Insects in Art during an Age of Environmental Turmoil

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

“We stand guard over works of art, but species representing the work of aeons are stolen from under our noses”.—Aldo Leopold

2. Materials and Methods

- Collections of insect-themed art, published in books and exhibit catalogs (see references for partial list);

- Insect-themed gallery exhibits, accessible online;

- Articles written about artists using insects in their work, found online or from B.A.K.’s personal collection of tangible and digital files;

- Books about environmental art (see references for examples);

- Social media, by making calls for thematically relevant examples through Facebook and Twitter;

- Artists, by asking for examples of others’ art we had not already listed.

- Habitat destruction/change, including climate change;

- Invasive species;

- Pollution, including use of pesticides;

- Human population;

- Overharvesting by hunting;

- Decline of pollinators, including colony collapse disorder (despite human involvement not being clear with regard to colony collapse disorder);

- Intentional modification (e.g., bioengineering) or extermination of insects, with concern for insects or the environment in mind;

- Concern for environment/insects (when human involvement is not made explicitly clear).

3. Results

3.1. Categories of Destruction

3.2. Insect Orders

4. Discussion

4.1. Future of Insect Art Addressing Anthropogenic Environmental Distress

4.2. Qualifiers of Survey

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

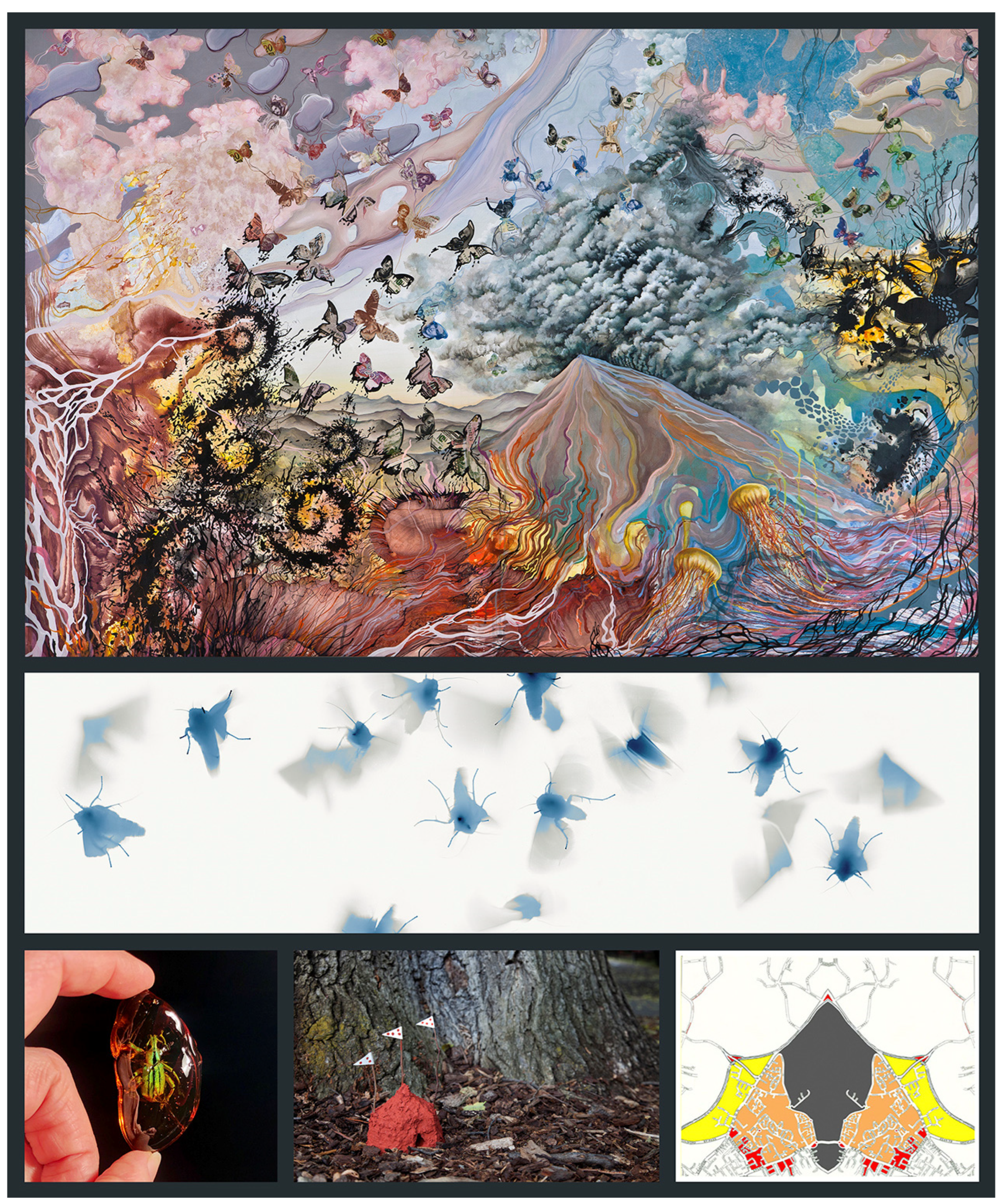

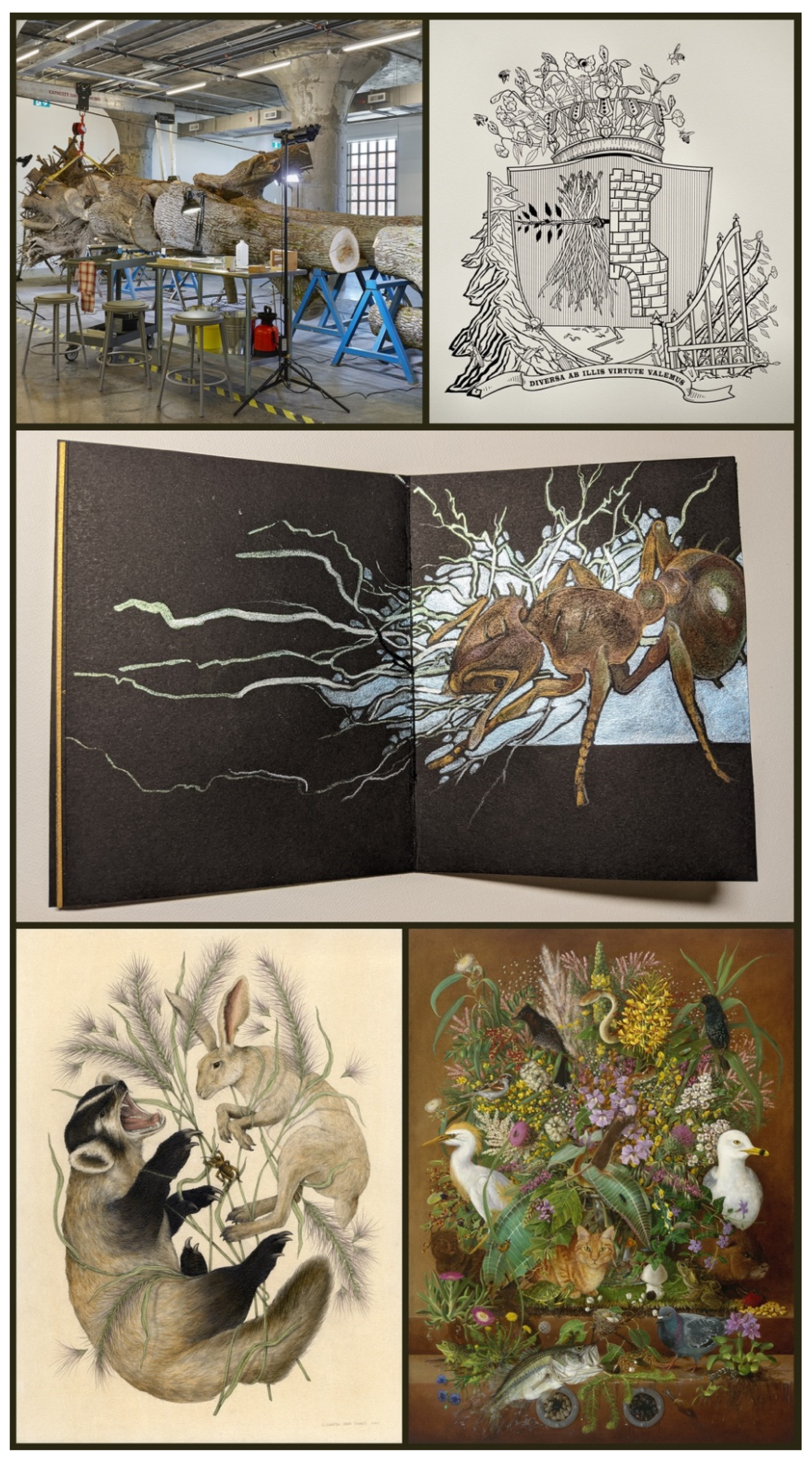

| Artist | Title of Work | Insect | Order | Category | Ref. | pc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trish Adams | Disordered Swarming (2013) | Western honey bee (Apis mellifera) | Hy | CCD | a | |

