Effect of Processing Parameters on the Heating Uniformity of Postharvest Tobacco Leaves Subjected to Radio Frequency Disinfestations

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

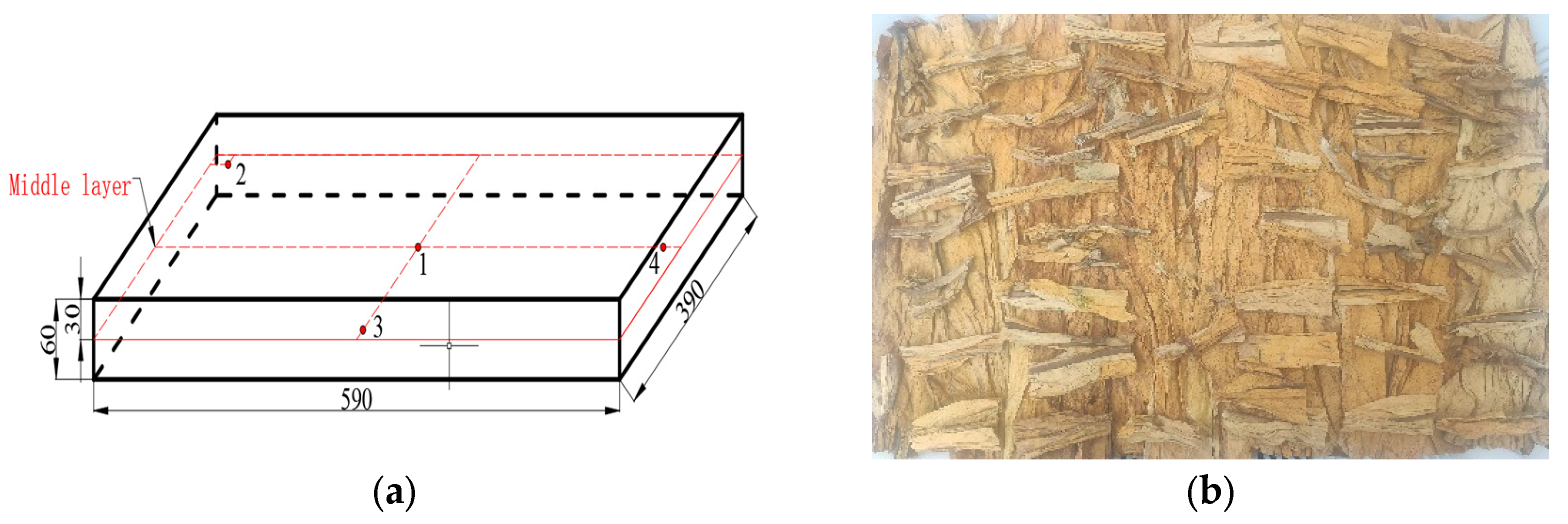

