Simple Summary

This review reports the main developments in the biological control of spotted-wing drosophila (SWD), Drosophila suzukii, using parasitoids, predatory insects, and entomopathogens. We reviewed research conducted worldwide on the biological control of spotted-wing drosophila over the past decade (2012–2023). We examined 184 publications to see how many focused on each control agent, what methods they used, and where the research was carried out. Most research focused on tiny wasps that attack the pest, the most common being Trichopria drosophilae and Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae, with increasing interest in others like Leptopilina japonica and Ganaspis kimorum. Fifty-five publications examined entomopathogenic agents, while only 15 studied the predatory effects on SWD. Most publications were conducted in controlled environments like labs or greenhouses. The findings show that using these natural enemies can effectively reduce the pest population, especially conservation efforts that support these natural enemies in the environment. The current review is crucial for developing eco-friendly ways to protect crops and reduce reliance on chemical pesticides, benefiting farmers and the environment.

Abstract

It is essential to consolidate knowledge on biological control agents (BCAs) for Drosophila suzukii, to identify gaps, evaluate the effectiveness of existing strategies, and guide future research toward sustainable pest management. The biological control of SWD has been explored through various BCAs, focusing on parasitoids, predators, and entomopathogens. We conducted a systematic review using Web of Science and Scopus (2012–2023) to investigate global research on BCAs of SWD. Our goal was to synthesize and categorize the current scientific production, addressing questions such as (1) publication numbers per BCA group and species, (2) key BCAs, (3) common methodologies (laboratory, field, greenhouse, or combined), (4) research scope, (5) effectiveness of BCAs, and (6) countries conducting research. We found 585 records, 184 of which were suitable for analysis. The most studied BCAs are parasitoids, comprising 64% of publications, with Trichopria drosophilae and Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae being the most researched, followed by Leptopilina japonica and Ganaspis kimorum. Entomopathogens and predators represent 26% and 7% of publications, respectively. Studies under controlled conditions predominate, and surveys, identifications, and characterization of natural enemies are the main research foci, followed by conservation biological control showing the highest effectiveness.

1. Introduction

The spotted-wing drosophila (SWD), Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura, 1931) (Diptera: Drosophilidae), has become a significant global pest in the last decade damaging berry crops [1] such as strawberry (Fragaria spp.) (Rosaceae), blackberry (Rubus spp.) (Rosaceae), blueberry (Vaccinium spp.) (Ericaceae), and raspberry (Rubus spp.) (Rosaceae) [2]. The species is mainly a pest of berries, such as cherry, raspberry, blueberry, mulberry, and strawberry [3] but also attacks grapes (Vitis vinifera) (Vitaceae), oranges (Citrus spp.) (Rutaceae) and guava (Psidium guajava) (Myrtaceae) [4,5,6].

The species is native to Southeast Asia and has been established in various regions worldwide, including North America [7], South America [8], North Africa [9], Central America [10], Europe [5], and Oceania [11]. Their widespread distribution is attributed to their high potential for dispersal [7], tolerance of a broad range of climatic conditions [5], and wide host range. The damage caused by SWD occurs due to the female’s ability to pierce the fruit’s epidermis to lay eggs in healthy fruits [12,13,14] and subsequently by the consumption of the mesocarp by the larvae, causing significant economic impact [5,15,16,17].

Economic loss was estimated by Bolda et al. [18] to have a potential impact of USD 511.3 million on strawberries, blueberries, raspberries, blackberries, and cherries in California, Oregon, and Washington, United States of America (USA). Also, in the USA, DiGiacomo et al. [19] reported losses of 20% of raspberry production in Minnesota. De Ros et al. [20] estimated losses of EUR 3.3 million in Trento, Italy. In South America, Morales [21] estimated production losses between USD 5000 and 17,550 per hectare for cherries and USD 4000 for blueberries in Ñuble, Chile. In Brazil, Benito et al. [22] estimated potential revenue losses of up to USD 21.4 million for peaches and USD 7.8 million for figs. In addition to production losses, pest control costs increased considerably, with a 37% drop in revenue in raspberries and 20% in strawberries in California due to increased insecticide costs [23].

Chemical control with pyrethroid, organophosphate, spinosyn, and neonicotinoid insecticides has been widely used to control SWD populations [24,25]. Spraying these pesticides adversely affects the environment and human health [11,26] and the possibility of generating resistance [27]. From this perspective, biological control of SWD is crucial to mitigate the economic and environmental damage caused by this invasive pest through sustainable management [28].

Therefore, this article aims to investigate the current status, limitations, and research opportunities on SWD’s biological control through a comprehensive review, highlighting successful cases. More specifically, we seek to answer the following questions: (1) What is the most studied biological control agent (BCA) group? (2) What are the most studied species contributing to SWD management? (3) What are the most common methods used in research (laboratory, greenhouse, or field)? (4) What is the commonly adopted scope of research (conservation, classical, augmentative, or survey)? (5) How was control success determined in biocontrol studies?

2. Materials and Methods

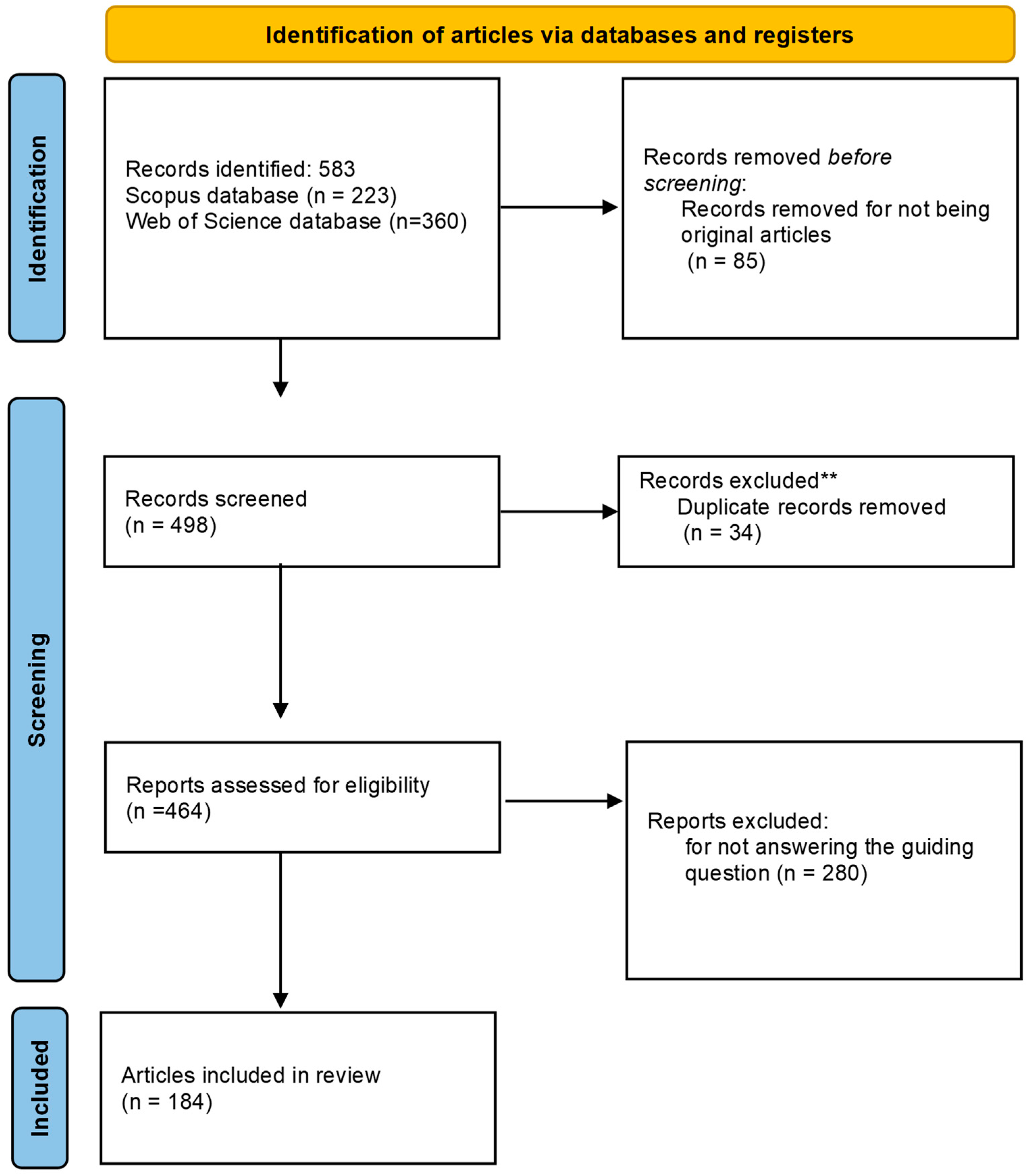

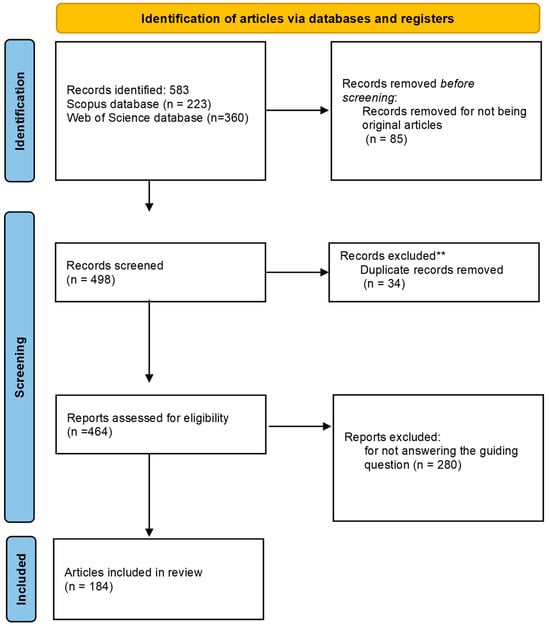

We conducted a comprehensive review on scientific articles following the guidelines of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA statement and checklist (Supplementary File S1); http://www.prisma-statement.org) (accessed on 25 February 2024) [29,30]. All references of all publications found (see Figure 1; global flowchart) are available in Supplementary File S2.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the PRISMA 2020 recommendation for selecting articles for systematic review on the use of biological control agents for Drosophila suzukii. ** Records exclude for being present in both databases.

2.1. Search Strategy, Screening, and Eligibility Criteria

Two databases were used to search for published articles evaluating the use of BCAs on D. suzukii. The databases consulted were Scopus (from 1960 to 2023) and Web of Science Core Collection (1864 to 2023). Searches were performed in January 2024, using the terms: “spotted-wing drosophila” AND “biological control” OR “natural enem*” OR “parasitoid” OR “predator” OR “bacteria” OR “fungi” OR “virus” OR “nematode*”

The screening strategy included selecting publications in Portuguese, Spanish, and English and peer-reviewed journal materials. We did not use review articles, books, book chapters, conference papers, scientific notes editorials, and articles prior to 2012 and after 2023. Two criteria were used in the publication: (1) articles that include SWD; (2) articles that used one or more BCAs of SWD in a pest control context. No articles published before 2012 met the search criteria, justifying the initial period adjusted in the search.

Based on these eligibility criteria, the first search using the string terms resulted in 583 publication records, of which 399 publications were considered unfit to proceed with information extraction.