| Jasmine Ahumada | Spotted Lanternfly (2018) | Spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula) | He | Invasive species | b | |

| Erin Anfinson | Collapse 5 (2008) | A.mellifera | Hy | Decline of pollinators & CCD | [65] | |

| Jennifer Angus | In the Midnight Garden (2015) | Beetles, cicadas, grasshoppers, katydids, leaf insects | Mix: Co, He, Or, Ph | Habitat destruction; pollution; decline of pollinators | c | |

| Suzanne Anker | Twilight (2016) | Cockroach, beetles, fly, cicadas, bees (including A. mellifera), wasp nests, butterflies, moth, damselfly, grasshopper, stick insect | Mix: Bl, Co, Di, He, Hy, Le, Od, Or, Ph | CCD; modification | [78] | |

| Brandon Ballengée | Love Motel for Insects (2001–ongoing) | Insects attracted to ultraviolet lights | Mix: any insects | Concern for environment & insects | d, e | |

| The Beehive Design Collective | The True Cost of Coal (2010) | Cockroaches, beetles, flies, cicada, bees, paper wasps, moths (including peppered moth), butterfly, caddisfly larva, etc. (more may be hidden) | Mix: Bl, Co, Di, He, Hy, Le, Tr | Habitat destruction & climate change; pollution | f | |

| Michael Bianco | The Aristeaus Project (2015–ongoing) | A. mellifera | Hy | Decline of pollinators | g | |

| Matilde Boelhouwer | Insectology: Food for Buzz (2018) | Hoverflies (Syrphidae), bees, butterflies and moths (urban pollinators) | Di, Hy, Le | Decline of pollinators | h | |

| Kristian Brevik | (series; ongoing) | “All insects” listed | Mix | Habitat destruction & climate change; invasive species; pollution; decline of pollinators; extermination | i | |

| Anne Brodie | BEE BOX (2011) | A. mellifera | Hy | Decline of pollinators | j | |