2.1. Tobacco Leaves Preparation

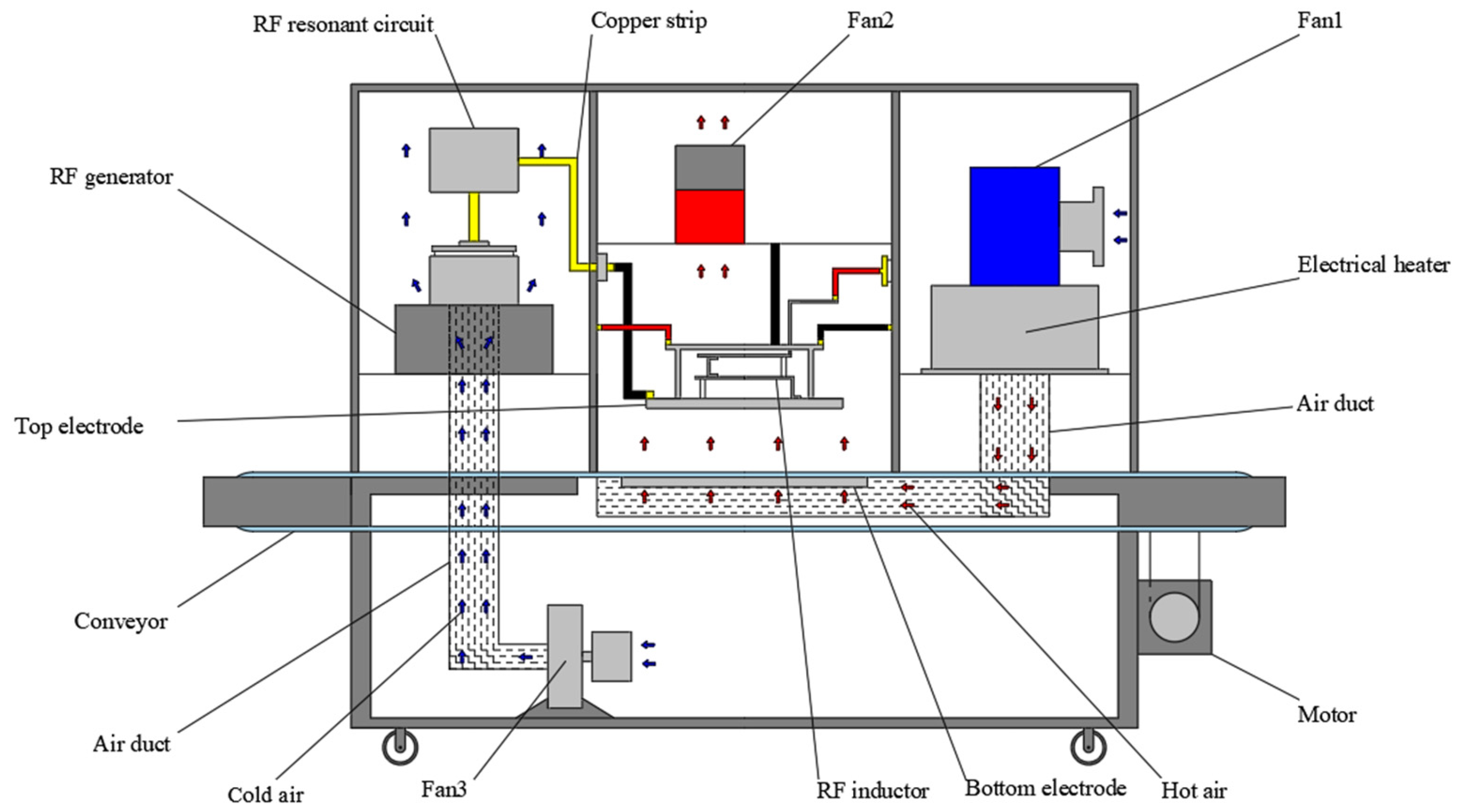

2.2. RF Heating System

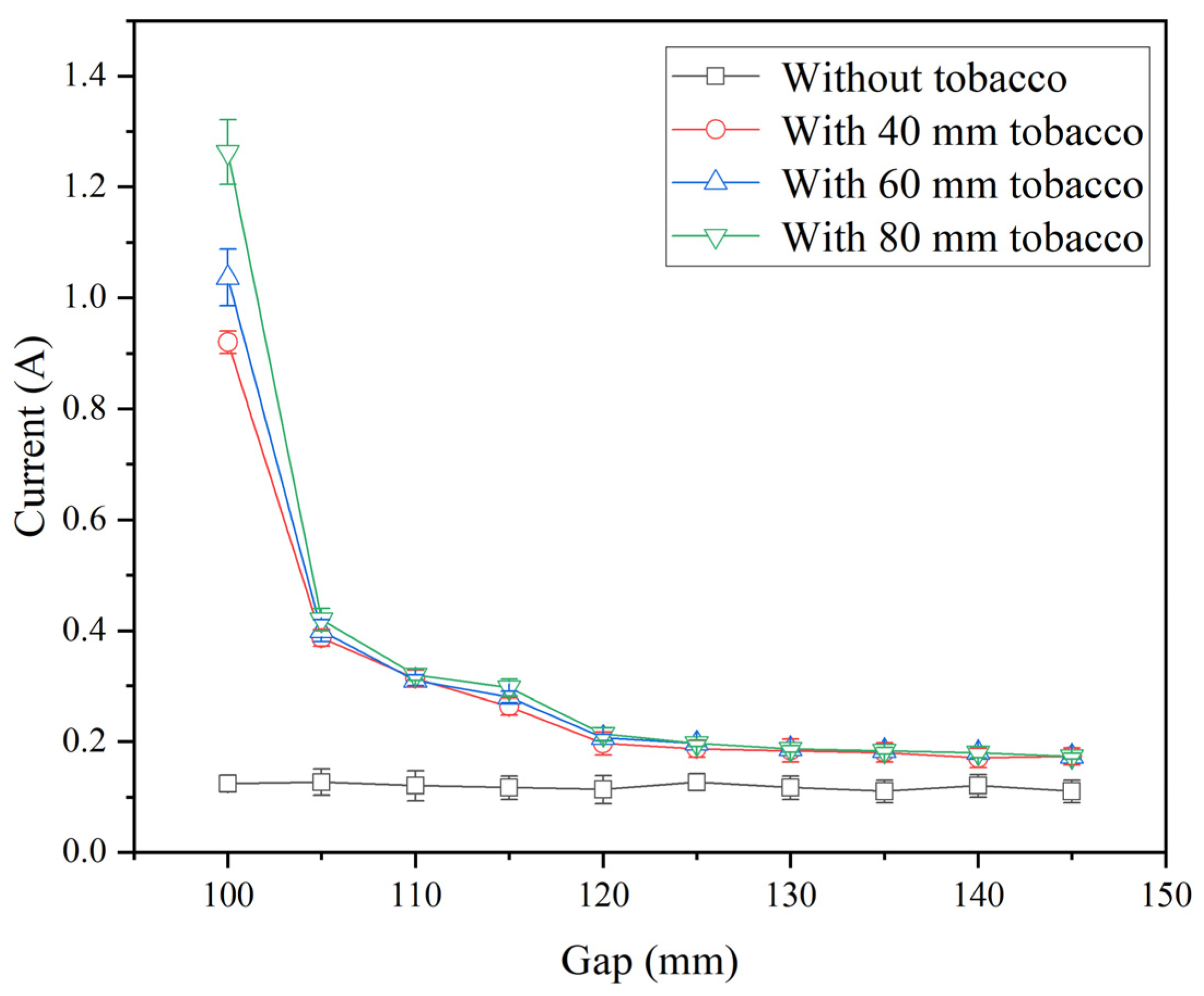

2.3. Determination of Electrode Gap and Conveyor Belt Speed

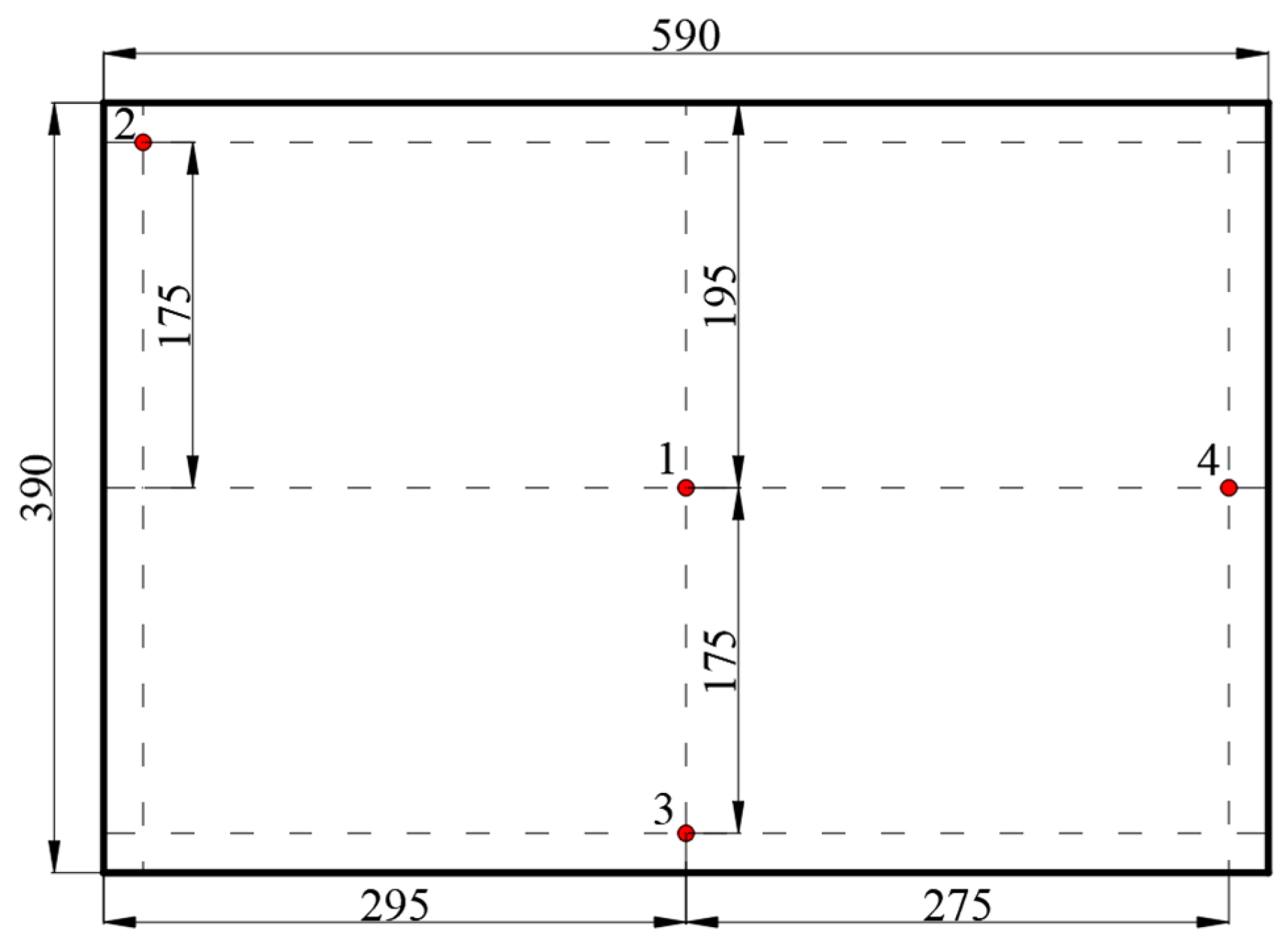

2.4. Evaluation of RF Heating Uniformity

2.5. Analysis of Energy Efficiency for the RF Heating System

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Anode Current of RF System Under Different Electrode Gaps and Sample Thicknesses

