Genome-Wide Screening of Transposable Elements in the Whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), Revealed Insertions with Potential Insecticide Resistance Implications

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Supporting Data

2.2. TE Identification

2.3. TE Annotation

2.4. Estimation of TEs’ Age Distribution

2.5. TE Insertion Sites

3. Results

3.1. Annotation of TEs in the B. tabaci Genome

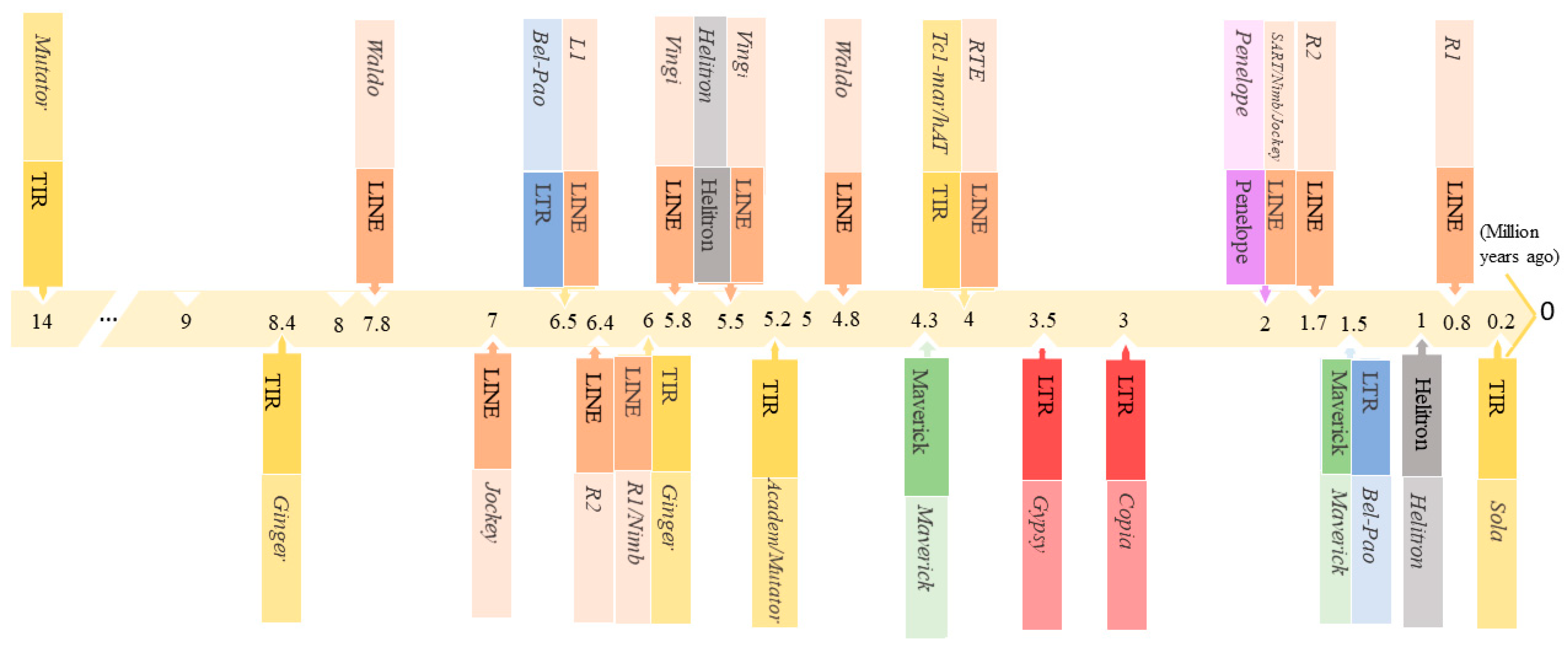

3.2. Estimation of TEs Age Distribution

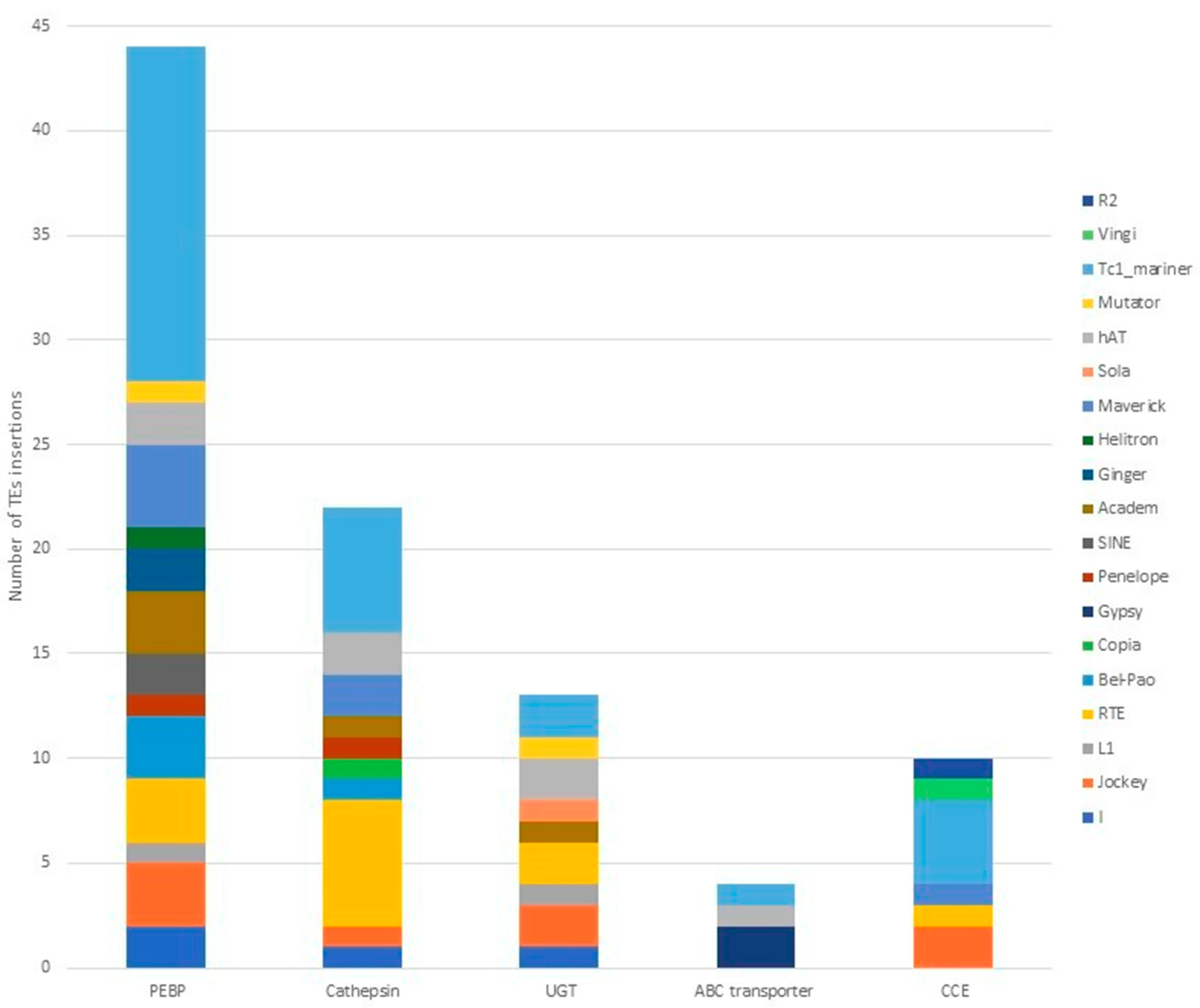

3.3. TE Insertions in and near Defensome Genes Involved in Insecticide Resistance

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jones, D.R. Plant viruses transmitted by whiteflies. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2003, 109, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, M.; Zou, H.; Laraib, T.; Rajpoot, N.A.; Khan, N.A.; Zaidi, A.A.; Kachelo, G.A.; Akhtar, M.W.; Hayat, S.; Al-Sadi, A.M.; et al. The impact of insecticides and plant extracts on the suppression of insect vector (Bemisia tabaci) of Mungbean yellow mosaic virus (MYMV). PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Rabou, S.; Simmons, A.M. Survey of reproductive host plants of Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in Egypt, including new host records. Entomol. News 2010, 121, 456–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas-Castillo, J.; Fiallo-Olivé, E.; Sánchez-Campos, S. Emerging virus diseases transmitted by whiteflies. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2011, 49, 219–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A.R.; Ghanim, M.; Roditakis, E.; Nauen, R.; Ishaaya, I. Insecticide resistance and its management in Bemisia tabaci species. J. Pest Sci. 2020, 93, 893–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Hasegawa, D.K.; Kaur, N.; Kliot, A.; Pinheiro, P.V.; Luan, J.; Stensmyr, M.C.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, W.; Sun, H.; et al. The draft genome of whitefly Bemisia tabaci MEAM1, a global crop pest, provides novel insights into virus transmission, host adaptation, and insecticide resistance. BMC Biol. 2016, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feschotte, C.; Pritham, E.J. DNA Transposons and the evolution of eukaryotic genomes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2007, 41, 331–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chénais, B.; Caruso, A.; Hiard, S.; Casse, N. The impact of transposable elements on eukaryotic genomes: From genome size increase to genetic adaptation to stressful environments. Gene 2012, 509, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, T.; Gundlach, H.; Spannagl, M.; Uauy, C.; Borrill, P.; Ramírez-González, R.H.; De Oliveira, R.; International Wheat Genome Sequencing Consortium; Mayer, K.F.X.; Paux, E.; et al. Impact of transposable elements on genome structure and evolution in bread wheat. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanera, R.; Vendrell-Mir, P.; Bardil, A.; Carpentier, M.C.; Panaud, O.; Casacuberta, J.M. Amplification dynamics of miniature inverted-repeat transposable elements and their impact on rice trait variability. Plant J. 2021, 107, 118–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akakpo, R.; Carpentier, M.; Hsing, Y.I.; Panaud, O. The impact of transposable elements on the structure, evolution and function of the rice genome. New Phytol. 2019, 226, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Casacuberta, E.; González, J. The impact of transposable elements in environmental adaptation. Mol. Ecol. 2013, 22, 1503–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drezen, J.-M.; Leobold, M.; Bezier, A.; Huguet, E.; Volkoff, A.-N.; Herniou, E.A. Endogenous viruses of parasitic wasps: Variations on a common theme. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2017, 25, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palazzo, A.; Marsano, R.M. Transposable elements: A jump toward the future of expression vectors. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 792–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daborn, P.J.; Yen, J.L.; Bogwitz, M.R.; Le Goff, G.; Feil, E.; Jeffers, S.; Tijet, N.; Perry, T.; Heckel, D.; Batterham, P.; et al. A single P450 allele associated with insecticide resistance in Drosophila. Science 2002, 297, 2253–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, J.M.; Good, R.T.; Appleton, B.; Sherrard, J.; Raymant, G.C.; Bogwitz, M.R.; Martin, J.; Daborn, P.J.; Goddard, M.E.; Batterham, P.; et al. Copy number variation and transposable elements feature in recent, ongoing adaptation at the Cyp6g1 locus. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1000998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Aminetzach, Y.T.; Macpherson, J.M.; Petrov, D.A. Pesticide resistance via transposition-mediated adaptive gene truncation in Drosophila. Science 2005, 309, 764–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salces-Ortiz, J.; Vargas-Chavez, C.; Guio, L.; Rech, G.E.; González, J. Transposable elements contribute to the genomic response to insecticides in Drosophila melanogaster. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2020, 375, 20190341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gahan, L.J.; Pauchet, Y.; Vogel, H.; Heckel, D.G. An ABC transporter mutation is correlated with insect resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6, e1001248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klai, K.; Chénais, B.; Zidi, M.; Djebbi, S.; Caruso, A.; Denis, F.; Confais, J.; Badawi, M.; Casse, N.; Khemakhem, M.M. Screening of Helicoverpa armigera mobilome revealed transposable element insertions in insecticide resistance genes. Insects 2020, 11, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, T.; Sabot, F.; Hua-Van, A.; Bennetzen, J.L.; Capy, P.; Chalhoub, B.; Flavell, A.; Leroy, P.; Morgante, M.; Panaud, O.; et al. A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2007, 8, 973–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makałowski, W.; Gotea, V.; Pande, A.; Makałowska, I. Transposable elements: Classification, identification, and their use as a tool for comparative genomics. In Evolutionary Genomics; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 177–207. [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan, D.J. Eukaryotic transposable elements and genome evolution. Trends Genet. 