2.2. Data Extraction

Our search resulted in 184 publications suitable for review (see Supplementary File S1). From the extracted data (digital object identifier “DOI”, title, abstract, and year of publication), it was possible to extract the following information: (1) the number of publications by BCA groups and species (parasitoids, predators, bacteria, fungi, viruses, nematodes, and multiple agents); (2) scope of the article, such as surveys including competition, interaction, laboratory trials, and natural/conservation, classical or augmentative biological control trials; (3) methodology used (laboratory tests, greenhouse conditions, field or combined); (4) evidence of the success of the BCA, obtained through the conclusion of the study on effectiveness, efficiency, and control; (5) countries where the article was developed. Competition, interaction, or laboratory evaluation studies were included as survey research. Diversity studies and new records of biological control agents were included as natural biological control articles. We used the location of the first author for each article without information about the research location. The nomenclature for the species of the Ganaspis brasiliensis complex was based on Sosa-Calvo et al. [31]. When the strain G1 was cited in a publication, the name Ganaspis kimorum was used; when G3 was cited, Ganaspis lupini was used, and when G5 was cited, G. brasiliensis was used. Species from China, Japan, and South Korea in which the strain was not mentioned were referred to as G. kimorum or lupini. In the other cases where the strain was absent, the geographic location was considered according to the distribution of these species.

2.3. Data Analysis

The graphs were generated using the “ggplot2” package [32] and with the addition of silhouettes from the “rplylopic” package [33] using R software version 4.3.2 [34].

3. Results

3.1. Publications Evaluating BCAs for SWD

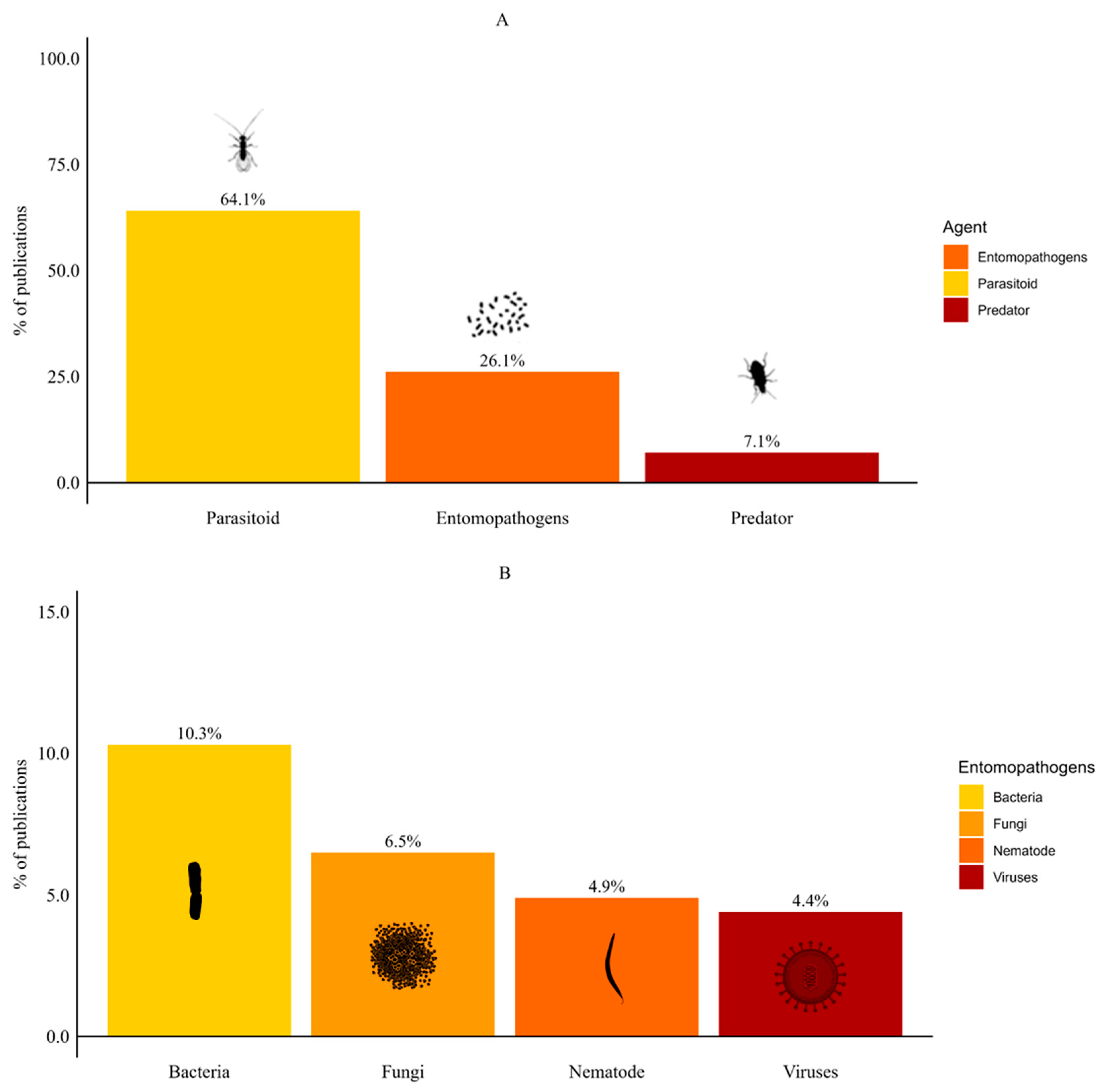

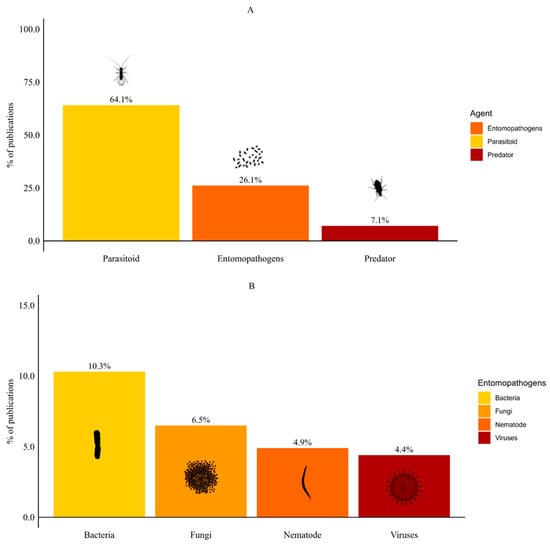

Most publications on the biological control of SWD focused on parasitoids (64.1%), with the remaining groups comprising ≤ 10% each (Figure 2A). Among entomopathogens, publications focused on bacteria (10.3%), followed by fungi (6.5%), nematodes (4.9%) and viruses (4.4%) (Figure 2B). Publications on predators were less common (7.1%). In addition, five publications (2.7%) evaluated more than one BCA. Four publications combined nematodes with another BCA group (fungus, parasitoid, bacteria or predator). Only one publication assessed the use of parasitoids combined with predators.

Figure 2.

Types of biological control agents for spotted-wing drosophila. (A) Comparison among parasitoids, entomopathogens, and predators. (B) Distribution of entomopathogens into bacteria, fungi, nematodes, and viruses.

3.1.1. Parasitoids

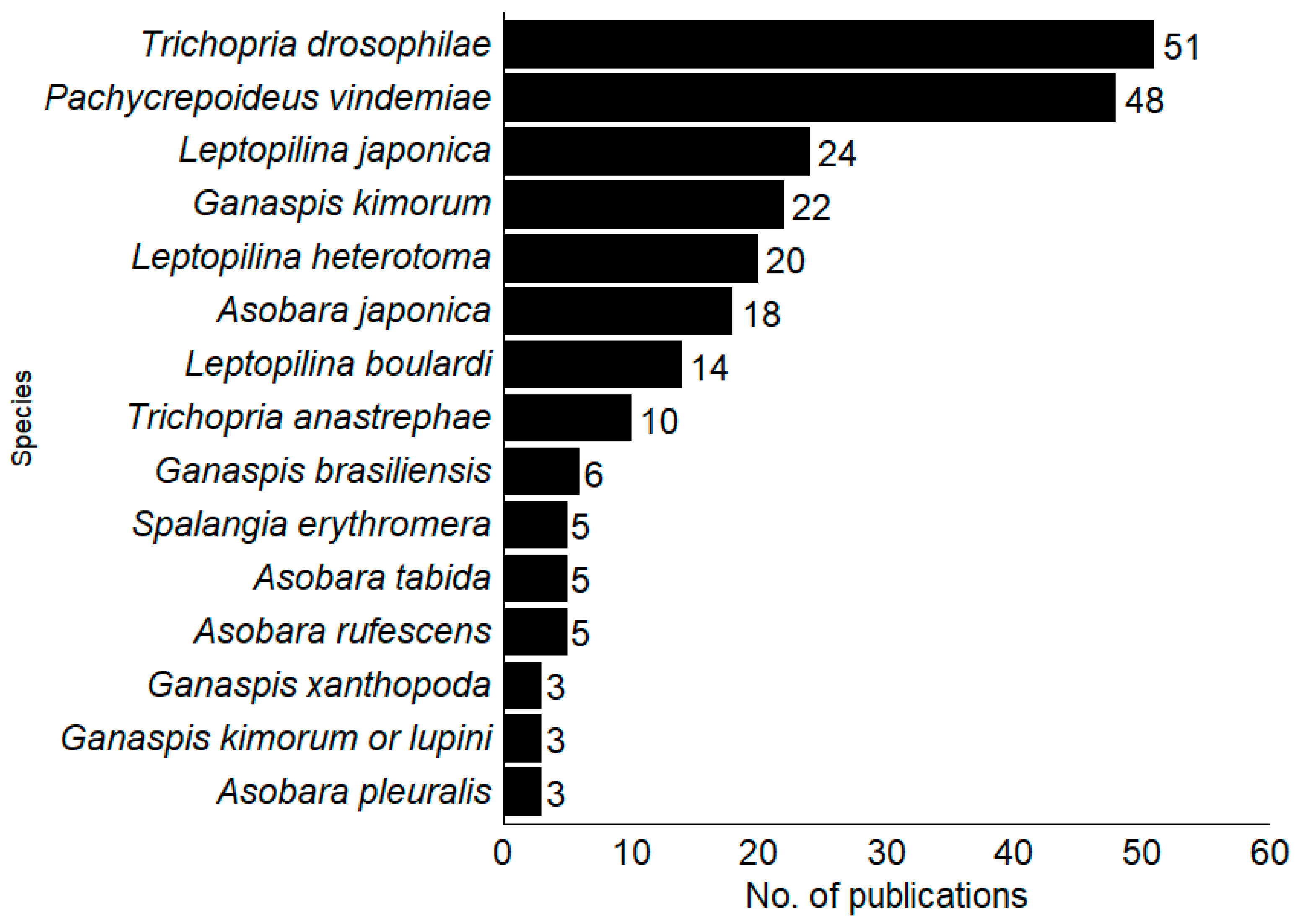

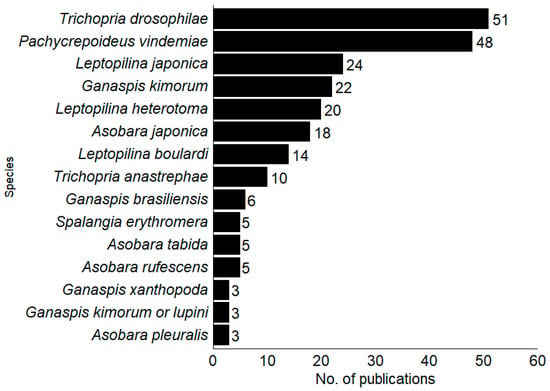

Among the 120 publications on parasitoids (Hymenoptera) presented, 44 species were found to parasitize SWD. The Figitidae family was the most studied (46%; n = 21), followed by Braconidae (33%; n = 15) and Pteromalidae (13%; n = 6). The ten most studied SWD parasitoids worldwide were the pupal parasitoids Trichopria drosophilae (Perkins), T. anastrephae Lima (Hymenoptera, Diapriidae) and Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae (Rondani) (Hymenoptera, Pteromalidae) and larval Ganaspis kimorum Buffington, G. brasiliensis (Ilhering), Leptopilina japonica Novkovic and Kimura, L. heterotoma (Thomson) and L. boulardi Barbotin, Carton and Keiner-Pillault (Hymenoptera, Figitidae) and Asobara japonica Belokobylskij, A. rufescens (Förster) (Hymenoptera, Braconidae) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Parasitoid species have the highest number of articles, with the percentage of studies focused on each parasitoid species worldwide.

