodendron lineatum in relation to temperature in southern Sweden. In Biotic Risks and Climate Change in Forests; Delb, H., Pontuali, S., Eds.; Forest Research Institute of Baden-Württemberg: Freiburg, Germany, 2011; pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar]

- Schebeck, M.; Schopf, A. Temperature-dependent development of the European larch bark beetle, Ips cembrae. J. Appl. Èntomol. 2016, 141, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galko, J.; Økland, B.; Kimoto, T.; Rell, S.; Zúbrik, M.; Kunca, A.; Vakula, J.; Gubka, A.; Nikolov, C. Testing temperature effects on woodboring beetles associated with oak dieback. Biologia 2018, 73, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutin, T.G.; Heywood, V.H.; Burges, N.A.; Moore, D.M.; Valentine, D.H.; Walters, S.M.; Webb, D.A. Flora Europaea; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1968; Volume 2, p. 486. [Google Scholar]

- Blamey, M.; Grey-Wilson, C. Illustrated Flora of Britain and Northern Europe; Hodder & Stoughton: London, UK, 1989; p. 544. [Google Scholar]

- Vedel, H.; Lange, J. Trees and Bushes; Metheun: London, UK, 1960; p. 224. [Google Scholar]

- Bean, W.J. Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles; John Murray: London, UK, 1978; p. 784. [Google Scholar]

- Zarri, A.A.; Rahmani, A.R.; Behan, M.J. Habitat modifications by Scotch broom Cytisus scoparius invasion of grasslands of the Upper Nilgiris in India. J. Bombay Nat. History Soc. 2006, 103, 356–365. [Google Scholar]

- Prévosto, B.; Robert, A.; Coquillard, P. Development of Cytisus scoparius L. at stand and individual level in a mid-elevation mountain of the French Massif Central. Acta Oecol. 2004, 25, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, A. Insekten als Indikatoren von Veränderungen in der Bestandzusammensetzung der südböhmischen Moore. Quaest. Geobiol. 1976, 16, 75–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, A. Taxonomischer Status von Pityogenes bistridentatus (Eichhoff) und die an Schwarzkiefer (Pinus nigra) lebenden Borkenkäfer (Coleoptera, Scolytidae). Acta Entomol. Bohemoslov. 1984, 81, 271–279. [Google Scholar]

- Prossen, T.I. Nachtrag zum Verzeichnisse der bisher in Kärnten beobachteten Käfer. Carinthia II 1913, 103, 74–85. [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann, H.E. Ueber die geographische Verbreitung der Ipiden (Col.) II. Die Ipidenfauna Niederösterreichs und des nördlichen Burgenlandes. Koleopterol. Rundsch. 1927, 13, 42–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pittioni, E. Die Käfer von Niederdonau. Die Curti-Sammlung im Museum des Reichsgaues Niederdonau. Cerambycidae-Scolytidae. Niederdonau Nat. Kult. 1943, 23, 131–189. [Google Scholar]

- Holzschuh, C. Bemerkenswerte Käferfunde in Österreich. Ein Beitrag zur Faunistik und Ökologie mitteleuropäischer Käfer. Mitt. Forstl. Bundes-Vers. Wien 1971, 94, 3–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hellrigl, K. Forstliche Aspekte und Faunistik der Borkenkäfer Südtirols (Coleoptera, Scolytidae). For. Obs. 2012, 6, 139–180. [Google Scholar]

- Phloeotribus rhododactylus Marsham. Available online: https://www.gbif.org/species/1204366 (accessed on 6 April 2020).

- Langhoffer, A. Scolytidae Croatiae. Entomol. Bl. 1915, 7–9, 154–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, V. Barkbiller Med et Biologisk Afsnit; G.E.C. Gads Forlag: København, Denmark, 1956; p. 196. [Google Scholar]

- Balachowsky, A. Faune de France Coléopteres Scolytides; Librairie de la Faculte des Sciences: Paris, France, 1949; p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Lessieur, D. Contribution à la liste des Curculionidae (Coleoptera Curculionidae) observés récemment en Gironde. Bull. Soc. Linn. Bordx. 2017, 45, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Redtenbacher, L. Fauna Austriaca. Die Käfer; Verlag von Carl Gerold: Wien, Austria, 1849; p. 883. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn, M. Neue Käfer der Niederelbfauna. Verh. Ver. Naturwissensch. Unterhalt. Hambg. 1904, 12, 101–102. [Google Scholar]

- Kleine, R. Die geograpische Verbreitung der Ipiden. Entomol. Bl. 1912, 12, 298–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kleine, R. Die geograpische Verbreitung der Ipiden. II. Das paläarktische europäisch-sibirische Fauneugebiet. Entomol. Bl. 1912, 10/11, 261–270. [Google Scholar]