1989, 5, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Lu, J. Diversification of transposable elements in arthropods and its impact on genome evolution. Genes 2019, 10, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lerat, E. Identifying repeats and transposable elements in sequenced genomes: How to find your way through the dense forest of programs. Heredity 2010, 104, 520–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ou, S.; Su, W.; Liao, Y.; Chougule, K.; Agda, J.R.A.; Hellinga, A.J.; Lugo, C.S.B.; Elliott, T.A.; Ware, D.; Peterson, T.; et al. Benchmarking transposable element annotation methods for creation of a streamlined, comprehensive pipeline. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Quesneville, H.; Bergman, C.; Andrieu, O.; Autard, D.; Nouaud, D.; Ashburner, M.; Anxolabehere, D. Combined evidence annotation of transposable elements in genome sequences. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2005, 1, e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flutre, T.; Duprat, E.; Feuillet, C.; Quesneville, H. Considering transposable element diversification in de novo annotation approaches. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e16526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurka, J.; Kapitonov, V.V.; Pavlicek, A.; Klonowski, P.; Kohany, O.; Walichiewicz, J. Repbase update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2005, 110, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punta, M.; Coggill, P.C.; Eberhardt, R.; Mistry, J.; Tate, J.; Boursnell, C.; Pang, N.; Forslund, S.K.; Ceric, G.; Clements, J.; et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 40, D290–D301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoede, C.; Arnoux, S.; Moissette, M.; Chaumier, T.; Inizan, O.; Jamilloux, V.; Quesneville, H. PASTEC: An automatic transposable element classification tool. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e91929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jamilloux, V.; Daron, J.; Choulet, F.; Quesneville, H. De novo annotation of transposable elements: Tackling the fat genome issue. Proc. IEEE 2016, 105, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Wang, H.; Dvorak, J.; Bennetzen, J.; Mueller, H.G.; Dai, M.X. Package ‘TE’. 2018. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/ (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Quinlan, A.R.; Hall, I.M. BEDTools: A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quinlan, A.R. BEDTools: The swiss-army tool for genome feature analysis. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2014, 47, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cridland, J.M.; Thornton, K.; Long, A.D. Gene expression variation in Drosophila melanogaster due to rare transposable element insertion alleles of large effect. Genetics 2014, 199, 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goerner-Potvin, P.; Bourque, G. Computational tools to unmask transposable elements. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2018, 19, 688–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.-E.; Zhang, H.-H.; Xia, T.; Han, M.-J.; Shen, Y.-H.; Zhang, Z. BmTEdb: A collective database of transposable elements in the silkworm genome. Database 2013, 2013, bat055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filée, J.; Rouault, J.-D.; Harry, M.; Hua-Van, A. Mariner transposons are sailing in the genome of the blood-sucking bug Rhodnius prolixus. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, S.; Lorenzen, M.; Beeman, R.W.; Brown, S.J. Analysis of repetitive DNA distribution patterns in the Tribolium castaneum genome. Genome Biol. 2008, 9, R61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ben Amara, W.; Quesneville, H.; Khemakhem, M.M. A genomic survey of Mayetiola destructor mobilome provides new insights into the evolutionary history of transposable elements in the cecidomyiid midges. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0257996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langfield, K.L. Characterisation of neonicotinoid resistance in the cotton aphid, Aphis Gossypii from Australian cotton. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, Australia, April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, B.; Walko, R.; Hake, S. Mutator insertions in an intron of the maize knotted1 gene result in dominant suppressible mutations. Genetics 1994, 138, 1275–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Bogwitz, M.R.; McCart, C.; Andrianopoulos, A.; Ffrench-Constant, R.H.; Batterham, P.; Daborn, P.J. Cis-regulatory elements in the Accord retrotransposon result in tissue-specific expression of the Drosophila melanogaster insecticide resistance gene Cyp6g1. Genetics 2007, 175, 1071–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wessler, S.R.; Bureau, T.E.; White, S.E. LTR-retrotransposons and MITEs: Important players in the evolution of plant genomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1995, 5, 814–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casacuberta, J.M.; Santiago, N. Plant LTR-retrotransposons and MITEs: Control of transposition and impact on the evolution of plant genes and genomes. Gene 2003, 311, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohe, A.R.; Moriyama, E.N.; Lidholm, D.A.; Hartl, D.L. Horizontal transmission, vertical inactivation, and stochastic loss of mariner-like transposable elements. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1995, 12, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blumenstiel, J.P. Birth, school, work, death, and resurrection: The life stages and dynamics of transposable element proliferation. Genes 2019, 10, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Classes | Genome Covrage % | Order | Superfamily | Number of Copies | Number of Lineages | Number of FLC | % of TE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | 5.70 | LARD | 859 | 6 | 14 | 0.066 | |