3.1.2. Entomopathogens

Twenty-three bacteria were recorded in publications on BCAs. Bacteria species such as Xenorhabdus nematophila (Poinar and Thomas), Brevibacillus laterosporus (Laubach), Bacillus thuringiensis Berliner (Bt), Oenococcus oeni (Garvie), Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides Farrow, also presented promising publications. Eight families of viruses were reported infecting D. suzukii. La Jolla virus (Iflaviridae) appears in four publications. Other viruses, including Drosophila C virus (DCV) (Picornaviridae), Newfield virus (Permutotetraviridae), Drosophila A virus (DAV) and cricket paralysis virus (CrPV) (Dicistroviridae), Flock house virus (FHV) and Nagamuna virus (Nodaviridae), Sawaicho virus (Kitaviridae), Tama virus (Solemoviridae), Mogami virus (Chuvirus), and Notori virus (Phasmaviridae), were also investigated. Nine publications on nematodes evaluated as BCAs were also found. Steinernema carpocapsae (Weiser), Heterorhabditis bacteriophora Poinar, and Steinernema feltiae (Filipjev) were reported by the majority of articles. Among the entomopathogenic fungi, Beauveria bassiana Bals. (Vuill.), Metarhizium anisopliae (Metschn.) Sorokin and Isaria fumosorosea Wize stood out with seven, seven, and six publications, respectively.

3.1.3. Predators

The review identified 15 species of predators from eight insect families. Of these, the families Anthochoridae (Hemiptera) and Carabidae (Coleoptera) stand out with four species each, and the species Dolatia coriaria (Kraatz) (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) contained the most articles as a BCA. The minute pirate bug Orius insidiosus (Say, 1832) (Hemiptera: Anthocoridae) was studied in three publications, while green lacewing Chrysoperla carnea (Stephens) (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) and European earwig Forficula auricularia L. (Dermaptera: Forficulidae) had two articles each. Other species, each with one publication, include the ground beetle Bembidion quadrimaculatum (L.), Limodromus assimilis (Paykull), Poecilus cupreus (L.), Pterostichus melanarius (Illiger) (Coleoptera: Carabidae), the true bugs Dicyphus hesperus Knight, Macrolophus pygmaeus (Rambur) and Nesidiocoris tenuis (Reuter) (Hemiptera: Miridae), Orius laevigatus (Fieber) and Orius majusculus (Reuter) (Hemiptera: Thripidae), Podisus maculiventris (Say) (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae), and Gryllus pennsylvanicus Burmeister (Orthoptera: Grillidae).

3.2. Evaluation of Publications on Biological Control Agents of Spotted-Wing Drosophila

3.2.1. Methodology and Scope of Studies

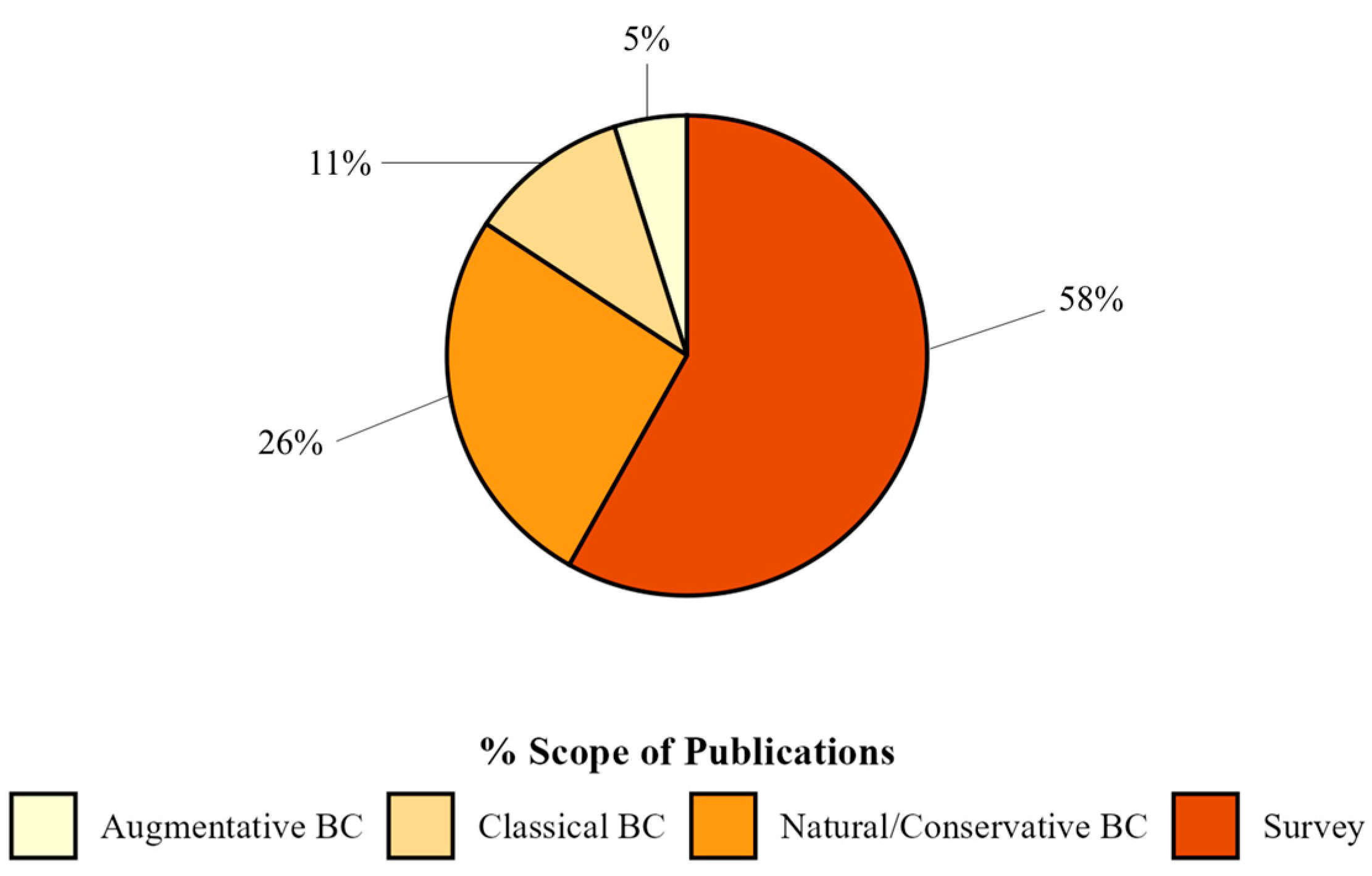

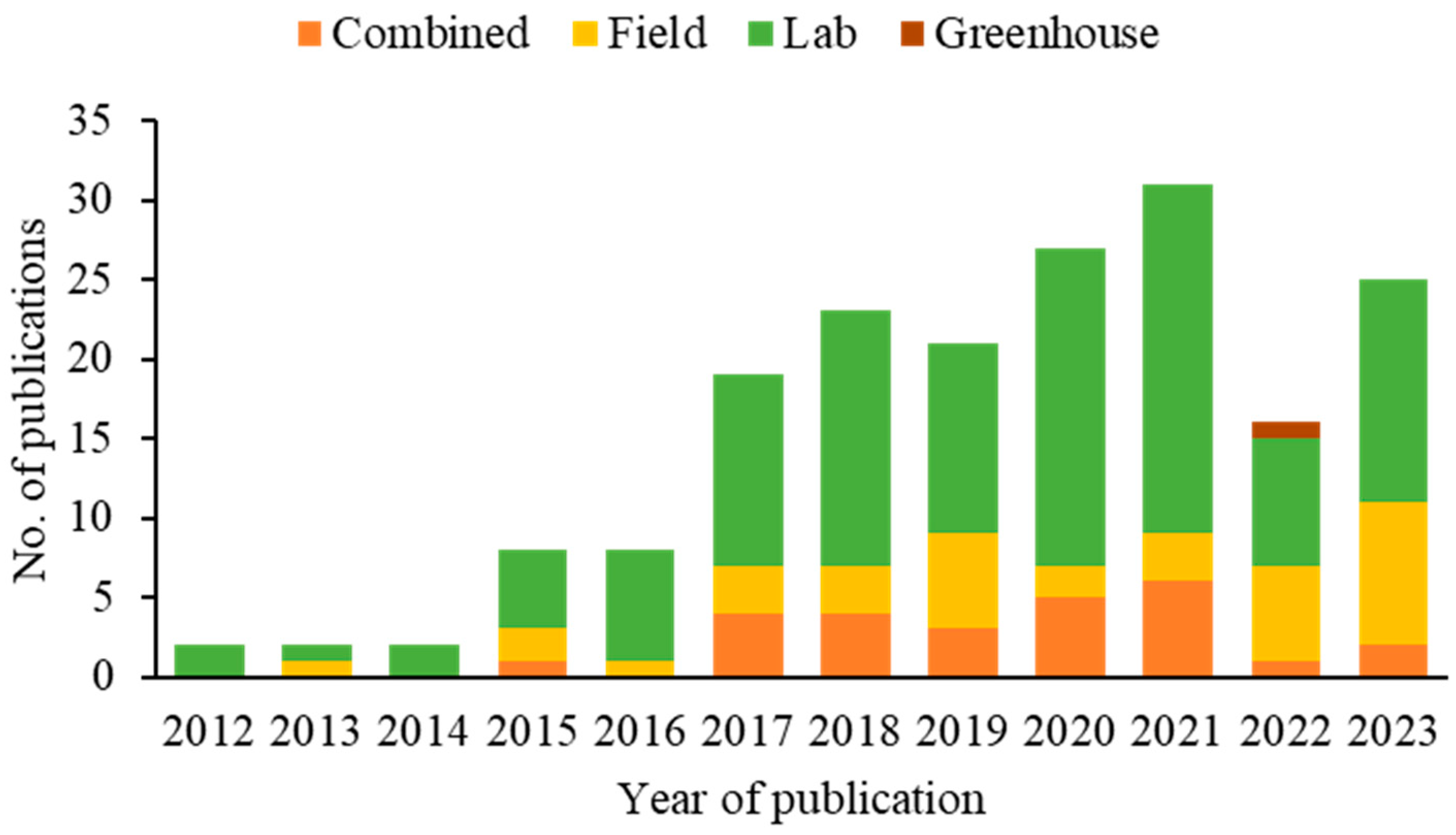

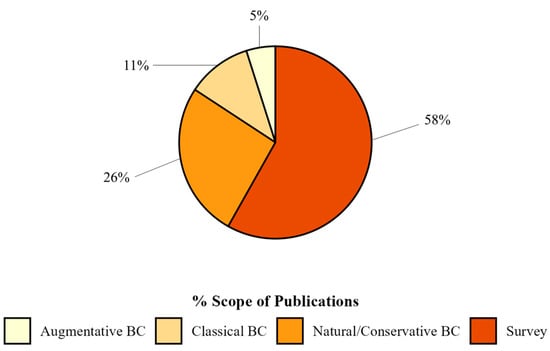

Regarding methodologies, the majority of publications had experiments conducted in the laboratory (66%), while 15% of the articles were field studies. In addition, 18% of the publications adopted a combined approach, integrating multiple research contexts for a broader and more applicable understanding. Only 1% of the publications were in greenhouses (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Percentage of publications grouped by scope on biological control of spotted-wing drosophila found in Web of Science and Scopus databases.