| Wolfgang Buttress | The Hive (2016) | A. mellifera | Hy | Decline of pollinators | [79] | |

| Catherine Chalmers | Douglas Fir—Douglas Fir-Beetle (2022) | Douglas-fir beetle (Dendroctonus pseudotsugae) | Co | Habitat destruction & climate change | ||

| We Rule (2013) | Leaf-cutter ant (Atta sp.) | Hy | Habitat destruction | [80] | ||

| Executions (2003) | American cockroach (Periplaneta americana) | Bl | Extermination | [81] | ||

| Julie Alice Chappell | Insect sculptures (series; ongoing) | Real and fantastical “upcycled” insects | Mix: Co, Di, He, Hy, Le, Od | Concern for environment: waste | k | |

| Donna Conlon | Nature Improvement Project (2007) | Crane fly | Di | Modification | ||

| Kindra Crick | Lost II (2015) | A. mellifera | Hy | Pollution (pesticides); CCD | [65] | |

| Wendy DesChene, Jeff Schmuki | The Moth Project (2015) | Bees, moths | Hy, Le | Decline of pollinators & CCD | l | |

| Mark Dion | Harbingers of the Fifth Season (2014) | Invasives: beetles (Agrilus planipennis, Anoplophora glabripennis, Scolytus multistriatus), woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae), woodwasp (Sirex noctilio), moth (Lymantria dispar); Extinct: blue stag beetle (Platycerus caraboides), levuana moth (Levuana iridescens), Xerces blue (Glaucopsyche xerces), Rocky Mountain locust (Melanoplus spretus) | Mix: Co, He, Hy, Le; Or | Climate change; invasive species | m | |

| Elsabe Dixon | Spotted Lanternfly Zones of Syncopation (2019) | L. delicatula | He | Invasive species | n, [82] | |

| Jim Frazer | Glyph Documents (e.g., Glyph 32; 2017) | Bark beetles: tracks | Co | Climate change | o | |

| Victoria Fuller | In My Back Yard (2014) | Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica), A. mellifera | Co, Hy | Habitat destruction & climate change; invasive species; pollution; overpopulation | p | |

| Spelling Bee (2014) | A. mellifera | Hy | Modification | p | ||

| Tera Galanti | Hope and Futility (2006) | Silkworm moth (Bombyx mori) | Hy | Modification | q | |

| Erika Harrsch | Melt (2012) | Butterflies | Le | Habitat destruction & climate change; concern for environment: humans disconnected from nature | r | |

| Sarah Hatton | Circle 1–8 (2013–2015) | A. mellifera | Hy | Habitat destruction (monoculture); pollution (pesticides) | s | |

| Susan Hauri-Downing | Threatened, Rare—Extant (2018) | Thynnine wasp (Zaspilothynnus gilesi) | Hy | Habitat destruction; invasive species (weeds); decline of pollinators | t | |

| Cornelia Hesse-Honegger | Heavily deformed scorpionfly…, etc. (series; 1987–2004) | True bugs (Heteroptera, Auchenorrhyncha), scorpionfly | He, Mc | Pollution (radioactive, Agent Orange) | [83,84] | |

| Chelsea Herman, Angela Mele | RECALL: e.T51269349A55309428 | Rocky mountain locust (Melanoplus spretus) | Or | Habitat destruction; extermination (extinction) | u | |

| Anthony Heywood | Species 4945 | Bombus sp. | Hy | Concern for insects: human threat | [85] | |

| Asuka Hishiki | Arch of Monarchs (2013) | Danaus plexippus | Le | Habitat destruction & climate change | [86] | |

| Red list wallpaper KYOTO 2015 (2021) | 18 spp. of threatened beetles (12), fly, bee, butterflies (3), dragonfly; listed here: https://www.pref.kyoto.jp/kankyo/rdb/bio/index.html | Mix: Co, Di, Hy, Le, Od | Habitat destruction & climate change; overhunting | v | ||

| Jessa Huebing-Reitinger | Project InSECT (2003–ongoing) | Mix | Concern for environment | w | ||

| Marlène Huissoud | Please stand by (2021) | Insect pollinators (referenced: solitary bees, wasps, butterflies) | Hy, Le | Concern for insects & environment | x | |

| Leif Erik Johansen | Uprising (2015) | A. mellifera | Hy | Climate change | y | |

| Chris Jordan, Helena S. Eitel | Roundup (2015) | A. mellifera | Hy | Pollution (pesticides); decline of pollinators | [80] | |

| Jenny Kendler | Amber Archive (2020) | 26 spp. of beetles (9), cicada (1), bees (3), wasp (1), ant (1), butterflies (9), moths (2) embedded to appear like amber inclusions | Mix: Co, He, Hy, Le | Habitat change & climate change | z | |

| Milkweed Dispersal Balloons (2014–) | Butterflies (including D. plexippus) | Le | Pollution (pesticides); decline of pollinators | z, [87] | ||

| Jane Kim | Migrating Mural (2010–ongoing) | Butterflies (including G. xerces, D. plexippus) | Le | Concern for insects & environment | aa | |

| Isabella Kirkland | Ascendant (2000) | Beetles (A. glabripennis, P. japonica, Anthonomus grandis grandis, Metriona elatior), bees (A. mellifera, A. mellifera scutellata), ants (Solenopis invicta, Pheidole megacephala, Iridomyrmex humilis), butterfly (Vanessa cardui), moth (L. dispar), mantis (Tenodera aridifolia sinensis) | Mix: Co, Hy, Le, Ma | Invasive species | [88,89] | |