- Lauterborn, R. Faunistische Beobachtungen aus dem Gebiete des Oberrheins und des Bodensees. Mitt. Badischen Landesver. Nat. Nat. Freibg. Breisgau 1922, 4, 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp, H.J. Zur Insekten-Faunistik Südwestdeutschlands Coleoptera: Scolytidae und Platypodidae. Mitt. Entomol. Ver. Stuttg. 1978, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kamp, H.J. Borkenkäfer aus dem Museum für Naturkunde in Freiburg i.Br. (Coleoptera, Scolytidae). Mitt. Badischen Landesver. Nat. Nat. Freibg. Br. 1985, 13, 409–413. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, M. Coleopterologische Neu- und Wiederfunde in Sachsen-Anhalt. Entomol. Nachr. Ber. 2001, 45, 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Reike, H.-P.; Sobczyk, T. Aktuelle Situation der Borkenkäfer (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) in Sachsen. Sächs. Entomol. Z. 2007, 2, 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Schedl, K.E. Die Borkenkäfer von Griechenland und Cypern. Beitrag zur Morphologie und Systematik der Scolytoidea. Not. Entomol. 1967, 47, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Endrödi, S. Fundortsangaben über die Borkenkäfer (Scolytidae) des Karpatenbeckens. Folia Entomol. Ung. 1958, 11, 21–43. [Google Scholar]

- Podlussány, A. Curculionoidea (Coleoptera) of Örség Landscape Conservation Area. Natural History of Orség Landscape Conservation Area II. Sav. Múz. Szombh. 1996, 23, 203–273. [Google Scholar]

- Podlussány, A.; György, Z. A Mátra Múzeum bogárgyüjteménye. Coleoptera: Curculionoidea: Anthribidae, Apionidae, Attelabidae, Curculionidae, Nanophyidae, Rhynchitidae, Scolytidae, Urodontidae. Folia Hist. Nat. Musei Matra. 2008, 32, 183–200. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, J.P.; Winter, T.G.; Good, G.A. A review of the irish Scolytidae (Insecta: Coleoptera). Irish Nat. J. 1991, 23, 403–409. [Google Scholar]

- Cecconi, G. Illustrazione di quasti operati da animali su piante legnose italiane. III. Parte. Stazioni Sper. Agrar. Ital. 1906, 39, 945–992. [Google Scholar]

- Russo, G. Contributo alla conoscenza degli Scolitidi. II. Ilesini dell´olivo. Boll. Lab. Zool. Portici 1932, 26, 89–114. [Google Scholar]

- Colonnelli, E. A revised checklist of italian Curculionoidea (Coleoptera). Zootaxa 2003, 337, 1–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, E. I Coleotteri Scolitidi e Platipodidi dela Sardegna (Coleoptera: Scolytidae, Platypodidae). Conserv. Habitat Invertebr. 2011, 5, 609–639. [Google Scholar]

- Gerend, R. Nachweise neuer und bemerkenswerter Käfer für die Fauna Luxemburgs (Insecta, Coleoptera). Bull. Soc. Nat. Luxemb. 2008, 109, 107–132. [Google Scholar]

- Braunert, C. Die Rüsselkäferfauna (Coleoptera, Curculionoidea) der Silikatmagerrasen im nördlichen Luxemburg. Ferrantia 2017, 76, 1–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cuppen, J.G.M. Entomofauna van de Gooi- en Vechtstreek. Entomol. Ber. 2012, 72, 151–174. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt, J. Neue Fundorte seltenerer schlesischer Käfer aus dem Jahre 1898 und Bemerkungen. Z. Entomol. Breslau 1898, 24, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Nunberg, M. Klucze do Oznaczania Owadów Polski. Część XIX. Chrząszcze—Coleoptera. Korniki—Scolytidae, Wyrynniki—Platypodidae; Państwowe wydawnictwo naukowe: Warszawa, Poland, 1981; p. 115. [Google Scholar]

- Konwerski, S.; Mleczak, M. New records of Phloeotribus rhododactylus (Marsham, 1802) (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) from Poland. Wiadomości. Entomol. 2001, 20, 88. [Google Scholar]

- Mokrzycki, T.; Hilszczański, J.; Borowski, J.; Cieślak, R.; Mazur, A.; Miłkowski, M.; Szołtys, H. Faunistic review of Polish Platypodinae and Scolytinae (Coleoptera: Curculionidae). Pol. J. Èntomol. 2011, 80, 343–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byk, A.; Gazurek, T.; Borowski, Z.; Bidas, M.; Doktór, D.; Matusiak, A.; Minkina, Ł.; Plewa, R. New localities of Limarus maculatus (Sturm, 1800) (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Aphodiinae) in Poland. Entomol. News 2016, 35, 240–242. [Google Scholar]