More than half of the publications (58%) conducted surveys for SWD natural enemies (Figure 4). The remaining biological control approaches (42%) were categorized as natural/conservation biological control (26%; n = 48), which aimed to understand better and conserve natural ecological processes. In addition, 11% of the publications (n = 20) focused on classical biological control strategies, while 5% (n = 9) explored the potential of augmentative biological control.

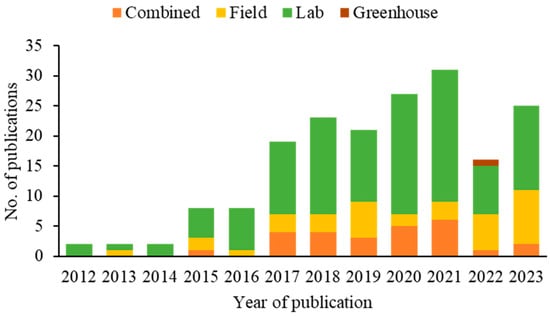

Over the years, the number of SWD biological control research publications has steadily increased. Only two publications were recorded in 2012, 2013, and 2014. However, from 2015 and 2016 onwards, a significant increase was observed, with the number of articles increasing to eight each year. This growth continued consistently in the following years, with a notable increase in 2021, reaching 31 publications (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Methodological approaches applied in publications on biocontrol agents of spotted-wing drosophila (2012–2023).

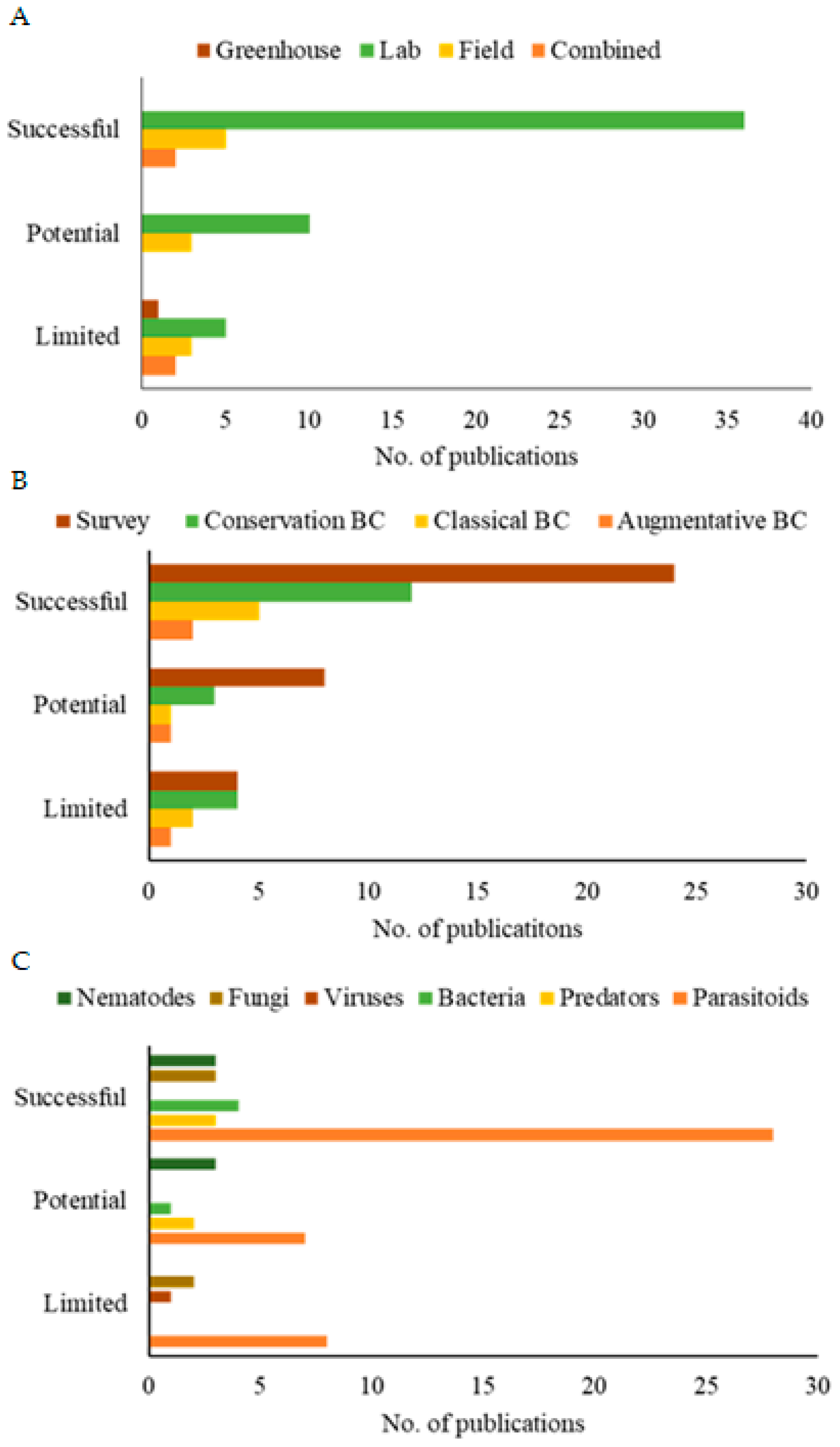

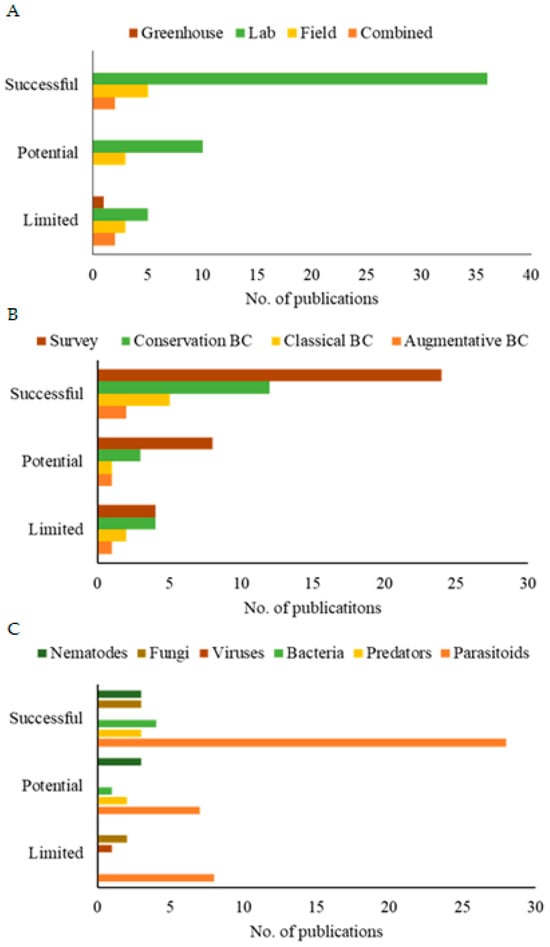

3.2.2. Evidence of Success

Regarding the efficacy of SWD biological control, approximately 60.9% (n = 112) of the publications showed that the BCA mitigated damage caused by the pest, thus encouraging the development of more efficient control strategies. However, 39.1% (n = 72) of the publications did not demonstrate efficacy, either due to the intricate nature of the research or the lack of effective results.

Many publications focused on identifying potential BCAs, and 63.6% (n = 117) of the publications did not report on the efficiency of the BCAs. However, the remaining 36.4% (n = 67) examined efficiency. Among these, 6% showed results of potential control < 30% against the pest, 7% showed potential control between 30 and 50%, and 23% were identified as successful, achieving > 50% control of SWD.

Laboratory studies revealed the highest average efficiency (59.1%), with a relatively moderate variation reflected in a standard deviation of 23.47. In contrast, field studies revealed an average efficiency of 42.94% with a slightly higher variation (standard deviation of 26.89) (Table 1). Both efficiency values (minimum and maximum) ranged from 7% to 93%. Greenhouse studies revealed an intermediate average but with greater observed variability, represented by a standard deviation of 39.84 due to the low sample size.

Table 1.

Efficiency in different approaches found in spotted-wing drosophila publications extracted from the Web of Science and Scopus databases.

Furthermore, the methodological analysis of the publications revealed that research in controlled environments demonstrated greater efficiency in evaluating the potential of SWD biocontrol agents, as evidenced by the significantly higher number of publications (Figure 6A). These publications make up the majority of the global literature on the subject. They may demonstrate the difficulty of transposing the results from the controlled environment to the natural environment of the pest. Furthermore, regarding the scope of these studies (Figure 6B), research that sought to identify biocontrol agents and those that used specimens from the environment itself (natural/conservation biological control) yielded more publications with successful efficiency as well as greater efficiency for parasitoids (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Publications on the efficacy of controlling spotted-wing drosophila using different methodological approaches (A), scope of study (B), and types of biological control agents (C) from 2012 to 2023. Efficiency parameters: limited (<30%); potential (30–50%); successful (>50%).

Considering the total number of publications that recommended the use of the BCA (termed effective in Table 2), T. drosophilae (14.6% of publications) and P. vindemmiae (11.5%) parasitoids currently stand out as the main biological control agents.

Table 2.

Percentage of publications demonstrating effectiveness (E1), efficiency (E2) (>50%), and effectiveness and efficiency in different approaches of the 10 most effective Drosophila suzukii biological control agents found in studies extracted from the Web of Science and Scopus databases.

The other BCAs were involved, at most, in 10% of studies that provided effective control. In addition, T. drosophilae and P. vindemmiae had more than a third of the publications rating them with >50% efficiency, and also showed higher percentages of parasitism at 38.6% and 34.2%, respectively. They were more effective and efficient in research in controlled environments (laboratory) than under natural conditions (field). Additionally, other control agents, such as B. bassiana and I. fumusorosea (93% efficiency) and the nematodes H. bacteriophora, S. feltiae, and S. carpocapsae (90% efficiency), were also efficient under these controlled conditions. In field conditions, greenhouse, or combined approaches, T. drosophilae showed the best results among the publications.