| Trade (2001) | Beetles (Chalcosoma caucasus, Plusiotis beyeri, P. resplendens, P. chrysargyrea, Euchroma gigantea, Lucanus cervus, Rosalia alpina, Carabus auratus, Chrysina aurigans), butterflies (Ornithoptera alexandrae, Papilio androgeus, P. homerus, P. chikae chikae, Agrias claudina lugens, Troides priamus), moths (Argema mittrei, Chrysiridia riphearia, Xanthopan morgani praedicta), mantis (Hymenopus coronatus) | Co, Le, Ma | Habitat destruction; concern for insects: exploitation of animal products | [88,89] | ||

| Barrett Klein | Layers (1993) | Scarab | Co | Concern for insects | ||

| Karen Anne Klein | Invaders (series; 2022) | P. japonica, brown marmorated stink bug (Halyomorpha halys), electric ant (Wasmannia auropunctata), crazy ant (Nylanderia fulva), ghost ant (Tapinoma melanocephalum), L. dispar dispar | Mix: Co, He, Hy, Le | Invasive species | ||

| Beate Kratt | Traces (2015) | A. mellifera | Hy | Concern for insects (bees) | [65] | |

| Peter Kuper | Ruins (2015) | D. plexippus | Le | Habitat destruction & climate change | [90] | |

| Katja Loher | Bee Manifesto (2015) | A. mellifera | Hy | Pollution (pesticides); decline of pollinators & CCD | bb | |

| Mike MacDonald | Touched by the Tears of a Butterfly (2001) | Butterflies | Le | Habitat change; concern for environment: humans disconnected from nature | [91] | |

| Ruth Marsh | Cyberhive (2019) | Bees | Hy | Habitat destruction & climate change; pollution; decline of pollinators; modification | cc | |

| Louis Masai | The Art of Beeing (2016) | Bees (A. mellifera, Anthophila spp.) | Hy | Habitat destruction & climate change; pollution; decline of pollinators & CCD; modification | dd | |

| Katharina Mischer, Thomas Traxler (mischer’traxler studio) | Curiosity Cloud (2015) | 25 spp. of extinct, highly endangered, very common, & newly discovered insects | Mix: Co, Di, Ep, He, Hy, Le, Ne, Od, Or | Concern for insects (biodiversity loss) | ee | |

| Tim Musso | Rite of the Dendroctonus jeffreyi (2012) | Jeffrey pine beetle (Dendroctonus jeffreyi) | Co | Habitat change & climate change; invasive species | ||

| Carim Nahaboo | Illustrations | e.g., hornet robber fly (Asilus crabroniformis), new forest cicada (Cicadetta montana), Chilean bumblebee (Bombus dahlbomii), large garden bumblebee (Bombus ruderatus) | Di, He, Hy | Habitat destruction; invasive species; pollution | ||

| Harry Nankin | Moth Liturgy films (2011–2021) & prints (2016) | Bogong moth (Agrotis infusa) | Le | Habitat loss & climate change; pollution | ff | |

| Bekka Ord | Bye Bye Biodiversity (2018) | Larch beetle (Dendroctonus simplex), D. plexippus | Co, Le | Climate change | gg | |

| Richard Pell et al. | Center for PostNatural History | Mosquito (Aedes aegypti), screw-worm (Cochliomyia hominivorax) | Di | Modification | [92] | |

| Perdita Phillips | Termite Embassy (2015) | Termites | Bl | Climate change | hh | |

| Between a shipwreck and an anthill (2018) | Termite mound | Bl | Habitat loss; pollution | hh | ||

| David Prochaska | Point Arrow to Dot (series; 2003–2006) | Earwig, mosquito, cicada, mantid, flea (and spider) | Mix: De, Di, He, Ma, Si | Pollution (pesticides) | [93] | |

| Garnett Puett | Untitled (1985) | A. mellifera | Hy | Concern for environment: humans disconnected from nature | [94] | |

| Reinhard Reitzenstein | Memory Vessel (1994) | A. mellifera: beeswax | Hy | Invasive species | [95] | |

| Pedro Reyes | The Grass-whopper (2013) | Grasshopper, cricket | Or | Climate change | ii | |

| Alexis Rockman | The Farm (2000) | Fruit fly (Drosophila melanogaster), peppered moth (Biston betularia) | Di, Le | Pollution; modification | [88] | |

| Bärbel Rothhaar | Beekeeper Portrait 1 (2004) | A. mellifera | Hy | Climate change; pollution; decline of pollinators | jj, [96] | |

| Christy Rupp | Glyphosate… and Cotton Boll Weevil (1999) | Cotton boll weevil (Anthonomus grandis) | Co | Pollution (pesticides); modification | kk, [86] | |

| Kimberly Shaffer | Beetle Service, Black Beetle, etc. (series; 2016) | Beetles, cicadas, ants (Pogonomyrmex californicus) | Co, He, Hy | Concern for environment (partial proceeds to conservation) | ll | |

| Jaune Quick-to-See Smith | Carousel (2004) | Beetle, butterfly caterpillar | Co, Le | Habitat destruction; concern for environment: humans disconnected from nature | [88] | |

| Angela Thames | Surrey Butterflies (2007–2008) | Butterflies | Le | Habitat destruction | [85], mm | |

| Peter von Tiesenhausen | A. mellifera: traces on hives | Hy | Concern for environment | [97] | ||

| Harriette Tsosie | The Dead Bee Scrolls Triptych (2015) | A. mellifera | Hy | Pollution (pesticides); decline of pollinators & CCD | [65] | |