| LINE | |||||||

| R2 | 2327 | 12 | 22 | 0.180 | |||

| R1 | 1015 | 23 | 50 | 0.079 | |||

| RTE | 14,232 | 34 | 211 | 1.101 | |||

| Jockey | 4909 | 87 | 202 | 0.380 | |||

| L1 | 170 | 1 | 2 | 0.013 | |||

| I | 931 | 13 | 27 | 0.072 | |||

| Vingi | 108 | 2 | 3 | 0.008 | |||

| Hope | 24 | 1 | 3 | 0.002 | |||

| Waldo | 197 | 3 | 5 | 0.015 | |||

| SART | 696 | 14 | 25 | 0.054 | |||

| Nimb | 952 | 7 | 11 | 0.074 | |||

| Loa | 3 | 62 | 5 | 0.000 | |||

| Unclassified | 17,698 | 64 | 179 | 1.369 | |||

| LTR | |||||||

| Copia | 3726 | 56 | 99 | 0.288 | |||

| Gypsy | 3797 | 64 | 147 | 0.294 | |||

| Bel-Pao | 143 | 64 | 101 | 0.011 | |||

| PLE | Penelope | 6993 | 27 | 52 | 0.541 | ||

| SINE | |||||||

| 5S | 385 | 2 | 3 | 0.030 | |||

| Unclassified | 2634 | 40 | 112 | 0.204 | |||

| TRIM | 11,424 | 117 | 319 | 0.884 | |||

| Class II | 16.55 | TIR | |||||

| Tc1-Mariner | 5038 | 52 | 407 | 0.390 | |||

| hAT | 5797 | 35 | 110 | 0.449 | |||

| Mutator | 1640 | 46 | 124 | 0.127 | |||

| Merlin | 23 | 1 | 3 | 0.002 | |||

| Transib | 52 | 2 | 3 | 0.004 | |||

| P | 135 | 7 | 10 | 0.010 | |||

| PiggyBac | 117 | 2 | 4 | 0.009 | |||

| PIF-Harbinger | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0.000 | |||

| Ginger | 292 | 5 | 27 | 0.023 | |||

| CACTA | 134 | 6 | 9 | 0.010 | |||

| Academ | 1097 | 9 | 42 | 0.085 | |||

| Sola | 93 | 2 | 9 | 0.007 | |||

| Unclassified | 106,644 | 566 | 5239 | 8.252 | |||

| Crypton | Crypton | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0.001 | ||

| Helitron | Helitron | 1723 | 21 | 95 | 0.133 | ||

| Maverick | Maverick | 6723 | 28 | 51 | 0.520 | ||

| MITE | 84,436 | 564 | 9393 | 6.533 | |||

| UnCategorized | 28.81 | 1,005,212 | 2825 | 10,478 | 77.779 | ||

| Total | 51.06 | 1,292,393 | 4872 | 27,599 | 100 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zidi, M.; Klai, K.; Confais, J.; Chénais, B.; Caruso, A.; Denis, F.; Khemakhem, M.M.; Casse, N. Genome-Wide Screening of Transposable Elements in the Whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), Revealed Insertions with Potential Insecticide Resistance Implications. Insects 2022, 13, 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13050396

Zidi M, Klai K, Confais J, Chénais B, Caruso A, Denis F, Khemakhem MM, Casse N. Genome-Wide Screening of Transposable Elements in the Whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), Revealed Insertions with Potential Insecticide Resistance Implications. Insects. 2022; 13(5):396. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13050396

Chicago/Turabian StyleZidi, Marwa, Khouloud Klai, Johann Confais, Benoît Chénais, Aurore Caruso, Françoise Denis, Maha Mezghani Khemakhem, and Nathalie Casse. 2022. "Genome-Wide Screening of Transposable Elements in the Whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), Revealed Insertions with Potential Insecticide Resistance Implications" Insects 13, no. 5: 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13050396

APA StyleZidi, M., Klai, K., Confais, J., Chénais, B., Caruso, A., Denis, F., Khemakhem, M. M., & Casse, N. (2022). Genome-Wide Screening of Transposable Elements in the Whitefly, Bemisia tabaci (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae), Revealed Insertions with Potential Insecticide Resistance Implications. Insects, 13(5), 396. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13050396