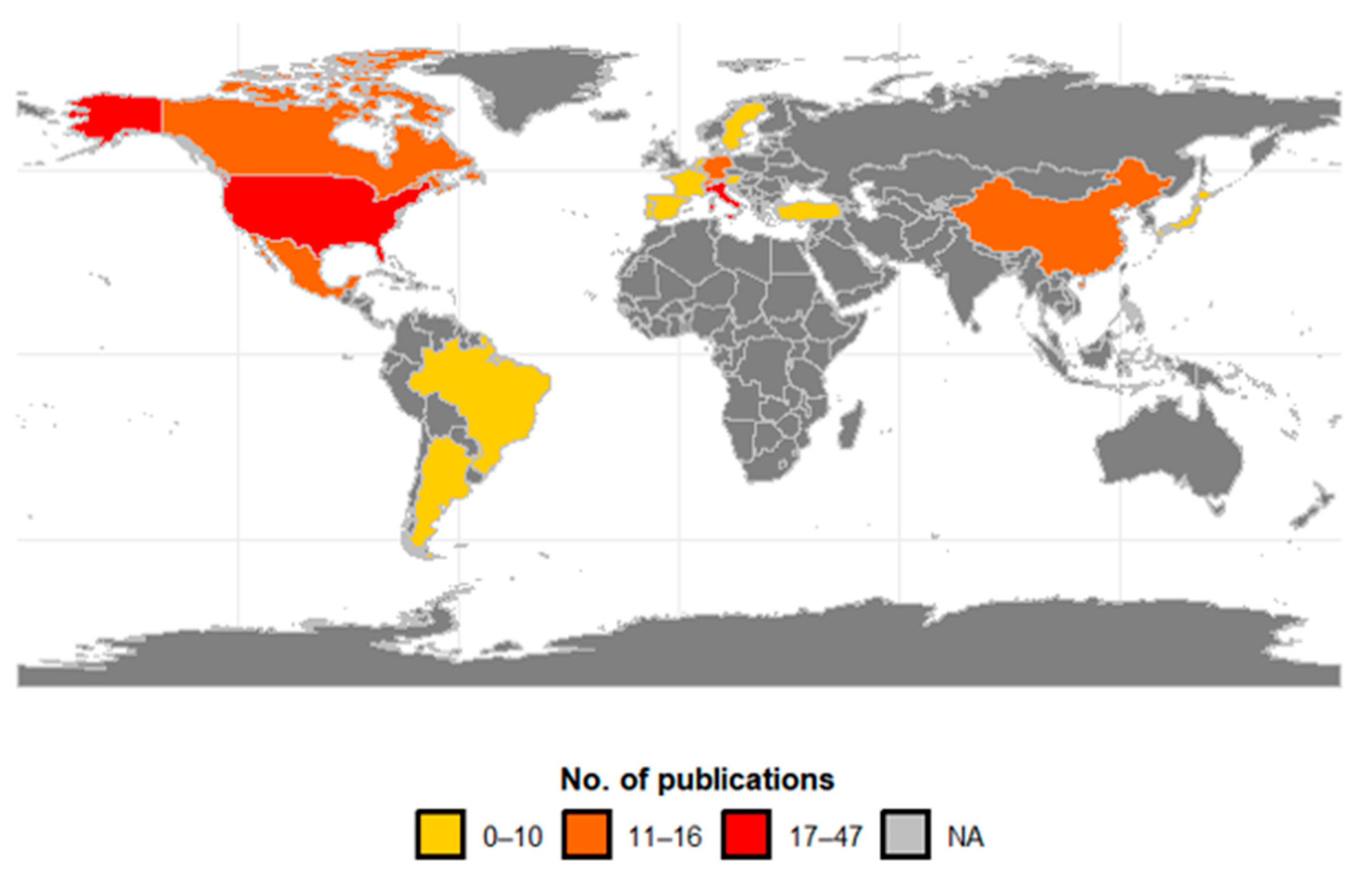

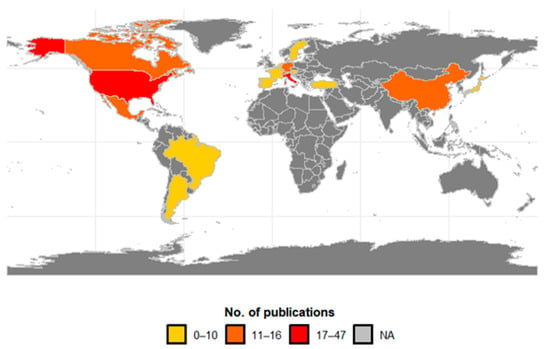

3.2.3. Countries with Research on BCAs Against SWD

Research on the biological control of SWD was concentrated in 20 countries (Figure 7), with 41% having been conducted in Europe, 40% in North America, 11% in Asia, and 9% in South America. Of the total research found in the databases, the USA produced a quarter of all publications (25.5%; n = 47), followed by Italy (9.2%; n = 17), Germany (8.7%; n = 16), and Switzerland (7.6%; n = 14). The main countries of the studies that research SWD in South America are Argentina (4.9%) and Brazil (3.8%). In Asia, China (6.5%) and Japan (3.3%) have recorded research on SWD in that continent. Central America, Africa, and Oceania did not record any publications, as the invasion of SWD is very recent in these continents.

Figure 7.

Geographical distribution of publications on biocontrol agents for spotted-wing drosophila by country. Publication intervals are represented by the colors: 0–10 (light yellow), 11–16 (orange), 17–47 (red), and NA (gray) indicating the absence of records.

4. Discussion

Biological control is a safe and sustainable technology for pest management that uses natural enemies present in agroecosystems [35]. Here, we demonstrate this by quantifying publications that use BCAs to manage SWD throughout the world.

4.1. Frequently Reported Parasitoids for SWD Biological Control

More than half of the publications were about using parasitoids as biological control agents for SWD. Most studies to-date included solitary drosophilid pupal parasitoids in the families Pteromalidae and Diapriidae [28]. Pteromalidae are ectoparasitoids that oviposit in the hemocoel, between the puparium and the pupa [36], and Muscidifurax raptorellus Kogan and Legner, P. vindemmiae, Spalangia erythromera Forster, Spalangia simplex Perkins and Vrestovia fidenas (Walker) are known to parasitize SWD pupae. The Diapriidae are endoparasitoids, and Phaenopria spp., T. anastrephae, and T. drosophilae parasitized SWD [28].

Trichopriae drosophilae and G. kimorum have shown potential in controlling SWD populations. Trichopriae drosophilae can locate and parasitize the fly in several crops, including blueberries, cherries, and raspberries, both in the laboratory and the field [37,38]. Similarly, G. kimorum has reduced SWD populations in semi-field and field experiments [39]. In this regard, the greater specificity of G. kimorum against D. suzukii [40,41] has led several governments, such as Italy, Mexico and the USA, to approve releases of the parasitoid strain G1 [38,42,43,44,45,46]. Initial release efforts in Italy have confirmed the parasitoid’s ability to disperse, hibernate, and parasitize in the field [46]. Given recent releases of G. kimorum in Europe and the USA and the prevalence of the adventive larval–pupal parasitoid L. japonica in North America [47], these two species will likely become the focus of future publications.

In North America and Europe, research on native pupal ectoparasitoids has shown that P. vindemmiae and T. drosophilae parasitized, respectively, between 53% and 60% and between 38% and 76% of SWD pupae under laboratory conditions [48,49]. However, there are few publications focused on other native North American parasitoids that can utilize SWD pupae as hosts [50], and most of the parasitoids tested against SWD are not yet commercially available. Thus, it is essential to identify other effective native parasitoids that are easily accessible to berry growers in North America [51].

In addition, publications on parasitism in SWD highlight the potential of native and adapted parasitoids to control the pest. For example, the experimental adaptation of native parasitoids, such as specific pupal parasitoids, showed that the parasitism rate significantly increased after only three generations. In addition, the intrinsic competition between different parasitoids, such as P. vindemmiae and T. anastrephae, is explored to understand their dynamics [52,53]. Regarding parasitism capacity, Rossi-Stacconi and collaborators [37] showed a significant reduction (93%) in SWD emergence in field tests following the release of T. drosophilae.

In this review, eight parasitoid species were commonly studied, with at least ten published studies: A. japonica, G. kimorum, L. heterotoma, L. japonica, T. anastrephae, T. drosophiliae, and P. vindemmiae. These parasitoids differ by biological, physiological, and ecological factors and geographical distribution. Therefore, the applicability of each method varies according to the situations in which the pest is established. Among these physiological factors, it is interesting to investigate the different dietary sources of Drosophila spp. Parasitoids occur in various habitats, with the provision of multiple sources of sugar, such as tree sap, honeydew, and flowers, but mainly the food of the hosts, that is, fruit [54,55,56] The benefits associated with different sources of feeding for T. drosophilae and P. vindemmiae parasitoids were studied by Collatz and Romeis [57]. They offered flowers, infested and non-infested fruit, SWD hosts and honey droplets, or only honey; they showed that all the food sources extended the life expectancy of these parasitoids, justifying that one of the possible reasons for this effect is based on the provision of energy so that the female can parasitize the host.

Despite efforts to use T. drosophilae in North America and Europe for their ability to recognize SWD-infested and non-infested fruit in field and semi-field conditions [58], recent research in South America has focused on the pupal parasitoid T. anastrephae. They explored several aspects of the biocontrol agent, including the ability to parasitize under different laboratory conditions [52,59,60], competition with other parasitoids [53] and the toxicological effects of insecticides and essential oils [61]. Female T. anastrephae can recognize infested fruit or in stages of excessive ripeness, with larvae and pupae of the pest in strawberry crops. This parasitoid is capable of parasitizing the pest in infested strawberries and has a preference for fruit infested with eggs, larvae, and pupae compared to healthy and undamaged fruit [62].

Thus, the benefits of using parasitoids include their ability to attack different forms of SWD in the natural environment. Future efforts should focus on mass-producing these parasitoids, optimizing release strategies, as well as describing the potential risk of introduction in each country [11].

4.2. Frequently Reported Entomopathogens

Among the bacteria, X. nematophila and B. thuringiensis showed promising results in laboratory tests [28]. Hiebert et al. [63] searched for the composition and impact of bacteria associated with SWD, intending to develop effective and sustainable biological control strategies. They found the most effective bacteria to be L. pseudomesenteroides, known for its ability to block food intake in the SWD larvae, Brevibacterium frigoritolerans Delaporte and Sasson, as pathogenic for larvae and leading to a high mortality rate, and Bacillus simplex Priest et al., 1989 and Bacillus altitudinis Shivaji et al., 2006 both with deleterious effects on fly survival after oral infection. The identification of these microbes through different infection routes [64] can offer viable paths for candidates for biological control through survival analysis due to the pathogenic load provided by the control agent.