| Cecilia Vicuña | Insectageddon (2021, collective performance) | All insects, with focus on pollinators | Mix any insects | Habitat destruction; pollution (pesticides); concern for insects & environment | nn | |

| Andy Warhol | Endangered Species (1983) | Callipe silverspot butterfly (Speyeria callippe callippe) | Le | Concern for environment | [98] | |

| Liao Wenfeng | From Here to There (2010) | Ant | Hy | Habitat destruction; concern: humans disconnected from nature | [99] | |

| Matt Willey | The Good of the Hive (2015–) | A. mellifera | Hy | Decline of pollinators & CCD | oo, [100] | |

| Vera Ming Wong | In Flight (2013) | Pollinators and other insects | Mix: Co, Di, He, Hy, Le, Od | Concern for insects | pp | |

| Suze Woolf | Bark Beetle Books— Vols. I-XXXX(ongoing) | Bark beetles | Co | Habitat destruction & climate crisis | ||

| Pinar Yoldas | Microplastics and plastisphere insects (2014) | pelagic “plastisphere” insects | Mix? | Pollution (plastic); modification | rr, [101] | |

| Elizabeth Jean Younce | The Withering(series; 2021) | Scarab (Paracotalpa granicollis), Sonoran bumblebee (Bombus sonorus), Africanized honey bee (A. mellifera), Bay checkerspot butterfly (Euphydryas editha bayensis), Jerusalem cricket (Stenopelmatus monahansensis), stonefly (Acroneuria abnormis) | Mix: Co, Hy, Le, Or, Pl | Habitat loss; invasive species (including Malta star-thistle, cheatgrass, buffelgrass, zebra mussel); pollution & pesticides | ss | |

| Marina Zurkow | Heraldic Crests for Invasive Species (series; 2011) | Lizard beetle (Acropteroxys gracilis), stem-boring weevil (Mecinus janthinus); Japanese knotweed psyllid (Aphalara itadori) | Co, He | Invasive species | tt | |

| Zurkow, Chaudhuri, Kellhammer, Ertl | Dear Climate (series; 2014–ongoing) | Cockroach, beetle grubs, giant water bugs (labeled as beetles), bumblebees, katydid | Mix: Bl, Co, He, Hy, Or | Habitat change & climate change | [102] |

References

- Riley, J.C. Estimates of Regional and Global Life Expectancy, 1800–2001. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2005, 31, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolt, J.; van Zaden, J. Maddison Style Estimates of the Evolution of the World Economy. Available online: https://www.rug.nl/ggdc/historicaldevelopment/maddison/releases/maddison-project-database-2020 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Regional Aggregation Using 2011 PPP and $1.9/Day Poverty Line. Available online: http://iresearch.worldbank.org/povcalNet/povDuplicateWB.aspx (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- International Database. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/#/country?COUNTRY_YEAR=2022&COUNTRY_YR_ANIM=2022 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Fardila, D.; Kelly, L.T.; Moore, J.L.; McCarthy, M.A. A Systematic Review Reveals Changes in Where and How We Have Studied Habitat Loss and Fragmentation over 20 Years. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 212, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal-Ornelas, R.; Lockwood, J. The “Known Unknowns” of Invasive Species Impact Measurement. Biol. Invasions 2020, 22, 1513–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, T.S.; Glen, A.S.; Nimmo, D.G.; Ritchie, E.G.; Dickman, C.R. Invasive Predators and Global Biodiversity Loss. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 11261–11265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bradshaw, C.J.; Leroy, B.; Bellard, C.; Roiz, D.; Albert, C.; Fournier, A.; Barbet-Massin, M.; Salles, J.-M.; Simard, F.; Courchamp, F. Massive yet Grossly Underestimated Global Costs of Invasive Insects. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahon, S.M.; Harrison, S.P.; Armbruster, W.S.; Bartlein, P.J.; Beale, C.M.; Edwards, M.E.; Kattge, J.; Midgley, G.; Morin, X.; Prentice, I.C. Improving Assessment and Modelling of Climate Change Impacts on Global Terrestrial Biodiversity. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2011, 26, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffers, B.R.; De Meester, L.; Bridge, T.C.; Hoffmann, A.A.; Pandolfi, J.M.; Corlett, R.T.; Butchart, S.H.; Pearce-Kelly, P.; Kovacs, K.M.; Dudgeon, D. The Broad Footprint of Climate Change from Genes to Biomes to People. Science 2016, 354, aaf7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecl, G.T.; Araújo, M.B.; Bell, J.D.; Blanchard, J.; Bonebrake, T.C.; Chen, I.-C.; Clark, T.D.; Colwell, R.K.; Danielsen, F.; Evengård, B. Biodiversity Redistribution under Climate Change: Impacts on Ecosystems and Human Well-Being. Science 2017, 355, eaai9214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbold, T.; Hudson, L.N.; Hill, S.L.; Contu, S.; Lysenko, I.; Senior, R.A.; Börger, L.; Bennett, D.J.; Choimes, A.; Collen, B. Global Effects of Land Use on Local Terrestrial Biodiversity. Nature 2015, 520, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dirzo, R.; Young, H.S.; Galetti, M.; Ceballos, G.; Isaac, N.J.; Collen, B. Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 2014, 345, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Dirzo, R. Biological Annihilation via the Ongoing Sixth Mass Extinction Signaled by Vertebrate Population Losses and Declines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E6089–E6096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pimm, S.L.; Jenkins, C.N.; Abell, R.; Brooks, T.M.; Gittleman, J.L.; Joppa, L.N.; Raven, P.H.; Roberts, C.M.; Sexton, J.O. The Biodiversity of Species and Their Rates of Extinction, Distribution, and Protection. Science 2014, 344, 1246752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceballos, G.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Raven, P.H. Vertebrates on the Brink as Indicators of Biological Annihilation and the Sixth Mass Extinction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 13596–13602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Pratchett, M.S.; Hoey, A.S.; Wilson, S.K.; Messmer, V.; Graham, N.A. Changes in Biodiversity and Functioning of Reef Fish Assemblages Following Coral Bleaching and Coral Loss. Diversity 2011, 3, 424–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brandl, S.J.; Johansen, J.L.; Casey, J.M.; Tornabene, L.; Morais, R.A.; Burt, J.A. Extreme Environmental Conditions Reduce Coral Reef Fish Biodiversity and Productivity. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, K.V.; Dokter, A.M.; Blancher, P.J.; Sauer, J.R.; Smith, A.C.; Smith, P.A.; Stanton, J.C.; Panjabi, A.; Helft, L.; Parr, M. Decline of the North American Avifauna. Science 2019, 366, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-del-Pliego, P.; Freckleton, R.P.; Edwards, D.P.; Koo, M.S.; Scheffers, B.R.; Pyron, R.A.; Jetz, W. Phylogenetic and Trait-Based Prediction of Extinction Risk for Data-Deficient Amphibians. Curr. Biol. 2019, 29, 1557–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallmann, C.A.; Sorg, M.; Jongejans, E.; Siepel, H.; Hofland, N.; Schwan, H.; Stenmans, W.; Müller, A.; Sumser, H.; Hörren, T. More than 75 Percent Decline over 27 Years in Total Flying Insect Biomass in Protected Areas. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forister, M.L.; Pelton, E.M.; Black, S.H. Declines in Insect Abundance and Diversity: We Know Enough to Act Now. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2019, 1, e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janzen, D.H.; Hallwachs, W. Perspective: Where Might Be Many Tropical Insects? Biol. Conserv. 2019, 233, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seibold, S.; Gossner, M.M.; Simons, N.K.; Blüthgen, N.; Müller, J.; Ambarlı, D.; Ammer, C.; Bauhus, J.; Fischer, M.; Habel, J.C.; et al. Arthropod Decline in Grasslands and Forests Is Associated with Landscape-Level Drivers. Nature 2019, 574, 671–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, B. The Insect Apocalypse Is Here. N. Y. Times Mag. 2018, 41. Available online: http://nategabriel.com/egblog/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/5-1_The-Insect-Apocalypse-Is-Here-The-New-York-Times.pdf (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Engel, M. An Insect Apocalypse Will Be Our Apocalypse. Wall Str. J. 2019, 29, R967–R971. [Google Scholar]