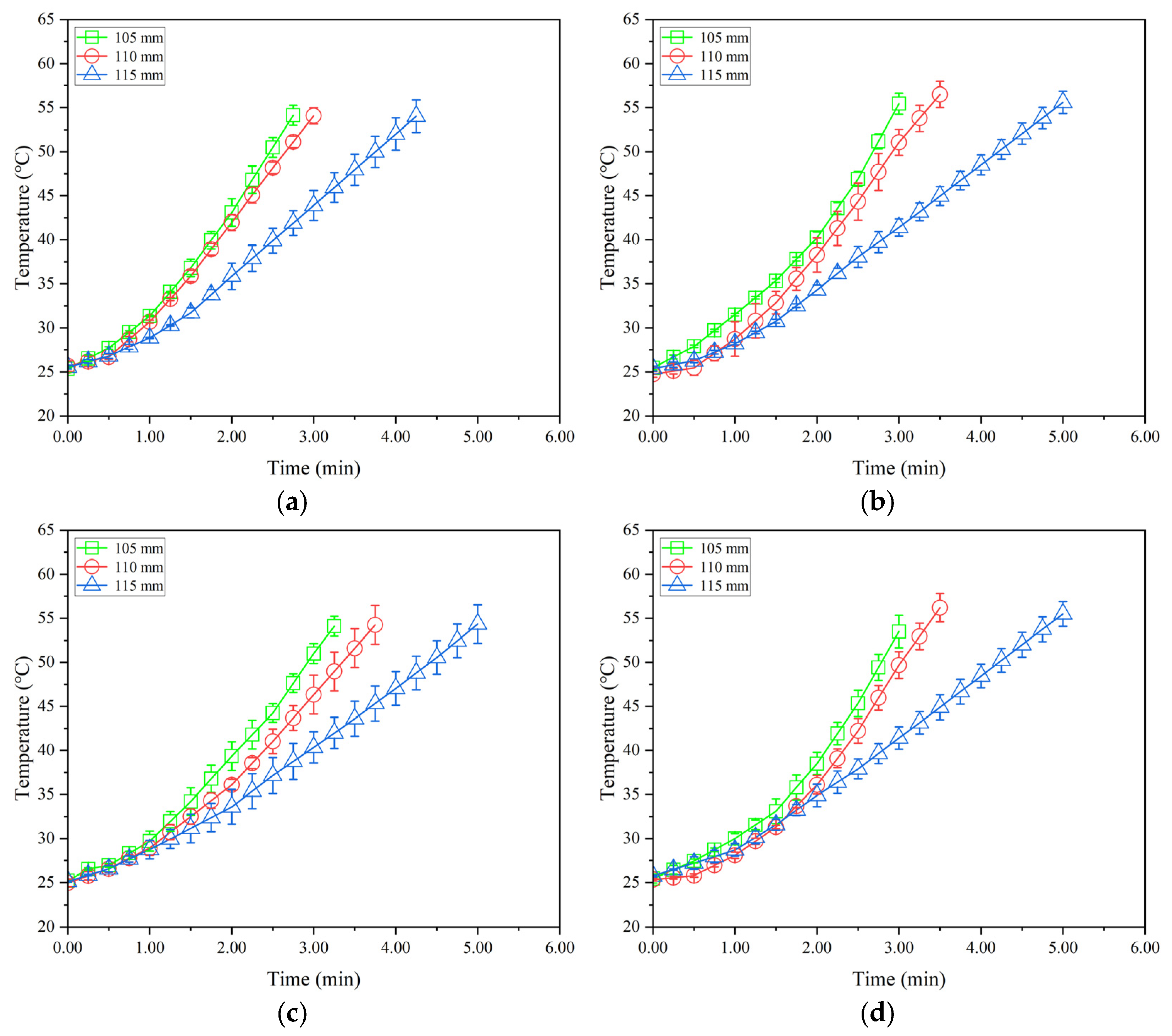

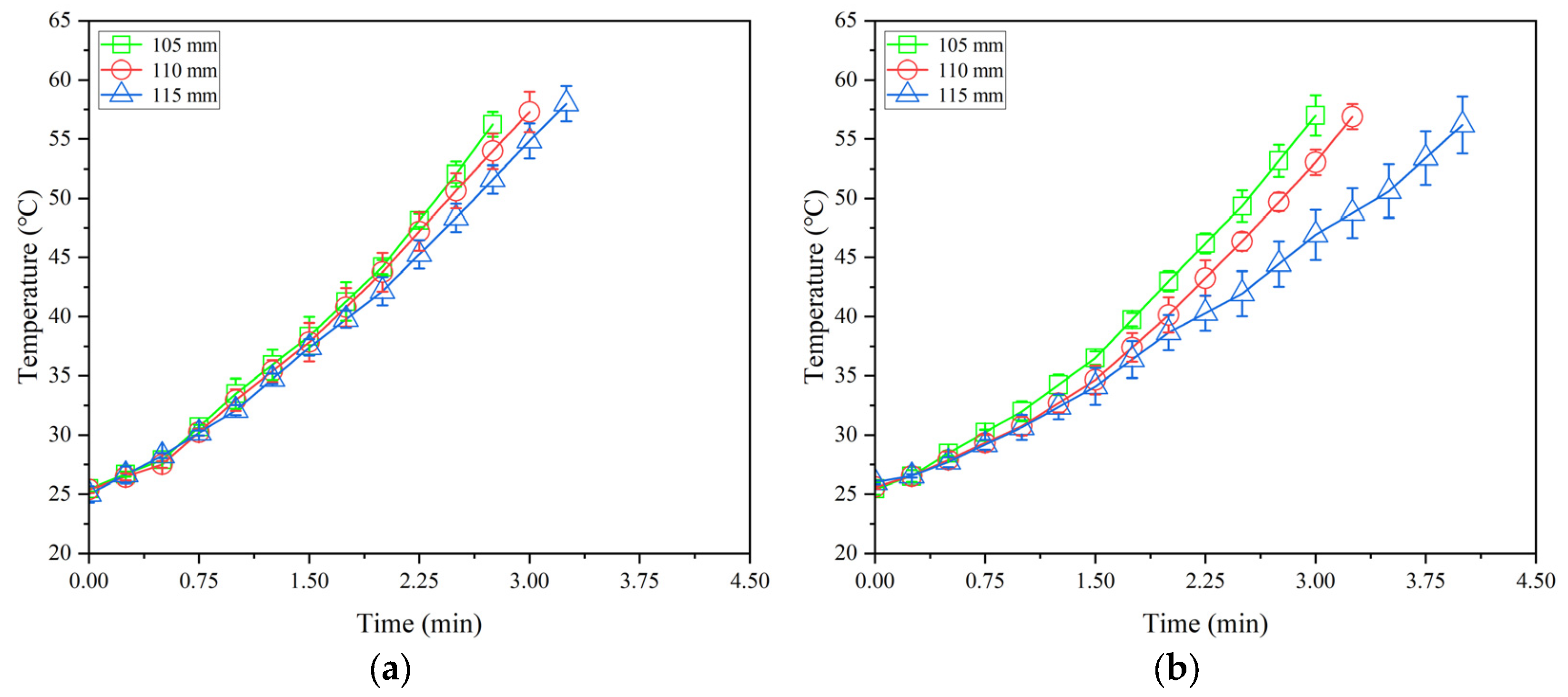

3.2. Effect of the Electrode Gap and Sample Thickness on the RF Heating Rate and Uniformity

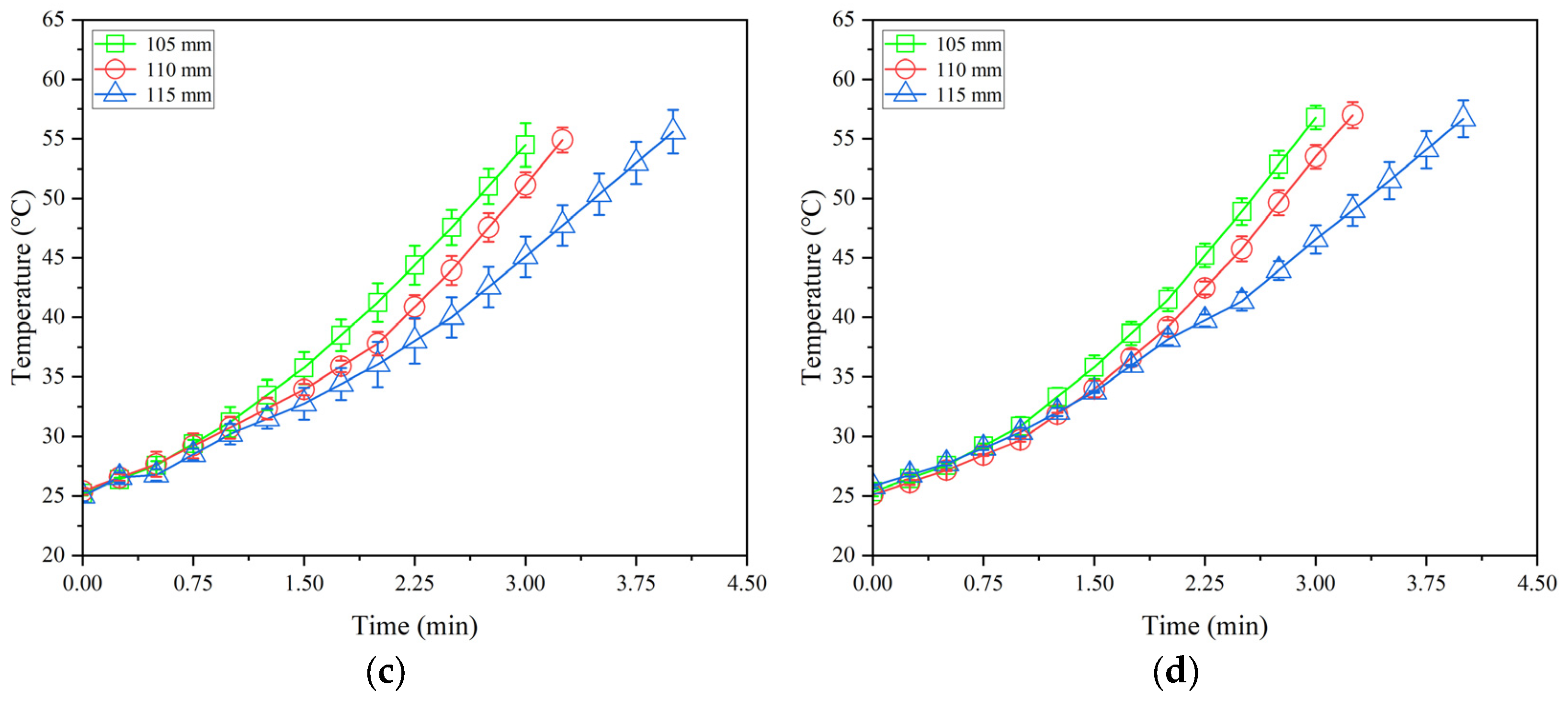

3.3. Temperature Distributions and Heating Uniformity Index of Tobacco Leaves Under Different Hot Air Temperatures

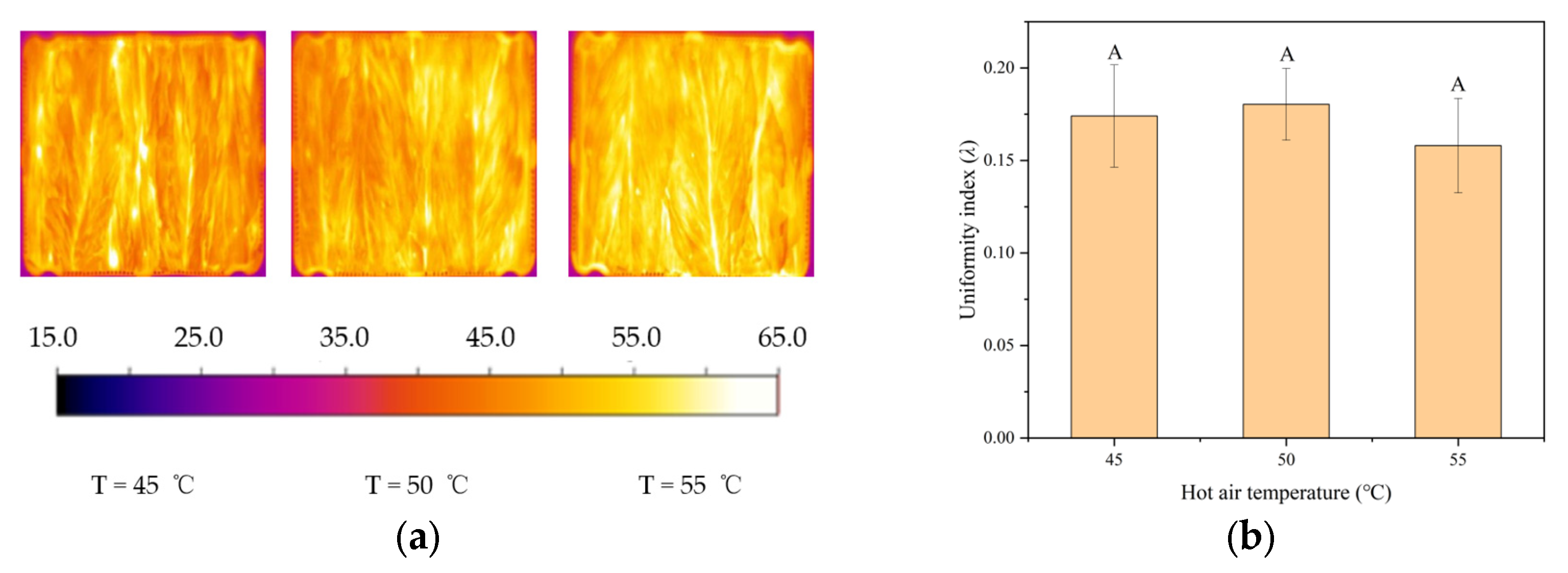

3.4. Effect of Different RF Treatment Methods on Uniformity

3.5. Evaluation of Thermal Efficiency of RF Heating System

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, C.; Li, Z.; Cao, Y.; Zhou, B.; Zheng, X. Partial characterization of stress-induced carboxylesterase from adults of Stegobium paniceum and Lasioderma serricorne (Coleoptera: Anobiidae) subjected to CO2-enriched atmosphere. J. Pest Sci. 2009, 82, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tang, J. Radio frequency heating: A new potential means of post-harvest pest control in nuts and dry products. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. 2004, 5, 1169–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baliota, G.V.; Lampiri, E.; Batzogianni, E.N.; Athanassiou, C.G. Insecticidal effect of four insecticides for the control of different populations of three stored-product beetle species. Insects 2022, 13, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, L.; Hou, J.; Li, Z.; Johnson, J.A.; Wang, S. Validation of radio frequency treatments as alternative non-chemical methods for disinfesting chestnuts. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2015, 63, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Ling, B.; Wang, S. Development of thermal treatment protocol for disinfesting chestnuts using radio frequency energy. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2014, 98, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, B.; Baik, O.D. Radio frequency selective heating of stored-grain insects at 27.12 MHz: A feasibility study. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 114, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbajal-Padilla, D.; Cerón-García, A.; Gómez-Salazar, J.A.; Rojas-Laguna, R.; Sosa-Morales, M.E. Postharvest treatments with radio frequency for 10 and 20 kg batches of black beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 3244–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Johnson, J.A.; Tang, J.; Wang, S. Industrial-scale radio frequency treatments for insect control in lentils. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2012, 48, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indumathi, C.; Manoj, D.; Loganathan, M.; Shanmugasundaram, S. Radio frequency disinfestation of Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) in semolina: An emerging thermal technique. J. Food Process Eng. 2023, 46, e14443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Liu, J.; Li, R.; Ramaswamy, H.S.; Wang, S. Effects of conveyor movement, layer rearrangement and sample mixing on pest mortality in milled rice subjected to radio frequency. J. ASABE 2024, 67, 823–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, S. Industrial-scale radio frequency treatments to control Sitophilus oryzae in rough, brown, and milled rice. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2016, 68, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Tang, J.; Wang, Y.; Powers, J.; Wang, S. Almond quality as influenced by radio frequency heat treatments for disinfestation. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2010, 58, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tang, J.; Sun, T.; Mitcham, E.J.; Koral, T.; Birla, S.L. Considerations in design of commercial radio frequency treatments for postharvest pest control in in-shell walnuts. J. Food Eng. 2006, 77, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Jing, P.; Jiao, S. Application of radio frequency energy in processing of fruit and vegetable products. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosi, M.C.; Pegna, F.G.; Nencioni, A.; Guidi, R.; Bicego, M.; Belcari, A.; Sacchetti, P. Emigration effects induced by radio frequency treatment to dates infested by Carpophilus hemipterus. Insects 2019, 10, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Monzon, M.; Johnson, J.A.; Mitcham, E.J.; Tang, J. Industrial-scale radio frequency treatments for insect control in walnuts II: Insect mortality and product quality. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 45, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Monzon, A.; Johnson, J.A.; Mitcham, E.J.; Tang, J. Industrial-scale radio frequency treatments for insect control in walnuts I: Heating uniformity and energy efficiency. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2007, 45, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiou, C.G.; Rumbos, C.I.; Stephou, V.K.; Sakka, M.; Schaffert, S.; Sterz, T.; Bozoglou, C.; Klitsinaris, P.; Austin, J.W. Field evaluation of Carifend® net for the protection of stored tobacco from storage insect pests. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2019, 81, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wang, S. Developing a screw conveyor in radio frequency systems to improve heating uniformity in granular products. Int. J. Agric. Biol. Eng. 2019, 12, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Shi, H.; Tang, J.; Li, F.; Wang, S. Improvement of radio frequency (RF) heating uniformity on low moisture foods with polyetherimide (PEI) blocks. Food Res. Int. 2015, 74, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zhu, H.; Yan, R.; Wang, S. Simulation and prediction of radio frequency heating in dry soybeans. Biosyst. Eng. 2015, 129, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, G.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; Birla, S.L. Computer simulation model development and validation for radio frequency (RF) heating of dry food materials. J. Food Eng. 2011, 105, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Zhu, H.; Wang, S. Experimental evaluations of radio frequency heating in low-moisture agricultural products. Emir. J. Food Agric. 