The main entomopathogenic fungi used in SWD control are B. bassiana, M. anisopliae, and I. fumosorosea. These fungi are evaluated by their ability to infect and kill SWD under controlled conditions [65]. The authors did not find virulence in SWD inoculated with M. anisopliae but did with B. bassiana under laboratory conditions. However, the application of B. bassiana in the field was not promising for virulence against SWD. Despite this, other studies indicated no significant differences in pathogenicity and virulence levels between M. anisopliae and B. bassiana [66]. When evaluated from the perspective of exposure time and adhesion to the SWD cuticle, the fungi may have a beneficial effect. Galland et al. [67], assessing five entomopathogenic fungi exposed to the pest for 10 s, 1 min, 10 min, 1 h, or 3 h, found that B. bassiana was more efficient, killing 50% of flies in four days with a 3 h exposure, while it took six days to achieve the same result with 10 s of exposure and ten days for the fungus to be 95% lethal to SWD individuals.

The nematodes tested against SWD that demonstrated potential, especially in laboratory settings, were S. carpocapsae, H. bacteriophora, and S. feltiae. Furthermore, S. carpocapsae has some efficacy in controlling SWD by infecting and killing larvae inside infested fruits [68]. However, its effectiveness can be influenced by soil type, humidity, temperature, and other environmental factors. In this sense, the SWD fly infection by the nematode Steirnenema rarum (De Doucet) PAM 25 to 14 °C at a concentration of 4.000 IJs/mL seems to significantly reduce the longevity of the pest [69]. In addition, efficacy may also be associated with how the pest’s immune pathways respond to the presence or absence of a nematode–bacteria complex. In some cases, S. carpocapsae is not recognized by the immune system of SWD larvae without the release of bacteria and the activation of genes that lead to the expression of antimicrobial peptides, rendering the cellular response inactive during infection [70].

Although fewer studies have focused on viruses, some research has identified several viral families that can infect SWD. The application of viruses as control agents is still in its early stages and requires further investigation to determine their practical use in the field. Recent research has identified La Jolla virus (LJV) (Picornavirales: Iflaviridae) as a possible biocontrol tool, showing pathogenic effects after oral administration, with infection causing reduced adult survival and interrupting larval development during pupation. In addition, LJV remained stable and infectious under different pH and temperature conditions, demonstrating its potential as an effective biological control agent against SWD [71]. Viruses, such as Newfield (NFV), can cause significant declines in female fertility through infection of follicular epithelium [72].

4.3. Frequently Studied Predators

Predators of SWD belong to nine families in the orders Coleoptera, Dermaptera, Hemiptera, Neuroptera, and Orthoptera. Predators such as minute pirate bugs in the family Anthocoridae and beetles in the family Carabidae have been investigated for their potential to control SWD [73]. Moreover, Orius spp. (Anthocoridae) and certain carabids can effectively prey on SWD under laboratory and field conditions [74]. Predators such as earwigs, spiders, and ants contribute significantly to the reduction in SWD populations, particularly in semi-natural habitats such as hedgerows, where they play a crucial role in the population dynamics of the pest [75]. The predator Dolatia coriaria (Coleoptera: Staphylinidae) has shown promise due to its ability to feed on several stages of the pest, with a maximum consumption capacity of 26 first-instar larvae, 15 second-instar larvae and six third-instar larvae [76]. The authors emphasize promoting natural predators in agroecosystems from the perspective of sustainable integrated pest management, thus aiming to reduce inputs within rural properties.

4.4. Research Trends and Future Perspectives

Most studies on the BCAs of SWD have focused on the identification and characterization of natural enemies of this pest. Laboratory studies dominate the research literature, representing about 66% of all studies, while field studies and combined approaches make up the remainder. Tests carried out in controlled environments help describe the potential of biocontrol agents before conducting greenhouse or field research [5,28]. Laboratory studies can first confirm the efficacy potential of SWD’s natural enemies, which are then evaluated for impact in the field, i.e., the earwig (Forficula auricularia) was assessed in the lab and field [77].

Furthermore, studies on the specificity and efficacy of parasitoids using combined laboratory and field tests can provide important information relevant to classical biological control [28]. Fellin et al. [46] suggested expanding studies on the release of the Asian G1 lineage of Ganaspis cf. brasiliensis, currently recognized as Ganaspis kimorum Buffington, 2024 [31], since pre- and post-release evaluations revealed that the parasitoid was recaptured in 50% of the release sites in Trento, Italy. The parasitoid G. kimorum emerged mainly from fresh fruits still on the plant, survived the climatic conditions imposed by winter, and revealed no adverse effects on non-target species.

One of the main challenges in the research of BCAs for SWD is translating laboratory results into field applications. While controlled experiments are crucial for evaluating the potential efficacy of BCAs, environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and ecological interactions often confound efficacy in natural conditions. Furthermore, the lack of comprehensive studies in diverse cultivation environments, such as greenhouses and complex agricultural systems, limits the practical applicability of these findings.

Another significant challenge is the competition between biological agents, which can reduce their effectiveness when multiple BCAs are released simultaneously, necessitating more detailed studies on compatibility and the management of intraguild interactions. Wang et al. [35] showed that L. japonica generally outcompetes other parasitoids when multiple parasites attack a single host, depending on host conditions and density, emphasizing the need to consider the possibility of these interactions in management programs.

Other parasitoids also compete interspecifically, such as P. vindemmiae attacking pupae previously parasitized by T. anastrephae in the first instar stage [78]. Some competitors may have a physiological advantage, either by toxic secretion, induction of anoxia or nutritional deprivation or due to physical mechanisms [79,80,81], such as the sickle-shaped mandibles of T. anastrephae over the immaturity of P. vindemmiae [53].

Our review also identified a tendency of studies to focus on efforts to maintain natural enemies from the perspective of conservation biological control. Predators were demonstrated to remove a substantial proportion of SWD larvae in fruits or pupae in soil via predator inclusion/exclusion experiments [74,82]. Among efforts to encourage BCAs, an “augmentorium” [83] has been designed to rear parasitoids in-field by confining the pest while allowing the escape of parasitoids. This showed promise in field tests specific for SWD control, sustaining important native parasitoids and possibly associating with T. drosophilae releases [37,84].

In addition to technical and biological aspects, it is crucial to consider the environmental and social impacts of biocontrol strategies for SWD. BCAs can reduce the need for chemical pesticides, promote more sustainable agriculture, and minimize environmental damage. Studies have shown that the adoption of biological control can also benefit the health of agricultural workers and nearby communities by decreasing exposure to toxic substances [85,86]. Therefore, evaluating environmental and social impacts should be integral to biocontrol research to ensure that recommended practices are effective, sustainable, and safe.

Research on BCAs for SWD is distributed globally, with significant contributions from Europe (41.8%) and North America (39.7%), followed by Asia (9.8%) and South America (8.7%). The United States alone represents a substantial portion of this research. Studies from Asia and South America are also contributing to the growing body of knowledge on this subject [28].

Our review also identified that an important aspect is the diversity of biological control agents studied in different regions. For example, in Europe, much of the research has focused on parasitoids such as G. kimorum and T. drosophilae, while in North America, in addition to parasitoids, there is a significant focus on natural predators and nematodes. This diverse focus reflects the regional approaches and needs for controlling SWD [87]. It is essential to discuss how biological control agents adapt to each region’s local conditions. Studies in Asia have shown how local parasitoids are effective in reducing SWD populations under specific climatic conditions [29,40,88], while in South America, research focuses on the use of agents that can withstand high temperatures and humidity [8,89].

Another relevant point is the importance of international collaborations. Collaborative projects between European and American institutions have generated significant advances in developing biological control strategies. These partnerships facilitate the exchange of knowledge, technologies, and resources, thereby increasing the effectiveness of research and implementation control programs [87,90]. Finally, the implementation of research networks integrating scientists, agricultural producers, and policymakers can accelerate the development and adoption of more effective and sustainable biological control strategies for SWD management.

5. Conclusions

The review of biological control agents for Drosophila suzukii revealed insights into future advances, limitations, and perspectives. Entomopathogens such as bacteria, fungi, nematodes, and viruses have potential but are influenced by environmental factors and the pest’s immune response. Parasitoids, especially Trichopria drosophilae and Ganaspis kimorum, were effective under laboratory and field conditions, standing out as strong candidates for control programs.

Laboratory studies dominate, accounting for 66% of all research. This limits the applicability of findings to real-world conditions. Field studies are necessary to evaluate BCA performance under environmental variability and ecological complexity. Bridging this gap is crucial for the successful implementation of biocontrol strategies.

Regional research emphasized the importance of local adaptations. In Europe, G. kimorum and T. drosophilae were the primary focus. North American studies included predators and nematodes alongside parasitoids. Asian studies demonstrated the effectiveness of local parasitoids in specific climates, while South America focused on T. anastrephae for its resilience to heat and humidity. The most studied entomopathogens were the fungus Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae, and Isaria fumosorosea. Only Beauveria showed high efficiency under controlled conditions. Viruses demonstrated potential for biological control by reducing adult survival and interrupting the larval development of Drosophila suzukii.

Future research should prioritize field experiments to validate BCAs under natural conditions. Studies on the compatibility and synergy of combining parasitoids with predators or pathogens are essential. Research on intraguild predation must also advance. Strengthening international collaboration is key to sharing knowledge and developing effective global strategies against D. suzukii.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/insects16020133/s1, Supplementary File S1: PRISMA Checklist (reference [30]) and Supplementary File S2: Supplementary Information with all publications recorded.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.M.A., J.B., J.C.L., S.M.O. and F.R.M.G.; data curation, L.M.A. and J.B.; formal analysis, S.M.O., and F.R.M.G.; investigation, L.M.A., F.R.M.G., J.C.L. and S.M.O.; methodology, L.M.A. and F.R.M.G.; software, L.M.A. and J.B.; supervision, F.R.M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, L.M.A., J.B., J.C.L. and S.M.O.; writing—review and editing, L.M.A., J.C.L. and S.M.O.; funding acquisition, F.R.M.G. and J.C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES); Council of Technological and Scientific Development (CNPq) for a productivity grant to F.R.M.G: USDA-based funds CRIS 2072-22000 044-00D to J.C.L. and ARS Areawide program (National Program leader S. Young.) to J.C.L.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Council of Technological and Scientific Development of Brazil (CNPq) for the Scholarship of Research Productivity, USDA CRIS 2072-22000-044-00D, and the USDA ARS Areawide Program (led by National Program Leader S. Young).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tait, G.; Mermer, S.; Stockton, D.; Lee, J.; Avosani, S.; Abrieux, A.; Anfora, G.; Beers, E.; Biondi, A.; Burrack, H.; et al. Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae): A Decade of Research Towards a Sustainable Integrated Pest Management Program. J. Econ. Entomol. 2021, 114, 1950–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wollmann, J.; Schlesener, D.C.H.; Mendes, S.R.; Krüger, A.P.; Martins, L.N.; Bernardi, D.; Garcia, M.S.; Garcia, F.R.M. Infestation Index of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Small Fruit in Southern Brazil. Arq. Inst. Biol. 2020, 87, e0432018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schöneberg, T.; Arsenault-Benoit, A.; Taylor, C.M.; Butler, B.R.; Dalton, D.T.; Walton, V.M.; Petran, A.; Rogers, M.A.; Diepenbrock, L.M.; Burrack, H.J.; et al. Pruning of Small Fruit Crops Can Affect Habitat Suitability for Drosophila Suzukii. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2020, 294, 106860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization. Factsheet Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Spotted Wing Drosophila—A Pest from the EPPO Alert List. Available online: http://www.eppo.org/QUARANTINE/Alert_List/insects/Drosophila_suzukii_factsheet_12-2010.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2023).