- Working Groups: WGI—The Physical Science Basis, WGII—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, WGIII—Mitigation of Climate Change IPCC. In AR6 Synthesis Report: Climate Chage 2022; World Meterological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Anderegg, W.R.; Prall, J.W.; Harold, J.; Schneider, S.H. Expert Credibility in Climate Change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 12107–12109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cook, J.; Oreskes, N.; Doran, P.T.; Anderegg, W.R.; Verheggen, B.; Maibach, E.W.; Carlton, J.S.; Lewandowsky, S.; Skuce, A.G.; Green, S.A. Consensus on Consensus: A Synthesis of Consensus Estimates on Human-Caused Global Warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 2016, 11, 048002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, B.J.; Duffy, J.E.; Gonzalez, A.; Hooper, D.U.; Perrings, C.; Venail, P.; Narwani, A.; Mace, G.M.; Tilman, D.; Wardle, D.A. Biodiversity Loss and Its Impact on Humanity. Nature 2012, 486, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.O. The Future of Life; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Almond, R.E.; Grooten, M.; Peterson, T. Living Planet Report 2020-Bending the Curve of Biodiversity Loss; World Wildlife Fund: Gland, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 2-940529-99-X. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowsky, S. Climate Change Disinformation and How to Combat It. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A.; Maibach, E.; Rosenthal, S.; Kotcher, J.; Bergquist, P.; Ballew, M.T.; Goldberg, M.; Gustafson, A. Climate Change in the American Mind: November 2019. 2020. Available online: https://psyarxiv.com/z3wtx/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- DERFA (Department for Environment, Food, and Rural Affairs). Survey of Public Attitudes and Behaviors towards the Environment; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2009.