2015, 27, 662–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyar, R.; Erdogdu, F.; Marra, F. Effect of load volume on power absorption and temperature evolution during radio-frequency heating of meat cubes: A computational study. Food Bioprod. Process. 2014, 92, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, H.; Yue, J.; Miao, Y.; Jiao, S. Investigation of radio frequency heating as a dry-blanching method for carrot cubes. J. Food Eng. 2019, 245, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, S.; Zhu, D.; Deng, Y.; Zhao, Y. Effects of hot air-assisted radio frequency heating on quality and shelf-life of roasted peanuts. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2016, 9, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, H.; Ramaswamy, H.; Wang, S. Developing effective treatment protocols to control bark beetle (Scolytidae: Dendroctonus armandi) in wood using radio frequency heating and forced hot air. Trans. ASABE 2018, 61, 1979–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Ling, B. Performance evaluation of the double screw conveyor in radio frequency systems: Heating uniformity and quality of granular foods. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 77, 102990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazoglu, T.K.; Miran, W. Experimental investigation of the effect of conveyor movement and sample’s vertical position on radio frequency tempering of frozen beef. J. Food Eng. 2018, 219, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Mao, Y.; Hou, L.; Wang, S. Developing a rotation device in radio frequency systems for improving the heating uniformity in granular foods. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2021, 72, 102751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birla, S.L.; Wang, S.; Tang, J.; Hallman, G. Improving heating uniformity of fresh fruit in radio frequency treatments for pest control. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2004, 33, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Zheng, J.; Li, M.; Tian, Y.; Wang, X.; Li, R.; Wang, S. Effect of BaTiO3 as a filling material with adjustable dielectric properties on improving the radio frequency heating uniformity in red jujubes. J. Food Eng. 2024, 375, 112059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Ling, B.; Zheng, A.; Zhang, B.; Wang, S. Developing radio frequency technology for postharvest insect control in milled rice. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2015, 62, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yue, J.; Tang, J.; Chen, B. Mathematical modelling of heating uniformity for in-shell walnuts subjected to radio frequency treatments with intermittent stirrings. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2005, 35, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ye, X.; Mo, Z.; Wang, H.; Gu, X.; Xi, J.; Li, R.; Wang, S. Thermal death kinetics of pests in tobacco leaves as influenced by heating rates and life stages. J. Stored Prod. Res. 2025, 111, 102591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyel, J.F.; Gruchow, H.M.; Tödter, N.; Wehner, M. Determination of the thermal properties of leaves by non-invasive contact-free laser probing. J. Biotechnol. 2016, 217, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozisik, M.N. Heat Transfer: A Basic Approach; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, P.; Wang, S. Effects of various directional movements of milled rice on radio frequency heating uniformity. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 152, 112316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Zhou, B.; Wang, S.; Hou, L. Heating uniformity in radio frequency treated walnut kernels with different size and density. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 75, 102899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, S.; Kong, F.; Singh, R.K.; Kuzy, J.D.; Li, C. Radio frequency heating of corn flour: Heating rate and uniformity. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 44, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, N.; Liu, Y.; Munir, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Niazi, B.M.K. Effects of hot air assisted radio frequency drying on heating uniformity, drying characteristics and quality of paddy. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 158, 113131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dag, D.; Farmanfarmaee, A.; Kong, F.; Jung, J.; McGorrin, R.J.; Zhao, Y. Feasibility of simultaneous drying and blanching Inshell hazelnuts (Corylus avellana L.) using hot air-assisted radio frequency (HARF) heating. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2023, 16, 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Huang, Z.; Wang, K.; Li, W.; Wang, S. Simulation and validation of radio frequency heating with conveyor movement. J. Electromagn. Waves Appl. 2016, 30, 473–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tiwari, G.; Jiao, S.; Johnson, J.A.; Tang, J. Developing postharvest disinfestation treatments for legumes using radio frequency energy. Biosyst. Eng. 2010, 105, 341–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Guan, X.; Li, R.; Ramaswamy, H.; Wang, S. Evaluating performances of a small-scale 50 O radio frequency heating system designed for home applications. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2023, 83, 103258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mesery, H.S.; Mwithiga, G. Performance of a convective, infrared and combined infrared- convective heated conveyor-belt dryer. J. Food Sci. Technol.-Mysore 2015, 52, 2721–2730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Gap (mm) | Thickness of Tobacco Leaves (mm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 60 | 80 | |