- Cini, A.; Ioriatti, C.; Anfora, G. A Review of the Invasion of Drosophila suzukii in Europe and a Draft Research Agenda for Integrated Pest Management. Bull. Insectology 2012, 65, 149–160. [Google Scholar]

- Nunes, A.M.; Schlesener, D.C.H.; Souza, D.S.; Neumann, A.M.; Garcia, F.R.M. Primeiros Registros de Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Em Agroecossistemas Na Metade Sul Do Rio Grande Do Sul. In Proceedings of the XXV Congresso Brasileiro De Entomologia, Goiânia, Brazil, 14–18 September 2014; Sociedade Brasileira de Entomologia: Goiânia, Brazil, 2014; p. 1344. Available online: https://www.seb.org.br/admin/files/book/book_nTi2y3ZTHwRm.pdf (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Hauser, M. A Historic Account of the Invasion of Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura) (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in the Continental United States, with Remarks on Their Identification. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 1352–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreazza, F.; Bernardi, D.; dos Santos, R.S.S.; Garcia, F.R.M.; Oliveira, E.E.; Botton, M.; Nava, D.E. Drosophila Suzukii in Southern Neotropical Region: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Neotrop. Entomol. 2017, 46, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouantar, M.; Anfora, G.; Boharoud, R.; Chebli, B. First Report of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophiladae) in North Africa. Moroc. J. Agric. Sci. 2020, 1, 277–279. Available online: https://www.techagro.org/index.php/MJAS/article/view/869 (accessed on 25 July 2024).

- Chacón-Cerdas, R.; Gonzalez-Herrera, A.; Alvarado-Marchena, L.; González-Fuentes, F. Report of the Establishment of Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura, 1931) (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Central America. Entomol. Commun. 2024, 6, ec06003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.R.M.; Lasa, R.; Funes, C.F.; Buzzetti, K. Drosophila suzukii Management in Latin America: Current Status and Perspectives. J. Econ. Entomol. 2022, 115, 1008–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreves, A.J.; Walton, V.; Fisher, G.A. A New Pest Attacking Healthy Ripening Fruit in Oregon: Spotted Wing Drosophila. Available online: https://catalog.extension.oregonstate.edu/em8991 (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Lee, J.C.; Dreves, A.J.; Cave, A.M.; Kawai, S.; Isaacs, R.; Miller, J.C.; Van Timmeren, S.; Bruck, D.J. Infestation of Wild and Ornamental Noncrop Fruits by Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2015, 108, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschbaum, D.S.; Funes, C.F.; Buonocore-Biancheri, M.J.; Suárez, L.; Ovruski, S.M. The Biology and Ecology of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). In Drosophila suzukii Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 41–91. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, D.B.; Bolda, M.P.; Goodhue, R.E.; Dreves, A.J.; Lee, J.; Bruck, D.J.; Walton, V.M.; O’Neal, S.D.; Zalom, F.G. Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae): Invasive Pest of Ripening Soft Fruit Expanding Its Geographic Range and Damage Potential. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2011, 2, G1–G7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, V.M.; Burrack, H.J.; Dalton, D.T.; Isaacs, R.; Wiman, N.; Ioriatti, C. Past, Present and Future of Drosophila suzukii: Distribution, Impact and Management in United States Berry Fruits. Acta Hortic. 2016, 1117, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ros, G. The Economic Analyses of the Drosophila Suzukii’s Invasions: A Mini-Review. Neotrop. Entomol. 2024, 53, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolda, M.P.; Goodhue, R.E.; Zalom, F.G. Spotted Wing Drosophila: Potential Economic Impact of Newly Established Pest. ARE Update 2010, 13, 5–8. Available online: https://s.giannini.ucop.edu/uploads/giannini_public/81/fe/81feb5c9-f722-4018-85ec-64519d1bbc95/v13n3_2.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- DiGiacomo, G.; Hadrich, J.; Hutchison, W.D.; Peterson, H.; Rogers, M. Economic Impact of Spotted Wing Drosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Yield Loss on Minnesota Raspberry Farms: A Grower Survey. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2019, 10, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ros, G.; Anfora, G.; Grassi, A.; Ioriatti, C. The Potential Economic Impact of Drosophila Suzukii on Small Fruits Production in Trentino (Italy). In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference of Integrated Fruit Production, Kusadasi, Turkey, 7–12 October 2012; Ioriatti, C., Altindisli, F.O., Børve, J., Escudero-Colomar, L.A., Lucchi, A., Molinari, F., Eds.; 2013; pp. 317–321. Available online: https://iobc-wprs.org/product/iobc-wprs-bulletin-vol-91-2013/ (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Buzzetti Morales, K. The Spotted Wing Drosophila in the South of the World: Chilean Case and Its First Productive Impacts. In Invasive Species—Introduction Pathways, Economic Impact, and Possible Management Options; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Benito, N.P.; Lopes-da-Silva, M.; Santos, R.S.S. dos Potential Spread and Economic Impact of Invasive Drosophila suzukii in Brazil. Pesqui. Agropecu. Bras. 2016, 51, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhue, R.E.; Bolda, M.; Farnsworth, D.; Williams, J.C.; Zalom, F.G. Spotted Wing Drosophila Infestation of California Strawberries and Raspberries: Economic Analysis of Potential Revenue Losses and Control Costs. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 1396–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, D.; Molitor, D.; Beyer, M. Natural Compounds for Controlling Drosophila Suzukii. A Review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 39, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawer, R. Chemical Control of Drosophila suzukii. In Drosophila suzukii Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Giunti, G.; Benelli, G.; Palmeri, V.; Laudani, F.; Ricupero, M.; Ricciardi, R.; Maggi, F.; Lucchi, A.; Guedes, R.N.C.; Desneux, N.; et al. Non-Target Effects of Essential Oil-Based Biopesticides for Crop Protection: Impact on Natural Enemies, Pollinators, and Soil Invertebrates. Biol. Control 2022, 176, 105071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gress, B.E.; Zalom, F.G. Identification and Risk Assessment of Spinosad Resistance in a California Population of Drosophila suzukii. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 1270–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Daane, K.M.; Hoelmer, K.A.; Lee, J.C. Biological Control of Spotted-Wing Drosophila: An Update on Promising Agents. In Drosophila suzukii Management; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 143–167. [Google Scholar]

- Cogo, F.D. Introdução à Revisão Sistemática e Meta-Análise Aplicadas à Agricultura, 1st ed.; Cogo, F.D., Ed.; Editora UEMG: Belo Horizonte, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sosa-Calvo, J.; Forshage, M.; Buffington, M.L. Circumscription of the Ganaspis brasiliensis (Ihering, 1905) Species Complex (Hymenoptera, Figitidae), and the Description of Two New Species Parasitizing the Spotted Wing Drosophila, Drosophila suzukii Matsumura, 1931 (Diptera, Drosophilidae). J. Hymenopt. Res. 2024, 97, 441–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Wickham, M.H. Package ‘Ggplot2’. Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics. Version 2016, 2, 1–189. Available online: https://search.r-project.org/CRAN/refmans/ggplot2/html/ggplot2-package.html (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Gearty, W.; Jones, L.A. Rphylopic: An R Package for Fetching, Transforming, and Visualising PhyloPic Silhouettes. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2023, 14, 2700–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: https://r-project.org/index.html (accessed on 15 November 2024).