- Sampei, Y.; Aoyagi-Usui, M. Mass-Media Coverage, Its Influence on Public Awareness of Climate-Change Issues, and Implications for Japan’s National Campaign to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2009, 19, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, E.U. Experience-Based and Description-Based Perceptions of Long-Term Risk: Why Global Warming Does Not Scare Us (Yet). Clim. Chang. 2006, 77, 103–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Leviston, Z.; Hurlstone, M.; Lawrence, C.; Walker, I. Emotions Predict Policy Support: Why It Matters How People Feel about Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2018, 50, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brook, L. Evaluating the Emotional Impact of Environmental Artworks Using Q Methodology. Athens J. Humanit. Arts 2021, 8, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmis, J. Visual Climate Change Art 2005–2015: Discourse and Practice. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Chang. 2016, 7, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, S.C.; Dilling, L. Making Climate Hot. Environ. Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 2004, 46, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, G.; Stead, M.; Webb, J. Fear Appeals in Social Marketing: Strategic and Ethical Reasons for Concern. Psychol. Mark. 2004, 21, 961–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’neill, S.; Nicholson-Cole, S. “Fear Won’t Do It” Promoting Positive Engagement with Climate Change through Visual and Iconic Representations. Sci. Commun. 2009, 30, 355–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bissing-Olson, M.J.; Fielding, K.S.; Iyer, A. Experiences of Pride, Not Guilt, Predict pro-Environmental Behavior When pro-Environmental Descriptive Norms Are More Positive. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harth, N.S.; Leach, C.W.; Kessler, T. Guilt, Anger, and Pride about in-Group Environmental Behaviour: Different Emotions Predict Distinct Intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 34, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, L.K.; Swim, J.K.; Keller, A.; Klöckner, C.A. “Pollution Pods”: The Merging of Art and Psychology to Engage the Public in Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2019, 59, 101992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosen, L.J.; Klöckner, C.A.; Swim, J.K. Visual Art as a Way to Communicate Climate Change: A Psychological Perspective on Climate Change–Related Art. World Art 2018, 8, 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, C.; Chandler, L. “At the Water’s Edge”: Community Voices on Climate Change. Local Environ. 2010, 15, 637–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, M.; Chandler, L.; Baldwin, C. Re-Imagining the Environment: Using an Environmental Art Festival to Encourage pro-Environmental Behaviour and a Sense of Place. Local Environ. 2016, 21, 310–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, L.K.; Klöckner, C.A. Does Activist Art Have the Capacity to Raise Awareness in Audiences?—A Study on Climate Change Art at the ArtCOP21 Event in Paris. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 2021, 15, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, D.J.; Reid, N.; Ballard, G. Communicating Ecology through Art: What Scientists Think. Ecol. Soc. 2012, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, J. The Infested Mind: Why Humans Fear, Loathe, and Love Insects; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; ISBN 0-19-937493-7. [Google Scholar]

- Rooney, E.A. Bugs in Contemporary Art: Inspired by Insects, 1st ed.; Schiffer: Atglen, PA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Smiles, S. Insects in the History of Western Art. Antenna 2005, 29, 118–120. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, B.A. Standing on the Shoulders of Wee Giants. In ECLOSION: A Juried Group Exhibition of Insect-Inspired Art; Art.Science.Gallery: Austin, TX, USA, 2013; Available online: https://issuu.com/artsciencegallery/docs/eclosioncatalogue (accessed on 5 May 2022).

- Klein, B.A. Insects in Art. In Encyclopedia of Human-Animal Relationships: A Global Exploration of Our Connections with Animals; Bekoff, M., Ed.; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Brosius, T.R.; Higley, L.; Johnson, L. Promoting the Conservation of the Salt Creek Tiger Beetle Using the Visual Arts. Am. Entomol. 2014, 60, 39–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klein, B.A. Wax, Wings, and Swarms: Insects and Their Products as Art Media. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2021, 67. Available online: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-ento-020821-060803 (accessed on 5 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Hubbell, S. Bugs. New Yorker, 28 December 1987; 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, B.A. Par for the Palette: Insects and Arachnids as Art Media. In Insects in Oral Literature and Traditions; Motte-Florac, E., Thomas, J.M.C., Eds.; Peeters: Paris, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, B.A.; Brosius, T.R. Insects in Art: A Planet in Peril and the Insect Muse. In A Cultural History of Insects in the Modern Age; Kritsky, G., Peterson, R., Eds.; Bloomsbury: London, UK; Volume 6, in press.

- Poortinga, W.; Pidgeon, N.F. Exploring the Dimensionality of Trust in Risk Regulation. Risk Anal. Int. J. 2003, 23, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawken, P. Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-0-14-313044-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, H. The Buzz Stops Here; Art.Science.Gallery: Austin, TX, USA, 2014; Available online: https://issuu.com/artsciencegallery/docs/buzzcatalogue_20150411_1608 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Forbes, A.A.; Bagley, R.K.; Beer, M.A.; Hippee, A.C.; Widmayer, H.A. Quantifying the Unquantifiable: Why Hymenoptera, Not Coleoptera, Is the Most Speciose Animal Order. BMC Ecol. 2018, 18, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prendergast, K.S.; Garcia, J.E.; Howard, S.R.; Ren, Z.-X.; McFarlane, S.J.; Dyer, A.G. Bee Representations in Human Art and Culture through the Ages. Art Percept. 2021, 1, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kritsky, G.; Smith, J.J. Insect Biodiversity in Culture and Art: Science and Society. Insect Biodivers. Sci. Soc. 2018, 2, 869–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.A. Encaustics: Repurposing the Architecture of Insects. In The Buzz Stops Here; Art.Science.Gallery: Austin, TX, USA, 2015; Available online: https://issuu.com/artsciencegallery/docs/buzzcatalogue_20150411_1608 (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Stork, N.E. How Many Species of Insects and Other Terrestrial Arthropods Are There on Earth? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hogue, C.L. Cultural Entomology. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 1987, 32, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.A. The Curious Connection between Insects and Dreams. Insects 2011, 3, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Berenbaum, M.R.; Simpson, S. Bugs in the System: Insects and Their Impact on Human Affairs. Nature 1995, 374, 842. [Google Scholar]