- Germann, C.; Braunert, C.; Colonnelli, E.; Müller, G.; Müller, U. Beitrag zur Kenntnis der Rüsselkäfer-Fauna der Algarve, Portugal (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea). Entomol. Austriaca 2020, 27, 23–50. [Google Scholar]

- Alekseev, V.I. Checklist of Curculionoidea (Insecta: Coleoptera) of the Kaliningrad Region (Russia). Zool. Ecol. 2016, 26, 191–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riba, M.J. Inventario de los Scolytidae (Coleoptera) del NE España. Bol. Asoc. Esp. Entomol. 1996, 20, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, S.L.; Ochoa, P.R.; Bilbao, J.C.I.; Lafuente, A.G. Los Escolítidos de las Coníferas del País Vasco; Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu: Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain; Nagusia = Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco: Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain, 2007; p. 198. [Google Scholar]

- Ramilo, P.; Galante, E.; Micó, E. Intra-annual patterns of saproxylic beetle assemblages inhabiting mediterranean oak forests. J. Insect Conserv. 2017, 21, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Germann, C. Die Rüsselkäfer (Coleoptera, Curculionoidea) der Schweiz—Checkliste mit Verbreitungsangaben nach biogeografischen Regionen. Mitt. Schweiz. Entomol. Ges. 2010, 83, 41–118. [Google Scholar]

- Selmi, E. The Hylesininae of Turkey. Forestist 1987, 37, 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, M.A. The Coleoptera of the British Islands; L. Reeve and Co.: London, UK, 1891; p. 490. [Google Scholar]

- Watson, A.O.C. Coleoptera in the Aberdeen district. In The Entomologist´s Monthly Magazine; Second Series No. 299; Guerney & Jackson: London, UK, 1914; pp. 254–258. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Zarazaga, M.A.; Barrios, H.; Borovec, R.; Caldara, R.; Colonnelli, E.; Gültekin, L.; Hlaváč, P.; Korotyaev, B.; Lyal, C.H.C.; Machado, A.; et al. Cooperative Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera Curculionoidea. Version 2. Available online: http://weevil.info/content/palaearctic-catalogue (accessed on 4 October 2020).

- Baselga, A.; Novoa, F. Coleópteros del Parque Natural de las Fragas del Eume (Galicia, noroeste de la Península Ibérica), II: Scarabaeoidea, Buprestoidea, Byrrhoidea, Elateroidea, Bostrichoidea, Lymexyloidea, Cleroidea, Cucujoidea, Tenebrionoidea, Chrysomeloidea y Curculionoidea. Bol. Asoc. Esp. Entomol. 2004, 28, 121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Potter, K.J.B.; Kriticos, D.J.; Watt, M.S.; Leriche, A. The current and future potential distribution of Cytisus scoparius: A weed of pastoral systems, natural ecosystems and plantation forestry. Weed Res. 2009, 49, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, K.R.; Jennings, D.; Oberprieler, R.G. Annotated catalogue of Australian weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidea). Zootaxa 2014, 3896, 1–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simandl, J.; Kletečka, Z. Community of xylophagous beetles (Coleoptera) on Sarothamnus scoparius in Czechoslovakia. Acta Entomol. Bohemoslov. 1987, 84, 321–329. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischer, A. Přehled Brouků Fauny Československé Republiky; Moravské zemské museum: Brno, Czech Republic, 1930; p. 483. [Google Scholar]

- Stejskal, R. Závěrečná Zpráva k Provedenému Entomologickému Průzkumu Přírodní Památky Oleksovické Vřesoviště; Krajský úřad Jihomoravského kraje: Brno, Czech Republic, 2017; unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Jeniš, I. Inventarizační Průzkum (PR Údolí Oslavy a Chvojnice) z Oboru: Saproxyličtí Brouci; Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic: Praha, Czech Republic, 2013; unpublished work. [Google Scholar]

- Šrámek, V.; Neudertová-Hellebrandová, K. Mapy ohrožení smrkových porostů suchem jako nástroj identifikace rizikových oblastí: Odborné sdělení. Zprávy Lesn. Výzk. 2016, 61, 305–309. [Google Scholar]

- Huberty, A.F.; Denno, R.F. Plant Water Stress and Its Consequences for Herbivorous Insects: A New Synthesis. Ecology 2004, 85, 1383–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchi, N.; Ma, R.; Capretti, P.; Bonello, P. Systemic induction of traumatic resin ducts and resin flow in Austrian pine by wounding and inoculation with Sphaeropsis sapinea and Diplodia scrobiculata. Planta 2004, 221, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).