- Wang, X.; Hogg, B.N.; Hougardy, E.; Nance, A.H.; Daane, K.M. Potential Competitive Outcomes among Three Solitary Larval Endoparasitoids as Candidate Agents for Classical Biological Control of Drosophila Suzukii. Biol. Control 2019, 130, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacsoh, B.Z.; Schlenke, T.A. High Hemocyte Load Is Associated with Increased Resistance against Parasitoids in Drosophila Suzukii, a Relative of D. Melanogaster. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi Stacconi, M.V.; Amiresmaeili, N.; Biondi, A.; Carli, C.; Caruso, S.; Dindo, M.L.; Francati, S.; Gottardello, A.; Grassi, A.; Lupi, D.; et al. Host Location and Dispersal Ability of the Cosmopolitan Parasitoid Trichopria Drosophilae Released to Control the Invasive Spotted Wing Drosophila. Biol. Control 2018, 117, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Cabrera, J.; Moreno-Carrillo, G.; Sanchez-Gonzalez, J.A.; Mendoza-Ceballos, M.Y.; Arredondo-Bernal, H.C. Single and Combined Release of Trichopria drosophilae (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) to Control Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Neotrop. Entomol. 2019, 48, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daane, K.M.; Wang, X.-G.; Biondi, A.; Miller, B.; Miller, J.C.; Riedl, H.; Shearer, P.W.; Guerrieri, E.; Giorgini, M.; Buffington, M.; et al. First Exploration of Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii in South Korea as Potential Classical Biological Agents. J. Pest Sci. 2016, 89, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girod, P.; Lierhmann, O.; Urvois, T.; Turlings, T.C.J.; Kenis, M.; Haye, T. Host Specificity of Asian Parasitoids for Potential Classical Biological Control of Drosophila Suzukii. J. Pest Sci. 2018, 91, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seehausen, M.L.; Valenti, R.; Fontes, J.; Meier, M.; Marazzi, C.; Mazzi, D.; Kenis, M. Large-Arena Field Cage Releases of a Candidate Classical Biological Control Agent for Spotted Wing Drosophila Suggest Low Risk to Non-Target Species. J. Pest Sci. 2022, 95, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, A.; Wang, X.; Daane, K.M. Host Preference of Three Asian Larval Parasitoids to Closely Related Drosophila Species: Implications for Biological Control of Drosophila suzukii. J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94, 273–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daane, K.M.; Wang, X.; Hogg, B.N.; Biondi, A. Potential Host Ranges of Three Asian Larval Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii. J. Pest Sci. 2021, 94, 1171–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beers, E.H.; Beal, D.; Smytheman, P.; Abram, P.K.; Schmidt-Jeffris, R.; Moretti, E.; Daane, K.M.; Looney, C.; Lue, C.-H.; Buffington, M. First Records of Adventive Populations of the Parasitoids Ganaspis brasiliensis and Leptopilina japonica in the United States. J. Hymenopt. Res. 2022, 91, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisi, F.; Mansour, R.; Cavallaro, C.; Alınç, T.; Porcu, E.; Ricupero, M.; Zappalà, L.; Desneux, N.; Biondi, A. Sublethal Effects of Nine Insecticides on Drosophila suzukii and Its Major Pupal Parasitoid Trichopria drosophilae. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 5003–5014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fellin, L.; Grassi, A.; Puppato, S.; Saddi, A.; Anfora, G.; Ioriatti, C.; Rossi-Stacconi, M.V. First Report on Classical Biological Control Releases of the Larval Parasitoid Ganaspis brasiliensis against Drosophila suzukii in Northern Italy. BioControl 2023, 68, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariepy, T.D.; Abram, P.K.; Adams, C.; Beal, D.; Beers, E.; Beetle, J.; Biddinger, D.; Brind’Amour, G.; Bruin, A.; Buffington, M.; et al. Widespread Establishment of Adventive Populations of Leptopilina japonica (Hymenoptera, Figitidae) in North America and Development of a Multiplex PCR Assay to Identify Key Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera, Drosophilidae). NeoBiota 2024, 93, 63–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-G.; Kaçar, G.; Biondi, A.; Daane, K.M. Foraging Efficiency and Outcomes of Interactions of Two Pupal Parasitoids Attacking the Invasive Spotted Wing Drosophila. Biol. Control 2016, 96, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabert, S.; Allemand, R.; Poyet, M.; Eslin, P.; Gibert, P. Ability of European Parasitoids (Hymenoptera) to Control a New Invasive Asiatic Pest, Drosophila Suzukii. Biol. Control 2012, 63, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thistlewood, H.M.; Gibson, G.A.; Gillespie, D.R.; Fitzpatrick, S.M. Drosophila suzukii (Matsumura), Spotted Wing Drosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae). In Biological Control Programmes in Canada 2001–2012; Mason, P.G., Gillespie, D.R., Eds.; CAB International: Wallinford, UK, 2013; pp. 152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Bonneau, P.; Renkema, J.; Fournier, V.; Firlej, A. Ability of Muscidifurax Raptorellus and Other Parasitoids and Predators to Control Drosophila suzukii Populations in Raspberries in the Laboratory. Insects 2019, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, A.P.; Scheunemann, T.; Vieira, J.G.A.; Morais, M.C.; Bernardi, D.; Nava, D.E.; Garcia, F.R.M. Effects of Extrinsic, Intraspecific Competition and Host Deprivation on the Biology of Trichopria anastrephae (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) Reared on Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Neotrop. Entomol. 2019, 48, 957–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Costa Oliveira, D.; Stupp, P.; Martins, L.N.; Wollmann, J.; Geisler, F.C.S.; Cardoso, T.D.N.; Bernardi, D.; Garcia, F.R.M. Interspecific Competition in Trichopria Anastrephae parasitism (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) and Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae) Parasitism on Pupae of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Phytoparasitica 2021, 49, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleury, F.; Gibert, P.; Ris, N.; Allemand, R. Chapter 1 Ecology and Life History Evolution of Frugivorous Drosophila Parasitoids. Adv. Parasitol. 2009, 70, 3–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kremmer, L.; Thaon, M.; Borowiec, N.; David, J.; Poirié, M.; Gatti, J.-L.; Ris, N. Field Monitoring of Drosophila Suzukii and Associated Communities in South Eastern France as a Pre-Requisite for Classical Biological Control. Insects 2017, 8, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivellone, V.; Meier, M.; Cara, C.; Pollini Paltrinieri, L.; Gugerli, F.; Moretti, M.; Wolf, S.; Collatz, J. Multiscale Determinants Drive Parasitization of Drosophilidae by Hymenopteran Parasitoids in Agricultural Landscapes. Insects 2020, 11, 334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collatz, J.; Romeis, J. Flowers and Fruits Prolong Survival of Drosophila Pupal Parasitoids. J. Appl. Entomol. 2021, 145, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, S.; Boycheva-Woltering, S.; Romeis, J.; Collatz, J. Trichopria Drosophilae Parasitizes Drosophila suzukii in Seven Common Non-Crop Fruits. J. Pest Sci. 2020, 93, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.G.A.; Krüger, A.P.; Scheuneumann, T.; Morais, M.C.; Speriogin, H.J.; Garcia, F.R.M.; Nava, D.E.; Bernardi, D. Some Aspects of the Biology of Trichopria anastrephae (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae), a Resident Parasitoid Attacking Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Brazil. J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 113, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, J.G.A.; Krüger, A.P.; Scheuneumann, T.; Garcez, A.M.; Morais, M.C.; Garcia, F.R.M.; Nava, D.E.; Bernardi, D. Effect of Temperature on the Development Time and Life-time Fecundity of Trichopria anastrephae Parasitizing Drosophila suzukii. J. Appl. Entomol. 2020, 144, 857–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesener, D.C.H.; Wollmann, J.; de Bastos Pazini, J.; Padilha, A.C.; Grützmacher, A.D.; Garcia, F.R.M. Insecticide Toxicity to Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Parasitoids: Trichopria anastrephae (Hymenoptera: Diapriidae) and Pachycrepoideus vindemmiae (Hymenoptera: Pteromalidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2019, 112, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, A.P.; Garcez, A.M.; Scheunemann, T.; Nava, D.E.; Garcia, F.R.M. Trichopria Anastrephae as a Biological Control Agent of Drosophila Suzukii in Strawberries. Neotrop. Entomol. 2024, 53, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiebert, N.; Carrau, T.; Bartling, M.; Vilcinskas, A.; Lee, K.-Z. Identification of Entomopathogenic Bacteria Associated with the Invasive Pest Drosophila suzukii in Infested Areas of Germany. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2020, 173, 107389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bing, X.; Winkler, J.; Gerlach, J.; Loeb, G.; Buchon, N. Identification of Natural Pathogens from Wild Drosophila suzukii. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 1594–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alnajjar, G.; Drummond, F.A.; Groden, E. Laboratory and Field Susceptibility of Drosophila suzukii Matsumura (Diptera: Drosophilidae) to Entomopathogenic Fungal Mycoses. J. Agric. Urban Entomol. 2017, 33, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Palomares, V.M.; Paulino-Alonso, L.; Gutierrez, J.Z.; Alatorre-Rosas, R. Pathogenicity and Virulence of Isaria javanica, Metarhizium anisopliae, and Beauveria bassiana Strains for Control of Drosophila Suzukii (Matsumura). Southwest. Entomol. 2021, 46, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galland, C.D.; Lalaymia, I.; Declerck, S.; Verheggen, F. Efficacy of Entomopathogenic Fungi against the Fruit Fly Drosophila Suzukii and Their Side Effects on Predator and Pollinator Insects. Entomol. Gen. 2023, 43, 1203–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foye, S.; Steffan, S.A. A Rare, Recently Discovered Nematode, Oscheius onirici (Rhabditida: Rhabditidae), Kills Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Within Fruit. J. Econ. Entomol. 2020, 113, 1047–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, J.J.; de Brida, A.L.; Jean-Baptiste, M.C.; Bernardi, D.; Wilcken, S.R.S.; Leite, L.G.; Garcia, F.R.M. Effectiveness of Steinernema rarum PAM 25 (Rhabditida: Steinernematidae) Against Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 2022, 115, 967–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, A.; Toubarro, D.; Simões, N.; Morton, A.; García-del-Pino, F. The Modulation Effect of the Steinernema carpocapsae—Xenorhabdus Nematophila Complex on Immune-Related Genes in Drosophila suzukii Larvae. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2023, 196, 107870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linscheid, Y.; Kessel, T.; Vilcinskas, A.; Lee, K.-Z. Pathogenicity of La Jolla Virus in Drosophila suzukii Following Oral Administration. Viruses 2022, 14, 2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner-Montero, G.; Luque, C.M.; Cesar, C.S.; Ding, S.D.; Day, J.P.; Jiggins, F.M. Hunting Drosophila Viruses from Wild Populations: A Novel Isolation Approach and Characterisation of Viruses. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1010883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Englert, C.; Herz, A. Acceptability of Drosophila suzukii as Prey for Common Predators Occurring in Cherries and Berries. J. Appl. Entomol. 2019, 143, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballman, E.S.; Collins, J.A.; Drummond, F.A. Pupation Behavior and Predation on Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) Pupae in Maine Wild Blueberry Fields. J. Econ. Entomol. 2017, 110, 2308–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siffert, A.; Cahenzli, F.; Kehrli, P.; Daniel, C.; Dekumbis, V.; Egger, B.; Furtwengler, J.; Minguely, C.; Stäheli, N.; Widmer, F.; et al. Predation on Drosophila suzukii within Hedges in the Agricultural Landscape. Insects 2021, 12, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renkema, J.M.; Telfer, Z.; Gariepy, T.; Hallett, R.H. Dalotia Coriaria as a Predator of Drosophila suzukii: Functional Responses, Reduced Fruit Infestation and Molecular Diagnostics. Biol. Control 2015, 89, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, A.; Fountain, M.T.; Wijnen, H.; Shaw, B. Potential of the European Earwig (Forficula auricularia) as a Biocontrol Agent of the Soft and Stone Fruit Pest Drosophila suzukii. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 3340–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcez, A.M.; Krüger, A.P.; Nava, D.E. Intrinsic Competition between 2 Pupal Parasitoids of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 2023, 116, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusumano, A.; Peri, E.; Bradleigh Vinson, S.; Colazza, S. Interspecific Extrinsic and Intrinsic Competitive Interactions in Egg Parasitoids. BioControl 2012, 57, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, J.A.; Poelman, E.H.; Tanaka, T. Intrinsic Inter- and Intraspecific Competition in Parasitoid Wasps. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2013, 58, 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, C.; Afonso, C.; Gonçalves, C.I.; Branco, M. Assessing the Competitive Interactions between Two Egg Parasitoids of the Eucalyptus Snout Beetle, Gonipterus Platensis, and Their Implications for Biological Control. Biol. Control 2019, 130, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woltz, J.M.; Lee, J.C. Pupation Behavior and Larval and Pupal Biocontrol of Drosophila suzukii in the Field. Biol. Control 2017, 110, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguine, J.-P.; Atiama-Nurbel, T.; Douraguia, E.; Rousse, P. The Augmentorium, a Tool for Agroecological Crop Protection. Design, Implementation and Evaluation on Farm Conditions on Reunion Island. Cah. Agric. 2011, 20, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppato, S.; Grassi, A.; Cristofaro, A.; Ioriatti, C. Augmentorium: A Sustainable Technique for Conservation Biological Control of Drosophila suzukii; IOBC: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 178–181. Available online: https://iobc-wprs.org/product/augmentorium-a-sustainable-technique-for-conservation-biological-control-of-drosophila-suzukii/ (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Georghiou, G.P.; Lagunes-Tejeda, A. The Occurrence of Pesticide Resistance in Arthropods: An Index of Cases Reported Through 1989; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lopes, C.V.A.; Albuquerque, G.S.C. de Agrotóxicos e Seus Impactos Na Saúde Humana e Ambiental: Uma Revisão Sistemática. Saúde Debate 2018, 42, 518–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.C.; Wang, X.; Daane, K.M.; Hoelmer, K.A.; Isaacs, R.; Sial, A.A.; Walton, V.M. Biological Control of Spotted-Wing Drosophila (Diptera: Drosophilidae)—Current and Pending Tactics. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 2019, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-G.; Nance, A.H.; Jones, J.M.L.; Hoelmer, K.A.; Daane, K.M. Aspects of the Biology and Reproductive Strategy of Two Asian Larval Parasitoids Evaluated for Classical Biological Control of Drosophila suzukii. Biol. Control 2018, 121, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlesener, D.C.H.; Wollmann, J.; Krüger, A.P.; Martins, L.N.; Teixeira, C.M.; Bernardi, D.; Garcia, F.R.M. Effect of Temperature on Reproduction, Development, and Phenotypic Plasticity of Drosophila suzukii in Brazil. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 2020, 168, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haye, T.; Girod, P.; Cuthbertson, A.G.S.; Wang, X.G.; Daane, K.M.; Hoelmer, K.A.; Baroffio, C.; Zhang, J.P.; Desneux, N. Current SWD IPM Tactics and Their Practical Implementation in Fruit Crops across Different Regions around the World. J. Pest Sci. 2016, 89, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).