- Clausen, L.W. Insect Fact and Folklore; Allen Press: Lawrence, KS, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Duffus, N.E.; Christie, C.R.; Morimoto, J. Insect Cultural Services: How Insects Have Changed Our Lives and How Can We Do Better for Them. Insects 2021, 12, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniels, F.M. Why Art? Nelson-Hall: Chicago, IL, USA, 1978; pp. 201–203. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. Art & Ecology Now; Thames & Hudson Inc: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Sichel, B. Nectar: War Upon the Bees; Pratt Manhattan Gallery: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fessenden, M. This Sculpture Is Controlled by Live Honeybees. Smithson. Mag. 2016. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/sculpture-controlled-live-honeybees-180960006/ (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Matilsky, B.C. Endangered Species: Artists on the Front Line of Biodiversity; Whatcom Museum: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; ISBN 978-0-692-08331-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, C. American Cockroach; Aperture Foundation, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, M. Penn State Invites Community to Help Make Art from Beautiful, Destructive Lanternflies. Available online: https://www.mcall.com/entertainment/mc-ent-art-from-lanternflies-20190724-p5sfwerqtje5vkkviqulohjopq-story.html (accessed on 30 March 2022).

- Hesse-Honegger, C.; Wallimann, P. Malformation of True Bug (Heteroptera): A Phenotype Field Study on the Possible Influence of Artificial Low-Level Radioactivity. Chem. Biodivers. 2008, 5, 499–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Körblein, A.; Hesse-Honegger, C. Morphological Abnormalities in True Bugs (Heteroptera) near Swiss Nuclear Power Stations. Chem. Biodivers. 2018, 15, e1800099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smithers, P. Insects and Art: A Contemporary and Historical Perspective; Peninsula Arts, University of Plymouth: Plymouth, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lantzas, J. Notched Bodies: Insects in Contemporary Art; The Arsenal Gallery: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Aloi, G. Milkweed Dispersal Balloons. Antennae J. Nat. Vis. Cult. 2016, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Art in Action: Nature, Creativity and Our Collective Future; Earth Aware Editions; Natural World Museum: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2007.

- Kirkland, I. TAXA. Antennae J. Nat. Vis. Cult. 2019, 180–209. [Google Scholar]

- Kuper, P. Ruins; SelfMadeHero: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-1-906838-98-0. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, M. Healing Garden. In Art Nature Dialogues: Interviews with Environmental Artists; Grande, J.K., Ed.; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Pell, R.W.; Kutil, E.; Turpin, E. PostNatural Histories. In Art in the Anthropocene: Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies; Davis, H., Turpin, E., Eds.; Open Humanities Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Watts, P. Bug-Eyed: Art, Culture, Insects; Turtle Bay Exploratorium Park: Redding, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cohrs, T. Garnett Puett’s Apisculpture: Uniting the Bee to the Task of Art. Arts Mag. 1985, 60, 122–123. [Google Scholar]

- Reitzenstein, R. Earth in Context. In Art Nature Dialogues: Interviews with Environmental Artists; Grande, J.K., Ed.; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brückner, D.; Bärbel, R. Honigbienen in Kunst Und Wissenschaft (Honeybees in Art and Science); Haus der Wissenschaft: Bremen, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- von Tiesenhausen, P. Ship of Life. In Art Nature Dialogues: Interviews with Environmental Artists; Grande, J.K., Ed.; State University of New York Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Warhol Foundation. Available online: https://warholfoundation.org/ (accessed on 28 March 2022).

- Hoenes-Stiftung; Dathe, S. (Eds.) Jäger Und Gejagte (Hunters and Hunted); Biberacher Verlagsdruckerei: Stuttgart, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham, T. Downtown the Good of the Hive, the Good of the Bees, and the Good of Us All. Bee Cult. Mag. Am. Beekeep. 2008.

- Davis, H.; Turpin, E. (Eds.) Yoldas, Pinar Ecosystems of Excess. In Anthropocene: Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies; Open Humanities Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, U.; Ertl, F.; Kellhammer, O.; Zurkow, M. Dear Climate. In Anthropocene: Encounters Among Aesthetics, Politics, Environments and Epistemologies; Open Humanities Press: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Art | Art with ≤ 3 Categories | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category of Environmental Distress | # | % | # | % |

| Habitat/climate change | 34 | 47 | 29 | 43 |

| Invasive species | 13 | 18 | 11 | 16 |

| Pollution | 23 | 32 | 18 | 26 |

| Human overpopulation | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Overharvesting by hunting | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Decline of pollinators/CCD | 19 | 26 | 15 | 22 |

| Intentional modification/extermination | 13 | 18 | 9 | 13 |

| Concern | 14 | 19 | 14 | 21 |

| Art | Art with ≤ 3 Orders | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insect Order | # | % | # | % |

| Hymenoptera | 42 | 62 | 32 | 56 |

| Lepidoptera | 24 | 35 | 16 | 28 |

| Coleoptera | 24 | 35 | 13 | 23 |

| Hemiptera | 17 | 25 | 6 | 11 |

| Diptera | 12 | 18 | 6 | 11 |

| Orthoptera | 8 | 12 | 2 | 4 |

| Blattodea | 5 | 7 | 2 | 4 |

| Odonata | 5 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Klein, B.A.; Brosius, T. Insects in Art during an Age of Environmental Turmoil. Insects 2022, 13, 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13050448

Klein BA, Brosius T. Insects in Art during an Age of Environmental Turmoil. Insects. 2022; 13(5):448. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13050448

Chicago/Turabian StyleKlein, Barrett Anthony, and Tierney Brosius. 2022. "Insects in Art during an Age of Environmental Turmoil" Insects 13, no. 5: 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13050448

APA StyleKlein, B. A., & Brosius, T. (2022). Insects in Art during an Age of Environmental Turmoil. Insects, 13(5), 448. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13050448