| 115 | 0.236 ± 0.015 Ba * | 0.251 ± 0.011 ABa | 0.274 ± 0.019 Aa |

| 110 | 0.239 ± 0.020 Aa | 0.253 ± 0.024 Aa | 0.302 ± 0.025 Aa |

| 105 | 0.243 ± 0.021 Ba | 0.256 ± 0.027 Ba | 0.364 ± 0.030 Ab |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Tian, Y.; Ye, X.; Mo, Z.; Li, R.; Wang, S. Effect of Processing Parameters on the Heating Uniformity of Postharvest Tobacco Leaves Subjected to Radio Frequency Disinfestations. Insects 2025, 16, 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16020228

Zhang J, Tian Y, Ye X, Mo Z, Li R, Wang S. Effect of Processing Parameters on the Heating Uniformity of Postharvest Tobacco Leaves Subjected to Radio Frequency Disinfestations. Insects. 2025; 16(2):228. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16020228

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jinsong, Yingqi Tian, Xin Ye, Zijun Mo, Rui Li, and Shaojin Wang. 2025. "Effect of Processing Parameters on the Heating Uniformity of Postharvest Tobacco Leaves Subjected to Radio Frequency Disinfestations" Insects 16, no. 2: 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16020228

APA StyleZhang, J., Tian, Y., Ye, X., Mo, Z., Li, R., & Wang, S. (2025). Effect of Processing Parameters on the Heating Uniformity of Postharvest Tobacco Leaves Subjected to Radio Frequency Disinfestations. Insects, 16(2), 228. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects16020228